- 1School of Hospitality and Tourism, Auckland University of Technology, Auckland, New Zealand

- 2Office of the Vice Chancellor, Auckland University of Technology, Auckland, New Zealand

Introduction: Balancing conservation efforts with tourism development poses significant challenges in Small islands. Waiheke Island, located in New Zealand's inner Hauraki Gulf, is both a popular residential location and a popular tourism destination facing similar challenges in governing tourism and conservation. This study examined the characteristics of the local residential community, conservation and tourism governance, the environmental and social impacts of tourism, and nature conservation efforts on the island.

Methods: A qualitative case study approach was employed, involving interviews with stakeholders, field observation and review of secondary data sources. The research explored governance complexities, power imbalances, and stakeholder dynamics that shape community participation in tourism and conservation decision-making.

Results and discussion: The findings reveal a complex governance landscape marked by both strengths and challenges. The research highlights the pivotal role of community-driven governance, with grassroots initiatives demonstrating remarkable adaptive capacity in addressing governance gaps. The Waiheke Local Board emerged as a crucial mediator between competing interests, while the integration of Māori perspectives through documents like Essentially Waiheke reflects growing recognition of indigenous knowledge systems. However, the study also uncovers tensions, including fragmented decision-making where regional authorities override local preferences, and the need for further inclusion of local views on governance. The current governance system, which is influenced by the environmental-socioeconomic dynamics, creates a paradox where effective actors (such as grassroots initiatives/groups and tourism actors) lack appropriate inclusion in decision-making, while regional bodies retain decision-making power. The island's hybrid governance structure, blending formal institutions with informal networks, provides stability but requires more equitable power distribution to be fully effective. While collaborative efforts show promise, they are undermined by bureaucratic hurdles, inconsistent government support, and insufficient community engagement. The study proposes a framework for enhanced collaborative governance through strengthening local autonomy, formalizing co-governance arrangements, better supporting grassroots initiatives, and developing a community-driven destination management plan. These recommendations aim to reconcile the island's formal-informal governance duality while balancing tourism growth with environmental conservation and community wellbeing. The findings offer insights for other small islands facing similar governance challenges at the intersection of conservation and tourism development.

1 Introduction

Small islands face unique challenges due to their isolation, limited resources, and distinctive ecosystems (Kurniawan et al., 2019). While often popular tourist destinations for their natural beauty and cultural richness, these islands are particularly vulnerable to environmental degradation, resource depletion, and cultural disruption from tourism pressures (Fernandes and Pinho, 2017). Their small size and fragility mean they typically have restricted carrying capacities, where exceeding limits can lead to overcrowding and environmental damage (Nurhasanah and Van den Broeck, 2022). Effective governance and community participation are crucial for managing the delicate balance between tourism development and conservation on small islands (Charlie et al., 2013). Governance structures typically involve multiple levels of authority from national to local, alongside partnerships with communities, indigenous groups, private enterprises, and international organizations (Glaser et al., 2018). Many islands implement land use plans, zoning regulations, and environmental protection measures to ensure sustainable tourism growth (Sharpley and Ussi, 2014).

Community involvement stands as a cornerstone of successful island management, requiring transparent, inclusive stakeholder engagement (Chan et al., 2021). Best practices include community-based tourism initiatives, capacity-building programs, and collaborative networks that connect diverse stakeholders (Zhao, 2025). These approaches help empower local communities while preserving natural and cultural heritage (Tan et al., 2022). Despite progress, small islands continue to face challenges in tourism governance (Mycoo et al., 2022). Resource limitations, including funding shortages and insufficient technical expertise, hinder effective management (Barnett and Waters, 2016). External pressures such as climate change, natural disasters, and economic fluctuations further complicate conservation efforts (Bangwayo-Skeete and Skeete, 2022). Over-reliance on tourism can exacerbate vulnerabilities, creating socioeconomic inequality and environmental stress (Scheyvens and Momsen, 2020).

Waiheke Island in New Zealand's Hauraki Gulf exemplifies these dynamics. Its governance reflects a blend of local, regional, and national frameworks, shaped by its identity as a populated island with high environmental, cultural, and economic value (Allpress and Roberts, 2021). While administratively part of Auckland Council with local decision-making led by the Waiheke Local Board, tensions exist between centralized regional governance and the island's desire for autonomy. This governance complexity is further heightened by Waiheke's dual role as both tourist destination and community committed to environmental conservation, with grassroots initiatives playing a key advocacy role (Peart and Woodhouse, 2020). This article examines tourism governance complexities on Waiheke Island, exploring its governance arrangements, policy frameworks, and community-driven sustainability efforts. By analyzing contextual factors, stakeholder dynamics, collaborative barriers, and opportunities within Waiheke's governance system, this article addresses how tourism governance can be improved on the island. The goal is to identify strategic pathways for enhancing tourism governance, particularly within New Zealand's small island contexts. Through understanding Waiheke's experience, this study offers insights applicable to other small islands navigating similar challenges in balancing tourism development with conservation imperatives, highlighting the importance of adaptive governance, local knowledge integration, and community-led solutions in addressing social equity and environmental sustainability.

2 Literature review

2.1 Collaborative governance: definition, advantages, and limitations

In the sphere of governance, collaborative approaches have gained importance, especially in addressing complex issues such as sustainable tourism and natural resource management (Sentanu et al., 2023). In recent decades, a new type of governance has emerged as an alternative to managerial and adversarial approaches to formulating and enforcing policy (Emerson and Nabatchi, 2015). Collaborative governance has become a common term in public administration literature (Emerson and Nabatchi, 2015). It has gained considerable traction in the last few decades, partly because of the need to use cross-sectoral and intra-sector partnerships to provide solutions for public administration (Gash, 2022). The term “collaborative governance” refers to the process of convening public and private stakeholders with public agencies in group settings to facilitate consensus-driven decision-making (Ansell et al., 2020). It involves multiple stakeholders working together to make decisions, solve problems, leverage diverse perspectives and resources to produce value for the public that would not otherwise be possible (Voets et al., 2021).

Collaborative governance involves multistakeholder arrangements across different governance aspects, such as rule design, implementation, and enforcement (Rasche, 2010; Zadek, 2008). It requires understanding the preconditions for collaboration and the larger system of cross-sectoral governance (Voets et al., 2021). Previous literature has explored collaborative governance, emphasizing its multi-actor nature, involving governments, civil society, the private sector, and nonprofits (Finkelstein, 1995). Unlike top-down governance, which limits stakeholder participation and centralizes authority, collaborative governance connects the expertise and resources of multiple actors (Wang and Ran, 2021). Guided by principles of inclusivity, transparency, mutual respect, and shared responsibility, it seeks to ensure all voices are heard, fostering legitimacy and accountability (Emerson and Nabatchi, 2015). Collaborative governance emphasizes shared responsibility with stakeholders working together, sharing resources, and contributing to collective efforts to solve challenges and achieve common goals (Zadek, 2008).

Collaborative governance offers several benefits. It promotes collaborative decision- making, stakeholder ownership, resource optimisation, innovative solutions, trust, and relationship building (Emerson and Nabatchi, 2015; Gash, 2022). As noted by Börzel and Risse (2005), the ability of collaborative governance structures to identify workable solutions to governance issues is a key advantage. Rasche (2010) stated that collaborative governance models can effectively address social and environmental issues by combining resources and promoting learning among stakeholders. Although collaborative governance offers many benefits, it also presents several challenges including power imbalances, conflict of interests, limited financial and human resources, decision-making delays, and coordination challenges (Waardenburg et al., 2020). Whereas collective governance can improve problem-solving abilities, there is little proof that multistakeholder solutions are inherently more effective; a lot relies on the characteristics of the stakeholders and their interactions (Börzel and Risse, 2005). Another concern, noted by Bianchi et al. (2021) is that stakeholder power imbalances have the potential to compromise the legitimacy and efficacy of collaborative governance approaches. Waardenburg et al. (2020) added that the voices of under-represented or marginalized groups may be demoted by certain stakeholders' unbalanced influence, such as large firms or government organizations.

2.2 Collaborative governance models

In the past few decades, several collaborative governance models have emerged to explore how diverse stakeholders can work together to address complex challenges through shared decision-making and collective action. These frameworks provide a foundation for designing collaborative systems to address governance challenges effectively. Adaptive Co-Management, as proposed by Armitage et al. (2007), integrates flexibility and learning, allowing stakeholders to adapt to changing conditions while managing resources sustainably. Stakeholder Theory (Freeman, 1984) highlights the need to balance the interests of all parties involved, ensuring inclusivity and fairness in governance processes. Network Governance (Provan and Kenis, 2008) focuses on the structure and dynamics of relationships, emphasizing how networks can enhance coordination and resource sharing. Power and participation models, such as Arnstein's (1969) ladder of citizen participation and Pretty's (1995) typology, underscore the importance of empowering stakeholders and ensuring meaningful involvement in decision-making. Ansell and Gash's (2008) Collaborative Governance Framework identifies four broad variables: starting conditions, institutional design, leadership, and the collaborative process. The model outlines a structured process for effective collaboration among stakeholders. It begins with starting conditions, such as power imbalances, incentives for participation, and the history of cooperation or conflict, which shape the initial level of trust. The institutional design sets the stage with participatory inclusiveness, clear ground rules, and process transparency, supported by facilitative leadership that empowers participants. The collaborative process is the core, driven by trust-building, commitment to the process, and face-to-face dialogue. Key elements include mutual recognition of interdependence, shared ownership of the process, openness to mutual gains, and a clear mission. This promotes a shared understanding, where stakeholders define common problems and identify shared values. Intermediate outcomes, such as small wins, strategic plans, joint fact-finding, and good-faith negotiations, emerge from this process. These build momentum and trust, leading to final outcomes that reflect the collaborative efforts. At its core, the model emphasizes the importance of inclusive, transparent, and well-structured processes, supported by leadership and trust-building, to achieve meaningful collaboration and sustainable outcomes.

2.3 Community participation in conservation and tourism

Community participation, while not a new concept, remains a critical lens for understanding the dynamics of tourism and conservation governance. This study builds on existing literature by examining how collaborative governance frameworks can address the limitations of traditional participation models and advance more inclusive, equitable, and effective outcomes.

Operationally, community participation refers to the active involvement of local people in planning, decision-making, and resource management (McCloskey et al., 2011). It emphasizes empowering communities to manage resources, direct development, and share benefits from tourism and conservation initiatives (Rasoolimanesh et al., 2017). However, participation is not monolithic; it exists on a spectrum, ranging from manipulative or tokenistic involvement to genuine citizen power (Head, 2007; Pretty, 1995); (Tosun, 2006). For instance, Tosun (2006) distinguishes between coercive participation (minimal local voice), induced participation (limited influence), and spontaneous participation (community-led decision-making). These variations highlight the importance of moving beyond superficial engagement to ensure meaningful participation that aligns with community values and needs (Bianchi et al., 2021). The benefits of community participation are well-documented. It promotes trust, belonging, and credibility among community members (Rasoolimanesh and Jaafar, 2016), while enabling local people to shape development in ways that reflect their cultural, environmental, and socioeconomic priorities (Börzel and Risse, 2005). Participation also promotes environmental stewardship, biodiversity conservation, and cultural heritage preservation (Ojha et al., 2016). Economically, community-based tourism can create jobs, reduce poverty, and enhance resilience, particularly in marginalized areas (Mannigel, 2008). Furthermore, it enriches tourist experiences by offering authentic and culturally immersive interactions (Waardenburg et al., 2020). Despite these benefits, several barriers hinder effective participation. These include socioeconomic vulnerabilities, power imbalances, cultural and social barriers, lack of trust, institutional constraints, and conflicting interests (Kihima and Musila, 2019; Wondirad and Ewnetu, 2019; Wang et al., 2021). For example, marginalized groups often face limited access to resources and decision-making processes, perpetuating inequities in tourism and conservation governance (Stone and Stone, 2011).

This study contributes to the literature by exploring how collaborative governance can address these barriers and enhance community participation in tourism and conservation. By focusing on Waiheke Island, it examines how formal and informal institutions, stakeholder dynamics, and community-driven initiatives can create more inclusive and sustainable governance frameworks. The findings aim to inform policy and practice, offering actionable insights for improving tourism governance in small island contexts and beyond.

3 Study location—Waiheke Island

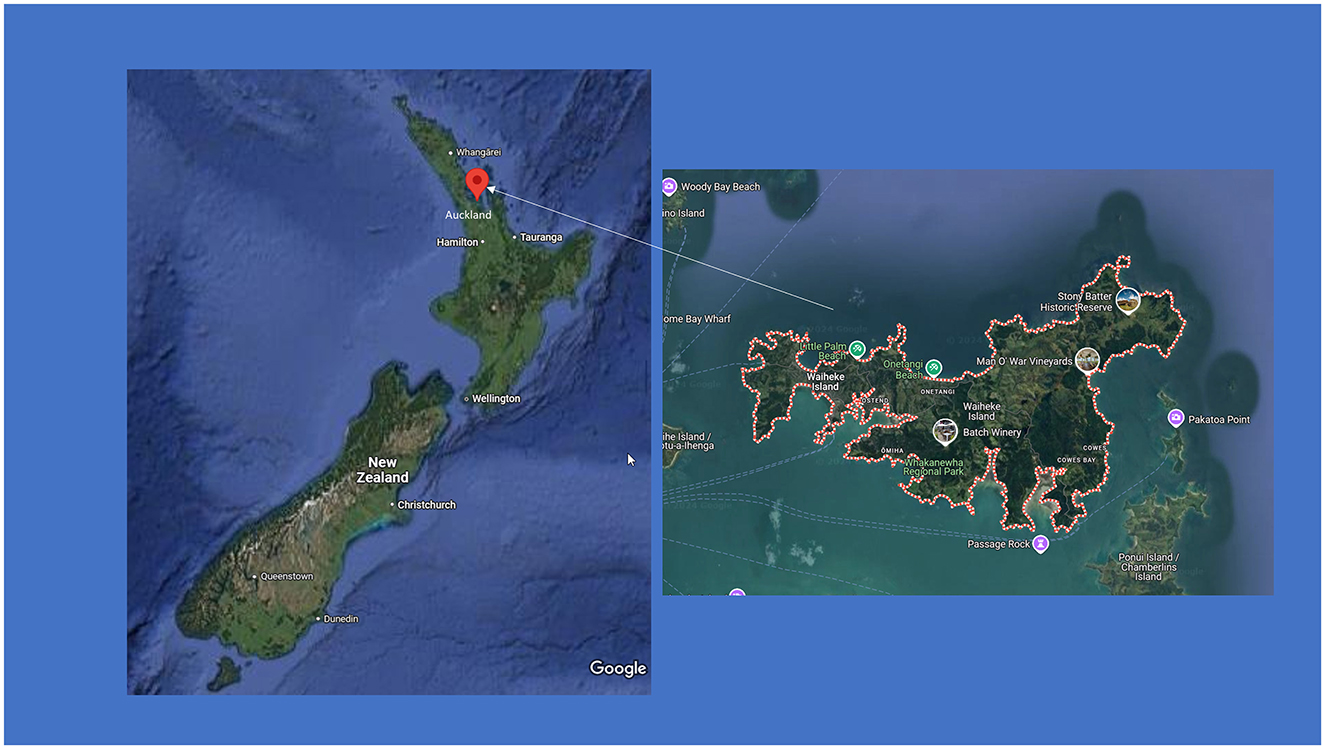

Waiheke Island, located in New Zealand's Hauraki Gulf, provides a valuable case study for exploring the challenges and opportunities of tourism governance in small communities. Its unique context, geographical location, cultural importance, and growing popularity as a tourist destination, offers insights into how collaborative governance can balance tourism development with environmental conservation and community wellbeing. Spanning approximately 92 square kilometers, Waiheke is a 35-min ferry ride from Auckland (see Figure 1). The island is home to rich biodiversity, including indigenous plants and threatened species, making conservation efforts critical (Baragwanath and Nicolas, 2014; Scott et al., 2019). Culturally, it holds deep significance for Māori tribes, particularly Ngāti Pāoa and Ngāti Maru, who have ancestral ties (mana whenua) to the land and actively participate in governance and cultural heritage preservation (Doolin, 1994).

The island's population has grown steadily, from 7,797 in 2006 to 9,790 in 2021, reflecting its appeal as a residential and tourist destination (Tātaki Auckland Unlimited, 2022a; Stats NZ, 2018). Residents, often called “Waihetians,” exhibit a strong sense of community and identity, distinct from Auckland. However, the island's growing popularity has intensified pressures on infrastructure, natural resources, and cultural heritage, raising questions about sustainable tourism management (Logie, 2016). Tourism is a key economic driver, supported by Waiheke's beaches, vineyards, festivals, and arts scene (Peart and Woodhouse, 2020). While tourism benefits local businesses, it also poses challenges such as environmental degradation, overdevelopment, and strain on infrastructure (Allpress and Roberts, 2021). These issues highlight the need for governance structures that balance economic development with environmental and cultural preservation. Governance on Waiheke involves formal institutions, such as the Auckland Council and Waiheke Local Board, which set policies for land use, environmental protection, and tourism development (Steenson, 2012). However, centralized decision-making and limited resources often constrain their effectiveness. Informal institutions, such as nonprofit organizations, sustainability activists, grassroots initiatives and tourism sector, play a role in addressing these gaps. Projects like Project Forever Waiheke and the Waiheke Marine Project demonstrate how local communities drive conservation through collective action. Community-driven initiatives, such as the Waiheke Resources Trust and Waiheke Biosphere Reserve, further highlight the importance of local participation in governance (Peart and Woodhouse, 2020). These efforts reflect the island's commitment to sustainability but also underscore the challenges of advancing collaboration among diverse stakeholders, including residents, Māori tribes, businesses, and tourists.

4 Methods

4.1 Research design

This article used a qualitative research approach using a single case study methodology. The use of qualitative research methods, particularly case study analysis, provides a comprehensive means of investigating social experiences (Houghton et al., 2015). The case study analysis involves an in-depth investigation of a specific phenomenon within its actual setting (Heale and Twycross, 2018). It enables a thorough inquiry of intricate social phenomena, providing insights into the complexities and dynamics of the research issue (Houghton et al., 2015). Examples of these phenomena include governance structures, decision-making procedures, and stakeholder relationships (Baskarada, 2014). In the context of tourism and conservation on Waiheke, the case study analysis supported the investigation of how various stakeholders interact, collaborate, negotiate, agree/disagree, and make decisions to balance conservation objectives with tourism development goals. The study also incorporated observational insights gathered and documented during interviews and field visits, such as observations from the field visits to the island, notes from the interviews and observations on stakeholder dynamics, which provided additional context for interpreting responses (Roulston and Choi, 2018). This approach aligns with the case study methodology's emphasis on capturing rich, contextualized data (Yin, 2018).

4.2 Data collection

Semi-structured interviews were conducted in 2023 with a targeted sample of 11 stakeholders encompassing government officials, nonprofit organizations, community leaders, conservationists, residents and representatives of the tourism and conservation sectors. Participant selection criteria were based on targeting people who have relevant experience, or opinions related to the island and the research topic (Roulston and Choi, 2018). The interviews offered an opportunity for face-to-face interaction with the participants to learn about their views, beliefs, attitudes, and actions (Roulston and Choi, 2018). Through interviews, it was possible to delve into people's experiences, examine their motivations and decision-making procedures, and identify the social connections and dynamics that influenced their perspectives (Minhat, 2015). The flexible approach employed during the semi-structured interviews allowed open-ended questioning and the investigation of emerging topics (Boeije, 2002). The study used a combination of purposive and snowball sampling to ensure a diverse range of perspectives. Stakeholders were selected to represent key sectors, including local government (e.g., Waiheke Local Board, Department of Conservation, Auckland Council), conservation groups, nonprofit organizations, local activists, and tourism operators. This approach ensured balanced representation across stakeholder groups.

The open-ended question approach allowed participants to think thoroughly about their experiences and provide insightful, in-depth answers (Luo and Wildemuth, 2017). Data collection procedures involved building rapport with participants, providing an atmosphere comfortable and supportive of open communication, and using active listening and probing strategies to obtain in-depth insights (Gill et al., 2008). During interviews, stakeholders were asked about the governance dynamics, structures and processes that govern tourism and conservation on Waiheke Island. This included inquiries about the roles and responsibilities of various stakeholders, decision-making mechanisms, coordination mechanisms between government agencies, NGOs, and community groups, and the degree of stakeholder participation in governance processes. Stakeholders were invited to discuss the challenges and opportunities facing governance of the island. To address potential challenges in data collection, such as scheduling conflicts and reluctance to participate, the study employed persistent follow-ups and flexible interview formats (e.g., in-person and virtual options). These measures ensured a high response rate and meaningful engagement with participants (Minhat, 2015). The study includes interview guide (Appendix 1) to enhance transparency and allow for replication.

The interview process was designed to uphold validity, ensure reliability, and effectively address ethical considerations (Roulston and Choi, 2018). To enhance validity, questions were carefully aligned with the study's objectives, ensuring meaningful and relevant findings. Reliability was supported by standardizing procedures, such as consistent phrasing of questions and maintaining similar interview conditions to minimize variability (Gill et al., 2008). Ethical integrity was maintained through informed consent, confidentiality, and creating a respectful and comfortable environment for participants throughout the interview process (Roulston and Choi, 2018). Participants gave their informed consent after being fully informed about the study's goals, methods, possible risks, and benefits. They were also given the option of leaving the study at any time without facing any consequences (Hopf, 2004). Measures were implemented to maintain participant anonymity and prevent the dissemination of sensitive information (Luo and Wildemuth, 2017).

The study achieved data saturation after 11 interviews, as recurring themes and patterns emerged consistently across the data. This indicates that additional interviews were unlikely to yield significantly new or divergent insights, confirming that the sample size was sufficient to capture the breadth and depth of participants' perspectives (Roulston and Choi, 2018). Additionally, the study prioritized quality and depth over quantity, focusing on rich, detailed perspectives from participants who represented a diverse range of stakeholder groups. By emphasizing in-depth exploration of key issues rather than aiming for a large number of interviews, the study ensured a thorough understanding of the complex dynamics surrounding governance, conservation, and tourism on Waiheke Island (Minhat, 2015). This approach aligns with qualitative research principles, where the goal is to achieve a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the phenomenon under investigation, rather than generalizing findings to a larger population (Hopf, 2004).

This study consulted a range of secondary data sources, including official tourism and conservation policy documents, local government plans, and community tourism and conservation submissions, plans, and reports. Key sources included Essentially Waiheke: A Village and Rural Communities Strategy (Auckland City Council, 2000), which provides a foundational framework for understanding Waiheke's unique character and community aspirations. Additionally, Project Forever Waiheke's (2021) report, ‘Waiheke is a community, not a commodity': Stakeholder perspectives on future Waiheke tourism, their 2023 submission to Waiheke Local Board, Community input into the Draft document for the Waiheke Island Destination Management Plan, and their Waiheke Island Sustainable Community and Tourism Strategy 2019–2024 (Project Forever Waiheke, 2019) were consulted. The study also drew on the unpublished Waiheke Draft Destination Management Plan (Tātaki Auckland Unlimited, 2022b) and Beardon's (2021) advocacy document, Waiheke Forever: The case for Waiheke Island to become a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve. Further insights were gained from Lee's (2025) advocacy piece, A new marine reserve for the Hauraki Gulf? My letter to PM Christopher Luxon, and the New Zealand Penguin Initiative's (2024) proposal for the Hākaimango-Matiatia (Northwest Waiheke) Marine Reserve. This triangulation of diverse data sources enhanced the depth and reliability of the analysis, ensuring a well-rounded understanding of the governance and sustainability challenges facing Waiheke Island.

4.3 Data analysis

Following the data collection phase, the recorded interviews were transcribed, and a thematic analysis method used to examine the data (Rabiee, 2004). The analysis identified recurrent themes, patterns, and connections within the data, drawing out key insights related to the governing systems, procedures, and outcomes on the island (Braun and Clarke, 2012). It is important to note the inductive nature of this analysis; themes were derived from the data rather than predetermined by existing theories or frameworks (Wang and Ran, 2021). Thematic analysis is a flexible and iterative process that allows researchers to adapt their approach as new insights emerge from the data (Terry et al., 2017). It requires careful attention to detail, critical thinking, and a willingness to engage deeply with qualitative material (Braun and Clarke, 2012). Thematic analysis, as a rigorous and methodical approach, helped determine important insights and classify qualitative data into relevant groups (Wang and Ran, 2021). The study employed a structured approach to thematic coding, ensuring transparency and reliability in theme identification. To ensure coding reliability, the study employed multiple coders to review a subset of transcripts and compare coding outcomes (Rabiee, 2004). A reflexive journal was maintained to document researcher biases and assumptions (Braun and Clarke, 2012). This practice helped mitigate subjectivity by encouraging continuous reflection on how the researcher's positionality might influence data interpretation.

The six steps of thematic analysis suggested by Clarke and Braun (2017) were used: data familiarization; coding; theme generation; evaluation; identification and labeling of themes; and reporting of the findings. The interview data was transcribed and analyzed using NVivo, a programme designed for qualitative data analysis. After the transcript coding, axial coding was used to organize the codes into broader groups and themes (Maguire and Delahunt, 2017); this involved putting code into groups and classifying them according to commonalities. Relevant codes were synthesized and combined to create themes (Braun and Clarke, 2012). For example, initial codes such as “collaborative efforts in governance”, “stakeholder relations and trust building” and “the role of leadership in collaboration” were merged into the theme “stakeholder collaboration”.

The study followed a systematic process for identifying and refining themes. The theme is a pattern of meaning that encapsulates a particular feature of the data (Terry et al., 2017). Initial codes were generated inductively from the interview transcripts, focusing on key phrases, concepts, and patterns that emerged from the data (Braun and Clarke, 2012). These codes were then organized into broader categories, which were further refined into overarching themes (Braun and Clarke, 2012). For example, codes such as “marine conservation,” “conservation challenges,” were grouped under the theme “nature conservation efforts.” This iterative process ensured that themes were grounded in the data and aligned with the study's objectives (Wang and Ran, 2021). An appendix with sample coding excerpts has been included (Appendix 2), illustrating how raw data was translated into codes and themes. This allows readers to assess the validity of the thematic structure and enhances transparency.

Based on the analysis of the interview data, conclusions were drawn about the state of governance in the tourism and conservation sectors of the island. Once the themes were identified, the next step involved critical evaluation and refining to ensure their relevance and consistency with the research objectives (Clarke and Braun, 2017). The themes that emerged provided insights into the key governance issues in the tourism and conservation sectors of the island. This entailed synthesizing the identified themes into a cohesive narrative that directly addressed the research questions and aligned with the study's theoretical framework (Maguire and Delahunt, 2017). Each theme was connected to the study's objectives, illustrating how they contributed to achieving the research objectives. Relevant interview excerpts were integrated to support the analysis and ensure participants' voices were central to the narrative. These excerpts validated the themes and enriched the study's authenticity. The themes were interpreted within the broader literature, comparing them with existing studies to identify contributions and areas of divergence (Clarke and Braun, 2017). Linking the themes to theoretical perspectives highlighted their importance in advancing the understanding of the research topic. The writing process was iterative, with revisions for clarity and alignment with the study's objectives, thereby offering a comprehensive narrative with practical implications for governance, tourism, and conservation.

5 Results

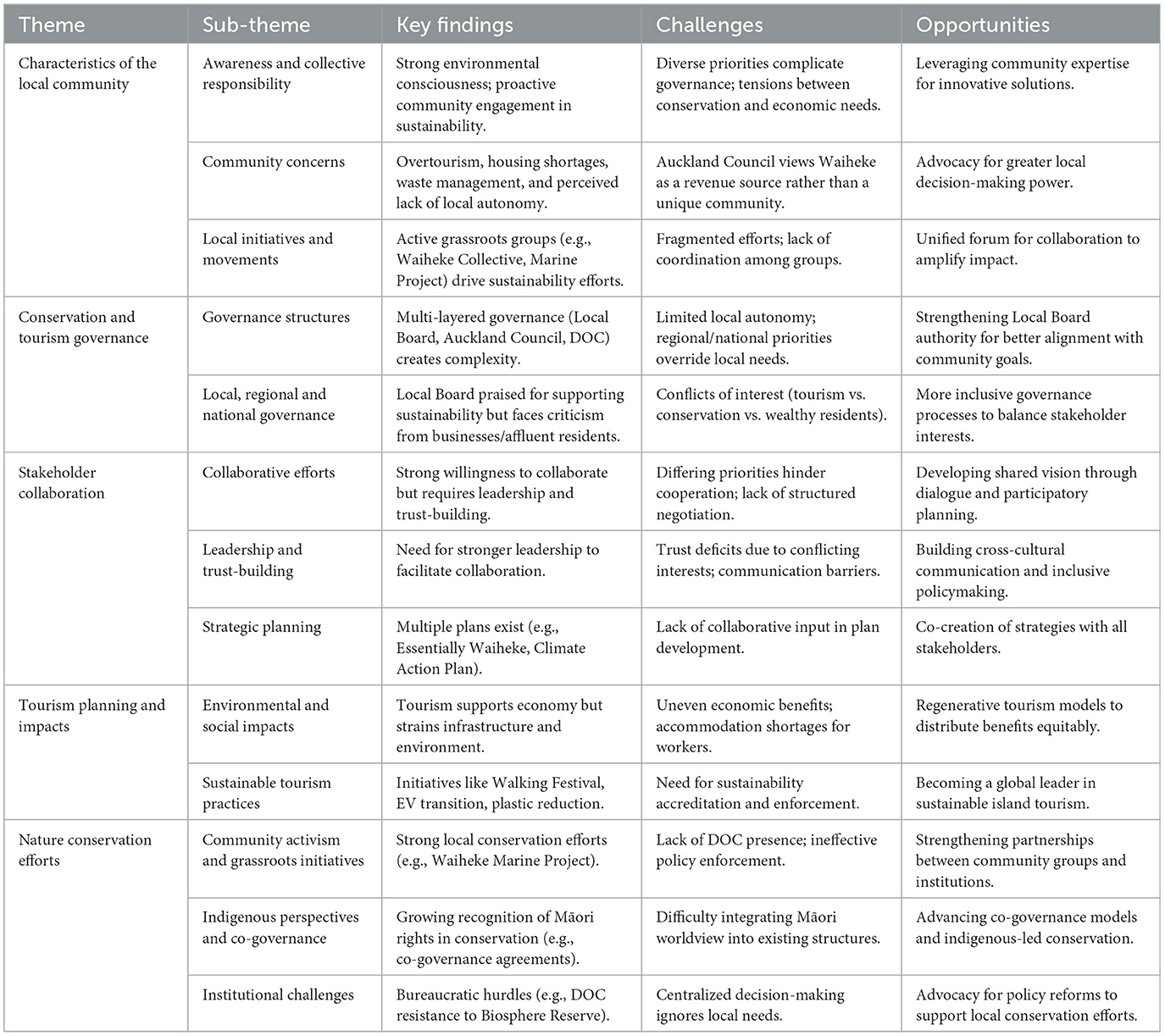

Table 1 presents the key themes, subthemes and summary of findings that emerged from the interviews, providing insight into the dynamics between tourism and conservation within the Waiheke community.

5.1 Characteristics of the local community

5.1.1 Awareness and collective responsibility

There is a strong sense of awareness and collective responsibility within the Waiheke community, particularly regarding environmental issues, tourism, and sustainable practices. Participants reported that the community is proactive in protecting the island's natural resources, with individuals and organizations actively engaging in discussions, consultations, and campaigns. A local resident encapsulated this sentiment, stating, “All the people on the island are environmental reminders.” This collective responsibility is further emphasized by a conservation and sustainability activist, who noted, “You'll find the majority of Waiheke people will be totally supportive of the [proposed marine] reserve.” Similarly, a local government representative affirmed the community's commitment, saying, “We sit as a community, deeply committed to the health of our environment and our economy.” The island's residents, many of whom are highly educated and environmentally conscious, bring diverse perspectives and skills to governance and sustainability efforts. A governance expert highlighted this, stating, “There are also a lot of overseas people... bringing in a lot of overseas thinking and ideas... highly educated, skilled people who are putting back into the community.” This diversity enriches the community's capacity for innovation but also introduces varying priorities that can complicate governance. As noted in the researcher's field observations: “During interviews, discussions often reflected the diverse backgrounds of residents, some emphasizing conservation at all costs, while others highlighted the need for economic sustainability, especially tourism. While this diversity promotes robust debate, it also presents challenges in reaching consensus on governance priorities.” (Researcher field notes).

5.1.2 Community concerns

Despite the strong sense of collective responsibility, the interviews highlighted several concerns with overtourism, urban development, housing shortages, waste management, and pressure on natural resources as key issues. A tourism sector representative noted, “There is also the issue of developments and the real estate issue... the growth and development of the island and the impact of this on the environment.” A recurring theme was the perception that Auckland Council views Waiheke primarily as a ‘resource' and ‘revenue generator' rather than considering its unique island characteristics and community needs. This sentiment underscores a desire for greater local autonomy and recognition of the island's distinct identity. Insights from the fieldwork confirms that: “Participants expressed frustration with the lack of local autonomy, emphasizing the need for Waiheke to have greater control over its governance. There was a strong consensus on the importance of balancing economic development with environmental conservation, reflecting the community's commitment to sustainability.” (Researcher field notes). However, Waiheke's strong community activism provides a counterbalance, offering a potential model for other islands seeking to empower local voices in governance.

5.1.3 Local initiatives and movements

The interviews highlighted the role of various local advocacy groups and community organizations in addressing environmental challenges and promoting sustainability policies. Key initiatives include the Waiheke Collective, Project Forever Waiheke, Waiheke Biosphere Reserve, Waiheke Resources Trust, Waiheke Tourism Inc., and the Waiheke Marine Project. These groups work to gain community support and influence decision-making processes. A tourism sector representative described the community's passion for sustainability, stating, “People have a high level of awareness when it comes to sustainability, and people are passionate about the island, they love it, and they want to do the right thing for it.” According to the researcher's observations: “Participants demonstrated a strong commitment to grassroots initiatives, with many actively involved in local movements.” (Researcher field notes). However, concerns were raised about the lack of coordination among these groups. A local government representative noted, “There were so many of them [groups] who wanted to do their own thing. You cannot work out exactly how this group relates to that group... you cannot imagine all these groups.” The proliferation of community groups on Waiheke reflects a high level of civic engagement, but it also underscores the need for better coordination. “Waiheke could benefit from adopting collaborative approaches such as creating a unified forum for community groups to align their efforts and amplify their impact” (Researcher field notes).

5.2 Conservation and tourism governance

5.2.1 Governance structures

Waiheke Island has a multi-layered governance framework, encompassing local, regional, and national levels. At the local level, the Waiheke Local Board plays a central role in decision-making processes related to tourism, conservation, and community development. Regional governance entities, such as Auckland Council and Auckland Unlimited, as well as national bodies like the Department of Conservation (DOC), exert strong influence over policies and initiatives that impact the island. This multi-tiered governance structure creates a dynamic interplay between local autonomy and external oversight, shaping the island's approach to conservation and tourism. Observations from community interviews highlight this complexity: “While the Local Board actively engaged with residents, there was a recurring frustration about the limitations imposed by Auckland Council. Several research participants expressed concern that local priorities, particularly around conservation, were often overridden by regional economic agendas, creating tensions between governance levels.” (Researcher field notes).

5.2.2 Local, regional and national governance

The Waiheke Local Board serves as the primary governing body responsible for addressing the island's unique challenges and opportunities. Guided by strategic documents such as the Essentially Waiheke policy, the Local Board plays a key role in shaping conservation and tourism policies. A local government representative explained, “The local board has a local board plan... and a policy document called Essentially Waiheke... it describes the enduring character of Waiheke and informs all policies.” This strategic focus has earned the Local Board praise for its support of local initiatives in conservation and sustainable tourism. A tourism sector representative noted, “Over the last 3 years, I have done many projects with the local board, and pretty much every submission that I have made to the local board, they support.” Similarly, a conservation activist highlighted the Board's openness, stating, “The current local board is a very powerful organization... very open to many groups”.

However, the Local Board's effectiveness is not without criticism. Tensions, sometimes, arise between the Board and various stakeholder groups, including tourism operators, conservationists, and affluent residents. A tourism sector representative elaborated, “Some members of the business community do not feel that the local board supports the businesses.” These conflicts often stem from differing priorities, such as balancing tourism development with conservation goals or addressing infrastructure needs while preserving the island's character. The influence of wealthy individuals on governance is another area of criticism, one that is not unique to Waiheke but is particularly pronounced due to the island's appeal to affluent residents. A local resident and community leader highlighted this issue, stating, “Wealthy landowners in that area felt that [because of the marine reserve proposal] there would be crowds and crowds of people spoiling their quality of life.” This remark underscores the socioeconomic disparities and power dynamics at play on the island, where wealthier residents can shape governance priorities to serve their own interests, potentially at the expense of the broader community's needs. Criticism of local governance also includes the lack of community consultation, centralization, and the strong influence of central government. Participants suggested that more independence from central government is necessary. A local government representative felt that, “The local board needs more autonomy... but that is harder to achieve looking at potential changes to more local board authority to make decisions.” Field notes indicate that: “Participants expressed a strong desire for greater local autonomy, with many advocating for the Local Board to have more decision-making power. There was a clear call for more inclusive governance processes that involve all stakeholders, particularly local residents and community groups.” (Researcher field notes).

The interviews also highlighted the role of national entities, such as the Department of Conservation (DOC), in shaping local policies. While these bodies provide essential resources and expertise, their involvement can sometimes undermine local initiatives. For example, the DOC's reluctance to support the proposed Waiheke Biosphere Reserve has been a point of contention, with some participants viewing it as a missed opportunity for advancing conservation goals. As recorded during the researcher's fieldwork: “There was a strong consensus on the importance of aligning regional and national priorities with local needs to achieve sustainable outcomes.” (Researcher field notes). Conflicts of interest arise among stakeholders, including tourism operators advocating for economic growth, conservationists emphasizing environmental protection, and affluent residents prioritizing their quality of life. According to the researcher's observations: “Participants highlighted the need for structured negotiation processes to address conflicts of interest and ensure equitable outcomes.” (Researcher field notes).

5.3 Stakeholder collaboration

5.3.1 Collaborative efforts

Collaboration emerged as a central theme in the governance discussions, with participants highlighting the importance of working together to address community concerns, develop plans, and promote sustainable development. A conservation and sustainability activist emphasized this collaborative ethos, stating, “The local board and the community all work quite closely together to try and establish an ethos and a whole system of sustainable tourism.” This sentiment was echoed by a local government representative, who noted, “The Waiheke Marine Project and the Waiheke Collective work as these two huge enterprises, which are the result of driving collaboration and not controlling it, driving it and its self-controlling.” Participants interviewed expressed a strong willingness to collaborate in the governance of Waiheke, demonstrating a high level of awareness of community needs and a shared sense of belonging to the island. Many participants are keen for Waiheke to become a model for sustainability, and there is broad agreement on the importance of maintaining the island's autonomy. Strong activism vibes were evident throughout the interviews' discussions. Despite occasional disagreements, stakeholders recognize the value of collaboration in achieving positive outcomes for the island. The involvement of diverse groups, including tourism operators, conservationists, residents, and government agencies, demonstrates a shared commitment to sustainability. However, the interviews also revealed challenges in maintaining effective collaboration, particularly in aligning differing priorities and ensuring inclusive participation.

5.3.2 Leadership and trust-building

Effective leadership was identified as a key factor in promoting collaboration among stakeholders in Waiheke. A local government representative emphasized the need for stronger leadership, stating, “I think there is a necessity for stronger leadership... it is only by collaboration within our current political structures that we would get to the point of political acceptance of protections that will enhance the value of the environment.” This view was shared by a local resident and conservation activist, who noted, “Collaboration is something harder to achieve because it requires certain predispositions, generally skills and leadership, but I do think it's possible.” The interviews revealed concerns about the lack of leadership to strengthen community input in decision-making processes and call for more inclusive approaches to policymaking, where all stakeholders, regardless of their influence or resources, have a voice in shaping the island's future. Although there are varying perspectives and interests among stakeholders, most participants agree on the importance of building trust and promoting open communication to improve collaboration. A governance and sustainability expert explained, “The trust, leadership, and resources… but it takes a long time… for building those relationships. Trust getting up as an effective functioning part is difficult because you have a cross-cultural issue of communication.” Insights from the fieldwork suggest that: “Trust-building is particularly challenging in a diverse community like Waiheke, where stakeholders often have conflicting priorities”. Bridging these divides requires creating spaces for dialogue and ensuring that all voices are heard.

5.3.3 Strategic planning

Strategic planning emerged as a critical tool for aligning stakeholder interests and guiding sustainable development on the island. Participants referred to several plans that provide a vision for the island, including the Local Board Plan, the Essentially Waiheke document, the Waiheke Local Climate Action Plan: Carbon Inventory, the Waiheke Island Transport Design Guide, and the Waiheke Draft Destination Management Plan. These plans aim to manage tourism growth, conserve natural resources, and improve community wellbeing of Waiheke. However, concerns were raised about the lack of collaborative input in the development of these plans. A tourism sector representative illustrated this issue, stating, “Because if the plan comes out [from the local board] and then it just says you will do this and this, how do they get the community's support? That's gonna be very difficult.” This highlights the need for more inclusive planning processes that engage all stakeholders from the outset. While some participants felt that a clear vision for the island was already in place, others argued that more work is needed to align stakeholder interests around a shared vision. A conservation activist noted, “The initial document [Essentially Waiheke] was kind of a common vision of the island to how it wanted to grow and what it wanted to be.” However, achieving this vision requires ongoing collaboration and a commitment to inclusive decision-making.

Stakeholder collaboration is a cornerstone of governance on Waiheke Island. However, challenges persist in aligning differing priorities and ensuring transparency. Effective leadership and trust-building are essential for collaboration, but the lack of community input in decision-making processes remains a concern. Strategic planning efforts, such as the Waiheke Draft Destination Management Plan, aim to balance tourism growth with conservation and community wellbeing. Yet, the development of these plans often lacks collaborative input, leading to frustration among stakeholders.

5.4 Tourism planning and impacts

5.4.1 Environmental and social impacts of tourism

Tourism brings both positive and negative impacts to Waiheke Island. On the negative side, participants expressed concerns about uneven promotion of attractions, accommodation shortages, strain on local infrastructure, and environmental degradation. A local resident and former government representative explained, “There is an uneven promotion of things... it's not even in terms of the way the money comes into the local economy.” This uneven distribution of economic benefits underscores the need for more equitable tourism planning. The influx of tourists has exacerbated accommodation shortages, particularly for essential workers, leading to issues of affordability and availability. Environmental concerns were also prominent, with participants citing unsustainable fishing practices and reliance on petrol vehicles as contributing factors to ecological degradation. Several interviewees indicated that tourism also brings several positive impacts to Waiheke Island. Economic benefits are evident, and tourism is a key contributor to the local economy by supporting businesses, suppliers, and employment opportunities. As evidenced by the researcher's field observations: “Participants emphasized the importance of tourism for the island's livelihood but also stressed the need to mitigate its negative impacts and adopt more sustainably practices especially regenerative tourism principles” (Researcher field notes).

5.4.2 Sustainable tourism practices

Stakeholders on Waiheke Island are actively engaged in initiatives aimed at promoting responsible, sustainable, and regenerative tourism. Initiatives such as the Waiheke Walking Festival, sustainability accreditation for tourism operators, transitioning to electric vehicles, and reducing single-use plastics exemplify the island's commitment to sustainability. One notable initiative is Project Forever Waiheke, which focuses on developing evidence-based approaches to sustainable tourism. A local government representative described the project, stating, “We have a group, Project Forever Waiheke... they've had an agenda... developing an evidence-based approach to sustainable or regenerative tourism.” A tourism sector representative noted, “What I would like to see for Waiheke is some sustainability accreditation for tourism operators... I would love us to be one of the top sustainable tourism islands in the world.” These efforts reflect a growing recognition of the need to align tourism practices with environmental and community wellbeing.

5.5 Tourism, development, and conservation on Waiheke Island

The interviews revealed a complex and often contentious relationship between tourism, development, and conservation on Waiheke Island. The island's natural beauty and biodiversity attract a significant influx of tourists, which, while economically beneficial, places considerable pressure on its fragile ecosystems. This dynamic creates both opportunities and challenges for sustainable development and responsible tourism practices. A recurring theme in the interviews was the need for tourism planning that balances economic benefits with environmental conservation and community wellbeing. A local government representative emphasized, “We must strike a balance between tourism development and residents' needs.” Similarly, a conservation and sustainability activist noted, “The local board and the community are all working quite closely together to establish an ethos and a whole system of sustainable tourism.” This collaborative effort reflects a shared recognition of the need to harmonize economic growth with environmental preservation. However, the tension between these priorities remains pronounced. A tourism sector representative acknowledged, “We are struggling with the complications of balancing economic development with environmental conservation, community wellbeing, and sustainable tourism practices.” Tourism drives Waiheke's economy but also brings challenges, environmental degradation, infrastructure strain, and uneven economic distribution. Researcher field notes reinforced this, stating: “Efforts to promote regenerative tourism and community stewardship are essential for balancing economic development with conservation”.

Participants also stressed the importance of diversifying the island's economy beyond tourism to ensure long-term resilience. A nonprofit representative argued, “A model of a sustainable economy must be able to sustain its communities,” while a government official highlighted the need for “smart economic planning ... because over-relying on tourism is not sustainable.” The proposed development of a destination management plan emerged as a potential framework for addressing these interconnected challenges, offering a strategy to manage tourism growth while supporting environmental and community priorities. Ultimately, the findings underscore the delicate equilibrium Waiheke must navigate, leveraging tourism's economic benefits while safeguarding its natural assets and community wellbeing through collaborative governance and forward-looking planning.

5.6 Nature conservation efforts

5.6.1 Community activism and grassroots initiatives

The research underscored the importance of marine protection and biodiversity conservation on Waiheke Island, with participants highlighting the island's rich ecosystems. However, concerns were raised about the negative impacts of tourism and development, ineffective conservation policies, and the lack of proper law enforcement. A nonprofit organization representative expressed frustration, stating, “It's also incredibly bad governance and policy... there's no DOC [Department of Conservation] presence on the island, this is needed.” This absence of institutional support has left a gap in conservation efforts, placing greater responsibility on local community groups and nonprofits. Insights from the fieldwork suggest that: “Grassroots initiatives play a central role in conservation efforts on Waiheke Island, with groups such as the Waiheke Resources Trust, Project Forever Waiheke, Waiheke Collective, and Waiheke Marine Project leading the charge.” (Researcher field notes). These groups are instrumental in formulating and implementing conservation policies and programs. A conservation and sustainability activist described one such initiative, stating, “A group wanted to establish a marine reserve on the northern side... because the scientific response to marine protection in New Zealand... we need 30% of the Hauraki Gulf to be a marine reserve.” This reflects a strong community commitment to marine conservation. The formation of the Waiheke Collective, which brings together diverse conservation and ecological groups, demonstrates the power of collective action. However, participants noted the need for greater coordination and a shared vision among these groups. A local government representative explained, “There is a lot of community activism... but we need to bring these groups together into a more strategic focus so they can achieve much bigger goals”.

5.6.2 Indigenous perspectives and co-governance

The integration of indigenous Māori perspectives and co-governance models into New Zealand's conservation policies is a critical and evolving issue. As highlighted in the interviews, the recognition of Māori rights and knowledge systems (mātauranga Māori) is increasingly shaping environmental governance. A governance and sustainability expert explained, “There has been a settlement over the Hauraki Gulf islands... there have been Treaty agreements for essentially co-governance, for development and management plans... there is the need to consider Māori economic interests and customary rights.” The settlement over the Hauraki Gulf islands and Treaty-based co-governance agreements underscore the importance of honoring Māori economic interests and customary rights. These developments reflect a broader shift toward acknowledging the value of indigenous knowledge in conservation efforts, as seen in initiatives like the proposed UNESCO Biosphere Reserve. However, challenges persist in reconciling Māori worldviews with existing governance frameworks, as noted by a tourism sector representative: “Māori have a different worldview, and it's kind of very difficult if you work in a structure that does not reflect that.” This highlights the need for ongoing dialogue and structural reforms to ensure that co-governance models are both equitable and effective.

5.6.3 Institutional challenges and limitations

Despite the strong community-driven conservation efforts, the interviews revealed some institutional challenges that hinder progress. Bureaucratic hurdles and resistance from government agencies, such as the Department of Conservation's reluctance to support the biosphere reserve designation, exemplify the complexities of navigating institutional frameworks. The centralized nature of decision-making within Auckland Council also poses challenges for grassroots initiatives. Several participants noted that the council's top-down approach often overlooks local needs and priorities. A conservation activist commented, “The present board just seems to be totally reliant on an agenda sent out by Auckland Council... they have lost the ability to take on big issues”.

The research findings suggest that Waiheke Island's governance system is characterized by a complex interplay of local, regional, and national influences, with both strengths and challenges. The island's strong community engagement and commitment to sustainability provide a solid foundation for addressing these challenges. By improving collaboration, and promoting inclusive governance, Waiheke can achieve a more balanced and sustainable future.

6 Discussion

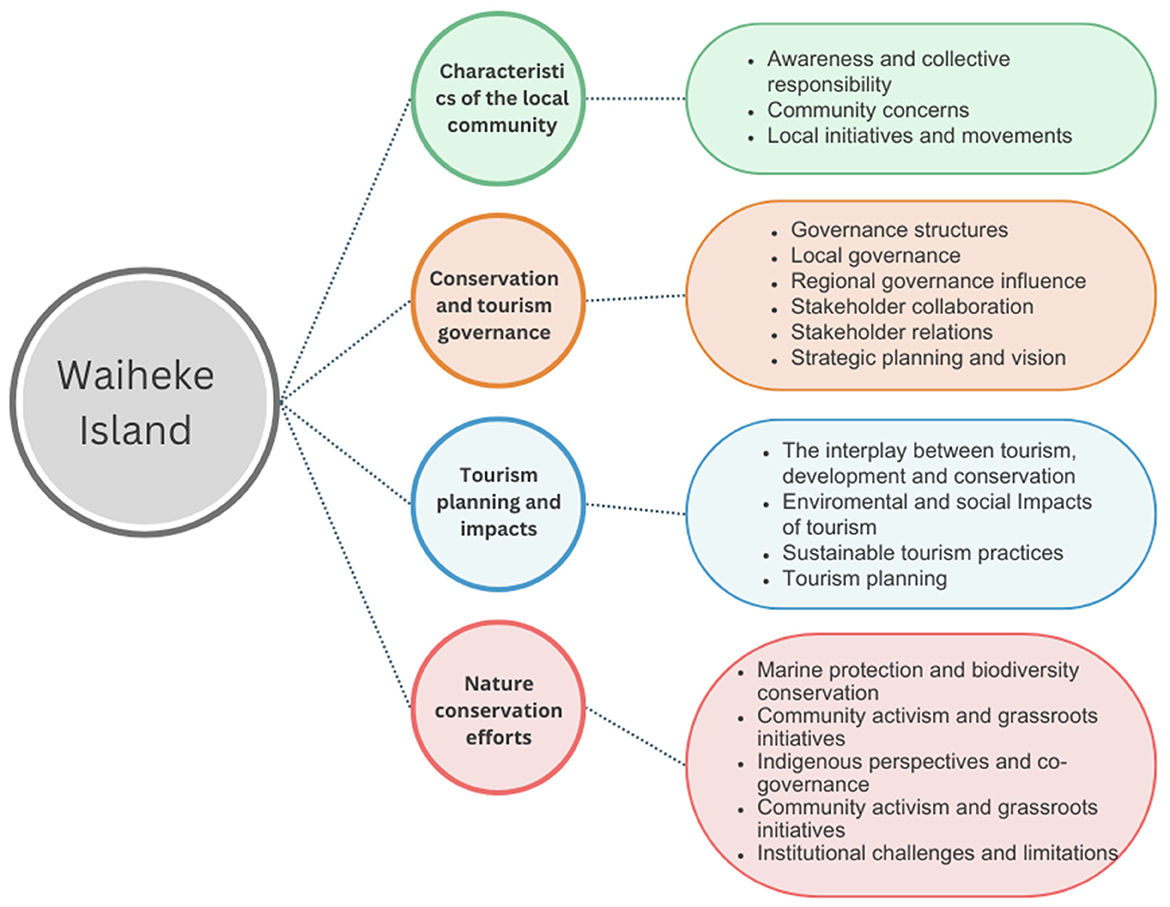

This article examined the dynamics between conservation, tourism, and the local community on Waiheke Island from a governance perspective. Figure 2 presents a conceptual framework derived from the study results. This framework visually synthesizes the key findings from the study, linking them to recommendations for improved governance and stakeholder engagement on Waiheke Island.

6.1 Environmental and socioeconomic context

The special character of Waiheke Island, described as “a special connection to the land, environmentally aware, relaxed, opinionated, independent, artistic, unconventional, resourceful, and with a strong sense of belonging,” was formally established in Essentially Waiheke: A Village and Rural Communities Strategy (Auckland City Council, 2000). This distinctive identity, rooted in the island's natural beauty and community values, has made Waiheke a hub for tourism, art, and alternative lifestyles, attracting a large number of New Zealanders and international visitors. The study findings confirmed this special character and demonstrated a strong sense of collective responsibility and awareness among the community, particularly regarding sustainable development, responsible tourism, and environmental protection. Peart and Woodhouse (2020) mirrored these findings, noting that long-term Waiheke residents are acutely aware of the island's environmental vulnerability and the importance of giving back to the community. Bunce (2008) maintained that the cornerstones of sustainable development and good governance in small islands are community awareness, commitment, and empowerment. However, Waiheke's reputation as a premier travel destination has intensified the need for robust environmental protection measures. The findings of this study revealed an effective role for NGOs and environmental groups in supporting and promoting biodiversity conservation. Yet, respondents indicated a lack of government support for the local community's effort.

The study identified urban development, overtourism, housing affordability, transportation challenges, traffic congestion, and pressure on the natural environment as the primary concerns of Waiheke residents. Many of these issues are directly linked to the social impacts of tourism on the island. Consistent with this study findings, earlier research has indicated that development pressures pose the greatest obstacles to Waiheke's social life, economy, and identity (Baragwanath and Nicolas, 2014). Peart and Woodhouse (2020) further emphasized that overtourism and population growth are the primary drivers of environmental stress on Waiheke. This study also revealed how special interest groups, particularly wealthy locals, business owners and landowners, exert considerable influence on Waiheke Island's policymaking. This influence often conflicts with the broader community's priorities, which lean toward sustainability and conservation over unsustainable tourism and development. These findings align with Scheyvens and Momsen (2020) research, which highlighted the growing wealth disparity and the disproportionate influence of elites on small island tourism and development policies as critical issues requiring greater attention.

The complex interplay between tourism, development, and conservation was evident in this study. While most of the respondents acknowledged that tourism poses risks to the environment, social fabric, housing, public services, and infrastructure, they also value its positive social impacts, such as job creation and support for small businesses. These results align with previous studies that confirmed the dual impacts of tourism on local communities (e.g., Mason, 2020; Saarinen, 2019). The majority of participants expressed a strong appreciation for sustainable and regenerative tourism practices, advocating for an “environmental ethos” and a “whole system” approach to tourism on the island. Teruel (2018) describes regenerative tourism as a dynamic concept that embeds sustainability within living systems advancing deep connections between visitors, local communities, and the natural environment. Bellato et al. (2023) further argue that regenerative tourism should integrate indigenous perspectives, knowledge systems, and traditions, a principle that resonates with Waiheke's unique cultural and environmental context.

Waiheke boasts a highly active and involved community, with numerous commendable grassroot efforts dedicated to safeguarding the island's unique identity and advancing environmental stewardship. Examples of these initiatives include Project Forever Waiheke, Waiheke Resources Trust, The Waiheke Collective, and Waiheke Marine Project. The study also highlights the critical role of marine conservation in Waiheke's sustainability efforts. Lee (2025) underscores the ecological decline of the Hauraki Gulf, driven by overfishing and inadequate marine protection policies. The proposed Hākaimango-Matiatia Marine Reserve, championed by the Friends of the Hauraki Gulf, represents a community-driven initiative to address these challenges. With overwhelming public support (93% of submissions in favor), this marine reserve would be the largest in the Hauraki Gulf, doubling the area of fully protected marine environment. This initiative align with the community's vision for regenerative tourism and environmental stewardship, as highlighted by Teruel (2018) and Bellato et al. (2023). These grassroot efforts play an active role in addressing social and environmental issues and promoting sustainable practices. Nicholas et al. (2009) similarly found that local community and organizations positively contribute to the quality of life by supporting nature conservation and tourism development. The Waiheke community benefited from the presence of educated citizens, artists, thinkers, and activists, many of whom bring “overseas thinking” and innovative sustainability ideas to the island. For example, the proposal for a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve reflects the community's global perspective and commitment to long-term sustainability. Beardon (2021), a champion of this initiative, highlights that UNESCO Biosphere Reserves are places set on a path of sustainable development, balancing environmental conservation with economic and social development. Such a designation could help Waiheke develop a single vision for its future, attract funding for projects, and create a sustainability “brand” that supports local businesses and tourism. However, small islands like Waiheke require tailored approaches to integrate sustainability into their political and planning frameworks, as noted by van der Velde et al. (2007). A prime example from this study is the Waiheke Collective, a local-driven platform established to address the lack of coordination among community groups. By acting as an umbrella organization that gathers local initiatives, the Waiheke Collective coordinates local efforts and addresses specific community concerns, serving as a replicable model for other small islands facing similar challenges.

One of the key discussion topics was the development of a destination management plan (DMP) for Waiheke. Participants acknowledged the plan's importance in strengthening local governance but expressed concerns that it lacked proper consultation and engagement with relevant stakeholders. They also noted that special interest groups had influenced the plan's creation. These findings provide more evidence to support the notion that community ownership and participation in tourism and development plans are crucial (Madzivhandila and Maloka, 2014). Destination management, according to the Central Otago District Council (2007), is essentially cross-agency cooperation and communities working together to capitalize on and protect what makes the region special. Effective working relationships must be established and maintained by central and local governments, communities, the private sector, and other pertinent players in order to ensure a sustainable future (Keogh, 1990). Destination management requires a strategy that involves the entire community (Central Otago District Council, 2007). In their submission to Waiheke Local Board, Project Forever Waiheke (2023) raised the community's concerns about the DMP development process, particularly the lack of genuine community consultation. The submission highlighted that the initial workshops were held at inaccessible times, the survey was poorly promoted and executed, and the final draft was written by consultants with no first-hand experience of Waiheke. These issues mirror the experience of New Zealand's Great Barrier Island, where the DMP was described as “embarrassing” and not reflective of community input. These examples underscore the importance of inclusive, transparent, and locally-informed planning processes to ensure that DMPs genuinely reflect community values and priorities.

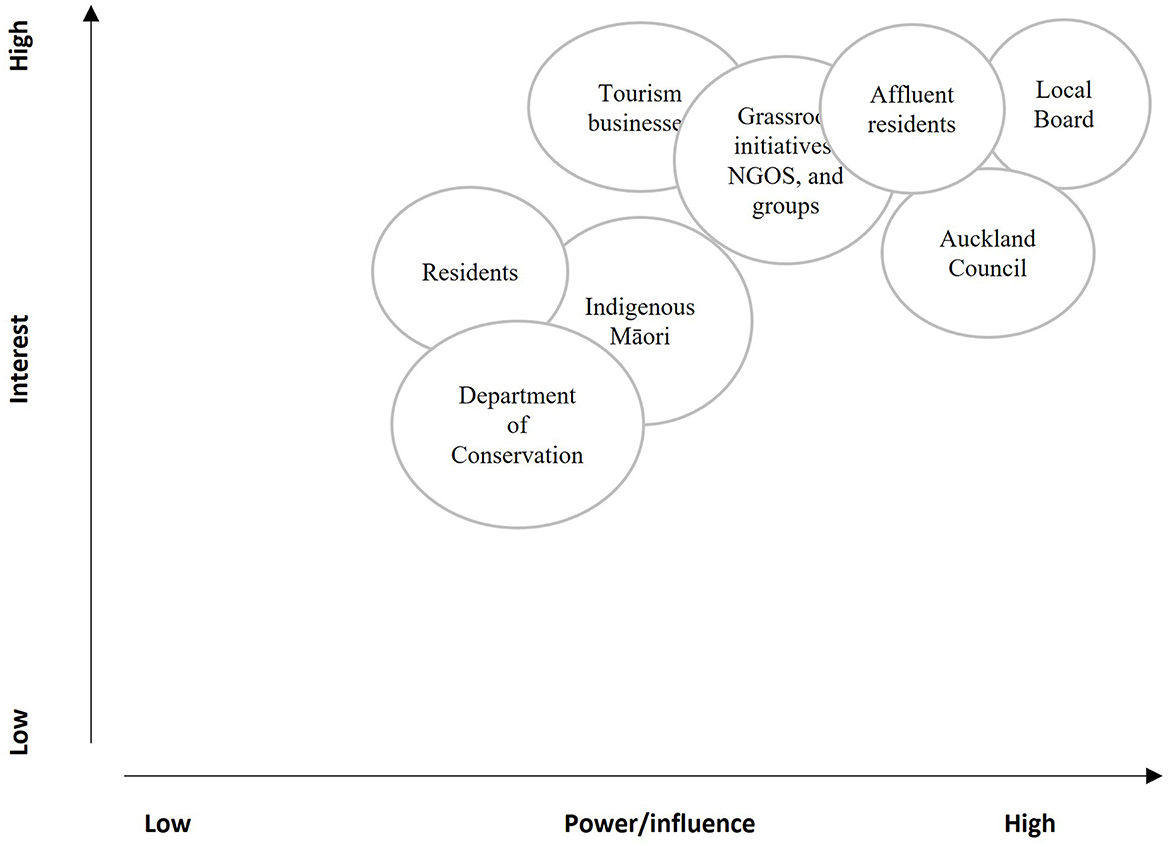

6.2 Governance systems dynamics

The collective governance system on Waiheke Island operates within a dynamic interplay of social systems, cultural values, lifestyles, and community preferences. While the governance framework itself is stable, the inclusion of diverse community actors introduces variability in engagement and influence. The study highlights the differing levels of interest and influence among formal and informal actors as illustrated in Figure 3. For example, tourism businesses exhibit high interest but only moderate influence, reflecting their economic stakes yet limited decision-making authority. Grassroots initiatives (Activists, NGOs and community groups) fall into the high-interest, medium-to-high influence quadrant, demonstrating their active role in driving outcomes through cultural authority and local mobilization. The Waiheke Local Board holds the highest influence and interest as the primary mediating body, whereas regional actors like the Auckland Council wield high influence despite having less localized engagement, illustrating the tension between centralized governance and community-driven priorities. The matrix reveals a governance landscape where formal power often rests with external agencies, while the most invested stakeholders (tourism sector, Māori and grassroots groups) must actively negotiate, contest, or collaborate to advance their interests. The Waiheke Local Board is widely regarded as the primary mediating body in balancing tourism, development, and conservation. Most respondents expressed positive views of the board's efforts, aligning with findings by Hovik and Hongslo (2017), who noted that local boards often mediate between national and local priorities while addressing development and conservation goals. However, this mediation frequently involves conflicts of interest, particularly between tourism developers advocating for economic growth and conservation groups prioritizing ecological protection. Negotiations are typically led by the Local Board, but respondents noted that compromises often favor short-term economic gains due to pressure from regional authorities and private investors.

The island's vision, articulated in strategic documents such as Essentially Waiheke (Auckland City Council, 2000, 2016), serves as a foundational policy framework that guides planning and decision-making. This document reflects the community's aspirations and enduring character, reinforcing the importance of policy frameworks that align with local values. These findings are consistent with Torkington et al. (2020), who emphasized that such policy documents communicate community and government visions, projecting them into the future. Respondents highlighted concerns about limited community involvement in policy planning and the overbearing influence of regional and national authorities, particularly Auckland Council. Many participants advocated for greater local autonomy, arguing that the island's unique identity and strong sense of community warrant more decision-making authority at the local level. This sentiment aligns with Logie (2016), who noted Waiheke's tradition of political independence despite its affiliation with Auckland Council. The tension between local autonomy and external oversight is a recurring theme in small island governance, as highlighted by Petzold and Ratter (2019) and Baldacchino (2020). While autonomy enables small islands to protect their environments and preserve their cultures, achieving it remains challenging due to external pressures and constraints.

Stakeholder collaboration emerged as a critical factor in Waiheke's governance. The study revealed a culture of cooperation among tourism operators, conservation groups, residents, and government agencies, all working toward sustainable development. The involvement of scientists, educators, activists, and community leaders further underscored the importance of multi-stakeholder engagement. These findings align with studies by Jordan et al. (2013) and Nunkoo (2017), which link community activism to effective governance. Respondents emphasized that shared vision, leadership, trust, transparency, and communication are essential for strengthening stakeholder relations and improving collaboration. This echoes Pomeranz et al. (2013), who found that trust and dialogue enhance collaboration in managing nature-based recreation in protected areas.

Ansell and Gash's (2008) Collaborative Governance Framework provides valuable insights into the dynamics of stakeholder collaboration on Waiheke. The framework identifies four key variables: starting conditions, institutional design, leadership, and the collaborative process. On Waiheke, the starting conditions include a history of community activism and a strong sense of local identity, which foster incentives for participation. However, power imbalances between local and regional authorities, as well as socioeconomic disparities among residents, pose challenges to trust-building. The institutional design, exemplified by documents like Essentially Waiheke, provides a foundation for participatory inclusiveness and process transparency. Yet, the lack of clear ground rules and facilitative leadership often hinders effective collaboration. Respondents called for stronger leadership to empower stakeholders and bridge divides, a critical factor highlighted by Ansell and Gash as essential for driving the collaborative process. The collaborative process itself, as described by Ansell and Gash, relies on trust-building, commitment to the process, and face-to-face dialogue. On Waiheke, this is evident in grassroots initiatives like Project Forever Waiheke and the Waiheke Marine Project, which promote mutual recognition of interdependence and shared ownership of the process. However, the absence of sustained governmental support, such as a permanent Department of Conservation (DOC) presence, weakens these efforts. Intermediate outcomes, such as small wins and joint fact-finding, are crucial for building momentum and trust. For example, the Waiheke Collective demonstrates how strategic coordination among community groups can lead to tangible progress in conservation and tourism governance. Yet, gaps in leadership and strategic island-wide cohesion remain, highlighting the need for a more structured and inclusive collaborative process.

Ansell and Gash's (2008) Collaborative Governance Framework highlights how power imbalances distort negotiations. On Waiheke Island, affluent residents, tourism operators, and developers, supported by local and regional policymakers, appear to wield disproportionate influence in decision-making processes, while conservationists and Māori groups face challenges in achieving meaningful concessions.

An important aspect of Waiheke's governance is the integration of Māori perspectives and co-governance models. Respondents highlighted the importance of incorporating Māori values and traditional ecological knowledge (mātauranga Māori) into conservation and tourism policies. This aligns with studies by Robin et al. (2022), Shultis and Heffner (2016), and Tran et al. (2020), which emphasisze that indigenous participation is essential for equitable and effective conservation. Co-governance arrangements should prioritize respect for indigenous knowledge, collaborative decision-making, cultural preservation, and long-term partnerships based on trust and shared goals. The evolution of Essentially Waiheke reflects this shift: while earlier versions did not consult tangata whenua (Māori with ancestral ties to the land), the 2016 review actively incorporated Māori values and perspectives. This change acknowledges the role of Māori as kaitiaki (guardians) and their holistic worldview (tikanga Māori), which integrates spiritual, cultural, environmental, and economic dimensions. The principle of manaakitanga (hospitality) further underscores the importance of inclusive resource management. Waiheke's rich Māori history, including sites like Whetumatarau headland at Matiatia, highlights the need for culturally informed governance that respects the island's heritage while addressing contemporary challenges. Ansell and Gash's framework (Ansell and Gash, 2008) and Freeman's Stakeholder Theory (Freeman, 1984) underscore the importance of inclusive and transparent processes in advancing meaningful collaboration. On Waiheke, the integration of Māori perspectives into governance aligns with Ansell and Gash's framework's emphasis on shared understanding and mutual gains. However, the study revealed that current governance structures inadequately reflect Māori worldviews, limiting participatory and culturally informed decision-making. Treaty-based co-governance models, as suggested by respondents, could address this gap by incorporating mātauranga Māori into policy and promoting inclusivity. This approach would not only honor Waiheke's Māori heritage but also strengthen conservation and tourism governance by aligning with the community's shared values and aspirations.

The study revealed several governance challenges. Waiheke's popularity as a tourist destination strains local infrastructure and ecosystems, creating tensions between tourism growth and environmental sustainability. While the Waiheke Local Board supports local initiatives, respondents criticized its limited autonomy and reliance on regional authorities like Auckland Council. This centralization restricts the board's ability to address local needs and align governance with the island's distinct identity (Peart and Woodhouse, 2020). Top-down approaches were seen as hindering community participation and adaptive policymaking, complicating efforts to balance regional and local priorities. To address these challenges, respondents called for enhanced collaborative governance that brings together local authorities, tourism operators, conservation groups, and other stakeholders. While examples of collaboration exist, gaps in leadership and strategic coordination remain (Project Forever Waiheke, 2023). Effective governance, according to participants, requires strong leadership to bridge divides and leverage the expertise of scientists, activists, and conservationists. Grassroots initiatives like Project Forever Waiheke, the Waiheke Resources Trust, and the Waiheke Marine Project demonstrate the community's commitment to marine protection and biodiversity. However, the absence of sustained governmental support, such as a permanent Department of Conservation (DOC) presence, weakens these efforts. Respondents also emphasized the need for better coordination among community groups to maximize their impact. The study highlights the importance of inclusive, transparent, and well-structured governance processes to achieve sustainable outcomes on Waiheke Island. By addressing power imbalances, advancing facilitative leadership, and building trust through collaborative processes, Waiheke can strengthen its governance systems and better balance tourism growth with environmental conservation and community wellbeing.

The study revealed several critical outcomes of Waiheke Island's current governance system that warrant careful examination. First and foremost, decision-making processes remain fragmented due to ongoing power struggles between local and regional actors. This fragmentation frequently delays or weakens conservation efforts, with respondents reporting that Auckland Council overrides community preferences. This dynamic creates challenges for maintaining consistent environmental protections. A second key finding concerns the inclusion of Māori values within governance structures. While mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge) is formally acknowledged in policy documents, tangata whenua (Māori stakeholders), more effort in engagement is still needed. This gap between policy and practice reduces what should be meaningful co-governance to mere tokenism, undermining both the spirit and effectiveness of community collaboration arrangements. Third, the study documented the emergence of grassroots resilience as communities respond to governance gaps. Local initiatives like Project Forever Waiheke have demonstrated remarkable adaptive capacity by stepping in to address issues that formal agencies have failed to resolve. However, these community efforts operate without adequate systemic support, limiting their long-term impact and sustainability.