- 1Department of Animal Sciences, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL, United States

- 2Department of Veterinary Clinical Medicine, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL, United States

- 3Division of Nutritional Sciences, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL, United States

Oral microbiota play a critical role in feline periodontal disease, with wet diets being associated with poor oral health. Because the oral microbial communities of cats remain underexplored, this study aimed to evaluate differences in the oral health indices and microbiota of cats fed a dry or wet diet. Twenty healthy adult cats had their teeth cleaned and polished. Cats were randomly allotted to a dry or wet diet and fed for 28 weeks. At that time, sulfur-containing compound concentrations and salivary pH were measured, plaque, calculus and gingivitis scores were assessed by a blinded veterinarian, and supragingival and subgingival plaque samples were collected for microbiota analysis. Microbiota data were evaluated using QIIME2. All other data were analyzed using the Mixed Models procedure of SAS. Cats fed the dry diet had lower tooth calculus coverage and thickness than cats fed the wet diet. Gingivitis scores were higher in cats fed the wet diet than those fed the dry diet. Other clinical measures did not differ. Bacterial alpha diversity measures on supragingival plaque were lower in cats fed the wet diet than those fed the dry diet. Bacterial beta diversity measures revealed distinct microbial communities between diet groups, with numerous changes to bacterial phyla and genera relative abundances. Compared with cats fed the dry diet, cats fed the wet diet had higher relative abundances of Bacteroidota and Bacteroides in supragingival samples and greater relative abundances of Synergistota, Bacteroides, Fretibacterium, Campylobacter, and Christensenellaceae R-7 group in subgingival samples. In contrast, cats fed the dry diet had higher relative abundances of Proteobacteria, Streptococcus, Luteimonas, Lautropia in supragingival plaque than those cats fed the wet diet. Although most clinical indices did not differ between groups, the reduced calculus scores, enrichment of health-associated bacteria and reduction in disease-associated bacteria suggest oral health benefits of dry diets.

Introduction

Dietary composition and physical characteristics can influence the development and progression of periodontal disease in companion animals. Among these factors, the texture of the diet, particularly its abrasive properties, is a key mechanism by which diet can influence oral health by reducing dental plaque accumulation (1). Supporting this, a recent study in dogs showed that plaque coverage tended to be higher in animals fed wet versus dry food, although other oral health scores did not differ (2). Dietary characteristics, including texture and nutrient composition, can directly affect the oral environment by maintaining oral tissue integrity, influencing the metabolic activity of plaque bacteria, promoting salivary secretion, and providing mechanical cleaning of teeth and oral surfaces through physical contact (3). As a result, dry, crunchy commercial diets are widely recognized for their potential oral health benefits in both dogs and cats. This concept is supported by early studies showing that dogs fed hard or solid diet maintained healthier teeth and gingiva than those consuming the same diet in a ground or minced form (4–6). Notably, even limited chewing, such as that involved in eating minced diet, provided some cleansing effect compared with no mastication at all, as demonstrated in dogs fed via gastric intubation (7).

Despite the widespread belief that dry diets promote oral health, there is limited scientific evidence supporting this claim, particularly in cats. Some studies suggest potential benefits; for instance, dental calculus and plaque were reported to be less frequent in cats fed dry diets than those fed wet diets (8). A cross-sectional study of 41 client-owned cats further reported that the likelihood of poor oral health was lower in young and adult cats consuming dry diets than in older cats fed wet diets, with diet type exerting a stronger effect on oral health than age itself (9). Complementing these findings, a small pilot study (n = 10) demonstrated that cats exclusively fed dry diets exhibited greater oral bacterial diversity and higher relative abundances of Porphyromonas and Treponema than those fed wet diets (10). Despite these observations, controlled studies directly evaluating the impact of diet type on the feline oral microbiota and associated health outcomes are still lacking, highlighting the need for further research in this area.

This research evaluated the impact of diet type (dry vs. wet) on oral health outcomes and plaque composition in healthy adult cats over a 28-week period, using a clean mouth model. This approach, initiating the study after professional dental cleaning, allowed for a standardized oral health baseline, minimizing confounding effects from pre-existing dental conditions. To reduce environmental variability, the trial was conducted under controlled laboratory conditions. We hypothesized that cats consuming a dry diet would have better oral health outcomes and a more beneficial oral microbiota composition than those fed a wet diet.

Materials and methods

All animal care procedures were approved by the University of Illinois Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee prior to initiation of the experiment (protocol #24025).

Animals, housing, and diets

Twenty adult American Shorthair cats (12 females and 8 males; 6.28 ± 0.29 yr.; 4.18 ± 0.15 kg body weight; 5.25 ± 0.05 body condition score) were used in a longitudinal completely randomized design study. Cats were housed individually in cages (1.02 m deep, 0.76 m wide; 0.71 m high) during feeding times (8–10 a.m.) in a temperature- and light-controlled (14-h light, 10-h dark cycle) room in the Edward R. Madigan Animal Facility at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. At other times, cats were group-housed and able to socialize and exercise outside of their cages. Cages and the group-housing area were cleaned daily. Cats were allowed access to various toys and scratching poles for environmental enrichment and play time with human interaction at least 2 times per week. Water was available ad libitum. Body weight was measured at the beginning and end of study, and were assessed weekly during the study. Body condition scores were assessed using a 9-point scale (11) weekly prior to the morning feeding.

Cats were assigned to 1 of 2 diets to balance sexes between treatments: dry diet (Purina - Cat Chow Complete with Real Chicken Dry Cat Food, n = 10; 4 males and 6 females) or wet diet (Purina - Friskies Pate Country Style Dinner Canned Cat Food, n = 10; 4 males and 6 females; Table 1). Both dietary treatments tested were commercial diets formulated to meet all Association of American Feed Control Officials (12) nutrient recommendations for adult cats at maintenance. Daily food intake was recorded. Individual food intake was determined by placing the animals in separate cages during feeding time. The food was weighed before and after each meal to accurately measure consumption. All cats were fed to maintain body weight throughout the study.

Experimental timeline

Before cats were allotted to treatments, a board-certified veterinarian polished and cleaned the teeth. After dental cleaning, cats were randomly allotted to a commercial dry extruded kibble diet or commercial wet canned diet and fed for 28 weeks. After 28 weeks on study, breath samples, salivary pH, and plaque samples were collected and analyzed. On week 28, gingivitis, plaque, and calculus scoring were conducted by a board-certified veterinarian that was blinded to treatments.

Oral sample collection and scores

Cats were transported to the Veterinary Teaching Hospital on the University of Illinois campus for oral sample collection and scoring. All cats had food withheld overnight, with free access to water until the morning of the procedure. First, the hair over the right cephalic vein was clipped, topical 5% lidocaine cream was applied to the catheter site, and cats were premedicated with an intramuscular injection of butorphanol (0.4 mg/kg) and alfaxalone (2 mg/kg). After 15 min, the catheter site was aseptically prepared, and a 22-gauge intravenous catheter was placed in the cephalic vein. Following catheterization, cats were administered maropitant (1 mg/kg) or physiologic saline IV and anesthesia was induced with propofol administered to effect. Topical lidocaine (0.2 mL, 2% lidocaine) was then applied to the vocal folds, cats were orotracheally intubated, and anesthesia was maintained with isoflurane (1–2%) delivered in oxygen. Intravenous fluids (Normosol-R) were delivered at 3 mL/kg/h throughout the maintenance phase of anesthesia, and vital parameters were monitored continuously using a multiparameter monitor. All anesthetic events were supervised by a board-certified veterinary anesthesiologist.

Oral sulfur-containing compounds

Halimeter measurements were conducted approximately 12 h after feeding and obtained for each cat using a clean plastic straw (i.e., a clean straw was used for each measurement) as an extension of the halimeter air drawing hose. The highest reading of volatile sulfur compounds over a period of approximately 30 s were displayed by the halimeter and recorded. The machine was allowed to return to 0 (about 60 to 120 s) before the next measurement was taken. Each cat was measured three times and a mean score calculated.

Salivary pH

Salivary pH was measured using pH strips (Fisherbrand Plastic pH Strips; pH range = 0–14). All cats had their food withheld for at least 12 h prior to salivary pH measurement, using two strips on each side of the mouth per cat (4 total). Salivary pH for each cat was reported as the mean of 4 strips.

Oral scores

Gingivitis, plaque, and calculus scoring was conducted by a blinded board-certified veterinarian according to a modified version of previous scoring systems (Mühlemann and Son, 1971; Gorrel et al., 1999). For each measurement, the canine, 3rd premolar, and 4th premolar teeth on the upper jaw (maxilla) and the canine, 3rd premolar, 4th premolar, and 1st molar teeth on the lower jaw (mandible) were scored. To assess gingivitis, after an initial visual evaluation of the gingiva, a periodontal probe (Williams model, Cislak Manufacturing, Inc., Niles, IL) was placed subgingivally on the buccal side of each tooth, and values were assigned via visual assessment of inflammation and bleeding, if present, upon probing. Each tooth was graded by the average of the three scores obtained per tooth. Plaque levels were evaluated by using Trace Disclosing Solution (#231102, Young Dental, Algonquin, IL) to cover the teeth, followed by a gentle rinse of water to remove the excess. Plaque was revealed and subsequently scored for coverage and thickness according to Gorrel et al. (13) using the anatomical landmarks described in Hennet et al. (14) to divide the teeth into gingival and occlusal portions. The gingival and occlusal values for each tooth were averaged to obtain a tooth total score. Calculus scores were based on the visual assessment of coverage and thickness on the mesial, buccal, and distal portions of the tooth. The tooth score was the average of the scores for each of the three-tooth surfaces. Pocket depth was based on height from bottom of pocket to gingival margin: 1 = 0.0–0.5 mm, 2 = 0.5–1 mm, 3 = 1–1.5 mm, 4 = 1.5–2 mm, and 5 = 2–2.5 mm. The tooth score was the average pocket depth for each tooth.

Plaque sample collection

Once teeth were scored, plaque samples were collected for microbiota and the teeth surfaces were cleaned. Teeth were assessed using a sterile periodontal probe on the gingival margin and sweeping along the base of the crown for supragingival samples, and by probing below the gingival margin for subgingival samples. Plaque samples were collected, and samples were placed into sterile 2.0 mL cryovials (Wheaton, Millville, NJ) and immediately placed on dry ice until storage at −80 °C, where they were stored until analysis.

Plaque microbiota analysis

Plaque bacterial DNA was extracted according to the manufacturer’s instructions using the DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) with bead beating using a vortex adaptor, followed by quantification of extracted DNA using a Qubit® 3.0 Fluorometer (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). DNA quality was determined using an E-Gel Power Snap Electrophoresis Device (Double Comb with SYBR, Invitrogen, Waltham, MA). 16S rRNA gene amplicons were generated using a Fluidigm Access Array (Fluidigm Corporation, South San Francisco, CA) in combination with Roche High Fidelity Fast Start Kit (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). The primers 515F (5’GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3′) and 806R (5’-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′) that target a 252 bp-fragment of the V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene were used for amplification (primers synthesized by IDT Corp., Coralville, IA) (Caporaso et al., 2012). The CS1 forward and CS2 reverse tags were added according to the Fluidigm protocol. Quality of the amplicons was assessed using a Fragment Analyzer (Advanced Analytics, Ames, IA) to confirm amplicon region and size. A DNA pool was generated by combining equimolar amounts of the amplicons from each sample. The pooled samples were then size selected on a 2% agarose E-gel (Life technologies, Grand Island, NY) and extracted using a Qiagen gel purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Cleaned size-selected pooled products were tested on an Agilent Bioanalyzer to confirm appropriate profile and average size. Illumina sequencing was performed on a MiSeq using v3 reagents (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA) at the Roy J. Carver Biotechnology Center at the University of Illinois. Forward reads of Illumina 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing were trimmed using the FASTX-Toolkit (version 0.0.14), and the resulting sequence data were analyzed using QIIME2, version 2023.7 (15). Raw sequence amplicons were imported into the QIIME2 package and analyzed by the DADA2 pipeline for quality control (QC value ≥ 20) (16). Samples were then rarefied to 33,697 reads. Subsequent samples were assigned to taxonomic groups with the SILVA database (SILVA 138 99% ASV from 515F/806R region of sequences, with the QIIME2 classifier trained on 515F/806R V4 region of 16S) (17, 18). The taxonomic classifications produced by DADA2, as well as its quantifications, were imported into phyloseq (version 1.44.0) in R (version 4.3.1). The rarefied samples were used for alpha and beta diversity analysis. Principal coordinate analysis was performed using weighted and unweighted unique fraction metric (UniFrac) distances. Analysis of compositions of microbiomes with bias correction version 2 (ANCOM-BC2) was estimated using the ANCOMBC package (version 2.4.0) to identify specific taxa responsible for the observed discrimination between treatment samples. Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p values were used, and q < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the mixed model (PROC GLIMMIX) procedure of SAS (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). The fixed effects of diet were tested. Animals were considered a random effect. Least-squares means were calculated for each variable, with post-hoc pairwise comparisons adjusted using the Tukey method. Statistical significance was determined at a threshold of p < 0.05, and pooled standard errors of the mean (SEM) were reported.

Results

Food intake averaged 51.95 ± 2.6 g/day for cats fed dry diet and 156.7 ± 6.7 g/day for those fed wet diet. Body weight (p = 0.7568) and body condition score (p = 0.8950) remained stable throughout the study and did not differ between dietary treatments (data not shown).

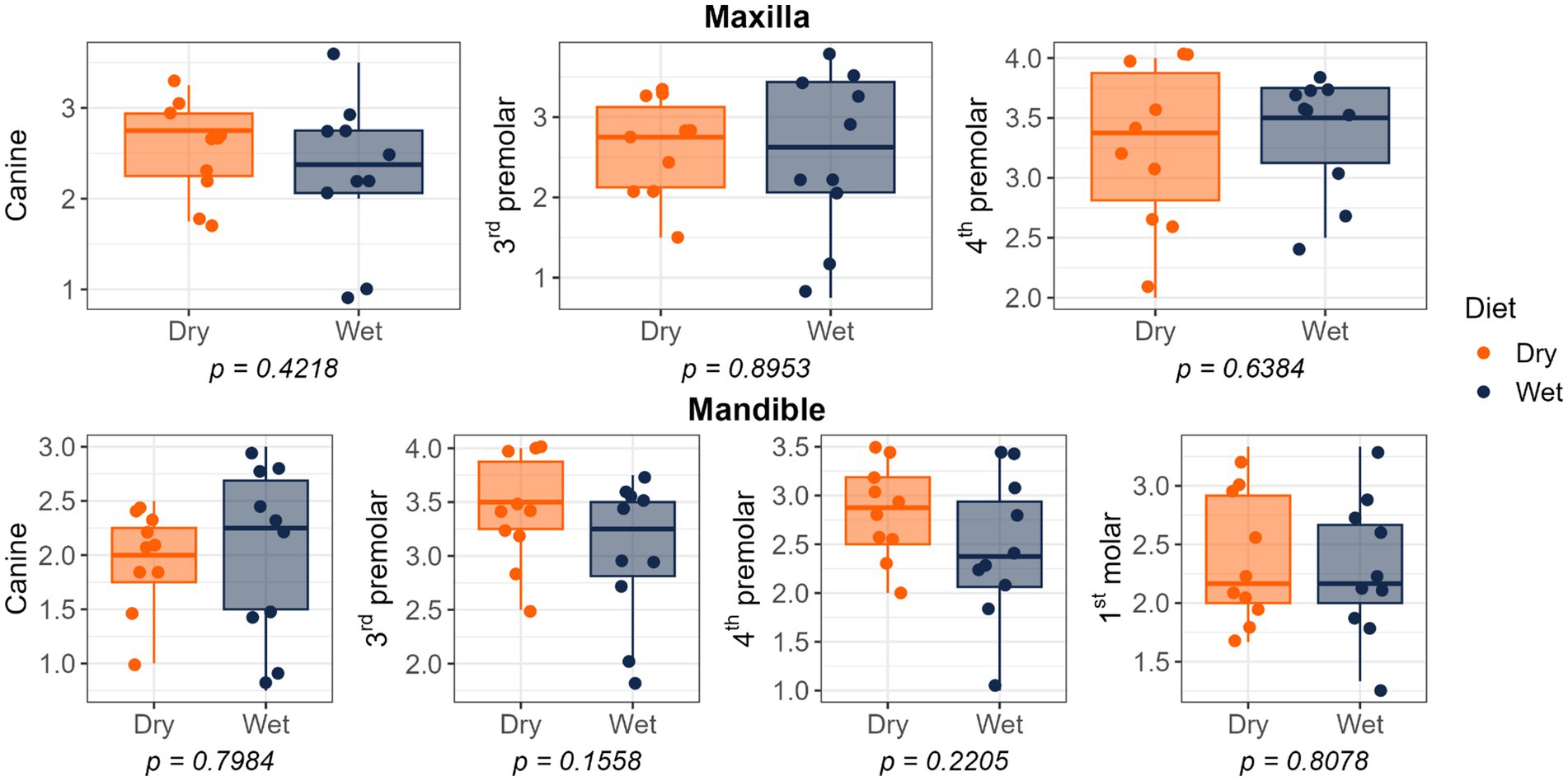

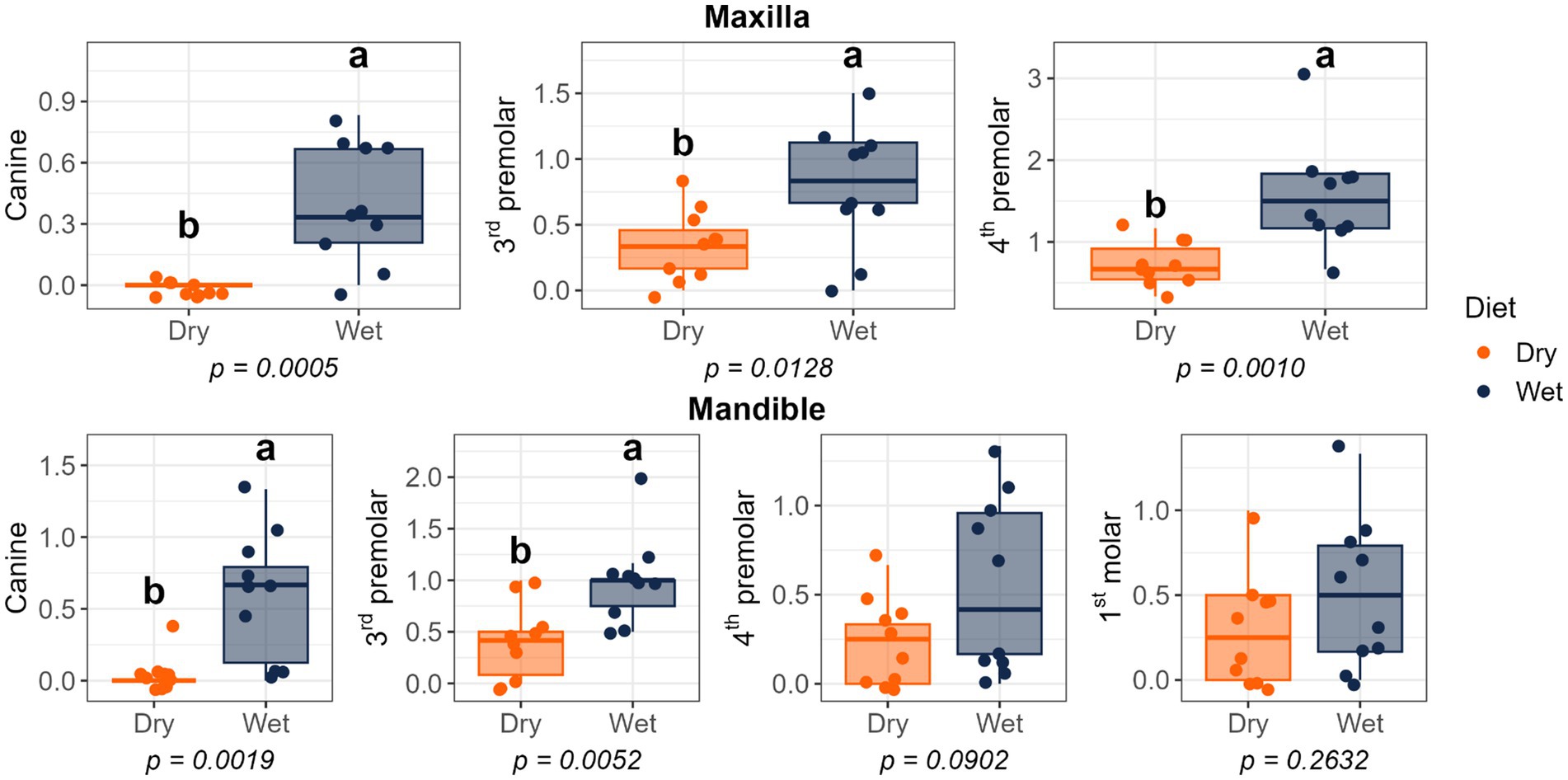

Dietary treatment had no effect on salivary pH, thiol concentrations, or volatile sulfur compound concentrations (Figure 1). However, cats fed the wet diet had higher (p < 0.05) gingivitis scores on the mandibular canine, 3rd premolar, and 1st molar teeth than those fed the dry diet (Figure 2). Pocket scores (Figure 3) and plaque coverage (Figure 4) were not impacted by dietary treatment. Plaque thickness was greater (p < 0.05) on the mandibular 3rd premolar teeth of cats fed the wet diet than those fed the dry diet (Figure 5). Calculus coverage and thickness on the maxillary canine, 3rd premolar, and 4th premolar teeth and mandibular canine and 3rd premolar teeth were higher (p < 0.05) in cats fed the wet diet than those fed the dry diet (Figures 6, 7).

Figure 1. Salivary pH, thiol concentrations, and volatile sulfur compound concentrations of cats fed commercial wet or dry diets.

Figure 2. Gingivitis scores of cats fed commercial wet or dry diets. Scores reflect the severity of gingival inflammation based on clinical presentation: 0 = no gingivitis; 1 = very mild (‘incipient’) gingivitis characterized by redness and swelling without bleeding on probing; 2 = mild gingivitis with redness, swelling, and delayed bleeding on probing; 3 = moderate gingivitis with redness, swelling, and immediate bleeding on probing; 4 = severe gingivitis with ulceration, spontaneous hemorrhage, and profuse bleeding on probing.

Figure 3. Periodontal pocket depth scores of cats fed commercial wet or dry diets. Scores indicate the depth of the gingival sulcus or periodontal pocket as follows: 1 = 0.0–0.5 mm; 2 = 0.5–1.0 mm; 3 = 1.0–1.5 mm; 4 = 1.5–2.0 mm; 5 = 2.0–2.5 mm.

Figure 4. Plaque coverage scores of cats fed commercial wet or dry diets. Scores represent the extent of plaque coverage on the buccal tooth surface, defined as follows: 0, no detectable plaque; 1, scattered plaque covering less than 24%; 2, plaque covering 25 to 49%; 3, plaque covering 50 to 74%; and 4, plaque covering more than 75%.

Figure 5. Plaque thickness scores of cats fed commercial wet or dry diets. Scores represent the severity of plaque deposits as follows: 1 = Light; 2 = Moderate; 3 = Heavy.

Figure 6. Calculus coverage scores of cats fed commercial wet or dry diets. Scores indicate the percentage of the buccal tooth surface covered by calculus: 0 = no detectable calculus; 1 = scattered calculus covering less than 24%; 2 = calculus covering 25–49%; 3 = calculus covering 50–74%; 4 = calculus covering more than 75%.

Figure 7. Calculus thickness scores of cats fed commercial wet or dry diets. Scores represent the thickness of calculus deposits as follows: 1 = thickness less than 0.5 mm; 2 = thickness between 0.5 and 1.0 mm; 3 = thickness greater than 1.0 mm.

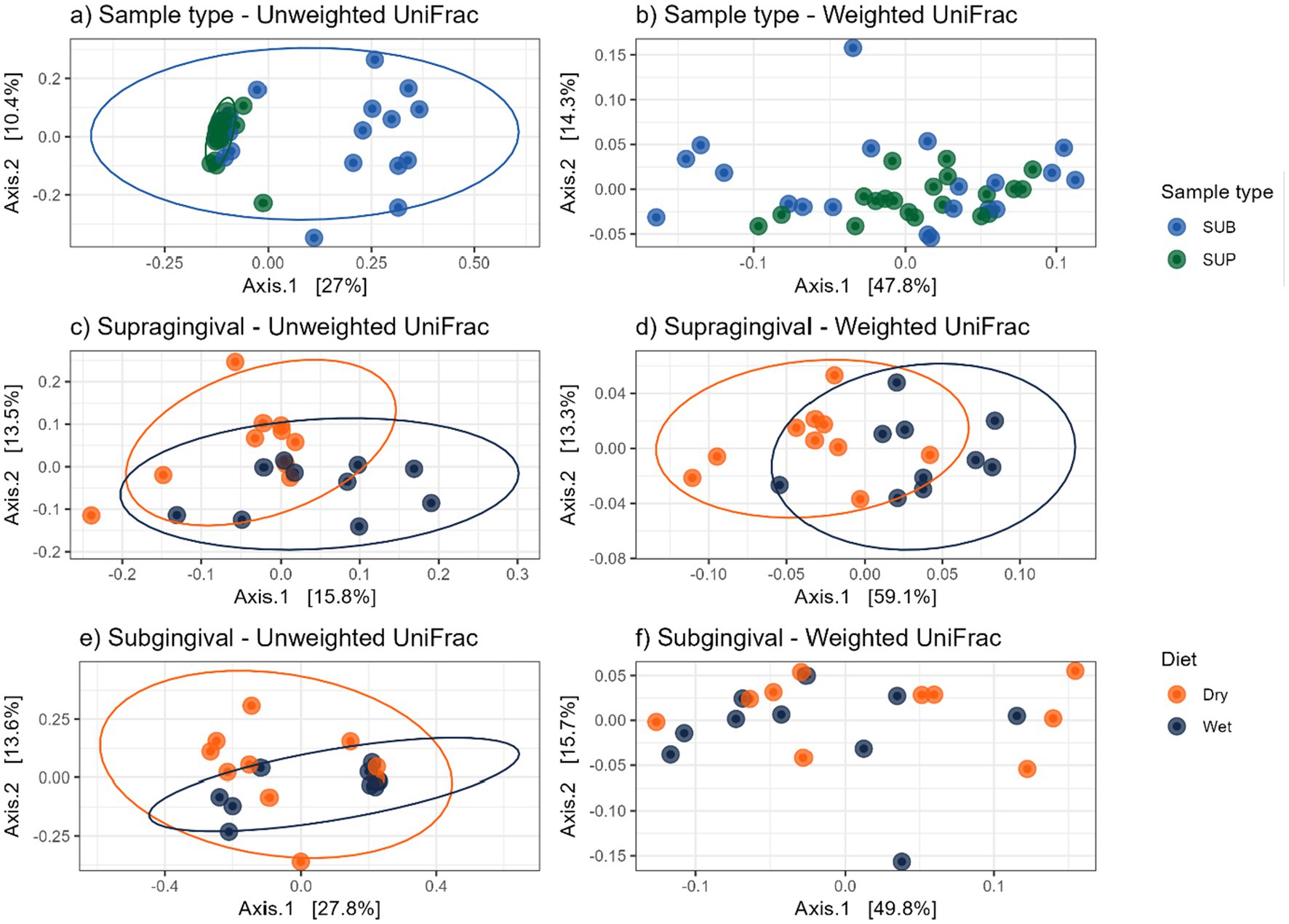

Bacterial alpha diversity measures (i.e., observed features, Shannon Index, Fisher Index) were lower (p < 0.05) in supragingival samples of cats fed the wet diet than those fed the dry diet, but no differences were detected between sample sites or within diet of subgingival samples (Figure 8). Bacterial beta diversity analysis according to unweighted UniFrac distances demonstrated separation between supragingival and subgingival samples. Beta diversity analysis using unweighted UniFrac revealed differences between cats fed wet and dry diets in both sample sites, while weighted UniFrac distances only detected diet-related differences in supragingival samples (Figure 9).

Figure 8. Bacterial alpha diversity measures of plaque samples from cats fed commercial wet or dry diets: (a) supragingival (SUP) vs. subgingival (SUB) plaque, (b) wet vs. dry diets within supragingival samples, and (c) wet vs. dry diets within subgingival samples. Observed = observed features, Shannon = Shannon Index, InvSimpson = inverse Simpson Index, Fisher = Fisher Index.

Figure 9. Bacterial beta diversity measures of plaque samples from cats fed wet or dry diets, shown by principal coordinate analysis plots based on UniFrac distances: (a) unweighted and (b) weighted UniFrac distances comparing supragingival (SUP) and subgingival (SUB) samples; (c) unweighted and (d) weighted UniFrac distances comparing supragingival plaque samples of cats fed dry or wet diets; (e) unweighted and (f) weighted UniFrac distances comparing subgingival plaque samples of cats fed dry or wet diets.

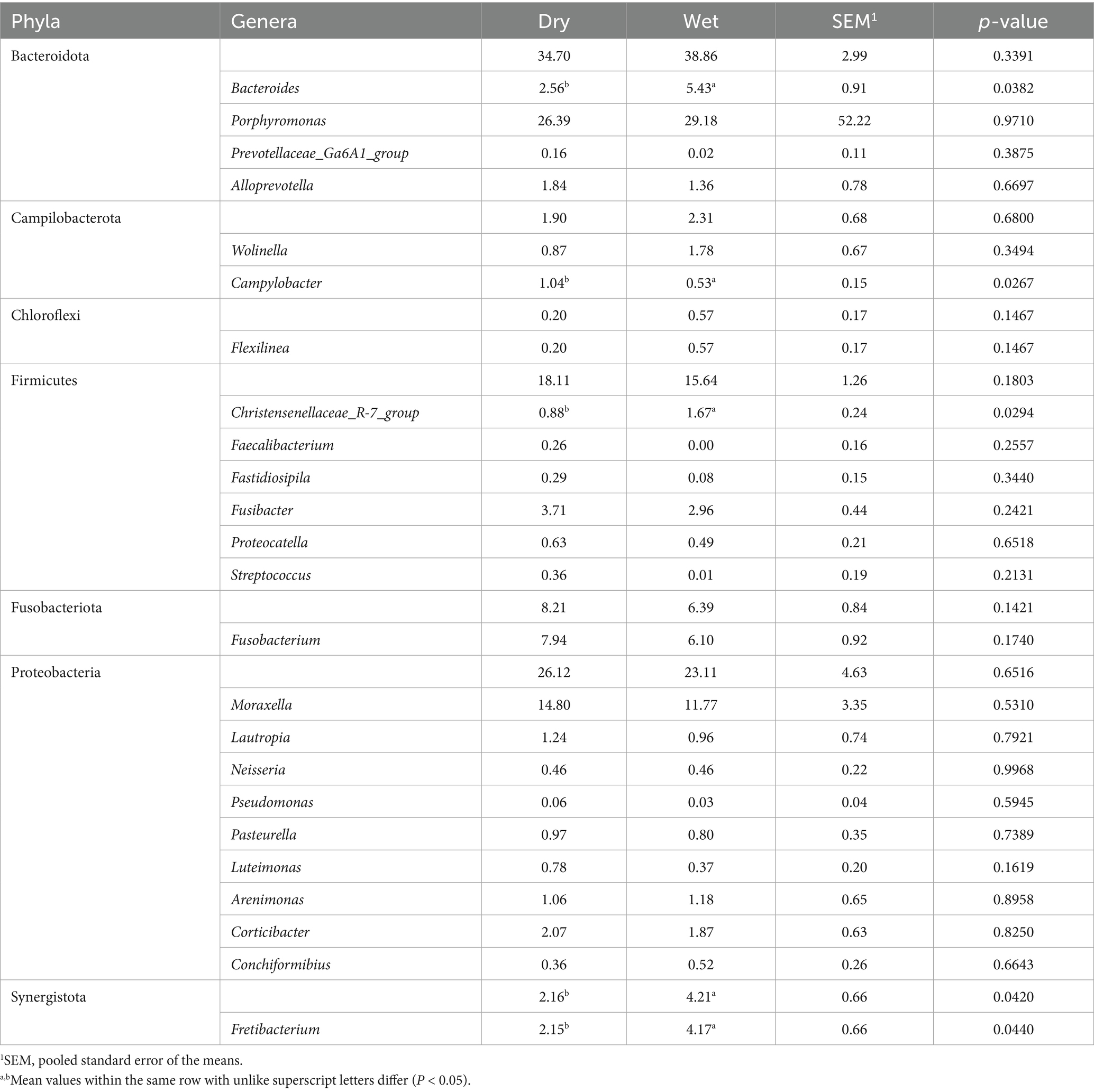

Bacteroidota and Proteobacteria were the predominant bacterial phyla, while Porphyromonas and Moraxella were the most abundant bacterial genera, in supragingival and subgingival samples (Figure 10). Relative abundances of Bacteroidota, Bacteroides, Campylobacter, and Christensenellaceae R-7 group were more (p < 0.05) abundant in supragingival plaque samples than subgingival plaque samples, whereas Fusobacteriota, Wolinella, Fusobacterium, Luteimonas, and Conchiformibius relative abundances were greater (p < 0.05) in subgingival plaque samples than supragingival samples (Table 2). Compared with cats fed the dry diet, those fed the wet diet had higher (p < 0.05) relative abundances of Bacteroidota and Bacteroides in supragingival plaque samples. In contrast, cats fed the dry diet had higher (p < 0.05) relative abundances of Proteobacteria, Streptococcus, Luteimonas, and Lautropia than those fed the wet diet (Table 3). In subgingival plaque samples, the relative abundances of Synergistota, Bacteroides, Fretibacterium, Campylobacter, and the Christensenellaceae R-7 group were greater (p < 0.05) in cats fed the wet diet than those fed the dry diet (Table 4).

Figure 10. Relative abundances of bacterial taxa at the phylum and genus levels in supragingival and subgingival plaque samples from cats fed dry or wet diets. Panels show phylum-level composition (a) and genus-level composition (b) for supragingival and subgingival samples. Taxa with relative abundance ≤1% across all samples were grouped under “Others.”

Table 2. Relative abundances (% of sequences) of predominant bacterial phyla and genera in the supragingival and subgingival plaque of cats.

Table 3. Relative abundances (% of sequences) bacterial phyla and genera in the supragingival plaque of cats fed commercial wet or dry diets.

Table 4. Relative abundances (% of sequences) of bacterial phyla and genera in the subgingival plaque of cats fed commercial wet or dry diets.

Analysis of composition of microbiomes with bias correction (ANCOM-BC2) revealed that the relative abundances of Leptotrichia, Conchiformibius, and Allobaculum were lower (p < 0.05) and the relative abundance of Corynebacterium was higher (p < 0.05) in supragingival plaque than in subgingival plaque. Additionally, the relative abundances of Bergeyella, Capnocytophaga, Corynebacterium, Flavobacterium, Gracilibacteria, Lautropia, Luteimonas, and Streptococcus were lower (p < 0.05) in supragingival plaque samples of cats fed the wet diet than those fed the dry diet (Figure 11). No diet-related differences were observed in subgingival plaque samples.

Figure 11. Analysis of composition of microbiomes with bias correction (ANCOM-BC2) identified differentially abundant bacterial genera of feline plaque samples (q < 0.05): (a) supragingival vs. subgingival plaque samples, (b) supragingival samples of cats fed a wet vs. a dry diet.

Discussion

Insights into the feline oral microbiome and the factors that shape its composition are still relatively limited. In our study, the overall bacterial profile, particularly the distribution of dominant phyla and the detection of key genera, closely aligned with previously reported patterns. The dominant phyla included Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, and Firmicutes, with Porphyromonas identified as the most prevalent genus (10, 19, 20).

To our knowledge, this study is the first to compare supragingival and subgingival plaque samples in cats. Supragingival plaque, which accumulates on the tooth surface above the gum line, is characterized by a high abundance of gram-positive aerobic bacteria. Its development is a prerequisite for the establishment of subgingival plaque within the gingival sulcus, where gram-negative anaerobic bacteria are highly abundant. Periodontal disease results from both the direct effects of these microorganisms and their byproducts on periodontal tissues, and the indirect effects mediated by the host immune response, leading to inflammation and tissue destruction (21, 22). Thus, distinguishing the differences between these sites may provide valuable insights into feline oral health.

In dogs, bacterial alpha diversity measures (i.e., observed features, Shannon Index, Faith’s phylogenetic diversity) have been reported to be higher in subgingival than supragingival samples. However, no distinct separation between subgingival and supragingival sites was observed in beta diversity analyses using unweighted and weighted UniFrac distances. Taxonomic differences were evident, with higher relative abundances of Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, Corynebacterium, Enhydrobacter, and Moraxella in supragingival samples. In contrast, subgingival samples were enriched in Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, Spirochaetes Porphyromonas, Fusibacter, Fusobacterium, Treponema, and Campylobacter (23). Another study in dogs demonstrated that the subgingival habitat harbors significantly higher proportions of Prevotella intermedia, Streptococcus constellatus, Campylobacter rectus, and Campylobacter showae, whereas the proportion of Actinomyces naeslundii was significantly lower. Additionally, lower proportions of Parvimonas micra, Fusobacterium nucleatum ss. polymorphum, and Streptococcus intermedius were observed in supragingival plaque (24).

In contrast to what has been reported in dogs, the present study did not detect any differences in alpha diversity measures between the supragingival and subgingival samples of cats. However, beta diversity analysis revealed clear clustering by sample type, indicating distinct microbial community compositions between the two sites. Notably, Campylobacter was enriched in supragingival samples, which contrasts with the findings in dogs. In agreement with the canine data, Fusobacterium was enriched in subgingival samples. Moreover, several bacterial taxa differed between supragingival and subgingival samples in cats that were not reported in dog studies, underscoring the need for further studies in cats that may identify the core oral bacterial communities.

Regarding dietary effects, a previous study reported that cats fed a dry diet had higher oral bacterial alpha diversity measures than those fed a wet diet. Cats fed a dry diet also had an enrichment of bacterial genera such as Actinobacillus, Acholeplasma, Treponema, and Porphyromonas, while cats fed a wet diet had higher levels of Proteobacteria in their dental plaque (10). In dogs, dry diet consumption was similarly associated with increased abundances of bacterial taxa linked with oral health, including Pasteurella, Capnocytophaga, and Corynebacterium, lower abundances of known oral pathogens such as Fretibacterium fastidiosum, Filifactor alocis, Treponema medium, Tannerella forsythia, Porphyromonas canoris, and Porphyromonas gingivalis, and higher bacterial alpha diversity measures in supragingival plaque (2).

Similarly, in the present study, cats fed a dry diet had greater alpha diversity in their supragingival plaque microbiomes. Furthermore, Capnocytophaga and Corynebacterium had similar enrichment patterns as those reported previously. Additionally, we observed increased abundances of genera such as Bergeyella, Flavobacterium, Gracilibacteria, Lautropia, Luteimonas, and Streptococcus in the supragingival plaque of cats fed a dry diet, whereas Bacteroides was more abundant in the supragingival plaque of cats fed the wet diet. Notably, Capnocytophaga and Bergeyella have been described as dominant genera in the healthy feline oral cavity (19, 25), and also were identified as a core oral microbiome in cats (19, 20). In healthy cats, these taxa, along with Corynebacterium, Flavobacterium, Lautropia, Luteimonas, and Streptococcus, are present at higher abundances than cats affected by chronic gingivostomatitis, which have increased Porphyromonas, Bacteroides, Treponema, Tannerella, Peptostreptococcus, and Fusobacterium abundances (26). Collectively, our data indicate that consumption of a dry diet is associated with a higher oral bacterial alpha diversity and a higher relative abundance of health-associated bacterial taxa in feline supragingival plaque, suggesting potential benefits for oral health.

Calculus formation and gingivitis development are critical factors in the progression of periodontal disease, as both increase as oral health declines. The close relationship between the extent of calculus and gingivitis reflects worsening dental health. Dental calculus is a hardened, mineralized form of plaque that develops when plaque is exposed to calcium and phosphate ions in saliva and crevicular fluid. Mineralization can begin within 48 h of plaque accumulation. Calculus may form both supragingivally and subgingivally, and its development is influenced by oral pH and diet. While bacterial plaque is the primary cause of periodontal disease, calculus contributes by providing a rough surface that promotes bacterial adhesion, plaque accumulation, and irritation of the gingival tissues (3, 27). Studies have shown that dental calculus and plaque are less common in cats fed dry diets than those fed wet diets (8). Similarly, dogs fed dry extruded diets have reduced plaque buildup and improved breath odor, supporting the potential oral health benefits of dry diet (2). This difference is often attributed to the abrasive nature of dry diet, which aids in mechanically removing dental plaque, whereas wet or soft diets have been linked to poorer dental health outcomes (8, 28). Additionally, consumption of a dry diet stimulates greater saliva production, which contains immunoglobulins that can enhance the oral immune response and help prevent dental problems (29). Furthermore, incisors in young and adult cats fed dry diets were less likely to have high oral health scores than premolars and molars (cheek teeth) in older cats consuming diets with a wet component. Cheek teeth generally scored higher, even in younger cats, but predominantly when fed wet commercial or homemade (soft) diets. Overall, diet and tooth type were identified as key factors driving variability in oral health scores and thus significantly influencing feline oral health status (9).

In the present study, no differences in salivary pH were observed between dietary treatments; however, consistent with these findings, cats fed a wet diet had higher calculus scores at multiple sites on the maxilla and mandible (including canines and premolars), along with increased gingivitis scores on the mandible at the canines, premolars, and molars. Interestingly, plaque accumulation was greater on the mandibular premolars of cats consuming dry diets. This difference may be explained by the anatomical characteristics of premolars and molars, which are larger teeth positioned deeper within the cheek, making it more difficult for the tongue to clean them effectively. This environment promotes food retention, encouraging bacterial growth and increasing the risk of plaque and gingivitis. Moreover, premolars and molars, which play a primary role in mastication, often have diastemata (i.e., space between teeth) more frequently than incisors, further facilitating food entrapment. In contrast, incisors not only assist in biting but also contribute to grooming and self-cleaning behaviors, resulting in greater abrasion that helps reduce plaque formation (9).

This study had some limitations, including a small sample size and a focus on a single cat breed. Future research should explore a wider range of dietary formats, including differences in moisture content and processing methods, to better understand how variations in texture and density influence oral health outcomes and microbiota composition. Additionally, investigating the effects of varying protein, carbohydrate, and fat concentrations may provide insight into how macronutrient content shapes oral microbial populations. Lastly, because cat breeds differ in jaw structure, tooth spacing, orientation, and potentially their susceptibility to periodontal disease, it is recommended that future studies include multiple breeds to capture this variability.

Although many oral health measures did not differ between diet groups, this study showed that cats fed a dry diet had reduced calculus accumulation and a more diverse oral microbiome enriched with bacteria associated with oral health and a lower risk of periodontal disease than those fed a wet diet. These results indicate that diets commonly fed to domestic cats in the United States can significantly influence the composition and diversity of the feline oral microbiota. Nevertheless, further research is needed to understand how these microbial changes affect biofilm development, plaque and calculus buildup, and the progression of periodontal disease in cats.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are publicly available. These data can be found here: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/, SRA: SRP627208 and BioProject: PRJNA1334357.

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by the University of Illinois Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

PO: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – original draft. OS: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. GP: Investigation, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. CD: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. SS: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Data curation. KS: Resources, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Gorrel, C. Periodontal disease and diet in domestic pets. J Nutr. (1998) 128:S2712–4. doi: 10.1093/jn/128.12.2712S

2. Oba, PM, Sieja, KM, Keating, SCJ, Hristova, T, Somrak, AJ, and Swanson, KS. Oral microbiota populations of adult dogs consuming wet or dry foods. J Anim Sci. (2022) 100. doi: 10.1093/jas/skac200

3. Logan, EI. Dietary influences on periodontal health in dogs and cats. Vet Clin N Am Small Anim Pract. (2006) 36:1385–401. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2006.09.002

4. Burwasser, P, and Hill, TJ. The effect of hard and soft diets on the gingival tissues of dogs. J Dent Res. (1939) 18:389–93. doi: 10.1177/00220345390180040801

5. Krasse, B. Effect of consistency of diet on bacteria in gingival pockets in dogs. Odontol Revy. (1960) 11:152–65.

6. Saxe, SR, Greene, JC, Bohannan, HM, and Vermillion, JR. Oral debris, calculus, and periodontal disease in the beagle dog. Periodontics. (1967) 5:217–25.

7. Egelberg, J. Local effect of diet on plaque formation and development of gingivitis in dogs. III. Effect of frequency of meals and tube feeding. Odontol Revy. (1965) 16:50–60.

8. Gawor, JP, Reiter, AM, Jodkowska, K, Kurski, G, Wojtacki, MP, and Kurek, A. Influence of diet on oral health in cats and dogs. J Nutr. (2006) 136:2021–3. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.7.2021s

9. Mata, F. The choice of diet affects the oral health of the domestic cat. Animals 2015, vol. 5, pages 101-109. Animals. (2015) 5:101–9. doi: 10.3390/ANI5010101

10. Adler, CJ, Malik, R, Browne, GV, and Norris, JM. Diet may influence the oral microbiome composition in cats. Microbiome. (2016) 4:23–9. doi: 10.1186/s40168-016-0169-y

11. Laflamme, D. Development and validation of a body condition score system for cats: a clinical tool. Feline Pract. (1997) 25:13–8.

13. Gorrel, C, Inskeep, G, and Inskeep, T. Benefits of a “dental hygiene chew” on the periodontal health of cats. J Vet Dent. (1998) 15:135–8. doi: 10.1177/089875649801500304

14. Hennet, P, Servet, E, Salesse, H, and Soulard, Y. Evaluation of the Logan & Boyce plaque index for the study of dental plaque accumulation in dogs. Res Vet Sci. (2006) 80:175–80. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2005.05.006

15. Caporaso, JG, Kuczynski, J, Stombaugh, J, Bittinger, K, Bushman, FD, Costello, EK, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods. (2010) 7:335–6. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303

16. Callahan, BJ, McMurdie, PJ, Rosen, MJ, Han, AW, Johnson, AJA, and Holmes, SP. DADA2: high-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat Methods. (2016) 13:581–3. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3869

17. Bokulich, NA, Kaehler, BD, Rideout, JR, Dillon, M, Bolyen, E, Knight, R, et al. Optimizing taxonomic classification of marker-gene amplicon sequences with QIIME 2’s q2-feature-classifier plugin. Microbiome. (2018) 6:90. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0470-z

18. Robeson, MS, O’Rourke, DR, Kaehler, BD, Ziemski, M, Dillon, MR, Foster, JT, et al. RESCRIPt: Reproducible sequence taxonomy reference database management. PLoS Comput Biol. (2021) 17:e1009581. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009581

19. Harris, S, Croft, J, O’Flynn, C, Deusch, O, Colyer, A, Allsopp, J, et al. A pyrosequencing investigation of differences in the feline subgingival microbiota in health, gingivitis and mild periodontitis. PLoS One. (2015) 10:e0136986. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136986

20. Sturgeon, A, Pinder, SL, Costa, MC, and Weese, JS. Characterization of the oral microbiota of healthy cats using next-generation sequencing. Vet J. (2014) 201:223–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2014.01.024

21. Harvey, CE. Management of periodontal disease: understanding the options. Vet Clinics North America. (2005) 35:819–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2005.03.002

22. Schroeder, HE, and Attström, R. Effect of mechanical plaque control on development of subgingival plaque and initial gingivitis in neutropenic dogs. Eur J Oral Sci. (1979) 87:279–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1979.tb00683.x

23. Oba, PM, Carroll, MQ, Alexander, C, Valentine, H, Somrak, AJ, Keating, SCJ, et al. Microbiota populations in supragingival plaque, subgingival plaque, and saliva habitats of adult dogs. Anim Microbiome. (2021) 3:38. doi: 10.1186/s42523-021-00100-9

24. Rober, M, Quirynen, M, Haffajee, AD, Schepers, E, and Teughels, W. Intra-oral microbial profiles of beagle dogs assessed by checkerboard DNA–DNA hybridization using human probes. Vet Microbiol. (2008) 127:79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2007.08.007

25. Dolieslager, SMJ, Riggio, MP, Lennon, A, Lappin, DF, Johnston, N, Taylor, D, et al. Identification of bacteria associated with feline chronic gingivostomatitis using culture-dependent and culture-independent methods. Vet Microbiol. (2011) 148:93–8. doi: 10.1016/J.VETMIC.2010.08.002

26. Anderson, JG, Rojas, CA, Scarsella, E, Entrolezo, Z, Jospin, G, Hoffman, SL, et al. The Oral microbiome across Oral sites in cats with chronic Gingivostomatitis, periodontal disease, and tooth resorption compared with healthy cats. Animals. (2023) 13:3544. doi: 10.3390/ANI13223544

27. Loux, JJ, Alioto, R, and Yankell, SL. Effects of glucose and urea on dental deposit pH in dogs. J Dent Res. (1972) 51:1610–3. doi: 10.1177/00220345720510061801

28. Watson, ADJ. Diet and periodontal disease in dogs and cats. Aust Vet J. (1994) 71:313–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1994.tb00905.x

29. Harley, R, Gruffydd-Jones, TJ, and Day, MJ. Salivary and serum immunoglobulin levels in cats with chronic gingivostomatitis. Vet Rec. (2003) 152:125–9. doi: 10.1136/vr.152.5.125

Abbreviations

AAFCO, Association of American Feed Control Officials; ANCOMBC, Analysis of Compositions of Microbiomes with Bias Correction; AOAC, Association of Official Analytical Chemists; SEM, Pooled standard error of the means; UniFrac, Unique fraction metric.

Keywords: plaque microbiota, oral health, microbiota modulation, biofilm, microbial diversity

Citation: Oba PM, Swanson OR, Pavlovsky G, Dupleix CR, Sharping SCJ and Swanson KS (2025) Oral health indices and microbiota populations of adult cats consuming wet or dry diets. Front. Vet. Sci. 12:1678016. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2025.1678016

Edited by:

Sergio Andres Castañeda, Rosario University, ColombiaReviewed by:

Vidya V. Jadhav (Patil), North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University, United StatesCopyright © 2025 Oba, Swanson, Pavlovsky, Dupleix, Sharping and Swanson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kelly S. Swanson, a3Nzd2Fuc29AaWxsaW5vaXMuZWR1

Patrícia M. Oba

Patrícia M. Oba Olivia R. Swanson

Olivia R. Swanson Gene Pavlovsky

Gene Pavlovsky Chloe R. Dupleix2

Chloe R. Dupleix2 Stephanie C. J. Sharping

Stephanie C. J. Sharping Kelly S. Swanson

Kelly S. Swanson