- 1Faculty of Tourism and Geography, University of Rovira i Virgili, Tarragona, Catalonia, Spain

- 2Department of Communication and Culture, BI Norwegian Business School, Oslo, Norway

Short-term rental (STR) platforms hold promise for promoting inclusive tourism, although the digital divide risks barring certain groups from reaping these benefits. Existing research has analyzed the impacts of STR platforms but there is a lack of evidence on impact perceptions, especially as they relate to socio-demographic variables. To address this shortcoming and using digital inequality theory, we report the results of a survey in the United States and the United Kingdom. We find that age is a significant factor in shaping perceptions and engagement with STR platforms. Younger individuals have a more positive outlook toward STRs and are more likely to use them. Education and income also influence STR use. American respondents generally had more positive perceptions of STR impacts yet showed less engagement with the platforms than their British counterparts. These insights can inform strategies to mitigate digital inequalities and optimize the inclusivity of STR platforms.

1 Introduction

The sharing economy is based on peer-to-peer interactions to acquire, provide, or share access to goods, and services via digital platforms (Schlagwein et al., 2020). Over the years, it has become mainly associated with large players such as Uber and Airbnb. The sharing economy has notably transformed the accommodation market, with short-term rental (STR) options becoming an appealing alternative for property owners compared to traditional long-term rentals (Shokoohyar et al., 2020). In the global lodging industry, STRs, also known as home-sharing, is a growing sector (O'Neill and Yeon, 2023). STR platforms such as Airbnb play a significant role in matching the increased accommodation demand with the growing number of tourists (Garcia-López et al., 2020). Moreover, STR platforms enable individuals to earn extra income by renting out unused space to travelers (Barron et al., 2021).

While tourism more generally often benefits the middle and upper classes (Jamal and Camargo, 2014), STRs may foster inclusive tourism and promote certain objectives of sustainable tourism development as outlined in Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 10 (Lutz and Angelovska, 2021). On the demand side, STRs—brokered through platforms such as Airbnb—are attractive because they come with lower prices and greater convenience, which benefits resource-constrained individuals. On the supply side, STRs open opportunities for extra revenue and income generation (Gassmann et al., 2021; Lutz and Angelovska, 2021). However, STR platforms could also exacerbate inequality by disproportionately impacting disadvantaged individuals. Even though city residents might seem like they have common interests, their rights and concerns can differ considerably, with power and fairness in cities being unevenly distributed, where some groups have more advantages than others (Torkington and Ribeiro, 2022). Several scholars have explored how STR platforms affect local communities, thus showing inequality implications (Masoumi Dinan et al., 2025). For example, the impacts of STR platforms on housing prices, new business opportunities, gentrification, the hotel industry, and regulatory issues have been explored (Barron et al., 2021; Bianco et al., 2022; Franco and Santos, 2021; Garcia-López et al., 2020; Maté-Sánchez-Val, 2021; Robertson et al., 2022; Soh and Seo, 2023; Yeon et al., 2020), with much of the research stressing the disruptive nature of STR platforms. However, the perceived impacts of STRs have received less attention (Jordan and Moore, 2018; Lutz et al., 2024; Masoumi Dinan et al., 2025; Nieuwland and van Melik, 2020; Stergiou and Farmaki, 2020). Thus, evidence is limited on citizens' perceptions of STR platforms and their variation across social characteristics. Moreover, the growth of STRs has sparked debates on the need for regulations due to social issues (locals feeling alienated, poorer tourist experiences), economic disruptions (real estate market instability, dependence on tourism), and cultural and environmental concerns (damage to heritage sites and natural environments) (Benítez-Aurioles, 2021).

Understanding the relationship between socio-demographic characteristics of residents and their perceptions of STR impacts is crucial for developing balanced, fair, and effective policies that address the needs and concerns of all community members, while harnessing the economic potential of STRs. Nevertheless, this aspect has received insufficient academic attention. Moreover, the impact sociodemographic factors have on the use of STRs remains underexplored, including how age, income, education, and cultural background influence the use patterns of STR platforms. Therefore, this paper aims to address the following three questions:

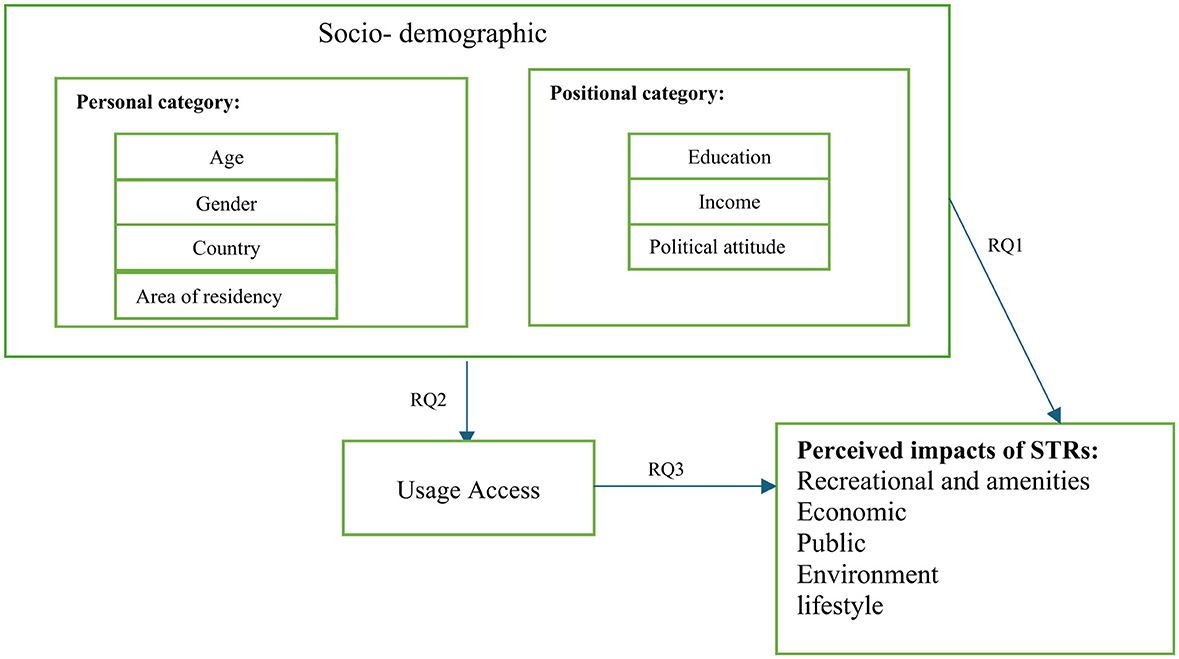

RQ1: How do personal and positional factors shape perceived STR impacts?

RQ2: How do personal and positional factors, affect the use of STR platforms?

RQ3: What is the difference in perceptions of the impacts of STRs between users and non-users of these platforms?

Our study, based on digital inequality theory (Lutz, 2019; Robinson et al., 2015), investigates these research questions both in the United States (US) and the United Kingdom (UK). By doing so, we provide implications for the tourism industry and impetus for inclusive, particularly through spotlighting marginalized individuals. Integrating these groups into the tourism economy not only provides growth opportunities for the tourism industry but can also foster equity and social cohesion. The results show the importance of creating inclusive policies and practices that ensure everyone can participate in and benefit from tourism-related activities. Moreover, understanding the varying perceptions of STRs across socio-demographic groups provides insights for policymakers and STR platforms. By analyzing these differences, they can tailor their policies and services to meet the specific needs and preferences of certain socio-demographic groups. This targeted approach can lead to more effective regulation, enhance user satisfaction, and ensure that the benefits of STRs are accessible to a broader segment of the population.

2 Literature review

2.1 Public opinion and attitudes about the impact of STR platforms

Perceptions of the impacts of STR platforms can be both positive and negative. Shin et al. (2023), merging social exchange and stakeholder theories, reveal that consumers prioritize sociocultural benefits, such as improved social relations, over economic gains, such as increased tourism revenue and job opportunities, when it comes to community resilience. In positive terms, STR platforms offer varied spaces and employment opportunities (Dogru et al., 2020), contributing to tax revenue and societal welfare (DiNatale et al., 2018). Additionally, they are viewed as a sustainable business model that can generate wealth without relying on financial support from governments (Masoumi Dinan et al., 2025; Midgett et al., 2017). Moreover, many consumers welcome the development of STR platforms due to their affordability, which opens the opportunity for tourism for groups that may otherwise have been excluded and provides an increased range of accommodation options for customers (Guttentag, 2015). This increased choice provided by STR platforms is evident in listings located in residential areas, which can offer a more authentic tourism experience (Bucher et al., 2018). All these impacts can be expected to be seen positively.

In negative terms, STR platforms are subject to criticism (Murillo et al., 2017) and are often portrayed by the media as disruptive (Dogru et al., 2020). One of the main concerns is the displacement of residents due to the gentrification of neighborhoods (Franco and Santos, 2021; Sans and Domínguez, 2016; Stergiou and Farmaki, 2020). Another concern is the impact STRs have on housing prices (Benítez-Aurioles and Tussyadiah, 2021). The widespread use of STRs has lowered some residents' quality of life due to increased noise, anti-social behavior, and tourism-related nuisances. This has led to changes in demand for local services and a weakening sense of community (Mody et al., 2019). Safety and health concerns (Hazée et al., 2019), discrimination (Lee et al., 2021) legal uncertainties (Rojanakit et al., 2022), and privacy issues (Lutz et al., 2018) have resulted in calls for greater regulation and more accountability of STR platforms (Akbari et al., 2022).

2.2 Inclusive tourism in a digital era

The rapid expansion of information and communication technologies (ICTs) in the tourism industry highlights an evolving digital landscape, with online platforms such as Expedia and TripAdvisor reshaping travel planning (Pouri and Hilty, 2021) and STR platforms such as Airbnb transforming the accommodation sector by scaling up traditional homestays (Bakker and Twining-Ward, 2018). While these digital innovations have increased access to tourism, their benefits are not equally distributed. The concept of inclusive tourism, which seeks to ensure equitable tourism opportunities for all, brings attention to these disparities (Scheyvens and Biddulph, 2018). For instance, according to Torabi (2024) tourism can help reduce poverty and promote economic growth in rural areas. Achieving inclusive tourism requires a flexible and evolving approach that engages diverse stakeholders (Nyanjom et al., 2018) and incorporates minority groups into the tourism workforce to foster sustainable industry growth (Hon and Gamor, 2022).

Although STR platforms may democratize accommodation services (Kadi et al., 2022), socio-demographic barriers continue to limit participation (Eichhorn et al., 2022). These platforms are often assumed to create economic opportunities for hosts and enhance access to lodging for travelers. However, their accessibility is not uniform. Digital literacy gaps and a lack of awareness can exclude certain groups from the benefits of the sharing economy (Angelovska et al., 2020, 2021; Eichhorn et al., 2022; Lutz and Angelovska, 2021). Moreover, the discourse on inclusive tourism must extend beyond STR platform users (i.e., guests and hosts) to consider broader socio-economic dynamics (Masoumi Dinan et al., 2025). This includes policymaking involvement, respectful self-representation in tourism markets, the expansion of tourism into underserved areas, and the local social impacts of STR activities (Scheyvens and Biddulph, 2018).

2.3 Digital inequality theory

Digital inequality research investigates the barriers that prevent individuals from fully participating in a digital society and adopting new technologies (Philip and Williams, 2019). At its core, digital inequality theory posits that existing social inequalities lead to disparities in access to digital technologies, which in turn reinforce and perpetuate those very inequalities (Van Dijk, 2005). Van Dijk's (2005) influential theory on the digital divide identifies four critical stages of digital access: motivational (the willingness to engage with digital tools), material (ownership of necessary devices and internet services), skills (digital literacy and competencies), and usage (diversity of digital activities and time spent online). Access across these stages is influenced by personal factors, such as age, gender, cognitive ability, and health, as well as positional factors, including education, employment, household income, and national context (Van Dijk, 2005, 2020). Research has consistently found that individuals from privileged backgrounds engage with digital technologies in more capital-enhancing ways than those from disadvantaged backgrounds, further widening socio-economic disparities (Hargittai, 2010; Lutz, 2019). At the core of digital inequality, individuals may or may not be motivated to engage in online activities. Even with motivation, they might still lack essential material resources like internet access or a compatible device, which are necessary for engaging with location-based apps. A third critical stage involves the skills needed to effectively use online services (Hargittai, 2010; Van Deursen et al., 2011; Van Dijk, 2005, 2020). Finally, individuals need the opportunity to apply their motivation, skills, and material access in actual usage. Van Dijk refers to this as usage access, which includes the need, occasion, obligation, time, or effort required to use technology. Usage is considered the ultimate goal of the adoption process.

Tourism scholars have examined the different impacts of STRs, for example on the housing market (DiNatale et al., 2018; Garcia-López et al., 2020; Robertson et al., 2022), hospitality, and over-tourism (Celata and Romano, 2022; O'Neill and Yeon, 2023; Soh and Seo, 2023). However, there is a noticeable lack of attention when it comes to the perceived impacts of platforms, especially through the lens of digital inequality and inclusive tourism (Lutz and Angelovska, 2021; Scheyvens and Biddulph, 2018; Van Dijk, 2005, 2020). By applying digital inequality theory, researchers can better understand how disparities in access and digital skills shape both the use and perceived impacts of STR platforms.

2.4 Theoretical framework and research model

One important strand of this research focuses on socio-demographic factors, exploring how age, gender, education, income, and place of residence influence STR perceptions. Nugroho and Numata (2022), for example, emphasize that residents' support for tourism development is closely tied to their socio-demographic backgrounds, because these backgrounds shape how they perceive economic gains versus social or environmental costs. In a study of coastal and hinterland residents, Sharma and Dyer (2009) found that proximity to tourist hubs shapes perceptions too: coastal residents benefit directly and therefore perceive tourism more favorably, while inland residents focus more on social impacts, like cultural shifts or changes in community identity.

According to digital inequality theory, residents' ability to participate in digital platforms such as Airbnb depends not only on having Internet access, but also on their digital literacy and ability to turn digital use into economic gains. Similar demographic factors come into play when residents assess sharing economy platforms. Almeida-García et al. (2016) demonstrate that educational background, birthplace, and length of residence all contribute to attitudes toward tourism. Likewise, Sharma and Gursoy (2015) suggest that age, gender, income, education, and occupation combine to shape evolving perceptions over time. Younger and middle-aged residents tend to see more economic promise in tourism (Hong Long and Kayat, 2011), while lower-income residents, often excluded from tourism's most profitable niches, express more skepticism (Julião et al., 2023).

Residents' personal characteristics (such as age, education, and income), combined with their digital capabilities, are likely to shape both how they perceive STR impacts and how (or whether) they engage with STR platforms in the first place. This leads to the following research questions:

RQ1: How do personal and positional factors shape perceived STR impacts?

RQ2: How do personal and positional factors, affect the use of STR platforms?

Additionally, Andriotis (2004) found that residents directly working in tourism hold more favorable views of its impacts than those who are economically detached from the sector. This divide deepens in the digital tourism economy, where non-users (often older, less affluent, or digitally disconnected residents) are more likely to see STRs as a driver of gentrification, cultural erosion, and community disruption. This tension is captured in the third research question:

RQ3: What is the difference in perceptions of the impacts of STRs between users and non-users of these platforms?

In the following, we integrate these insights from the digital inequality, inclusive tourism, and (perceived) impacts of STR platforms literature to derive our research model, which serves to answer the research questions. Our research model is a simplified version of Van Dijk's (2005, 2020) digital inequality theory. Participants were surveyed on their experience with specific STR platforms (e.g., Airbnb and HomeAway), distinguishing between non-users and users (as guests, hosts, or both). This data provides insights into participants' engagement with these platforms, personal categories (age, gender, country, area of residency) and positional categories (education, income, political attitude) from Van Dijk's model influence access and use of digital resources.

By examining these categories, we can understand the impact of STRs among different participant groups. Considering both personal and positional categories provides insights into how individual characteristics and societal factors shape digital inequalities. Figure 1 depicts the structural model based on digital inequality theory.

3 Methods

3.1 Survey design

We programmed an online survey in Qualtrics. Our survey started with a short description of STR platforms and with an informed consent page. Respondents were screened for their awareness of STR platforms (5 UK and 4 US respondents dropped out here) and their use of such platforms, directing them to relevant sections based on their response. Non-users were directed straight to the perceived impact questions. Users were further asked which of the five most prominent STR platforms they use including Airbnb, HomeAway, Booking.com, TripAdvisor FlipKey. Moreover, the use of STR platforms was measured by asking participants about their role as a guest, host, or both guest and host. Participants who had never used an STR platform were classified as level 1, those who had used it either as a guest or a host were categorized as level 2, and those who had experience in both roles (guest and host) were classified as level 3. We also clarified that we were interested in the use of more general-purpose platforms, such as Booking.com and Tripadvisor, only insofar as they are used for STR purposes. Accordingly, the respondents were further streamed into different sections: Guests were directed to the general perceived impact questions and guest-specific perceptions questions, hosts to the general perceived impact questions and host-specific questions, and guests and hosts were directed to answer all sections.

We used 14 items to measure the perceived impact of STR platforms in general (Table 1), refined from a pilot survey with 57 items (Miguel et al., 2022) that was based on different dimensions of impact (e.g., socio-cultural, economic, political, environmental, technological, see also Lutz et al., 2024 and Masoumi Dinan et al., 2025). The impact dimensions were not represented by predefined components/factors but consisted of individual items that were for the most part adapted from Mody et al. (2019). The survey participants had six response options for all impact items, 1-Very negative impact, 2-Somewhat negative impact, 3-No impact 4-Ambivalent impact, 5-Somewhat positive impact, and 6-Very positive impact (see Lutz et al., 2024 for a justification of this response format).

3.2 Data collection and descriptive statistics

We focused on the US and UK due to their significant STR market size and contrasting usage patterns (Woodward, 2024). Despite sharing the same language, the US and the UK have different STR use patterns, with a significant portion of use in the US driven by internal demand (Woodward, 2024). By contrast, the UK has a more internationally diverse guest composition (Office for National Statistics, 2019).

In June 2021, we launched the online survey in the UK and the US. We chose Prolific for participant recruitment due to its higher data quality compared to alternatives and its ability to provide representative samples (Palan and Schitter, 2018; Peer et al., 2017, 2022; Prolific, 2024). The representative sample has been successfully used for recent top publications in tourism (Kim, 2019) and beyond (Nelson-Coffey et al., 2021). It allowed us to collect a more generalizable sample with age, gender, and ethnic composition that mirrors the general population in both countries (Prolific, 2024). While acknowledging that some degree of self-selection bias is inevitable with online recruitment platforms, Prolific's screening tools and rigorous recruitment processes still yield a robust and diverse sample that enhances the representativeness of our data (Douglas et al., 2023).

After removing missing values due to screening and quality control through two attention checks, 358 respondents in the UK and 370 in the US remained (Total N = 728). The average age was 46.6 years in both the UK and the US. This is higher than the average age in both countries because we did not have minors in the survey. In total 50.90% identified as female, 48.21% as male, and the remaining participants chose another gender identification or preferred to self-identify. Education-wise, 4.40% reported having Middle school/junior high school, 13.87% a high school degree, 6.32% certificate program, 14.56% some college studies, 37.77% bachelor's or equivalent, 17.99% master's degree and 5.08% doctorate or equivalent. The most common area of residency is suburban, with a frequency of 30.08%, followed by big cities (>500K inhabitants) with 24.18%, small to medium-sized cities (< 500K inhabitants) with 23.49%, and finally rural areas with 22.25%.

The political attitude of respondents ranges from 1 to 10 (1 = very left-leaning; 10 = very right-leaning), with a mean of 4.47, suggesting that respondents hold a slightly left-leaning attitude (SD = 2.25). Regarding income, we used 17 predefined annual personal income levels, ranging from 0 to 4,999 to 150,000 or more (in either GBP or USD, depending on the country). The mean income level for both countries together is 7.72 which belongs to the 30,000 to 34,999 income category. Separated by country, the average income in the UK is between 20,000 and 29,999 GBP (5.90), while in the US, it is between 40,000 and 49,999 USD (9.43).

4 Results

4.1 Exploratory factor analysis (EFA)

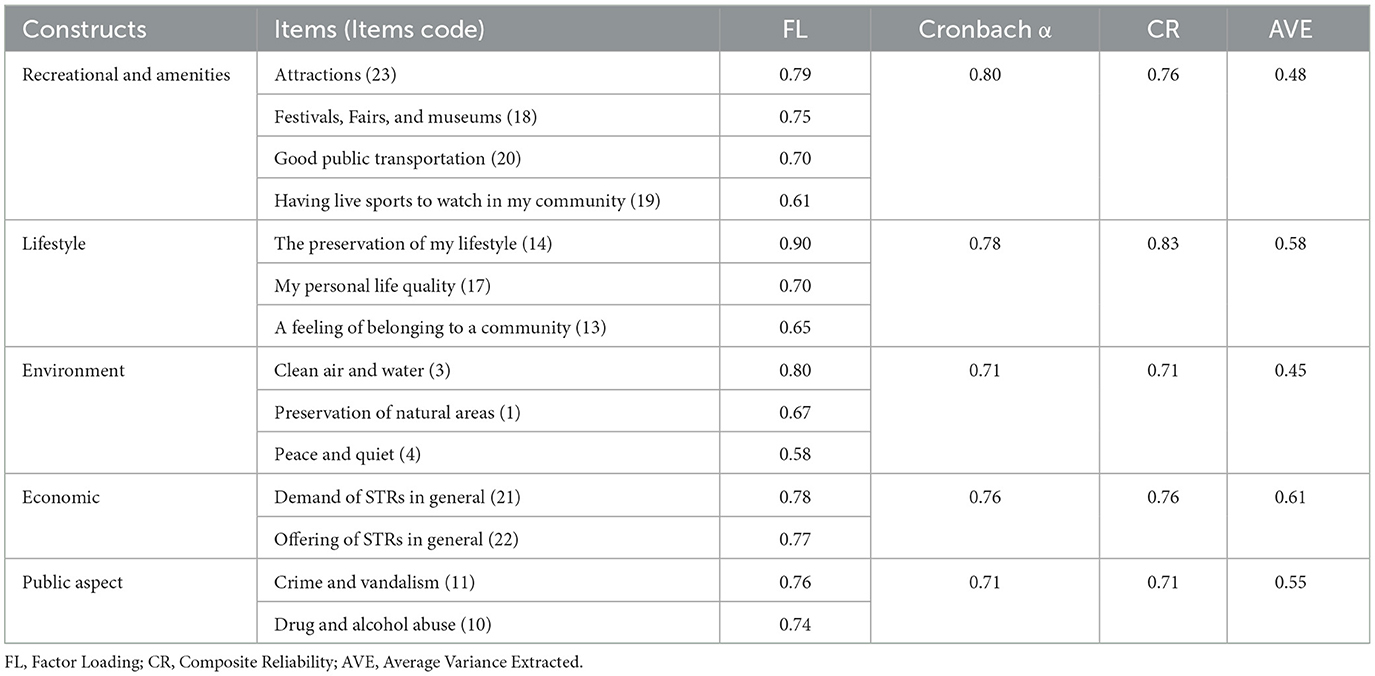

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) on 27 perceived impact items (see Appendix) eliminated 13 items falling below the threshold of 0.5 (Williams et al., 2010) or exhibiting high cross-loadings, resulting in a refined set of 14 items (see Table 1). Using Promax rotation and the Principal Axis Factoring method, the EFA resulted in five factors that explain 52% of the total variance: Factor 1 encompasses recreational and amenities aspects, Factor 2 focuses on lifestyle and community embeddedness, Factor 3 addresses impacts on the natural environment, Factor 4 reflects economic impacts related to STR supply and demand, and Factor 5 covers public nuisance aspects such as crime and vandalism.

4.2 Structural equation model (SEM)

We used Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) with the lavaan package in Rstudio (Rosseel, 2012), applying the Maximum Likelihood Robust method (MLR) for parameter estimation and model fit assessment. The model demonstrated good fit: df = 155 (chi-square = 301.69, p < 0.0001), TLI = 0.96, CFI = 0.94, SRMR = 0.027; RMSEA = 0.031. TLI and CFI exceed the recommended threshold of 0.90 and SRMR and RMSEA are below 0.08 and 0.06, respectively (Bentler and Bonett, 1980; Kline, 2023; Lei and Wu, 2007).

Construct validity is examined by assessing convergent and discriminant validity (Ping, 2004). Hair et al. (2014) suggest Cronbach's α and Composite Reliability (CR) scores above 0.70, and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) higher than 0.5. According to (Fornell and Larcker, 1981), if the CR is acceptable and higher than 0.6 the validity of the construct is still sufficient (Pervan et al., 2017). Table 1 indicates that values of Cronbach's α and composite reliability exceed the advised thresholds.

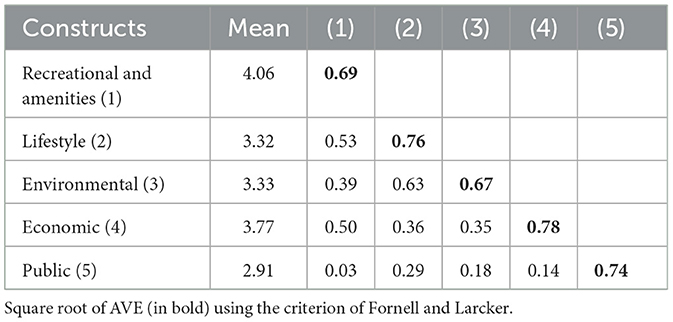

Discriminant validity is established by comparing the square roots of AVE for each construct with the correlations between the constructs (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). Table 2 shows that this is the case.

To answer RQ1, the relationship between the personal and positional categories and the perceived impact of STR was analyzed (see Appendix Table A2). There were no notable differences in the perceived impacts between female and male participants. Age significantly influenced perceptions of recreational, lifestyle, and economic impacts (p-value < 0.001, z-value = −5.466, −2.270, and −4.727, β = −0.246, −0.093, and 0.223), with younger individuals showing more positive views. Area of residence significantly shaped perceptions. Urban residents had the most positive views, with rural, suburban, and small to medium-sized city residents expressing more negative views on certain aspects. US residents had more positive perceptions of STR impacts compared to UK residents in various aspects, (recreational and amenities: p-value = 0.001, z-value = 3.298, β = 0.156; lifestyle: p-value = 0.015, z-value = 2.441, β = 0.106; environmental: p-value = 0.000, z-value = 3.602, β = 0.170; economic: p-value = 0.002, z-value = 3.602, β = 0.147). Neither income nor education showed significant associations with perceived STR impacts. There was no significant relationship between STR platform use and political attitudes. However, political attitudes significantly influenced perceptions of STR impacts. Right-leaning individuals had more positive perceptions of lifestyle, environmental, and economic aspects (p-value = 0.023, z-value = 2.274, β = 0.111; p-value = 0.002, z-value = 3.039, β = 0.165; p-value = 0.009, z-value = 2.623, β = 0.123 respectively), but more negative perceptions of public aspects compared to left-leaning respondents (p-value = 0.005, z-value = −2.825, β = −0.156)

Further analysis helped to answer RQ2, which covers the influence of personal and positional categories on STR platform use (Appendix Table A3). Gender and area of residency showed no significant effect. However, education, income, age, and country of residency had significant effects. Education and income positively influenced STR platform use (education: p = 0.006, z = 2.763, β = 0.109; income: p < 0.001, z = 4.525, β = 0.180). Age and US residency were negatively associated with use (age: z = −6.610, β = −0.246; US residency: z = −3.792, β = −0.141).

Finally and in relation to RQ3, no significant relationship was found between the perceived impacts of STRs and use of these platforms (Appendix Table A4).

5 Conclusion and implications

This study explored the perceived impacts and use patterns of STR platforms in the US and UK through the lens of digital inequality theory and inclusive tourism (Lutz, 2019; Robinson et al., 2015; Scheyvens and Biddulph, 2018; Van Dijk, 2005, 2020). The findings suggest that demographic factors such as age, country of residence, educational background, and income level significantly impact the use of STR platforms. Younger individuals, who tend to be more comfortable with digital technology, are more likely to engage with these platforms (Amaro et al., 2019; Bilgihan et al., 2014; Eichhorn et al., 2022). Furthermore, those with higher levels of education and income are presumably more frequent users due to greater digital literacy and access (Lutz and Angelovska, 2021; Newlands and Lutz, 2020; Smith, 2016). Interestingly, US-based individuals are less inclined to engage with STR platforms compared to their British counterparts. However, US residents tend to have a more positive attitude toward the STRs impacts. This observation suggests a notable divergence in the adoption and use of STR services between the two countries, warranting further investigation into the cultural, economic, and regulatory factors that might influence such contrasting patterns of STR platform use. Moreover, gender, and area of residency were not statistically significantly associated with the use of STR platforms, and the use level did not have an impact on the perceived impacts of STRs.

We also analyzed the relationship between socio-demographic characteristics and the perceived impacts of STRs. We found that age, country of residency, and area of residency influence the perceived impacts of STRs in some respects. Specifically, younger individuals tend to have a more favorable perception of the recreational, lifestyle, and economic impacts of STRs. This demographic seems to appreciate the convenience, leisure opportunities, and potential financial advantages that STRs offer. Conversely, age did not play a significant role in shaping perceptions regarding the environmental and public sphere impacts of STRs.

The analysis suggests that among various positional factors, only political attitude has a discernible influence on the perceived impacts of STRs. Individuals with a right-leaning political attitude are more likely to hold positive views of the impact of STRs. This correlation might reflect broader ideological beliefs related to property rights, economic freedom, and regulatory perspectives, which are often associated with conservative political thought.

5.1 Theoretical implications

Drawing on Van Dijk's (2005, 2020) digital inequality theory, which outlines the motivational, material, skills, and usage stages of digital access, the study demonstrates that inequalities in digital resources not only shape individuals' ability to engage with STR platforms but also affect the extent to which these platforms may democratize accommodation services. In parallel, the research investigates the perceived impacts of STRs, revealing that while these platforms have the potential to stimulate local tourism and provide innovative lodging options, their benefits are not distributed equally (Eichhorn et al., 2022; Lutz et al., 2024).

Moreover, our work fills a gap in understanding perceived STR impacts by integrating digital inequality theory and inclusive tourism and enriches previous research regarding the perceived impacts of STRs (Lutz et al., 2024; Masoumi Dinan et al., 2025; Martín Martín et al., 2021; Mody et al., 2019; Stergiou and Farmaki, 2020). Unlike some previous studies, we employ a quantitative approach and broaden the scope by including both US and UK samples. This enriches our understanding of socio-demographic influences on STR perceptions and identifies potentially disadvantaged groups (Jordan and Moore, 2018; Lutz et al., 2024; Miguel et al., 2022; Mody et al., 2019).

Our conclusions are consistent with the findings of Andreotti et al. (2017), suggesting that younger individuals, those with higher educational qualifications and with greater incomes are more inclined to use such sharing economy platforms. This aligns with digital inequality theory (Lutz, 2019; Lutz and Angelovska, 2021; Robinson et al., 2015; Van Dijk, 2005, 2020), which suggests that disparities in skills access and usage access create variations in digital platform engagement. Since younger individuals have higher exposure to digital tools and stronger technological competencies, they face fewer barriers in adopting and using STR services. Individuals with higher income and education levels are more likely to engage with STR platforms due to their greater access to digital resources, higher digital literacy, and familiarity with online transactions (Angelovska et al., 2020, 2021). This pattern aligns with digital inequality theory (Van Dijk, 2020), which posits that disparities in material access (availability of devices and internet connectivity) and skills access (digital literacy and competency) contribute to variations in digital engagement. Higher-income individuals typically have access to better technological infrastructure, including high-speed internet and advanced digital devices, reducing barriers to STR use. Similarly, individuals with higher education levels are more proficient in navigating digital platforms, assessing online reviews, and utilizing platform features effectively (Hargittai, 2002; Van Deursen and Van Dijk, 2014). In contrast, those with lower education and income may experience digital exclusion, limiting their participation in the STR economy and reinforcing socio-economic inequalities in tourism accessibility. This exclusion can limit the spread of economic benefits within a community, as the income generated from STRs will likely flow to a homogenous group that is younger, more educated, and has higher income. As a result, the potential for STRs to contribute to local economic development is diminished, as not all community members have the opportunity to participate as hosts or service providers.

Contrary to the findings by Huang and Yuan (2017) and Kim et al. (2013), who identified gender as a significant factor influencing online customer behavior in tourism, our research did not find gender to be a significant determinant in the use of STR platforms. This suggests that there is an equitable opportunity for all genders to engage with and benefit from STR platforms. Such gender neutrality in perceptions is an encouraging indicator of inclusivity within the STR marketplace. It implies that the economic and social opportunities afforded by STRs, such as supplemental income for hosts and affordable, diverse lodging options for travelers, are equally perceived by men and women. Significantly, STRs contribute to inclusive tourism, thereby supporting the attainment of SDG 10, which calls for reduced inequalities (Lutz and Angelovska, 2021). Furthermore, our findings align with research by Johnson and Mehta (2024), which suggests that the sharing economy is a digital commons that provides women access to networks and resources. This understanding of the sharing economy highlights its role as a potential facilitator of inclusivity.

Investigating the perceived impacts of STRs, the results indicate younger individuals exhibit a more favorable view of the impacts of STRs. Being active participants in the STR market, this demographic is likely to have their perception of STR impacts influenced positively. For example, they typically view the lifestyle and economic aspects of STRs in a positive light because they directly benefit from them. The social dimension of STRs resonates with the younger generation's values of openness and exchange. The interaction with guests from various cultural backgrounds is not merely a transaction but an opportunity for cultural exchange and building global networks. The positive perceptions of STRs by younger individuals can also be attributed to their lifestyle choices, which often prioritize experiences over possessions. The sharing economy model of STRs aligns with this preference, offering an authentic and localized travel experience that is sought after by many young travelers. Moreover, from a digital inequality standpoint (Van Dijk, 2005, 2020), younger cohorts typically possess higher digital literacy and better material access (e.g., smartphones, reliable internet). These advantages enhance their ability to discover, evaluate, and engage with STR platforms, thereby shaping more positive perceptions of the social and economic benefits.

In line with previous research, based on a study by Miguel et al. (2022) and the perceived impacts of STRs among UK residents exhibit an ambivalent yet moderately positive sentiment. However, this study highlights that US residents hold a comparatively more favorable perception of STRs (Lutz et al., 2024). According to Nieuwland and van Melik (2020), European cities tend to have more relaxed regulations for STRs compared to their American counterparts which typically enforce stricter rules, such as the necessity for permits, specific safety measures, and the provision of information by STR hosts. This difference can be attributed to the regulatory approaches adopted by European and American cities, to manage and mitigate the negative impacts associated with STRs.

Further analysis suggests that residents' perceptions of STRs vary significantly depending on their area of residence. Those living in rural areas, suburbs, and small to medium-sized cities generally hold a more negative view on at least one aspect of STRs when compared to their counterparts in larger cities. This variance in perception could be attributed to several factors. Residents in rural areas, suburbs, and smaller cities may experience the negative externalities of tourism more acutely. Without the infrastructure to support increased visitor numbers, these regions can suffer from traffic congestion, overuse of public spaces, and a strain on local resources. Furthermore, the economic benefits in these areas may be more dispersed or less visible, leading to a perception that STRs serve external visitors at the expense of the local community. The findings align with research by Sharma and Dyer (2009), which indicates a proximity effect. Those living closer to tourist attractions often benefit more directly from tourism and, therefore, tend to have a more favorable view of its impact. This proximity allows for easier access to the economic opportunities provided by tourism, including increased demand for local services and businesses. However, this proximity benefit might not be uniformly felt across different residential areas, especially when the capacity to absorb tourist activity is limited. In rural or less densely populated areas, residents may feel that tourism disrupts their lifestyle and environment, potentially leading to a negative perception of STRs. Moreover, a study by Philip and Williams (2019) on rural tourism in Scotland found that challenges with digital inequality were due to a lack willingness to use the Internet; rather, residents faced disadvantages because their Internet connection was inadequate for the online activities they wanted to engage in. This digital disadvantage prevents them from benefiting from STR platforms, ultimately shaping their support for tourism based on their perceptions of its advantages and disadvantages (Nugroho and Numata, 2022).

Right-leaning individuals may view STRs favorably as they align with property rights by Segal and Whinston (2013), which posits that property rights grant the owner the ability to use and benefit from an asset, exclude others from it, and transfer these rights if they choose. This viewpoint is supported by Friedman (2017) who argues for minimal government interference in private property decisions, which could be extrapolated to support the freedom to rent out one's property via STR platforms.

Contrary to our expectations, our analysis did not reveal a significant association between STR platform use and perceived STR impacts. In fact, this result indicates that the frequency of platform use does not have any significant effect on perceptions of STR impacts. This suggests that perceptions of STRs are likely shaped by other factors such as personal values, media coverage, local context, or indirect experiences. In other words, being an active participant in the STR market does not automatically lead to more favorable or unfavorable perceptions compared to those who have never used these platforms at all.

5.2 Practical implications

Our findings provide valuable insights for STR platforms. Particularly, STR platforms should cultivate a more comprehensive positive impact and overall user experience. This approach can contribute to the establishment of a coherent brand image and help in building legitimacy within the market (Newlands and Lutz, 2020). The outcomes of this study hold practical value for advocates of STR platforms, enabling them to tailor their strategies according to specific demographic profiles, ensuring a more inclusive approach. Government and policymakers need to invest in tourism infrastructure, particularly in rural and suburban areas. This investment could improve residents' perceptions of STRs, as the absence of such support may lead to negative views, as discussed by Garcia-López et al. (2020). Platform service providers should craft inclusive tourism policies that address the needs of underrepresented demographics in STR participation. This approach is supported by Andreotti et al. (2017), who highlighted the tendency of younger, more educated, and wealthier individuals to engage with STRs, suggesting the need for policies that also enable older and less affluent community members to benefit from the STR economy. For example, they can offer amenities or create more authentic experiences designed to attract older individuals, encouraging their active participation as both guests and hosts on these platforms. Examining the perceived impacts of STRs through the framework of digital inequality theory and inclusive tourism enables policymakers to formulate policies that are fairer and more encompassing, effectively tackling the distinct hurdles encountered by various societal groups within the digital sharing economy.

5.3 Limitations and future research

Our study has limitations, which provide directions for future research. We used cross-sectional data during Covid-19, which may have affected the responses. Longitudinal studies are needed to examine changes over time. The study's focus on Western, English-speaking countries may limit the wider applicability of its findings; future research should include a diverse range of countries. Additionally, further research should investigate how different residential areas affect STR perceptions. Our reliance on Prolific for recruiting participants means that there could be selection bias, with younger and tech-savvy respondents over-represented—a demographic that also features prominently among users of STR platforms (Andreotti et al., 2017; Angelovska et al., 2020, 2021; Eichhorn et al., 2022; Smith, 2016). We tried to address this issue through employing Prolific's representative sample option, which uses quotas for age, gender and ethnicity to mirror the population distribution in the US and UK (Prolific, 2024). Thus, the findings are more generalizable and robust than a convenience sample or a non-quota sample. Nevertheless, the perceived impacts of STR platforms and the use of such platforms might look slightly different in a random sample. We encourage future studies to rely on truly representative samples, for example through random-digital dialing or in-person stratified random sampling. Moreover, our quantitative research design means that the article favors breadth over depth. We could not discuss perceived impact or use dynamics of STR platforms in specific geographies or communities within the US and UK. Future studies should complement our findings with more immersive and context-specific findings, for example through case studies of specific communities affected by STR use and platforms, connecting digital inequality theory to localized experiences. Finally, the small number of hosts in our sample limited our analysis. Increasing the number of host participants will provide a fuller picture of STR dynamics.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The requirement of ethical approval was waived by the larger project that this survey and study formed part of was funded by the Research Council of Norway. At the time of conducting the survey, no institutional ethical approval was required. However, the study complies with ethical guidelines regarding informed consent and did not target vulnerable populations. The study involved humans because the larger project that this survey and study formed part of was funded by the Research Council of Norway. At the time of conducting the survey, no institutional ethical approval was required. However, the study complies with ethical guidelines regarding informed consent and did not target vulnerable populations. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by Research Council of Norway, grant 275347 Future Ways of Working in the Digital Economy and 299178 Algorithmic Accountability.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsut.2025.1561748/full#supplementary-material

References

Akbari, M., Foroudi, P., Khodayari, M., Zaman Fashami, R., Shahabaldini parizi, Z., and Shahriari, E. (2022). Sharing your assets: a holistic review of sharing economy. J. Bus. Res. 140, 604–625. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.11.027

Almeida-García, F., Peláez-Fernández, M. Á., Balbuena-Vázquez, A., and Cortés-Macias, R. (2016). Residents' perceptions of tourism development in Benalmádena (Spain). Tour. Manag. 54, 259–274. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2015.11.007

Amaro, S., Andreu, L., and Huang, S. (2019). Millenials' intentions to book on Airbnb. Curr. Issues Tour. 22, 2284–2298. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2018.1448368

Andreotti, A., Anselmi, G., Eichhorn, T., Hoffmann, C. P., Jürss, S., and Micheli, M. (2017). European perspectives on participation in the sharing economy. SSRN Electron. J. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3046550

Andriotis, K. (2004). The perceived impact of tourism development by Cretan residents. Tour. Hosp. Plan. Dev. 1, 123–144. doi: 10.1080/1479053042000251061

Angelovska, J., Ceh Casni, A., and Lutz, C. (2020). Turning consumers into providers in the sharing economy: exploring the impacts of demographics and motives. Ekonomska Misao i Praksa 29, 79–100.

Angelovska, J., Ceh Casni, A., and Lutz, C. (2021). “The influence of demographics, attitudinal and behavioural characteristics on motives to participate in the sharing economy and expected benefits of participation,” in Becoming a platform in Europe: On the governance of the collaborative economy, Eds M. Teli and C. Bassetti (Norwell, MA: Now Publishers), pp. 35–58.

Bakker, M., and Twining-Ward, L. (2018). Tourism and the sharing economy: Policy and potential of Sustainable peer-to-peer accommodation. World Bank (2018). Available online at: https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/161471537537641836/tourism-and-the-sharing-economy-policy-potential-of-sustainable-peer-to-peer-accommodation

Barron, K., Kung, E., and Proserpio, D. (2021). The effect of home-sharing on house prices and rents: Evidence from Airbnb. Mark. Sci. 40, 23–47. doi: 10.1287/mksc.2020.1227

Benítez-Aurioles, B. (2021). A proposal to regulate the peer-to-peer market for tourist accommodation. Int. J. Tour. Res. 23, 70–78. doi: 10.1002/jtr.2393

Benítez-Aurioles, B., and Tussyadiah, I. (2021). What Airbnb does to the housing market. Ann. Tour. Res. 90:103108. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2020.103108

Bentler, P. M., and Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychol. Bull. 88, 588–606. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.88.3.588

Bianco, S., Zach, F. J., and Singal, M. (2022). Disruptor recognition and market value of incumbent firms: airbnb and the lodging industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 48, 84–104. doi: 10.1177/10963480221085215

Bilgihan, A., Peng, C., and Kandampully, J. (2014). Generation Y's dining information seeking and sharing behavior on social networking sites: an exploratory study. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 26, 349–366. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-11-2012-0220

Bucher, E., Fieseler, C., Fleck, M., and Lutz, C. (2018). Authenticity and the sharing economy. Acad. Manag. Discov. 4, 294–313. doi: 10.5465/amd.2016.0161

Celata, F., and Romano, A. (2022). Overtourism and online short-term rental platforms in Italian cities. J. Sustain. Tour. 30, 1–20. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2020.1788568

DiNatale, S., Lewis, R., and Parker, R. (2018). Short-term rentals in small cities in Oregon: Impacts and regulations. Land Use Policy. 79, 407–423. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.08.023

Dogru, T., Hanks, L., Mody, M., Suess, C., and Sirakaya-Turk, E. (2020). The effects of Airbnb on hotel performance: evidence from cities beyond the United States. Tour. Manag. 79:104090. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104090

Douglas, B. D., Ewell, P. J., and Brauer, M. (2023). Data quality in online human-subjects research: comparisons between MTurk, Prolific, CloudResearch, Qualtrics, and SONA. PLoS One 18:e0279720. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0279720

Eichhorn, T., Jürss, S., and Hoffmann, C. P. (2022). Dimensions of digital inequality in the sharing economy. Inf. Commun. Soc. 25, 395–412. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2020.1791218

Fornell, C., and Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 18:382. doi: 10.1177/002224378101800313

Franco, S. F., and Santos, C. D. (2021). The impact of Airbnb on residential property values and rents: evidence from Portugal. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 88:103667. doi: 10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2021.103667

Friedman, M. (2017). “61. Capitalism and freedom,” in Democracy Ed. R. Blaug (New York, NY: Columbia University Press), pp. 344–349.

Garcia-López, M. À., Jofre-Monseny, J., Martínez-Mazza, R., and Segú, M. (2020). Do short-term rental platforms affect housing markets? Evidence from Airbnb in Barcelona. J. Urban Econ. 119:103278. doi: 10.1016/j.jue.2020.103278

Gassmann, S. E., Nunkoo, R., Tiberius, V., and Kraus, S. (2021). My home is your castle: forecasting the future of accommodation sharing. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 33, 467–489. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-06-2020-0596

Guttentag, D. (2015). Airbnb: disruptive innovation and the rise of an informal tourism accommodation sector. Curr. Issues Tour. 18, 1192–1217. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2013.827159

Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., and Kuppelwieser, V. G. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): an emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 26, 106–121. doi: 10.1108/EBR-10-2013-0128

Hargittai, E. (2002). Second-level digital divide: differences in people's online skills. First Monday 7. doi: 10.5210/fm.v7i4.942

Hargittai, E. (2010). Digital Na(t)ives? Variation in internet skills and uses among members of the “net generation.” Sociol. Inq. 80, 92–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-682X.2009.00317.x

Hazée, S., Van Vaerenbergh, Y., Delcourt, C., and Warlop, L. (2019). Sharing goods? Yuck, no! An investigation of consumers' contamination concerns about access-based services. J. Serv. Res. 22, 256–271. doi: 10.1177/1094670519838622

Hon, A. H. Y., and Gamor, E. (2022). The inclusion of minority groups in tourism workforce: Proposition of an impression management framework through the lens of corporate social responsibility. Int. J. Tour. Res. 24, 216–226. doi: 10.1002/jtr.2495

Hong Long, P., and Kayat, K. (2011). Residents' perceptions of tourism impact and their support for tourism development: the case study of Cuc Phuong National Park, Ninh Binh province, Vietnam. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 4, 123–146. doi: 10.54055/ejtr.v4i2.70

Huang, Z., and Yuan, L. (2017). “Gender differences in tourism website usability: an empirical study,” in Design, user experience, and usability: Understanding users and contexts, eds. A. Marcus and W. Wang (New York: Springer), pp. 453–461.

Jamal, T., and Camargo, B. A. (2014). Sustainable tourism, justice and an ethic of care: toward the just destination. J. Sustain. Tour. 22, 11–30. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2013.786084

Johnson, A. G., and Mehta, B. (2024). Fostering the inclusion of women as entrepreneurs in the sharing economy through collaboration: a commons approach using the institutional analysis and development framework. J. Sustain. Tour. 32, 560–578. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2022.2091582

Jordan, E. J., and Moore, J. (2018). An in-depth exploration of residents' perceived impacts of transient vacation rentals. J. Travel Tour. Mark 35, 90–101. doi: 10.1080/10548408.2017.1315844

Julião, J., Gaspar, M., Farinha, L., and Trindade, M. A. M. (2023). Sharing economy in the new hospitality: consumer perspective. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 6, 1447–1463. doi: 10.1108/JHTI-08-2021-0198

Kadi, J., Plank, L., and Seidl, R. (2022). Airbnb as a tool for inclusive tourism? Tour. Geogr. 24, 669–691. doi: 10.1080/14616688.2019.1654541

Kim, B. (2019). Understanding key antecedents of consumer loyalty toward sharing-economy platforms: the case of Airbnb. Sustainability 11:5195. doi: 10.3390/su11195195

Kim, M. J., Lee, C. K., and Chung, N. (2013). Investigating the role of trust and gender in online tourism shopping in South Korea. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 37, 377–401. doi: 10.1177/1096348012436377

Kline, R. B. (2023). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (5th Edn). New York: Guilford Press.

Lee, K., Hakstian, A. M., and Williams, J. D. (2021). Creating a world where anyone can belong anywhere: consumer equality in the sharing economy. J. Bus. Res. 130, 221–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.03.036

Lei, P. W., and Wu, Q. (2007). Introduction to structural equation modeling: issues and practical considerations. Educ. Meas. Issues Pract. 26, 33–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-3992.2007.00099.x

Lutz, C. (2019). Digital inequalities in the age of artificial intelligence and big data. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 1, 141–148. doi: 10.1002/hbe2.140

Lutz, C., and Angelovska, J. (2021). “The sharing economy and its implications for inclusive tourism,” in Emerging transformations in tourism and hospitality, eds. A. Farmaki and N. Pappas (Abingdon: Routledge), pp. 35–52.

Lutz, C., Hoffmann, C. P., Bucher, E., and Fieseler, C. (2018). The role of privacy concerns in the sharing economy. Inf. Commun. Soc. 21, 1472–1492. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2017.1339726

Lutz, C., Majetić, F., Miguel, C., Perez-Vega, R., and Jones, B. (2024). The perceived impacts of short-term rental platforms: comparing the United States and United Kingdom. Tech. Soc. 77:102586. doi: 10.1016/j.techsoc.2024.102586

Martín Martín, J. M., Prados-Castillo, J. F., de Castro-Pardo, M., and Jimenez Aguilera, J. D. D. (2021). Exploring conflicts between stakeholders in tourism industry. Citizen attitude toward peer-to-peer accommodation platforms. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 32, 697–721. doi: 10.1108/IJCMA-12-2020-0201

Masoumi Dinan, M., Lutz, C., and Poli, N. (2025). Residents' perspectives on short-term rental platforms through a sustainability lens. Curr. Issues Tour. 1–17. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2025.2453588

Maté-Sánchez-Val, M. (2021). The complementary and substitutive impact of Airbnb on The bankruptcy of traditional hotels in the City of Barcelona. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 45, 610–628. doi: 10.1177/1096348020950810

Midgett, C., Bendickson, J. S., Muldoon, J., and Solomon, S. J. (2017). The sharing economy and sustainability: a case for AirBnB. Small Bus. Inst. J. 13, 51–71.

Miguel, C., Lutz, C., Alonso-Almeida, M. M., Jones, B., Majeti,ć, F., and Perez-Vega, R. (2022). “Perceived impacts of short-term rentals in the local community in the UK,” in Peer-to-peer accommodation and community resilience: Implications for sustainable development, Eds. A. Farmaki, D. Ioannides, and S. Kladou (Oxfordshire: CABI), pp. 55–67.

Mody, M., Suess, C., and Dogru, T. (2019). Not in my backyard? Is the anti-Airbnb discourse truly warranted? Ann. Tour. Res. 74, 198–203. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2018.05.004

Murillo, D., Buckland, H., and Val, E. (2017). When the sharing economy becomes neoliberalism on steroids: unravelling the controversies. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 125, 66–76. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2017.05.024

Nelson-Coffey, S. K., O'Brien, M. M., Braunstein, B. M., Mickelson, K. D., and Ha, T. (2021). Health behavior adherence and emotional adjustment during the COVID-19 pandemic in a US nationally representative sample: the roles of prosocial motivation and gratitude. Soc. Sci. Med. 284:114243. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114243

Newlands, G., and Lutz, C. (2020). Fairness, legitimacy and the regulation of home-sharing platforms. Int. J. Contem. Hosp. Manag. 32, 3177–3197. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-08-2019-0733

Nieuwland, S., and van Melik, R. (2020). Regulating Airbnb: how cities deal with perceived negative externalities of short-term rentals. Curr. Issues Tour. 23, 811–825. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2018.1504899

Nugroho, P., and Numata, S. (2022). Influence of sociodemographic characteristics on the support of an emerging community-based tourism destination in Gunung Ciremai National Park, Indonesia. J. Sustain. Forest. 41, 51–76. doi: 10.1080/10549811.2020.1841007

Nyanjom, J., Boxall, K., and Slaven, J. (2018). Towards inclusive tourism? Stakeholder collaboration in the development of accessible tourism. Tour. Geogr. 20, 675–697. doi: 10.1080/14616688.2018.1477828

Office for National Statistics (2019). Inbound visits and spend: quarterly, regional. Available online at: https://www.visitbritain.org/research-insights/inbound-visits-and-spend-quarterly-regional?country=~2260_2250_1100_1000_1204_1201_1190_1060_1208_1120_1020_103 (accessed March 14, 2025).

O'Neill, J. W., and Yeon, J. (2023). Comprehensive effects of short-term rental platforms across hotel types in US and international destinations. Cornell. Hosp. Q. 64, 5–21. doi: 10.1177/19389655211033527

Palan, S., and Schitter, C. (2018). Prolific.ac—A subject pool for online experiments. J. Behav. Exp. Finance. 17, 22–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jbef.2017.12.004

Peer, E., Brandimarte, L., Samat, S., and Acquisti, A. (2017). Beyond the turk: alternative platforms for crowdsourcing behavioral research. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 70, 153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2017.01.006

Peer, E., Rothschild, D., Gordon, A., Evernden, Z., and Damer, E. (2022). Data quality of platforms and panels for online behavioral research. Behav. Res. Method 54, 1643–1662. doi: 10.3758/s13428-021-01694-3

Pervan, M., Curak, M., and Pavic Kramaric, T. (2017). The influence of industry characteristics and dynamic capabilities on firms' profitability. J. Int. Financ. Stud. 6, 4. doi: 10.3390/ijfs6010004

Philip, L., and Williams, F. (2019). Remote rural home based businesses and digital inequalities: understanding needs and expectations in a digitally underserved community. J. Rural Stud. 68, 306–318. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2018.09.011

Ping, R. A. (2004). On assuring valid measures for theoretical models using survey data. J. Bus. Res. 57, 125–141. doi: 10.1016/S0148-2963(01)00297-1

Pouri, M. J., and Hilty, L. M. (2021). The digital sharing economy: a confluence of technical and social sharing. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 38, 127–139. doi: 10.1016/j.eist.2020.12.003

Prolific (2024). Representative samples on Prolific. Prolific Help Page. Available online at: https://researcher-help.prolific.com/hc/en-gb/articles/360019236753-Representative-samples (accessed March 14, 2025).

Robertson, D., Oliver, C., and Nost, E. (2022). Short-term rentals as digitally-mediated tourism gentrification: impacts on housing in New Orleans. Tour. Geogr. 24, 954–977. doi: 10.1080/14616688.2020.1765011

Robinson, L., Cotten, S. R., Ono, H., Quan-Haase, A., Mesch, G., Chen, W., et al. (2015). Digital inequalities and why they matter. Inf. Commun. Soc. 18, 569–582. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2015.1012532

Rojanakit, P., Torres de Oliveira, R., and Dulleck, U. (2022). The sharing economy: A critical review and research agenda. J. Bus. Res. 139, 1317–1334. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.10.045

Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 48, 1–36. doi: 10.18637/jss.v048.i02

Sans, A. A., and Domínguez, A. Q. (2016). “Unravelling Airbnb: Urban perspectives from Barcelona,” in Reinventing the local in tourism: Producing, consuming and negotiating place, Eds. A. P. Russo and G. Richards (Berlin: De Gruyter), pp. 209–228.

Scheyvens, R., and Biddulph, R. (2018). Inclusive tourism development. Tourism Geographies 20, 589–609. doi: 10.1080/14616688.2017.1381985

Schlagwein, D., Schoder, D., and Spindeldreher, K. (2020). Consolidated, systemic conceptualization, and definition of the “sharing economy.” J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 71, 817–838. doi: 10.1002/asi.24300

Segal, I., and Whinston, M. D. (2013). “Property rights,” in The Handbook of Organizational Economics, eds. R. Gibbons and J. Roberts (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press), 100–158.

Sharma, B., and Dyer, P. (2009). An investigation of differences in residents' perceptions on the Sunshine Coast: tourism impacts and demographic variables. Tour Geogr. 11, 187–213. doi: 10.1080/14616680902827159

Sharma, B., and Gursoy, D. (2015). An examination of changes in residents' perceptions of tourism impacts over time: the impact of residents' socio-demographic characteristics. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 20, 1332–1352. doi: 10.1080/10941665.2014.982665

Shin, H. W., Yoon, S., Jung, S., and Fan, A. (2023). Risk or benefit? Economic and sociocultural impact of P2P accommodation on community resilience, consumer perception and behavioral intention. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 35, 1448–1469. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-12-2021-1561

Shokoohyar, S., Sobhani, A., and Sobhani, A. (2020). Determinants of rental strategy: short-term vs long-term rental strategy. Int. J. Contem. Hosp. Manag. 13, 3873–3894. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-03-2020-0185

Smith, A. W. (2016). Shared, collaborative and on demand: the new digital economy. Pew Research Center, 19 May 2016. Available online at: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2016/05/19/the-new-digital-economy (accessed March 14, 2025).

Soh, J., and Seo, K. (2023). An analysis of the impact of short-term vacation rentals on the hotel industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 47, 760–771. doi: 10.1177/10963480211019110

Stergiou, D. P., and Farmaki, A. (2020). Resident perceptions of the impacts of P2P accommodation: implications for neighbourhoods. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 91:102411. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.102411

Torabi, Z.-A. (2024). Breaking barriers: how the rural poor engage in tourism activities without external support in selected Iranian villages. Front. Sustain. Tour. 3:1404013. doi: 10.3389/frsut.2024.1404013

Torkington, K., and Ribeiro, F. P. (2022). Whose right to the city? An analysis of the mediatized politics of place surrounding alojamento local issues in Lisbon and Porto. J. Sustain. Tour. 30, 1060–1079. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2020.1849230

Van Deursen, A., and Van Dijk, J. (2014). The digital divide shifts to differences in usage. New Media Soc. 16, 507–526. doi: 10.1177/1461444813487959

Van Deursen, A., van Dijk, J., and Peters, O. (2011). Rethinking Internet skills: the contribution of gender, age, education, internet experience, and hours online to medium- and content-related internet skills. Poetics 39, 125–144. doi: 10.1016/j.poetic.2011.02.001

Williams, B., Onsman, A., Brown, T., Andrys Onsman, P., and Ted Brown, P. (2010). Exploratory factor analysis: a five-step guide for novices. Aust. J. Med. Sci. 8, 1–13. doi: 10.33151/ajp.8.3.93

Woodward. (2024). Airbnb Statistics [2024]: User & Market Growth Data. Available online at: https://www.searchlogistics.com/learn/statistics/airbnb-statistics/ (accessed March 14, 2025).

Keywords: digital inequality, inclusive tourism, short-term rental platforms, sharing economy, perceived Impact, digital divide, sustainable tourism, short-term rentals

Citation: Masoumi Dinan M and Lutz C (2025) Studying short-term rental platform perceptions and use through a digital inequality lens. Front. Sustain. Tour. 4:1561748. doi: 10.3389/frsut.2025.1561748

Received: 16 January 2025; Accepted: 07 April 2025;

Published: 02 May 2025.

Edited by:

Michael O'Regan, Glasgow Caledonian University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Anne-Marie Hakstian, Salem State University, United StatesWei Yin, Southeast University, China

Adalberto Santos-Júnior, Federal University of Pelotas, Brazil

Copyright © 2025 Masoumi Dinan and Lutz. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Christoph Lutz, Y2hyaXN0b3BoLmx1dHpAYmkubm8=

†ORCID: Mona Masoumi Dinan orcid.org/0000-0003-2251-606X

Christoph Lutz orcid.org/0000-0003-4389-6006

Mona Masoumi Dinan1†

Mona Masoumi Dinan1† Christoph Lutz

Christoph Lutz