- Department of Veterinary Clinical Sciences, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Visayas State University, Baybay City, Philippines

1 Introduction

Since African swine fever (ASF) was introduced to the Philippines in 2019, the country's swine industry has incurred substantial economic losses and a nationwide deficit in pork and pork-related products (1). As a result, the prices of basic commodities have increased, pushing minimum wage earners and 89% of small family farmers beyond the poverty line (2, 3). While high mortality rates caused by ASF explained the decline in the pig population, the enforcement of the stamping-out policy to control its spread may have dramatically contributed to the overall population decline (4, 5).

In the context of this article, stamping out refers to the depopulation of pigs, both from ASF-confirmed and potentially infected herds, within a defined infected zone to prevent disease transmission. In theory, this approach can rapidly contain outbreaks when implemented effectively (6, 7). However, its success relies on preconditions, including early outbreak detection, rapid response capacity, effective compensation mechanisms, and strict biosecurity compliance, all of which are often deficient in low-resource settings (8, 9). While stamping out based on zoning is recommended by the World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH) and has been shown to be effective when combined with other disease control strategies in some high-income countries (10), its implementation in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) has been fraught with challenges in terms of financial and human resources and farmers' acceptability (11, 12).

In the Philippines, outbreaks of ASF have highlighted the limitations of current policies for controlling transboundary animal diseases. This issue is particularly significant for smallholder pig production systems, which account for the majority of the country's pig sector (13, 14). Experiences in the Philippines suggest that implementing a blanket stamping-out policy may raise concerns among smallholder farmers, who are among the most vulnerable stakeholders during ASF epidemics. The primary objective of this article is to examine the challenges faced by the Philippines, particularly smallholder farmers, in implementing a stamping-out strategy, while also exploring potential approaches to address these challenges for comprehensive ASF control. Although the Philippines is used as a reference case, the broader issues of compliance, biosecurity, and stakeholder engagement may also be relevant to other LMICs with traditional pig production systems.

2 Key components of the stamping-out policy

The Terrestrial Animal Health Code of WOAH defines stamping out as a policy designed to eliminate animal disease outbreaks. This policy is implemented by an authorized veterinary agency, which refers to the governmental body of the member country holding the relevant mandate (15). In the Philippines, this authority is represented by the Department of Agriculture (DA). Stamping out has long been a fundamental component of a strategy for controlling transboundary animal diseases. When executed swiftly and comprehensively, it can effectively halt the spread of ASF and allow a country to regain its ASF-free status, provided that it is combined with early disease detection through active disease surveillance, outbreak investigation and tracing, quarantine and control of animal movement, and strict biosecurity measures (4, 16).

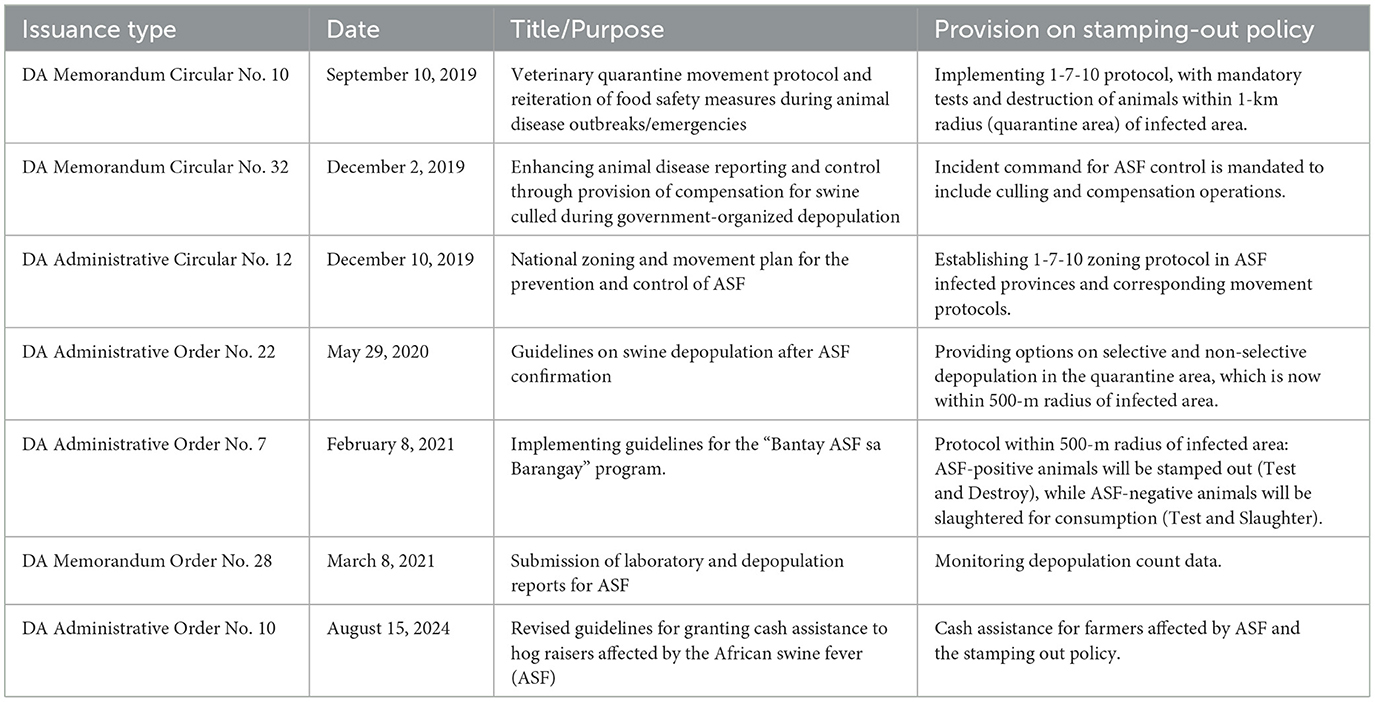

Stamping out can be classified into three primary components. First, it involves the humane culling of animals in a herd with confirmed disease, including those that have been exposed to infected animals within the infected zone, even in the absence of clinical signs. It also extends to other herds that have been exposed to infection, whether through direct or indirect contact, based on a defined measure of distance. In the Philippines, this policy has been outlined through a series of government issuances by the DA (Table 1) and is mainly governed by the DA-Regional Field Office and the Bureau of Animal Industry (BAI), in coordination with the Local Government Units (LGUs). Here, stamping-out policy is executed over a maximum period of 5 days within a defined radius from the infected farm, encompassing infected and exposed herds. The stamping-out radius is within a 500 m or 1 km, following a modified 1-7-10 zoning protocol. Second, the policy involves the proper disposal of carcasses, including animal products, through rendering, burning, or burial, as applicable. The preferred method in the Philippines is burial within the farm or premises. Lastly, the stamping-out policy requires a decontamination phase, which involves cleaning and disinfecting premises using methods tailored to the specific causative agent (15).

Table 1. Issuances from the Philippine Department of Agriculture (DA) relating to the ASF stamping-out policy.

3 Practical challenges of the stamping-out policy

In high-income countries with industrialized livestock systems, stamping out is supported by rapid diagnostics, a robust veterinary infrastructure, and reliable compensation schemes (17–19). Therefore, implementing the policy is resource-intensive and requires full governmental support, as the financial implications can be substantial. According to data from 2020 presented by Casal et al. (20), US$32 million of the economic impact of ASF in the Philippines is attributable to the stamping-out efforts, which accounted for 55% of the total US$58.7 million expenses or loss. On average, this translates to stamping-out costs of around US$1,772 per outbreak. Its financial implication is not limited to the Philippines, with Vietnam spending 89.1% of its total outbreak costs in a similar year (20).

The amount of funding needed to mobilize a stamping-out plan in a single outbreak raises questions about its practicality in a resource-constrained country. In LMICs, where veterinary services are underfunded (21), the logistics of depopulation can lead to delays, errors, and even incomplete implementation (12). In most provinces, ASF may have spread silently due to insufficient surveillance and non-reporting of cases (22, 23). By the time an outbreak is officially confirmed, it may have extended beyond the initial foci. Hence, it prompts a crucial question: is implementing stamping out within infected zones effective in controlling outbreaks, considering delays in case reporting and even non-reporting, confirmatory diagnoses, and the deployment of responsible personnel?

Underreporting, as well as delayed reporting, can be traced back to farmers' reluctance to report ASF cases due to financial losses and the inadequate implementation of government surveillance against ASF (22, 24, 25). Based on local observations, most official reports of outbreaks are likely to occur after ASF has spread uncontrollably, as evidenced by the massive deaths of pigs across several backyard farms that cross barangay borders before the authorities officially declare an outbreak. There is also a significant time delay from the moment clinical ASF appears in the field to when a government laboratory produces a confirmatory test result (26). In the Philippines, stamping out can only be executed based on confirmed laboratory results, either from the Regional Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory (RADDL), the national Animal Disease Diagnosis and Reference Laboratory (ADDRL), or BAI-accredited laboratories (27). On average, each RADDL is responsible for one Philippine administrative region, which typically includes approximately two cities, 19 municipalities, and 2,540 barangays. Some of these locations can be as far as 140 kilometers away from the laboratory (28). The number and distance could raise concerns regarding the timeliness and responsiveness of the laboratories during widespread outbreaks, with a reported waiting time to receive an ASF confirmatory result ranging from 5 to 7 days (26). Moreover, once stamping out begins, several issues can arise regarding the lack of adequate disposal sites, inconsistent enforcement of quarantine measures, and other logistical limitations that further impede the effectiveness and practicality of the policy. The shortage of veterinarians within LGUs, who play a crucial role in disease control efforts, only exacerbates these challenges (29).

Another concern of the stamping-out policy is the issue of compensation. The Philippine government offered indemnities for culled pigs, but payments have often been delayed and insufficient. The situation has likely created widespread disincentives among farmers to report suspected cases. This feedback has prompted the government to revise its guidelines for granting cash assistance to ASF-affected farmers (DA Administrative Order No. 10, series of 2024). While budgetary constraints hinder implementation of indemnification, the operation of livestock insurance through the Philippine Crop Insurance Corporation (PCIC) has proven helpful during ASF outbreaks. However, coverage among farmers is still below the total farmer population, with an estimated 40.7% coverage in 2023. The fear of uncompensated losses has led to the concealment of outbreaks or the clandestine sale of sick animals, in hopes of recouping lost capital, which directly contributes to the further spread of the disease (14, 24, 25).

4 Acceptability of the stamping-out policy in rural communities

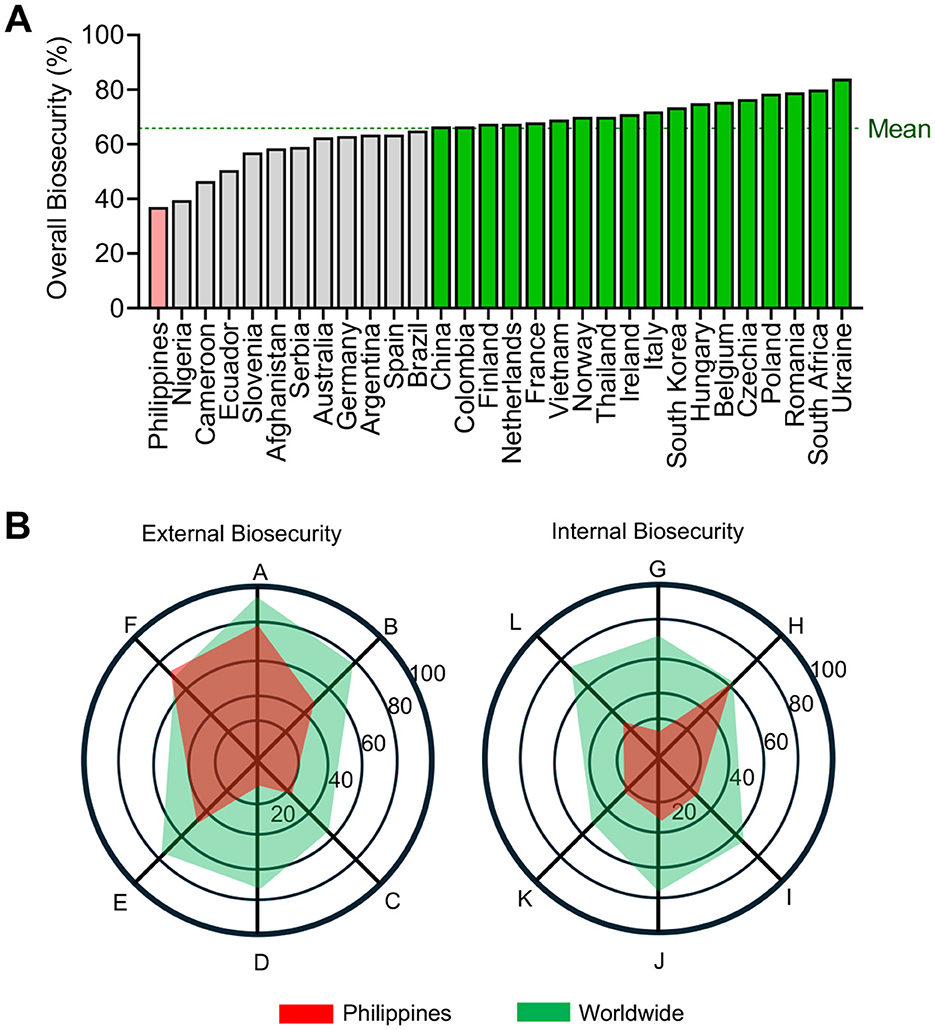

In the Philippines, around 68% informal smallholder backyard farms operate in resource-limited environments (30). Backyard farms often lack biosecurity measures, which are crucial for controlling the spread of ASF (9, 31). The 2,634 responses from the Philippines on the Biocheck.Ugent indicates that indoor pig farms in the country have the lowest overall biosecurity compliance compared to 29 other countries (Figure 1), making farmers vulnerable to the continuous threat of ASF.

Figure 1. Biosecurity compliance of indoor pig farms in different countries, with real farm inputs recorded by Biocheck.Ugent accessed on August 8, 2025. (A) The country-level of overall biosecurity compliance, with a global mean value of 65.9%. (B) External and internal biosecurity subcategories showing the global and the Philippines' average data for each component. Legend: A - Purchase of breeding pigs, piglets, and semen; B - Transport of animals, removal of carcasses, and manure; C - Feed, water, and equipment supply; D - Visitors and farmworkers; E - Vermin and bird control; F - Location of the farm; G - Disease management; H - Farrowing and suckling period; I - Nursing unit; J - Finishing unit; K - Measures between compartments, working lines and use of equipment; L - Cleaning and disinfection. 29,688 total responses, with 2,634 responses from the Philippines.

Raising backyard pigs holds cultural significance that extends beyond mere commodities. They are viewed as household assets and a form of savings that require minimal investment, often playing a role in community traditions (32). While backyard farmers assign value to their pigs based on subjective factors that exceed monetary measures (31), in most households, backyard pig rising is also a primary source of income (33). As a consequence of this perspective, farmers view the culling process negatively, particularly when animals are not exhibiting clinical signs (25), which can lead to potential resentment, mistrust, and trauma within the farmers' community (14).

When the stamping-out policy was implemented in several municipalities in the Visayas, anecdotal accounts indicated that farmers were quick to relocate their pigs to the mountains for concealment. In some cases, surviving pigs were sold to opportunistic buyers at a very low price to avoid total loss of capital. A few farmers were also adamant in rejecting the authority when told that their pigs would be included in the stamping out. These responses may reflect perceptions of inadequate financial assistance, unclear policies on live pig and pig product movements, a lack of defined recovery pathways, and limited support for transitioning to alternative livelihoods (34). Such perceptions are likely linked to insufficient engagement with farmers, where trust-building, clear communication, and the inclusion of stakeholder perspectives could have helped reduce resistance. The lengthy ASF bans on restocking, which can last over a year depending on compliance related to zoning status (Table 1), have also been affecting communities dependent on pig farming.

5 Beyond stamping-out policy in the Philippines

In the Philippines, many reported instances of ASF transmission have been associated with human behavior, including pig-raising practices, pig movement, and activities related to buying and selling live pigs, pork, and pork products (35, 36). The spread of ASF across administrative borders may reflect limited stakeholder awareness, or, at times, non-adherence to protocols, as suggested by reports of swill feeding, improper disposal of dead pigs, retention and sale of surviving pigs from affected herds, and animal movements despite zoning restrictions (22, 24, 25). These behaviors, however, are closely intertwined with poverty and marginalization, as many backyard farmers lack access to formal education and depend almost entirely on small-scale pig production, which may inadvertently sustain practices that increase disease risk (11, 37).

ASF transmission has therefore been facilitated, at least in part, by human actions, underscoring the expectation that community engagement and trust-building initiatives could play a crucial role in future control efforts (22). Local government units (LGUs), which are mandated to represent and serve their communities, may be well-positioned to lead such initiatives. When adequately supported, LGUs could help ensure that policies with substantial socio-economic consequences, such as stamping out, are communicated more effectively, while also providing space for dialogue on prevention and recovery strategies. The introduction of such policies is most likely to succeed when based on transparent communication and inclusive planning with local leaders and backyard farmers (38). Nonetheless, this approach has not yet been systematically evaluated in the context of ASF control, which represents a notable research gap in the Philippines. It is worth noting, however, that long-term strategies for other infectious diseases, such as foot and mouth disease (FMD), have included elements of community engagement in disease management. Such experiences suggest that community participation may have contributed to the eventual eradication of FMD in the Philippines, despite the application of stamping-out measures being limited to only a partial extent (39).

While stamping out remains an established tool for ASF control, its uniform application may present challenges in resource-limited settings. Some studies suggest that ASF control could benefit from context-sensitive strategies that include risk-based surveillance, selective culling, movement controls, and enhanced biosecurity practices (4, 12, 40). We expect that alternative approaches, if carefully designed, might also help safeguard indigenous farming systems that form part of the country's cultural identity. This could extend to efforts aimed at conserving local pig breeds and endemic wild pig populations, areas where the blanket application of the current stamping-out policy may face limitations in terms of feasibility and acceptability (40, 41).

The Philippine “Bantay ASF sa Barangay” program has outlined selective culling options across domestic pig production systems through “Test and Destroy” and “Test and Slaughter.” At this stage, these approaches appear more recommendatory than prescriptive, with limited operational detail available. Here, we discuss potential considerations that could inform their future implementation, while acknowledging the need for further policy refinement and field validation. The “Test and Destroy” policy is intended for ASF-positive pigs, allowing ASF-negative pigs to remain in the herd as assets and enter the food chain, potentially mitigating deficits in pork supply and reducing resource use compared to blanket stamping-out, as conducted in Vietnam (4).

The “Test and Slaughter” policy offers another alternative for ASF-negative pigs inside the infected zone, recommending that pigs undergo standard slaughtering procedures for human consumption in abattoirs with at least level “A” classification. Additional safeguards would likely be necessary to minimize transmission risks, such as processing pork (excluding offal), applying virus-deactivation methods (e.g., heating meat for ≥30 min at 70 °C) (15), and ensuring storage and distribution remain contained within the infected zone, or released only after testing processed pork for ASF. While a test-based culling system cannot fully overcome cultural and logistical challenges, it may help reduce resentment and resistance among farmers compared with blanket stamping-out, as previously reported in disagreements over the inclusion of apparently “healthy” pigs within affected zones (25, 42).

If supported by enhanced syndromic and risk-based surveillance with timely case reporting, one potential bottleneck may lie in the efficiency of confirmatory testing. A possible policy direction could be the decentralization of RADDL functions through the establishment of functional laboratories at the municipal and city levels. While this option may show potential, further evaluation is needed to assess its feasibility, sustainability, and effectiveness in strengthening ASF control in the Philippines. However, lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic highlight the critical importance of timely access to diagnostics and the value of expanding diagnostic capacity to reach even the most remote areas when developing preparedness and response plans (43).

Compartmentalization could also provide a viable option for sustaining international trade in subpopulations of pigs that adhere to strict biosecurity measures and are epidemiologically isolated from surrounding groups (44). While the stamping-out approach may restrict trade from affected regions, compartmentalization enables disease-free compartments to maintain exports of animals and products, as long as they comply with stringent surveillance, traceability, and biosecurity standards (18, 45). However, implementing and sustaining compartmentalization are primarily feasible for commercialized farms, notwithstanding that it can be challenging in resource-limited settings, where infrastructure and compliance capacity are often constrained (12). Thus, while it presents a viable opportunity to mitigate trade disruptions, its practical application for ASF control in the Philippines remains limited and requires substantial institutional and logistical support.

Lastly, improving biosecurity compliance remains a critical need in the Philippines for a holistic ASF control, particularly through innovations that adapt biosecurity protocols for backyard farming systems (35), or by gradually transitioning toward production systems where standard measures are more readily applied, such as medium- to large-scale farms (46). In small-hold settings, community-led biosecurity initiatives may be worth exploring as a means of encouraging shared responsibility among farmers, local leaders, and veterinary authorities (47). To support the harmonized application of biosecurity in scattered backyard farms, one possible strategy could be a cluster-based approach that organizes geographically close farms within a barangay. Such clusters might adopt cooperative systems to develop more standardized pig management practices and biosecurity measures. The government's role could focus on capacity development, farm registration, agricultural zoning, consistent outbreak surveillance, and engagement with farmers to lay down plans in case of an outbreak. Exploring alternative tools, such as zoning based on ASF risk levels and eventually ASF vaccination, could also yield more sustainable results.

6 Conclusion

The stamping-out policy has long been part of the Philippines' response to ASF. However, questions have been raised about its long-term practicality and social acceptability. In a country where pig farming is deeply ingrained in rural life and where veterinary systems continue to face challenges, stamping out the disease alone may not be sufficient; thus, the focus on disease control should be directed toward more comprehensive strategies. It may therefore be useful to consider complementary approaches that are pragmatic, community-oriented, and economically sensitive. Policymakers could aim to balance scientific rigor with socio-cultural realities, with the goal of ensuring that ASF control efforts do not inadvertently exacerbate rural poverty but instead support communities in moving toward more resilient and biosecure pig production systems.

Author contributions

HP: Methodology, Data curation, Project administration, Validation, Conceptualization, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Software, Formal analysis, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Investigation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. HP received funds for ASF research from the Department of Science and Technology-National Research Council of the Philippines (DOST-NRCP).

Acknowledgments

HP is grateful to the Local Government Unit (LGU) personnel and local pig farmers for sharing their experiences and insights about ASF during visits, workshops, and trainings. HP acknowledges the assistance of the Office of the Vice President for Research, Extension, and Innovation (OVPREI) of VSU and the Global Health Focus (GHF).

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Solely to enhance sentence and paragraph flow for improved clarity and readability. All ideas, interpretations, and original content in this document are entirely the result of human effort.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Hsu C-H, Montenegro M, Miclat-Sonaco R, Torremorell M, Perez AM. Validation of the effectiveness of pig farm repopulation protocol following African swine fever outbreaks in the Philippines. Front Vet Sci. (2024) 11:1468906. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2024.1468906

2. Weiss E, Kar A, Nash JD, Steven M Jaffee, Forno D, Briones R, et al. Realizing scale in Smallholder-Based Agriculture: Policy Options for the Philippines. Washington, DC: World Bank (2021).

3. Ebal LPA, Herrera MNQ, Cabral JS. An ARDL approach in studying the impact of ASF and selected factors on the Philippine pork market retail price. J Econ Manag Agric Dev. (2021) 7:119. doi: 10.22004/ag.econ.333538

4. Nga BTT, Padungtod P, Depner K, Chuong VD, Duy DT, Anh ND, et al. Implications of partial culling on African swine fever control effectiveness in Vietnam. Front Vet Sci. (2022) 9:957918. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.957918

5. Han M, Yu W, Clora F. Boom and bust in China's pig sector during 2018–2021: recent recovery from the ASF shocks and longer-term sustainability considerations. Sustainability. (2022) 14:6784. doi: 10.3390/su14116784

6. Geering WA, Penrith M-L, Nyakahuma D. Manual on the preparation of African swine fever contingency plans. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2001). p. 74.

7. Penrith M-L, Nyakahuma D. Manual on procedures for disease eradication by stamping out. Geering WA, Geering WA, editors. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2001). p. 130.

8. Gallardo C, Nieto R, Soler A, Pelayo V, Fernández-Pinero J, Markowska-Daniel I, et al. Assessment of African swine fever diagnostic techniques as a response to the epidemic outbreaks in eastern European Union countries: how to improve surveillance and control programs. J Clin Microbiol. (2015) 53:2555–65. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00857-15

9. Mutua F, Dione M. The context of application of biosecurity for control of African swine fever in smallholder pig systems: current gaps and recommendations. Front Vet Sci. (2021) 8:689811. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.689811

10. Danzetta ML, Marenzoni ML, Iannetti S, Tizzani P, Calistri P, Feliziani F. African swine fever: lessons to learn from past eradication experiences. A systematic review. Front Vet Sci. (2020) 7:296. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2020.00296

11. Perry B, Grace D. The impacts of livestock diseases and their control on growth and development processes that are pro-poor. Phil Trans R Soc B. (2009) 364:2643–55. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0097

12. Penrith M-L, Van Heerden J, Pfeiffer DU, Olševskis E, Depner K, Chenais E. Innovative research offers new hope for managing African swine fever better in resource-limited smallholder farming settings: a timely update. Pathogens. (2023) 12:355. doi: 10.3390/pathogens12020355

13. Fernandez-Colorado CP, Kim WH, Flores RA, Min W. African swine fever in the Philippines: a review on surveillance, prevention, and control strategies. Animals. (2024) 14:1816. doi: 10.3390/ani14121816

14. Cooper TL, Smith D, Gonzales MJC, Maghanay MT, Sanderson S, Cornejo MRJC, et al. Beyond numbers: determining the socioeconomic and livelihood impacts of African swine fever and its control in the Philippines. Front Vet Sci. (2022) 8:734236. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.734236

15. WOAH. Terrestrial animal health code. Paris, France: World Organization for Animal Health. (2019). p. 518.

16. Kim YJ, Park B, Kang HE. Control measures to African swine fever outbreak: active response in South Korea, preparation for the future, and cooperation. J Vet Sci. (2021) 22:e13. doi: 10.4142/jvs.2021.22.e13

17. Halasa T, Bøtner A, Mortensen S, Christensen H, Toft N, Boklund A. Control of African swine fever epidemics in industrialized swine populations. Vet Microbiol. (2016) 197:142–50. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2016.11.023

18. Costard S, Perez AM, Zagmutt FJ, Pouzou JG, Groenendaal H. Partitioning, a novel approach to mitigate the risk and impact of African swine fever in affected areas. Front Vet Sci. (2022) 8:812876. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.812876

19. Pavone S, Iscaro C, Dettori A, Feliziani F. African swine fever: the state of the art in Italy. Animals. (2023) 13:2998. doi: 10.3390/ani13192998

20. Casal J, Tago D, Pineda P, Tabakovski B, Santos I, Benigno C, et al. Evaluation of the economic impact of classical and African swine fever epidemics using OutCosT, a new spreadsheet-based tool. Transbounding Emerging Dis. (2022) 69:e2474–84. doi: 10.1111/tbed.14590

21. Van Veen TWS, De Haan C. Trends in the organization and financing of livestock and animal health services. Prev Vet Med. (1995) 25:225–40. doi: 10.1016/0167-5877(95)00540-4

22. Hsu C-H, Schambow R, Montenegro M, Miclat-Sonaco R, Perez A. Factors affecting the spread, diagnosis, and control of African swine fever in the Philippines. Pathogens. (2023) 12:1068. doi: 10.3390/pathogens12081068

23. Portugaliza H. Seroprevalence of African swine fever in pigs for slaughter in Leyte, Philippines. J Adv Vet Anim Res. (2024) 11:65–70. doi: 10.5455/javar.2024.k748

24. Cabodil VA, Portugaliza HP. Understanding the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of stakeholders in reporting African swine fever cases in Abuyog, Leyte, Philippines. J Adv Vet Anim Res. (2025) 12:629–46. doi: 10.5455/javar.2025.l927

25. Wheless SMS, Portugaliza H. Disease recognition and early reporting of suspected African swine fever in Baybay City, Leyte, Philippines: a KAP study. NRCP Res J. (2023) 22:1–1. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-3378203/v1

26. Clarete RL. Regulation by the blind is costly. Business World. (2022). Available online at: https://www.bworldonline.com/opinion/2022/10/09/479354/regulation-by-the-blind-is-costly/ (Accessed September 13, 2025).

27. DA-BAI. Memorandum Circular No. 35, series of 2022: Amended guidelines on the application and renewal of certificate of free status of African swine fever to facilitate unhampered delivery of healthy swine and safe pork and related commodities to target destinations. (2022). Available online at: https://ww2.bai.gov.ph/media/htnld1fr/memorandum-circular-no-35-amended-guidelines-on-the-application-and-renewal-of-certificate-of-free-status-of-african-swine-fever-asf-and-so-on-2022.pdf (Accessed August 1, 2025).

28. Bacongco K. DA urged to establish satellite laboratory to contain ASF in Cotabato. Manila Bulletin. (2024). Available online at: https://mb.com.ph/2024/8/14/da-urged-to-establish-satellite-laboratory-to-contain-asf-in-cotabato (Accessed September 14, 2025).

29. Jorca DL. Presentation of the Veterinary Workforce in the Philippines. World Organization for Animal Health (2021). Available online at: https://rr-asia.woah.org/app/uploads/2021/06/8_introductory-vpp-workshop-member-philippines_jsg_dj_recorded.pdf (Accessed September 14, 2025).

30. PSA. Swine situation report, July-September 2023. Philippine Statistics Authority, Republic of the Philippines. (2025). Available online at: https://psa.gov.ph/content/swine-situation-report-july-september-2023 (Accessed September 26, 2025).

31. Brown A-A, Penrith ML, Fasina FO, Beltran-Alcrudo D. The African swine fever epidemic in West Africa, 1996-2002. Transbound Emerg Dis. (2018) 65:64–76. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12673

32. Lingao JQ, Rofes J, Eusebio M, Barretto-Tesoro G, Herrera M. This little piggy: pig-human entanglement in the Philippines. Int J Histor Archaeol. (2025) 29:40–71. doi: 10.1007/s10761-024-00754-6

33. Lee J-A LM, Lañada EB, More SJ, Cotiw-an BS, Taveros AA. A longitudinal study of growing pigs raised by smallholder farmers in the Philippines. Prev Vet Med. (2005) 70:75–93. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2005.02.016

34. Tabasa CS, Polinar MAN. Exploring the reality of hog raisers in Cebu amidst the African swine fever (ASF) outbreak. Int J Multidiscip Educ Res Innov. (2023) 1:1–12. doi: 10.17613/paq6-2q59

35. Ito S, Kawaguchi N, Bosch J, Aguilar-Vega C, Sánchez-Vizcaíno JM. What can we learn from the five-year African swine fever epidemic in Asia? Front Vet Sci. (2023) 10:1273417. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2023.1273417

36. Ligue-Sabio KDB, Lacaba MFT, Mijares JEC, Murao LAE, Alviola PA. Spatiotemporal patterns and risk factors for African swine fever-affected smallholder pig farms in Davao Region, Southern Philippines. Prev Vet Med. (2025) 239:106495. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2025.106495

37. Ebata A, MacGregor H, Loevinsohn M, Win KS. Why behaviours do not change: structural constraints that influence household decisions to control pig diseases in Myanmar. Prev Vet Med. (2020) 183:105138. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2020.105138

38. Ceruti A, Kobialka RM, Abd El Wahed A, Truyen U. African swine fever: a one health perspective and global challenges. Animals. (2025) 15:928. doi: 10.3390/ani15070928

39. Blacksell SD, Siengsanan-Lamont J, Kamolsiripichaiporn S, Gleeson LJ, Windsor PA. A history of FMD research and control programmes in Southeast Asia: lessons from the past informing the future. Epidemiol Infect. (2019) 147:e171. doi: 10.1017/S0950268819000578

40. Busch F, Haumont C, Penrith M-L, Laddomada A, Dietze K, Globig A, et al. Evidence-based African swine fever policies: do we address virus and host adequately? Front Vet Sci. (2021) 8:637487. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.637487

41. Portugaliza HP, Godinez CJP. A transdisciplinary approach to combatting the threat of African swine fever in Philippine endemic pigs. Ann Trop Res. (2024) 159–166. doi: 10.32945/atr4629.2024

42. Moskalenko L, Schulz K, Mõtus K, Viltrop A. Pigkeepers' knowledge and perceptions regarding African swine fever and the control measures in Estonia. Prev Vet Med. (2022) 208:105717. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2022.105717

43. Matthews Q, Da Silva SJR, Norouzi M, Pena LJ, Pardee K. Adaptive, diverse and de-centralized diagnostics are key to the future of outbreak response. BMC Biol. (2020) 18:153. doi: 10.1186/s12915-020-00891-4

44. Pfeiffer DU, Ho JHP, Bremang A, Kim Y. Compartmentalisation guidelines–African swine fever. Paris, France: World Organization for Animal Health (2021).

45. Stoffel C, Buholzer P, Fanelli A, De Nardi M. Analysis of the drivers of ASF introduction into the officially approved pig compartments in South Africa and implications for the revision of biosecurity standards. Porc Health Manag. (2022) 8:43. doi: 10.1186/s40813-022-00286-7

46. Woonwong Y, Do Tien D, Thanawongnuwech R. The future of the pig industry after the introduction of African swine fever into Asia. Anim Front. (2020) 10:30–7. doi: 10.1093/af/vfaa037

Keywords: animal disease control, African swine fever (ASF), culling policy, depopulation policy, livestock policy, Philippines, rural livelihoods

Citation: Portugaliza HP (2025) Local ASF challenges: the Philippine perspective on ASF stamping-out policy. Front. Vet. Sci. 12:1691490. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2025.1691490

Received: 23 August 2025; Accepted: 29 September 2025;

Published: 15 October 2025.

Edited by:

Hans-Hermann Thulke, Helmholtz Association of German Research Centres (HZ), GermanyReviewed by:

Gustavo Machado, North Carolina State University, United StatesHeinzpeter Schwermer, Federal Food Safety and Veterinary Office (FSVO), Switzerland

Copyright © 2025 Portugaliza. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Harvie P. Portugaliza, aHBvcnR1Z2FsaXphQHZzdS5lZHUucGg=

Harvie P. Portugaliza

Harvie P. Portugaliza