- 1Department of Business Management Education, Faculty of Education, Walter Sisulu University, Mthatha, South Africa

- 2Research Unit, Tourism Research in Economics, Environments & Society (TREES), School of Tourism Management, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa

Introduction: This study explored the critical factors for building a foundation for local community participation in tourism planning in the Hwange District, Zimbabwe. The participation of local communities in tourism planning is critical for good governance, fostering a symbiosis between tourism development and community aspirations, sustainable development and effective conservation in nature-based destinations of developing countries.

Methods: A qualitative approach grounded in the interpretivist paradigm, involving semi-structured interviews with 22 key informants, was adopted, and the data were thematically analyzed.

Results and discussion: The key findings indicate that fully implementing all key participatory legislation and policies, revitalizing participatory sectoral planning legislation, acknowledging and remedying conservation and tourism development injustices and costs, addressing communal land tenure and security and revitalizing and reforming community-based conservation are critical for building a foundation for effective local community participation in tourism planning. The study recommends the creation of an overarching, district-level integrated planning framework centered on the district's local authorities to lead tourism planning for coordinated and inclusive development. The insights from this study contribute to the burgeoning literature on building the role of local communities in tourism planning in nature-based destinations of developing countries and lay a foundation for dialogue and further related research. The findings could also inform tourism and conservation legislation and policies aimed at advancing local community empowerment and sustainable development in developing countries.

1 Introduction

In recent years, critical scholarship has increasingly advocated centring destination communities in planning to foster and sustain a symbiotic relationship between tourism development and community aspirations (Harilal et al., 2021; Weaver et al., 2021). This upsurge in calls to recalibrate tourism planning and development, privileging participatory approaches, derives from a dynamic and complex interplay of political, social, economic, technical, and ecological factors at local, national, and global levels. The mounting disquiet about growth-fixated models grounded on modernistic and neoliberal hegemonic impulse, calculated to maximize dividends for conglomerates, extracting commons at the expense of social, cultural and environmental integrity (Higgins-Desbiolles, 2020; Mbaiwa and Hambira, 2019), consternation in some parts of the developed world over destinations surpassing their carrying capacity and the resultant upheavals are driving calls for community-centered tourism planning and development (Weaver et al., 2021). In developing countries, deep-rooted exclusionary conservation and tourism planning, development, and management approaches are increasingly facing stiff resistance from local communities, with scholars advocating for reforms and human-rights-based approaches that center such communities in planning and development (Thondhlana et al., 2016; Siakwah et al., 2020). In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic that decimated and exposed the frailties of the tourism sector, globally, there is a renewed realization that solutions to contemporary complex challenges framed as “wicked” as exemplified by health pandemics, intractable social disparities and climate change, with pervasive social, ecological and economic impacts lie in paradigmatic holistic and multi-actor approaches that actively integrate communities (Candel, 2017; Higgins-Desbiolles, 2020; Weaver et al., 2021). Markedly, the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and its 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) strongly mobilized on leaving no one behind and the active partnership of “all countries, all stakeholders, and all people” has reaffirmed and vivified public participation as a fundamental tenet of sustainable development (United Nations, 2015, p. 4).

Some scholars in developing countries underline that sustainable tourism development in nature-based destinations is likely to materialize through inclusive and participatory planning practices that center local communities, acknowledge their territorial rights, worldviews, dignity, and customary practices, and integrate social and ecological justice into policies, decision-making, and planning (Buzinde and Caterina-Knorr, 2022; Thondhlana et al., 2016). Notably, Southern Africa studies focusing on the inclusion of local communities in tourism planning, policymaking, and conservation in regions dominated by protected areas, where nature-based tourism and conservation systems are intricately intertwined, such as Zimbabwe's Hwange District, extol the potential utility of the practice in balancing delicate conservation, tourism development, and livelihood imperatives (Musakwa et al., 2020; Siakwah et al., 2020). Despite this acknowledged potential to emancipate and empower marginalized groups and advance sustainable development and effective conservation, local community participation in tourism planning remains sparse and unexploited in most countries in the Global South, including Zimbabwe (Gohori and van der Merwe, 2021; Siakwah et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2019). Although numerous studies, particularly in Southern Africa's nature-based destinations, reflect a pessimistic outlook on the role of local communities in tourism planning, development, and biodiversity conservation (Mbaiwa and Hambira, 2019; Siakwah et al., 2020), there is also a paucity of empirical evidence to inform the fashioning of effective policy responses, measures and frameworks to stimulate and sustain local community participation (Harilal et al., 2021). Consequently, there are renewed calls for fine-grained, nuanced, and context-specific studies, particularly in Global South countries, to expand our understanding of the foundational conditions, enablers and strategies for cultivating and enhancing local community participation in tourism planning and development (Harilal et al., 2021; Zielinski et al., 2020). This study responds to such calls for a deeper examination of context-specific factors that foster local community participation in tourism planning, focusing on the Hwange District in Zimbabwe.

Hwange District is arguably Zimbabwe's tourism and biodiversity conservation epicenter, encapsulating areas under the jurisdiction of the Hwange Rural District Council (HRDC), the Hwange Local Board (HLB), and the City of Victoria Falls. It hosts iconic tourism attractions, including Hwange National Park (HNP), the globally renowned World Heritage Site (WHS), and one of the seven natural wonders of the world, Victoria Falls. In addition, it boasts several other pristine protected areas, including Victoria Falls, Zambezi and Kazuma Pan National Parks, Sikumi, Fuller, and Panda Masuie Forests, as well as the Matetsi and Deka Safari Areas, which collectively cover approximately 75% of the district's land [Vuola, 2022; Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority (ZPWMA), 2016], supporting a multi-million dollar environmental and nature-based tourism industry (Mushawemhuka et al., 2018; Sagiya, 2020). The ZPWMA and the Zimbabwe Forestry Commission (ZFC), both designated planning authorities, manage all protected areas in the district, mainly through a top-down exclusionary approach (Mushonga and Matose, 2020; Perrotton et al., 2017). The ZPWMA holds an even broader statutory mandate, administering national parks and overseeing the management of the country's entire wildlife population across private and communal lands (Musakwa et al., 2020). Besides the ZPWMA, outside the protected area system, the district's three local authorities, each with a distinct development planning system, and numerous state authorities and agencies with top-down mandates, collectively share jurisdiction over natural and cultural heritage, a vital tourism resource base (Mhlanga, 2009; Mpofu, 2020; Sagiya, 2020). Existing studies (Manyena, 2013; Mhlanga, 2009; Sagiya, 2020) suggest that the excessively fragmented institutional and development planning landscape in the district largely contributes to the preponderance of fragmented and sectoral planning, incoherent tourism strategies, sectoral conflicts, and the marginalization of local communities in tourism planning and conservation.

Following Zimbabwe's partnership with the governments of Angola, Botswana, Namibia, and Zambia to implement the Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area (KAZA TFCA), a conservation and tourism initiative, all the district's main protected areas were incorporated into the project (Sagiya, 2020). Integrating vast areas into the KAZA TFCA has made tourism and nature conservation inevitable for local communities. Their settlements and agricultural lands have become default biodiversity corridors, enabling connectivity and unimpeded wildlife migration within the complex protected area system. Due to the extensive unfenced protected area system, the district is ill-reputed for the debilitating Human-Wildlife Conflict (HWC) scourge (Guerbois et al., 2012), which is poised to intensify with the expansion of conservation and tourism frontiers beyond protected areas as the KAZA TFCA reaches maturity (Vuola, 2022). Implementing an initiative on the scale of the KAZA TFCA requires a landscape-scale approach that integrates policy and practice for mosaic land uses, amplifying the need to incorporate a diverse array of sectors and stakeholders, particularly local communities, in biodiversity conservation and associated tourism planning and development (Chirozva et al., 2017; Musakwa et al., 2020). Although internationally lauded for their exceptional potential to springboard tourism growth, inclusive development, and regional integration, transboundary conservation initiatives still divide scholars due to their top-down natural resource governance that undervalues local knowledge and reinforces the exclusionary paradigm, prompting many to call for empirical studies to refine the model to prioritize local communities in biodiversity conservation and related tourism planning and development (Chirozva et al., 2017). Despite the additional layer of the KAZA TFCA and the district's enduring worldwide prime standing in conservation and nature-based tourism spheres, it has received comparatively limited and insufficient academic attention regarding the participation of local communities in tourism planning and development (Manyena, 2013; Mpofu, 2020; Shereni and Saarinen, 2020), particularly when compared to other less-endowed nature-based destinations in the country. Hence, this study sought to fill the void by exploring the foundational factors necessary to simulate, enhance, and sustain local community participation in tourism planning within the Hwange District, Zimbabwe. For this study, the foundation for participation in tourism planning is conceptualized as any catalyst, enabling condition, or strategic intervention that fosters meaningful participation by local communities. The district's profile as a biodiversity hotspot and nature-based tourism region with emerging conservation initiatives presented a relevant context for exploring such participatory dynamics.

2 Literature review

2.1 Local community participation in tourism planning

The notion of participation has a well-documented history in scholarship, policy, and practice, holding worldwide appeal as an alternative to top-down governance and a requirement for sustainable development (Malek and Costa, 2014; Newig et al., 2023). In an early account, Arnstein (1969, p. 216) defined participation as a “categorical term for citizen power” and the redistribution of power enabling the integration of previously marginalized citizens in the political and economic processes. For Rowe and Frewer (2004, p. 253), participation is “the practice of involving members of the public in the agenda setting, decision-making, and policy or problem at hand”. A common thread in these definitions is the framing of participation as a vehicle for empowering and including citizens in planning, policymaking, and implementation. Ianniello et al. (2018) note that while citizen participation takes various guises and terminology across different levels and sectors, such as civic dialogue, interactive decision-making, and stakeholder inclusion, it functions as a procedural instrument to enhance the decision-making quality, integrate local values, build capacity, promote equity, and mitigate unhealthy conflict.

Although tourism, like other impactful sectors, is experiencing a renewed surge aimed at addressing complex sustainable development challenges by recalibrating planning systems to privilege pluralistic and integrative approaches that center local communities (Harilal et al., 2021; Higgins-Desbiolles and Bigby, 2023; Weaver et al., 2021), policymakers and scholars, have grappled with the notion of community-centered planning in sector for decades. Community participation has been championed since the 1970s by scholars like Murphy (1985), whose seminal book on a community approach to tourism is credited with disseminating broad-based planning approaches and underlining the role of communities in destination planning for balanced and positive environmental, economic and sociocultural outcomes. Over the years, tourism and policy scholars have listed community participation in planning as a subset of public participation (Buono et al., 2012; Xu et al., 2019), emphasizing the local community's role in decision-making (planning) and benefit-sharing (Timothy, 1999). Benefit-sharing, a ubiquitous yet often passive form of participation, enables local communities to leverage tourism development and its associated dividends, such as access to capacity building, social amenities, entrepreneurship, livelihood resources, and employment (Malek and Costa, 2014; Xu et al., 2019). In contrast, participation in decision-making (planning) is transformative as it seeks to calibrate power dynamics, requiring communities to collaborate with other destination stakeholders to articulate their expectations and assert influence over planning, policymaking, and the developmental trajectory of the tourism sector (Timothy, 1999). In this regard, community participation in tourism planning is transformative, shifting away from unilateral and top-down approaches to embed planning and development within the lived experiences of local communities and incorporate their ideas, worldviews, aspirations, values, and knowledge (Su and Wall, 2013). It ensures that local communities are active architects of tourism policy, rather than victims or passive beneficiaries (Malek and Costa, 2014). In this study, we align with Ruhanen (2009), who asserts that community participation in tourism planning must be viewed as an interactive and collaborative effort between planners and local communities, complementing rather than supplanting conventional planning systems.

As in many policy fields, participatory planning in tourism is justified both implicitly and explicitly by normative, substantive, and instrumental rationales (Buono et al., 2012; Uittenbroek et al., 2019). The normative justification for participatory planning rests on ethical principles, societal values, and democratic ideals, aiming to foster fairness, social justice, and equity by prioritizing local communities affected by development (Glucker et al., 2013). For instance, Wray (2011) argued that incorporating the values and worldviews of marginalized communities in tourism development planning strengthens democracy and plurality and fosters citizenship. To this end, active citizenry and democratic ideals are realized when the local community voices are heard, captured and integrated into tourism plans and developments (Matteucci et al., 2021). Some scholars with a strong normative stance contend that local communities, as residents and custodians of destinations, disproportionately bear the negative externalities of tourism development, making it both procedurally fair and ethical to center them in policymaking, planning, and decision-making (Higgins-Desbiolles and Bigby, 2023). Critical scholars (Mushonga and Matose, 2020; Mutekwa and Gambiza, 2017), in nature-based destinations of developing countries, increasingly advocate for inclusive and participatory approaches, invoking justice and human rights imperatives, arguing that dominant biodiversity conservation and tourism development models, which exclude local communities from planning processes, violate human rights and fundamental sustainable development principles. Beyond the democratic and procedural justice imperatives, through participation, social learning is thought to materialize from the deep deliberations and resultant iterative sharing of knowledge among diverse interests and participants seeking joint solutions to developmental problems (Buono et al., 2012; Matteucci et al., 2021). Jager et al. (2019, p. 4) assert that participatory spaces, including diverse actors and interests, provide a fertile ground for social learning, which “goes beyond the individual and involves a group process of dissemination where knowledge becomes shared knowledge situated within a wider group”. As diverse interests engage in the exchange, building, and absorption of new knowledge in co-creating solutions, Matteucci et al. (2021) argue it not only facilitates the development of a shared language, enhances stakeholder competencies, and supports implementation, but also plays a central role in advancing sustainable tourism development, which must be constructed on knowledge from a broad range of stakeholders.

From a substantive rationale perspective, tourism scholars emphasize the capacity of participatory approaches to strengthen planning processes and enhance decision-making outcomes by providing quality information (Buono et al., 2012; Uittenbroek et al., 2019). For instance, scholars with a substantive slant argue for the inclusion of communities in planning to enable technocrats to leverage their rich repository of traditional worldviews and Indigenous knowledge systems, thereby expanding and enriching decision-making information (Glucker et al., 2013; Lane, 2005). It is argued that Indigenous communities, with their rooted sense of place, place-based traditions, enduring attachment, territorial intelligence, and expert knowledge of their unique contexts, which have been settled over millennia, are peculiarly placed to guide the most effective and sustainable development trajectory (Cundill et al., 2017; Malek and Costa, 2014). In a study conducted in the Hwange District, Dervieux and Belgherbi (2020) established that local communities possessed unique knowledge systems and practices accumulated over generations regarding weather systems, climate adaptation, environmental management, and sustainable resource utilization, which could be integrated into contemporary plans and strategies for managing protected areas and enhancing community resilience. Despite the increasing recognition of Indigenous knowledge as an asset for promoting diversity, conservation, and sustainable tourism development, Buzinde and Caterina-Knorr (2022) lament that conservation systems in African countries still prize exclusionary paradigms that suppress such knowledge and alienate local communities.

Finally, instrumental arguments for participatory planning emphasize its competence and effectiveness as a means of achieving robust, superior, practical, and durable outcomes in planning and decision-making (Buono et al., 2012). As Wray (2011) suggests, participatory tourism planning approaches create fertile ground for deep negotiation and reflexivity among diverse and conflicting interests, fostering compromise and enabling individual and collective learning, which results in superior outcomes. By allowing for the contestation, mediation, and reconciliation of diverse interests and conflicting priorities, participatory approaches facilitate the co-creation of tourism policies and initiatives that are inclusive, equitable, and responsive to the needs of all parties involved (Bramwell, 2010). Naturally, deeply deliberative planning platforms with diverse stakeholders, including local communities, are assumed to cultivate mutual interests, foster trust and increase the propensity to predict and forestall conflicts that may obstruct development (Uittenbroek et al., 2019). Adebayo and Butcher (2022) advocate for the early involvement of local communities in tourism planning to enable them to defend their interests, foster a sense of ownership, encourage support, and simplify implementation processes, which may otherwise face significant legal and procedural obstacles without their endorsement. The strength of participatory planning also lies in delivering spaces for deliberation for multiple stakeholders, including communities, enabling them to be heard and involved in the co-creation and co-design of policies and planning interventions, thereby building transparency in the process, which is central for the legitimacy and acceptance of planning outcomes (Glucker et al., 2013; Mohedano Roldán et al., 2019). For some communities in developing countries, having a seat at the table for tourism planning and decision-making is emancipatory and politically uplifting (Xu et al., 2019), enabling control over economic development, critical for delivering social services, including healthcare and education that are essential to psychological and economic empowerment (Scheyvens and van der Watt, 2021).

2.2 Fostering community participation in tourism planning

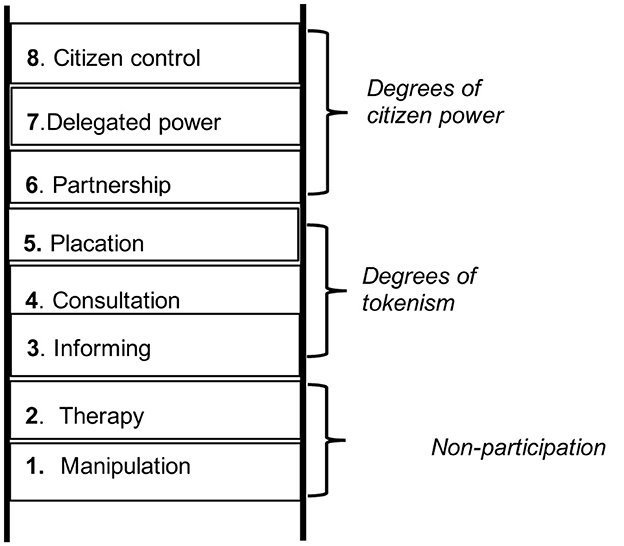

The literature extensively explores public participation in planning, providing a wealth of frameworks, models, and typologies that enrich theoretical understanding and practice across diverse fields and contexts (Arnstein, 1969; Rosen and Painter, 2019; Tosun, 2006). Arnstein's (1969) ladder of citizen participation remains seminal in policy discourse and planning practice among the plethora of frameworks, typologies, and models that have been developed. Arnstein (1969) proposed a participation framework that illustrates the varying degrees of citizen power and authority in shaping development outcomes through a figurative ladder with eight rungs. These eight rungs, which depict the different levels of participation and community influence in decision-making, were further distilled into three major categories: non-participation at the lowest level, degrees of tokenism at the intermediate level, and degrees of citizen power at the highest level (Arnstein, 1969). The ladder of citizen participation is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Arnstein's ladder of citizen participation (Arnstein, 1969, p. 217).

The ladder's bottom rungs illustrate non-participation, where decision-making power and control remain concentrated in the hands of powerholders, excluding communities from meaningful involvement in the processes (Arnstein, 1969). In varying degrees of tokenism, local communities are informed and consulted, but they have limited or no influence on decision-making and project implementation (Arnstein, 1969). Finally, the uppermost rungs of the ladder illustrate levels of citizen power and transformative participation, where citizens accrue substantial decision-making leverage, thereby building their capacity to forge partnerships and bargain with powerholders (Arnstein, 1969). The zenith of the ladder represents citizen control that “guarantees that participants or residents can govern a program or an initiation, be in full charge of policy and managerial aspects, and be able to negotiate the conditions under which outsiders may change them” (Arnstein, 1969, p. 223). In a metaphorical representation, Arnstein (1969) suggests that marginalized communities gain power and authority over development planning and decision-making as they ascend the ladder, implying that policies and measures to institutionalize community participation, including in tourism planning must concentrate on transformative approaches that foster deliberation, partnerships, co-creation, and provide substantive capacity and autonomy to the marginalized communities. Tosun (2006) built upon Arnstein's framework to develop a conceptual model that categorizes local community participation in tourism planning into three distinct types: coercive, induced, and spontaneous. Spontaneous participation was envisioned as equivalent to Arnstein's highest levels of citizen power, embodying the ideal of emancipation and empowerment, wherein local communities engage in self-mobilization, adopt endogenous strategies, and exercise full autonomy over tourism planning, development, and management (Tosun, 2006). Overall, Arnstein's (1969) degrees of citizen power and Tosun's (2006) spontaneous participation exemplify the transformative levels of participation that ought to inform the yardstick for policies and strategies in building a foundation for local community participation in tourism planning.

Building on established participatory models, interdisciplinary planning scholarship continues to identify the enablers and elements needed to develop and embed participatory planning practices. Supportive legal and policy frameworks in natural resource management and tourism development are considered critical for the meaningful inclusion of marginalized communities and the institutionalization of enduring participatory planning, management, and development (Gohori and van der Merwe, 2021; Springer et al., 2021). Legal and policy frameworks laying the groundwork for community participation and inclusive decision-making must be explicitly designed to guarantee inclusivity, prioritizing rights-holders and all relevant stakeholders. Furthermore, such legal and policy frameworks aimed at fostering a participatory culture should establish strong institutions and platforms that enable meaningful participation and an equitable distribution of conservation benefits, acknowledge Indigenous worldviews, and support the capacity-building of vulnerable local communities to engage effectively in planning and decision-making processes (Murombo, 2021). Equally significant is the role of institutions shaped by legal and policy frameworks, alongside the influence of public officials and technocrats who lead them, in embedding participatory planning and governance within institutional structures. As they can exercise their prerogative over who participates, manage resources, information, the participation agenda, the knowledge, and the competence of participants, Ianniello et al. (2018) argue that public officials wield disproportionate control over participatory planning and thus, to institutionalize effective citizen participation, such officials must adopt a constructive mindset, be willing to cede power, and cultivate trust in the expertise and insights of communities. Thus, the institutionalization of local community participation in tourism planning is a complex task that requires deep institutional reforms. As Nyaupane et al. (2020) argue from a protected area management perspective, the transition toward multi-stakeholder approaches to management, where the state agencies, communities, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and the private sector collaborate as equal partners in planning and decision-making necessitates viable institutional design and a radical shift in the mindset of administrators and policymakers. Therefore, unless public officials demonstrate openness and commitment to participatory approaches, local community participation may remain elusive, even with robust legal and policy frameworks.

Across the policy landscape, scholars have developed constructive guidelines for structuring and institutionalizing participatory approaches, offering valuable insights for tourism planning (Ianniello et al., 2018; Huber et al., 2023; Springer et al., 2021). For instance, Ianniello et al. (2018) draw some critical factors for initiating and sustaining public participation, privileging that participatory spaces must be inclusive, promote long-term interaction, deploy multiple participatory methods, prioritize diversity and representativity, de-emphasize hierarchical order and bureaucracy, integrate realistic short-term goals within strategic objectives, attune participatory tactics to local contexts, engage practiced and impartial facilitators, support networking, and accommodate all participants' agendas. Similarly, from a public policy angle, Fernandes et al. (2019) claim that local communities and other participants in planning should be involved earlier in the diagnosis phase to immerse themselves in the process, inject their ideas, build a common language and purpose, and develop a commitment to the process and its outcomes. For Springer et al. (2021), participative approaches and institutions in natural resource management, by extension, nature-based tourism, should be anchored in good governance principles, accenting transparency, accountability, inclusivity, equality, diversity, and the rule of law. Adhering to good governance in rooting participation in tourism planning and decision-making is critical for eradicating the potential abuse of power, corruption and elite capture, which erode trust in public institutions and impede participation (Islam et al., 2018). Overall, the above instructive guidelines highlight the need for more inclusive institutional infrastructure, participation procedures, and meticulous design of the participatory processes themselves in stimulating and maintaining the role of local communities in tourism planning.

Deliberate and concerted investment in capacity building is considered key to cultivating and sustaining the participation of local communities in tourism planning and development (Fariss et al., 2023; Xu et al., 2019). Hauptfeld et al. (2022, p. 1227) defined capacity building as “capturing the process by which individuals and communities transform their mindsets and attitudes and enhance the knowledge, skills, resources, and systems needed to perform functions, solve problems and achieve objectives”. Such capacity-building is even more critical in remote areas of developing countries, where inadequate training and education systems, exacerbated by disparities in information access, asymmetric economic and political power, peripherality, and moribund governance, result in low educational attainment and pervasive illiteracy (Gohori and van der Merwe, 2021; Islam et al., 2018). To address capacity deficits, access to reliable information and structured education remains a widely supported strategy for equipping local communities with the skills, knowledge, and technical competencies needed for meaningful participation in planning and development (Buzinde and Caterina-Knorr, 2022). In this regard, academic institutions are expected to take a leading role in providing relevant training, skills development, and research, with Rinaldi et al. (2020) advocating for agile institutions of higher education that are firmly embedded within their communities, leading the co-creation of sustainable development solutions, generating transformational knowledge that is accessible to communities and practitioners through engaged practices and action research. Furthermore, in marginal but tourism-dependent contexts, Weaver et al. (2021) propose incorporating sustainable tourism content into primary and secondary school curricula to foster civic skills and build a foundation for meaningful participation in planning and management. Fariss et al. (2023) strongly emphasize the need for greater investment in capacitating local communities, community-based institutions and their leadership for participation in planning and decision-making in settings typified by low environmental democracy and accountability. While acknowledging that capacitated local community leadership and resilient community institutions lay the foundation for active participation in development planning, Manyena et al. (2013) argue that beyond the formal schooling system, especially in marginal areas of developing countries, NGOs present an important option that can be utilized for capacitating local communities in decision-making due to their ability to connect with traditional leadership, public planning institutions, and their accessibility and capacity to deploy skilled personnel.

Increasingly, scholars highlight community resistance expressed through various forms of organic mobilization and activism as a vital mechanism in nature-based destinations for promoting environmental justice and enhancing local community roles in tourism planning, development, and conservation (Chirozva et al., 2017; Leonard, 2021). Despite definitional ambiguities, Chirozva et al. (2017) describe local community resistance as a potent mechanism through which individuals or communities actively engage in verbal, cognitive, or physical actions to liberate themselves from perceived injustices, external control, and interventions that impact their environment, rights, or livelihoods. Thus far, scholars have identified various formal and informal forms of social and community action that express grievances, including disruptive protest marches, roadblocks, appeals to human rights bodies, and litigation (Leonard, 2021). Resistance to conservation-induced land dispossession has manifested in the Southeastern Lowveld of Zimbabwe in Sengwe and Tshipise communal lands through peasants defiantly cultivating crops within protected areas (Chirozva et al., 2017) and in South Africa's Tsitsikamma National Park's communities documenting dispossession and displacement through a film to garner global attention and solidarity (Armitage et al., 2020). The concerted mobilization of the Amadiba Crisis Committee of Xholobeni on the Eastern Cape Wild Coast against mining on ecologically sensitive and agriculturally vital landscapes (Maphanga et al., 2022) or the Zimbabwe Environmental Law Association (ZELA) acting on behalf of the Hwange District communities to compel the government to revoke the mining license in Hwange National Park (Vuola, 2022) exemplify the strength of communities in asserting their rights to inclusive planning, resource sovereignty, influencing policy, challenging ecologically unjust development, and top-down governance decisions. It also emphasizes the importance of community self-mobilization if they are to gain influence in tourism development planning. Although Poweska (2017) highlights the risks associated with various forms of resistance and activism, including vilification and violent deaths, especially in resource-rich yet developing democracies characterized by semi-militarized institutions, pervasive corruption, and collusion between governments and corporations, Leonard (2021) believes activism should evolve and transform into formidable community organizations that can forge connections with academia, environmental groups, and institutions sharing similar views to create a platform capable of securing better funding, capacity-building, building confidence, and support for legal actions in the pursuit of environmental justice and a meaningful role for local communities in planning.

A climate of trust both within local communities and between these communities and governing authorities is widely recognized in the literature as a critical prerequisite for fostering sustained and meaningful local participation in tourism planning processes (Harilal et al., 2021; Siakwah et al., 2020). Despite its widespread application across the social sciences, trust remains a conceptually elusive construct, with many definitions mainly framed through psychological and sociological lenses that emphasize its inherently relational nature (Silva Dos Santos et al., 2024; Nunkoo, 2017). Among many, Silva Dos Santos et al. (2024, p. 4) define trust from a sociological perspective as “reciprocal faithfulness among actors and systems interacting through embedded social relations and setting”, making it a crucial bonding agent and lifeblood of social relations. Although trust concerns span all destination sectors and stakeholders, the government's central role in sustainable tourism planning and development, policymaking and institutional oversight renders public trust in state tourism institutions subject to persistent scrutiny (Harilal et al., 2021; Nunkoo et al., 2012). In such a context, Nunkoo et al. (2012) suggest that state tourism institutions should thrive on efficient organizational and economic performance, promoting good governance to build trust and secure local support and active participation in planning. Trust among destination stakeholders is particularly critical in developing countries with evolving governance systems, where tourism and conservation initiatives are frequently undermined by entrenched conflicts involving local communities (Harilal et al., 2021). Arguing from a protected area management vantage point, Musakwa et al. (2020) urge investment in robust communication systems and transparent decision-making by public agencies to cultivate trust and a fertile ground for collaborative relationships in planning and management processes.

The devolution of governmental planning, decision-making, and management authority to the lowest levels of governance has emerged strongly in local government and Community-based natural resource management (CBNRM) literature as critical to centring the role of local communities in planning and conservation (Ntuli et al., 2018; Springer et al., 2021). From conservation and natural resources governance scholarship, devolution entails transferring planning and decision-making powers, as well as proprietary rights over natural resources, to local communities to foster autonomy, empowerment, responsive decision-making and the emergence of resilient grassroots institutions (Manyena, 2013; Musakwa et al., 2020). Greater community control and proprietary rights over natural resources, including wildlife, are posited to facilitate sustainable extraction that enhances community welfare, thereby encouraging conservation and fostering more positive attitudes toward wildlife (Chigonda, 2018; Ntuli et al., 2018). Instructively, recent studies, more than anything, attribute the decline of the Communal Areas Management Programme for Indigenous Resources (CAMPFIRE), Zimbabwe's pioneering form of CBNRM, to the failure of Rural District Councils (RDCs) to devolve proprietary authority over wildlife and natural resources management to communities that coexist with and steward wildlife, thereby disincentivising commitment to conservation and related wildlife-based tourism (Dervieux and Belgherbi, 2020; Dube, 2019). Consistent with tourism and natural resource conservation scholarship, proponents of local government devolution (Moyo and Ncube, 2014) argue that vesting greater planning and development authority at the lowest subnational levels in village development committees (VIDCOs) and ward development committees (WADCOs) can build a robust bottom-up planning framework. In such devolved planning models, local community development plans originate at the village level and cascade upward through ward, district, and provincial tiers, thereby addressing the key inefficiencies and systemic pathologies inherent in highly centralized governance systems.

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Study area and context

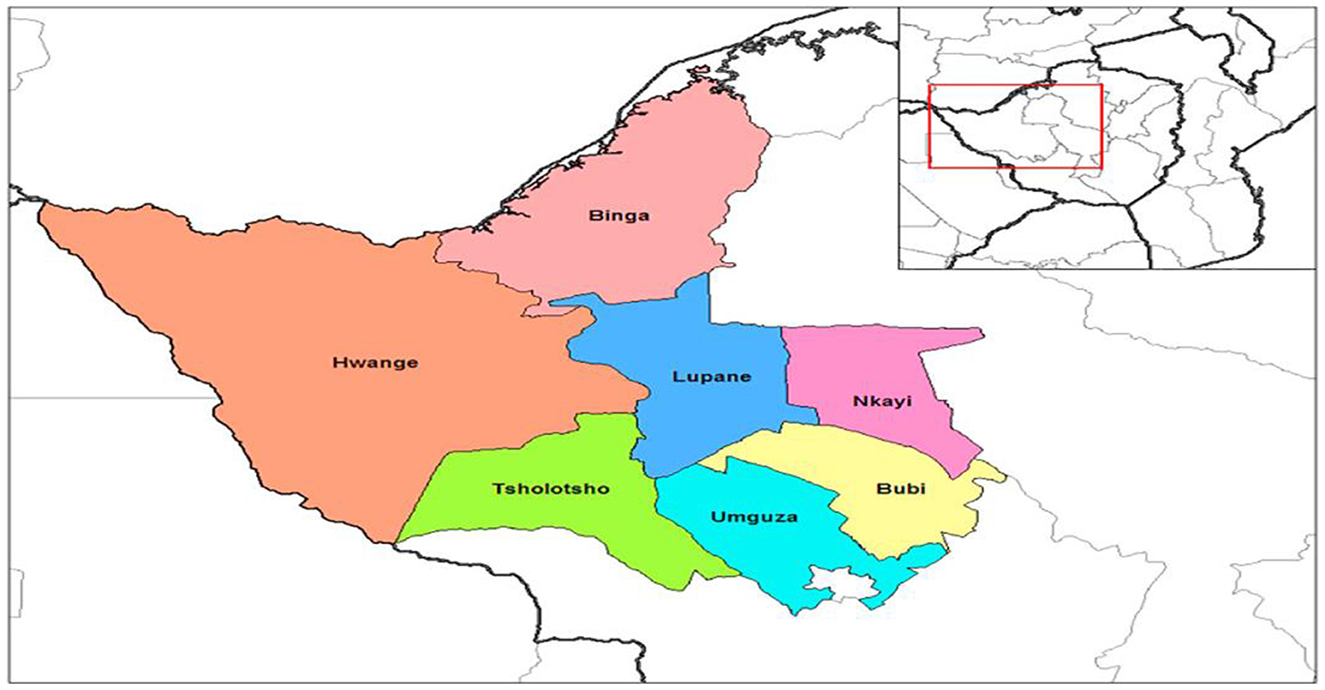

The study was conducted in Hwange District, located in Matabeleland North Province, northwestern Zimbabwe, which is bordered by Tsholotsho, Lupane, and Binga Districts and shares international boundaries with Botswana to the southwest and Zambia to the north (see Figure 2). The district was purposively selected due to its prominent status as Zimbabwe's leading biodiversity conservation hotspot and tourism hub, with its emblematic attractions serving as the main drivers of the country's tourism economy (Dube, 2019; Makuvaza, 2012). It was also deemed a suitable site for the study, as it is located within the KAZA TFCA, which is poised to become one of the world's largest terrestrial conservation and tourism landscapes, with among other goals, the cooperative and sustainable management of natural and cultural heritage to enhance the well-being of local communities (Sagiya, 2020). Currently, the district has an estimated population of approximately 144,813 individuals, comprising 69,357 (47.9%) residents in Hwange Rural, 40,241 (27.8%) in Hwange Town, and 35,215 (24.3%) in the City of Victoria Falls, distributed across 39,608 households [Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency [ZIMSTAT], 2022]. Owing to historical displacements and migrant labor inflows into the mining industry, the district accommodates a diverse array of ethnic groups, including Tonga, Nambya, Ndebele, Chewa, Kalanga, Shona, Nyanja, and Shangwe (Dervieux and Belgherbi, 2020). Coal mining is another pillar of the district's economy, supporting mineral processing, thermal power generation, and the country's manufacturing sector, while significantly contributing to the welfare of thousands through employment (Ruppen et al., 2021). Despite the district's unparalleled natural resource endowments and vast economic potential in the extractive and tourism sectors, the World Food Programme (2022) reported that 76% of the population lives in precarious poverty. Most households, particularly in rural areas, are registered as extremely poor, grappling with unemployment, economic precarity, food and water insecurity, climate variability, infrastructure deficits, limited access to basic healthcare and education, physical and economic displacement, and environmental and land degradation.

Figure 2. Map of districts in Matabeleland North, including the Hwange District (source: Dube, 2019, p. 338).

The district is considered a dryland, characterized by highly variable and unpredictable rainfall patterns, with an average annual precipitation of 550–600 mm and covered by highly infertile Triassic and Kalahari sands with low moisture retention, making it marginal for rain-fed cropping (Guerbois et al., 2012). Despite the punitive semi-arid climate, infertile soils, and high-density free-ranging wildlife, villagers subsist on land-based strategies of crop and livestock husbandry (Mushonga and Matose, 2020). The cultivated staple crops include maize, millet, and sorghum, while some households also keep livestock for subsistence, draft power, asset accumulation, and income supplementation (Perrotton et al., 2017). Due to limited agricultural potential, natural resources continue to be a vital part of rural livelihoods, with local communities relying heavily on harvesting natural resources for sustenance, medicinal purposes, construction, and informal trade (Mushonga and Matose, 2020). In addition, rural communities participate in the CAMPFIRE initiative to varying degrees (Shereni and Saarinen, 2020). Although 18 out of 20 wards within the HRDC officially hold the appropriate status or authority to participate in the CAMPFIRE initiative, Dube (2019) established that only three (Mabale, Silewu, and Sidinda) had viable wildlife populations and collectively generated all dividends, which are distributed across all participating wards. Although the district boasts abundant wildlife resources and a vast network of protected areas, existing studies indicate that the district's CAMPFIRE programme remains suboptimal, failing to achieve the success seen in other provinces with limited natural resources (Dervieux and Belgherbi, 2020; Dube, 2019).

3.2 Data collection and analysis

This study employed a qualitative approach grounded in the interpretivist paradigm to explore the contextual, in-depth, and nuanced perspectives of informants on building the foundation to stimulate and enhance community participation in tourism planning (Gray, 2022). Qualitative approaches are increasingly used in tourism (Nyaupane et al., 2020) to facilitate deeper engagement, uncover socially constructed realities and intricacies of phenomena, address “why” and “how” questions, and give participants a stronger voice on subjects of interest (Tracy, 2020). For this study, we began by reviewing the literature on secondary sources related to local community participation in tourism planning within nature-based tourism destinations, aiming to deepen our conceptual understanding of community participation, generate insights into the enablers, and identify feasible strategies to cultivate and sustain participatory tourism planning. The review utilized secondary sources, including policy documents, local government strategic plans, government gazettes, legislation, books, conference papers, institutional publications, workshop proceedings, project reports, park management plans, and published journal articles.

Following a review of the literature, semi-structured face-to-face interviews were carried out with 22 key informants to collect primary data, each lasting between 40 and 60 min. Qualitative semi-structured interviews are widely used to generate rich, in-depth data, as their flexible design enables probing, allowing respondents to articulate the subjective meanings they associate with a given concept and providing a holistic understanding of the issues (Gray, 2022). We employed non-probability purposive sampling to recruit key informants. Purposeful sampling enabled the researchers to focus on information-rich individuals who possessed relevant and extensive experience and decision-making roles, while also guaranteeing representation from all key sectors and strategic stakeholder groups involved in tourism planning and conservation. This represented senior management and departmental heads from key government agencies operating within the district, including the ZTA, ZPWMA, Department of Immigration Zimbabwe, ZFC, and the Environmental Management Agency (EMA). The selection was guided by the statutory mandates conferred upon state agencies such as the ZPWMA and the ZFC, which are legally designated as planning authorities within the protected area system (Mushonga and Matose, 2020), holding substantial influence over the extent and depth of local community involvement in tourism planning within a district where nature-based tourism, anchored on protected areas, dominates the economic and conservation landscape. A local legislator, representing one of the district's constituencies in the national assembly, was also included for both community and political perspectives on encouraging and sustaining the role of local communities in tourism planning and governance. Six local government officials from the HLB, HRDC, and City of Victoria Falls Council were selected because of their legally mandated roles in resource management, strategic planning, bylaw enactment, and collaboration with sectoral government agencies. This positions them as key players in determining the extent and quality of community involvement in tourism planning.

Two informants were selected from conservation non-governmental organizations (NGOs) with a long history of collaboration with ZPWMA and local communities. In Southern Africa, NGOs play a significant role in promoting biodiversity conservation, tourism activities, engagement of local communities, and strengthening governance institutions, highlighting the importance of their viewpoint in enhancing the participation of local communities in tourism planning (Musakwa et al., 2020). Four informants were also selected from the tourism industry, including two representing the largest concessionaires and tour operators, alongside representatives from the Hospitality Association of Zimbabwe (HAZ) and the Tourism Business Council of Zimbabwe (TBCZ), the sector's most influential industry associations. Two senior traditional leaders (chiefs) were also purposely selected to participate in the study, as their perspectives represent grassroots developmental aspirations. In Zimbabwe, traditional leaders serve as spiritual authorities, custodians of cultural and natural resources, and community representatives, placing them as key intermediaries between their constituencies and development planners at both local and national government levels (Mkodzongi, 2016). Finally, a senior wildlife tourism academic and a development consultant completed the list of key informants, contributing insights into the potential role of academic and research institutions in fostering the sustainable involvement of local communities in tourism planning.

After the interviews were transcribed, a six-phase thematic analysis was conducted, following the approach outlined by Braun and Clarke (2022). The analysis entailed (1) immersive reading and reviewing data for familiarity, (2) generating and sorting initial codes following the identification of relevant data for the research question, (3) identifying patterns to form themes, after isolating common patterns across dataset, (4) reviewing and refining themes for relevance, (5) defining and concisely specifying themes, and (6) compiling the report while integrating typical extracts to support interviewee views (Braun and Clarke, 2022). Throughout the study, research ethics were adhered to, from obtaining permission to conduct the study to addressing informed consent, confidentiality, and upholding participant anonymity (Tracy, 2020). All key informants were asked for their consent before the interviews and were assured that the information generated by the study would be protected and kept confidential. Some informants holding senior roles in government agencies agreed to participate in the study, provided their organizations and portfolios remained anonymous. To preserve anonymity and prevent any connection with their organizations or roles, all study informants were assigned identifiers as respondents 1 through 22. The following sections present the findings of the study.

4 Findings and discussion

4.1 Full implementation of all key participatory legislation and policies

Most participants acknowledged that the country had a basic, yet potentially potent legal and policy framework, which needed unequivocal and full implementation to build a foundation for active local community participation in tourism planning. Over the years, Zimbabwe has promulgated a corpus of participatory legislation and policies that domesticate international law and other progressive instruments. However, many of these laws and policies remain either partially implemented or yet to be fully enforced. The quotation below affirms this assertion:

The challenge lies not in the absence of laws but in political commitment and resolve. Since independence, countless laws, blueprints, treaties, policies, and protocols have been enacted to integrate and empower Indigenous communities in the tourism and wildlife sectors, but many have yet to see the light of day. We must implement and comply with our laws before anything else. (#16).

More than any existing participatory legislative instrument or policy, informants consistently suggested that the full implementation of the country's constitution has the unparalleled potential to unlock a legal and policy framework conducive to the institutionalization of participatory planning, including in tourism. This is evident in the illustrative excerpts below:

The right to participate in planning and development is rooted in the constitution and is intended to remedy economic, social, and political marginalization. Every citizen must be educated and assisted in understanding and invoking laws to claim their rights, and the government and its institutions must comply without reservation. (#4).

The constitution provides for environmental rights and good governance. Local communities now have the right to sustainable development, equitable access to natural resources, and participation in local social and economic development planning and implementation. Efforts must concentrate on the rule of law and building efficient and accountable institutions to enforce our rights. (#16).

This finding aligns with research across diverse contexts, demonstrating that while a country's legal and policy framework has the potential to establish a participatory planning regime, its realization is either hindered by institutional incapacity or outright absence of political will and prioritization at the highest levels of authority (Moyo and Ncube, 2014; Murombo, 2021). Ordinarily, constitutionalising participation is intended to establish an unassailable legal basis for participatory planning, requiring political will, constitutionalism, and the rule of law, as mandated by the supremacy of the country's constitution (Murombo, 2016). Therefore, building a foundation for local community participation in tourism planning should partly rely on the strategic mobilization of political will, concerted advocacy for implementing existing laws and policies, and even the non-confrontational judicial route to extract enforcement injunctions.

4.2 Revitalizing sectoral participatory planning legislation

Most narratives emphasized the urgency of revitalizing sectoral participatory planning and conservation legislation to explicitly mandate participation and reinforce local communities' rights in tourism planning, development, and biodiversity conservation. Most informants identified weak tourism legislation, fragmented legislative and institutional frameworks, and the persistence of outdated colonial-era laws as significant barriers that must be addressed to enable effective community participation in tourism planning. The excerpts exemplify this:

The foundation for effective community participation in tourism planning and development must be the enactment of a modern tourism law that reflects our aspirations and the imperatives of sustainable development. The law must support community participation at all levels and defend the rights of the marginalized. (#20).

The colonial-era laws we continue to cling to are inadequate to legally compel public and private institutions to effectuate community participation in tourism planning. We must revisit our legislation and close the loopholes with prescriptive provisions to support participation in development planning. (#22).

The sentiments above reflect the perception that key legislation governing community participation in tourism planning and conservation must either be amended or repealed and replaced with new legislation that captures the aspirations for local community participation. This finding reaffirms extant studies that have identified the primary legislation influencing tourism planning and heritage conservation inherited at independence, among others, the Forest Act (1949), Parks and Wildlife Act (1975), and National Museums and Monuments Act (1972) as too sectorial, exclusionary and archaic, hindering participatory planning, and the effective governance of natural and cultural resources, requiring revamp (Mhlanga, 2009; Sagiya, 2020). Legislation inherited from the colonial era, characterized by sectoral and top-down planning, not only perpetuates coloniality but also neglects human rights, inclusivity, and collaborative governance that have become critical pillars for effective conservation and sustainable tourism (Manyena, 2013; Sagiya, 2020). Hence, Murombo (2016) argues that revitalizing Zimbabwe's legal framework is long overdue and must target outdated sectoral laws with colonial remnants to align with the constitution and infuse sustainable development and good governance tenets.

4.3 Acknowledging and remedying conservation and tourism development injustices and costs

Most informants acknowledged that Indigenous communities have historically faced disproportionate marginalization and biodiversity conservation injustices, which have strained their relationships with conservation authorities and alienated them from tourism planning. Historic displacements and ongoing injustices, including exclusionary conservation practices and uncompensated losses due to human-wildlife conflict (HWC), were cited as sustaining the conflictual relationship between local communities and conservation agencies, undermining support for conservation and alienating local communities from participating in tourism planning and development. The following excerpt is illustrative:

There cannot be complementary coexistence without reparations. We are treated as trespassers on our ancestral land. We have never been involved in planning and managing these areas (national parks), but we bear the losses of crops and livestock due to wildlife. We face lengthy prison sentences if we defend our property. Our children are overlooked for employment. This must now be used to build a compelling case for equitable involvement in managing these protected areas as compensation and restoration of at least some rights to the natural resources. (#18).

The finding aligns with the documented, deep-rooted adversarial relationship between local communities and state-protected area management agencies, as outlined in the Hwange National Park Management Plan (2016-2026), which stems from the historical injustices associated with the creation of protected areas that serve as paradisiacal tourist bastions. This plan highlights issues, including the absence of a benefit-sharing framework, the exclusion of local communities from park management representation, the lack of community ownership or control over wildlife concessions, and the neglect and inaccessibility of sacred cultural sites, all of which serve as significant sources of conflict between local communities and state conservation agencies (Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority (ZPWMA), 2016). Beyond the legacy of protected area injustices, HWC remains the most severe burden for communities in the district, with widespread reports of livestock depredations, crop destruction, zoonotic disease transmission, and wildlife-related injuries or fatalities (Guerbois et al., 2012; Perrotton et al., 2017). Frustrated by the lack of compensation for HWC losses, local communities resort to preemptive and retaliatory wildlife poaching, sometimes employing lethal measures such as cyanide poisoning to deter wildlife intrusions (Ntuli et al., 2018), which further damages the fragile relationships between communities and protected area authorities, with severe consequences for livelihoods, tourism development, and wildlife conservation (Mushonga and Matose, 2020; Perrotton et al., 2017).

Some informants advocating for the remediation of conservation and tourism development injustices and costs suggested a total departure from the command-and-control approach to collaborative management of protected areas, drawing from regional best practices. For example:

We must draw lessons from South Africa, where, at least in principle, local communities have the right to benefit-sharing and collaborative management of protected areas. The region already possesses best practices in legal, policy, and institutional frameworks for engaging local communities in tourism development planning and collaborative management of protected areas. (#11).

In Southern Africa, South Africa's Land Restitution Programme is widely cited as a progressive model of restitutive justice, enabling Indigenous communities displaced by colonial-era conservation practices to receive compensation or reclaim ancestral lands (Armitage et al., 2020; Thondhlana et al., 2016), with those reclaiming their ancestral lands legally mandated to collaborate with state-protected area agencies, dedicating their reclaimed land to perpetual conservation while securing a foothold in planning and managing the protected areas and their related tourism development activities (Cundill et al., 2017). In addition to collaborative management and benefit-sharing to redress injustices, compensation in HWC management is increasingly prescribed to offset wildlife-induced losses, safeguard local community support, promote positive conservation attitudes, and create conducive conditions for participation in tourism planning and decision-making (Shereni and Saarinen, 2020; Nyaupane et al., 2020). Accordingly, building a foundation for local community participation in the district could draw on some of the best practices in managing community-protected area relationships, including commitment to restorative justice and active mitigation of HWC to foster better relations and create conducive conditions that balance biodiversity conservation and tourism development without harming livelihoods or the role of communities in planning and management processes.

4.4 Addressing communal land tenure security

Secure land tenure for local communities emerged as critical in building a foundation for their participation in biodiversity conservation, tourism planning and development. Most informants revealed that since the colonial land annexations and forced displacements, rural communities remain marginalized, with limited rights over natural resources and little capacity to influence conservation policies and tourism planning. This is illustrated in the following quotations:

Participation cannot be effectively addressed without confronting the issues of land rights and tenure. Without legal entitlement to their land and sufficient legal protection, our communities will remain vulnerable and marginalized from natural resources and lucrative tourism development opportunities. (#17).

Protect land rights to prevent the grabbing of ancestral land without the informed consent of local communities. Planning decisions are imposed because rural communities have no legal land entitlement. The district is the center of the KAZA TFCA, and a significant portion has been designated as a Tourism Development Zone, but how many are aware of or have been consulted about this? (#3).

The above sentiments reflect the impact of precarious land tenure and rights in compromising meaningful local community participation in natural resource management and development planning. Zimbabwe's communal land tenure system, governed by the Communal Lands Act: Chapter 20:04 (1983), limits rural communities to usufructuary land rights, while vesting ownership in the state, which consistently exercises unilateral control over planning, thereby marginalizing communities and exposing them to the risk of development-driven expropriation. In much of the developing world, land insecurity is regarded as the most critical constraint on local community participation in tourism planning, with extensive research demonstrating that the absence of land rights undermines communities‘ legal rights and bargaining power, leaving them dispensable in planning and decision-making (Xu et al., 2019; Zielinski et al., 2020). Addressing this structural deficiency is critical for enabling community leverage in planning and securing a greater foothold in tourism through land leases, benefit-sharing arrangements, and integration into the sector's value chain (Siakwah et al., 2020; Thondhlana and Cundill, 2017). As Zimbabwe concludes its land reform programme, addressing historic dispossessions (Siakwah et al., 2020), equal vigor should be directed toward securing communal land tenure and rights. This will strengthen communities' control over vital tourism assets while increasing their bargaining power with various stakeholders in the planning and development processes.

4.5 Revitalizing and reforming community-based conservation (CAMPFIRE)

The CAMPFIRE programme emerged as another potential pedestal to build the foundation for local community participation in wildlife conservation and tourism planning. Most informants acknowledged that CAMPFIRE has historically been a resilient and grassroots participatory institution with the potential for revival and reform to strengthen the role of local communities in biodiversity conservation, tourism planning, and development. The excerpt supports this:

We must deal with disillusionment and build on CAMPFIRE for a bottom-up approach to capture our voices in the local and national tourism development planning system. We have coal, timber, wildlife, and tourism, which are generating enormous wealth that is being siphoned off to develop other provinces… Without a legally recognized collective voice, we cannot change the narrative and reframe decision-making and planning in the face of hegemonic state power. (#11).

The sentiment above highlights the potential of a more structured grassroots planning system to foster accessible and inclusive decision-making, enabling local communities to articulate their aspirations for conservation and tourism development. This aligns with previous research advocating for CAMPFIRE reform, including legislative support (Siakwah et al., 2020), as well as the further devolution of natural resource authority from Rural District Councils (RDCs) to Ward and Village levels (Ntuli et al., 2018). Similarly, Chigonda (2018) advocates for a paradigm shift toward community-owned conservancies, buttressed by robust legislative and policy frameworks akin to Namibia's model, to enhance communal land tenure security, foster resource autonomy, and empower local communities with substantive control over planning, utilization, and benefit-sharing mechanisms. We argue that remodeling, refining, and entirely devolving the CAMPFIRE as an established institution could build and strengthen the role of local communities in tourism planning, complement the protected area conservation system, facilitate the implementation of the KAZA TFCA, and unlock unparalleled inclusive tourism and equitable benefit-sharing opportunities across the extensive tourism value chain.

4.6 External support and partnerships for participatory tourism planning

Most informants emphasized the importance of securing and maintaining external support and establishing partnerships for participatory planning. Many forms of external support for tourism and conservation in the district, ranging from research, local community education, and capacity building to legal representation and large-scale funding provided by local, national, and international agencies, were cited as evidence of the potential of such approaches to entrenching the role of local communities in tourism planning and development. Examples of some excerpts alluding to this angle include:

NGOs have provided all the cutting-edge innovations and research on HWC mitigation, and tourism would be far more prosperous with such expertise and policy entrepreneurship. We must leverage such partnerships to capacitate local communities to manage natural resources and participate in national parks. (#7).

The World Bank actively supported the Hwange-Sanyati Biological Corridor, mobilizing funding and coordinating multi-state agencies for its implementation. These are well-resourced organizations with a soft spot for conservation and rural development that can provide capacity, financing, and institutional support to integrate local communities into tourism development and conservation. (#8).

The above findings demonstrate the potential of leveraging support and partnerships with stakeholders at all levels to increase local community involvement in tourism planning and development. In their study of Gonarezhou National Park, Zimbabwe, Musakwa et al. (2020) demonstrate that support from the Frankfurt Zoological Society to the ZPWMA led to the formation of a multiple stakeholder partnership, which extended to include local communities. This collaborative framework for protected area management has helped mediate conservation and development conflicts, providing a platform for inclusive planning, policymaking, capacity building, and information sharing, which is key for effective conservation and sustainable tourism development. However, Armitage et al. (2020) caution that partnerships involving local communities must not be mere “tick-box” rituals, but instead promote genuine equality, uphold community rights to access and use natural resources, and increase their decision-making power. For policy and practice, Zimbabwe's protected area management agencies could consider building on partnerships with external entities and structuring them to include local communities as equal collaborative partners, thus leveling the decision-making terrain and leveraging reciprocity, complementarity, and the resources and capacities of all the actors.

4.7 Integrated tourism planning

Integrated tourism planning emerged as another key requirement for coordinated and coherent sectoral policies supporting community participation. Most informants who suggested integrated tourism planning lamented the dominance of a fragmented tourism planning landscape, characterized by several public agencies from different ministries with top-down sectoral mandates, duplicative policies, and a lack of dialogue between local authorities and the various public planning agencies. The illustrative excerpts reflecting support for integrated tourism planning include:

Community participation in tourism planning is beyond the remit of local government and will require a holistic, multi-sectoral approach that cuts across different planning systems. We must reimagine tourism planning to include rural development, education, and agriculture. It must be remembered that the implementation of CAMPFIRE required a strong consortium of NGOs, government agencies, the University of Zimbabwe, and USAID. A similar think tank is required. (#15).

State agencies must lead by example in involving local communities in tourism planning, and we expect the Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority (ZPWMA), as one of the leading authorities, to shift from its archaic exclusionary practices. It is unfathomable that public agencies do not have programmes to involve communities in tourism planning and conservation at this age. (#4).

Local authorities and state departments share trusteeship over natural resources for local communities. Therefore, they must have collective and coordinated tourism policies and programmes and move away from haphazard planning and meaningless conflicts that negate tourism growth and alienate communities. (#9).

An analysis of the above excerpts indicates that informants believe a multi-sectoral and inclusive approach is the most effective way to create conditions conducive to local community participation in tourism planning and development. These findings emphasize the compelling reasons for collaborative and integrated tourism planning, echoing longstanding calls for reform of Zimbabwe's inherited, fragmented planning institutional architecture, which maintains sectoral silos, intersectoral conflicts, and overlooks Indigenous rights, thus limiting local community participation in planning and development (Manyena, 2013; Mhlanga, 2009).

4.8 Information, communication and capacitation of key stakeholders

Establishing robust information and communication systems, coupled with the capacitation of key stakeholders, emerged in most narratives as critical to building and sustaining the active participation of local communities in tourism planning. On the subtheme of communication, most informants expressed frustration with the deficient information and communication from tourism, conservation and local authorities, identifying this as a key driver of mistrust, opacity, and hostile conditions that impede community participation. They emphasized the need for reforms and redesign of information and communication systems, as illustrated in the excerpts:

The planning consultation processes should cover villages where most people reside and be conducted in local languages for people to understand and express their feelings without barriers. All stakeholders need sufficient information and prior notification to prepare adequately for these tourism planning sessions. (#4).

Information about tourism development should be effortlessly accessible to encourage participation in planning and development……. We must be guided by laws to reorient public institutions and instill a culture of communication and transparency, inspiring trust and confidence. It must not take a crisis of the magnitude of the recent mass killings of wildlife to recognize the importance of collectivism in conservation and tourism development. (#6).

Information and communication are our Achilles' heels as a country. A cursory scan of the websites of state departments and local authorities shows the gulf between us and our neighbors. Our tourism planning authorities must be versatile and embrace online technologies to engage with diverse audiences, disseminate information, and gather data irrespective of location. Modern tools, such as interactive websites, can demystify planning and facilitate public input. (#21).

The above accounts highlight various aspects of information and communication, as well as the design of participatory planning, including easily accessible tourism planning information, accessible and diverse planning platforms, a strong cross-sectional communication culture, and the utilization of modern communication technologies, which require attention in establishing a foundation to cultivate and institutionalize local community participation in tourism planning. The critical role of information and communication in building trust, enhancing community awareness, capacity, and willingness to engage in tourism planning is well-established in tourism planning discourse (Gohori and van der Merwe, 2021; Queiros and Mearns, 2018; Tosun, 2006). Emerging scholarship in policy and tourism planning increasingly emphasizes the importance of robust interchange between planning stakeholders and establishing inclusive spaces and dialogic platforms that facilitate prolonged, iterative stakeholder deliberation, and leverage networks as critical for embedding participatory planning processes and informing the design of context-responsive planning frameworks (Huber et al., 2023; Ianniello et al., 2018). Zimbabwe, through the Environmental Management Act: Chapter 20:27 (2002), affirms citizens' right to environmental information and stresses inclusive participation by requiring that all affected and interested parties in development be provided with the rights, skills, and capacity needed to engage effectively and fairly in environmental planning and management. Accordingly, the full implementation of such legislation is critical to building information and communication systems as well as local community capacity for meaningful participation in tourism planning.

On the subtheme of capacitation, most informants identified capacity building of local communities, local government authorities, and state planning agencies in the district as key stakeholders, essential for institutionalizing local community participation in tourism planning. Regarding the local community, most informants emphasized the importance of systematic education and training to develop and improve the technical skills of such communities, preparing them for meaningful participation in tourism policymaking and planning, as illustrated in the excerpts:

Tourism planning is a highly technical field, and our curriculum fails to equip us with the necessary skills and capacity to influence tourism policy. All these mega projects (tourism and conservation) are implemented from the top and have not delivered the mandatory capacity for local communities to participate in decision-making. (#3).

The district must prioritize skills development to support natural resource conservation and tourism development. Communities do not operate at the same level as the state technocrats, and this lack of information and capacity has been exploited to marginalize local voices in tourism development. (#9).

Our findings align with those of Gohori and van der Merwe (2021), who found that insufficient information, education, knowledge, and skills disproportionately hinder local community participation in tourism planning and decision-making in rural Zimbabwe. This remains a significant challenge that requires urgent action if local communities are to participate on equal terms. Capacity deficits are pervasive across the developing world, as evidenced by extensive scholarship, which uncovers the pressing need for tailored and systemic training and education to equip marginalized communities with the requisite information and technical competencies for meaningful participation in tourism planning (Siakwah et al., 2020; Zielinski et al., 2020). Beyond bridging awareness and capacity gaps through formal education and training, scholars (Buzinde and Caterina-Knorr, 2022; Thondhlana et al., 2016) emphasize the centrality of collaborative protected area management, grounded in equitable partnerships between local communities and conservation agencies across planning, management, evaluation, and policymaking as critical for cultivating experiential competencies of local communities that are vital to effective participation in biodiversity conservation, tourism planning and development.

Most informants also suggested that, although local government authorities play a central role in district development planning, they face significant deficits in technical, organizational, political, administrative, and financial capacities. These shortcomings hinder their ability to plan for tourism effectively or involve local communities in participatory processes, as shown in the excerpts below:

Do we have the necessary finances, workforce, and expertise to fulfill the region's tourism planning and development mandate? It boils down to resources. Local government institutions must be capacitated and sufficiently funded to initiate and sustain participatory tourism planning and development. (#7).

The devolution of power to local authorities will allow local communities to participate in development planning. However, this burden shift to local authorities must be well thought out and come with funding, fiscal autonomy, assets, and institutional capacity building. It (community participation) will require new financial architecture and must be explicitly supported by legislation. (#14).