Abstract

Introduction:

South Africa continues to face a significant housing crisis characterized by a growing backlog, unaffordability, and spatial inequality. Although state-led interventions such as the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) and the Finance Linked Individual Subsidy Programme (FLISP) have improved access for low-income households, these initiatives have not adequately addressed the housing needs of the missing middle, nor have they fully leveraged private sector participation. This article investigates how tax credits can complement existing housing programs, including BNG, FLISP, and informal settlement upgrading initiatives. The South African government is seeking innovative, scalable, and financially sustainable approaches to address the housing crisis. Tax-based incentives, particularly housing tax credits, represent a promising but underutilized strategy.

Methodology:

This article conducts a systematic literature review to assess the effectiveness of tax credit mechanisms in promoting affordable housing. The analysis primarily draws on international case studies, including the United States’ LIHTC program. The review covers peer-reviewed articles, government policy documents, and institutional reports published between 2010 and 2024. The PRISMA framework and Participatory Design principles guide the review to ensure transparency and replicability.

Results:

The findings reveal that tax credit programs have successfully mobilized private investment in affordable housing in several countries, particularly when supported by strong regulatory oversight, clear eligibility criteria, and alignment with spatial planning frameworks.

Discussion:

However, implementation challenges remain, including market capture, the exclusion of the poorest households, and administrative complexity. In South Africa, although limited tax incentives, such as Urban Development Zone (UDZ) tax deductions, are available, they have not been specifically tailored to incentivize the delivery of affordable housing. This article proposes a SA-AHTC model to complement existing housing subsidies. The model aims to attract private capital to mixedincome and rental housing in high-demand urban areas, responding to the growing trend of urbanization. The proposal emphasizes integration with local government planning, outcome-based compliance systems, and continuous monitoring to promote equity and effectiveness. The analysis demonstrates how well-designed tax credit frameworks can align public policy objectives with market-based solutions. Incorporating tax credits into a broader, equity-focused housing strategy could expand access to affordable shelter and support inclusive urban development.

1 Introduction

South Africa’s constitution guarantees access to adequate housing, but as of 2021, there was still a shortfall of 3.7 million units (Daily Maverick, 2022). Since 1994, programs such as the Reconstruction & Development Programme (RDP) and Breaking New Ground (BNG) have built over 5 million houses; however, they have not kept pace with the rapid urban growth (Housing Development Agency, 2023). Recent budget cuts have further limited the number of new homes that can be built. Across Africa, cities have been working to meet the growing need for improved infrastructure and affordable housing, particularly since the 1950s (Kamana et al., 2024). After 1994, the South African government launched the RDP to address past inequalities by providing free, state-subsidized homes to low-income families. Despite delivering millions of houses, critics note that the RDP has contributed to urban sprawl and ongoing spatial inequality, and it still falls short of meeting demand (Charlton and Meth, 2017; South African Institute of Race Relations, 2021).

Even with large grants and subsidies, relying mostly on government funding has made it hard for the state to reduce the housing backlog (Shisaka Development Management Services, 2020). The RDP approach led to many homes being built in black townships, which kept old spatial patterns from apartheid in place. This means many families still live far from jobs and city centers. The Department of Human Settlements now reports a backlog of about 2.4 million homes (Housing Development Agency, 2023). Rapid urbanization has exacerbated this issue: more than two-thirds of South Africans now reside in cities, and this trend is expected to continue (Stats SA, 2022). As people move to cities for work and services, informal settlements have grown rapidly, often lacking basic infrastructure and decent living conditions (Turok and Borel-Saladin, 2016). This puts more strain on municipal services. While most households reside in formal homes, approximately 8% live in informal structures, and 3% live in traditional dwellings (Department of Human Settlements, 2023a).

To address these issues, the government has implemented several programs, including FLISP, Human Settlements Development Grant (HUDG), Upgrading of Informal Settlements Development Grant (UISPG), and Municipal Human Settlements Capacity Grant (MHSCG). FLISP helps families who earn too much for RDP housing but not enough to get a mortgage (Department of Human Settlements, 2023b). Still, these subsidies have not fully closed the gap for households in the missing middle, earning between R3,500 and R22,000 per month (CAHF, 2022; Department of Human Settlements, 2023c). Many in this group, especially those earning between R3,500 and R7,500, find it challenging to secure mortgage loans because there are few suitable housing options and almost no mortgage products available to them. Relying mainly on public funding is unsustainable, so there is a need to explore market-based solutions. Tax credits are one option. They reduce tax bills for people or companies who invest in projects that benefit society. In housing, tax credits can encourage private developers to build affordable homes by reducing their tax liability when they invest in qualifying projects (United States Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2011).

This article examines how tax credits could complement existing housing programs, such as BNG and FLISP, as well as efforts to upgrade informal settlements, thereby accelerating the delivery of affordable homes in South Africa. It suggests that working with the private sector through well-designed tax credits is key to easing the state’s financial load and increasing housing supply. The paper recommends a tax credit system with strong public oversight, built into existing subsidies, and focused on both spatial and social goals. If implemented, this approach could help the National Treasury establish a more sustainable and equitable way to promote affordable housing. Using tax incentives to attract private investment may help reduce the housing backlog and better meet the needs of South Africa’s rapidly growing cities (National Treasury, 2021a, 2021b).

2 Methodology

A Systematic Literature Review (SLR) was conducted using the PRISMA 2020 framework to evaluate the potential of housing tax credits in addressing affordable housing challenges in South Africa. The research design incorporated Participatory Design (PD) principles to ensure that the conceptual framework, particularly the proposed South African Affordable Housing Tax Credit (SA-AHTC) model, addresses user needs, governance, and implementation as identified in the literature. Participatory design is a collaborative methodology that actively involves stakeholders, particularly end-users, in the design process to align outcomes with user needs, preferences, and contexts. This approach emphasizes democratic involvement, mutual learning between designers and users, and shared decision-making throughout the design cycle (Bødker et al., 2004; Creswell and Plano Clark, 2018).

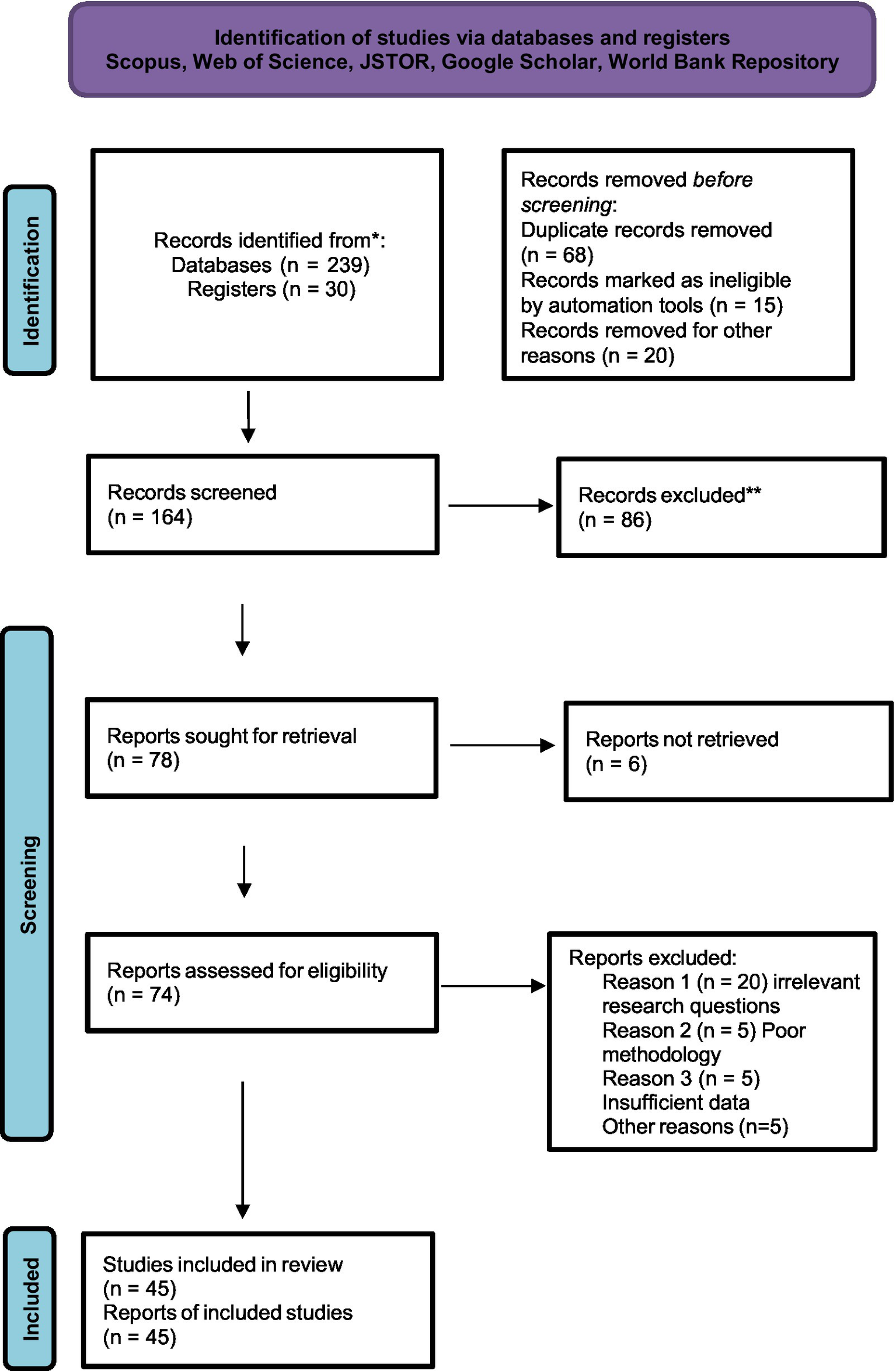

The article employs a pragmatist approach, integrating multiple methods, perspectives, and sources of evidence, and is informed by constructivist and social justice perspectives (Kaushik and Walsh, 2019). This methodological design combines the rigor of systematic review with participatory inclusivity, ensuring the SA-AHTC model is both evidence-based and contextually relevant. The PRISMA framework was selected to enhance transparency, replicability, and methodological rigor in synthesizing global and local housing finance strategies, including tax-based incentives. The literature search included databases such as Google Scholar, ScienceDirect, JSTOR, and the World Bank Open Knowledge Repository. Keywords used were ‘affordable housing,’ ‘tax credits,’ ‘South Africa,’ ‘Low-Income Housing Tax Credit,’ ‘urban development,’ ‘housing finance,’ ‘public-private partnerships,’ and ‘policy innovation.’ Inclusion and exclusion criteria were based on topic relevance. Sources comprised peer-reviewed journal articles, government policy documents, institutional reports, and case studies from 2010 to 2024 that addressed tax credit frameworks, affordable housing policies, blended finance, and participatory housing programs. Non-English publications, commentary articles without methodological grounding, and sources lacking full-text access were excluded. The initial search identified 239 records. After deduplication and abstract screening, 78 full-text articles were reviewed, with 45 meeting the inclusion criteria. The selection process followed PRISMA guidelines and is illustrated in a flow diagram (Figure 1). Thematic synthesis identified common patterns and policy-relevant insights. Although direct participatory engagement was not conducted, PD principles informed the interpretive lens during model development. This approach enabled the SA-AHTC model to reflect stakeholder perspectives and align with rights-based and inclusive planning in both South African and international housing policy.

Figure 1

Prisma template. Source: Page et al. (2021), Mvuyana (2025).

3 Theoretical framework

The article adopted the Housing Rights Theory in addressing the strategies adopted to address affordable housing challenges. The Housing Rights Theory is grounded in the recognition of adequate housing as a fundamental human right and an essential component of human dignity, social justice, and sustainable development. Several international legal instruments have acknowledged that housing is a fundamental human right. Hence, Article 25(1) of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), affirms that “everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care” (United Nations, 1948). Furthermore, Article 11(1) of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) underscores the right of all individuals to “adequate housing” as part of the right to an adequate standard of living (United Nations General Assembly, 1996).

The United Nations has recognized that housing rights extend beyond the mere provision of shelter to include security of tenure, affordability, accessibility, habitability, and cultural adequacy (UN-Habitat, 2014). These dimensions emphasize that housing should not be understood narrowly as the physical structure of a dwelling, but rather as a right that ensures dignity, safety, and participation in community life (Hohmann, 2013). This has been emphasized by the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights that states have an obligation to progressively realize housing rights through legislative, policy, and budgetary measures while protecting individuals from forced evictions and homelessness (Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 1991).

In practice, the housing rights theory challenges market-driven approaches that treat housing as a commodity instead of a social good. Scholars argue that commodification can worsen inequality and exclusion. This often leaves groups such as the urban poor, women, migrants, and people with disabilities without adequate housing access (Rolnik, 2019). A rights-based approach views housing as a public responsibility. It requires state accountability and citizen participation in policymaking (Farha, 2016). In the South African context, housing rights theory has become more prominent due to constitutional recognition. Section 26 of the Constitution of the RSA guarantees the right of everyone to access adequate housing. It also requires the state to take reasonable legislative and other steps, using available resources, to realize this right over time (The Republic of South Africa, 1996).

4 Historical housing typologies and programs in South Africa

South Africa’s housing landscape is complex, shaped by the legacy of apartheid and ongoing socio-economic challenges (Marutlulle, 2022). Numerous efforts have been made by the South African government to address housing inadequacies through various programs; however, significant challenges remain. These include the persistence of informal settlements, public health concerns, shack fires, flooding, violence, corruption, and xenophobia (Marutlulle, 2021). Such obstacles have hindered progress in improving the quality of life for underprivileged households. Although the realization of housing as a human right is mandated by the South African Constitution of 1996, the government has struggled to fulfil this commitment, despite the mass production of housing (Mchunu and Nkambule, 2019). This has led the South African government to initiate several programs aimed at realizing adequate housing as a human right. This section explores the various approaches adopted by the government to address housing challenges in the country and considers how innovative financing models can contribute to improving housing delivery.

4.1 Reconstruction and development programme (RDP) as a socio-economic policy framework

Following the 1994 elections, the African National Congress (ANC) introduced the RDP to redress apartheid-era inequalities by delivering essential services, including housing, water, electricity, and sanitation, to low-income households (African National Congress, 1994). As the initial socio-economic policy of post-apartheid South Africa, the RDP aimed to resolve infrastructural deficits and entrenched social inequalities. The ANC pledged to construct one million affordable houses within 5 years, prioritizing historically marginalized and impoverished communities. Standardized, free-standing units measuring 30 to 40 square meters were constructed on individual plots and equipped with basic services (Charlton and Kihato, 2006).

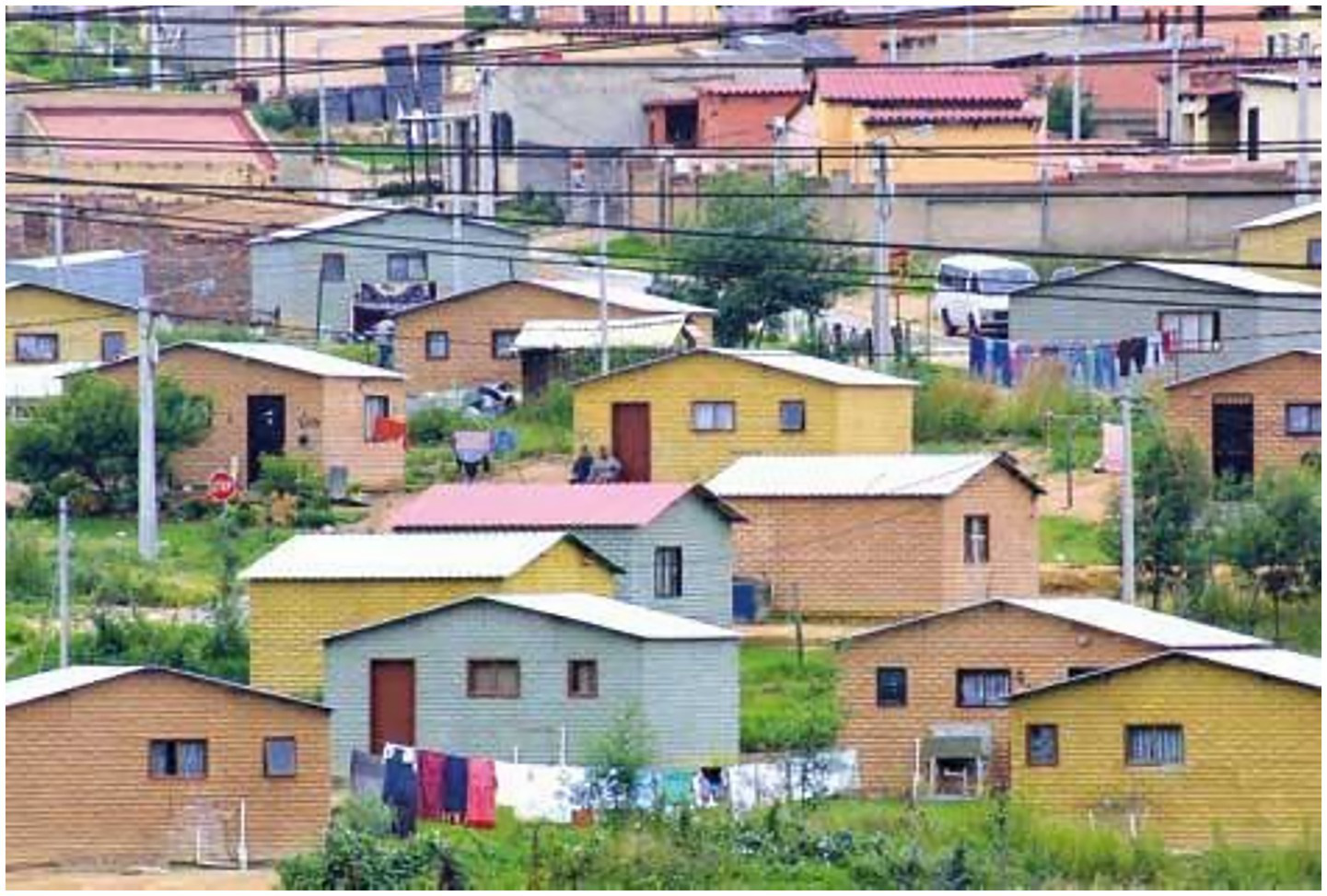

The RDP delivered over four million state-subsidized homes and secured tenure rights in the Constitution. National government allocations primarily funded the programme, concentrating large-scale housing production in black townships. This approach unintentionally reinforced the spatial segregation established during apartheid. Although extensive, the RDP contributed to urban sprawl and sustained spatial inequalities. The programme did not meet housing demand, and persistent backlogs further exacerbated this shortfall (Charlton and Meth, 2017; Shisaka Development Management Services, 2020; Mhlongo et al., 2022). RDP housing was approved in accordance with Department of Housing norms, as outlined in the 1997 Housing Act. Households earning less than R3,500 (approximately $194) per month qualified for a full subsidy. RDP houses became symbols of the state’s commitment to correcting historical spatial and housing inequalities, providing hope to many low-income families who previously could not afford homeownership (Tissington, 2011) (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

RDP housing type. Source: Youth Village (n.d.).

The strategy resulted in large-scale housing production in black townships, which perpetuated spatial segregation from the apartheid era. Locating many houses on the urban periphery reinforced geographic marginalization. Uniform design standards, substandard construction quality, and limited community participation in planning processes further undermined the program. The RDP exposed significant weaknesses in municipal capacity and governance, impeding the development of integrated and sustainable human settlements. Although the program addressed immediate housing needs, its focus on quantity and peripheral locations created long-term fiscal challenges for municipalities and sustained spatial inequalities (Huchzermeyer, 2003, 2011; Behrens and Wilkinson, 2003; Charlton, 2003; Scheba and Turok, 2021; Van Donk and Pieterse, 2006).

4.2 Breaking new ground as a comprehensive plan for housing development

The BNG policy, formally the Comprehensive Plan for the Development of Sustainable Human Settlements, was adopted in 2004 and represented a significant evolution in South Africa’s housing strategy. The policy sought to address the limitations of the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) by promoting integrated, sustainable, and equitable urban development (Department of Housing, 2004). BNG shifted the focus from the RDP’s emphasis on quantity and basic shelter to prioritizing quality, sustainability, and spatial integration. It promoted the development of mixed-income, mixed-use, and spatially integrated settlements to address the spatial fragmentation resulting from apartheid-era planning (Charlton and Kihato, 2006). This comprehensive strategy aimed to link housing provision to broader social and economic opportunities, as noted by Smit (2006), positioning housing as an instrument for development. The policy also emphasized incremental housing development, enabling residents to improve their homes over time. These objectives are aligned with poverty alleviation, economic development, and spatial justice, directly addressing issues neglected under apartheid.

The BNG policy prioritized community participation, intergovernmental coordination, and capacity building at the local government level. However, implementation frequently relied on top-down delivery models, which limited engagement with affected communities (Parnell and Pieterse, 2010). This limited participation hindered the planning of large-scale housing developments, as many projects did not adequately address community needs. Municipal frameworks advocate for full participation, yet insufficient involvement persisted. Turner (1976) emphasizes that effective participation requires residents to control major decisions and contribute to the design, construction, or management of their housing. Genuine participation is essential for both individual and social well-being. BNG also addressed urban informality by prioritizing incremental housing development, which enables residents to improve their homes over time. This strategy directly responded to the shortcomings of apartheid-era policies in poverty alleviation, economic development, and spatial equity. A central feature of BNG was its focus on in-situ upgrading of informal settlements, consistent with the rights-based and participatory approaches promoted by international frameworks, such as the United Nations’ Habitat Agenda. Rather than pursuing demolition and relocation, BNG supported the upgrading of existing communities by providing essential services and tenure security (eThekwini Municipality, 2016; Tissington, 2011). As urbanization increased and land availability declined, recognizing informal settlements became increasingly important. This recognition led to the launch of the Upgrading of Informal Settlements Programme (UISP) in 2004, marking a significant policy shift that acknowledged informal settlements as a permanent aspect of urban development and aligned with global best practices (Department of Housing, 2004; Huchzermeyer, 2009).

A central innovation of the BNG policy was its emphasis on in-situ upgrading of informal settlements, consistent with participatory and rights-based approaches advocated by international frameworks such as the United Nations Habitat Agenda. Rather than pursuing demolition and relocation, BNG promoted the improvement of existing communities by providing essential services and tenure security (Tissington, 2011; Socio-Economic Rights Institute of South Africa, 2018). Ongoing urbanization and limited land availability contributed to the continued expansion of informal settlements in metropolitan areas. In response, the DHS introduced the UISP in 2004 as a sub-programme of BNG. This initiative represented a significant policy shift by formally recognizing informal settlements as a permanent component of urban development, rather than as illegal occupations to be eliminated (Department of Housing, 2004). The UISP approach aligns with international best practices, particularly the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat) participatory slum upgrading model and affirms the agency of informal settlement residents (Huchzermeyer, 2009) (see Figure 3).

Figure 3

Mixed-use housing development (City of Ekurhuleni, 2021).

The City of Ekurhuleni in Gauteng, South Africa, demonstrates a strong commitment to the BNG policy (City of Johannesburg (CoJ), 2019). According to the City of Ekurhuleni (2021), the initiative aims to expedite planning approval for social housing complexes strategically located within 800 meters of Bus Rapid Transport (BRT) stations. In underserved areas, the city collaborates with the Department of Transport to connect peripheral settlements to the BRT route. This approach is mirrored by other metropolitan areas in South Africa, ensuring that social housing units address the urgent needs of the community. As a result, similar projects are being implemented nationwide, transitioning from pilot initiatives to established policy (City of Johannesburg (CoJ), 2019). Despite its significance, the BNG program faces several challenges. These include limited institutional capacity at the municipal level, persistent spatial segregation that distances new projects from economic opportunities, and a disconnect between policy objectives and practical realities such as budget constraints, political factors, and land availability (Mabin, 2020; Tomlinson, 2015). The BNG remains a central policy for advancing sustainable and equitable human settlements. However, inadequate stakeholder participation and reduced housing unit construction due to insufficient national funding have hindered its effectiveness. Addressing these challenges is necessary to improve the program’s impact.

4.3 Finance linked individual subsidy program (FLISP), 2005 as a strategy for middle income financing

The FLISP was established by the South African government in 2005 as part of a comprehensive human settlements strategy. Unlike other housing initiatives, FLISP targets middle-income earners, commonly referred to as the gap market. These households earn incomes that exceed the threshold for fully subsidized housing but are insufficient to independently secure traditional mortgage finance (Department of Human Settlements, 2005). FLISP offers a one-off, non-repayable housing subsidy to eligible individuals or households with monthly earnings between R3,501 and R22,000 ($1,249). The subsidy is applied to reduce the principal loan amount of a mortgage or to serve as a deposit, thereby enhancing the affordability and accessibility of homeownership (National Housing Finance Corporation, 2020). FLISP has addressed the affordability gap for households previously excluded from the formal housing market, supporting the constitutional right to affordable housing. Rust (2011) notes that FLISP has met the needs of the expanding urban middle class, which is economically active but often excluded from homeownership due to high property prices, limited savings, and restricted access to credit (Rust, 2011). This underscores the necessity for collaboration between financial institutions and the government to achieve affordable housing objectives.

FLISP was also designed to support a transition from a uniform subsidy model, previously adopted in South Africa, to a diversified, market-linked housing delivery system as outlined in the BNG policy framework (Department of Housing, 2004). Despite these intentions, scholars such as Tissington (2011) and Scheba and Turok (2020) have identified several implementation challenges, including limited public awareness, complex application processes linked to mortgage approvals, and a shortage of affordable housing stock in well-located urban areas. Municipalities, in partnership with financial institutions, are responsible for implementing these programs to ensure that the underserved market is adequately served. FLISP aims to support the state’s commitment to fostering sustainable human settlements, enabling broader participation in the property market, and facilitating the accumulation of generational wealth among the missing middle. However, effective access to the housing market requires a comprehensive understanding of the broader socio-economic environment in which these initiatives operate.

5 United States low income housing tax credits background

The U.S. LIHTC program, enacted through the Tax Reform Act of 1986, which has become one of the nation’s core tools for subsidizing affordable rental housing within the capitalist framework (Schwartz, 2015; Scally et al., 2018). By allowing private developers to monetize tax credits in exchange for affordability restrictions that typically require 20–40% of rental units to be set aside for households earning ≤60% of the Area Median Income (AMI), the LIHTC has underwritten approximately 3 million rental homes since its inception (United States Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2022). However, several structural limitations persist: (a) Temporal Affordability: LIHTC affordability requirements generally expire 15 to 30 years after project completion. Without renewed subsidies or policy interventions, previously affordable units may convert to market-rate housing, leading to gradual displacement (Freeman, 2020; O’Regan and Horn, 2013); (b) Geographic Concentration: While designed to target low-income areas, LIHTC developments are often located in neighbourhoods with limited opportunity access, perpetuating spatial inequality. In contrast, land scarcity in transit-rich or climate-resilient areas restricts inclusive placement. Consequently, public investment may become a magnet for speculative pressures in marginalized communities, accelerating gentrification (Ellen and Horn, 2018; Lens and Reina, 2016); (c) Lack of Formal Recognition of Informal Housing: The LIHTC framework systematically excludes informal or non-traditional housing types such as containers, tents, vehicles, and makeshift shelters even though these meet urgent housing needs. These structures symbolize both deprivation and community resilience yet remain unsupported due to their lack of formal zoning or recognition of tenure. Their exclusion from affordability policies and subsidy frameworks hinders the potential for bottom-up transformation of urban equity (Desmond, 2016; Roy, 2005; Tobias and Edward, 2025). By situating the LIHTC model within a human rights and sustainability paradigm, this paper proposes a reorientation of the U.S. affordable housing discourse toward greater integration of equity, resilience, participatory design, and formal-informal hybridity as a more progressive South African model.

The U.S. Department of HUD states that housing tax credits serve as an indirect federal subsidy, financing the development of affordable rental housing for low-income households. Administered by state housing agencies, these credits allow private developers to offset income tax liabilities in exchange for maintaining long-term affordability for their units (HUD, 2011). Although South Africa offers tax incentives to private developers, these do not include public housing constructions funded through the BNG programme. While the U.S. LIHTC model has been successful in mobilizing private investments, it also faces criticism regarding its complexity and potential market capture, which can marginalize the lowest-income households (Schwartz, 2015; United States Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2011). It is essential to ensure that tax credits are effectively implemented, which underscores the need for strong governance throughout the process. Currently, South Africa lacks tailored tax incentives aimed specifically at affordable housing. Existing tools, like the Urban Development Zone (UDZ) deductions, have limited impact on low-income groups (National Treasury, 2021a). Acknowledging this gap, the NT emphasizes the exploration of these opportunities to fulfil the affordable housing mandate enshrined in the Constitution. Improving the availability of affordable housing units can effectively reduce the backlog.

6 Discussion and findings

6.1 Comprehensive plan for sustainable cities

The report from the World Economic Forum (WEF) highlights the significant challenges that many cities face, including limited institutional capacity, insufficient private sector engagement, restricted access to international financing, and inadequate emergency funding (WEF, 2022). These challenges affect a country’s ability to provide essential services, including affordable housing, which is crucial for improving the quality of life. Large-scale development projects often take years to materialize and involve a range of stakeholders, creating systemic challenges for social value creation, even among those committed to the cause. Therefore, a structured and intentional approach is necessary to achieve transformative goals (WEF, 2024).

In South Africa, notable mega projects, such as those undertaken by the City of Ekurhuleni, demonstrate a strong commitment to the BNG initiative (City of Ekurhuleni, 2021). Tax credit mechanisms present a promising opportunity for facilitating affordable housing development, yet various implementation challenges remain. Municipalities are responsible for ensuring housing development occurs within their jurisdictions; however, they often encounter planning backlogs, limited technical capacity, and fragmented budgetary frameworks (Maila, 2024; Maila et al., 2024). This has contributed to a decrease in the number of housing units constructed and a slowdown in addressing the housing backlog. To address the limited resources that governments face in providing housing for the underserved, tax credits can function as an effective alternative. The UN describes tax-based incentives as a useful strategy for attracting private capital to affordable housing, particularly in scenarios where public funding is limited. These measures can enhance affordability when carefully targeted to avoid market distortions and ensure that benefits reach low-income groups (UN-Habitat, 2020a).

Global literature suggests that for tax incentives to be effective, they should be supported by a stable regulatory environment, technical assistance for small developers, and clear allocation frameworks (United States Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2021; CAHF, 2023). In South Africa, fragmented governance and municipal capacity constraints currently impede the scaling up of affordable rental stock (Ngwenya, 2024). If tax credits are implemented in South Africa, it will be crucial to incorporate institutional coordination mechanisms and eligibility frameworks that ensure participation from diverse actors. This approach highlights the importance of an inclusive strategy that enhances municipal capacity to implement tax credits and increase government revenue. Scholars argue that integrating tax incentives with direct public investment and community-driven contributions, as exemplified in hybrid financing models in Mexico and the Philippines, can yield positive outcomes (Patel and Mitlin, 2010; Rust, 2011). Adopting similar approaches may significantly enhance community well-being. To ensure full private sector participation in housing development, targeted incentives are necessary. The South African government should consider alternative strategies to increase fiscal resources beyond raising taxes. Although there have been proposals to increase taxes to address competing priorities, high unemployment and a limited tax base constrain this approach. Nevertheless, opportunities remain for the government to generate additional revenue streams, including through housing initiatives. Implementing such measures would require strengthening the real estate sector’s capacity to understand and effectively apply tax credits (Global Property Guide, 2024).

6.2 Integration with local government planning

Effective urban development requires the formation of broad coalitions of local stakeholders that extend beyond formal public–private partnerships. Such collaboration establishes a foundation for generating social value through a shared vision, as indicated in the World Economic Forum (WEF) report (2024). The report emphasizes the importance of establishing relationships with stakeholders impacted by urban development to improve the community’s quality of life. The Centre for Affordable Housing Finance in Africa (CAHF) report (2019) identifies opportunities for efficient implementation of housing tax credits, stressing the importance of aligning these initiatives with local development strategies, including spatial plans, zoning regulations, and infrastructure provisions. Nevertheless, the report also identifies a persistent challenge: current planning instruments, such as Integrated Development Plans (IDPs) and Spatial Development Frameworks (SDFs), frequently operate independently of national housing finance policies (CAHF, 2019).

Although the Spatial Development Framework (SDF) is a critical tool for guiding municipal physical development, coordination between SDFs and other planning instruments remains limited, resulting in fragmented development initiatives. According to du Plessis (2013), insufficient horizontal and vertical alignment has produced spatially misaligned housing developments, often located on the urban periphery. This spatial misalignment increases transport costs and exacerbates social exclusion. The primary cause is inadequate involvement of relevant stakeholders in decision-making processes. Limited community engagement in planning undermines both the legitimacy and effectiveness of the SDF. The Local Government: Municipal Systems Act (MSA) 32 of 2000 requires each municipality to develop an Integrated Development Plan (IDP) as its principal strategic planning instrument, guiding all planning, budgeting, management, and decision-making processes (Local Government: Municipal Systems Act, 2000). Despite this mandate, many municipalities continue to encounter challenges in effectively involving communities through the IDP process.

The WEF (2019) report recommends that local institutions, institutional investors, and the local government provide proactive leadership to engage relevant stakeholders in urban planning. The report also advocates for increased multistakeholder collaboration on development projects, including partnerships with local institutions such as universities (WEF, 2019, 2024). In the United States, Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) projects frequently use location-based scoring criteria that prioritize accessibility to economic opportunities, transportation, and educational institutions. Recent reforms in South Africa’s human settlements sector have emphasized the development of housing projects near economic opportunities. Scholars contend that adopting similar criteria in South Africa could substantially improve compliance with spatial justice (CAHF, 2022). Municipalities play a critical role in integrating community perspectives into local government planning, thereby fostering more inclusive and sustainable urban environments.

6.3 Blended financing funding models: a constructive approach

South Africa faces significant financial constraints that necessitate the government allocating its limited resources among competing priorities. Addressing these challenges necessitates the exploration of alternative funding mechanisms to strengthen fiscal capacity and address institutional deficiencies. Scholars including the OECD (2018), Rust (2011), and UN-Habitat (2020b), have introduced the concept of hybrid finance, which strategically combines public grants, concessional loans, market-rate capital, and community contributions. Hybrid finance can support development interventions that are socially beneficial but may not be financially viable through conventional means. Strengthening the institutional capacities of cities is essential for accessing alternative financing sources for urban improvements. Scholars emphasize the importance of collaboration with the national government, particularly through Treasuries that manage transfer payments and procurement, to ensure compliance with legislation such as the Public Financial Management Act of 1999. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) defines blended finance as the strategic use of development finance to mobilize additional funding for sustainable development in developing countries, particularly by attracting private capital (OECD, 2018, p. 8). The World Bank identifies blended finance as a viable strategy to increase government revenue, particularly in the housing sector, where traditional market mechanisms are often inadequate. These inadequacies may result from limited investment returns, high construction costs, or restricted access to credit for low- and middle-income groups (World Bank, 2022). This situation highlights the urgent need for innovative financial models to attract private investment in housing.

Effective blended financing models integrate public subsidies, private investment, and community contributions to achieve a more comprehensive approach. Public-private-community partnerships (PPCPs) offer a framework for risk distribution and participatory governance (Sathiyah, 2013; Perez, 2015; Falch, 2015; Sanga et al., 2013). Scholars such as Scheba and Turok (2020) and the Centre for Affordable Housing Finance in Africa (CAHF, 2019) assert that addressing the affordable housing crisis in South Africa requires increased investment, which can be facilitated by private sector participation. This collaborative strategy is crucial for addressing urban housing shortages in the Global South, where state resources are often insufficient. Adoption of blended housing finance models enables South Africa to attract private capital while safeguarding the public interest, thereby advancing sustainable urban development.

7 Recommendations

7.1 New directions in housing policy and practice in South Africa

Seminal academic analyses consistently identify South Africa’s housing sector as being at a pivotal juncture, with broad agreement that traditional strategies require replacement by more effective alternatives. Large-scale peripheral projects implemented during the RDP era and BNG have failed to achieve spatial justice, socioeconomic integration, or long-term sustainability. Current BNG and FLISP approaches also face substantial challenges and have not met their stated objectives. Although the BNG approach has yielded some measurable outcomes, the number of housing units constructed has declined sharply, primarily due to financial constraints and inadequate management. South Africa currently faces a housing backlog estimated between 2.2 and 3.3 million households, with annual delivery rates decreasing from over 200,000 units in the 1990s to fewer than 35,000 by 2023 (Ngwenya, 2024; CAHF, 2023; Stats SA, 2023; Harding, 2024). This decline in delivery rates necessitates urgent government intervention to reassess and reform the existing system to meet the affordable housing mandate established in the Constitution. Exploring financial innovations, including tax incentives and blended financing models, is crucial for addressing the persistent housing backlog.

A significant challenge in South African housing delivery is the continued dependence on direct government subsidies, which are fiscally unsustainable as national revenues decline, as noted by the National Treasury (NT). The NT Budget (National Treasury, 2025) projects that approximately 22 percent of total revenue will be allocated to interest payments in 2025/2026, substantially reducing available funding for housing and municipal services, including informal settlement upgrades and public rental stock. This fiscal constraint highlights the necessity for innovative approaches to increase government funding for housing provision. The exclusive reliance on state funding, as mandated by the Bill of Rights, has resulted in persistent deficits due to the substantial financial requirements of housing development. Mvuyana (2023) recommends transitioning from large-scale projects to smaller, more practical initiatives. Large-scale projects require significant capital and frequently encounter delays and cost overruns. In contrast, smaller projects offer a viable alternative by emphasizing incentive-based housing solutions that are more compatible with emerging strategies in South Africa. Additionally, research by the Centre for Affordable Housing Finance in Africa (CAHF, 2019) supports a subsidy model that enables a greater number of smaller projects, thereby engaging more contractors and developers and expanding the impact across the subsidy value chain. A comprehensive strategic revision is required, as current models are not achieving the intended outcomes.

7.2 Tax incentives as a new model to increase government revenue

Tax credits represent a viable strategy for addressing fiscal constraints in South Africa while fulfilling the housing mandate for low-income households. For tax credits to be effective, they must align with municipal inclusionary housing policies. Integrating land-value capture mechanisms can further promote urban integration. Compliance with legislative frameworks established by local governments is essential. Property tax rebates should be offered to real estate developers who contribute to the construction of affordable or mixed-income housing. Municipalities should actively support private developers by providing capacity-building initiatives and raising awareness of the benefits of participating in affordable housing projects (African Leadership Magazine, n.d.). Enhancing the capacity of private developers will facilitate their contributions to societal development and broaden economic participation. South Africa can draw on international experiences, as evidenced by the implementation of Low-Income Housing Tax Credits in other countries, which has demonstrated measurable success.

The use of LIHTC is mostly used in the United States. According to Schwartz (2015), the tax credits provide incentives for private developers to build and manage affordable housing by offsetting tax liabilities in exchange for delivering housing that meets specific affordability and location criteria. The LIHTC in the US has successfully attracted billions of dollars in private capital for affordable housing through predictable, multi-year tax incentives. Furthermore, Tomlinson (2015) suggests that tax credits must be linked with zoning laws, land-use plans, and municipal SDFs, ensuring location efficiency and urban integration. Whilst it is the aim to ensure financial sustainability to ensure full participation, it should be noted that systems should be integrated and coordinated, which would assist in meeting the intended outcomes while making an impact in poor communities. If adapted to South Africa’s context, tax incentives could encourage developers, mining houses, and logistics firms to co-finance rental stock for low-income and transient populations, particularly near economic hubs. If tax credits are adopted, the implementers should ensure that they are aligned with the rights enshrined in the SA Constitution. Scholars such as Charlton and Meth (2017) argue that SA can learn from the experiences of other countries by ensuring that any housing tax credit model is anchored in its constitutional mandate of the progressive realization of housing rights.

7.3 Public-private-community partnerships (PPCPs) as collaborators in inclusive housing development

A collaborative approach that accurately addresses community needs is critical for the success of housing projects. This approach involves community engagement from project conceptualization to final handover. Maila et al. (2024) identify public-private partnerships as an effective strategy for governments to co-design and co-implement housing projects with civil society and local communities. Turner (1976) argues that participatory methods can improve residents’ quality of life and reinforce connections among the state, private sector, civil society organizations, and communities. Public-Private-Community Partnerships (PPCPs) represent a promising framework in this context. PPCPs, as defined by Perez (2015, p. 78), represent “a cooperative governance model that integrates the roles and resources of the public sector, private investors, and local communities in the co-production of services or infrastructure, aiming to enhance transparency, social equity, and developmental sustainability.” As Sathiyah (2013) points out (Shoniswa et al., 2024), this partnership model is particularly important in affordable housing contexts, where striking a balance between economic viability and the specific needs of communities is crucial. By incorporating community participation into planning and implementation, PPCPs ensure that housing projects are responsive to local contexts and social dynamics (Shoniswa et al., 2024). Embracing this model supports community involvement in decision-making, aligning with the principles outlined in the Systems Act.

Facilitating these collaborations can address housing shortages and prioritize local needs in affordable housing developments. Such partnerships represent a shift toward participatory urbanism, particularly in contexts involving informal settlement upgrades, inner-city revitalization, and enhanced tenure security. Although the government has encouraged increased private sector participation in housing development, a structured framework that guides all stakeholders remains necessary (Shoniswa et al., 2024). Public-private collaborations enable governments to respond to increasing demands for housing and infrastructure, even under budgetary limitations. Achieving this vision requires transparent and meaningful engagement among partners, leveraging the expertise of both the public and private sectors to deliver high-quality projects that align with national strategic goals (Ramolobe et al., 2024). The WEF (2019) underscores the importance of collective cooperation, whether it involves the state providing land for redevelopment or private entities financing and constructing projects. These alliances can foster sustainable economic growth through job creation and enhance overall trust in government and accountability within housing systems. By adopting public-private partnerships as a strategy, governments can work closely with civil society and local communities to create impactful housing solutions (Maila et al., 2024).

8 Limitations and future research

This study primarily relied on secondary data, which facilitated the synthesis of existing debates and the identification of research gaps. However, secondary data may reflect the biases or agendas of original sources. The lack of primary data limited the documentation of the lived experiences of communities most affected by inadequate housing. Methodological choices may have reinforced dominant discourses and underrepresented marginalized perspectives. The South African Affordable Housing Tax Credit (SA-AHTC) model has yet to be empirically tested. While the conceptual framework shows potential, its feasibility, fiscal sustainability, and social impact have not been evaluated in practical settings. Barriers to innovation, including political resistance, bureaucratic disinterest, and entrenched subsidy frameworks, present significant risks to policy adoption. Future research should examine the political and institutional dynamics that influence housing policy, ensuring that proposed financing mechanisms are both economically viable and politically feasible. Addressing this research gap may require piloting the SA-AHTC model, engaging stakeholders from government and industry, and applying relevant modeling to simulate potential outcomes.

9 Conclusion

South Africa’s housing sector faces deep-rooted structural obstacles—encompassing an enduring housing deficit, geographic disparities, and constrained budgetary resources—that have exceeded the capabilities of conventional subsidy-based programs like the RDP, BNG, and FLISP. Although these programs have broadened housing accessibility, they remain insufficient in addressing escalating needs, especially among middle-income earners who fall outside the eligibility criteria for both government-subsidized housing and commercial mortgage products. When properly coordinated, this approach could alleviate fiscal pressures on government, enhance spatial equity, and expand the supply of reasonably priced rental accommodations in proximity to employment centers.

Overall, this research advances policy discussions by proposing an adaptable, inclusivity-focused housing finance mechanism. Through incorporating tax credits into South Africa’s dynamic urban planning and governance framework, the country can transcend historical exclusionary practices and establish a more equitable, effective, and resilient housing system. Subsequent studies should investigate pilot programs, conduct predictive modeling, and engage diverse stakeholders to enhance and implement the SA-AHTC model more comprehensively.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

BM: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GM: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

African Leadership Magazine . (n.d.). How affordable housing projects can solve Africa's urban crisis. Available online at: https://www.africanleadershipmagazine.co.uk/how-affordable-housing-projects-can-solve-africas-urban-crisis/ (Accessed June 14, 2025).

2

African National Congress (1994). The reconstruction and development programme. Johannesburg: ANC.

3

Behrens R. Wilkinson P. (2003). “Housing and the passenger transport policy and planning in south African cities: a problematic relationship” in Confronting fragmentation: Housing and urban development in a democratizing society. eds. HarrisonP.HuchzermeyerM.MayekisoM. (Cape Town: University of Cape Town Press).

4

Bødker K. Kensing F. Simonsen J. (2004). Participatory IT design: Designing for business and workplace realities. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

5

CAHF (2019). Economic impact of housing subsidies. Johannesburg: Centre for Affordable Housing Finance in Africa.

6

CAHF (2022). Housing finance in Africa: Yearbook 2022. Johannesburg: Centre for Affordable Housing Finance in Africa.

7

CAHF (2023). Annual housing finance yearbook: South Africa country profile. Johannesburg: Centre for Affordable Housing Finance in Africa.

8

Charlton S. (2003). “The integrated delivery of housing: a local government perspective from Durban” in Confronting fragmentation: Housing and urban development in a democratizing society. eds. HarrisonP.HuchzermeyerM.MayekisoM. (Cape Town: University of Cape Town Press).

9

Charlton S. Kihato C. (2006). Reaching the poor? An analysis of the influences on the evolution of South Africa’s housing programme. In PillayU.TomlinsonR.ToitJ.du (Eds.), Democracy and delivery: Urban policy in South Africa (pp. 252–282). Soth Arfica: HSRC Press.

10

Charlton S. Meth P. J. (2017). Lived experiences of state housing in Johannesburg and Durban. Transformation. 93, 91–115. doi: 10.1353/trn.2017.0004

11

City of Ekurhuleni (2021). Breaking new ground (BNG) housing is aimed to eradicate informal settlements. Pretoria: Government Printers.

12

City of Johannesburg (CoJ) (2019). Inclusionary housing policy: Implementation plan. South Africa: Johannesburg.

13

Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights . (1991). General comment no. 4: the right to adequate housing. UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

14

Creswell J. W. Plano Clark V. L. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 3rd Edn. London: SAGE Publications.

15

Daily Maverick . (2022). Housing: Time to replace the outdated one-plot-one-house model. Available online at: https://www.dailymaverick.co.za (Accessed June 20, 2025)

16

Department of Housing (2004). Breaking new ground: A comprehensive plan for the development of sustainable human settlements. Government Printers: Pretoria.

17

Department of Human Settlements (2005). Finance linked individual subsidy programme (FLISP) policy guidelines. Pretoria: Government Printers.

18

Department of Human Settlements (2023a). Annual performance plan 2023/2024. Government Printers: Pretoria.

19

Department of Human Settlements (2023b). Annual Report 2023/2024. Government Printers: Pretoria.

20

Department of Human Settlements (2023c). White paper on human settlements. Government Printers: Pretoria.

21

Desmond M. (2016). Evicted: Poverty and profit in the American city. New York: Crown Publishing.

22

Du Plessis D. (2013). A critical reflection on urban spatial planning practices and outcomes in post-apartheid South Africa. Urban Forum25, 69–88. doi: 10.1007/s12132-013-9201-5

23

Ellen I. G. Horn K. M. (2018). Points for place: can state LIHTC allocation policies increase access to opportunity neighborhoods?Hous. Policy Debate28, 727–745. doi: 10.1080/10511482.2018.1443487

24

eThekwini Municipality . (2016). Informal settlements upgrading strategy. Available online at: www.durban.gov.za (Accessed June 20, 2025).

25

Falch M. (2015). PPP as a Tool for Stimulating Investment in ICT Infrastructures, Encyclopaedia of Information Science and Technology, Third Edition. Available online at: https://www.igiglob-al.com (Accessed July 20, 2025).

26

Farha L. (2016). The human right to housing. UN Special Rapporteur on Adequate Housing

27

Freeman L. (2020). The challenge of preserving low-income housing in neighborhoods with rising rents. Urban Aff. Rev.56, 524–554.

28

Global Property Guide . (2024). South Africa's residential property market analysis 2024. Available online at: https://www.globalpropertyguide.com/ (Accessed June 17, 2025)

29

Harding A. (2024). ‘People have died on the waiting lists': South Africa's housing crisis casts a shadow over election. The Guardian. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/ (Accessed June 15, 2025)

30

Hohmann J. (2013). The right to housing: Law, concepts, possibilities. Oxford: Hart Publishing.

31

Housing Development Agency . (2023). National Housing Needs Assessment. Available online at: http://www.thehda.co.za (Accessed June 20, 2025).

32

Huchzermeyer M. (2003). Housing rights in South Africa: invasions, evictions, the media, and the courts in the cases of Grootboom, Alexandra, and Bredell. Urban Forum14, 80–107. doi: 10.1007/s12132-003-0004-y

33

Huchzermeyer M. (2009). The struggle for in situ upgrading of informal settlements: a reflection on cases in Gauteng. Dev. South. Afr.26, 59–73. doi: 10.1080/03768350802640099

34

Huchzermeyer M. (2011). Cities with ‘slums’: From informal settlement eradication to a right to the City in Africa. Cape Town: UCT Press.

35

HUD (2011). Available online at: https://www.huduser.org

36

Kamana A. A. Radoine H. Nyasulu C. (2024). Urban challenges and strategies in African cities – a systematic literature review. City Environ. Interact.21. doi: 10.1016/j.cacint.2023.100132

37

Kaushik V. Walsh C. A. (2019). Pragmatism as a research paradigm and its implications for social work research. Soc. Sci.8:255. doi: 10.3390/socsci8090255

38

Lens M. C. Reina V. J. (2016). Preserving neighborhood opportunity: where federal housing subsidies expire. Hous. Policy Debate26, 714–732. doi: 10.1080/10511482.2016.1195422

39

Local Government: Municipal Systems Act . (2000). LG: Municipal Systems Act. Government Printers. Pretoria. Available online at: https://www.gov.za

40

Mabin A. A. (2020). Century of South African Housing Acts 1920–2020. Urban Forum.31, 453–472. doi: 10.1007/s12132-020-09411-7

41

Maila H. (2024). South Africa's low-cost housing model is broken – study suggests how to fix it. The Conversation. Available online at: https://theconversation.com/south-africas-low-cost-housing-model-is-broken-study-suggests-how-to-fix-it-244876 14 January 2025.

42

Maila H. Malan L. Mazenda A. (2024). A co-production model for the south African housing sector. Afr. Public Serv. Deliv. Perform. Rev.12, 1–12. doi: 10.4102/apsdpr.v12i1.800

43

Marutlulle N. K. (2021). A critical analysis of housing inadequacy in South Africa and its ramifications. Afr. Public Serv. Deliv. Perform. Rev.9. doi: 10.4102/apsdpr.v9i1.372

44

Marutlulle N. (2022). Critical analysis of the role played by apartheid in the present housing delivery challenges encountered in South Africa. Afr. Public Serv. Deliv. Perform. Rev.10, 1–12. doi: 10.4102/apsdpr.v10i1.373

45

Mchunu K. Nkambule S. (2019). An evaluation of access to adequate housing: A case study of eZamokuhle township, Mpumalanga; South Africa, Cogent Social Sciences, 5:1653618. doi: 10.1080/23311886.2019.1653618

46

Mhlongo N. Z. D. Gumbo T. Musonda I. (2022). Inefficiencies in the delivery of low-income housing in South Africa: is governance the missing link? A review of literature. IOP Conf. Series Earth Environ. Sci.1101:052004. doi: 10.1088/1755-1315/1101/5/052004

47

Mvuyana B. Y. C. (2023). Theory of Change as a monitoring and evaluation tool aimed at achieving sustainable human settlements. Africa’s Public Service Delivery & Performance Review. 11:a659. doi: 10.4102/apsdpr.v11i1.659

48

Mvuyana B. Y. C. (2025). The role of social actors in building sustainable cities in the Global South. Frontiers Sustainable. Cities7:1536656. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2025.1536656

49

National Housing Finance Corporation (2020). FLISP Programme Guide

50

National Treasury (2021a). Budget review: Human settlements and urban development Grants. Pretoria: Government Printers.

51

National Treasury (2021b). Division of revenue bill: Urban settlements development Grant and ISUPG overview. Pretoria: Government Printers.

52

National Treasury (2025). 2025 budget overview. South African National Treasury. Pretoria: Government Printers.

53

Ngwenya T. (2024). South Africa’s housing delivery has slowed: how the backlog can be tackled. The Conversation. Available online at: https://theconversation.com/south-africas-low-cost-housing-model-is-broken-study-suggests-how-to-fix-it-244876 (Accessed June 15, 2025).

54

O’Regan K. M. Horn K. M. (2013). What can we learn about the low-income housing tax credit program by looking at the tenants?Hous. Policy Debate23, 597–613. doi: 10.1080/10511482.2013.772909

55

OECD (2018). Making blended finance work for the sustainable development goals. Paris: OECD Publishing.

56

Page M. J. McKenzie J. E. Bossuyt P. M. Boutron I. Hoffmann T. C. Mulrow C. D. et al . (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

57

Parnell S. Pieterse E. (2010). The ‘right to the City’: institutional imperatives of a developmental state. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res.34, 146–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2427.2010.00954.x

58

Patel S. Mitlin D. (2010). “Reinterpreting the rights-based approach: a grassroots perspective on rights and development” in Routledge handbook of human rights. eds. MihrT.GibneyM. (London: Routledge), 423–437.

59

Perez M. C. (2015). Public-Private-Community Partnerships for Renewable Ener-gy Cooperatives. Wageningen: Wageningen University, Environmental Policy Group. Available online at: https://edepot.wur.nl/337095

60

Ramolobe K. S. Khandanisa U. (2024). ‘The role of public–private partnership in achieving local government sustainable development’. Africa’s Public Service Delivery and Performance Review.12:a816.

61

Rolnik R. (2019). Urban warfare: Housing under the empire of finance. London: Verso Books.

62

Roy A. (2005). Urban informality: toward an epistemology of planning. J. Am. Plan. Assoc.71, 147–158. doi: 10.1080/01944360508976689

63

Rust K. (2011). Improving access to the affordable housing market in South Africa. Johannesburg: Centre for Affordable Housing Finance in Africa.

64

Sanga C. Tumbo S. Mlozi M. Kilima F. (2013). Community engagement in public-private-community partnerships. J. Public Admin. Dev. Altern. 85–104.

65

Sathiyah S. (2013). History, Identity, Representation: Public-Private-Community Partnerships and the Batlokoa Community, University of KwaZulu Natal, Durban. Available online at: http://hdl.handle.net/10413/11319

66

Scally C. P. Gold A. DuBois N. (2018). The low-income housing tax credit: how it works and who it serves. Urban Institute Report. Available online at: https://www.urban.org/research/publication/low-income-housing-tax-credit-how-it-works-and-who-it-serves (Accessed July 9, 2025).

67

Scheba A. Turok I. (2020). Informal rental housing in the south: dynamic but neglected. Environ. Urban.32, 109–132. doi: 10.1177/0956247819895958

68

Scheba A. Turok I. (2021). Spatial drift: the location of subsidised housing in south African cities. AFD research report. (Details available via Agence Française de Développement interne reports, 2021).

69

Schwartz A. F. (2015). Housing policy in the United States. 3rd Edn. New York: Routledge.

70

Shisaka Development Management Services . (2020). Assessing the effectiveness of housing subsidies in South Africa.

71

Shoniswa B. Zhou G. Zinyama T. (2024). The Paradigm Shift from Public Private Partnership to Public Private Partnerships: A Etical & Experiential Exposition. Journal of Public Administration and Administrative Alternatives.9, 1–14. doi: 10.55190/JPADA.2024.312

72

Smit W. (2006). Understanding the complexities of informal settlements: Insights from Cape Town. In: Huchzermeyer, M. & Karam, A. (Eds). Confronting fragmentation: A perpetual challenge? Cape Town: UCT Press, 103–125.

73

Socio-Economic Rights Institute of South Africa . (2018). Informal settlement upgrading in South Africa: policies, practices and prospects.

74

South African Institute of Race Relations . (2021). Urbanisation and its challenges in South Africa.

75

Stats SA (2022). Mid-year population estimates 2022. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa.

76

Stats SA (2023). General household survey 2022. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa.

77

The Republic of South Africa . (1996). South African Constitution. Government Printers. Pretoria. Available online at: https://www.gov.za

78

Tissington K. (2011). A resource guide to housing in South Africa 1994–2010: legislation, policy, Programmes and practice. Socio-Economic Rights Institute of South Africa (SERI).

79

Tobias P. Edward J. P. (2025). America’s six million home shortage: why California is at the epicenter. The American Enterprise Institute (AEI) housing center. 2 July 2025.

80

Tomlinson M. (2015). South Africa’s housing conundrum. Liberty: The Policy Bulletin of the Institute of Race Relations. 20, 1–7.

81

Turner J. F. C. (1976). Housing by people: Towards autonomy in building environments. New York, USA: Marion Boyars.

82

Turok I. Borel-Saladin J. (2016). Backyard shacks, informality and the urban housing crisis in South Africa. Urban Forum27, 25–40. doi: 10.1080/02673037.2015.1091921

83

UN-Habitat (2014). The right to adequate housing. Nairobi: UN-Habitat.

84

UN-Habitat (2020a). Housing policy and finance in the global south: Best practices and emerging innovations. Nairobi: UN-Habitat.

85

UN-Habitat (2020b). World cities report: The value of sustainable urbanization. UN-Habitat: Nairobi.

86

United Nations (1948). Universal declaration of human rights (UDHR). UN-Habitat: Nairobi.

87

United Nations General Assembly . (1996). UN General Assembly Resolutions. New York. USA. (Accessed October 23, 2025).

88

United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (2011). What happens to low-income housing tax credit properties at year 15 and beyond?Washington, DC: Office of Policy Development and Research. Retrieved from.

89

United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (2021). Low-income housing tax credits. Washington, DC: HUD.

90

United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (2022). Low-income housing tax credits (LIHTC) database. Washington, DC: HUD. Available online at: https://lihtc.huduser.gov (Accessed 15 July 2025).

91

Van Donk M. Pieterse E. (2006). “Reflections on the design of a post-apartheid system of (urban) local government” in Developmental local government: Case studies in South Africa. eds. ParnellS.PieterseE.SwillingM.WooldridgeD. (Cape Town: UCT Press).

92

WEF . (2019). Innovative urban financing can make our cities stronger. Urban Transformation. 3 July 2025

93

WEF (2024). Improving social outcomes in urban development: a playbook for practitioners WHITE PAPER. World Economic Forum. 3 July 2025

94

WEF . (2022). In collaboration with PwC; Rethinking City revenue and finance INSIGHT REPORT. World Economic Forum. 3 July 2025

95

World Bank (2022). Innovative financing solutions for housing in Africa. Washington, DC: World Bank.

96

Youth Village . (n.d.) Are RDP houses still prevalent today? Available online at: www.youthvillage.org (Accessed June 20, 2025).

Summary

Keywords

affordable housing, low-income housing tax credits, public-private partnerships, urban inequality, urbanization

Citation

Mvuyana BYC and Matthews G (2025) Tax credit mechanisms and policy innovation for affordable housing in South Africa: a systematic review. Front. Sustain. Cities 7:1665969. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2025.1665969

Received

14 July 2025

Accepted

30 September 2025

Published

13 November 2025

Volume

7 - 2025

Edited by

Khululekani Ntakana, University of Johannesburg, South Africa

Reviewed by

Emmanuel Kabundu, Nelson Mandela University, South Africa

Gerrit Crafford, Nelson Mandela University, South Africa

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Mvuyana and Matthews.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bongekile Yvonne Charlotte Mvuyana, mvuyana@mut.ac.za

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.