Introduction

Discussions about urban greenery have gone from ecological framings to cases of environmental justice and equitable access (Farkas et al., 2023). Losses due to limited preserving for densely populated urban areas is an urgent case for urban green spaces (UGS; Vogt, 2025a), with proven implication for the natural-environment and human health (WHO Team, 2023). In 2015, Haaland and van den Bosch (2015) found that provisioning and preventing biodiversity loss is two of more than seven challenges identified for dense cities. Improving measures of losses, reserving, and improving the quality, as aesthetic, visibility, and functional biodiversity, of existing urban greenery, and greening in difficult sites such as narrow streets are recommended to address rapid loss and fragmentation. Green in dense cities is needed but requires localized diversity in spatial layout and design to ensure positive interactions with different Urban Open Spaces (UOS), including gray (formal and informal paved or built urban landscapes) and transparent space (air and aquatic; Vogt, 2025b). For dense cities, small UGS of diverse sizes and shapes, corridors, vertical walls, rooftops, other elevated spaces, and pocket parks prove to provision benefits needed, and in some cases provision therapeutic effects (Vogt, 2025a). While efficiencies of cooling effect vary, with plant density and spatial distributions, parks, green roofs, and street trees can lower air and surface temperatures by up to 5*C (Lin and Li, 2025). This opinion article explains how (i) dense cities can be green, using functionally connective small, elevated, vertical and corridor green spaces, and measuring larger sized UGS; (ii) two categories of benefits from access to urban greenery can guide understanding of a need for urban greenery. It goes on to answer, how green? The conceptual guidance and measures of need for benefits leads to an optimized quality of life from urban biodiversity as an effective green dense city. Planning, implementation, monitoring, and identifying UGS locations is responsive to local landscape measures and guided by refined wilding for dense cities.

Can a city be dense and green?

Urban planning and how it is informed and implemented is significantly determinant to answering if a dense city can be green. Space allocation, availability and strategic locations, elevated, vertical and small spaces provide better opportunities for green in dense cities. Aesthetic preferences influenced by urban cultural norms in cityscape design can be a limitation or motivator for whether a city is dense and green. This limitation could be for lack of vision, clarity, or example of how dense cities can be green. Resources required, or an understanding of resources needed could as well. Perspective changes and design options for cityscapes, buildings, UOS and surroundings including hidden green spaces might address the limitation and encourage urban green integration. Compact cities require localization and acceptance of diversity in urban plans (Bonfantini et al., 2025). While often referred to as lower emitters with density-emissions relationship (Castells-Quintana et al., 2021) determined by size and structure of urban areas, air pollution (Manisalidis et al., 2020) and other effects often experienced in urban landscapes variably require mitigation. As UGS can provide multiple functions, the following question is how green and how functionally or effectively green?

Buildings and greenery are more often integrated in dense cities (Song et al., 2025) not just adjoined or separate. For a dense city to be green, design and planning that integrates built urban landscapes, gray spaces with green spaces is required, alongside defining green for dense cities, as surrounding greenery measured for benefit from access. Localized measures can lead to need for, alongside a a question of can.

An ability to see how green?

For dense cities, local studies of need for specific mitigative effect and or therapeutic benefits, and the feasibility of provisioning access can determine how green.

I suggest conceptual guidance for imagining how green a dense city can be, and how effectively green as a significant for urban planning and design.

An ability to see how it can be green: Conceptual guidance

Guidance from concepts and principles can be significant for urban form, spatial planning and configuration and vision for an urban landscape. A concept can provide a vision or imagining for how green, or even an optimized green, instead of whether it can be green, with conceptual bounds for indicators of benefit for an urban landscape. It can also generate enthusiasm for what the concept aims for, with an ability to see how an urban landscape can be green. A concept might inspire design and planning at a landscape level, with elaboration on how green is defined and conceptualized. A good concept can sufficiently elaborate for imagining and can improve the effectiveness of how green.

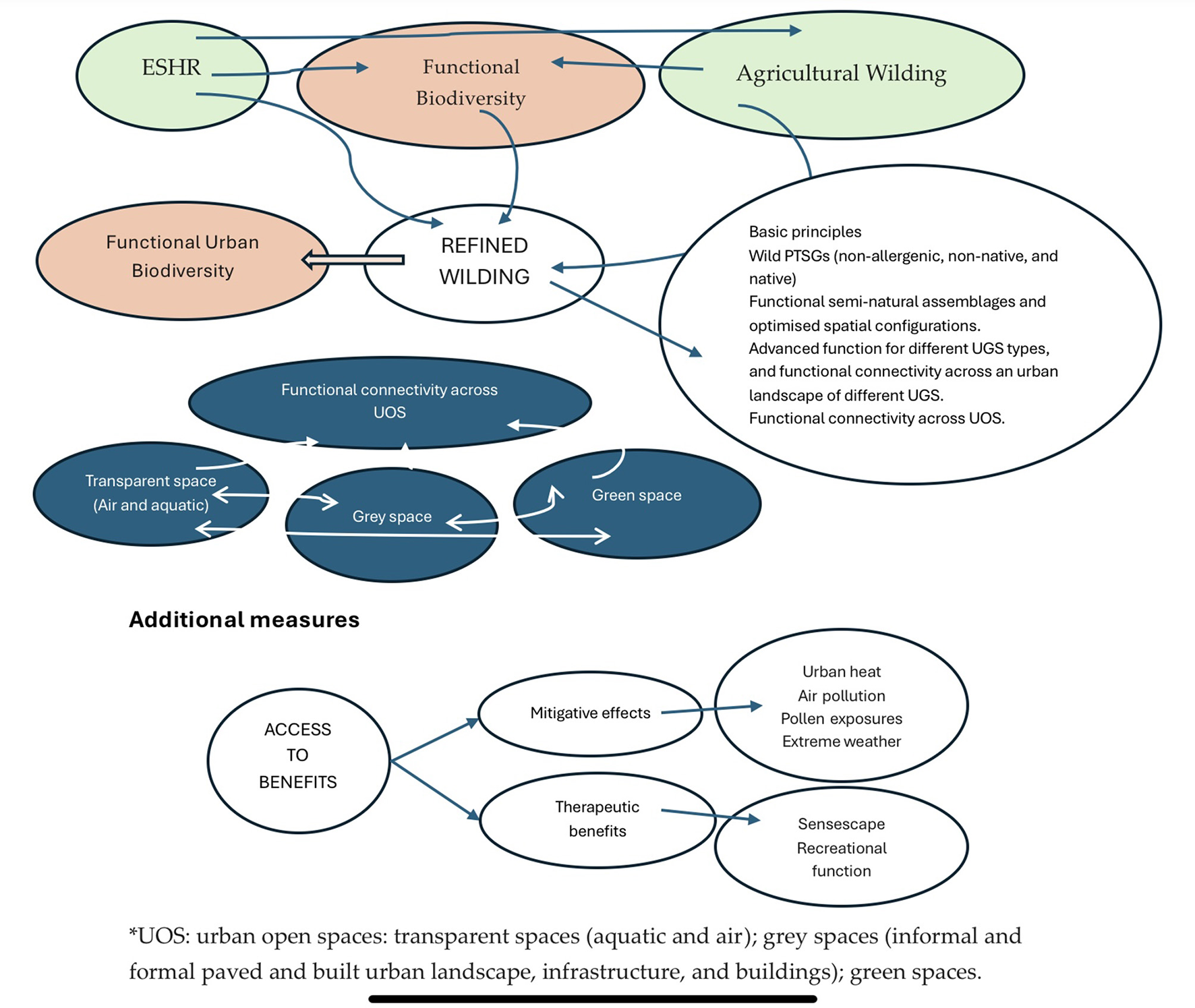

Refined wilding for functional urban biodiversity

I suggest refined wilding and functional urban biodiversity as a concept and theory (Vogt, 2025a,b,c), that can guide and optimize urban planning to effectively integrate, preserve and increase greenery even in dense cities. It works toward a functional connectivity across UGS types, and across three UOS, green, transparent (air and aquatic), and gray spaces (informal and formal paved and built urban landscapes). And an advanced function of UGS of different types, and function across UGS of any urban landscape (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Refined wilding for functional urban biodiversity, preceding concepts and theory. *UOS: urban open spaces: transparent spaces (aquatic and air); grey spaces (informal and formal paved and built urban landscape, infrastructure, and buildings); green spaces. Refined wilding: design of UGS and functional connectivity across UGS, and across UOS as positive influential flows. Theory. ° Concept; ° Urban Open Spaces (UOS) for functional connectivity; —> Refined wilding to Functional urban biodiversity; → Concept to concept, concept to theory; Influential flows between UOS and functional connectivity. Green spaces are also referred to as biodiversity and natural-environment spaces. Green spaces are traditionally referred to for urban landscapes.

As a conceptual frame it can determine need for benefits and optimizes effectiveness when guiding and responsive to local landscape measure planning, design, implementation and monitoring. It can also guide measures past the categories of benefit of access for optimized outcomes.

Wild refined UGS are part of a plan and design for wild refined urban landscapes of advanced function for dense cities. They are assemblages of wild plant, tree, shrubs, and grasses (PTSG) selections, that are native, and non-native, and non-allergenic. Their assemblages (PTSGs) and spatial distributions (UGS and PTSGs) are informed by the ESHR as ecologically functional and of varying complexities and densities1, at a system and landscape level. Ecological sensitivity as an external input (Vogt, 2021a,b) determines design and planning of functional wild PTSG selections and assemblages, and adequate UOS integration. The human realities aspect of the ESHR provides less tangible effectiveness measures, aesthetic preferences, access to resources, knowledge sets, capability in design, and influences ecological sensitivity and refined wilding measures specific to PTSG selections, assemblages, and spatial configuration as a matter of ecological function.

It is a concept and theory applicable to any UGS type, including spontaneous and informal or abandoned UGS, with various definitions of informal compared to formal UGS to consider. The resulting UGS are semi-natural green systems, with little human hand, or human interaction or modification required. This limited need for maintaining through strategic planning, design and PTSG selections is significant for long term outcomes. The varying densities and spatial distributions and emphasis on advanced function through design and planning address effective greening for mitigation for different stressors and therapeutic benefits. It also addresses coordinated integration with infrastructure and buildings, and anthropogenic factors like use of different urban areas (Syeda et al., 2025), and aesthetic preferences for UGS, cityscapes and facades (Vogt, 2025c).

Refined wilding and conceptual clarification

Supporting concepts encourage a prioritizing of nature in cities. They variably integrate adjoined built urban landscapes to the design of urban nature (Beatley, 2011) and variably define and encourage an optimized quality and configuration across an urban landscape. The quality of UGS can address ecological functions, health (Coppel and Wüstemann, 2017), and benefits of equitable access (Kabisch et al., 2017), as a mitigative and therapeutic benefit and of across UOS functions as an optimized outcome. Conceptual clarifications for renaturing, novel urban ecosystems (Vogt, 2025d, table 1; Vogt, 2025b, table 5), wildlife friendly, and biophillic design are in Vogt, 2025a,b,c,d). Two additional concepts that refined wilding complements and adds specificity to are biophillic cities and urban rewilding. Biophillic cities (Beatley, 2011) is a UGS adjoined to built urban landscape design concept. Refined wilding recognizes across UOS connectivity, and aesthetic preferences as a limitation, and specifies parameters for adjoined greenery, taking biophillic cities further for the natural-environment. Urban rewilding works from rewilding originally a concept for apex predator wilding, with PTSGs being reestablished as habitat (Vogt, 2021a,b). It is a distinct concept in terms of landscape type, and taxa focus before PTSG as habitat, as distinct from wilding for agricultural landscapes (Vogt, 2021a,b). Urban rewilding implies a landscape consideration but is focused on returning an urban landscape to a wild landscape through rewilded urban spaces (Jin et al., 2024).

Refined wilding is complementary by landscape level considerations and functional connectivity across UOS but specifies wild native and non-native non-allergenic PTSG selections, and functional assemblages for various UGS types with spatial configuration and design specifically and conceptually guided by functional urban biodiversity.

Is greening optimised?

Effective greening for dense cities optimizes spatial configurations, functional connectivity across a landscape, with positive influential flows and integration between UOS, and different UGS types. It is mitigative, therapeutically beneficial, and protective of ESHR. Summarized as:

-

(i) How synergistic mitigation and therapeutic benefits are provisioned.

I suggest mitigative effects and therapeutic benefits (Vogt, 2025b, table 2) as two categories of benefits from access to UGS. Parameters for measure reach distant, peri-urban, and across and integrated to paved cityscape UGS, and UOS, block, city, outer city, and across urban landscape levels. Indirectly they are measures of quality of life and can result in lowered costs by health and even urban landscape damage and repair (Fu et al., 2024). Therapeutic benefits are summarized in sensescape, and other access categories.

(ii) How functional urban biodiversity in a dense city is optimized.

(iii) How local measures of need compare to already provisioned to determine how effectively green a dense city is or could be informed by functional urban biodiversity and refined wilding principles.

Optimized decision making for design, spatial planning, and equitable access to urban greenery

Equitable access to functional urban biodiversity, recognizes a need for ecological knowledge (Xu et al., 2025), alongside addressing the urban landscape barriers and motivations for urban greenery, framed by human realities. Interdisciplinary and advanced knowledge coordinated by refined wilding can guide and optimize decision making (Feng, 2024) for spatial planning and design options for urban green in dense cities, balancing need with feasibility. The concept and this article respond to localized measures of provisioned and needed, and distanced sources of effects, and provisions.

Synergistic mitigative effect

Table 1, lists examples of synergistic mitigative effects for three stressors. Synergistic mitigation requires significant measure and planning which can be conceptually guided. For example, mitigating effectively for one stressor, cooling, requires different UGS types and different cooling functions, surface, air temperatures, localized cooling from elevated spaces, green roofs and vertical greenery (Ling et al., 2020) in high density cities, and thermal benefits from urban forests and green corridors, relevant to microclimate and climate regulation (Lin and Li, 2025). The quality in vegetative density and composition of coverage is most specifically addressed with refined wilding which can reach different UGS types and provide mitigative function.

Table 1

| Stressor | Worsened synergistic effect from | Worsened synergistic effect on UOS types | Health conditions | Influential variables | Mitigative effect | Synergistic mitigative strategies of other UOS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Air pollution | • Urban heat • Pollen content |

• Transparent spaces • Green spaces • Gray spaces |

Respiratory, Cardiovascular, Dermatological, Oncology, Mental health, Neurodegenerative | • Dependent on traffic emissions • Climatic variations |

• Air quality improvementa • PM2.5 |

• Green infrastructure, road surfaces and transport efficiencies, compact and pedestrian cities, Biophillic, passive, and other sustainable design • Functional urban biodiversity |

| Urban heat | • Air pollution • Pollen content |

• Transparent spaces • Green spaces • Gray spaces |

Mortality And worsened by effects of air pollution | Dependent on green coverage, type, and quality. And then other environmental factors including local climate and urban composition | • Urban cooling • Thermal regulation • Microclimates • Air circulation • Regional ventilation |

• Permeable surfaces, compact and pedestrian cities, Biophillic, passive, and other sustainable design • Green infrastructure, road surfaces and public transport efficiencies • Functional urban biodiversity |

| Allergenic pollen content | • Air pollution • Urban heat |

• Transparent spaces • Air |

Respiratory, Cardiovascular, Dermatological, Oncology, Mental health, Neurodegenerative | • Local climate • Climatic variance • Wind speeds • Extreme weather |

• Lowered exposures • Lowered content in air particles • Decreasing wind pollination, Decreasing allergenic pollen sources |

• Urban greenery specific • Air quality and pollen content monitoring • Functional urban biodiversity for UGS design, PTSG selections, and UGS spatial configurations* • Behavior change |

Synergistic effects of combined stressors: how advanced function can address mitigation for human health and quality of UOS.

Increasing effect from multiple stressors on human health and UOS. Starts with one factor and increases in effect with additional factors and with effect on UOS, then on human health. The significance of the effect increases to the base of the shape and as the color lightens. Air pollution: affects UOS and combined with urban heat (Lin and Li, 2025) and pollen content and exposure is causal to human conditions. Urban heat: affects UOS and combined with air pollution and pollen content and exposure is causal to health conditions. Allergenic pollen content affects aerobiome, combined with air pollution and urban heat is causal to health conditions (Anenberg et al., 2020). The cause to health conditions increases with combined or synergistic stressors. *Practical example of refined wilding for mitigative strategies in the main content. aBi et al., 2024.

Practical example of advanced function from refined wilding

Strategies for lowering allergenic pollen exposures include preventative and responsive strategies, as exposures while variable are a significant human health risk, and are part of a synergistic mitigative effect (Vogt, 2025b, table 4) and Table 1. Refined wilding can prioritize:

Identifying the location of allergenic PTSGs that pose significant risk of exposure

The conceptual guidance encourages an understanding of source of exposure, which can be peri-urban or inner urban.

Inventories such as S-API (Sun et al., 2023), and allergenic and non-allergenic tree species identification and assessments (Vogt, 2025b) can inform identification, and guide planning.

Once located, strategies for spatial planning and functional wild PTSG selections and assemblages; replacing allergenic PTSGs and adapting behavior around pollen season can lead to a mitigation.

Preventative

Refined wilding and functional urban biodiversity for new or redesigned urban greenery: non-allergenic wild PTSG selections.

Replacing allergenic PTSGs with non-allergenic.

Responsive

Optimizing spatial configurations, PTSG selections and assemblages, to reduce pollen emissions aligned with refined wilding and functional urban biodiversity.

Reducing wind pollination with biotic pollination, using functional wild PTSG selections and companion planting near allergenic PTSGs, decreasing pollen emissions (Nguyen et al., 2023). Urban environment stressors can decrease pollinator activity and must be factored in, as stressors can negatively affect different UOS.

Refined wilding encourages functional non-allergenic selections of wild PTSGs; and functional assemblages that mitigate against either synergistic effects, or against allergenic pollen content in the air. In advanced function, it can be responsive to pollen exposures through wild refined design at an urban landscape level and optimized spatial configuration. It therefore ensures a positive influence between UGS and transparent spaces with human realities considerations and outcomes.

Conclusion: Functionally biodiverse dense cities

How green dense cities can be is answered with optimized urban planning responsive to localized measures of need guided by refined wilding to ensure functionally biodiverse dense cities that functionally influence other green spaces, and transparent and gray spaces across an urban landscape. Design, planning and strategies that reach advanced functional urban biodiversity, synergistic mitigation, and therapeutic benefits.

Functional urban biodiversity introduces a designed refined wild which could be as aesthetically acceptable as traditional designs while provisioning multiple functions. It is a concept for imagining a green dense city and provides parameters for determining how functionally biodiverse it can be. A capability to design, maintain, plan, and implement, identifying appropriate UGS type selection, size, shape, and connectivity with the urban form can reach realistic answers and long-term outcomes for green dense cities, and can reach aesthetic norms and preferences for a cityscape. Hidden inclusion, street, elevated and vertical, and small space strategies, and UOS functional connectivity can realistically green a dense city.

Statements

Author contributions

MV: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author declares that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1.^Densities are referred to as complexities for the ESHR, as densities for the NDVI are often used to measure UGS.

References

1

Anenberg S. C. Haines S. Wang E. Nassikas N. Kinney P. L. (2020). Synergistic health effects of air pollution, temperature, and pollen exposure: a systematic review of epidemiological evidence. Environ. Health19:130. doi: 10.1186/s12940-020-00681-z

2

Beatley T. (2011). Biophillic Cities: Integrating Nature Into Urban Design and Planning. Washington, DC: Island Press.

3

Bi S. Chen M. Tian Z. Jiang P. Dai F. Wang G. (2024). Optimizing urban green spaces for air quality improvement: a multiscale land use/land cover synergy practical framework in Wuhan, China. Land13:1020. doi: 10.3390/land13071020

4

Bonfantini G. B. Galimberti B. Ventura E. (2025). There are no ‘solutions' in urban planning: against the idea of a ready-made urbanism and the 15-minute city's uncritical branding. Land14:2090. doi: 10.3390/land14102090

5

Castells-Quintana D. Dienesch E. Krause M. (2021). Air pollution in an urban world: A global view on density, cities and emissions. Ecol. Econ.189:107153. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2021.107153

6

Coppel G. Wüstemann H. (2017). The impact of urban green space on health in Berlin, Germany: empirical findings and implications for urban planning. Landscape Urban Plan.167, 410–418. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2017.06.015

7

Farkas J. Z. Hoyk E. de Morais M. B. Csomós G. (2023). A systematic review of urban green space research over the last 30 years: a bibliometric analysis. Heliyon9:e13406. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e13406

8

Feng S. (2024). Implementation of decision support system for ecological environment planning of urban Green Space. Ecol. Chem. Eng. 31, 177–192. doi: 10.2478/eces-2024-0012

9

Fu Q. Zheng Z. Nazirul M. Sarker I. (2024). Combating urban heat: systematic review of urban resilience and adaptation strategies. Heliyon10:e37001. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e37001

10

Haaland C. van den Bosch C. K. (2015). Challenges and strategies for urban green-space planning in cities undergoing densification: a review. Urban Forest. Urban Green.41, 760–771. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2015.07.009

11

Jin X. Qian S. Yuan J. (2024). Identifying urban rewilding opportunity spaces in a metropolis: Chongqing as an example. Ecol. Indic.160:111778 doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2024.111778

12

Kabisch N. Korn H. Stadler J. Bonn A. (Eds.) (2017). “Nature-based solutions to climate change adaptation in Urban Areas: linkages between science,” in Policy and Practice (Cham: Springer). doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-56091-5

13

Lin H. Li X. (2025). The role of urban green spaces in mitigating the urban heat island effect: a systematic review from the perspective of types and mechanisms. Sustainability17:6132. doi: 10.3390/su17136132

14

Ling T.-Y. Hung W.-K. Lin C.-T. Lu M. (2020). Dealing with green gentrification and vertical green-related urban well-being: a contextual-based design framework. Sustainability12:10020. doi: 10.3390/su122310020

15

Manisalidis I. Stavropoulou E. Stavropoulos A. Bezirtzoglou E. (2020). Environmental and health impacts of air pollution: a review. Front. Public Health8:14. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00014

16

Nguyen H. Schack J. M. Everett M. (2023). Drivers of cultivated and wild plant pollination in urban agroecosystems. Basic Appl. Ecol.72, 82–92. doi: 10.1016/j.baae.2023.09.003

17

Song J. Przybysz A. Zhu C. (2025). Revealing the contribution of urban green spaces to improving the thermal environment under realistic stressors and their interaction. Sustain. Cities. Soc.126:106426. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2025.106426

18

Sun F. Zhang J. Yang R. Liu S. Ma J. Lin X. et al . (2023). Study on microclimate and thermal comfort in small urban green spaces in Tokyo, Japan—A Case Study of Chuo Ward. Sustainability15:16555. doi: 10.3390/su152416555

19

Syeda A. Q. A. Castillo-Villar K. K. Alaeddini A. (2025). Sustainable urban heat island mitigation through machine learning: integrating physical and social determinants for evidence-based urban policy. Sustainability17:7040. doi: 10.3390/su17157040

20

Vogt M. (2025a). Functional biodiversity for urban planning: access to mitigative effects and therapeutic benefits of UGS. Urban Sci. 9:372. doi: 10.3390/urbansci9090372

21

Vogt M. (2025b). Refined wilding for functional biodiversity in urban landscapes: a verification and contextualisation. Urban Sci.9:21. doi: 10.3390/urbansci9020021

22

Vogt M. (2025c). Refined wilding and urban forests: conceptual guidance for a more significant urban green space type. Forests16:1087. doi: 10.3390/f16071087

23

Vogt M. (2025d). Refined wilding and functional biodiversity in smart cities for improved sustainable urban development. Land14:1284. doi: 10.3390/land14061284

24

Vogt M. A. B. (2021a). Agricultural wilding: rewilding for agricultural landscapes through an increase in wild productive systems. J. Environ. Manag.284:112050. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.112050

25

Vogt M. A. B. (2021b). Ecological sensitivity within human realities concept for improved functional biodiversity outcomes in agricultural systems and landscapes. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 8:163 doi: 10.1057/s41599-021-00837-3

26

WHO Team . (2023). Assessing the value of urban green and blue spaces for health and well-being. Regional Office for Europe. WHO/EURO:2023-7508-47275-69347

27

Xu Z. Shuqing Zhao S. Shen P. Yuan W. Liu S. (2025). The value of small urban green spaces in mitigating urban heat: a fine-grained nationwide analysis. Agric. Forest Meteorol.373:110739. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2025.110739

Summary

Keywords

refined wilding, functional urban biodiversity, functional landscape connectivity, synergistic effects and benefits, optimized spatial planning, integrating urban greenery

Citation

Vogt MAB (2025) How green does a dense city need to be? Functional urban biodiversity for dense cities. Front. Sustain. Cities 7:1722129. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2025.1722129

Received

10 October 2025

Revised

12 November 2025

Accepted

17 November 2025

Published

18 December 2025

Volume

7 - 2025

Edited by

Pedzisai Kowe, Midlands State University, Zimbabwe

Reviewed by

Esin Özlem Aktuglu Aktan, Yildiz Technical University, Türkiye

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Vogt.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Melissa Anne Beryl Vogt, melissaanneberylvogt@gmail.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.