Abstract

The “leaving no one behind” principle of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) acknowledges inclusion of marginalized and vulnerable groups (MVGs) in all spheres. A methodological gap often hinders adequate execution, frequently lacking community engagement in prioritization of MVGs to facilitate inclusion. To bridge this gap, researchers employed a qualitative, two-pronged approach that involved social mapping and participatory focus group discussions (FGDs) in two informal settlements in Nairobi, Kenya. The study identified, characterized and ranked MVGs including persons with disabilities, child-headed households, older persons, and refugees. It also pinpointed three main root causes of their vulnerability and marginality: deferential (referring to status), economic/livelihood, and social factors. Key challenges faced by these groups included limited access to basic amenities, restricted political representation, unemployment and barriers to information access among others. Addressing challenges of MVGs requires a multi-pronged strategy that includes identifying and prioritizing these groups regularly and understanding the root causes of their marginalization. Regular social mapping and the active participation of MVGs are crucial for developing inclusive policies and programs to achieve social justice and wellbeing in line with the SDGs' “leaving no one behind” principle within the urbanization sector.

1 Introduction

The global commitment to “leave nobody behind” (LNB) within the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) necessitates a focused effort to reduce inequalities that lead to exclusion and limit human potential (Kamalipour, 2019; Long et al., 2023). Discrimination is a key driver of this exclusion, resulting in the marginalization and vulnerability of individuals and groups (Varghese and Kumar, 2022). Marginality refers to social exclusion and discrimination faced by specific groups, whereas vulnerability encompasses broader susceptibility to harm from various factors (Kenya Ministry of Education, 2017; Browne, 2015). Vulnerability, characterized by heightened susceptibility to harm from everyday challenges (Kenya Ministry of Education, 2017; Browne, 2015), often stems from factors like age, ethnicity, gender, disability, socioeconomic status, and can restrict access to essential support and development benefits (Kenya Ministry of Education, 2017; Sepúlveda and Nyst, 2012). A significant underlying cause of vulnerability is marginalization (Williams et al., 2019). A process that pushes the specific groups to the periphery of societal systems (economic, cultural, political, social), resulting in depreciations and disadvantages (Varghese and Kumar, 2022; Williams et al., 2019).

The intersection of vulnerability and marginalization in specific contexts severely hinders access to basic resources and full societal participation (Joseph et al., 2023). These demand thorough investigation and targeted solutions (Varghese and Kumar, 2022; Joseph et al., 2023), particularly in settings like informal settlements where existing vulnerabilities are often amplified (Varghese and Kumar, 2022; Joseph et al., 2023). This study seeks to address the gap in understanding and prioritizing marginalized and vulnerable groups (MVGs) from the perspective of community members, focusing on Korogocho and Viwandani informal settlements in Nairobi. Korogocho is depicted as a long established community with a stable population, offering a context to study entrenched patterns of marginalization. In contrast, Viwandani, located near industrial areas, is characterized by high population mobility due to employment-related migration, presenting a unique setting to examine how transient populations experience vulnerability (Beguy et al., 2015; Chumo et al., 2023b). These contrasting yet proximate settlements offer unique insights into the dynamics of urban marginality and vulnerability shaped by factors like residential stability and economic activity. The central research question is: How do community members identify, prioritize, and describe marginalized and vulnerable groups, and key health and wellbeing issues affecting them within their communities? This study adopts Gordon's framework (Gordon, 2020), which posits three primary forms or roots of vulnerability and marginality: deferential, economic, and social. This framework provides a robust lens through which to analyze the complex dynamics of marginalization and vulnerability within the chosen urban contexts.

2 Theoretical framework and literature review

The deferential vulnerability category, where individuals are subject to the influence of others in non-hierarchical but impactful relationships. This authority often stems from disparities in gender, class, race or knowledge (Oxfam, 2009). Deference can arise from a fear of upsetting the authority figure and facing negative consequences, or from a sincere wish to satisfy someone they admire (Joseph et al., 2023). Individuals in this category may struggle to make fully independent choices about participation and are susceptible to exploitation (Zarowsky et al., 2013). This form of vulnerability underscores the importance of social dynamics and power relations within communities in shaping individual experiences of marginalization (Kenya Ministry of Education, 2017; Sepúlveda and Nyst, 2012). Studies on gender dynamics in informal settlements, often reveal how women's decision-making power within households and the wider community can be significantly influenced by cultural norms and patriarchal structures, leading to deferential vulnerability in areas such as access to resources and healthcare (Chumo et al., 2023b). Similarly, the influence of community elders, adults or dominant ethnic groups can create situations of deferential vulnerability for minority groups or younger individuals (Williams et al., 2019).

The economic vulnerability category, where individuals experience disadvantages in accessing essential resources like housing, income and healthcare (Joseph et al., 2023). Due to their economic situations, their capacity for independent decision-making is often constrained, potentially leading them to participate in activities contrary to their preferences (Whelan and Maitre, 2010). Within informal settlements like Korogocho and Viwandani, economic vulnerability is often exacerbated by factors such as high unemployment rates, precarious informal labor, lack of access to credit and financial services, and inadequate infrastructure (Sepúlveda and Nyst, 2012). Studies have shown the direct link between economic vulnerability and poor health outcomes, as individuals may be unable to afford nutritious food, adequate housing, or timely medical care (Roelen and Sabates-Wheeler, 2012). Furthermore, economic vulnerability can intersect with other forms of vulnerability, such as disability or age, creating compounded disadvantages (Rohwerder, 2014).

The social vulnerability category, where the members are part of socially marginalized groups, with livelihood hardship often a reality for members of these devalued groups (Chumo et al., 2023b). Their treatment stems from broader societal perceptions, including stereotypes that can result in discriminatory practices. These perceptions diminish the worth of members, their concerns, well-being and societal contributions (Oxfam, 2009). Their vulnerability arises from being undervalued, leading to a situation where the risks they face are deemed less significant and less deserving of attention compared to similar risks experienced by more privileged members of society (Zarowsky et al., 2013). Literature on social vulnerability highlights the role of social capital and support networks as potential buffers against marginalization, but these networks themselves can be strained in contexts of widespread poverty and insecurity (Chumo et al., 2023b).

Living in informal settlements greatly impacts certain groups, and their identities worsen their inequality, making them even more marginalized and vulnerable (Joseph et al., 2023). For example, females with a disability are more prone to having less education and experiencing high rates of teenage pregnancy (Varghese and Kumar, 2022). Lacking specific job skills, young individuals often find themselves shut out from economic advancement and work prospects, those with disabilities contend with inadequate and decaying infrastructure. Refugees on the other hand experience compounded marginalization due to their precarious legal standing and limited access to essential resources (Chumo et al., 2023b). Minors, which includes children acting as the head of their family unit (CHHs), face three major challenges: biological and physical challenges; strategic challenges (i.e., children's inadequate levels of autonomy and reliance on adults); and their absence from policy discussions leads to a lack of institutional recognition (Roelen and Sabates-Wheeler, 2012). Irregular earnings, reduced physical and cognitive abilities, and reliance on family members are among the difficulties experienced by older people (Sepúlveda and Nyst, 2012). Higher poverty rates affect persons with disability (PWD), who also struggle with physical barriers, difficulties in communication, and prejudiced attitudes (Rohwerder, 2014; Zarowsky et al., 2013). On the other hand, informal sector workers are poor and vulnerable to a double burden, both economically and socially (Zebardast, 2006; Chumo et al., 2023a).

To minimize disparities and put the LNB pledge into practice at the community level, a strategy involving several stages is essential. This includes pinpointing marginalized and vulnerable populations and ranking them, as well as the fundamental reasons and manifestations of their marginalization (UNSD Group, 2022). This empowers stakeholders to actively participate in the different phases of policy formulation, planning, and programming, particularly the MVGs as a means to achieve the objectives of LNB commitment (Varghese and Kumar, 2022). The Kenyan Constitution of 2010, in its Bill of Rights, specifically addresses the needs of marginalized and vulnerable groups. Article 56 outlines the state's obligation to implement affirmative action programs. These programs are designed to facilitate inclusion in governance and other societal aspects, provided with special opportunities in education and the economy, granted access to employment, empowered to preserve their cultural heritage, and given reasonable access to essential services (Republic of Kenya, 2010).

Overtime, well-known issues that must be overcome in marginality and vulnerability include: “(i) identifying the poor/MVGs among the total population and (ii) constructing a poverty index using the available information on the poor” (Oxfam, 2009; Ensor et al., 2020; Addison, 2006). A wide array of indices for measuring “vulnerability” and “marginality” have been proposed/developed (Arora et al., 2015; Kimani-Murage et al., 2014; Kunath and Kabisch, 2011; Adrien Coly et al., 2012), but little effort has been made to recognize and rank who is marginalized and vulnerable, even with the presence of guiding principles at the regional, international and national levels regarding LNB (Oxfam, 2009; Sen, 1990; Williams et al., 2019). While some studies have attempted to define marginality and vulnerability, they often lack meaningful community engagement and fail to prioritize ranking processes (Oxfam, 2009; Williams et al., 2019; Masong et al., 2021; Zerbo et al., 2020). This study bridges this gap by engaging the community in identifying, ranking, and prioritizing community groups and individuals along a spectrum of marginalization and vulnerability, a process grounded in the perspectives of the community members. These uncovers the intricate and often unseen dimensions of vulnerability that quantitative approaches may miss.

3 Methods

3.1 Study design and setting

This was a qualitative approach using two-pronged strategy, including descriptive social mapping and participatory focus group discussions (FGDs) with community members.

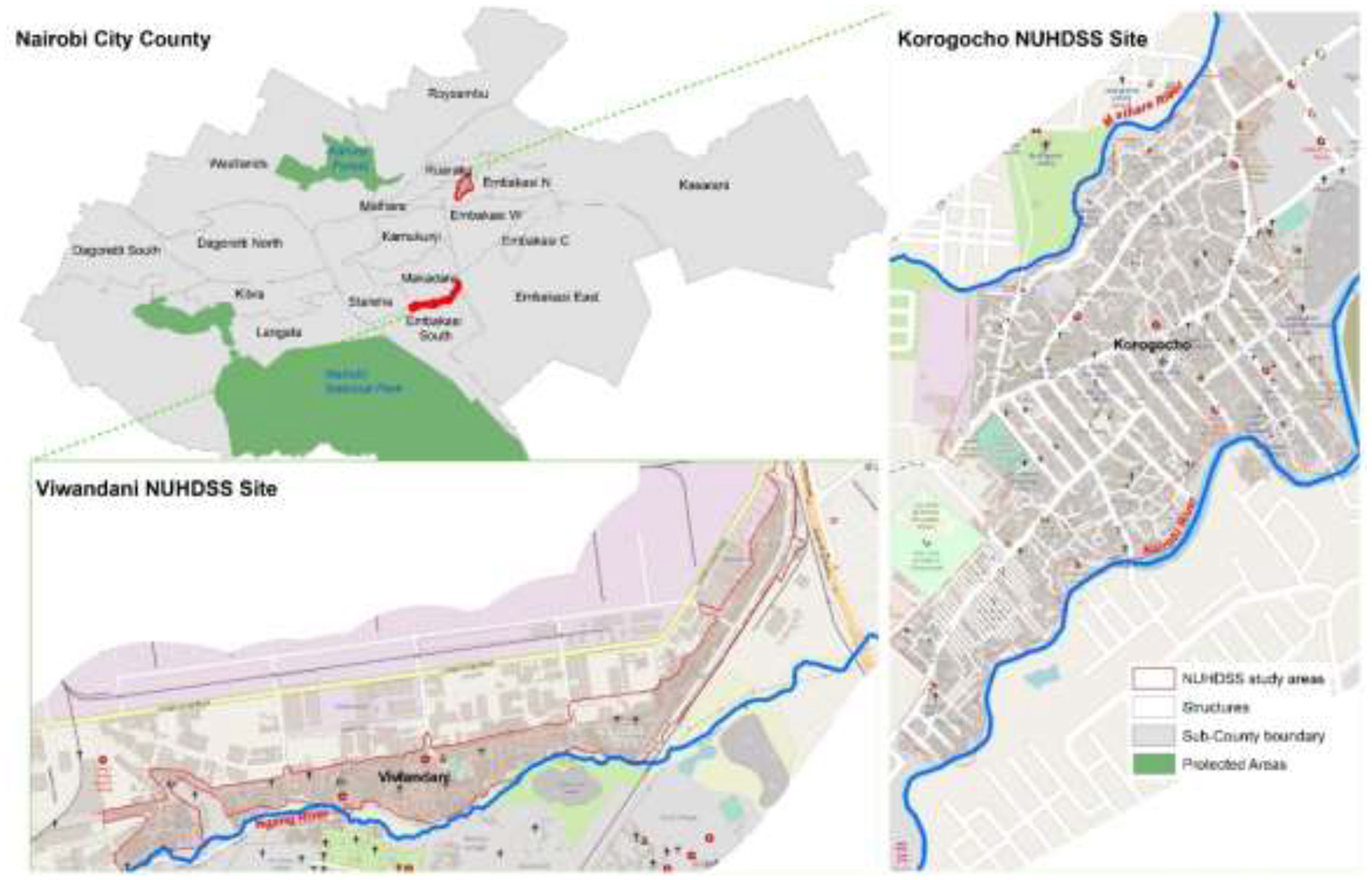

The research was conducted within the Nairobi Urban Health and Demographic Surveillance System (NUHDSS) areas, specifically in the Korogocho and Viwandani informal settlements of Nairobi (Figure 1). The NUHDSS was established in 2002 by the African Population and Health Research Center (APHRC; Beguy et al., 2015). Korogocho is characterized by a stable population, with many residents having established long-term residence (Emina et al., 2011). Viwandani, however, located near an industrial zone, exhibits a more dynamic population of residents who frequently move for work or job-seeking opportunities within that area (Emina et al., 2011; Figure 1).

Figure 1

Study sites (Chumo et al., 2023c).

3.2 Population and sampling

The study population comprised the general population residing in the informal settlements. This included a diverse array of social groups within the community, as identified in prior research on community profiling (Chumo et al., 2023c) and the role of the Community Advisory Committee (CAC; Chumo et al., 2022).

Purposive sampling was employed to select social study groups, prioritizing diversity in demographics and community roles, such as age and gender. Data saturation was achieved at the 40th group, at which point additional group selection ceased. Each group consisted of eight purposively selected participants, representing eight units/villages within each study site. Consequently, the total sample size was equivalent to 320 participants. Purposive sampling was also utilized to select individual study participants, drawing from the NUHDSS sampling frame to ensure a diverse representation of social groups across the eight villages/units in both study sites. The study population encompassed individuals from various life stages, social statuses, occupations, refugee backgrounds, and persons with disabilities (PWD), among other groups (Table 1).

Table 1

| S/no | Categories | Viwandani | Korogocho | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Middle-aged groups (35–50 years) | 2 (M&F) | 2(M&F) | 4 |

| 2 | Youth | 2 (M&F) | 2(M&F) | 4 |

| 3 | Elderly (55 + years) | 2 (M&F) | 2(M&F) | 4 |

| 4 | Village heads | 2(M&F) | 2(M&F) | 4 |

| 5 | Persons with disability (PWDs) | 2(M&F) | 2(M&F) | 4 |

| 6 | Sanitation workers | 2 (M&F) | 2 (M&F) | 4 |

| 7 | Garbage collectors | 2 (M&F) | 2 (M&F) | 4 |

| 8 | Community based organizations (CBOs) | 2(M&F) | 2 (M&F) | 4 |

| 9 | Refugees | 2 (F) | 2 (M) | 4 |

| 10 | Commercial sex workers | 1 (M) | 1 (F) | 2 |

| 11 | Community health volunteers (CHVs) | 1 (M) | 1 (F) | 2 |

| Total | 20 | 20 | 40 |

Study composition.

M, Male; F, Female. Each group composed of 8 participants.

3.3 Data collection process

We collected data using focus group discussions (FGDs) and social mapping exercises conducted between August and September 2020. After obtaining informed consent, research assistants facilitated social mapping activities. Social maps were prepared by community members to depict specific social aspects. A social map or chart illustrates the elements that local residents consider significant and pertinent (Chumo et al., 2023d). Social mapping is a valuable social science research method, offering diverse approaches to analyze and visualize social spaces, relationships and processes (Kathirvel et al., 2012). It encompasses various techniques, including participatory mapping and data visualization to reveal complex social dynamics and support collaboration (Kathirvel et al., 2012; Marais and Van Biljon, 2017). These provide tools for promoting dialogue, empowerment, and transformation in communities, making them increasingly relevant for social science research and policy development (Marais and Van Biljon, 2017).

The activity involved mapping and charting six key themes: the various stakeholders, influential groups, vulnerable groups, marginalized groups, existing social structures and the changes individuals would implement if they held positions of power. In this article we report results on identified MVGs ranked from the most to the least marginalized and vulnerable based on their perspectives, and issues affecting MVGs in priority. The social mapping outputs served as a foundation for in-depth exploration during FGDs (Figure 2). The FGD guide's development drew upon both theoretical frameworks and empirical research, and its effectiveness was enhanced through preliminary testing. Questions focused on understanding marginality, vulnerability, root causes of MVGs, and related challenges. Additionally, there were questions on charted social mapping sheets that reinforced the study guide. All interviews adhered to COVID-19 prevention guidelines issued by the Ministry of Health (MoH). Social mapping exercises lasted approximately 1 h, while FGDs ranged from 45 to 60 min.

Figure 2

Data collection process.

3.4 Data quality control

To ensure robust data collection, Research Assistants were carefully selected by APHRC researchers based on their extensive experience in qualitative research (at least 5 years) and community endorsement within the study sites. These individuals received 5 days of comprehensive training on the study's goals, social mapping methodologies, analysis of social structures, ethical research practices, safeguarding measures, the study's tools, and data collection processes adapted for the COVID-19 pandemic. Throughout fieldwork, supervisors accompanied the teams to monitor the process and identify any factors that could compromise data quality. At the end of each day, debriefing sessions were held to discuss key findings, refine probing techniques, and track the progress.

3.5 Data analysis

The audio data collected from participatory social mapping and FGDs were transcribed into MS Word documents. To ensure comprehensive data capture, these transcripts were reviewed and verified by an independent individual. Transcripts requiring translation from Swahili to English were subjected to a separate verification process to confirm that the original meaning was accurately conveyed. The finalized transcripts were then imported into NVivo 12 software (QSR International, Australia) for coding and analysis. Anonymity and informed analysis facilitated by assigning each transcript a unique identifier that included the session date, study site, and participant gender.

To analyze the social mapping matrices and understand the dynamics of the social mapping discussions, standard summative content analysis methods were employed. Codes exhibiting similarities were consolidated into single categories through a process of consensus-based discussion. The subsequent stage involved the creation of “tree nodes,” or overarching categories, which were derived inductively from the earlier coding. The participatory FGD transcripts were analyzed using thematic analysis to identify themes concerning vulnerable and marginalized groups, the fundamental causes and drivers of their marginality and vulnerability, and the ways in which marginalization is addressed. Newly identified themes were added to the coding framework, and the transcripts were reread to confirm thorough coding. This comprehensive analysis formed the foundation for a detailed profile of vulnerable and marginalized groups in the settlements.

3.6 Ethical considerations

This study underwent a comprehensive ethical review process, receiving approval from AMREF Health Africa's Ethics & Scientific Review Committee (ESRC), REF: AMREF-ESRC P747/2020, and obtaining a research permit from the National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation (NACOSTI), REF: NACOSTI/P/20/7726. Further ethical clearance was granted by the internal review boards of the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (LSTM) and the APHRC. In adherence to ethical principles, all participants provided informed written consent prior to any interview, including for the use of any photos or videos. Before obtaining consent, participants received a research information sheet explaining the study's objectives, procedures, how their data would be used, right to withdraw at any point without consequence, and measures in place to ensure the confidentiality of their information. Research Assistants clarified the contents of this sheet and addressed all participant inquiries. Only after this process were participants asked to sign a consent form if they willingly agreed to participate. To safeguard participant identities, all data was anonymized. Audio recordings were transcribed with the removal of all personal identifiers, and transcripts were stored securely on a password-protected computer accessible solely to the research team.

4 Results

We present study results on who is left behind/who is marginalized and vulnerable, as well as key issues affecting the MVGs from the perspectives of community social groups. The frequencies reported are derived from the dominant frequency identified across all social mapping sessions and further emphasized across the subsequent FGDs.

Comparative analysis of marginalized and vulnerable groups and their primary concerns across the two study sites revealed no differences. As such, to avoid redundancy, the findings are presented as a unified analysis.

4.1 Who is left behind: vulnerable and marginalized groups

Participants in both study sites identified social groups they considered marginalized and vulnerable.

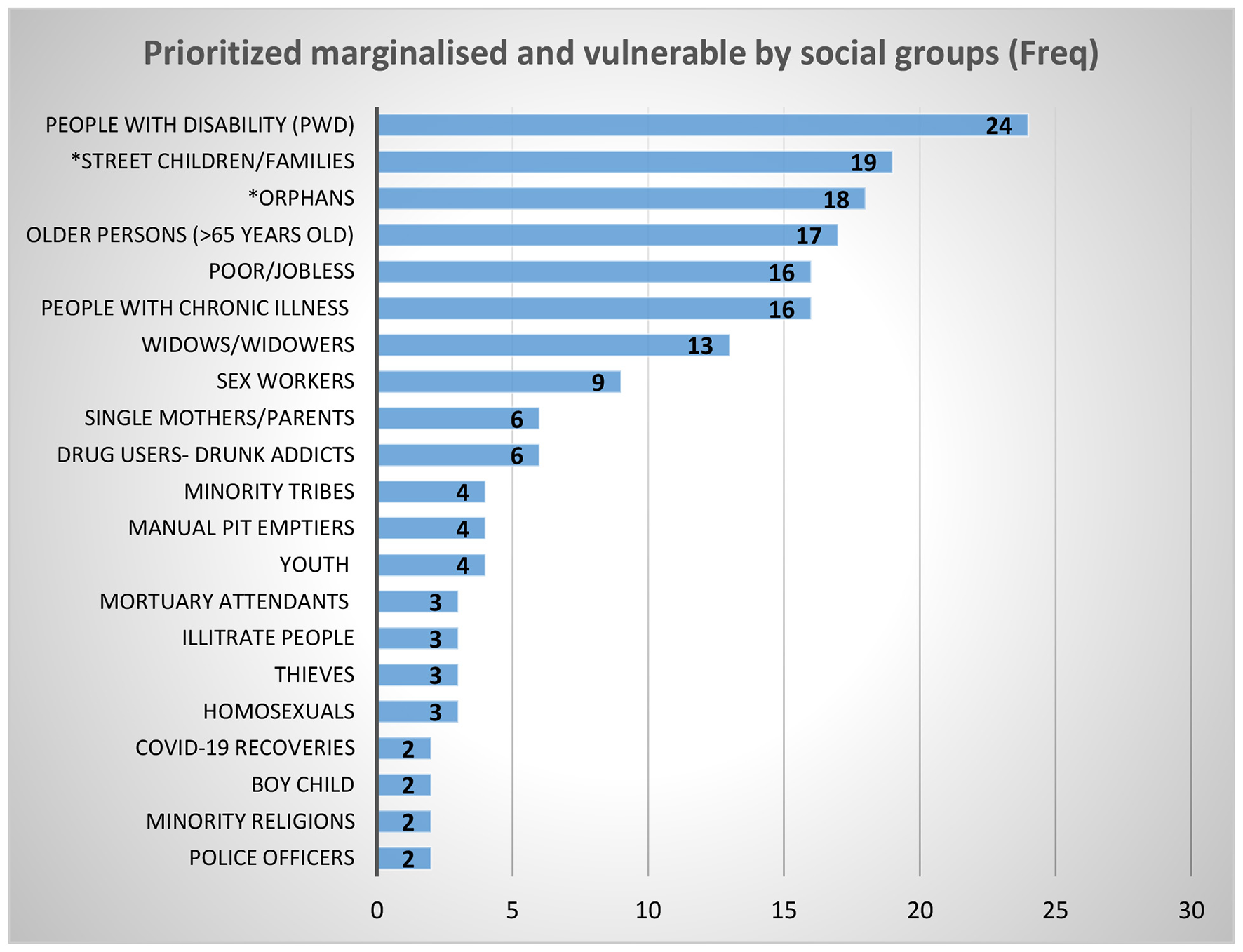

These included older persons, people with disabilities (PWD), children, women, refugees, people with chronic illness, unemployed/jobless, widowers, sex workers, drug addicts, single mothers, and youth, among others. Notably, child-heads of households (CHHs), PWD and Older persons were identified as the most marginalized and vulnerable groups (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Vulnerable and marginalized groups in priority; *child–headed households: orphans, street children/families. Child-headed households are made up of individuals below the age of 18 who serve as the primary providers for their families. In this study, they were represented by orphans and children from street families.

We went further to analyze forms of vulnerability and marginality.

4.2 Forms of vulnerability and marginality

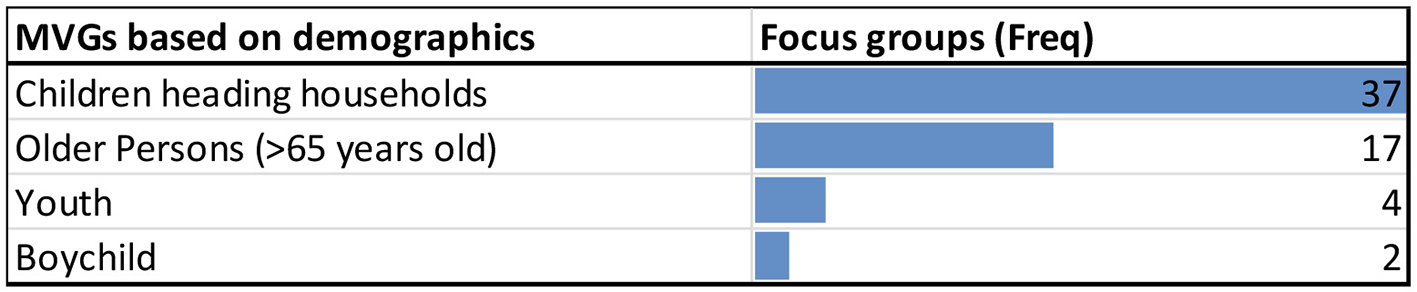

Deferential vulnerability and marginality are usually incurred by persons who are under the authority of others and arise due to power imbalances based on demographic characteristics like age or gender (Gordon, 2020). An example of this is the adult/parent–child relationship, where an adult/parent has authority over a child. Study participants identified CHHs, older persons, youth, and a boy child (Figure 4) to have had deferential vulnerability and marginality. Deferential was described to stems from a concern about upsetting the authority figure or in instances when individuals had concerns about loss of access or resources. In this situation, there were reported risks of exploitation and inability to make truly autonomous decisions by the vulnerable groups as depicted by the below except.

Figure 4

Deferential vulnerability and marginality/vulnerable and marginalized groups based on demographics.

“Street children and orphans depend on adults for guidance, sometimes they end up in gender based violence, and discriminated by other children in the community. It is a very hard life…Children heading households are generally discriminated by other children in play and other groups because they cannot afford basic needs, have sickly parents or have parents who are in prison, and such like.” (FGD, Male Community Health Promoter)

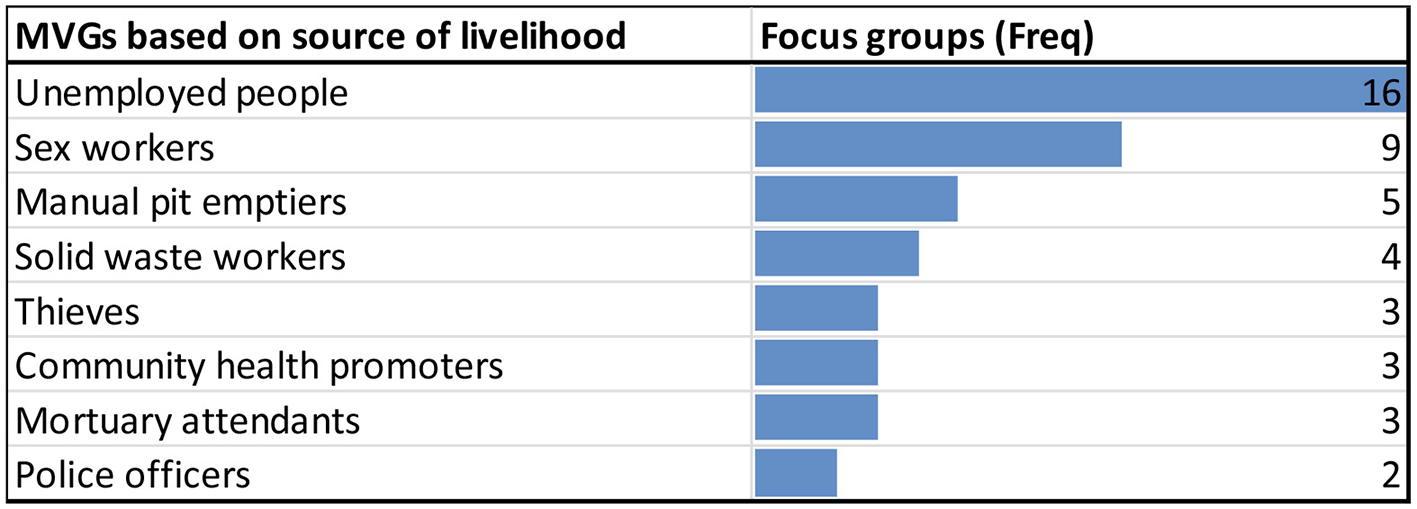

Economic/livelihood vulnerability and marginality are usually incurred by persons who are disadvantaged regarding social goods and services such as income (Gordon, 2020). In our study, the unemployed people faced economic vulnerabilities. Some individuals engaged in hazardous sources of livelihood also faced the vulnerabilities and marginalities associated with their work (Figure 5). The quote below highlights livelihood vulnerabilities experienced by MVGs in the community.

Figure 5

Economic/livelihood vulnerability and marginality/vulnerable and marginalized groups based on livelihood.

“Unemployed people go through a lot of mental challenges…those who have jobs that are risky because they are done in a poor environment, or those whose jobs are not desirable by people in the community are vulnerable and marginalized from community… Nobody here {in the community} can talk to you if there is a grapevine that you are a thief, or a sex worker.” (FGD, Male Youth)

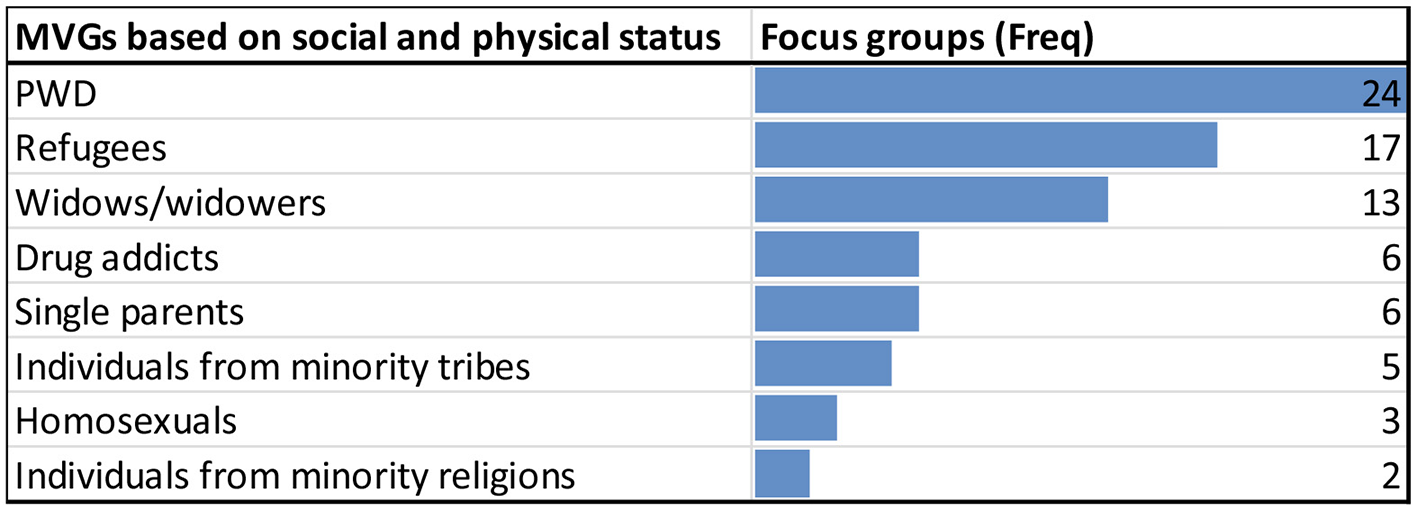

Social vulnerability and marginality are usually incurred by individuals/groups who are members of undervalued or disadvantaged social groups (Gordon, 2020). In our study, social vulnerability and marginalities were represented by PWD, refugees, and widowers/widows, among others (Figure 6), and arose from the negative, discriminatory, and stereotypical perception of certain individuals. These perceptions often undervalued the welfare and societal contributions of such groups, as these groups were considered less important than other groups. Below except highlights social vulnerabilities related to discrimination experienced by PWD in their homes.

Figure 6

Social vulnerability and marginality/vulnerable and marginalized groups based on social and physical status.

“The disabled are marginalized…An individual has a disabled person in the house but they hide them, they don't want them to be seen. When you go in and check at this child…the way they are taken care of is not the same as the rest of the children…They don't often bath them or feed them if they are unable to feed themselves.” (FGD, Female CBO)

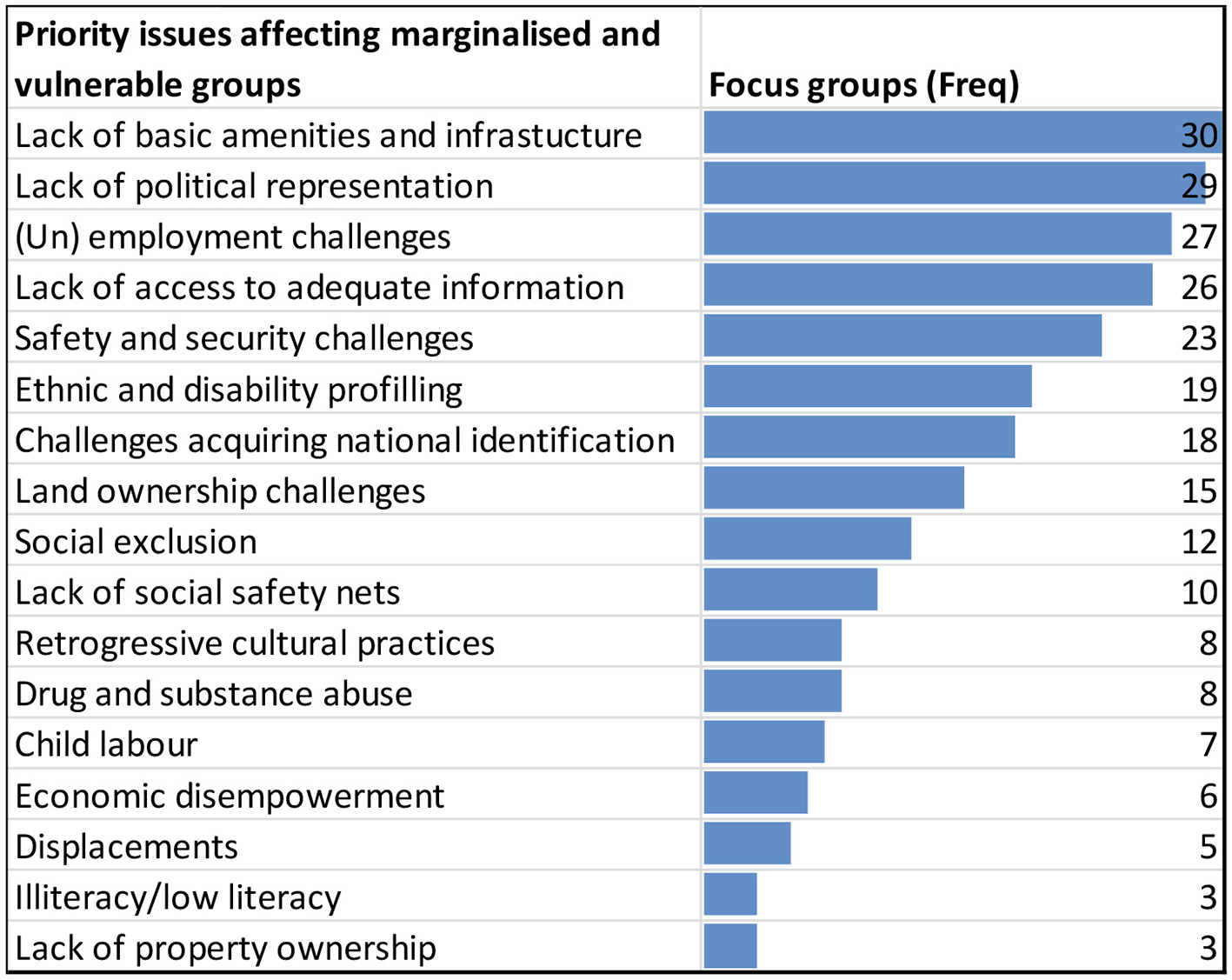

4.3 Major/key issues affecting marginalized and vulnerable groups

Marginalized and vulnerable groups were primarily affected by several critical issues, including deficiencies in basic amenities and infrastructure, insufficient political representation, challenges related to unemployment or lack of adequate employment, limited access to necessary information, and problems concerning safety and security, among other difficulties (Figure 7).

Figure 7

Issues affecting marginalized and vulnerable groups in priority.

4.3.1 Lack of basic amenities

MVGs were described to lack basic amenities like educational and healthcare facilities, or clean water, sanitation and hygiene facilities, and infrastructure like passable roads and floodlights. For example, one informal settlement was illustrated to have only two public primary schools and two public healthcare facilities, constraining residents of MVGs to incur challenges regarding access and quality. The development of physical infrastructures was described as insufficient and the provision of basic services was often taken over by an unregulated private sector, and this affected the accessibility, affordability, and quality of services available. As this was the most important issue affecting the MVGs, we probed for recommendations, as presented in Table A1. Below excepts highlights challenges related to inadequate/lack of basic needs experienced by MVGs in informal settlements.

“It is unacceptable that marginalized and vulnerable groups continue to lack access to basic amenities like education, healthcare, and clean water. Without these essentials, how can we expect them to thrive and contribute to society? Without passable roads and proper lighting, our safety is compromised, especially at night, and more so for the marginalised people like.” (FGD, female middle aged)

“The private sector should not be left unchecked in providing basic services. When profit comes before people, it's the most vulnerable who suffer the consequences.” (FGD, female older person)

4.3.2 Lack of political representation

Marginalized and vulnerable groups lacked representation in government bodies and decision-making processes, leading to their voices being unheard in policymaking. Underrepresentation was described to perpetuate inequality, because when certain groups are not adequately represented in government, policies and decisions may not address their unique needs and challenges. This was illustrated to widen the gap between marginalized groups and the rest of society. When certain groups are systematically excluded from this process, it undermines the democratic ideals of equality and participation. This lack of representation eroded trust in government institutions among marginalized communities, and often reflected broader power imbalances within society. Below excepts depict challenges related to lack of political representation experienced by PWDs.

“Voices of vulnerable people like children or PWD are continuously side-lined in policymaking, leaving them without a say in decisions that directly affects them. It is as if their struggles and needs do not matter to those in power. Even our {Youth} needs are not considered anywhere in many cases.” (FGD, female youth)

“Without representation, our concerns are often overlooked, perpetuating the cycle of inequality and marginalization. How can policies address our unique challenges if those crafting them don't understand or acknowledge our experiences?” (FGD, male PWD)

4.3.3 (Un) employment challenges

The study participants described how MVGs faced difficulties in accessing employment opportunities due to various factors such as discrimination, lack of education or skills training, or limited job availability in their areas. For example, individuals belonging to certain ethnic groups might face discrimination during the hiring process, resulting in fewer job opportunities for them. MVGs living in informal settlements also face social exclusion and marginalization, which can exacerbate their unemployment challenges. Discrimination based on factors such as ethnicity, gender, or disability can limit access to employment opportunities and perpetuate systemic inequalities. Moreover, the stigma associated with residing in informal settlements can affect residents' self-esteem and social networks, further hindering their ability to access employment and economic opportunities. Below is what a study participant whose utterances represents the majority had to say regarding unemployment challenges among MVGs.

“Discrimination and lack of education make it nearly impossible to secure stable employment… I have experienced first-hand how my ethnicity can be a barrier to getting hired. It's disheartening to be judged based on factors beyond my control.” (FGD, Male Youth)

4.3.4 Difficulties accessing information

Our study participants described how MVGs had difficulties accessing essential information, which hindered their ability to make informed decisions. This included limited access to educational resources, healthcare information, or government services. Overall, the lack of access to essential information exacerbates the existing inequalities faced by MVGs, perpetuating their marginalization and hindering their ability to improve their socio-economic conditions. Below except highlights challenges related to service provision as a result of difficulties in information access.

“Lack of information can exterminate someone, for example, healthcare information is a luxury, we cannot afford to use internet. We rely on word of mouth or outdated pamphlets for information about staying healthy, which is generally inadequate to protect us from illnesses…Without access to essential information, we're stuck in a cycle of poverty and marginalization. It's like trying to build a house without a plan—impossible to make progress.” (FGD, Female Village Head)

4.3.5 Safety and insecurity challenges

Informal settlements were characterized by elevated rates of crime and violence, such as robbery, assault, and gang-related activities. Residents, particularly women, children, and older persons, felt unsafe walking alone or venturing out after dark due to the risk of encountering criminal elements. There were examples on a lack of adequate lighting and infrastructure, making MVGs susceptible to crime and accidents, especially at night. Poorly lit streets and alleyways created opportunities for criminal activity to thrive, while inadequate roads and pathways hindered emergency response and access to essential services. Additionally, the absence of basic infrastructure such as proper drainage systems led to flooding during heavy rains, posing further safety risks to residents. Land disputes and forced evictions not only disrupted communities but also exacerbated feelings of insecurity and instability among residents. Fear of losing homes and belongings created immense stress and anxiety, particularly for vulnerable people such as single mothers, older persons and PWD. Study participants whose descriptions represent a majority depicted how safety and insecurity challenges were prevalent among MVGs.

“Living in our settlement is insecure. Threats of violence are always looming, making it difficult to feel safe even in our own homes-even when accessing a sanitation facility at night. As a woman, I am constantly on edge whenever I have to leave the house, especially after dark. The fear of harassment or assault is a constant companion.” (FGD, female middle-aged person)

“The lack of proper lighting and infrastructure in our settlement puts us at risk every day. It is like we are invisible to the authorities who have neglected our safety for far too long… There is also uncertainty of land tenure, and fear of eviction looms large, leaving us feeling powerless and insecure in our own homes.”— (FGD, male older person)

4.3.6 Ethnic and disability profiling challenges

Marginalized groups often faced discrimination and prejudice based on factors like ethnicity or disability. For instance, PWD encountered barriers to accessing public spaces or employment opportunities due to lack of accommodations or societal stigma. Individuals with disabilities living in informal settlements often faced discrimination and barriers to full participation in community life, particularly, physical barriers such as lack of wheelchair-accessible infrastructure or transportation can restricted their mobility and independence. Inaccessible housing units or narrow pathways made it difficult for people with mobility impairments to navigate their surroundings safely. Moreover, negative attitudes and stereotypes toward PWD led to social isolation and exclusions. Below except highlights profiling challenges experienced by PWD in the community, affecting their full participation in decisions.

“As a person with a disability, we face constant barriers in accessing public spaces and job opportunities. Without proper accommodations and understanding, we are often left on the margins with no one to help us… sometimes I feel like crying, the lack of accessible infrastructure and negative attitudes towards PWD in this community make it difficult to participate fully in community activities and decisions.” (FGD, Female PWD)

Residents in our study sites were from diverse ethnic backgrounds. Participants described how certain ethnic groups faced discrimination or prejudice from others within the settlement. The discrimination manifested in various forms, including social exclusion, verbal harassment, or even physical violence. For example, individuals belonging to minority ethnic groups were subjected to derogatory remarks or stereotypes, leading to their marginalization within the community as described below in the except.

“Discrimination based on ethnicity is like a shadow, as it follows us everywhere we go. It is sad to be judged based on factors beyond our control, and it only serves to deepen the divides within our community.” (FGD, Male Village Head)

Worthy to note is that individuals who belonged to both marginalized ethnic groups and had disabilities faced compounded discrimination and marginalization, making it more challenging to access resources, opportunities, and support services within the informal settlement.

“Being both disabled and from a minority ethnic background feels like fighting battles on two fronts. The compounded discrimination makes it feel like there is no place for us in society, let alone in our own community.” (FGD, Male PWD)

4.3.7 Challenges acquiring national identification card

MVGs faced challenges accessing national identification documents, which are often required to benefit from a spectrum of state-provided resources, encompassing medical care, educational opportunities, social safety nets, and monetary assistance. This perpetuates their marginalization and exclusion from essential resources and opportunities for socio-economic advancement. For example, urban refugees encountered prejudice or hostility from government officials when seeking to obtain identification documents. Without official documentation, the individuals faced barriers to accessing essential services, voting, or exercising other rights of citizenship. The quote below highlights the frustration, discrimination, and systemic barriers faced by MVGs in obtaining national identification documents.

“The lack of a national ID card makes me feel like a second-class citizen. I am denied the right to vote and access to government services… Being a refugee in slums comes with its own set of challenges, as Government officials and service providers treat us with suspicion and hostility when we try to access basic rights like healthcare or education.” (FGD, Male Youth)

Other challenges included land ownership challenges, social exclusion, lack of social safety nets, retrogressive cultural practices, drug and substance abuse, child labor, economic disempowerment, displacements, illiteracy/low literacy, and land ownership (Figure 7).

5 Discussion

This qualitative research identified and examined the vulnerabilities and marginalization of specific groups within Nairobi's informal settlements, providing a nuanced understanding of the challenges they face. Similar to the caution raised by previous studies describing how quantitative studies often fail to capture the nuanced experiences of marginalized groups, necessitating qualitative approaches to understand vulnerability and marginality (Lall, 2023). Identifying and assessing patterns of marginality and vulnerability within a local context, as undertaken in our study, is crucial for enabling appropriate and targeted actions (Varghese and Kumar, 2022). The study's findings are contextualized within existing literature on urban poverty and social exclusion, and their implications for achieving the SDGs.

The study pinpoints several MVGs in Nairobi's informal settlements, including persons with disabilities, child-headed households, older persons, and unemployed individuals. The prominence of older persons, persons with disabilities, and child-headed households as highly vulnerable is consistent with studies in South Africa, India, and Latin America, which also highlight the significant social and economic disadvantages faced by these groups in urban informal settings (Gallardo, 2018). These consistent findings across diverse geographical locations suggest a universality in certain forms of vulnerability within marginalized urban populations. This study extends the previous studies by ranking the MVGs, and further ranking the groups in three key dimensions of vulnerability and marginality; deferential, social and economic/livelihood vulnerabilities. Vulnerability and marginality studies mostly considers economic/livelihood vulnerabilities (Gordon, 2020; Whelan and Maitre, 2010). This study expands on this by explicitly incorporating deferential and social vulnerabilities emphasizing societal biases that contribute to marginalization. These resonates with Sen's work on capabilities deprivation, where social and political exclusion limit individuals' ability to function and thrive (Sen, 1990). The study also corroborates that vulnerability and marginality can overshadow group identity (e.g., race, gender, poverty), and that prioritizing the needs of the most disadvantaged is crucial (Ensor et al., 2020; von Braun and Gatzweiler, 2014).

Challenges identified by community such as lack of basic amenities, political representation, employment, information access, safety, and discrimination, mirror those documented in studies of informal settlements globally, including in Accra, Ghana, and Dhaka, Bangladesh (Varghese and Kumar, 2022; Zarowsky et al., 2013). This study extends their scope by ranking the challenges in order of priority, to facilitate targeted interventions. The challenges have significant implications for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The lack of basic amenities and infrastructure directly relates to SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation) and SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities). Issues of inadequate political representation and discrimination are linked to SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities) and SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions). Furthermore, challenges related to employment barriers and lack of access to information are relevant to SDG 1 (No Poverty) and SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth; Long et al., 2023; Kamalipour, 2016). This study's emphasis on the interconnectedness of social, economic, and political factors in creating and perpetuating vulnerability aligns with the broader understanding of poverty and inequality within the SDGs (Boza-kiss et al., 2021; Nolan, 2015). Addressing these challenges and promoting inclusive and sustainable urban development, in line with the Agenda's core principle of “leaving no one behind,” is essential for making progress toward these interconnected SDGs and improving the lives of vulnerable populations in Nairobi's informal settlements. The study uniquely addresses this by directly involving the community in identifying and prioritizing MVGs and their specific concerns, ensuring that policy and action are grounded in local realities.

The convergence of findings across the two study sites underscores the pervasive impact of informal settlement living on vulnerability and marginalization. This consistency suggests that while geographical location is a significant factor, the experience of living in an informal settlement itself exacerbates marginalization for the most vulnerable. By highlighting the voices and experiences of these frequently ignored populations, this research provides a richer, more contextually relevant understanding of the experiences of marginalized and vulnerable groups, which is vital for achieving the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Goals and its commitment to leaving no one behind.

6 Conclusion

In conclusion, addressing the challenges faced by MVGs in Nairobi's informal settlements requires a comprehensive, community-centered approach. This approach should go beyond basic service provision to empower MVGs, integrate their perspectives and foster social and economic inclusion. Findings align with global research on urban poverty and social exclusion, highlighting the interconnected nature of vulnerabilities. These underscores the urgent need for inclusive and participatory approaches to achieve the SDGs commitment to leaving no one behind by emphasizing the priorities and lived experiences of MVGs. Approaches include supporting inclusive microfinance, implementing targeted social protection programs, and combating discrimination through awareness campaigns and promotion of social inclusion. Development initiatives, including investments in essential infrastructure, should be designed with MVGs' specific needs in mind, and service provision should be tailored to their diverse preferences, considering accessibility, safety, and cultural appropriateness. Additionally, transparent and accountable governance with strong partnerships between government, civil society, and communities is essential.

Future research should delve deeper into the specific vulnerabilities faced by different subgroups within the MVG. Cross-group comparisons can help to identify the unique challenges and needs of each subgroup, allowing for the development of more targeted and effective interventions. This research will not only contribute to a deeper understanding of vulnerability and marginalization in informal settlements, directly informing the achievement of the SDGs, but also inform the development of more effective and equitable policies and programs that truly empower MVGs and improve their quality of life.

The methodology of this study can be replicated, as it offers promising pathways for further investigation. It can be extended to other urban informal settlements within Nairobi, across Kenya, or in comparable urban settings globally that are grappling with similar issues of social exclusion. Reproducing the study in diverse geographical or cultural contexts would serve to test the generalizability of the findings and help identify context–specific factors that influence both the vulnerabilities and the resilience of MVGs. These studies would significantly enrich the global evidence base on urban poverty, facilitating knowledge sharing and the adaptation of best practices for inclusive urban development worldwide. Finally, implementing longitudinal studies would be crucial to monitor changes in the socio-economic status and social inclusion of MVGs over an extended period.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Institutional Review Board Statement: The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the AMREF Africa Ethics and Scientific Review Committee (ESRC/P747/2019; Date: 8 February 2020) and the National Council for Science, Technology, and Innovation (NACOSTI/P/20/7726; Date: 20 November 2020). We also received broader ethical clearance from the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (Protocol: 19-089; Date 21 January 2020). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

IC: Formal analysis, Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Validation, Investigation, Software, Data curation, Conceptualization, Supervision. CK: Supervision, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Resources. BM: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Investigation, Resources, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Visualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. GCRF Accountability funded the project activities through UKRI Collective Fund award with award reference ES/S00811X/1.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Addison T. (2006). Human Development Report, 1990. Human Development Report, 1991. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 46.

2

Adrien Coly M. E. T. De Risi R. Di Ruocco A. Garcia-Aristizabal A. Herslund L. Jalayer F. et al . (2012). Climate Change and Vulnerability of African Cities. Available online at: http://www.unhabitat.org/grhs/2011 (Accessed May, 2016).

3

Arora S. K. Shah D. Chaturvedi S. Gupta P. (2015). Defining and measuring vulnerability in young people. Indian J. Commun. Med.40, 193–197. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.158868

4

Beguy D. Elung'ata P. Mberu B. Oduor C. Wamukoya M. Nganyi B. et al . (2015). HDSS profile: the Nairobi urban health and demographic surveillance system (NUHDSS). Int. J. Epidemiol.44, 462–471. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu251

5

Boza-kiss B. Pachauri S. Zimm C. (2021). Deprivations and inequities in cities viewed through a pandemic lens. Front. Sustain. Cities3:645914. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2021.645914

6

Browne E. (2015). Social Protection: Topic Guide. Birmingham: GSDRC, University of Birmingham.

7

Chumo I. Kabaria C. Mberu B. (2023a). Social inclusion of persons with disability in employment: what would it take to socially support employed persons with disability in the labor market?Front. Rehabil. Sci.4:1125129. doi: 10.3389/fresc.2023.1125129

8

Chumo I. Kabaria C. Oduor C. Amondi C. Njeri A. Mberu B. et al . (2022). Community advisory committee as a facilitator of health and wellbeing: a qualitative study in informal settlements in Nairobi, Kenya. Front. public Heal.10:1047133. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1047133

9

Chumo I. Kabaria C. Shankland A. Mberu B. (2023b). Unmet needs and resilience: the case of vulnerable and marginalized populations in Nairobi's informal settlements. Sustainability15:19. doi: 10.3390/su15010037

10

Chumo I. Mberu B. Kabaria C. (2023c). Mapping the Social and Governance Terrain in Informal Settlements – Community Profilling in Korogocho and Viwandani, Nairobi. ARISE Consortium. Available online at: https://www.ariseconsortium.org/learn-more-archive/community-profiling-in-korogocho-and-viwandani-nairobi/

11

Chumo I. Mberu B. Kabaria C. (2023d). Social Mapping in Korogocho and Viwandani, Nairobi ARISE Consortium. Available online at: http://knowhub.aphrc.org/handle/123456789/1007

12

Emina J. Beguy D. Zulu E. M. Ezeh A. C. Muindi K. Elung'ata P. et al . (2011). Monitoring of health and demographic outcomes in poor urban settlements: evidence from the Nairobi urban health and demographic surveillance system. J. Urban Health88, 200–218. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9594-1

13

Ensor T. Bhattarai R. Manandhar S. Poudel A. N. Dhungel R. Baral S. et al . (2020). From rags to riches: assessing poverty and vulnerability in urban Nepal. PLoS ONE15:e0226646. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226646

14

Gallardo M. (2018). Identifying vulnerability to poverty: a critical survey. J. Econ. Surv.32, 1074–1105. doi: 10.1111/joes.12216

15

Gordon B. G. (2020). Vulnerability in research: basic ethical concepts and general approach to review. Ochsner J.20, 34–38. doi: 10.31486/toj.19.0079

16

Joseph J. Sankar H. Benny G. Nambiar D. (2023). Who are the vulnerable, and how do we reach them? Perspectives of health system actors and community leaders in Kerala, India. BMC Public Health23, 1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12889-023-15632-9

17

Kamalipour H. (2016). Forms of informality and adaptations in informal settlements. Int. J. Architect. Res.10, 60–75. doi: 10.26687/archnet-ijar.v10i3.1094

18

Kamalipour H. (2019). Towards an informal turn in the built environment education: informality and urban design pedagogy. Sustainability11, 1–14. doi: 10.3390/su11154163

19

Kathirvel S. Jeyashree K. Patro B. K. (2012). Social mapping: a potential teaching tool in public health. Med. Teach.34, e529–e531. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.670321

20

Kenya Ministry of Education (2017). The Kenya Primary Education Develoment (Priede) Project Report on the Vulnerable and Marginalised Groups September 2017. Nairobi.

21

Kimani-Murage E. W. Schofield L. Wekesah F. Mohamed S. Mberu B. Ettarh R. et al . (2014). Vulnerability to food insecurity in urban slums: experiences from Nairobi, Kenya. J. Urban Heal.91, 1098–1113. doi: 10.1007/s11524-014-9894-3

22

Kunath A. Kabisch S. (2011). Review and Evaluation of Existing Vulnerability Indicators for Assessing Climate Related Vulnerability in Africa Article. UFZ-Bericht, Helmholtz-Zentrum für Umweltforschung.

23

Lall A. (2023). The cost of hidden histories: critical perspectives on qualitative methods. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Econ. Res.8, 3360–3667. doi: 10.46609/IJSSER.2023.v08i11.021

24

Long G. Censoro J. Rietig K. (2023). The sustainable development goals: governing by goals, targets and indicators. Int. Environ. Agreements Polit. Law Econ.23, 149–156. doi: 10.1007/s10784-023-09604-y

25

Marais M. Van Biljon J. (2017). Social mapping for supporting sensemaking and collaboration: the case of Development Informatics research in South Africa. Int. Inf. Manag. Corp.1, 1–11. doi: 10.23919/ISTAFRICA.2017.8102336

26

Masong M. C. Ozano K. Tagne M. S. Tchoffo M. N. Ngang S. Thomson R. et al . (2021). Achieving equity in UHC interventions: who is left behind by neglected tropical disease programmes in Cameroon? Achieving equity in UHC interventions: who is left behind by neglected. Glob. Health Action14:1886457. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2021.1886457

27

Nolan L. B. (2015). Slum definitions in urban India: implications for the measurement of health inequalities. Popul. Dev. Rev.41, 59–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2015.00026.x

28

Oxfam (2009). Urban Poverty and Vulnerability, 1st Edn., Vol. 1. Nairobi: OxfamGB.

29

Republic of Kenya (2010). Kenya's Constitution of 2010, 1–308. Republic of Kenya.

30

Roelen K. Sabates-Wheeler R. (2012). A child-sensitive approach to social protection: serving practical and strategic needs. J. Poverty Soc. Justice20, 291–306. doi: 10.1332/175982712X657118

31

Rohwerder B. (2014). Disability Inclusion in Social Protection. GSDRC Helpdesk Research Report 1069, 320–321. Available online at: www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence (Accessed July 2018).

32

Sen A. (1990). Equality of what? On welfare, goods and capabilities. Louvain Econ. Rev. 56, 357–382.

33

Sepúlveda M. Nyst C. (2012). The human rights approach to social protection. Ministry For. Affairs1, 172. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/256027984_The_Human_Rights_Approach_to_Social_Protection

34

UNSD Group (2022). Operationalizing Leaving No One Behind. UNSD Group. Available online at: https://unsdg.un.org/sites/default/files/2022-04/Operationalizing%20LNOB%20-%20final%20with%20Annexes%20090422.pdf

35

Varghese C. Kumar S. S. (2022). Marginality: a critical review of the concept. Rev. Dev. Chang.27, 23–41. doi: 10.1177/09722661221096681

36

von Braun J. Gatzweiler F. W. (2014). Marginality: Addressing the Nexus of Poverty, Exclusion and Ecology, 1st Edn. Heidelberg, New York, NY and London: Library of Congress. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-7061-4

37

Whelan C. T. Maitre B. (2010). Identifying economically vulnerable groups as the economic crisis emerged. Econ. Soc. Rev.41, 501–525.

38

Williams D. S. Costa M. M. Sutherland C. Celliers L. Scheffran J. (2019). Vulnerability of informal settlements in the context of rapid urbanization and climate change. Environ. Urban.31, 157–176. doi: 10.1177/0956247818819694

39

Zarowsky C. Haddad S. Nguyen V. K. (2013). Beyond ‘vulnerable groups': contexts and dynamics of vulnerability. Glob. Health Promot.20, 3–9. doi: 10.1177/1757975912470062

40

Zebardast E. (2006). Marginalization of the urban poor and the expansion of the spontaneous settlements on the Tehran metropolitan fringe. Cities23, 439–454. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2006.07.001

41

Zerbo A. Delgado R. C. González P. A. (2020). Vulnerability and everyday health risks of urban informal settlements in Sub-Saharan Africa. Glob. Heal. J.4, 46–50. doi: 10.1016/j.glohj.2020.04.003

Appendix A

Table A1

| Basic amenities and infrastructure | Specific aspects recommended for improvement |

|---|---|

| 1. Water | • Improve the condition of water pipes; • Upgrade all water systems; • Build more water points and provide more water tanks; • Provision of affordable water to every household. |

| 2. Healthcare | • Improve drug management and adequacy of drugs; • Improve conditions of health facility; • Ensure there are enough health facilities with adequate service providers; • Affordable medical cover to everyone; • Expansion of public hospitals to offer more services • Pay community health promoters/workers; • Age and disability friendly facilities; • Government to build more public facilities; • Install a backup for electricity in health facilities; • Collaborate with the government as a community, and well-wishers can aid in the provision of free health service for PWD, older persons and people with chronic diseases; • Public health facilities to operate for 24 h. |

| 3. Housing | • Renovation household structure and housing standards; • Ensure security of land tenure; • Ensure government provides the residents with title deeds; • Build houses for street children; • Stakeholders to come up with mechanisms to ensure affordable houses; • Government to upgrade houses from mud and iron sheets to stone buildings; • Landlords should ask for reasonable house rent. |

| 4. Education | • Increase availability of reading materials and conditions of school facilities; • Construction of more schools; • Construct more ECDs, TVETs, and special needs schools and institutions; • Build more public schools with playing grounds; • Designate playing grounds for children in the community and in school; • MOE to employ enough teachers, expand classrooms, and provide stationery; • Improve education standards; • Create awareness on early pregnancy and drug addiction. |

| 5. Sanitation | • Renovation of toilets; • Construction of sewage system; • Ensure government construct more public toilets; • Every plot should have a toilet; • More toilets in the community and no corruption from leaders. |

| 6. Security | • Ensure curfew regulations are observed and individuals respect each other; • Ensure the government builds enough police stations with adequate staff; • Employment of skilled security personnel; • The Nyumba kumia initiative to be empowered to take charge; • Help unemployed people start businesses for themselves; • Help street children to attend school; • Take street children to rehabilitation and empower them; • Stop corruption and bribery; • Create employment for the youth; • Security lights should be increased. |

| 7. Garbage | • Provide a specific dumping place for the community; • County government to provide dustbins and collection centers; • Ensure fair recruitment of youth in waste programs; • Facilitation of transport of waste to the dumping site; • Find a central place for dumping and equipment for garbage; • Government to provide a dumping site; • Strengthen Police reforms monitoring garbage collection; • Government to ensure proper disposal of wastes and organize clean ups; • Designate a waste disposal site; • Create platforms to nature talents, e.g., sports; • Ensure daily collection of garbage. |

| 8. Electricity | • Ensure all houses have tokens; • KPLC to supply power to all houses; • Ensure KPLC supplies affordable electricity; • Government to provide electricity to every household at affordable price; • Improve on how to connect electrical wires; • Install electricity with tokens and eliminate illegal connections leading to fire outbreaks; • Kenya to take over and stop “Mulika Mwizi” illegal connections. |

| 9. Conflict | • Solving disputes without bribery; • Form community committee and enhance existing committees; • Create counseling centers locally; • Nyumba kumi should be strengthened to stop corruption and tribalism; • Chief offices to have mediation committees; • Stop corruption and bribery when solving cases; • Gender discrimination to stop. |

| 10. Transport | • Improve the conditions of the roads; • Government to build quality roads and access routes for ambulances and fire vehicles; • Government to construct feeder roads. |

Specific priority aspects recommended for improvement as a result of lack of basic amenities.

aNyumba Kumi “is a community policing initiative in Kenya. The name itself translates from Swahili to” 10 households.

Summary

Keywords

2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), marginalized and vulnerable individuals and groups (MVGs), urban informal settlements, Kenya, community driven approach

Citation

Chumo I, Kabaria C and Mberu B (2025) Social mapping of marginalized and vulnerable groups in urban informal settlements: a participatory action research approach. Front. Sustain. Cities 7:1693073. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2025.1693073

Received

26 August 2025

Accepted

15 October 2025

Published

12 November 2025

Volume

7 - 2025

Edited by

Prudence Khumalo, University of South Africa, South Africa

Reviewed by

Lorenzo De Vidovich, Ricerca sul Sistema Energetico, Italy

Mihai S. Rusu, Lucian Blaga University of Sibiu, Romania

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Chumo, Kabaria and Mberu.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ivy Chumo, ivychumo@gmail.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.