- 1Agricultural Animal Diseases and Veterinary Public Health Key Laboratory of Sichuan Province, College of Veterinary Medicine, Sichuan Agricultural University, Chengdu, China

- 2Institute of Animal Husbandry Sciences of Ganzi Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Kangding, Sichuan, China

Streptococcus agalactiae (S. agalactiae or GBS) is the main pathogen causing subclinical mastitis in dairy cows. This infection has seriously affected the development of the global dairy industry and thus requires urgent mitigation strategies to reduce its spread. Thus endophytes which are potential sources of novel bioactive antibacterial compounds can effectively be harnessed to address the issues of bacterial infections and resistance in animal production. The aim of this study was to investigate the in vitro antibacterial activity and potential mechanism of Bacillus velezensis Ea73 (an endophyte from Ageratina adenophora plant) cell free supernatant (CFS) against S. agalactiae isolated from cows. The antibacterial activity of Ea73 CFS against S. agalactiae was analyzed by plate and double dilution methods. Biofilm staining and transmission electron microscopy were used to explore the effects of Ea73 CFS on biofilm formation, structure and extracellular polymeric substances in the S. agalactiae. In addition, network pharmacology was used to further explore the relevant mechanisms of Ea73 CFS in treating diseases mediated by S. agalactiae. The results showed that the inhibition zone diameter of Ea73 CFS against S. agalactiae was 12 mm, and the minimum biofilm inhibition concentration was 10 mg/mL. After treatment with Ea73 CFS, the biofilm formation was significantly inhibited, the structure of the generated biofilm was disrupted, and the metabolic activity of bacterial cells was significantly reduced. The results from this study indicated that EA73 CFS significantly inhibits S. agalactiae activity via biofilm eradication and hence can serve as a promising antibacterial reagent.

1 Introduction

Streptococcus agalactiae is one of the common and main pathogenic bacteria that cause cow mastitis. Mastitis is the most common disease of dairy cattle worldwide, causing economic losses due to reduced yield and poor quality of milk (1). Over the years, several researchers have reported the prevalence of mastitis, both clinical and subclinical, is as high as 81.1% with Staphylococcus and Streptococcus being the dominant pathogenic species (1). The virulence factors of S. agalactiae have the function of adhesion and invasion of body cells, causing the bacteria to form a biofilm on the surface of cow breasts, thereby interfering with the normal immune function of the body, causing subclinical bovine mastitis and recurrent infections (2, 3, 52). In addition, S. agalactiae also causes neonatal pneumonia, septic shock syndrome, high mortality meningitis, and various diseases in other animals (4). Therefore, the development of effective mitigation strategies for controlling and preventing S. agalactiae mastitis is of great significance for the economic efficiency and public health safety of breeding farms.

Antibiotic treatment has been an effective treatment for bovine mastitis, especially in the treatment of acute, latent, and multiple mastitis, as well as in the quality control of dairy products (5). However, due to the arbitrary use of antibiotics, the number of drug-resistant strains has gradually increased, and bacteria have become increasingly resistant to antibiotics. This poses significant challenges to the treatment of mastitis in dairy cows. Therefore, there is an urgent need to identify new antimicrobial agents with high antimicrobial activity and low drug resistance.

Ageratina adenophora (A. adenophora) is an invasive poisonous weed widely distributed across the world. This plant has been reported to cause great harm to my global agricultural production and development (6–8). However, in recent years the research focus of this plant has been shifted from toxicity study to biological utilization of the plants endophytes resources for the production of new bioactive compounds (9–11). Researchers have found that A. adenophora extract has insecticidal, antibacterial, antitumor, antiviral, and antioxidant properties, which are related to its endophytic fungi (12–15). Our previous studies similarly reported antibacterial activities of extracts from both bacteria and fungi endophytes that were isolated from A. adenophora (8, 10). However, these studies were mainly focused on Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli; thus, there is the need to investigate the antibacterial activity and mechanisms associated with these extracts in other strains of pathogenic bacteria to validate its effects.

Bacillus velezensis EA73, an endophyte from Ageratina adenophora, has shown excellent antibacterial activity against S. aureus and E. coli (9, 16). However, its activity on other strains of pathogenic bacteria such as S. agalactiae as well as the molecular mechanism involved in the endophytic bacteria’s antibacterial properties has not been fully elucidated yet. Therefore, in this study, we focused on investigating the antibacterial activity and molecular mechanisms of B. velezensis EA73 CFS against S. agalactiae using in vitro methods and network pharmacology. This study will provide information on how B. velezensis EA73 CFS exhibits its antimicrobial activity to help us develop novel drugs for the treatment of mastitis.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Strain and growth conditions of Bacillus velezensis EA73 and Streptococcus agalactiae (GBS)

Bacillus velezensis EA73 (GenBank no. MZ540895) was obtained from Hu Lab, Sichuan Agricultural University, and after routine passaging culture, it was preserved at −80 °C in a Luria–Bertani medium with 20% glycerol (16). Streptococcus agalactiae (standard strain MK330595) was presented as a lyophilized powder from Zuo Lab, Sichuan Agricultural University; activated and preserved in BHI broth medium with sterile 60% glycerol at a ratio of 1:1 at −80 °C.

2.2 Preparation of EA73 CFS

The Ea73 activation solution was inoculated into a fermentation medium (yeast extract: 6.55 g/L; peptone: 6.61 g/L; NaCl: 20.00 g/L), and fermentation was carried out in a 180 r/min shaker according to fermentation parameters (initial pH: 7.95; temperature: 27.97 °C; time: 51.04 h) (16). The fermentation broth was extracted several times with ethyl acetate at a ratio of 3:1, and the organic phase was collected and concentrated with a rotary evaporator at 45 °C under reduced pressure to obtain the concentrate, which was decontaminated with a 0.22 μm microporous membrane filter and then freeze-dried to obtain the dry substance (Freeze-dryer FDR2110, Rikaku eyela, Tokyo, Japan). The dry substance was stored at −20 °C until use (16).

2.3 Antibacterial activity assay

The bacterial suspension was centrifuged at 4000 r/min for 10 min, the bacterial precipitate was collected, and the suspension was suspended in sterile saline to 106 CFU/mL, which was the pathogen suspension. Using the punching method (9), under sterile conditions, 100 μL of the bacterial suspension was aspirated and spread on blood and ordinary agar plates. After drying, it was punched with a 9 mm diameter puncher. 60 μL of Ea73 CFS was added to each well. Sterile normal saline was used as a blank control. After the culture medium was placed in a 37 °C incubator for 24 h, the diameter of the inhibition zone was measured with a vernier caliper using the cross-cross method to evaluate its antibacterial activity. The antibacterial experiment was repeated three times and the average value was taken.

2.4 Minimum inhibitory concentration determination

The antibacterial assay was performed using a 96-well plate according to the micro-dilution method. The antibacterial assay consisted of three parallel experimental groups, one blank control group, a positive control, and a negative control. 100 μL of BHI culture medium was added to all microwells in advance. Experimental group: 174.4 μL of Ea73 CFS at a concentration of 0.02 g/mL (i.e., a 200 μL system) was added to the first column of microwells. After thorough mixing with 25.6 μL of pre-added S. agalactiae bacterial solution, 100 μL of the mixture was pipetted into the second column. After thorough mixing, 100 μL of the mixture was pipetted into the third column. The mixture was serially diluted to the last column. For the blank control, 100 μL each of BHI broth and normal saline was added. For the negative control, 100 μL each of Ea73 CFS at a concentration of 0.02 g/mL and BHI broth was added. For the positive control, 100 μL each of bacterial solution and BHI broth was added. Finally, the microplate was incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. After incubation, the microplate was placed in a microplate reader and the absorbance was read at 560 nm. The MIC of Ea73 against S. agalactiae was determined based on the absorbance.

2.5 Determination of MBIC

The MBIC of EA73 CFS against S. agalactiae was assessed using crystal violet staining and CFU counting (17). A total of 200 μL of sterile TBS and a 1% (v/v) S. agalactiae bacterial suspension (108 CFU/mL) was added to 96-well plates. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 48 h to form a biofilm, and the supernatant was discarded. The plates were subsequently washed three times with PBS. A gradient concentration of EA73 CFS (0.16–10.24 × 10–3 g/mL) was added, and the mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The culture medium was discarded, and the planktonic bacteria were rinsed with sterile PBS and discarded. Then, sterile PBS was added again, and the biofilm was suspended by repeated blowing. The suspension was diluted and spread evenly on a BHI plate for CFU counting. The results were observed after 24 h of incubation at 37 °C. The experiment was repeated three times, and the average value was taken.

After incubation of the biofilm and CFS treatment, the planktonic bacteria were rinsed with sterile PBS, and the biofilm was stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 15 min. After, it was rinsed with sterile PBS and dissolved with 95% ethanol. The OD value at 595 nm of the solution in the culture wells was determined via a multifunctional fluorescence chemiluminescence immunometer.

2.6 Antibiotic sensitivity test

Antibiotic sensitivity patterns were evaluated using the method from Okyere et al. (53). 100 μL of S. agalactiae suspension was taken with a pipette and placed in a blood plate. The bacterial solution was evenly spread on the plate with a sterilized glass bead. The plate was covered and left to stand for about 15 min until the surface of the plate was slightly dry. Sterilized tweezers were used to stick the antibiotic disks on the surface of the culture medium by gentle pressing. Three antibiotic disks were stuck on each plate. Finally, the plate was placed in a 37 °C constant temperature biochemical incubator for 24 h. The diameter of the inhibition zone was measured with a vernier caliper, and the sensitivity of the strain to antibiotics was determined. The selected antimicrobial drugs were: penicillin, gentamicin, vancomycin, ofloxacin, ampicillin, novobiocin, chloramphenicol, cefoperazone, enrofloxacin, clindamycin, and erythromycin. Disks immersed in sterile water were used as the negative controls.

2.7 S. agalactiae biofilm-forming ability assay

100 μL of sterile BHI and a 1% (v/v) S. agalactiae bacterial suspension (108 CFU/mL, the bacterial suspension was diluted to an OD600 equal to 0.9) were added to 96-well plates and incubated at 37 °C for 12, 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 h. After incubation, the culture medium was discarded and the plates were gently washed with PBS to remove floating bacteria. The plates were then fixed with 100 μL of methanol solution at room temperature for 15 min, after which the methanol was discarded and the plates were air-dried in a biosafety cabinet. The plates were stained with 100 μL of 0.1% crystal violet solution at room temperature for 5 min. Excess dye was removed with sterile PBS and air-dried on an ultraclean bench. 100 μL of 33% glacial acetic acid was added to the plate and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. The OD values of the solutions in the wells were measured at a wavelength of 570 nm using a microplate reader. Wells with no bacteria were used as a blank group. The experiment was repeated three times, and the average of the three measurements was used as the final result.

2.8 Laser confocal microscopy observation

5 mL of sterile BHI, 1% (v/v) S. agalactiae bacterial suspension (108 CFU/mL) and a sterile coverslip (2 cm × 2 cm) were added to a 6-well plate. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h to form a biofilm. The culture medium was discarded and washed with sterile PBS. Then, Ea73 CFS with a concentration of 1/2 MBIC was added. The wells with the same amount of PBS were used as the control group. After incubation at 37 °C for 4 h, the coverslips were removed and DAPI (10 μg/mL) was added for staining in the dark for 20 min. The biofilm structure was then observed using a confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM) (18).

2.9 Effect of Ea73 CFS on bacterial metabolism in S. agalactiae biofilms

The S. agalactiae biofilms were cultured on sterile coverslips, as described previously, and then the culture medium was discarded and washed with sterile PBS. Ea73 CFS with concentrations of 1/2 MBIC, MBIC, and 2 MBIC were added to treat the biofilm for 24 h. The control group was treated without Ea73 CFS. The glass slide was removed and placed in sterile water for 15 min to separate the biofilm bacteria from the glass slide. 10% resazurin solution was added to the bacterial suspension, and the suspension was shaken at 37 °C in the dark for 2 h. The supernatant was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The absorbance at 560 nm excitation wavelength and 593 nm emission wavelength was measured using a microplate reader.

2.10 Effects on extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) of S. agalactiae biofilms

2.10.1 Enzymatic hydrolysis assay

Biofilms were cultured in 96-well plates as mentioned above and after incubation, the culture medium was discarded. Four groups of samples were set up: one blank control group and the remaining three experimental groups, with 10 replicate wells per group. The blank control group was treated with sterile PBS, while the experimental groups were treated with sodium periodate (10 μM), DNase I (2 mg/mL), and proteinase K (100 μg/mL), respectively. The 96-well plates were incubated at 37 °C for 2 h and stained with crystal violet. Finally, after decolorization with ethanol for 30 min, the OD values at 595 nm were measured using a microplate reader.

2.10.2 Effects of Ea73 CFS on extracellular proteins

Culturing of the biofilms was performed according to the methods described previously, and EA73 CFS (1/2 MBIC, MBIC, or 2 MBIC) was added while the bacteria were being cultured. After the incubation was complete, the culture media was discarded, and the mixture was rinsed with PBS to remove free bacteria from the surface. The cleaned coverslips were sonicated in PBS for 1 h, after which the bacterial suspension was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min as an EPS sample for backup. Extracellular proteins were measured by the Coomassie Brilliant Blue method using a protein content assay kit (Biosharp Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). The OD595nm value was measured using a UV spectrophotometer.

2.10.3 Statistical analysis

Experiments were performed in triplicate. Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). The results are shown as the mean ± standard error. Significant differences in the mean values were estimated by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Student’s t-test.

2.11 Ea73 CFS network pharmacology analysis

2.11.1 Target prediction and collection of Ea73 CFS and GBS

Reference was made to the main components of Ea73 CFS obtained by LC–MS/MS by Tang et al. (16). Compounds with a relative content greater than 1% were selected, and the SMILE names of the main components were obtained in Pubchem.1 These were then imported into the Swiss target prediction database.2 The species was selected as “homo sapiens,” and targets with a probability value greater than 0 were screened and used as gene targets. The keyword “Streptococcus agalactiae” was entered into the DisGeNET database3 and the GeneCards database4 and the genes with a relevance score > 5.0 were selected in the GeneCards database. The results obtained from the two databases were summarized, and duplicates were removed to obtain the disease gene targets (19).

2.11.2 Analysis of the disease network mediated by Ea73 CFS main components, targets, and S. agalactiae

The interaction between the main active ingredient targets of Ea73 CFS and S. agalactiae targets was analyzed using the Venny 2.1.05 website, and the intersection gene targets were obtained. The PPI network diagram was constructed using Cytoscape 3.9.1 software, and the centrality of each node was calculated using the Centiscape 2.2 plug-in (20).

2.11.3 Construction of a target network for EA73 CFS and bovine mastitis (PPI network construction)

Using the STRING6 platform, we imported common targets related to the main active ingredient of EA73 CFS and S. agalactiae-mediated disease targets. We set the target to “Streptococcus agalactiae” and selected the highest confidence level of 0.900. We then hid the free gene nodes and obtained protein–protein interaction relationships.

2.11.4 GO functional annotation and KEGG signaling pathway enrichment analysis

We performed enrichment analysis on shared drug-disease targets in the DAVID database7 with “official gene symbol” as the identifier, “S. agalactiae” as the species, and used microbial information to generate GO and KEGG enrichment analyses. The top 20 p-values were selected as the screening criteria, and the GO and KEGG enrichment analyses were performed by microbial letter mapping.8 GO functional analysis included biological process (BP), molecular function (MF), and cellular component (CC). The results were also visualized through the microbiology platform.

2.11.5 Molecular docking computer simulation verification

Molecular docking verification was performed on the main active ingredient and core target protein of the core drug pair using AutoDock Vina 1.1.2. The structures of the core target protein and the top three active ingredients of the effector target were downloaded from the PDB and pubchem websites9, respectively. After docking, the structures were visualized using PyMOL 2.6.

3 Results

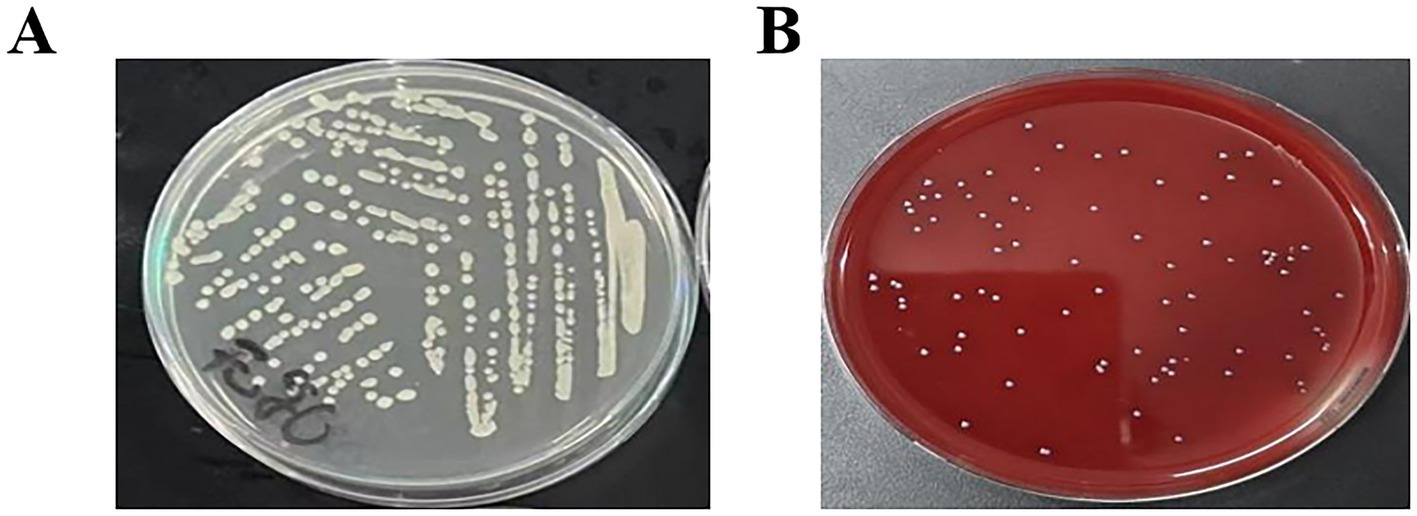

3.1 Morphological observation

The isolated strain was streaked onto ordinary plates and blood plates, and cultured at 37 °C for 24 h. As shown in Figures 1A,B, the colony morphology was white, round, with neat edges and a smooth and moist surface.

Figure 1. Characteristics of isolated S. agalactiae colonies (A). Characteristics of isolated colonies (LB agar plate) (B). Characteristics of isolated colonies (Blood agar plate).

3.2 Antibacterial activity assay

The S. agalactiae bacterial solution was spread on blood agar plates and ordinary agar plates for comparison. The diameter of the inhibition zone of Ea73 CFS against S. agalactiae was measured. The diameter of the inhibition zone of Ea73 CFS against S. agalactiae was measured on the blood agar plate was 14 mm, and that on the LB agar plate was 12 mm. Based on the criteria that the inhibition zone diameter ≥ 20 mm is extremely sensitive, 15–20 mm is highly sensitive, 10–15 mm is moderately sensitive, and less than 10 mm is low sensitive, S. agalactiae was determined to be moderately sensitive to Ea73 CFS, and hence have a good antibacterial activity.

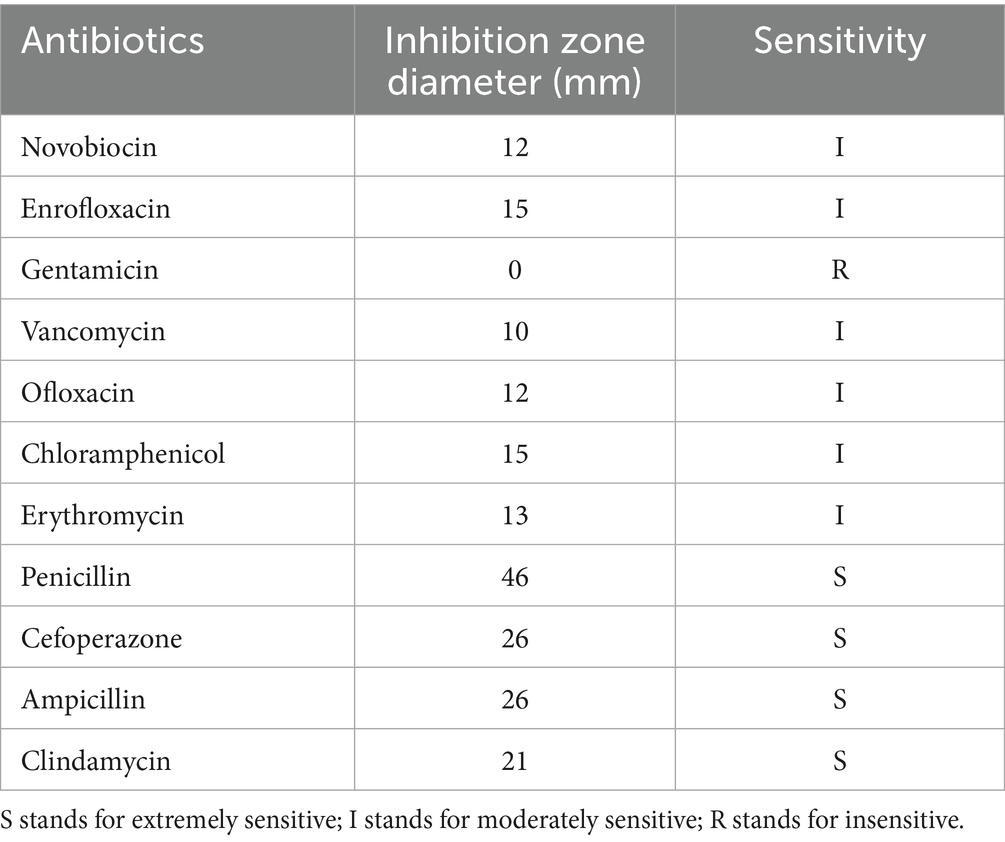

3.3 Antibiotics susceptibility testing

11 Antibiotics were used for the antibiotic susceptibility testing. The results are shown in Table 1. S. agalactiae strains exhibited varying susceptibility to the 11 antimicrobial susceptibility tablets. The strains were most sensitive to penicillin, cefoperazone, ampicillin, and clindamycin, while exhibiting lower susceptibility to the commonly used clinical drug gentamicin.

3.4 Minimum inhibitory concentration determination

After 24 h of S. agalactiae culture, Ea73 CFS concentrations of 0.00625 g/mL, 0.003125 g/mL, 0.0015625 g/mL, and 0.00078125 g/mL had minimal effects on S. agalactiae proliferation, with no significant differences compared to the control group (0 mg/mL). However, Ea73 CFS concentrations of 0.2 g/mL, 0.1 g/mL, 0.05 g/mL, 0.025 g/mL, and 0.0125 g/mL significantly decreased S. agalactiae proliferation compared to the control group (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The minimum inhibitory concentration of Ea73 CFS against S. agalactiae.* p < 0.05; *** p < 0.001; **** p < 0.000 compared to control.

3.5 Effect of Ea73 CFS on S. agalactiae biofilm

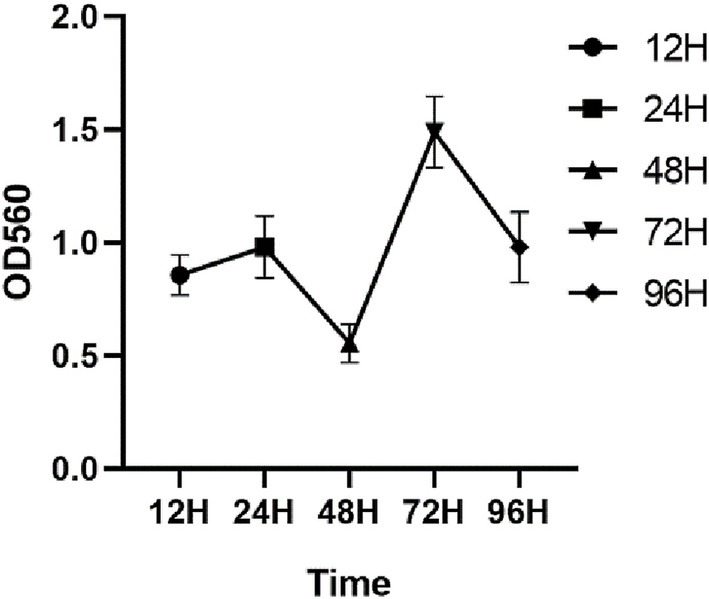

3.5.1 Film formation ability assay

As shown in Figure 3, the OD values increased progressively with an increase in the incubation time, attaining a peak value of 1.01 at 24 h, indicative of a robust biofilm-forming capacity in this strain (21), and the OD peak suggests that the biofilm at this time reached the maturation stage. The OD value decreased at 42 h, and this stage corresponded to the dispersion stage of the biofilm, where part of the biofilm detached from the bacteria and returned to the planktonic state, dispersed to new parts of the bacteria, and carried out a new round of biofilm colonization at this point of disintegration and dispersal, which corresponded to the secondary elevation of the OD value at 72 h.

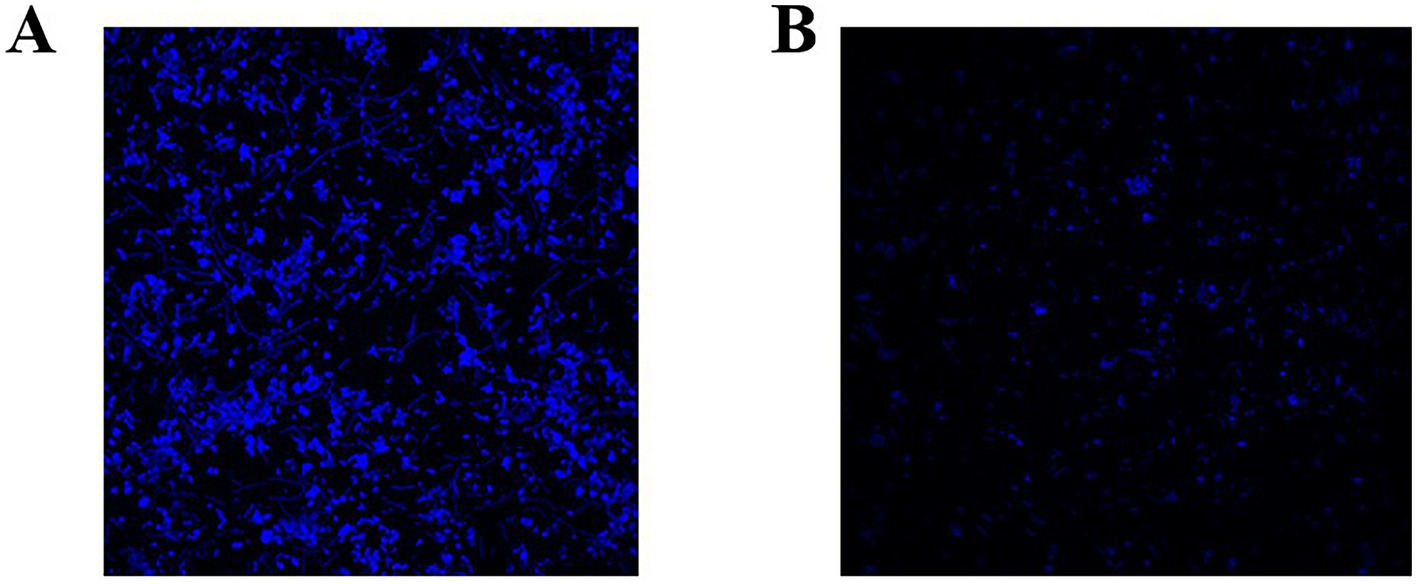

3.5.2 Laser confocal microscopy results

Microscopic observations revealed that after treatment with 1/2 MBIC (5 mg/mL) of Ea73 CFS, the fluorescence intensity of the S. agalactiae standard strain decreased significantly (Figure 4). The three-dimensional structure of the biofilm disintegrated, with most of the biofilm becoming loose and scattered. These results indicate that Ea73 CFS treatment disrupts the three-dimensional structure of the S. agalactiae biofilm, reducing bacterial adhesion and aggregation, leading to the excretion of intracellular substances and bacterial death.

Figure 4. Representative S. agalactiae biofilms stained with LIVE/DEAD Kit and analyzed using fluorescence microscopy. (A) Control group and (B) 1/2 MIC group. The purple fluorescence indicates the live cells, whereas the red fluorescence indicates the dead cells or cells with a damaged cell wall.

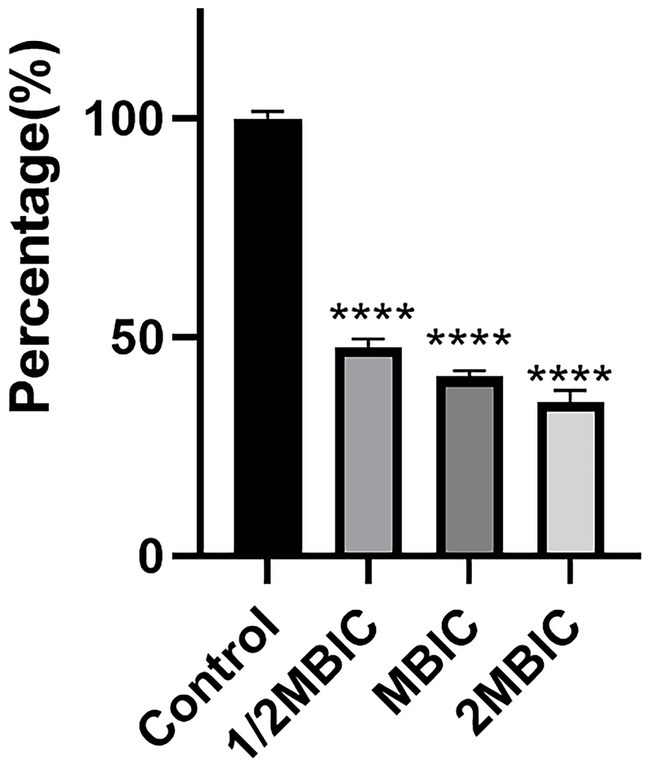

3.5.3 Effect of Ea73 CFS on bacterial metabolism in S. agalactiae biofilms

The metabolic capacity of bacteria can, to a certain extent, reflect the viability of bacterial cells. As shown in Figure 5, after treatment with Ea73 CFS at concentrations of 1/2MBIC, MBIC, and 2MBIC, the metabolic activity of the S. agalactiae biofilm decreased by 52.2, 58.9, and 64.8%, respectively. This may be because the electron transport chain for energy transfer during bacterial metabolism is mainly located on the inner surface of the cell membrane. However, after being stimulated and damaged by Ea73 CFS, the cell membrane loses its function of transferring energy and conducting metabolism, and thus its metabolic activity is greatly reduced.

Figure 5. Effects of Ea73 CFS on bacterial metabolism in S. agalactiae biofilms.* p < 0.05; *** p < 0.001; **** p < 0.000 compared to control.

3.5.4 Enzyme hydrolysis experiment

As shown in Figure 6, the amount of biofilm decreased the most after proteinase K treatment, by approximately 72.2%, while the amount of biofilm decreased the least after DNase I treatment, by only 5.2%. The results also showed that the highest content of S. agalactiae biofilms was protein, followed by exopolysaccharides and eDNA.

Figure 6. Enzymatic hydrolysis experiment. * p < 0.05; *** p < 0.001; **** p < 0.0001 compared to control.

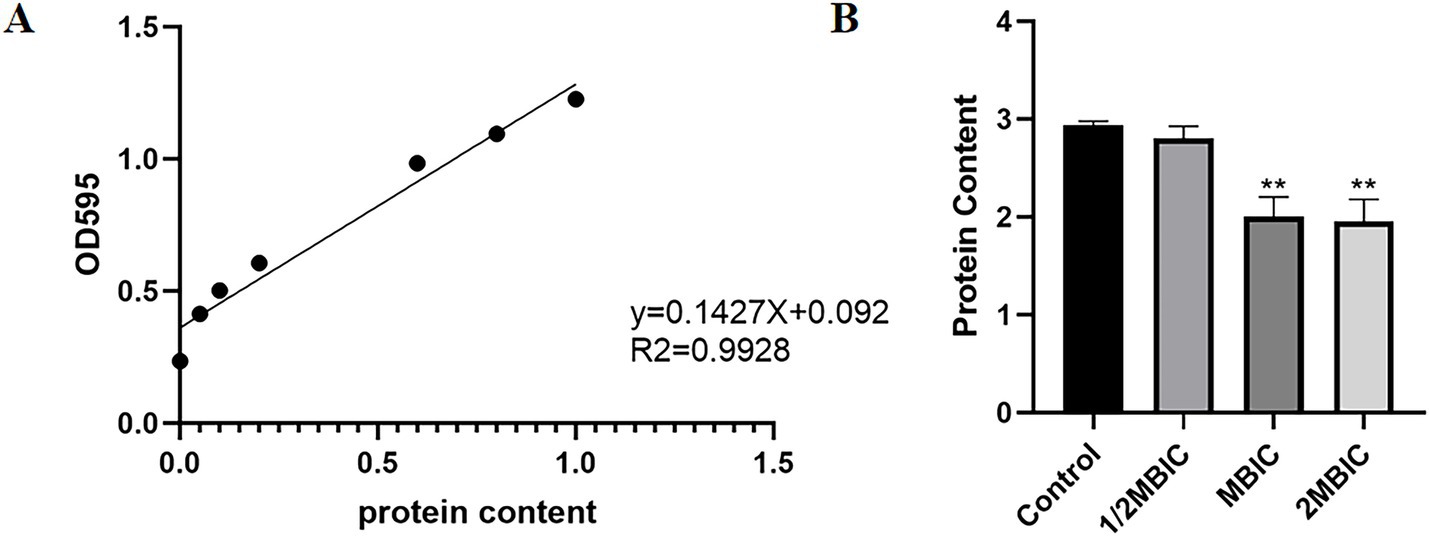

3.5.5 Effect of Ea73 CFS on extracellular proteins

As shown in Figure 7A, the standard curve equation for protein is: y = 0.1427X + 0.092 (R2 = 0.9928). Using this standard curve, the effect of Ea73 CFS on the extracellular protein content in S. agalactiae biofilms were determined. As shown in Figure 7B, treatment with 20 mg/mL of Ea73 CFS reduced the extracellular protein content by 87.92%. This indicates that Ea73 CFS significantly inhibits the formation of extracellular proteins in S. agalactiae biofilms and significantly suppresses their synthesis and secretion.

Figure 7. (A) Standard curve of protein; (B) Effect of Ea73 CFS on extracellular proteins in S. agalactiae biofilms.* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01 compared to control.

3.6 Ea73 CFS network pharmacology analysis results

3.6.1 Common targets of the main components of Ea73 CFS and S. agalactiae-mediated diseases

A Swiss Target Prediction analysis (p > 0.5) identified 370 potential active ingredient targets of EA73 CFS and 158 S. agalactiae-mediated disease targets through the GeneCards and DisGeNET databases. These targets were imported into Venn 2.1.0 and the intersection of the two databases was determined, resulting in 14 shared targets, as shown in the Figure 8.

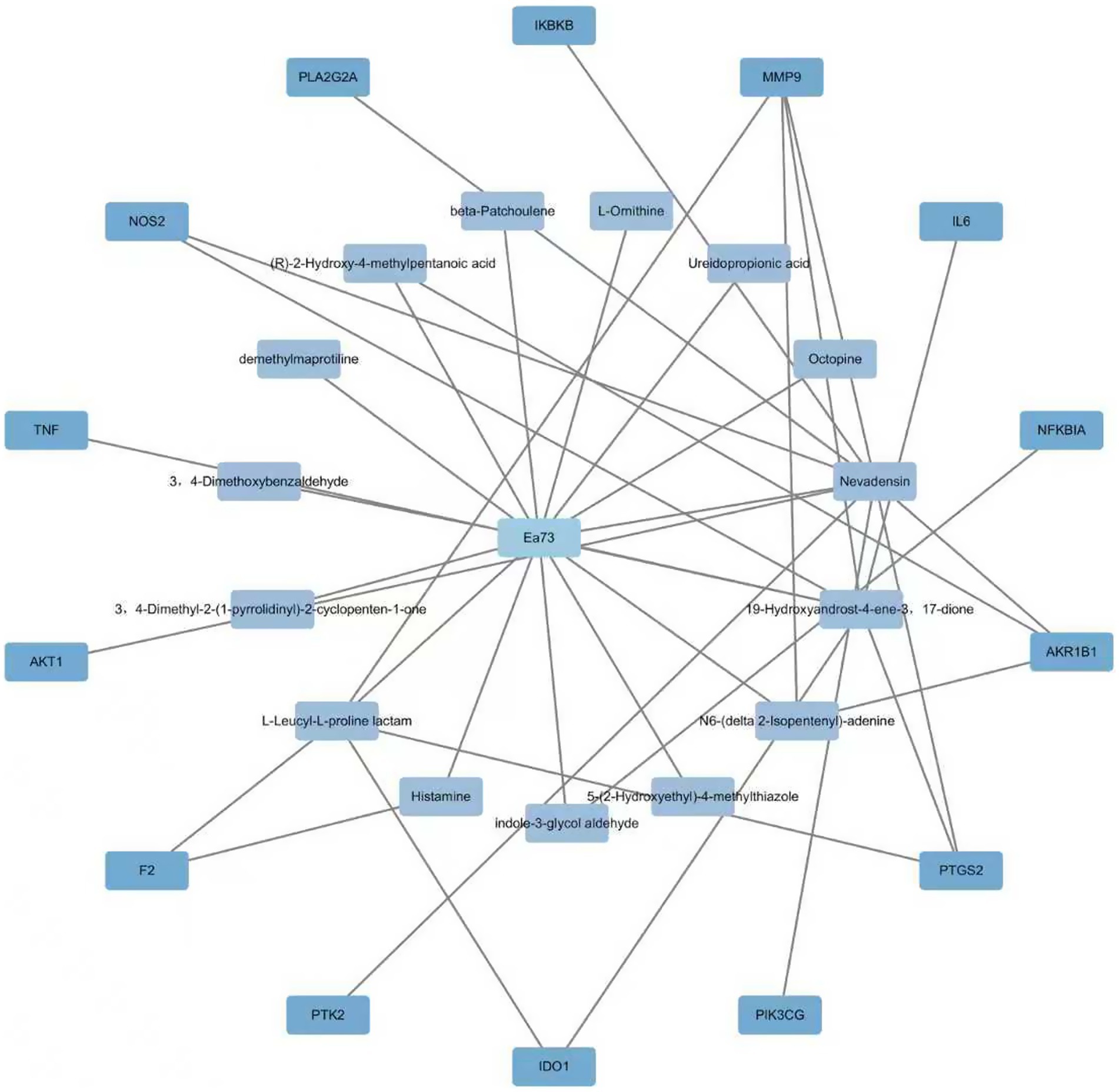

3.6.2 Ea73 CFS main component-target-GBS-mediated disease network

The Swiss Target Prediction database identified 14 potential targets for Ea73 CFS main components. These targets were imported into Cytoscape 3.9.1 to create a visual network diagram, as shown in Figure 9. The connected edges represent the corresponding drug-active ingredient-target-disease interactions. Nevadensin, 19-Hydroxyandrost-4-ene-3,17-dione, and L-Leucyl-L-proline lactam had the most targets, with degree values of 15, 10, and 5, respectively, suggesting that these components may play an important role in interactions with S. agalactiae-mediated diseases. At least two active ingredients were linked to each of the protein targets, including MMP9, PTGS2, AKR1B1, NOS2, IDO1, and F2. This suggests that these protein targets may be potential targets for S. agalactiae-mediated diseases.

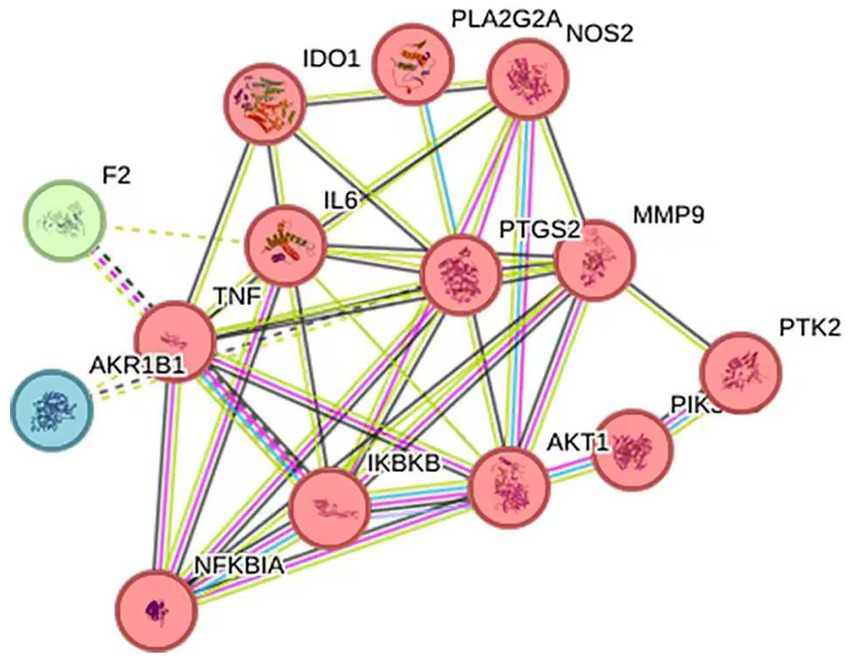

3.6.3 PPI network

The 14 intersection targets obtained in 2.6.1 were input into the String database, and the species “Streptococcus agalactiae” was selected to construct a protein–protein interaction network (Figure 10). This network had 14 nodes, 10 edges, and an average degree of 5.71. Protein targets with high degrees in this network include TNF, PTGS2, and IL6, with degrees of 10, 10, and 9, respectively. These targets may be important targets for Ea73 CFS in the treatment of bovine mastitis.

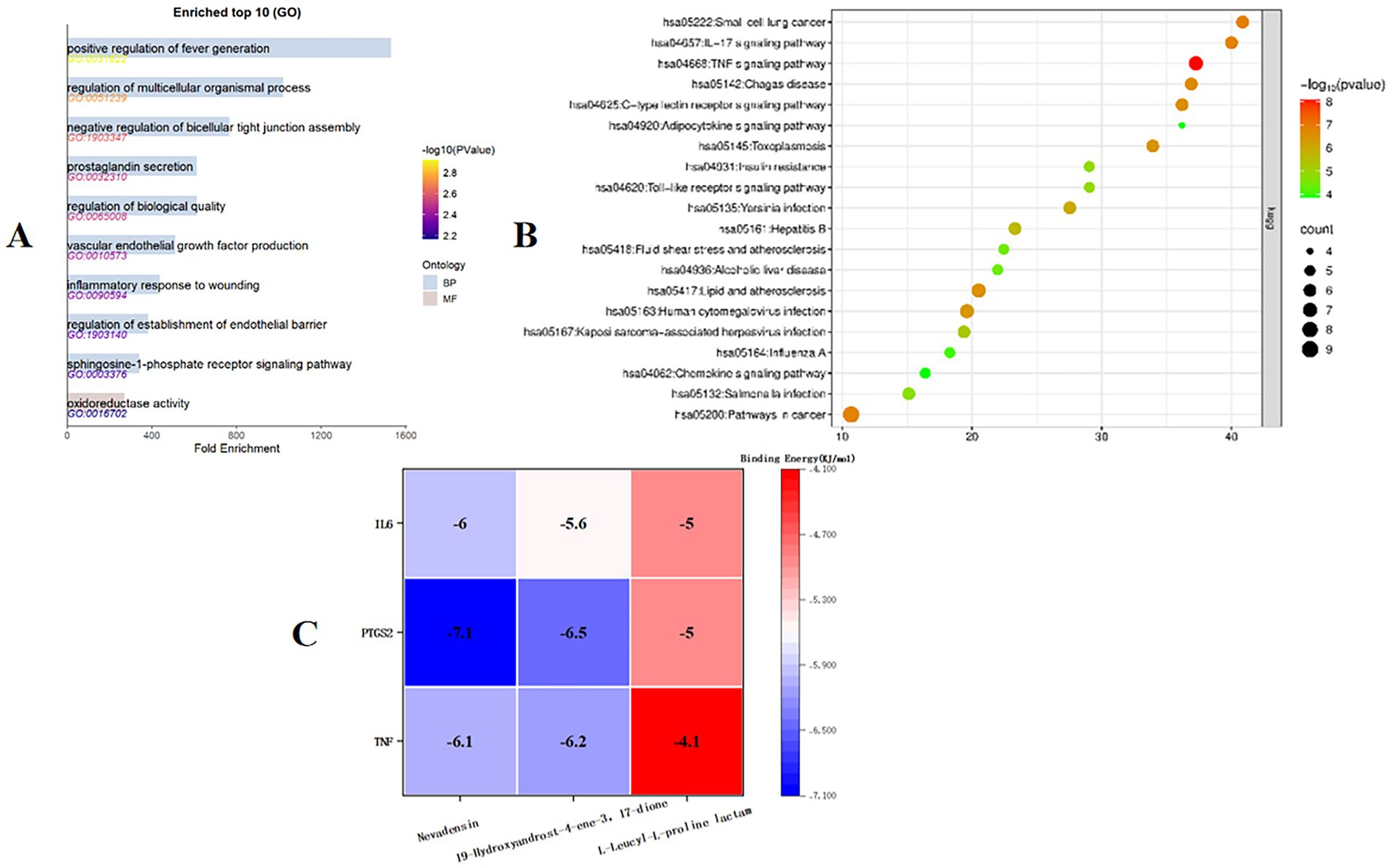

3.6.4 GO enrichment analysis and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis

GO and KEGG enrichment analysis of the 14 targets identified above was performed using the David online database, and the results were visualized using the Microbiology Information online mapping website. A total of 387 GO enrichment analysis results were obtained. The top 10 fold enrichment results (p < 0.05) are shown in Figure 11, including 9 biological processes (BPs) and 1 molecular function (MF). BPs were primarily associated with positive regulation of angiogenesis, regulation of multicellular biological processes, negative regulation of tight junction assembly, and prostaglandin secretion; MFs were primarily associated with oxidoreductase activity.

Figure 11. (A) Target GO enrichment analysis histogram. (B) Target signaling pathway enrichment analysis bubble chart. (C) Molecular docking binding energy heat map.

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis, shown in Figure 11, yielded 20 pathways. The enrichment results suggest that the antimicrobial mechanism of Ea73 CFS may be closely related to pathways such as small cell lung cancer, the IL-17 signaling pathway, the TNF pathway, and the C-type lectin receptor signaling pathway.

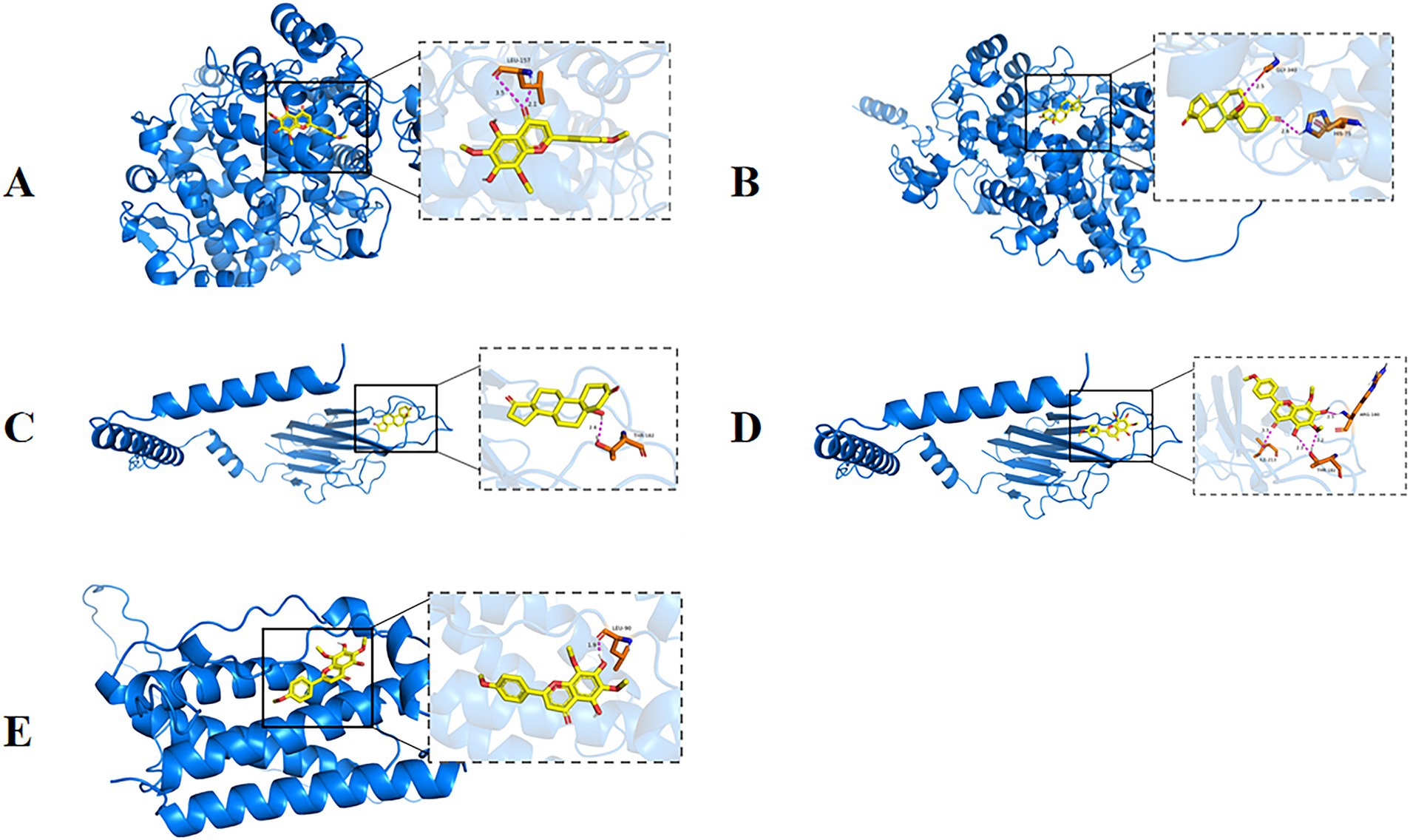

3.6.5 Molecular docking analysis

Autodock-vina was used to perform semi-flexible docking of the LC/MS–MS detection components and key targets. The resulting binding energy heat map is shown in Figure 11. The binding energy of the active ingredient of Ea73 CFS with the key target protein is basically lower than −5.0 kcal/mol, indicating that the receptor and ligand bind well. Among them, TNF, PTGS2, and IL6 have strong affinities with Nevadensin and 19-Hydroxyandrost-4-ene-3,17-dione, and hydrogen bonds are formed between the ligand and the protein, indicating that the structure after binding is in a highly stable state.

As shown in Figure 12A, nevadensin a ligand that effectively binds to the active pocket of the PTGS2 protein has a binding energy of −7.1 kcal/mol, indicating relatively strong binding between the two. Three-dimensional analysis revealed that the ligand forms hydrogen bonds with the LEU-157 amino acid residue in the PTGS2 protein and hydrophobic interactions with the ARGA442, LYSA445, and PROA148 amino acid residues. These interactions facilitate nevadensin’s binding to the active pocket of the PTGS2 protein, leading to the formation of a complex. As shown in Figure 12B, 19-Hydroxyandrost-4-ene-3,17-dione a ligand that effectively binds to the active pocket of the PTGS2 protein has a binding energy of −6.5 kcal/mol, indicating relatively strong binding between the two. Three-dimensional analysis revealed that the compound forms hydrogen bonds with the GLY340 and HIS75 amino acid residues of PTGS2, promoting the binding of 19-Hydroxyandrost-4-ene-3,17-dione to the active pocket of the PTGS2 protein, leading to the formation of a complex. As shown in Figure 12C, 19-Hydroxyandrost-4-ene-3,17-dione, as a ligand, binds effectively to the active pocket of the TNF protein with a binding energy of −6.2 kcal/mol, indicating relatively strong binding. Three-dimensional analysis revealed that the ligand forms hydrogen bonds with amino acid residue THR182 of the TNF protein and hydrophobic interactions with residues TRPA191, CYSA146, and LYSA189. These interactions facilitate the binding of 19-Hydroxyandrost-4-ene-3,17-dione to the active pocket of the TNF protein, ultimately forming a complex. As shown in Figure 12D, nevadensin, as a ligand, effectively binds to the active pocket of the TNF protein with a binding energy of −6.1 kcal/mol, indicating relatively strong binding between the two. Three-dimensional analysis revealed that the ligand forms hydrogen bonds with amino acid residues ILE213, THR182, and ARG180 of the TNF protein, and hydrophobic interactions with amino acid residues GLUA193 and CYSA146. These interactions facilitate the binding of nevadensin to the active pocket of the TNF protein, leading to the formation of a complex. As shown in Figure 12E, nevadensin, as a ligand, effectively binds to the active site of the IL6 protein with a binding energy of −6.0 kcal/mol, indicating relatively strong binding between the two. Three-dimensional analysis revealed that the ligand forms hydrogen bonds with the LEU90 amino acid residue of the protein and hydrophobic interactions with the LYSA94 and LEUA189 amino acid residues. These interactions facilitate nevadensin’s successful binding to the active site of the IL6 protein, ultimately forming a complex.

Figure 12. Partial diagram of molecular docking; (A) PTGS2-Nevadensin; (B) PTGS2-19-Hydroxyandrost-4-ene-3,17-dione; (C) AKT1-N6-(delta2-Isopentenyl)-adenine; (D) AKT1- Nevadensin; (E) IL6-Nevadensin.

4 Discussion

This study determined the minimum inhibitory concentration of Ea73 CFS against S. agalactiae and found that when the concentration of Ea73 CFS was 12.5 mg/mL, S. agalactiae showed significant inhibition. This was consistent with our previous study in that showed that at the same concentration, the inhibition diameter of Ea73 extract against Escherichia coli ATCC 35218, Salmonella H9812 and Staphylococcus aureus were approximately 10.57 ± 0.18 mm, 9.69 ± 0.17 mm, and 32.16 ± 2.04 mm, respectively, (9).

S. agalactiae has the characteristic of biofilm formation, which can effectively evade the immune clearance, phagocytosis, and bactericidal effects of traditional antibiotics in the body. Therefore, the biofilm of S. agalactiae plays an important role in causing subclinical mastitis and recurrent infections in dairy cows (2). Once pathogens form biofilms, they can effectively resist the entry of antibiotics into the membrane, reduce bacterial sensitivity to antibiotics, increase treatment difficulty, prolong medication time, and result in poor clinical treatment outcomes (22, 23). Bacteria can form small colony mutants within the biofilm in response to strong immune responses from infected hosts and induction by antibiotics, thus remaining in the host for a long time (24, 54). In this study, it was determined that the biofilm formation condition of the strain was at its peak after culturing at 37 °C for 24 h, indicating that the biofilm was in the mature stage at this time. In contrast, various studies have reported peak biofilm formation at 48 h incubation (25). The difference in the outcomes from our study may be due to the difference in culture media used in our studies (26). The minimum membrane inhibitory concentration of Ea73 CFS on S. agalactiae was determined to be 10 mg/mL according to the plate coating method. Laser confocal microscopy further confirms that treatment with 1/2MBIC of Ea73 CFS destroyed 90% of the biofilm stereo structure of S. agalactiae, leading to bacterial death and reducing bacterial population. This results are in consistent with results for other studies that show that the cell-free supernatant of probiotic bacteria such as Lactobacillus and Bacillus spp. exerted antibiofilm and antibacterial activities against various pathogenic bacteria (27–29).

Furthermore we observed that the metabolic activity of S. agalactiae biofilm was significantly reduced after treatment with Ea73 CFS, and the degree of reduction increased with increasing concentration. Similar results were observed in the study by Islam et al. (28) which reported that cell-free supernatants (CFSs) from the Culture of Bacillus subtilis inhibited Pseudomonas sp. biofilm formation.

One essential element and fundamental building block of the three-dimensional structure of bacterial biofilms is EPS (30). As can be seen in Figure 6, the extracellular polysaccharides and extracellular proteins of the S. agalactiae EPS matrix were reduced by EA73 CFS, and the main structure of the S. agalactiae EPS matrix was disrupted. This finding is consistent with results that report that some Bacillus CFSs have a disruptive effect on the three-dimensional structure of S. aureus biofilms (16, 31). Further studies on the extracellular protein content showed that the proteins of S. agalactiae biofilm decreased by 87.92% when the concentration of Ea73 CFS was 20 mg/mL. Therefore, we speculated that Ea73 CFS can clear the biofilm and accelerate the death of S. agalactiae by inhibiting the synthesis and secretion of the protein component of the EPS.

From the GO results, the positive regulation of angiogenesis from the BP results suggests that Ea73 CFS downregulates angiogenesis related signaling pathways (such as the VEGF pathway). Reducing angiogenesis at the site of infection limits the spread and nutrient supply of S. agalactiae (32). EA73 CFS may regulate the activation of multicellular biological processes, which reshape the infectious microenvironment and synergistically inhibit the pathogenicity of S. agalactiae by regulating the migration of inflammatory factors (such as IL-6, TNF - α) and immune cells (such as macrophages and neutrophils). Moreover, we also observed a negative regulation of tight junction assembly in cells. This finding implies that Ea73 CFS may enhance cell permeability and promote immune cell infiltration to clear pathogens by disrupting tight junction proteins (such as ZO-1, occludin) in breast epithelium (33). Prostaglandin secretion is directly related to PTGS2 function (34). Combined with the docking results, Nevadensin inhibits PTGS2 activity, suggesting that Ea73 CFS may alleviate local inflammation by inhibiting the synthesis of inflammatory mediator prostaglandin E2, reducing the impact on vascular permeability and pain response (35). The regulation of oxidoreductase activity may be achieved by modulating the redox balance of the host pathogen microenvironment, such as enhancing the activity of antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD) to alleviate oxidative stress damage, thereby inhibiting the survival of S. agalactiae (36). This therefore indicates that Ea73 CFS inactivates S. agalactiae by targeting/inhibiting oxidoreductases (such as thioredoxin reductase) hence further weakening its pathogenicity.

From the KEGG pathway, we observed the association of Ea73 CFS withsmall cell lung cancer-related pathways. Thus, this suggests that Ea73 CFS may inhibit epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT), maintain the integrity of the breast epithelial barrier, and reduce the opportunity for pathogen invasion. The negative regulation of IL-17 pathway by Ea73 CFS indicates that Ea73 can reduce neutrophil infiltration and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (such as IL-1β, IL-6), thereby alleviating excessive inflammatory response caused by Streptococcus agalactiae infection and avoiding tissue damage. In addition, the association between the IL-17 pathway and Th17 cell differentiation may be inhibited by endophytic bacteria by regulating the balance of Treg cells, further stabilizing the immune microenvironment (37). The regulation of TNF pathway by Ea73 (such as downregulating TNF-α and TNFR1 expression) indicates that Ea73 can block the activation of NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways, and inhibit the inflammatory cytokine storm induced by S. agalactiae (such as IL-8 and MCP-1). Furthermore, due to the association between TNF pathway and cell apoptosis, Ea73 CFS may indirectly activate anti apoptotic signals (such as PI3K/Akt) to protect host cells from pathogen toxin damage (38, 39).

Molecular docking showed that Nevadensin and 19-Hydroxyandrost-4-ene-3, 17 dione components can effectively bind to TNF, PTGS2, and IL6 protein receptors. TNF, PTGS2, and IL6 are all host proteins. TNF-α (tumor necrosis factor alpha) is a core inflammatory mediator in S. agalactiae infection (40). Numerous researches have shown that S. agalactiae activates the TNF-α signaling pathway in the host immune system, triggering a strong inflammatory response and promoting the recruitment and activation of neutrophils and macrophages, thereby enhancing its ability to clear bacteria (40–43). In addition, TNF-α can further amplify the inflammatory cascade by activating the NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways, leading to tissue damage and pathological changes (44, 45). PTGS2 (prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase 2, also known as COX-2) is mainly involved in the synthesis of inflammatory mediators in S. agalactiae infection (46). This enzyme catalyzes the conversion of arachidonic acid into prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), which exacerbates local inflammation by regulating vascular permeability and pain response (47). Studies have reported that host tissues without Streptococcus spp. infection, overexpression of PTGS2 is closely associated with inflammatory tissue damage, and its activity is positively regulated by the NF-κB and IL-1β signaling pathways [(48); LaRock and Nizet, 2014]. IL-6 (interleukin-6) is a key immune regulatory factor in Streptococcus agalactiae infection (49). It promotes Th17 cell differentiation by activating the JAK-STAT3 signaling pathway, enhances neutrophil mediated bacterial clearance ability, but may also trigger excessive inflammatory responses (such as cytokine storms) (50, 51).

The major limitation of the study is not identifying specific compounds from the many secondary metabolites produced by this endophyte and investigating its antibacterial properties. Thus, in future studies, the plan is to identify and isolate anti-biofilm-specific secondary metabolites and confirm their activity on various pathogenic bacteria.

5 Conclusion

This study demonstrates that Bacillus velezensis Ea73 CFS can effectively inhibit the proliferation of bovine-derived S. agalactiae via multi-target pathways including inhibiting biofilm formation, regulating inflammatory factors, and immune function.

Therefore, bioactive compounds with anti-biofilm activities can be isolated from Bacillus velezensis EA73. These results provide a theoretical basis for the development of new antibacteria agents against S. agalactiae and other biofilm forming bacteria.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/supplementary material.

Author contributions

SP: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. SO: Writing – original draft, Data curation. LC: Data curation, Writing – original draft. ZT: Project administration, Methodology, Writing – original draft. FY: Visualization, Writing – original draft. XL: Visualization, Writing – original draft. YH: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by the Science and Technology Support Program, grant number 2015SZ0201, and the Key Research and Development Project of Sichuan Province, grant number 2020YFS0337.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

S. agalactiae or GBS, Streptococcus agalactiae; MIC, Minimum Inhibitory Concentration; MBIC, Minimum biofilm inhibitory concentration; CFS, Cell-free supernatant; GO, Gene Ontology; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; PPI, Protein–protein interaction; BP, Biological process; CC, Cellular component; MF, Molecular function.

Footnotes

1. ^https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, accessed on 12 April 2025

2. ^http://www.swisstargetprediction.ch/

3. ^https://www.disgenet.com/, accessed on 12 April 2025

5. ^https://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/, accessed 15 April, 2025

6. ^https://string-db.org/, accessed on 15 April, 2025

7. ^https://david.ncifcrf.gov/, accessed on 12 April, 2025

8. ^https://www.bioinformatics.com.cn/, accessed on 12 May, 2025

References

1. Abebe, R, Markos, A, Abera, M, and Mekbib, B. Incidence rate, risk factors, and bacterial causes of clinical mastitis on dairy farms in Hawassa City, southern Ethiopia. Sci Rep. (2023) 13:10945. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-37328-1

2. Bonsaglia, ECR, Rossi, RS, Latosinski, G, Rossi, BF, Campos, FC, Junior, AF, et al. Relationship between biofilm production and high somatic cell count in Streptococcus agalactiae isolated from Milk of cows with subclinical mastitis. Pathogens (Basel, Switzerland). (2023) 12:311. doi: 10.3390/pathogens12020311

3. Pang, M, Sun, L, He, T, Bao, H, Zhang, L, Zhou, Y, et al. Molecular and virulence characterization of highly prevalent Streptococcus agalactiae circulated in bovine dairy herds. Vet Res. (2017) 48:65. doi: 10.1186/s13567-017-0461-2

4. Lohrmann, F, Hufnagel, M, Kunze, M, Afshar, B, Creti, R, Detcheva, A, et al. Neonatal invasive disease caused by Streptococcus agalactiae in Europe: the DEVANI multi-center study. Infection. (2023) 51:981–91. doi: 10.1007/s15010-022-01965-x

5. Tomanić, D, Samardžija, M, and Kovačević, Z. Alternatives to antimicrobial treatment in bovine mastitis therapy: a review. Antibiotics (Basel, Switzerland). (2023) 12:683. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics12040683

6. Song, HX. Effects of invasive plant Eupatorium adenophorum on soil nutrients and biological diversity. Guangdong Agric Sci. (2014) 18:51–6.

7. Huang, R, Okyere, SK, Shao, C, Yousif, M, Liao, F, Wang, X, et al. Hepatotoxicity effects of Ageratina adenophora, as indicated by network toxicology combined with metabolomics and transcriptomics. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. (2023) 267:115664. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2023.115664

8. Ren, Z, Okyere, SK, Wen, J, Xie, L, Cui, Y, Wang, S, et al. An overview: the toxicity of Ageratina adenophora on animals and its possible interventions. Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22:11581. doi: 10.3390/ijms222111581

9. Ren, Z, Xie, L, Okyere, SK, Wen, J, Ran, Y, Nong, X, et al. Antibacterial activity of two metabolites isolated from endophytic bacteria Bacillus velezensis Ea73 in Ageratina adenophora. Front Microbiol. (2022) 13:860009. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.860009

10. Wen, J, Okyere, SK, Wang, S, Wang, J, Huang, R, Tang, Z, et al. Antibacterial activity and multi-targeted mechanism of action of suberanilic acid isolated from Pestalotiopsis trachycarpicola DCL44: an endophytic fungi from Ageratina adenophora. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland). (2024) 29:4205. doi: 10.3390/molecules29174205

11. Wen, J, Okyere, SK, Wang, S, Wang, J, Xie, L, Ran, Y, et al. Endophytic fungi: an effective alternative source of plant-derived bioactive compounds for pharmacological studies. J Fungi (Basel, Switzerland). (2022) 8:205. doi: 10.3390/jof8020205

12. Chanu, KD, Sharma, N, Kshetrimayum, V, Chaudhary, SK, Ghosh, S, Haldar, PK, et al. Ageratina adenophora (Spreng.) King & H. Rob. standardized leaf extract as an antidiabetic agent for type 2 diabetes: an in vitro and in vivo evaluation. Front Pharmacol. (2023) 14:1178904. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2023.1178904

13. Chanu, KD, Thoithoisana, S, Kar, A, Mukherjee, PK, Radhakrishnanand, P, Parmar, K, et al. Phytochemically analysed extract of Ageratina adenophora (Sprengel) RM King & H. Rob. initiates caspase 3-dependant apoptosis in colorectal cancer cell: a synergistic approach with chemotherapeutic drugs. J Ethnopharmacol. (2024) 322:117591. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2023.117591

14. Chauhan, A, Rathod, S, Aneja, R, Kamboj, N, and Saini, VK. Harnessing the potential of Eupatorium adenophorum: activated carbon synthesis, optimization and antimicrobial properties. Process Saf Environ Prot. (2025) 201:107574. doi: 10.1016/j.psep.2025.107574

15. Li, H, Zhao, R, Pan, Y, Tian, H, and Chen, W. Insecticidal activity of Ageratina adenophora (Asteraceae) extract against Limax maximus (Mollusca, Limacidae) at different developmental stages and its chemical constituent analysis. PLoS One. (2024) 19:e0298668. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0298668

16. Tang, Z, Yousif, M, Okyere, SK, Liao, F, Peng, S, Cheng, L, et al. Anti-biofilm properties of cell-free supernatant from Bacillus velezensis EA73 by in vitro study with Staphylococcus aureus. Microorganisms. (2025) 13:1162. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms13051162

17. Pourhajibagher, M, Alaeddini, M, Etemad-Moghadam, S, Rahimi Esboei, B, Bahrami, R, Miri Mousavi, RS, et al. Quorum quenching of Streptococcus mutans via the nano-quercetin-based antimicrobial photodynamic therapy as a potential target for cariogenic biofilm. BMC Microbiol. (2022) 22:125. doi: 10.1186/s12866-022-02544-8

18. Shukla, SK, and Rao, TS. Effect of calcium on Staphylococcus aureus biofilm architecture: a confocal laser scanning microscopic study. Colloids Surf B: Biointerfaces. (2013) 103:448–54. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2012.11.003

19. Liao, F, Yousif, M, Huang, R, Qiao, Y, and Hu, Y. Network pharmacology-and molecular docking-based analyses of the antihypertensive mechanism of Ilex kudingcha. Front Endocrinol. (2023) 14:1216086. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2023.1216086

20. Wang, D, Tang, W, Sun, N, Cao, K, Li, Q, Li, S, et al. Uncovering the mechanism of Scopoletin in ameliorating psoriasis-like skin symptoms via inhibition of PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. Inflammation. (2024) 48:2258–73. doi: 10.1007/s10753-024-02188-y

21. Khasawneh, AI, Himsawi, N, Abu-Raideh, J, Salameh, MA, Al-Tamimi, M, Mahmoud, SAH, et al. Status of biofilm-forming genes among Jordanian nasal carriers of methicillin-sensitive and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Iran Biomed J. (2020) 24:386–98. doi: 10.29252/ibj.24.6.381

22. Azeem, K, Fatima, S, Ali, A, Ubaid, A, Husain, FM, and Abid, M. Biochemistry of bacterial biofilm: insights into antibiotic resistance mechanisms and therapeutic intervention. Life. (2025) 15:49. doi: 10.3390/life15010049

23. Zhao, A, Sun, J, and Liu, Y. Understanding bacterial biofilms: from definition to treatment strategies. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. (2023) 13:1137947. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2023.1137947

24. Ehrlich, GD, Ahmed, A, Earl, J, Hiller, NL, Costerton, JW, Stoodley, P, et al. The distributed genome hypothesis as a rubric for understanding evolution in situ during chronic bacterial biofilm infectious processes. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. (2010) 59:269–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2010.00704.x

25. Cho, JA, Roh, YJ, Son, HR, Choi, H, Lee, JW, Kim, SJ, et al. Assessment of the biofilm-forming ability on solid surfaces of periprosthetic infection-associated pathogens. Sci Rep. (2022) 12:18669. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-22929-z

26. Lu, J, Guevara, MA, Francis, JD, Spicer, SK, Moore, RE, Chambers, SA, et al. Analysis of susceptibility to the antimicrobial and anti-biofilm activity of human milk lactoferrin in clinical strains of Streptococcus agalactiae with diverse capsular and sequence types. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. (2021) 11:740872. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.740872

27. Drumond, MM, Tapia-Costa, AP, Neumann, E, Nunes, ÁC, Barbosa, JW, Kassuha, DE, et al. Cell-free supernatant of probiotic bacteria exerted antibiofilm and antibacterial activities against Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a novel biotic therapy. Front Pharmacol. (2023) 14:1152588. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2023.1152588

28. Islam, S, Mahmud, ML, Almalki, WH, Biswas, S, Islam, MA, Mortuza, MG, et al. Cell-free supernatants (CFSs) from the culture of Bacillus subtilis inhibit Pseudomonas sp. biofilm formation. Microorganisms. (2022) 10:2105. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10112105

29. Scillato, M, Spitale, A, Mongelli, G, Privitera, GF, Mangano, K, Cianci, A, et al. Antimicrobial properties of Lactobacillus cell-free supernatants against multidrug-resistant urogenital pathogens. Microbiolopen. (2021) 10:e1173. doi: 10.1002/mbo3.1173

30. Kranjec, C, Morales Angeles, D, Torrissen Mårli, M, Fernández, L, García, P, Kjos, M, et al. Staphylococcal biofilms: challenges and novel therapeutic perspectives. Antibiotics. (2021) 10:131. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10020131

31. Zhang, F, Wang, B, Liu, S, Chen, Y, Lin, Y, Liu, Z, et al. Bacillus subtilis revives conventional antibiotics against Staphylococcus aureus osteomyelitis. Microb Cell Factories. (2021) 20:102. doi: 10.1186/s12934-021-01592-5

32. Mo, XQ, Zhou, M, Wang, Y, and Guo, SJ. Robust MFC anti-windup scheme for LTI systems with norm-bounded uncertainty. Sci Rep. (2021) 11:1970. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-81036-7

33. Zhang, X, Liu, X, Chang, S, Zhang, C, Du, W, and Hou, F. Effect of Cistanche deserticola on rumen microbiota and rumen function in grazing sheep. Front Microbiol. (2022) 13:840725. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.840725

34. Lin, XM, Luo, W, Wang, H, Li, RZ, Huang, YS, Chen, LK, et al. The role of prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase-2 in chemoresistance of non-small cell lung cancer. Front Pharmacol. (2019) 10:836. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.00836

35. Lim, JR, Lee, HJ, Jung, YH, Kim, JS, Chae, CW, Kim, SY, et al. Ethanol-activated CaMKII signaling induces neuronal apoptosis through Drp1-mediated excessive mitochondrial fission and JNK1-dependent NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Cell Commun Signal. (2020) 18:123. doi: 10.1186/s12964-020-00572-3

36. Sastre-Oliva, T, Corbacho-Alonso, N, Albo-Escalona, D, Lopez, JA, Lopez-Almodovar, LF, Vázquez, J, et al. The influence of coronary artery disease in the development of aortic stenosis and the importance of the albumin redox state. Antioxidants. (2022) 11:317. doi: 10.3390/antiox11020317

37. Zhang, S, Gang, X, Yang, S, Cui, M, Sun, L, Li, Z, et al. The alterations in and the role of the Th17/Treg balance in metabolic diseases. Front Immunol. (2021) 12:678355. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.678355

38. Guerrache, A, and Micheau, O. TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand: non-apoptotic signalling. Cells. (2024) 13:521. doi: 10.3390/cells13060521

39. He, X, Li, Y, Deng, B, Lin, A, Zhang, G, Ma, M, et al. The PI3K/AKT signalling pathway in inflammation, cell death and glial scar formation after traumatic spinal cord injury: mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Cell Prolif. (2022) 55:e13275. doi: 10.1111/cpr.13275

40. Gao, J, Liu, M, Guo, H, Zhu, K, Liu, B, Liu, B, et al. ROS induced by Streptococcus agalactiae activate inflammatory responses via the TNF-α/NF-κB signaling pathway in Golden pompano Trachinotus ovatus (Linnaeus, 1758). Antioxidants. (2022) 11:1809. doi: 10.3390/antiox11091809

41. Chen, Y, Qu, J, Wang, S, Tang, M, Liao, S, Liu, Y, et al. Streptococcus agalactiae infection of a reconstructed human respiratory epithelium revealed infection and host response characteristics by different serotypes. Microb Pathog. (2025) 199:107243. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2024.107243

42. Janžič, L, Repas, J, Pavlin, M, Zemljić-Jokhadar, Š, Ihan, A, and Kopitar, AN. Macrophage polarization during Streptococcus agalactiae infection is isolate specific. Front Microbiol. (2023) 14:1186087. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1186087

43. Nguyen, HDT, Le, TM, Jung, DR, Jo, Y, Choi, Y, Lee, D, et al. Transcriptomic analysis reveals Streptococcus agalactiae activation of oncogenic pathways in cervical adenocarcinoma. Oncol Lett. (2024) 28:588. doi: 10.3892/ol.2024.14720

44. Jang, DI, Lee, AH, Shin, HY, Song, HR, Park, JH, Kang, TB, et al. The role of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) in autoimmune disease and current TNF-α inhibitors in therapeutics. Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22:2719. doi: 10.3390/ijms22052719

45. Pan, H, Li, H, Guo, S, Wang, C, Long, L, Wang, X, et al. The mechanisms and functions of TNF-α in intervertebral disc degeneration. Exp Gerontol. (2023) 174:112119. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2023.112119

46. Anamthathmakula, P, and Winuthayanon, W. Prostaglandin-Endoperoxide synthase 2 (PTGS2) in the oviduct: roles in fertilization and early embryo development. Endocrinology. (2021) 162:bqab025. doi: 10.1210/endocr/bqab025

47. Jang, Y, Kim, M, and Hwang, SW. Molecular mechanisms underlying the actions of arachidonic acid-derived prostaglandins on peripheral nociception. J Neuroinflammation. (2020) 17:30. doi: 10.1186/s12974-020-1703-1

48. Tomlinson, G, Chimalapati, S, Pollard, T, Lapp, T, Cohen, J, Camberlein, E, et al. TLR-mediated inflammatory responses to Streptococcus pneumoniae are highly dependent on surface expression of bacterial lipoproteins. J Immunol. (2014) 193:3736–45. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401413

49. Wilde, S, Olivares, KL, Nizet, V, Hoffman, HM, Radhakrishna, S, and LaRock, CN. Opportunistic invasive infection by group a Streptococcus during anti-Interleukin-6 immunotherapy. J Infect Dis. (2021) 223:1260–4. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa511

50. Gierlikowska, B, Stachura, A, Gierlikowski, W, and Demkow, U. The impact of cytokines on neutrophils’ phagocytosis and NET formation during sepsis—a review. Int J Mol Sci. (2022) 23:5076. doi: 10.3390/ijms23095076

51. Harbour, SN, DiToro, DF, Witte, SJ, Zindl, CL, Gao, M, Schoeb, TR, et al. TH17 cells require ongoing classic IL-6 receptor signaling to retain transcriptional and functional identity. Sci Immunol. (2020) 5:eaaw2262. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aaw2262

52. Rosini, R, and Margarit, I. Biofilm formation by Streptococcus agalactiae: influence of environmental conditions and implicated virulence factors. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. (2015) 5:6. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2015.00006

53. Okyere, SK, Xie, L, Wen, J, Ran, Y, Ren, Z, Deng, J, et al. Bacillus toyonensis SAU-19 ameliorates hepatic insulin resistance in high-fat diet/streptozocin-induced diabetic mice. Nutrients. (2021) 13:4512. doi: 10.3390/nu13124512

Keywords: Bacillus velezensis Ea73, Streptococcus agalactiae, in vitro antibacterial activity, biofilm formation, cell free supernatant

Citation: Peng S, Okyere SK, Cheng L, Tang Z, Yang F, Liu X and Hu Y (2025) In vitro antibacterial activity and mechanism of cell-free supernatant of Bacillus velezensis Ea73 against Streptococcus agalactiae, a predominant bacteria that causes mastitis in cows. Front. Vet. Sci. 12:1682691. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2025.1682691

Edited by:

Elena Franco Robles, University of Guanajuato, MexicoReviewed by:

Morenike Omotayo Adeola, Dennis Osadebay University, NigeriaSyeda Tasmia Asma, Afyon Kocatepe University, Türkiye

Copyright © 2025 Peng, Okyere, Cheng, Tang, Yang, Liu and Hu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yanchun Hu, aHljaHVuMTE0QDE2My5jb20=

Siqi Peng

Siqi Peng Samuel Kumi Okyere

Samuel Kumi Okyere Lin Cheng1

Lin Cheng1 Yanchun Hu

Yanchun Hu