- 1Department of Public Health Pharmacy and Management, School of Pharmacy, Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University, Pretoria, South Africa

- 2Saselamani Pharmacy, Saselamani, South Africa

- 3Department of Pharmacy, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Bahir Dar University, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia

- 4Public Health Supply Chain and Pharmacy Practice Research Unit, Department of Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacy Management, Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria

- 5Quality Assurance Unit, Central Medical Stores, Ministry of Health, Gabarone, Botswana

- 6Department of Pharmacy, School of Health Sciences, University of Zambia, Lusaka, Zambia

- 7Department of Pharmacy Practice and Policy, School of Pharmacy, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Namibia, Windhoek, Namibia

- 8Department of Periodontology and Implantology, Karnavati School of Dentistry, Karnavati University, Gandhinagar, India

- 9Strathclyde Institute of Pharmacy and Biomedical Sciences, University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, United Kingdom

- 10Antibiotic Policy Group, Institute for Infection and Immunity, City St. George’s, University of London, London, United Kingdom

- 11South African Vaccination and Immunization Centre, Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University, Pretoria, South Africa

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a global public health threat exacerbated by inappropriate antibiotic use. This is particularly important in Africa. The availability of substandard and falsified antibiotics, particularly among African countries, contributes to this adding to the burden of AMR. Poor monitoring and regulatory controls among African countries increases the public health risks of these antibiotics. This is especially the case in the informal sector. Addressing Africa’s battle against substandard and falsified antibiotics requires an integrated approach building on current WHO, Interpol and Pan-African initiatives. Activities include harmonizing regulatory activities across Africa and increasing the monitoring of available antibiotics as well as fines and sanctions for offenders. In addition, reducing the current high levels of inappropriate antibiotic use makes the market for falsified and substandard antibiotics considerably less attractive.

1 Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) increases both morbidity and mortality as well as appreciably increases healthcare costs if not addressed (1–4). As a result, AMR is now considered a critical global public health threat and the next potential pandemic unless multiple activities are undertaken across countries to address this situation (5–7). The principal countries to target to reduce AMR are low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) since the burden of AMR is greatest among these countries, which includes African countries (8–10).

AMR is driven by high levels of inappropriate use of antibiotics (11–13). High levels of AMR among African countries are also enhanced by the considerable availability of substandard and falsified antibiotics (14–18). The economic burden of substandard and falsified medicines is considerable with an estimated US$30.5 billion globally spent on these medicines each year alone (19, 20), which includes antibiotics (20). In addition to the appreciable monies spent on these medicines, Beargie et al. (2019) estimated that in the Northern Region of Nigeria alone, 9,700 deaths each year were due to substandard and falsified medicines with an estimated economic loss of $698 million ($697–$700 million) (21).

In their study, Feeney et al. (2024) documented that antibiotics accounted for 36% of all counterfeit medicines seized globally by Customs (22). Similarly, Ozawa et al. (2018) ascertained that the overall prevalence of substandard medicines among LMICs was 13.6%, highest in Africa at 18.7% (23). Wada et al. (2022) also found that the African region had the highest prevalence of poor-quality medicines, which they estimated to be 18.7% of available medicines (14, 24). Similar rates were reported by Asrade Mekonnen et al. (2024), who estimated that the prevalence of substandard or falsified medicines across Africa was 22.6%, with antibiotics accounting for the majority of these (44.6%) (16). Similar rates were also seen in the studies by Waffo Tchounga et al. (2021), Chiumia et al. (2022), and Maffioli et al. (2024) (25–27). Some of the highest rates of substandard and falsified medicines have been seen in Ghana, where in one study 66.4% of the total number of sampled antibiotics were seen as substandard (28, 29). Studies in Kenya also documented a 37.7% prevalence rate for substandard amoxicillin/co-amoxiclav (30). Falsified amoxicillin has also recently been reported in Cameroon and the Central African Republic (31). However, lower rates of falsified and substandard antimicrobials have been documented in other studies in Ghana and across Africa (32–35).

No counterfeit medicines were identified in South Africa in the study of Lehmann et al. (2018), with only a limited number seen in community outlets in practice Botswana and Namibia in recent years with their stricter controls regarding the supply and monitoring of medicines in these countries (36–38). In Botswana, there is a specific enforcement unit responsible for establishing and maintaining an effective import system for the Botswana Ministry of Health, with planned inspections increasing in recent years (39). The number of trained law enforcement officers helping with this activity has also increased in recent years in Botswana, which have resulted in greater confiscation of substandard medicines and other products in recent years (39). This included limited supplies of gentamicin and tetracycline especially among informal vendors (39). Increased collaboration between the various government departments in Botswana, alongside coordinated law enforcement activities, has resulted in a 65% increase in the confiscation of goods and medicines in recent years, amounting to 35,097 units of various unauthorized regulated items principally from informal sellers (39, 40). Informal sellers are also being increasingly monitored in Botswana as an appreciable percentage of unregistered medicines are seen in this sector (39, 40). Personnel from the Botswana Police Department are also used to help disrupt the activities of informal sellers; however, the instigation of fines for illegal activities is currently limited (40).

Issues with substandard and falsified medicines in Africa are exacerbated by concerns with community pharmacists’ knowledge and practices on these issues (41, 42), coupled with high rates of dispensing of antibiotics without a prescription across a number of African countries (37, 43, 44).

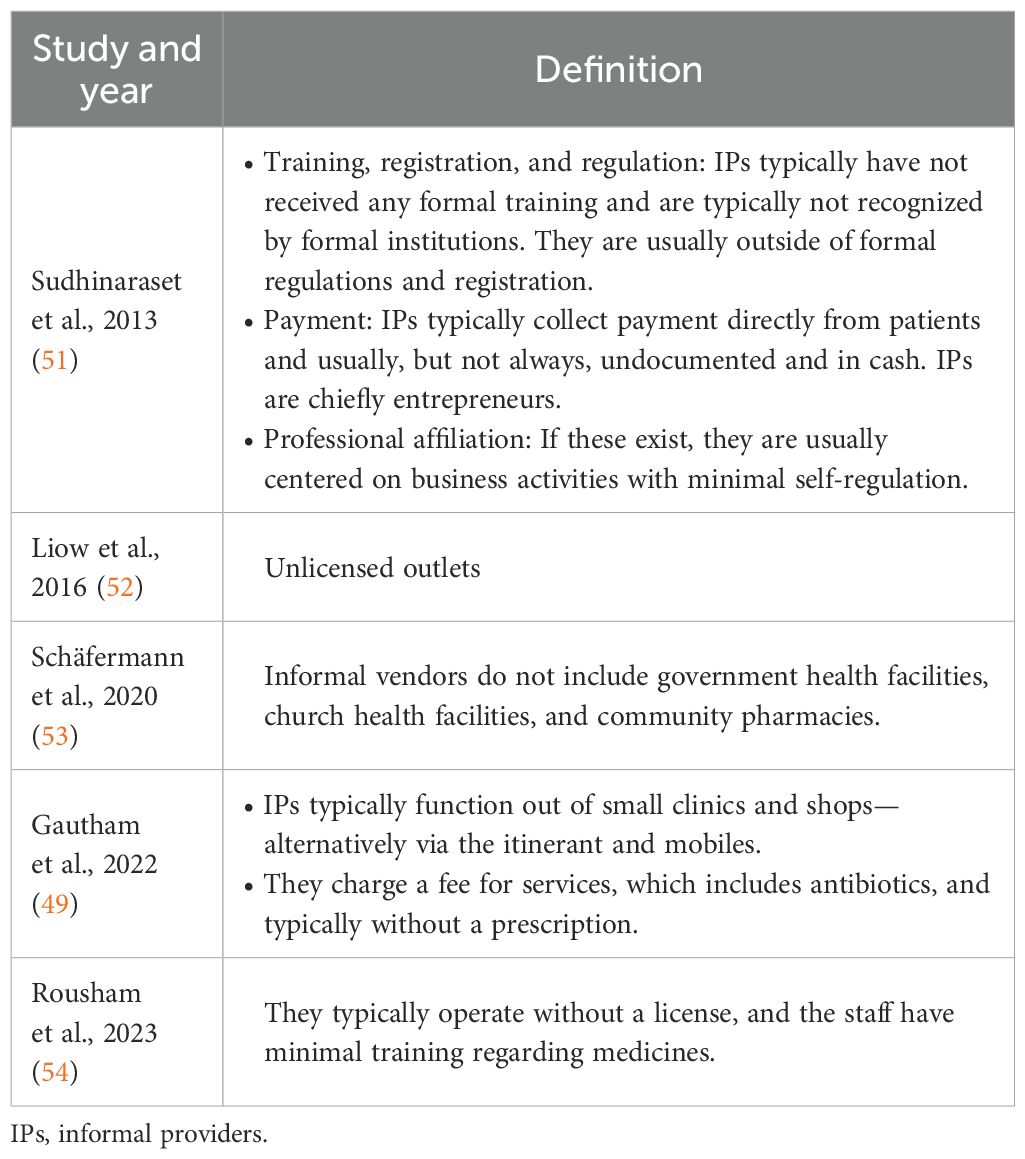

Overall, substandard and falsified antibiotics can be found in both formal sectors, involving community pharmacies, and informal sectors across Africa (7). The informal sector plays an important role across Africa where higher rates of substandard and falsified antibioitics are seen compared with the situation in community pharmacies (45). This situation is exacerbated among African countries where the monitoring and control of medicine importation and distribution are generally currently limited (7, 39, 46–48). Typically where this occurs, informal sector for medicines outlets can be better stocked with medicines, including antibiotics, than government health facilities (49, 50). However, the informal sector is not evident, or only in limited numbers, in some African countries, including Namibia and South Africa, with their increasingly stricter controls. Definitions of the informal sector are documented in Table 1.

To date, principal initiatives to reduce the prevalence of substandard and falsified medicines across Africa have been centered on regulatory activities (45). These include the World Health Organization’s (WHO) “Lome´ Initiative” alongside the development of an African Medicines Agency (7, 18, 55–60), building on the ongoing efforts among the East African community (61). Governments within several African countries have also endorsed the Council of Europe’s Medicrime Convention Treaty to help reduce the extent of substandard and falsified medicines (7, 62). We are also seeing leading agencies such as the Nigerian National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control initiating multiple activities to reduce the problem (25).

Potential ways forward to reduce the extent of substandard and falsified antibiotics across Africa are discussed in Section 2, which is based on the considerable knowledge of the co-authors. The potential activities include governments and health authorities instigating multiple activities across Africa. The suggested activities include a continued focus on substandard and falsified medicines, including antibiotics, prioritizing the registration of essential antibiotics and away from all antibiotics, undertaking greater monitoring of drug stores and community pharmacies as well as instigating fines where there are concerns with the quality of dispensed antibiotics. Alongside this, reducing the current high levels of inappropriate prescribing and dispensing of antibiotics currently seen across Africa (7, 37, 63, 64). In addition, greater education of all key stakeholder groups to help identify and report substandard and falsified medicines (65, 66). Focusing and encouraging the appropriate use of only essential antibiotics will also reduce the attractiveness of this market and subsequently improve public health (7).

We are seeing, for instance, LMICs such as China making appreciable progress with improving the quality of their locally produced multiple-sourced medicines, including antibiotics, with appreciable penalties when substandard and falsified medicines are found (67–69). We are also seeing countries such as India and Pakistan instigate a number of measures, including bar coding on packs of antibiotics, in an attempt to reduce the prevalence of counterfeit medicines (70, 71). Similarly, in Botswana, there has been increased monitoring of facilities, including among informal sellers, to disrupt this market (39, 40).

2 Policy options to reduce the extent of substandard and falsified medicines across Africa

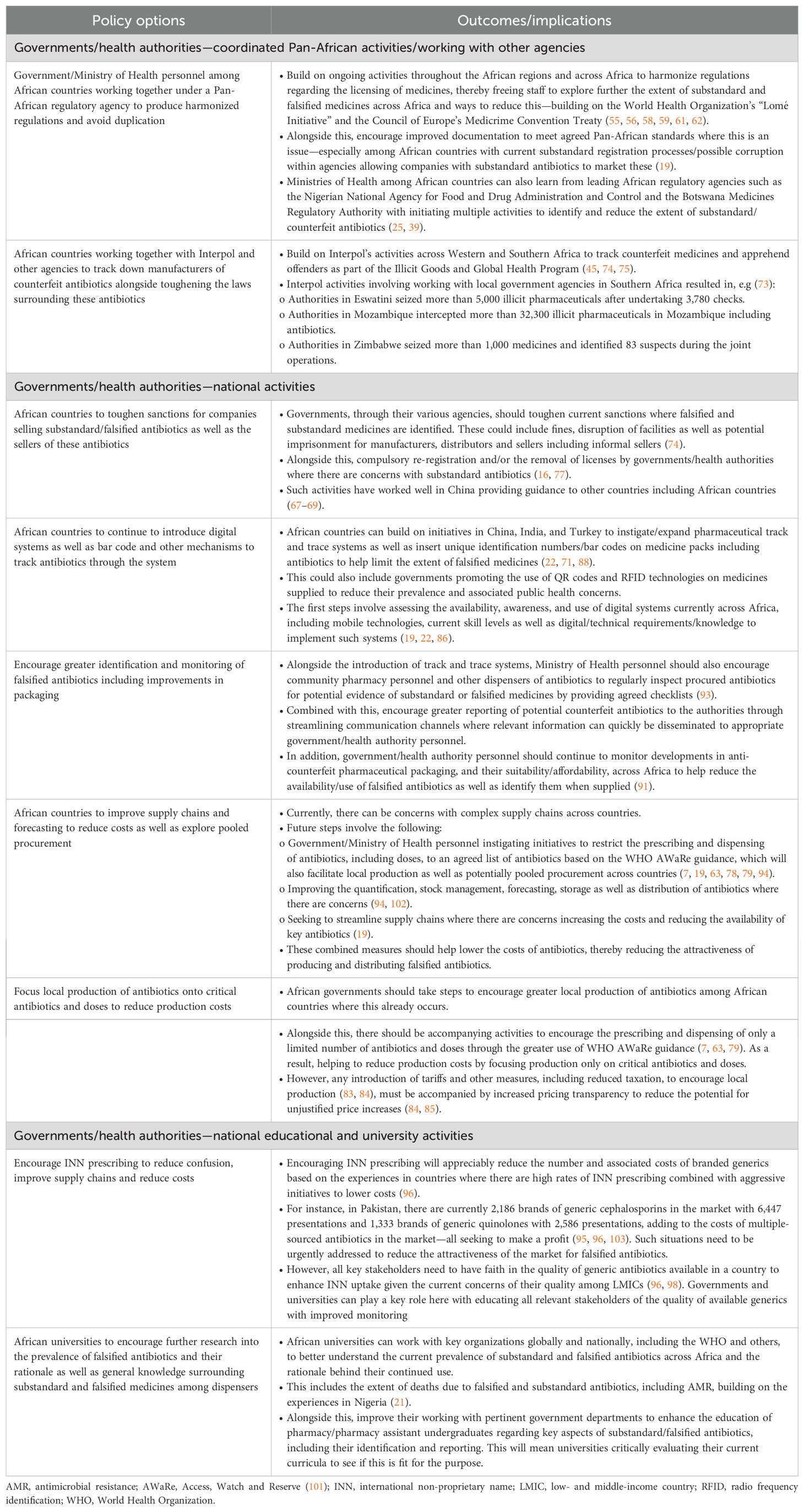

A number of policy options have been proposed to reduce the extent of substandard and falsified medicines across Africa. These include activities aimed at both the formal and informal sectors (Table 2), and involve initiatives by governments which includes enhancing current regulations as well as other initiatives to reduce the extent of substandard and falsified medicines.

Ongoing initiatives among all key stakeholder groups to reduce the high levels of inappropriate prescribing and dispensing of antibiotics seen among African countries, thereby reducing the attractiveness of marketing substandard and falsified antibiotics, are discussed elsewhere in this Frontiers Special Issue as well as by Saleem et al. (2025) (7, 63). Consequently, they will not be part of Table 2.

3 Actionable recommendations

The actionable recommendations (Table 3) are based on their impact where known in published studies across LMICs, including African countries, combined with the considerable experience of the co-authors. As mentioned, initiatives to reduce inappropriate prescribing and dispensing of antibiotics, thereby reducing the attractiveness of the substandard and falsified antibiotics market, are discussed elsewhere in this Frontiers Special Issue as well as in Saleem et al. (2025) (7, 63). Similar to the data in Table 2, this will include activities surrounding regulations as well as other initiatives to reduce the extent of substandard and falsified medicines across Africa.

We are aware of a number of limitations with our policy brief. This primarily includes the fact that we have not undertaken a systematic review. However, we have undertaken a narrative review including examples of potential policy options to tackle falsified and substandard medicines followed by potential actionable recommendations. The guidance is based on the considerable experience of the co-authors working across Africa and other LMICs. We have successfully used this approach before (7, 37, 63, 104).

4 Conclusions

Addressing Africa’s battle against substandard and falsified antibiotics to reduce AMR requires integrated, scalable, and context-specific policies to address gaps in regulation, enforcement, education, affordability, and supply chain monitoring. This builds on ongoing initiatives among the WHO, Interpol and Pan-African agencies as well as exemplars in other LMICs. Reducing high levels of inappropriate use of antibiotics across Africa, alongside encouraging INN prescribing with appropriate safeguards, will also help reduce the attractiveness of the counterfeit antibiotic market. These combined activities will help address high levels of AMR across Africa.

Author contributions

TM: Investigation, Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Validation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. BM: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. CU: Data curation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – review & editing. BP: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Formal analysis, Methodology. MM: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Validation, Methodology, Formal analysis. AK: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Formal analysis, Validation, Data curation. EH: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Data curation, Validation, Investigation, Visualization. SK: Formal analysis, Data curation, Validation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. BG: Investigation, Data Curation, Methodology, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. JM: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Investigation, Validation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. GBD 2021 Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance 1990-2021: a systematic analysis with forecasts to 2050. Lancet. (2024) 404:1199–226. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)01867-1

2. Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet. (2022) 399:629–55. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02724-0

3. Dadgostar P. Antimicrobial resistance: implications and costs. Infect Drug Resist. (2019) 12:3903–10. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S234610

4. Poudel AN, Zhu S, Cooper N, Little P, Tarrant C, Hickman M, et al. The economic burden of antibiotic resistance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One. (2023) 18:e0285170. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0285170

5. Gautam A. Antimicrobial resistance: the next probable pandemic. JNMA. (2022) 60:225–8. doi: 10.31729/jnma.7174

6. Nkengasong JN and Tessema SK. Africa needs a new public health order to tackle infectious disease threats. Cell. (2020) 183:296–300. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.041

7. Saleem Z, Mekonnen BA, Orubu ES, Islam MA, Nguyen TTP, Ubaka CM, et al. Current access, availability and use of antibiotics in primary care among key low- and middle-income countries and the policy implications. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. (2025), 1–42. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2025.2477198

8. Sulis G, Sayood S, and Gandra S. Antimicrobial resistance in low- and middle-income countries: current status and future directions. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. (2022) 20:147–60. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2021.1951705

9. Lewnard JA, Charani E, Gleason A, Hsu LY, Khan WA, Karkey A, et al. Burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in low-income and middle-income countries avertible by existing interventions: an evidence review and modelling analysis. Lancet. (2024) 403:2439–54. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00862-6

10. Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. The burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in the WHO African region in 2019: a cross-country systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. (2024) 12:e201–e16. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(23)00539-9

11. Llor C and Bjerrum L. Antimicrobial resistance: risk associated with antibiotic overuse and initiatives to reduce the problem. Ther Adv Drug Saf. (2014) 5:229–41. doi: 10.1177/2042098614554919

12. Godman B, Egwuenu A, Haque M, Malande OO, Schellack N, Kumar S, et al. Strategies to improve antimicrobial utilization with a special focus on developing countries. Life. (2021) 11:528. doi: 10.3390/life11060528

13. Gajdács M and Jamshed S. Editorial: Knowledge, attitude and practices of the public and healthcare-professionals towards sustainable use of antimicrobials: the intersection of pharmacology and social medicine. Front Antibiot. (2024) 3:1374463. doi: 10.3389/frabi.2024.1374463

14. Wada YH, Abdulrahman A, Ibrahim Muhammad M, Owanta VC, Chimelumeze PU, and Khalid GM. Falsified and substandard medicines trafficking: A wakeup call for the African continent. Public Health Pract. (2022) 3:100240. doi: 10.1016/j.puhip.2022.100240

15. Zabala GA, Bellingham K, Vidhamaly V, Boupha P, Boutsamay K, Newton PN, et al. Substandard and falsified antibiotics: neglected drivers of antimicrobial resistance? BMJ Glob Health. (2022) 7:e008587. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2022-008587

16. Asrade Mekonnen B, Getie Yizengaw M, and Chanie Worku M. Prevalence of substandard, falsified, unlicensed and unregistered medicine and its associated factors in Africa: a systematic review. J Pharm Policy Pract. (2024) 17:2375267. doi: 10.1080/20523211.2024.2375267

17. Gulumbe BH and Adesola RO. Revisiting the blind spot of substandard and fake drugs as drivers of antimicrobial resistance in LMICs. Ann Med Surg. (2023) 85:122–3. doi: 10.1097/MS9.0000000000000113

18. Tegegne AA, Feissa AB, Godena GH, Tefera Y, Hassen HK, Ozalp Y, et al. Substandard and falsified antimicrobials in selected east African countries: A systematic review. PloS One. (2024) 19:e0295956. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0295956

19. WHO. Substandard and falsified medical products (2024). Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/substandard-and-falsified-medical-products (Accessed May 12, 2025).

20. ACVISS. Counterfeit antibiotics & AMR: A silent global catastrophe (2025). Available online at: https://blog.acviss.com/counterfeit-antibiotics-and-amr/_7ekbm2m0vas4 (Accessed May 12, 2025).

21. Beargie SM, Higgins CR, Evans DR, Laing SK, Erim D, and Ozawa S. The economic impact of substandard and falsified antimalarial medications in Nigeria. PloS One. (2019) 14:e0217910. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0217910

22. Feeney AJ, Goad JA, and Flaherty GT. Global perspective of the risks of falsified and counterfeit medicines: A critical review of the literature. Travel Med Infect Dis. (2024) 61:102758. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2024.102758

23. Ozawa S, Evans DR, Bessias S, Haynie DG, Yemeke TT, Laing SK, et al. Prevalence and estimated economic burden of substandard and falsified medicines in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. (2018) 1:e181662. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.1662

24. Ncube BM, Dube A, and Ward K. Establishment of the African Medicines Agency: progress, challenges and regulatory readiness. J Pharm Policy Pract. (2021) 14:29. doi: 10.1186/s40545-020-00281-9

25. Maffioli EM, Montás MC, and Anyakora C. Excessive active pharmaceutical ingredients in substandard and falsified drugs should also raise concerns in low-income countries. J Glob Health. (2024) 14:03029. doi: 10.7189/jogh.14.03029

26. Chiumia FK, Nyirongo HM, Kampira E, Muula AS, and Khuluza F. Burden of and factors associated with poor quality antibiotic, antimalarial, antihypertensive and antidiabetic medicines in Malawi. PloS One. (2022) 17:e0279637. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0279637

27. Waffo Tchounga CA, Sacré PY, Ciza Hamuli P, Ngono Mballa R, Nnanga Nga E, Hubert P, et al. Poor-quality medicines in Cameroon: A critical review. Am J Trop Med Hyg. (2021) 105:284–94. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-1346

28. Bekoe SO, Ahiabu MA, Orman E, Tersbøl BP, Adosraku RK, Hansen M, et al. Exposure of consumers to substandard antibiotics from selected authorised and unauthorised medicine sales outlets in Ghana. Trop Med Int Health. (2020) 25:962–75. doi: 10.1111/tmi.13442

29. Opuni KF, Sunkwa-Mills G, Antwi MA, Squire A, Afful GY, Rinke de Wit TF, et al. Quality assessment of medicines in selected resource-limited primary healthcare facilities using low- to medium-cost field testing digital technologies. Digit Health. (2024) 10:20552076241299064. doi: 10.1177/20552076241299064

30. Koech LC, Irungu BN, Ng’ang’a MM, Ondicho JM, and Keter LK. Quality and brands of amoxicillin formulations in nairobi, Kenya. BioMed Res Int. (2020) 2020:7091278. doi: 10.1155/2020/7091278

31. Travel health Pro. Falsified antibiotics reported in WHO African Region. (2025). Available online at: https://travelhealthpro.org.uk/pdfs/generate/news.php?new=842 (Accessed May 16, 2025).

32. Osei-Asare C, Oppong EE, Owusu FWA, Apenteng JA, Alatu YO, and Sarpong R. Comparative quality evaluation of selected brands of cefuroxime axetil tablets marketed in the greater accra region of Ghana. ScientificWorldJournal. (2021) 2021:6659995. doi: 10.1155/2021/6659995

33. Khuluza F, Kigera S, and Heide L. Low prevalence of substandard and falsified antimalarial and antibiotic medicines in public and faith-based health facilities of southern Malawi. Am J Trop Med Hyg. (2017) 96:1124–35. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.16-1008

34. Kimaro E, Yusto E, Mohamed A, Silago V, Damiano P, Hamasaki K, et al. Quality equivalence and in-vitro antibiotic activity test of different brands of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid tablets in Mwanza, Tanzania: A cross sectional study. Heliyon. (2024) 10:e23418. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e23418

35. Abraham W, Abuye H, Kebede S, and Suleman S. In vitro comparative quality assessment of different brands of doxycycline hyclate finished dosage forms: capsule and tablet in Jimma Town, South-West Ethiopia. Adv Pharmacol Pharm Sci. (2021) 2021:6645876. doi: 10.1155/2021/6645876

36. Lehmann A, Katerere DR, and Dressman J. Drug quality in South Africa: A field test. J Pharm Sci. (2018) 107:2720–30. doi: 10.1016/j.xphs.2018.06.012

37. Sono TM, Yeika E, Cook A, Kalungia A, Opanga SA, Acolatse JEE, et al. Current rates of purchasing of antibiotics without a prescription across sub-Saharan Africa; rationale and potential programmes to reduce inappropriate dispensing and resistance. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. (2023) 21:1025–55. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2023.2259106

38. BOMRA. MRSA: 2019 Regulations . Available online at: https://www.bomra.co.bw/downloads/51-74-wpfd-regulations-1632487580 (Accessed May 16, 2025).

39. BOMRA. BOMRA Annual Report 2024 . Available online at: https://www.bomra.co.bw/downloads/51-119-wpfd-annual-reports-1657024402 (Accessed May 16, 2025).

40. BOMRA. Transitioning to Maturity Level 3—2022/2023 ANNUAL REPORT . Available online at: https://www.bomra.co.bw/downloads/51-119-wpfd-annual-reports-1657024402 (Accessed May 16, 2025).

41. Mekonen Z, Meshesha S, and Girma B. Knowledge, attitude and practice of community pharmacy professionals’ towards substandard and falsified medicines in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: A cross-sectional survey. Research & Reviews in Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences. (2022) 11:22–34.

42. Worku MC, Mitku ML, Ayenew W, Limenh LW, Ergena AE, Geremew DT, et al. Assessment of knowledge, attitude, and practice on substandard and counterfeit pharmaceutical products among pharmacy professionals in Gondar City, North-West Ethiopia. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. (2024) 16:102140. doi: 10.1016/j.cptl.2024.102140

43. Sono TM, Markovic-Pekovic V, and Godman B. Effective programmes to reduce inappropriate dispensing of antibiotics in community pharmacies especially in developing countries. Adv Hum Biol. (2024) 14:1–4. doi: 10.4103/aihb.aihb_128_23

44. Torres NF, Chibi B, Kuupiel D, Solomon VP, Mashamba-Thompson TP, and Middleton LE. The use of non-prescribed antibiotics; prevalence estimates in low-and-middle-income countries. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Public Health. (2021) 79:2. doi: 10.1186/s13690-020-00517-9

45. Munzhedzi M, Kumar S, Godman B, and Meyer J. Potential ways to improve the supply and use of quality-assured antibiotics across sectors in developing countries to reduce antimicrobial resistance. (2025) 9900:10.4103/aihb.aihb_132_25. doi: 10.4103/aihb.aihb_132_25

46. Tshilumba PM, Ilangala AB, Mbinze Kindenge J, Kasongo IM, Kikunda G, Rongorongo E, et al. Detection of substandard and falsified antibiotics sold in the democratic republic of the congo using validated HPLC and UV-visible spectrophotometric methods. Am J Trop Med Hyg. (2023) 109:480–8. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.23-0045

47. Waffo Tchounga CA, Sacré PY, Ciza Hamuli P, Ngono Mballa R, De Bleye C, Ziemons E, et al. Prevalence of poor quality ciprofloxacin and metronidazole tablets in three cities in Cameroon. Am J Trop Med Hyg. (2023) 108:403–11. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.22-0221

48. Sohaili A, Asin J, and Thomas PPM. The fragmented picture of antimicrobial resistance in Kenya: A situational analysis of antimicrobial consumption and the imperative for antimicrobial stewardship. Antibiotics. (2024) 13:197. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics13030197

49. Gautham M, Miller R, Rego S, and Goodman C. Availability, prices and affordability of antibiotics stocked by informal providers in rural India: A cross-sectional survey. Antibiot. (2022) 11:523. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics11040523

50. Knowles R, Sharland M, Hsia Y, Magrini N, Moja L, Siyam A, et al. Measuring antibiotic availability and use in 20 low- and middle-income countries. Bull World Health Organ. (2020) 98:177–87c. doi: 10.2471/BLT.19.241349

51. Sudhinaraset M, Ingram M, Lofthouse HK, and Montagu D. What is the role of informal healthcare providers in developing countries? A systematic review. PloS One. (2013) 8:e54978. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054978

52. Liow E, Kassam R, and Sekiwunga R. How unlicensed drug vendors in rural Uganda perceive their role in the management of childhood malaria. Acta Trop. (2016) 164:455–62. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2016.10.012

53. Schäfermann S, Hauk C, Wemakor E, Neci R, Mutombo G, Ngah Ndze E, et al. Substandard and falsified antibiotics and medicines against noncommunicable diseases in western Cameroon and northeastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Am J Trop Med Hyg. (2020) 103:894–908. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0184

54. Rousham EK, Nahar P, Uddin MR, Islam MA, Nizame FA, Khisa N, et al. Gender and urban-rural influences on antibiotic purchasing and prescription use in retail drug shops: a one health study. BMC Public Health. (2023) 23:229. doi: 10.1186/s12889-023-15155-3

55. Macé C, Nikiema JB, Sarr OS, Ciza Hamuli P, Marini RD, Neci RC, et al. The response to substandard and falsified medical products in francophone sub-Saharan African countries: weaknesses and opportunities. J Pharm Policy Pract. (2023) 16:117. doi: 10.1186/s40545-023-00628-y

56. Kniazkov S, Dube-Mwedzi S, and Nikiema JB. Prevention, Detection and Response to incidences of substandard and falsified medical products in the Member States of the Southern African Development Community. J Pharm Policy Pract. (2020) 13:71. doi: 10.1186/s40545-020-00257-9

57. WHO. Launch of the Lomé Initiative (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/launch-of-the-lom%C3%A9-initiative (Accessed May 12, 2025).

58. Abdulwahab AA, Okafor UG, Adesuyi DS, Miranda AV, Yusuf RO, and Eliseo Lucero-Prisno D 3rd. The African Medicines Agency and Medicines Regulation: Progress, challenges, and recommendations. Health Care Sci. (2024) 3:350–9. doi: 10.1002/hcs2.117

59. Ncube BM, Dube A, and Ward K. The domestication of the African Union model law on medical products regulation: Perceived benefits, enabling factors, and challenges. Front Med. (2023) 10:1117439. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1117439

60. The Namibian. Africa hamstrung by deadly flood of fake medicine (2020). Available online at: https://www.Namibian.com.na/africa-hamstrung-by-deadly-flood-of-fake-medicine/ (Accessed May 13, 2025).

61. Ndomondo-Sigonda M, Miot J, Naidoo S, Masota NE, Ng’andu B, Ngum N, et al. Harmonization of medical products regulation: a key factor for improving regulatory capacity in the East African Community. BMC Public Health. (2021) 21:187. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10169-1

62. COE I. Council of Europe Convention on the counterfeiting of medical products and similar crimes involving threats to public health (CETS No. 211) (2016). Available online at: https://www.coe.int/en/web/conventions/full-list?module=treaty-detail&treatynum=211 (Accessed May 10, 2025).

63. Saleem Z, Moore CE, Kalungia AC, Schellack N, Ogunleye O, Chigome A, et al. Status and implications of the knowledge, attitudes and practices towards AWaRe antibiotic use, resistance and stewardship among low- and middle-income countries. JAC-Antimicrob Resist. (2025) 7:dlaf033. doi: 10.1093/jacamr/dlaf033

64. Godman B, Haque M, McKimm J, Abu Bakar M, Sneddon J, Wale J, et al. Ongoing strategies to improve the management of upper respiratory tract infections and reduce inappropriate antibiotic use particularly among lower and middle-income countries: findings and implications for the future. Curr Med Res Opin. (2020) 36:301–27. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2019.1700947

65. El-Dahiyat F, Fahelelbom KMS, Jairoun AA, and Al-Hemyari SS. Combatting substandard and falsified medicines: public awareness and identification of counterfeit medications. Front Public Health. (2021) 9:754279. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.754279

66. Ferrario A, Orubu ESF, Adeyeye MC, Zaman MH, and Wirtz VJ. The need for comprehensive and multidisciplinary training in substandard and falsified medicines for pharmacists. BMJ Glob Health. (2019) 4:e001681. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001681

67. Xinhua. Xinhua Headlines: China considers tougher law against counterfeit drugs (2018). Available online at: http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2018-10/23/c_137550957.htm (Accessed May 10, 2025).

68. Shin J. China Cracks Down on Counterfeit and Substandard Drugs (2024). Available online at: https://pharmaboardroom.com/articles/China-cracks-down-on-counterfeit-and-substandard-drugs/ (Accessed May 12, 2025).

69. Huang B, Barber SL, Xu M, and Cheng S. Make up a missed lesson-New policy to ensure the interchangeability of generic drugs in China. Pharmacol Res Perspect. (2017) 5:e00318. doi: 10.1002/prp2.318

70. Staff Reporter. DRAP launches crackdown against counterfeit drugs in Karachi (2024). Available online at: https://www.Pakistantoday.com.pk/2024/01/03/drap-launches-crackdown-against-counterfeit-drugs-in-karachi/ (Accessed May 16, 2025).

71. Pathak R, Gaur V, Sankrityayan H, and Gogtay J. Tackling counterfeit drugs: the challenges and possibilities. Pharmaceut Med. (2023) 37:281–90. doi: 10.1007/s40290-023-00468-w

72. Charani E, Mendelson M, Pallett SJC, Ahmad R, Mpundu M, Mbamalu O, et al. An analysis of existing national action plans for antimicrobial resistance-gaps and opportunities in strategies optimising antibiotic use in human populations. Lancet Glob Health. (2023) 11:e466–e74. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(23)00019-0

73. Interpol. Crackdown on illicit health and counterfeit products identifies 179 suspects in Southern Africa (2021). Available online at: https://www.interpol.int/en/News-and-Events/News/2021/Crackdown-on-illicit-health-and-counterfeit-products-identifies-179-suspects-in-Southern-Africa (Accessed May 12, 2025).

74. Interpol. Pharmaceutical crime: first INTERPOL-AFRIPOL front-line operation sees arrests and seizures across Africa (2022). Available online at: https://www.interpol.int/en/News-and-Events/News/2022/Pharmaceutical-crime-first-INTERPOL-AFRIPOL-front-line-operation-sees-arrests-and-seizures-across-Africa (Accessed May 12, 2025).

75. Interpol. Pharmaceutical crime operations—Pharmaceutical Crime (2022). Available online at: https://www.interpol.int/Crimes/Illicit-goods/Pharmaceutical-crime-operations (Accessed May 13, 2025).

76. Mekonnen BA, Berhanu K, Solomon N, Worku MC, and Anagaw YK. Community pharmacy professionals’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices toward substandard and falsified medicines and associated factors in Bahir Dar City, Northwest Ethiopia. Front Pharmacol. (2025) 16:1523709. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2025.1523709

77. Cadwallader AB, Nallathambi K, and Ching C. Why assuring the quality of antimicrobials is a global imperative. AMA J Ethics. (2024) 26:E472–8. doi: 10.1001/amajethics.2024.472

78. Baldeh AO, Millard C, Pollock AM, and Brhlikova P. Bridging the gap? Local production of medicines on the national essential medicine lists of Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda. J Pharm Policy Pract. (2023) 16:18. doi: 10.1186/s40545-022-00497-x

79. Zanichelli V, Sharland M, Cappello B, Moja L, Getahun H, Pessoa-Silva C, et al. The WHO AWaRe (Access, Watch, Reserve) antibiotic book and prevention of antimicrobial resistance. Bull World Health Organ. (2023) 101:290–6. doi: 10.2471/BLT.22.288614

80. Sharland M, Zanichelli V, Ombajo LA, Bazira J, Cappello B, Chitatanga R, et al. The WHO essential medicines list AWaRe book: from a list to a quality improvement system. Clin Microbiol Infect. (2022) 28:1533–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2022.08.009

81. Saleem Z, Sheikh S, Godman B, Haseeb A, Afzal S, Qamar MU, et al. Increasing the use of the WHO AWaRe system in antibiotic surveillance and stewardship programmes in low- and middle-income countries. JAC-Antimicrob Resist. (2025) 7:dlaf031. doi: 10.1093/jacamr/dlaf031

82. Green A, Lyus R, Ocan M, Pollock AM, and Brhlikova P. Registration of essential medicines in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda: a retrospective analysis. J R Soc Med. (2023) 116:331–42. doi: 10.1177/01410768231181263

83. Obembe TA, Adenipekun AB, Morakinyo OM, and Odebunmi KO. Implications of national tax policy on local pharmaceutical production in a southwestern state Nigeria—qualitative research for the intersection of national pharmaceutical policy on health systems development. BMC Health Serv Res. (2022) 22:264. doi: 10.1186/s12913-022-07579-1

84. Rajab K, Onen S, Nakitto DK, Serwanga A, Mutasaaga J, Manirakiza L, et al. The impact of the increase in import verification fees on local production capacity of selected medicines in Uganda. J Pharm Policy Pract. (2023) 16:51. doi: 10.1186/s40545-023-00552-1

85. Ndagije HB, Kesi DN, Rajab K, Onen S, Serwanga A, Manirakiza L, et al. Cost and availability of selected medicines after implementation of increased import verification fees. BMC Health Serv Res. (2024) 24:25. doi: 10.1186/s12913-023-10433-7

86. Kalungia A and Godman B. Implications of non-prescription antibiotic sales in China. Lancet Infect Dis. (2019) 19:1272–3. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30408-6

87. Reuters. India drug regulator finds counterfeit medicines worth 20 mln rupees in raid (2023). Available online at: https://www.reuters.com/world/India/India-drug-regulator-finds-counterfeit-medicines-worth-20-mln-rupees-raid-2023-08-03/:~:text=India%27s%20drug%20regulator%20recovered%20counterfeit%20medicines%20worth%20more,Kolkata%2C%20the%20federal%20health%20ministry%20said%20on%20Thursday (Accessed May 13, 2025).

88. Sutaria I. Anti-counterfeit pharmaceutical Packaging Market Outlook for (2023 to 2033) (2023). Available online at: https://www.futuremarketinsights.com/reports/anti-counterfeit-pharmaceutical-packaging-market (Accessed May 14, 2025).

89. Yoshida N. Research on the development of methods for detection of substandard and falsified medicines by clarifying their pharmaceutical characteristics using modern technology. Biol Pharm Bull. (2024) 47:878–85. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b23-00749

90. Haji M, Kerbache L, Sheriff KMM, and Al-Ansari T. Critical success factors and traceability technologies for establishing a safe pharmaceutical supply chain. Methods Protoc. (2021) 4:85. doi: 10.3390/mps4040085

91. Bolla AS, Patel AR, and Priefer R. The silent development of counterfeit medications in developing countries—A systematic review of detection technologies. Int J Pharm. (2020) 587:119702. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2020.119702

92. Roxana S, Saeid E, and Peivand B. How radio frequency identification improves pharmaceutical industry: A comprehensive review literature. J Pharm Care. (2016) 3:26–33.

93. Jairoun AA, Al Hemyari SS, Abdulla NM, Shahwan M, Jairoun M, Godman B, et al. Development and validation of a tool to improve community pharmacists’ Surveillance role in the safe dispensing of herbal supplements. Front Pharmacol. (2022) 13. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.916223

94. Kamere N, Rutter V, Munkombwe D, Aywak DA, Muro EP, Kaminyoghe F, et al. Supply-chain factors and antimicrobial stewardship. Bull World Health Organ. (2023) 101:403–11. doi: 10.2471/BLT.22.288650

95. Abdullah S, Saleem Z, and Godman B. Coping with increasing medicine costs through greater adoption of generic prescribing and dispensing in Pakistan as an exemplar country. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. (2024) 24:167–70. doi: 10.1080/14737167.2023.2280802

96. Godman B, Fadare J, Kwon HY, Dias CZ, Kurdi A, Dias Godói IP, et al. Evidence-based public policy making for medicines across countries: findings and implications for the future. J Comp Eff Res. (2021) 10:1019–52. doi: 10.2217/cer-2020-0273

97. MacBride-Stewart S, McTaggart S, Kurdi A, Sneddon J, McBurney S, do Nascimento RCRM, et al. Initiatives and reforms across Scotland in recent years to improve prescribing; findings and global implications of drug prescriptions. Int J Clin Exp Med. (2021) 14:2563–86.

98. Fadare JO, Adeoti AO, Desalu OO, Enwere OO, Makusidi AM, Ogunleye O, et al. The prescribing of generic medicines in Nigeria: knowledge, perceptions and attitudes of physicians. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. (2016) 16:639–50. doi: 10.1586/14737167.2016.1120673

99. Godman B, Massele A, Fadare J, Kwon H-Y, Kurdi A, Kalemeera F, et al. Generic drugs—Essential for the sustainability of healthcare systems with numerous strategies to enhance their use. Pharm Sci And Biomed Anal J. (2021) 4:126.

100. Jamil E, Saleem Z, Godman B, Ullah M, Amir A, Haseeb A, et al. Global variation in antibiotic prescribing guidelines and the implications for decreasing AMR in the future. Front Pharmacol. (2025) 16—2025. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2025.1600787

101. Sharland M, Pulcini C, Harbarth S, Zeng M, Gandra S, Mathur S, et al. Classifying antibiotics in the WHO Essential Medicines List for optimal use-be AWaRe. Lancet Infect Dis. (2018) 18:18–20. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30724-7

102. Falco MF, Meyer JC, Putter SJ, Underwood RS, Nabayiga H, Opanga S, et al. Perceptions of and practical experience with the national surveillance centre in managing medicines availability amongst users within public healthcare facilities in South Africa: findings and implications. Healthcare. (2023) 11:1838. doi: 10.3390/healthcare11131838

103. Saleem Z, Godman B, Cook A, Khan MA, Campbell SM, Seaton RA, et al. Ongoing efforts to improve antimicrobial utilization in hospitals among african countries and implications for the future. Antibiotics. (2022) 11:1824. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics11121824

Keywords: antibiotics, antimicrobial resistance, substandard antibiotics, falsified antibiotics, informal sector, policy initiatives, health authorities, sub-Saharan Africa

Citation: Maluleke TM, Mekonnen BA, Ubaka CM, Paramadhas BDA, Munzhedzi M, Kalungia AC, Hango E, Kumar S, Godman B and Meyer JC (2025) Potential activities to reduce the extent of substandard and falsified antibiotics across Africa and associated antimicrobial resistance. Front. Trop. Dis. 6:1634029. doi: 10.3389/fitd.2025.1634029

Received: 23 May 2025; Accepted: 25 August 2025;

Published: 24 September 2025.

Edited by:

Sylvia Opanga, University of Nairobi, KenyaReviewed by:

Shoaib Ahmad, Punjab Medical College, PakistanGayathri Govindaraju, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, United States

Copyright © 2025 Maluleke, Mekonnen, Ubaka, Paramadhas, Munzhedzi, Kalungia, Hango, Kumar, Godman and Meyer. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Brian Godman, YnJpYW4uZ29kbWFuQHNtdS5hYy56YQ==

†ORCID: Tiyani Milta Maluleke, orcid.org/0000-0001-6437-7198

Biset Asrade Mekonnen, orcid.org/0000-0001-8799-7146

Chukwuemeka Michael Ubaka, orcid.org/0000-0001-7193-2305

Aubrey C. Kalungia, orcid.org/0000-0003-2554-1236

Santosh Kumar, orcid.org/0000-0002-5117-7872

Brian Godman, orcid.org/0000-0001-6539-6972

Johanna C. Meyer, orcid.org/0000-0003-0462-5713

Ester Hango, orcid.org/0000-0002-7112-4049

Bene D. Anand Paramadhas, orcid.org/0000-0002-8204-1417

Mukhethwa Munzhedzi, orcid.org/0000-0003-1082-0881

Tiyani Milta Maluleke1,2†

Tiyani Milta Maluleke1,2† Biset Asrade Mekonnen

Biset Asrade Mekonnen Chukwuemeka Michael Ubaka

Chukwuemeka Michael Ubaka Santosh Kumar

Santosh Kumar Brian Godman

Brian Godman Johanna C. Meyer

Johanna C. Meyer