- 1Department of Animal Health, School of Agricultural Sciences, North-West University, Mmabatho, South Africa

- 2Rabies Reference Laboratory, Agricultural Research Council ARC-Onderstepoort Veterinary Research (OVR), Pretoria, South Africa

- 3Department of Veterinary Tropical Diseases, Faculty of Veterinary Sciences, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

Introduction: Rabies is an important veterinary and public health disease, and causes thousands of human deaths annually in the low and middle-income countries (LMICs). The aim of this study was to determine the rabies virus biotypes associated with cattle rabies by analyzing lyssavirus-infected brain tissues collected between 2008 and 2018 from the North-West province (South Africa).

Methodology: A total of 43 rabies-infected brain tissues were subjected to reverse-transcription PCR of the highly variable glycoprotein gene, and the generated amplicons were sequenced. In addition, 20 cattle rabies viruses were subjected to an indirect immunofluorescent antibody test and their reactivity patterns compared to those from commonly-circulating southern African lyssaviruses.

Results: During the study period (2008–2018), cattle were the most commonly infected host species with rabies virus (42%), followed by domestic dogs (28%), goats (4%), sheep (3%), and a variety of wildlife species including black-backed jackals (13%), yellow mongooses (4%), slender mongooses (3%), duiker (2.1%), honey badgers (1%) and unidentified species (1%). Phylogenetic analysis of the generated nucleotide sequences delineated the rabies viruses into four clades, three belonging to the canid rabies virus biotype. The first clade comprised wildlife, domestic dog and bovine RABVs, and the second and third exclusively jackal and bovine RABVs, linked to dog and jackal RABVs from the commonly dog-endemic regions of South Africa. The fourth clade consisted of cattle RABVs associated with the mongoose rabies biotype. Phylogenetic analyses confirmed very close genetic relationships between dog and jackal RABVs, highlighting the common progenitor and historical introduction of rabies in the country, and cross-species transmission events between domestic and wildlife host species. Antigenic typing, allows us to infer the sources of RABV infection, given that antigenic variants of rabies virus are associated with different rabies cycles and species of terrestrial carnivores in South Africa.

Conclusion: This study highlighted the transmission routes between domestic (dogs) and wildlife (jackals and mongooses) reservoirs and cattle. Both antigenic and genetic typing suggest interactions between livestock and both domestic and wildlife. Vaccination of dogs remains crucial to break rabies transmission cycles and particularly so in the North West of the country.

Introduction

Rabies, one of the oldest diseases documented in medical history, is a fatal and neglected viral zoonosis in South Africa and other countries in disadvantaged communities in Africa and Asia. The disease, highly preventable in both humans and animals, is of major public health concern and an estimated 59,000 human deaths succumb to rabies every year (1), although this estimate is considered a gross underreporting. An increase in human rabies cases has been linked with low public awareness (2). In addition, rabies contributes a huge economic burden in the resource-limited communities of Africa and Asia (3, 4).

Lyssaviruses were initially classified as serotypes (5), later as genotypes (6). At present, there are 18 confirmed Lyssavirus species (7, 8), and two unclassified lyssaviruses, both of bat-origin (9, 10). The members in the Lyssavirus genus are genetically and antigenically distinct, and can be separated into three phylogroups (I-III), that possess different biological and genetic characteristics (11, 12). The current dog rabies cycle in South Africa was introduced from Angola in the late 1940s (13), and later spilled over into wildlife (black-backed jackals and bat-eared foxes), both now confirmed to be wildlife reservoirs for the dog-rabies variant in the northern and western regions of the country, respectively. The RABVs confirmed in cattle in the North West province (South Africa) have not been comprehensively analyzed, although limited antigenic typing data for some cattle RABVs is available (14). In neighboring Limpopo province in the north, the black-backed jackal species (C. mesomelas) is the reservoir for the canid rabies virus biotype, a rabies virus variant indistinguishable from RABVs maintained in dog populations. From time to time, both the dog-rabies and mongoose-rabies variants spill-over into livestock species (15), leading to dead-end infections.

The number of cattle rabies cases in 2014 was observed to be higher than in any other domestic or wildlife animal species confirmed rabies positive from the North West province (16). In addition, the specific sources of these RABVs, as well as the definitive lyssavirus species in cattle, are not well known. Understanding circulating strains of RABV will improve the knowledge of the risk factors associated with RABV infections and the transmission dynamics thereof. And this ultimately may inform policy on control of the disease, thereby reducing the economic losses arising from cattle deaths to rabies. The aim of this study was to genetically and antigenically characterize RABVs of cattle origin from the North West province of South Africa and confirmed between 2008-2018. The specific objectives were to determine the different animal species diagnosed with RABV infection in the North West province of South Africa from 2008 to 2018, establish the rabies biotypes infecting cattle in the North West province by nucleotide sequencing and monoclonal antibody typing, and to determine the phylogenetic relationships of cattle RABVs to improve the transmission dynamics between canine and other host species.

Materials and methods

Study area

In South Africa, the North West Province borders Limpopo in the north-east, Gauteng in the east, Free State in the south-east and Northern Cape in the south-west. It is known as the Platinum Province for the wealth of the metal it has underground. North West province map, showing the municipalities and districts where samples included in this study were collected can be observed in Figure 1. The North West province is geographically located at -26.663859 (latitude) and 25.283 (longitude). The province is divided into four districts of Dr. Kenneth Kaunda, Dr. Ruth Segomotsi Mompati, Ngaka Modiri Molema and Bojanala Platinum. The province has an average rainfall of between 700 mm in the East to <300 mm in the West, and is a key hub for agricultural economic activities. In particular, this province is well known for some of South Africa’s largest cattle herds, found in Stelland near Vryburg in the Dr. Segomotsi Mompati district (17). The North West province is an inland South African province that borders Botswana. The province is predominantly populated by black Africans, with the most widely spoken language being Setswana.

Figure 1. North West province map, showing the municipalities and districts where samples included in this study were collected.

Sample selection

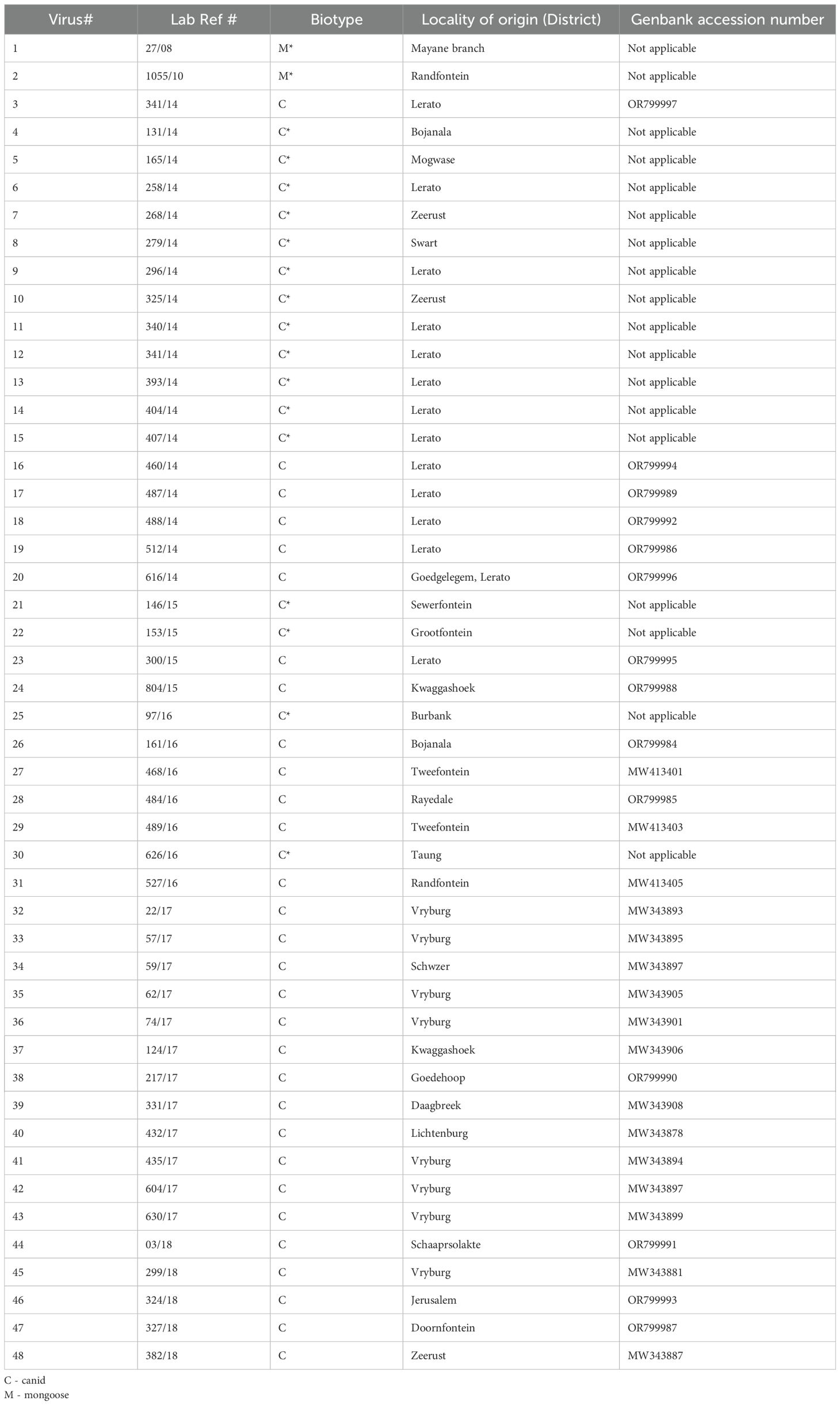

A retrospective cross-sectional study design was applied to establish the rabies virus biotypes associated with cattle rabies exposures in the North West province from 2008 to 2018, using both genetic sequencing and monoclonal antibody typing of rabies viruses. Retrospective data on cattle rabies received from the North-West province were retrieved from historical records kept at the repository of the Agricultural Research Council-Onderstepoort Veterinary Research (ARC-OVR, Pretoria). Brain samples were collected from rabies-suspect animals from the 9 provinces of South Africa as part of the passive national rabies surveillance program of the Department of Agriculture (DoA). The samples were then subjected to the gold standard direct fluorescent antibody test to rule out rabies virus infection. The samples shown to be lyssavirus-infected were kept frozen prior to use. A total of 43 brain tissue samples collected from lyssavirus-infected cattle from different geographical locations in the North West province and associated with rabies virus infections in cattle were subsequently selected for use in this study.

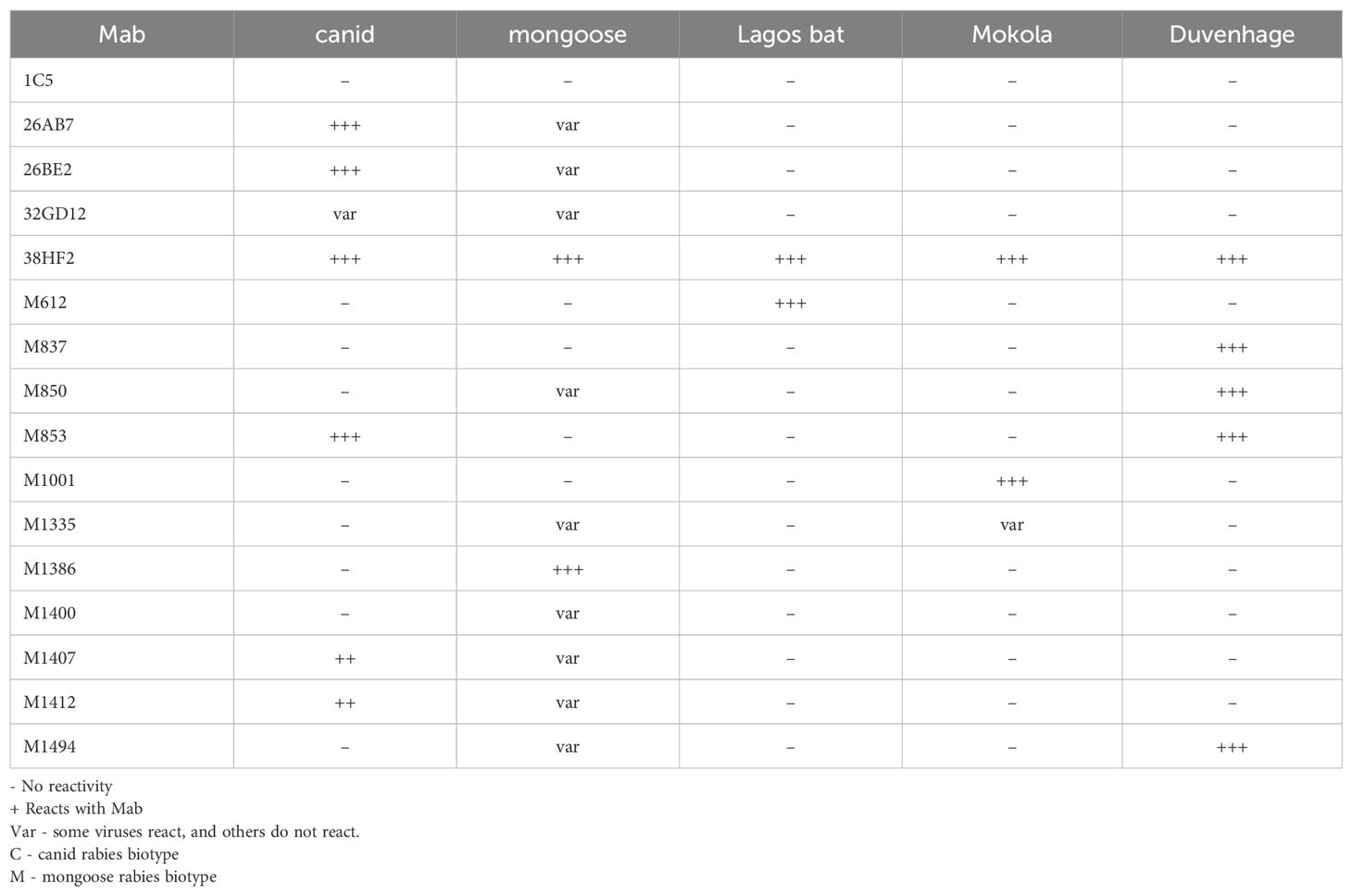

Antigenic typing

A panel of 16 murine monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) capable to discriminate the different southern African Lyssavirus species and antigenic variants were chosen from the mAbs collection of the Centre of Expertise for Rabies of the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (Ottawa, Canada) and given to the Rabies Reference Laboratory at Onderstepoort as a donation (Table 1). The panel included an anti-human adenovirus type-5 mAb (1C5) as a negative control and 15 anti-rabies virus nucleoprotein mAbs, which included a positive control (38HF2) that reacts with all tested lyssaviruses. The lyssavirus positive cattle samples (n=43) were subjected to monoclonal antibody typing and the reactivity patterns observed were recorded as per Table 1 or as described previously (24).

Total RNA extractions

Lyssavirus-infected cattle brain samples (n=43), previously confirmed by the direct fluorescent antibody test, a WHO and WOAH recommended test to diagnose RABV infections on both animal and human central nervous tissues, were selected (Table 2). Subsequently, total RNA extractions were performed on approximately 100 ng of each brain tissue in 1 ml of TRI-sure™ (Bioline, United Kingdom), a ready-to-use reagent for the isolation of RNA, DNA and protein from cells and tissues. The mixture was vigorously mixed with vortexing at 3–500 rpm for approximately 1 minute, and incubated for 5 minutes at room temperature (RT). About 200 µl of molecular grade chloroform (Merck, USA) was added to homogenized brain tissues, thoroughly mixed and incubated for a maximum of 5 minutes. The brain tissue mixture was centrifuged at 13000 rpm for 10 minutes to separate the phases. Half a milliliter of clarified aqueous phase (containing RNA) were transferred to new labeled and sterile tubes and an equal volume of isopropanol was added, incubated for 15 minutes and centrifuged at 13000 rpm for 15 minutes to collect the RNA. The solvent mixture was aspirated without disturbing the RNA pellet, the pellet rinsed with 70% ethanol (in DEPC-treated water) and then air dried for 5 minutes. Approximately 30 µl of water was added to solubilize the RNA pellets at 56 °C for 5 minutes and the RNA concentrations were determined spectrophotometrically. The RNA was stored at -80 °C until required.

RT-PCR and partial genome sequencing

A partial glycoprotein gene and the G-L intergenic region was reverse-transcribed using Protoscript® II reverse transcriptase (New England Biolabs, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (18, 19). Viral cDNAs were synthesized with up to 1 µg of RNA. The RNA was denatured at 65 °C for 5 minutes, snap-cooled on ice, and reverse-transcribed at 42 °C for 1 hour. The reactions were then inactivated at 80 °C for 5 minutes, and immediately stored frozen until needed for amplification. A master mix comprising the following reagents was assembled on ice for DNA amplification for one cDNA: 24.5 μl RNase-Dnase free water, 4 μl dNTP mixture (2.5 mM), 5 μl of 5X reaction buffer, 4 μl each of the G (+) primer and L (–) primers (10 pmol/µl), 3 μl Magnesium chloride (1.5 mM MgCl2) and 0.5 µl Takara Taq™ (Takara Bio, USA) (1.25 units/µl) were added to a sterile 0.2 ml tube and mixed briefly. Five microliters of the respective cDNA template was mixed with the PCR master mix (45 µl), and thermal-cycled at 94 °C for 2 minutes, then subjected to 35 cycles of 94 °C for 50 seconds, 42 °C for 1.30 minutes, 72 °C for 2 minutes and a final extension (72 °C) for 7 minutes. An aliquot of the amplified PCR products together with 1 µl of DNA loading dye (6X) (Thermofischer, Lithuania, (20) along a 100 bp DNA ladder were electrophoresed in 1% ethidium-stained agarose gels and then viewed under UV transillumination. Polymerase chain reaction-generated amplicons were purified using the QIA quick® kit, spin columns (Qiagen, USA), and sequenced bidirectionally at Inqaba Biotechnical Industries (Pty) Ltd. (Pretoria, South Africa) on an ABI Prism 3500XL Genetic Analyzer (Thermo-Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). Sequencing data were retrieved and the forward and reverse reactions compared in order to generate a consensus sequence. All the G-L sequences generated in this study were deposited at the National Centre for Biotechnology and assigned accession numbers: OR99984 - OR99997.

Phylogenetic analysis of nucleotide sequence data

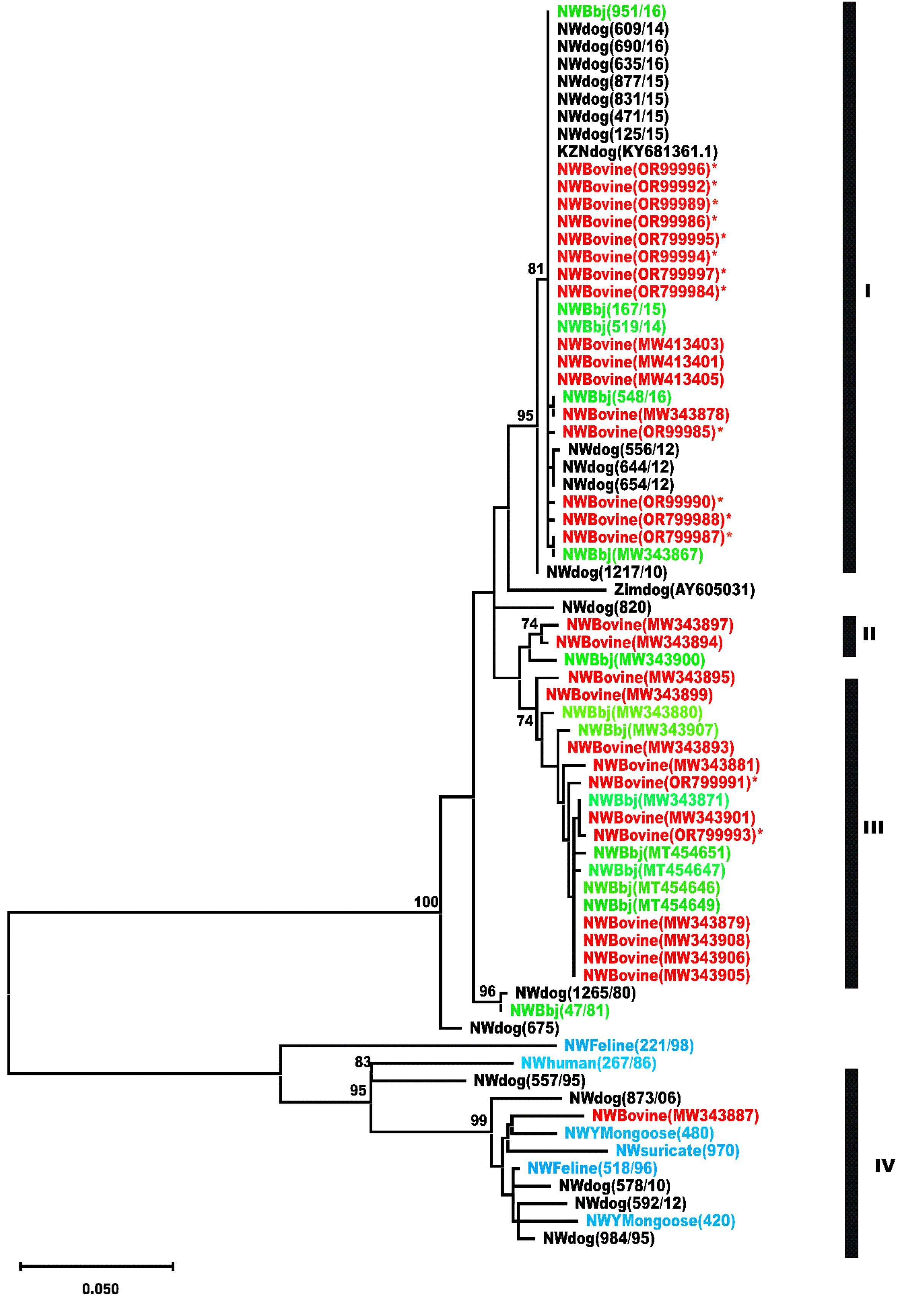

The nucleotide sequences of the amplified partial region of the glycoprotein and the G-L intergenic regions of the RABVs were trimmed to 592 bp, and aligned in MegaX using the Muscle alignment tool for phylogenetic analysis (21). Further, the rabies virus nucleotide sequences (n=57) were retrieved from Genbank and included in the phylogenetic analysis. The Maximum Likelihood (ML) method incorporating the Tamura-Nei model was applied to construct a phylogenetic tree using the MEGA X version 11 (64 bit) software package (22), and a 1000 bootstrap replicates included to estimate the statistical support of the nodes of the phylogenetic tree (23). A total of 71 nucleotide sequences were phylogenetically analyzed with the final data set of 605 nucleotide positions to generate an unrooted ML tree (Figure 2). The sequences generated from the cattle RABVs and analyzed in this investigation are labeled in red and bold with an asterisk (n=14), followed by historically sequenced bovine RABVs highlighted in red (n=16), cats (n=2), black-backed jackals (n=14), dogs (n=21), yellow mongooses (n=2), a suricate (n=1), and a human (n=1) included to construct their evolutionary history and genetic relationships.

Figure 2. Phylogenetic analysis of a partial region of the glycoprotein and G-L intergenic region of bovine RABVs and additional published RABV sequences from dogs and wildlife (black-backed jackals) from the North West and KwaZulu/Natal provinces of South Africa using the Maximum likelihood method (Mega X software). Principal bootstrap support values are shown on the nodes. The horizontal branch lengths are proportional to the similarity of sequences within and between the clusters. Vertical lines are for clarity of the presentation only. The scale bar represents 5 nucleotide substitutions/change per 100 positions.

Ethical approvals

Ethical approvals for this research study were granted by the Agricultural Research Council - Onderstepoort Veterinary Institute (ARC-OVI) Animal Ethics Committee (AEC 23_03), ARC-OVI Biosafety and Biosecurity (IBBC 23-03). An additional approval was granted by the Faculty Committee for Research Ethics-Science of the North West University certificate number FCRE 2023/05/009 (SCI) (FCPS 01) and ethics number NWU 00054-19-A1 were granted. In addition, section 20 approval was granted by the Director of Animal Health of the Department of Agriculture (DoA) under certificate number 12/11/1/1(a)()/6658(HP)).

Results

Rabies diagnosis was confirmed using the DFAT (23) on the brain samples submitted for rabies testing as part of the passive and national surveillance program of the DoA. Approximately 90% of the confirmed cattle brain tissue samples tested for rabies (23) were graded positive from +4 to +1, demonstrating the level of antigen in the smears from 100% (+4) to 25% (+1). The rabies trends from North West province during the study period (2008–2018), demonstrated that RABV infections were confirmed in a variety of domestic and wildlife species (n=292). The rabies-infected species reported in descending order were; cattle (n=120, 42%), followed by domestic dogs (n=78, 27%), black-backed jackals (n=36, 13%), yellow mongooses (n=12, 4%), goats (n=12, 4%), slender mongooses (n=8, 3%), sheep (n=8, 3%), honey badgers (n=2, 1%), duiker (n=2, 1%) and unidentified species (n=4, 1%). The monoclonal antibody typing data analysis revealed that the cattle were infected with canid rabies biotype with the exception of two cases of mongoose rabies biotype (Table 2).

Table 2. Epidemiological information of cattle rabies samples selected for this study for the period 2008-2018 in the North West province.

The phylogenetic analysis showed that the RABVs included in the study were split into four distinct clusters (I), (II), (III) and (IV), supported by high bootstrap values of 95%, 74%, 74% and 95%, and evident of phylogenetic groupings. Clusters I, II and III were composed of RABVs of the dog-rabies variant, whereas cluster IV, represents the mongoose rabies virus variant. Cluster I consisted of RABV sequences originating from black-backed jackals, dogs and cattle, demonstrating the role of both domestic and wildlife host species in transmitting rabies to cattle. Clusters II and III, equally supported by high bootstrap support values and were exclusively composed of RABVs originating from both cattle and black-backed jackals, respectively. Cluster (IV) was composed of RABVs exclusively from wildlife, namely mongooses (n=2), domestic dogs (n=5), one each a feline (n=1), a suricate (n=1), a black-backed jackal (n=1) and a human (n=1), demonstrating spillover of the indigenous rabies virus variant into other wildlife species and domestic dogs. In most cases, notably in the rural communal areas, the high population movement of stray dogs and hunting by wildlife usually leads to cross-species transmission of RABV infection to cattle. Black-backed jackals accounted for 13% of the samples of rabies cases, while domestic dogs accounted for slightly >27% for the period under review.

Discussion

This study aimed to firstly establish the trends of RABV infections in a variety of domestic and wildlife carnivore species for the 2008–2018 period from the North West province. In addition, we intended to genetically and antigenically characterize RABVs associated with cattle infections to establish their rabies virus biotype. Animal rabies cases are on the increase in the North West province, and wildlife host species appear to be more involved (25). In our study for the 2008–2018 period, the North West province reported the second highest bovine rabies cases (n= 294) after the Free State province (data not shown). Cattle were the most RABV-infected animal species in the North West province during the study period with a 42% positivity, just over double the confirmed cases in other animal species such as yellow mongooses, goats, sheep, slender mongooses, honey badgers, duiker and other unknown animal species.

Molecular epidemiological studies play an important role in understanding how pathogens such as RABV spread from an infected host to a spillover host. The phylogenetic analysis illustrated the clustering of the bovine rabies virus nucleotide sequences with those from domestic dogs and jackal species, highlighting the transmission routes and dynamics of RABVs between the two hosts. Using both sequencing of the partial glycoprotein gene and monoclonal antibody (Mab) reactivity patterns, we could assign the RABVs into two categories, canid and mongoose rabies viruses. The Mab typing is an additional typing tool for viral pathogens including RABV and can provide information of the specific lyssavirus species involved in rabies outbreaks and hence complements nucleotide sequence data obtained in such a study (Table 1). What stands out from both data sets is the dominance of canid over mongoose rabies variants in infecting cattle in the North West province.

Rabies is an economically important disease that affects mammalian species, consequently leading to 11,500 livestock losses annually in Africa and Asia (26, 27). In the North West province of South Africa, previous records reported thousands of RABV infections in cattle (28), but the actual economic losses have never been elucidated. Cattle rabies in the southern African region is not a new phenomenon. For instance, in 1887, a widespread rabies outbreak in cattle and small livestock was reported in Namibia, and a retrospective study undertaken in Zimbabwe recorded 1200 cattle deaths (13). However, in Botswana, rabies infections were recorded in over 70% of domestic herbivores (32). In South Africa, the majority of rabies outbreaks have been recorded in the North West, Limpopo, Mpumalanga, Gauteng and Free State provinces (16, 33, 34). In addition, rabies outbreaks in black-backed jackal contributed to cattle rabies infections (35), supporting some of the findings from our study. Indeed, in South Africa, domestic dogs are the major reservoir and vector species involved in transmitting the RABV, although black-backed jackals and bat-eared foxes also maintain rabies cycles (13). In the North West province, twice as many domestic dogs (27%) were diagnosed with RABV in comparison to black-backed jackals (13%) for the study period of 2008 to 2018. In Latin America, rabies causes more cattle deaths than in any other animal species, with the cattle deaths largely attributable to vampire bat rabies infections of bat origin (29–31).

Previous antigenic studies suggested that staining patterns for RABVs of the wildlife infecting animal species in South Africa were either mongoose or canid rabies virus biotype (24). These observations were confirmed by genetic studies and most importantly the two tools provided concordant results on the lyssavirus species involved (13). Although Mab typing of lyssaviruses has been replaced by phylogenetic analysis, antigenic typing may still offer good value. This is primarily because Mab typing of RABVs allows one to distinguish trends of rabies virus dissemination and infer the possible source(s) of infection, as antigenic variants of rabies are associated with different rabies cycles and species of terrestrial carnivores in South Africa and the sub-region. The study of evolutionary relationships (molecular) between animal species using molecular data, such as amino acid or nucleotide sequences, or using distance-based or character-based methods, is now commonplace in many veterinary diagnostic laboratories globally (36). The molecular technique investigating the presence of RABV using a conventional PCR assay in decomposed samples did not generate the expected amplicon due to prolonged and inappropriate storage of brain tissue samples (16, 37). The phylogenetic relationships of cattle viruses determined in the current study confirmed the transmission dynamics and routes between domestic (dogs) and wildlife (jackals) and cattle (dead-end hosts). Our phylogenetic analysis delineated the rabies viruses obtained from cattle into the canid and the mongoose RABV biotypes, previously shown as two epidemiologically separate lineages of rabies virus in southern Africa through antigenic studies. The results obtained from the phylogenetic analysis demonstrated that domestic dogs, blacked jackals, and cattle viruses were grouped into one clade (I), highlighting a very close genetic relationship between domestic and wildlife rabies cycles (35). The close genetic relationship further highlights the transmission dynamics between (domestic) dogs and (wildlife) black-backed jackals considering that cattle are indeed dead-end hosts. Considering that both the domestic dog and black-backed jackals are the maintenance host species for the canid rabies biotype, it is evident that the source of the canid rabies biotype in cattle in the North West province originated from either a domestic dog, or black-backed jackal or domestic dog-black-backed jackal cycle. In the North West, the Madikwe game reserve wild dog outbreak (Lycaon pictus) reported in 2014 was also related to black-backed jackal rabies infections (16, 38) highlighting wildlife interactions. Additionally, wildlife and domestic dog cycles pose health threats to the public by transmitting the rabies virus (15). In Zimbabwe, for instance, rabid jackals travel long distances and, in the process, interact with other wildlife hosts, livestock or even domestic dogs, thus transmitting the rabies virus infection to any susceptible host (15, 39). Similar to what we found here, a previous study also confirmed that the canid rabies biotype maintained in dogs and black backed jackals in Zimbabwe as well as in South Africa shared a common ancestor and supported historical introduction of the disease into the sub-region (40). Furthermore, our study also included RABV nucleotide sequences that were demonstrated to be very closely related to those from dogs in KwaZulu/Natal province. A more recent molecular epidemiological study targeting the G-L intergenic region of the RABV from the North West of South Africa (25) demonstrated a clear genetic association between cattle rabies viruses and dog viruses on the one hand and wildlife on the other. In the North West province of South Africa, the rabies cycles appear to be linked to other rabies cycles in Limpopo, KZN, Gauteng, Northern Cape and Free State provinces, as well as in Zimbabwe and Botswana (25). The high number of reported cattle rabies cases may be due to the fact that the North West and Limpopo provinces have both human/domestic/wildlife interface (15, 34, 35), promoting interactions between cattle and both dogs and jackal species.

Conclusions

The maintenance of rabies in sylvatic species such as the black-backed jackals and bat-eared foxes and the cyclical pattern of outbreaks in wildlife carnivore species compounded by the presence of immunologically naïve dogs and bovine populations in the North West province make the elimination and control of rabies extremely difficult. The North West province could therefore benefit from the use of oral rabies vaccines such as RaboralG as a practical measure to control rabies in jackal species. The identification of RABV variants through the use of Mab panels may not be able to provide the appropriate resolution compared to molecular assays. Hence, comprehensive genomic analysis, albeit expensive, will be useful to understand rabies transmission dynamics and further to explore transmission routes between domestic and wildlife species. Furthermore, both Mab typing and genetic sequencing of circulating RABVs can provide additional information to infer rabies hotspots that may inform policy on targeted rabies control. The preliminary genetic data presented here demonstrate that bovines definitely interact with both domestic and wildlife carnivore species, resulting in confirmation of both canid and mongoose variants in bovine CNS samples submitted for rabies diagnosis. It is, therefore, crucial to break the rabies transmission cycles by vaccinating both domestic dogs and black-backed jackal species, thus limiting the spread to cattle.

a. The study was linked to several and key limitations: Only 43 rabies positive cattle brain samples were included in the study from the already confirmed cases. This non-random, convenience-based selection may have introduced sampling bias, and reduced the representativeness across all the districts in the province as well as seasons.

b. Our study focused on sequencing a partial region of the glycoprotein and the G-L intergenic region rather than full genome sequencing. Integrating full genome sequencing of rabies viruses could have provided new insights into rabies virus evolution and epidemiology and consequently expanded our understanding of the transmission dynamics of the disease and evolutionary pressures associated different host species. In addition, full genome sequencing of rabies viruses may have improved the resolution of phylogenetic clustering, or fine scale evolutionary and transmission differences. For instance, the dog-to-cattle or jackal-cattle transmissions were implied based on direct transmission routes and genetic proximity, and could have been impirically confirmed through full genome sequencing.

c. Spatial mapping, animal movements, and ecological interactions were not analysed, and therefore limited our ability to interpret cross-species transmission dynamics.

d. The use of archived samples is important to understand hirotical events, but RNA could have been degraded due to prolonged or inconsistent storage conditions, possibly affecting amplification success and sensitivity of the molecular analyses.

e. While monoclonal antibody typing was well executed, our limited antigen panel may not have fully differentiated among the newly emerging or regional lyssavirus variants.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/supplementary material.

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by Ethical approvals for this research study were granted by the Agricultural Research Council - Onderstepoort Veterinary Institute (ARC-OVI) Animal Ethics Committee (AEC 23_03), ARC-OVI Biosafety and Biosecurity (IBBC 23-03). An additional approval was granted by the Faculty Committee for Research Ethics-Science of the North West University certificate number FCRE 2023/05/009 (SCI) (FCPS 01) and ethics number NWU 00054-19-A1 were granted. In addition, section 20 approval was granted by the Director of Animal Health of the Department of Agriculture (DoA) under certificate number 12/11/1/1(a)()/6658(HP)). The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

OK: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft. EN: Data curation, Formal analysis, Software, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. CS: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NM: Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. MS: Conceptualization, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. World Organization for Animal Health Rabies Reference Laboratory (Onderstepoort).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Hampson K, Coudeville L, Lembo T, Sambo M, Kieffer A, Attlan M, et al. Global Alliance for Rabies Control Partners for Rabies Prevention. Estimating the global burden of endemic canine rabies. PloS Negl Trop Dis. (2015) 9:e0003709. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003709

2. Claassen DD, Odendaal L, Sabeta CT, Fosgate GT, Mohale DK, Williams JH, et al. Diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of immunohistochemistry for the detection of rabies virus in domestic and wild animals in South Africa. J Vet Diagn Invest. (2023) 35:236–45. doi: 10.1177/10406387231154537

3. Rupprecht CE, Mani RS, Mshelbwala PP, Recuenco SE, and Ward MP. Rabies in the tropics. Curr Trop Med Rep. (2022) 9:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s40475-022-00257-6

4. Coetzer A, Sabeta CT, Markotter W, Rupprecht CE, and Nel LH. Comparison of biotinylated monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies in an evaluation of a direct rapid immunohistochemical test for the routine diagnosis of rabies in southern africa. PloS Negl Trop Dis. (2014) 8:e3189. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003189

5. Bourhy H, Sureau P, and Tordo N. From rabies to rabies-related viruses. Vet Microbiol. (1990) 23:115–28. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(90)90141-h

6. Bourhy H, Kissi B, and Tordo N. Molecular diversity of the Lyssavirus genus. Virology. (1993) 194:70–81. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1236

7. Coertse J, Grobler CS, Sabeta CT, Seamark EC, Kearney T, Paweska JT, et al. Lyssaviruses in insectivorous bats, South Africa, 2003–2018, Vol. 26. (2020) 26:3056.

8. Walker PJ, Siddell SG, Lefkowitz EJ, Mushegian AR, Adriaenssens EM, Alfenas-Zerbini P, et al. Recent changes to virus taxonomy ratified by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Arch Virol. (2022) 167:2429–40. doi: 10.1007/s00705-022-05516-5

9. Grobler CS, Coertse J, and Markotter W. Complete genome sequence of matlo bat lyssavirus. Microbiol Resource Announcements. (2021) 10:10.1128/mra. doi: 10.1128/MRA.00241-21

10. Viljoen N, Weyer J, Coertse J, and Markotter W. Evaluation of taxonomic characteristics of matlo and phala bat rabies-related lyssaviruses identified in South Africa. Viruses. (2023) 15:2047. doi: 10.3390/v15102047

11. Badrane H, Bahloul C, Perrin P, and Tordo N. Evidence of two lyssavirus phylogroups with distinct pathogenicity and immunogenicity. J Virol. (2001) 75:3268–76. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.7.3268-3276.2001

12. Shipley R. Defining the antigenic requirements for pan-lyssavirus neutralisation. University of Sussex, Brighton and Hove, England. (2022).

13. Swanepoel R, Barnard B, Meredith C, Bishop G, Bruckner G, Foggin C, et al. Rabies in southern africa. Onderstepoort J Veterinary Res. (1993) 60:325–5.

14. Onderstepoort records. Onderstepoort Veterinary Reasearch Records 2024, Pretoria, South Africa (2024).

15. Zulu G, Sabeta C, and Nel L. Molecular epidemiology of rabies: Focus on domestic dogs (Canis familiaris) and black-backed jackals (Canis mesomelas) from northern South Africa. Virus Res. (2009) 140:71–8. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2008.11.004

16. Sabeta CT, Janse van Rensburg DD, Phahladira B, Mohale D, and Harrison-White RF. Esterhuyzen, C. et al., 2018. Rabies of canid biotype in wilddog (Lycaon pictus) and spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta) in Madikwe Game Reserve, South Africa in 2014–2015: Diagnosis, possible origins and implications for control. J South Afr Veterinary Assoc. (2018) 89:1–13. doi: 10.4102/jsava.v89i0.1517

17. Omotoso AB and Omotayo AO. Behavioral intentions towards climate-smart practices and rural farmer’s food-nutrition security: A micro economic-level evidence. (2023). doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-3449441/v1

18. von Teichman BF, Thomson GR, Meredith CD, and Nel LH. Molecular epidemiology of rabies virus in South Africa: evidence for two distinct virus groups. J Gen Virol. (1995) 76:73–82. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-1-73

19. Sacramento D, Bourhy H, and Tordo N. PCR technique as an alternative method for diagnosis and molecular epidemiology of rabies virus. Mol Cell Probes. (1991) 5:229–40. doi: 10.1016/0890-8508(91)90045-l

20. Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, and Tamura K. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol. (2018) 35:1547–9. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy096

21. Tamura K, Nei M, and Kumar S. Prospects for inferring very large phylogenies by using the neighbor-joining method. Proc Natl Acad Sci. (2004) 101:11030–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404206101

22. Hillis DM and Bull JJ. An empirical test of bootstrapping as a method for assessing confidence in phylogenetic analysis. Systematic Biol. (1993) 42:182–92. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/42.2.182

23. Dean DJ, Abelseth MK, and Atanasiu P. The fluorescent antibody test. In: Meslin F-X, Kaplan MM, and Koprowski H, editors. Laboratory techniques in rabies. World Health Organization, Geneva (1996). p. 88–9.

24. Ngoepe E, Sabeta C, Fehlner-Gardiner C, and Wandeler A. Antigenic characterisation of lyssaviruses in South Africa. Onderstepoort J Veterinary Res. (2014) 81:1–9. doi: 10.4102/ojvr.v81i1.711

25. Malan AJ, Coetzer A, Sabeta CT, and Nel LH. The epidemiological interface of sylvatic and dog rabies in the northwest province of South Africa. Trop Med Infect Dis. (2022) 7:90. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed7060090

26. Knobel DL, Cleaveland S, Coleman PG, Fèvre EM, Meltzer MI, Miranda ME, et al. Re-evaluating the burden of rabies in Africa and Asia. Bull World Health Organ. (2005) 83:360–8.

27. Koeppel KN, van Schalkwyk OL, and Thompson PN. Patterns of rabies cases in South Africa between 1993 and 2019, including the role of wildlife. Transboundary Emerging Dis. (2022) 69:836–48. doi: 10.1111/tbed.14080

28. Bishop G, Durrheim D, Kloeck P, Godlonton J, Bingham J, Speare R, et al. Guide for the medical, veterinary and allied professions. Republic of South Africa: Department of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries (2010).

29. Hutter SE, Käsbohrer A, González SLF, León B, Brugger K, Baldi M, et al. Assessing changing weather and the El Niño Southern Oscillation impacts on cattle rabies outbreaks and mortality in Costa Rica (1985–2016). BMC veterinary Res. (2018) 14:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12917-018-1588-8

30. Lee DN, Papeş M, and Van Den Bussche RA. Present and potential future distribution of common vampire bats in the Americas and the associated risk to cattle. (2012) 7:e42466. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042466

31. Fanelli A, Rocha F, Awada L, Soto PC, Mapitse N, and Tizzani P. Evolution of rabies in South America and inter-species dynamics (2009–2018). Trop Med Infect Dis. (2021) 6:98.

32. Ditsele B. The epidemiology of Rabies in domestic ruminants in Botswana. Murdoch University, Perth, Australia (2016).

33. Malan A, Coetzer A, Bosch C, Wright N, and Nel L. A perspective of the epidemiology of rabies in South Africa, 1998–2019. Trop Med Infect Dis. (2024) 9:122. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed9060122

34. Mogano K, Sabeta CT, Suzuki T, Makita K, and Chirima GJ. Patterns of animal rabies prevalence in northern South Africa between 1998 and 2022. Trop Med Infect Dis. (2024) 9:27. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed9010027

35. Ngoepe E, Chirima J, Mohale D, Mogano K, Suzuki T, Makita K, et al. Rabies outbreak in black-backed jackals (Canis mesomelas), South Africa, 2016. Epidemiol Infection. (2022) 150:1–42.

36. Ngoepe CE, Sabeta C, and Nel L. The spread of canine rabies into the Free State province of South Africa: A molecular epidemiological characterization. Virus Res. (2009) 142:175–80. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2009.02.012

37. McElhinney LM, Marston DA, Brookes SM, and Fooks AR. Effects of carcass decomposition on rabies virus infectivity and detection. J Virological Methods. (2014) 207:110–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2014.06.024

38. Mogano K, Suzuki T, Mohale D, Phahladira B, Ngoepe E, Kamata Y, et al. Spatio-temporal epidemiology of animal and human rabies in northern South Africa between 1998 and 2017. PloS Negl Trop Dis. (2022) 16:e0010464. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0010464

39. Bingham J, Foggin CM, Wandeler AI, and Hill F. The epidemiology of rabies in Zimbabwe. 2. Rabies in jackals (Canis adustus and Canis mesomelas). Onderstepoort J Vet Res. (1999) 66:11–23.

Keywords: mongoose rabies biotype, canid rabies biotype, antigenic, genetic, South Africa

Citation: Khoane OA, Ngoepe EC, Sabeta CT, Mphuti N and Syakalima M (2025) Genetic and antigenic characterization of rabies viruses reveals transmission to cattle from both domestic and wildlife species in the North West province, South Africa. Front. Trop. Dis. 6:1706731. doi: 10.3389/fitd.2025.1706731

Received: 16 September 2025; Accepted: 19 November 2025; Revised: 06 November 2025;

Published: 09 December 2025.

Edited by:

Nobuo Saito, Nagasaki University, JapanReviewed by:

Raul Alejandro Alegria, University of Chile, ChileChiaka Anumudu, University of Ibadan, Nigeria

Copyright © 2025 Khoane, Ngoepe, Sabeta, Mphuti and Syakalima. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Claude Taurai Sabeta, Y2xhdWRlLnNhYmV0YUB1cC5hYy56YQ==

†Present address: Michelo Syakalima, School Veterinary Medicine, University of Zambia, Lusaka, Zambia

Onkemetse Antoinette Khoane1

Onkemetse Antoinette Khoane1 Claude Taurai Sabeta

Claude Taurai Sabeta