Abstract

The South African polity, since democracy, has witnessed significant shifts in state policy calling for the increasing professionalisation of the civil service in general through the National Development Plan (NDP) and the National Professionalisation Framework (NPF) for the public service. The rationale behind these has been to build a capable and efficient state. This article presents a critical review of literature pertaining to professionalisation of the civil service as it relates to the human settlements sector in South Africa, with a particular focus on the major causes of inefficiencies in service delivery. The article argues that beyond the calls for overall professionalisation, the human settlements professional project has a more specific history which has been a systemic response to sector deficiencies and constraints. Therefore, this study will necessarily consider existing policy frameworks, as well as selected empirical evidence on the professionalisation of human settlements in South Africa. The article examines international trends and local directions in professionalisation, as well as considering key leverage points for the domestication of an implementation framework to guide professionalisation in the arena of human settlements for enhanced service delivery, improved quality of household life, and economic progress. The main findings emphasise strong alignment between sector deficiencies and professionalisation objectives. The article argues for a more rapid advancement of professionalisation processes to address the significant systemic weaknesses across the human settlements sector, and suggests that these have created systemic barriers to effective service delivery of human settlements. The study takes care not to advance professionalisation as a panacea and highlights potential negative impacts of professionalisation efforts. The study highlights significant developments at the policy, institutional, and interorganisational level to nurture progress towards sector professionalisation. New organisations operating in dynamic networks and partnerships are emerging to collaborate to support sector-wide professionalisation efforts.

1 Introduction

Sustainable community development is predicated on the notion that effective human settlements play a fundamental role in promoting social cohesion, economic inclusion, and environmental sustainability (Winston, 2022). In South Africa, efficient housing delivery remains a persistent challenge (Mhlongo et al., 2022), despite numerous policies and government interventions (Ramovha, 2017). The South African state in the first two decades of democracy (1994-2014), has received international recognition from UN-Habitat (the UN Human Settlements Programme), for its track record in significantly addressing housing backlogs (Huchzermeyer and Karam, 2016). In addition, this period was marked by significant revisions to the housing subsidy system as well as the institutional frameworks for housing delivery. In 2004, SA’s adoption of the Breaking New Ground (BNG) policy boldly pivoted from a progressive housing programme to a more holistic and multi-layered human settlements policy approach via its Department of Human Settlements (DHS) (Ramovha, 2022). Thus far, commentators such as Bradlow et al. (2011) have been highly critical of the dominant implementation modalities where contractor-driven implementation has been associated with problems of shoddy workmanship. The DHS itself has highlighted the challenges of corruption, and patronage instead pro-offering the value of more people centre models such as the peoples housing process (DHS, 2019).

In the context of SA’s nascent democracy, professionalisation of the housing and human settlements development has been gathering momentum since the early 1990s (Kwakweni et al., 2012). A systemic analysis of the first three decades of housing and human settlements has highlighted a range of critical aspects affecting the efficiency of human settlements delivery in South Africa (Mhlongo et al., 2022; Ramovha, 2017; Guma, 2018). The South African human settlements sector relies on 12 allied professions across a range of specialisations; however, none fulfil the role of housing and human settlements professional. This leaves an estimated 2,000-plus officials operating in the human settlements value chain who are unaffiliated with any existing professional body and consequently unregulated.

Unlike other sectors such as health, law, and accounting, the human settlements development management profession continues to lack a well-structured professional framework, leading to inconsistent service delivery and mismanagement (Adeniran et al., 2021). Significantly, the national government, through the recently published White Paper on Human Settlements, has acknowledged that sector professionalisation is a priority (DHS, 2025; Figure 1).

Figure 1

Ecosystem of professions in South Africa’s human settlements sector. Source: Authors’ conception.

In this context, professionalisation involves the establishment of formal educational pathways, regulatory bodies, and ethical guidelines to standardise skills (Hart and De Beer, 2022), improve accountability, and enhance service delivery (Noordegraaf, 2016).

Professionalisation is the action or process by which an occupation, activity, or group of professionals gains specific knowledge, qualities, and attributes and becomes worthy of public trust, typically by increasing training or acquisition of unique qualifications, as well as faithful adherence to strict value systems typically formulated as codes of conduct (Evetts, 2014). Freidson (1988, 1999) argues that professionalisation is thus viewed as a universal process which expresses the manner in which an occupation gains the status of a profession.

Professionalisation involves a series of actions and requires a suite of mechanisms that must be put in place. This, however, does not negate the significance of a distinctive and specialised knowledge acquired in an extended period of preparation. Shulman (2005) asserts that professional education is a synthesis of three apprenticeships:

Firstly, a cognitive apprenticeship where one learns to think like a professional. Secondly, a practical apprenticeship where one performs like a professional. Finally, a moral apprenticeship where one learns to think and act in a responsible and ethical manner.

Shulman (2005) further argues that a professional is not someone for whom understanding is sufficient. Professionals not only have to understand and perform, but they also have to assume ethical traits that require them to undergo a certain kind of formation of character and values so that they become a kind of person to whom society can entrust a variety of services of public interest, such as education, health, justice, and others.

This article argues that, contextualised in the South African post democratic situation, professionalisation of the human settlements sector must respond to the White Paper on Human Settlements policy statement on sector capability, namely:

“The human settlements sector is faced with various challenges, including the lack of a capable and ethical workforce across the three spheres of government, which is integral to the delivery of sustainable human settlements. In addition, the absence of a dedicated professional body to hold the personnel in the human settlements sector accountable for their poor and inefficient decisions, has impacted negatively on the outcomes of the housing delivery value chain (DHS, 2025, 76).”

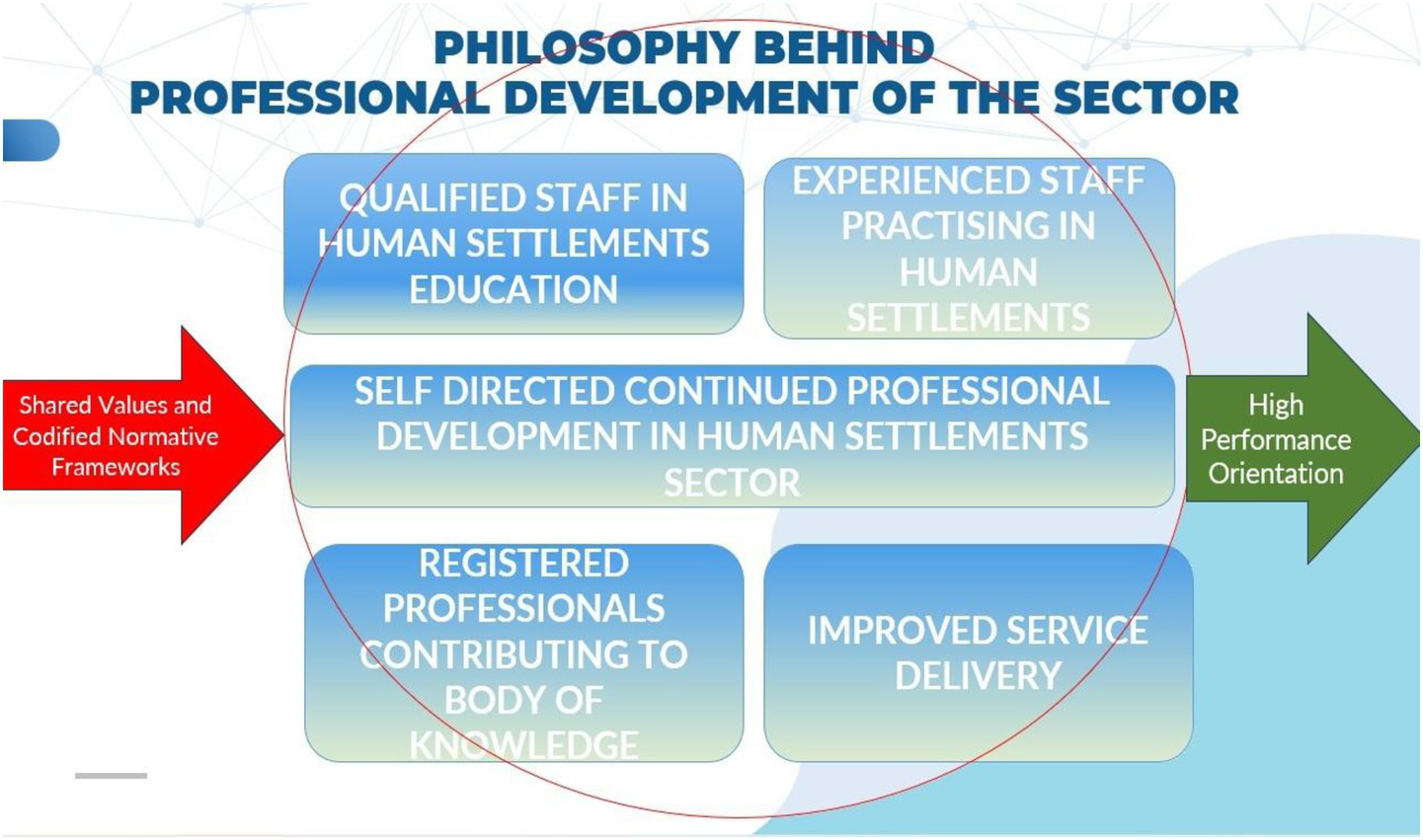

It follows then that professionalisation of human settlements refers to the four pronged process by which human settlements development and management is co-created by practitioners, state actors and others into a fully recognised profession, with (1) tailored qualifications aligned to a human settlements specific body of knowledge, also known as human settlements body of knowledge (HSBok), (2) compulsory professional standards and ethical codes enforced by way of (3) an representative professional council whose ultimate goal is (4) service excellence in regards to the constitutional commitment to the delivery of sustainable housing and urban development across all mandated departments and agencies (Boyce, 2024; Figure 2).

Figure 2

Depiction of pillars of human settlements professionalisation and intended outcomes. Source: Boyce (2024).

Given South Africa’s rapidly growing urban population and the increasing demand for sustainable and affordable housing, addressing the barriers to professionalisation is crucial.

Since the transition away from a housing-oriented discourse of the early 1990s to sustainable human settlements embraced since 2005, there is a wider recognition that current implementation modalities are in adequate (Schoeman and Chakwizira, 2023), and that the acknowledgement of a science of human settlements also known as Ekistics is crucial (Gürel, 1995; Liu et al., 2023) to augment the evolution of allied disciplines such as traditional planning. Using these lenses, this article explores the prospects, constraints, and barriers to efficient human settlement delivery in South Africa, with a focus on how professionalisation can improve sector performance for enhanced development outcomes.

2 Problem statement

Despite government efforts and significant financial investment, South Africa continues to face inefficiencies in the delivery of human settlements. Housing backlogs, informal settlements, and inadequate infrastructure remain widespread. The absence of a structured professionalisation framework within the housing sector exacerbates these challenges, leading to poor planning, weak anti-corruption measures, and inefficient service delivery.

Several questions arise:

To what extent does professionalisation contribute to the improvement of human settlements delivery?

What are the key constraints affecting the professionalisation of the sector?

How can policy reforms enhance the role of skilled professionals in implementation and governance of human settlements programmes?

This study aims to address these questions by evaluating the prospects of professionalisation as a solution to inefficiencies in the housing sector, identifying existing barriers, and proposing reform strategies. This study is significant for several reasons, including

Policy Implications: The findings will provide insights for policymakers on how to structure the human settlements sector for better service delivery.

Academic Contribution: It will contribute to the literature on human settlements development and management, professionalisation, and urban governance in South Africa.

Practical Solutions: The study will offer recommendations to improve the skills base, accountability, and efficiency of professionals in the human settlements sector.

Sustainable Development: Addressing inefficiencies in human settlements will contribute to the achievement of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities and SDG 8: promote sustained, inclusive, and sustainable economic growth.

By examining the role of professionalisation in improving human settlements delivery, this study aims to provide a framework that enhances efficiency, reduces corruption, and ensures sustainable housing development in South Africa. In contrast, housing and human settlements is a matter that affects the context beyond South Africa. It is hoped that other comparable countries and nations will draw inspiration from the results of this study, to consider it in their pursuit of sustainable development goals and beyond.

3 Methodology

This study was framed within the pragmatic paradigm, adopting an iterative research design that leaned on the qualitative research approach. The study follows a literature review approach and therefore relies extensively on secondary data to collect relevant information (Jesson, 2011).

3.1 Data sources

In this instance, the review of secondary sources provides an in-depth understanding of human settlements delivery and professionalisation.

This method facilitates a critical evaluation of existing policies, frameworks, and case studies. This study employs strict textual analysis of the available literature relating to challenges, constraints, and barriers to the efficient delivery of human settlements in South Africa, while drawing on international scholarship in this regard. The purpose of this approach was to put the study question into a historical context to provide a sound understanding of the underlying trends, patterns, concepts, and assumptions behind weakness in service delivery in the human settlements space in South Africa.

This study thus relies on a wide range of secondary data sources Sileyew (2019), including in Table 1.

Table 1

| Secondary sources | |

|---|---|

| Policy and government reports | National Development Plan (NDP), Human Settlements White Papers and policy documents, Department of Human Settlements annual reports. |

| Evaluation and monitoring reports | Department of Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation (DPME, 2020–2021) assessment of the Human Settlements Programme. |

| Academic and scholarly literature | Peer-reviewed journal articles on urban planning and management, housing policy, and professionalisation. Books on urbanism, planning, housing, and human settlements. |

| Comparative literature | Regional and Multilateral institutions and agencies. This includes reports from other countries. |

| Grey literature and reports from professional bodies | Sector reports addressing comparative studies on professionalisation relevant to human settlements, such as the planning profession, South African Council for Planners (SACPLAN). Reports from the national media and chapter nine institutions that have produced investigative reports on inefficiencies in housing delivery. |

List of secondary sources.

3.2 Selection criteria

In addition, the study was guided by a defined selection criteria in screening literature for inclusion. The study applied a three-pronged criterion, including considering the following:

First, the literature screening process was guided by the criterion of relevance. Here are sources needed to address the following topics relating to ‘housing delivery’, ‘professionalisation’, ‘governance’, or ‘public sector reform’.

The second criterion was related to the appropriateness of the geographic fit and the study timeframe. In this case, documents addressing South African studies within the time period from ‘1994 to 2025’ were selected for inclusion.

The third and final inclusion criterion was related to credibility. While preference was given to peer-reviewed and official reports, these were triangulated with media and grey sources to capture practice-based insights.

Given the dearth of literature on this topic, the study scanned appropriate reports and academic articles from allied disciplines, such as planning and culturally relevant locales, like the UK and the USA, to gain insights applicable to South Africa.

3.3 Analytical approach

The study employed a thematic analysis to code the data. The notion of saturation, as used in qualitative research, is of relevance here. When thematic analysis was applied to the data set, the following recurring themes were yielded:

Efficiency of housing delivery,

Governance and corruption,

Professionalisation frameworks,

Institutional and capacity constraints and,

Comparative international models.

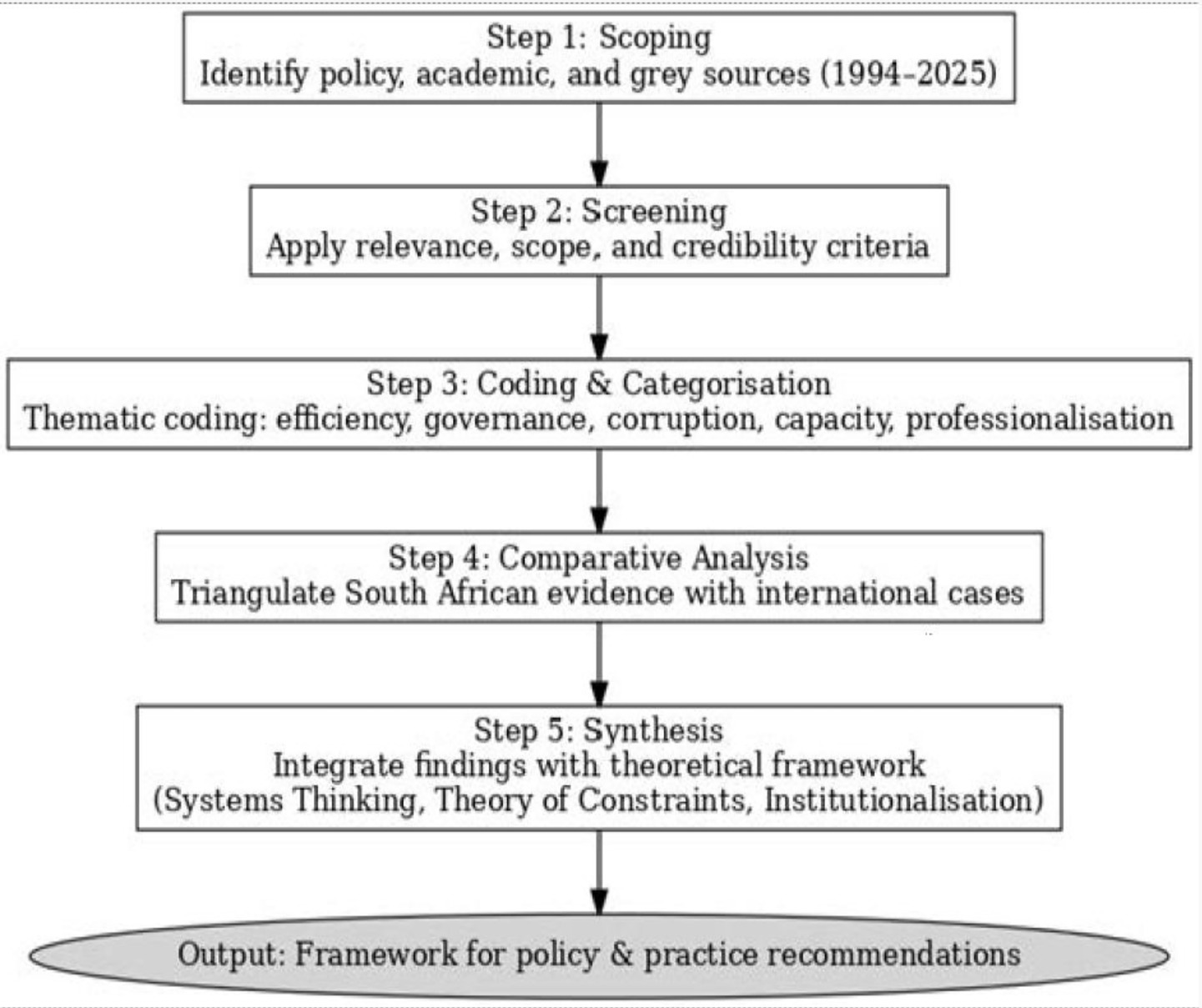

Following thematic analysis, the above-listed themes were mapped against the article’s blended theoretical framework, namely, systems thinking, theory of constraints, and the institutionalisation of professions. In this way, the study was able to identify interconnections across policy, institutional, and delivery subsystems. The study sought to pinpoint critical bottlenecks undermining efficiency whilst exploring pathways for embedding professional norms and standards systemically (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Flow of research process guiding the study. Source: Authors’ conception.

This section outlines the selected research methodology, which is a traditional literature review and details the data sources used. The selection criterion applied has been clarified, and the analytical approach used has been detailed. Finally, the section shows how the research methods and analytical approach complement the blended theoretical framework of the study.

4 Unpacking key challenges impacting human settlements sector performance in South Africa

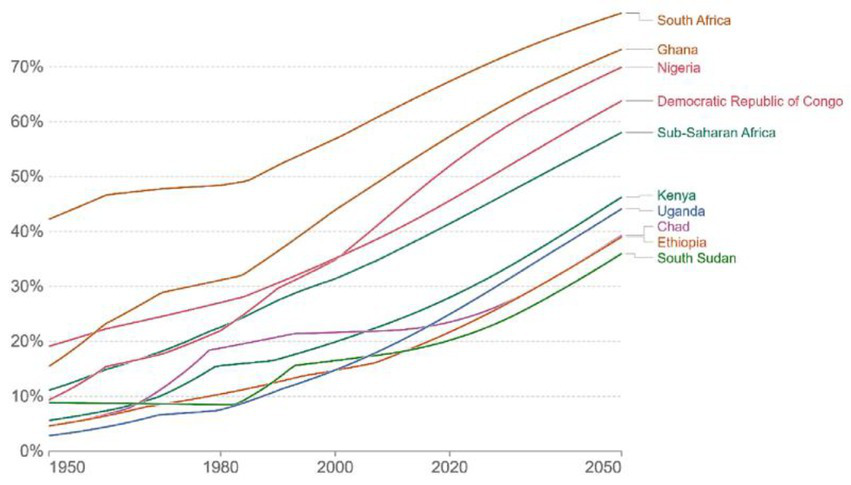

Consistent with global megatrends (Artuso and Guijt, 2020), urbanisation in South Africa has been accelerating rapidly, with the urban population growing from 52% in 1990 to over 68% in 2023 [United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA), 2023]. Figure 4, as depicted in the study by Sakketa (2023), illustrates this trend.

Figure 4

Accelerating rate of urbanisation in South Africa. Source: Sakketa (2023).

The primary driver of this trend has been rural-to-urban migration, economic opportunities in metropolitan areas, and demographic growth (Arndt et al., 2018). Authors like Mlambo (2018) report that South Africa’s urbanisation is predicted to reach a staggering 80% by 2050. While ordinarily urbanisation usually presents opportunities for economic development, in the case of South Africa (SA), the country enjoyed only modest economic growth, negative structural change, and inadequate job creation and poverty reduction (Arndt et al., 2018). In SA’s case, it has also exacerbated challenges such as housing shortages, inadequate infrastructure, strained public services, and the growth of informal settlements (South African Cities Network, 2014).

One of the critical and seemingly intractable issues facing South African cities is the persistence of spatial inequality, a legacy of apartheid-era policies that created segregated urban layouts with unequal access to services and economic opportunities (Maharaj, 2020). Many low-income communities still lack adequate housing, reliable water and electricity supply, efficient waste management, and accessible transportation networks. Additionally, rapid urban growth has placed immense pressure on municipalities, resulting in poor service delivery, inefficient infrastructure planning, and environmental degradation (Mahendra and Seto, 2019). Numerous commentators (Bradlow et al., 2011; Ramovha, 2017; Ackerman, 2016) have emphasised a growing body of knowledge concerning the lack of efficiency of human settlements delivery in South Africa.

According to Stats SA (2023), South Africa’s housing backlog exceeds 2.6 million units, with over 13% of urban dwellers living in informal settlements. Service delivery protests have also become more frequent, indicating rising public dissatisfaction with urban governance. In this context, innovative solutions are needed to improve urban planning and ensure sustainable and inclusive human settlements development.

Given South Africa’s ever increasing housing shortage (Ramovha, 2022; Bradlow et al., 2011), it has been argued that the country requires vast numbers of suitably qualified human settlements management professionals (HSMP’s) beyond the existing built environment professionals, (Van Wyk, 2016, p. 8) to address the urgent and enormous need of access to shelter (DHS, 2013).

The challenges posed by the pace of housing delivery are compounded by serious quality issues with the housing being delivered (Bradlow et al., 2011). The delivery of incomplete and defective units by unscrupulous contractors has emerged as a serious threat which undermines the delivery numbers of the Housing and Human Settlements Programme. The extent of this challenge is colossal, to the point that by 2011 it was estimated that it would cost approximately 58 billion rands to “rectify” defective units (News24, 2011; NHBRC, 2011). This weakness in the human settlements policy implementation relates directly to the National Department of Human Settlements’ inability to apply normal contract management procedures as well as prescribe policies for the exclusion of such contractors from doing business with government (IOL, 2025; Guma, 2018).

In addition, a major issue bedevilling the provision of adequate housing by the state is the increase in the number of blocked or incomplete projects (Thorne, 2024). By 2021, the DHS responded to this challenge by introducing a “national unblocking programme” with the aim of bringing stalled projects back to implementation and completion (DHS, 2014; DHS, 2024). As of the beginning of 2024, the total number of blocked and incomplete projects stood at 3,445 and outnumbered the number of informal settlements nationally. One of the provinces most severely impacted by blocked and incomplete projects is the centrally located Free State province, with 770 (Thorne, 2024).

The North West province is another of those impacted by incomplete RDP housing projects with the South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC) reported that 17 projects were incomplete whilst 773 housing units remained unfinished. The SAHRC concluded that the province, “failed to fulfil its mandate within reasonable timeframes and prescribed quality standards, thereby infringing on beneficiaries’ constitutional rights and dignity as per Section 26(1) and 10 of the Constitution [SAHRC (South African Human Rights Commission), 2024, p. 8].”

The severity of this challenge has resulted in the unblocking of projects being earmarked as a ministerial priority for the three-year period from the 2022/2023 financial year (DHS, 2024). The underlying reasons for unblocked projects are varied and can be placed under four broader categories. First, poor management of technical considerations; second, poor contract management; third, social disruption; and finally, criminality. These specific issues include a lack of bulk infrastructure, geotechnical issues, outstanding township establishment, the construction mafia, illegal occupations, community unrest, and poor contractor performance (DHS, 2024). Progress in this matter has been painfully slow, so that by the beginning of 2024, the department reported that a mere 320 projects representing less than 10% of unblocked projects had been resolved (Thorne, 2024).

Graham et al. (2014) maintain their view that the national housing programme, as implemented in South African cities, has been rigid, relatively linear, and silo-based, and that municipal planning frameworks have developed into a complex rubric of plans covering different sectors and timescales. The SAHRC, in its investigation into delivery weaknesses in the North West provinces, noted that these challenges are widespread and systemic, impacting all municipalities in the province. Further, the SAHRC ascribed the weaknesses to mismanagement, inadequate planning, contractual disputes, and insufficient oversight by the Provincial Treasury and the Premiers’ Office [SAHRC (South African Human Rights Commission), 2024]. While Mamokhere (2022) has correctly argued that there is a complex interplay of systemic and structural factors that impact service delivery at the local government level. At a city planning level, most plans relate in some way to human settlements (Graham et al., 2014; SALGA, 2012). Increasingly, professionalisation processes have been seen as a silver bullet to addressing these concerns in an institutionalised manner [LGSETA (Local Government Sector Education and Training Authority), 2019].

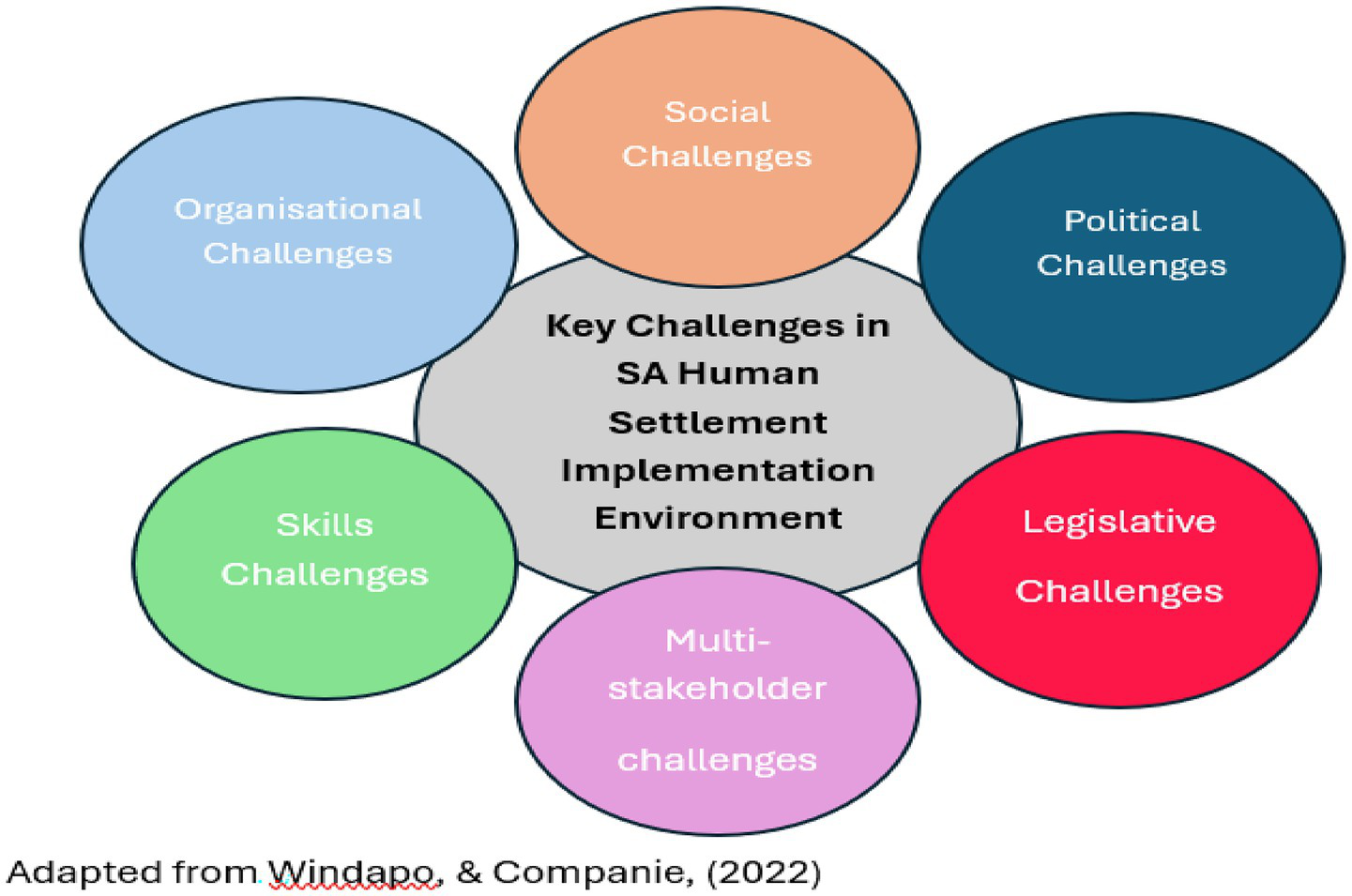

There should be caution not to overstate the case for the effectiveness of professionalisation processes to address the efficiency and quality of service delivery, as this is due to the acknowledged complexity of measuring such capacity development initiatives at a system-wide level (Ramovha, 2022). Companie (2020) argues that the dynamism of the human settlements implementation environment in South Africa creates complexity that poses numerous challenges, hindering the efficient delivery, management, and maintenance of housing projects. Moreover, Windapo and Companie (2022) report six themes emerging from the challenges facing the implementation of human settlements projects in the SA context, namely, (1) social challenges; (2) political challenges; (3) organisational challenges; (4) legislative challenges; (5) multi-stakeholder challenges; and (6) skills challenges. See Figure 5.

Figure 5

Key challenges facing the human settlements implementation environment. Source: Windapo and Companie (2022).

5 Selected implementation typologies proposed to guide human settlements delivery in South Africa

This section engages with recently proposed implementation models emanating from empirical studies, comprehensive reviews, or peer-reviewed academic studies. Four recent studies have offered significant insights into the key challenges and constraints to professionalisation issues in human settlements in the SA context.

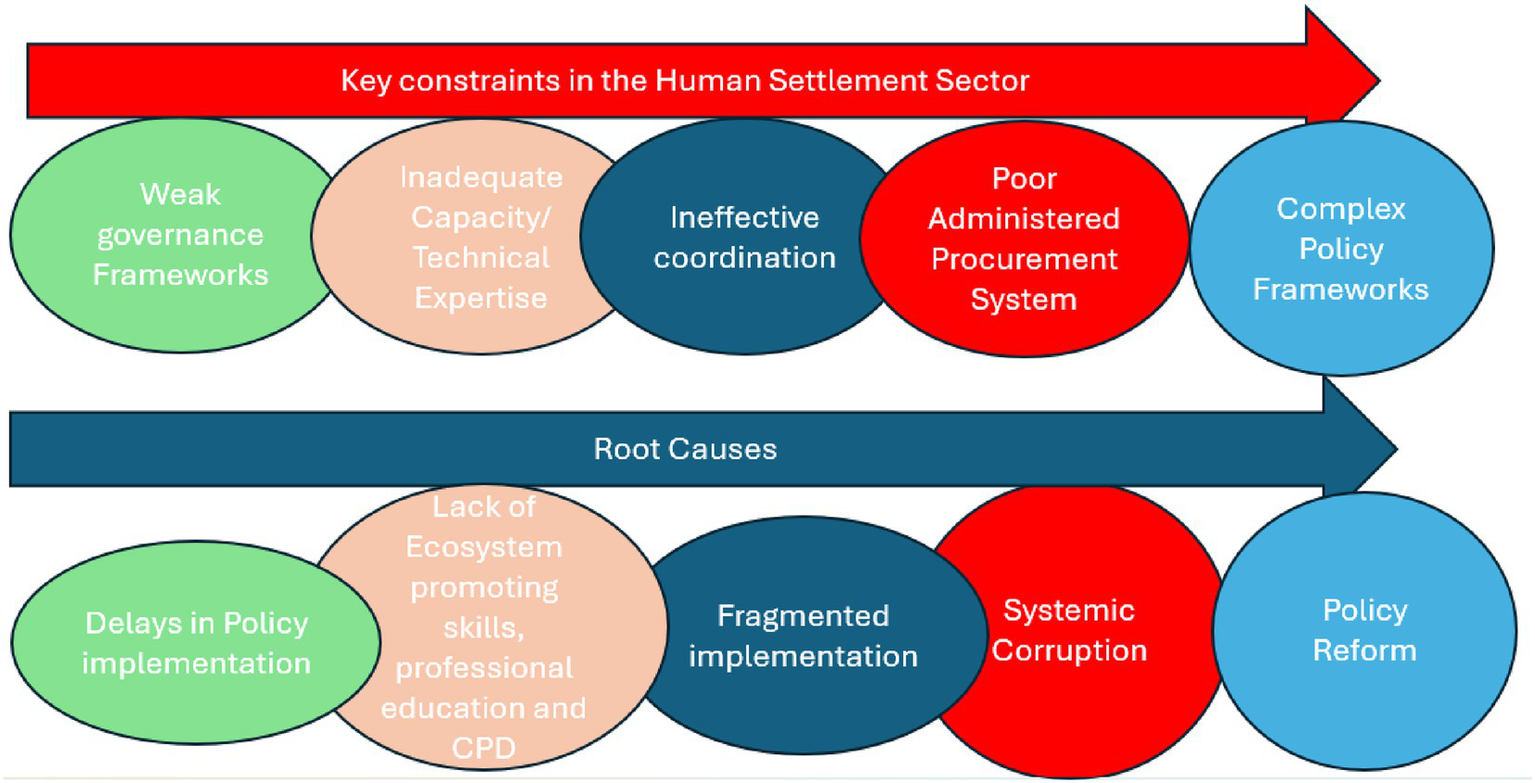

Companie (2020) offers the recommendation that highlights professionalisation of the sector as a key impediment to service delivery efficiency. By pinpointing a lack of skilled personnel, inadequate capacity, and ineffective coordination between public and private sector players, Companie (2020) perceptively isolates critical constraints in the human settlements implementation value chain.

Ramovha (2017, 2022), building on these insights, highlights the systemic barriers in human settlements, noting issues such as a lack of technical expertise, delays in policy implementation, and the fragmented approach to urban planning and development. These constraints significantly affect the efficiency and sustainability of human settlements project implementation, particularly in regions with pressing needs, such as the Eastern Cape of South Africa.

The work of Adeniran et al. (2021) and Guma (2018) highlights the lack of controls and persistent challenges around the procurement/supply chain processes, which are central to successful human settlements delivery, given the contactor-centric modality of delivery. Adeniran et al. (2021) make a strong case that the capacity to manage large-scale infrastructure projects is limited by poor governance, lack of transparency, and inadequate project management skills.

Guma (2018) focuses specifically on the Eastern Cape and provides a detailed analysis of how procurement-related issues hamper service delivery. Guma (2018), by isolating systemic bureaucratic inefficiencies, regulatory issues, including large-scale corruption, underline the weaknesses that hamper timeous and cost-effective human settlements delivery.

Taken together, these issues point to the urgent need for policy reforms that prioritise professionalisation (with its systemic approach to skills, capacity, and institutional development), enhanced governance frameworks, and streamlined procurement processes to address the identified barriers and secure a more efficient delivery of human settlements in South Africa (Figure 6).

Figure 6

Key constraints impacting efficiency within the human settlements value chain. Source: Authors’ conception.

In addition, the insights presented above and synthesised in the Figure 7 align with a host of monitoring reports from the Department of Monitoring and Evaluation (DPME) as well as the DHS itself. The most recent reports have called for enhanced capacity (both increased numbers and skills of implementers), the need to address institutional gaps, clarification of implementation standards, governance reforms, and enhanced frameworks for multisectoral collaboration. Critically, a hard-hitting report by DPME states that “these issues have resulted in delays, inadequate service delivery, and missed opportunities for integration (DPME, 2024, p. 91).”

Figure 7

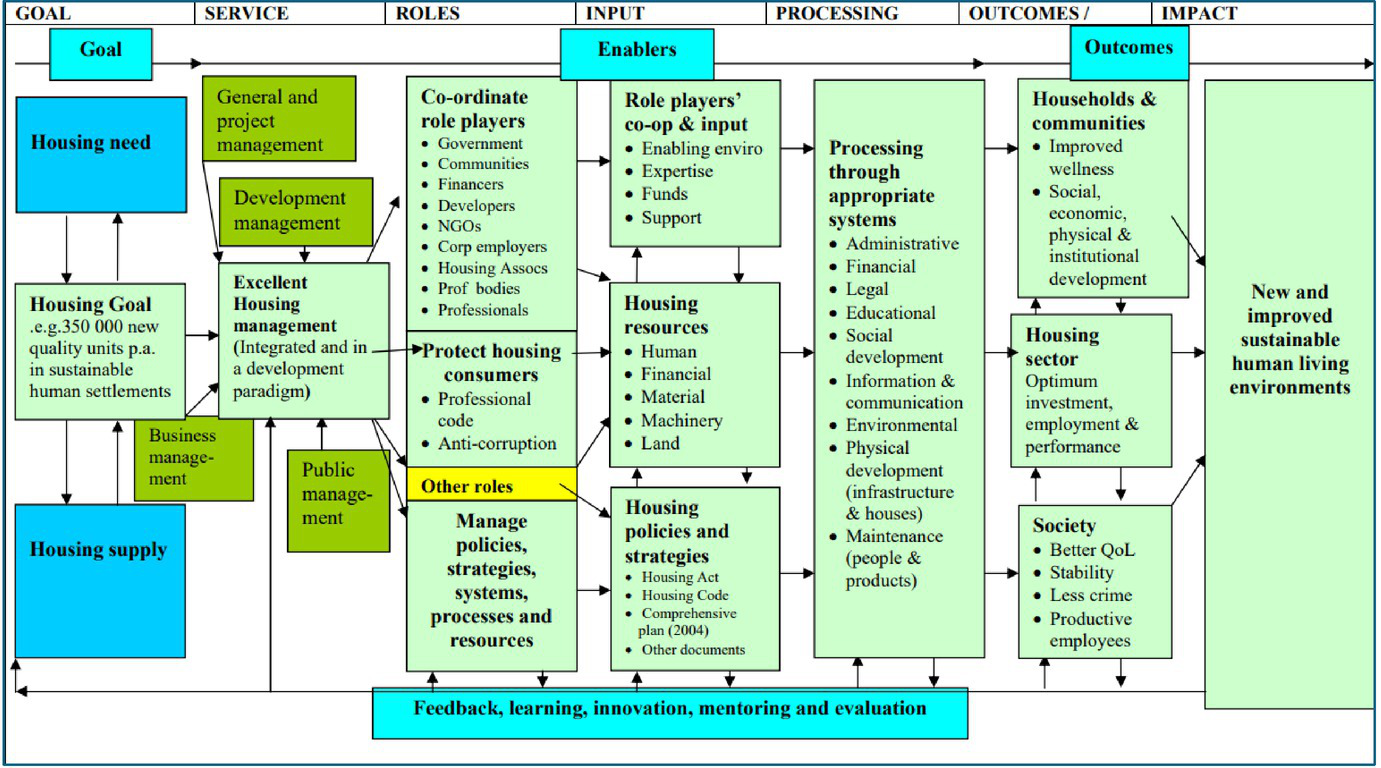

Housing competencies. Source: Van Wyk and Crofton (2005).

This section illustrates a strong resonance between the academic literature and recent high-level sector reports on core challenges to be addressed to enhance service delivery.

6 The drivers of professionalisation in public service delivery and human settlements

6.1 Public sector reforms to ensure efficiencies in state capacity and to monitor and evaluate outcomes

The National School of Government and the Department of Public Service and Administration have argued for the implementation of the National Professionalisation Framework. The professionalisation framework takes a public sector wide approach seeking a unified public administration that applies to the national, provincial and local government, as well as State-Owned Entities (SOEs) and seeks to ensure that only qualified and competent individuals are appointed into positions of authority in pursuit of a transformed, professional, ethical, capable and developmental public administration (NSG, 2022).

6.2 The sector project to professionalise human settlements: three decades in the making

The project to professionalise human settlements in South Africa spans more than three decades, where forerunners of the Institute of Human Settlements Practitioners South Africa (IHSP-SA), such as the Institute for Housing South Africa (IHSA) and SA Housing Foundation, pioneered bottom–up professionalisation initiatives. This unique struggle for full professional recognition received significant support from the then Department of Housing, led by the second Minister Sankie Mthembi-Mahanyele, together with the UK-based Chartered Institute for Housing (CIH-UK, 1997). Unlike planning, real estate marketing, education, or law, which have received significant state attention, human settlements professionalisation processes have not received investment, policy, and legal reform to reach maturity (DoH, 1994).

In these professions the intersecting goals of intense public interest, transformation goals, powerful elites, and effective historic structures have allowed for the emergence of professional frameworks and reformed statutory councils [such as South African Council for Planners (SACPLAN), Property Practitioners Regulatory Authority (PPRA), Legal Practice Council (LPC), South African Council for Educators (SACE)] regulate practitioners conduct and to provide normative frameworks to guide service. Conversely, within the human settlements sector, human settlements development and management remain underregulated, fragmented, and lack a formalised profession despite a large body of unregulated practitioners estimated to exceed 2,000–3,000 professionals (DHS, 2016).

While allied built environment disciplines (planners, engineering, and architecture) are governed by statutory bodies such as the South African Council for Planners (SACPLAN) and the Engineering Council of South Africa (ECSA), no equivalent exists for human settlements management professionals. This institutional and practice gap contributes to inconsistent standards, uneven capacity across municipalities, and persistent inefficiencies in housing delivery (DPME, 2024; Adeniran et al., 2021; Van Wyk, 2016).

6.3 International trends and local perspectives for human settlements professionalisation

Professionalisation of human settlements refers to the deliberate creation of a recognised profession of human settlements practitioners, as exists internationally in the UK and the USA. In these contexts, human settlements professional practice is anchored in specialised educational pathways, a coherent competency framework, continuous professional development (CPD), and an enforceable code of ethics, designed to improve accountability, efficiency, and inclusivity in housing and settlements delivery. In the SA context, it implies moving towards a system in which trained professionals, guided by sector-specific standards, play a central role in planning, implementing, and monitoring housing interventions in conjunction with existing professions.

This conceptual framing positions professionalisation not simply as a generic public administration reform, but as a sector-specific institutional transformation aligned with international trends. This is essential for addressing South Africa’s housing backlog, systemic corruption, and spatial inequality. It also aligns with international trends, where professional bodies have played a critical role in strengthening governance and delivery in rapidly urbanising contexts.

Below is a more detailed comparison of mostly state-enabled institutional transformations that led to the implementation of enhanced professionalisation frameworks. Thereby enhancing public trust, accountability, standards, and service delivery norms.

This section presents a wide cross-section of professions that have undergone professional transformations which have significantly adapted their institutional structures, realigned competency standards, defined education requirements, strengthened integrity systems, and enhanced consistency of professional practice and service outcomes to clients. These lessons are appropriate and highly applicable to the human settlements professionalisation journey.

Table 2 presents a synthesis of international professional associations in human settlements that have followed a defined professionalisation pathway which has enhanced public trust, strengthened accountability, and defined educational and competency frameworks for entry to these professions. In addition, the evolution of various local professions is traced, outlining the pathways to professionalisation, institutionalisation, and outcomes for stakeholders.

Table 2

| Sector | Pathway to professionalisation | Institutional features | Outcomes/implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| International context housing and human settlements | Strong voluntary associations, licensing boards Non-statutory regulation (UK & USA) |

Standards of education Strict accreditation Ethical codes CPD requirements |

Public trust, improved quality of care, Professional accountability Functional housing market |

| Planning | Accredited planning degrees, statutory council (SACPLAN) | Competency standard & CPD Registration Ethical Codes |

Consistency in land use planning, alignment with developmental state imperatives |

| Law | Accredited law programs, bar exams, Professional Association evolved in the national statutory Council |

Standards of education Ethical codes Examination-based entry |

Legal consistency, protection of rights Professional autonomy, High professional standards |

| Real estate and property marketing | Estate Agents were governed by professional association which was transformed into a statutory regulatory authority | Standards of education Ethical codes Statutory regulator |

Consistency in property marketing & sales, Protection of rights of clients, High professional standards |

| Human settlements (current status in SA) | Fragmented delivery by approx. 2–3,000 practitioners who remain ineligible to join any of the 12 allied professions (engineers, planners, project managers), No statutory council |

Standards of Education Competency framework Voluntary Association |

Inconsistent housing delivery, Increasing housing backlog, weak accountability, over-reliance on contractors, skills gaps |

| Human settlements (proposed professionalisation) | Compulsory registration Statutory Council Formalised qualifications tied to competencies CPD required |

Mandatory ethical codes Accredited Qualifications Compulsory CPD Recognised career pathways |

Ethics frameworks enforced Skilled professionals Compulsory registration Service standards frameworks Improved efficiency, reduced corruption, client centred delivery, improved governance |

Comparative table: professionalisation across sectors.

In the context of SA, the delivery of human settlements is a complex enterprise, requiring a cross-functional professional operating within a multidisciplinary team who possesses knowledge and expertise across disciplines, including urban planning, infrastructure development, land use management, programme and project management, and policy implementation.

The role of professionalisation of the human settlements sector involves purposeful development of human settlements educational pathways by establishing and strengthening of a hierarchy of formal qualifications, sector-relevant competencies, and ethical standards which resonate with practitioners in the field. In addition, the central aims of a human sector-specific professional project must be to enhance client care through enhanced efficiency of processes and products, accountability, and longer-term sustainability via the application of innovative design and implementation modalities, emphasising inclusive approaches.

Three key drivers of professionalisation discourse in relation to HS in South Africa have been the concerns around (1) efficiency, (2) quality, and (3) client-centredness. Authors like Van Wyk (2016, p. 8) argue that “HS practitioners should be able to address the relevant issues satisfactorily and enhance the rate of delivery while maintaining an acceptable quality of standard” and that in addition “a new approach to HS management” which balances the need for performance-based managerial approach with a stronger focus on the client which is exemplified by the social welfare ethic (Van Wyk, 2016, p. 9).

More recently, the Institute of Human Settlements Practitioners-South Africa (IHP-SA), in conjunction with its partner universities, has developed a matrix of competencies to guide human settlements education and practitioners’ CPD programme in SA (IHSP-SA internal report). Table 3 is emerged from a national human settlements practitioner workshop hosted by the University of Free State in 2022.

Table 3

| Core competencies | |||

| Human settlements laws and policies | Finance and human settlements | Human settlement and housing theory | Project and programme management |

| Complimentary competencies | |||

| Sustainable Livelihoods/ LED/ Entrepreneurship | Community Participation/Facilitation/PHP | Environment and Human Settlements | Sustainability Science and Human Settlement |

| Supporting competencies | |||

| ABT, Innovative Design & Human Settlements | Governance Systems & Human Settlements | Property Marketing and Human Settlements | Property Development and Human Settlements |

Key competencies of human settlements professionals and students (Source: IHPSA, 2022).

International agencies such as UN-Habitat (2016) emphasise the premise that sustainable urban development requires a workforce with specialised knowledge in planning, engineering, environmental management, and community engagement. Deficiencies in professionalisation often result in delays, cost overruns, and poor-quality infrastructure. Authors like Napier (2013) argue that a shortage of trained professionals in urban management affects service delivery, particularly in developing country contexts.

6.4 The distinctive contribution of the human settlements profession to the human settlements value chain in South Africa

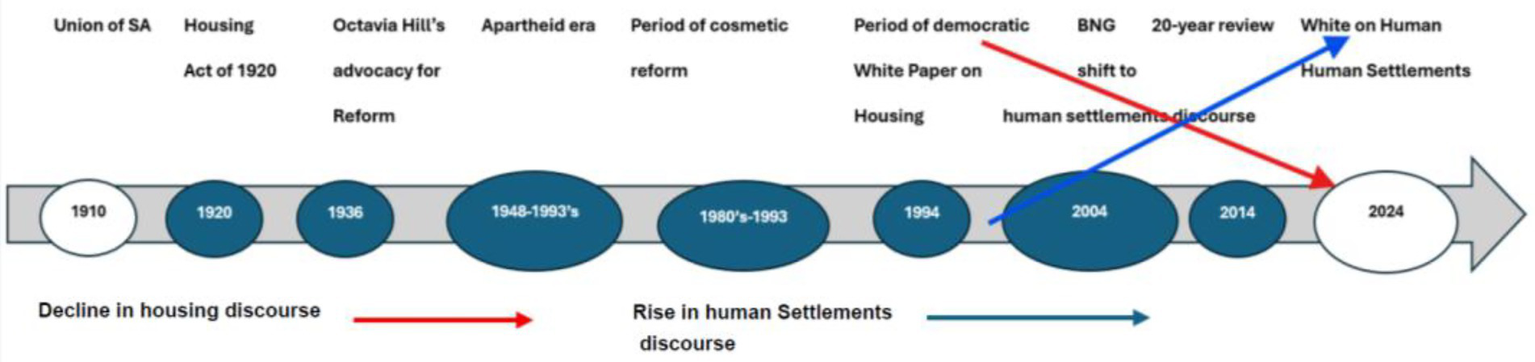

The entry of human settlements discourses into debates on housing and settlements transformation in the South African nomenclature is a recent affair. The earliest debates around the states’ provision of shelter dates to the early 1900s, when, just after the Union of South Africa, concerns for a rapidly urbanising population became a concern and so triggered discussions for housing provision by the state. Mabin (2020) has provided an exhaustive account of 100 years of housing legislation in South Africa, while Huchzermeyer and Karam (2016) have sketched a detailed timeline of the changes in the democratic period. Notwithstanding this detailed historiography of policy shifts and realignments, from housing to human settlements, nowhere in the literature has the distinctive contribution of the human settlements profession been clearly articulated. Hence, the purpose of this section of this article is not to narrate the history of housing and human settlements practice in South Africa, but to trace the evolution and change in discourse revolving around the provision of shelter to the current policy conception and the implications thereof.

Housing discourses, as distinct from other discourses including planning, architecture, and other cognate fields, have been part of South Africa since the emergence of housing-specific legislation. While planning discourses were highly technicist and often evoked notions of public health (Mabin, 2020), and later articulation of segregationist goals (Jeeva, 2023), the earliest traditions of housing advocacy and practice demonstrated a strong social welfarist orientation (Robinson, 1998). This welfarist ethos in housing discourses was influenced by the earlier social movements with their roots in colonialist welfarist traditions from the 1900s (Robinson, 1998), which impacted diverse colonial locales of New Zealand, the USA, and South Africa (Robinson, 1998; Spain, 2006; Mabin, 2020). The pioneering advocacy of Octavia Hill’s feminist social movement, from the English colonial centre, had a significant influence in opening pathways for a much more progressive housing reform centred on client-welfare, practitioner-client trust relationships, balancing against notions of social upliftment with a strong business management orientation within a system of tenant management. Critically, an important aspect of Hill’s influence was to advocate for the involvement of trained practitioners who became increasingly organised and professionalised in their work, through standardised training (Robinson, 1998). This social movement made an indelible impact on the nature and form of housing provision in South Africa from the mid-1930s onwards. This mantle of advocating for a professionalised housing sector gathered pace, and by the mid-1930s the Women Housing Managers emerged in the Cape guided by the Octavia Hill Institute’s training system. This system was a forerunner of later professional housing education models in South Africa. From the mid-1940s to the 1950s, a network of women practitioners was active across most large South African cities, fulfilling the roles of Assistant Housing Managers and Independent Housing Managers backed by state bursaries to ensure formal training. Under the impetus of practitioners themselves, namely, the Housing Manageress’s a South African Society of Women Housing Managers was established. The 1960s saw the emergence of the Society for Housing in South Africa, which became increasingly male-dominated one into the 1970s. Institute for Housing South Africa (IHSA) has, by the late 1980s and into the 1990s, assumed the mantle for representing housing practitioners in the country, and through its links to the UK-based Chartered Institute for Housing (CIH), its President, Mr. Mthethwa, forged a strong partnership to advance a professionalised housing sector in the early democratic period. By the early 1990s, the IHSA was a large-scale and highly influential professional association with a membership in excess of 1,500 members and with active branches in various provinces. It is worth noting that these historical trajectories played a pivotal role in shaping current competencies.

Academics and activists in the housing policy and practice arena, recognising this rich legacy, began codifying and sharing competency models, clarifying the roles of housing professionals (Van Wyk and Crofton, 2005). This triggered intense debate, both internal to the profession and from allied traditional professions, for and against the formalisation of the then housing profession. By the mid-2000s, the IHS collapsed due to funding constraints, leaving a vacuum, housing practitioners without a representative voice in the sector, as well as undermining the drive of the profession to full professionalisation.

On the policy front, South Africa has been, since the adoption of the BNG policy in 2004 (DoH, 2004), increasingly pivoting towards a discourse of human settlements (Adeniran et al., 2021). As correctly argued by Huchzermeyer and Karam (2016), the adoption of the BNG policy, as well as the later renaming of the Department of Housing to the Department of Human Settlements, indicated a shift away from earlier narrow conceptions of housing management policy implementation. This shift represented a major policy overhaul and widened the mandate of the then Department of Housing (DoH).

Around 2005, this professionalisation of housing was supported by CIH through a thorough scoping exercise and coincided with the emergence of discourses arguing for a shift to a wider mandate, away from housing management, in favour of notions of human settlements. Concurrently, the South African Qualifications Authority (SAQA) established a Standards Generating Body (SBG) process in the early 2000s to generate competencies and a nest of professional qualifications with a wide range of stakeholders covering human settlements.

The SGB process drew heavily on housing competencies in conceptualising and codifying human settlements educational qualifications. It follows then that current conceptions of human settlements profession draw on much older traditions of housing management practice (Van Wyk and Crofton, 2005). Thus, to a large degree, in SA, the human settlements profession draws strongly on competencies gleaned from housing management practice. See Figure 7 outlining key competencies.

Van Wyk and Crofton (2005) have documented and conceptualised core competencies of the then housing profession, which articulated eight overall areas, including general and project management, development management, business management, public management, coordination, consumer protection, development of policies, strategy, processes, and systems.

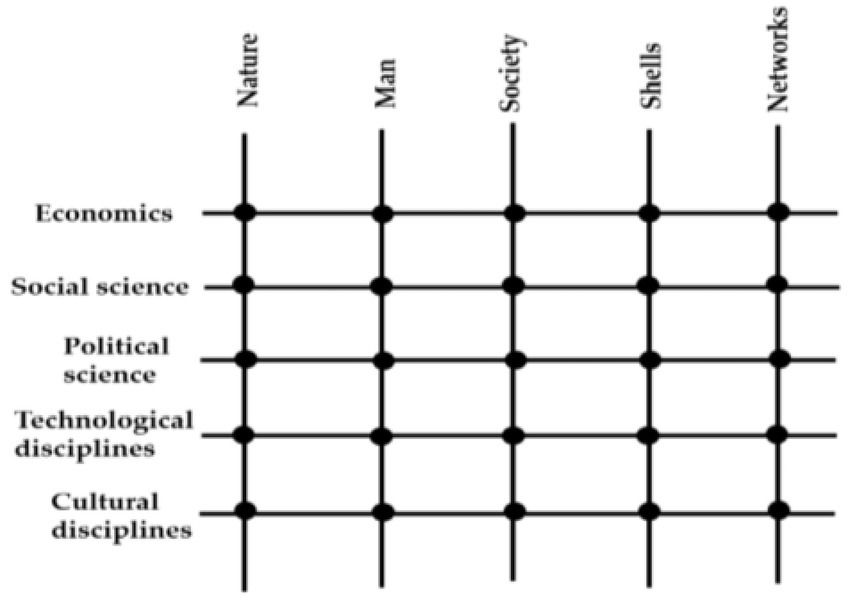

Independently from this more colonial influence, South Africa has been steadily embracing traditions which have completely different origins, namely, the science of human settlements, which has its roots in the Southeastern European country of Greece, where in the 1970s the planner-practitioner Doxiades, developed his wholistic conception of Ekistics also known as a science of human settlements (Doxiades, 1972) which has filtered into global discourses on human settlements planning, development and maintenance. By the mid-1990s the influence of the science of human settlements was extensive, impacting diverse cultures and locations from Europe, the East, and most significantly, China (Mao, 2019). Doxiades’ science of human settlements was premised on a matrix comprising 10 interwoven knowledge areas (Figure 8).

Figure 8

Matrix of knowledge areas forming a science of human settlements. Source: Liu et al. (2023).

By 2025, the transition to a discourse on human settlements was complete, as evidenced, by the promulgation of the White Paper on Human Settlements which cemented its premises and advocated its practical implementation in the SA moving forward. See Figure 9 for an illustration of the timelines depicting the transition to a human settlements centre policy discourse in SA.

Figure 9

Tracing the rise of housing and human settlements discourses in South Africa. Authors’ conception.

Notably, there has been a drop off in housing discourses since 2004 in favour of stronger conceptions of human settlements. The section which follows presents an analysis of human settlements-specific competencies by drawing on the body of literature known as the science of human settlements and adapting this to the South African situation by blending it with work by Van Wyk and Crofton (2005). Finally, this is cross-referenced with the more recent work of the IHSP-SA.

6.4.1 Comparative competencies and professional distinctiveness

As illustrated above, the human settlements profession has rapidly evolved over the last 20-year period, in response to a fast-changing environment, similar to other professions like planning (Sihlongonyane, 2018; Jeeva, 2023), and now occupies a unique and distinct position in the human settlements value chain in South Africa. This profession draws on a rich international intellectual and scholarly tradition grounded in a science of human settlements (Table 4).

Table 4

| Planning profession core competencies (SACPLAN, 2014) | Human settlements core competencies (Doxiades, 1972; Van Wyk and Crofton, 2005; IHPSA, 2022). | Competencies unique to human settlements |

|---|---|---|

|

Core competencies

*Settlement history and theory *Planning theory *Planning sustainable cities & regions *Urban planning & place making *Regional development & planning *Public Policy, institutional and legal frameworks, *Environmental planning & management *Transportation planning & systems *Land Use & infrastructure planning *Integrated development planning *Land economics *Social theories related to planning & development *Research |

Core competencies

* Human Settlements Theory & Practice * Development Management & * General and Financial Management * Property Development, * Property/Estate Management & Maintenance * ABT and IBT’s Innovation in material development, design & deployment * Stakeholder Management, Liaison & Coordination * Monitoring of Impact, Assessment & Evaluation * Research |

Professional gap

* Development Management *General & Financial Management *Property Development, Property/Estate Management & Maintenance *ABT and IBT’s Innovation in material development, design & deployment *Stakeholder Management, Liaison & Coordination *Monitoring of Impact, Assessment & Evaluation |

|

Functional competencies

*Survey & analysis *Strategic assessment *Local area planning *Layout planning *Plan making *Plan implementation *Participation & facilitation |

Functional competencies

*Human & Settlement Policy Design *Process management *Demographic analysis *Programme Management *Project Management *Stakeholder Coordination *Client Protection |

Functional gap

*Human Settlement Policy Design and Process management *Demographic analysis *Programme Management *Project Management *Stakeholder Coordination *Client Protection (DPME, 2020) |

Comparative competencies highlighting the competencies unique to the human settlements profession.

ABTs’, alternative building technologies; IBTs, alternative building technologies.

Comparing SACPLAN (2014) core planning competencies with those of the emerging Human Settlements profession underscores the latter’s distinctive integrative and managerial orientation. Whereas planners emphasise land use regulation, urban design, and environmental assessment (Sihlongonyane, 2018), HS practitioners combine policy design, demographic analysis, programme management, stakeholder coordination, innovation in alternative building technologies (ABTs/IBTs), and client protection (IHPSA, 2022). These competencies draw on both technical and social sciences and emphasise implementation within complex institutional systems. Consequently, the HS profession can be understood as a mediating profession with its own distinct knowledge fields yet traversing cognate specialisations between spatial planning, construction management, and social development to achieve sustainable, inclusive settlements outcomes (IHPSA, 2022).

This study underscores the fact that in South Africa, as debates around the provision of shelter have shifted for a housing orientation to a wider and complex human settlements mandate (DoH, 2004), it is evident that critical and often neglected functional areas including client protection, policy design and process management, demographic analysis capabilities, programme management, project management and stakeholder coordination align to this emerging profession remain under-serviced. The bulk of these areas align with the DPME and DHS sector capacity analysis of sector weaknesses (DPME, 2024; DHS, 2020). More critically, these areas are highlighted in the recent White Paper on Human Settlements, which specifically calls for the professionalisation of the human settlements sector going forward (DHS, 2025).

6.4.2 The role of human settlements professionalisation in reorienting institutional cultures

In South Africa’s post-apartheid governance landscape, professionalisation processes are closely tied to wider reforms in public administration (Jarbandhan, 2022). The National Development Plan NDP, 2012 and the National School of Government (NSG, 2022) articulate a vision for a capable, ethical, and developmental state. The professionalisation of the human settlements sector, within this broader framework (DHS, 2025), seeks not only to enhance technical competence but to reorient institutional cultures towards efficiency, quality, and client-centredness. These three interrelated drivers align with international debates on New Public Management (NPM) and developmental state models (Munzhedzi, 2021); however, Naidoo (2015) argues that they have been unevenly and inconsistently applied in South Africa.

6.4.3 NPM perspectives on efficiency

The local government sphere has embraced most of the principles of NPM, including the principles of decentralisation of powers, participatory planning, effective and efficient performance management, and financial service reform (Munzhedzi, 2021). Terrance and Uwizeyimana (2023) argue that the NPM advocated for public administration to adopt the private business management logic to implement business-like production and for public institutions to set performance management standards to enhance their efficiency. The implementation of HS professionalisation will, by necessity, be in alignment with this reorientation by establishing clear performance metrics, accountability mechanisms, and professional standards. An early indicator of the enhancements offered by professionalisation is the IHSP-SA’s continuous professional development (CPD) programmes, which aim to cultivate a results-oriented ethos by strengthening all human settlements aligned competencies for a focus on human settlements policy, ethics, project management, contract administration, and financial capacities. It must be pointed out that these programmes have secured limited uptake to date, undermining their systemic input. However, evaluations by the Department of Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation (DPME, 2020–2021) as well as the HSRC (2021) reveal persistent capacity gaps, especially at the municipal level, where weak coordination and political interference undermine performance (Windapo and Companie, 2022). Addressing these deficits requires institutionalising competence-based appointments and improving oversight through transparent procurement and evaluation systems. This, in turn, points to an ineffective implementation of the DHS’s capacity development strategy (DHS, 2020; Ramovha, 2022), which is closely aligned to the driver for professionalisation of human settlements (DHS, 2025).

6.4.4 The NPM perspectives on client-centredness

The NPM paradigm reframes service delivery as a collaborative process involving state, market, and community actors (Munzhedzi, 2021). In this regard, the HS profession’s focus on client protection, participatory planning, and community co-production aligns strongly with inclusive governance ideals. Initiatives such as a human settlements code of conduct, similar to the IHSP-SA’s ethical code, foreground responsiveness, social trust, and empowerment. Thus far, as the State Capture Commission (2022) and the SAHRC (South African Human Rights Commission, 2024) have shown, there is a high risk of political interference in the administration of public programmes, creating public distrust and revealing the need for ongoing professional formation rooted in transparency and citizen accountability.

6.4.5 The developmental state perspective on quality

From a developmental state viewpoint, professionalisation is a long-term investment in institution-building and ethical stewardship. Mpofana and Ruiters (2019) argue that a capable state requires trained career-minded professionals and policy and institutional stability. The DHS (2025) White Paper and NSG frameworks call for human settlements professionals who combine technical expertise with moral integrity, emphasising value-for-money delivery and sustainable outcomes. Quality, in this sense, extends beyond construction standards to include the durability of social and economic benefits derived from settlements projects. The emergence of human settlements degrees and research chairs at South African universities, such as Nelson Mandela University (NMU), University of Fort Hare (UFH), Mangosuthu University of Technology (MUT), University of the Free State (UFS), University of South Africa (UNISA), and Wits reflects a solid compact between the academy and the state to facilitate a developmental state committed to cultivating a technically skilled and ethically grounded professional cohort.

6.4.6 Cautionary notes to unbalanced professionalisation efforts

Efforts aimed at professionalising human settlements in South Africa must be nuanced, taking care to navigate various clear and present risks. These include the dangers of exclusion, over-bureaucratisation (Evetts, 1998), a counter-productive credentialism (Noordegraaf, 2016), as well as detachment from citizen-oriented co-created human settlements models (Majila, 2012).

The prime goal of professionalisation is to secure professional closure of an occupation (Larson, 1979). This ensures that only those who have specific skills, expert knowledge, and relevant specialist qualifications are allowed to enter a field of practice, thereby creating a monopoly (Shulman, 2005). It must be noted that the framing of knowledge as expert and technical, in itself, facilitates the empowerment and disempowerment of role-players in the professional project (De Satgé and Watson, 2018). In this endeavour, unintended consequences include creating unduly onerous barriers to entry, which could deter new entrants to the profession and artificially exclude those who are already in practice but lack human settlements-specific qualifications. It has been argued that professions may initially require market closure to be able to endorse and guarantee the education, training, experience, and tacit knowledge of licensed practitioners, but these processes later allow professions to concentrate on developing the service-oriented and performance-related aspects of their work (Halliday, 1987).

A second major risk to avoid is the triggering of over-bureaucratisation whereby the formalisation of the profession can entrench administrative rigidity, slow decision-making, negatively impacting service delivery processes (Ngwenya and Cirolia, 2021).

In addition, another risk area is that excessive credentialism may marginalise grassroots practitioners and community-based builders who possess valuable experiential knowledge. These factors taken together create a real risk that, if narrowly defined, professionalisation can reproduce elite technocracy. It is in this context that Noordegraaf (2016) warns that professionalism must continually evolve to balance formal competence with social legitimacy.

The delicate challenge is to professionalise without alienating key segments of current and potential practitioners and role-players. The emerging human settlements profession should therefore remain inclusive, reflexive, and practice-oriented—anchored in ethical codes that value both technical excellence and community responsiveness. In this regard, only a balanced approach towards professionalisation (Evetts, 2014) can serve the broader developmental purpose, namely, improving sector efficiency, and product quality at reduced costs while fostering trust, equity, and sustainability in the human settlements value chain.

7 Findings and discussion

What follows is a proposed leverage points through which professionalisation processes could enhance service delivery of human settlements in South Africa.

(a) Policy and legislative prospects for professionalisation

Professionalisation processes, with specific reference to HSM in the post-democracy context in South Africa, are both necessary and desirable objectives to enhance the quality and rate of service delivery to ordinary citizens (Van Wyk, 2016; Adeniran et al., 2021). South Africa’s National Development (NDP) deliberately highlights the overall objective of professionalisation of the public service as a key priority of the state to attain higher levels of state efficiency (NDP, 2012). Given the recent emergence of formalised frameworks for Professionalisation of the public service in South Africa, significant space exists to capitalise on the extensive work to professionalise housing, human settlements, and the urban management sector (NSG 2020; Jarbandhan, 2022). Morgan (1998) observes that some professions evolved as more or less independent self-regulating bodies, while others evolved as the result of statutory law. Moreover, with the publication of the White Paper, it appears that the emerging consensus to effect professionalisation in human settlements is the statutory avenue (DHS, 2025).

Additionally, the White Paper process to reform and realign human settlements policy has opened up a more direct pathway for discourses to formalise the human settlements profession by way of entrenching this objective in state policy frameworks (

DHS, 2025). Notwithstanding the opening up of space for public sector reforms to address professionalisation of SA public service, it must be noted that professionalisation processes with reference to human settlements development are longer term dynamic and systemic processes (

Mlambo et al., 2022) that can take many years even a few decades to mature and deliver tangible results.

(b) Institutional support for professionalisation of professionalisation

Professionalisation processes require sustained multi-actor effort, investment, and collaboration to reach fruition (Scartascini et al., 2013; Melnick, 2023). The Institutionalisation of professionalisation processes of human settlements management in South Africa can be defined as a long-term capacity development strategy, with multiple leverage points aimed at delivering a range of benefits to beneficiaries across and within the human settlements value chain.

While professionalisation efforts within the human settlements sector can be difficult to measure in terms of tangible outcomes, the emergence of an ecosystem of higher education institutions focused on advancing a coherent body of knowledge specific to the emerging science of human settlements (HSBok) is significant. Over the last decade, there has been a clear emergence of a network of universities in the SA higher education system offering human settlements specific qualifications (IHPSA, 2023). These institutions include NMU, UFH, UFS, MUT, and UNISA (Department of Human Settlements, 2015). More recently, Wits has entered this ecosystem by offering a Master of Science (MSc) course in Housing in Built Environment, while TUT has established a Research Chair in Human Settlements, respectively. The offering of 4-year professional degrees specialising in Human Settlements Development has guaranteed a pipeline of skilled professionals into the SA labour market. Over the past 5 years alone some approximately 1,000 graduates have been added to the human settlements sector (IHPSA, 2022). This represents a significant injection of skilled personnel with the most up-to-date training in the sector, addressing longstanding concerns with numerical capacity as well as personnel with a higher level of technical expertise and know-how.

Coupled to the above development has been the proliferation of Research Chairs directly linked to the development of human settlements specific bodies of knowledge via the dissemination of research output. In the last 10-year period, the establishment of several chairs in human settlements (or housing), including NMU, MUT, UKZN, and more recently at Tshwane University of Technology (TUT), represents a positive development, strengthening human settlements knowledge production, significantly contributing to the strengthening of institutional support for the professionalisation of human settlements.

A significant development in institutionalising the human settlements profession in SA has been the establishment of the Institute of human settlements practitioners. The emergence in 2020 of the IHPSA, as a not-for-profit voluntary association of human settlements practitioners, academics, activists, and students implementing human settlements, is a major milestone. This dynamic network of individuals who have self-organised around the project to professionalise human settlements in South Africa is a critical element in the emerging institutional framework to ensure more professional outcomes in the sector. This is an important marker that professionalisation processes are rapidly reaching maturity as the IHSP-SA mobilises a critical mass of members and becomes an important lobby for implementation of professionalisation processes. In addition, the IHSP-SA is triggering a culture of accountability and increased levels of trust by the development and enforcement of a code of conduct to guide members’ values and professional conduct. Another contribution of the IHSP-SA to sustain professionalisation processes is by playing the role of knowledge broker; here, the IHSP-SA’s continuous professional development (CPD) programme via its masterclass programme, together with its periodic conference initiatives, is filling an important gap of addressing sector knowledge management and capacity development. The IHSP-SA is also actively building national and international partnerships to sustain the emerging professional networks and diffuse international best practices within the human settlements sector in SA.

(c) Prospects for state agencies, the private sector, and NGO support for professionalisation efforts

A range of both statutory and non-statutory human settlements entities and organisations are emerging in support of more systemic professionalisation initiatives. The IHSP-SA has been at the forefront of mobilising entities such as the NHFC, NHBRC, SHRA, and NASHO. The IHSP-SA is pursuing both formal and informal partnerships with quasi-state entities and the private sector in support of systemic professionalisation of human settlements.

(d) International collaborations supporting more professional outcomes

The establishment of informal networks between the USA and African academics and practitioners in the Housing and human settlements space around 2019, which triggered the inaugural Pan African Symposium hosted by UKZN in 2021. These networks have been coalescing to drive enhanced collaboration by academics and practitioners in the USA and South Africa, and more broadly on the African continent. The more formal establishment of the USA–Africa Collaborative in 2022 as a legal entity registered in the USA and with a diverse and active Board is another marker that the is now a critical mass of support to sustain professional networks of housing and human settlements practitioners in SA and Africa (USA Africa Collaborative, 2024).

The IHSP-SA and its North African Counterpart NARHO, have been in talks to collaborate around nurturing networks of professional exchange, knowledge sharing, and reciprocal organisational support for the initiative of their respective programmes.

Taken together, there is a number of interesting prospects, namely, the following:

Policy and legislative prospects for professionalisation;

Institutional support for the professionalisation of human settlements;

International Collaborations supporting more professional outcomes; and

Prospects for private sector and NGO engagement.

These leveraging points are indicators of a rapidly evolving ecosystem of actors, agencies, and institutions that are in support of the professionalisation of human settlements development in South Africa.

8 Conclusion and recommendations

The professionalisation of housing, human settlements, and the urban development sector is critical to the SDG 11 and 8, namely the development of sustainable cities, communities, and inclusive urban growth (UN, 2015). The literature highlights the need for professional education in human settlements to underpin skills development of human settlements professionals, the promotion of regulatory reform through the creation of a human settlements professional body to guide the development of the profession, and implementation of controls for improved governance, and policy reform as fundamental to addressing inefficiencies in the sector.

In the context of South Africa, human settlements development has been evolving rapidly towards being fully recognised profession over the past three decades. This journey towards full recognition remains incomplete, with even older, more established traditional professions such as planning being unable to rest in any security (Anand, 2024). The intensity of the ongoing battles for legitimacy in what is perceived to be a “crowded” built environment suite of professions is such that, even traditional disciplines like planning have sought to reform away from unwanted past perceptions of being vestiges of colonial modalities of command and control (Chakwizira, et al., 2024). Thus, it is within this milieu that the human settlements professional project has remained highly contested, with no guarantee that the primary objective of emerging as a fully recognised profession with a representative professional council is assured.

Notwithstanding its fits and starts and fissures, debates around human settlements’ specific professionalisation and the potential benefits that this process will yield are likely to intensify since the publication of the new White Paper on Human Settlements in South Africa.

Given South Africa’s myriad social and development challenges, discourses around enhancing professionalisation across all professions have been seen as part of the solution to state atrophy with regard to service provision. Consequently, traditional vocations as diverse as planning, law, and real estate have seen rapid reforms aimed at professional transformation. These reforms have reshaped institutional forms, such as in planning, where the South African Council of Planners (SACPLAN) has only recently emerged. This body has tightened and clarified entrance requirements as has happened for Real Estate Agents via the Property Practitioners Regulatory Authority (PPRA), or the stricter enforcement of proof of professional registration for teachers by the South African Council for Educators (SACE), or more centralisation as has happened in the discipline of law with the emergence of the Legal Practice Council (LPC).

Despite the diversity of rationales, driving factors, and processes to enhance or advance specific professions, reforms to strengthen existing and new professions are numerous. While this article does not propound the “Professionalisation of everyone?” as Wilensky (1964) classic rhetorical article puts forward, it argues that traditions as well as specific histories of professionalisation remain understudied in South Africa. It is in this vein that this article seeks to make a contribution to scholarship that critically examines the human settlements professional project in South Africa.

It is contended, therefore, that by investing in sector-wide systemic professionalisation initiatives and institutional development, the state and its partners can dramatically improve the efficiency (delivery rate, quality, and value for money) of human service delivery in rapidly urbanising regions like South Africa.

Future research pathways emerging from this article are numerous and include:

What are the perceptions of human settlements practitioners of sector professionalisation?

How will professional closure impact the pipeline of entrants to human settlements, and to what degree will local government struggle to recruit suitably trained professionals?

What pathway should this professionalisation project take: Should it be state-driven, association-led, or cocreated?

While cautious of viewing professionalisation as a panacea, this study makes the case for a more deliberate and concerted effort in this direction.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

BB: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SM: Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Ackerman C. (2016). Evaluating integrated human settlements by means of sustainability indicators (doctoral dissertation, North-West University (South Africa), Potchefstroom campus).

2

Adeniran A. A. Mbanga S. Botha B. (2021). A framework for the management of human settlements: Nigeria and South Africa as cases. Town Reg. Plan.78, 1–15.

3

Anand G. (2024). Practicing within and beyond planning: narratives of practitioners from South Africa. Plan. Pract. Res.39, 223–238. doi: 10.1080/02697459.2023.2244310

4

Arndt C. Davies R. Thurlow J. (2018). Urbanization, structural transformation, and rural-urban linkages in South Africa. South African Urbanisation Review, Cities Support Programme (CSP) of the National Treasury35, 1–24.

5

Artuso F. Guijt I. (2020). Global megatrends: Mapping the forces that affect us all (Oxfam Discussion Paper). Oxford, UK: Oxfam GB. doi: 10.21201/2020.564

6

Boyce B. P. (2024) Elevating a culture of ethical conduct in human settlements sector. The role of the IHSP-SA, presentation to IHSPSA Masterclass at Central University of Technology, 28th of November 2024.

7

Bradlow B. Bolnick J. Shearing C. (2011). Housing, institutions, money: the failures and promise of human settlements policy and practice in South Africa. Environ. Urban.23, 267–275. doi: 10.1177/0956247810392272

8

CIH-UK . (1997) Scoping report on the professionalisation of housing and human settlements in South Africa. Report to the Department of Housing, Pretoria (unpublished internal report)

9

Chakwizira J. Mashiri M. Tshivhase F. (2024). Sustainable and resilient priority human settlement development areas: A case of Msukaligwa local municipality, South Africa. Paper presented at FIG Working Week 2024, Accra, Ghana. Available online at: https://www.fig.net/resources/proceedings/fig_proceedings/fig2024/ppt/ts10d/TS10D_chakwizira_mashiri_12686_ppt.pdf

10

Companie F. (2020). Evaluation of the challenges to project delivery confronting project leaders in the dynamic human settlement environment (master thesis). University of Cape Town.

11

Department of Human Settlements . (2015). Annual report 2014/2015 (RP236/2015). Pretoria: Government Printer.

12

De Satgé R. Watson V. (2018). Urban planning in the global south: Conflicting rationalities in contested urban space. Berlin: Springer.

13

DHS . (2014). Budget speech of National Minister of human settlements. Pretoria SA: Department of Human Settlements, Pretoria.

14

DHS . (2016). Department of human settlements. Annual report 2015/2016 (RP no. 324/2016). Pretoria: Government Printer.

15

DHS . (2019). Department of Human Settlements. Annual report 2018/2019 (Vote 38). Pretoria: Government Printer. Available online at: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201911/human-settlements-1819.pdf

16

DHS . (2020). Department of Human Settlements, Human Settlements Sector Capacity Development Strategy. In Strategic Plan 2020–2025. Pretoria: Government of South Africa. Retrieved fromhttps://www.humansettlements.fs.gov.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/STRATEGIC%20PLANS%208-8-2020%20CONVERTED%20TO%20PDF.pdf

17

DHS . (2024). Department of Human Settlements, Minutes of meeting: National Work Group on professionalisation. Pretoria, South Africa.

18

DHS . (2025). White paper on human settlements, National Development of human settlements. Pretoria: Government Printers.

19

DHS . (2013). Speech by Human Settlements Minister, Mr Tokyo Sexwale, on the occasion of the establishment of the Chair for Education in Human Settlements Development Management at the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University - 19 March 2013.

20

DoH . (1994). Department of Housing. White paper: A new housing policy and strategy for South Africa (government gazette Vol. 354, no. 16178, general notice 1376 of 1994). South Africa: Government Printer.

21

DoH . (2004). Breaking New Ground: A comprehensive plan for the development of integrated sustainable human settlements. Department of of Housing, Pretoria: Government of South Africa. Available online at: https://www.dhs.gov.za/sites/default/files/documents/26082014_BNG2004_0.pdf.

22

Doxiades C. A. (1972). Ekistics, the science of human settlements. Ekistics, 237–247.

23

DPME . (2024). Report on the design and implementation evaluation of priority human settlements and housing development areas, Department of Monitoring and Evaluation. Pretoria: Government Printers.

24

Evetts J. (1998). Professionalism beyond the nation‐state: international systems of professional regulation in Europe. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy18, 47–64.

25