- 1SunPork Group, Eagle Farm, QLD, Australia

- 2Animal Welfare Science Centre, Faculty of Science, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia

Societal attitudes suggest low support for confinement housing in livestock farming, such as the farrowing crate. The attitudes of stockpersons working in these systems are yet to be understood but should be prioritised as their human-animal interactions have significant effects on animal welfare. The aim of this investigation was to explore the attitudes of stockpeople employed on pig farms with experience working in both free-farrowing and farrowing crate systems, and to better understand the contributing factors that shape these attitudes. An anonymous survey was conducted across four pig breeder farms with both Maternity Rings (MR) and farrowing crates (FC) installed. A total of 86 stockpeople volunteered to participate. The survey consisted of an opinion-based rating of sow welfare that considered four specific behaviours, and two attitude-based questionnaires. The composite score of sow welfare was higher in a MR when compared to a FC (39.8 ± 0.87 versus 28.0 ± 0.87, p < 0.05), regardless of attitude towards working with sows in different lactation housing systems. Stockpeople that believed FC systems would always be necessary were more likely to avoid interactions with difficult pigs (r(84) = 0.327, p = 0.005), and more likely to rate piglet welfare as more important than sow welfare (r(84) = 0.380, p = 0.001). In contrast, stockpeople that were confident in their abilities and understandings of sow behaviour were more likely to rate the sows welfare higher in a MR (r(84) = 0.339, p = 0.002) and believed that it provided an environment that enabled the sow to better interact with her piglets (r(77) = 0.434, p < 0.001). Stockpersons that were more likely to interact with pigs (r(84) = 0.322, p = 0.011) and were more satisfied with their job (β = 0.341, p = 0.003) were more likely to rate sow welfare higher in a MR. Overall, stockpeople rated sow welfare higher in a MR in comparison to a FC. The main driver of negative attitudes towards a MR appeared to be a lack of understanding of sow behaviour. If we can develop ways to modify stockperson behaviour to improve sow and piglet welfare outcomes, we have a better chance of introducing alternative farrowing systems.

1 Introduction

Farrowing crates were introduced in the 1960’s (1) with the intention of reducing live-born piglet mortality as they allowed for control over sow postural changes, while providing greater efficiency and safety to stockpeople. While the farrowing crate has provided benefits for piglet survival, it does impose physical restrictions impacting sow welfare. There are two periods when the confinement of the sow within a farrowing crate has high welfare constraints (i) prior to farrowing when the sow has an intrinsic need to build a nest and (ii) as lactation proceeds when the sow begins to wean her litter.

A significant body of research has been directed towards alternatives to the farrowing crate that address the welfare issues sows encounter, as well as the higher live-born piglet mortality in free-farrowing systems (2–4). This research has looked at various design aspects affecting sow and piglet behaviour in these free-farrowing systems to improve the live-pig mortality. Whilst the design of free-farrowing pens is a key factor impacting production performance, the role of the stockperson is also critical in how the sow and piglets are managed, and this has received little attention.

Several studies have quantified the views of the general public and have found that confinement housing such as the farrowing crate have low societal support (5), with consumer preference for provision of more ‘natural’ living conditions (6–8). In contrast people with links to agriculture are more likely to have a positive attitude towards a farrowing crate (5). However, the attitudes of the stockperson working daily with animals housed in these farrowing systems, whether they be farrowing crates or free-farrowing systems, requires further investigation.

Interactions between intensively farmed animals and the stockpeople responsible for their care have significant effects on animal health, welfare and productivity (9–12). The quality of these human-animal interactions is dependent on the stockperson’s behaviour towards the animal (13, 14). According to the Theory of Planned Behaviour (15), understanding a particular attitude can lead to a path of change in human behaviour. While attitudes are dependent on an individual’s behavioural, normative and control beliefs, there are numerous studies which describe the positive impact that training can have on changing attitudes and the subsequent behaviour of stockpeople (9, 16–20). It is this attitudinal shift that improves interactions between stockpeople and animals, increasing welfare and production (11, 21–26). Given this, the attitudes of stockpeople that work with pigs in farrowing and lactation in free-farrowing systems should be better understood.

The Maternity Ring (MR) system was developed as a free-farrowing alternative to conventional farrowing crates that, unlike other commercially available options, preserved space similar to that of a crate, while providing the sow the ability to turn around before, during and after farrowing. Plush et al. (27) has demonstrated that the MR farrowing system was able to improve the welfare of the sow during farrowing and lactation. The aim of this study was to quantify the attitudes of stockpeople employed on pig farms with experience working with the MR and farrowing crate systems, and to better understand the contributing factors that shape these attitudes.

2 Materials and methods

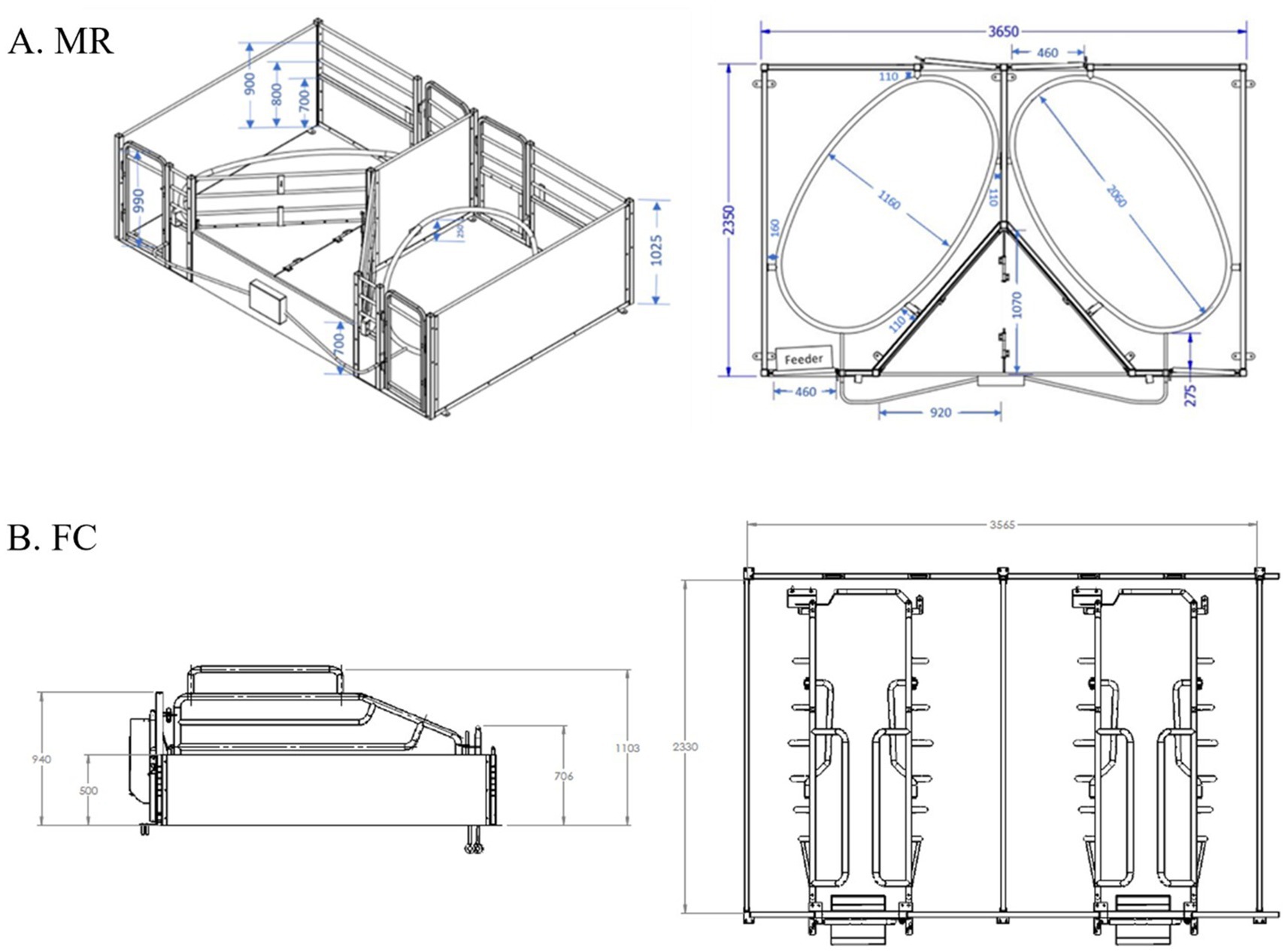

Ethics clearance for research with human subjects was obtained via The University of Melbourne’s Human Ethics Advisory Group (Ethics ID: 2022–25,237–35,354-4). The survey was conducted at four South Australian farms that had both Maternity Rings (MR) and farrowing crates (FC) with farm 1 n = 160 MR and 30 FC, farm 2 n = 80 MR and 620 FC, farm 3 n = 160 MR and 680 FC and farm 4 n = 120 MR and 1,480 FC. The MR was a close-confinement free system 1,800 mm in width by 2,350 mm in length with a ring installed on the diagonal with dimensions 1,160 mm in width and 2,060 in length and height of 250 mm from flooring [Figure 1; (27)]. The FC was 1,783 mm in width by 2,330 mm in length with a crate installed parallel to the external dividers measuring 720 mm in width and 2,330 mm in length which restricted the sows movement.

Figure 1. Dimensions of key design features of the (A) Maternity Ring (MR) and (B) farrowing crate [FC; (27)].

Prior to the presentation of the survey, participants were given a plain language statement (i.e., an explanatory statement outlining the research aims), advised that participation was entirely voluntary and that they could withdraw at any time if so desired, and then written consent was sought and obtained. A total of 86 from the 110 stockpeople working across these farms volunteered to participate in this study. The survey was delivered in a classroom presentation style, where the lead researcher displayed each question and its associated Likert scale on a projector, while reading each question aloud. This allowed participants to clarify anything they were uncertain of and for the researcher to follow up any questions for clarification. Although the questionnaire was delivered in groups, participants completed the questionnaire individually with no group discussion of answers taking place. The completion of the survey took between 30 to 60 min, depending on the number of clarifying questions asked. The survey was made up of a opinion-based assessment of sow welfare and two questionnaires.

2.1 Opinion-based assessment of sow welfare

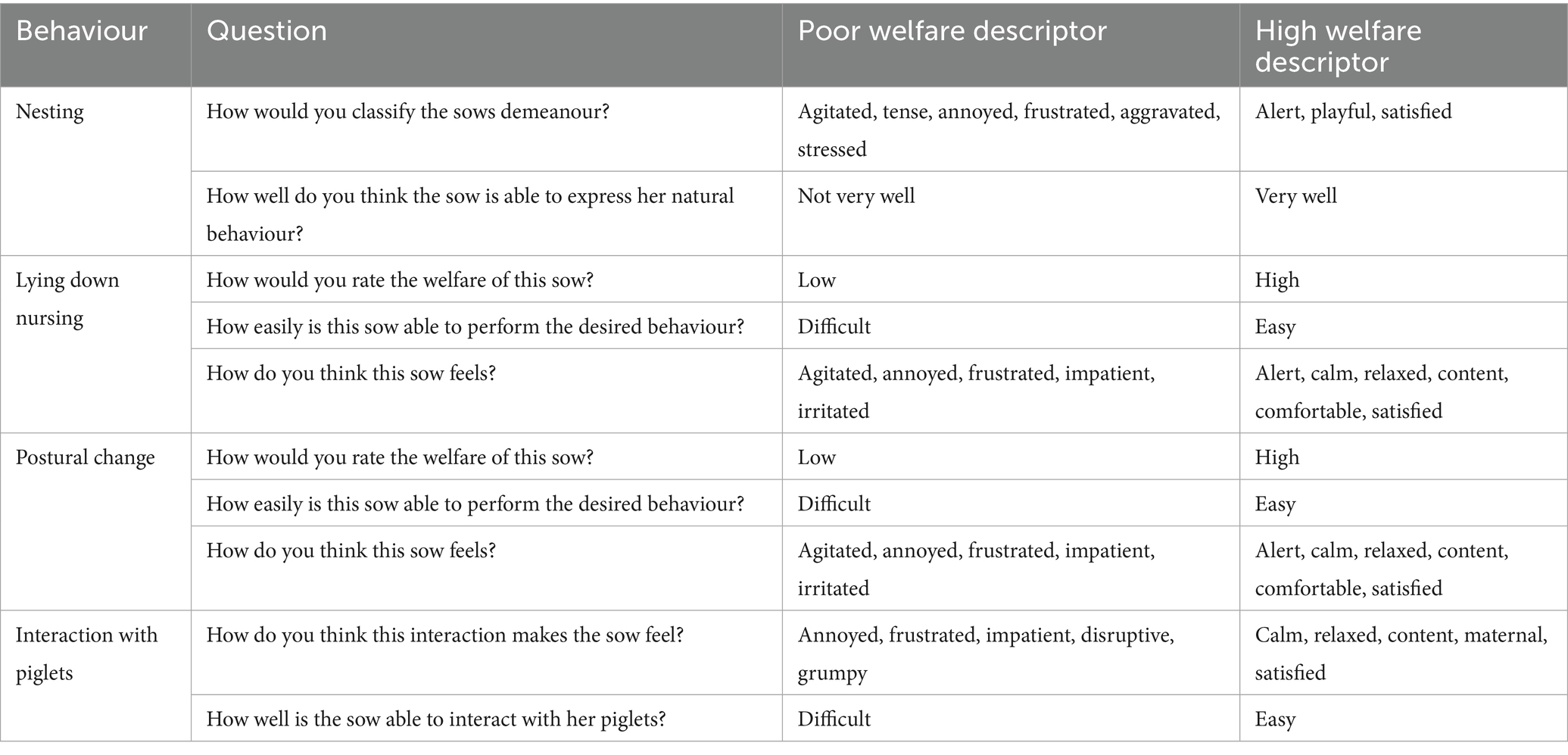

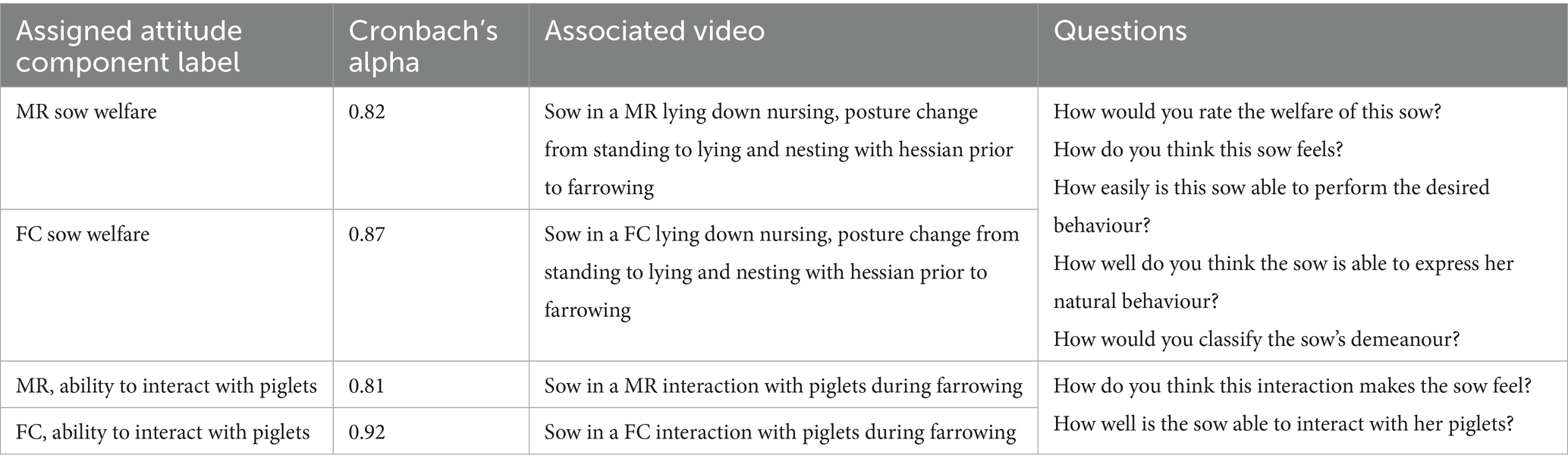

Welfare was scored by playing the participants eight short videos of a sow performing the four behaviours listed in Table 1 in both a FC and MR. Stockpeople were asked to use their experience and understanding of pig behaviour to respond to a series of questions to define the perceived welfare state of the sow using the video as a reference. Videos from both FC and MR sows were randomly selected from a pre-existing catalogue that contained footage collected 18 h prior to farrowing and 4 h on day 5 of lactation and scanned to the first time the listed behaviour (Table 1) was observed. Using a five-point Likert scale, stockpeople were asked to indicate their level of agreement with the list of terms (e.g., score 1 = strongly agree with one or more poor welfare descriptor, 5 = strongly agree with one or more high welfare descriptor listed in Table 1). The scores for each behaviour were then summed to give a composite sow welfare assessment, with a maximum score of 50 representing the highest welfare outcome.

2.2 Questionnaires

Two questionnaires were used to accurately capture stockperson attitudes and opinions towards working with sows in MR and FC systems (included in Supplementary material). The first questionnaire focused on stockperson attitudes, and the second aimed to capture attitudes towards working with pigs in different housing systems. The questionnaires were adapted from previous work conducted in livestock [(see 28–31)]. Using a five-point Likert scale, stockpeople were asked to indicate their level of agreement to the statements, the level of importance or the perceived difficulty of performing an activity (e.g., score 1 = disagree/not at all important/not difficult to score, 5 = strongly agree/very important/very difficult). Questions were framed as both positive and negative, with responses recoded so that a high score indicated that participant held a positive attitude towards working with pigs. Several statements on a specific topic were used to measure consistent beliefs, which allowed the identification of a person’s attitude towards the specific topic (32).

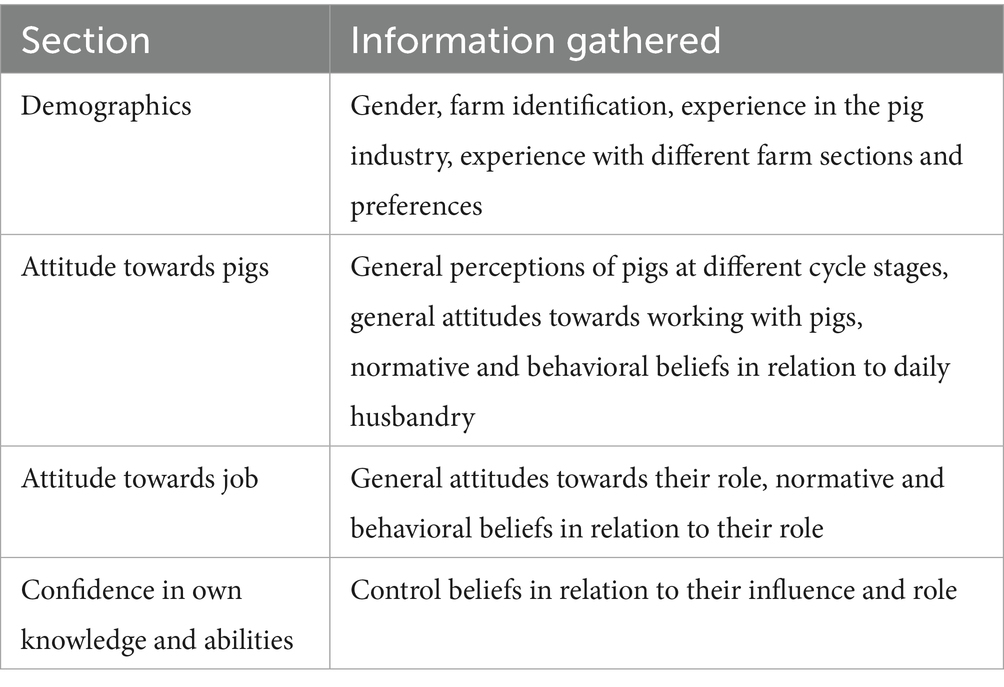

The first attitude questionnaire involved a total of 47 questions and was adapted to target attitudes towards working with pigs, husbandry practices, and assessing the participants overall confidence and knowledge of pig behaviour. The sections of the questionnaire are reported in Table 2.

The second questionnaire was opinion-based, consisting of 29 questions around the participants’ attitudes to working with sows in MR or FC systems. Again, several statements on a specific topic were used to measure consistent beliefs, which allowed the identification of a person’s attitude towards a specific topic (32).

2.3 Statistical analysis

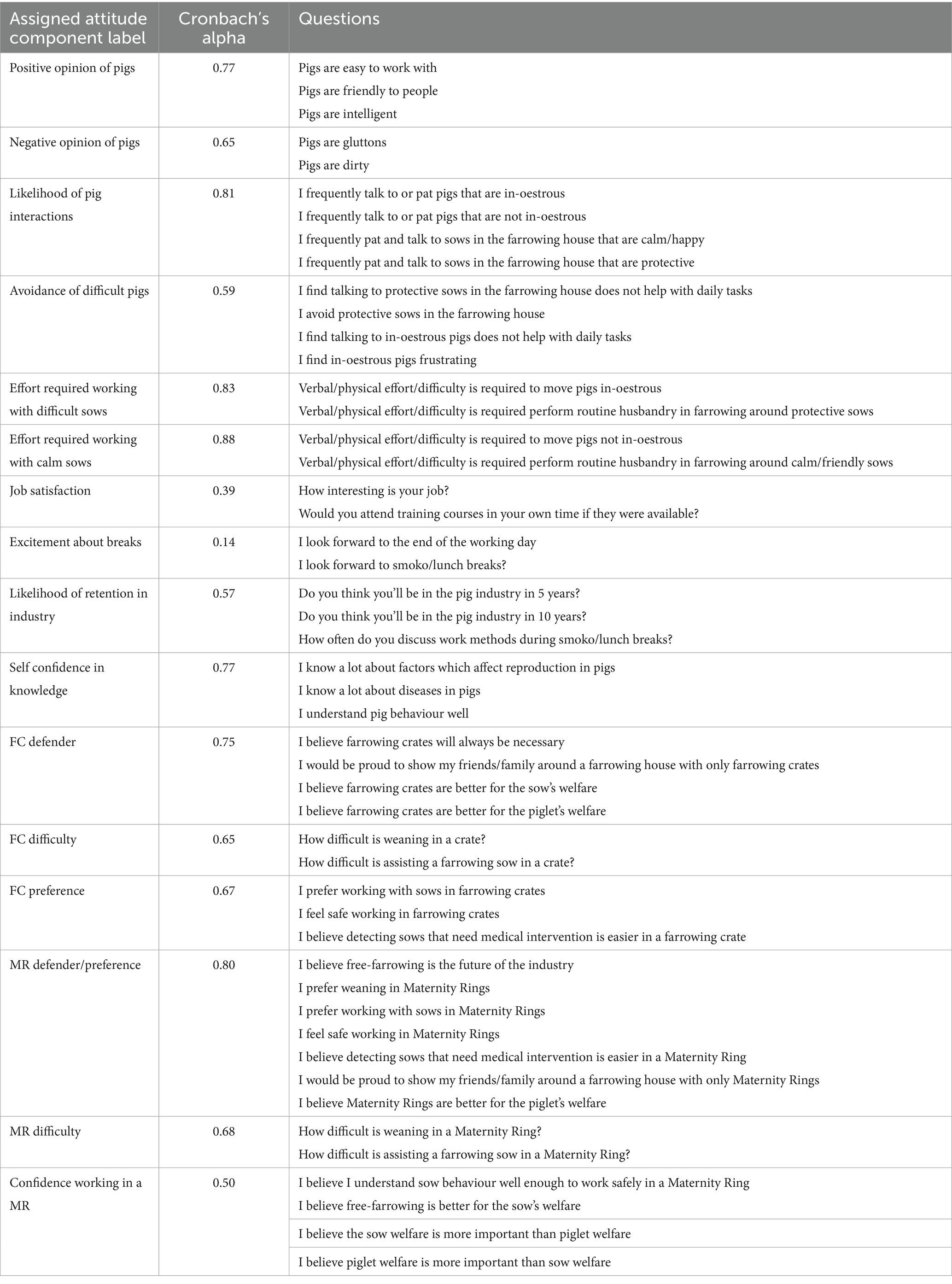

All data were analysed in SPSS (v28 IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) with p < 0.05 achieving significance and p < 0.10 a trend. The impact of farrowing accommodation type on composite opinion-based sow welfare assessment was analysed using linear regression, with the contribution of each of the four individual behaviours (nesting, lying, changing posture and interacting with piglets) using ordinal regression. A Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was carried out, using a correlation matrix on the composite opinion-based sow welfare score, with two components that related to farrowing accommodation type created. Survey data were analysed using PCA, followed by an Oblimin rotation, to identify commonalities amongst the survey items, with Cronbach’s alpha presented as a measure of internal consistency demonstrating how closely related the questions were as a group. Attitude components were assigned labels that reflected the attitude items which formed the components. The suitability of the data for the analyses was assessed using criteria outlined by Pallant (33); the correlation matrix coefficients were all above the required 0.3, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) values exceeded the recommended value of 0.6, and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity reached statistical significance. Questions that were established as belonging to a common underlying component were then summed to produce a composite score for that component. Scale reliabilities were measured using Cronbach’s α coefficients with an α > = 0.70 as the criterion for acceptable reliability (34). Questions were included in a scale if their loading on the relevant component exceeded 0.33 (35) and if, on the basis of face validity, they could be summarized by just one construct. Correlations between composite variables identified from PCA on the demographics, attitudes towards pigs, attitudes towards job, confidence in own knowledge and abilities, and their opinions of MR vs. FC was conducted using Pearsons product moment correlations. Separate stepwise multiple linear regressions were used to identify those demographic variables that predicted each of the behaviours of interest reported in the first questionnaire (see Table 3).

Table 3. Components from the questionnaires grouped into composite scores, a high score indicating a strong agreement to the statements.

The opinion-based sow welfare scoring of sows in MR or FC was subject to the same analyses as the previous questionnaires with components presented in Table 4.

Table 4. Components from the opinion-based sow welfare assessment grouped into composite scores, a high score indicating a more positive response to the question.

3 Results

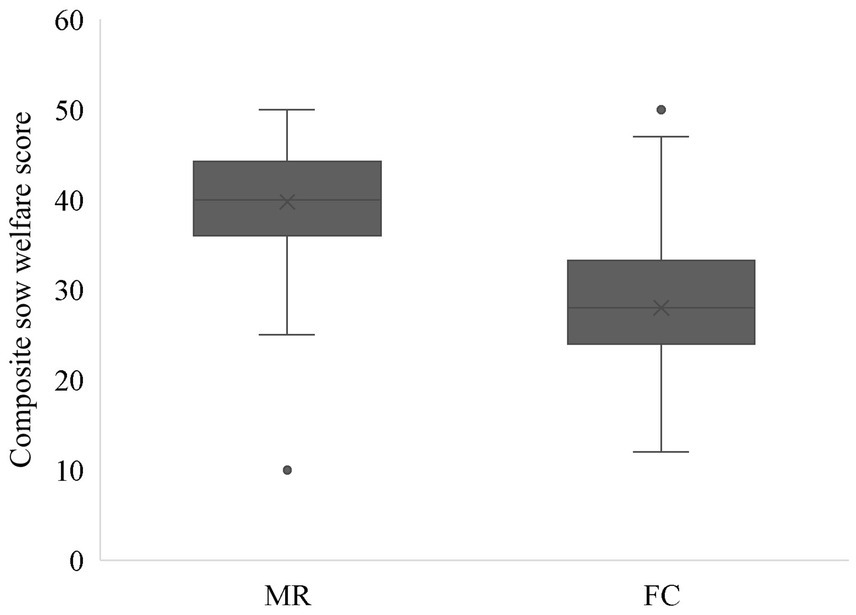

Participants average length of experience working with pigs was 9.0 ± 1.04 years, 62.8% of the participants were male (n = 54), 33.7% female (n = 29) and 3.5% of the participants declined to answer (n = 3). Overall, stockperson opinion of sow welfare was 39.8 ± 0.87 in MR and 28.0 ± 0.87 in FC (Figure 2; p < 0.001). The sow being housed in a FC was associated with a lower welfare score for nesting (odds ratio 0.277 (95% CI 0.156–0.496), Wald χ2(1) = 18.747, p < 0.001), lying (odds ratio 0.258 (95% CI 0.143–0.157), Wald χ2(1) = 20.375, p < 0.001), changing posture (odds ratio 0.080 (95% CI 0.041–0.157), Wald χ2(1) = 53.414, p < 0.001) and interacting with piglets (odds ratio 0.110 (95% CI 0.055–0.205), Wald χ2(1) = 45.136, p < 0.001).

Figure 2. Mean (x) ± SEM opinion-based assessment of sow welfare using four specific behaviours (nesting, lying, changing posture and interacting with piglets) when housed in either a MR or a FC p < 0.001.

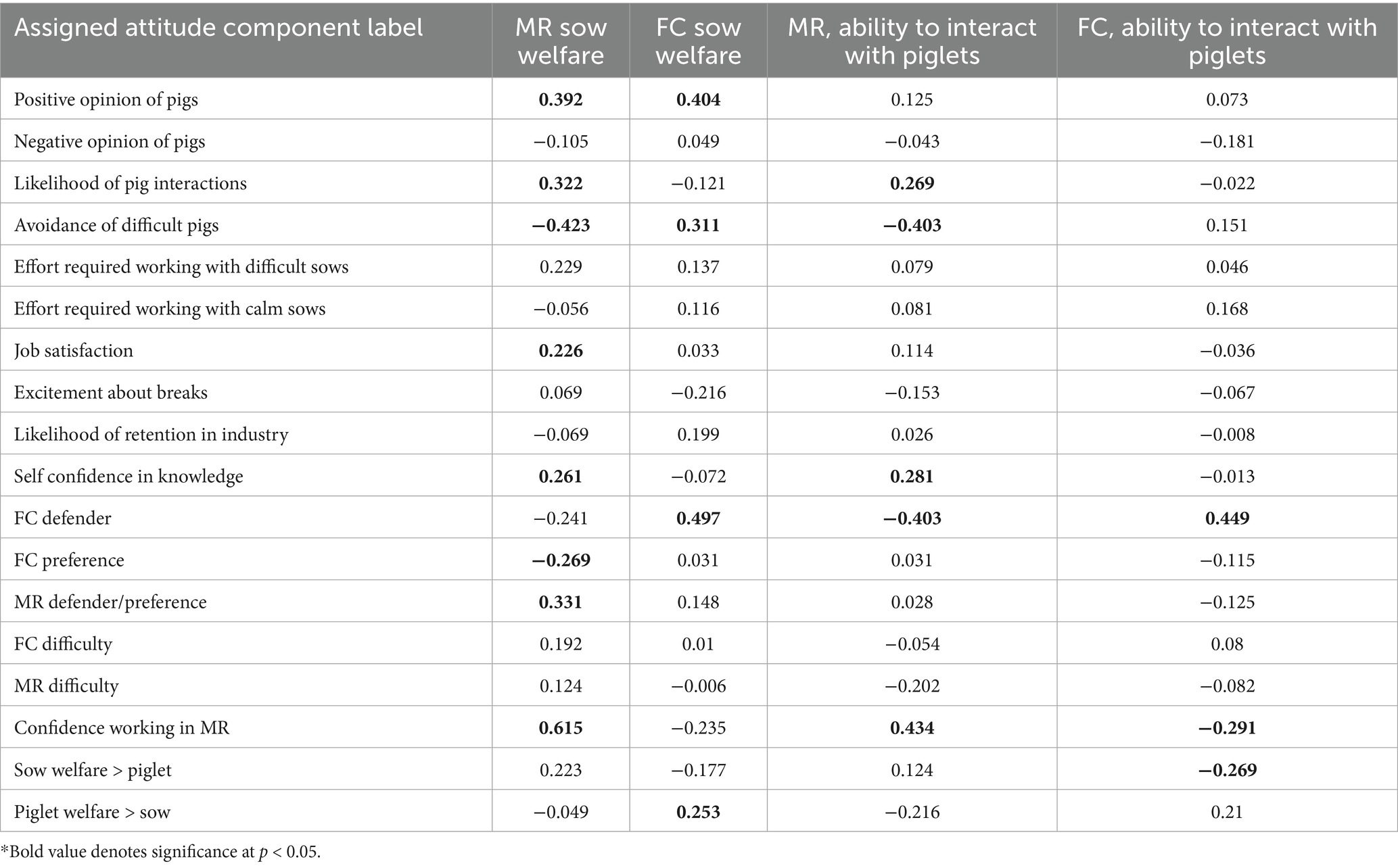

Relationships between opinion-based component scoring of sow welfare and stockpersons attitudes and opinions surveys are reported in Table 5 and were in the low to moderate range. The component label MR sow welfare was positively correlated with positive opinions of pigs, the likelihood of interactions with pigs, their job satisfaction, self confidence in their own knowledge, how confident they were and whether they preferred working in a MR. A negative relationship between this same label and likely to avoid interactions with difficult pigs and preferred working with crated sows was also established. The component label FC sow welfare was positively correlated with positive opinions of pigs, likely to avoid interactions with difficult pigs, FC would always be necessary and piglet welfare was more important than sow welfare.

Table 5. Pearsons’s correlation coefficients between opinion-based sow welfare components and stockpersons attitudes and opinions surveys*.

The way a participant scored a sow’s ability to interact with her piglets in a MR and how they perceived this interaction made the sow feel, was positively correlated with the likelihood of that person interacting with pigs, their self confidence in their own knowledge and their confidence in working in a MR system. Participants that were more likely to avoid interactions with difficult pigs and believed FC would always be necessary, were more likely to give a lower score for a sows ability to interact with her piglets in a MR and believed that this interaction was not satisfying for the sow (Table 5). How a participant scored a sow’s ability to interact with her piglets in a FC and how this interaction made her feel, was positively correlated with their self confidence in their own knowledge. Participants that were more likely to score the welfare effect of this interaction as higher were also less confident in their own knowledge and less likely to rate the sow’s welfare as more important than the piglets welfare.

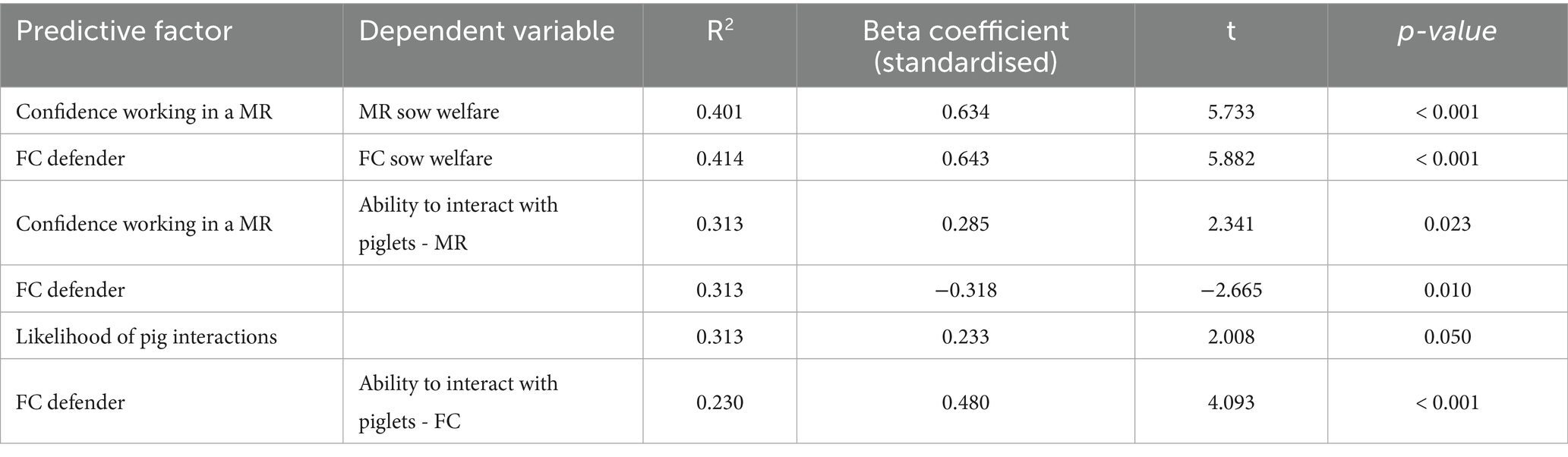

When all composite variables for both attitudes and opinions surveys were entered into a linear regression model with the component label MR sow welfare as the dependent variable, one variable was predictive of this preference (Confidence working in a MR) and accounted for 40.1% of its variance (Table 6). Stockpeople that believed they understood sow behaviour well enough to safely work in a MR had a higher MR sow welfare score. When all composite variables for the attitudes and opinions surveys were entered into a linear regression model with the component label FC sow welfare as the dependent variable, one variable was predictive of this preference (FC defender) and accounted for 41.4% of its variance. Stockpeople that believed farrowing crates will always be necessary had a higher FC sow welfare score.

Table 6. Linear regression with the predictive factor of composite variables for stockpersons attitudes and opinions survey and dependent variable of opinion-based sow welfare score.

When all composite variables for both attitudes and opinions survey were entered into a linear regression model with the component label ‘Ability to interact with piglets – MR’ as the dependent variable, three variables were predictive of this preference (Confidence working in MR, Likelihood of pig interactions and negatively with FC defender) and accounted for 31.3% of its variance. Stockpeople that believed they understood sow behaviour well enough to work safely in a MR and that were more likely to interact with pigs in general rated the sow’s ability to interact with her piglets and the positive effect this had on the sow’s welfare as higher. In comparison, stockpeople that believed that farrowing crates would always be necessary were more likely to rate the sow’s ability to interact with her piglets in a MR as lower and that this had a diminished effect on her welfare. When all composite variables for both attitudes and opinions survey were entered into a linear regression model with the component label Ability to interact with piglets – FC as the dependent variable, one variable was predictive of this preference (FC defender) and accounted for 23.0% of its variance. Stockpeople that believed FC would always be necessary were more likely to rate the sow’s ability to interact with her piglets in a FC as higher, with this having a positive effect on her welfare.

When all composite variables for both questionnaires were entered into a linear regression model with ‘MR defender/preference’ as the dependent variable, one variable was predictive of this preference (Job satisfaction) and accounted for 11.7% of its variance (R2 = 0.114, t = 2.86). Stockpeople that were more satisfied with their job were more supportive of the MR (β = 0.341, p = 0.003). When all composite variables for both questionnaires were entered into a linear regression model with ‘FC defender’ as the dependent variable, no variable was predictive of this attitude.

4 Discussion

Free-farrowing systems when compared to FC require a higher level of human interaction with the sow (36), therefore, the experiences of the stockperson working in these systems should be explored. The first step in investigating this is to better understand the attitudes and opinions of stockpeople that have experience working in both systems. Using opinion-based sow welfare assessment, stockpeople in the current study ranked the welfare of sows higher in a free-farrowing system (MR) when compared to a confined housing system (FC). The results suggest several key attitudes and beliefs influenced this assessment. Stockpeople that viewed sow welfare positively in a MR were confident in their knowledge of sow behaviour and felt this contributed to a safer working environment compared to those that viewed sow welfare positively in a FC and deemed crates as being indispensable for pig farming. A lack of confidence working in free-farrowing systems, stemming from a lack of understanding of sow behaviour appears to be a barrier to staff support for these systems. Given this finding, the development of a targeted training program may prove beneficial in supporting positive attitudes towards free-farrowing systems in the future.

In the current investigation, stockpeople were shown video footage of sows in a MR and FC and concentrated on four specific behaviours. These behaviours were selected from literature as being divergent in free-farrowing and farrowing crate systems and impacting welfare. The ability of the sow to nest and interact with piglets (27), and ease with which the sow can change posture and nurse her litter (37) are key behaviours which are inhibited or impaired in farrowing crate systems. The opinion-based assessment rated welfare higher when a sow was housed in a MR compared to a FC both individually and when all behaviours were compiled into a composite score. Recognising the importance of these behaviours to sow welfare may lead to more positive stockperson attitudes towards free-farrowing systems. The primary aim of the experiment was to examine stockperson attitudes towards the two lactation housing systems, and so an opinion-based assessment of sow welfare was developed to be included in the survey whilst not distracting from other included questions. The score did consider qualitative behavioural assessment (QBA) and used descriptors of emotions and groupings reported previously (38). Whilst the current investigation did apply similar descriptors of emotion, QBA was too complex to be included in the survey. This methodology still remains to be applied to periparturient sows (39) and so should be explored in further work.

While it is well known that education can help to improve stockperson attitude towards the animals they tend (24), the current study is the first to examine how stockperson attitudes to different housing systems were related to their perceptions of sow welfare in these housing systems. Stockpeople that scored a sow higher for welfare in a MR believed they were confident enough in their understanding of pig behaviour to work safely in these systems. This finding suggests that transition to any alternative husbandry system could be increased if we improve stockperson understanding of animal behaviour, and in so doing shifting attitudes towards safety. Stockpeople with positive attitudes towards the use of farrowing crates (FC defenders) were more likely to rate the welfare of a sow in a farrowing crate as high, to avoid interactions with difficult pigs and were less confident in their own knowledge of sow behaviour. Control beliefs refer to how a person’s perception of their ability affects their actions (15), with a person’s doubt in their ability to work safely alongside free-farrowing sows being a limiting factor to the acceptance of the MR. A simple way to overcome this fear could be addressed by the sharing of knowledge through targeted training programs. There are numerous examples describing the positive impact training can play on an attitudinal shift (9, 16–20). Training has been proven to improve positive stockperson behaviour, leading to an increase in both welfare and production outcomes for the animal (11, 21–26).

There has never been a widely adopted training program dedicated to the farrowing sow, nor the stockpeople that work in these systems. Stockpeople on pig farms do work with unconfined sows, commonly during mating and gestation when exhibited behaviours are vastly different to those observed during the periparturient period. The use of confinement in the form of a FC has prevented the adequate expression of some of these behaviours, in addition to reducing the level of animal contact the stockperson encounters. Free-farrowing facilitates behaviours and human-animal interaction that even highly experienced stockpeople working in crated systems will have unlikely encountered. The risk to stockpersons working with unconfined sows at farrowing and during lactation stem from maternal aggression, whereby the sow is reactive towards humans, standing quickly, vocalizing and may launch and bite (40). More generalised training programs that focus on ‘pig behaviour’ will need refocusing towards farrowing and lactating sow behaviour to reduce fear and increase confidence in stockpeople working with unconfined sows.

The second key area that requires attention to shift the attitudes of stockpeople towards supporting free-farrowing is safety. When stockpeople were comfortable in their knowledge of sow behaviour, they felt safe working in the MR system. Stockperson safety is or should be the first consideration in the adoption process of free-farrowing systems, however there is little scientific literature addressing safety in free-farrowing systems. Baxter et al. (2) discusses key design elements that can help to improve stockperson safety, however most of the scientific literature relates to temporary confinement systems and not free-farrowing accommodation. Despite the lack of literature some European countries (Sweden and Germany) have put in place additional regulations regarding stockperson safety specifically around farrowing sows, whilst this is a step in the right direction these decisions have been largely based on case studies and interviews (2), not scientific outcomes. Training programs that focus on stockperson safety during pig transport have been developed after the identification that animal contact is the leading cause of injury on farms (41). A priority should also be a better understanding of the key stockperson behaviours and human-animal interactions which affect sow welfare in free-farrowing systems. Once these key behaviours are identified, the relevant stockperson attitudes can be targeted to increase or reduce these behaviours. As seen in the use of ProHand programs, this is also likely to improve stockperson job satisfaction and work motivation (21). A better understanding of what stockpeople feel contributes to a safe working environment in free-farrowing (outside understanding sow behaviour discussed above) requires further evaluation. Identifying the risks to stockpeople that could result in injury in free-farrowing systems should be systematically assessed and minimised. The implementation of a structured safety assessment procedure in free-farrowing would not only ensure stockpeople feel and are indeed safe but could also have residual benefits for animal welfare, performance and job satisfaction.

Stockpeople that were more satisfied in their job were more likely to rate sow welfare as higher in a MR. These were stockpeople who were more likely to undertake training in their own time if provided and found their job interesting. It is well understood that job satisfaction of stockpeople results in higher standards of animal welfare (25, 32, 42), and that the provision of training increases their likelihood to remain in the job (17). Therefore, stockpeople who are more engaged in their work and are eager to learn appear to be more open-minded about future industry changes, such as free-farrowing, and are more likely to be retained in the industry. Given that those termed FC defenders deemed crates as a necessity, specialized training programs are an essential and proven way of modifying attitudes and may help to improve attitudes towards free-farrowing systems. Farrowing crate defenders had less confidence in their ability to work safely in this environment, highlighting a lack of knowledge or experience working with free-farrowing sows. Stockpeople who scored sow welfare as high in a FC believed that piglet welfare was more important than sow welfare, this is likely due to the education that has occurred around the introduction of the FC and its ability to improve piglet safety. Whilst the farrowing crate has provided benefits for piglet survival, it does impose physical restrictions impacting sow welfare that result in socially unsustainable practices (3, 5, 27). The development of future training programs should therefore have a dual focus of not just how to work safely in a free-farrowing environment, but also to educate stockpeople on the reasons why as an industry there is a need to move towards systems that provide improved welfare and allow the animals we care for to create ‘a life worth living’.

The results of this study suggest that there is a fear of working in free-farrowing systems that stem from a lack of experience and knowledge of maternal sow behaviour. Stockpeople that viewed sow welfare in a MR more positively were confident in their knowledge of sow behaviour and felt this contributed to a safer working environment, whilst those that supported sow welfare in a FC believed the crate was, and would remain, an essential part of pig farming. The development of a free-farrowing training program, focused on educating stockpeople on not just how to work in these environments, but why they are beneficial for the sow has the potential to aid in their acceptance and the ability to improve job satisfaction and stockperson retention. This will enable greater engagement in the issue of sow and piglet welfare around farrowing and lactation and prepare stockpeople with increased confidence in their own abilities.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Human Ethics Team, The University of Melbourne. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

LS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KP: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. DL: Writing – review & editing. LH: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. DD’S: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. RB: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded in part by DAFF Science and Innovation Award.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the SunPork Farms employees that participated in this work.

Conflict of interest

The Maternity Ring is a patented design (Innovation Patent # 2017101428) held by CHM Alliance Pty Ltd., a subsidiary company of the SunPork Group. LS, KP, DL, DD’S and RB are employees of the SunPork Group.

The remaining author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fvets.2025.1579263/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Robertson, JB, Laird, R, Hall, JKS, Forsyth, RJ, Thomson, JM, and Walker-Love, J. A comparison of two indoor farrowing systems for sows. Anim Sci. (1966) 8:171–8. doi: 10.1017/S0003356100034553

2. Baxter, EM, Moustsen, VA, Goumon, S, Illmann, G, and Edwards, SA. Transitioning from crates to free farrowing: a roadmap to navigate key decisions. Front Vet Sci. (2022) 9:998192. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.998192

3. Glencorse, D, Plush, KJ, Hazel, S, D’Souza, DN, and Hebart, M. Impact of non-confinement accommodation on farrowing performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis of farrowing crates versus pens. Animals. (2019) 9:957. doi: 10.3390/ani9110957

4. Goumon, S, Illmann, G, Moustsen, VA, Baxter, EM, and Edwards, SA. Review of temporary crating of farrowing and lactating sows. Front Vet Sci. (2022) 9:811810. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.811810

5. Vandresen, B, and Hötzel, MJ. Pets as family and pigs in crates: public attitudes towards farrowing crates. Appl Anim Behav Sci. (2021) 236:105254. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2021.105254

6. Bergstra, TJ, Gremmen, B, and Stassen, EN. Moral values and attitudes toward Dutch sow husbandry. J Agric Environ Ethics. (2015) 28:375–401. doi: 10.1007/s10806-015-9539-x

7. Boogaard, BK, Boekhorst, LJS, Oosting, SJ, and Sørensen, JT. Socio-cultural sustainability of pig production: citizen perceptions in the Netherlands and Denmark. Livest Sci. (2011) 140:189–200. doi: 10.1016/j.livsci.2011.03.028

8. Ryan, EB, Fraser, D, and Weary, DM. Public attitudes to housing systems for pregnant pigs. PLoS One. (2015) 10:e0141878. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141878

9. Coleman, GJ, McGregor, M, Hemsworth, PH, Boyce, J, and Dowling, S. The relationship between beliefs, attitudes and observed behaviours of abattoir personnel in the pig industry. Appl Anim Behav Sci. (2003) 82:189–200. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1591(03)00057-1

10. Gocsik, É, Lansink, AGJMO, and Saatkamp, HW. Mid-term financial impact of animal welfare improvements in Dutch broiler production. Poult Sci. (2013) 92:3314–29. doi: 10.3382/ps.2013-03221

11. Sinclair, M, Zito, S, and Phillips, CJC. The impact of stakeholders’ roles within the livestock industry on their attitudes to livestock welfare in southeast and East Asia. Animals. (2017) 7:6. doi: 10.3390/ani7020006

12. Waiblinger, S, Boivin, X, Pedersen, V, Tosi, MV, Janczak, AM, Visser, EK, et al. Assessing the human–animal relationship in farmed species: a critical review. Appl Anim Behav Sci. (2006) 101:185–242. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2006.02.001

13. Borgen, SO, and Skarstad, GA. Norwegian pig farmers' motivations for improving animal welfare. Br Food J. (2007) 109:891–905. doi: 10.1108/00070700710835705

14. Breuer, K, Hemsworth, PH, Barnett, JL, Matthews, LR, and Coleman, GJ. Behavioural response to humans and the productivity of commercial dairy cows. Appl Anim Behav Sci. (2000) 66:273–88. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1591(99)00097-0

15. Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. (1991) 50:179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

16. Ceballos, MC, Sant'Anna, AC, Boivin, X, de Oliveira Costa, F, Carvalhal, MVL, and da Costa, MP. Impact of good practices of handling training on beef cattle welfare and stockpeople attitudes and behaviors. Livest Sci. (2018) 216:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.livsci.2018.06.019

17. Coleman, GJ, Hemsworth, PH, Hay, M, and Cox, M. Modifying stockperson attitudes and behaviour towards pigs at a large commercial farm. Appl Anim Behav Sci. (2000) 66:11–20. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1591(99)00073-8

18. Crawford, SM. Improving the attitudes and behavior of stockpersons toward pigs and the subsequent influence on animal behavior and production characteristics of commercial finishing pigs in Ohio. Columbus, OH, United States: The Ohio State University (2011).

19. Descovich, K, Li, X, Sinclair, M, Wang, Y, and Phillips, CJC. The effect of animal welfare training on the knowledge and attitudes of abattoir stakeholders in China. Animals. (2019) 9:989. doi: 10.3390/ani9110989

20. Leon, AF, Sanchez, JA, and Romero, MH. Association between attitude and empathy with the quality of human-livestock interactions. Animals. (2020) 10:1304. doi: 10.3390/ani10081304

21. Coleman, GJ, and Hemsworth, PH. Training to improve stockperson beliefs and behaviour towards livestock enhances welfare and productivity. Rev Sci Tech. (2014) 33:131–7. doi: 10.20506/rst.33.1.2257

22. Hemsworth, PH, Barnett, JL, Coleman, GJ, and Hansen, C. A study of the relationships between the attitudinal and behavioural profiles of stockpersons and the level of fear of humans and reproductive performance of commercial pigs. Appl Anim Behav Sci. (1989) 23:301–14. doi: 10.1016/0168-1591(89)90099-3

23. Hemsworth, PH, and Coleman, GJ. A model of stockperson-animal interactions and their implications for animals In: PH Hemsworth and GJ Coleman, editors. Human-livestock interactions. (CABI, Wallingford, UK: The Stockperson and the Productivity and Welfare of Intensively Farmed Animals). (2011) 91–106.

24. Hemsworth, PH, Coleman, GJ, and Barnett, JL. Improving the attitude and behaviour of stockpersons towards pigs and the consequences on the behaviour and reproductive performance of commercial pigs. Appl Anim Behav Sci. (1994) 39:349–62. doi: 10.1016/0168-1591(94)90168-6

25. Hemsworth, PH, Coleman, GJ, Barnett, JL, Borg, S, and Dowling, S. The effects of cognitive behavioral intervention on the attitude and behavior of stockpersons and the behavior and productivity of commercial dairy cows. J Anim Sci. (2002) 80:68–78. doi: 10.2527/2002.80168x

26. Munoz, CA, Coleman, GJ, Hemsworth, PH, Campbell, AJD, and Doyle, RE. Positive attitudes, positive outcomes: the relationship between farmer attitudes, management behaviour and sheep welfare. PLoS One. (2019) 14:e0220455. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0220455

27. Plush, K, Lines, D, Staveley, L, D’Souza, D, and van Barneveld, R. A five domains assessment of sow welfare in a novel free farrowing system. Font Anim Sci. (2024) 11:1339947. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2024.1339947

28. Coleman, G, Jongman, E, Greenfield, L, and Hemsworth, P. Farmer and public attitudes toward lamb finishing systems. J Appl Anim Welf Sci. (2016) 19:198–209. doi: 10.1080/10888705.2015.1127766

29. Coleman, G, Rohlf, V, Toukhsati, S, and Blache, D. Public attitudes predict community behaviours relevant to the pork industry. Anim Prod Sci. (2017) 58:416–23. doi: 10.1071/AN16776

30. Coleman, G, and Toukhsati, S. Consumer attitudes and behaviour relevant to the red meat industry. Meat and Livestock Australia Limited: North Sydney, NSW (2006).

31. Hemsworth, L, Rice, M, Hemsworth, P, and Coleman, G. Telephone survey versus panel survey samples assessing knowledge, attitudes and behavior regarding animal welfare in the red meat industry in Australia. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:581928. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.581928

32. Hemsworth, PH, and Coleman, GJ. Human-animal interactions and animal productivity and welfare In: Human-livestock interactions: The stockperson and the productivity and welfare of intensively farmed animals. 2nd ed (2011). 47–83.

33. Pallant, J. SPSS survival manual McGraw-hill education (UK). Maidenhead: Open University Press (2013).

34. DeVellis, RF. Scale development: theory and applications. J Int Acad Res. (2003) 10:23–41. doi: 10.1177/109821409301400212

35. Tabachnick, BG, and Fidell, LS. Using multivariate statistics. 5th ed. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon/Pearson Education (2007).

36. Guy, JH, Cain, PJ, Seddon, YM, Baxter, EM, and Edwards, SA. Economic evaluation of high welfare indoor farrowing systems for pigs. Anim Welfare UFAWJ. (2012) 21:19–24. doi: 10.7120/096272812X13345905673520

37. Nowland, TL, van Wettere, WHEJ, and Plush, KJ. Allowing sows to farrow unconfined has positive implications for sow and piglet welfare. Appl Anim Behav Sci. (2019) 221:104872. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2019.104872

38. Wemelsfelder, F, Hunter, EA, Mendl, MT, and Lawrence, AB. The spontaneous qualitative assessment of behavioural expressions in pigs: first explorations of a novel methodology for integrative animal welfare measurement. Appl Anim Behav Sci. (2000) 67:193–215. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1591(99)00093-3

39. Vandresen, B, Chou, JY, and Hötzel, MJ. How is pig welfare assessed in studies on farrowing housing systems? A systematic review. Appl Anim Behav Sci. (2024) 275:106298. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2024.106298

40. Marchant, JN. Piglet- and stockperson-directed sow aggression after farrowing and the relationship with a pre-farrowing, human approach test. Appl Anim Behav Sci. (2002) 75:115–32. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1591(01)00170-8

41. Langley, RL, and Morrow, WEM. Livestock handling—minimizing worker injuries. J Agromedicine. (2010) 15:226–35. doi: 10.1080/1059924X.2010.486327

Keywords: stockperson, maternity ring, attitude, welfare, farrowing

Citation: Staveley LM, Plush KJ, Lines DS, Hemsworth LM, D’Souza DN and van Barneveld RJ (2025) Stockperson attitudes towards Maternity Rings and farrowing crates. Front. Vet. Sci. 12:1579263. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2025.1579263

Edited by:

Emma M. Baxter, Scotland’s Rural College, United KingdomReviewed by:

Kenny Rutherford, Scotland’s Rural College, United KingdomJen-Yun Chou, University of Saskatchewan, Canada

Copyright © 2025 Staveley, Plush, Lines, Hemsworth, D’Souza and van Barneveld. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lauren M. Staveley, bGF1cmVuLnN0YXZlbGV5QHN1bnBvcmtmYXJtcy5jb20uYXU=

Lauren M. Staveley

Lauren M. Staveley Kate J. Plush

Kate J. Plush David S. Lines1

David S. Lines1 Lauren M. Hemsworth

Lauren M. Hemsworth Darryl N. D’Souza

Darryl N. D’Souza