Abstract

The Chinese Sponge City Initiative (SCI) seeks to reconcile the tension between urban development and environmental protection by prioritizing nature-based solutions to urban water management. As might be expected, the existing literature on the SCI is predominantly technical and engineering based. There is a dearth of writing on how this broad reaching green policy shapes people and place. This paper explores the SCI through hydrosocial and place-based lenses, revealing the importance of the local scale in this national policy. It is at the local scale that the conversation about the SCI enables contestation of infrastructure, economic and environmental values. The SCI is concerned with the environment, but at the same time is clearly being leveraged to support new business and a form of Chinese gentrification. This fosters a more exclusive and arguably atomised urban form without obvious gains for urban socio-natural assemblages beyond individual wealth generation. Attempts to seek new forms of environmental politics show promise, particularly cooperative governance. But there remains a narrowness in building collective relational futures, in part due to a lack of explicit consideration of the way that SCI speaks to histories, cultures and place. Ultimately, this paper is about Chinese cities and how the SCI serves to rework place. The analysis makes clear that the SCI is not simply a neutral and purely technical instrument of urban resilience, but rather a politically charged project whose outcomes are shaped by the contested politics of place. In doing so, the paper invites a more critical understanding of the SCI and, more broadly, of the everyday political dynamics underpinning sustainable urban policy.

1 Introduction

This paper considers the major national policy of the Sponge City Initiative (SCI) and how it acts to rework contemporary life in Chinese cities. It is not an empirical study as such but is instead built on the experience of the lead author who has grown up in Chinese cities and has become a critical scholar who considers urban change through the lens of water and infrastructure. The aim is to open-up the conversation about the radical reconstruction of Chinese cities and consider how environmental programmes are situated and contested in the urban environment. The paper follows a simple structure, starting with a literature review to provide the theoretical context before moving to an analysis and description of urban typology that are typically found in Chinese cities. The discussion then moves to consider how SCI policy is supported or contested by people living in different urban places and how these things interact to create new urban environments and its people. Ultimately the paper reveals that the SCI is less a neutral tool of urban resilience than a political project shaped by the contested everyday politics of place. It underscores the overlooked importance of the local scale in hydrosocial analysis and calls for a more critical view of wide-reaching sustainability policy.

The SCI is a major sustainability policy that was launched in China in 2015 and was born out of a conversations about the need for environmentally framed urban development (Chan et al., 2018; MoHURD, 2014). The conversation built on a Western critique of command-and-control, pipe-logics to urban water management, that were widely criticized for a lack of adaptability and resilience in the face of climate change (e.g., Fletcher et al., 2015). In essence, the SCI strives to reconcile the tensions between urban development and environmental protection. The premise of the approach is captured in its name, with an overarching aim to provide more than 80% of the built-up urban area as a ‘sponge’ capable of retaining at least 70% of rainfall on-site (Council, 2015). Mirroring similar global efforts to change urban water management (e.g., Fletcher et al., 2015), the use of decentralized nature-based solutions are touted as more sustainable alternatives to centralized, large-scale, grey water infrastructure.

Of course, urban water management is dominated by reductionist forms of knowledge and rational bargaining that seek ‘solutions’ to ‘problems’ (Sofoulis, 2011). A dualistic view of nature/ society persists, which regards water (and nature) as somewhat separate and distinct from society. Water, then, is either subject to human control or a natural force acting upon human societies. These entrenched paradigms are the logic underpinning piped urban water infrastructure. Rationality, efficiency, and control are celebrated and these ideas become entrenched in modern urban development to serve the modern state itself (Scott, 1998).

As a result, the urban water literature tends to consider the performance of urban stormwater devices in-situ and in-silico (e.g., Elliott and Trowsdale, 2007). The dominant centralized, technocratic and administrative mindset neglects local diversity in favor of cookie cutter approaches packaged in the appealing rhetoric of being ‘nature-based solutions’ (Karvonen, 2011; Li, 2019; Gandy, 2014). The many ways in which water speaks to people are depoliticized as is the work of the hydrologist and urban planner (Swyngedouw, 2010; Larner, 2014; Trowsdale et al., 2020). Indeed, little attention has been paid to the social, political, and spatial dynamics of such socio-technical transitions, particularly so in China.

The turn of the 21st century ushered in different ways of thinking about relationships between ‘geo’ and ‘bio’, which led (in the theoretical literature at least) to a collapse of boundaries and the coining of terms that brought ‘things’ together in a move towards relational and process-based understandings (Castree, 2001). Soon afterwards, hydrosocial perspectives were developed (e.g., Swyngedouw, 2009; Linton and Budds, 2014; Wesselink et al., 2017) that attempt to reframe water-society as mutually constituted and produced through ever-becoming social-environmental processes (Swyngedouw, 1996). The concept works with complex and dynamic relationships between water-society as a socio-natural hybrid, mediated by situated water, infrastructure and place.

Place is a foundational concept in geography, which arguably captures some aspects of the hydrosocial. Place is a produced nature, a crystallization of historical/political/social relations formed by the interaction of space/time (Swyngedouw, 2004). There is an ongoing discussion regarding the nuanced difference between space and place, and what has been termed ‘splace’ (Wainwright and Barnes, 2009). Taking our prompt from such debates, and recognizing our desire to focus on the SCI, we adopt the term ‘place’ throughout this paper as, for us at least, it perhaps best represents the interactions of situated socio-natural processes that shape everyday experiences. This guides the paper towards a narrative about the ways in which water-society are co-constituted in modern Chinese cities, with local place being the keystone where [socio]waters become intertwined with histories, cultures, knowledges, and desires (e.g., Boelens, 2014; Boelens et al., 2016; Wesselink et al., 2017).

There are more than traces of similar thinking in the Chinese context, unsurprisingly given the long history of the ‘three teachings’ along with a pervasive folk religion that have worked to shape Chinese culture and social norms. Traditional Chinese philosophy, known as ‘tianrenheyi (天人合一),’ aligns with socio-nature and the hydrosocial, and emphasizes that nature and society are not separate but deeply intertwined. This is enshrined in Buddhist and Taoists thinking that seeks harmonious appreciations of the nature of the universe (Jinguang, 2013). More recently, the notion of eco-civilization (生态文明) championed by the Chinese central government as the guiding concept for all eco-centered policies and programs aimed to align with such ways-of-knowing. It stresses adherence to the harmonious coexistence of man and nature (although other interpretations also exist; see Hansen et al., 2018). The SCI is tasked with the promotion of such eco-civilization. Few, however, have questioned the nature of the ‘civilization’ that SCI promotes. In other words, what kind of place; what kind of city; what kind of hydrosociety does the SCI promote?

Now we have established the theoretical foundations, the paper proceeds in three steps. We begin by introducing a typology of urban forms in Chinese cities, broadly based on different types of residential, industrial, and commercial development that are typically found. These are developed through lived experience, mapping, and place-based description. The typologies provide the basis for examining how SCI interventions are interpreted and enacted locally drawing on Linton and Budds (2014) notions of the hydrosocial. The analysis highlights how the SCI is supported, resisted, or repurposed in different contexts, and how these practices reshape hydrosocial relations. Finally, we show that the SCI is not a uniform technical programme but is in fact a locally contested project, at times enabling more collective and inclusive forms of governance, yet more often reinforcing a type of exclusionary and gentrified urbanism.

2 Theoretical framework

The changing nature of Chinese cities is explored by building urban typologies based on firsthand experience living in Chinese cities and by mapping and describing typical physical attributes such as buildings, greenspace, infrastructure and the use of space. To situate these in the hydrosocial context, we describe the historical, cultural, and social contexts of each based on our experience of living, working and playing in such places. While the approach is necessarily subjective and experiential, and thus not reproducible in the conventional scientific sense, this reflects a broader epistemological challenge in environmental research, particularly that conducted in the field (Gahegan, 2023). As Haraway (1988) reminds us, all knowledge is inherently partial, plural, and situated, a perspective that underpins the interpretive stance of this study. Relationships between water-technology-society are used as an entry point into thinking relationally about how the SCI works to transform place. The paper then turns to discuss the socio-political understandings of this major green policy in China in terms of local scale support for and resistance of SCI place-making. A place-based framework underpins the investigation and frames how we understand the SCI to simultaneously rework space, technology and culture. Place, then, is used throughout this paper as a term to encompass co-constitution drawing on the notion of the hydrosocial cycle, providing a route into the examination of SCI place-based transformations (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Place-based cycle after Linton and Budds (2014).

3 Urban typologies typical of Chinese cities

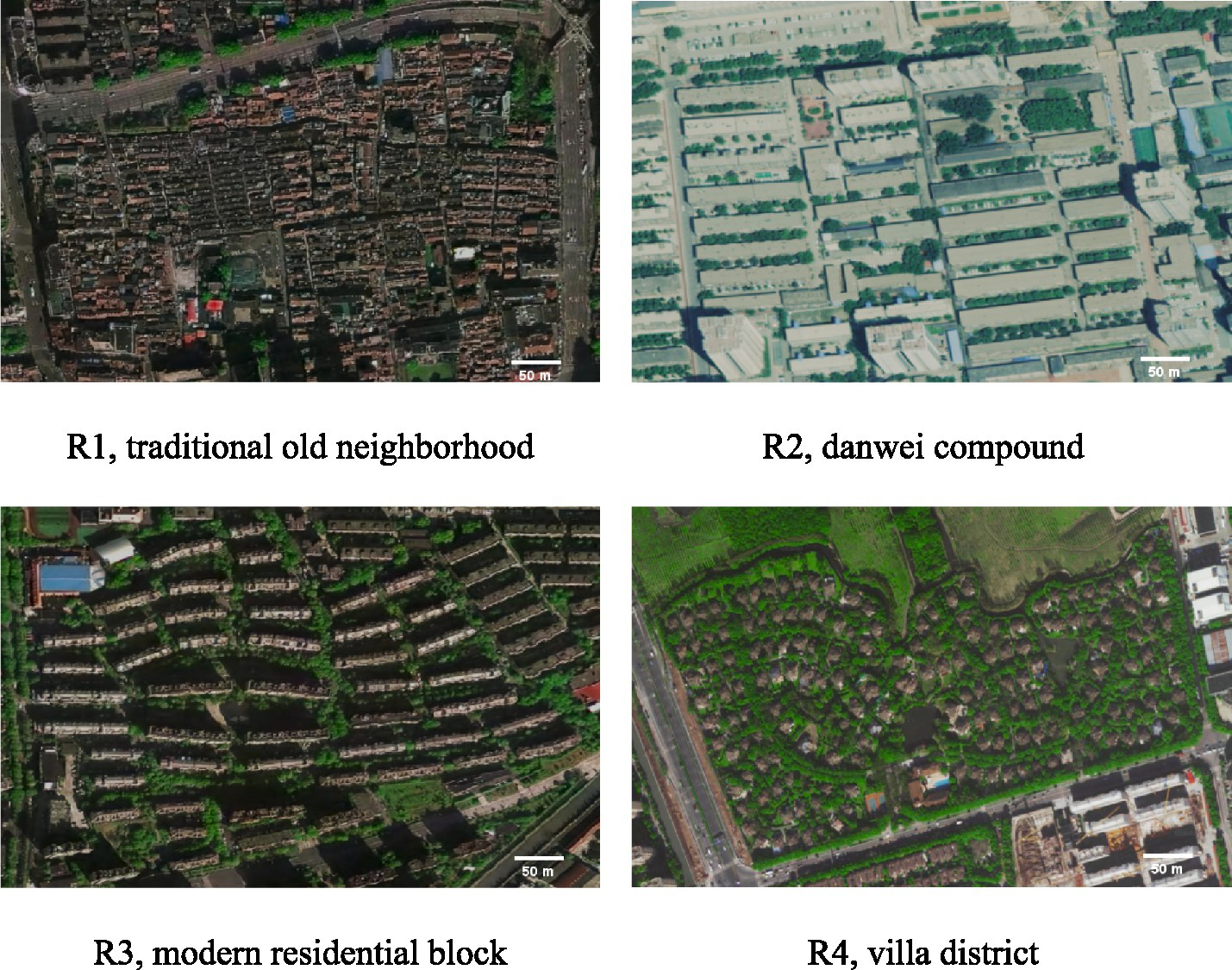

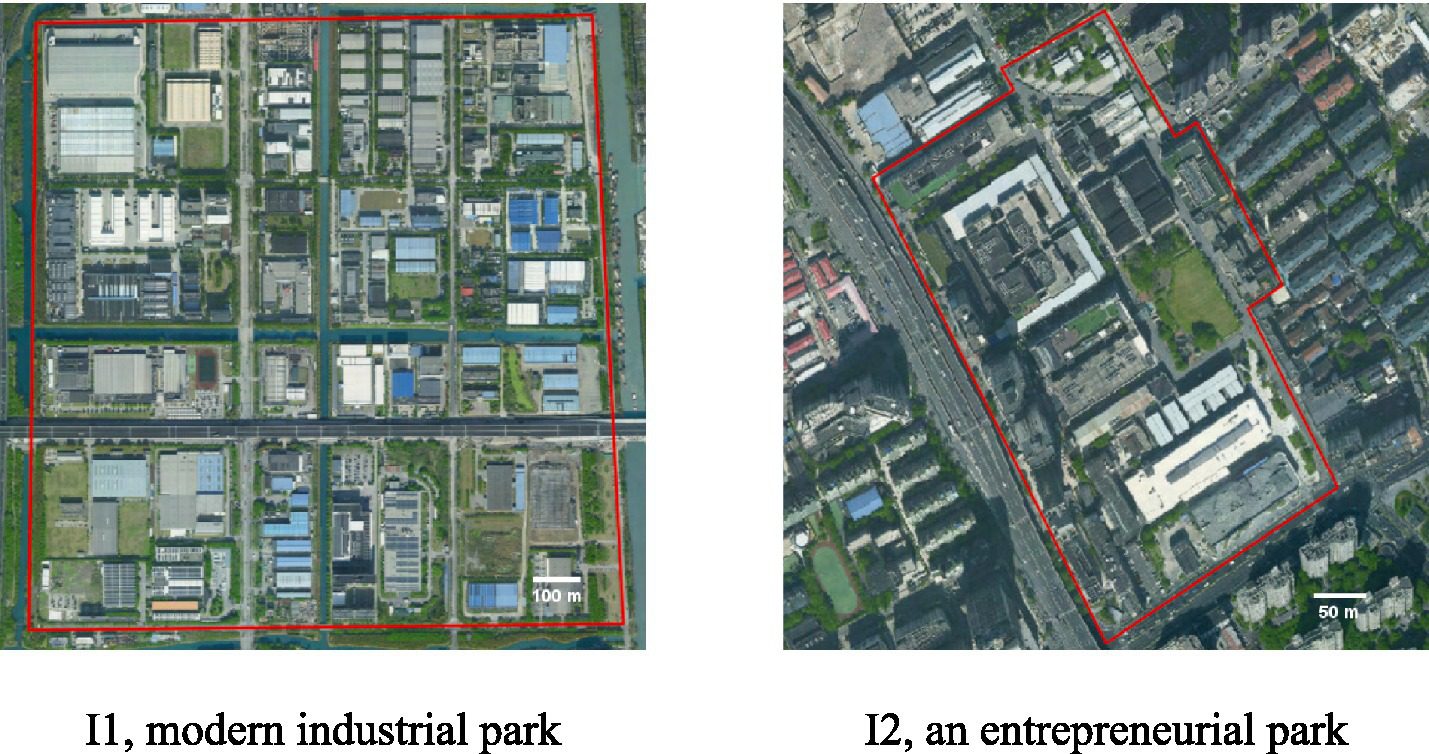

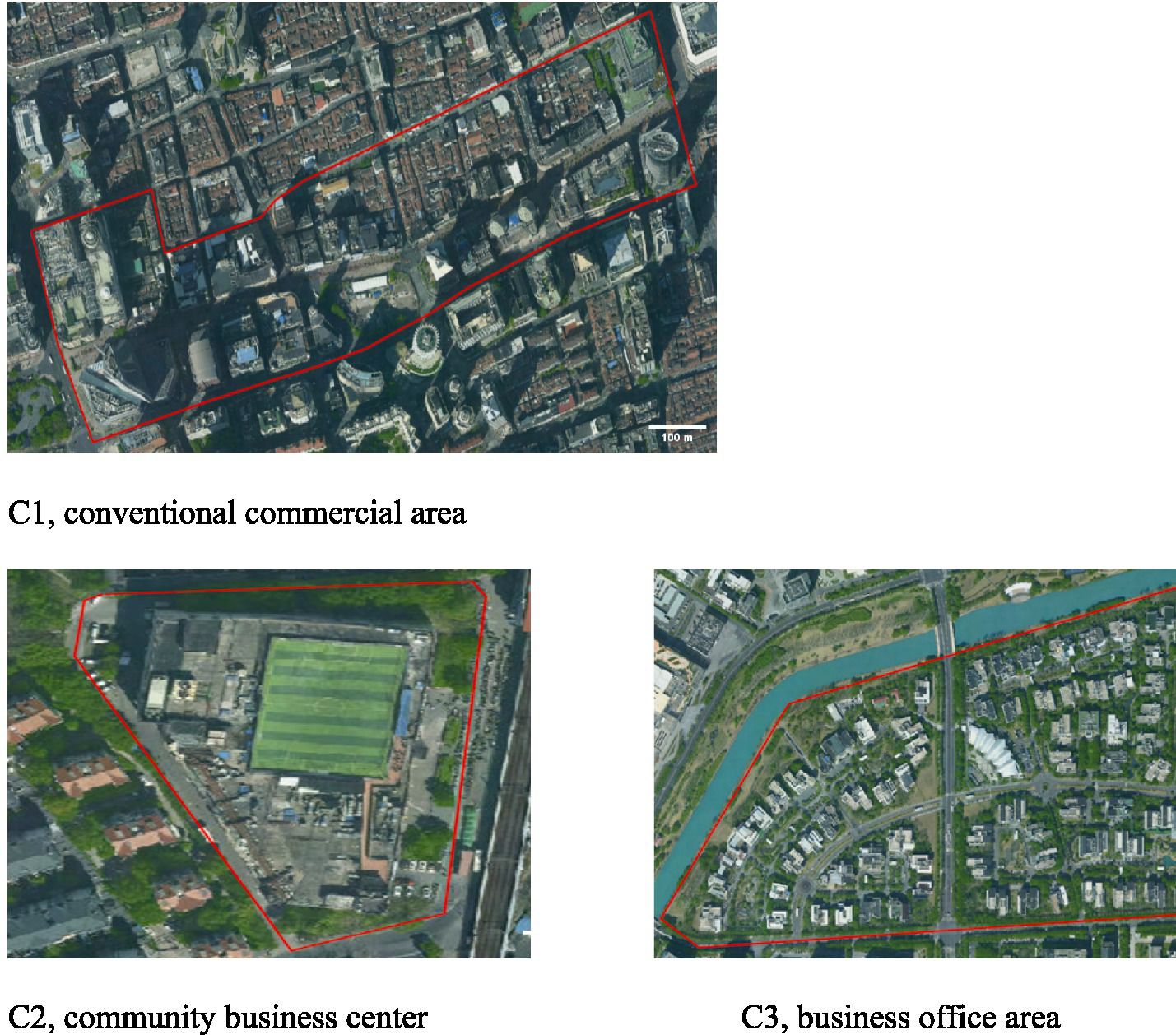

There are diverse frameworks for understanding the varied nature of urban areas in China and elsewhere (e.g., Jabareen, 2006; Wang et al., 2023; Zhu et al., 2024). We take our cue from the simple and familiar categories used in the landmark National Urban Runoff Program study launched in the late 1970s to investigate the sources, characteristics, and impacts of urban stormwater in the US, namely; residential (Figure 2); industrial (Figure 3); and commercial (Figure 4), thus providing the framework for examining how the SCI has been interpreted and implemented in each context. These are not supposed to be representative of all urban typologies in every Chinese city. To do so would surely be an overgeneralization. Rather, they are deliberately selected to frame the analysis in a way that enables meaningful comparison with urban forms likely familiar to the reader.

Figure 2

Aerial views of residential development examples. Sourced from Tianditu Map Service (2023).

Figure 3

Aerial views of industrial development examples. Sourced from Tianditu Map Service (2023).

Figure 4

Aerial views of business and commercial development examples. Sourced from Tianditu Map Service (2023).

3.1 Residential developments

3.1.1 Traditional historical residence

Traditional residential neighborhoods, like Beijing’s hutongs or Shanghai’s li-longs, are often located in flat, low-lying, city center areas. Many have faced demolition to make way for more modern development. Some have been preserved for their historic and cultural significance (Qian, 2007). These neighborhoods usually feature important landmarks such as ancient temples, towers, and places of historic events. Amidst the modern sprawl, they safeguard local traditions and evoke nostalgic memories of the city past.

3.1.2 Danwei compound

Work units (danwei, or 单位) were the main residence form when housing allocation was managed by state-owned enterprises or government agencies in pre-reform socialist Chinese cities. They are usually gated and walled plots that integrated workplaces, apartments, canteens, recreational centers, and more within the same precinct (Bray, 2005). Many of them were demolished following the bankruptcy of enterprises and to make way for new development. In those that remain, households are often encouraged to purchase their occupied dwellings to better align with economic reforms, albeit at a subsidized price. During the transition from public housing to a market-based provision (from around 1994), some housing was constructed and sold to workers at reduced prices as a form of welfare. In official documents, these pre-2000 residential blocks are generally considered old and deemed to be in need of renovation due to their ageing infrastructure.

3.1.3 Modern residential block

Rapid urban population growth is driving residential expansion towards suburbs (Feng et al., 2008). To accommodate more people, high-density, high-rise apartments (often seven stories or more) have become the most common form of current residential development in Chinese cities. Living conditions have greatly improved due to updated planning regulations and development standards, which encompass aspects such as green spaces, public areas, and drainage and these apartments are generally considered to be a desirable place to live.

3.1.4 High-end villa

Since the marketization of housing, high-end villa districts often labelled with ‘garden city’ or ‘eco-city’ began to gain popularity among more affluent individuals. These promise a more luxurious living experience with access to open space, privacy, and connection to ‘nature’ (Sun, 2015). Local governments initially welcomed the construction of these developments for financial gain and for their supposed environmental benefits. Growing concerns about the negative environmental impact of such developments, including land abuse and damage to natural ecosystems, has led many cities to strictly control the construction of this type of development more recently. Figure 2 shows a long-established traditional neighborhood (R1), a danwei-style compound constructed during 1990s (R2), a modern high-rising block developed in 2012 (R3), and a villa district constructed in 2006 (R4).

3.2 Industrial development

3.2.1 Modern industrial park

In recent years, rapid de-industrialization has been observed in many Chinese cities (Wei and Wang, 2019). While large, high-polluting factories were shut down or moved from the city, industrial development that integrates economic and advanced technical prowess has been encouraged by the state since the early 2000’s (Zheng et al., 2017). Compared with the fragmented spatial layout of traditional factories, these modern industrial parks are more integrated and planned with various high-tech industries strategically located in the same area.

3.2.2 Entrepreneurial park

Chinese cities have actively and sometimes aggressively explored the redevelopment of waste or abandoned industrial land since the 1990s (Liang and Wang, 2020). These lands are relatively scattered but often hold high land value. Two common approaches emerged: converting industrial land into residential areas or transforming old factories into cultural or entrepreneurial parks and revitalizing with new industries such as IT, performing arts, and e-commerce. The latter is often touted as a demonstration for what can be done to improve a city with an innovative urban regeneration program. Figure 3 depicts a modern industrial park developed around 2000 (I1), and an entrepreneurial park transformed from an abandoned textile factory around 2015 (I2).

3.3 Commercial and business development

3.3.1 Conventional large commercial districts

The reform and opening policy marked a dramatic shift in the nation’s economic landscape, as the growth of individual commerce outpaced that of state-run enterprises. This led to the rapid rise of retail business and then the proliferation of the service industry. Modern, large commercial areas, typically spanning over 50,000 square meters sprang up in downtown areas, often closely adjacent to traditional commercial streets. While these areas are vibrant urban hubs, they often now face challenges of stagnation and even decline due to evolving internet commerce models (Zhang et al., 2016).

3.3.2 Community business area

In line with the national promotion of the ‘15-min community life circle’ (MoHURD, 2018a, 2018b), community businesses serving the basic needs of residents have surged recently. Some began as small commercial outlets on ground floors, while others evolved into centralized independent systems occupying land areas smaller than 50,000 square meters. They often feature a box-style shopping mall serving as the main anchor, and various cultural and recreational facilities to attract nearby residents.

3.3.3 Business office area

From around the 1990s, a new type of business and commercial development known as “business office areas” or “商务办剬区,” characterized by a concentration of office buildings, began to emerge. Like modern industrial zones (often located in close proximity), these business office zones are planned systematically in suburban or rural areas. Figure 4 shows a large commercial area evolved from a historic commercial street dating back to the 1860s (C1), a community commercial center constructed around 2006 (C2), and a business office zone which became operational around 2012 (C3).

4 Exploring hydrosocial relations in the context of Sponge City Initiatives

Now that some of the common urban typologies have been introduced, this section turns to describe the implementation of the SCI in these areas as a tool for reimagining the city through place-making. The idea is to tease out the transformative potential of SCI with a focus on the local scale and place, and to consider the reworking and contestation of nature/society in the contemporary Chinese city.

4.1 Reimagining urban societies with SCI

4.1.1 The SCI in new greenfield suburban residential development

New greenfield development or, more commonly, complete reconstruction of urban areas that feature open space, abundant greenery, and well-maintained or newly planned drainage infrastructure, offer relatively favorable conditions for SCI nature-based infrastructure to be implemented (Figure 5). These areas closely resemble what is widely considered to be ‘the ideal site for envisioning sponge city’. It is ‘efficient’ to showcase ‘successful’ SCI landscapes in such developments. Thus, they are frequently designated as demonstration projects. When integrated as part of a regional initiative, they may have attractive names like ‘spongy towns’ or ‘eco-towns’ (e.g., Wubei spongy town in Pingxiang, Yuelai new city in Chongqing, Guian district in Guiyang, Ecological new district in Baicheng). A lot of SCI literature focuses on places like these, with an emphasis on describing how innovative technologies can be used to reduce runoff and achieve cost-effective transformation of the land in harmony with ‘nature’. It is a physical and economic imaginary of a more desirable socionatural future and in many ways mirrors that described in Western cities since the turn of the century.

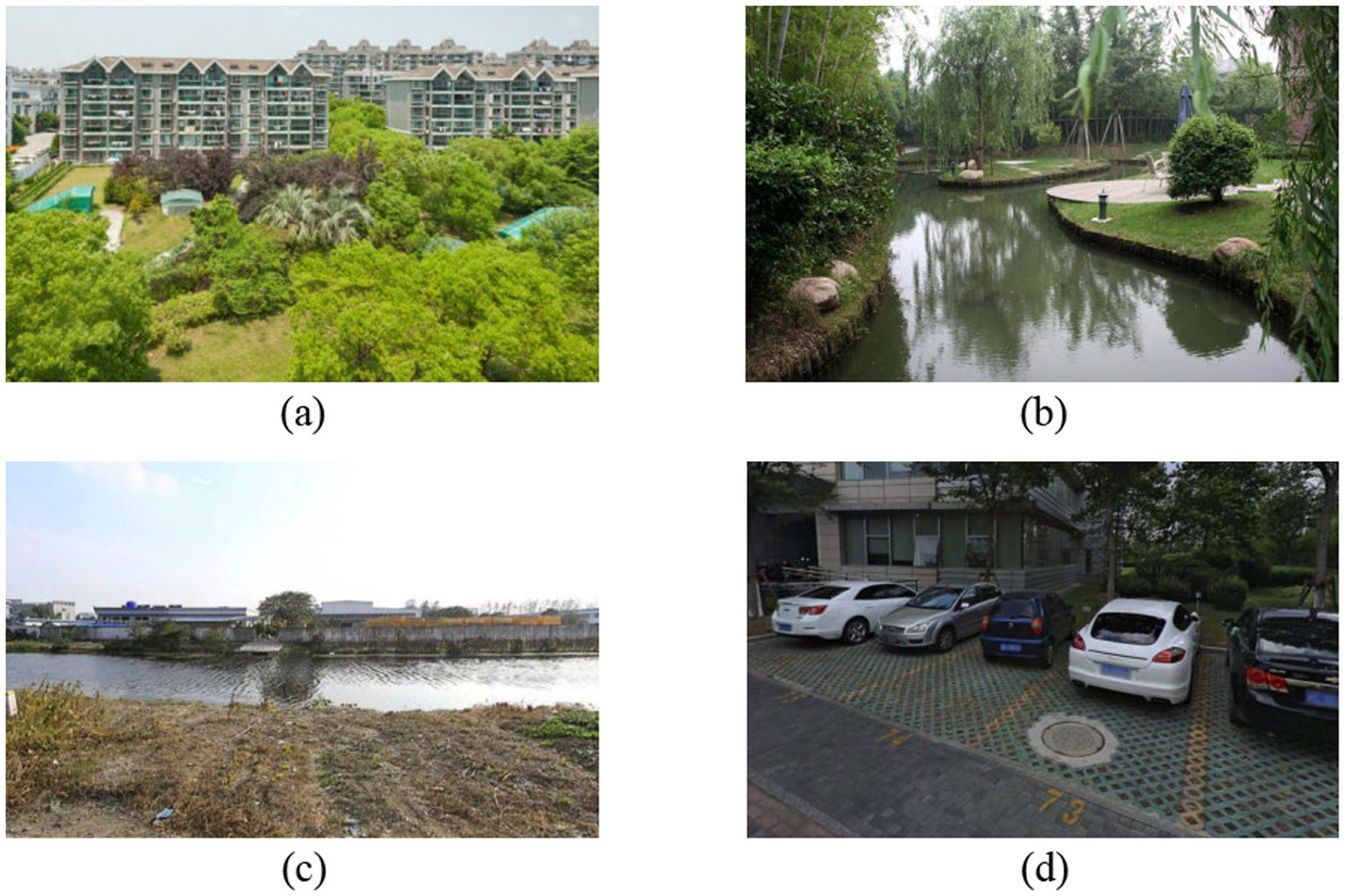

Figure 5

(a) Public garden in R3; (b) waterscape designed in R4; (c) riverside greenbelt in I1; (d) permeable pavement in C3 (a and b, sourced from real estate advertisements, c and d, taken by author).

The sociopolitical implications are quite different and often differ from city to city and place to place. In the modern blocks of R3, the SCI serves as an established regulatory tool that promises modern living standards including drainage and access to nature, albeit a sanitized, controlled and scripted nature. In R4, green assets and waterscapes are sold as exclusive, and provide access to a superior urban life for the lucky few. The development places a strong emphasis on privacy and differentiation from other parts of the city, and the area is strictly gated with each household separated from one another by walls, lawns, fences, and water features. This configuration reinforces the sense of separation, limiting interaction and shared experiences with other residents and especially onlookers who are largely excluded. Access to water/nature becomes a symbol of social status. The SCI in this context, much like critiques of eco-city developments, lean towards gentrification within a modernizing neoliberal logic (Mitchell et al., 2022).

4.1.2 The SCI in new industrial and business development

In newly developed industrial and business zones (such as I1 and C3), the SCI reflects the government’s commitment to green development, and their confidence in promoting economic growth with reduced environmental impacts. Situated far from the main city, these often gated, high-tech, scientifically managed places are constructed to show the strength of state and capital power and are primarily designed to attract ‘enterprises, industries, and talented individuals’, with a focus on boosting economic growth rather than providing public services.

The urban redevelopment example (I2) uses the SCI to support new ventures while encouraging public access. The government transformed the formerly enclosed industrial space into an entrepreneurial park with the aim to facilitate an economic transition away from heavy industry, and at the same time create borderless, dynamic, and lively public spaces through the use of green infrastructure (Figure 6a). On weekends the public areas become the backdrop for a variety of outdoor activities such as music performances and arts exhibitions, encouraging people to interact with water, nature, and each other. The development clearly serves a particular demographic and portrays a singular emancipatory construct of nature as a savior. Many of the green spaces are elevated higher than their surroundings to make green landscapes more prominent. This reduces their ability to capture stormwater, casting doubts on the extent to which the green infrastructure best serves water management. Moreover, the developments brand as a cutting-edge workplace for new technology enterprises comes with a futuristic, high-tech image. Artificial intelligence is proudly used to manage stormwater and public spaces (Figure 6b). This imbues a mechanized and automated vibe that perpetuates a sense of detachment and works to alienate those that do not feel comfortable in the techno-fetish environment. It is designed for young, dynamic, modern people. This is further reflected in the public activities held in the park that predominantly cater to the young, intelligent, and privileged.

Figure 6

Greenland and retention pond in I2 (a), robot working in the public space of I2 (b), taken by the author.

4.1.3 The SCI in historic residential areas

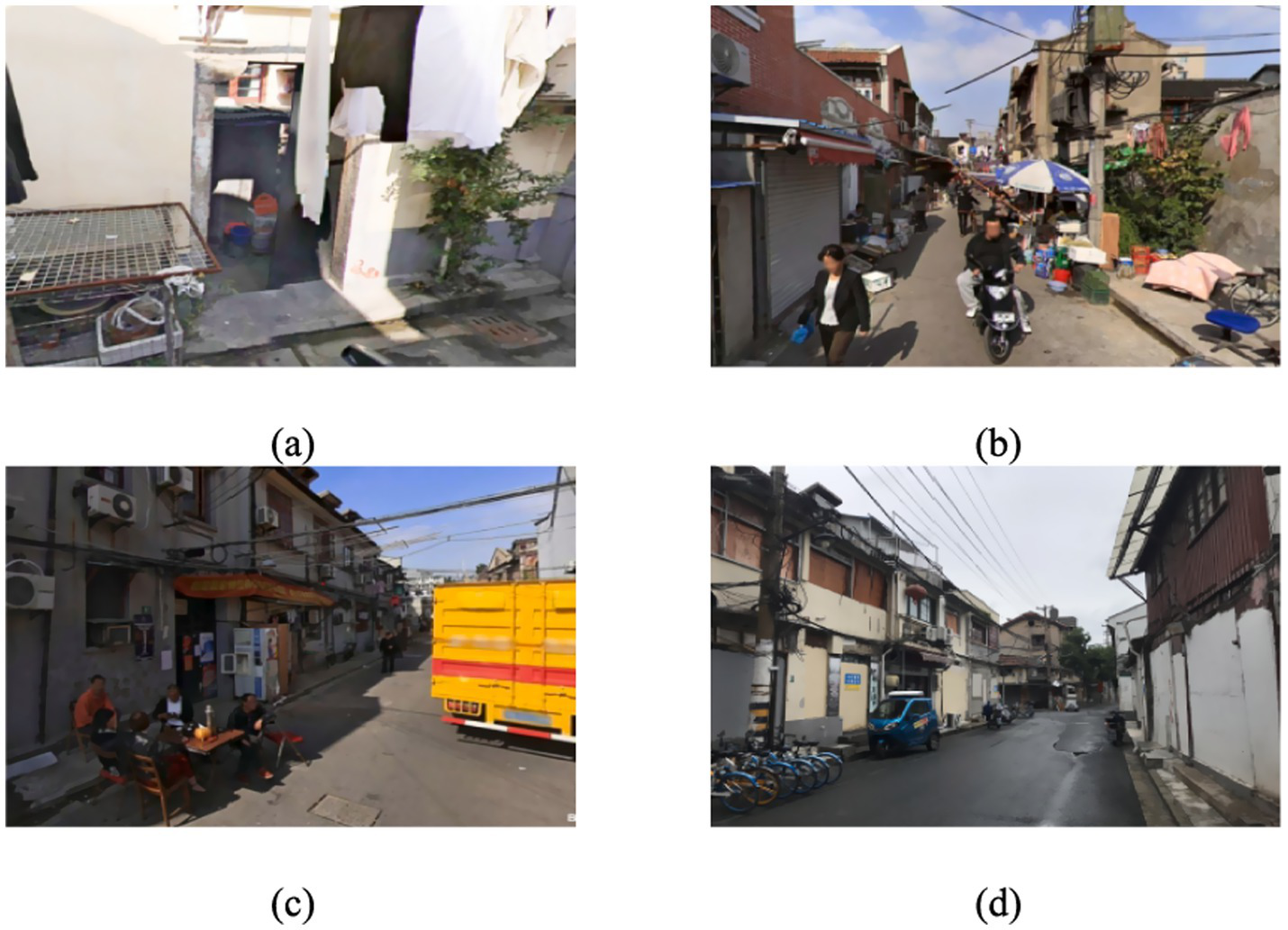

Historic neighborhoods in Chinese cities are typically characterized by high impervious surface and aging water infrastructure in an unknown or poor condition. This makes them prone to stormwater issues and they should be considered strong candidates for stormwater infrastructure upgrades. For example, R1 consists of densely packed historical buildings and narrow lanes (Figure 7). There is a fragmented, old and combined sewer-stormwater drainage systems. Roads are often more elevated than the ground floor of houses, generating risk from waterlogging and pipe overflows (R2, C1 and C2).

Figure 7

(a) Poor drainage and road design, noteworthy elevation gap inside and outside at a household’s gate; (b) encroachment of public space; (c) people socialize in the compacted space; (d) a street after relocation. Taken by the author.

Unlike the general optimistic outlook for the SCI in new or re-development area, implementing SCI in historic urban areas is often perceived to be problematic (Qiao et al., 2020). Frequently cited constraints in the technical literature include space limitations, poor environmental backgrounds, and complex existing infrastructure that complicate the efficiency of the SCI. There are also mentions of social constraints such opposition from residents and funding shortages (Che et al., 2015; Li et al., 2017; Ren et al., 2020). Consequently, upgrades to the historic neighborhoods tend to rely on grey infrastructure, as explicitly acknowledged by the national technical guidance on SCI. Where nature-based infrastructure is discussed and implemented, the reorganization of urban place becomes inevitable. Yet, discussion on the impact of such reorganization is conspicuously absent. Instead the discussion focusses on infrastructure and construction as a ‘game’ of balancing the ‘quantifiable risks and costs’ (Dong et al., 2017).

These historic areas present an urban fabric that does not easily align with SCI implementation. The residents in R1 have small per capita living areas (only around 6–10 m2). Everyday activities permeate public space, such as shared kitchens and bathrooms. Bicycles are parked casually around the development, and clothes are dried beside (and even spanning) the street. The ground floor of houses often constitute small stands or shops that spill out onto the streets.

This busy use of space blurs the boundaries between public and private, giving rise to numerous social hubs and bumping spaces that form organically, and are scattered throughout the community (Figures 7b,c). When walking through the old alleys, it is not uncommon to see residents’ efforts to infuse greenery into their living environment by placing plant boxes by the roadside, on balconies, and cultivating climbing plants on vertical walls. Despite the perceived lack of space, there are opportunities, desires, and efforts to be green that are intrinsic to place making in historic centers. All of these contribute to close-knit community relationships and cultures. There are unique sights, noises and smells that give the place its identity and an aura absent modern residential areas. These are the richness and vibrancy of an everyday lived community, that can be protected while improving drainage. However, the current tranche of SCI literature struggles to articulate with this way of knowing the urban. This is despite the familiar tone in the wider geography, landscape, and planning discussions that have long advocated for community development (e.g., Yifu Tuan, Jane Jacobs, Jan Gehl, to name a few). Engineering-based rational efficiency lacks the inclination and awareness to engage meaningfully with place. It does not articulate local histories, desires, and stories.

As a result, the SCI is often contested in such places. The SCI has not yet been implemented in the traditional development of R1, but its impending introduction, especially the adoption of nature-based solutions, is expected to lead to a radical reconfiguration of the area. This may include clearing out shared spaces and informal social hubs, and resident relocations to facilitate reconstruction of infrastructure and buildings, which happened in parts of R1 (Figure 7d). New and more ‘productive’ spaces replace traditional streetscapes. Even when tangible historical heritage is preserved, the loss of community cohesion and the authentic sense of community transforms old urban areas into ‘products with no souls’ (e.g., Hock, 2012). In this way, the SCI becomes a vehicle for the tragedy of modernity (Scott, 1998), a perspective that is clearly important when analyzing the changes in hydrosocial relations brought about by SCI.

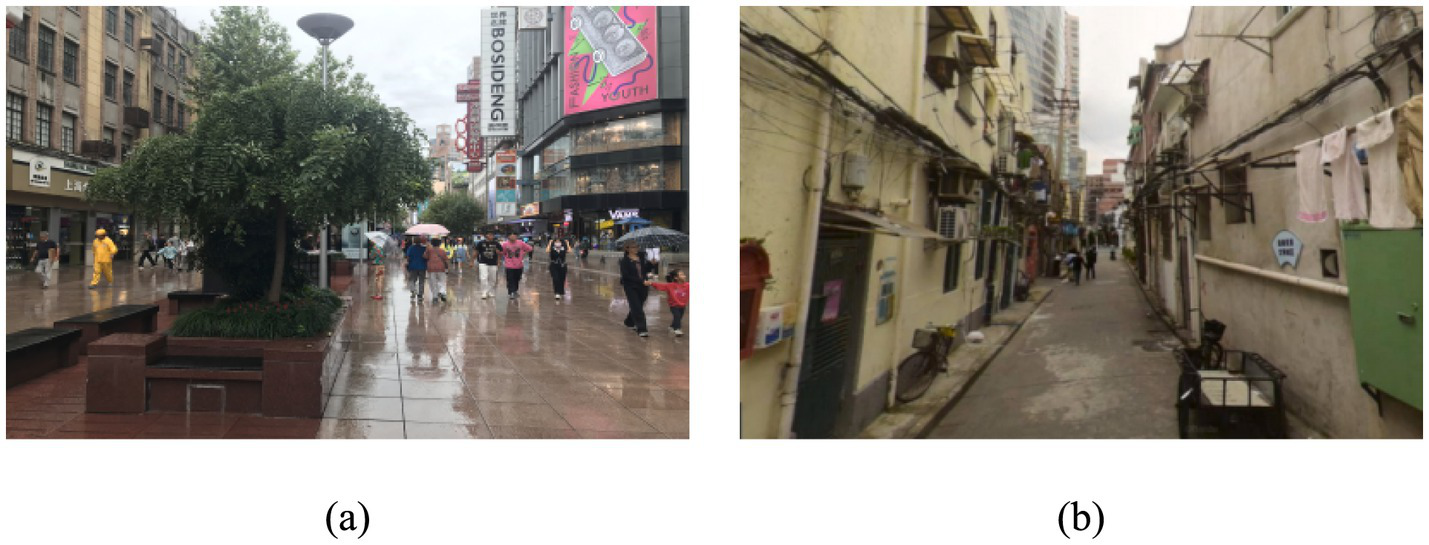

4.1.4 The SCI in commercial areas of renovation

An example of commercial renovation further illustrates the disruption of established social fabric after the SCI implementation. C2 had a box-style shopping mall along with a nearby fixed market nestled among several aging neighborhoods. The shopping mall incorporated a public square that used to be a lively social hub with a well-used newsstand and various mobile vendors ranging from food to clothing. The fixed market was a place for small businesses such as florists, second-hand stores, and pet shops. Residents nearby frequented this location to buy daily goods, eat together outside, take leisurely strolls around the square and the market, and would stop in front of those vendors, have conversation and exchange stories. It was an inclusive community full of interaction that promoted a sense of familiarity, cohesion and safety.

To address waterlogging and the runoff pollution resulting from the accumulation of rubbish and grease on ground surfaces (due to the congregation of vendors), C2 underwent extensive renovation including drainage systems retrofit and green cells construction in the name of SCI. This entailed the removal of the vendors to both enable the SCI design and, more importantly, to facilitate the transformation of the market into a ‘modern shopping mall’, and the conversion of the public square into a parking lot. The space became dedicated to efficient consumption, directing people to spend money indoors. People (and their consumption) were constructed as globalized individuals with little connection to the locality. It certainly became cleaner and more organized but the vibrant street life and sense of community was lost to make way for an ordered urban nature implicit in SCI modernization (Figure 8).

Figure 8

Before and after the renovation of C2. (a,b) show the front square of the old shopping mall cleared and repurposed as parking lots; (c,d) depict the bustling market street beside that has been reconstructed into a modern shopping mall. Taken by the author.

The SCI is interpreted in different ways in different places. What is clear from the descriptions is that the ‘progress’ of the SCI is not interpreted or supported the same way in different urban areas. Indeed, it is sometimes contested, as was the case in the historic neighborhoods. In other historic areas the story is different, and for different reasons. C1 encompasses a large-scale commercial street and a nearby historic neighborhood. This place is regarded as the city’s window into the past, representing its prestige and serving as a prominent tourist attraction and economic center (Figure 9a). Visible flooding or sewage overflow could result in significant economic losses and embarrassment for local authorities. Therefore, the drainage facilities of the main commercial street area undergo frequent inspection and maintenance. Stormwater infrastructure, such as rainwater harvesting and reuse systems along with real-time hydrologic monitoring systems have been installed throughout the place. In case of an emergency, the street takes priority for water pump allocation and the emergency response. Just behind the commercial zone, the neighboring traditional residential area grapples with poor drainage and living environment (Figure 9b). Retrofit of the local drainage systems started in August 2023, nearly a decade after SCI’ s initiation in the neighboring commercial area. This came with plans to demolish a significant portion of the neighborhood. The excuse being the difficulty of implementing SCI in an area with a perceived lack of space and the presence of complicated property rights. This clearly prompts discussion of the economic and political concerns of decision-makers, and how they intersect with issues of urban justice and place making. The current official assessment standards of SCI offer little in the way of prioritization for equality.

Figure 9

Stark contrast view between the main commercial street (a) and one of the backstreets in C1 (b) taken by the author.

The discussion above is not intended to diminish the value of SCI. Instead, the purpose is to draw attention to the importance of the SCI in creating place and reshaping people’s everyday lived experiences. Indeed, based on the examples that have been described, we posit that the SCI is perhaps more to do with place than it is to do with water. In a hopeful way the SCI can attract shared green spaces and support new communities to thrive in attractive and livable cities. But when framed as an efficient modernization tool, SCI can lead to an atomized society with little emotional connection to nature/community/place. In such cases, the SCI could be understood as an attempt to address the environmental crisis, while simultaneously promoting much that has led us there.

4.2 The implementation of SCI and the creation of place in Chinese cities

The Sponge City Initiative (SCI) is often portrayed as a clean, efficient, and modern pathway to urban and economic development, reflecting an eco-modernist faith in technological solutions. This framing echoes critiques in Western scholarship of large-scale urban environmental programmes, which suggest that such initiatives frequently rebrand conventional development logics under the rhetoric of innovation (Karvonen et al., 2014). More optimistic socio-environmental perspectives, however, emphasize the transformative potential of local politics and environmental democracy as means of realizing the deeper sustainability ambitions of these programmes (Karvonen, 2011; Stirling, 2015; Scoones, 2016). Following a brief discussion, our focus shifts to the everyday, small-‘p’ political dynamics that shape urban development practices within Chinese cities under the framework of the SCI.

Karvonen (2011) points out three necessary catalysts for such politics: new civic imaginaries that embrace the indelible connections between humans and nonhumans, a more modest expertise that includes local knowledge, and experiments aimed at catalyzing civic politics through discussion, debate, agenda setting, and action to realize new configurations of humans, nature, and technology in the city. The Chinese conversation differs significantly. Entering the post-socialist era, the state is deliberately seeking new forms of politics to improve administration efficacy while also filling the power vacuum left by the retreat of danwei compounds. A large number of Chinese studies focus on macro-scale national policy that deals with environmental challenges (e.g., He et al., 2012; Li, 2019). Those that discuss civil society often do so within the guise of inspecting the influence of emerging social forces such as neighborhood activism and non-governmental organizations that could rock the boat, so to speak (Douglass et al., 2007; Tang and Zhan, 2008; Martens, 2013).

In recent years, public participation in environmental issues has been translated into new organizational structures through laws and regulations (Johnson, 2020; Wu et al., 2020). The government encourages the use of social resources to strengthen community services and ‘solve’ community problems under the leadership of the Party (Derleth and Koldyk, 2004). Urban residents are arguably experiencing a gradual transition from previous ‘masses’, toward a more ‘citizen’ oriented identity aligned with western concepts of democracy. However, such a transition is being approached with caution due to the unique history, culture, and institutions of Chinese cities. Historical political movements, a deep-rooted sense of family rather than community (implying a possible focus on private good over broader social good), a longstanding reliance on state paternalism, as well as doubts regarding deliberative democracy, all contribute to the complexity of this shift (Heberer, 2009; Martens, 2013; Fu, 2019). In the context of SCI, it is important to consider how this green policy reflects these ways of thinking and navigates the complexities of the Chinese urban landscape. Does it tread a path of Western-style empowerment or chart a distinctive course?

4.3 The responsibility for SCI and the implications for local scale hydrosocial change

Chinese stormwater management has traditionally been the responsibility of the government supported by their own technical experts. The launch of SCI and promotion of small-scale, decentralized, nature-based infrastructure, aligns with the aforementioned political and narrative changes. These are now discussed in terms of emerging markets and communities.

There has been a growing push to transfer responsibility of the SCI to market-based stakeholders, such as drainage companies, e.g., in Shenzhen, specialized drainage companies began taking take over public drainage systems and property management firms. Additionally, public-private partnerships are encouraged to finance SCI (Nguyen et al., 2019). There are also examples of experiments in the trade of water rights that include rainwater (MoWR, 2022).

The community or shequ concept has been strengthened in recent decades. The establishment of the community residents’ committee and the homeowner association provide avenues for public engagement in community affairs, allowing residents to voice their concerns and collectively engage with the local government and technical experts on SCI (Liu and Zhou, 2008). The former is a grassroots mass-autonomous organization with responsibilities that may include reporting issues on behalf of residents and the negotiation of solutions with other entities. It is functionally designed to connect the government with the people, with many members designated by the government. The latter serves as the executive body representing and safeguarding interests of property owners.

Of course, there are place based differences in the market and the communities’ ability to be involved with SCI. In industrial, business, and commercial zones it is clear that enterprises, industries, and businesses embrace SCI for financial gains, such as benefiting from tax incentives and reducing production cost and risks (e.g., rainwater harvesting for cooling), enhancing the environment to attract employees and customers and to raise land prices through the process of distinctly Chinese gentrification. The wider public is either cast in the role of consumers or deliberately and physically excluded from these places. There are neither avenues nor incentives for the public to engage in SCI decision-making. For workers or office employees focused on prolonged indoors work, concern for rainwater and greenery outside becomes challenging when conflicts of interest with their employers may hinder their ability to voice opinions. Under the banner of neoliberalism, SCI is at times fostering artificially curated and largely isolated ‘green boxes’, with contestation of these ideas quietly swept under the carpet.

In residential areas the presumptive realm of popular participation becomes more evident. This largely hinges on local social capital and people-place relations (Wachsmuth and Angelo, 2018) which are deeply political in a small ‘p’ way. For example, in traditional communities like R1, residents are primarily low-income and often elderly individuals. Many areas have complex property rights and unclear area boundaries and are not managed by property management companies or homeowner’s associations. Residents struggle to have a collective voice with which to advocate for local needs and desires despite being relatively close-knit communities. Indeed, these needs and aspirations are often complex. On the one hand, the need to address structural problems such as poverty, housing difficulties, safety from flooding, hygiene problems is urgent. On the other hand, there is a strong emotional attachment to the locality, seen in those reluctant to relocate, and frequently through shared histories and experiences. However, the latter is downplayed in the SCI discourse, which preemptively frames the change as a choice between modernity and persisting in poverty and poor living conditions. This is a common narrative used by local authorities to promote and persuade residents to accept a SCI modernization program. It captures the longstanding consensus among the Chinese populace regarding their interdependence with the state, their shared strength and prosperity, and their eagerness for growth. Consequently, local resistance against the potential erosion of community and identity is often weak.

4.4 The understanding of the SCI in the rise of more exclusive residential areas

In modern, luxurious and more exclusive residential areas like R3 and R4, stormwater systems and public space management is often under the control of property management companies. Residents’ income and educational level are generally high. Financial security supports the ability to negotiate for favorable terms and conditions (investment) of state funds in local infrastructure. Yet these areas often exist in a state of enclosure, characterized by largely homogenous family scale relationships rather than wider community building. This significantly curtails the diversity of perspectives and experiences, restricting residents’ capacity to envision a more equitable city. This is especially the case where residents prioritize high-end living experiences and land prices, and their attention is diverted from pressing global and local environmental crisis. The overreliance on property management companies also reduces the need for residents to personally address water issues. This can perpetuate a disconnect from everyday water-nature, hindering the negotiation of desirable hydrosocial relations.

4.5 More promising understanding of the SCI elsewhere

There are more promising signs that the SCI has increased the connections between people-water. In I2, an effort is made to cultivate civic awareness and promote a more cooperative framework for water management that speaks to local desires. The open-access park was planned as a campus-style neighborhood catering to entrepreneurs, workers, nearby residents, and visitors. The local authority endeavored to create a governance mechanism for collaboration, participation, and shared benefits—共商共建共治共享. Such language is notably used by the central government in the context of global governance. The shared benefits are in public spaces like parks that are used by enterprises and the nearby residents. A service center was established to offer a space for people who work or live nearby to communicate various park-related matters, such as organizing public events, community well-being, and entrepreneurship. However, it is still uncertain how this influences the SCI and whether ‘benefits’ are for all. It is worth remembering that this is a high-tech and rather exclusive local area that implicitly excludes many people.

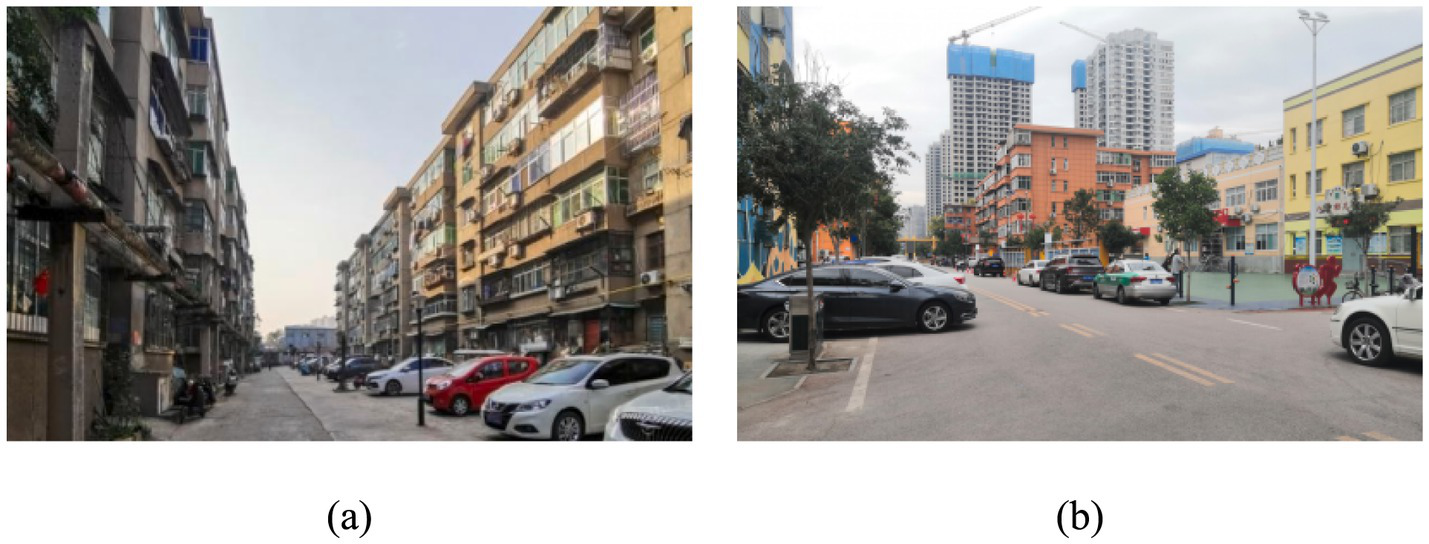

4.6 The SCI in areas with a Chinese style deliberative democracy

The development example in R2 provides a prominent example of Chinese-style deliberative democracy. This is home to workers and their families from an old, state-owned enterprise (SOE) factory. It presents a unique opportunity to advocate for local desires and needs. The residents here share close community relationships, facilitated by their shared workplace and social status which empowers the homeowner’s association and the residents’ committee to unite their voices. The long-term ties between the factory and the local government provide a strong social and political network, allowing decision-makers who do not live locally to better understand socioenvironmental desires. In 2019, the residents successfully requested the inclusion of their locality in a renovation plan for more green public services. SCI was used to update drainage systems and develop other nature-based infrastructure. On the back of this, public facilities for recreation, fitness, socialization, and welfare were created. For example, a disused factory building was retrofitted into a kindergarten and a permeable exercise plaza (Figure 10). Despite a predominant top-down SCI paradigm, there are new forms of politics shaping the development of urban place in this area of the Chinese city.

Figure 10

R2 before (a) and after (b) renovation, taken by the author.

4.7 Overview of the Chinese city and the working of the SCI

The analysis demonstrates that the Sponge City Initiative (SCI) and its nature-based solutions challenge conventional models of urban development. By transforming ‘invisible’ water infrastructure into visible and tangible features of the urban landscape, the SCI creates new opportunities for embedding water and its management into everyday life. As Gandy (2014) suggests, infrastructures are not merely technical systems but constitutive elements of urban metabolism. In this sense, the SCI does more than manage runoff: it reorganises urban space and becomes woven into the socio-ecological fabric of the city, shaping and being shaped by human activities, meanings, and identities (Friedmann, 2010). In short, the SCI redefines place.

Emerging applications of hydrosocial concepts in China have explored narratives of large-scale hydroengineering projects, i.e., dams and hydropower (Geheb and Suhardiman, 2019), agricultural development (Clarke-Sather, 2016), and groundwater use (Hoogesteger and Wester, 2015). Of the few that have considered urban water, Cai (2017) posits that the SCI at the local level can become skewed towards pro-growth policy, which contradicts the initial intention of promoting resilience. Tang (2022) points out that the implementation of SCI goes beyond the simplistic notion of greenwashing and eco-modernization, instead being influenced by complex techno-politics of development trajectories, governance, and different epistemologies of blue-green infrastructure. Aligning to our way of thinking, the blue-green infrastructure in this case is seen as an active agent rather than a passive, apolitical instrument that shapes policies, politics, and urban development of Chinese Sponge Cities in different ways in different places.

The wider critical literature usually portrays major Chinese green initiatives (e.g., eco-city, low carbon city) as concerned with accumulating capital, reinforcing modernization of urban governance, and providing opportunities for increased state control, while not paying enough attention to local, social and cultural contexts (Caprotti et al., 2015; Sze, 2015; Xie et al., 2019; Curran and Tyfield, 2020; Harlan, 2021). Notably, most examine green initiatives in areas of new urban development as this is where most eco-projects are realized, with particular attention given to the high-level institutions and political actors (e.g., Rogers and Crow in Miller 2017). The official discourse on the SCI specifically points to both new and old urban areas. According to the Council (2015), ‘…new urban areas, various types of parks and piecemeal development zones should fully implement the requirements for sponge city construction. Old urban areas should combine with the renovation of urban shantytowns and dangerous housing, organic renewal of old neighborhoods…’ This differentiates SCI from other green initiatives, as the incorporation of ‘old’ urban areas implies interaction with existing urban fabrics and more complex physical-social realities. It therefore demands greater attention to the local scale.

This paper has examined local-scale hydrosocial relationships across diverse Chinese urban typologies, showing how the Sponge City Initiative (SCI) is enacted in uneven and often contradictory ways. In some places, the SCI is mobilised to promote business, growth, and elite forms of urban living, while in others it is contested by communities seeking to preserve local histories and cultural attachments. These dynamics reveal that the SCI is not a singular technical programme but a deeply political process, one that simultaneously enables inclusion and drives exclusion. Place, therefore, emerges as a critical lens for understanding how environmental policy is reshaping urban life in contemporary China.

5 Conclusion

This paper has examined the Sponge City Initiative (SCI) through the lens of place-making in Chinese cities, showing how nature–society relations are contested and constructed at the local scale. Our analysis highlights that the SCI is far from a uniform technical exercise: it manifests differently across urban contexts, empowering markets and capital in some cases while opening space for communities to assert historical, cultural, or socialist legacies in others. Exclusive, high-end developments have been able to leverage SCI investments to reinforce gentrified and gated forms of urbanism, yet there are also examples where residents have mobilized collective voices to contest or reshape SCI implementation. These contrasts reveal the SCI as a nuanced and variegated policy, deeply political in its local enactments. A place-based framework is therefore essential for understanding how environmental policies reshape urban life, and for discerning whether the SCI enables inclusive environmental values or primarily serves the imperatives of modernization. At present, the evidence suggests the SCI is tilting toward the latter, risking the production of more fragmented, exclusionary, and commodified urban natures unless greater attention is given to the politics of place. What is clear is that the Sponge City Initiative is less a neutral technology of urban sustainability and resilience than a political project whose outcomes are determined by the local contested politics of place.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

YZ: Methodology, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. ST: Writing – original draft, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by China Scholarship Council (201908420296).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Boelens R. (2014). Cultural politics and the hydrosocial cycle: water, power and identity in the Andean highlands. Geoforum57, 234–247. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2013.02.008

2

Boelens R. Hoogesteger J. Swyngedouw E. Vos J. Wester P. (2016). Hydrosocial territories: a political ecology perspective. Water Int.41, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/02508060.2016.1134898

3

Bray D. (2005). Social space and governance in urban China: the danwei system from origins to reform: Stanford University Press.

4

Cai H. (2017). Decoding Sponge City in Shenzhen: Resilience program or growth policy?Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

5

Caprotti F. Springer C. Harmer N. (2015). ‘Eco’For whom? Envisioning eco-urbanism in the Sino-Singapore Tianjin eco-city, China. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res.39, 495–517. doi: 10.1111/1468-2427.12233

6

Castree N. (2001). “Socializing nature: theory, practice, and politics” in Social nature: Theory, practice, and politics, Blackwell Publishers. 1–21.

7

Chan F. K. S. Griffiths J. A. Higgitt D. Xu S. Zhu F. Tang Y.-T. et al . (2018). “Sponge City” in China—a breakthrough of planning and flood risk management in the urban context. Land Use Policy76, 772–778. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.03.005

8

Che W. Zhao Y. Li J . (2015). Considerations and discussions about sponge city. South Archit.4, 104–107.

9

Clarke-Sather A. (2016). “Hydrosocial governance and agricultural development in semi-arid Northwest China” in Negotiating water governance. eds. NormanE. S.CookC. (Routledge), 247–262.

10

Council (2015) Guiding Opinions of The General Office of the State Council on promoting the construction of sponge cities (国务院办剬厅关于推进海绵城市建设的指导意见)

11

Curran D. Tyfield D. (2020). Low-carbon transition as vehicle of new inequalities? Risk-class, the Chinese middle-class and the moral economy of misrecognition. Theory Cult. Soc.37, 131–156. doi: 10.1177/0263276419869438

12

Derleth J. Koldyk D. R. (2004). The shequ experiment: grassroots political reform in urban China. J. Contemp. China13, 747–777. doi: 10.1080/1067056042000281473

13

Dong X. Ho K. C. Ooi G. L. (Eds.). (2017). Enhancing future resilience in urban drainage system: green versus grey infrastructure. Water Res.124, 280–289. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2017.07.038,

14

Douglass M. Guo H. Zeng S. . (2007). “Globalization, the city and civil society in Pacific Asia” in Globalization, the City and civil Society in Pacific Asia (1st ed.) (Routledge), 19–44. doi: 10.4324/9780203939383

15

Elliott A. Trowsdale S. A. (2007). A review of models for low impact urban stormwater drainage. Environ. Model. Softw.22, 394–405. doi: 10.1016/j.envsoft.2005.12.005

16

Feng J. Zhou Y. Wu F. (2008). New trends of suburbanization in Beijing since 1990: from government-led to market-oriented. Reg. Stud.42, 83–99. doi: 10.1080/00343400701654160

17

Fletcher T. D. Shuster W. Hunt W. F. Ashley R. Butler D. Arthur S. et al . (2015). SUDS, LID, BMPs, WSUD and more–the evolution and application of terminology surrounding urban drainage. Urban Water J.12, 525–542. doi: 10.1080/1573062X.2014.916314

18

Friedmann J. (2010). Place and place-making in cities: a global perspective. Plan. Theory Pract.11, 149–165. doi: 10.1080/14649351003759573

19

Fu Q. (2019). How does the neighborhood inform activism? Civic engagement in urban transformation. J. Environ. Psychol.63, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2019.03.002

20

Gahegan M. (2023) From reproducible to explainable GIScience (short paper). In BeechamR.LongJ. A.SmithD.ZhaoQ.WiseS. (Eds.), 12th international conference on geographic information science (GIScience 2023)

21

Gandy M. (2014). The fabric of space: water, modernity, and the urban imagination: MIT Press.

22

Geheb K. Suhardiman D. (2019). The political ecology of hydropower in the Mekong River basin. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain.37, 8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2019.02.001

23

Hansen M. H. Li H. Svarverud R. (2018). Ecological civilization: interpreting the Chinese past, projecting the global future. Glob. Environ. Change53, 195–203. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2018.09.014

24

Haraway D. (1988). Situated knowledges: the science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Feminist Stud.14, 575–599. doi: 10.2307/3178066

25

Harlan T. (2021). Green development or greenwashing? A political ecology perspective on China’s green belt and road. Eurasian Geogr. Econ.62, 202–226. doi: 10.1080/15387216.2020.1795700

26

He G. Lu Y. Mol A. P. J. Beckers T. (2012). Changes and challenges: China's environmental management in transition. Environ. Dev.3, 25–38. doi: 10.1016/j.envdev.2012.05.005

27

Heberer T. (2009). Evolvement of citizenship in urban China or authoritarian communitarianism? Neighborhood development, community participation, and autonomy. J. Contemp. China18, 491–515. doi: 10.1080/10670560903033786

28

Hock D. (2012). Autobiography of a Restless Mind: Reflections on the Human Condition Volume 1. Bloomington, IN: iUniverse.

29

Hoogesteger J. Wester P. (2015). Intensive groundwater use and (in) equity: processes and governance challenges. Environ. Sci. Pol.51, 117–124. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2015.04.004

30

Jabareen Y. R. (2006). Sustainable urban forms: their typologies, models, and concepts. J. Plann. Educ. Res.26, 38–52. doi: 10.1177/0739456X05285119

31

Jinguang L. (2013). The tolerance and harmony of Chinese religion in the age of globalization. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci.77, 205–209. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.03.079

32

Johnson T. (2020). Public participation in China's EIA process and the regulation of environmental disputes. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev.81:106359. doi: 10.1016/j.eiar.2019.106359

33

Karvonen A. (2011). Politics of urban runoff: Nature, technology, and the sustainable city: MIT Press.

34

Karvonen A. et al . (2014). “The politics of urban experiments: radical change or business as usual?” in After sustainable cities? (Routledge), 116–127.

35

Larner W. (2014). “The limits of post-politics: rethinking radical social enterprise” in The post-political and its discontents: Spaces of depoliticisation, spectres of radical politics, eds. WilsonJ.SwyngedouwE. (Edinburgh University Press) 189–207.

36

Li Y. (2019). Bureaucracies count: environmental governance through goal-setting and mandate-making in contemporary China. Environ. Sociol.5, 12–22. doi: 10.1080/23251042.2018.1492662

37

Li H. Ding L. Ren M. Li C. Wang H. (2017). Sponge city construction in China: a survey of the challenges and opportunities. Water9:594. doi: 10.3390/w9090594

38

Liang S. Wang Q. (2020). Cultural and creative industries and urban (re) development in China. J. Plann. Lit.35, 54–70. doi: 10.1177/0885412219898290

39

Linton J. Budds J. (2014). The hydrosocial cycle: defining and mobilizing a relational-dialectical approach to water. Geoforum57, 170–180. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2013.10.008

40

Liu X. Zhou Y. (2008). A study on housing problems of migrant workers for new modern industrial city-Exemplified by Suzhou city. Proceedings of criocm 2008 international research symposium on advances of construction management and real estate. eds. FengC. C.YuM. X.ZhaoZ. Y.125–131.

41

Martens S. (2013). “Public participation with Chinese characteristics: citizen consumers in China's environmental management” in Environmental governance in China. eds. CarterN.MolP. J. (Routledge), 63–82.

42

Mitchell G. Chan F. K. S. Chen W. Y. Thadani D. R. Robinson G. M. Wang Z. et al . (2022). Can green city branding support China's Sponge City Programme?Blue Green Syst.4, 24–44. doi: 10.2166/bgs.2022.005

43

MoHURD (2014). National Technical Guidance for Sponge City construction (trial). China’s Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development (MOHURD).

44

MoHURD (2018a). Assessment standards for sponge city construction effects: China building industry Press.

45

MoHURD (2018b). National Standard of Planning and Designing Urban Residential Neighborhoods (GB50180-2018). China’s Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development (MOHURD).

46

MoWR (2022). Guidance on promoting water rights trade reform. China’s Ministry of Water Resources.

47

Nguyen T. T. Ngo H. H. Guo W. Wang X. C. Ren N. Li G. et al . (2019). Implementation of a specific urban water management-Sponge City. Sci. Total Environ.652, 147–162. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.10.168,

48

Qiao X. J. Liao K. H. Randrup T. B. (2020). Sustainable stormwater management: A qualitative case study of the Sponge Cities initiative in China. Sustainable Cities and Society.53:101963.

49

Qian Z. (2007). Historic district conservation in China: assessment and prospects. Trad. Dwell. Settlem. Rev.2007, 59–76.

50

Ren N. et al . (2020). Paradigm of sponge city construction based on regional classification (海绵城市的地区分类建设范式). Environ. Eng.38.

51

Scoones I. (2016). The politics of sustainability and development. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour.41, 293–319. doi: 10.1146/annurev-environ-110615-090039

52

Scott J. C. (1998). Seeing like a state: How certain schemes to improve the human condition have failed: Yale University Press.

53

Sofoulis Z. (2011). Skirting complexity: the retarding quest for the average water user. Continuum25, 795–810. doi: 10.1080/10304312.2011.617874

54

Stirling A. (2015). “Emancipating transformations: from controlling ‘the transition'to culturing plural radical progress 1” in The politics of green transformations (Routledge), 54–67.

55

Sun X. (2015). Selective enforcement of land regulations: why large-scale violators succeed. China J.74, 66–90.

56

Swyngedouw E. (1996). The city as a hybrid: on nature, society and cyborg urbanization. Capit. Nat. Social.7, 65–80. doi: 10.1080/10455759609358679

57

Swyngedouw E. (2004). “Scaled geographies: nature, place, and the politics of scale” in Scale and geographic inquiry: Nature, society, and method, Blackwell Publishing. 129–153.

58

Swyngedouw E. (2009). The political economy and political ecology of the hydro-social cycle. J. Contemp. Water Res. Educ.142, 56–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1936-704X.2009.00054.x

59

Swyngedouw E. (2010). “Impossible sustainability and the post-political condition” in Making strategies in spatial planning: Knowledge and values, 185–205.

60

Sze J. (2015). Fantasy islands: Chinese dreams and ecological fears in an age of climate crisis: University of California Press.

61

Tang D. (2022). Infrastructural landscapes: The Technopolitics of watershed planning in Asia: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

62

Tang S.-Y. Zhan X. (2008). Civic environmental NGOs, civil society, and democratisation in China. J. Dev. Stud.44, 425–448. doi: 10.1080/00220380701848541

63

Tianditu Map Service (2023). National Administration of Surveying, Mapping and Geoinformation of China. Available online at: https://map.tianditu.gov.cn

64

Trowsdale S. Boyle K. Baker T. (2020). Politics, water management and infrastructure. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci.378:20190208. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2019.0208,

65

Tuan Y.-F. (1979). “Space and place: humanistic perspective” in Philosophy in geography. eds. GaleS.OlssonG. (Springer), 387–427.

66

Wachsmuth D. Angelo H. (2018). Green and gray: new ideologies of nature in urban sustainability policy. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr.108, 1038–1056. doi: 10.1080/24694452.2017.1417819

67

Wainwright J. Barnes T. J. (2009). Nature, economy, and the space—place distinction. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space27, 966–986. doi: 10.1068/d7707

68

Wang D. Dai R. Luo Z. Wang Y. (2023). Urgency, feasibility, synergy, and typology: a framework for identifying priority of urban green infrastructure intervention in sustainable urban renewal. Sustainability15:10217. doi: 10.3390/su151310217

69

Wei H. Wang S. (2019). Phenomenon analysis and theoretical reflection of China’s ‘over De-industrialization’. China Indust. Econ.1, 5–22.

70

Wesselink A. Kooy M. Warner J. (2017). Socio-hydrology and hydrosocial analysis: toward dialogues across disciplines. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Water4:e1196. doi: 10.1002/wat2.1196,

71

Wu L. Ma T. Bian Y. Li S. Yi Z . (2020). Improvement of regional environmental quality: government environmental governance and public participation. Sci. Total Environ.717:137265.

72

Xie L. J. Flynn M. Tan-Mullins Y. Cheshmehzangi A . (2019). The making and remaking of ecological space in China: the political ecology of Chongming Eco-Island. Polit. Geogr.69, 89–102.

73

Zhang D. Zhu P. Ye Y. (2016). The effects of e-commerce on the demand for commercial real estate. Cities51, 106–120. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2015.11.012

74

Zheng S. Sun W. Wu J. Kahn M. E. (2017). The birth of edge cities in China: measuring the effects of industrial parks policy. J. Urban Econ.100, 80–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jue.2017.05.002

75

Zhu X. Guan Y. K. Ho P. P. (2024). Place-making of “new nostalgic space” in urban development: the case of lane 1192 in China. Geoforum150:103988. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2024.103988

Summary

Keywords

Sponge City Initiative, green infrastructure, urban water management, sustainable urban development, Hydrosocial analysis, place-based politics

Citation

Zhao Y and Trowsdale S (2025) The many faces of China’s Sponge City Initiative. Front. Sustain. Cities 7:1688283. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2025.1688283

Received

18 August 2025

Revised

13 November 2025

Accepted

18 November 2025

Published

16 December 2025

Volume

7 - 2025

Edited by

Nishant Raj Kapoor, Academy of Scientific and Innovative Research (AcSIR), India

Reviewed by

Anant Mishra, Birla Institute of Technology and Science, India

Afrah Al-Shukaili, Sultan Qaboos University, Oman

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Zhao and Trowsdale.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sam Trowsdale, s.trowsdale@auckland.ac.nz

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.