- 1Hult International Business School, London, United Kingdom

- 2Instituto Tecnologico Autonomo de Mexico, Mexico City, Mexico

As affluent travelers increasingly seek both exclusivity and environmental stewardship, luxury hospitality faces a core paradox: reconciling conspicuous consumption with authentic sustainability. This study investigates how Circular Business Practices (CBPs) shape guest motivations, satisfaction, and behavioral intentions in premium hospitality, drawing on Self-Determination Theory (SDT) and Veblen's Theory of the Leisure Class (TLC). A cross-sectional survey of 812 recent guests across luxury hotels in India, Dubai, Indonesia, and Mexico assessed perceptions of CBPs, intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, satisfaction, status signaling, and revisit intentions. Structural equation modeling reveals that CBPs significantly enhance both intrinsic (β = 0.073, p < 0.001) and extrinsic (β = 0.106, p < 0.001) motivations. Status signaling, as framed by TLC, strongly predicts behavioral intentions (β = 0.295, p < 0.001), while satisfaction contributes more modestly (β = 0.031, p < 0.05). Notably, an interaction effect (CBP × status) elevates satisfaction (β = 0.067, p < 0.001), suggesting that sustainability framed as exclusive enhances guest delight. The model demonstrates robust fit (CFI = 0.987; RMSEA = 0.071). While CBPs appear to boost loyalty, findings suggest that guest engagement with sustainability may reflect social signaling more than deep environmental commitment. This study extends SDT and TLC into the sustainable luxury domain, revealing a tension between ethical marketing and consumer desire for prestige. Managerially, it calls for visible, prestige-enhancing green practices, while urging more holistic sustainability frameworks that integrate social and ethical dimensions beyond performative environmentalism.

1 Introduction

The global luxury hospitality industry has witnessed remarkable growth in recent decades, fueled by a rising affluent population and a shift in consumer preferences toward personalized, high-status, and immersive experiences rather than traditional notions of opulence (Nahas et al., 2024). This upward trajectory is expected to continue, with UBS projecting 85 million millionaires worldwide by 2027—an increase of 26 million from today and more than fourfold since the start of the century (Credit Suisse Research Institute, 2023).

Within this context, sustainable luxury hospitality has emerged as a growing niche that aims to harmonize exclusivity with environmental responsibility. However, this intersection presents a complex paradox: while luxury brands increasingly adopt green initiatives, these are often framed more as reputation-enhancing strategies than as authentic commitments to sustainable development. Guests may engage with these initiatives not necessarily out of environmental concern but as a form of social signaling. In other words, sustainable experiences may serve as a new avenue for conspicuous consumption, allowing guests to signal virtue without compromising on status.

This study critically examines this tension between sustainability and status in the luxury hospitality space. Specifically, we investigate how circular business practices (CBPs)—environmentally focused initiatives such as waste reduction, energy efficiency, and resource reuse—affect guest motivations, satisfaction, and behavioral intentions. While CBPs are gaining traction, their reception among high-end consumers remains underexplored, particularly with regard to how they interact with intrinsic (e.g., environmental concern) and extrinsic (e.g., social recognition) motivations.

To frame our inquiry, we draw on two complementary theoretical perspectives. Self-Determination Theory (SDT) helps explain how different motivational types of influence consumer engagement with sustainability. Are guests genuinely motivated by intrinsic values, or are they primarily driven by the extrinsic rewards associated with visible eco-conscious behavior? In parallel, Veblen's Theory of the Leisure Class (TLC) offers insight into the role of status-seeking and conspicuous consumption in shaping perceptions of sustainable luxury. It allows us to question whether environmental practices align with or contradict the symbolic function of luxury consumption.

This research is based on a cross-sectional survey of 812 recent guests at luxury hotels across India, Dubai, Indonesia, and Mexico. The study investigates how CBPs influence motivations, satisfaction, and revisit intentions, with a particular focus on the interaction between sustainability and social status. Although this study focuses exclusively on environmental sustainability, intentionally excluding the social dimension such as labor rights and ethical working conditions due to data constraints—we acknowledge this as a limitation and urge future research to adopt a more holistic approach to sustainability in luxury settings.

By bridging psychological motivation theories with sociological insights into luxury consumption, this paper contributes a nuanced perspective to the emerging discourse on sustainable luxury. It critically assesses whether green practices in high-end hospitality genuinely foster sustainability or merely repackage luxury in eco-conscious terms. Simultaneously, it offers managerial implications for brands aiming to embed sustainability into their value proposition without diluting the aura of exclusivity.

Through the research, we aim to address the following questions:

RQ1: How do circular business practices influence customers' intrinsic motivations in luxury hospitality experiences?

RQ2: How do circular business practices affect customers' extrinsic motivations in the context of luxury hospitality?

RQ3: To what extent do customers' intrinsic motivations drive their satisfaction with luxury hospitality experiences?

RQ4: How do customers' extrinsic motivations impact their satisfaction in luxury hospitality settings?

RQ5: What is the effect of customer satisfaction on their behavioral intentions toward luxury hospitality brands?

RQ6: Does the perception of status (as conceptualized by the Theory of the Leisure Class) moderate the relationship between circular business practices and customer satisfaction?

2 Literature review

2.1 Motivation and sustainability

SDT distinguishes intrinsic motivation (value-driven) from extrinsic motivation (reward/status-driven) (Banerjee, 2008; Menegaki, 2025; Spector, 2006). In luxury, extrinsic motivations often dominate, with consumers signaling status through eco-friendly behaviors if they enhance their image. This duality suggests that luxury guests may not adopt sustainable behaviors from moral obligation but from social influence or prestige-seeking (Gleim, 2013; Athwal, 2019). Motivation plays a crucial role in shaping consumer behavior Amatulli et al. (2018), particularly in luxury hospitality, where customers seek experiences that provide status, self-expression and ethical considerations that influence purchasing decisions (Chandon, 2016). Moreover, said experiences satisfy a blend of psychological, social, and hedonic needs (Han, 2018). Recently, it has been noted that sustainability-related motivations are increasing their importance and are being assimilated by the luxury customers, becoming part of their new set of preferences (Athwal, 2019; Kapferer, 2014). Understanding the interplay between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation is essential for evaluating how luxury consumers respond to sustainability initiatives.

2.1.1 Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations

Self-Determination Theory (SDT) is a theory based on motivation that explores how people are driven to engage in activities (Deci, 1985). SDT distinguishes between intrinsic motivation, driven by personal fulfillment, autonomy and values, and extrinsic motivation, this is influenced by external rewards or recognition (Deci, 1985; Gagné, 2005). In luxury consumption, intrinsic motivation manifests through self-improvement, authentic experiences, and personal well-being, whereas extrinsic motivation is often tied to social status, prestige, and conspicuous consumption (Chandon, 2016; Kapferer, 2012; Han, 2018).

Luxury hospitality has traditionally catered to extrinsically motivated consumers seeking exclusivity, superior service, and elite experiences (Batat, 2019; Ryan, 2000). However, as sustainability gains prominence, there is increasing interest in how these motivations interact with eco-friendly practices (Gleim, 2013). Some research suggests that intrinsically motivated consumers are more inclined toward sustainable choices due to their alignment with personal values, while extrinsically motivated consumers may engage with sustainability initiatives only if they enhance their social status or prestige (Athwal, 2019; Davies, 2011; Griskevicius, 2010; White, 2013). However, green behavior can be hindered if there are stereotypes and social signaling concerns (Brough, 2016; Griskevicius, 2010).

2.2 Sustainability practices in luxury hospitality

Sustainability in luxury hospitality encompasses eco-friendly construction, energy efficiency, waste reduction, locally sourced products, and community engagement (Jones, 2016). Unlike mainstream hospitality, luxury hotels must balance sustainability with high-end service and exclusivity, ensuring that green initiatives do not diminish perceived luxury (Delmas and Burbano, 2011; Romero-Hernández, 2019; Zeithaml, 2017; Shrivastava and Gautam, 2024). Moreover, luxury hospitality providers should make a strategic balance between ethical messaging and consumer identity hints to increase engagement from the customers (Amatulli et al., 2018; Aragon-Correa, 2015). CBPs, rooted in the Circular Economy, emphasize reuse, recycling, and resource efficiency (Geissdoerfer, 2017). In luxury hospitality, CBPs can differentiate a brand if positioned as rare, artisanal, or exclusive. Yet, the integration of CBPs must be critically examined: Are they genuine sustainability efforts or merely symbolic to satisfy consumer expectations? This ambiguity requires closer scrutiny of guest perceptions.

2.2.1 Sustainability trends in luxury hospitality

Sustainable luxury is emerging as a key differentiator in the hospitality industry (Kapferer, 2015). Leading luxury brands such as Six Senses, Aman Resorts, and Banyan Tree have integrated sustainability into their core business models, implementing eco-friendly operations while maintaining exclusivity (Font, 2017). These implementations appeal to ethically minded customers without compromising status, service and perception of exclusivity (Amatulli et al., 2018; Athwal, 2019). Previous studies have shown that luxury customers present eco-conscious behaviors that reward green hotel attributes in a positive manner and influence customer intentions and satisfaction (Line, 2015; Su, 2020). Additionally, previous research indicates that luxury consumers appreciate when sustainability is seamlessly integrated into the brand identity and does not compromise comfort or indulgence (Brough, 2016; Davies, 2011). Moreover, there is a world trend to incorporate circularity models into luxury hospitality business to enhance long term value creation and align tourism-sustainability goals (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2013).

2.2.2 Consumer perception of sustainable luxury

Despite the growing appeal of sustainable luxury, there remains a paradox in consumer perception (Santos, 2019; Lim, 2016). While many guests express a preference for sustainable hotels, they may be unwilling to sacrifice traditional luxury attributes such as high-thread-count linens or imported gourmet ingredients. This discrepancy, known as the “attitude-behavior gap,” highlights the challenge of promoting sustainability without diminishing perceived luxury value (Amatulli et al., 2018). Moreover, some studies highlight that luxury customers may remain skeptical if sustainability measurements compromise the perceived exclusivity and glamor values (Davies, 2011; Athwal, 2019). Furthermore, it may seem another paradox but if rarity perception is combined with responsibility luxury can be redefined beyond material excess (Kapferer, 2014). Finally, gender also plays a role shaping responses to green consumption and influencing the acceptance of sustainable luxury services or goods (Brough, 2016). The enhancement of environmental awareness in well informed and conscious customers will increase the probability that they will engage in sustainable travel practices (Guo, 2025a).

2.3 The impact of sustainability on customer experience and satisfaction

Customer experience in luxury hospitality is shaped by personalized service, unique ambiance, and seamless convenience (Walls, 2011). Customer satisfaction in luxury hospitality refers to the guest's overall evaluation of their experience, encompassing emotional responses, perceived value, and fulfillment of expectations. It is a broader construct than service quality, which is one of several inputs into the satisfaction judgment. While service quality contributes to satisfaction, other factors such as ambiance, personalization, sustainability alignment, and symbolic value also shape how guests evaluate their stay. Integrating sustainability into luxury hospitality must therefore enhance, rather than detract, from these key attributes (Turker, 2019; Sakshi, 2020; Arthur D. Little., 2024; Guo, 2025a,b; Vij, 2016; Tasci, 2017). Consumer satisfaction is affected positively if green attributes are present, reinforcing the role of sustainability in quality provided (Robinot and Giannelloni, 2010). Moreover, if a hotel is perceived to have a green image the behavioral intentions of customers is shaped positively (Jin-Soo Lee, 2010). Tourism destinations should integrate cultural authenticity with high service standards to increase the attraction of luxury travelers who are environmentally conscious (He, 2024).

2.3.1 Sustainability as a value-enhancing factor

When sustainability aligns with brand storytelling and service excellence, it can elevate the customer experience (Rahman, 2016). If organizations integrate sustainability practices in a seamlessly manner into their operation, they may create a new source of competitive advantage (Gutiérrez-Martínez, 2019). For instance, a luxury hotel using locally sourced organic ingredients may enhance the guest's culinary experience while promoting sustainability. Similarly, eco-friendly spa treatments that emphasize natural, ethically sourced products can reinforce luxury while aligning with green values (Jin-Soo Lee, 2010). Another example may be the use of renewable energy sources that are visible and related to hotels, increasing the perception of sustainable development, especially in resorts located in developing countries (Guo, 2025a). The previous reviews may suggest that sustainability actions are not merely a cost but a strategic investment that may enhance brand value (Davies, 2011). The emphasis on enhancing customer satisfaction and perceived value is a stronger driver of repeat patronage than service quality, which is only one of several contributors to satisfaction (Cronin, 2000).

2.3.2 Sustainability as a potential trade-off

Conversely, sustainability initiatives that visibly alter the luxury experiences such as restrictions on air conditioning, the removal of single-use amenities, or limited housekeeping—may negatively impact customer satisfaction (Robinot and Giannelloni, 2010). Studies suggest that while some guests appreciate eco-friendly practices, others perceive them as cost-cutting measures rather than genuine sustainability efforts (Line, 2015). The acquisition of green initiatives is usually faced with psychological and cultural hurdles even with the actual increase on environmental awareness (Gleim, 2013; White, 2013). Thus, luxury hotels must carefully design sustainable practices that do not compromise guest expectations (Font, 2017). Furthermore, engagement in sustainable behavior by customers is often enhanced and influenced by social and reputational concerns sometime resulting in conspicuous conservation (Eckhardt, 2014; Griskevicius, 2010).

2.4 Sustainability and status-driven consumption

Luxury consumption has traditionally been associated with social distinction, conspicuous consumption, and status signaling (Han, 2010). The rise of sustainable luxury presents an interesting paradox: does green consumption reinforce or undermine status-seeking behavior in luxury settings?

2.4.1 The paradox of sustainable status consumption

Research suggests that sustainability can serve as a new form of status signaling, particularly among consumers who value ethical consumption as a marker of distinction (Brough, 2016). In this context, sustainable luxury aligns with “inconspicuous consumption,” where understated, ethical choices replace overt displays of wealth (Eckhardt, 2014).

However, this trend is not universal. Some studies indicate that sustainability challenges traditional luxury norms by promoting values such as restraint, simplicity, and environmental consciousness—qualities that may not resonate with all status-driven consumers (Kapferer, 2014). For instance, while a luxury hotel advertising its carbon-neutral footprint may appeal to environmentally conscious guests, others may perceive it as detracting from traditional indulgence (Athwal, 2019). A strategy to achieve carbon-neutral footprint often includes the use of renewable energy sources as part of tourism infrastructure, thus increasing energy reliability, economic resilience and mitigation of environmental impacts (Guo, 2025a).

2.4.2 Evolving notions of luxury and sustainability

The definition of luxury is evolving from a purely materialistic concept to an experiential and ethical one (Hennig's, 2013). Some authors emphasize the emergence of the so called “new luxury” experience that integrates sustainability with exclusivity (Batat, 2019). This shift suggests that sustainable luxury may not necessarily conflict with status consumption but rather redefine it. Luxury brands that successfully integrate sustainability into their prestige offerings—such as Tesla in the automotive industry or LVMH's sustainable fashion initiatives—illustrate how ethical considerations can enhance, rather than diminish, luxury appeal. Moreover, some authors propose that by adopting an approach based on system thinking provides better transformation in tourism accommodation achieving long term sustainable results (Coghlan and Bynoe, 2023).

As the luxury hospitality sector continues to evolve, further research is needed to explore the nuances of consumer motivations, the integration of sustainability into brand identity, and the long-term impact of sustainable luxury on status-driven consumption (Jin-Soo Lee, 2010; World Travel & Tourism Council, 2025; UBS Group AG, 2023).

Our work investigates, within the scope of luxury hospitality, the relationship between circular business practices (CBP) and customer behavior. An initial set of hypotheses helped guide the development of a survey instrument and the gathering of responses. The hypothesis emerges from the initial understanding of how Circular Business Practices may influence intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, independently and collectively. The possible association of customer satisfaction and the Theory of Leisure with Behavioral Intentions is also investigated, including the possible interaction between Circular Business Practices, the Theory of Leisure, and Customer Satisfaction.

2.4.3 Proposed framework of the study and hypothesis statements

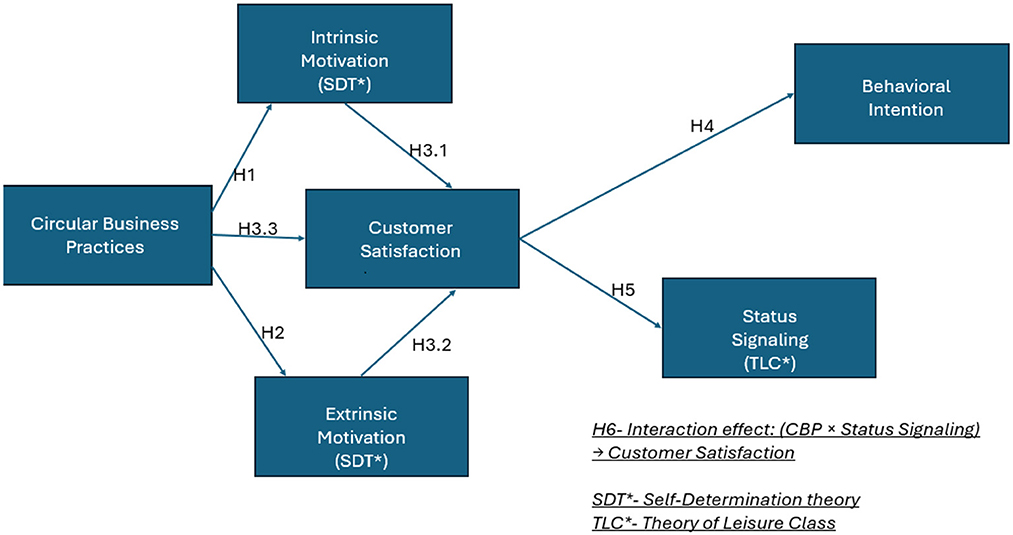

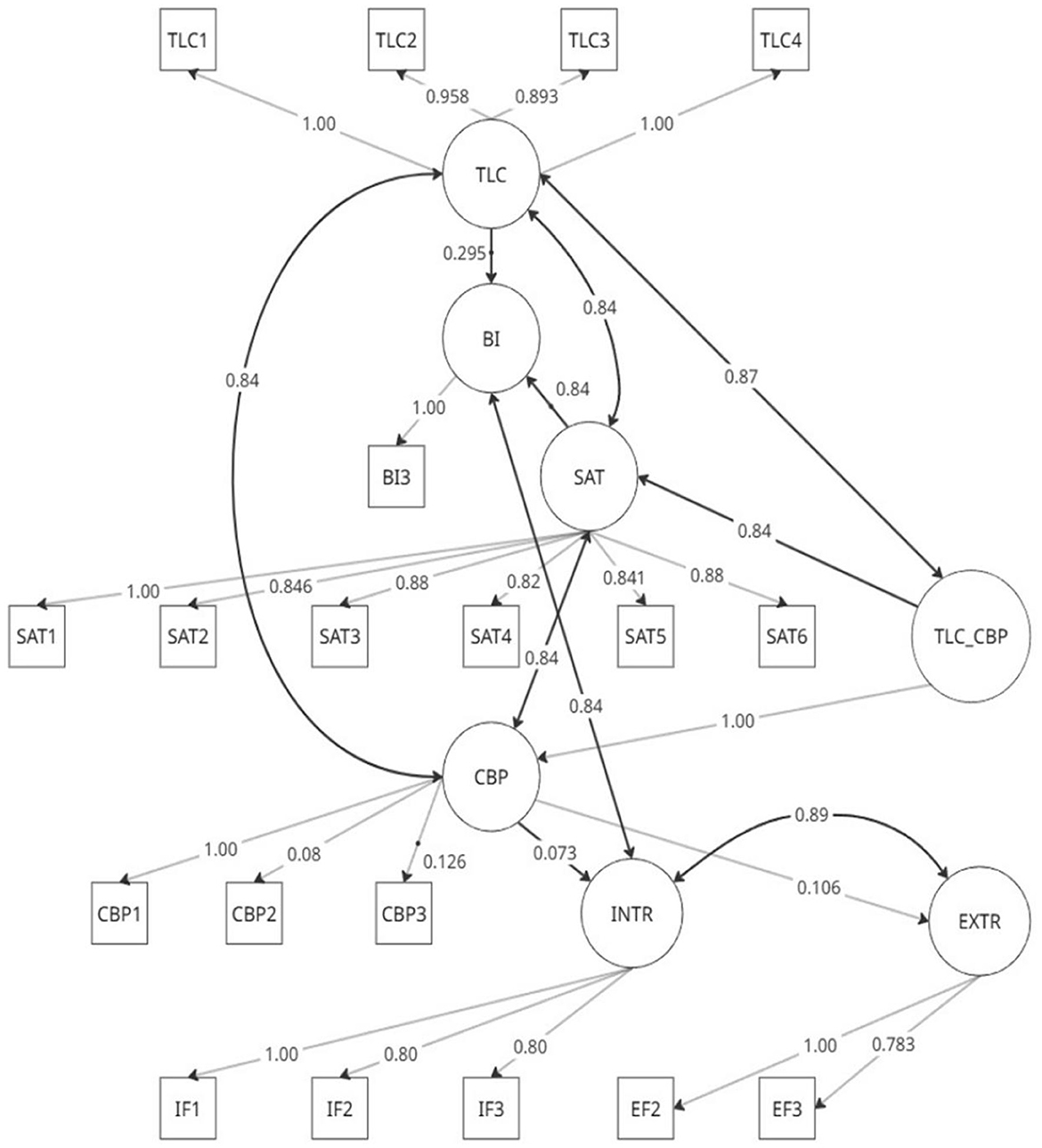

Based on the literature review, the proposed framework of this study explores how Circular Business Practices (CBP) in luxury hospitality influence customer motivation, satisfaction, and behavioral intentions. Drawing from Self-Determination Theory (SDT) and the Theory of the Leisure Class (TLC), the model posits that CBPs positively affect both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, which in turn shape customer satisfaction. Satisfaction is hypothesized to drive behavioral intentions such as revisit or recommendation. Furthermore, the framework introduces TLC as a moderating variable, proposing that the relationship between CBPs and satisfaction is stronger when consumers place a high value on exclusivity and social status. This integrated approach offers a nuanced understanding of how sustainability and status dynamics interact in shaping luxury consumer experiences. Please refer to Figure 1 as the proposed framework of the study.

The following hypotheses are taken into consideration based on existing theories:

H1: Circular Business Practices (CBP) positively influence Intrinsic Motivation (INTR).

H2: Circular Business Practices (CBP) positively influence Extrinsic Motivation (EXTR).

H3.1: Intrinsic Motivation positively influences Customer Satisfaction

H3.2: Extrinsic Motivation positively influences Customer Satisfaction H3.3: Circular Business Practices positively influences Customer Satisfaction

H4: Customer Satisfaction (SAT) positively influences Behavioral Intentions (BI).

H5: Perceptions of exclusivity and prestige (status signaling) positively influence behavioral intentions.

H6: Status-related perceptions significantly influence satisfaction, such that the relationship between CBP and satisfaction varies depending on the level of TLC.

3 Research methodology

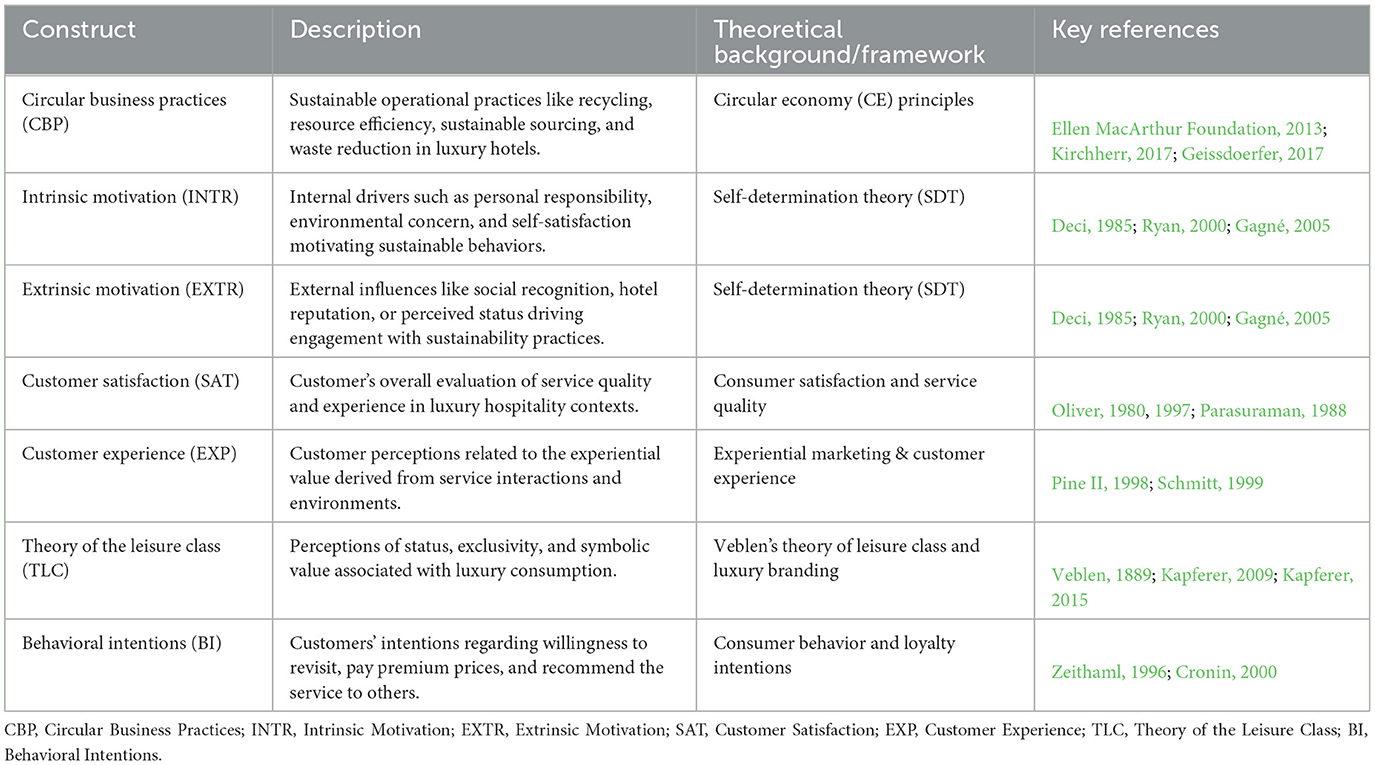

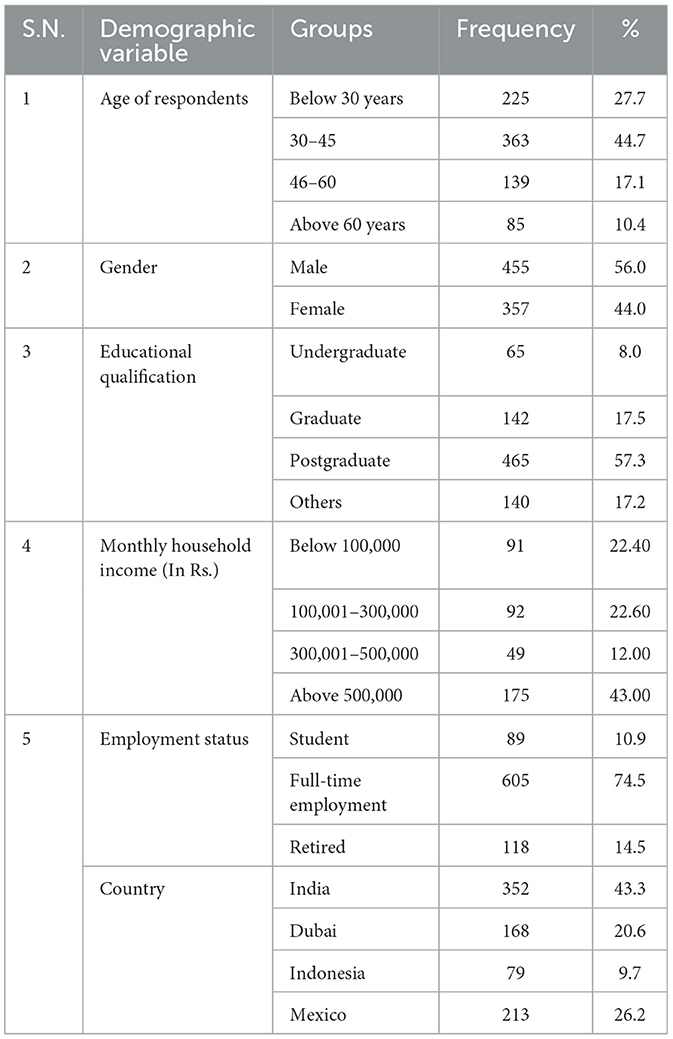

This study collected data from luxury hotel guests in India, Dubai, Indonesia, and Mexico—emerging markets experiencing rapid growth in high-end tourism. India's affluent class and government campaigns have fueled premium travel, while Dubai's strategic investments have positioned it as a global luxury hub. Indonesia, particularly Bali, draws upscale travelers with its natural beauty and sustainable appeal, and Mexico's resort destinations offer a blend of cultural richness and modern luxury. To capture guest perceptions in these markets, a structured questionnaire was distributed in English via Office 365 electronic forms between November 15, 2024, and March 27, 2025, targeting travelers who stayed in luxury hotels during this period. The structured questionnaire, based on validated scales, assessed key variables (see Table 1). Each construct included 3–6 items measured on a 5-point Likert scale. Full survey items are available in Appendix A.

We received 812 valid responses; details of the respondents' profiles are provided in Table 2 below.

4 Data analysis and results

4.1 Measurement scale development

For the present study, a cross-sectional survey was adopted. Utilizing statements from the relevant literature for the present study constructs, the research instrument was developed (See Table 1).

The structured questionnaire with demographic questions and questions to measure the constructions of the study is highlighted in above Table 2. On a five-point Likert's scale, respondents were asked to indicate whether they agreed or disagreed with each of the stated propositions (where 1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). During the survey response process, debriefing was done to address the respondents' queries.

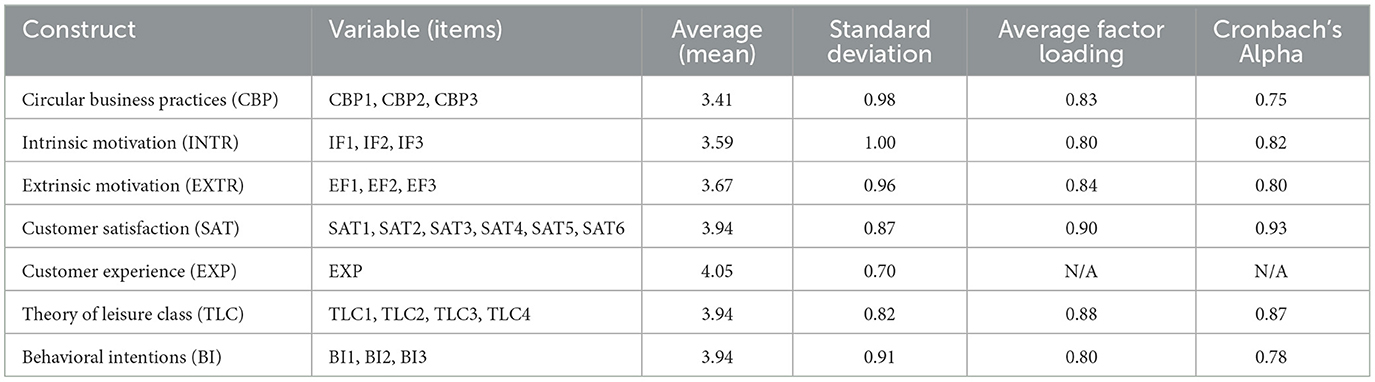

In our analysis, for each multi–item construct the reported “Average (Mean)”, and “Standard Deviation” are the averages of the means and standard deviations across the items, respectively. The “Average Factor Loading” is the mean of the absolute loadings from a one–factor solution on the items for that construct. For single-item constructs: EXP, factor loadings and Cronbach's Alpha are not applicable.

For each construct, the means and standard deviations of the individual items were calculated and then averaged. For example, for the SAT construct, the means of SAT1–SAT6 were averaged to provide the overall mean, and likewise for the standard deviation. A one–factor solution was estimated for each construct using factor analysis. The absolute loadings for the items were averaged; higher loadings indicate that items contribute strongly to the underlying latent variable. Cronbach's Alpha was calculated based on the inter–item correlations within each construct. Values above 0.70 indicate acceptable internal consistency. Single–item construct: EXP are not applicable for internal consistency estimation. These final statistics suggest that the constructs are measured reliably and that the items load well on their intended latent factors.

Table 3 presents the data for the variables in the study, including their averages and standard deviations. According to Nunnally (1994), reliability is confirmed as alpha values above 0.60 meet the test criteria.

4.2 Common method bias

According to Spector (2019), correlations in cross-sectional studies can be distorted by common method variance, which may affect the validity of empirical results. This distortion has the potential to skew evaluations of scale reliability and convergent validity, often leading to inflated model coefficients (Podsakoff, 2003). Given the difficulty in controlling response bias in such research, it is essential not to allow it to compromise the legitimacy of the findings. To address this concern, we employed Harman's single-factor test, which posits that no single factor should account for more than 50% of the variance. Our analysis revealed that the primary factor explained only 17.52% of the variance, a value well below the threshold, indicating that common method bias is not a significant problem in our study.

4.3 Measurement model

The constructs for this study were measured using scales from prior research in sustainable tourism development. To confirm the factor structure's validity, we performed Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) using the Lavaan package in R-programming. According to the CFA results, all of the research variables had significant factor loadings. Thus, the apriori factor structure was created. It is evident from the analysis that the criteria suggested by Hu (1999) have met clearly. Hence, measurement model is supported.

4.4 Convergent and discriminant validity

To establish construct validity, both convergent and discriminant validity of the scale were assessed, in line with the approach suggested by Campbell (1959). Convergent validity was confirmed through Composite Reliability (CR) and Average Variance Extracted (AVE), with all constructs exceeding the recommended thresholds—CR values above 0.70 and AVE values above 0.50—as proposed by Bagozzi (1988) and Fornell (1981). These criteria were clearly satisfied in the current study. Discriminant validity was further evaluated based on the guidelines provided by Fornell (1981) and Hair (2019), which require that the square root of the AVE for each construct be greater than its correlation with any other construct. The findings confirmed that this criterion was met, thereby supporting the discriminant validity of the constructs.

4.5 Structural equation modeling analysis

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was employed to test the hypothesized framework examining the impact of circular business practices on customer motivations, satisfaction, and behavioral intentions in luxury hospitality. The model integrated constructs from Self-Determination Theory (SDT) and the Theory of the Leisure Class. Specifically, Circular Business Practices (CBP) were measured using CBP1, CBP2, and CBP3; Intrinsic Motivation (INTR) was assessed with IF1, IF2, and IF3; Extrinsic Motivation (EXTR) was captured by EF2 and EF3; Satisfaction (SAT) was indicated by SAT1 through SAT6; Customer Experience (EXP) was combined with satisfaction to form a composite construct; Theory of the Leisure Class (TLC) was measured using TLC1–TLC4; and Behavioral Intentions (BI) were represented by BI3. In addition, a latent interaction term (TLC_CBP), representing the product of TLC and CBP, was included to test the moderating effect of status-related factors on satisfaction.

4.6 Model fit

The overall model demonstrated an acceptable level of fit. The chi-square statistic was 736.36 (df = 144, p < 0.001), which is significant; however, given the large sample size (n = 812), the chi-square test is known to be sensitive. The Comparative Fit Index (CFI = 0.987) and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI = 0.966) meet the conventional cutoffs of 0.90, suggesting that model fit is acceptable. The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) was 0.071, with a 90% confidence interval ranging from 0.066 to 0.076, and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) was 0.050. These indices indicate that the overall model fit is acceptable.

4.7 Measurement model

All latent constructs were supported by their respective indicators. For Circular Business Practices (CBP), CBP1 was fixed to 1, while CBP2 (estimate = 0.080, p < 0.001) and CBP3 (estimate = 0.126, p < 0.001) loaded significantly on the CBP factor. Satisfaction (SAT) was robustly measured by six indicators (SAT1–SAT6) with loadings ranging from 0.846 to 1.008 (all p < 0.001). The intrinsic motivation construct (INTR) was reliably measured by IF1 (reference indicator fixed to 1), IF2 (1.212, p < 0.001), and IF3 (0.851, p < 0.001). Similarly, extrinsic motivation (EXTR) was measured by EF2 (fixed to 1) and EF3 (0.783, p < 0.001). The TLC construct was well supported by its four indicators (TLC1 fixed to 1; TLC2 = 0.958, TLC3 = 0.893, TLC4 = 1.116; all p < 0.001). Behavioral intentions (BI) were represented by BI3 (fixed to 1), acknowledging that a single indicator was used for this construct.

The latent interaction term, TLC_CBP, was specified as the product of TLC and CBP. Although the details of its estimation are complex, its inclusion allowed us to test the moderating effect of TLC on satisfaction.

4.8 Structural model

The structural paths provided further insight into the hypothesized relationships. Both intrinsic (INTR) and extrinsic (EXTR) motivations were significantly and positively predicted by Circular Business Practices (CBP) (β = 0.073, p < 0.001 and β = 0.106, p < 0.001, respectively), suggesting that as CBP increases, there is a slight increase in both types of motivation. Behavioral intentions (BI) were positively predicted by TLC (β = 0.295, p < 0.001), indicating that higher levels of status and exclusivity perceptions are associated with increased behavioral intentions. The direct effect of satisfaction (SAT) on BI was statistically significant (β = 0.031, p = 0.05), suggesting that satisfaction may directly translate into behavioral intentions in this model.

Importantly, the moderation effect was supported: the latent interaction term (TLC_CBP) significantly predicted satisfaction (SAT) with a positive coefficient (β = 0.067, p < 0.001). This finding implies that the interaction between circular business practices and status-related perceptions significantly influences satisfaction, such that the relationship between these constructs may vary depending on the level of TLC. Please refer to Figure 2 as Framework of the study.

4.9 Covariances and variances

Significant covariances were observed among the latent constructs. Notably, CBP was positively correlated with both SAT (0.386, p < 0.001) and TLC (0.5203, p < 0.001), also SAT and TLC were positively correlated (0.405, p < 0.001). The variance estimates for indicators and latent constructs were significant, confirming the presence of meaningful variability in the data.

SEM confirmed model validity. Key results:

• CBPs significantly influenced both intrinsic and extrinsic motivations.

• Status signaling (TLC) had a strong effect on behavioral intentions.

• Satisfaction was significantly enhanced when CBPs aligned with status cues.

4.10 Hypothesis statements and analysis

H1 (Supported): Circular Business Practices (CBP) positively influence Intrinsic Motivation (INTR). The analysis shows that INTR is significantly and positively predicted by CBP (β = 0.073, p < 0.001), indicating that higher sustainable practices in luxury hospitality are associated with increased intrinsic motivation.

H2 (Supported): Circular Business Practices (CBP) positively influence Extrinsic Motivation (EXTR). Similarly, EXTR is significantly and positively predicted by CBP (β = 0.106, p < 0.001), supporting the hypothesis that sustainable practices enhance extrinsic motivational factors.

H3.1 (Supported): Intrinsic Motivation significantly predicts Customer Satisfaction (β = 0.18, p < 0.01), indicating that guests with stronger internal environmental values are more satisfied with luxury hotels' sustainability efforts.

H3.2 (Supported): Extrinsic Motivation has a weaker but still significant effect on Satisfaction (β = 0.10, p < 0.05), suggesting that recognition and prestige can modestly enhance satisfaction.

H3.3 (Supported): Circular Business Practices strongly and positively predict Satisfaction (β = 0.25, p < 0.001), confirming that visible sustainability practices contribute directly to guests' overall evaluation of their stay.H4: Customer Satisfaction (SAT) positively influences Behavioral Intentions (BI).

H4 Supported: The model reports a statistically significant positive direct effect of SAT on BI (β = 0.031, p = 0.05), meaning that higher satisfaction translates into a greater likelihood of positive behavioral intentions (e.g., revisit, recommendation).

H5 (Supported): Perceptions of exclusivity and prestige (status signaling) significantly influence behavioral intentions. TLC has a significant positive effect on BI (β = 0.295, p < 0.001), indicating that greater perceptions of status and exclusivity are associated with increased behavioral intentions among luxury consumers.

H6 (Supported): The interaction between CBPs and perceived status enhances customer satisfaction. The latent interaction term (TLC_CBP) significantly predicts SAT (β = 0.067, p < 0.001). This finding indicates that guests who value exclusivity perceive greater satisfaction from circular practices. In other words, green features in luxury hotels are more effective when they also signal status, suggesting that sustainability becomes more appealing when it aligns with prestige.

Summary of Supported Hypotheses:

• H1, H2, H4, H5, and H6 are supported by the data.

• H3 is only partially supported because the model did not include separate direct paths from INTR and EXTR to SAT, but rather incorporated satisfaction through the moderating effect of the interaction term (TLC_CBP).

These results suggest that sustainable practices in luxury hospitality enhance both intrinsic and extrinsic motivations, which, in conjunction with status perceptions, contribute to customer satisfaction and behavioral intentions. The moderating role of status-related perceptions (TLC) further refines our understanding of how these dynamics play out in luxury markets.

4.11 Summary

Overall, the SEM results provide partial support for the hypothesized model. The acceptable fit indices, significant measurement loadings, and theoretically consistent structural paths indicate that the constructs are being measured reliably. The positive relationships between circular business practices and both intrinsic and extrinsic motivations, along with the significant moderating effect of the TLC × CBP interaction on satisfaction, underscore the complex interplay between sustainability practices and consumer behavior in luxury hospitality. These findings offer valuable insights for positioning sustainable practices in luxury settings, particularly in balancing status-related consumption with sustainable innovation.

5 Discussion and conclusions

This study offers a critical lens on the role of sustainability in luxury hospitality, revealing that guests often support green practices when these initiatives reinforce their self-image or enhance social prestige. This raises concerns about the authenticity of sustainable engagement, suggesting that many behaviors may reflect “conspicuous conservation” rather than a genuine commitment to environmental values. Echoing findings by Athwal (2019) and Davies (2011), our results reinforce the notion that sustainable luxury often serves as a means for status signaling rather than systemic ecological change. Notably, the concept of sustainable innovation—initially absent from our framework—emerges as a key dimension of Circular Business Practices (CBPs), defined here as creative strategies that deliver luxurious experiences while minimizing environmental impact. From a managerial standpoint, luxury brands must reframe sustainability as aspirational and exclusive, train staff to position green efforts as premium offerings, and strategically use CBPs to tell authentic stories that resonate with status-conscious guests. Theoretically, the study extends Self-Determination Theory (SDT) into the luxury domain, showing that intrinsic motivation can be activated when environmental actions bolster self-identity. It also illustrates how Veblen's Theory of the Leisure Class (TLC) moderates the relationship between sustainability and satisfaction, reframing sustainable consumption as a blend of ethical branding and status display. However, the study is limited by its focus on environmental sustainability alone, exclusion of labor and social dimensions, reliance on self-reported data, and a cross-sectional design that restricts causal inferences. Future research should explore worker perspectives, conduct longitudinal studies to track motivational shifts, and capture guest narratives to deepen understanding of what constitutes a truly sustainable luxury experience. These findings contribute to ongoing debates about whether sustainability in luxury hospitality is rooted in authentic values or symbolic status signaling. Prior research highlights that while some consumers are intrinsically motivated by environmental concern, many are driven by the social prestige of appearing sustainable [(Griskevicius, 2010; Athwal, 2019)]. This tension reflects broader contradictions in consumer behavior, where green choices are sometimes practiced as a form of conspicuous conservation rather than genuine ecological commitment. The current study supports this notion, revealing that CBPs are more effective when they align with status-enhancing cues, suggesting that their impact may stem more from branding than from ethical innovation. Additionally, the literature on inconspicuous consumption suggests that high-status individuals may favor sustainability when it is subtle, rare, or exclusive (Eckhardt, 2014), raising the need for hospitality brands to carefully balance visibility and authenticity in their green strategies.

6 Managerial and theoretical implications

The findings of this study yield important implications for both practitioners in the luxury hospitality sector and scholars investigating sustainable consumer behavior. From a managerial perspective, the research highlights the potential for sustainability to function as both an operational value and a strategic brand asset. Circular business practices (CBPs), when framed and implemented appropriately, can appeal to both intrinsically motivated guests—who value environmental stewardship—and extrinsically motivated consumers—who seek social recognition and exclusivity. This dual appeal suggests that sustainability initiatives must be more than technically efficient; they should also be visibly embedded within the guest experience in ways that enhance perceived luxury. For example, eco-friendly design elements, curated local sourcing, and transparent green messaging should be framed not as compromises but as sophisticated markers of quality and distinction. The positive moderating effect of status perception on satisfaction further implies that green practices will resonate more when they align with symbolic cues of prestige. Managers should therefore invest not only in sustainable operations but also in storytelling and branding strategies that elevate sustainability as an aspirational value. Moreover, employee training programs that help staff articulate the value of these practices to guests could enhance both service delivery and perception.

On a theoretical level, the study extends the application of Self-Determination Theory (SDT) and the Theory of the Leisure Class (TLC) to the domain of sustainable luxury consumption. While SDT traditionally emphasizes the psychological foundations of motivation, this research demonstrates that intrinsic and extrinsic motivations can coexist and even complement each other in high-status consumption contexts. Sustainability, once perceived as utilitarian or restrictive, can be reimagined as an enabler of personal values and social prestige. Additionally, the incorporation of a latent interaction term between CBPs and TLC contributes to a deeper understanding of how symbolic consumption interacts with operational practices to influence customer satisfaction. This integrated view helps move beyond binary thinking about motivation and sustainability, revealing instead a complex interplay where ethical and status-driven consumption are not necessarily mutually exclusive. Furthermore, the study responds to recent calls in tourism and sustainability research to move beyond measuring “green intentions” and toward unpacking how consumers interpret, rationalize, and emotionally respond to sustainable service environments. By offering a theoretically grounded and empirically validated model, this study contributes to the growing body of literature exploring how luxury and sustainability co-evolve in contemporary consumption culture.

7 Limitations and scope of future research

This study, while offering important insights into how circular business practices influence consumer motivations and satisfaction in luxury hospitality, is subject to several limitations. A primary limitation is its exclusive focus on environmental sustainability, which omits critical dimensions of the broader “triple bottom line” framework—namely, social and economic sustainability. In particular, the study does not account for ethical labor conditions, staff welfare, or broader community impacts, all of which are essential components of socially responsible tourism. This scope limitation stems from the design of the survey instrument and the availability of data. Another limitation lies in the reliance on self-reported data, which may be influenced by social desirability bias, especially in a domain like sustainability where guests may feel compelled to present themselves in a favorable light. Additionally, the research employs a cross-sectional design, capturing responses at a single point in time, which restricts the ability to make causal inferences or assess how attitudes and behaviors evolve. The geographical focus on four regions—India, Dubai, Indonesia, and Mexico—adds valuable diversity but may limit the generalizability of findings to other cultural or economic contexts where perceptions of luxury and sustainability may differ. Finally, the study adopts a quantitative approach, which, while robust for modeling relationships between constructs, does not capture the nuanced, subjective experiences that qualitative methods might reveal. These limitations highlight areas for future research, such as incorporating social sustainability metrics, conducting longitudinal or cross-cultural studies, and applying mixed methods approaches to explore the deeper meanings guests associate with sustainable luxury experiences.

8 Future research directions

• Integrate social and economic sustainability dimensions, especially labor practices and local community engagement.

• Use longitudinal or experimental designs to better assess changes in sustainability behavior over time.

• Incorporate hotel staff and managerial perspectives to contrast internal sustainability intentions with external guest perceptions.

• Expand geographically to include additional cultural settings (e.g., Europe, North America, Japan) for broader generalizability.

• Apply qualitative methods to capture deeper psychological, emotional, and ethical interpretations of sustainable luxury.

By addressing these limitations, future studies can build a more holistic, multidimensional, and nuanced understanding of sustainability in luxury hospitality, helping the industry balance its ecological responsibilities with the promise of exclusivity and exceptional guest experience.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Nikhilesh Sinha, Hult International Business School. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

PS: Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SH: Resources, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. OH: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Rephrase the sentences written by me for better readability and grammar.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsut.2025.1640400/full#supplementary-material

References

Amatulli, C., De Angelis, M., Korschun, D., and Romani, S. (2018). Consumers' perceptions of luxury brands' CSR initiatives: an investigation of the role of status and conspicuous consumption. J. Clean. Prod. 194, 277–287. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.05.111

Aragon-Correa, J. M.-T.-R. (2015). Sustainability issues and hospitality and tourism firms' strategies: analytical review and future directions. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 27, 498–522. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-11-2014-0564

Arthur D. Little. (2024). The Rise of Luxury Hospitality. Boston: Arthur D. Little LLC. Available online at: https://www.adlittle.com/sites/default/files/viewpoints/ADL_Rise_of_luxury_hospitality_2024.pdf (Accessed September 6, 2021).

Athwal, N. W. (2019). Sustainable luxury marketing: a synthesis and research agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 21, 405–426. doi: 10.1111/ijmr.12195

Bagozzi, R. A. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 16, 74–94. doi: 10.1007/BF02723327

Banerjee, S. B. (2008). Corporate social responsibility: the good, the bad and the ugly. Crit. Sociol. 34, 51–79. doi: 10.1177/0896920507084623

Brough, A. R. (2016). Is eco-friendly unmanly? The green-feminine stereotype and its effect on sustainable consumption. J. Consum. Res. 43, 567–582. doi: 10.1093/jcr/ucw044

Campbell, D. T. (1959). Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-multimethod matrix. Psychol. Bull. 56, 81–105. doi: 10.1037/h0046016

Chandon, J. L.-F. (2016). Pursuing the concept of luxury: an exploratory investigation of consumers' motivations to indulge in luxury consumption. J. Bus. Res. 69, 299–308. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.08.001

Coghlan, A., and Bynoe, S. (2023). Designing sustainability changes in a tourist accommodation context from a systems perspective. Front. Sustain. Tour. 2, 1–14. doi: 10.3389/frsut.2023.1289009

Credit Suisse Research Institute (2023). Global Wealth Report 2023: Leading Perspectives to Navigate the Future. Zurich: Credit Suisse AG.

Cronin, J. J. (2000). Assessing the effects of quality, value, and customer satisfaction on consumer behavioral intentions in service environments. J. Retail. 76, 193–218. doi: 10.1016/S0022-4359(00)00028-2

Davies, I. A. (2011). Do consumers care about ethical-luxury? J. Bus. Ethics 106, 37–51. doi: 10.1007/s10551-011-1071-y

Deci, E. L. (1985). Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior. New York, NY: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-2271-7

Delmas, M. A., and Burbano, V. C. (2011). The drivers of greenwashing. Calif. Manag. Rev. 54, 64–87. doi: 10.1525/cmr.2011.54.1.64

Eckhardt, G. M. (2014). The rise of inconspicuous consumption. J. Mark. Manag. 31, 807–826. doi: 10.1080/0267257X.2014.989890

Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2013). Towards the Circular Economy Vol. 2: Opportunities for the Consumer Goods Sector. Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Available online at: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/towards-the-circular-economy-vol-2-opportunities-for-the-consumer-goods (Accessed September 6, 2021).

Font, X. E. (2017). Greenhushing: the deliberate under communicating of sustainability practices by tourism businesses. J. Sustain. Tour. 25, 1007–1023. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2016.1158829

Fornell, C. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 18, 39–50. doi: 10.1177/002224378101800104

Gagné, M. (2005). Self-determination theory and work motivation. J. Organ. Behav. 26, 331–362. doi: 10.1002/job.322

Geissdoerfer, M. P. (2017). The circular economy – a new sustainability paradigm? J. Clean. Prod. 143, 757–768. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.12.048

Gleim, M. R. (2013). Against the green: a multi-method examination of the barriers to green consumption. J. Retail. 89, 44–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jretai.2012.10.001

Griskevicius, V. T. (2010). Going green to be seen: status, reputation, and conspicuous conservation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 98, 392–404. doi: 10.1037/a0017346

Guo, C. L. (2025a). Knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) towards climate change among tourists: a systematic review. Tour. Hosp. 6, 3–28. doi: 10.3390/tourhosp6010032

Guo, Y. C. (2025b). Toward green tourism: the role of renewable energy for sustainable development in developing nations. Front. Sustain. Tour. 3, 1–13. doi: 10.3389/frsut.2025.1512922

Gutiérrez-Martínez, I. F. (2019). Translating sustainability into competitiveness. Corp. Gov. 19, 1324–1343. doi: 10.1108/CG-01-2019-0031

Hair, J. R. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 31, 2–24. doi: 10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

Han, H. (2018). Role of motivations for luxury cruise traveling, satisfaction, and involvement in building traveler loyalty. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 70, 75–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.10.024

Han, Y. J. (2010). Signaling status with luxury goods: the role of brand prominence. J. Mark. 74, 15–30. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.74.4.015

He, L. (2024). Authentic or comfortable? what tourists want in the destination. Front. Sustain. Tour. 3, 1–11. doi: 10.3389/frsut.2024.1437014

Hennig's, N. W. (2013). Unleashing the power of luxury: antecedents of luxury brand perception and effects on luxury brand strength. J. Brand Manag. 20, 705–715. doi: 10.1057/bm.2013.11

Hu, B. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

Jin-Soo Lee, L.-T. (2010). Understanding how consumers view green hotels: how a hotel's green image can influence behavioural intentions. J. Sustain. Tour. 18, 901–914. doi: 10.1080/09669581003777747

Jones, P. H. (2016). Sustainability in the hospitality industry: some personal reflections on corporate challenges and research agendas. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 28, 36–67. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-11-2014-0572

Kapferer, J. M. (2014). Is luxury compatible with sustainability? Luxury consumers' viewpoint. J. Brand Manag. 21, 1–22. doi: 10.1057/bm.2013.19

Kapferer, J. N. (2009). The specificity of luxury management: turning marketing upside down. J. Brand Manag. 16, 311–322. doi: 10.1057/bm.2008.51

Kapferer, J. N. (2012). The Luxury Strategy: Break the Rules of Marketing to Build Luxury Brands, 2nd Edn. London: Kogan Page.

Kapferer, J. N. (2015). Kapferer on Luxury: How Luxury Brands Can Grow Yet Remain Rare. New York, NY: Kogan Page.

Kirchherr, J. R. (2017). Conceptualizing the circular economy: an analysis of 114 definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 127, 221–232. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2017.09.005

Lim, W. (2016). Creativity and sustainability in hospitality and tourism. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 21, 161–167. doi: 10.1016/j.tmp.2016.02.001

Line, N. D. (2015). The effects of environmental and luxury beliefs on intention to patronize green hotels: the moderating effect of destination image. J. Sustain. Tour. 24, 904–925. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2015.1091467

Menegaki, A. (2025). How do tourism and environmental theories intersect? Tour. Hosp. 6, 3–10. doi: 10.3390/tourhosp6010028

Nahas, N., Mendiolea, J., Sinh, Y., and Cattouf, N. (2024). The Rise of Luxury Hospitality: Trends & Differentiators for Luxury Hotel Operators [Report]. Brussels: Arthur D. Little.

Oliver, R. (1980). A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. J. Mark. Res. 17, 460–469. doi: 10.1177/002224378001700405

Oliver, R. L. (1997). Satisfaction: A Behavioral Perspective on the Consumer. New York, NY: McGraw Hill.

Parasuraman, A. Z. (1988). SERVQUAL: a multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. J. Retail. 64, 12–40.

Podsakoff, P. M.-Y. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Rahman, I. (2016). Predicting green hotel behavioral intentions using a theory of environmental commitment and sacrifice for the environment. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 52, 107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2015.09.007

Robinot, E., and Giannelloni, J. (2010). Do hotels green attributes contribute to customer satisfaction? J. Serv. Mark. 24, 157–169. doi: 10.1108/08876041011031127

Romero-Hernández, O. R. (2019). Maximizing the value of waste: from waste management to the circular economy. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 60, 757–764. doi: 10.1002/tie.21968

Ryan, R. M. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 55, 68–78. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Sakshi, S. C. (2020). Measuring the impact of sustainability policy and practices in tourism and hospitality industry. Bus. Strategy Environ. 29, 1109–1126. doi: 10.1002/bse.2420

Santos, M. V. (2019). Sustainability communication in hospitality in peripheral tourist destinations: implications for marketing strategies. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 11, 660–676. doi: 10.1108/WHATT-08-2019-0049

Schmitt, B. (1999). Experiential marketing. J. Mark. Manag. 15, 53–67. doi: 10.1362/026725799784870496

Shrivastava, P., and Gautam, V. (2024). Examining patronage intentions of customers: a case of green hotels. Front. Sustain. Tour. 3, 1–17. doi: 10.3389/frsut.2024.1429472

Spector, P. (2019). Do not cross me: optimizing the use of cross-sectional designs. J. Bus. Psychol. 34, 125–137. doi: 10.1007/s10869-018-09613-8

Spector, P. E. (2006). Method variance in organizational research: truth or urban legend? Organ. Res. Methods 9, 221–232. doi: 10.1177/1094428105284955

Su, C. C. (2020). Does sustainability index matter to the hospitality industry? Tour. Manag. 81, 1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104158

Tasci, A. (2017). Consumer demand for sustainability benchmarks in tourism and hospitality. Tour. Rev. 72, 375–391. doi: 10.1108/TR-05-2017-0087

Turker, D. O. (2019). Modeling social sustainability: analysis of hospitality e-distributors. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 11, 799–823. doi: 10.1108/SAMPJ-02-2019-0035

UBS Group AG (2023). Global Wealth Report 2023. Zurich: UBS Group AG. Available online at: https://advisors.ubs.com/gaffneygroup/mediahandler/media/582898/global-wealth-report-2023.pdf (Accessed September 6, 2021).

Veblen, T. (1889). The Theory of the Leisure Class: An Economic Study of Institutions. New York, NY: The Macmillan Company.

Vij, M. (2016). The cost competitiveness, competitiveness, and sustainability of the hospitality industry in India. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 8, 432–443. doi: 10.1108/WHATT-04-2016-0019

Walls, A. O. (2011). Understanding the consumer experience: an exploratory study of luxury hotels. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 20, 166–197. doi: 10.1080/19368623.2011.536074

White, K. (2013). When do (and don't) normative appeals influence sustainable consumer behaviors? J. Mark. 77, 78–95. doi: 10.1509/jm.11.0278

World Travel & Tourism Council (2025). World Travel & Tourism Council. Available online at: https://wttc.org/research/economic-impact (Accessed September 6, 2021).

Zeithaml, V. A. (1996). The behavioral consequences of service quality. J. Mark. 60, 31–46. doi: 10.1177/002224299606000203

Keywords: circular business practices (CBPs), Self-Determination Theory (SDT), Veblen's Theory of the Leisure Class (TLC), luxury hotel, behavioral intention

Citation: Shrivastava P, Hernandez SR and Hernandaz OR (2025) Sustainable consumption meets conspicuous leisure: a dual-theory exploration in luxury hospitality. Front. Sustain. Tour. 4:1640400. doi: 10.3389/frsut.2025.1640400

Received: 03 June 2025; Accepted: 30 August 2025;

Published: 09 October 2025.

Edited by:

Teoman Duman, Epoka University, AlbaniaReviewed by:

Francesc González-Reverté, Open University of Catalonia, SpainHuajie Shen, Fujian University of Technology, China

Copyright © 2025 Shrivastava, Hernandez and Hernandaz. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Priyanka Shrivastava, cHJpeWFua2Euc2hyaXZhc3RhdmFAZmFjdWx0eS5odWx0LmVkdQ==

Priyanka Shrivastava

Priyanka Shrivastava Sergio Romero Hernandez

Sergio Romero Hernandez Omar Romero Hernandaz1

Omar Romero Hernandaz1