Abstract

Introduction:

Research has highlighted the importance of addressing air pollution in cities. Despite the emergence of various environmental strategies in developed contexts, implementation and research related to air quality management frameworks and clear air action plans in the Global South, and in the Arab region, is limited. In Jordan, current air quality management efforts are primarily constrained to monitoring ambient air quality. Accordingly, this research examines the barriers to implementing Clean Air Zones (CAZs) in Amman, Jordan.

Methods:

The methodology utilizes document analysis and semi-structured interviews with city planning and air quality management stakeholders in the city.

Results:

An assessment of current environmental, urban, and transportation action plans indicates that clean air strategies are not a priority within city planning processes and improvements to air-quality are mainly framed as a potential co-benefit of various climate adaptation and environmental strategies. Moreover, targeted place-based air quality interventions and action plans, such as CAZs, are limited. Interview findings illustrate how current pedestrian and public transit infrastructure in the city significantly impedes the implementation of CAZs' vehicle restriction measures. Other barriers include the potential lack of public support of vehicle restrictions, economic vulnerability of residents, limited public awareness of air pollution, and lack of technical and financial capacity of local authorities to implement diverse CAZ measures.

Discussion:

The outcomes of this study offer valuable lessons to urban planners and local authorities considering various clean air strategies in developing contexts. The study highlights the need to further explore clean air management and action planning in cities facing similar conditions to Amman, particularly within developing and resource constrained contexts.

1 Introduction

Over the years, air pollution in urban areas has increased due to extensive urbanization, high energy consumption rates, expansive industrial activities, and increasing vehicle numbers in cities (Vallero, 2014; Bai et al., 2018; Tiwary and Williams, 2018; Lu et al., 2021). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), air pollution poses significant risks to the majority of urban populations including respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, mental and neurological issues, birth defects, and increased mortality rates [World Health Organization (WHO), 2024a]. In 2019, the total ambient air pollution attributable deaths were 4,210,126 [World Health Organization (WHO), 2024a]. In the Eastern Mediterranean Region1, an estimated of 90 people per 100,000 populations (age-standardized) die each year due to causes attributable to ambient air pollution [World Health Organization (WHO), 2024b]. Public health assessment of diseases caused by air pollution indicate the prevalence of communicable diseases in developing regions (including African, South-East Asia, and Mediterranean regions) in comparison to non-communicable diseases in the Americas, Europe, and Western Pacific Regions [World Health Organization (WHO), 2024a].

In response, various air quality standards to reduce air pollution in cities have been developed (Joss et al., 2017; Jafari et al., 2021). In the United States, the Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) established the National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) which set limits on six criteria air pollutants such as carbon monoxide (CO), lead (Pb), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), ozone (O3), and particle matter (PM) [United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), 2024]. To enforce NAAQS, a State Implementation Plan (SIP) is developed and includes various programs and policies to reduce air pollution in American cities [United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), 2025]. In Europe, the Auto-Oil I Program launched in 1990 aimed to reduce emissions from the transportation sector in European cities (Friedrich et al., 2000; Dyrhauge and Rayner, 2023). Similarly, in the United Kingdom (UK), the Expert Panel on Air Quality Standards (EPAQS) was established in 1991 to recommend air quality standards to the UK government based on the latest scientific evidence [Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA), 2006]. Such standards are the foundation for the development of effective management of ambient air pollution.

To comply with national and local ambient air quality standards, countries and municipalities are expected to develop and implement air quality management frameworks, strategies, or actions plans. Emissions related to the transport sector are the lead contributor to air pollution. As such, the majority of solutions proposed aim at reducing traffic-related emission. This includes National Air Quality Strategies, Local Air Quality Management programs, Electronic Road Pricing, congestion pricing, Low Emission Zones (LEZs), Zero-Emission Zones, and Clean Air Zones (CAZs) (Fenger, 1999; Gulia et al., 2015; Fowler et al., 2020; Jafari et al., 2021).

Low Emission Zones are widely implemented in Europe and are in some instances referred to as environmental zones or Limited Traffic Zones (LTZs) (Wolff, 2014; Holman et al., 2015; Ku et al., 2020). The first LEZ was implemented in Stockholm, Sweden and primarily focused on limiting heavy-duty diesel vehicles' access to specific geographical zones within the city through diverse pricing schemes (Ku et al., 2020). Globally, over 300 LEZs have been implemented and vary by size, scope, and pricing. While research indicates the positive contribution of LEZs to improved air quality (Malina and Scheffler, 2015; Flanagan et al., 2022), some scholars indicate potential shortcomings of LEZ that should be considered. For example, (De Vrij and Vanoutrive 2022) argue that LEZs can result in social exclusion by limiting opportunities for social interaction with friends and relatives. Similarly, studies indicate that LEZs increase financial burdens on low-income residents (Rashid et al., 2021; De Vrij and Vanoutrive, 2022). Significantly, some studies indicated mixed results on the role of LEZs in reducing air pollution due to limited consideration of confounding factors (Holman et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2023). Researchers have also highlighted the importance of examining public perception and acceptance of LEZ policy prior to implementation (Mebrahtu et al., 2023).

To expand efforts in air quality management, the United Kingdom introduced the concept of Clean Air Zones (CAZs). A CAZ is a defined as a “an area where targeted action is taken to improve air quality and resources are prioritized and coordinated in order to shape the urban environment in a way that delivers improved health benefits and supports economic growth” [Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA), 2022]. CAZs aim to reduce public exposure to air pollutants by implementing diverse measures to exclude and minimize all pollution sources and improve air quality [Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA), 2022]. In addition to charging zones, the CAZs frameworks encourages local authorities to consider local measures, or non-charging clean air zones, that ensure compliance with air quality standards.

Despite their potential importance, applications of LEZs and CAZs in developing countries, and the Arab region, have been limited (Shahbazi et al., 2019; Al-dalain et al., 2024). According to the WHO's 2016 urban air quality database update, 98% of cities in developing countries with a population of 100,000 or more do not comply with WHO standards (World Health Organization (WHO), 2016). While some attempts have emerged in Tehran, Iran, and Cairo, Egypt, overall compliance with air quality standards and implementation of diverse clear air strategies are a significant challenge to public health concerns in developing contexts.

1.1 Air quality management in Amman, Jordan

Amman is the capital city of Jordan and the largest city in the country. The Department of Statistics estimated that Amman's population in 2024 is 4,920,100 which is approximately 42 percent of the total population of Jordan [Department of Statistics (DOS), 2024]. The GAM projects that by 2030, Amman's population will grow at a pace of roughly 1.8 per cent annually. The metropolitan area of Amman is 7,579 square kilometers with a population density of 649.2 per square kilometer [Department of Statistics (DOS), 2024].

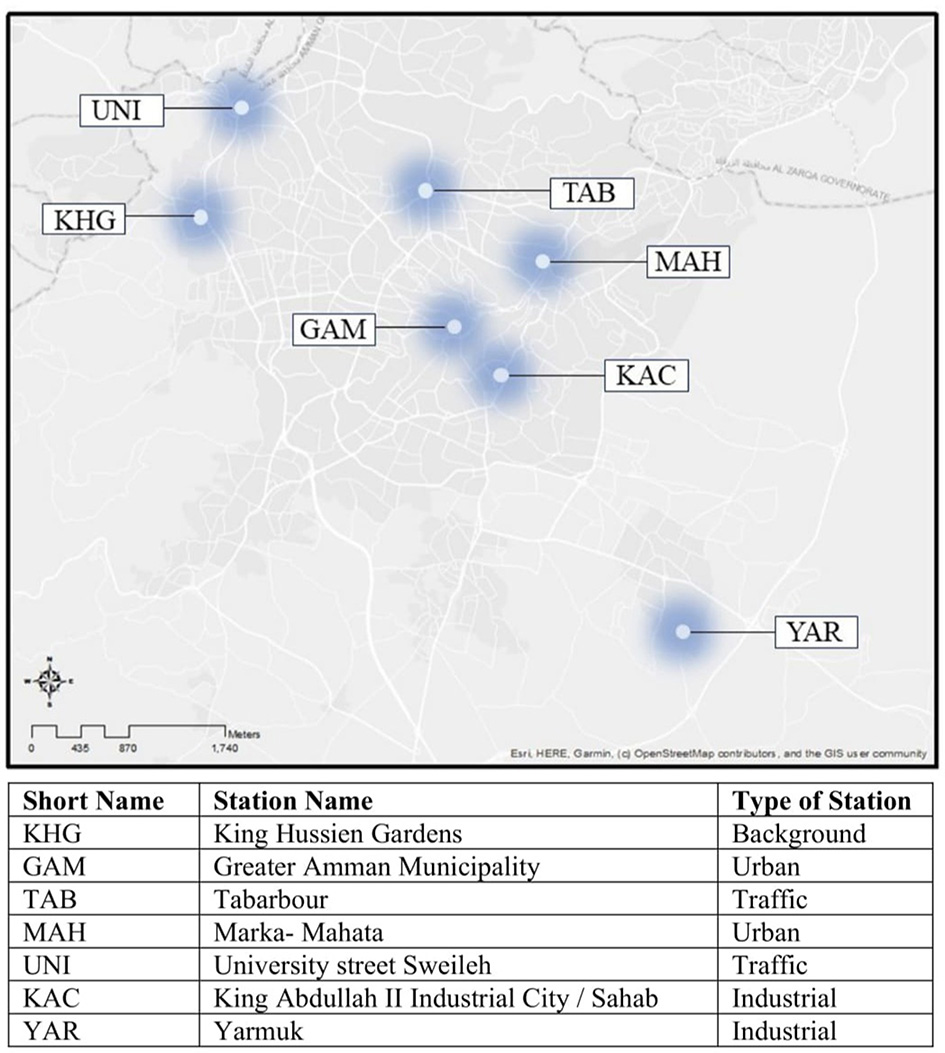

Following the Environmental Protection Law No. 6 of 2017 and the Air Protection Bylaw No. 28-2005, the Ministry of Environment (MoE) monitors and measures Jordan's ambient air quality and pollutant concentrations (Ministry of Environment, 2021a). The process compares collected measurements with the limits stipulated by the Jordanian Standard No. 1140/2006 for ambient air quality to monitor any change or excess in concentrations of pollutants and identifies the appropriate measure in the event of its occurrence (Ministry of Environment, 2021a). The MoE publishes an Annual report for monitoring ambient air quality that aims to assist decision-makers in determining the necessary and appropriate action when developing policies and strategies to improve the quality of air in Jordanian cities. The air monitoring system in Jordan includes 26 monitoring stations, seven of which are located in Amman, as shown in Figure 1 (Ministry of Environment, 2021a). Each station periodically monitors five types of pollutants: PM2.5, NO, NO2, SO2, CO, and O3, providing daily, hourly, monthly, and annual measurements.

Figure 1

Air quality monitoring station locations in Amman, Jordan. Source: Authors.

The 2021 annual “Ambient Air Quality Monitoring Report in Amman–Irbid–Zarqa” issued by the Ministry of Environment (MoE) indicated that Particulate Matter (PM2.5) levels exceeded the annual and daily rates specified in the Jordanian standard specification for ambient air quality No. 2006/1140 (Ministry of Environment, 2021a). According to the MoE, these rates are caused by human activity, particularly the transportation, industrial, and energy sectors, as well as from burning fossil fuels, dust storms, and airborne pollutants (Ministry of Environment, 2021a). The ambient air quality index (AQI) for Amman showed 71.6 percentage of days when AQI was moderate with only 4% of days when the AQI was good in 2021.

Efforts to improve environmental pollution in the city is growing. Numerous strategies have been proposed to promote green economic growth and environment conservation, and reduce greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) to achieve a safe and healthy future for Amman's residents. In 2021, the MoE emphasized “the necessity of working on preparing a national strategy to combat air pollution and monitor the quality of ambient air in the Kingdom or prepare a sectorial strategy for the environment that includes air pollution control and ambient air quality control issues” (Ministry of Environment, 2021a p. 68). Despite this recognition, Amman's air quality management remains predominantly diagnostic rather than intervention-oriented. Existing efforts emphasize pollutant measurement and compliance reporting, with limited translation into place-based emission reduction measures or sector-specific air pollution mitigation strategies. This highlights a persistent gap between policy and implementation.

The city's rapid urbanization, car-dependent mobility patterns, and growing energy demand present significant risks for future air quality deterioration. Proactive interventions, such as Clean Air Zones (CAZs), are therefore vital as preventive urban management tools that can integrate air quality objectives into transport, land-use, and climate policies. However, the literature offers limited empirical examination of the challenges and opportunities associated with implementing Clean Air Zones (CAZs) in developing and resource-constrained cities such as Amman, Jordan. Existing studies largely focus on CAZ experiences in European contexts, where institutional capacity, regulatory enforcement, and technological infrastructure are well-established. In contrast, developing cities face distinct institutional, financial, technical, and social constraints that influence the feasibility and effectiveness of such interventions. Yet, these contextual differences remain underexplored in empirical research.

1.2 Research objectives

Using Amman, Jordan as a case study, this research aims to identify the potential, challenges, and pathways of implementing the CAZ Framework in a developing context. Specifically this research attempts to answer the following research questions:

-

- What are the clean air strategies implemented by decision-makers in Amman, Jordan?

-

- What are the barriers to implementing CAZs in Amman, Jordan?

The adoption of low-emission and low-carbon transport policies is increasing globally. Such policies are widely regarded as crucial to the promotion of sustainable, green, and resilient urban areas. However, despite their well-documented benefits, low-emission policy implementation faces numerous barriers, particularly in developing contexts. Accordingly, this research aims to increase our understanding of low-emission transport policy implementation opportunities and challenges. The results offer valuable insights to stakeholders and policy-makers to consider effective pathways to implementing clean air zone action planning in resource-scarce contexts.

2 Review of related literature

2.1 The clear air zones framework

The CAZ framework is an effort to incorporate diverse actions to support public health and promote economic growth in cities. The framework calls on decision-makers to address sources of pollution and implement context-specific measures to reduce residents' exposure to pollutants [Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA), 2022]. Actions can include restrictions on vehicles entering the specified geographic zones. A CAZ can be a non-charging zone or a charging zone with the overarching goal of transitioning to a low emission economy, thus promoting sustainable city development.

The CAZ framework identified specific outcomes aligned with three main themes: supporting local growth and ambition; accelerating the transition to a low emission economy; and immediate action to improve air quality and health [Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA), 2022]. Across the three themes, any CAZ is subjected to and expected to meet a number of minimum requirements (Table 1) to deliver the improvement in air quality.

Table 1

| No. | Minimum requirement |

|---|---|

| 1 | Be in response to a clearly defined air quality problem, seek to address and continually improve it, and ensure this is understood locally |

| 2 | Have signs in place along major access routes to clearly delineate the zone |

| 3 | Be identified in local strategies including (but not limited to) local land use plans and policies and local transport plans to ensure consistency with local ambition |

| 4 | Provide active support for ultra-low emission vehicle (ULEV)2 take up through facilitating their use |

| 5 | Include a program of awareness raising and data sharing |

| 6 | Include local authorities taking a lead in terms of their own and contractor vehicle operations and procurement in line with this framework |

| 7 | Ensure bus, taxi and private hire vehicle emission standards (where they do not already) are improved to meet Clean Air Zone standards using licensing, franchising or partnership approaches as appropriate |

| 8 | Encourage healthy and active travel |

CAZ Minimum Requirement.

The framework positions CAZs as instruments for delivering long-term economic and environmental co-benefits in cities in addition to improving air quality. This is emphasized in the first theme of the UK CAZ framework “supporting local growth and ambition.” Effective air quality action planning using CAZs should thus incorporate community awareness programs to ensure public support of measures proposed by local authorities [Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA), 2022]. CAZs must also be incorporated in land use planning by examining how current land uses and future development plans impacts air quality within the zone (van Rij and Korthals Altes, 2014; Gheshlaghpoor et al., 2023; Gautam et al., 2024). Moreover, CAZs promote active and low-emission travel and ensure that local authorities lead by example through clean fleet procurements and responsible operations.

To facilitate the transition to a low emission economy, the CAZ frameworks promotes the widespread adoption of ultra-low emissions vehicles (ULEVs) through creative policy reform, financial incentives, active public engagement, the adoption of alternative fuels, and encouraging innovation through public-private partnerships [Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA), 2022]. As such, CAZs are expected to stimulate green technology research and development in the transport sector.

The CAZ framework also emphasizes the importance of immediate actions to improve air quality and health. This is represented by immediate reduction of air pollution levels through measures in pollution hotspots, such as bus stations. Direct emission-reduction actions can include curbing engine idling, regulating construction machinery and diesel generation, and promoting clean domestic heating and cooling technologies [Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA), 2022]. CAZs should also support active travel and behavioral change in residents by enhancing pedestrian infrastructure and ensuring accessible alternative modes of travel (Glazener and Khreis, 2019). Table 2 below illustrates the three themes proposed within the CAZ framework.

Table 2

| Theme | Sub-theme | Action |

|---|---|---|

| Supporting local growth and ambition | Raising awareness and understanding | Engaging local communities |

| Publicizing the zone | ||

| Monitoring | ||

| Delivering local ambition | Making the best use of the local authority role in land use planning | |

| Optimizing traffic management | ||

| Local authority and public sector leadership in fleet procurement and operations | ||

| Joining up Clean Air Zones and Local Air Quality Management | ||

| Improving collaboration and joining up approaches | ||

| Improving the business environment | Working with businesses to recognize and incentivize action | |

| Supporting efficient operation | ||

| Accelerating transition to a low emission economy | Accelerating ultra-low emission vehicle take up | Actively supporting and facilitating the use of ULEVs |

| Providing incentives and benefits for the use of ULEVs | ||

| Improving services and infrastructure | Ensuring local services complement Clean Air Zone standards | |

| Ensuring infrastructure supports Clean Air Zone standards | ||

| Supporting innovation | Developing and evaluating new approaches | |

| Alternative Transport energy sources | ||

| Immediate action to improve air quality and health | Reducing local emissions | Restrict Engine idling |

| Reduce emissions from Non-road mobile machinery | ||

| Reduce emissions sources in Ports | ||

| Reduce emission from generators | ||

| Reduce emission from stoves and wood burners | ||

| Encourage use of low NOx boilers | ||

| Encouraging healthy and active travel | Raising awareness of the options | |

| Making active travel safer and easier | ||

| Encouraging cleaner vehicles | Improving existing vehicles | |

| Access restrictions |

CAZ themes.

Source: [Adapted from Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA), 2022].

2.2 CAZ planning and implementation barriers

The planning and implementation of low-emission zones is a complex process and requires coordination between decision-makers in multiple sectors (Holman et al., 2015). Despite the increasing adoption of CAZs and LEZs as air quality management and transport policies, empirical research that examines the barriers to their implementation, particularly in the developing contexts, is limited (Knamiller et al., 2024). Nevertheless, studies that examined barriers to the development and implementation of various sustainable and green transport policies can offer crucial insights.

In relation to climate policy within the transport sector, Gössling et al.'s (2016) qualitative interviews with policy-makers identified a number of barriers to transport policy-making in the European Union. The study illustrated internal and external barriers to transport climate mitigation policies, including a lack of consensus on climate goals, lack of coordination between agencies, limited data on transport-related GHG emissions, insufficient forecasting tools to assess success of mitigation strategies, and weak leadership on climate migration within the EU transport sector (Gössling et al., 2016; Broaddus, 2020). (Lah 2015) argued that policy packaging is crucial to achieve low-carbon transport. Policy-makers should avoid applying transport measures in isolation but rather a combination of measures and local actions that collectively work to reduce greenhouse gas emissions (Lah, 2015; Broaddus, 2020).

In their study of barriers to the development of green public transportation in Vietnam, (Nguyen Thi Bich and Le Dinh 2024) argue that the lack of charging infrastructure for electric vehicles (EVs) cannot support the proposed scale-up of EVs. Their study also suggests a significant gap between the national goal to reduce carbon emissions by 2050 and the existing policy landscape that can achieve this goal (Nguyen Thi Bich and Le Dinh, 2024). Similarly, a lack of consensus between decision-makers at various administrative levels on how to best to transition toward sustainable road transport in rural Finland was a significant barrier (Kirjavainen and Suopajärvi, 2025). (Wan and Zhang 2025) also argue that conceptual ambiguities surrounding sustainable transport (related to definitions, measurements, and outcomes) can lead to ineffective policy development and implementation.

Barriers to sustainable transport policies are generally categorized into resource, institutional and policy, social and cultural, legal, side effects, and physical barriers (Vigar, 2000; Banister, 2005; May et al., 2006; Jelti et al., 2023). In their assessment of 61 sustainable transport policy, resource barriers represented by the availability of financial and physical resources were the most common barrier (Banister, 2005). This was followed by institutional and policy barriers represented by lack of coordination between stakeholders, conflict with other urban and transport policies, distribution of legal authority to implement measures, and a lack of qualified personnel (Banister, 2005). Public acceptance and support of proposed measures was also a significant barrier. Table 3 below illustrates the most common barriers to sustainable transport policies identified within the literature.

Table 3

| Barrier category | Short description | Example in CAZ planning and implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Resource | Lack of funding or resources needed to implement measures | Limited funding for air quality monitoring infrastructure |

| Institutional and policy | Poor coordination or conflicting priorities between authorities | Lack of coordination between municipal, regional, and national agencies; conflicting climate and economic goals |

| Social and cultural | Public support for the measures | Lack of public support to vehicle charges or restrictions due to increased financial burdens on residents or lack of alternatives mode of transport |

| Legal | Laws or regulations that restrict implementation of measures | National-level legislation may limit local authorities' ability to enforce vehicle restrictions or collect fines within CAZs. |

| Side effects | Negative impacts on other systems or zones | Displacement of traffic and pollution to adjacent areas not covered by the zone (boundary effects) |

| Physical | Physical limitations related to urban form such as space, layout, or terrain | Existing road layouts or lack of space complicates the installation of necessary signage, monitoring cameras, or creating diversion routes |

Barriers to sustainable transport policy implementation.

Source: (Adapted from Banister, 2005).

Regarding barriers to low-emission transport policies, current literature explored issues related to public support and acceptance of EVs and LEZs, poor legislative frameworks, potential social exclusion of low-income and vulnerable populations, limited public transport systems, competing and counterproductive transport policies, lack of trust in public authorities, and limited information on LEZs' and CAZs' impact on air pollution (Peng and Bai, 2023; Jiménez-Espada et al., 2023; Rashid et al., 2021; De Vrij and Vanoutrive, 2022; Mebrahtu et al., 2023, 2025). For example, a policy paper assessing the possibility of applying LEZs in Egypt argued that Low-Sulfur diesel fuel alternatives supported by a national strategy and standards for cleaner fuels and vehicles, improvement in vehicle monitoring and data management, safety-net measures for vulnerable populations, and expansive community engagement are key to the introduction and implementation of vehicle-emission control (El-Dorghamy and Attia, 2021). The researchers argue that the success of LEZ implementation also relies on prerequisite or parallel measures, such as improved land use planning, preservation of public and green space, pedestrian infrastructure development, and reinforcement of community participation in transport and urban planning processes (El-Dorghamy and Attia, 2021).

In Turkey, fast urbanization and consequent increased mobility rates in urban areas was a significant barrier to low-carbon transport policy development (Tuydes-Yaman et al., 2024). On the other hand, research in Poland emphasize that social acceptance of LEZs is required so that changes in mobility behaviors that are necessary to ensure improve air quality conditions occur (Kowalska-Pyzalska, 2022). Other studies indicate that awareness of air pollution and level of environmental concerns impacts public support of LEZs in Jakarta, Indonesia (Rizki et al., 2022).

3 Materials and methods

This study employs an exploratory qualitative research design to explore the opportunities and barriers to implementing the CAZ framework in Amman, Jordan. Qualitative data consisting of document review and semi structured interview were used in this research. Document review included current environmental reports, strategies, and action plans concerning air pollution in the city. Secondary data from governmental databases such as the Greater Amman Municipality (GAM), the Ministry of Environment (MoE), and the Ministry of Transportation (MoT) was collected (See Table 4). The document review assisted in guiding the questions of the interviews and identifying the main governmental sectors and stakeholders involved in air quality policymaking in Amman. The primary objective of the document review was to explore how air pollution issues are framed and addressed within current environmental, urban, and transportation planning strategies.

Table 4

| No. | Action plans | Year | Publisher | Scale | Sector specific |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | National Green Growth Plan of Jordan NGGP | 2017 | MoE | National | No |

| 2 | Green Growth National Action Plan 2021–2025—Water Sector | 2020 | MoE | National | Yes |

| 3 | Green Growth National Action Plan 2021–2025—Agriculture Sector | 2020 | MoE | National | Yes |

| 4 | Green Growth National Action Plan 2021–2025—Energy Sector | 2020 | MoE | National | Yes |

| 5 | Green Growth National Action Plan 2021–2025—Transport Sector | 2020 | MoE | National | Yes |

| 6 | Green Growth National Action Plan 2021–2025—Waste Sector | 2020 | MoE | National | Yes |

| 7 | Green Growth National Action Plan 2021–2025—Tourism Sector | 2020 | MoE | National | Yes |

| 8 | The National Climate Change Adaptation Plan of Jordan 2021 (NAP) | 2021 | MoE | National | No |

| 9 | Build-the-Foundation Strategy: Environmental Education for Sustainability (EEfS) | 2021 | MoE, UNDP | National | Yes |

| 10 | The National Climate Change Policy Of The Hashemite Kingdom Of Jordan 2013–2020. | 2022 | MoE, UNDP | National | No |

| 11 | Jordan National Urban Policy | 2024 | MoE, UN-Habitat | National | No |

| 12 | National Climate Change Health Adaptation Strategy And Action Plan Of Jordan 2024–2033 | 2025 | MoH | National | Yes |

| 13 | Transport and Mobility Master Plan for Amman | 2010 | GAM | GAM | Yes |

| 14 | Amman Resilience Strategy. | 2017 | GAM | GAM | No |

| 15 | Amman Climate Plan A Vision For 2050 Amman | 2019 | GAM | GAM | No |

| 16 | Amman Green City Action Plan (GCAP). | 2021 | AECOM | GAM | No |

Environmental action plans and strategies.

Source: Authors.

3.1 Semi structured interviews

Semi-structured interviews with air quality stakeholders from various sectors were conducted to identify the barriers of implementing a CAZ framework in Amman. Thirty-five interviews were conducted in a period of 2 months. Stakeholders were recruited based on their involvement in environmental management and planning issues in the city. A purposive sampling strategy was employed to identify participants with direct or indirect involvement in air quality management and urban planning in Amman. The diversity of the sample reflects the multi-sectoral nature of Clean Air Zone (CAZ) planning, as outlined in the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) (2022) framework. Thus, to capture a comprehensive picture of the institutional landscape shaping air quality management and potential CAZ implementation in Amman, stakeholders representing the transportation, environment, urban planning, health, sustainable development, energy, and green building sectors were recruited (see Table 5). The interview guide was structured into two main themes, starting with addressing demographic information and experience with air quality management in Amman, followed by discussing the barriers of implementing CAZs in the capital.

Table 5

| No. | Sector | Institution category | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public | Non-governmental | Public-private | Academia | Private | Research | |||

| 1 | Transportation | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| 2 | Environment | 6 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 12 |

| 3 | Regional/Spatial Urban Planning | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| 4 | Health | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| 5 | Sustainable Development | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 6 | Energy | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 7 | Green Building/Business Environment | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Total | 11 | 11 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 35 | |

Semi-structured interview participants.

Source: Authors.

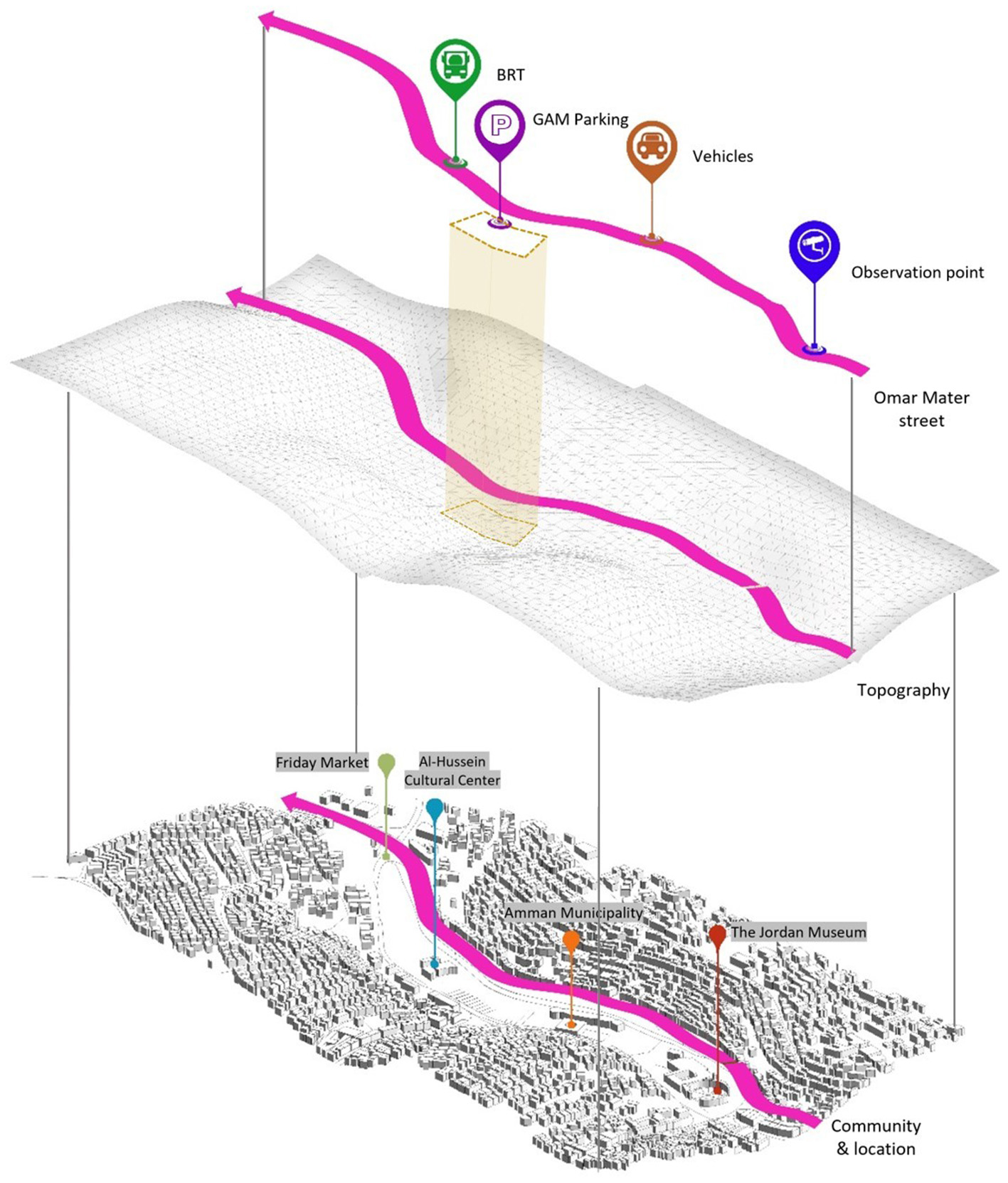

To facilitate discussion on barriers to Clear Air Zone implementation, a fixed-box simulation of vehicle restriction measures was conducted on Omer Mater Street in Amman. The site was selected due to its controlled configuration, proximity to GAM's air monitoring station, and availability of vehicle count data (see Figure 2). Although the fixed-box model provides only simplified estimates of pollutant dispersion, it offers a cost-effective and rapid means of illustrating potential reductions in PM2.5 and CO concentrations under vehicle restriction scenarios (Collet and Oduyemi, 1997; Vallero, 2014; Khan and Hassan, 2020).

Figure 2

Omer Mater Street simulation study location. Source: Authors.

Integrating this simulation into interviews proved methodologically useful because it grounded abstract discussions in a concrete and localized case. Participants could visualize the impacts of a CAZ vehicles restriction policy on a familiar street, which stimulated more informed and contextually relevant responses. This approach also encouraged participants to critically evaluate the intersection of technical, institutional, and social dimensions of implementation, revealing insights that may not emerge from standard interview questions. The simulated case study created a discursive space where planners, policymakers, and experts could test ideas, challenge assumptions, and co-produce knowledge on the applicability of CAZ strategies in Amman.

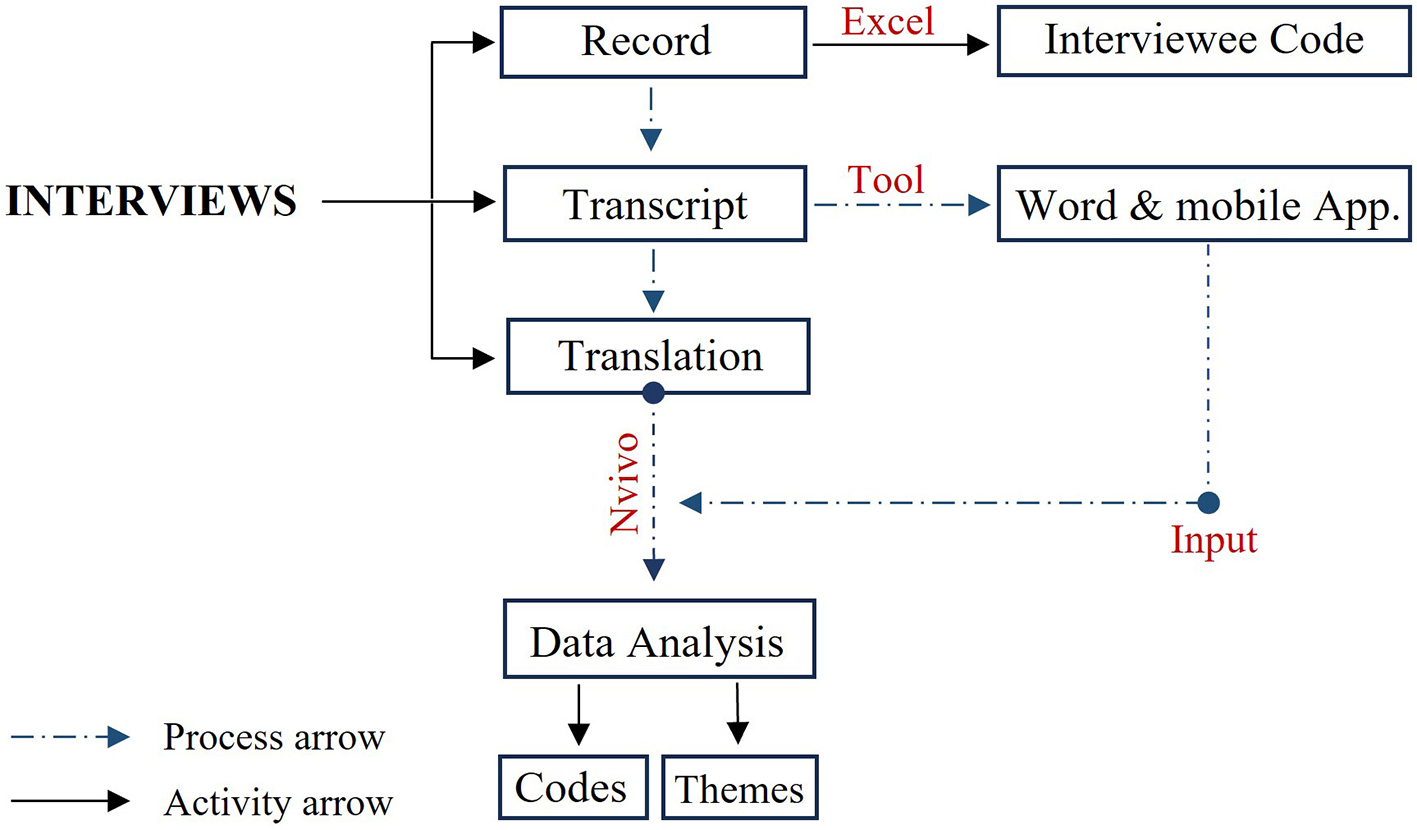

Thematic analysis was used to analyze the interview data (Guest et al., 2012; Braun et al., 2014; Sheydayi and Dadashpoor, 2023). Themes were generated using an inductive approach and a coding framework was developed around this. The qualitative analysis software NVivo was used to analyze data to reveal patterns and emerging themes within the qualitative data (see Figure 3). Thematic analysis was employed because it allows for systematic identification of patterns and meanings across diverse stakeholder perspectives (Braun and Clarke, 2006; Guest et al., 2012; Braun and Clarke, 2019). This method aligns with the exploratory nature of the research, which sought to uncover the institutional, technical, and social dynamics influencing the feasibility of CAZ implementation in Amman. Thematic analysis also allows for both inductive theme generation and deductive interpretation, integrating locally emergent insights with established conceptual frameworks. In this regard, the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) (2022) CAZ framework and Banister's (2005) work on barriers to sustainable transport policy implementation were employed as analytical lenses to guide theme interpretation and situate findings within broader theoretical and policy debates.

Figure 3

Interview data analysis process. Source: Authors.

4 Results

4.1 The landscape of air quality management in Amman, Jordan

To understand the context of air quality management in Jordan, and in Amman specifically, the analysis explored how various sectors address air pollution issues. This process helps in contextualizing if, and which, clear air strategies in the city are prioritized by decision-makers in the city. The environmental sector plays the most visible role, but largely through formal procedures that remain fragmented. For example, protection measures are often limited to environmental impact assessments of industrial activities, incentive schemes for industries and large commercial development activities, and air quality standard-setting. Similarly, consultation processes are restricted to research projects or advisory studies and partnerships with local administration to implement various environmental projects that rarely translate into concrete action plans. As one interviewee from the Royal Scientific Society (RSS) noted, “our role in air pollution is limited to conducting studies on air pollution resulting from factories and making recommendations to the authorities” without clarity on whether these recommendations are actually implemented.

On the other hand, control functions are limited to applying laws and standards, enforcement by the environmental police and Licensing and Inspection Directorate, monitoring land use licenses, and censoring factories' chimney stack emissions. One of the stated goals of the environmental sector is to align with international standards such as ISO 14001 and ISO 50001 which promote air quality improvements in cities. However, this alignment often remains symbolic, with limited evidence that these frameworks are systematically integrated into national or municipal policies.

The energy sector plays a role in air quality management primarily through measures aimed at improving efficiency and diversifying energy sources. Policies encourage the adoption of solar PV farms, solar water heaters, and decentralized energy systems, while also setting minimum performance standards for appliances and promoting household energy conservation. Incentives are further provided for factories and heavy industries to transition toward greener practices. These initiatives contribute to reducing emissions, though they are generally framed within the broader goals of energy security and economic modernization rather than as explicit air quality strategies.

In the health sector, engagement with air pollution issues has been more limited. An interviewee who worked in the World Health Organization (WHO) mentioned that their air quality management role includes monitoring exposure levels, conducting epidemiological studies, and providing recommendations to the Ministry of Health in line with WHO guidelines. An interviewee in the Royal Health Awareness Society (RHAS) clarified that diseases linked to outdoor air pollution do not fall within their mandate. Indeed, participants pointed out that work related to outdoor air pollution in this sector is scarce and as emphasized by one participant “unfortunately, these research topics do not exist in Amman” (Environmental engineer, regional consultant, World Health Organization), highlighting the scarcity of sustained research and programming in this area.

The document review also showcases sporadic emphasis on air quality issues in national and local environmental action plans and strategies. Specifically, air quality is mainly framed as a potential co-benefit of various adaptation and environmental strategies. For example, at the national level, implementing actions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) is suggested to improve air quality (Ministry of Environment, 2017, 2021b). Thus, national action plans emphasize the need to establish advanced systems to monitor greenhouse gases, which could support the tracking of air pollutants. Similarly, sectoral national plans emphasized that green investments in the transportation and waste sector (e.g., EVs, bus rapid systems, and recycling of solid waste) will lead to air-quality co-benefits (Ministry of Environment, 2017, 2020a,b). At the same time, air pollution is identified as a quantifiable externality within the Cost-Benefit Analysis for green growth projects proposed in the country. This suggests that policymakers recognize the importance of air quality and thus assign an economic and social value to air pollution, including the potential costs when air pollution is not addressed in proposed projects, and the benefits when mitigated (Ministry of Environment, 2017). National Green Growth Action plans within diverse sectors address air quality issues in similar patterns (see Table 6).

Table 6

| Sector | Air pollution strategies | Relevance to air quality |

|---|---|---|

| Transport (Ministry of Environment, 2020a) | - Promotion of BRT, non-motorized transport, and rail - Introduction of electric and hybrid vehicles - Improved vehicle inspection and emissions standards - Fuel quality improvements (e.g., sulfur content) - Integration of air quality data in transportation planning | Directly reduces emissions from vehicles and transport infrastructure |

| Waste (Ministry of Environment, 2020b) | - Landfill gas capture and energy use - Waste-to-energy systems (biogas, anaerobic digestion) - Elimination of open Waste burning - E-Waste and hazardous Waste regulation (EPR system) | Targets key pollution sources like landfill gases, burning waste, and toxic e-waste |

| Energy (Ministry of Environment, 2020c) | - Expansion of solar and wind energy - Energy efficiency in buildings and industry - Transition from heavy Fuel oil to cleaner fuels (LPG, natural gas) | Reduces emissions from fossil fuel combustion in power generation |

| Agriculture (Ministry of Environment, 2020d) | - Promotion of composting over crop residue burning - Reduction of smoke and particulate emissions from open burning | Reduces particulate matter from agricultural burning |

| Water (Ministry of Environment, 2020e) | - Adoption of energy-efficient water treatment and pumping systems - Reduction of energy-related emissions | Indirectly improves air quality by cutting energy demand and emissions |

| Tourism (Ministry of Environment, 2020f) | - Development of eco-tourism strategies - Encouragement of sustainable transport in tourist zones | Improves local air quality in tourist areas through clean mobility |

Air quality strategies proposed in sectoral green growth action plans.

The National Climate Change Health Adaptation Strategy and Action plan (2024–2033) proposed a number of measures that directly address air pollution in Jordanian cities (Ministry of Health, 2025). This includes improving access to real-time air quality monitoring data, introducing new indicators such as the Air Quality Index in adaptation planning, and increasing monitoring of urban areas particularly vulnerable to public health concerns, including high air pollution levels. The strategy also emphasized the importance of collaboration and coordination among various sectors and community engagement and awareness of air pollution risks on public health. Similarly, one policy introduced in the recently published Jordan National Urban Policy, is “improve air quality and mitigate climate change” (UN-Habitat, 2024). The policy makes explicit links between air pollution and transportation, environmental, and land use planning activities in the country. Four initiatives were introduced under this policy including: (1) develop and activate standards for air quality, (2) develop and encourage green/smart infrastructure, (3) support and recognize building innovation, and link land use to transportation to grow around transit, and (4) provide infrastructure for active transportation (UN-Habitat, 2024).

At the municipal level, recent environmental action plans recognize the need for targeted air pollution measures across sectors. For example, the Amman Climate Plan 2019 positions air quality at the intersection of climate mitigation and public health. The plan outlines concreate actions, such as transitioning to low-emission mobility, including electric vehicles and active transportation, expansion of public transit, and adoption of renewable energy [Greater Amman Municipality (GAM), 2019]. The plan also highlights measures within the waste sector such as the capture of landfill methane and the promotion of green waste management. Similar to the national action plan, the Amman Climate Plan calls for a comprehensive air pollutant monitoring system (AECOM, 2021).

Most notably, action plans at the municipal level highlight the role of land use in improving air quality. The Transport and Mobility Master Plan of Amman explicitly links the city's reliance on private automobiles and dispersed land use to air pollution [Greater Amman Municipality (GAM), 2010]. The plan proposes the need to shift to a compact city model that is supported by public transportation, pedestrian infrastructure, and enhanced parking regulations. On the other hand, the Amman Green City Action Plan and the Amman Resilience Strategy, frame air quality management within broader urban sustainability efforts., including the expansion of green spaces in the city [AECOM, 2021; Greater Amman Municipality (GAM), 2017].

Taken together, these findings suggest that the clean air strategies prioritized by decision-makers in Amman revolve around:

-

Transport reforms: improving vehicle standards, expanding BRT and EV adoption, and shifting to public and non-motorized transport.

-

Waste sector reforms: eliminating open burning, capturing landfill gases, and regulating hazardous and e-waste.

-

Energy transition: scaling renewable energy, energy efficiency, and cleaner fuels.

-

Land use and mobility planning: compact city models, pedestrian and transit-oriented development.

-

Air quality monitoring and valuation: advancing monitoring systems, integrating AQI in planning, and recognizing air pollution in economic cost-benefit analysis.

-

Urban greening: expansion of green infrastructure as part of resilience and sustainability strategies.

However, air quality is not prioritized through dedicated, stand-alone policies, but instead emerges as a co-benefit of climate, energy, transport, waste, urban planning, and health initiatives. While this demonstrates cross-sectoral recognition of the issue, it also contributes to a perception of fragmentation and limited follow-through, where clean air is acknowledged as important yet remains a secondary rather than primary urban priority. Stakeholders also indicated that current governmental efforts and action plans are guided by global trends and environmental agreements such as the Paris Agreement and C40 cities network. As such, air quality is not directly in the stakeholders' scope of interest and work. At the municipal and ministry level, interviewees also indicated the impact of leadership in setting environmental priorities in a ministry's or municipality's action plans. For example, if a new minister is appointed, a change in leadership staff typically occurs, and the environmental projects, initiatives, or policies are shaped by the interest or vision of this new leadership. Generally, governmental environmental work is burdened by limited implementation or enforcement of long-term planning.

4.2 Barriers to CAZ implementation

Air quality is highlighted in national and municipal environmental action plans as a significant challenge facing Jordanian cities, however, air pollution is predominantly framed as a co-benefit of broader urban adaptation and green growth agendas. While some of the strategies discussed in the previous section align with the principles of the CAZ framework, targeted place-based air quality interventions and action plans are needed. Therefore, this study examined stakeholder perspectives through a localized case study approach. A fixed-box dispersion model was applied to Omer Mater Street in Amman to estimate the potential effects of vehicle restriction scenarios on local air quality. The model calculated changes in mass concentration (C) and population-weighted exposure (Ep) for two key pollutants, PM2.5 and CO, at three heights levels (10 m, 120 m, and 200 m) and two population exposure buffers (150 m and 1 km). Three vehicle restriction scenarios were tested: a full-day restriction, two-peak-hour restriction, and four-peak-hour restriction.

Across all scenarios, the simulation demonstrated that restricting vehicular access would reduce pollutant concentrations, with the most significant improvements observed at ground level (10 m) and within the 1-km buffer zone, where human exposure is highest. The full-day restriction scenario achieved the greatest reductions, while even limited-hour restrictions produced measurable improvements, particularly during evening peaks. This simulation confirms that a CAZ-type measure could meaningfully improve air quality along congested corridors in Amman, even under modest operational parameters. The objective of this paper was not to showcase or evaluate the fixed-box model results in detail, but to employ the simulation as a reflective instrument during stakeholder interviews. By presenting a localized and data-driven example, the simulation helped participants visualize the potential outcomes of a CAZ intervention and reflect critically on the diverse barriers that would influence its implementation in Amman.

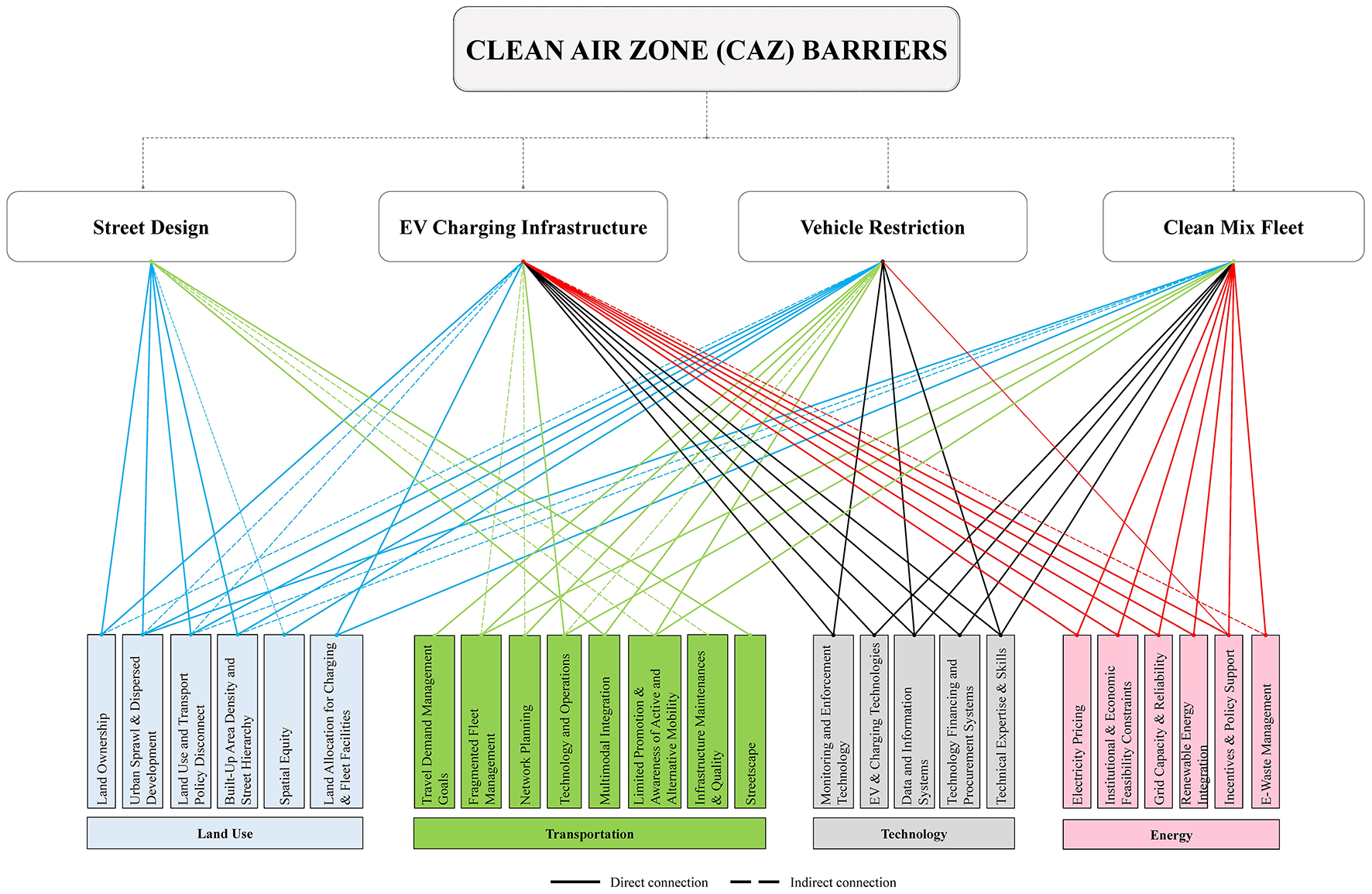

Accordingly, when discussing the implementation of the simulated CAZ scenario on Omer Mater Street, interviewees identified a set of prioritized barriers grounded in the specific requirements of the CAZ framework. These barriers were organized into four main thematic categories: street design and infrastructure limitations, charging infrastructure for low-emission vehicles (LEVs), the transition toward a cleaner public transit fleet, and vehicle restriction measures. Each of these themes reflects a multi-sectoral challenge, requiring coordination among land use, transport, technology, and energy sectors, as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4

Cross-sectoral mapping of Prioritized Clean Air Zone (CAZ) barriers in Amman. Source: Authors.

Stakeholders unanimously agreed that the current transportation infrastructure in Amman significantly impedes the implementation of vehicle restriction measures. This strategy specifically requires efficient pedestrian and public transit infrastructure. While the Amman Bus Rapid System (BRT) can support residents' access to restricted areas, it is still in its infancy, and sidewalk conditions in Amman cannot support large pedestrian mobility. Generally, limitations in public transit in the city and lacking pedestrian infrastructure creates significant challenges to providing alternative access modes to restricted zones.

The stakeholders also showed concern over the potential lack of public acceptance of CAZs, particularly in relation to vehicle restriction measures. This was mainly attributed to three concerns: the lack of public transit options in Amman, the prevailing economic vulnerability of residents, and the limited public awareness of air pollution issues and their impact on public health in the city. The success of any air quality management plan is contingent on public support. However, in connection to the previous barrier, vehicle restriction measures may not gain public support due to the limited availability of transportation alternatives in the city. While some stakeholders viewed the issue as a “lacking culture of walking” in the city, others highlighted resident's heavy dependence on private automobiles as a symptom of Amman's transportation infrastructure.

Similarly, stakeholders emphasized the challenges of restricting older vehicles in CAZs due to residents' economic vulnerabilities. Such measures may force residents to purchase vehicles categorized as Blue (Euro V) and higher or retrofit their old vehicles to comply with acceptable emission levels within a CAZ. The introduction of charging CAZs can also increase financial burdens on the public. Ultimately, vehicle restriction measures that are not accompanied by large public transportation reforms will receive opposition from residents.

The public's potential lack of acceptance of policy instruments to restrict vehicles and improve air quality in the city is also shaped by their awareness of air pollution issues. Generally, to ensure support of air quality measures, the public must first perceive air pollution as a problem. While residents of Amman are aware of traffic congestion as a significant challenge facing the city, the problem is mostly perceived as an accessibility and mobility challenge rather than an environmental concern. Stakeholders from non-governmental sectors particularly emphasized the need to facilitate citizens' access to air quality monitoring data in Amman, particularly in highly congested zones, through mobile applications or various forms of media.

In the assumption of implementing the restriction measure on old vehicles, using observation techniques such as cameras that screen vehicle plates to charge old cars entering restricted areas (CAZ) is technically and financially challenging. Generally, transportation and environmental governmental agencies in Amman lack the technical and financial capacity to implement these forms of vehicle control systems.

Implementing a Clear Air Zone in Amman faces additional challenges from the perspective of electric vehicles (EVs) and charging infrastructure. Although the city's electricity network has the theoretical capacity to support an expansion of charging points, several practical barriers remain. Establishing public charging stations is unattractive to investors due to high taxes and limited incentives. Moreover, public charging points require transformers, adapters, and specialized infrastructure, which are expensive and demand technical assessments of the city network's absorptive capacity. The current urban infrastructure does not yet support such systems, and the lack of prior experience in developing, operating, and maintaining them creates further uncertainty. Added to this is the issue of poor maintenance of existing infrastructure, which limits trust and slows expansion. Despite these constraints, some interviewees noted that if the Greater Amman Municipality (GAM) were to adopt and lead the initiative directly, implementation could be accelerated, particularly as GAM is already pursuing intelligent transportation strategies within its broader smart city plans.

Encouraging a cleaner public transit mix-fleet in Amman presents multiple challenges that complicate the implementation of a Clear Air Zone (CAZ). A large-scale adoption of electric and low-emission public transit vehicles (LEVs) poses significant financial burdens on city transit authorities. Participants discussed challenges due to fragmented ownership of public transit services, high capital requirements, and reduced efficiency of electric buses in Amman's steep topography. As one of the interviewees said, “the electric bus is not powerful enough for the hills of Amman, so that might restrict their range and efficiency.” Another core concerns highlighted is that there is limited technical expertise in Jordan on managing end-of-life batteries from LEVs, raising concerns about safe disposal. Generally, electronic waste management systems in Jordan, and in Amman, are in their infancy, and lack the regulatory frameworks, recycling facilities, and specialized workforce needed to safely process hazardous components. This poses environmental and public health risks if large-scale EV adoption proceeds without parallel investments in e-waste infrastructure.

Although participants have noted that GAM has initiated electric bus integration in the second phase of the Amman BRT system, scaling requires a comprehensive set of financial, technical, and institutional measures to ensure long-term viability. Significant capital investment is needed not only for vehicle procurement but also for establishing charging infrastructures, and maintenance facilities tailored to public transit electric fleets. Technical adaptations must account for Amman's steep topography, which reduces bus efficiency and range, making it essential to consider battery capacity upgrades, regenerative braking systems, or hybrid alternatives. Institutional coordination is equally critical. GAM must work closely with the customs, and licensing authorities to streamline regulations, reduce taxes, and provide targeted incentives for operators. In parallel, driver training programs and maintenance expertise must be developed to address the current gap in skills.

Notably, stakeholders recognized the importance of place-based interventions in promoting air quality within a CAZ. Specifically, participants emphasized that the city faces persistent challenges with particulate matter (PM2.5), which cannot be mitigated through fleet improvements and vehicle restrictions alone. A core issue is the lack of sustainable planning applications that promote active travel and ensure accessibility to vital services and opportunities. Pedestrian infrastructure and equitable distribution of services are thus key to improving air quality and reducing reliance on automobiles.

For example, experts highlighted that municipalities have yet to prioritize reducing Vehicle Hours Traveled (VHT), even though managing the road network and improving traffic flow could directly cut emissions. Walkability plays a significant role in lowering total VHT by reducing reliance on private vehicles for short-and medium-distance trips. However, pedestrian infrastructure in the city is limited, and most vital services are not within walkable distances. Participants highlighted how land use planning in the city is reactive, does not take into account equitable access to services, and is burdened by weak compliance with planning regulations by residents and developers. For example, the Amman Resilience Strategy indicates the need to improve air quality by encouraging residents to shift their travel habits toward walking and public transit. However, interviewees indicated that there are no current efforts to identify pathways to achieve this shift in the city. This illustrates that the effectiveness of a Clear Air Zone (CAZ) cannot be confined to regulating vehicle access alone, but must also be understood within a wider urban planning framework. Indeed, an urban specialist emphasized: “proper planning leads to fewer traffic and air quality problems.”

Building on the matrix in Figure 4, the identified barriers were subsequently restructured to align with Banister's (2005) sustainable transport policy framework. Table 7 below summarizes the key barriers to CAZ implementation in Amman, Jordan categorized into resource, institutional and policy, social and cultural, legal, side effects, and physical barriers. The typology of barriers provides a comprehensive and multidimensional analytical lens for understanding why ambitious transportation and environmental policies, such as CAZs and LEZs, may fail.

Table 7

| Barrier category | CAZ barriers emerging in Amman, Jordan |

|---|---|

| Resource | •High cost of EV buses and fleets •Limited funding for charging infrastructure •Lack of expertise and facilities for battery disposal •Limited capacity for vehicle monitoring systems •Lack of comprehensive air quality data and pollution monitoring systems |

| Institutional and policy | •Air quality seen as co-benefit, not a priority •Fragmented institutions and poor coordination •Frequent leadership shifts •High taxes and weak incentives for private sector •Weak enforcement of planning legislation |

| Social and cultural | •Low public awareness of pollution impacts •Weak acceptance of vehicle restrictions •Dependence on private cars, limited walking culture •Equity concerns for low-income groups |

| Legal | •No clear municipal authority to enforce CAZ •Weak enforcement of existing laws •Lack of binding national regulations |

| Side effects | •Risk of traffic displacement to non-CAZ areas •Risk of excluding vulnerable groups if fees applied |

| Physical | •Poor pedestrian and cycling infrastructure •Weak public transit infrastructure •EV buses underperform on steep terrain of Amman •Limited urban space and urban sprawl |

Key CAZ implementation barriers in Amman, Jordan.

4.3 Toward CAZs planning in Amman

The findings illustrate a number of opportunities to advance clean air planning in Amman, Jordan. Currently, air pollution is perceived as an outcome of larger environmental strategies and action plans, such as promoting green economy and growth and improving climate change resilience. As a result, the city has yet to develop a comprehensive air quality management and clean air strategy that can be used by diverse stakeholders. Moreover, there is limited guidance for stakeholders who want to implement vehicle restriction measures as an air quality management tool in specific, or Clean Air Zone action planning in general. Moving forward, the successful implementation of this measure requires a comprehensive transportation plan that focuses on the pedestrianization of the city and expanding public transportation infrastructure. Transportation planning agencies, such as the Ministry of Transport, the transportation department in the Greater Amman Municipality, Amman's Traffic Control Unit, and the Vehicle Licensing Department also have the responsibility to ensure its transportation plans support and maintain air quality management goals and CAZ measures.

As such, collaborative air quality goal setting between the environmental, public health, and transportation sectors is crucial to facilitate cooperation between stakeholders. This can include meaningful collaborative efforts to identify areas within the transit networks where pollution from vehicle emissions exceeds air quality standards, and ensure proposed transportation projects are compatible with CAZ action planning and align with air pollution reduction goals in the city. Notably, during discussions of the barriers to CAZ implementation, the public health sector and its role were largely absent. This highlights a critical institutional gap in linking air quality management to health outcomes and public wellbeing. Without active engagement from health authorities, efforts to design and justify CAZ interventions remain narrowly framed around environmental or transportation efficiency goals, rather than around improving population health. Integrating the public health sector into CAZ planning is therefore essential to build stronger cross-sectoral accountability, strengthen the evidence base for clean air policies, and reframe air quality as a shared determinant of urban health and equity in Amman.

Public support is also key to the success of CAZ action planning. Local authorities must implement sustained public communication campaigns targeting diverse communities in the city. This includes first providing easy access to air quality monitoring data and information on the potential public health impacts of air pollution. This step can ensure sufficient “perception of the problem” by the public, i.e., air pollution and its connection to transportation and traffic congestions, that is importance to garner public support to any proposed measures.

Regarding vehicles restrictions, early public engagement campaigns can allow decision-makers to adapt feedback from the public and related stakeholders on proposed measures, reduce implementation errors, offer practical guidance to reduce daily exposure to harmful pollutants in highly congested areas, as well as inform the public of the proposed alternative travel options in restricted areas. Overall, a culture of public participation in the decision-making process within CAZ action planning must be promoted and ensured as it can shape a measure's success and can minimize resistance from the public.

5 Discussion and conclusion

This study provides critical insights into the systemic barriers constraining the implementation of Clean Air Zones (CAZs) in Amman, Jordan. The findings reveal that while the CAZ concept offers significant potential for reducing air pollution, its practical application in developing contexts is hindered by structural constraints that differ in some aspects from those in high-income countries.

First, the results highlight that clean air remains a low-priority, cross-sectoral issue, often framed as a co-benefit of climate mitigation, energy transition, or green growth policies rather than a stand-alone policy domain. This framing leads to fragmented implementation and limited accountability, echoing broader patterns observed in Cairo, Tehran, and Ho Chi Minh City, where air quality management has been acknowledged on paper but seldom operationalized into enforceable strategies (Shahbazi et al., 2019; El-Dorghamy and Attia, 2021; Nguyen Thi Bich and Le Dinh, 2024). This indicates a pressing need to reframe air quality as a public health and development priority, linking CAZ measures directly to urban wellbeing and social equity outcomes.

Second, the Amman case underscores the impact of resource and infrastructure constraints on shaping the feasibility of CAZ adoption. High capital costs for electric fleets, limited charging infrastructure, and weak technical capacity for battery recycling reflect structural financial and technological deficits that are common across developing contexts. Such barriers demonstrate why direct policy transfer from European or North American CAZ models is impractical, and why incremental, adaptive approaches such as phased fleet retrofits, or low-cost pedestrianization schemes may represent more viable entry points (Nguyen Thi Bich and Le Dinh, 2024; Peng and Bai, 2023).

Third, the findings reveal that public awareness, social acceptance, and equity considerations are decisive in determining the legitimacy of CAZ measures. In Amman, resistance to vehicle restrictions stems not only from economic vulnerability but also from the perception that air pollution is a mobility issue rather than a public health threat. These dynamics mirror those documented in Bradford and Jakarta, where CAZ and LEZ initiatives faced opposition unless accompanied by strong equity safeguards, viable mobility alternatives, and participatory engagement (Rashid et al., 2021; Rizki et al., 2022; Mebrahtu et al., 2023). This suggests that CAZ policies must be designed as socially inclusive interventions, ensuring affordable access to clean mobility options and embedding citizen engagement at every stage of policy design. At its current state, the public transit system in Jordan does not achieve these objectives, which may result in limited trust and confidence in CAZ policies that claim to ensure access and affordability.

Finally, the Amman case illustrates that the persistent implementation gap is less a matter of technical design and more a question of governance, legitimacy, and adaptive capacity. While technological solutions are available, their deployment is constrained by weak resource bases, limited social trust, and competing developmental priorities. This aligns with arguments in the sustainability transitions literature that emphasize the need for context-specific experimentation and incremental adaptation rather than wholesale adoption of Global North models (Bai et al., 2018; Lah, 2015). CAZ planning in resource-constrained and rapidly urbanizing contexts such as Amman, therefore, must be conceived not as a purely technical exercise but as a socio-political process of negotiation, adaptation, and capacity building.

In sum, this study contributes to the broader literature by showing that CAZ implementation requires a fundamental shift in framing and practice. This includes moving from a narrow focus and discussion on technological transfer to a holistic emphasis on governance, social equity, and adaptive experimentation that aims to reform transportation, urban, and environmental planning frameworks operating in cities. By situating Amman within this discourse, the research underscores that air quality management is not only about reducing pollutants but also about advancing more equitable, resilient, and health-centered urban futures.

5.1 Conclusion

Urban air quality management measures, such as CAZ are gaining increasingly wide interest by local authorities. Despite their potential in improving public health, applications in resource constrained and in developing contexts remain limited. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first paper to explore the concept of Clean Air Zones in Amman, Jordan. In considering the diverse barriers that constrain CAZ implementation in Amman, this study draws a number of recommendations. Its main purpose is to identify the implications for relevant stakeholders that can help address such barriers to air quality management. As such, a number of recommendations emerge, including:

-

- Domestic policy alignment can help overcome institutional fragmentation and regulatory gaps. Ensuring that air quality goals are embedded into transport and land-use planning, and not percieved as co-benefits, is crucial to avoid symbolic commitments without enforcement (van Rij and Korthals Altes, 2014).

-

- Local institutional support is critical for policy continuity and project demonstration. Frequent leadership changes at ministries and municipal departments undermine consistency; stronger cross-agency alliances can reduce policy volatility and promote coherent implementation (Gössling et al., 2016).

-

- Public awareness and acceptance of air pollution as a health threat must be improved. As noted in Bradford and Jakarta, local stakeholder engagement and access to air quality data can build confidence in CAZ measures, foster behavior change, and minimize resistance (Mebrahtu et al., 2023; Rizki et al., 2022).

-

- Stakeholder participation and bilateral exchange between government, academia, and civil society can reduce informational barriers and improve technical design. Experiences from Cairo and Tehran show that CAZ-like interventions succeed when local expertise is mobilized and contextualized (Shahbazi et al., 2019; El-Dorghamy and Attia, 2021).

-

- Financial barriers can be addressed by targeted subsidies, investment incentives, and appraisal methodologies that demonstrate cost-benefits to policymakers. Strengthening local capacity in financial planning, while connecting municipalities with international finance networks, can unlock investment for EV infrastructure and fleet transition (Nguyen Thi Bich and Le Dinh, 2024).

-

- Bridging actors between government, transit operators, and private investors are essential. Brokerage initiatives that link EV suppliers, public transit authorities, and donor agencies can overcome mainstream financing constraints, scale investment, and build municipal capacity for long-term CAZ management (Peng and Bai, 2023).

-

- Urban planning interventions and place-based measures are essential to create the spatial conditions for CAZ effectiveness. Controlled urban growth, equitable distribution of services, pedestrianization, and integration of active travel infrastructure are prerequisites for reducing Vehicle Hours Traveled (VHT) and ensuring viable alternatives to private car use (Glazener and Khreis, 2019; Gautam et al., 2024).

Future research should investigate the multi-dimensional feasibility of Clean Air Zone (CAZ) implementation in cities like Amman. In particular, studies are needed to quantify the public health benefits of air quality interventions, assess the socio-spatial equity implications of vehicle restriction policies and CAZs, and examine behavioral and public perception factors shaping policy acceptance. Additional research should also explore institutional and governance mechanisms that enable coordination between environmental, transportation, and health sectors in air quality management.

Finally, this study demonstrates how air quality simulation methods, such as the fixed-box model, provide stakeholders with a relatively easy, quick, and affordable tool that can also support public and professional discourse on CAZ measures in the city. The simulation results in Omer Master Street were critical in facilitating discussions with relevant stakeholders on the potential pitfalls of vehicle restriction measures. Simulation methods can also be used to promote CAZ measures to the public and potentially improve public acceptance of various air quality policy instruments.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Jordan University of Science and Technology. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The Ethics Committee/Institutional Review Board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants' legal guardians/next of kin because no requested by local legislation and intuitional requirements.

Author contributions

A'E: Investigation, Visualization, Conceptualization, Validation, Software, Project administration, Formal analysis, Methodology, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. YO: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Resources, Project administration, Supervision, Methodology, Conceptualization, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of all interview participants who shared their perspectives and experiences on air quality management and planning in Amman. We also thank the institutions and agencies that facilitated access to environmental reports and policy documents, as well as the academic colleagues who provided valuable comments and guidance throughout the research process.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1.^WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region includes Afghanistan, Bahrain, Djibouti, Egypt, Iran (Islamic Republic of), Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Oman, Pakistan, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Syrian Arab Republic, Tunisia, United Arab Emirates, West Bank and Gaza Strip (Non-Member area), Yemen.

References

1

AECOM (2021). Amman Green City Action Plan. Available online at https://www.amman.jo/site_doc/AmmanGreen2021.pdf (Accessed August 15, 2025).

2

Al-dalain R. Beithou N. Bani Khalid M. Alsqour M. Azzam E. Borowski G. et al . (2024). The implementation of low emission zones in low-income countries: a case study. J. Ecol. Eng.25, 261–268. doi: 10.12911/22998993/193639

3

Bai L. Wang J. Ma X. Lu H. (2018). Air pollution forecasts: an overview. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health15:780. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15040780

4

Banister D. (2005). “Overcoming barriers to the implementation of sustainable transport”. in Barriers to Sustainable Transport. Institutions, Regulation and Sustainability, eds. P. Rietveld, and R. Stough (London, UK: Routledge), 54–68.

5

Braun V. Clarke V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol.3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

6

Braun V. Clarke V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health11, 589–597. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

7

Braun V. Clarke V. Rance N. (2014). “How to use thematic analysis with interview data”. in The Counselling & Psychotherapy Research Handbook, eds. A. Vossler, and N. Moller (London: Sage Publications Ltd.), 183–197. doi: 10.4135/9781473909847.n13

8

Broaddus A. (2020). “Integrated transport and land use planning aiming to reduce GHG emissions: International comparisons”. in Transportation, Land Use, and Environmental Planning, eds. E. Deakin (Oxford, UK: Elsevier), 399–418. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-815167-9.00018-9

9

Collet R. S. Oduyemi K. (1997). Air quality modelling: a technical review of mathematical approaches. Meteorol. Appl.4, 235–246. doi: 10.1017/S1350482797000455

10

De Vrij E. Vanoutrive T. (2022). ‘No-one visits me anymore': low Emission Zones and social exclusion via sustainable transport policy. J. Environ. Pol. Plan.24, 640–652. doi: 10.1080/1523908X.2021.2022465

11

Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA). (2006). Expert Panel on Air Quality Standards. Available online at: http://www.defra.gov.uk/environment/quality/air/airquality/panels/aqs/index.htm (Accessed June 15, 2025).

12

Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA). (2022). Clean Air Zone Framework. Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/air-quality-clean-air-zone-framework-for-england/clean-air-zone-framework (Accessed June 15, 2025).

13

Department of Statistics (DOS) (2024). Statistical Yearbook of Jordan 2024: Population. Available online at: https://dosweb.dos.gov.jo/databank/yearbook/YearBook_2024/Population.pdf (Accessed June 15, 2025).

14

Dyrhauge H. Rayner T. (2023). “Transport: evolving EU policy toward a ‘hard-to-abate' sector”. in Handbook on European Union Climate Change Policy and Politics, eds. T. Rayner, K. Szulecki, A. J. Jordan, and S. Oberthür (Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited), 305–320. doi: 10.4337/9781789906981.00035

15

El-Dorghamy A. Attia M. (2021). Low-Emission Zones (LEZs) and Prerequisites for Sustainable Cities and Clean Air in Egypt, 2021 [Policy Paper]. Cairo, Egypt: Center for Environment and Development for the Arab Region and Europe (CEDARE). Available online at: https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/aegypten/19263.pdf (Accessed June 15, 2025).

16

Fenger J. (1999). Urban air quality. Atmos. Environ.33, 4877–4900. doi: 10.1016/S1352-2310(99)00290-3

17

Flanagan E. Malmqvist E. Gustafsson S. Oudin A. (2022). Estimated public health benefits of a low-emission zone in Malmö, Sweden. Environ. Res.214:114124. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2022.114124

18

Fowler D. Brimblecombe P. Burrows J. Heal M. R. Grennfelt P. Stevenson D. S. et al . (2020). A chronology of global air quality. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A378:20190314. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2019.0314

19

Friedrich A. Tappe M. Wurzel R. K. W. (2000). A new approach to EU environmental policy-making? The Auto-Oil I Programme. J. Eur. Public Pol.7, 593–612. doi: 10.1080/13501760050165389

20

Gautam S. Gautam A. S. Awasthi A. Ramsundram N. (2024). “Urban planning for clean air,” in Sustainable Air. SpringerBriefs in Geography (Cham, Switzerland: Springer), 65–70. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-77057-9_9

21

Gheshlaghpoor S. Abedi S. S. Moghbel M. (2023). The relationship between spatial patterns of urban land uses and air pollutants in the Tehran metropolis, Iran. Landsc. Ecol.38, 553–565. doi: 10.1007/s10980-022-01549-y

22

Glazener A. Khreis H. (2019). Transforming our cities: best practices towards clean air and active transportation. Curr. Environ. Health Rep.6, 22–37. doi: 10.1007/s40572-019-0228-1

23

Gössling S. Cohen S. A. Hares A. (2016). Inside the black box: EU policy officers' perspectives on transport and climate change mitigation. J. Transport Geogr.57, 83–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2016.10.002

24