Abstract

This study addresses the underexplored area of cruise tourism competitiveness in emerging Asian cities, focusing on port-city mobility and governance in Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC), Vietnam. Using qualitative analysis of 20 semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders, including tour operators, port authorities, and government officials, the research identifies a systemic framework of eight interdependent dimensions critical to HCMC's competitiveness: accessibility, shore excursion logistics, service quality, tourist spending behavior, cultural-commercial integration, institutional coordination, destination image, and regional integration. Findings reveal that despite HCMC's strategic location and rich cultural assets, disjointed transportation infrastructure—characterized by inefficient diesel-dependent port transfers, limited EV adoption, and poor last-mile connectivity—undermines sustainable development and visitor experiences. To address these gaps, the study proposes an integrated management framework that emphasizes mobility innovation, enhanced stakeholder collaboration, and curated cultural offerings near ports. By bridging infrastructure, governance, and cultural resource gaps, this research contributes to destination competitiveness theory for emerging Asian cruise markets and supports sustainable urban transitions by advancing SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) through inclusive mobility planning and SDG 13 (Climate Action) by promoting low-carbon port-city transport solutions.

1 Introduction

Cruise tourism has emerged as one of the fastest-growing segments in global travel, offering a unique combination of mobility, luxury, and exploratory experiences (Papathanassis and Beckmann, 2011; Viña and Ford, 2001). According to the Cruise Lines International Association (CLIA, 2023), global cruise passenger numbers surpassed 30 million in 2023, marking a strong recovery following the disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. As the industry continues to expand, Southeast Asia is gaining prominence, driven by increasing intra-regional demand and substantial investments in modern port infrastructure across countries such as Singapore, Malaysia, and Thailand (Rodrigue and Notteboom, 2013; Lau et al., 2022).

In Vietnam, Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC) is strategically positioned at the crossroads of major regional cruise routes. The city's dynamic urban environment and rich cultural heritage provide a strong foundation for developing a competitive cruise tourism destination. Despite these advantages, HCMC continues to face several persistent challenges, including underdeveloped port infrastructure, a lack of cruise-specific tourism products, weak inter-agency coordination, and fragmented port-city transportation systems that we analyze through stakeholder perspectives on transport emissions and governance (Dwyer et al., 2009). Moreover, with intensifying competition from established cruise hubs such as Singapore's Marina Bay Cruise Centre, Malaysia's Port Klang, and Thailand's Laem Chabang, it is imperative to evaluate and enhance the city's competitiveness.

Destination competitiveness remains a central focus in tourism research. Foundational models by Crouch and Ritchie (1999) and Dwyer and Kim (2003) underscore its multi-dimensional nature, encompassing core resources, supporting infrastructure, and collaborative stakeholder engagement. While these frameworks have been widely applied to various tourism settings—such as Mediterranean beach destinations (Papatheodorou, 2002) and Canadian resorts (Hudson et al., 2004)—their application within the context of cruise tourism, particularly in emerging Asian cities, remains underexplored (Wondirad, 2019; Lau et al., 2022). Critically, existing studies often adopt a static, resource-centric view, neglecting the systemic interdependencies between infrastructure, cultural assets, and governance that define competitiveness in short-stay cruise contexts. Furthermore, the predominance of Western-centric models fails to account for the unique institutional and logistical challenges faced by Southeast Asian cities like HCMC, where rapid urbanization, fragmented governance structures, and different public-private partnership models complicate destination development.

Additionally, much of the existing research on cruise tourism relies on quantitative methods, often focusing on metrics like tourist satisfaction or operational performance indicators (Papathanassis, 2017; Hritz and Cecil, 2008). While such approaches provide valuable broad benchmarks, they can be less effective at capturing the nuanced stakeholder dynamics such as conflicts between port authorities and local businesses or gaps in policy implementation that shape competitiveness in practice. However, cruise tourism development is shaped by a complex web of interdependencies involving public policy, private investment, governance mechanisms, and cultural contexts—dimensions that are more suitably examined through qualitative approaches (Hall, 2008). This study addresses these gaps by employing a stakeholder-informed qualitative methodology to uncover the institutional logics, power asymmetries, and cultural resource valuations that quantitative surveys cannot capture. By doing so, it advances a more holistic understanding of competitiveness that integrates structural barriers (e.g., port-city connectivity) with experiential factors (e.g., cultural authenticity)—a perspective absent in prior cruise tourism literature. Findings also contribute to sustainable development debates by aligning with SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), through more inclusive and integrated urban mobility planning, and SDG 13 (Climate Action), by emphasizing low-emission port-city transport strategies.

Understanding how key stakeholders perceive and influence destination development is, therefore, essential to capturing the strategic and structural elements of competitiveness (Buhalis, 2000; Go and Govers, 2000). This study aims to address this gap by conducting a qualitative investigation into the competitiveness of Ho Chi Minh City as a cruise tourism destination. Drawing on insights from tour operators, port authorities, service providers, and public agencies, the research seeks to identify the core drivers of competitiveness and offer policy-relevant recommendations for sustainable destination development.

2 Literature review

2.1 Theoretical perspectives on destination competitiveness in tourism

Destination competitiveness has long been a central theme in tourism research, seeking to understand why certain locations are more successful in attracting and sustaining tourist flows. Seminal models developed by Ritchie and Crouch (2003) and Dwyer and Kim (2003) conceptualize competitiveness not only in terms of destination appeal but also through broader dimensions of economic, social, and environmental sustainability.

Ritchie and Crouch's framework distinguishes between inherited resources—such as natural landscapes, cultural heritage, and climate—and supporting elements, including infrastructure, accessibility, and the quality of institutions. Dwyer and Kim expand on this by incorporating additional components such as demand conditions and destination management capabilities. These comprehensive models have been widely applied in various tourism contexts (Hudson et al., 2004; Kozak, 2003).

The Resource-Based View (RBV) offers a complementary perspective by emphasizing the importance of resources that are valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable as drivers of sustained competitive advantage (Barney, 1991; Cucculelli and Goffi, 2016). Within the tourism sector, RBV highlights the strategic role of innovation, institutional coordination, and destination-specific assets (Novais et al., 2018).

2.2 Critical Gaps in cruise tourism competitiveness research

The third major limitation concerns the static conceptualization of what are inherently dynamic systems. Most existing approaches treat key dimensions of competitiveness as fixed and universal indicators, failing to account for the unique temporal and logistical challenges faced by cruise tourism destinations. For instance, issues such as port-city transfers, time-constrained excursions, and seasonal fluctuations in passenger volume demand greater operational flexibility than is currently reflected in the literature (Papathanassis, 2017). Crucially, emissions from port transfers (e.g., diesel buses) remain unquantified in cruise tourism research—a gap this study addresses through stakeholder-reported data that reveals their environmental impact and economic costs. These factors underscore the importance of mobility systems as core elements of cruise destination management.

Fragmented transport infrastructure between ports and city centers creates what scholars' term “transport poverty,” where accessibility gaps disproportionately affect both local service providers and short-stay cruise tourists (Lucas, 2012). This mobility inequality results in inefficient transfers, congestion, and missed economic opportunities for local businesses. At the port-city interface, the lack of multimodal transport integration and last-mile connectivity severely constrains the tourist experience (Rodrigue and Notteboom, 2013), further weakening the city's appeal in regional cruise networks. Notably, tourist frustration with inefficient transfers aligns with emerging gamification applications for mobility behavior change, suggesting potential for digital nudges to optimize transport choices during short-stay visits.

Therefore, to address these gaps, the city should adopt a more holistic and context-sensitive approach. This approach integrates cultural assets with commercial opportunities by promoting themed heritage tours and collaborations with local artisans to enrich cruise experiences and generate local value. It also positions mobility systems and institutional agility as core components, recognizing the need for dynamic governance, interdependent infrastructure, and flexible policies in emerging market contexts (Soedarsono et al., 2020). Furthermore, it underscores the interconnectedness of infrastructure, mobility access, cultural resources, and stakeholder coordination—particularly important in short-stay cruise settings—thus presenting a more adaptable and integrated model for enhancing destination competitiveness in the rapidly evolving cruise tourism landscape.

2.3 Cruise tourism as a distinctive segment

Cruise tourism represents a distinct sub-sector within the broader tourism industry, combining transportation, accommodation, and entertainment within a mobile setting. Unlike land-based tourism, cruise itineraries follow predetermined schedules, with destinations serving as temporary stopovers rather than end points (Rodrigue and Notteboom, 2013). This structure imposes unique demands on logistics, visitor engagement, and destination planning.

Competitiveness in cruise tourism hinges on several key factors, including port accessibility, passenger turnaround efficiency, safety standards, and proximity to attractive sites (Brida and Zapata, 2010). Cruise lines assess potential ports based on criteria such as port fees, ease of navigation, berthing capacity, and the quality of logistical support. Given the typically short duration of port calls—often limited to 4–8 h—destinations are under pressure to deliver high-quality, time-efficient shore excursions (Sanz-Blas et al., 2019).

In Southeast Asia, ports such as Singapore, Laem Chabang (Thailand), and Port Klang (Malaysia) have established themselves as regional cruise hubs, benefitting from advanced infrastructure, efficient operational systems, and a wide variety of attractions (CLIA, 2023). Vietnam, despite its advantageous geographic position and rich cultural heritage, has yet to capitalize fully on its cruise tourism potential. Persistent challenges include inadequate port infrastructure, weak integration of services, limited development of cruise-specific products, and fragmented governance structures (Vlăsceanu and Ţigu, 2020; Lau et al., 2022).

Cruise travelers also differ notably from traditional tourists. They tend to be less price-sensitive, value convenience, and seek personalized, high-impact experiences within short timeframes (Hung et al., 2019). This necessitates not only sufficient infrastructure but also a coordinated and specialized service ecosystem capable of meeting cruise passengers' expectations.

2.4 Determinants of cruise destination competitiveness

The competitiveness of cruise destinations is shaped by the dynamic interplay between internal capacities and external environmental conditions. Building on foundational models by Crouch and Ritchie (1999) and Dwyer and Kim (2003), we identify eight critical dimensions:

-

Accessibility: Includes geographic location, connectivity to major routes, and transport information (Enright and Newton, 2005)

-

Service Quality: Professionalism, communication, and amenity availability (Buhalis, 2000; Parasuraman et al., 1988)

-

Cost/Value: Port fees, excursion pricing, and overall experience value (Forsyth et al., 2014; Hung and Petrick, 2011)

-

Destination Attractiveness: Natural and cultural assets (Crouch and Ritchie, 1999; Mohamad et al., 2022)

-

Stakeholder Collaboration: Coordination among government, businesses and communities (Madsen et al., 2008; Byrd, 2007)

-

Environmental Sustainability: Ecological footprint management (Reisinger et al., 2019; Carić, 2016)

-

Cultural-Commercial Integration (novel dimension): Strategic pairing of heritage assets with retail/entertainment

-

Institutional Agility (novel dimension): Adaptive policy responses to market changes

Theoretical advancement is a central contribution of our proposed framework, which extends traditional models by addressing key contextual gaps and conceptual limitations. One of the primary innovations lies in the inclusion of two additional dimensions—dimensions seven and eight—that are specifically tailored to the realities of emerging Asian cruise ports. These new elements reflect the unique socio-economic, cultural, and governance conditions found in developing cruise destinations, which are often overlooked in existing frameworks predominantly designed for mature, Western markets.

Furthermore, our framework shifts away from viewing competitiveness dimensions as isolated or linearly connected components. Instead, it emphasizes the dynamic interactions among these dimensions, recognizing that factors such as infrastructure development, cultural resource utilization, and institutional support are interdependent and constantly evolving in response to market conditions, policy changes, and visitor preferences. This systems-oriented perspective allows for a more nuanced understanding of how destination competitiveness is shaped and reshaped over time.

In addition, the framework incorporates an analysis of stakeholder power dynamics, an aspect that is frequently underrepresented in conventional, Western-centric tourism models. In many emerging cruise destinations, the distribution of influence among government agencies, private operators, community groups, and international cruise lines plays a critical role in shaping development outcomes. By integrating these power relations into the framework, we provide a more realistic and actionable tool for understanding how competing interests and institutional fragmentation affect cruise tourism competitiveness in the Global South.

As Gomezelj and Mihalič (2008) argue, competitiveness is inherently context-specific. For emerging cruise destinations like Ho Chi Minh City, this framework provides a more appropriate tool for analyzing and enhancing competitiveness by accounting for local institutional realities and cultural resources (Pham and Le, 2024).

3 Research method

3.1 Methodological approach

This study is grounded in a constructionist epistemology, which asserts that knowledge is shaped through individual experiences and social interactions within specific contexts (Hesse-Biber and Leavy, 2010). Given the multifaceted nature of cruise tourism—encompassing operational logistics, governance structures, and transportation systems—a qualitative methodology was deemed most appropriate. This approach captures critical mobility-specific data that quantitative metrics often obscure, as stakeholder insights reveal hidden inefficiencies in transport systems that big data overlooks (e.g., sign language gaps, wayfinding confusion, and cultural barriers to EV adoption).

In particular, the study frames stakeholder interviews as a method for assessing the user experience of urban mobility systems at the port-city interface, alongside broader institutional and tourism dynamics. Interview protocols explicitly probed three under-researched mobility dimensions: (1) last-mile connectivity challenges, (2) EV adoption barriers in shuttle fleets, and (3) real-time navigation needs for time-constrained tourists. This granular focus responds directly to gaps in smart mobility literature, which often prioritizes system-wide efficiency over experiential friction points.

This approach is uniquely positioned to uncover the infrastructural disconnects and institutional barriers often masked by aggregate quantitative metrics, thereby advancing theoretical understanding of cruise tourism competitiveness as a multi-scalar and multi-stakeholder phenomenon. By prioritizing in-depth insights over generalized indicators, the study responds to gaps in the literature related to power asymmetries, transport access inequalities (i.e., “transport poverty”), and fragmented mobility governance—critical issues for sustainable cruise development in cities like HCMC.

As Creswell (2012) notes, social research is inherently influenced by the researcher's underlying worldview regarding the nature of reality and knowledge. In the context of Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC), an emerging cruise tourism hub in Southeast Asia, a qualitative approach allows for a nuanced, flexible, and contextually grounded exploration of destination competitiveness and urban mobility integration.

To guide this inquiry, the study was structured around the following Research Questions (RQs):

-

RQ1: What are the key dimensions determining the cruise tourism competitiveness of Ho Chi Minh City from a stakeholder perspective?

-

RQ2: How do challenges in port-city mobility and stakeholder governance impact these competitiveness dimensions?

-

RQ3: What strategies can be proposed to enhance HCMC's sustainable competitiveness as a cruise destination?

Data were collected between February 15 and April 30, 2025, through semi-structured, in-depth interviews with a range of stakeholders, including travel agencies, cruise service providers, port authorities, and municipal officials. The interviews explored the systemic and experiential aspects of HCMC's mobility environment—such as last-mile connectivity, port-to-city transfers, and the perceived usability of transport options by tourists. To enrich contextual understanding, field observations were also conducted at key sites such as Phu My Port, Saigon Port, cruise terminals, and major tourist attractions in HCMC. The collected data were analyzed thematically to uncover recurring patterns and identify critical factors shaping cruise tourism competitiveness and mobility system performance.

3.2 Sampling and data collection

Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC) hosts 188 heritage sites and welcomed 150,000 cruise passengers in 2024 (So du lich TP.HCM, 2024). Despite its strategic location, challenges like fragmented port connectivity and weak stakeholder coordination persist—precisely the institutional complexities this study's qualitative design is optimized to unpack.

Given the exploratory nature and context-specific focus of this study, purposive sampling was employed to recruit participants with specialized expertise and direct involvement in cruise tourism development in Ho Chi Minh City (Creswell, 2012). The research engaged 20 key informants representing diverse stakeholder groups, including four government officials responsible for tourism policy, three cruise line representatives involved in itinerary planning, seven inbound tour operators with cruise tourism experience, four port service providers, and two academics specializing in tourism studies (see Table 1). Semi-structured interviews were conducted between February 15 and April 30, 2025, utilizing a flexible interview guide that combined prepared open-ended questions with adaptive probing to capture emergent themes. These in-depth sessions, lasting 45–90 min each, were conducted in either Vietnamese or English according to participant preference, through both in-person and online formats. All interviews followed strict ethical protocols, including obtaining informed consent, audio recording for accuracy, professional transcription, and complete anonymization of participant identities. The interviews specifically examined three core aspects of HCMC's cruise tourism competitiveness: infrastructure and policy challenges affecting port development, mechanisms for stakeholder coordination across sectors, and the strategic utilization of cultural assets to enhance visitor experiences (see Table 2). To strengthen methodological rigor, these interview data were complemented by non-participant observations at key cruise tourism locations including ports and major attractions, enabling triangulation of findings across different data sources (Veal and Darcy, 2014). This multi-method approach provided both depth of understanding through stakeholder perspectives and contextual grounding through direct observation of operational realities.

Table 1

| Group | Code | Age range | N | % | Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tourism enterprises | DoanhNghiep00 | 28–50 | 16 | 100% | Management/operations/guiding |

| Experts/public sector | ChuyenGia00 | 35–65 | 4 | 100% | Policy/lecture |

Interviewee demographics.

Table 2

| Stakeholder group | Main interview topics |

|---|---|

| Tour operators and travel agencies | • HCMC's accessibility within regional cruise itineraries |

| • Shore excursion logistics | |

| • Service quality and tourist spending | |

| • Institutional collaboration barriers | |

| • Regional port comparisons | |

| Tourism experts and public officials | • Port infrastructure policies |

| • Workforce training programs | |

| • Cultural-commercial product integration | |

| • Public-private partnerships | |

| • Climate adaptation strategies |

Interviewee groups and key themes explored.

3.3 Data analysis

Interview data were analyzed using the Grounded Theory approach (Glaser and Strauss, 2017), following a three-stage coding process:

-

Open Coding: Transcripts were examined line-by-line to identify 78 initial codes (e.g., “port congestion,” “heritage interpretation gaps”).

-

Focused Coding: Codes were grouped into 12 thematic categories (e.g., “infrastructure limitations,” “cultural commercialization challenges”).

-

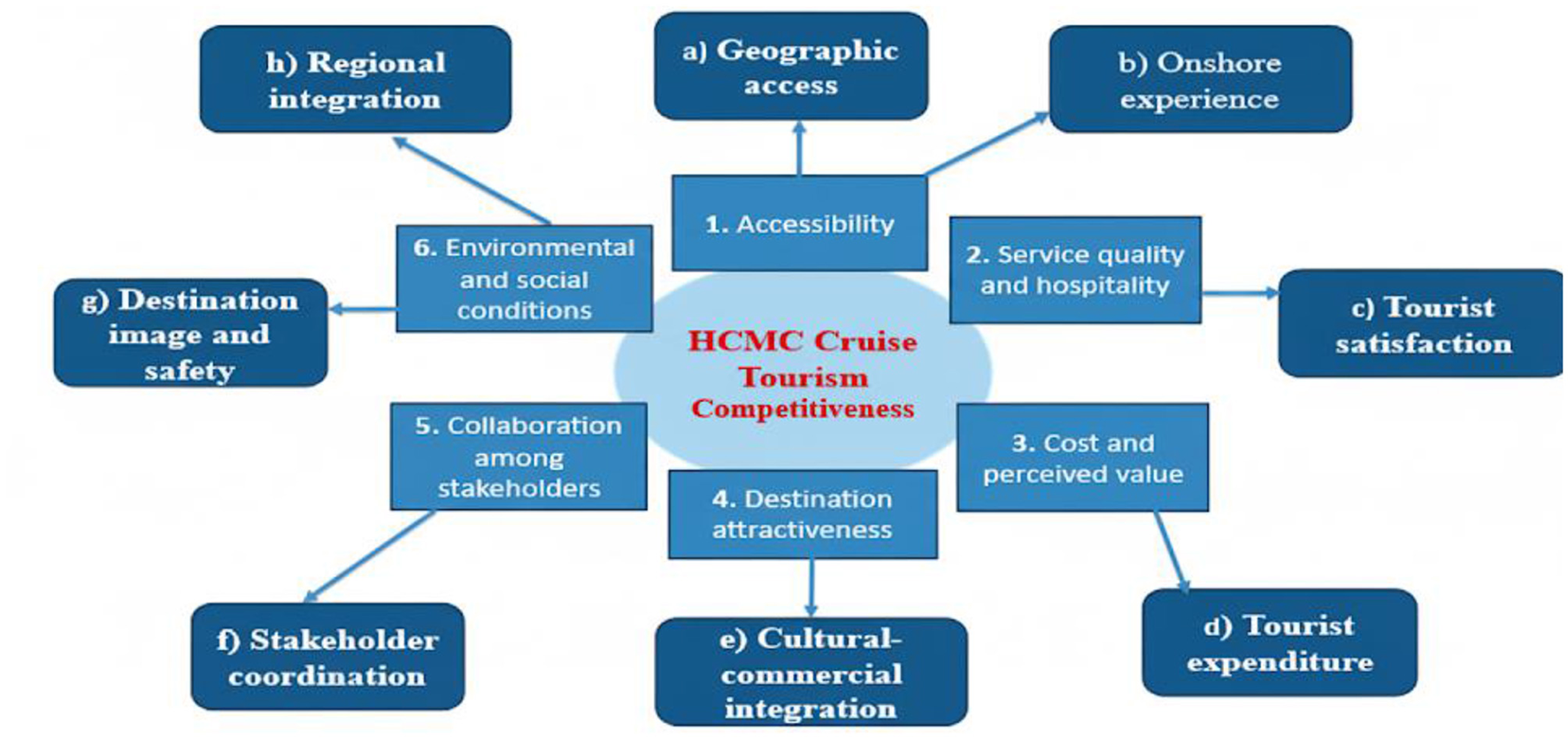

Theoretical Coding: Categories were refined into 8 core dimensions of competitiveness (see Figure 2), addressing the study's theoretical aim to bridge the infrastructure-culture-governance divide in cruise tourism research.

To protect confidentiality, interviewees were anonymized using identifiers (e.g., “Expert01,” “Enterprise03”).

3.4 Research trustworthiness

Three key strategies were implemented to ensure the rigor and trustworthiness of the research findings. First, data saturation was systematically pursued and confirmed by the 22nd interview, following the methodological guidelines established by Guest et al. (2006), at which point no new substantive themes emerged from the data. Second, researcher reflexivity was maintained throughout the study through the consistent use of positionality memos, a technique recommended by Lincoln and Guba (1985) to document and critically examine potential researcher biases that might influence data collection or interpretation. Third, methodological triangulation was employed to strengthen the validity of findings, whereby interview data were systematically cross-verified with field observation notes and relevant policy documents, an approach advocated by Denzin (2017) to provide multiple perspectives on the phenomena under investigation. These complementary strategies collectively enhanced the study's credibility by addressing potential limitations while providing a comprehensive understanding of cruise tourism competitiveness in Ho Chi Minh City.

4 Results and discussion

The findings section provides a detailed analysis of the current state of cruise tourism in Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC), drawing on qualitative insights from key industry stakeholders, including tour operators and subject-matter experts. The data highlight both critical challenges and emerging opportunities across several dimensions—namely, infrastructure, service quality, cultural integration, and stakeholder coordination. These insights are interpreted within the theoretical frameworks of destination competitiveness (Crouch and Ritchie, 1999; Dwyer and Kim, 2003), revealing a notable disconnect between HCMC's advantageous geographic location and its underutilized potential as a regional cruise tourism hub. By exploring empirical themes such as port accessibility, visitor experience, and tourist spending behavior, this section identifies systemic barriers and provides a foundation for actionable strategies aimed at enhancing HCMC's competitiveness within Southeast Asia's growing cruise tourism sector.

4.1 Geographic location and accessibility within Southeast Asia's cruise routes

Stakeholders consistently acknowledged Ho Chi Minh City's (HCMC) strategic position within Southeast Asia's cruise itinerary network. Despite this locational advantage, HCMC struggles to translate geographic proximity into competitiveness due to severe infrastructure limitations and disconnected port-city mobility systems.

A recurrent challenge involves Phu My Port (65 km from downtown). Stakeholders reported peak-hour delays averaging 45–60 min on the Long Thanh Expressway, consuming up to 3 h round-trip (DoanhNghiep008). These inefficiencies are compounded by high emissions from diesel buses, raising concerns about tourist satisfaction and low-carbon development goals. Diesel-dependent transfers directly contradict SDG 13 (Climate Action); electrification could reduce emissions by 30–50% based on ASEAN EV transition studies (Gössling, 2002).

This aligns with Rodrigue and Notteboom's (2013) port-city interface concept, where fragmented transportation weakens economic efficiency. Lucas (2012) further notes such “transport poverty” constrains inclusive tourism participation. Traffic delays could be mitigated via AI routing apps—a machine learning for smart mobility solution—optimizing real-time routes during peak cruise arrivals.

Therefore, improving accessibility requires investments in multimodal hubs, dedicated shuttle lanes, and emissions-aware traffic modeling to align cruise logistics with urban sustainability priorities.

4.2 Shore excursion experiences and port-city transfer services

Shore excursions are critically constrained by long transfers and inadequate smart mobility infrastructure. One operator noted: “We barely have time for two stops after reaching from Hiep Phuoc Port” (DoanhNghiep008). Another emphasized: *“We need mini-hubs near ports—museums, cafes—so tourists don't need to reach District 1”* (DoanhNghiep012).

These inefficiencies increase carbon footprints and costs. Operators rely on diesel buses due to absent EV charging at secondary ports, contradicting electrification of vehicle fleet priorities. Satellite cultural zones within 15–20 min of ports would reduce vehicle-miles travelled by ~40% while enhancing accessibility.

Strategically, this requires:

-

Clean-energy fleets with port-adjacent charging infrastructure

-

Real-time routing systems integrating traffic/emissions data

-

Localized destination development to align with cruise timelines and SDG 11

4.3 Service quality, hospitality, and cruise tourist satisfaction

Persistent service gaps at mobility touchpoints create exclusionary outcomes. The lack of multilingual signage and personnel directly impairs navigation: “Visitors are confused… signage is only in Vietnamese” (DoanhNghiep004). This perpetuates transport disadvantage (Lucas, 2012), systematically excluding non-English speakers—a critical social impact of fragmented mobility systems.

This reflects “experiential friction” (Rodrigue and Notteboom, 2013), highlighting that inclusive design is essential for functional accessibility. Solutions include:

-

Multilingual staff training (Mandarin/Japanese/Korean)

-

Universal signage aligned with ISO 7001 tourism standards

-

Digital wayfinding tools for autonomous mobility

4.4 Spending behavior and consumption patterns of cruise tourists

Cruise tourists generally possess high disposable incomes and seek curated experiences emphasizing cultural authenticity and premium comfort. Although their time at the destination is short, they engage in selective but high-value spending when offerings match their expectations. One operator noted, “Cruise passengers enjoy authentic experiences such as traditional coffee heritage, water puppetry, or folk music performances during dinner” (DoanhNghiep010). These preferences reflect a shift toward personalized and localized travel, in contrast to conventional group tours. Another added, “They are willing to pay for premium products but expect flexible logistics and thoughtfully designed content” (DoanhNghiep004).

This aligns with Sanz-Blas et al. (2019), who found that cruise tourists value authenticity, convenience, and personalization. With its rich cultural diversity, Ho Chi Minh City has strong potential to develop themed heritage tours, craft workshops, and traditional performances tailored to limited shore excursion windows.

Combining these cultural offerings with local cuisine and premium artisanal goods can increase spending and help position the city as a distinctive cruise destination in Southeast Asia.

4.5 Integrating cultural and commercial attractions

A prominent theme emerging from the interviews was the need to develop integrated tourism products that combine cultural heritage with culinary and shopping experiences. This approach enables cruise visitors to make the most of their limited time while enhancing perceived destination value. One expert suggested, “We should move beyond the usual visits to war or history museums. Let's design thematic tours around urban heritage, craft villages, coffee culture, or riverside life” (ChuyenGia009). A tour operator added, “Combining cultural visits with shopping centers or food tours is an effective way to meet the diverse expectations of cruise passengers” (DoanhNghiep007).

These perspectives resonate with the concept of the experience economy, which emphasizes integrating tangible elements, such as products and cuisine, with intangible cultural values to create immersive travel experiences (Buhalis, 2000). In Ho Chi Minh City, well-designed half-day tours centered on themes like French colonial heritage, coffee culture, or traditional markets could improve both tourist satisfaction and spending. Furthermore, integrated tour models can foster collaboration among cultural institutions, retailers, and food businesses, contributing to a sustainable and competitive cruise tourism ecosystem.

4.6 Coordination with government agencies and stakeholders

Institutional fragmentation was identified as a major barrier to the development of cruise tourism in Ho Chi Minh City. Interviewees noted the absence of inter-agency coordination, inconsistent policies, and limited communication among stakeholders as key challenges to integrated planning and product development. One tour operator stated, “It is difficult to develop cruise tourism if port authorities, tour operators, and local government do not work closely together” (DoanhNghiep003). An expert further emphasized the need for a “unified action plan to align infrastructure, transportation, and products with the requirements of the cruise sector” (ChuyenGia002).

These observations support the argument by Dwyer and Kim (2003) that effective destination governance relies on collaborative frameworks in which public-private coordination plays a central role. Establishing dedicated task forces or inter-agency committees focused on cruise tourism could help reduce institutional fragmentation, enhance coordination efficiency, and ensure that development strategies are both market-oriented and grounded in operational realities.

4.7 Safety, security, and destination image

Safety and hygiene are fundamental expectations among cruise tourists and are particularly important in shaping initial impressions of a destination. Although Ho Chi Minh City is generally perceived as safe, interviewees pointed out that traffic congestion, insufficient public cleanliness, and limited crowd management capacity negatively affect the tourist experience. One operator stated, “Some guests complain about chaotic traffic and poor sanitation, which weakens their impression of the city” (DoanhNghiep002). An expert added, “Security and order should be prioritized, especially for visitors unfamiliar with local conditions” (ChuyenGia001).

These concerns align with the findings of Reisinger et al. (2019), who emphasized that safety and hygiene are critical to maintaining a destination's competitive advantage. To enhance its professional image and reception capacity, Ho Chi Minh City should establish and enforce clear safety and service standards at cruise ports, transport hubs, and tourist sites. Improvements in signage, sanitation facilities, and crowd control systems are essential steps to ensure a positive and seamless experience for cruise passengers (Notteboom and Winkelmans, 2001).

4.8 Comparative positioning with Bangkok, Singapore, and Kuala Lumpur (Port Klang)

Compared to leading cruise hubs in the region such as Singapore and Kuala Lumpur, Ho Chi Minh City is recognized for its strong cultural identity but remains behind in infrastructure development and integrated planning. While these cities have made significant investments in dedicated cruise terminals and destination branding, HCMC has yet to achieve a comparable level of strategic alignment. As one expert noted, “Singapore has modern infrastructure, but Ho Chi Minh City has cultural depth—something they lack. Still, we need to head in the right direction” (ChuyenGia004). A tour operator added, “Bangkok and Kuala Lumpur have linked port development with tourism planning, whereas Ho Chi Minh City still treats cruise tourism as secondary” (DoanhNghiep012).

This situation illustrates a form of “dual imperative”: preserving cultural authenticity while simultaneously upgrading infrastructure and governance capacity. As emphasized by Woyo and Slabbert (2023), sustainable destination competitiveness depends not only on resource endowments but also on the ability to adapt and innovate in alignment with industry standards. For Ho Chi Minh City, this means adopting a dual strategy that leverages its cultural capital while professionalizing port services and infrastructure. Such an integrated approach will be essential in strengthening the city's position within Southeast Asia's cruise tourism network.

Figure 1 synthesizes the empirical findings from the qualitative interviews within the broader theoretical framework of destination competitiveness. The diagram visually maps key challenges, such as inadequate port infrastructure, inefficient port-city transfers, and service quality gaps, to foundational concepts in tourism literature, including Crouch and Ritchie's (1999) “supporting resources” and Dwyer and Kim's (2003) model of destination competitiveness. It further illustrates how cultural authenticity and stakeholder coordination interact with infrastructure and governance, reinforcing the dual imperative of preserving uniqueness while meeting global standards (Woyo and Slabbert, 2023). The figure also highlights feedback loops, such as how safety and hygiene concerns or regional competition influence tourist satisfaction and repeat visitation, a dynamic consistent with Hosany and Witham's (2010) findings on emotional responses in cruise tourism.

Figure 1

Diagram linking the theoretical framework and empirical dimensions in the study of cruise tourism competitiveness in Ho Chi Minh City.

By integrating these empirical and theoretical dimensions, Figure 1 underscores the need for a holistic strategy in Ho Chi Minh City's cruise tourism development. Addressing isolated issues, such as port upgrades or service training, without systemic coordination risks perpetuating the gaps identified in this study. Instead, the diagram advocates for synchronized investments in infrastructure, cultural product design, and public-private collaboration to transform the city's geographic and cultural assets into sustained competitive advantages. Ultimately, this framework not only contextualizes the study's findings but also provides an actionable roadmap for policymakers and industry stakeholders to elevate Ho Chi Minh City's position within Southeast Asia's cruise network.

4.9 Systemic interdependence among dimensions of cruise destination competitiveness

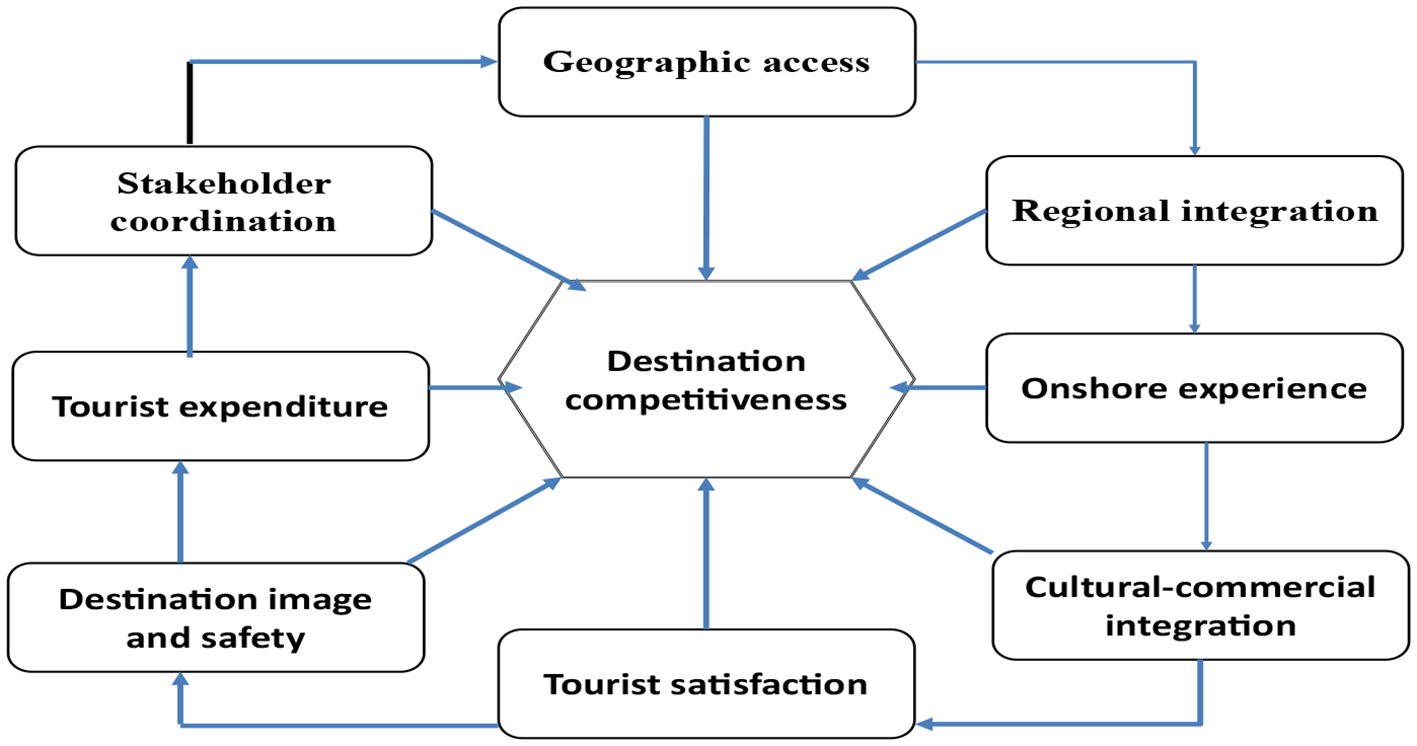

The systemic interdependence among the dimensions of cruise destination competitiveness provides a crucial framework for assessing Ho Chi Minh City's (HCMC) potential as a regional cruise hub. As discussed in earlier sections, cruise tourism development in emerging destinations requires more than isolated improvements; it demands a comprehensive understanding of how multiple elements interact within a complex system. This section synthesizes insights from the qualitative findings into an integrated framework comprising eight key dimensions: accessibility, shore excursion logistics, service quality, spending behavior, cultural-commercial integration, institutional coordination, destination image, and regional integration (see Figure 2). Grounded in well-established theories of destination competitiveness (Crouch and Ritchie, 1999; Dwyer and Kim, 2003) and complex tourism systems (Papathanassis, 2017), this framework reveals the dynamic interactions and feedback loops that collectively shape HCMC's performance and prospects as a cruise tourism destination.

Figure 2

Systemic diagram of dimensions influencing cruise tourism destination competitiveness in Ho Chi Minh City.

Figure 2 visualizes the interconnectedness of the eight dimensions and illustrates how they function as a dynamic and mutually reinforcing system. These dimensions do not operate independently; rather, each may act as a precondition, an enabler, or an outcome of others, contributing to feedback loops that either strengthen or hinder destination competitiveness (Crouch and Ritchie, 1999; Dwyer and Kim, 2003; Papathanassis, 2017).

Accessibility is the foundational condition for cruise tourism. It encompasses the adequacy of port infrastructure, maritime connectivity, and efficient transport between terminals and city attractions. In HCMC, enhancements in deepwater port capabilities, customs processing, and passenger flow management are critical to welcoming larger vessels and delivering seamless initial experiences. Without sufficient accessibility, the city risks being excluded from key regional cruise itineraries.

Shore excursion logistics directly influence how cruise passengers experience HCMC during their brief stay. This dimension involves the organization and delivery of onshore tours, including transportation efficiency, scheduling, guide services, and safety protocols. Inadequate logistics—such as traffic congestion or inconsistent tour offerings—can detract from visitor satisfaction and diminish the city's competitiveness. Well-coordinated excursions ensure that limited port time is maximized, encouraging more positive reviews and return visits.

Closely related is the dimension of service quality, which spans all customer-facing aspects of the cruise tourism experience. Tourists' perceptions are shaped by hospitality, professionalism, hygiene standards, and the ability of service providers to communicate in multiple languages. In the context of HCMC, improving service quality involves targeted workforce development and alignment with international best practices. High service standards can elevate overall satisfaction, counterbalancing limitations in infrastructure or environmental constraints.

Spending behavior reflects the economic footprint of cruise visitors. It includes expenditures on food, souvenirs, entertainment, and cultural experiences. This dimension is influenced by perceived value, accessibility of services, and the attractiveness of local offerings. In HCMC, fostering higher levels of spending requires curated and differentiated experiences that resonate with short-term visitors and encourage discretionary purchases across various sectors.

The integration of cultural and commercial elements adds experiential and economic value to the cruise destination. Cultural-commercial integration involves the presentation of local culture—such as cuisine, crafts, performances, and historical sites—in ways that are both authentic and commercially viable. In HCMC, this integration depends on collaboration among artisans, tourism operators, retailers, and local authorities. Without coordination, cultural products may be underdeveloped, misrepresented, or poorly marketed, missing the opportunity to differentiate the city from competitors.

Institutional coordination is a cross-cutting enabler of all other dimensions. It refers to the degree of policy coherence, inter-agency collaboration, and strategic alignment among key stakeholders. In HCMC, fragmented governance structures and inconsistent planning have historically limited the effectiveness of cruise tourism initiatives. Strengthening institutional coordination is essential for leveraging investments, streamlining logistics, and enhancing service standards through unified goals and shared accountability.

Destination image represents both a cause and a consequence within the tourism system. It encompasses the perceptions that potential visitors and cruise operators hold about HCMC in terms of safety, cleanliness, friendliness, and cultural richness. This image is shaped by pre-visit marketing as well as on-site experiences. A positive destination image reinforces competitiveness by attracting more cruise lines and visitors, whereas negative impressions can deter interest regardless of other improvements. In this regard, managing reputation and ensuring consistency in service delivery are paramount.

Finally, regional integration is the extent to which HCMC is embedded in broader Southeast Asian cruise networks. It involves participation in regional marketing, adherence to international standards, and strategic cooperation with nearby destinations. When properly integrated, HCMC becomes not just a stop but a key node in multi-country itineraries, benefiting from regional synergies. Achieving this requires diplomatic engagement, joint infrastructure development, and coordination with cruise operators and government bodies (Gui and Russo, 2011; Woyo and Slabbert, 2023).

Together, these dimensions form a complex but coherent system. Improvements in one area may catalyze positive effects in others—for example, better service quality enhances destination image, which in turn increases demand and justifies infrastructure investment. Conversely, deficiencies in one domain—such as poor institutional coordination—can undermine gains elsewhere, creating inefficiencies or reputational damage. As depicted in Figure 2, sustainable and competitive cruise tourism development in HCMC depends not on isolated efforts but on systemic alignment across all dimensions.

Enhancing the competitiveness of cruise tourism in emerging destinations such as HCMC requires a holistic, systems-oriented strategy. Addressing individual dimensions in isolation will not yield lasting progress; instead, stakeholders must pursue structural coherence, foster cross-sector collaboration, and implement adaptive governance that reflects the interdependent nature of the cruise tourism ecosystem.

Figure 2 crystallizes these complexities, illustrating how the dynamic interplay among accessibility, logistics, service quality, economic engagement, cultural integration, governance, image, and regional positioning can either accelerate or constrain Ho Chi Minh City's development as a regional cruise hub. This systemic diagram of the eight interconnected dimensions shaping cruise tourism competitiveness in Ho Chi Minh City represents a significant advancement in theoretical understanding.

First, the diagram emphasizes dynamic interdependencies by adopting a circular, non-hierarchical structure that reflects the reciprocal nature of the relationships among dimensions. This contrasts with more linear models such as Dwyer and Kim's (2003) framework. The directional arrows in the figure demonstrate how cultural-commercial integration both influences and is shaped by institutional coordination, forming feedback loops. These interactions, which are absent in many traditional tourism competitiveness models, underscore the complex, mutually reinforcing relationships that govern cruise port development.

Second, the diagram captures context-specific synergies by placing “stakeholder collaboration” at the center. This central positioning reflects the empirical finding that governance quality serves as a mediating force, determining whether investments in infrastructure and services effectively enhance visitor experiences. In emerging markets like Vietnam, where bureaucratic inefficiencies and fragmented authority are common, this insight highlights a critical factor often neglected in Western-centric models of tourism development (Wondirad, 2019). By focusing on collaboration, the framework acknowledges that institutional cohesion is a prerequisite for sustainable competitiveness.

Third, the diagram incorporates time-sensitive resource allocation through its use of color-coded segments, which reveal how short-stay cruise contexts alter traditional priorities. Specifically, cultural assets (highlighted in orange) and service logistics (in blue) emerge as equally important as physical infrastructure (in green), challenging the resource hierarchy typical of land-based tourism models (Crouch and Ritchie, 1999). This visual cue prompts scholars and planners to rethink how temporal characteristics of cruise tourism affect investment strategies and development goals.

Ultimately, the diagram provides researchers with a valuable analytical tool for examining secondary cruise ports, especially in developing economies where institutional and cultural variables exert outsized influence. It moves beyond static frameworks by integrating interdependencies, local governance realities, and temporal dimensions, offering a more nuanced and actionable understanding of cruise tourism competitiveness in transitional urban contexts like Ho Chi Minh City.

By adopting this systemic perspective, HCMC can leverage its strategic location, cultural heritage, and economic aspirations into a cohesive and compelling cruise offering. A coordinated approach that aligns infrastructure upgrades, service excellence, and institutional leadership will not only boost the city's attractiveness to cruise operators but also position HCMC as a distinctive and integrated player in Southeast Asia's cruise tourism landscape.

5 Research implications

5.1 Theoretical implications

This study makes three significant theoretical contributions that advance our understanding of cruise tourism competitiveness.

First, by integrating systems theory into destination competitiveness, our framework (Figure 2) reconceptualizes the construct as a dynamic system characterized by non-linear interactions among multiple dimensions. These challenges the static, hierarchical assumptions embedded in earlier models by Crouch and Ritchie (1999) and Dwyer and Kim (2003). We illustrate how limitations in physical infrastructure in Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC) generate ripple effects that degrade the quality of cultural experiences, whereas strong stakeholder coordination can mitigate these constraints. These interdependencies, often overlooked in mainstream literature, address critiques about the oversimplification of destination systems (Wondirad, 2019; Lau et al., 2022). The systemic perspective offered is particularly salient for cruise tourism, where the compressed timeframe of visitor experiences intensifies the mutual dependencies between infrastructure, service quality, and cultural offerings.

Second, the study foregrounds stakeholder-centric governance as a mediating force in competitive performance. Although governance challenges are well-documented in tourism literature (Byrd, 2007; Dredge, 2006), we make a novel contribution by positioning institutional coordination as the linchpin that enables or constrains all other competitiveness dimensions. Our empirical findings reveal the specific power asymmetries in Vietnam between state-owned port authorities and private tourism operators, which create structural disadvantages absent in Western contexts that presume collaborative or decentralized governance models. This insight extends the Dwyer and Kim (2003) model by situating governance within local institutional realities, echoing Gui and Russo's (2011) argument that governance systems must adapt to context-specific power dynamics and administrative structures.

Third, we advance the valuation of cultural resources within time-constrained tourism contexts, thereby extending the Resource-Based View (RBV) articulated by Barney (1991). Unlike traditional RBV applications that privilege tangible assets such as ports and transport infrastructure (Cucculelli and Goffi, 2016), our study demonstrates that intangible cultural elements—such as heritage crafts, authentic cuisine, and localized storytelling—acquire strategic value when curated into meaningful experiences during the 4–8-h shore excursions typical of cruise itineraries. These resources become valuable, rare, and inimitable not through their inherent properties alone, but through their effective integration into the temporally limited tourist experience, supporting the arguments made by Sanz-Blas et al. (2019). This contribution also responds directly to Novais et al.'s (2018) call for more context-sensitive approaches to resource valuation.

Collectively, these contributions bridge key gaps in the literature by aligning cruise-specific dynamics with broader destination competitiveness frameworks, challenging Western-centric theoretical assumptions through Southeast Asian empirical insights, and shifting the emphasis from infrastructure-heavy to experience-driven development paradigms. The framework's focus on cultural-institutional synergies also answers Pham et al. (2023) call for research that captures the unique value-creation processes emerging in Asian tourism markets. Future research should build on these foundations by exploring how similar dynamics operate across different types of cruise ports and varying governance regimes, offering a more granular understanding of competitiveness in diverse regional contexts.

5.2 Practical implications

To enhance the competitiveness of Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC) as a cruise tourism destination, this study highlights several practical implications rooted in integrated mobility, governance innovation, and experience optimization.

First, address port-city mobility constraints with cruise-specific transport solutions. The current dependence on distant ports (e.g., Phu My, Hiep Phuoc) necessitates urgent action to minimize transfer times, reduce emissions, and enhance tourist convenience. Proposed solutions include:

-

Electric Vehicle (EV) shuttle networks operating between cruise terminals and key attractions (e.g., Ben Thanh Market, Cu Chi Tunnels, Saigon Opera House) to reduce carbon footprints and provide consistent service quality.

-

Dynamic pricing models for peak-hour port transfers, using demand-responsive transport strategies to manage congestion while incentivizing off-peak scheduling.

-

App-based mobility integration platforms offering real-time tracking and unified ticketing systems that bundle ferries, shuttle buses, and urban transit passes into a single, digitally accessible interface.

These innovations directly respond to the cruise tourism sector's compressed time constraints and high passenger volume during port calls, ensuring seamless, low-emission, and tourist-friendly movement within the city.

Second, tie governance reform to the development of new business models. As noted in Section 4.6, fragmented institutional coordination remains a major bottleneck. To overcome this, we recommend that the city pilot public-private partnerships (PPPs) for integrated mobility platforms. These PPPs would facilitate shared investment in digital infrastructure, fleet modernization, and service interoperability—while aligning incentives between government agencies, transport operators, and tourism stakeholders.

Such arrangements support the emergence of destination-as-a-platform models, where mobility, cultural experience, and tourism services are offered as a unified value proposition. This would reflect an evolution from traditional, siloed tourism governance to networked service ecosystems, aligning with recent trends in smart city and tourism convergence (Gretzel et al., 2015).

Third, redesign shore excursions around mobility efficiency and cultural differentiation. Tour operators are encouraged to move beyond centralized downtown itineraries and develop localized micro-experiences near the ports. This could involve:

-

Pop-up markets or heritage showcases within port zones.

-

Compact cycling or walking tours supported by multilingual wayfinding apps.

-

Culinary tasting events hosted in collaboration with local communities.

These innovations not only reduce transfer burdens but also support distributed economic benefits across districts, in line with inclusive tourism goals.

Fourth, support mobility literacy among cruise passengers. Enhancing wayfinding and onboarding visitors through mobile apps, multilingual signage, and pre-arrival briefings can improve tourist autonomy and reduce dependency on tightly guided tours. This approach reinforces both service personalization and sustainability.

In summary, mobility is not just a logistical concern—it is a strategic enabler of cruise tourism competitiveness. HCMC's ability to deliver seamless, sustainable, and culturally immersive mobility experiences will determine whether it can transform geographic proximity into economic and reputational advantage within Southeast Asia's cruise circuit.

Synchronizing these mobility innovations with branding, service standardization, and institutional coordination provides a realistic pathway toward positioning HCMC as a culturally rich, professionally managed, and regionally integrated cruise destination.

6 Conclusion

This study has explored the multifaceted factors influencing the competitiveness of Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC) as an emerging cruise tourism destination in Southeast Asia. Drawing on qualitative interviews with key stakeholders, the research identified eight interrelated dimensions: accessibility, shore excursion logistics, service quality, tourist spending behavior, cultural-commercial integration, institutional coordination, destination image, and regional integration. Together, these dimensions form a dynamic and interdependent system, where deficiencies or enhancements in one area can significantly impact the overall competitiveness of the destination (Crouch and Ritchie, 1999; Dwyer and Kim, 2003).

Theoretically, the study reconceptualizes cruise tourism competitiveness as a dynamic, context-sensitive system in which cultural-commercial integration and stakeholder coordination are as crucial as traditional infrastructure. By grounding these insights in the context of an emerging Asian city, the study challenges the Western-centric assumptions of earlier models that prioritize physical infrastructure while downplaying institutional and cultural capacities (Wondirad, 2019; Lau et al., 2022). The framework illustrates that in short-stay cruise scenarios, experiential authenticity and governance agility can compensate for resource gaps, offering new theoretical directions for the development of cruise destinations.

Although HCMC benefits from strategic geographic positioning and rich cultural assets, the findings reveal that its competitiveness as a cruise hub remains underrealized. Key barriers include fragmented infrastructure, weak stakeholder collaboration, and a lack of tailored tourism products designed for the short duration of cruise visits. The city's reliance on remote ports, inefficient transport linkages, and uneven service quality further constrain its ability to compete with more established regional hubs such as Singapore and Bangkok. Nevertheless, the study highlights an important opportunity: HCMC can differentiate itself by leveraging its deep cultural resources and authenticity—qualities increasingly sought by cruise tourists looking for immersive experiences (Sanz-Blas et al., 2019; Woyo and Slabbert, 2023).

To address these challenges, the study proposes a systemic strategy that involves synchronized investments across three core areas: infrastructure, experience design, and governance innovation. On the infrastructure front, developing purpose-built cruise terminals closer to the city center and improving multimodal transport systems are essential to enhancing accessibility and reducing transit inefficiencies. These improvements would allow tourists to spend more time engaging with cultural experiences rather than navigating logistical hurdles.

Experience design must also be prioritized. Given the limited time cruise passengers spend ashore, it is vital to offer culturally immersive excursions that deliver high-impact, memorable experiences within a few hours. These should draw from HCMC's distinctive heritage, crafts, and culinary offerings, packaging them into compelling narratives that meet global cruise expectations. This aligns with Buhalis's (2000) notion of the experience economy, which emphasizes the staging of meaningful, transformative encounters.

Equally critical is governance innovation. The study underscores the need for cross-sectoral coordination among public authorities, port operators, private tourism businesses, and cultural institutions. Effective collaboration can overcome current governance fragmentation and ensure that tourism strategies are cohesive and aligned. This approach operationalizes theoretical frameworks of destination competitiveness (Ritchie and Crouch, 2003) by demonstrating how institutional synergies can bridge the gap between cultural assets and market demand.

The study makes three key contributions to tourism scholarship. First, it extends destination competitiveness theory to the cruise tourism context in emerging markets, addressing limitations in existing models that are largely built on land-based tourism in developed regions. By incorporating the spatial and temporal constraints unique to cruise settings, the research enhances the theory's relevance and applicability. Second, it introduces cultural-commercial integration as a central dimension of competitiveness. The ability to merge cultural heritage with commercial tourism products is shown to be particularly important in short-stay contexts, where time constraints demand efficient yet authentic engagement. Third, the study highlights the mediating role of institutional coordination in resource-limited environments. In places where infrastructure falls short, collaborative governance can be a decisive factor in elevating destination performance.

While this research is rooted in HCMC's specific context, the proposed framework offers valuable insights for other secondary cruise ports in emerging markets. Future studies should adopt mixed-method approaches to quantify the interrelationships among the identified dimensions and validate the framework's applicability through comparative studies across ASEAN cruise destinations. Such efforts would enhance both theoretical depth and practical utility for tourism planners and policymakers.

In conclusion, HCMC's path to cruise tourism competitiveness lies in its ability to recognize and activate its cultural and institutional strengths. When strategically coordinated, these assets can not only offset infrastructure limitations but also position the city as a distinctive and desirable stop in Southeast Asia's growing cruise tourism circuit. This study offers both a conceptual foundation and an actionable roadmap to guide that transformation, contributing meaningfully to the broader discourse on tourism development in emerging global regions.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/supplementary material.

Ethics statement

The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

TT: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PN: Conceptualization, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. BM: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Software, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. TKTN: Formal analysis, Resources, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. TLCN: Data curation, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. TL: Data curation, Formal analysis, Resources, Software, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Barney J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag.17, 99–120. 10.1177/014920639101700108

2

Brida J. G. Zapata S. (2010). Economic impacts of cruise tourism: the case of Costa Rica. Anatolia21, 322–338. 10.1080/13032917.2010.9687106

3

Buhalis D. (2000). Marketing the competitive destination of the future. Tour. .ement21, 97–116. 10.1016/S0261-5177(99)00095-3

4

Byrd E. T. (2007). Stakeholders in sustainable tourism development and their roles: applying stakeholder theory to sustainable tourism development. Tour. Rev.62, 6–13. 10.1108/16605370780000309

5

Carić H. (2016). Challenges and prospects of valuation–cruise ship pollution case. J. Clean. Prod.111, 487–498. 10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.01.033

6

CLIA (2023). 2023 Cruise Industry Outlook. Cruise Lines International Association. Available online at: https://cruising.org (Accessed August 8, 2025).

7

Creswell J. W. (2012). Educational Research Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research, 4th Ed.Boston, MA: Pearson.

8

Crouch G. I. Ritchie J. B. (1999). Tourism, competitiveness, and societal prosperity. J. Bus. Res.44, 137–152. 10.1016/S0148-2963(97)00196-3

9

Cucculelli M. Goffi G. (2016). Does sustainability enhance tourism destination competitiveness? Evidence from Italian destinations of excellence. J. Clean. Prod.111, 370–382. 10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.12.069

10

Denzin N. K. (2017). The Research Act: A Theoretical Introduction to Sociological Methods, 3rd Edn. New York, NY: Routledge. 10.4324/9781315134543

11

Dredge D. (2006). Policy networks and the local organisation of tourism. Tour. Manag.27, 269–280. 10.1016/j.tourman.2004.10.003

12

Dwyer L. Edwards D. Mistilis N. Roman C. Scott N. (2009). Destination and enterprise management for a tourism future. Tour. Manag.30, 63–74. 10.1016/j.tourman.2008.04.002

13

Dwyer L. Kim C. (2003). Destination competitiveness: determinants and indicators. Curr. Issues Tour.6, 369–414. 10.1080/13683500308667962

14

Enright M. J. Newton J. (2005). Determinants of tourism destination competitiveness in Asia Pacific: comprehensiveness and universality. J. Travel Res.43, 339–350. 10.1177/0047287505274647

15

Forsyth P. Dwyer L. Spurr R. Pham T. (2014). The impacts of Australia's departure tax: tourism versus the economy?Tour. Manag.40, 126–136. 10.1016/j.tourman.2013.05.011

16

Glaser B. Strauss A. (2017). Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. New York, NY: Routledge. 10.4324/9780203793206

17

Go F. M. Govers R. (2000). Integrated quality management for tourist destinations: a European perspective on achieving competitiveness. Tour. Manag.21, 79–88. 10.1016/S0261-5177(99)00098-9

18

Gomezelj D. O. Mihalič T. (2008). Destination competitiveness—applying different models, the case of Slovenia. Tour. Manag.29, 294–307. 10.1016/j.tourman.2007.03.009

19

Gössling S. (2002). Global environmental consequences of tourism. Glob. Environ. Change12, 283–302. 10.1016/S0959-3780(02)00044-4

20

Gretzel U. Sigala M. Xiang Z. Koo C. (2015). Smart tourism: foundations and developments. Electron. Markets25, 179–188. 10.1007/s12525-015-0196-8

21

Guest G. Bunce A. Johnson L. (2006). How many interviews are enough?Field Methods18, 59–82. 10.1177/1525822X05279903

22

Gui L. Russo A. P. (2011). Cruise ports: a strategic nexus between regions and global lines-evidence from the Mediterranean. Maritime Policy Manage.38, 129–150. 10.1080/03088839.2011.556678

23

Hall C. M. (2008). Tourism Planning: Policies, Processes and Relationships, 2nd Edn. Harlow: Pearson Education.

24

Hesse-Biber S. N. Leavy P. (2010). The Practice of Qualitative Research, 2nd Edn.Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

25

Hosany S. Witham M. (2010). Dimensions of cruisers' experiences, satisfaction, and intention to recommend. J. Travel Res.49, 351–364. 10.1177/0047287509346859

26

Hritz N. Cecil A. K. (2008). Investigating the sustainability of cruise tourism: a case study of Key West. J. Sustain. Tour.16, 168–181. 10.2167/jost716.0

27

Hudson S. Ritchie J. R. B. Timur S. (2004). Measuring destination competitiveness: an empirical study of Canadian ski resorts. Tour. Hosp. Plann. Dev.1, 79–94. 10.1080/1479053042000187810

28

Hung K. Petrick J. F. (2011). Why do you cruise? Exploring the motivations for taking cruise holidays, and the construction of a scale to measure the motivation. Tour. Manag.32, 386–393. 10.1016/j.tourman.2010.03.008

29

Hung K. P. Peng N. Chen A. (2019). Incorporating on-site activity involvement and sense of belonging into the Mehrabian-Russell model–The experiential value of cultural tourism destinations. Tour. Manag. Perspect.30, 43–52. 10.1016/j.tmp.2019.02.003

30

Kozak M. (2003). Measuring tourist satisfaction with multiple destination attributes. Tour. Anal.7, 229–240. 10.3727/108354203108750076

31

Lau Y. Y. Yip T. L. Kanrak M. (2022). Fundamental shifts of cruise shipping in the post-Covid-19 era. Sustainability14:14990. 10.3390/su142214990

32

Lincoln Y. S. Guba E. G. (1985). Naturalistic Inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. 10.1016/0147-1767(85)90062-8

33

Lucas K. (2012). Transport and social exclusion: where are we now?Transp. Policy20, 105–113. 10.1016/j.tranpol.2012.01.013

34

Madsen P. A. Fuhrman D. R. Schäffer H. A. (2008). On the solitary wave paradigm for tsunamis. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans113, 1–22. 10.1029/2008JC004932

35

Mohamad B. Adetunji R. R. Alarifi G. Rageh A. (2022). A visual identity-based approach of Southeast Asian City branding: a netnography analysis. J. ASEAN Stud.10, 21–42. 10.21512/jas.v10i1.7330

36

Notteboom T. Winkelmans W. (2001). Structural changes in logistics: how will port authorities face the challenge?Marit. Policy Manag.28, 71–89. 10.1080/03088830119197

37

Novais M. A. Ruhanen L. Arcodia C. (2018). Destination competitiveness: a phenomenographic study. Tour. Manag.64, 324–334. 10.1016/j.tourman.2017.08.014

38

Papathanassis A. (2017). Cruise tourism management: state of the art. Tour. Rev.72, 104–120. 10.1108/TR-01-2017-0003

39

Papathanassis A. Beckmann I. (2011). Assessing the ‘poverty of cruise theory' hypothesis. Ann. Tour. Res.38, 153–174. 10.1016/j.annals.2010.07.015

40

Papatheodorou A. (2002). Exploring competitiveness in Mediterranean resorts. Tour. Econ.8, 133–150. 10.5367/000000002101298034

41

Parasuraman A. Zeithaml V. A. Berry L. L. (1988). SERVQUAL: a multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. J. Retail.64, 12–40.

42

Pham L. H. Woyo E. Pham T. H. Truong D. T. X. (2023). Value co-creation and destination brand equity: understanding the role of social commerce information sharing. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights6, 1796–1817. 10.1108/JHTI-04-2022-0123

43

Pham V. P. H. Le A. Q. (2024). ChatGPT in language learning: perspectives from Vietnamese students in Vietnam and the USA. Int. J. Lang. Instruct. 3. 10.54855/ijli.24325

44

Reisinger Y. Michael N. Hayes J. P. (2019). Destination competitiveness from a tourist perspective: a case of the United Arab Emirates. Int. J. Tour. Res.21, 259–279. 10.1002/jtr.2259

45

Ritchie J. B. Crouch G. I. (2003). The Competitive Destination: A Sustainable Tourism Perspective. Cabi.

46

Rodrigue J. P. Notteboom T. (2013). The geography of cruises: itineraries, not destinations. Appl. Geograp.38, 31–42. 10.1016/j.apgeog.2012.11.011

47

Sanz-Blas S. Buzova D. Carvajal-Trujillo E. (2019). Familiarity and visit characteristics as determinants of tourists' experience at a cruise destination. Tour. Manag. Perspect.30, 1–10. 10.1016/j.tmp.2019.01.005

48

So du lich TP.HCM (2024). Annual Tourism Report 2023–2024. Ho Chi Minh City: Ho Chi Minh City Department of Tourism.

49

Soedarsono D. K. Mohamad B. Adamu A. A. Pradita K. A. (2020). Managing digital marketing communication of coffee shop using instagram. Int. J. Interact. Mobile Technol.14, 108–118. 10.3991/ijim.v14i05.13351

50

Veal A. J. Darcy S. (2014). Research Methods in Sport Studies and Sport Management: A Practical Guide. London: Routledge. 10.4324/9781315776668

51

Viña L. D. L. Ford J. (2001). Logistic regression analysis of cruise vacation market potential: demographic and trip attribute perception factors. J. Travel Res.39, 406–410. 10.1177/004728750103900407

52

Vlăsceanu C. F. Ţigu G. (2020). Competitiveness in global hospitality and cruising industry. New Trends Sust. Business Consumpt.1117, 1117–1124.

53

Wondirad A. (2019). Retracing the past, comprehending the present and contemplating the future of cruise tourism through a meta-analysis of journal publications. Mar. Policy108:103618. 10.1016/j.marpol.2019.103618

54

Woyo E. Slabbert E. (2023). Competitiveness factors influencing tourists' intention to return and recommend: evidence from a distressed destination. Dev. South. Afr.40, 243–258. 10.1080/0376835X.2021.1977612

Summary

Keywords

cruise tourism, destination competitiveness, Ho Chi Minh City, stakeholder collaboration, sustainable mobility

Citation

Tran TT, Nguyen PH, Mohamad B, Nguyen TKT, Nguyen TLC and Le TH (2025) Port-city mobility challenges in Ho Chi Minh City: cruise tourism infrastructure, stakeholder governance, and sustainable urban transitions. Front. Sustain. Cities 7:1679677. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2025.1679677

Received

05 August 2025

Accepted

06 October 2025

Published

23 October 2025

Volume

7 - 2025

Edited by

Richard Kotter, Northumbria University, United Kingdom

Reviewed by

Sanhakot Vithayaporn, Stamford International University, Thailand

Ewa Hacia, Maritime University of Szczecin, Poland

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Tran, Nguyen, Mohamad, Nguyen, Nguyen and Le.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Trong Thanh Tran thanhtt@uef.edu.vn

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.