- 1Ruminant Diseases and Immunology Research Unit, National Animal Disease Center, United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Ames, IA, United States

- 2ARS Research Participation Program, Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education (ORISE), Oak Ridge, TN, United States

- 3Infectious Bacterial Diseases Research Unit, National Animal Disease Center, Agricultural Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture, Ames, IA, United States

Introduction: Mycoplasma bovis causes chronic respiratory disease with high mortality rates in American bison (Bison bison). A recent study showed that a subunit vaccine containing M. bovis elongation factor thermal unstable (EFTu) and heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) antigens induced immunity and enhanced protection in bison, resulting in reduced lung lesions and bacterial loads following experimental M. bovis challenge. This study aimed to characterize the transcriptional responses underlying this protection in vaccinated (n = 5) compared to unvaccinated control (n = 4) bison following M. bovis infection.

Methods: Two doses of vaccines were administered on day 0 and at 21 days post-vaccination (DPV), followed by intranasal inoculation with bovine herpesvirus-1 (BHV-1) at 36 DPV and M. bovis at 40 DPV. RNA sequencing was performed on liver, palatine tonsil (PT), retropharyngeal lymph node (RPLN), tracheobronchial lymph node (TBLN), spleen, and whole blood samples. Blood was collected at 1st vaccination (Day 0), 2nd vaccination (21 days post-vaccination), BHV-1 inoculation (36 DPV), M. bovis inoculation (40 DPV), and 1 week post M. bovis inoculation (47 DPV).

Results and discussion: The greatest number of differentially expressed transcripts (DETs) (≤0.05 FDR) were found in blood at 36 DPV (123 total DETs) and in spleen (57 DETs). At 36 DPV, vaccinated animals showed upregulation of transcripts involved in in cell adhesion, T-helper cell (Th1/Th2/Th17) differentiation, and antigen processing and presentation. This signifies a robust response to the 2nd vaccine dose, which caused increased expression of CD3E, CD4, and CD8B correlating to increased T cell proliferation. Notably, transcription factors TBX21 and GATA3 were upregulated in vaccinated animals. Spleen-specific regulation included transcripts involved in innate immune response, such as LGALS3 and GBP-1. These findings highlight the robust immune response induced by the vaccine, particularly through T-cell mediated responses, demonstrating its potential to enhance protective immunity against M. bovis in bison.

Introduction

Mycoplasma bovis is a bacterium without a cell wall (or mollicutes) frequently associated with the bovine respiratory disease complex (BRDC) in cattle (1). In cattle, M. bovis is considered a secondary pathogen appearing after or alongside primary infections (2). Stressors, such as weaning, transport, or a concurrent viral infection, can lead to a compromised immune system that allows M. bovis to colonize the lower respiratory tract and cause BRDC (3). M. bovis is also known to cause mastitis in dairy cattle (4). Although M. bovis has long been recognized as a prominent pathogen in cattle, it has recently emerged as a significant threat to North American bison populations. In bison, M. bovis can act as a primary pathogen causing high mortality epizootics of casonecrotic pneumonia frequently associated with pharyngitis, laryngitis, polyarthritis, and other pathologies (5–7).

Transcriptome studies have been used to study immune responses in the context of animal health. Alterations in gene expression have been observed in cattle infected with pathogens of the BRDC, such as M. bovis, Mannheimia haemolytica, bovine herpesvirus-1 (BHV-1), and bovine viral diarrhea virus (8–10). Pathogens associated with mastitis infection (Staphylococcus aureus) and blood-borne infection (bovine leukemia virus) also modulate host gene expression profiles, reflecting immune activation and disease pathogenesis (11, 12). Biomarkers of infection and inflammation can be used for detection and outcome prediction of BRDC. However, transcriptional alterations in bison in response to infection or vaccination have not been characterized.

We previously reported an injectable subunit vaccine containing recombinant elongation factor thermal unstable (EFTu) and heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) can confer protection against M. bovis infection in bison (13). Vaccination resulted in reductions in lung pathology, lung bacterial loads, and detection of bacteria in the joints. Bison that received vaccine had a robust antibody response in addition to a T cell response characterized by the development of antigen specific CD8+ and ϒδ+ T cells. Additionally, we observed increased blood neutrophil counts in half of the unvaccinated control bison following challenge (13). To deepen our understanding of M. bovis pathogenic mechanisms and the host immune response to vaccination, the associated transcriptional responses were investigated. We hypothesize that vaccination with recombinant M. bovis antigens enhances protective immunity in bison by priming transcriptional pathways involved in T-cell activation. The objective of the current study was to assess the impacts of vaccination on gene expression profiles across various tissues (liver, palatine tonsil, retropharyngeal lymph node, tracheobronchial lymph node, and spleen) and sequentially collected blood samples in bison.

Materials and methods

Animal welfare

Animals were housed and samples collected in accordance with the Animal Welfare Act Amendments (7 U. S. Code e § 2,131 to § 2,156). All protocols and procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the National Animal Disease Center, Ames, IA (ARS-22-1035) before the onset of the study. Animal caretakers, veterinarians, and scientific staff performed animal monitoring and record keeping. Animals were humanely euthanized by intravenous sodium pentobarbital following the per-label dose and the discretion of the clinical veterinarian.

Animal origin

The animals were purchased from a commercial facility by USDA. The present study uses tissue and blood samples collected from the same animals in a previous study that has been published (13).

Animal study

Nine bison (~1–5 years old) were randomly assigned to one of two treatment groups: unvaccinated control (n = 4) or vaccinated (n = 5). An injectable subunit vaccine was formulated by mixing 100 μg of recombinant EFTu and 100 μg of Hsp70 with an oil-in-water emulsified adjuvant (Emulsigen®-D) as previously described (13, 14). Unvaccinated control animals were given a mock vaccine containing only emulsified adjuvant. Two doses of either vaccine or mock vaccine (2 mL per dose) were given at day 0, and at 21 days post-vaccination (DPV). Animals were inoculated with bovine herpesvirus-1 (BHV-1) at 36 DPV and with M. bovis at 40 DPV using an intranasal mucosal atomization device. Inoculums were prepared as previously described (5). Animals were euthanized between 51–65 DPV. Euthanasia and event summary tables can be found in Supplementary Table S1. Peripheral blood was collected by venipuncture and frozen in PAXGene tubes at 5 time points: Day 0 (1st vaccination), 21 DPV (2nd vaccination), 36 DPV (BHV-1 inoculation), 40 DPV (M. bovis inoculation), and 47 DPV (1 week post M. bovis inoculation). Blood samples were taken at the same time for all animals and collected directly before vaccination or inoculation events. Liver, palatine tonsil (PT), retropharyngeal lymph node (RPLN), tracheobronchial lymph node (TBLN), and spleen were collected at necropsy and immediately stored in RNAlater (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States).

RNA isolation

Total RNA was extracted and purified using the MagMAX™ mirVana™ Total RNA Isolation Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Quality and concentration of total RNA samples was evaluated using the Series II RNA 6000 Nano LabChip® kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, United States) and samples with an RNA integrity number of ≥7.5 were used for subsequent library preparation.

Library preparation and sequencing

The NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Module was used for mRNA selection from extracted total RNA and libraries were prepared using the NEBNext Ultra II RNA library prep kit (New England Biolabs, Ipswitch, MA, United States) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Library index incorporation was done using the NEBNext Multiplex Oligos for Illumina kit (New England Biolabs). Libraries were pooled in equal concentration and stored at −20°C until sequencing using the NovaSeq6000 system on S2 flow cells with 150-cycle paired end reads (2 × 150 bp) at the Iowa State University DNA sequencing facility.

RNAseq data processing

Quality of raw reads was assessed with FastQC (version 0.12.1). Adapter sequences were removed and low-quality bases were trimmed (quality-cutoff of 30 and minimum-length ≥60) using Cutadapt (version 4.0). The Bison genome fasta file and annotation files (Bison_UMD1.0) were downloaded from Ensembl. For read alignment and quantification of transcript abundance, the STAR-RSEM pipeline was used (STAR version 2.7.10b; RSEM version 1.3.3). Mapping indices were created and trimmed reads were mapped with STAR. Transcript expression was quantified with rsem-calculate-expression and rsem-generate-data-matrix was used to generate the transcript count matrix.

Differential expression analysis

The software DESeq2 (version 1.44.0) was used for differential expression analysis. The DESeqDataSetFromMatrix and estimateSizeFactors functions were used to create a DESeq2 object and normalize counts with the median ratio method, respectively. Transcripts with at least 5 normalized counts in at least 2 samples were kept for further analysis. The Wald test was used to generate baseMean, log2FoldChange, log fold change standard error, and adjusted p-values. The Benjamini-Hochberg procedure was used by DESeq2 for p-value adjustment in order to control the false discovery rate. Transcripts were deemed significant with an adjusted p-value < 0.05.

Correlation heatmaps for all samples were generated with pheatmap (version 1.0.12). Volcano plots and heatmaps were generated using the R packages EnhancedVolcano (version 1.22.0) and ggplot2 (version 3.5.1). Venn diagrams were generated using ggVennDiagram (version 1.5.2). Gene ontology and KEGG enrichment analysis of DETs was performed with DAVID.

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA)

The WGCNA R package (version 1.73) was used to identify modules of highly correlated transcripts connected to vaccination status (15). The top (75% quantile) transcripts for expression variance were identified using the quantile function and used for module identification. The weighted network adjacency matrix was calculated from the expression data based on Pearson correlation coefficients using the adjacency function and a soft-thresholding power of 5 was used to achieve a scale free topology index of 0.85. The adjacency matrix was converted into a topological overlap matrix with the TOMsimilarity function and hierarchical clustering grouped transcripts into modules with a minimum size of 10 transcripts. Eigen values were correlated to vaccination status using cor and corPvalueStudent functions of WGCNA. Network files were exported and visualized using Cytoscape (version 3.10.3).

Results

Overview of RNAseq data

To quantify transcript expression, raw reads were processed and aligned to the bison reference genome (Bison_UMD1.0). An average of ~36 million raw reads were obtained per sample. Adapter and quality trimming yielded an average of ~27 million trimmed reads per sample. In tissues samples, alignment rates ranged from 84.6% (PT) to 88.82% (RPLN). In blood, alignment rates ranged from 82.7% (2nd vaccination) to 87.5% (1st vaccination).

Liver, spleen, and blood samples separated into distinct clusters with high correlations across samples (R > 0.9), whereas PT, RPLN, and TBLN often clustered together indicating greater similarity in gene expression (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Dendrogram correlation heatmap across liver, PT, RPLN, TBLN, spleen, and blood (0 DPV, 21 DPV, 36 DPV, 40 DPV, 47 DPV) showing clustering of samples based on gene expression. Correlation scale is indicated by red (highest correlation) and blue (lowest correlation) colors. Treatment colors are shown in blue (Control) or gray (Vaccinate). Sample type is shown in different colors. The samples were collected from unvaccinated control (n = 4) and vaccinated (n = 5) animals.

Number of differentially expressed transcripts

A summary of differentially expressed transcripts between control and vaccinated animals in all tissues and time points is shown in Table 1. The greatest number of differentially expressed transcripts (DETs) within tissues was found in spleen, where 57 DETs were identified. Galactin-3 (LGALS3) was downregulated and Fos Proto-Oncogene, AP-1 Transcription Factor (FOS) was upregulated in spleen of vaccinated animals (Figure 2). The 2nd highest number of DETs in tissue was found in liver, where major facilitator super family domain containing 2a (MFSD2A) was upregulated in vaccinated animals compared to control (16). The number of DETs in other tissues ranged from 3 (RPLN) to 12 (TBLN). DETs included SEC16 homolog A (SEC16A), which was upregulated in TBLN of vaccinated animals (17). Upregulation of general control non-derepressible protein 1 (GCN1) was observed in RPLN of vaccinated animals. A regulator of interferon signaling, zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 1 (ZEB1), was downregulated and an immunoregulatory molecule, Disabled-2 (DAB2), was upregulated in PT of vaccinated animals (18–20).

Table 1. Number of up- and down-regulated differentially expressed transcripts between Control and Vaccinate animals.

Figure 2. Volcano plot of differentially expressed transcripts (DETs) between control and vaccinate in liver, tracheobronchial lymph node (TBLN), retropharyngeal lymph node (RPLN), palatine tonsil (PT), and spleen. Log2 fold change is shown on the x-axis and -log10 adjusted p-value on the y axis. Transcripts downregulated in vaccinate are shown in blue and transcripts upregulated in vaccinate are shown in pink. Non-significant transcripts are shown in grey. LGALS3 = Galactin-3; FOS = Fos Proto-Oncogene, AP-1 Transcription Factor; MFSD2A = major facilitator super family domain containing 2a; SEC16A = SEC16 homolog A; GCN1 = GCN activator of EIF2AK4; DAB2 = Disabled-2; ZEB1 = Zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 1. The samples were collected from unvaccinated control (n = 4) and vaccinated (n = 5) animals.

The number of DETs between control vs. vaccinated animals in blood ranged from 11 total DETs (Day 0) to 123 total DETs (36 DPV) (Table 1). The transcription factor paired box 5 (PAX5) facilitates differentiation of B cells and was upregulated in vaccinated animals at 21 DPV as shown in Figure 3 (21). Transcripts related to heparin binding, such as apolipoprotein E (APOE) and fibronectin 1 (FN1) were downregulated in vaccinated animals at 36 DPV (22, 23). At 40 DPV, v-set immunoregulatory receptor (VSIR) was upregulated in vaccinated animals (24). Anoctamin 10 (ANO10) was downregulated in vaccinated animals compared to control (25). Sorcin (SRI) and Fc fragment of IgE receptor Ig (FCER1G) were downregulated at 1 week post M. bovis infection (47 DPV) in vaccinated animals (26, 27). DESeq2 results for all samples can be found in Supplementary Tables S2, S3.

Figure 3. Volcano plot of differentially expressed transcripts (DETs) between control and vaccinate in 0 days post-vaccination (DPV), 21 DPV, 36 DPV, 40 DPV, 47 DPV. Log2 fold change is shown on the x-axis and –log10 adjusted p-value is on the y axis. Transcripts downregulated in vaccinate are shown in blue and transcripts upregulated in vaccinate are shown in pink. Non-significant transcripts are shown in gray. PAX5 = Paired box 5; APOE = Apolipoprotein E; FN1 = Fibronectin 1; VSIR = V-set immunoregulatory receptor; ANO10 = Anoctamin 10; SRI = Sorcin; FCER1G = Fc fragment of IgE receptor Ig. The samples were collected from unvaccinated control (n = 4) and vaccinated (n = 5) animals.

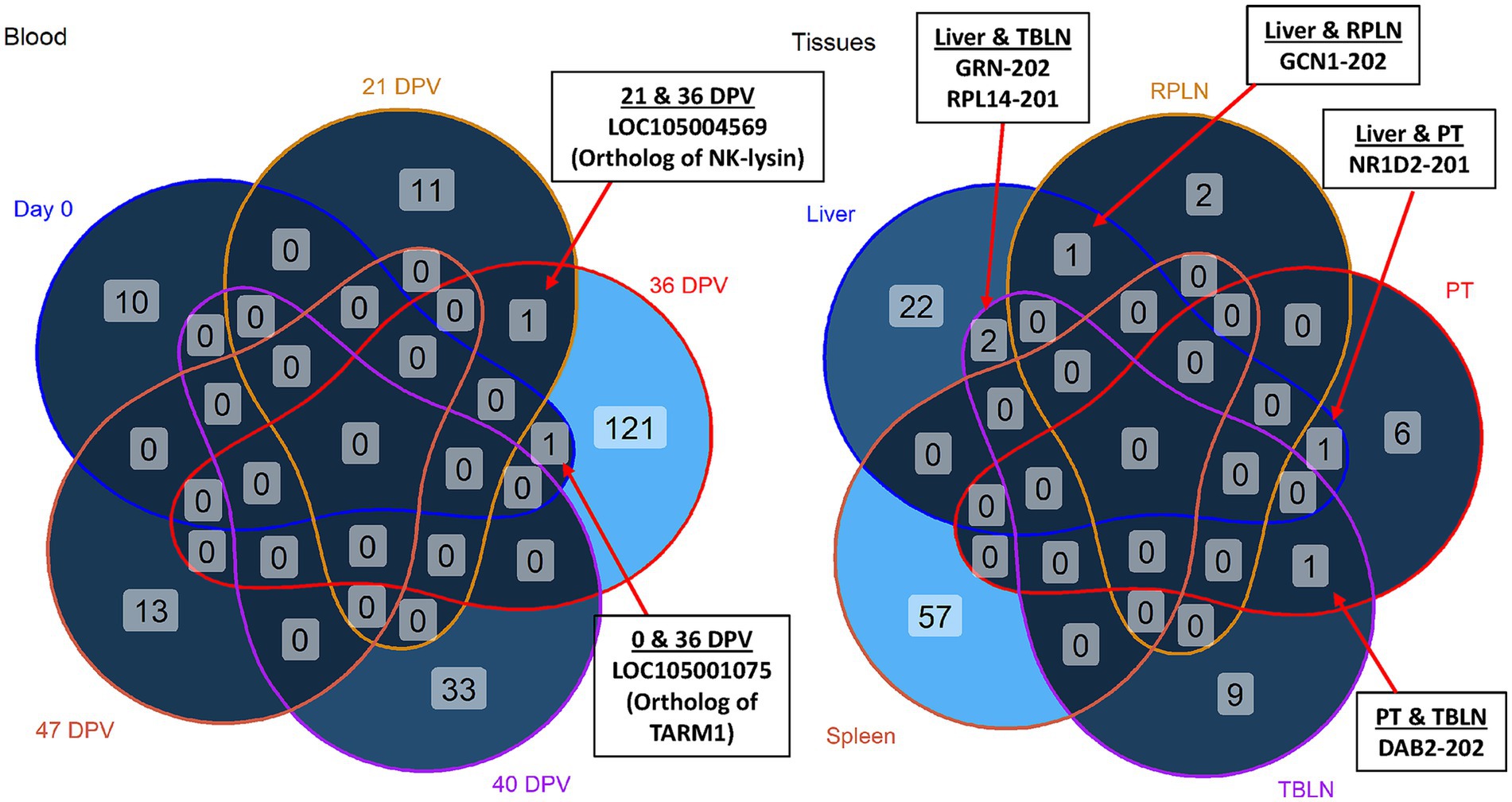

Shared differentially expressed transcripts (DETs) across tissues and blood time points

Out of 190 DETs, 178 were unique to day of vaccination in blood. However, LOC105004569 (ortholog of NK-lysin) and LOC105001075 (ortholog of T cell-interacting activating receptor on myeloid cells 1/TARM1) were shared across more than one time point (Figure 4, left). The antimicrobial peptide, NK-lysin, is produced by T lymphocytes and natural killer cells, and was upregulated in vaccinated animals at 21 and 36 DPV (28). The leukocyte receptor, TARM1, is critical for macrophage activation and was upregulated in vaccinated animals at day 0 and 36 DPV (29).

Figure 4. Venn diagrams of differentially expressed transcripts (DETs). Shared and unique DETs across day 0, 21 days post-vaccination (DPV), 36 DPV, 40 DPV, 47 DPV. Shared and unique DETs across liver, retropharyngeal lymph node (RPLN), palatine tonsil (PT), tracheobronchial lymph node (TBLN), and spleen. Shared DETs are indicated by arrows. TARM1 = T cell-interacting, activating receptor on myeloid cells 1; GRN = granulin precursor; RPL14 = ribosomal protein L14; GCN = GCN1 activator of EIF2AK4; NR1D2 = nuclear receptor subfamily 1 group D member 2; DAB2 = DAB adapter protein 2. The samples were collected from unvaccinated control (n = 4) and vaccinated (n = 5) animals.

In tissue comparisons, DETs in liver overlapped with DETs in TBLN, RPLN, and PT (Figure 4, right). Granulin precursor (GRN) and ribosomal protein L14 (RPL14) were upregulated in liver and TBLN of vaccinated animals. The gene GCN1 was downregulated in liver and upregulated in RPLN of vaccinated animals. Nuclear receptor subfamily 1 group D member 2 (NR1D2) was downregulated in liver and PT of vaccinated animals (30). A negative regulator of Toll-like receptor signaling, DAB2, was upregulated in PT and downregulated in TBLN of vaccinated animals (31).

Gene ontology and KEGG enrichment analysis

As shown in Table 2, significant enrichment of DETs was observed in spleen and liver. No significant enrichment was observed in PT, TBLN, or RPLN. DETs in spleen, such as T-complex 1 (TCP1) and prostaglandin E synthase 3 (PTGES3), were downregulated in vaccinated animals and enriched in biological processes of protein stabilization and positive regulation of telomere maintenance. There was a tendency for enriched innate immune response (p-value = 0.06), where LGALS3 and LOC105003308 (Ortholog of interferon-induced guanylate-binding protein/GBP-1) were downregulated in vaccinate spleen and ADAM metallopeptidase domain 15 (ADAM15) was upregulated. In liver, protein tyrosine phosphatase non-receptor type 6 (PTPN6) and beta-transducin repeat containing E3 ubiquitin protein ligase (BTRC) were upregulated in vaccinated animals and enriched in the negative regulation of T cell receptor signaling pathway.

Table 2. The significant pathways, biological processes, and molecular functions enriched with differentially expressed transcripts (DETs) in spleen and liver.

The greatest number of significantly enriched gene ontology terms and pathways was found at 36 DPV (Figure 5). The most significantly enriched pathways were cell adhesion molecules, Th17 cell differentiation, antigen processing and presentation, and HIV-1 infection pathways. Infiltrated lymphocyte markers (GATA binding protein 3/GATA3, Interleukin 27 receptor subunit alpha/IL27RA, CD3E, CD4, and T-box transcription factor 21/TBX21) were enriched in Th17 cell differentiation and upregulated in vaccinated animals at 36 DPV (Figure 6A). The ortholog of bovine leukocyte antigens class I major histocompatibility complex (MHC), alpha chain BL3-7 (LOC104983816) and a binding partner of MHC Class I molecules, TAP binding protein (TAPBP), were upregulated in vaccinated animals and enriched in antigen processing and presentation (Figure 6B). Phospholipase C, gamma-2 (PLCG2) was downregulated and tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 1B (TNFRSF1B) was upregulated in vaccinated animals and enriched in HIV-1 infection (Figure 6C). Upregulation of cell adhesion DETs was found, such as CD2, CD6, LOC105004586 (Ortholog of CD8b), and LOC104986653 (Ortholog of Sialophorin/SPN) at 36 DPV (Figure 6D).

Figure 5. Significantly enriched biological processes, molecular functions, and pathways at 36 days post vaccination (DPV). Categories are depicted in different colors. The x-axis shows log10 p-value and the y-axis shows the enriched term. The dashed line indicates a p-value threshold of 0.05. The samples were collected from unvaccinated control (n = 4) and vaccinated (n = 5) animals.

Figure 6. Heatmap visualization of top significantly enriched pathways at 36 days post-vaccination. Differentially expressed transcripts (DETs) were significantly enriched in (A) Th17 cell differentiation, (B) antigen processing and presentation, (C) HIV-1 infection, and (D) cell adhesion molecules. The color scale shows the log counts per million (logCPM) expression level of the transcripts within each sample. The samples were collected from unvaccinated control (n = 4) and vaccinated (n = 5) animals.

At 40 DPV (or 4 days post-BHV-1 challenge), VPS50 subunit of EARP (VPS50) and SEC31 Homolog A (SEC31A) were upregulated in vaccinated animals and enriched in protein transport. In addition, two upregulated (Fibulin 5/FBLN5 and SPARC Like 1/SPARCL1) and two downregulated (RAS Guanyl Releasing Protein 4/RASGRP4 and S100 Calcium Binding Protein A4/S100A4) DETs in vaccinated animals were enriched in calcium ion binding at 40 DPV.

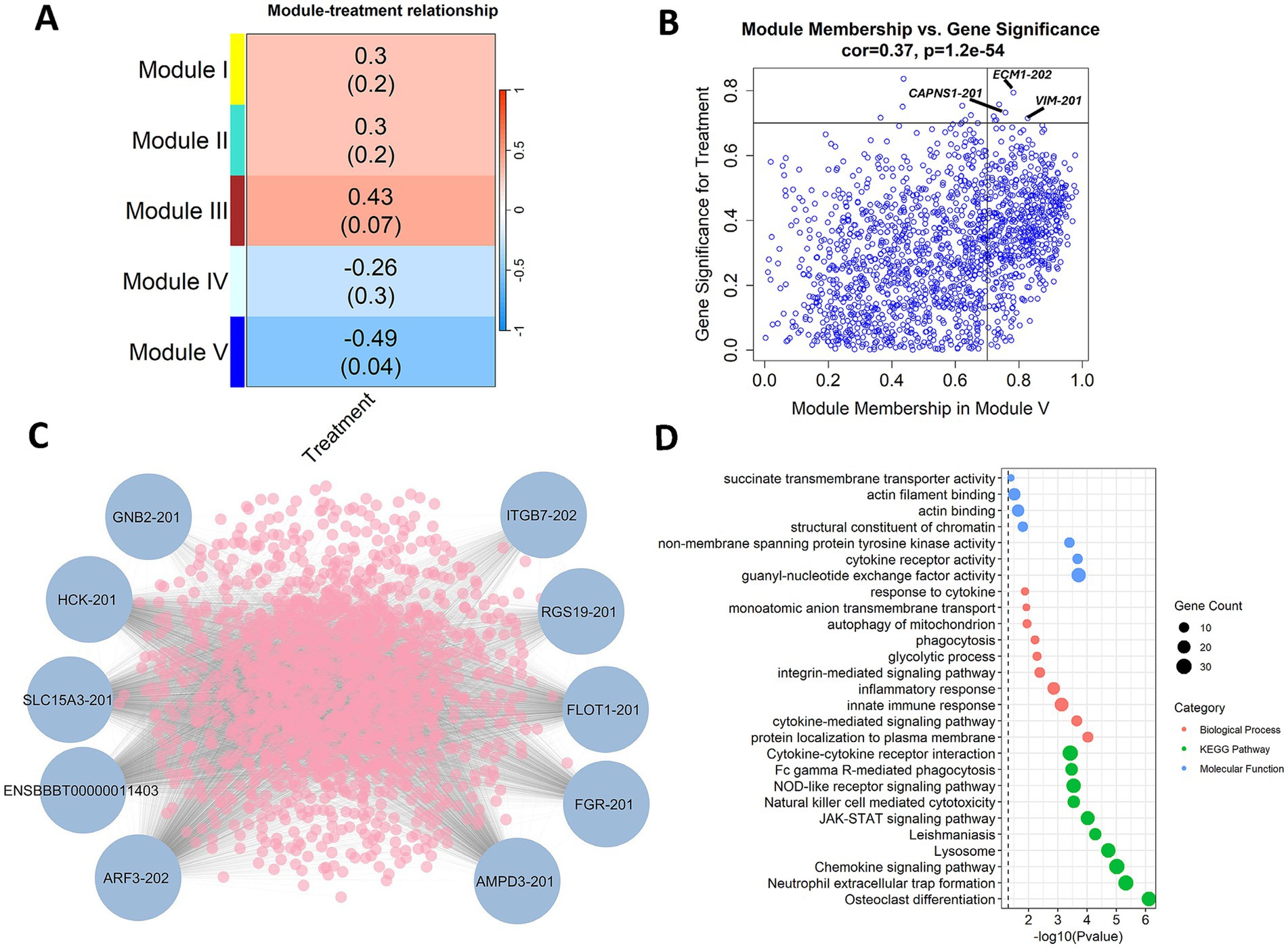

Transcript co-expression at 40 and 47 DPV

Weighted co-expression analysis identified 5 modules of co-expressed transcripts with correlations to treatment group at 40 and 47 DPV. Of these modules, Module V displayed a significant (p-value < 0.05) and intermediate, negative correlation (R = −0.49) with vaccinated animals (Figure 7A). Extracellular matrix protein 1 (ECM1), vimentin (VIM), and calpain small subunit 1 (CAPNS1) were among the transcripts with the highest significance (R > 0.7) for vaccination status and connectivity to other transcripts in the module (Figure 7B). The transcripts with the highest overall module membership in Module V included G protein subunit beta (GNB2), Src Family Tyrosine Kinases (HCK and FGR), solute carrier family 15 member 3 (SLC15A3), integrin subunit beta 7 (ITGB7), and flotillin 1 (FLOT1) as shown in Figure 7C. The most significant KEGG pathways enriched with the co-expressed transcripts in Module V included osteoclast differentiation, neutrophil extracellular trap formation, and chemokine signaling pathway (Figure 7D). The most significant enrichment for biological processes and molecular functions included protein localization to plasma membrane, cytokine-mediated signaling pathway, innate immune response, guanyl-nucleotide exchange factor activity, and cytokine receptor activity (Figure 7D).

Figure 7. Weighted gene co-expression analysis (WGCNA) reveals co-expression at 40 days post vaccination (DPV) and 47 DPV. (A) Module treatment correlation matrix displaying identified modules of co-expressed transcripts. (B) Correlation between module membership and gene significance for Module V transcripts. Transcripts with a module membership and significance greater than 0.7 are highlighted. (C) Top 10 transcripts with high connectivity to the expression of other transcripts in Module V. (D) Enrichment of Module V co-expressed transcripts in biological processes, KEGG pathways, and molecular functions. The samples were collected from unvaccinated control (n = 4) and vaccinated (n = 5) animals.

Discussion

Mycoplasma bovis is an etiologic agent of respiratory disease in American bison that is frequently associated with high morbidity and mortality (6, 32). Due to the significant economic and herd health impacts of M. bovis outbreaks in bison, effective intervention strategies are urgently needed. We previously reported an evaluation of the efficacy of an injectable, adjuvanted subunit vaccine containing EFTu and Hsp70 (13). In the current study, we conducted a transcriptome analysis across serially collected blood and tissues from the vaccinated and M. bovis challenged bison to examine host response to vaccination and better understand the molecular mechanisms mediating the partial protection observed against M. bovis.

T cell-mediated immunity is crucial for protection against intracellular and extracellular pathogens. While DETs at day 0 represent animal to animal variation, DETs at other time points were associated with heparin binding, immune response, and immune signaling. Vaccination resulted in an upregulation of transcripts associated with Th1, Th2, and Th17 cell differentiation with the greatest difference in gene expression occurring at approximately 2 weeks after the 2nd vaccine dose (36 DPV), suggesting a multifaceted T cell response. The adjuvant utilized in the current study was Emulsigen®-D containing dimethyldioctadecyl ammonium bromide (DDA), which is effective in inducing both systemic antibody and T-cell responses (33). Our previous work demonstrated that in vitro stimulation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells with recombinant EFTu or Hsp70 increased proliferation of CD4, CD8, and γδ T cells in vaccinated animals compared to control with a peak at 36 DPV (13). An increase in cytotoxic and helper T cell responses was mirrored in the blood transcriptome data as CD3E, CD4, and CD8B were upregulated in vaccinated animals compared to controls. The upregulation of transcription factors TBX21 and GATA3 in vaccinated animals also has implications for enhanced protection. In Th2 cells, GATA3 is selectively upregulated and binds to GATA motifs for Th2-specific expression to enhance humoral immunity (34). In Th1 cells, it is believed that the co-expression of T-bet (encoded by TBX21) sequesters GATA3 away from Th2 genes and induces GATA3 binding at Th1-specific sites (35). Thus, vaccination may stimulate CD4 T-cell polarization toward a Th1 phenotype by upregulating TBX21 and GATA3 expression. Finally, interleukin-2 (IL-2) signaling is known to drive the formation of Th1 precursor cells and also sustain Th1 responses during later stages of infection (36). Enhanced IL-2R signaling is also a key factor in programming CD8 T cells to become long lasting, functional memory cells and upregulation of IL-2 receptor beta (IL2RB) in vaccinated animals at 36 DPV suggests that the subunit vaccine may provide a cell-mediated immune memory (37).

IL-27 can stimulate Th1 cell differentiation and is linked to the activation of CD8 T cells (38). An alternative function of IL-27 includes modulating inflammatory responses during infection (39). The inhibition of IL27RA results in increased macrophage damage and inflammation during Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection (40). Caseonecrosis is frequently observed in the lungs of bison and cattle during M. bovis infection. The multifocal lesions present in the lungs have noted infiltration of macrophages and neutrophils often surrounding a core comprised of necrotic material, demonstrating excessive myeloid cell infiltration is involved in lung tissue damage (13, 41). The upregulation of IL27RA in vaccinated animals at 36 DPV in the present study may be related to reductions in inflammation and antibacterial activity of macrophages against M. bovis. Invasion of bovine cells by M. bovis has been demonstrated in vitro, suggesting the elimination of intracellular M. bovis in vivo is necessary for the clearance of infection (42, 43). An effective Th1-type immune response would be beneficial in eliminating infected cells and enhancing M. bovis clearance while limiting immunopathology. Together, these findings suggest that the adjuvanted protein subunit vaccine promoted a balanced, effective T-cell response based on the upregulation of interleukin receptors and key transcription factors.

The regulation of adhesion molecules involved in antigen presentation and co-stimulation, such as MHC Class I and SPN, has been associated with immune regulation and both were upregulated in vaccinated animals at 36 DPV. SPN (also known as CD43) promotes T cell activation and proliferation and has a role in neutrophil migration. SPN also has a protective role during Staphylococcus aureus infection, where monoclonal antibodies designed to target SPN impair phagocytosis, leading to increased bacterial burden, higher morbidity, and mortality, demonstrating that SPN has a role in effective immune responses by potentially enhancing phagocytic function (44). The MHC class I molecules are expressed in all nucleated cells and present endogenous antigens to CD8 cells, in which they bind and display viral peptides on their surface. The MHC class I molecule can then be recognized by cytotoxic T cells in order to destroy cells infected with viruses (45, 46). A chaperone protein, TAPBP, is involved in endogenous antigen presentation by MHC class I and functions crucially in peptide loading onto MHC class I molecules (47). The upregulation of TAPBP in vaccinated animals may underlie increased immune responses by CD8 T cells.

An ortholog of NK-lysin (LOC105004569) was a DET that was upregulated in vaccinated animals at 21 and 36 DPV. NK-lysins are multifunctional peptides found in cytolytic granules of cytotoxic T-lymphocytes and natural killer cells with antibacterial and antiviral activities (28, 48, 49). Earlier studies have demonstrated the antimicrobial action of bovine NK-lysin against pathogens associated with bovine respiratory disease, including M. bovis, Histophilis somni, Pasteurella multocida, and M. haemolytica (50–52). Our previous work has shown the ability of bovine NK-lysins to breach the plasma membrane permeability barrier of M. bovis, causing membrane depolarization and structural damage to the plasma membrane (50).

Co-expression analysis revealed a negative correlation between vaccination and the expression of transcripts involved in cytokine-mediated signaling and chemokine signaling pathways at 40 and 47 DPV. This suggests that BHV-1 may have an immunosuppressive effect at 40 DPV. VIM was one of the co-expressed transcripts with the highest treatment significance and module membership, where decreased expression of vimentin can inhibit NLRP3 inflammasome signaling and cytokine production (53). Transcripts in Module V, including HCK and FGR, were also negatively correlated to vaccination status. Synergistic regulation by these Src family kinases has been previously described in mice, where knockout of HCK and FGR in addition to Lyn results in decreased inflammatory effects due to inhibited cytokine production (54). Given that cytokine and chemokine signaling shape the inflammatory response, altered expression of these transcripts may influence immune cell activation and the inflammatory environment in vaccinated animals. Potentially, this leads to increased pathogen control while decreasing inflammation and immunopathology following M. bovis challenge.

The gene LGALS3 was the most significantly dysregulated gene in spleen and was downregulated in vaccinated animals. LGALS3 encodes Galectin-3, which has been described as a facilitator of viral attachment and entry as well as a stimulator of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines to illicit an antiviral response (55–57). The ability of Galectin-3 to promote migration of immune cells to infection sites can exacerbate inflammation and tissue damage. Both small molecule inhibitors and monoclonal antibodies targeting Galectin-3 have potential for antiviral therapy as inhibition by a Galectin-3 antagonist resulted in reduced viral load in COVID-19 patients (56, 58). Galectin-3 knockout mice displayed reduced Brucella abortus loads as well as increased numbers of macrophages and neutrophils in spleen (59, 60). Galectin-3 also facilitates the delivery of antimicrobial GBP-1 to pathogen containing vacuoles, which are intracellular compartments for microbial growth (61). GBPs are induced by proinflammatory stimuli, mainly interferons. In some cases, M. bovis infection can cause moderate splenitis, and the decreased expression of Galectin-3 and GBP-1 in vaccinated animals could perhaps be associated with a reduction in inflammation of the spleen (5). Given that the spleen has a range of immunological functions (e.g., filtering pathogens from blood, antigen trapping and regulation of T and B cell response), vaccination may have had an influence on splenic function and aided in recovery from M. bovis infection (62).

The present study utilizes transcriptomics to characterize immune response to vaccination and the mechanisms contributing to reduced clinical disease. Robust transcriptional regulation of immune-related pathways was primarily observed at 36 DPV with significant upregulation of cell adhesion, Th1/Th2/Th17 cell differentiation, and antigen processing and presentation. The upregulation of T helper differentiation pathways suggests a maturing immune response, while enhanced antigen presentation and cell adhesion may describe increased immune cell trafficking and interactions due to vaccination. Trafficking of immune cells potentially leads to the recruitment of immune cells to interact at sites where they are needed to fight infection. Spleen-specific regulation included transcripts involved in innate immune response and inflammation, such as LGALS3 and GBP-1. It is important to note that a small sample size (n = 4–5) was used in this study and future work should consider including larger sample sizes to account for individual variability in vaccine response. In addition, BHV-1 was used in the study to replicate a co-infection model, which may have introduced off-target effects that confound our interpretation of the immune response to M. bovis inoculation. These findings are the first to describe the transcriptomic response to M. bovis infection in bison and suggest that the protein subunit elicited a broad, temporally regulated immune response detected in both blood and tissue.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are publicly available. The sequence files can be found in the NCBI repository under BioProject accession number PRJNA1274494 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/?term=%20PRJNA1274494).

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by the USDA-ARS NADC Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Protocol # ARS-22-1035). The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

AG: Visualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Investigation. BK: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. HM: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Conceptualization. CK: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. PB: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Conceptualization. LC: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. SO: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. RB: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Investigation. FT: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Investigation. RD: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Conceptualization. EC: Data curation, Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by funding through internal USDA research dollars (USDA/Agricultural Research Service, National Animal Disease Center, CRIS 5030-32000-236-000-D). The funder had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or manuscript preparation.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Brad Chriswell, William Boatwright, Jr., Darl Pringle, Kathy Bickel, and Sam Humphrey for their excellent technical assistance. The authors also thank Rebecca Cox, Kolby Strallman, Jonathan Gardner, and Derek Vermeer for their expert assistance with animal studies. Mention of trade name, proprietary product, or specified equipment does not constitute a guarantee or warranty by the USDA and does not imply approval to the exclusion of other products that may be suitable. USDA is an Equal Opportunity Employer.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fvets.2025.1667623/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Perez-Casal, J. Pathogenesis and virulence of Mycoplasma bovis. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. (2020) 36:269–78. doi: 10.1016/j.cvfa.2020.02.002

2. Oliveira, TES, Pelaquim, IF, Flores, EF, Massi, RP, Valdiviezo, MJJ, Pretto-Giordano, LG, et al. Mycoplasma bovis and viral agents associated with the development of bovine respiratory disease in adult dairy cows. Transbound Emerg Dis. (2020) 67:82–93. doi: 10.1111/tbed.13223

3. Griffin, D, Chengappa, MM, Kuszak, J, and McVey, DS. Bacterial pathogens of the bovine respiratory disease complex. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. (2010) 26:381–94. doi: 10.1016/j.cvfa.2010.04.004

4. Gelgie, AE, Desai, SE, Gelalcha, BD, and Kerro Dego, O. Mycoplasma bovis mastitis in dairy cattle. Front Vet Sci. (2024) 11:1322267. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2024.1322267

5. Register, KB, Olsen, SC, Sacco, RE, Ridpath, J, Falkenberg, S, Briggs, R, et al. Relative virulence in bison and cattle of bison-associated genotypes of Mycoplasma bovis. Vet Microbiol. (2018) 222:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2018.06.020

6. Janardhan, KS, Hays, M, Dyer, N, Oberst, RD, and DeBey, BM. Mycoplasma bovis outbreak in a herd of north American Bison (Bison bison). J Vet Diagn Invest. (2010) 22:797–801. doi: 10.1177/104063871002200528

7. Dyer, N, Hansen-Lardy, L, Krogh, D, Schaan, L, and Schamber, E. An outbreak of chronic pneumonia and polyarthritis syndrome caused by Mycoplasma bovis in feedlot Bison (Bison bison). J Vet Diagn Invest. (2008) 20:369–71. doi: 10.1177/104063870802000321

8. O’Donoghue, S, Earley, B, Johnston, D, McCabe, MS, Kim, JW, Taylor, JF, et al. Whole blood transcriptome analysis in dairy calves experimentally challenged with bovine herpesvirus 1 (BoHV-1) and comparison to a bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV) challenge. Front Genet. (2023) 14:1092877. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2023.1092877

9. Goldkamp, AK, Atchison, RG, Falkenberg, SM, Dassanayake, RP, Neill, JD, and Casas, E. Host transcriptome response to Mycoplasma bovis and bovine viral diarrhea virus in bovine tissues. BMC Genomics. (2025) 26:361. doi: 10.1186/s12864-025-11549-2

10. Behura, SK, Tizioto, PC, Kim, J, Grupioni, NV, Seabury, CM, Schnabel, RD, et al. Tissue tropism in host transcriptional response to members of the bovine respiratory disease complex. Sci Rep. (2017) 7:17938. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-18205-0

11. Wiarda, JE, Davila, KMS, Trachsel, JM, Loving, CL, Boggiatto, P, Lippolis, JD, et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing characterization of Holstein cattle blood and milk immune cells during a chronic Staphylococcus aureus mastitis infection. Sci Rep. (2025) 15:12689. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-96657-5

12. Ma, H, Lippolis, JD, and Casas, E. Expression profiles and interaction of MicroRNA and transcripts in response to bovine leukemia virus exposure. Front Vet Sci. (2022) 9:887560. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.887560

13. Kaplan, BS, Dassanayake, RP, Briggs, RE, Kanipe, CR, Boggiatto, PM, Crawford, LS, et al. An injectable subunit vaccine containing elongation factor Tu and heat shock protein 70 partially protects American bison from Mycoplasma bovis infection. Front Vet Sci. (2024) 11:1408861. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2024.1408861

14. Briggs, RE, Billing, SR, Boatwright, WD, Chriswell, BO, Casas, E, Dassanayake, RP, et al. Protection against Mycoplasma bovis infection in calves following intranasal vaccination with modified-live Mannheimia haemolytica expressing Mycoplasma antigens. Microb Pathog. (2021) 161:105159. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2021.105159

15. Langfelder, P, and Horvath, S. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinform. (2008) 9:559. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-559

16. Piccirillo, AR, Hyzny, EJ, Beppu, LY, Menk, AV, Wallace, CT, Hawse, WF, et al. The Lysophosphatidylcholine transporter MFSD2A is essential for CD8+ memory T cell maintenance and secondary response to infection. J Immunol. (2019) 203:117–26. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1801585

17. Van Zuylen, WJ, Doyon, P, Clément, J-F, Khan, KA, D’Ambrosio, LM, Dô, F, et al. Proteomic profiling of the TRAF3 interactome network reveals a new role for the ER-to-Golgi transport compartments in innate immunity. PLoS Pathog. (2012) 8:e1002747. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002747

18. Figliuolo Da Paz, V, Ghishan, FK, and Kiela, PR. Emerging roles of disabled homolog 2 (DAB2) in immune regulation. Front Immunol. (2020) 11:580302. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.580302

19. Li, D, Cheng, P, Wang, J, Qiu, X, Zhang, X, Xu, L, et al. IRF6 is directly regulated by ZEB1 and ELF3, and predicts a favorable prognosis in gastric Cancer. Front Oncol. (2019) 9:220. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00220

20. Yang, J, Tian, B, Sun, H, Garofalo, RP, and Brasier, AR. Epigenetic silencing of IRF1 dysregulates type III interferon responses to respiratory virus infection in epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Nat Microbiol. (2017) 2:17086. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.86

21. Calderón, L, Schindler, K, Malin, SG, Schebesta, A, Sun, Q, Schwickert, T, et al. Pax5 regulates B cell immunity by promoting PI3K signaling via PTEN down-regulation. Sci Immunol. (2021) 6:eabg5003. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abg5003

22. Saito, H, Dhanasekaran, P, Nguyen, D, Baldwin, F, Weisgraber, KH, Wehrli, S, et al. Characterization of the heparin binding sites in human Apolipoprotein E. J Biol Chem. (2003) 278:14782–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M213207200

23. Lovett, BM, Hill, KE, Randolph, EM, Wang, L, and Schwarzbauer, JE. Nucleation of fibronectin fibril assembly requires binding between heparin and the 13th type III module of fibronectin. J Biol Chem. (2023) 299:104622. doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2023.104622

24. ElTanbouly, MA, Zhao, Y, Schaafsma, E, Burns, CM, Mabaera, R, Cheng, C, et al. VISTA: a target to manage the innate cytokine storm. Front Immunol. (2021) 11:595950. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.595950

25. Hammer, C, Wanitchakool, P, Sirianant, L, Papiol, S, Monnheimer, M, Faria, D, et al. A coding variant of ANO10, affecting volume regulation of macrophages, is associated with Borrelia Seropositivity. Mol Med. (2015) 21:26–37. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2014.00219

26. Li, X, Wang, J, Liu, J, Li, Z, Wang, Y, Xue, Y, et al. Engagement of soluble resistance-related calcium binding protein (sorcin) with foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV) VP1 inhibits type I interferon response in cells. Vet Microbiol. (2013) 166:35–46. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.04.028

27. Huang, C, Zhu, W, Li, Q, Lei, Y, Chen, X, Liu, S, et al. Antibody fc-receptor FcεR1γ stabilizes cell surface receptors in group 3 innate lymphoid cells and promotes anti-infection immunity. Nat Commun. (2024) 15:5981. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-50266-4

28. Dassanayake, RP, Atkinson, BM, Mullis, AS, Falkenberg, SM, Nicholson, EM, Casas, E, et al. Bovine NK-lysin peptides exert potent antimicrobial activity against multidrug-resistant Salmonella outbreak isolates. Sci Rep. (2021) 11:19276. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-98860-6

29. Li, X, Wang, M, Ming, S, Liang, Z, Zhan, X, Cao, C, et al. TARM-1 is critical for macrophage activation and Th1 response in Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J Immunol. (2021) 207:234–43. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.2001037

30. Tang, M, Hu, Z, Rao, C, Chen, J, Yuan, S, Zhang, J, et al. Burkholderia pseudomallei interferes with host lipid metabolism via NR1D2 -mediated PNPLA2/ATGL suppression to block autophagy-dependent inhibition of infection. Autophagy. (2021) 17:1918–33. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2020.1801270

31. Hung, W-S, Ling, P, Cheng, J-C, Chang, S-S, and Tseng, C-P. Disabled-2 is a negative immune regulator of lipopolysaccharide-stimulated toll-like receptor 4 internalization and signaling. Sci Rep. (2016) 6:35343. doi: 10.1038/srep35343

32. Bras, AL, Barkema, HW, Woodbury, MR, Ribble, CS, Perez-Casal, J, and Windeyer, MC. Clinical presentation, prevalence, and risk factors associated with Mycoplasma bovis-associated disease in farmed bison (Bison bison) herds in western Canada. J Am Vet Med Assoc. (2017) 250:1167–75. doi: 10.2460/javma.250.10.1167

33. Sarkar, I, Garg, R, and van Den Van Drunen Littel- Hurk, S. Selection of adjuvants for vaccines targeting specific pathogens. Expert Rev Vaccines. (2019) 18:505–21. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2019.1604231

34. Zhou, M, and Ouyang, W. The function role of GATA-3 in Th1 and Th2 differentiation. Immunol Res. (2003) 28:25–38. doi: 10.1385/IR:28:1:25

35. Kanhere, A, Hertweck, A, Bhatia, U, Gökmen, MR, Perucha, E, Jackson, I, et al. T-bet and GATA3 orchestrate Th1 and Th2 differentiation through lineage-specific targeting of distal regulatory elements. Nat Commun. (2012) 3:1268. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2260

36. Charley, KR, Ramstead, AG, Matous, JG, Kumaki, Y, Sircy, LM, Hale, JS, et al. Effector-phase IL-2 signals drive Th1 effector and memory responses dependently and independently of TCF-1. J Immunol. (2024) 212:586–95. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.2300570

37. Castro, I, Dee, MJ, and Malek, TR. Transient enhanced IL-2R signaling early during priming rapidly amplifies development of functional CD8+ T effector-memory cells. J Immunol. (2012) 189:4321–30. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202067

38. Yin, L, Zhang, E, Mao, T, Zhu, Y, Ni, S, Li, Y, et al. Macrophage P2Y6R activation aggravates psoriatic inflammation through IL-27-mediated Th1 responses. Acta Pharm Sin B. (2024) 14:4360–77. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2024.06.008

39. Hall, AO, Silver, JS, and Hunter, CA. The Immunobiology of IL-27 In: Advances in immunology : Elsevier (2012). 1–44.

40. Zhou, Y, Zhang, Y, Li, Y, Liu, L, Zhuang, M, and Xiao, Y. IL-27 attenuated macrophage injury and inflammation induced by Mycobacterium tuberculosis by activating autophagy. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol. (2025) 61:245–56. doi: 10.1007/s11626-024-00989-x

41. Dyer, N, Register, KB, Miskimins, D, and Newell, T. Necrotic pharyngitis associated with Mycoplasma bovis infections in American bison (Bison bison). J Vet Diagn Invest. (2013) 25:301–3. doi: 10.1177/1040638713478815

42. Van Der Merwe, J, Prysliak, T, and Perez-Casal, J. Invasion of bovine peripheral blood mononuclear cells and erythrocytes by Mycoplasma bovis. Infect Immun. (2010) 78:4570–8. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00707-10

43. Bürki, S, Gaschen, V, Stoffel, MH, Stojiljkovic, A, Frey, J, Kuehni-Boghenbor, K, et al. Invasion and persistence of Mycoplasma bovis in embryonic calf turbinate cells. Vet Res. (2015) 46:53. doi: 10.1186/s13567-015-0194-z

44. Bremell, T, Holmdahl, R, and Tarkowski, A. Protective role of sialophorin (CD43)-expressing cells in experimental Staphylococcus aureus infection. Infect Immun. (1994) 62:4637–40. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.10.4637-4640.1994

45. Zhao, T, Cai, Y, Jiang, Y, He, X, Wei, Y, Yu, Y, et al. Vaccine adjuvants: mechanisms and platforms. Signal Transduct Target Ther. (2023) 8:283. doi: 10.1038/s41392-023-01557-7

46. Wick, J M, and Ljunggren, H. Processing of bacterial antigens for peptide presentation on MHC class I molecules. Immunol Rev. (1999) 172:153–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.1999.tb01363.x

47. Del Val, M, Antón, LC, Ramos, M, Muñoz-Abad, V, and Campos-Sánchez, E. Endogenous TAP-independent MHC-I antigen presentation: not just the ER lumen. Curr Opin Immunol. (2020) 64:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2019.12.003

48. Yacoub, HA, Mahmoud, MM, Al-Hejin, AM, Abujamel, TS, Tabrez, S, and Abd-Elmaksoud, S. Effect of Nk-lysin peptides on bacterial growth, MIC, antimicrobial resistance, and viral activities. Anim Biotechnol. (2024) 35:2290520. doi: 10.1080/10495398.2023.2290520

49. Ortega, L, Carrera, C, Muñoz-Flores, C, Salazar, S, Villegas, MF, Starck, MF, et al. New insight into the biological activity of Salmo salar NK-lysin antimicrobial peptides. Front Immunol. (2024) 15:1191966. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1191966

50. Dassanayake, RP, Falkenberg, SM, Register, KB, Samorodnitsky, D, Nicholson, EM, and Reinhardt, TA. Antimicrobial activity of bovine NK-lysin-derived peptides on Mycoplasma bovis. PLoS One. (2018) 13:e0197677. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0197677

51. Chen, J, Yang, C, Tizioto, PC, Huang, H, Lee, MOK, Payne, HR, et al. Expression of the bovine NK-Lysin gene family and activity against respiratory pathogens. PLoS One. (2016) 11:e0158882. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158882

52. Dassanayake, RP, Falkenberg, SM, Briggs, RE, Tatum, FM, and Sacco, RE. Antimicrobial activity of bovine NK-lysin-derived peptides on bovine respiratory pathogen Histophilus somni. PLoS One. (2017) 12:e0183610. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183610

53. Dos Santos, G, Rogel, MR, Baker, MA, Troken, JR, Urich, D, Morales-Nebreda, L, et al. Vimentin regulates activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Nat Commun. (2015) 6:6574. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7574

54. Kovács, M, Németh, T, Jakus, Z, Sitaru, C, Simon, E, Futosi, K, et al. The Src family kinases Hck, Fgr, and Lyn are critical for the generation of the in vivo inflammatory environment without a direct role in leukocyte recruitment. J Exp Med. (2014) 211:1993–2011. doi: 10.1084/jem.20132496

55. Nita-Lazar, M, Banerjee, A, Feng, C, and Vasta, GR. Galectins regulate the inflammatory response in airway epithelial cells exposed to microbial neuraminidase by modulating the expression of SOCS1 and RIG1. Mol Immunol. (2015) 68:194–202. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2015.08.005

56. Stojanovic, BS, Stojanovic, B, Milovanovic, J, Arsenijević, A, Dimitrijevic Stojanovic, M, Arsenijevic, N, et al. The pivotal role of galectin-3 in viral infection: a multifaceted player in host–pathogen interactions. Int J Mol Sci. (2023) 24:9617. doi: 10.3390/ijms24119617

57. Woodward, AM, Mauris, J, and Argüeso, P. Binding of transmembrane mucins to Galectin-3 limits herpesvirus 1 infection of human corneal keratinocytes. J Virol. (2013) 87:5841–7. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00166-13

58. Sigamani, A, Mayo, KH, Miller, MC, Chen-Walden, H, Reddy, S, and Platt, D. An Oral galectin inhibitor in COVID-19—a phase II randomized controlled trial. Vaccine. (2023) 11:731. doi: 10.3390/vaccines11040731

59. Tana, FL, Guimarães, ES, Cerqueira, DM, Campos, PC, Gomes, MTR, Marinho, FV, et al. Galectin-3 regulates proinflammatory cytokine function and favours BRUCELLA ABORTUS chronic replication in macrophages and mice. Cell Microbiol. (2021) 23:13375. doi: 10.1111/cmi.13375

60. Liu, F-T, and Stowell, SR. The role of galectins in immunity and infection. Nat Rev Immunol. (2023) 23:479–94. doi: 10.1038/s41577-022-00829-7

61. Feeley, EM, Pilla-Moffett, DM, Zwack, EE, Piro, AS, Finethy, R, Kolb, JP, et al. Galectin-3 directs antimicrobial guanylate binding proteins to vacuoles furnished with bacterial secretion systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci. (2017) 114:1698–1706. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1615771114

Keywords: animal health, wild species, infectious disease, transcriptome, Mycoplasma bovis

Citation: Goldkamp AK, Kaplan BS, Menghwar H, Kanipe CR, Boggiatto PM, Crawford LS, Olsen SC, Briggs RE, Tatum FM, Dassanayake RP and Casas E (2025) Transcriptional profiles of vaccine-induced protection in bovine herpesvirus-1 and Mycoplasma bovis-challenged bison. Front. Vet. Sci. 12:1667623. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2025.1667623

Edited by:

Orhan Sahin, Iowa State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Kieran G. Meade, University College Dublin, IrelandKatarzyna Dudek, National Veterinary Research Institute (NVRI), Poland

Feng Pang, Guizhou University, China

Copyright © 2025 Goldkamp, Kaplan, Menghwar, Kanipe, Boggiatto, Crawford, Olsen, Briggs, Tatum, Dassanayake and Casas. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Eduardo Casas, RWR1YXJkby5jYXNhc0B1c2RhLmdvdg==

Anna K. Goldkamp

Anna K. Goldkamp Bryan S. Kaplan

Bryan S. Kaplan Harish Menghwar

Harish Menghwar Carly R. Kanipe

Carly R. Kanipe Paola M. Boggiatto

Paola M. Boggiatto Lauren S. Crawford

Lauren S. Crawford Steven C. Olsen

Steven C. Olsen Robert E. Briggs

Robert E. Briggs Fred M. Tatum1

Fred M. Tatum1 Rohana P. Dassanayake

Rohana P. Dassanayake Eduardo Casas

Eduardo Casas