- 1Department of Ecotourism and Recreation, Faculty of Forestry, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Selangor, Malaysia

- 2Peer Review College, British Academy of Management, London, United Kingdom

- 3College of Business, University of South Australia, Adelaide, SA, Australia

- 4College of Business & Law, Adelaide University, Adelaide, SA, Australia

- 5Centre for Innovation in Tourism, Taylors University, Subang Jaya, Malaysia

Introduction: Birdwatching as a subcategory of ecotourism can create recreational disturbance. This research aims to assess two main goals: firstly, the effects of the frequency of participation (FOP) of Malaysian birders as moderators on the constructs of a Predictive Bird Conservation Model (PBCM). Secondly, the Importance–Performance Matrix Analyses (IPMA) of the PBCM, the extension builds on the partial least squares (PLS) estimates of the path model relationships.

Methods: Data was collected from 421 Malaysian birdwatchers using a field survey. We extend the theory of planned behavior (TPB) and cognitive hierarchy model (CHM), which was integrated into PBCM. The model was tested using the PLS approach.

Results: The work explored the moderating role of FOP in all defined relationships in PBCM. Six hypotheses are proposed and tested.

Discussion: This research reflects the importance of FOP in moderating the relationship between value orientation and intention toward disturbance behavior among Malaysian birdwatchers and further shows the moderator role of FOP between Attitude and intention. FOP does not moderate other defined relationships in the PBCM. The study also enriches the birdwatching literature for decision-making sustainably. The findings provide useful managerial insights for policymakers and practitioners regarding bird-watching behavior.

1 Introduction

Ecotourism is a subclass of sustainable tourism (Cabral and Dhar, 2020). Wildlife watching, including birding, belongs to the class of non-consumptive wildlife tourism (Kim et al., 2010; Tuneu et al., 2018; Saha and Chakraborty, 2024). Avitourism is a specialized form of tourism that involves the observation, appreciation, and conservation of birds in their natural habitats (Steven et al., 2020). It contains identifying different species of birds and their behaviors, as well as understanding their habitats and ecological roles (Saha and Chakraborty, 2024). Birdwatching, as the largest part of ecotourism activity (Kim et al., 2010; Tan et al., 2023), can have numerous negative impacts on birds (Santos et al., 2019). There is a potential for significant impacts on both humans and wildlife as a result of these interactive experiences (Hughes and Carlsen, 2008). An increase in visitor interaction with wildlife may cause an adverse response in both animals and their habitats, including various levels of disturbance (Tuneu et al., 2018; Tan et al., 2023). Research on a variety of wildlife species at several study sites has shown modified animal behaviors and disturbance behaviors potentially harmful to humans and other animals, including dependency on non-natural food sources, such as artificial feeding sites (Brookhouse et al., 2013; Griffin et al., 2022).

However, the appeal of birdwatching includes an outstanding chance of establishing a connection with nature and encourages a more thoughtful appreciation for the environment (Saha and Chakraborty, 2024). Furthermore, birdwatching can contribute to conservation as many birdwatchers also participate in “citizen science projects” designed to monitor and protect bird species (Tan et al., 2023; Saha and Chakraborty, 2024). Based on the number of participants, the level of participation, and expenditures, avitourists are an important part of wildlife watchers (Hvenegaard, 2002).

In the current study, we assess the effect of frequency of participation (FOP) on the constructs of the Predictive Bird Conservation Model (PBCM). We developed the PBCM, a decision-making model integrated with the theory of planned behavior (TPB), the theory of normative conduct, and the cognitive hierarchy model (CHM) among Malaysian avitourists toward birds (Jafarpour and Ramkissoon, 2023, 2024). We have also shown the importance–performance matrix analysis (IPMA) of PBCM, the extension that builds on the partial least squares (PLS) estimates of the path model relationships.

In a previous study, Jafarpour and Ramkissoon (2023) developed a questionnaire and then introduced the PBMC in 2024. PBMC included six paths directly linked to intention that identified to what extent the dependent variable (intention) was explained by the independent variables: (a) value orientation (VO), (b) past behavior (PB), (c) subjective norms (SNs), (d) descriptive norms (DNs), (e) perceived behavior control (PBC), and (f) attitude (Att). Four paths are linked indirectly to intention (IN); these links are between VO–Att and PB–PBC. These paths include mediators (Att and PBC); attitude mediates the relationship between VO and IN (Jafarpour and Ramkissoon, 2024); PBC mediates the relationship between PB and IN (Jafarpour and Ramkissoon, 2024).

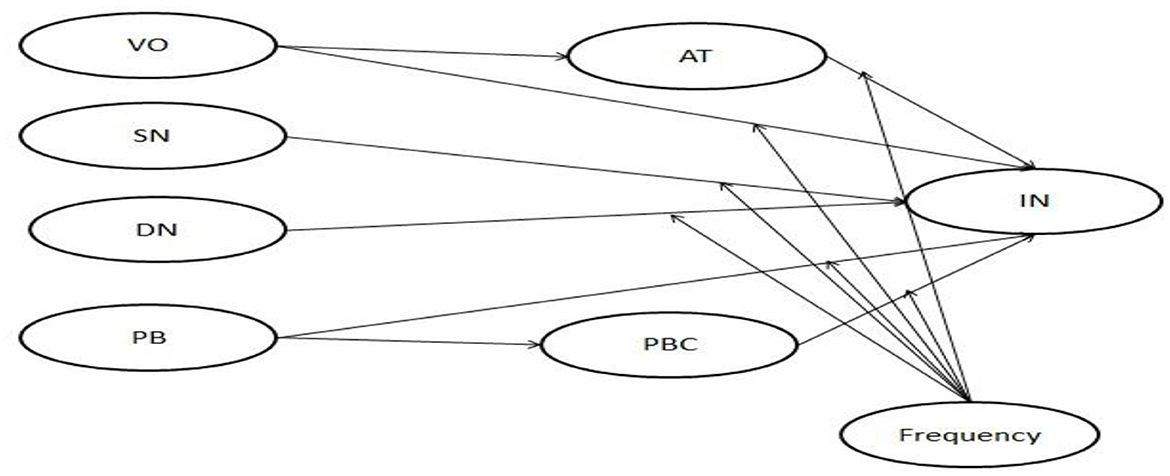

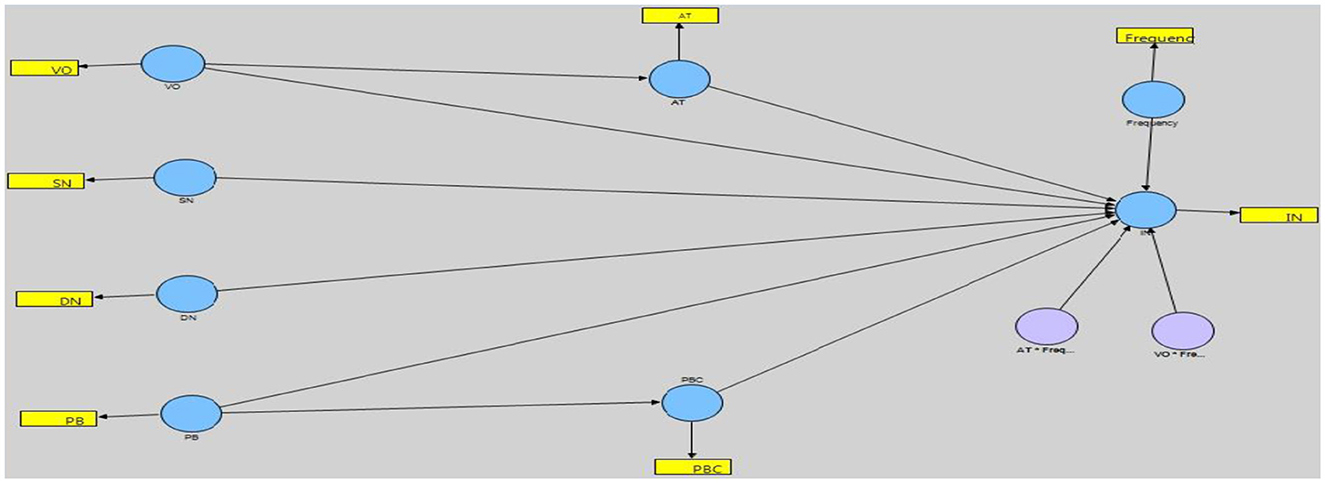

In the present research, first, we explored FOP's moderating role in all defined relationships in PBCM. Six hypotheses were proposed and tested. Our current research findings revealed evidence highlighting FOP's importance (as an index for experience) in moderating the relationship between VO and IN toward birds among Malaysian birdwatchers. It also shows FOP's moderating role between Att and IN. FOP does not moderate the other defined relationships in the PBCM. FOP has been included as an additional construct to expand PBCM; see Figure 1.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework for the predictive model of disturbance behavior on birds among respondents. VO, value orientation; SN, subjective norms; DN, descriptive norms; PB, past behavior; PBC, perceived behavioral control; AT, attitude; IN, intention; Frequency = frequency of participation in birdwatching.

The results showed that FOP positively moderated the relationship between VO and IN, as well as between Att and IN. Thus, from the six hypotheses, all were rejected except for H1, FOP moderates the relationship between VO and IN, and H5, FOP moderates the relationship between Att and IN.

FOP's moderating role in the defined relationship of our research framework has yet to be explored in the literature. To fill this gap, the current study proposes to explore FOP as a moderating variable in the relationships, including VO and IN, as well as Att and IN, in decision-making among Malaysian avitourists. Second, we ran IPMA over PBCM; we added a dimension to the analysis that considers the average values of the latent variables. The consequences are useful in the management area for decision-making by principles in sustainable wildlife tourism. The outcomes will also enrich knowledge and information provision for the sustainable management of birdwatching.

2 Literature review

In this section, we review birdwatching and the human dimension of wildlife management (HDWM), and the new model was presented.

2.1 Birdwatching

Over the past few decades, a non-consumptive form of human interaction has developed into widespread tourism activity (Dou and Day, 2020). Wildlife watching is seen as an activity that not only satisfies tourists' desire to raise the value of nature and increase economic benefits for the host community but also assists the purpose of wildlife conservation, although consensus has not been reached on the latter point yet (Hvenegaard, 2002; Dou and Day, 2020). Birdwatching is a trip away from home to observe and identify birds in their natural environment (Mokhter et al., 2022). While birdwatching is favored most among wildlife-watching, birdwatching studies are still blossoming (Weston et al., 2015; Sumanapala and Wolf, 2020; Mokhter et al., 2022). A large number of wildlife populations appropriate for tourism development are located in low- and medium-income countries (Tuneu et al., 2018). Few studies on birdwatchers have been conducted in Asia (Cheung et al., 2017). Tropical Asia has noteworthy potential for wildlife tourism (Samdin et al., 2022), especially avitourism (Marasinghe et al., 2020). Malaysia has many protected areas aimed at protecting local and endemic species by providing them a good habitat (Ng and Norazlimi, 2022). Newsome et al. (2020) warns about the possible effects on birds in the developing world due to informal guidance and money-targeting tour guides. However, the studies show that tourists and tour operators are more likely to be recorded as conservation partners when they are specialists (Hvenegaard, 2002; Tuneu et al., 2018). Previous research has shown that the higher the level of birdwatchers' specialization, the greater its impact on their attitude and their conservation behaviors Cheung et al., (2017). According to (Cheung et al. 2017), birdwatcher specialization is defined using 10 items frequently used to test birdwatchers' specialization and are divided into four groups: “experience, personal commitment, economic commitment, and achievement.” However, in our study, only the item of experience (FOP) has been addressed—not as a predictor but as a moderator.

2.2 Human dimension of wildlife management

Managing wildlife is 10% biology and 90% managing people (Manfredo et al., 2021a). HDWM is characterized by a host of behavioral science viewpoints. Although the importance of the human dimensions of wildlife is not novel, the emphasis on the science of the human dimension is novel; this assessment is in agreement with the wildlife conservation profession (Serota et al., 2023; Jacobs et al., 2018). Tourism based on human–wildlife interactions can often go wrong in the absence of strong management rules, leading to destructive influences for both animals and humans (Usui and Funck, 2018). Research, including both ecological and social dimensions, takes into account the complex nature of human–wildlife interactions and their effects; therefore, it may better monitor the sustainable development of the wildlife tourism industry (Rodger et al., 2011). Knowledge about the basic influence of ecologically responsible behavior toward birds is deficient (Cheung et al., 2017; Weston et al., 2015).

This study addresses the need for knowledge that might help change birdwatchers' behaviors. Therefore, we aimed at understanding FOP's moderator effects on the intentions of Malaysian avitourists toward monitoring their behavior to minimize negative behaviors. Such information can help protected area managers estimate the probability of ecologically irresponsible behavior at birdwatching sites and formulate operational strategies.

2.3 Theories and modeling

Scientists have requested more research that simultaneously studies the ecological and social aspects Rodger et al., 2011. In previous studies, PBMC was introduced as an extended version of TPB that was applied to wildlife management in birdwatching modeling among Malaysian avitourists toward birds (Jafarpour and Ramkissoon, 2023, 2024). The wide use of TPB justifies its use as a framework (Xu et al., 2022; Samdin et al., 2022). The PBMC showed the association between physiological factors, namely, VO, Att, PBC, PB, SNs, DNs, and IN, with conservation science in tourist behavior. Ten hypotheses were defined, tested, and discussed (Jafarpour and Ramkissoon, 2023, 2024).

In the present research, we developed TPB and CHM, which were integrated into PBCM regarding disturbance behavior on birds among Malaysian avitourists by influencing FOP as a moderator in the constructs of the PBMC.

As Figure 1 illustrates, the six paths are between FOP and the relationships between VO–IN, Att–IN, SNs–IN, DNs–IN, PB–IN, and PBC–IN.

Drawing on the preceding discussion of the literature, we propose the following:

• H1. FOP moderates the relationship between VO and IN toward disturbance behavior on birds among Malaysian birdwatchers.

• H2. FOP moderates the relationship between SNs and IN toward disturbance behavior on birds among Malaysian birdwatchers.

• H3. FOP moderates the relationship between DNs and IN toward disturbance behavior on birds among Malaysian birdwatchers.

• H4. FOP moderates the relationship between PB and IN toward disturbance behavior on birds among Malaysian birdwatchers.

• H5. FOP moderates the relationship between Att and IN toward disturbance behavior on birds among Malaysian birdwatchers.

• H6. FOP moderates the relationship between PBC and IN toward disturbance behavior on birds among Malaysian birdwatchers.

To develop a model to find the effects of FOP among Malaysian avitourists, six hypotheses were tested. Moreover, IPMA of PBCM adds an additional dimension to the analysis that considers the latent variables' average values. See the Methodology section.

IPMA, also known as a priority map analysis, importance–performance matrix, or impact–performance map, is a useful analytical method that expands the reported standard path coefficient estimate results by adding a dimension that considers the average values of the latent variable scores (Ringle and Sarstedt, 2016). The idea of IPMA is to contrast the total effects of a predictive variable that determines a target construct. To date, IPMA has been increasingly used as an analytical technique among researchers in several fields (Ringle and Sarstedt, 2016; Schloderer et al., 2014), including tourism (Carranza et al., 2018; Kucukergin and Gürlek, 2020; Fakfare and Manosuthi, 2023; Phu et al., 2019). In the tourism literature, Carranza et al. (2018) investigated the impacts of quality on satisfaction and customer loyalty in the context of fast-food restaurants by implementing IPMA. Their findings indicated that service quality is the most valued element among three quality attributes (i.e., service quality, food quality, and atmosphere), exhibited greater performance and minor importance, and generated a high yield of satisfaction and loyalty in fast-food restaurants. The IPMA can be taken into account when the research goal is to prioritize variables of a certain construct (Ringle and Sarstedt, 2016), and the technique has rarely been utilized to investigate issues in the tourism object (Carranza et al., 2018). In our research, we introduced the importance–performance matrix to compare the predictors of PBMC toward Malaysian avitourists on birds that have high importance and performance for use in management strategies.

3 Methodology

The deductive method was employed in this study, where appropriate theories are identified to develop a conceptual framework, and the hypotheses are subsequently tested empirically. A census technique was used; see the locations and dates for data collection in Appendix. A quantitative approach, a field survey, was used to collect data from respondents (N = 421). The target population was all Malaysian birdwatchers who had, at least once, experienced birdwatching. Structural equation modeling (SEM), especially SmartPLS, a software program, was used to analyse the data. Our PBCM model was based on Jafarpour and Ramkissoon's (2023) questionnaire. PBCM (Jafarpour and Ramkissoon, 2024) is modeled based on their previous study. However, in the current study, we aimed to achieve two main goals for better managing PBCM. First, the effects of FOP on the relations in PBCM were checked (Section 3.1). Then, IPMA was also done over PBCM (Section 3.2).

3.1 Continuous moderator effects

The cause-and-effect relationship in a PLS path model implies that exogenous latent variables affect endogenous latent variables without any systematic influences from other variables. In many instances, however, this assumption does not hold (Hair et al., 2021). In this study, however, a continuous moderator variable that affects the strength of one specific relationship between two latent variables is assumed (Hair et al., 2021). However, moderators may also change the direction of relationships. For example, a path coefficient may be positive for those observations with high values in the moderator variable, whereas the structural relationship is negative for observations where this is not the case (Hair et al., 2021). In both cases, this kind of heterogeneity, explained by a continuous moderator variable, occurs when the relationship between the latent variable is not constant but rather depends on the values of the moderating variable (Hair et al., 2021). In PLS-SEM, two approaches are usually employed to create the interaction term. One is the product indicator approach. The next one is the two-stage approach. When the exogenous latent variable or the moderator variable has a formative measurement model, researchers should use the two-stage approach to extend the product indicator approach to formative measures by explicitly using PLS-SEM's advantage of estimating latent variable scores (Henseler and Chin, 2010; Rigdon et al., 2010; Hair et al., 2021). The two stages are as follows (Hair et al., 2021): Stage 1: The main effects model is estimated without the interaction term to obtain the scores of the latent variables. These are saved for further analysis in the second stage. Stage 2: The latent variable scores of the exogenous latent variable and moderator variable from Stage 1 are multiplied to create a single-item measure used to measure the interaction term. All other variables are represented by the means of single items of latent variable scores from Stage 1. Henseler and Chin's (2010) simulation study on using these alternative approaches in PLS-SEM shows that when prediction represents the major or only purpose of an analysis, researchers should use the two-stage approach. Six hypotheses were developed and mentioned in the Literature Review section.

3.2 Importance-performance matrix analyses (IPMA)

A key characteristic of the PLS-SEM method is the extraction of latent variable scores. IPMA is useful in extracting the findings of the basic PLS-SEM outcomes using the latent variable scores (Fornell et al., 1996; Völckner et al., 2010). The extension builds on the PLS-SEM estimates of the path model relationships and adds dimensions to the analysis that consider the average values of the latent variables. For a specific endogenous latent variable representing a key target construct in the analysis, IPMA constructs the structural model's total effects (importance) and the average values of the latent variable scores (performance) to highlight significant areas for improving management activities (or the specific focus of the model). More specifically, the results permit the identification of determinants with relatively high importance and relatively low performance. These are major areas of improvement that can subsequently be addressed by marketing or management activities. A basic PLS-SEM analysis identifies the relative importance of constructs in the structural model by extracting estimations of the direct, indirect, and total relationships. IPMA extends these PLS-SEM results with another dimension, which includes the actual performance of each construct.

Executing an IPMA first requires identifying a target construct. To complete an IPMA of a particular target construct, the total effects and the performance values are needed. The importance of latent variables for an endogenous target construct—as analyzed using an impotence–performance matrix—emerges from these variables' total effects. In PLS-SEM, the total effects are derived from PLS path model estimation. We need to obtain the performance values of the latent variables in the PLS path model. To make the results comparable across different scales, we use a performance scale of 0–100, where 0 represents the lowest performance and 100 the highest performance. Rescaling the latent variables to obtain index values requires the following computations to be performed: Subtract the minimum possible value of the latent variable's scale (i.e., 1 for a scale of 1–7) from an estimated data point and divide this data point by the difference between the minimum and maximum data points of the latent variable's scale (i.e., 7 – 1 = 6 for a scale of 1–7):

where Yi represents the ¡th data point (e.g., i = 5 concerning the latent variable score of the fifth observation in the data set) of a specific latent variable in the PLS path model (Anderson and Fornell, 2000; Tenenhaus et al., 2005).

This procedure results in rescaled latent variable scores on a scale of 0–100. The mean value of these scores of each latent variable produces the index value of their performance (Hair et al., 2021).

4 Results

The presented results are based on the comprehensive survey of 421 Malaysian birdwatchers (respondents) conducted from July 2013 to August 2014, ~ 13 months. The majority of respondents are Indian Malaysians (40.9%), followed by Malays (25.4%), Chinese Malaysians (23.5%), and other races who are residents of Malaysia (10.2%). Regarding gender, more than two-thirds of respondents (71.4%) are male, and the remaining (28.2%) are female. As for age, the number of respondents older than 40 years is almost 1.5 times that of respondents younger than 40 years old; see Table 1.

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics for FOP in the events (see Appendix) by respondents. The birdwatchers had experienced birdwatching at least once.

4.1 The effect of the FOP over PBCM

Initially, there were six hypotheses (H1, H2, H3, H4, H5, and H6) developed to test whether the FOP in birdwatching moderated the relationship between six predictor variables and intention toward disturbance behavior on birds. For this purpose, it was explored whether the frequency moderator exerted a significant effect on the direct relationship between all six exogenous variables (value orientation, attitude, subjective norms, descriptive norms, past behavior and perceived behavioral control) and intention. A two-step approach was used, which was discussed in the methodology section. The bootstrapping procedure was run with 421 cases and 500 samples. There is a need to refer to the moderation interaction terms to interpret the moderation results. Interaction terms should be referred to when interpreting birdwatching events. Consider the following results and interaction results. A moderation effect is significant when a relative interaction term is statistically significant. Among the six interaction terms, only two were statistically significant: the interaction between Att and FOP on IN (t = 1.767, p = 0.078; p < 0.1), which is marginally significant (p < 0.1), and the interaction between VO and FOP on IN (t = 2.157, p = 0.03), which is significant at the 5% level (p < 0.05).

The interaction term for the AT–IN relationship was negative, indicating that FOP weakened the positive relationship between Att and IN. This moderation reduced the original effect from 0.220 to 0.091 (i.e., a decrease of 0.129). This implies that the more frequently birdwatchers participate in birdwatching events, the less influence their attitudes have on their behavioral intentions.

In contrast, the interaction term between VO and IN was positive, increasing the strength of the relationship. The effect size increased from 0.619 to 0.778 (i.e., 0.619 + 0.159). This suggests that frequent participation strengthens the effect of VO on IN toward disturbance behaviors.

To sum up, the results demonstrated that FOP positively moderated the relationship between value orientation and intention and negatively moderated the relationship between attitude and intention. Among the six hypotheses, only H1 and H5 were supported by the interaction effects:

- H1: FOP moderates the relationship between VO and IN (p = 0.03)—accepted.

- H5: FOP moderates the relationship between Att and IN (p = 0.078)—marginally accepted.

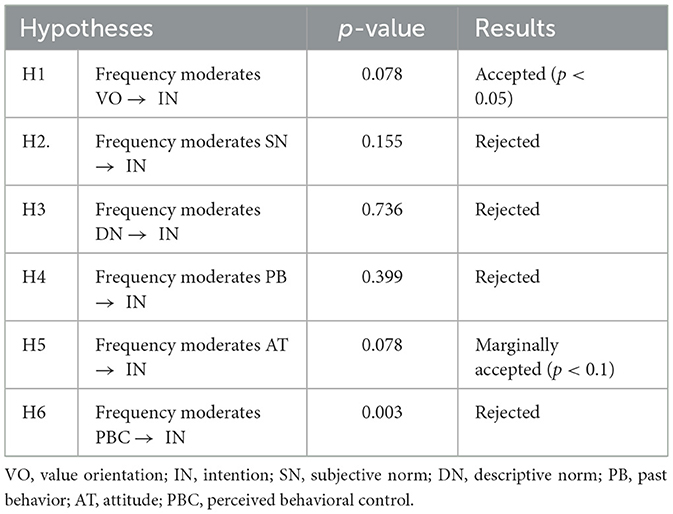

See Table 3 for a summary of results.

Table 3. Hypotheses and summary of the results for the moderating effect of frequency of participation of birdwatchers in the events on the relationship between predictors and intention toward disturbance behavior on birds.

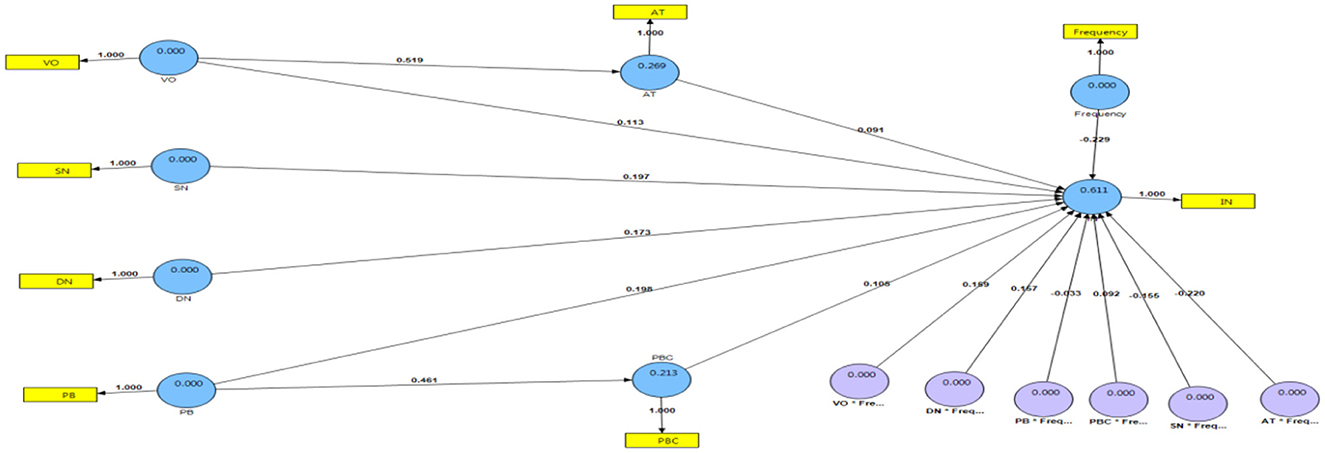

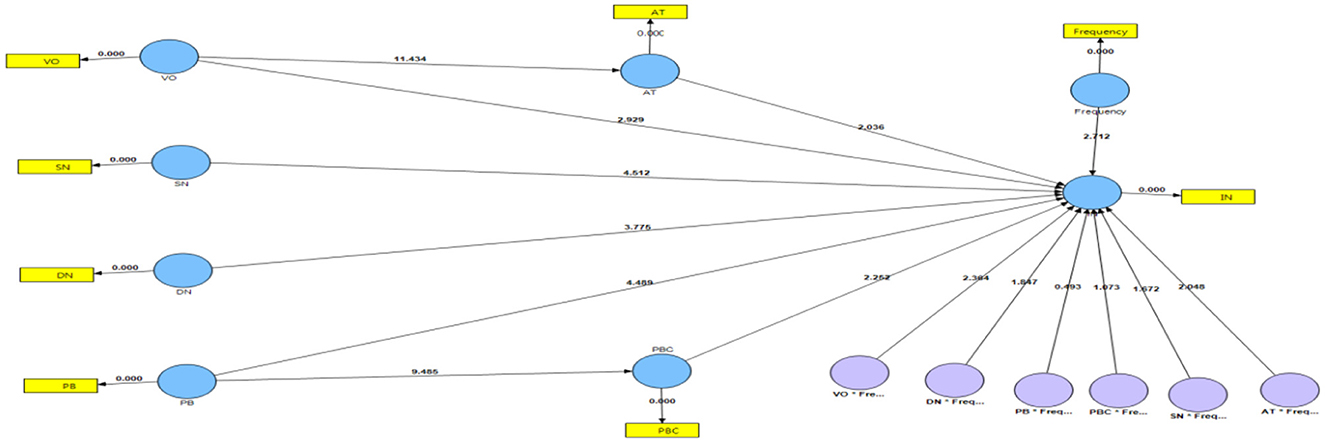

The moderator model before bootstrapping, after bootstrapping and the final moderator model are shown in Figures 2–4, respectively.

Figure 2. Structural model with moderating effects of frequency of participation before bootstrapping for behavioral intention toward disturbance behavior on birds The numbers on paths between constructs have shown path coefficient, and the numbers on paths between constructs and items have shown outer weight values before bootstrapping. The numbers in the circles have shown variances. The interaction terms between every main construct and frequency are shown by VO * Frequency, DN * Frequency, PB * Frequency, PBC * Frequency, SN * Frequency, and AT * Frequency. VO, value orientation; SN, subjective norms; DN, descriptive norms; PB, past behavior; AT, attitude; PBC, perceived behavioral control; IN, intention.

Figure 3. Structural model with moderating effects of frequency of participation after bootstrapping for Behavioral intention toward disturbance behavior on birds. The numbers on paths between constructs show the t-value, and the numbers on paths between constructs and items show outer weight values after bootstrapping. The interaction terms between every main construct and frequency have shown by VO * Frequency, DN * Frequency, PB * Frequency, PBC * Frequency, SN * Frequency, and AT * Frequency. VO, value orientation; SN, subjective norms; DN, descriptive norms; PB, past behavior; AT, attitude; PBC, perceived behavioral control; IN, intention.

Figure 4. Final moderation results with significant paths for behavioral intention toward disturbance behavior on birds. AT * Frequency= interaction term between attitude and frequency of participation; VO * Frequency, interaction term between value orientation and frequency of participation in the events by respondents. VO, value orientation; SN, subjective norms; DN, descriptive norms; PB, past behavior; PBC, perceived behavioral control; AT, attitude.

Summarizing the moderator model results, the moderator role of FOP in all defined relationships in the model of study was explored. Our current research revealed evidence that highlighted the importance of FOP (as an index for experience) in moderating the relationship between VO and IN toward disturbance behavior among respondents (p < 0.05) and shows the moderator role of FOP between Att and IN (p < 0.1). The frequency of participation does not moderate other defined relationships in the model of study.

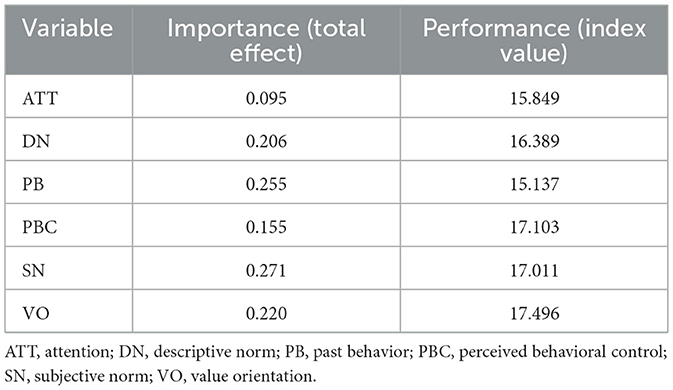

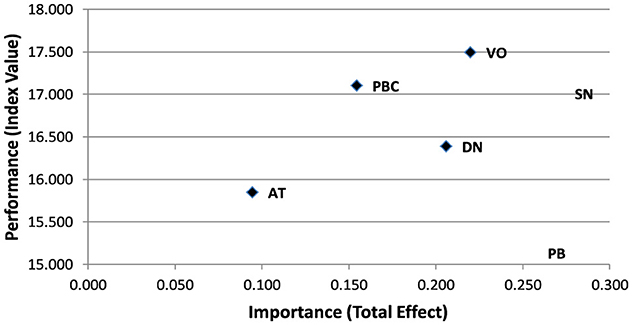

4.2 IPMA results

We present the IPMA results for the intentions toward disturbance behaviors on birds among Malaysian birdwatchers. The goal was to conduct an IPMA of the target construct IN. Before running the analysis, the data were rescaled. The rescaling of the latent variables and the index value computation are carried out automatically by the SmartPLS software when rescaled indicator data are used. The rescaled data was opened in SmartPLS. The results from the rescaled data were needed for IPMA of the target construct IN. Table 4 presents the results of the total effects (importance) and index values (performance) used for the IPMA. These data allow an IPMA representation to be created, as shown in Figure 5.

Table 4. Index values and total effects for the importance–performance matrix results for the intention construct toward disturbance behavior on birds among respondents.

Figure 5. Importance–performance matrix analysis representation on intention toward disturbance behavior on birds among respondents. AT, attitude; PBC, perceived behavioral control; VO, value orientation; DN, descriptive norms; SN, subjective norms; PB, past behavior.

As shown in Figure 5, the IPMA of intention revealed that SNs were of primary importance for establishing intentions toward target behaviors (disturbance behaviors on birds). In addition, its performance was slightly above average when compared to other constructs. VO was of slightly lower importance but still high compared to other constructs (DNs, PBC, and Att) and had the highest performance. DNs almost had a high effect if both importance and performance were considered, rather than other constructs, such as PB, which had very low performance, or PBC, which had rather lower importance. By comparison, Att had little relevance because it was of low importance and performance. However, comparing previous analysis results, which show SNs and DNs as the strongest predictors in the PBCM (Jafarpour and Ramkissoon, 2024), this analysis showed that SNs (rather than DNs) had high performance and importance. Although PB had rather high importance, the performance was low. PBC had almost high performance, and the importance was above average.

5 Discussions and conclusion on findings (H1–H6)

PBCM is modeled based on previous studies by Jafarpour and Ramkissoon (2023, 2024). In the current study, two main goals were assessed on the PBCM. The effect of FOP and the IPMA on the PBCM toward birdwatching on birds was checked.

Initially, six hypotheses are proposed and tested. This research revealed evidence highlighting the importance of FOP (as an index for experience) in moderating the relationship between VO and IN toward disturbance behaviors among respondents. Two hypotheses were accepted: H1 and H5. For H1, the frequency of participation moderates the relationship between VO and IN toward disturbance behavior on birds among respondents; it also shows the negative and significant moderating influence of FOP between Att and IN. Based on the operational definition of VO in our research, VOs are an expression of basic beliefs providing a foundation for higher order cognitions, such as attitudes and norms (Vaske et al., 2011). To clarify, if one of the defined disturbance behaviors, such as feeding birds, is considered a negative action, it seems that the probability of not doing that behavior with FOP increases. Then FOP shows a positive and significant moderating influence on the relation between VO and IN. For H5, FOP moderates the relationship between Att and IN toward disturbance behavior on birds among Malaysian birdwatchers.

Based on its operational definition, in our study, attitude is a psychological tendency expressed by evaluating a particular behavior with some degree of favor or disfavor (Kuehn et al., 2010). For example, if avitourists agree with the desired behavior, such as feeding birds, approaching or trampling the nest of birds, the probability of doing that behavior with FOP increases. Then FOP shows a negative and significant moderating influence on the relation between Att and IN. As a result, FOP has been included as an additional moderator construct to expand PBCM between these relationships. Moreover, studying the “dynamics” of attitudinal changes among avitourists will help in designing strategies for improving them as agents of conservation (Saha and Chakraborty, 2024).

Then policymakers can work on individuals' Atts and VOs of individuals, especially for people with more experience (FOP) to stop their disturbing behaviors. Decision-makers, for example, can work on the value orientations and attitudes of participants toward approaching birds' nests or trampling birds' nests when birding. The FOP can moderate the value orientations and attitudes of Malaysian avitourists for not approaching, trampling, or feeding birds. Based on the number of participants, level of participation, and expenditures, avitourists are an important part of wildlife watchers (Hvenegaard, 2002). FOP is a positive resource that improves the value orientations and attitudes of Malaysian participants for not doing disturbing behavior. Nevertheless, the FOP cannot moderate other defined relationships in the PBCM. Regarding other constructs (PBC, norms, and PB) in PBCM, FOP is shown to not be effective. The repetition of desired behavior cannot affect the relationships between PBC and IN, norms and IN, and PB and PBC.

There was little information regarding the role of FOP in the relationships in PBCM. However, we found the study by Rosli et al. (2022) extends TPB with PBC as a moderator on the Att, SNs, and behavioral IN. This article also emphasizes the importance and implications of the TPB and CHM. To conclude, the FOP can positively and significantly moderate the value orientations and attitudes of Malaysian avitourists regarding intention toward disturbance behaviors on birds. Saha and Chakraborty (2024) survey how several experiences (FOP in our research) in a birdwatching environment encourage birdwatchers to familiarize themselves with ecologically responsible behavior. Such experiences change one's attitude toward the environment (Saha and Chakraborty, 2024; Hunt and Harbor, 2019). The close interaction with nature can result in a modification in values, which people place a greater emphasis on sustainability and conservation (Olivos-Jara and Aragones, 2014; Saha and Chakraborty, 2024).

Additionally, IPMA was also tested. IPMA is the contrast of the total effects of a predictive variable that defines an objective construct, with their average latent variable scores indicating their performance (Fakfare and Manosuthi, 2023). The IPMA assist researchers in prioritizing variables on other components or indicator levels in the measurement model to develop a certain target construct (Schloderer et al., 2014). Although various approaches, such as analyzing path coefficients and their significance levels and asymmetric analysis, have been implemented for categorizing and prioritizing indicators in previous studies (Lee and Jan, 2018), these techniques have restricted angles in terms of prioritization and implications compared to IPMA. The previously mentioned methods cannot fully assist in analyzing the importance and performance of the identified variables (Ringle and Sarstedt, 2016).

A priority map analysis of PBMC showed that subjective norms were of primary importance for establishing intentions toward target disturbance behavior in birds. The performance of SN was slightly above average when compared to other constructs (VOs, DNs, PBC, and Att). SNs are perceptions of what important people think about disturbance behavior (such as feeding or trampling birds' nests). Compared to VO, the variable has more importance but less performance than VOs, which provides the foundation for higher cognitive variables such as attitude. For explanation, we could not find the resource for this explored part that compared VOs' and SNs' performance, but regarding their importance, it has previously been proved by Jafarpour and Ramkissoon (2024). VO was of slightly lower importance but still high compared to other constructs (DN, PBC, and Att) and had the highest performance. VO's importance in CHMs was shown in previous studies (e.g., Moghimehfar et al., 2020; Jafarpour and Ramkissoon, 2024). However, the Att had little relevance because it was of low importance and performance regarding the intentions toward disturbance behavior on birds. There are examples in which social behavior models were used in conservation science, highlighting how information about attitude revealed a limited picture concerning the predictors of the target behavior (Moghimehfar et al., 2020; St John et al., 2011). We found that DNs almost had a high effect if both importance and performance were considered compared to PB, which had very low performance, or PBC, which had rather lower importance. There is a strong correlation between descriptive norms and behavioral intention (Fornara et al., 2011; Göckeritz et al., 2010). A recent study on disturbance behavior among Malaysian avitourists has shown that, after SNs, DNs were the strongest predictors and had the strongest effect on IN toward disturbance behavior on birds (Jafarpour and Ramkissoon, 2024). We could not find the resource for this explored portion that compared VOs' and SNs' performance regarding disturbance behavior on birds.

However, comparing previous analysis results, which show subjective norms and descriptive norms as the strongest predictors in the PBCM (Jafarpour and Ramkissoon, 2024), this analysis showed that SNs (rather than DNs) had high performance and importance. This result shows that SNs which are the perception about what important people think a person should do (Forward, 2009), have higher importance and performance than DNs which are the perceptions about what people do (Forward, 2009). Although PB had rather high importance (Jafarpour and Ramkissoon, 2024), the performance was low. PBC had an almost high performance (Jafarpour and Ramkissoon, 2024), and the importance was above average.

6 Significant implications of the research

The influence of FOP as a moderator on the relationships in the PBCM was assessed. Only two relationships were significant. The We developed PBCM, and it includes integrated theories, TPB, and CHM, as well as an assessment of the influence of FOP as a moderator. The FOP was only significant on the relationship between VO and IN and Att and IN. These findings can help decision-makers and wildlife managers focus on participants' VO, which is an expression of avitourists' basic beliefs, providing a foundation for higher order cognitions, such as attitude.

Wildlife Value Orientations (WVOs) are conceptual dispositions reflecting general thoughts about wildlife (Fulton et al., 1996). WVOs predict behavioral intentions concerning wildlife, attitudes toward wildlife species or issues, management actions and conservation support, and the influence of ecological information on landscape preference that are beneficial for wildlife (Jacobs et al., 2022). Hence, WVOs inform more specific thoughts and behaviors related to wildlife (Jacobs et al., 2022). One way to understand people's relationship with the environment, especially wildlife, is to measure WVO (Morales-Nin et al., 2021). WVOs affect the general support of biodiversity conservation (Fulton et al., 1996; Manfredo et al., 2021b). It has been suggested that wildlife management should be “tailored” to WVOs to influence stakeholders' attitudes. Then, an individual's WVOs can have a significant influence on their attitudes toward wildlife and its management (Ehrhart et al., 2022).

To conclude the second part of this research, we present and discuss IPMA results for the intentions toward disturbance behaviors on birds among Malaysian birdwatchers. This analysis adds another dimension for assessing tourist behavior. This second dimension can help managers and tour operators focus more on values rather than other predictors of PMCM regarding avitourists to reduce disturbance behaviors on birds among Malaysian avitourists.

7 Limitation

Despite the theoretically meaningful findings, the study has some limitations. The individuals for this research were derived from 421 Malaysian birdwatchers who participated in the events (see Appendix) from March 2013 to August 2014 and cannot be generalized to other countries because WVOs vary by country (Jacobs et al., 2022). We explored and discussed this research theoretically and practically, while the literature reviews for some parts in this area were almost absent. We expanded the literature review for future research.

8 Signpost for future research

Current threats to global biodiversity have led many scientists to study the consequences of human-induced disruptions on wildlife. These potential threats have already been well-documented, and many conservation measures aim to reduce their impact. However, disturbance induced by non-consumptive leisure, such as birdwatching activity, has long been neglected. This will require quantifying the effect of disturbance behavior of non-consumptive leisure activities on wildlife and being able to assess how adaptive management may mitigate the effects of disturbance on wildlife. Such objectives will probably require heavy work, but this kind of research is crucially needed if we want to be able to combine legitimate non-consumptive human leisure activity and wildlife, which is required for the sustainable development of tourists in future (Ramkissoon, 2020, 2023a,b). From the view of a signpost for future research, replicating this research using samples from other countries could be a fruitful attempt to confirm a robust conclusion of the findings.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the [patients/participants OR patients/participants legal guardian/next of kin] was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

MJ: Investigation, Validation, Conceptualization, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Software, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Data curation, Resources, Methodology, Project administration. HR: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The first author, Marjan Jafarpour, is grateful to Dr. Manohar Mariapan, who assisted her as her supervisor during her Ph.D. period.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsut.2025.1594183/full#supplementary-material

References

Anderson, E. W., and Fornell, C. (2000). Foundations of the American customer satisfaction index. Total Qual. Manag. 11, 869–882. doi: 10.1080/09544120050135425

Brookhouse, N., Bucher, D. J., Rose, K., Kerr, I., and Gudge, S. (2013). Impacts, risks and management of fish feeding at Neds Beach, Lord Howe Island Marine Park, Australia: a case study of how a seemingly innocuous activity can become a serious problem. J. Ecotour. 12, 165–181. doi: 10.1080/14724049.2014.896369

Cabral, C., and Dhar, R. L. (2020). Ecotourism research in India: From an integrative literature review to a future research framework. J. Ecotour. 19, 23–49. doi: 10.1080/14724049.2019.1625359

Carranza, R., Díaz, E., and Martín-Consuegra, D. (2018). The influence of quality on satisfaction and customer loyalty with an importance-performance map analysis: exploring the mediating role of trust. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 9, 380–396. doi: 10.1108/JHTT-09-2017-0104

Cheung, L. T., Lo, A. Y., and Fok, L. (2017). Recreational specialization and ecologically responsible behaviour of Chinese birdwatchers in Hong Kong. J. Sust. Tour. 25, 817–831. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2016.1251445

Dou, X., and Day, J. (2020). Human-wildlife interactions for tourism: a systematic review. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 3, 529–547. doi: 10.1108/JHTI-01-2020-0007

Ehrhart, S., Stühlinger, M., and Schraml, U. (2022). The relationship of stakeholders' social identities and wildlife value orientations with attitudes toward red deer management. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 27, 69–83. doi: 10.1080/10871209.2021.1885767

Fakfare, P., and Manosuthi, N. (2023). Examining the influential components of tourists' intention to use travel apps: the importance–performance map analysis. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 6, 1144–1168. doi: 10.1108/JHTI-02-2022-0079

Fornara, F., Carrus, G., Passafaro, P., and Bonnes, M. (2011). Distinguishing the sources of normative influence on proenvironmental behaviors: the role of local norms in household waste recycling. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 14, 623–635. doi: 10.1177/1368430211408149

Fornell, C., Johnson, M. D., Anderson, E. W., Cha, J., and Bryant, B. E. (1996). The American customer satisfaction index: nature, purpose, and findings. J. Market. 60, 7–18. doi: 10.1177/002224299606000403

Forward, S. E. (2009). The theory of planned behaviour: the role of descriptive norms and past behaviour in the prediction of drivers' intentions to violate. Transport. Res. Part F 12, 198–207. doi: 10.1016/j.trf.2008.12.002

Fulton, D. C., Manfredo, M. J., and Lipscomb, J. (1996). Wildlife value orientations: a conceptual and measurement approach. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 1, 24–47. doi: 10.1080/10871209609359060

Göckeritz, S., Schultz, P. W., Rendón, T., Cialdini, R. B., Goldstein, N. J., and Griskevicius, V. (2010). Descriptive normative beliefs and conservation behavior: the moderating roles of personal involvement and injunctive normative beliefs, Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 40, 514–523. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.643

Griffin, L. L., Haigh, A., Amin, B., Faull, J., Norman, A., and Ciuti, S. (2022). Artificial selection in human-wildlife feeding interactions. J. Anim. Ecol. 91, 1892–1905. doi: 10.1111/1365-2656.13771

Hair, J. F. Jr., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N. P., and Ray, S. (2021). Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook. Cham: Springer, 197. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-80519-7

Henseler, J., and Chin, W. W. (2010). A comparison of approaches for the analysis of interaction effects between latent variables using partial least squares path modeling. Struct. Equat. Model. 17, 82–109. doi: 10.1080/10705510903439003

Hughes, M., and Carlsen, J. (2008). Human–wildlife interaction guidelines in Western Australia. J. Ecotour. 7, 147–159. doi: 10.1080/14724040802140519

Hunt, C. A., and Harbor, L. C. (2019). Pro-environmental tourism: lessons from adventure, wellness and eco-tourism (AWE) in Costa Rica. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 28. doi: 10.1016/j.jort.2018.11.007

Hvenegaard, G. T. (2002). Birder specialization differences in conservation involvement, demographics, and motivations. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 7, 21–36. doi: 10.1080/108712002753574765

Jacobs, M. H., Dubois, S., Hosaka, T., Ladanović, V., Muslim, H. F. M., Miller, K. K., et al. (2022). Exploring cultural differences in wildlife value orientations using student samples in seven nations. Biodivers. Conserv. 31, 757–777. doi: 10.1007/s10531-022-02361-5

Jacobs, M. H., Vaske, J. J., Teel, T. L., and Manfredo, M. J. (2018). “Human dimensions of wildlife,” in Environmental Psychology: An Introduction, eds. L. Steg, and J. I. M. de Groot (John Wiley & Sons), 85–94. doi: 10.1002/9781119241072.ch9

Jafarpour, M., and Ramkissoon, H. (2023). Developing a conservation behaviour scale for understanding birdwatchers' behaviour towards birds. J. Ecotour. 23, 539–562. doi: 10.1080/14724049.2023.2279491

Jafarpour, M., and Ramkissoon, H. (2024). A new cognitive conservation model for understanding Malaysian birders' behaviour towards birds. J. Ecotour. 24, 172–195. doi: 10.1080/14724049.2024.2385100

Kim, A. K., Keuning, J., Robertson, J., and Kleindorfer, S. (2010). Understanding the birdwatching tourism market in Queensland, Australia. Anatolia 21, 227–247. doi: 10.1080/13032917.2010.9687101

Kucukergin, K. G., and Gürlek, M. (2020). ‘What if this is my last chance?': developing a last-chance tourism motivation model. J. Destin. Market. Manag. 18:100491. doi: 10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100491

Kuehn, D. M., Sali, M. J., and Schuster, R. (2010). Motivations of male and female shoreline bird watchers in New York. Tour. Marine Environ. 6, 25–37. doi: 10.3727/154427309X12602327200262

Lee, T. H., and Jan, F. H. (2018). Ecotourism behavior of nature-based tourists: an integrative framework. J. Travel Res. 57, 792–810. doi: 10.1177/0047287517717350

Manfredo, M. J., Teel, T. L., Berl, R. E., Bruskotter, J. T., and Kitayama, S. (2021a). Social value shift in favour of biodiversity conservation in the United States. Nat. Sust. 4, 323–330. doi: 10.1038/s41893-020-00655-6

Manfredo, M. J., Vaske, J. J., and Sikorowski, L. (2021b). “Human dimensions of wildlife management,” in Natural Resource Management, ed. A. W. Ewert (New York, NY: Routledge), 53–72. doi: 10.4324/9780429039706-6

Marasinghe, S., Simpson, G. D., Newsome, D., and Perera, P. (2020). Scoping recreational disturbance of shorebirds to inform the agenda for research and management in Tropical Asia. Trop. Life Sci. Res. 31, 51–78. doi: 10.21315/tlsr2020.31.2.4

Moghimehfar, F., Halpenny, E. A., and Harshaw, H. (2020). Ecological worldview, attitudes, and visitors' behaviour: a study of front-country campers. J. Ecotour. 19, 176–184. doi: 10.1080/14724049.2019.1621881

Mokhter, N., Akhsan, M. A., Amran, M. A., Lee, T. J., ZAINAL, Z., and BAKAR, M,. A. (2022). Birding hotspots and important bird species as tools to promote avitourism in Pulau Tinggi, Johor, Malaysia. J. Sust. Sci. Manag. 17, 110–120. doi: 10.46754/jssm.2022.11.012

Morales-Nin, B., Arlinghaus, R., and Alós, J. (2021). Contrasting the motivations and wildlife-related value orientations of recreational fishers with participants of other outdoor and indoor recreational activities. Front. Mar. Sci. 8:714733. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.714733

Newsome, P. N., Sasso, M., Deeks, J. J., Paredes, A., Boursier, J., Chan, W. K., et al. (2020). FibroScan-AST (FAST) score for the non-invasive identification of patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis with significant activity and fibrosis: a prospective derivation and global validation study. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 5, 362–373. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30383-8

Ng, W. I. V., and Norazlimi, N. A. (2022). The diversity and potential of avitourism in peat swamp ecosystem of Ayer Hitam Utara Forest Reserve, Johor. J. Sust. Nat. Resour. 3, 73–84. doi: 10.30880/jsunr.2022.03.01.007

Olivos-Jara, P., and Aragones, J. I. (2014). Environment, self and connectedness with nature. Rev. Mexicana Psicol. 31, 71–77.

Phu, N. H., Hai, P. T., Yen, H. T. P., and Son, P. X. (2019). Applying theory of planned behaviour in researching tourists' behaviour: the case of Hoi An World Cultural Heritage site, Vietnam. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 8.

Ramkissoon, H. (2020). COVID-19 Place confinement, pro-social, pro-environmental behaviors, and residents' wellbeing: a new conceptual framework. Front. Psychol. 11:2248. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02248

Ramkissoon, H. (2023a). “Introduction to the handbook on tourism and behaviour change,” in Handbook on Tourism and Behaviour Change (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing), 1–19. doi: 10.4337/9781800372498.00006

Ramkissoon, H. (2023b). Perceived social impacts of tourism and quality-of-life: a new conceptual model. J. Sust. Tour. 31, 442–459. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2020.1858091

Rigdon, E. E., Ringle, C. M., and Sarstedt, M. (2010). Structural modeling of heterogeneous data with partial least squares. Rev. Market. Res. 7, 255–296. doi: 10.1108/S1548-6435(2010)0000007011

Ringle, C. M., and Sarstedt, M. (2016). Gain more insight from your PLS-SEM results: the importance-performance map analysis. Indus. Manag. Data Syst. 116, 1865–1886. doi: 10.1108/IMDS-10-2015-0449

Rodger, K., Smith, A., Newsome, D., and Moore, S. A. (2011). Developing and testing an assessment framework to guide the sustainability of the marine wildlife tourism industry. J. Ecotour. 10, 149–164. doi: 10.1080/14724049.2011.571692

Rosli, N. A., Zainuddin, Z., Yusliza, M. Y., Muhammad, Z., Saputra, J., Nordin, A. O. S., et al. (2022). Moderating effect of perceived behavioural control on tourists' revisit intention in island tourism industry: a conceptual model. J. Environ. Manag. Tour. 13, 2230–2239. doi: 10.14505/jemt.13.8(64).15

Saha, D., and Chakraborty, A. (2024). Influence of avitourism experience in developing environmentally responsible behaviour. Tour. Recreat. Res. 1–14. doi: 10.1080/02508281.2024.2393514

Samdin, Z., Abdullah, S. I. N. W., Khaw, A., and Subramaniam, T. (2022). Travel risk in the ecotourism industry amid COVID-19 pandemic: ecotourists' perceptions. J. Ecotour. 21, 266–294. doi: 10.1080/14724049.2021.1938089

Santos, M., Carvalho, D., Luis, A., Bastos, R., Hughes, S. J., and Cabral, J. A. (2019). Can recreational ecosystem services be inferred by integrating non-parametric scale estimators within a modelling framework? The birdwatching potential index as a case study. Ecol. Indicat. 103, 395–409. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2019.04.026

Schloderer, M. P., Sarstedt, M., and Ringle, C. M. (2014). The relevance of reputation in the nonprofit sector: the moderating effect of socio-demographic characteristics. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sector Market. 19, 110–126. doi: 10.1002/nvsm.1491

Serota, M. W., Barker, K. J., Gigliotti, L. C., Maher, S. M., Shawler, A. L., Zuckerman, G. R., et al. (2023). Incorporating human dimensions is associated with better wildlife translocation outcomes. Nat. Commun. 14:2119. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-37534-5

St John, F., Edwards-Jones, G., and Jones, J. P. G. (2011). Conservation and human behaviour: lessons from social psychology. Wildlife Res. 37, 658–667. doi: 10.1071/WR10032

Steven, R., Rakotopare, N., and Newsome, D. (2020). “Avitourism tribes: as diverse as the birds they watch,” in Consumer Tribes in Tourism: Contemporary Perspectives on Special-Interest Tourism, eds. C. Pforr, R. Dowling, and M. Volgger (Singapore: Springer Singapore), 101–118. doi: 10.1007/978-981-15-7150-3_8

Sumanapala, D., and Wolf, I. D. (2020). Think globally, act locally: current understanding and future directions for nature-based tourism research in Sri Lanka. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 45, 295–308. doi: 10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.08.009

Tan, X., Yan, P., Liu, Z., Qin, H., and Jiang, A. (2023). Demographics, behaviours, and preferences of birdwatchers and their implications for avitourism and avian conservation: a case study of birding in Nonggang, Southern China. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 46:e02552. doi: 10.1016/j.gecco.2023.e02552

Tenenhaus, M., Vinzi, V. E., Chatelin, Y. M., and Lauro, C. (2005). PLS path modeling. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 48, 159–205. doi: 10.1016/j.csda.2004.03.005

Tuneu, C., Carme, S., Usui, R., and Funck, C. (2018). Analysing food-derived interactions between tourists and sika deer (Cervus nippon) at Miyajima Island in Hiroshima, Japan: implications for the physical health of deer in an anthropogenic environment. J. Ecotour. 17, 67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.adengl.2017.11.016

Usui, R., and Funck, C. (2018). Analysing food-derived interactions between tourists and sika deer (Cervus nippon) at Miyajima Island in Hiroshima, Japan: implications for the physical health of deer in an anthropogenic environment. J. Ecotour. 17, 67–78. doi: 10.1080/14724049.2017.1421641

Vaske, J. J., Jacobs, M. H., and Sijtsma, M. T. J. (2011). Wildlife value orientations and demographics in the Netherlands. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 57, 1179–1187. doi: 10.1007/s10344-011-0531-0

Völckner, F., Sattler, H., Hennig-Thurau, T., and Ringle, C. M. (2010). The role of parent brand quality for service brand extension success. J. Serv. Res. 13, 379–396. doi: 10.1177/1094670510370054

Weston, M. A., Guay, P. J., McLeod, E. M., and Miller, K. K. (2015). Do birdwatchers care about bird disturbance? Anthrozoös 28, 305–317. doi: 10.1080/08927936.2015.11435404

Keywords: conservation model, birdwatching, ecotourism, frequency of participation (FOP), theory of planned behavoir (TBP), human dimensions, the importance–performance matrix analyses (IPMA), avitourist

Citation: Jafarpour M and Ramkissoon H (2025) Developing a cognitive conservation model for the management of Malaysian birders' behavior toward birds. Front. Sustain. Tour. 4:1594183. doi: 10.3389/frsut.2025.1594183

Received: 15 March 2025; Accepted: 11 August 2025;

Published: 01 October 2025.

Edited by:

James Edward Brereton, Sparsholt College, United KingdomReviewed by:

Uwe Peter Hermann, Tshwane University of Technology, South AfricaDebankur Saha, IFMR Graduate School of Business, India

Copyright © 2025 Jafarpour and Ramkissoon. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marjan Jafarpour, bWFyamFuLmphZmFycG9vckBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Marjan Jafarpour

Marjan Jafarpour Haywantee Ramkissoon

Haywantee Ramkissoon