- 1Department of Architecture and Arts, Hasselt University, Hasselt, Belgium

- 2Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Ardhi University, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

Rapid urbanisation and incremental housing in Dar es Salaam have depleted urban green spaces, leaving many public areas underutilised or privately appropriated. This study, conducted within the Institutional University Cooperation (IUC) between Ardhi University and Hasselt University, examines university–community collaboration (UCC) as a means of transforming such spaces into community-owned and managed green areas. Drawing on 1 year of participatory action research in Sinza D, the study traces how collaboration among researchers, grassroots leaders, and residents evolved through facilitation, reflection, and trust-building. The findings reveal that effective UCC nurtures grassroots leadership, embodied in extended planners, who are local actors mediating between community aspirations and institutional frameworks. These leaders gain legitimacy and adaptive capacity through co-designed and inclusive processes that transform facilitation into shared governance. The study challenges extractive research models and calls for more context-sensitive, enduring collaborations that strengthen local agency in rapidly urbanising African cities.

1 Introduction

Universities and research institutions have been strongly encouraged to produce knowledge that not only advances academic inquiry but also delivers tangible societal benefits (Arnaldo Valdés and Gómez Comendador, 2022; Dobson and Owolade, 2025). This global emphasis on socially responsive research has revived debates on the civic role of universities and the need to reframe research as a collaborative, participatory, and context-sensitive practise (Dobson and Owolade, 2025; Goddard and Vallance, 2011). Higher-education policies increasingly call on institutions to move beyond teaching and consultancy towards partnership-oriented research that supports local development (Arnaldo Valdés and Gómez Comendador, 2022; Dobson and Owolade, 2025). This paper contributes to these debates by examining how UCC in the Global South, specifically in Tanzania, can function as a mediating practise that strengthens community leadership and resilience amid rapid urban transformation.

Across Europe, initiatives such as the European Universities Initiative and the UK’s Civic University Commission have promoted universities as civic anchors, emphasising social responsibility, innovation, and public value (Civic University Commission, 2019; Dobson and Owolade, 2025). Similar reflections are emerging in Africa, where universities seek to redefine their social purpose within constrained governance and economic environments (Chitongo and Zhanda, 2025; Coetzee and Nell, 2018). In Tanzania, the Tanzania Commission for Universities (TCU) encourages outreach and engagement (Busindeli et al., 2024; URT, 2019), yet implementation often remains limited to consultancy work with minimal community participation (Mrema, 2024; Ndimbo and Nkwabi, 2025). This gap highlights the need for more context-specific forms of collaboration that integrate institutional knowledge with local capacities to address complex urban land-use challenges, such as rapid densification, loss of open space, and declining environmental quality.

Previous research by Majogoro et al. (2025a) and Majogoro et al. (2025b) conceptualised grassroots leaders as extended planners, actors such as Mtaa Chairpersons (MC), Mtaa Executive Officers (MEO), Mtaa Committee Members (MCM), and Ten-Cell Leaders (TCL) who mediate between residents and formal authorities. These leaders hold local legitimacy and intimate knowledge of everyday governance but often face technical and procedural constraints when addressing planning conflicts (Majogoro et al., 2025b; Manara and Pani, 2023; Ngowi et al., 2022). This study builds on that concept, clarifying that researchers are not themselves extended planners; rather, they act as mediators who scaffold the work of extended planners through facilitation, documentation, and reflection. By tracing how this mediating role unfolds within a collaborative planning process, the study contributes to understanding how university-based research can strengthen grassroots governance.

The research forms part of the Institutional University Cooperation (IUC) programme, a ten-year partnership between Hasselt University and Ardhi University focused on land-use planning and community resilience (VLIR-OUS, 2025). The case study is located in Sinza D, a planned neighbourhood in Dar es Salaam established in 1974 (Kironde, 1991; Remtulla, 2010). Rapid urbanisation and incremental housing have intensified land-use pressure, diminishing open spaces and greenery (Majogoro et al., 2025a; Majogoro et al., 2025b; Vedasto and Mrema, 2013). One residual open space along a rehabilitated riverbank, covering about 0.35 hectares, became the focal site for this study after flood-protection works in 2020 created new potential for community use. Formerly neglected and unsafe, the area was re-envisioned through collaboration among residents, grassroots leaders, and university researchers as a potential community-managed green hub. The process combined local knowledge with academic facilitation, progressing from an initial idea to a publicly endorsed project, illustrating how participatory reflection can translate shared aspirations into collective action (Dobson and Owolade, 2025; Majogoro et al., 2025a; Majogoro et al., 2025b).

Situated within the broader discourse on UCC, this paper specifically investigates how community leadership emerges through mediated collaboration (Kaufman and Dilla Alfonso, 1997; Parés et al., 2017). It explores the key turning points and processes that marked the formation and consolidation of community leadership in the Sinza D green-space initiative, tracing how residents, grassroots leaders, and university researchers collectively shaped the project over time. In doing so, the study examines the mediating practises performed by the researchers, such as convening, documentation and translation, and legitimation, which enabled these turning points and strengthened the capacity of grassroots leaders to coordinate, negotiate, and sustain the initiative.

To address these questions, the paper draws on two complementary strands of literature: one on UCC and civic universities, which conceptualises universities as collaborators that co-produce public value through socially responsive research; and another on grassroots governance in African cities, which highlights how local leaders act as extended planners mediating urban transformation within institutional constraints. Combining these strands frames collaboration as a relational and iterative process of mediation through which researchers and extended planners co-produce learning, strengthen civic capacity, and enable community-led spatial transformation (Dobson and Owolade, 2025; Goddard and Vallance, 2011; Parés et al., 2017).

The study analyses a series of participatory activities undertaken in the Sinza D green-space initiative to identify the turning points through which collaboration evolved and community leadership strengthened. Each turning point reveals how the roles and relationships among key actors, such as residents, grassroots leaders, and university researchers, shifted in response to emerging challenges and opportunities. Through examining these transformations, the paper traces the evolving patterns of collaboration and the mediating practises, including facilitation, documentation, and legitimation, that enabled coordination, negotiation, and collective learning across the process. The remainder of the paper develops this argument as follows: Section 2 outlines the conceptual framework, linking civic university literature, community leadership, and collaborative planning; Section 3 presents the methodology and case context; Section 4 discusses the empirical findings and key turning points; and Section 5 concludes with the main insights, limitations, and implications for future UCC.

2 University–community collaboration

University–community collaboration (UCC) has gained renewed attention as universities redefine their social purpose within complex and unequal societies. Once viewed primarily as producers of knowledge, universities are now recognised as civic actors capable of contributing to social transformation through engaged scholarship (Goddard and Vallance, 2011; Mrema, 2024). The concept of the civic university (Busindeli et al., 2024; Goddard and Vallance, 2011) encapsulates this paradigm shift, positioning universities as anchor institutions embedded in their local contexts and responsible for generating both social and economic value (Dobson and Owolade, 2025; Goddard and Vallance, 2011). Whilst much of the literature treats UCC as an institutional mission, recent studies highlight the role of researchers as mediators who operationalise collaboration on the ground (Dobson and Owolade, 2025; Ospina and Foldy, 2010). In this relational view, collaboration is not only a policy framework (Benneworth and Jongbloed, 2013; Goddard and Vallance, 2011) but a situated practise shaped by negotiation, trust, and evolving relationships between academic and community actors (Arnaldo Valdés and Gómez Comendador, 2022; Dobson and Owolade, 2025).

Despite its transformative promise, UCC remains constrained by persistent power asymmetries and institutional limitations (Arnaldo Valdés and Gómez Comendador, 2022; Dobson and Owolade, 2025). Universities often control research design, funding, and legitimacy (Mrema, 2024; Ndimbo and Nkwabi, 2025), whilst community actors contribute experiential knowledge that is frequently undervalued (Dobson and Owolade, 2025; Goddard and Vallance, 2011). These imbalances are further compounded by internal hierarchies within communities, where social status, gender, or political ties influence participation and decision-making (Chitongo and Zhanda, 2025; Goddard and Vallance, 2011). As Forester (2006) and Goddard and Vallance (2011) note, participation is inherently political, and effective collaboration requires navigating conflict, mistrust, and competing interests rather than assuming harmony.

Across Africa, universities face these tensions as they attempt to reconcile academic imperatives with social accountability. In South Africa, studies by Chitongo and Zhanda (2025) and Coetzee and Nell (2018) reveal that, although community engagement is firmly embedded within university strategic frameworks, its implementation remains constrained by fragmented institutional structures and limited resources. In Zimbabwe, Chitongo and Zhanda (2025) report that engagement often takes the form of short-term, donor-driven outreach rather than sustained collaboration. In Namibia, Ndimbo and Nkwabi (2025) highlight how performance indicators tied to research output undermine the potential for enduring partnerships. Collectively, these studies reveal a regional pattern: universities aspire to civic engagement but struggle to align institutional incentives, resources, and accountability mechanisms with deeper goals of social transformation (Benneworth and Jongbloed, 2013; Goddard and Vallance, 2011; Mrema, 2024).

In Tanzania, similar contradictions are evident. Policies such as the Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) framework and university outreach mandates encourage stronger community collaboration (URT, 2019), yet practise often remains limited to consultancy work or short-term projects with minimal community participation (Fussy, 2018; Mrema, 2024). In addition, Busindeli et al. (2024) and Mrema (2024) note that bureaucratic rigidity and resource scarcity further hinder meaningful engagement. Inasmuch, the Higher Education for Economic Transformation (HEET) project has further intensified this tension by linking institutional performance to internationally benchmarked research outputs. This approach aligns with the Guidelines for Research and Innovation Awards, which prioritise publications in high-impact international journals, reinforcing a culture where global visibility often outweighs responsiveness to local and community needs (URT, 2023).

To address these challenges, scholars advocate place-based engagement and participatory methodologies that redistribute power and foster mutual learning (Canada et al., 2023; Kindon et al., 2009). Participatory Action Research (PAR) exemplifies this orientation, embedding inquiry within collective processes of reflection and action (Busindeli et al., 2024; Kindon et al., 2009). Rather than assuming balanced participation, PAR acknowledges inequality and seeks to navigate it through iterative negotiation, trust-building, and transparency (Reed et al., 2018). By facilitating collective problem-solving and knowledge co-production, such approaches enable researchers to act as boundary spanners, connecting institutional mandates with community aspirations (Goddard and Vallance, 2011; Parés et al., 2017).

Historically, Tanzanian public universities, most notably the University of Dar es Salaam, played a key developmental role during the post-independence era, aligning higher education with national goals of poverty reduction and self-reliance (Busindeli et al., 2024; Fussy, 2018). This civic orientation weakened under the structural adjustment reforms of the 1980s and 1990s, which redefined universities as revenue-generating institutions (Busindeli et al., 2024; Mrema, 2024). However, renewed attention to sustainability and social innovation has recently revived interest in collaborative models of knowledge production, reconnecting academic expertise with local development challenges (Busindeli et al., 2024; URT, 2019).

Ultimately, UCC represents both an ethical commitment and an epistemic opportunity for universities and researchers. By combining institutional mandates with situated collaboration, universities can move from extractive engagement towards genuinely co-productive and learning-oriented practises (Coetzee and Nell, 2018; Goddard and Vallance, 2011). The experience from Sinza D, Dar es Salaam, where researchers collaborated with extended planners and residents to transform a neglected riverbank into a community-managed green space, illustrates how UCC can turn shared ideas into collective action, strengthening local capacity and reimagining the civic role of universities in rapidly urbanising contexts. The following section builds on this relational understanding of UCC to interpret the community space as a project, a setting where collaboration, leadership, and mediation become materially grounded. This framing links civic-university engagement to grassroots planning practises, providing a conceptual bridge between institutional collaboration and everyday urban transformation.

2.1 Community space as a project

Building on the UCC understanding of community as a relational and situated practise, this section connects these ideas to the notion of community space as a project —a site where collaboration, leadership, and mediation become materially grounded. Community spaces are increasingly recognised as crucial arenas for collective learning, civic participation, and social innovation (Aleha et al., 2023). Emerging in the gaps of formal planning, these spaces demonstrate how residents mobilise local knowledge and shared care practises to reclaim neglected land and create new forms of public value (Aleha et al., 2023; Kaufman and Dilla Alfonso, 1997). Their importance extends beyond physical or recreational functions: they operate as social infrastructures that nurture belonging, dialogue, and collective agency within everyday urban life (Apostolopoulou et al., 2022; Smith et al., 2014).

However, such processes frequently unfold amid tension between formal planning systems and informal community practises. Professional planning often emphasises regulation, spatial control, and risk mitigation (Dovey, 2012; Vedasto and Mrema, 2013), whereas community action evolves through lived experience, relational trust, and collective need (Huybrechts et al., 2024; Qi et al., 2024). In Tanzania, legally protected buffer zones along riverbanks are often re-appropriated by residents as spaces for social interaction and livelihood activities (URT, 2018; Alexander et al., 2024). Over time, these residual areas acquire new meanings, becoming micro-sites of negotiation where competing urban logics, regulations, and everyday adaptations are reconciled through practise (Besha et al., 2024; Vedasto and Mrema, 2013).

To interpret these situated transformations, this study draws on collaborative planning theory, which reconceptualises the planner’s role as one of mediation and facilitation rather than control (Forester, 1987; Healey, 2003). Within this relational view, planning becomes a communicative process that builds shared understanding among actors with differing values, power, and expertise (Kaufman and Dilla Alfonso, 1997; Qi et al., 2024). Such perspectives position community space as a project, not a fixed physical outcome, but a dynamic process of negotiation and meaning-making among diverse stakeholders.

In African cities where planning institutions have limited reach, grassroots leadership often assumes this mediating role (Huybrechts et al., 2024; Majogoro et al., 2025b; Vedasto and Mrema, 2013). Building on the work of Majogoro et al. (2025a) and Majogoro et al. (2025b), this study adopts the concept of extended planners to describe grassroots leaders, who operate at the intersection of formal and informal governance systems. These actors (MC, MEO, MCM, & TCL) extend the work of professional planners by mediating land-use conflicts, coordinating collective action, and translating residents’ concerns into institutionally recognisable forms of governance (Majogoro et al., 2025b; Manara and Pani, 2023). Furthermore, the authors provide that their authority rests on social legitimacy and local knowledge rather than professional credentials, positioning them as everyday mediators who sustain the relational infrastructure of urban management.

The strengthening of these grassroots capacities is closely tied to UCC, which provides reflective arenas and technical scaffolding that enable local practises to be translated into shared frameworks of learning and governance (Canada et al., 2023; Dobson and Owolade, 2025). Through sustained, place-based engagement, universities provide analytical tools and methodological support that enable communities to articulate their priorities, document their experiences, and consolidate collective initiatives (Arnaldo Valdés and Gómez Comendador, 2022). Within this process, researchers function as facilitators and co-learners, not as extended planners themselves, but as collaborators who make extended-planning practises more visible, strategic, and resilient, thereby contributing to the emergence of collective leadership (Arnaldo Valdés and Gómez Comendador, 2022; Dobson and Owolade, 2025). This dynamism aligns with Parés et al. (2017), who conceive democratic leadership as a distributed and dialogic practise through which communities cultivate civic capacity to address shared challenges. Leadership, in this sense, is relational, emerging through trust, communication, and iterative experimentation, foundations that underpin social innovation and community resilience (Ospina and Foldy, 2010; Parés et al., 2017).

Nevertheless, the sustainability of such community-led innovations remains fragile, constrained by weak institutional recognition, volunteer fatigue, and limited documentation (Botero and Saad-Sulonen, 2018; Majogoro et al., 2025a). Following this argument, Parés et al. (2017) emphasise that durable civic capacity depends on embedded learning mechanisms that allow communities to reflect on practise, adapt to change, and preserve institutional memory.

Building on this conceptual foundation, the study examines the Sinza D green-space initiative as a community-driven process, focusing on its planning and preparatory phases. The initiative began when residents proposed transforming a neglected riverbank into a shared green space. The idea gained traction after grassroots leaders recognised its potential and assumed responsibility for steering the process. Through successive stages of dialogue, coordination, and documentation facilitated by university researchers, the proposal was refined, formally endorsed in a public meeting, and subsequently approved by the planning authority, setting the stage for implementation. The analysis, therefore, traces how collaboration unfolded during this formative period, how roles shifted, partnerships evolved, and collective learning processes emerged as the initiative moved from an informal idea to a publicly sanctioned community project.

In summary, this conceptual framing positions community space as a living project situated at the intersection of collaborative planning, extended planning, and UCC. Drawing on Healey (1997), Healey (2003) and Parés et al. (2017), it understands extended planners as grassroots mediators who enact civic leadership through negotiation, coordination, and translation between institutional and community priorities. Within this process, UCC operates as a reflective bridge, enabling joint learning, strengthening leadership capacity, and fostering community resilience. This framing provides the analytical foundation for examining the turning points through which collaboration evolved in the Sinza D initiative, revealing how shifting actor roles and patterns of engagement materialised through extended-planning practises and participatory mediation.

3 Methodology

This study employed a Participatory Action Research (PAR) approach to examine how UCC facilitated the transformation of a residual open space in Sinza D, Dar es Salaam, into a community-managed green hub. PAR emphasises iterative learning, co-production, and collective problem-solving (Cornwall and Jewkes, 1995; Kindon et al., 2009), allowing the researcher to act as a facilitator and reflective partner rather than a controller (Civic University Commission, 2019; Dobson and Owolade, 2025). This aligns with the study’s conceptual framing of researchers as collaborators who strengthen the capacity of extended planners and grassroots leaders mediating between community aspirations and institutional processes.

Sinza D, one of five sub-wards within Sinza Ward in Ubungo Municipality, lies approximately eight kilometres northwest of central Dar es Salaam (Besha et al., 2024; Lupala and Bhayo, 2014). According to the 2022 National Population and Housing Census, the area has approximately 6,640 inhabitants and 952 houses spread over 48 hectares (URT, 2022). Initially developed under the 1974 Sites and Services programme as a low- to middle-income residential area (Kironde, 1991; Remtulla, 2010), Sinza D has since evolved into a dense, mixed-use neighbourhood shaped by market pressures and unregulated redevelopment (Lupala and Bhayo, 2014; Vedasto and Mrema, 2013). The construction of Shekilango Road, Sam Nujoma Highway, and Mlimani City further intensified this transformation, stimulating land-use conversion towards multi-storey commercial and rental buildings (Besha et al., 2024; Lupala and Bhayo, 2014). Field observations confirm that Sinza D today is characterised by high land demand, strong economic dynamism, and acute scarcity of open space, conditions that make it emblematic of the urban transformation processes occurring across Dar es Salaam’s middle-income settlements.

The study focuses on a 0.35-hectare residual open space located along a rehabilitated riverbank bordering Manzese to the south (see Figure 1). Once neglected and flood-prone, the site gained renewed significance following flood-protection works completed in 2020, which stabilised the river channel and created potential for communal use. It now represents one of the few remaining open areas for recreation and collective gathering for residents of both Sinza D and the adjacent neighbourhood of Manzese. Whilst limited in scale, the case is analytically significant as it provides a microcosm through which to examine how university–community collaboration mediates the emergence of grassroots leadership and collective governance in rapidly urbanising contexts. A satellite image (Figure 1) illustrates the site and its surrounding built-up fabric.

The initiative unfolded over approximately 1 year (July 2024–May 2025) through a sequence of participatory learning and co-design activities that progressively structured community engagement around the transformation of the residual open space. It commenced with a leaders’ workshop, which initiated collective reflection on prevailing land-use challenges within the neighbourhood, followed by household interviews that traced the genesis of the green-space idea as a community-driven response to environmental degradation and spatial constraints. Subsequent block-level and public workshops enabled residents to articulate priorities, negotiate interests, and translate shared concerns into spatial proposals, culminating in a public endorsement meeting where the initiative gained collective legitimacy. The process concluded with a stakeholders’ meeting and a community reflection session, marking the consolidation of shared goals, governance arrangements, and mutual accountability. The study therefore focuses on this full cycle of planning, reflection, and coordination, analysing how collaboration evolved and community leadership strengthened over time, rather than on the later phase of physical implementation.

Stakeholder engagement formed the core of the research design, offering a lens to understand how collaboration evolved across stages of the Sinza D green-space initiative. Stakeholders were defined as individuals or groups who influenced or were affected by the process (Durham et al., 2014; Schnepf et al., 2024). A power–interest matrix (Dobson and Owolade, 2025; Durham et al., 2014) was used to map actors according to their authority and engagement, identifying extended planners—those with both high power and high interest—as pivotal collaborators. The IAP2 Spectrum of Public Participation (inform, consult, involve, collaborate, empower) (IAP2, 2025) complemented this by assessing the depth of participation and tracing how actor roles and relationships evolved over time.

Data were collected through participatory, observational, and dialogic methods to capture changing relationships and learning processes among actors. Fifteen households were interviewed (nine women and six men), followed by five reflection sessions that revealed shared concerns about the loss of greenery and local governance. Participatory mapping was conducted in three workshops: a grassroots leaders’ workshop (13 participants), a block workshop (7), and a public workshop (38), followed by a public meeting (76 participants) and a stakeholders’ meeting focused on governance arrangements. All sessions were documented through minutes, Swahili voice recordings, and field journals capturing both formal deliberations and informal negotiations.

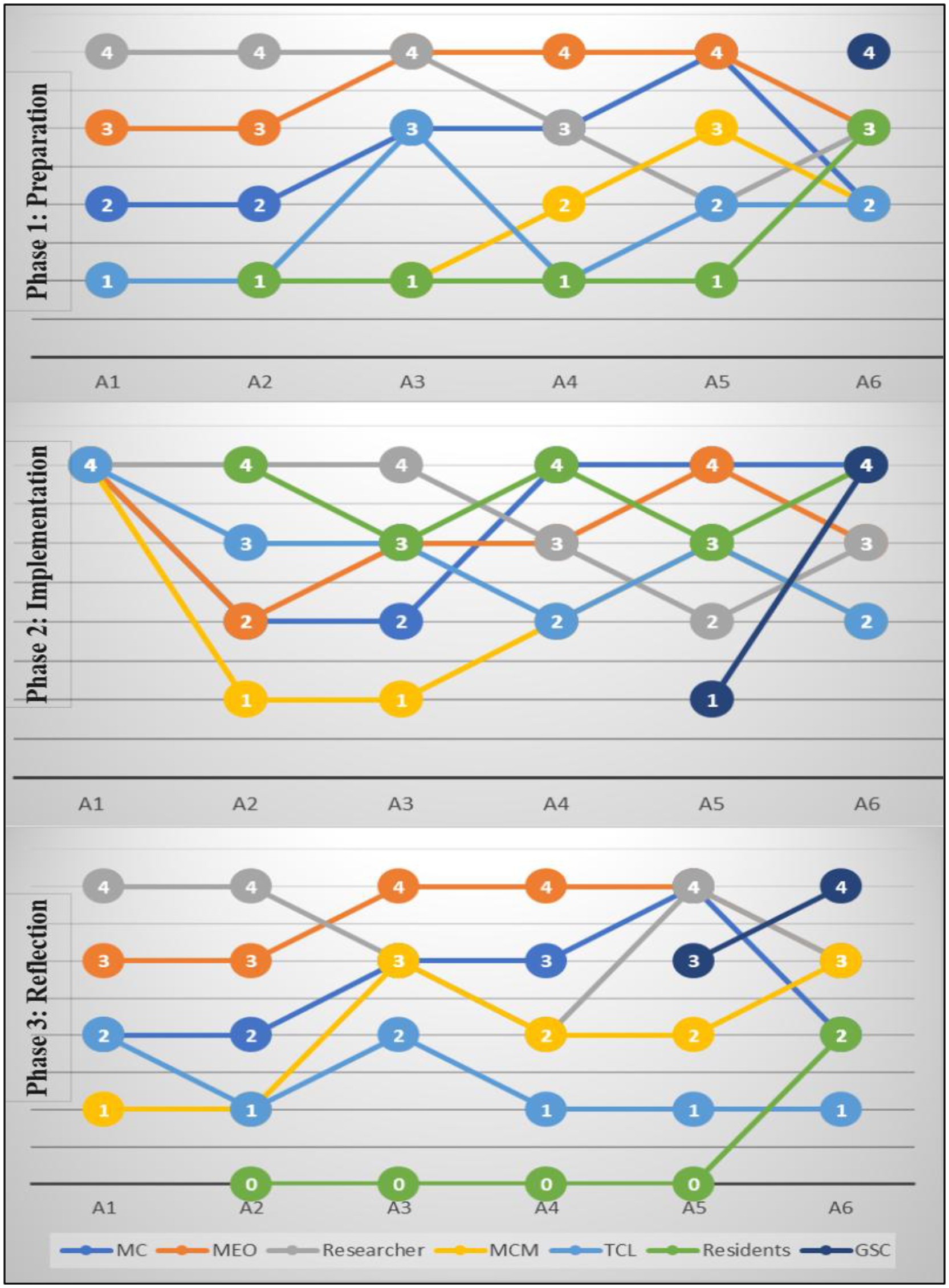

Data analysis relied primarily on thematic coding, complemented by structured observation using a five-point participation scale adapted from the IAP2 Spectrum: 0 = none, 1 = informed, 2 = consulted, 3 = involved, 4 = collaborated. Engagement levels, derived from field notes and reflections, were plotted across six key activities to visualise evolving participation (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Evolving roles of actors in the collaboration. Source: Fieldwork data analysis, Sinza D, 2024/2025.

Out of sixteen documented activities, six were selected for detailed analysis based on the richness of interaction and reflection. Thematic comparison revealed two analytical dimensions: first, the turning points, moments when participation or relationships changed qualitatively, and second, the patterns of engagement, recurring configurations of actor roles (university-led, extended planners-led, community-led). Together, these insights trace how facilitation evolved into collective leadership and community ownership.

Ethical approval was granted by local authorities, and verbal consent was obtained from all participants. Reflexivity was integral throughout, ensuring that facilitation strengthened rather than substituted community agency, whilst participatory validation enhanced accountability and shared ownership of outcomes.

4 Findings

4.1 Facilitation and the emergence of community leadership

The evolution of the Sinza D green space initiative reveals how community leadership emerged through iterative cycles of inquiry, reflection, and negotiation. Rather than following a pre-planned sequence, collaboration unfolded through a series of empirical turning points, each reshaping how authority, knowledge, and responsibility were shared between researchers, grassroots leaders, and residents. These turning points are analytically significant because they demonstrate how facilitation gradually evolved into locally grounded leadership, illustrating the collaborative mediation between institutional and community spheres.

4.1.1 Turning point 1: from institutional coordination to collective inquiry

The first turning point began with the Mtaa Government Leaders (MGL) Workshop, where the researchers initiated collaboration with grassroots leaders, referred to here as extended planners, including the MC, MEO, MCM, and TCL. This session established a shared agenda and legitimised the need to address persistent land-use conflicts in Sinza D. Through facilitated dialogue, participants prioritised three key issues: waste accumulation, informal land conversion, and loss of greenery, and agreed to engage directly with residents to understand these challenges from a lived experience perspective.

The subsequent household interviews and reflection sessions deepened participation and shifted the process from coordination to inquiry. Fifteen households provided narratives about the loss of greenery, environmental degradation, and safety concerns. During the five follow-up reflections, one household proposed reusing the neglected riverbank area as a communal green space. As other participants revisited their own accounts, they recognised similar frustrations and needs, gradually seconding the proposal and expanding it into a shared vision. What began as an individual suggestion thus evolved, through dialogue and mutual recognition, into a collectively owned idea.

This iterative reflection process transformed individual narratives into communal insight, linking household concerns to the initiative’s broader objectives of environmental restoration and community ownership. The researchers facilitated these exchanges, ensuring an open and dialogical environment, yet the momentum and substance of the discussion increasingly came from the residents themselves. At this stage, knowledge and initiative began to move from the institutional to the communal domain, marking a decisive shift towards collective inquiry.

4.1.2 Turning point 2: from reflection to collaborative planning

The second turning point emerged as reflection was translated into practical collaboration. During the Block Workshop, residents and TCL revisited the earlier household findings and considered how to organise collective action around the residual space. Some residents expressed scepticism, recalling unsuccessful clean-up attempts in the past. Others pointed to gaps in documentation and follow-up. As the MEO remarked:

“To identify documents from two years back in this office, it’s not easy. Maybe, visit the municipal council…” (MEO, Activity 3, 2025).

This statement revealed deeper issues of continuity and institutional memory. In response, the researchers encouraged the use of written records, sketches, and photographs to support accountability and visibility. These practises strengthened trust and gave participants a tangible sense of progress.

The Public Workshop that followed, attended by 38 residents and municipal officers, reflected the consolidation of this trust. Residents used the maps produced from the reflections to communicate their shared vision. Municipal officers recognised the proposal and provided feedback on procedural steps for formal approval. Facilitation thus evolved into collaborative planning, where residents and extended planners worked alongside researchers and government officers to formalise a community-driven initiative.

4.1.3 Turning point 3: from collaborative planning to community leadership

The third turning point occurred during the Public Meeting, when residents agreed to form the Green Space Committee (GSC). This decision represented a concrete shift from collaboration to self-organisation. The committee comprised elders, women, and youth, striking a balance between representation and responsibility. The extended planners supported the formation process, whilst the researchers provided mentorship and guided the establishment of reporting procedures to ensure transparency and accountability.

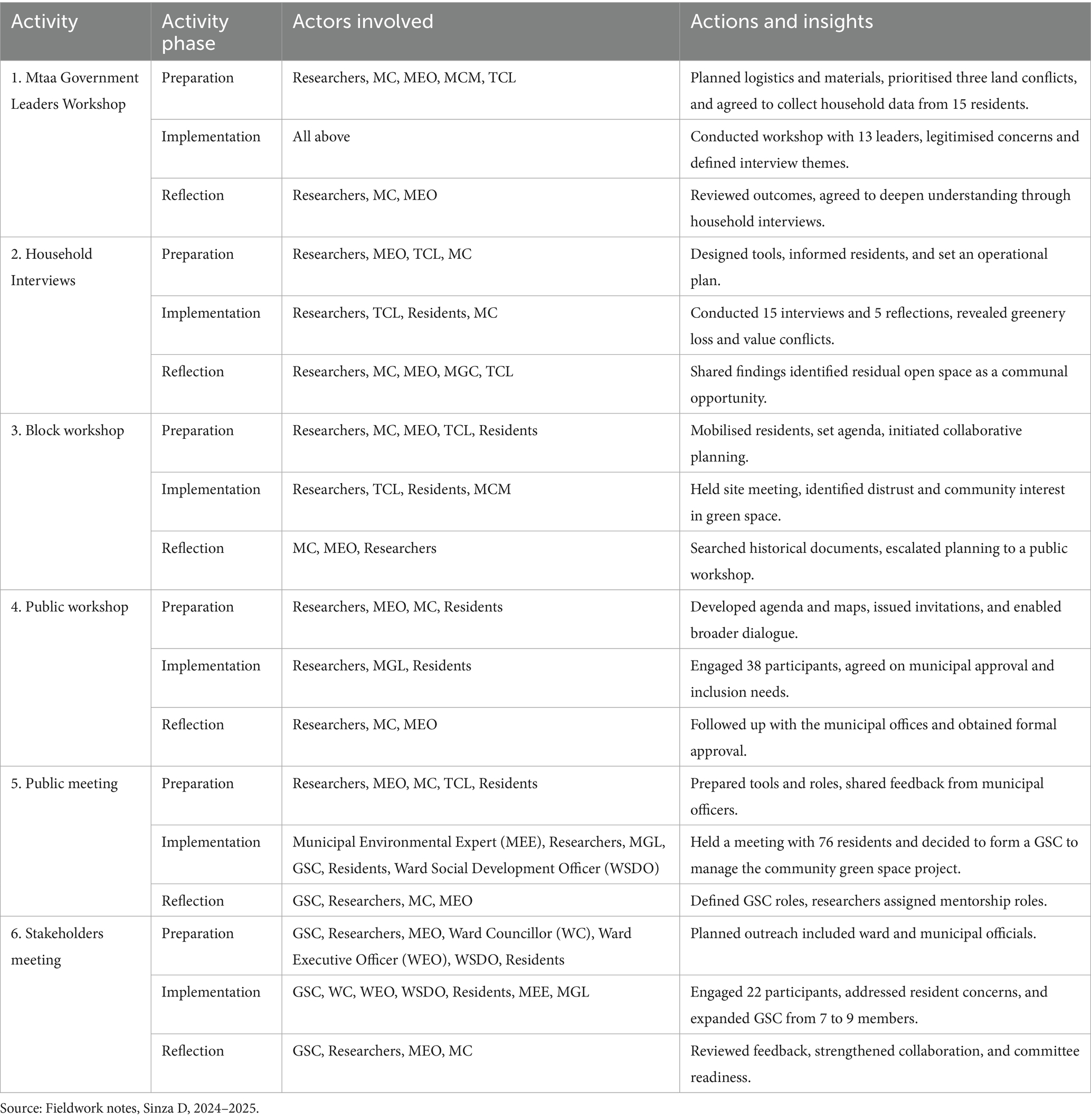

In the final stakeholders meeting, ward and municipal officials recognised the GSC and endorsed its role in managing the green space. The committee expanded from seven to nine members and was formally linked with ward-level environmental programmes. By this stage, coordination and leadership had become embedded within the community’s own structure, with residents assuming full responsibility for decision-making. The GSC’s emergence signalled the consolidation of community leadership, an outcome of sustained facilitation and shared learning between the researchers and extended planners. Table 1 summarises how actors were involved in the collaborative research, the activities that each actor played, how each was involved, and the insights that each group of actors had in Sinza D area.

The three turning points and the summary in Table 1 collectively illustrate how facilitation in the Sinza D initiative evolved through a recursive process of planning, action, and reflection. Each activity combined procedural coordination with opportunities for learning, enabling a gradual redistribution of initiative and authority among actors. What began as researcher-led coordination with grassroots leaders expanded into collaborative planning that incorporated residents’ lived experiences, and ultimately into a self-organised structure through the GSC. The table traces this trajectory across the preparation, implementation, and reflection phases, revealing that community leadership did not emerge from a single event but through cumulative adjustments, negotiated trust, and expanding legitimacy. These shifts demonstrate how iterative collaboration can transform facilitation into shared governance, setting the foundation for the actor-based analysis that follows.

4.2 Actors and their evolving roles in the collaboration

Collaboration in the Sinza D initiative evolved through negotiated adaptation, as roles were continuously reshaped through interaction, reflection, and shared decision-making. Analysis of the six project activities reveals a gradual redistribution of authority and legitimacy among researchers, grassroots leaders, and residents. This progression unfolded across three overlapping modes of collaboration: university-led, extended planners-led, and residents-led, which together reflect the deepening of participation and trust as facilitation matured into community leadership. Figure 2 visualises this trajectory, illustrating how actors’ influence and responsibilities shifted over time through the preparation, implementation, and reflection phases. The transitions captured in the figure align with the empirical turning points discussed earlier, showing how facilitation gradually gave way to distributed and then community-led forms of governance.

4.2.1 Pattern 1: the researcher as trigger and transition point to community ownership

As illustrated in Figure 2, the early phase of collaboration was university-led, with the researcher serving as the primary facilitator and convener. This facilitative and co-creative role was most evident during Activities 1–3, when coordination, planning, and documentation were closely guided by the research team in partnership with the MC and MEO. The researcher organised meetings, prepared materials, and ensured that dialogue remained focused on the agreed objectives. This facilitative position aligns with participatory research approaches in which academic actors initiate structured reflection to build shared understanding whilst deliberately avoiding control of the process.

During the planning and engagement stages, the researcher maintained significant influence, helping to frame agendas and mediate communication between institutional and community actors. However, reflection moments within these early activities began to alter this dynamic. After the household interviews, grassroots leaders began to independently interpret the findings and propose next steps. The MC and MEO gradually took ownership of coordination tasks, signalling a transfer of decision-making authority from the university to the grassroots level.

By the time of the public meeting and subsequent stakeholder engagement, the researcher’s role had shifted into mentorship. The MC articulated this boundary clearly:

“The meeting is ours. Your role as a researcher is to listen; if there is anything to ask, you will be given the opportunity.” (MC, Activity 5, 2025).

This moment represented the practical transition from university-led coordination to extended planners-led facilitation, enabled by the growing confidence of grassroots leaders and the cumulative effects of structured reflection and collaborative learning.

4.2.2 Pattern 2: distributed and complementary leadership among grassroots actors

As shown in Figure 2, the extended planners-led phase (Activities 3–5) marked a redistribution of authority from researchers to community-level actors within the Mtaa Government Office (MGO). As facilitation receded, leadership became shared among the MC, MEO, MGC, and TCLs, reflecting an emerging balance between political legitimacy and administrative coordination.

The MC took the lead in public engagement, mobilising residents and giving the process visibility, whilst the MEO ensured procedural alignment and institutional continuity. Their interdependence was evident in their reflections:

“…we as leaders, it’s either get credits or lose…, therefore, we must work together…” (MC, Activity 4, 2025) and in the MEO’s acknowledgement that, “The public is for the MC… He must have more power compared to me” (MEO, Activity 4, 2025).

These exchanges reveal an evolving recognition that collective action, rather than individual authority, was key to legitimacy.

Meanwhile, MGC and TCL became increasingly active, translating facilitation into neighbourhood-level coordination. As one MGC noted:

“This project has made us work more… at least now we feel like leaders” (MGC, Activity 4, 2025).

Though less involved in reflective discussions, TCLs anchored the process logistically, mobilising households and sustaining communication between activities. This phase illustrates how distributed leadership and mutual trust revitalised grassroots governance. The MGL’s growing collaboration bridged institutional and community spheres, paving the way for the eventual handover of responsibility to the GSC.

4.2.3 Pattern 3: expanding resident agency and the shift to shared ownership

Residents’ As shown in Figure 2, the residents-led phase emerged gradually through Activities 2–6, as participation evolved from consultation to co-creation. In the early stages, residents were informed through invitations or verbal mobilisation, with little control over agendas. This dynamic began to shift in Activity 5, when early discussions about forming a committee encouraged relational engagement rather than token involvement. As the MEO noted:

“If we shall not involve them, then they may not come… let’s talk to them first to know their position.” (MEO, Activity 6, 2025).

Residents soon moved from providing input to shaping collective decisions. Through household interviews and the public workshop (Activities 2 and 4), they co-defined priorities for site use and maintenance, grounding technical planning in lived experience. By Activity 6, residents participated across all phases — preparation, implementation, and reflection — signalling a full cycle of inclusion.

A newly selected GSC member captured the affective dimension of this transition:

“At least now you recognise our presence. This way of working makes us feel part of the project…” (Resident, Activity 6, 2025).

This progression from consultation to collaboration, and ultimately co-ownership, reflects how recognition and iterative reflection cultivated resident agency. Engagement became not an external requirement but a shared civic practise, anchoring legitimacy in collective learning and mutual trust.

4.2.4 Pattern 4: delegated leadership and the institutional rise of the green space committee

As shown in Figure 2, the community-led phase (Activities 5–6) marked the culmination of the collaborative process, as facilitation gave way to institutionalised grassroots leadership. The formation of the GSC represented a collective decision to formalise community ownership and ensure project continuity beyond the research period.

Elected by residents, the GSC assumed responsibilities previously managed by the MC, MEO, and researcher: coordination, communication, and stakeholder engagement, transforming facilitation into self-governance. The MGL adopted a mentorship role, maintaining procedural oversight whilst endorsing the committee’s autonomy. As the MC advised during reflection:

“…you should continue working with the committee to help them understand the main goal of the project and the way of working with the community…” (MC, Activity 6, 2025).

This mentorship reinforced both the committee’s legitimacy and its institutional ties. Recognition from ward and municipal officers further elevated its standing. The Ward Councillor observed:

“You have made a good decision to have an independent committee for this project… You are now working on behalf of the whole community.” (WC, Activity 6, 2025).

Internal dialogues revealed the committee’s emerging sense of accountability and shared responsibility:

“What if this project fails? Will we be condemned?” (GSC member, Activity 5, 2025).

“…we shall be together, but you have the responsibility to make sure we succeed.” (Resident, Activity 5, 2025).

The MEO concluded by institutionalising quarterly reporting within Mtaa government meetings, embedding the GSC within existing governance structures.

“We must report on this project every quarter in our scheduled meetings.” (MEO, Activity 5, 2025).

Through these exchanges, delegated leadership evolved into structured community governance. The GSC became a legitimate and accountable body, endorsed by residents, supported by grassroots leaders, and recognised by formal authorities, anchoring the initiative within a durable, community-led framework of stewardship and learning.

4.3 Discussion: turning points, actor dynamics, and the evolution of collaborative leadership

The Sinza D initiative highlights how facilitation, when integrated into cycles of reflection and negotiation, can foster community leadership and hybrid governance capacities. The discussion that follows integrates the three empirical turning points and four actor patterns identified earlier, situating them within broader debates on civic universities, participatory mediation, and grassroots institutionalisation (Benneworth and Jongbloed, 2013; Dobson and Owolade, 2025; Forester, 2006; Healey, 1997; Cornwall and Jewkes, 1995). The analysis reveals that leadership in UCC neither transfers nor is imposed, but rather emerges relationally through iterative realignments of power, legitimacy, and responsibility.

4.3.1 Turning point 1 and pattern 1: from institutional coordination to collective inquiry

The first turning point, linking the early facilitation by researchers with the initial participation of grassroots leaders, marks the formation of what Benneworth and Jongbloed (2013) refers to as a civic intermediary space. Here, the university’s role was not to prescribe solutions but to enable local leaders to articulate community-defined problems. The researcher, acting as both convener and facilitator, initiated reflection whilst deliberately avoiding control over the outcomes. This corresponds with Cornwall and Jewkes (1995), who argue that participatory inquiry becomes transformative when facilitation foregrounds local knowledge rather than expert instruction.

Within this configuration, the researcher and MGL co-produced a platform of legitimacy: the workshops and household reflections collectively transformed fragmented concerns into a shared narrative about green space, safety, and communal well-being. As Dobson and Owolade (2025) emphasise, civic impact depends less on outreach than on sustaining relational spaces of engagement. The Sinza D case exemplifies this principle; the facilitative encounters built mutual recognition and repositioned residents as legitimate contributors to planning discourse.

4.3.2 Turning point 2 and patterns 2–3: reflection, mediation, and distributed leadership

The second turning point, from reflection to collaborative planning, activated a redistribution of leadership among actors. The researcher’s influence receded as the MC and MEO assumed coordination roles, whilst residents shifted from consultative participants to co-creators. This reflects Healey’s (1997) conception of collaborative planning as a communicative process in which facilitation evolves into negotiated mediation among situated actors.

Forester (2006) reminds us that mediation succeeds by not neutralising difference but by making it productive. In Sinza D, disagreement about failed past initiatives became a productive tension that motivated institutional learning. The MEO’s admission of documentation weaknesses revealed structural fragility, but the introduction of mapping and record-keeping transformed that weakness into an opportunity for procedural innovation. Following Botero and Saad-Sulonen (2018) and Majogoro et al. (2025a), documentation here functioned as a boundary object, a shared artefact that stabilised collaboration, sustained trust, and preserved continuity between meetings.

This stage also revealed the emergence of distributed and complementary leadership among grassroots actors. The MC’s public advocacy lent symbolic legitimacy, whilst the MEO’s procedural rigour ensured institutional durability. Their interplay corresponds with Ospina and Foldy’s (2010) notion of democratic leadership, wherein authority is relationally negotiated rather than hierarchically assigned. Together, these patterns demonstrate how reflective mediation and tangible documentation anchored a hybrid form of leadership grounded in both social trust and administrative accountability.

4.3.3 Turning point 3 and pattern 4: institutionalising community leadership

The final turning point, which is the formation of the GSC, signalled the consolidation of distributed leadership into a formal governance entity. The committee’s creation reconfigured existing actor relationships, embodying what Manara and Pani (2023) describe as institutional hybridity: the blending of formal administrative authority with informal community-based governance. The GSC’s recognition by both residents and municipal officials reflects a co-production of legitimacy “from above to below.”

At this stage, the MGO’s role transformed from directive to supportive. The MC and MEO became mentors and connectors, mediating between the GSC and higher administrative bodies. Their position aligns with the notion of extended planners, as locally embedded figures who operate at the interface of bureaucratic procedures and community realities. This echoes Dobson and Owolade’s (2025) argument that universities’ civic relevance endures when local actors internalise collaborative practises and sustain them autonomously.

4.3.4 Cross-cutting insights: collaboration as situated governance learning

Across all three turning points and four actor patterns, the Sinza D case reveals a continuous learning trajectory rather than a linear transfer of skills. Reflection sessions served as recursive feedback loops, where authority was renegotiated; documentation provided an institutional memory that bridged cycles of participation; and trust acted as the medium through which facilitation matured into self-governance.

These empirical dynamics substantiate Healey’s (2003) view of collaborative planning as a situated practise of governance learning. They demonstrate that community leadership evolves not solely from capacity building, but from the alignment of knowledge, recognition, and procedural visibility. The trajectory from researcher-led facilitation to GSC-led governance illustrates how civic collaboration can generate enduring institutional arrangements that connect everyday practises to formal planning structures.

5 Conclusion

The Sinza D green-space initiative demonstrates how structured yet flexible collaboration within university–community engagement can promote resilient and inclusive local governance. Through six interconnected activities, facilitation shifted into community leadership as researchers, grassroots leaders, and residents negotiated roles, responsibilities, and legitimacy. The process transformed a neglected urban space into a platform for collective action and mutual learning. An important insight is the researcher’s adaptive role, initially coordinating and documenting, then intentionally stepping back to allow grassroots actors to take the lead. Acting as a temporary extended planner, the researcher mediated between institutional and community spheres without dominating either side. This repositioning created conditions for local leaders and residents to build procedural legitimacy, confidence, and ownership of the initiative. The formation of the GSC exemplified this transition, evolving from facilitated participation into an autonomous governance structure that strengthened trust between residents and the grassroots government. Through participation, documentation, and dialogue, residents who were once marginalised became active co-creators of their environment. As one participant stated, “We need as a community to solve our own problems.” Beyond reaffirming the value of participatory action research, the findings show a promising pathway for institutionalising co-production within everyday governance structures. The concept of extended planners highlights how Mtaa leaders and community actors can serve as adaptive mediators, blending formal mandates with relational, context-sensitive practises connecting the state and the community. This hybrid governance approach enhances existing scholarship on civic universities and community-based planning by demonstrating that facilitation can develop into enduring, community-owned institutions. Whilst these insights are notable, the study remains context-specific. Conducted as part of an ongoing PhD project with roughly a year of sustained engagement in Sinza D, it reflects the dynamics of a single urban neighbourhood. The process encountered common challenges of participatory governance, including fluctuating attendance, uneven commitment, and procedural delays within municipal systems. However, these challenges also became moments for learning, revealing the adaptive capacities of grassroots institutions under constrained conditions. Future research should extend this inquiry across diverse neighbourhoods and governance regimes in Tanzania and beyond, exploring how university–community collaboration can sustain engagement, funding, and intergenerational participation after external facilitation ends. Longitudinal approaches could further clarify how committees like the GSC maintain their legitimacy and relationships with formal institutions over time. Ultimately, this study demonstrates that reflexive and co-produced collaboration can transform power relations in urban governance, reshaping facilitation into shared stewardship. For universities, municipalities, and development agencies, the challenge is not only to work with grassroots leaders but also to learn from their local practises. Recognising and supporting these hybrid, adaptive methods is essential for creating inclusive, resilient, and more-than-human urban futures.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ardhi University, department of urban and regional planning. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

MM: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Writing – original draft. OD: Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition. FM: Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded under the joint partnership between Hasselt University (Belgium) and Ardhi University (Tanzania) as part of the Institutional University Cooperation (IUC) programme, supported by VLIR-UOS, grant ID: TZ2022IUC042A104.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledges the support of the Institutional University Cooperation (IUC) programme funded by VLIR-UOS, through the partnership between Hasselt University (Belgium) and Ardhi University (Tanzania). Special thanks are extended to the grassroots leaders, members of the GSC, MGL, and residents of Sinza D for their trust, collaboration, and active participation throughout the research process. Their insights, actions, and reflections were central to the learning journey documented in this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT in order to develop ideas and improve the language. After using the tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and took full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aleha, A., Zahra, S. M., Qureshi, S., Marri, S. A., Siddique, S., and Hussain, S. S. (2023). Urban void as an urban catalyst bridging the gap between the community. Front. Built Environ. 9:1068897. doi: 10.3389/fbuil.2023.1068897

Alexander, A. C., Izdori, F. J., Mulungu, D. M. M., and Mugisha, L. R. (2024). Analysis of Msimbazi River banks erosion with regards to soil erodibility. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-4551858/v

Apostolopoulou, E., Bormpoudakis, D., Chatzipavlidis, A., Cortés Vázquez, J. J., Florea, I., Gearey, M., et al. (2022). Radical social innovations and the spatialities of grassroots activism: navigating pathways for tackling inequality and reinventing the commons. J. Polit. Ecol. 29:2292. doi: 10.2458/jpe.2292

Arnaldo Valdés, R. M., and Gómez Comendador, V. F. (2022). European universities initiative: how universities may contribute to a more sustainable society. Sustainability 14:471. doi: 10.3390/su14010471

Benneworth, P., and Jongbloed, B. (2013). “Policies for promoting university–community engagement in practice” in University engagement with socially excluded communities. ed. P. Benneworth (Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer), 243–261. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-4875-0_13

Besha, R., Huybrechts, L., and Kombe, W. (2024). Co-designing with scarcity in self-organised urban environments: a case of Shekilango commercial street in Sinza, Dar Es Salaam – Tanzania. CoDesign 20, 781–797. doi: 10.1080/15710882.2024.2377976

Botero, A., and Saad-Sulonen, J. (2018). “Challenges and opportunities of documentation practices of self-organised urban initiatives” in Participatory design thoery: Using Technology and Social Media to Foster Civic Engagement. 1st ed, Routledge: Taylor & Francis Group. 5:230–246.

Busindeli, I. M., Martin, R., and Kalungwizi, V. J. (2024). Enhancing sustainability of university-based outreach activities through participatory action research: the case of Sokoine University of Agriculture. Int. J. Agric. Ext. 12, 307–318. doi: 10.33687/ijae.012.002.5153

Canada, G., Yamamura, E. K., and Koth, K. (2023). Place-based community engagement in higher education: A strategy to transform universities and communities. 1st Edn. New York. Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781003446323

Chitongo, L., and Zhanda, K. (2025). Transforming universities through strategic plans in South Africa and Zimbabwe: continuities and discontinuities. J. Educ. Learn. Technol. 6, 607–621. doi: 10.38159/jelt.2025687

Civic University Commission (2019). Truly civic: Strengthening the connection between universities and their places. The final report of the UPP foundation. London: UPP Foundation. Avilable online at: https://upp-foundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Civic-University-Commission-Final-Report.pdf

Coetzee, H., and Nell, W. (2018). Measuring impact and contributions of south African universities in communities: the case of the North-West University. Dev. South. Afr. 35, 774–790. doi: 10.1080/0376835X.2018.1475218

Cornwall, A., and Jewkes, R. (1995). What is participatory research? Soc. Sci. Med. 41, 1667–1676. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00127-S

Dobson, J., and Owolade, F. (2025). Resourcing universities to increase their civic impact: meeting challenges of communication, complexity and commitment. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 47, 524–542. doi: 10.1080/1360080X.2025.2461811

Dovey, K. (2012). Informal urbanism and complex adaptive assemblage. Int. Dev. Plan. Rev. 34, 349–368. doi: 10.3828/idpr.2012.23

Durham, E., Baker, H., Smith, M., Moore, E., and Morgan, V. (2014). BiodivERsA stakeholder engagement handbook: best practice guidelines for stakeholder engagement in research projects. Paris: BiodivERsA. Avilable online at: https://www.biodiversa.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/stakeholder-engagement-handbook.pdf

Forester, J. (1987). Planning in the face of conflict: negotiation and mediation strategies in local land use regulation. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 53, 303–314. doi: 10.1080/01944368708976450

Forester, J. (2006). Making participation work when interests conflict: moving from facilitating dialogue and moderating debate to mediating negotiations. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 72, 447–456. doi: 10.1080/01944360608976765

Fussy, D. S. (2018). Policy directions for promoting university research in Tanzania. Stud. High. Educ. 43, 1573–1585. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2016.1266611

Goddard, J., and Vallance, P. (2011). The civic university and the leadership of place. Centre for Urban and Regional Development Studies (CURDS). United Kingdom: Newcastle University.

Healey, P. (2003). Collaborative planning in perspective. Plan. Theory 2, 101–123. doi: 10.1177/14730952030022002

Huybrechts, L., den Van Eynde, D., Kabendela, G., Knapen, E., Kimaro, J., and Magina, F. (2024). Institutioning as action: Mediating grassroots labor and government work for sustainable transitions. International Journal of Design. 18. doi: 10.57698/V18I3.07

IAP2 (2025). Organizing engagement: Spectrum of public participation. Available online at: https://organizingengagement.org/models/spectrum-of-public-participation/ (Accessed August 5, 2025).

Kaufman, M., and Dilla Alfonso, H. (1997). Community power and grassroots democracy: The transformation of social life. Zed Books. London and Ottawa: International Development Research Centre.

Kindon, S., Pain, R., and Kesby, M. (2009). “Participatory action research” in International encyclopedia of human geography. (Oxford: Elsevier), 90–95. doi: 10.1016/B978-008044910-4.00490-9

Kironde, L. (1991). Sites-and-services in Tanzania. Habitat Int. 15, 27–38. doi: 10.1016/0197-3975(91)90004-5

Lupala, J., and Bhayo, S. A. (2014). Building densification as a strategy for urban spatial sustainability analysis of inner city neighbourhoods of Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania. Glob. J. Inc. (USA) 14, 29–44.

Majogoro, M., Devisch, O., and Magina, F. B. (2025a). Adapting to urban planning contradictions in community-led initiatives in growing African cities: a case study of Sinza D, Dar Es Salaam. Urban Governance 5:S2664328625000890. doi: 10.1016/j.ugj.2025.10.002

Majogoro, M., Devisch, O., and Magina, F. B. (2025b). Participatory retrofitting through extended planners in Tanzanian urban areas. Urban Plan. 10, 51–73. doi: 10.17645/up.9015

Manara, M., and Pani, E. (2023). Institutional hybrids through meso-level bricolage: the governance of formal property in urban Tanzania. Geoforum 140:103722. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2023.103722

Mrema, K. J. (2024). Assessing the perceived university-community consulting services for sustainable development: insights from the Open University of Tanzania. Asian Res. J. Arts Soc. Sci. 22, 33–47. doi: 10.9734/arjass/2024/v22i12595

Ndimbo, G. K., and Nkwabi, S. M. (2025). University-society relationships: institutional barriers to the effective implementation of the university’s third mission in Tanzania. SAGE Open 15:21582440251358974. doi: 10.1177/21582440251358974

Ngowi, N., Kadio, J., and Chiduo, P. (2022). Do village and Mtaa executive officers have legal knowledge of their duties and responsibilities as community workers? A case of selected district councils. Plan. Dev. Initiative J. 5, 56–71.

Ospina, S., and Foldy, E. (2010). Building bridges from the margins: the work of leadership in social change organizations. Leadersh. Q. 21, 292–307. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.01.008

Parés, M., Ospina, S., and Subirats, J. (2017). Social innovation and democratic leadership: Communities and social change from below. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Qi, J., Mazumdar, S., and Vasconcelos, A. C. (2024). Understanding the relationship between urban public space and social cohesion: a systematic review. Int. J. Community Well-Being 7, 155–212. doi: 10.1007/s42413-024-00204-5

Reed, M. S., Vella, S., Challies, E., De Vente, J., Frewer, L., Hohenwallner-Ries, D., et al. (2018). A theory of participation: what makes stakeholder and public engagement in environmental management work? Restor. Ecol. 26:2541. doi: 10.1111/rec.12541

Remtulla, Z. H. (2010). The National Sites and services project in Tanzania: a case study. [Doctoral dissertation]. Vancouver: University of British Columbia.

Schnepf, M., Prestes Dürrnagel, S., Laghetto, G., Pastor, T., and Ritchie, C. (2024). Stakeholder analysis. Report on stakeholder analysis including evaluation of engagement, training needs and capacity building. Res. Ideas Outcomes., 5:e132163. doi: 10.3897/arphapreprints.e132163

Smith, A., Fressoli, M., and Thomas, H. (2014). Grassroots innovation movements: challenges and contributions. J. Clean. Prod. 63, 114–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.12.025

URT (2018). The urban planning (planning space standards) regulations. Ministry of Lands, Housing and Human Settlements Development, United Republic of Tanzania.

URT (2019). Handbook for standards and guidelines for university education in Tanzania. Tanzania: Tanzania Commission for Universities.

URT. (2022). Ministry of Finance and planning, Tanzania National Bureau of statistics and president’s office—Finance and planning, Office of the Chief Government Statistician, Zanzibar. United Republic of Tanzania: The 2022 population and housing census: Age and sex distribution report.

URT (2023). Guidelines for research excellence award to researchers publishing in high impact factor journals. Ministry of Education, Science and Technology. Available online at: https://www.moe.go.tz/sites/default/files/mwoengozo%20wa%20tuzo%20tafiti_0.pdf (Accessed January 20, 2025).

Vedasto, R. V., and Mrema, L. K. (2013). Architectural perspectives on informalization of formal settlements: case of Sinza neighbourhood in Dar es Salaam. Online J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2, 151–172.

VLIR-OUS. (2025). Available online at: https://www.vliruos.be/about-vliruos (Accessed July 11, 2025).

Keywords: urban governance, green space transformation, university–community collaboration, extended planners, civic university

Citation: Majogoro M, Devisch O and Magina FB (2025) Transformation of residual open spaces into a green community hub: a case study from Sinza D, Dar es Salaam. Front. Sustain. Cities. 7:1700035. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2025.1700035

Edited by:

Francesca Poggi, NOVA University of Lisbon, PortugalReviewed by:

Jorgelina Hardoy, IIED-América Latina, ArgentinaAlessandra Manganelli, University of Barcelona, Spain

Copyright © 2025 Majogoro, Devisch and Magina. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Manyama Majogoro, bWFueWFtYS5tYWpvZ29yb0B1aGFzc2VsdC5iZQ==

Manyama Majogoro

Manyama Majogoro Oswald Devisch

Oswald Devisch Fredrick Bwire Magina

Fredrick Bwire Magina