- 1Laboratory for Technologies of Cultivation of Microorganisms, Research Institute for Biological, Safety Problems, QazBioPharm, Guardeyskiy, Kazakhstan

- 2Laboratory for Control of Technologies and Biopreparations, Research Institute for Biological Safety Problems, QazBioPharm, Guardeyskiy, Kazakhstan

- 3Laboratory for Collection of Microorganisms, Research Institute for Biological Safety Problems, QazBioPharm, Guardeyskiy, Kazakhstan

- 4Laboratory for Technologies of Finished Forms of Biological Preparations, Research Institute for Biological Safety Problems, QazBioPharm, Guardeyskiy, Kazakhstan

- 5Laboratory for Monitoring of Infectious Diseases, Research Institute for Biological Safety Problems, QazBioPharm, Guardeyskiy, Kazakhstan

- 6QazBioPharm, Astana, Kazakhstan

- 7Department of Biological Safety, Faculty of Veterinary and Zooengineering, Kazakh National Agrarian Research University, Almaty, Kazakhstan

Some of the most economically significant viral infections affecting cattle globally include infectious bovine rhinotracheitis (IBR) and bovine viral diarrhea (BVD). Both viruses cause a wide range of clinical consequences and significant economic losses. Recent serological surveillance in Kazakhstan showed that these infections persist despite commercial vaccines, underscoring the need for more effective, locally appropriate immunization protocols. This study aimed to evaluate the duration of immunity conferred by a developed associated inactivated emulsion vaccine against IBR (strain “R-93”) and BVD (strain “Oregon C24V”), produced by the Research Institute for Biological Safety Problems. In the southern region of Kazakhstan. Of the 12 seronegative for BoHV-1 and BVDV clinically healthy crossbred calves (Friesian-Holstein and Kazakh Whiteheaded) eight were vaccinated, revaccinated, and monitored over a 9-month period for evaluation of the vaccine. Humoral immune responses were assessed using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and virus neutralization assays. Specific antibodies to BoHV-1 and BVDV were detected as early as day 7 post-vaccination, with titers peaking at 6.16 log2 and 6.24 log2, respectively, by day 28, and remaining above protective levels for at least 6 months. At 9 months, a challenge was conducted using virulent strains: no clinical signs or lesions in vaccinated animals, fever and respiratory systems in unvaccinated animals. These findings suggest that the tested inactivated vaccine is safe, immunogenic, and capable of providing sustained protection in crossbred cattle under local climatic conditions. Although the sample size was limited, the results allow us to make preliminary conclusions about the vaccine’s efficacy; however, further large-scale studies are needed.

1 Introduction

Infectious bovine rhinotracheitis (IBR) and bovine viral diarrhea (BVD) are among the most prevalent and economically significant viral diseases affecting cattle worldwide (1–8). They are caused by bovine herpesvirus type 1 (BoHV-1) (9) and bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) (10), respectively. Both pathogens are associated with a wide range of clinical manifestations, including respiratory, reproductive, and immunosuppressive disorders in cattle populations (11–13). Modern strategies for the prevention and control of these diseases rely on the use of associated vaccines, designed to induce immunity against multiple pathogens simultaneously (14). Such vaccines offer practical advantages, including a reduced number of injections and decreased animal stress. However, it is important to emphasize that the duration of vaccine-induced immunity can vary considerably depending on factors such as environmental stressors (15), the age of the animal (16) or the vaccine type (17). While modified-live vaccines against IBR and BVD may be associated with adverse effects such as abortion, inactivated vaccines are generally considered safe, including for pregnant cows (18, 19). These factors may directly impact vaccine effecacy under specific regional conditions.

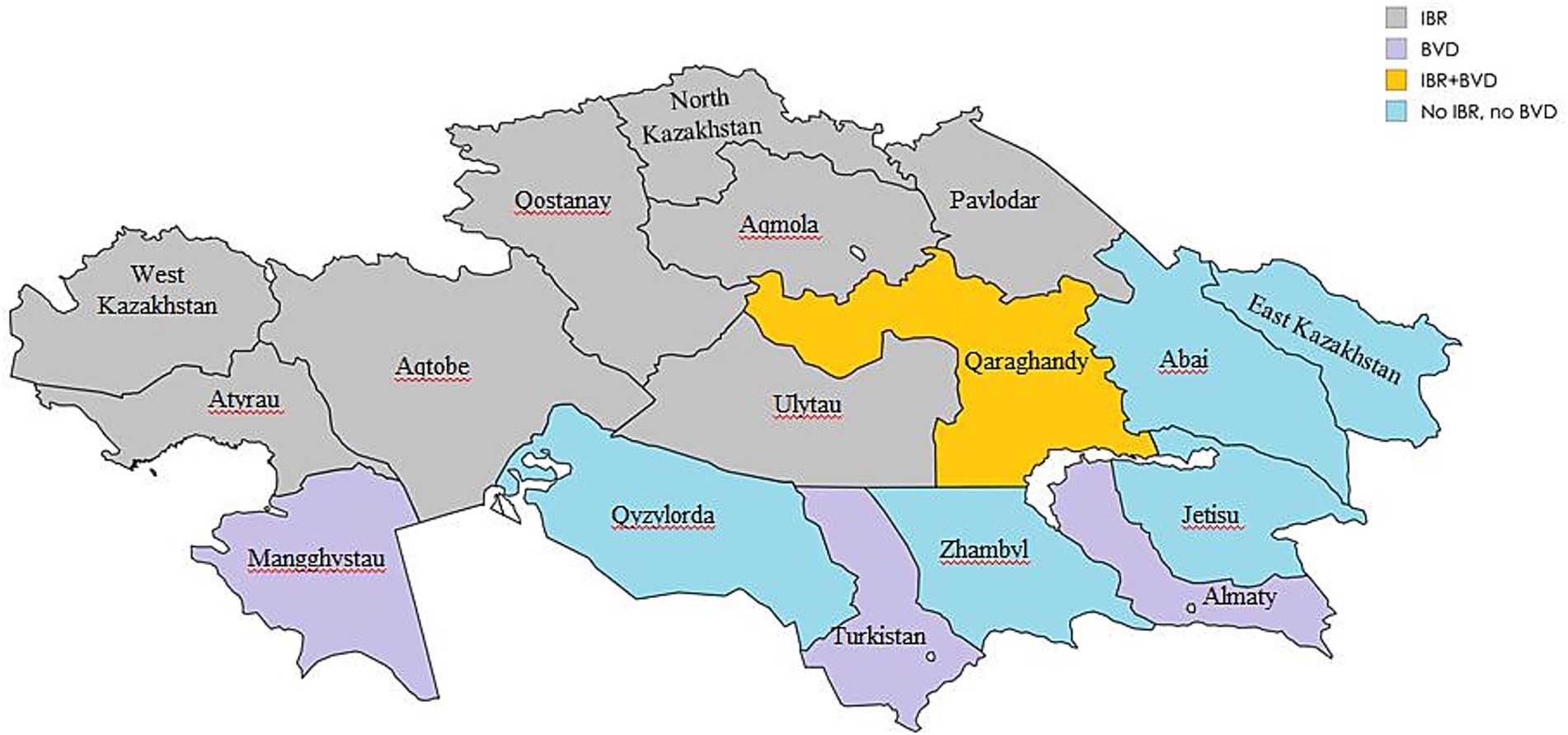

In Kazakhstan, IBR and BVD control strategies have depended on imported vaccines from Russia and the United States (20). Nevertheless, recent seroepidemiological studies (21, 22) have indicated ongoing circulation of both BoHV-1 and BVDV among cattle herds across various regions of the country (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Regional seroprevalence of IBR and BVD in Kazakhstan 2021–2024 (Map generated using mapchart.net).

To solve this issue, the Research Institute for Biological Safety Problems (RIBSP) has developed a domestically produced associated inactivated vaccine against IBR and BVD. The current study aims to evaluate the duration of immunity induced by this vaccine in crossbred cattle (Friesian-Holstein and Kazakh Whiteheaded) raised under typical conditions in the southern region of Kazakhstan. This research provides important insights into the vaccine’s immunogenicity and the longevity of protection in locally adapted cattle breeds.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Vaccine and virus strains

The associated inactivated vaccine was developed using the “R-93” strain of BoHV-1 (23) and the “Oregon C24V” strain of BVDV (24). Both strains are stored in the Laboratory for Collection of Microorganisms of the Research Institute for Biological Safety Problems (RIBSP). The technology for preparing the vaccine is detailed in the study by Bulatov et al. (25). For challenge studies, the “Oregon C24V” strain of BVDV and the “Colorado-1” strain of BoHV-1 (VR-864™), obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), Manassas, Virginia, USA (26), were used.

2.2 Cell cultures

Two cell cultures were used in this study. The Madin-Darby bovine kidney (MDBK) cell line (CCL-22™) was obtained from ATCC (27). Primary lamb testicle (LT) cell cultures were prepared in the Laboratory for Cell Biotechnology of RIBSP. Parameters and conditions for cell cultivation are described in Bulatov et al. (25).

2.3 Animals

Specific consent procedures were not required for this study. There are no client-owned animals. Calves owned by the Department of Experimental Animals of the RIBSP. All animals were pre-screened for antibodies (Abs) against BoHV-1 and BVDV using ELISA. Only clinically healthy and seronegative Bos taurus calves were enrolled to exclude interference from pre-existing immunity. 12 clinically healthy and seronegative animals aged 6–12 months were selected. The cohort included 7 heifers and 3 bulls. All animals had ad libitum access to feed and water throughout the experiment. Of the 12 calves enrolled in the study, eight were allocated to the vaccination group. The vaccinated animals were used to assess both the immunogenicity and protective efficacy of the vaccine. While four calves were left unvaccinated and served as controls in the challenge experiment.

2.4 Vaccination protocol

8 calves were vaccinated intramuscularly in the middle third of the neck with 2 mL of the vaccine. A booster dose of 2 mL was administered 21 days after the primary vaccination.

2.5 Serum sample collection

Blood samples were collected prior to vaccination (day 0), weekly for the first 5 weeks, and then monthly for 9 months to evaluate the duration of the immune response. Blood was drawn from the jugular vein using vacutainer tubes with gel and clot activator. Tubes were labeled with serial numbers, and their decoding (ear tag numbers) was recorded in a special journal. After collection, samples were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h, then cooled to 2–8 °C to allow clotting. Serum was separated by centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 15 min and stored at −20 °C until analysis.

2.6 Serological analysis

Abs against BoHV-1 were qualitatively detected using the “PrioCHECH™ BHV-1 gB ELISA Kit” (Thermo Scientific, Massachusetts, USA), and BDBV Abs were detected using the “BVD-80 antibody ELISA kit” (RingBio, Beijing, China). Reactions were performed according to the instructions of the kit manufacturers. Optical density was measured at 450 nm using a Multiskan SkyHigh microplate spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Massachusetts, USA). Ab titers were also measured quantitatively using virus neutralization assays (VNA) based on the neutralization of cytopathic effect, as described by Raizman et al. (28). MDBK cells were used for BoHV-1 VNA, and LT cells for BVDV VNA.

2.7 Challenge study design

To assess vaccine efficacy, a challenge study was conducted 9 months post-booster. The timing was based on expected protective titers, as described by Frey (29), where protective thresholds were VNA ≥ 2 log2 for BoHV-1 and ≥3 log2 for BVDV. In our study, similar titers were observed at 9 months post-vaccination, prompting challenge initiation.

The ear tag numbers of the vaccinated calves were randomly assigned using the GraphPad QuickCalcs randomization tool (30) into 2 groups: Group A (n = 2): vaccinated, challenged with strain “Colorado-1” of BoHV-1; Group B (n = 2): vaccinated, challenged with strain “Oregon C24V” of BVDV. The numbers on the ear tags of 4 non-vaccinated calves were randomly assigned into 3 groups: Group C (n = 1): unvaccinated, challenged with strain “Colorado-1” of BoHV-1; Group D (n = 1): unvaccinated, challenged with strain “Oregon C24V” of BVDV; Group E (n = 2): unvaccinated, unchallenged. The challenge inoculum was administered intranasally via animal-specific endotracheal tubing (Raino LLP, Almaty, Kazakhstan) at a dose of 1.5 mL/nostril. Clinical signs (fever, nasal discharge, conjunctivitis, appetite loss) were monitored daily for 10 days post-challenge. Veterinarians conducting the challenge were not blinded to group allocation; however, observers recording clinical signs were blinded to minimize bias. To ensure observer blinding, all calves were identified by serial numbers. Observers were instructed solely to monitor and record clinical signs without access to vaccination records.

On the 5th day after challenge, one calf from Group C was humanely euthanized in accordance with the AVMA Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals, 2020 and Large Animal Humane Euthanasia Guidelines, provided by UW School of Veterinary Medicine, 2024, to alleviate suffering. The calf was rendered unconscious by intravenous administration of xylazine (0.1 mg/kg body weight), followed by midazolam (0.1 mg/kg body weight). Once complete loss of consciousness was confirmed (no response to tactile stimulation), exsanguination was performed by transection of the carotid arteries and jugular veins.

2.8 Hematological evaluation

Hematological analysis was not included in the initial experimental design. It was performed ad hoc after observing severe clinical disease in the unvaccinated calf challenged with BoHV-1. Blood samples were collected on the 5th day after infection from Groups A, C, and E for complete blood count (CBC) analysis using the Abacus Junior5 Vet hematology analyzer (Diatron MI Zrt, Budapest, Hungary) (31). This time point was selected because it coincided with the peak of clinical sings followed by euthanasia. Parameters measured included erythrocyte (RBC), leukocyte (WBC) and platelet (PLT) counts, hemoglobin concentration (HGB), mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC).

2.9 Ethical approval

This study did not involve any client-owned animals. All animals used were owned by the Research Institute for Biological Safety Problems and were managed solely by institutional staff. All procedures complied with animal welfare regulations and biosafety protocols approved by the RIBSP Ethics Committee (Approval No. 1–14-07-2023), in accordance with national standards for the care and use of experimental animals, AVMA Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals, 2020.

2.10 Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test, suitable for small sample sizes (n < 30) and non-parametric distributions. A p-value < 0.05 was statistically significant. GraphPad Prism version 8.0.1 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, USA) was used for all statistical analyses. Both male and female calves were included in the study; however, due to the small number of animals per sex, no stratification by sex was applied during data analysis. No additional statistical analyses were performed; therefore, the conclusions drawn from data should be considered preliminary.

3 Results

3.1 Serological analysis

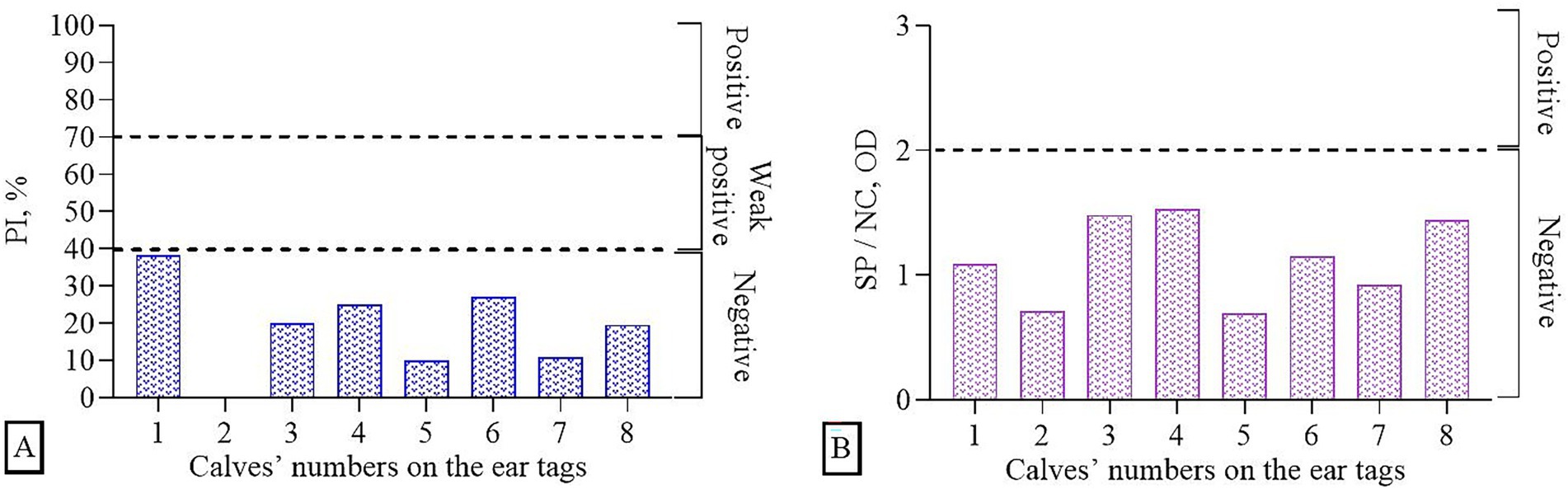

Before vaccination, serum samples were collected from 8 calves and tested for the presence of Abs to BoHV-1 and BVDV using commercial ELISA kits (Figure 2). It was found that all samples (n = 8) were negative for the IBR virus, i.e., they did not have specific Abs, since the mean of percentage inhibition (PI) values was ≤40%. In the studies of samples for the presence of Abs to the BVD virus, the absence of Abs was also revealed, since the ratio of the optical density of the sample (SP) / the optical density of the negative control (NC) was < 2. Thus, prior to immunization (day 0), no specific Abs against BoHV-1 and BVDV were detected, confirming the absence of pre-existing immunity.

Figure 2. Determination of immune background (presence of Abs in serum samples prior to the experiments) using ELISA: (A) BoHV-1, (B) BVDV.

The general health condition of the animals after vaccination remained satisfactory. No local reactions in the form of swelling at the injection sites or no general reactions in the form of fever, conjunctivitis, and serous nasal discharge were observed.

The most significant changes (p < 0.05) in Abs titers were noted on days 7 and 28 of the post-vaccination period (Figure 3). By day 7, VNA results showed a measurable increase in Ab titers was observed, indicating the formation of active immunity. The Ab titers were 2.74 log2 for BoHV-1 and 3.62 log2 for BVDV. A similar trend is observed on the 28th day, i.e., 7 days after revaccination, when the titer of Abs reaching 6.16 log2 for BoHV-1 and 6.24 log2t for BVDV. Protective Ab levels were maintained throughout the 9-month observation period, consistent with the thresholds reported by Frey (29). By the end of this period, some calves show a decrease in Ab titers, but the levels remained above or near the minimum protective level.

Figure 3. Dynamics of Abs titers to BoHV-1 and BVDV during 9 months post-vaccination period. * – p < 0.02; *** – p < 0.002; ns – p > 0.05. Dotted lines represent minimum protective levels (log2) of Abs for each virus (29).

3.2 Challenge infection of calves

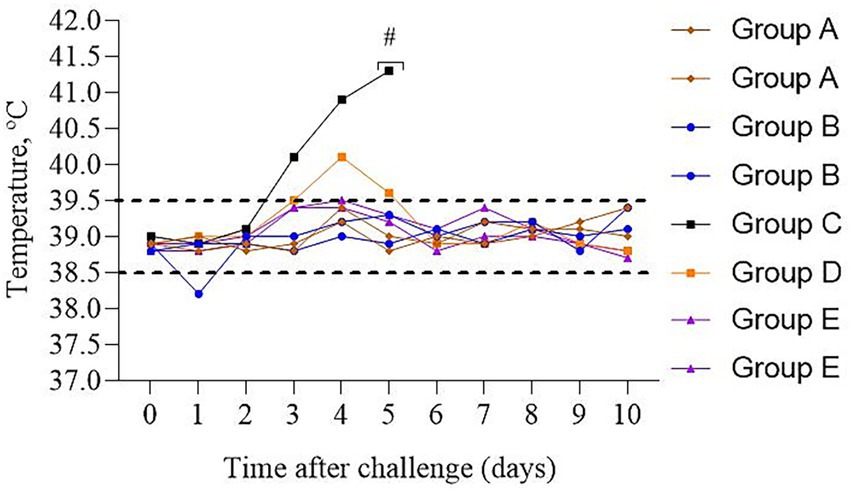

After a challenge during 10 days of observation, vaccinated cattle from Groups A&B (n = 4) remained clinically healthy, the temperature of body was within the physiological norm (Figure 4), no discharge from the mouth, nostrils or eyes was detected. Appetite remained normal.

Figure 4. Dynamics of the temperature changes in calves after experimental challenge. Group A – vaccinated, challenged with BoHV-1; Group B – vaccinated, challenged with BVDV; Group C – unvaccinated, challenged with BoHV-1; Group D – unvaccinated, challenged with BVDV; Group E – unvaccinated, unchallenged; # – calf euthanasia. Dotted line – normal physiological temperature range for calves (43).

In contrast, the unvaccinated calf from Group C had a cough and sneezing on the 2nd day, and inflammation of the mucous membrane of the eye, loss of appetite, and a body temperature of 40.1 °C were noted on the 3rd day. A fever of 41.3 °C and a severe cough were recorded on the 5th day. Due to the deterioration in the general physiological conditions of the calf, humane euthanasia was performed to alleviate suffering. A post-mortem assessment of the respiratory system was performed (Figure 5). Visible pathological changes were found in the lungs, round, dense nodular formations. The temperature of calf from Group D increased on the 4th day; however, no other clinical signs were found, as in Group C.

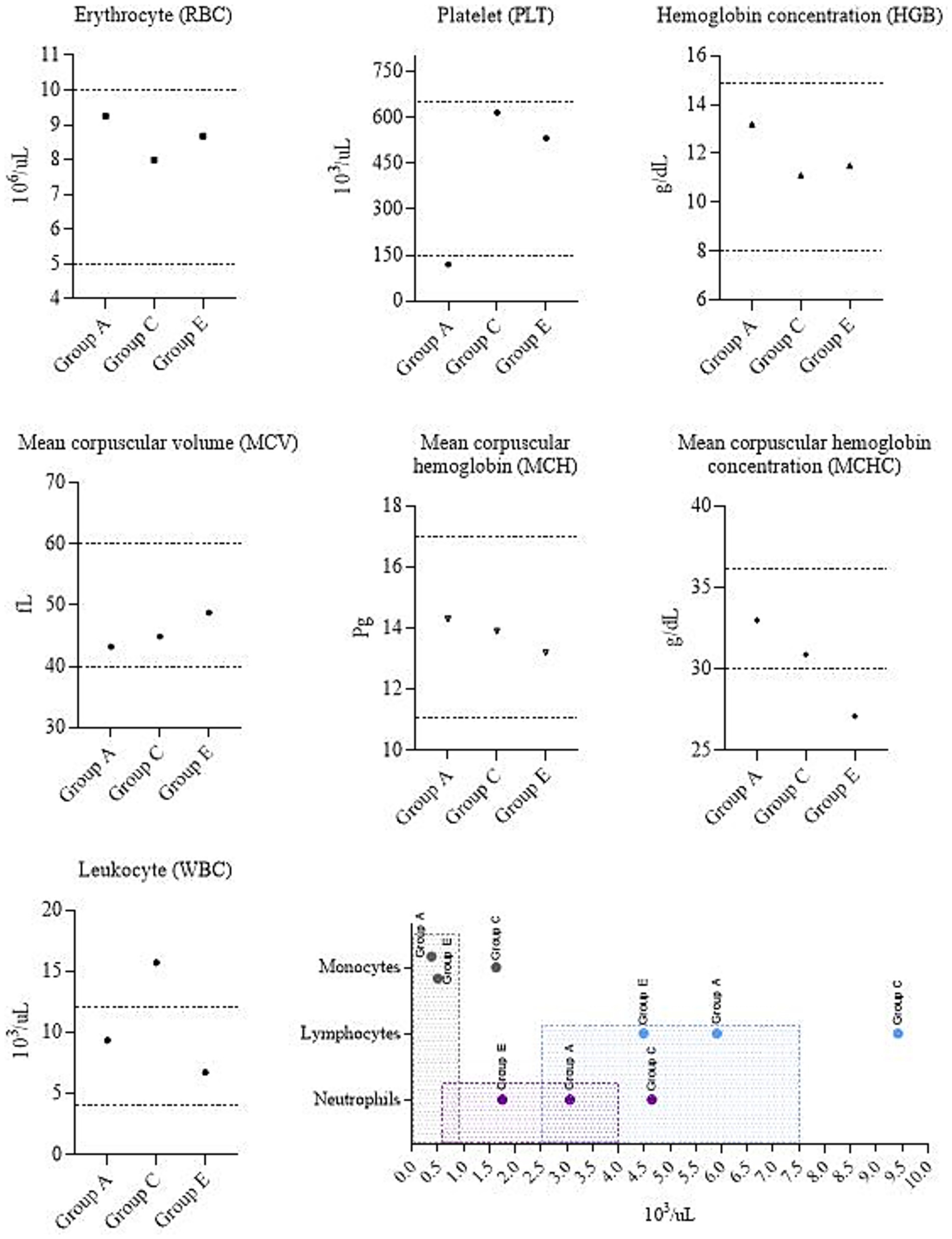

Due to the euthanasia of the Group C calf on day 5 post-infection, blood samples were collected from one animal each from Group C, A (as it was experimentally infected with BoHV-1), and Group E (control) for the purpose of hematological analysis and comparison with reference values (Figure 6). The vaccinated calf from Group A had a platelet (PLT) count level below the reference interval. A similar trend is observed in mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC) values in the control calf from Group E. In the euthanized calf (Group C), the leukocyte (WBC) values, including neutrophils, lymphocytes and monocytes, were elevated beyond normal limits.

Figure 6. Complete blood count. Group A – vaccinated, challenged with BoHV-1; Group C – unvaccinated, challenged with BoHV-1; Group E – unvaccinated, unchallenged. Dotted lines and shaded areas represent reference values (50).

4 Discussion

The prevalence of IBR and BVD among livestock is quite high (2–8). All breeds and ages are susceptible to IBR, but it is most often registered among adult livestock (5). Ortiz-González et al. (6) found that seroprevalence was highest in cattle aged >4 years. Clinical signs of BVD are recorded, including in newborn calves (32). Cattle infected with BVDV are highly prone to secondary bacterial infections (33). In our studies, only two viral pathogens – IBR and BVD – were investigated. Thus, evaluating the overall impact of secondary infections, including bacterial ones, was beyond the study’s scope. Moreover, during the experiments calves used were <2 years of age.

According to the statistics committee, as of February 1, 2025, approximately 4.35 million heads of cattle were registered in Kazakhstan (34). The largest number of cattle is registered in the East Kazakhstan, Almaty and Turkistan regions, and the lowest concentration is kept in the Mangghystau and Atyrau regions (20). Despite the use of imported vaccines, seropositive to IBR and BVD animals continue to be detected (21, 22), which indicates the persistent circulation of both viruses. Although no vaccine is considered completely effective (35), the duration of immunity may vary depending on vaccine the type (17). It should be noted that the use of attenuated vaccines for the prevention of viral diseases of cattle, while immunogenic, may poses a significant risk. In contrast, inactivated vaccines are safe and recommended for immunization of cattle, including pregnant cows (36, 37). A study by Peters et al. (38) assessed the duration of immunity provided by the Rispoval 4 vaccine against BoHV-1 and three additional bovine viruses, which was found to be more than 6 months.

We conducted studies to evaluate the duration of immunity after vaccination with the developed associated inactivated vaccine against IBR and BVD under the conditions of the southern region of Kazakhstan. The experiments involved 12 heads of cattle of the local mixed breed (Friesian-Holstein and Kazakh Whiteheaded) in the Zhambyl region from June 2024 to March 2025. Characteristic features of the climate of the Zhambyl region are significant aridity and continentality with minimal precipitation and temperature extremes: summers are very hot, and winters average −8, −12 °C (39, 40). According to Okunev (41), local crossbred cattle and the Kazakh Whiteheaded breeds a less susceptible to BVDV compared to imported purebred animals in North Kazakhstan.

Serology is often used to diagnose infectious diseases (42). ELISA confirmed that the selected calves had no previously acquired immunity to the IBR and BVD. That is, all 12 calves were not vaccinated before the experiments and were seronegative for both viruses. Also, animals did not show clinical signs of infectious diseases. VNA found that a specific immune response began to form as early as 7 days after primary vaccination. Abs titers reached a maximum between days 28 and 35, indicating full activation of humoral immunity. Abs to both viruses remained at a level exceeding the protective titer for at least 6 months. In some animals, Abs were detected up to 9 months.

Based on the results of the control infection of vaccinated and unvaccinated calves, the following can be identified. Normally in mammals, the reference value of temperature is in the range of 36.5–39.5 °C. During infections the set point is increased. According to Sjaastad et al. (43), the normal interval of temperature for a calf is 38.5–39.5 °C. Allan et al. (44) reported that animals affected by IBR developed severe clinical disease characterized by widespread respiratory tract lesions at autopsy. According to Evstifeev et al. (45), the main pathological changes in BVD are localized in the digestive tract; the oral cavity is hyperemic, covered with erosions and ulcers. Prevention of fever is considered a general parameter determining clinical protection of cattle from experimental BVD infection (46).

In challenge studies, no clinical signs of the diseases were detected in vaccinated calves of Groups A&B (n = 4) during a 10-day observation: body temperature stayed within the physiological norm, no changes in behavior; appetite and general condition were satisfactory. Previously, the safety of the vaccine was presented by Kondibaeva et al. (47). In contrast, in the unvaccinated calf from Group C, challenged with the BoHV-1, deterioration of the condition (including fever peaking at 41.3 °C, respiratory distress, and appetite loss) was observed for 3 days (from 3 to 5 days after infection). The incubation period for BoHV-1 typically ranges from 2 to 4 days (48). It is worth noting that we have chosen the following methods of anesthesia and euthanasia: xylazine, midazolam, and exsanguination. This approach was chosen due to the limited availability of ketamine and barbiturates in Kazakhstan. Due to this, we were unable to conduct a direct comparison between protocols. Importantly, based on our observations, no artifacts attributable to the used method were observed that could have affected the post-mortem or hematological outcomes. Necropsy revealed necrotic changes and nodules in the lungs. Similar data were obtained in cattle infected with IBR; however, mycoplasma co-infection has also been detected (49). In an unvaccinated calf from Group D, challenged with the BVDV, an increase of temperature to 40.1 °C was noted on the 4th day; but other clinical symptoms of infection were not detected. Such differences in experimentally infected animals may be due to the fact that BoHV-1 is primarily associated with acute respiratory disease (44), whereas BVDV often causes predominantly gastrointestinal effects (45). These factors likely contributed to a milder clinical outcome in the Group D calf.

The hematological profile reflects the state of health and allows assessing the presence of inflammation. Therefore, we additionally performed a hematological analysis. Results were compared with the established reference values for calves (50). Based on these parameters, Barsukova et al. (51) also identified complete blood count values that fall within the specified range. Erythrocytes (RBC) are responsible for gas exchange, transporting oxygen and carbon dioxide. A complete assessment of RBC includes the mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC). In our study, this parameter was reduced in the calf of Group E. A decrease of MCHC possibly suggesting iron deficiency or anemia (52). Platelets (PLT) play an important role in hemostasis. Low PLT count (as in calf from Group A) can be caused by a number of reasons (52). According to Roland et al. (53), examples of infectious diseases causing thrombocytopenia can be salmonellosis, leptospirosis, and babesiosis. Hence, it cannot be concluded definitively that BoHV-1 alone caused the platelet decrease. Leukocytes (WBC) play an important role in immune protection. Increased WBC in the calf from Group C can indicate stress, excitement, or infectious processes. It is worth excluding bovine leukocyte adhesion deficiency (BLAD), since it is diagnosed when the neutrophil count is more than 40,000 cells/μl, while the changes in the calf of Group C were less than 10,000 cells/μl, which is significantly less for BLAD but exceeds the reference values. Monocytosis can also be caused by necrosis (53). Collectively, clinical signs and pathological changes may diagnosis of IBR disease in this animal.

This study has several limitations:

1. Although we followed ARRIVE 2.0 guidance (54), but changes were made in item 2b, which requires justification of sample size. The power analysis was performed using G*Power 3.1.9.7 (Heinrich Heine Universität Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany). Test family: F test, ANOVA fixed effects, omnibus with large effect size (f = 1.0), α = 0.05, power = 0.8, for ANOVA of 5 groups. The required sample size was estimated as n = 20. However, due to the fact that the developed vaccine is at the experimental stage, in our research work on vaccination and evaluation of the duration of immunity of cattle, the number of test animals was limited and amounted to 12 heads.

2. In the present study, both male and female calves were included. However, due to the small sample size, animals were not stratified by sex during data analysis. This limitation should be considered when interpreting the vaccination outcomes, as sex-related differences in immune response cannot be ruled out. Given the restricted sample size, no additional inferential statistical tests were feasible, so findings should be interpreted with caution and considered preliminary until validated in large-scale studies.

3. Hematological evaluation was performed only once on day 5 post-infection, and was not part of the original study design. Although this provided useful comparative data on IBR, calves from the B&D groups that were challenged with BVDV were not included in the hematological analysis; that limits conclusions regarding BVD-associated blood parameters. Besides, continuous hematological monitoring would have offered a deeper understanding of disease dynamics. Future studies with larger animal groups will include hematological measurements at multiple time points.

4. Even if calves were suspected of having possible anemia or other infections, no further diagnostic investigations (e.g., viral isolation, PCR, or bacteriological cultures) were performed to determine the causes of the abnormal hematological findings observed in the Group A&E calves. Likewise, although post-mortem examination of the Group C calf revealed round, dense nodular formations in the lung, no specific testing for mycoplasma or other bacterial co-infections was conducted. This represents a limitation of the study. Future work will incorporate additional laboratory diagnostics, as the possibility of concurrent infections cannot be excluded.

Despite these limitations, the results suggest that the developed vaccine provides effective protection against BoHV-1 and BVDV.

5 Conclusion

Despite the limited number of animals used in this study, valuable data on the safety and immunogenicity of the developed vaccine were obtained. The dynamics of Abs allow us to make preliminary conclusions about the duration of post-vaccination immunity, which appears to last for at least 6 months. However, due to the small sample size, subsequent confirmation on an expanded sample is needed to validate these findings and develop statistically robust conclusions. In future work, we plan to evaluate the effectiveness of the vaccine under field conditions.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by Research Institute for Biological Safety Problems (RIBSP) Ethics Committee (Approval No. 1-14-07-2023). The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

YB: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. ZS: Data curation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft. RA: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Resources. AKy: Investigation, Validation, Writing – original draft. AU: Investigation, Validation, Writing – original draft. ZK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. ZA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. ST: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. DT: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. DM: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. KS: Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft. KJ: Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft. KZ: Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft. KB: Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft. AKe: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. AR: Project administration, Writing – review & editing. YA: Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. AKu: Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by the Committee of Science of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan, No. BR218004/0223.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the staff of the RIBSP: Nakhanov AK, Head of the Laboratory for Cell Biotechnology. Kaldybayev TR, Head of the Department of Experimental Animals. Kaukaeva KB, Batyrkhanova K, Alimbayev EZh, and Abdimalikova G, laboratory assistants of the Laboratory for Technologies of Cultivation of Microorganisms.

Conflict of interest

YB, ZS, RA, AKy, AU, ZK, ZA, ST, DT, DM, KS, KJ, KZ, KB, AKe, AR, and YA were employed by QazBioPharm.

The remaining author declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Chat GPT (GPT-4.5) was used for the accurate translation of the manuscript from the native language into English.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Hay, KE, Ambrose, RCK, Morton, JM, Horwood, PF, Gravel, JL, Waldron, S, et al. Effects of exposure to bovine viral diarrhoea virus 1 on risk of bovine respiratory disease in Australian feedlot cattle. Prev Vet Med. (2016) 126:159–69. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2016.01.025

2. Barrett, D, Parr, M, Fagan, J, Johnson, A, Tratalos, J, Lively, F, et al. Prevalence of bovine viral diarrhoea virus (BVDV), bovine herpes virus 1 (BHV 1), leptospirosis and neosporosis, and associated risk factors in 161 Irish beef herds. BMC Vet Res. (2018) 14:8. doi: 10.1186/s12917-017-1324-9

3. Fernandes, LG, Pituco, EM, de Campos Nogueira Romaldini, AH, Stefano, ED, Clementino, IJ, Maia, ARA, et al. Spatial analysis for bovine viral diarrhea virus and bovine herpesvirus type 1 infections in the state of Paraíba, northeastern Brazil. BMC Vet Res. (2018) 14:102. doi: 10.1186/s12917-018-1412-5

4. Hou, P, Zhao, G, Wang, H, and He, H. Prevalence of bovine viral diarrhea virus in dairy cattle herds in eastern China. Trop Anim Health Prod. (2019) 51:791–8. doi: 10.1007/s11250-018-1751-z

5. Kipyego, ES, Gitau, G, Vanleeuwen, J, Kimeli, P, Abuom, TO, Gakuya, D, et al. Sero-prevalence and risk factors of infectious bovine rhinotracheitis virus (type 1) in Meru County, Kenya. Prev Vet Med. (2020) 175:104863. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2019.104863

6. Ortiz-González, AD, Buitrago, HAL, Bulla-Castañeda, DM, Lancheros-Buitrago, DJ, Garcia-Corredor, DJ, Díaz-Anaya, AM, et al. Seroprevalence and risk factors associated with bovine herpesvirus 1 in dairy herds of Colombia. Vet World. (2022) 15:1550–6. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2022.1550-1556

7. Hashemi, М, Bakhshesh, М, and Manavian, М. Bovine viral diarrhea virus and bovine herpes virus-1 in dairy cattle herds in Fars Province, southern Iran: seroprevalence and evaluation of risk factors. Arch Razi Inst. (2022) 77:1621–9. doi: 10.22092/ARI.2022.356904.1941

8. Nautiyal, S, Nandi, S, Sharma, K, Gairola, V, Balaji, KGS, Biswas, SK, et al. Development and evaluation of recombinant gD protein based ELISA for sero-surveillance of BoHV-1 in India. Biologicals. (2023) 84:101720. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2023.101720

9. Segura-Correa, JC, Zapata-Campos, CC, Jasso-Obregón, JO, Martinez-Burnes, J, and López-Zavala, R. Seroprevalence and risk factors associated with bovine herpesvirus 1 and bovine viral diarrhea virus in north-eastern Mexico. Open Vet J. (2016) 6:143–9. doi: 10.4314/ovj.v6i2.12

10. Quintana, ME, Cardoso, NP, Pereyra, R, Barone, LJ, Barrionuevo, FM, Mansilla, FC, et al. Interferon lambda protects cattle against bovine viral diarrhea virus infection. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. (2020) 230:110145. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2020.110145

11. Tikoo, SK, Campos, M, and Babiuk, LA. Bovine herpesvirus 1 (BHV-1): biology, pathogenesis, and control. Adv in Virus Res. (1995) 45:191–223. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(08)60061-5

12. Ridpath, JF. Bovine viral diarrhea virus: global status. Vet Clin N Am Food Anim Pract. (2010) 26:105–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cvfa.2009.10.007

13. Newcomer, BW. 75 years of bovine viral diarrhea virus: current status and future applications of the use of directed antivirals. Antivir Res. (2021) 196:105205. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2021.105205

14. Falkenberg, SM, Dassanayake, RP, Crawford, L, Sarlo Davila, K, and Boggiatto, P. Response to bovine viral diarrhea virus in heifers vaccinated with a combination of multivalent modified live and inactivated viral vaccines. Viruses. (2023) 15:703. doi: 10.3390/v15030703

15. Hudson, RE, Tomczak, DJ, Kaufman, EL, Adams, AM, Carroll, JA, and Broadway, PR. Immune responses and performance are influenced by respiratory vaccine antigen type and stress in beef calves. Animals. (2020) 10:1119. doi: 10.3390/ani10071119

16. Reddout, C, Chase, CCL, Beck, P, and Salak-Johnson, JL. Dam age differentially affects immune response of her calf to bovine respiratory disease vaccination. Agriculture. (2024) 14:68. doi: 10.3390/agriculture14010068

17. Richeson, JT, and Falkner, TR. Bovine respiratory disease vaccination: what is the effect of timing? Vet Clin N Am Food Anim Pract. (2020) 36:473–85. doi: 10.1016/j.cvfa.2020.03.013

18. Newcomer, BW, and Givens, D. Diagnosis and control of viral diseases of reproductive importance: infectious bovine rhinotracheitis and bovine viral diarrhea. Vet Clin N Am Food Anim Pract. (2016) 32:425–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cvfa.2016.01.011

19. Chase, CCL, Fulton, RW, O’tole, D, Gillette, B, Daly, FR, Perry, G, et al. Bovine herpesvirus 1 modified live virus vaccines for cattle reproduction: balancing protection with undesired effects. Vet Microbiol. (2017) 206:69–77. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2017.03.016

20. Turkeyev, MK, Karabassova, AS, Nissanova, RK, Nurpeisova, AS, Kirpichenko, VV, Bashenova, EE, et al. Serological diagnosis of infectious rhinotracheitis cattle (irt cattle) in the regions of Kazakhstan. Gylym Zane Bilim. (2025) 1:3–14. doi: 10.52578/2305-9397-2025-2-1-3-13%20

21. Omarova, G, Baikadamiva, G, Assauova, Z, and Akanova, Z. Seroprevalence of infectious bovine rhinotracheitis in Kazakhstan: propagation dynamics in 2021–2022. 3i Intellect Idea Innov. (2024) 4:16–23. doi: 10.52269/22266070_2024_4_16

22. Bashenova, E, Nissanova, R, Zharmukhametova, A, Akshalova, P, Serikov, M, Mamanova, S, et al. Selection of strong positive serum samples from cattle infected with bovine viral diarrhea. Euras J Appl Biotech. (2024) 3:66–72. doi: 10.11134/btp.3.2024.7

23. Kerembekova, UZ, Mamadaliev, SM, Koshemetov, ZK, Pasechnikov, LN, and Rusanova, AM, (2008). Strain “P-93” of infectious bovine rhinotracheitis virus used to obtain a cultured live virus vaccine. Available online at: https://kz.patents.su/3-12203-shtamm-r-93-virusa-infekcionnogo-rinotraheita-krupnogo-rogatogo-skota-ispolzuemyjj-dlya-polucheniya-kulturalnojj-zhivojj-virusvakciny.html [Accessed July 17, 2025]

24. National Center for Biotechnology Information. (1998). Bovine viral diarrhea virus strain Oregon C24V, complete genome. Available online at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/AF091605.1?report=genbank [Accessed July 17, 2025]

25. Bulatov, Y, Kurmasheva, A, Amanova, Z, Abitaev, R, Sametova, Z, Kyrgyzbayeva, A, et al. The influence of the associated inactivated vaccine against infectious rhinotracheitis and bovine viral diarrhea on the formation and duration of colostral immunity in kazakh whiteheaded calves. Vaccine. (2025) 13:408. doi: 10.3390/vaccines13040408

26. American Type Culture Collection. (2025). Bovine herpesvirus 1. Available online at: https://www.atcc.org/products/vr-864 [Accessed July 17, 2025]

27. American Type Culture Collection. (2025). MDBK (NBL-1). Available online at: https://www.atcc.org/products/ccl-22 [Accessed July 17, 2025]

28. Raizman, EA, Pogranichniy, R, Negron, M, Schnur, M, and Tobar-Lopez, DE. Seroprevalence of infectious bovine rhinotracheitis and bovine viral diarrhea virus type 1 and type 2 in non-vaccinated cattle herds in the Pacific region of Central Costa Rica. Trop Anim Health Prod. (2010) 43:773–8. doi: 10.1007/s11250-010-9762-4

29. Frey, ML. One year antibody responses of four inactivated infectious bovine rhinotracheitis-bovine viral diarrhea vaccines. Bov Pract. (1989) 24:18–24. doi: 10.21423/bovine-vol0no24p18-21

30. GraphPad. (2025). Randomly assign subjects to treatment groups. Available online at: https://www.graphpad.com/quickcalcs/randomize1/ [Accessed July 17, 2025]

31. Diatron. (2025). Abacus Vet5. Available online at: https://www.diatron.com/hematology-analyzersabacus-vet5-5-part-diff-veterinary-analyzer [Accessed July 17, 2025]

32. Mishchenko, AV, Mishchenko, VA, Gulyukin, MI, Oganesyan, AS, Alexeyenkova, SV, Zaberezhny, AD, et al. Persistent form of bovine viral diarrhea. Probl Virol. (2023) 68:465–78. doi: 10.36233/0507-4088-184

33. Kim, UH, Kang, SS, Jang, SS, Kim, SW, Chung, KY, Kang, DH, et al. Bovine viral diarrhea virus antibody level variation in newborn calves after vaccination of late-gestational cows. Vet Sci. (2023) 10:562. doi: 10.3390/vetsci10090562

34. Tulepov, BS, Nissanova, RK, Akshalova, PB, Bashenova, EE, Mamanova, SB, Murzabaev, KE, et al. Viral diarrhea of cattle in Kazakhstan: epizootic situation and control methods 2024. Gylym zane bilim. (2025) 1:34–44. doi: 10.52578/2305-9397-2025-2-1-34-44%20

35. Newcomer, BW, Chamorro, MF, and Walz, PH. Vaccination of cattle against bovine viral diarrhea virus. Vet Microbiol. (2017) 206:78–83. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2017.04.003

36. Yeşilbağ, K, Alpay, G, and Becher, R. Variability and global distribution of subgenotypes of bovine viral diarrhea virus. Viruses. (2017) 9:128. doi: 10.3390/v9060128

37. Kelling, CL. Evolution of bovine viral diarrhea virus vaccines. Vet Clin N Am Food Anim Pract. (2004) 20:115–29. doi: 10.1016/j.cvfa.2003.11.001

38. Peters, AR, Thevasagayam, SJ, Wiseman, A, and Salt, JS. Duration of immunity of a quadrivalent vaccine against respiratory diseases caused by BHV-1, PI3V, BVDV, and BRSV in experimentally infected calves. Prev Vet Med. (2004) 66:63–77. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2004.08.001

39. Salnikov, V, Talanov, Y, Polyakova, S, Assylbekova, A, Kauazov, A, Bultekov, N, et al. An assessment of the present trends in temperature and precipitation extremes in Kazakhstan. Climate. (2023) 11:33. doi: 10.3390/cli11020033

40. Kazhydromet. (2025). Climate of Kazakhstan. Available online at: https://www.kazhydromet.kz/en/ [Accessed July 2, 2025]

41. Okunev, AM. The features of the epizootic process of bovine viral diarrhea in the district of the North-Kazakhstan region. Vestn Alt Gos Agrar Univ. (2020) 1:103–11.

42. Woolums, AR. Serology in bovine infectious disease diagnosis. Vet Clin N Am Food Anim Pract. (2023) 39:141–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cvfa.2022.10.007

43. Sjaastad, OV, Sand, O, and Hove, K. Physiology of domestic animals. Olso: Norway Scandinavian Vet Press (2010).

44. Allan, EM, Pirie, HM, Msolla, PM, Selman, IE, and Wiseman, A. The pathological features of severe cases of infectious bovine rhinotracheitis. Vet Rec. (1980) 107:441–5. doi: 10.1136/vr.107.19.441

45. Evstifeev, VV, Konnov, MN, Khusainov, FM, Khusainova, GI, and Akbashev, IR. Bovine viral diarrhea – mucosal disease. Veterinariia. (2019) 10:19–25.

46. Palomares, RA, Givens, MD, Wright, JC, Walz, PH, and Brock, KV. Evaluation of the onset of protection induced by a modified-live virus vaccine in calves challenge inoculated with type 1b bovine viral diarrhea virus. Am J Vet Res. (2012) 73:567–74. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.73.4.567

47. Kondibaeva, ZB, Kurmasheva, AK, Bulatov, EA, Abitaev, RT, Sametova, ZZ, and Ussembay, AK. Safety assessment of inactivated vaccine for infectious rhinotracheitis and diarrhea in bovine in laboratory animals and calves. Gylym Zane Bilim. (2025) 1:159–67. doi: 10.52578/2305-9397-2025-2-1-159-167

48. Bulatov, EA, and Kurmasheva, AK. Infectious bovine rhinotracheitis: a brief overview. Biosaf Biotechnol. (2024) 18:19–43. doi: 10.58318/2957-5702-2024-18-19-43

49. Kudryashov, AA, Balabanova, VI, Belyaeva, EV, and Pudovkin, DN. Pathologic diagnosis of infectious resppiratory diseases of cattle on farms. Aktual Probl Vet Biol. (2017) 33:59–65.

50. Kessell, KA. Bovine haematology and biochemistry In: PD Cockcroft, editor. Bovine medicine. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd (2015). 146–60.

51. Barsukova, MA, Narozhnykh, KN, Sebezhko, OI, and Ivanova, OA. Analysis of age-related differences in hematological traits of Hereford cattle breed. Vestn Ross S-kh Nauki. (2025) 2:84–90. doi: 10.31857/S2500208225020173

52. Jones, ML, and Allison, RW. Evaluation of the ruminant complete blood cell count. Vet Clin N Am Food Anim Pract. (2007) 23:377–402. doi: 10.1016/j.cvfa.2007.07.002

53. Roland, L, Drillich, M, and Iwersen, M. Hematology as a diagnostic tool in bovine medicine. J Vet Diagn Invest. (2014) 26:592–8. doi: 10.1177/1040638714546490

Keywords: infectious bovine rhinotracheitis, bovine viral diarrhea, vaccine, prevention, calves, immunity

Citation: Bulatov Y, Sametova Z, Abitayev R, Kyrgyzbayeva A, Ussembay A, Kondibaeva Z, Amanova Z, Turyskeldy S, Toktyrova D, Mazbayeva D, Shorayeva K, Jekebekov K, Zhugunissov K, Barakbayev K, Kerimbayev A, Rsaliyev A, Abduraimov Y and Kurmasheva A (2025) Duration of immunity against infectious rhinotracheitis and bovine viral diarrhea after vaccination in calves in southern region of Kazakhstan. Front. Vet. Sci. 12:1681624. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2025.1681624

Edited by:

Jerry William Simecka, University of North Texas Health Science Center, United StatesReviewed by:

Nattawooti Sthitmatee, Chiang Mai University, ThailandSalam Abd Esmaeel, University of Mosul, Iraq

Copyright © 2025 Bulatov, Sametova, Abitayev, Kyrgyzbayeva, Ussembay, Kondibaeva, Amanova, Turyskeldy, Toktyrova, Mazbayeva, Shorayeva, Jekebekov, Zhugunissov, Barakbayev, Kerimbayev, Rsaliyev, Abduraimov and Kurmasheva. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yerbol Bulatov, eWUuYnVsYXRvdkBiaW9zYWZldHkua3o=; Alina Kurmasheva, YS5rdXJtYXNoZXZhQGJpb3NhZmV0eS5reg==

Yerbol Bulatov

Yerbol Bulatov Zhanna Sametova1

Zhanna Sametova1 Zhanat Amanova

Zhanat Amanova Dariya Toktyrova

Dariya Toktyrova Kuandyk Zhugunissov

Kuandyk Zhugunissov Aslan Kerimbayev

Aslan Kerimbayev Alina Kurmasheva

Alina Kurmasheva