- 1The Conservation of Endangered Wildlife Key Laboratory of Sichuan Province, Chengdu Research Base of Giant Panda Breeding, Chengdu, Sichuan, China

- 2Administration of Daxiangling Nature Reserve, Yaan, Sichuan, China

Understanding physiological adaptations of endangered giant pandas to seasonal changes is critical for improving conservation efforts, yet integrated analyses of blood parameters and feeding strategies remain limited. To decode seasonal adaptation mechanisms, we analyzed 36 monthly blood samples from 3 female pre-released training pandas alongside bamboo components across winter–spring and summer-autumn. Results showed significantly higher lymphocyte counts and urea levels, but lower serum aspartate aminotransferase, serum alkaline phosphatase, glucose and lipase in summer-autumn. Correspondingly, pandas consumed significantly more hemicellulose, crude ash, crude protein and minerals (e.g., potassium, calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, manganese, chromium, copper and zinc) in summer and autumn, while greater intake of starch, lignin, cadmium in winter–spring, reflecting a shift from stems to leaves. Key blood parameters correlated with bamboo component intake. These findings indicate a nutrient-driven strategy favoring anabolic metabolism in resource-rich seasons, providing physiological thresholds for improved conservation and release programs.

Introduction

The giant panda, as a flagship species for global biodiversity conservation, human activities during the last glacial period of the Quaternary period and the Holocene epoch have caused the giant panda population to collapse severely, leading to its endangered status (1). To date, with the establishment of nature reserves, both the population of wild giant pandas and the area of their habitats in China have shown significant growth (2). Based on the increase in wild giant panda populations, the species has transitioned from endangered to vulnerable status. However, conservation efforts continue to face threats from various diseases, as well as challenges such as small population isolation and extinction risks (3–7). Reintroducing captive giant pandas into the wild is one of the key methods for revitalizing isolated small populations (8). However, the success rate of releasing captive pandas into the wild remains low (8). This is primarily due to their poor adaptability to natural environments and the lack of established, effective long-term monitoring systems (8–14). Research has shown that captive animals have become heavily dependent on favorable captive environments, resulting in low adaptability to wild conditions (15). Research on the adaptability of giant pandas has shown that their maintenance of low energy expenditure is closely associated with characteristics such as reduced activity levels and decreased thyroid hormone levels (16). The giant panda’s diet has become specialized to bamboo as an adaptation to its environment. It seasonally selects specific parts of bamboo, primarily based on nutritional and energy requirements, thereby maximizing the acquisition of sufficient nutrients and energy from its food (17, 18). Therefore, we believe that adaptive assessment holds significant importance for the reintroduction of captive giant pandas into the wild.

Artificial-assisted reintroduction is an effective method for increasing the size and genetic diversity of isolated small populations. This method has been used for American black bears (Ursus thibetanus) in India, sun bears (Helarctos malayanus) in Indonesia, American black bears in New Hampshire (19–24). Based on this method, existing research has demonstrated that after a three-month adaptation period following release, the gut microbiota transformation in giant pandas provides them with more diversified energy acquisition strategies better suited to the wild environment (8). Bi et al. (25) discovered that giant pandas exhibit elevated levels of hemoglobin and hematocrit in their blood as an adaptation to higher environmental altitudes. However, there is currently limited research on the relationship between physiological changes and adaptive responses in giant pandas.

Changes in blood physiological and biochemical indicators are commonly used to assess the health status of animals (26). For healthy animals, their environmental adaptability can be measured by their blood physiological and biochemical levels (25, 27, 28). Relevant studies indicate that blood parameters in giant pandas are influenced by factors such as age, sex, dietary intake, and season (29–32). Research has already been conducted on other wildlife. Whiteman et al. (33) found that polar bears (Ursus maritimus) inhabiting terrestrial habitats exhibited higher total white blood cell counts, neutrophil counts, and monocyte counts compared to ice-dwelling polar bears. No significant differences were observed in lymphocyte, eosinophil, basophil, or globulin levels, indicating a higher risk of infection (33). Sergiel et al. (34) found that brown bears (Ursus arctos) exhibit reduced urea levels and increased creatinine levels during winter, suggesting these serve as physiological indicators of hibernation. Randi et al. (35) found that serum enzyme levels such as aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase decreased in brown bears (Ursus arctos) during hibernation, while triglycerides, cholesterol, and lipase levels increased, reflecting a lipid metabolism pattern during hibernation. However, there is currently no research on the seasonal adaptation of blood indicators in wild giant pandas.

We hypothesize that giant pandas have the ability to adapt to seasonal changes in the environment and climate. The aim of this study is to explore the adaptability of giant pandas to seasonal environmental changes from the perspectives of blood physiological and biochemical levels and feeding strategies. To verify this ability, we focused on pre-released training giant pandas, measuring blood physiological and biochemical indicators and the content of bamboo stem and leaf components consumed during different seasons, and conducting relevant statistical analyses. This research seeks to provide physiological threshold data for optimizing conservation and reintroduction programs.

Materials and methods

Subjects

The subjects of this study were three female adult pre-release training giant pandas (7 years old, n = 2; 9 years old, n = 1), all in good health with no illnesses throughout the year. All three pre-release training giant pandas lived within the adaptation area of the Daxiangling Nature Reserve, where their feeding, drinking, resting, and activities all took place in a natural wild environment.

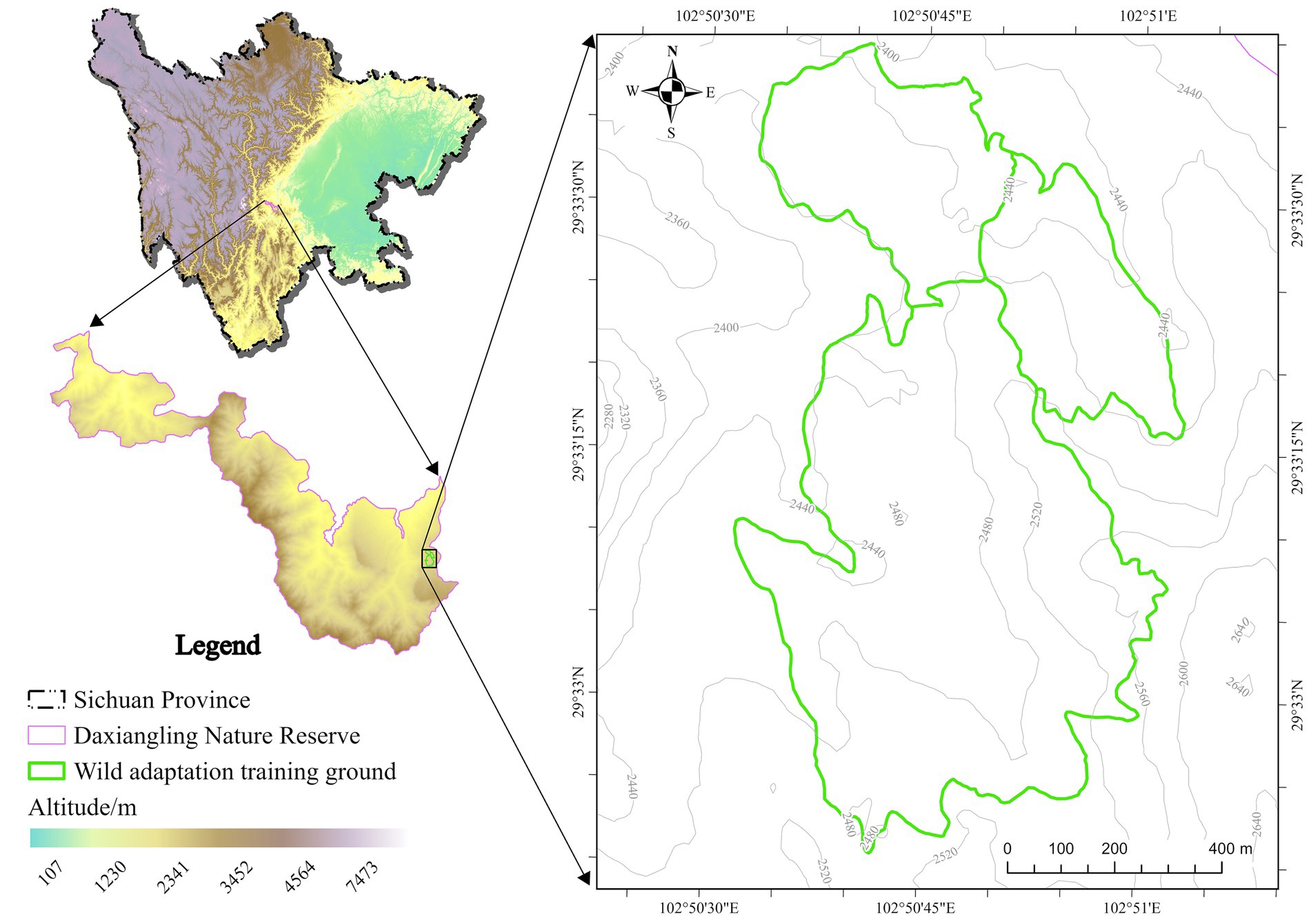

Study site

Three pre-release training giant pandas lived in the wild adaptation area, feeding on naturally growing Arundinaria faberi Rendle. The wild adaptation area is located within the Daxiangling Nature Reserve in the western Sichuan Basin, at an altitude of 2,456–2,495 meters, covering an area of 13.3 to 49.4 hectares, with an average annual temperature of 16 °C and an average relative humidity of 76% (Figure 1).

Sample collection

In this study, all samples were collected from December 2021 to November 2022. The sample collection primarily involved the gathering of overnight fecal samples and bamboo samples for food nutritional component surveys. Owing to the successful implementation of artificial assisted soft-release training (Invention Patent in China: A domestication method of wild release and artificial intervention of giant panda; patent number: ZL 2017 10576548.4), researchers maintained close contact with the giant pandas over extended periods (8). This approach facilitated the immediate collection of fecal samples following defecation. Additionally, under this patent, we utilized Beidou satellite collars (HQAI-M, Global Messenger Technology Co., Ltd., Hubei, China) to collect hourly activity locations of the pandas and track their movements to identify previous activity areas. In this study, collection personnel strictly adhered to the sample collection protocols, wearing disposable surgical masks and polyethylene (PE) gloves.

Utilizing location data from satellite collars fitted on giant pandas, we conducted monthly surveys of their foraging areas, focusing on the areas visited the previous day. Based on feeding traces and patterns, we collected 100 g each of arrow bamboo leaves and culms from the surrounding area, cleaning and placing them in PE tubes. These samples were transported to the laboratory with ice packs and stored at −80 °C in an ultra-low temperature freezer until further nutritional component analysis. As there were no observed instances of the study subjects consuming shoots throughout the year, this study did not involve the collection or compositional analysis of bamboo shoot samples. In addition, on the 5th, 15th, and 25th of each month, we surveyed the pandas’ resting areas from the previous day. We searched for fecal piles containing more than 20 units feces, which are indicative of the pandas’ comprehensive feeding strategy on different parts of the bamboo. These fecal piles were collected entirely into PE bags and transported to the laboratory at ambient temperature for storage (Supplementary Table S1).

Based on the feeding strategies of giant pandas, the seasons are divided into two groups: winter–spring season (December, January–May) and summer-autumn season (June–November).

Blood samples are collected once a month during physical examinations using a non-anesthetic blood collection method. Each giant panda individual was well-trained for blood collection and completed the procedure without anesthesia. Blood collection was conducted using disposable sterile needles for venipuncture. Each panda contributed two types of blood samples, 1 mL blood sample was placed in an EDTA tube for hematological analysis, another 1 mL in a heparin sodium anticoagulant tube for biochemical analysis. Blood samples were centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 10 min and stored at 4 °C and immediately sent for testing and analysis.

Blood physiological and biochemical indicator measurement

The blood samples are then transported to the Blood Testing Center of the People’s Hospital of Yingjing County, Ya’an City, Sichuan Province, within 6 h for routine blood tests and biochemical analysis (10). Blood physiological indicator measurements mainly include white blood cells (WBC), neutrophils (NEU), monocytes (MON), lymphocytes (LYM#), red blood cells (RBC), hemoglobin (HGB), red blood cell hematocrit (HCT), platelets (PLT), and platelet hematocrit (PCT), totaling 9 parameters. Complete hematological analysis was done using the ProCyte Dx automated hematology analyzer (IDEXX Laboratories, Westbrook, ME, United States). Blood biochemical parameter measurements primarily include serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT), serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST), serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP), serum gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT), serum total protein (TP), serum albumin (ALB), serum globulin (GLOB), albumin-to-globulin ratio (A/G), serum urea (UREA), creatinine (CREA), uric acid (UA), blood glucose (GLU), serum triglycerides (TG), serum total cholesterol (TCHOL), serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), serum amylase AMY, serum lipase (LPS), potassium (K), natrium (Na), chlorine (Cl), calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), and phosphorus (P), totaling 23 parameters. Blood biochemical parameters were measured using the FUJI automatic dry chemistry analyzer (DRI-CHEM NX500iVC, FUJIFILM, Tokyo, Japan).

Analysis of the feeding strategy of giant pandas

All the fecal piles samples collected from each individual were manually broken down and spread evenly on ceramic plates. These samples were then placed in an oven and heated at 65 °C for 72 h to remove moisture. Following this, the bamboo leaf and culm residues within the feces were separated manually and weighed individually (36). The monthly intake ratio of bamboo leaves to culms was subsequently calculated based on these measurements (37, 38).

The Bamboo culm and leaf samples were sent to Baihui Organisms Technology Co., Ltd. (Sichuan, China) for nutritional composition analysis. The determination of nutritional components followed established methods from previous studies. Specifically, the methods described by Knott et al. (39) were employed to measure crude fat, starch, crude ash, moisture, crude protein content, tannin, and total phenol. Soluble sugar content was determined following the method outlined by Van Soest et al. (40). The measurement of cellulose, lignin, and hemicellulose was conducted according to the methodology of Kehoe et al. (32). Eight trace elements, including zinc (Zn), copper (Cu), cadmium (Cd), chromium (Cr), lead (Pb), cobalt (Co), molybdenum (Mo), and Titanium (Ti) were analyzed by the Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS), following the approach detailed in the study by Wei et al. (41). Seven macro elements, including potassium (K), natrium (Na), calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), phosphorus (P), ferrum (Fe), and manganese (Mn), was performed using the Inductively Coupled Plasma Atomic Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-AES) according to the methodology described in the study by Wang et al. (42). Calculate the intake of bamboo components based on the measured content of bamboo stems and leaves and their seasonal consumption proportions (Supplementary Table S2).

Statistical analysis

The collected data were analyzed using SPSS 27.0 statistical software. All results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (Mean ± SD). Linear mixed models (LMM) were used for statistical analysis of blood parameters, with season as a fixed blocking factor and panda ID as a random intercept to account for repeated measures across individuals. Fixed-effect tests with 0.01 < p < 0.05 indicated significant differences, and p < 0.01 indicated extremely significant differences. Random-effect variance with p > 0.05 indicated no heterogeneity between groups (43). Independent samples Kruskal–Wallis tests for statistical analysis of bamboo component intake, followed by Dunn’s post hoc test for pairwise comparisons, and applied the false discovery rate (FDR) correction to adjust the p-values obtained from Dunn’s post hoc test. With 0.01 < pFDR < 0.05 indicating statistically significant differences and pFDR < 0.01 indicating extremely significant differences. The Spearman’s correlation coefficient was used for statistical analysis of the correlation between blood indicators and bamboo component intake. The correlation threshold was 0.30 (44). A positive correlation coefficient R indicates a positive correlation, while a negative correlation coefficient R indicates a negative correlation. 0.01 < p < 0.05 indicates a significant correlation, and p < 0.01 indicates a highly significant correlation. A multiple linear regression model was employed to analyze the combined effects of bamboo nutrients on blood indicator levels, identifying the primary nutrients with the most significant influence. These correlations were corrected for multiple testing using the R (v3.6.1) package psych and visualized as heatmaps in GraphPad Prism 9.

Result

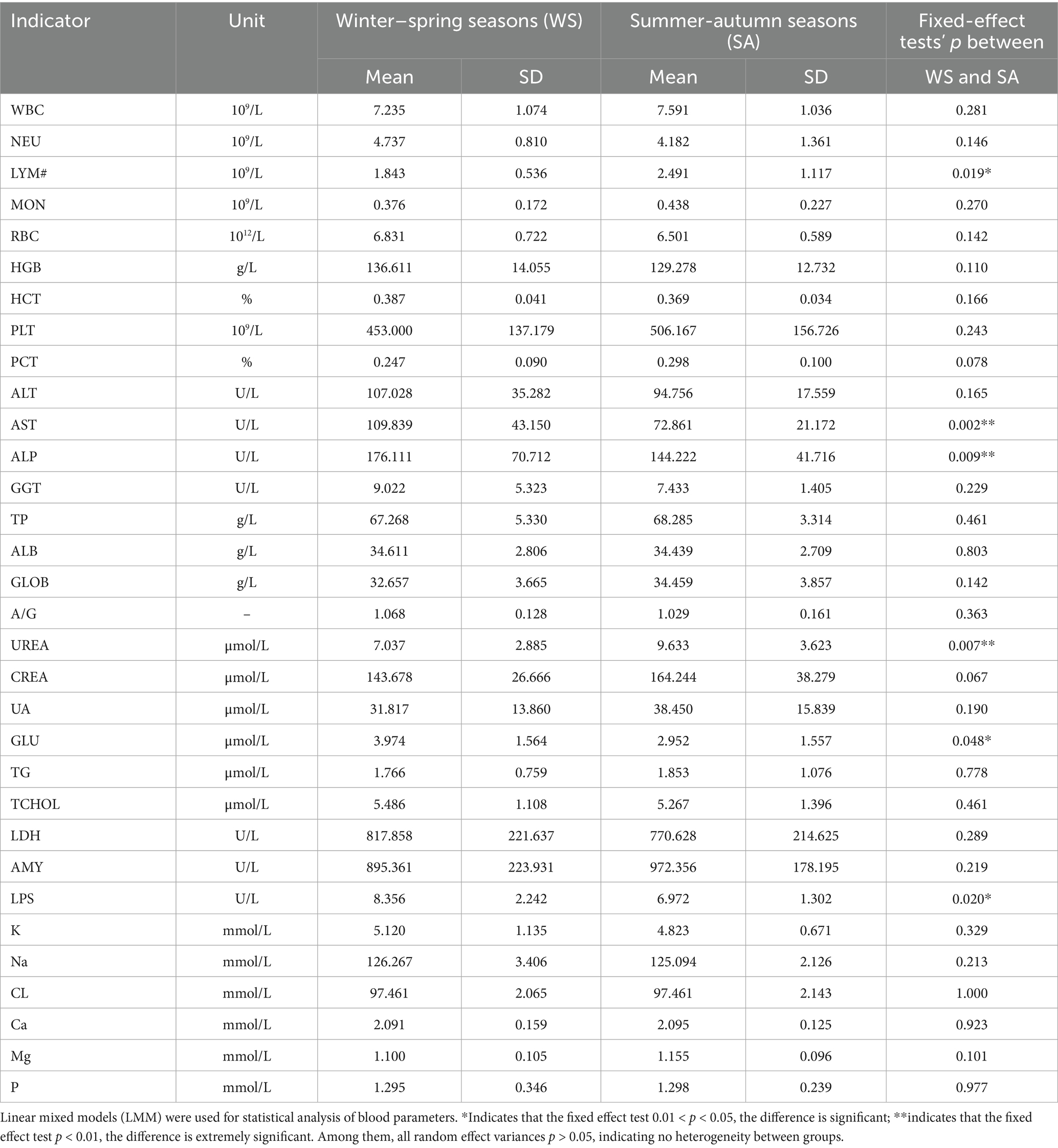

Analysis of seasonal differences in the physiological and biochemical levels of giant panda blood

Seasonal changes have a significant impact on the physiological indicators of giant pandas’ blood (Table 1). LYM# levels are higher in summer-autumn seasons than in winter–spring seasons, the fixed-effect test shows 0.01 < p < 0.05. Seasonal changes significantly affect blood biochemical indicators (Table 1), serum AST and ALP are extremely significantly lower in summer-autumn seasons than in winter–spring seasons, with fixed-effect tests yielding p < 0.01. UREA levels were significantly higher in summer-autumn seasons than in winter–spring seasons, with a fixed-effects test p < 0.01. GLU and LPS levels were significantly lower in summer and autumn seasons than in winter–spring seasons, with a fixed-effects test 0.01 < p < 0.05. Among them, all random effect variances p > 0.05, indicating no heterogeneity between groups.

Table 1. Analysis of differences in blood physiological and biochemical indicators between giant pandas in winter–spring seasons and in summer-autumn seasons.

Analysis of the feeding strategy of giant pandas

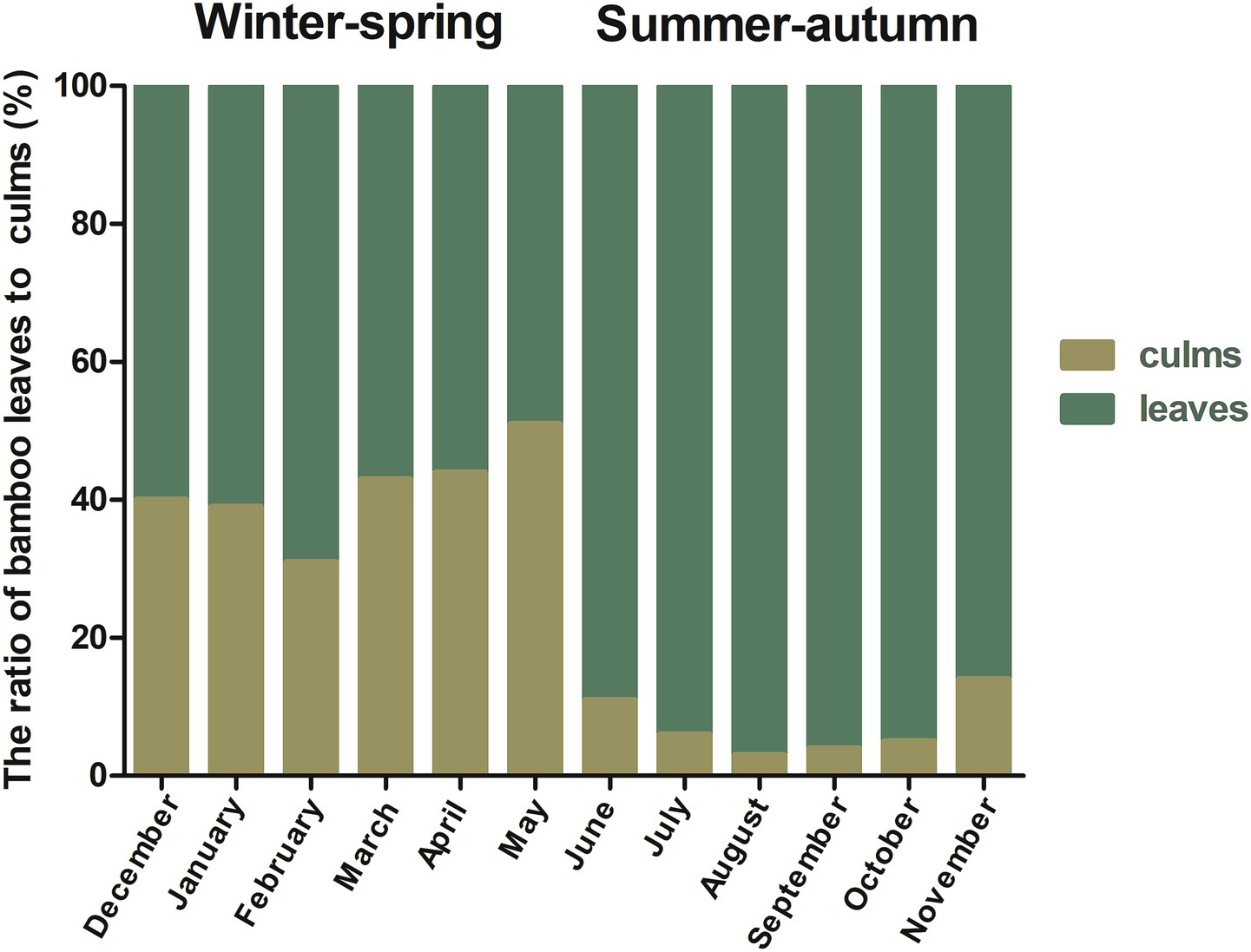

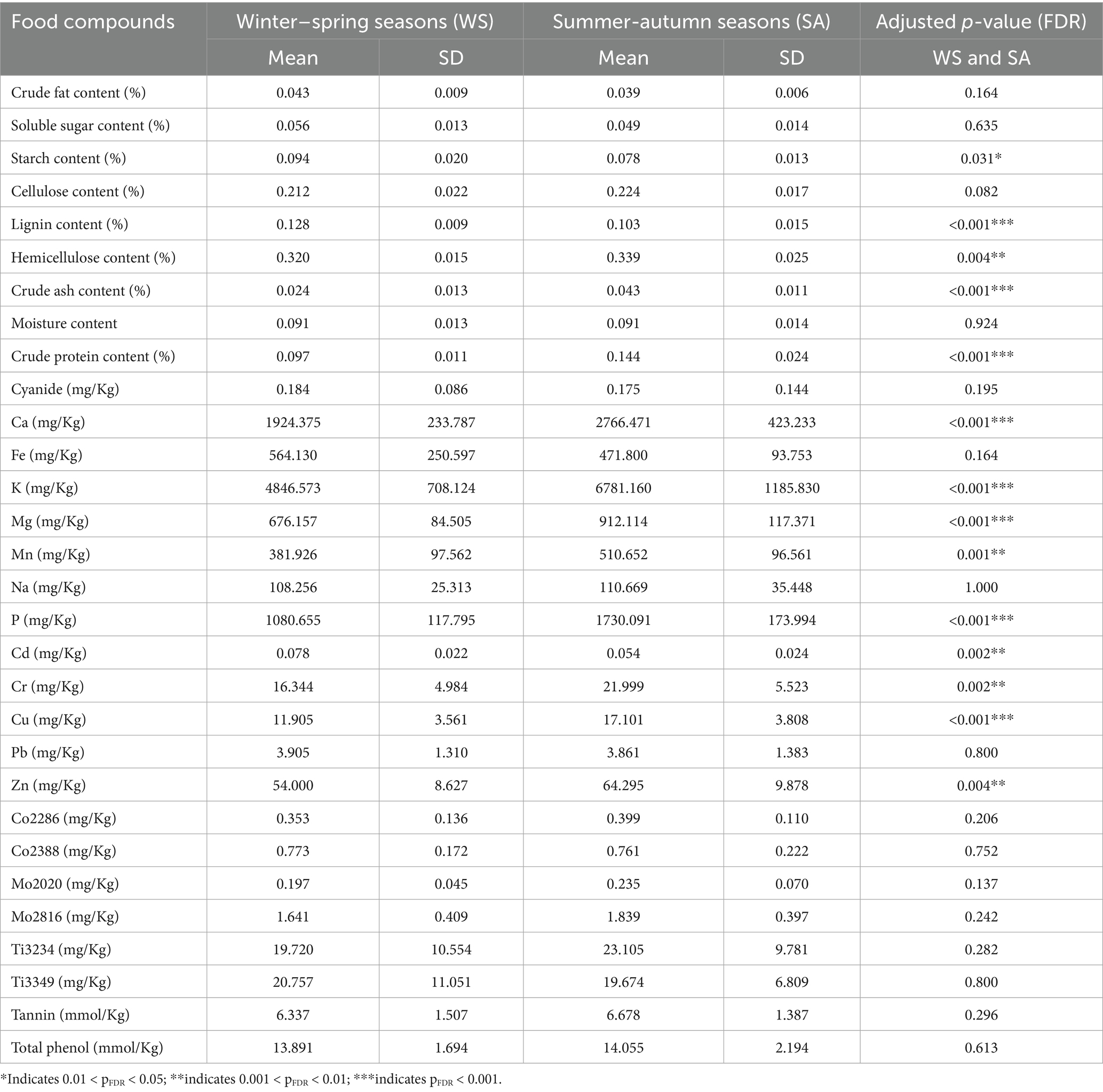

Seasonal changes affect the feeding strategies of giant pandas. In winter–spring, they feed on a mixture of bamboo culms and leaves, while in summer-autumn, they mainly feed on bamboo leaves (Figure 2), which in turn affects their intake of bamboo nutrients and Statistical analysis revealed seasonal variations in the intake of certain nutrients (Table 2). Starch content (pFDR = 0.031) intake was significantly lower in summer-autumn seasons than in winter–spring seasons. Lignin content (pFDR < 0.01) and Cd intake (pFDR = 0.002) were extremely significantly lower in summer-autumn seasons than in winter–spring seasons. In summer-autumn seasons, the intake of hemicellulose content (pFDR = 0.004), crude ash content (pFDR < 0.01), crude protein content (pFDR < 0.01), Ca (pFDR < 0.01), K (pFDR < 0.01), Mg (pFDR < 0.01), Mn (pFDR = 0.001), P (pFDR < 0.01), Cr (pFDR = 0.002), Cu (pFDR < 0.01), and Zn (pFDR = 0.004) intake were extremely significantly higher in summer-autumn seasons than in winter–spring seasons.

Table 2. Analysis of differences in the intake of substances in bamboo consumed by giant pandas during the winter–spring seasons and the summer-autumn seasons.

Correlation analysis between bamboo intake and blood indicators in giant pandas

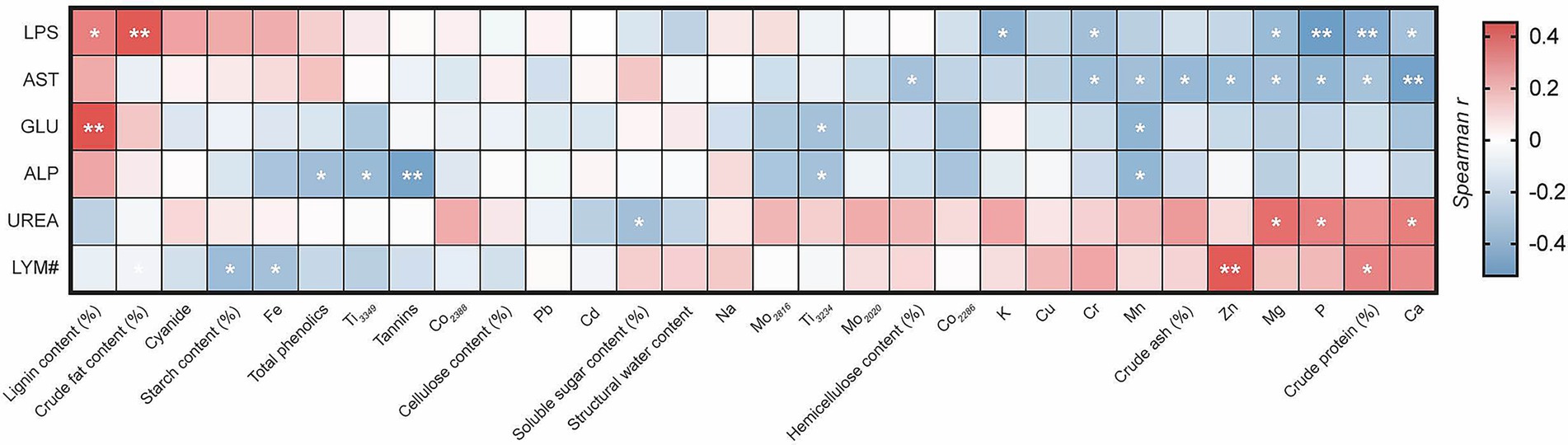

Correlation analysis found that the intake of bamboo substances was correlated with certain physiological and biochemical levels in the blood of giant pandas (Figure 3). There was a significant positive correlation between LYM# and crude protein content intake (R = 0.333, p < 0.05), and a highly significant positive correlation between LYM# and Zn intake (R = 0.439, p < 0.01). There was a significant negative correlation between LYM# and starch content (R = −0.366, p < 0.05), Fe intake (R = −0.332, p < 0.05). AST was significantly negatively correlated with hemicellulose content (R = −0.334, p < 0.05), crude ash content (R = −0.386, p < 0.05), crude protein content (R = −0.330, p < 0.05), Mg (R = −0.350, p < 0.05), Mn (R = −0.348, p < 0.05), P (R = −0.398, p < 0.05), Cr (R = −0.364, p < 0.05), and Zn intake (R = −0.369, p < 0.05), and extremely significant negative correlations with Ca intake (R = −0.505, p < 0.01); ALP levels showed significant negative correlations with Mn (R = −0.397, p < 0.05), Ti3234 (R = −0.335, p < 0.05), Ti3349 (R = −0.375, p < 0.05), and total phenolic intake (R = −0.352, p < 0.05), and a highly significant negative correlation with tannin intake (R = −0.494, p < 0.01). UREA showed a significant negative correlation with soluble sugar content intake (R = −0.345, p < 0.05), and a significant positive correlation with Ca (R = 0.346, p < 0.05), Mg (R = 0.388, p < 0.05), P intake (R = 0.341, p < 0.05). GLU showed a highly significant positive correlation with lignin content intake (R = 0.454, p < 0.01) and a significant negative correlation with Mn (R = −0.410, p < 0.05), Ti3234 intake (R = −0.332, p < 0.05). LPS showed a highly significant positive correlation with crude fat content intake (R = 0.442, p < 0.01), a significant positive correlation with lignin content intake (R = 0.345, p < 0.05), and extremely significant negative correlations with crude protein content (R = −0.448, p < 0.01), P intake (R = −0.524, p < 0.01), and significant negative correlations with Ca (R = −0.336, p < 0.05), K (R = −0.419, p < 0.05), Mg (R = −0.372, p < 0.05), and Cr2835 intake (R = −0.346, p < 0.05).

Figure 3. Correlation analysis heatmap. The images only display blood markers significantly correlated with nutritional components. Red indicates a positive correlation, blue indicates a negative correlation, *indicates significant, and **indicates extremely significant.

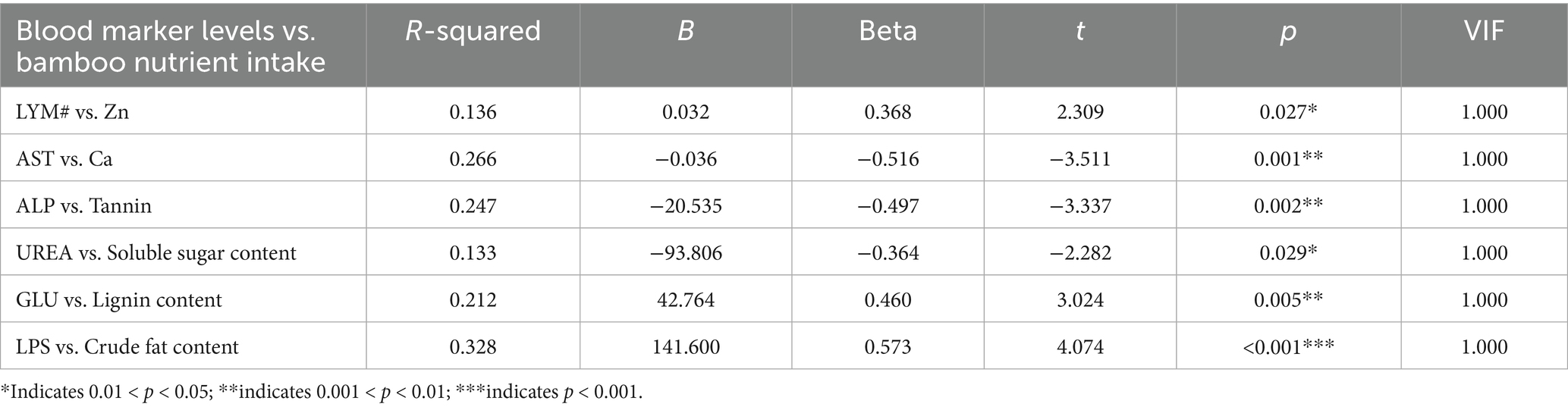

Multivariate linear regression analysis was conducted using bamboo nutrient intake as independent variables and blood indicator levels as dependent variables to identify the primary nutrients exerting the most significant influence (Table 3). Results revealed: dietary Zn intake showed a significant positive correlation with LYM# levels (p = 0.027), Ca intake exhibited a highly significant negative correlation with AST levels (p = 0.001), tannin intake showed a highly significant negative correlation with ALP (p = 0.002), soluble sugar content intake correlated significantly negatively with UREA (p = 0.029), lignin content intake correlated highly significantly positively with GLU (p = 0.005), and crude fat content intake correlated highly significantly positively with LPS (p < 0.001).

Table 3. Multivariate linear regression results of blood marker levels in giant pandas and dietary nutrient intake.

Discussion

Blood physiology and biochemical levels reflect the long-term adaptation of animals to their living environment, reflecting not only their growth and development but also their health status. Normal blood physiological and biochemical levels are relatively stable, and normal fluctuations in these indicators indicate metabolic and physiological changes in the animal’s body. Our study analyzed seasonal variations in physiological and biochemical indicators in the blood of pre-release training giant pandas. Results revealed that during summer-autumn, levels of LYM and CRUA significantly increased, while levels of AST, ALP, GLU, and LPS decreased.

Blood lymphocytes, as immune cells responsible for the animal body’s defense against pathogens, have their resource supply directly influenced by seasonal energy and nutrient intake strategies (45). Our study found that LYM# levels of pre-release training giant pandas were higher during summer and autumn than during winter and spring, which is similar to the findings from Tsessarskaia and Burkovskaya (46). In their study of outdoor-reared dogs, who observed higher LYM# levels in these dogs from May to September compared to November to March of the following year. Similar to findings from studies on terrestrial-phase polar bears by Whiteman et al. (33), their research revealed that LYM# levels in terrestrial-phase polar bears were higher than during the ice-phase, indicating increased pathogen infection risk during the terrestrial phase. In contrast to the findings of Linhua et al. (47) on captive giant pandas, Linhua et al. discovered that age had a highly significant effect on LYM# levels in captive giant pandas, while seasonality showed no significant difference. Therefore, we speculate that the LYM# levels are associated with adapting to seasonal environmental changes and the high risk of pathogen infection during summer-autumn (48–50). Our study also analyzed the correlation between the intake of bamboo constituents and blood indicators, revealing that crude protein and zinc intake during summer-autumn were higher than in winter–spring. These were positively correlated with LYM# levels and negatively correlated with starch intake. Crude protein is a direct source of amino acids required for LYM# proliferation, and Zn is an essential mineral element for lymphocyte differentiation. Increasing the crude protein and Zn content of food provides the material basis for LYM# production in the body (51–53). Starch, as the main source of energy for animal organisms, affects the metabolism of immune cells through blood sugar levels and insulin signaling. A high-starch diet may cause short-term fluctuations in blood sugar levels and inhibit LYM# activity (54). It also indicates that wild giant pandas primarily consume bamboo leaves during summer-autumn, increasing their intake of crude protein and zinc, thereby providing the material basis for LYM# production. In winter–spring, reduced pathogen infection pressure leads to mixed consumption of bamboo stems and leaves, with a relative increase in starch intake. This may suppress the activity of blood LYM#, reducing the maintenance of high lymphocyte counts, primarily to meet the body’s energy demands for adapting to low-temperature environments.

This study found that serum AST, serum ALP, serum LPS, and GLU levels in pre-release training giant pandas were lower during summer-autumn than during winter–spring, while UREA levels were higher during summer-autumn than during winter–spring. AST is a key enzyme in the crosstalk between protein and carbohydrate metabolism, transferring amino groups from amino acids into gluconeogenesis and the citric acid cycle via transamination reactions (55, 56). Our findings contrast with those of Randi et al. (35) in brown bears, they observed decreased serum enzyme levels such as aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and elevated LPS levels in hibernating brown bears. This reflects reduced metabolic function during hibernation, with metabolic patterns shifting toward lipid metabolism. ALP is a class of phospholipase enzymes widely distributed throughout the body’s tissues, catalyzing the hydrolysis of organic phospholipids. Zinc and magnesium serve as essential cofactors for their activity (57, 58). LPS is a key enzyme that breaks down fats and lipids into fatty acids and glycerol, aiding in the maintenance of normal gallbladder function. Its serum levels reflect the intensity of the body’s lipolytic metabolism (59, 60). This finding is consistent with the results of Jiang et al. (61). in captive giant pandas, who observed that LPS levels in captive giant pandas were higher in spring than in other seasons, while ALP levels were lower in autumn than in other seasons. GLU is the body’s most direct source of energy, and its levels are regulated by the dynamic balance of “intake-consumption-storage” (62). Similar to the findings of Yunxiao et al. (63) in cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca mulatta), they observed that blood GLU levels in cynomolgus monkeys exhibited a cyclical fluctuation pattern, with the lowest values occurring in summer, the highest in winter, and intermediate levels in spring and autumn. The production of UREA directly depends on the breakdown of proteins or amino acids. The level of urea in the blood mainly reflects the intensity of protein metabolism and excretion efficiency (64). Similar to findings from Sergiel et al. (34) in brown bears, they observed reduced UREA levels and increased CREA levels in wintering brown bears, suggesting these serve as physiological indicators of hibernation in brown bears. It is speculated that the reason may be that brown bears have a low basal metabolic rate during hibernation, whereas giant pandas do not hibernate. During the winter–spring period, low temperatures and food scarcity drive the body to predominantly adopt catabolic metabolism. Specifically, the elevation of lipase (LPS) levels facilitates the breakdown of stored fat, while increased glucose (GLU) levels guarantee energy supply—effectively meeting the body’s demands for thermogenesis and survival (65–67). During this phase, metabolic activity intensifies; concurrently, enhanced cellular permeability leads to the release of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) into the bloodstream, resulting in relatively higher serum AST and ALP levels compared to those observed in summer and autumn (68). In contrast, the warm, mild summer and autumn seasons are characterized by abundant food availability. During this period, metabolic rates maintain basal levels, thereby imposing minimal metabolic stress on tissue cells. The body then shifts its focus to energy storage and growth: abundant dietary protein is not only broken down to generate energy but also utilized for synthesizing fat reserves, ultimately leading to relatively elevated serum urea (UREA) levels (69, 70).

Based on the results of this study’s bamboo material composition intake analysis, the intake of hemicellulose, crude ash, crude protein, Ca, K, Mg, Mn, P, Cr, Cu, and Zn was higher in summer-autumn than in winter–spring, while the intake of starch, lignin, and Cd was lower in summer-autumn than in winter–spring, Noting that summer-autumn offer a richer variety of nutritious foods. The correlation analysis results of this study indicate that crude protein, Ca, Mg, and P all exhibit negative correlations with serum AST and LPS levels, while showing positive correlations with serum UREA levels. Crude protein from plants is broken down into ammonia by the animal body and converted into urea through the urea cycle. Magnesium (Mg) promotes urea production by activating key enzymes in this cycle (71), while phosphorus (P), as a core component of ATP, provides sufficient ATP for the urea cycle (72). This suggests that higher intake of crude protein, Mg, and P during summer and autumn maintains the body’s urea cycle, resulting in relatively elevated blood urea levels (73). Calcium, acting as an active cofactor for LPS, works with magnesium to maintain cellular homeostasis and antioxidant capacity, while interacting with phosphorus to preserve calcium-phosphorus equilibrium. This reduces mineral deposition and disruptions in lipid metabolism, thereby decreasing cellular release of AST and LPS (74). It also suggests that serum AST and LPS levels are relatively lower in summer and autumn compared to winter and spring, which correlates with the intake of animal nutrients. These nutrients synergistically provide the material foundation required for metabolism and maintain cell membrane integrity, thereby reducing the release of AST and LPS into the bloodstream (75).

The physiological adaptation of pre-release training giant pandas is crucial for successful reintroduction. Currently, their physiological adaptability is primarily reflected in the evolution of their gut microbiome and energy metabolism mechanisms, with few studies examining adaptation from a physiological perspective (76–78). This study investigated the adaptive responses of pre-release training giant pandas to seasonal environmental changes through blood physiological and biochemical parameters and foraging strategies. It revealed that during the wild-release training period, pandas adjusted their foraging strategies to accommodate seasonal variations in the wild environment, which in turn influenced their blood physiological and biochemical levels. These findings provide reference values for health monitoring. Additionally, further operational management protocols will be developed for habitat selection in reintroduction training grounds, monitoring of the reintroduction process, and evaluation of its effectiveness, ensuring that pre-release training giant pandas can adapt to seasonal changes in the wild.

This study has several limitations: (1) the small sample size (36 blood samples from 3 individuals) limits the statistical power and generalizability of our findings. Though the sample size aligns with common practices in endangered species research, small samples may amplify the influence of individual variability or outliers. Future studies should prioritize expanding the number of sampled individuals and ensuring balanced group sizes to validate our observations (8–10). (2) This study standardized the age groups, gender, diet, and living environments of the research subjects, thereby reducing the influence of multiple factors. However, further research is needed to explore the effects across different age groups and genders. (3) Our study suggests that seasonal variations in blood indicators correlate with dietary intake of specific substances. Nevertheless, comprehensive analysis incorporating environmental and meteorological factors remains necessary. In future research, we suggest: (1) while increasing the number of sample donors and distinguishing between gender and age groups, we will conduct in-depth investigations into habitat, climate, and activity intensity to further explore the physiological factors influencing giant pandas’ adaptation to wild environments. (2) Collect blood and fecal samples from study subjects for metabolomics and transcriptomics analysis, employing a multi-omics approach to uncover the mechanisms by which giant pandas adapt to seasonal environmental changes.

Conclusion

This study found that pre-release training giant pandas have developed a nutrition-driven foraging strategy to adapt to seasonal changes in the wild: consuming both bamboo stems and leaves during winter–spring, and feeding primarily on bamboo leaves during summer-autumn. During summer-autumn, abundant food resources increase intake of nutrients such as hemicellulose, crude protein, Ca, Mg, P, and Zn. This strategy tends to promote anabolic metabolism, resulting in relatively elevated blood urea levels. During winter–spring when food resources are scarce, this strategy tends to promote catabolism, regulating elevated levels of blood AST, LPS, and GLU to ensure energy supply and cold resistance. These findings indicate a nutrient-driven strategy favoring anabolic metabolism in resource-rich seasons, providing physiological thresholds for improved conservation and release programs.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Chengdu Research Base of Giant Panda Breeding. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

JG: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. XYu: Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. DQ: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. RH: Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. LZ: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. GL: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. FF: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. WB: Data curation, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. FX: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. JL: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. CH: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. ZL: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. YZ: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. CC: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. WW: Project administration, Writing – review & editing. PL: Resources, Writing – review & editing. XYa: Resources, Writing – review & editing. MZ: Resources, Writing – review & editing. HH: Resources, Writing – review & editing. HY: Resources, Writing – review & editing. RM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Funding was provided and supported by Chengdu Giant Panda Breeding Research Foundation (CPB2025-A11; 2024CPB-Y05; CAZG2025C13) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 32400405; 32570615), Sichuan Science and Technology Program (No. 2024NSFSC0023).

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff at the Yingjing Management Station of Giant Panda National Park and Meishan Branch of Giant Panda National Park for assisting in the collection of samples. We are also deeply indebted to AquaVivid Biotech for their significant contributions to data analysis, which greatly enhanced the rigor of this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fvets.2025.1703367/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Wei, BZML. Genetic viability and population history of the Giant Panda, putting an end to the “Evolutionary Dead End?”. Mol Biol Evol. (2007) 24:1801–10. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm099

2. Huang, Q, Fei, Y, Yang, H, Gu, X, and Songer, M. Giant panda National Park, a step towards streamlining protected areas and cohesive conservation management in China. Glob Ecol Conserv. (2020) 22:e947. doi: 10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e00947

3. Yipeng, J, Xinke, Z, Yisheng, M, Yanchao, Q, Xiaobin, L, Kaihui, Z, et al. Canine distemper viral infection threatens the giant panda population in China. Oncotarget. (2017) 8:113910–9. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.23042

4. Jin, Y, Chen, S, Chao, Y, Pu, T, Xu, H, Liu, X, et al. Dental abnormalities of eight wild Qinling giant pandas (Ailuropoda melanoleuca qinlingensis), Shaanxi province, China. J Wildl Dis. (2015) 51:849–59. doi: 10.7589/2014-12-289

5. Swaisgood, RR, Wang, D, and Wei, F. Panda downlisted but not out of the woods. Conserv Lett. (2017) 11:2355. doi: 10.1111/conl.12355

6. Li, J, Karim, MR, Li, J, Zhang, L, and Zhang, L. Review on parasites of wild and captive giant pandas (Ailuropoda melanoleuca): diversity, disease and conservation impact. Int J Parasitol. (2020) 13:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ijppaw.2020.07.007

7. Zhao, S, Zheng, P, Dong, S, Zhan, X, Wu, Q, Guo, X, et al. Whole-genome sequencing of giant pandas provides insights into demographic history and local adaptation. Nat Genet. (2013) 45:67–71. doi: 10.1038/ng.2494

8. Ma, R, Yu, X, Bi, W, Liu, J, Li, Z, Hou, R, et al. Adaptive changes in the intestinal microbiota of giant pandas following reintroduction. Sci Rep. (2025) 15:31014. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-16136-9

9. Ma, R, Yu, X, Huang, C, Xue, F, Hou, R, Wu, W, et al. Reintroduction training is instrumental in restoring the oral microbiota of giant pandas from “captivity” to “wildness”. BMC Microbiol. (2025) 25:391. doi: 10.1186/s12866-025-04084-3

10. Ma, R, Yue, C, Gu, J, Wu, W, Hou, R, Huang, W, et al. Efficacy of azithromycin combined with compounded atovaquone in treating babesiosis in giant pandas. Parasit Vectors. (2024) 17:531. doi: 10.1186/s13071-024-06615-9

11. Yang, Z, Gu, X, Nie, Y, Huang, F, Huang, Y, Dai, Q, et al. Reintroduction of the giant panda into the wild: a good start suggests a bright future. Biol Conserv. (2018) 217:181–6. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2017.08.012

12. Yao, R, Xu, L, Hu, T, Chen, H, Qi, D, Yang, Z, et al. The “wildness” of the giant panda gut microbiome and its relevance to effective translocation. Glob Ecol Conserv. (2019) 18:644. doi: 10.1016/j.gecco.2019.e00644

13. Jule, KR, Leaver, LA, and Lea, SEG. The effects of captive experience on reintroduction survival in carnivores: a review and analysis. Biol Conserv. (2008) 141:355–63. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2007.11.007

14. Mathews, F, Orros, M, Mclaren, G, Gelling, M, and Foster, R. Keeping fit on the ark: assessing the suitability of captive-bred animals for release. Biol Conserv. (2005) 4:569–77. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2004.06.007

15. Waples, RS, Teel, DJ, Myers, JM, and Marshall, AR. LIFE-history divergence in Chinook salmon: historic contingency and parallel evolution. Evolution. (2004) 58:386–403. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2004.tb01654.x

16. Nie, Y, Speakman, JR, Wu, Q, Zhang, C, Hu, Y, Xia, M, et al. Exceptionally low daily energy expenditure in the bamboo-eating giant panda. Science. (2015) 349:171–4. doi: 10.1126/science.aab2413

17. Wei, F, Feng, Z, Wang, Z, and Li, M. Feeding strategy and resource partitioning between giant and red pandas. Mammalia. (1999) 63:417–30. doi: 10.1515/mamm.1999.63.4.417

18. Zhengsheng, X, Wenping, Z, Linghua, W, Rong, H, Menghui, Z, Lisong, F, et al. The bamboo-eating giant panda harbors a carnivore-like gut microbiota, with excessive seasonal variations. MBio. (2015) 6:e15–22. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00022-15

19. F, G. Conservation threats facing sun bears, Helarctos malayanus, in Indonesia and experiences with sun bear re-introductions in East Kalimantan, Indonesia In: Rehabilitation and release of bears. eds Kolter, L, van Dijk, J Garten Köln: Hundt Drek. (2005). 35–42.

20. Komnenou, AT, Karamanlidis, AA, Kazakos, G, Kyriazis, AP, and Beecham, JJ. First successful hand rearing and release to the wild of two orphan brown bear cubs in Greece. J Hell Vet Med Soc. (2016) 67:163–70. doi: 10.12681/jhvms.15634

21. Beecham, JJ, Hernando, MDG, Karamanlidis, AA, Beausoleil, RA, Burguess, K, Jeong, DH, et al. Management implications for releasing orphaned, captive-reared bears back to the wild. J Wildlife Manage. (2015) 79:1327–36. doi: 10.1002/jwmg.941

22. Kilham, B, and Spotila, JR. Matrilinear hierarchy in the American black bear (Ursus americanus). Integr Zool. (2021) 17:139–55. doi: 10.1111/1749-4877.12583

23. Smith, WE, Pekins, PJ, Timmins, AA, and Kilham, B. Short-term fate of rehabilitated orphan black bears released in New Hampshire. Hum-Wildl Interact. (2016) 10:14. doi: 10.26077/grqp-ty92

24. Kilham, B. The Social Behavior of the American Black Bear (Ursus americanus). Philadelphia: Drexel University (2015).

25. Bi, W, Liu, S, O’Connor, MP, Owens, JR, Valitutto, MT, et al. Hematological and biochemical parameters of giant pandas (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) in captive and semi-natural environments. Conserv Physiol. (2024) 12:d83. doi: 10.1093/conphys/coad083

26. Maceda-Veiga, A, Figuerola, J, Martínez-Silvestre, A, Viscor, G, and Pacheco, M. Inside the Redbox: applications of haematology in wildlife monitoring and ecosystem health assessment. Sci Total Environ. (2015) 514:322–32. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.02.004

27. Wintle, NJP, Martin-Wintle, MS, Zhou, X, and Zhang, H. Blood lead levels in captive giant pandas. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. (2018) 100:59–63. doi: 10.1007/s00128-017-2221-4

28. Ricklefs, RE, and Wikelski, M. The physiology/life-history nexus. Trends Ecol Evol. (2002) 17:462–8. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(02)02578-8

29. Du, L, Qin, L, Fujun, S, Zhenxin, F, Rong, H, Bisong, Y, et al. Transcriptome analysis reveals immune-related gene expression changes with age in giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) blood. Aging. (2019) 11:249–62. doi: 10.18632/aging.101747

30. Xiaoyu, H, Qingyuan, O, Mingxia, R, Bo, Z, Linhua, D, Shenqiang, H, et al. The immune and metabolic changes with age in giant panda blood by combined transcriptome and DNA methylation analysis. Aging. (2020) 12:21777–97. doi: 10.18632/aging.103990

31. Haibo, S, Caiwu, L, Ming, H, Yan, H, Jing, W, Minglei, W, et al. Immune profiles of male giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) during the breeding season. BMC Genomics. (2021) 22:143. doi: 10.1186/s12864-021-07456-x

32. Kehoe, SP, Nicole, S I, Frasca, S, Stokol, T, Wang, C, Leach, KS, et al. Leukocyte and platelet characteristics of the giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca): morphological, cytochemical, and ultrastructural features. Front Vet Sci. (2020) 7:156. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2020.00156

33. Whiteman, JP, Harlow, HJ, Durner, GM, Regehr, EV, Amstrup, SC, and Ben-David, M. Heightened immune system function in polar bears using terrestrial habitats. Physiol Biocheml Zool. (2019) 92:1–11. doi: 10.1086/698996

34. Sergiel, A, Bednarski, M, Maślak, R, Piasecki, T, and Huber, D. Winter blood values of selected parameters in a group of non-hibernating captive brown bears (Ursus arctos). Pol J Vet Sci. (2015) 18:885–8. doi: 10.1515/pjvs-2015-0116

35. Randi, GA, Evans, AL, Åsa, F, Bertelsen, MF, Stéphane, B, and Arnemo, JM. Seasonal variation in haematological and biochemical variables in free-ranging subadult brown bears (Ursus arctos) in Sweden. BMC Vet Res. (2015) 11:301. doi: 10.1186/s12917-015-0615-2

36. Smart, A, Schacht, WH, and Moser, LE. Predicting leaf/stem ratio and nutritive value in grazed and nongrazed big bluestem. Agron J. (2001) 93:1243–9. doi: 10.2134/agronj2001.1243

37. Ying, Z, Han, H, Yihua, G, Shibu, Q, Minghua, C, Lan, Q, et al. Feeding habits and foraging patch selection strategy of the giant panda in the Meigu Dafengding National Nature Reserve, Sichuan Province, China. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. (2023) 30:49125–35. doi: 10.1007/S11356-023-25769-0

38. Schaller, GB. Giant pandas:Biology and conservation. Oakland: University of California Press (2004).

39. Knott, KK, Christian, AL, Falcone, JF, Vance, CK, Bauer, LL, Fahey, GC, et al. Phenological changes in bamboo carbohydrates explain the preference for culm over leaves by giant pandas (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) during spring. PLoS One. (2017) 12:e177582. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177582

40. van Soest, PJ, Robertson, J, Lewis, BA, Van Soest, PJ, Vondervoort, P, Robertson, B, et al. Symposium: carbohydrate methodology, metabolism, and nutritional implications in dairy cattle. J Dairy Sci. (1991) 74:3583–97. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(91)78551-2

41. Wei, J, Shasha, Y, Qingqing, H, Ping, L, Mingxia, F, and Jiang, Z. Giant panda microhabitat study in the Daxiangling Niba Mountain corridor. Biology. (2023) 12:165. doi: 10.3390/biology12020165

42. Wang, Y, Ma, QC, Xu, HN, Feng, K, and Tang, Y. ICP-AES determination of mineral elements in five edible seeds after microwave assisted digestion. Adv Mater Res. (2014) 2951:827–30. doi: 10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.881-883.827

43. Benjamin, DJ, Berger, JO, Johannesson, M, Nosek, BA, Wagenmakers, E-J, Berk, R, et al. Redefine statistical significance. Nat Hum Behav. (2018) 2:6–10. doi: 10.1038/s41562-017-0189-z

44. Spearman, C. The proof and measurement of association between two things. Int J Epidemiol. (2010) 39:1137–50. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq191

45. Jian, T, Duan, N, Abdul, WJ, Anthony, CD, Veronica, PG, Jemma, T, et al. Dietary carbohydrate, particularly glucose, drives B cell lymphopoiesis and function. iScience. (2021) 24:102835. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2021.102835

46. Tsessarskaia, TP, and Burkovskaya, TE. Seasonal changeability in the leukocytic composition of blood in dogs. Biull Eksp Biol Med. (1976) 82:1174–6.

47. Linhua, D, Yan, C, Rongping, W, Chengdong, W, Shan, H, Ming, WEI, et al. Seasonal changes of physiological and blood indices of captive giant panda. Acta Theriologica Sinica. (2020) 40:398–406. doi: 10.16829/j.slxb.150347

48. Xueyang, F, Rui, M, Changjuan, Y, Jiabin, L, Bisong, Y, Wanjing, Y, et al. A snapshot of climate drivers and temporal variation of Ixodes ovatus abundance from a giant panda living in the wild. Int J Parasitol Parasites Wildl. (2023) 20:162–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijppaw.2023.02.005

49. Rui, M, Min, Z, Haoning, W, Rong, H, Kailin, Q, Yu, Q, et al. Virome of giant panda-infesting ticks reveals novel bunyaviruses and other viruses that are genetically close to those from giant pandas. Microbiol Spectr. (2022) 10:e203422. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.02034-22

50. Ma, R, Shi, Y, Wu, W, Huang, C, Xue, F, Hou, R, et al. The bacterial diversity and potential pathogenic risks of giant panda-infesting ticks. Microbiol Spectr. (2025) 13:e219724. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.02197-24

51. Mousa, MA, Asman, AS, Ali, RMJ, Sayed, RKA, Majrashi, KA, and Fakiha, KG. Impacts of dietary lysine and crude protein on performance, hepatic and renal functions, biochemical parameters, and Histomorphology of small intestine, liver, and kidney in broiler chickens. Vet Sci. (2023) 10:98. doi: 10.3390/vetsci10020098

52. Lastra, MD, Pastelin, R, Camacho, A, Monroy, B, and Aguilar, AE. Zinc intervention on macrophages and lymphocytes response. J Trace Elem Med Biol. (2001) 15:5–10. doi: 10.1016/S0946-672X(01)80019-5

53. Berger, NA. Characterization of lymphocyte transformation induced by zinc ions. J Cell Biol. (1974) 61:45–55.

54. Xie, Y, Shao, X, Zhang, P, Zhang, H, Yu, J, Yao, X, et al. High starch induces hematological variations, metabolic changes, oxidative stress, inflammatory responses, and histopathological lesions in largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides). Meta. (2024) 14:236. doi: 10.3390/metabo14040236

55. Nelson, D. L. C. M. Lehninger principles of biochemistry (7th). New York: W. H. Freeman and Company. (2017), 704–712.

56. Takashi, M. Alterations of hepatic gluconeogenesis and amino acid metabolism in CTRP3-deficient mice. Mol Biol Rep. (2021) 49:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s11033-021-06969-8

57. Konstantinos, M, Chagigia, M, and Etienne, C. Alkaline phosphatases: biochemistry, functions, and measurement. Calcif Tissue Int. (2022) 112:233–42. doi: 10.1007/s00223-022-01048-x

58. Elarabany, N. A comparative study of some haematological and biochemical parameters between two species from the Anatidae family within migration season. J Basic Appl Zool. (2018) 79:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s41936-018-0044-4

59. Shivam,, Rai, D, Patel, N, Shahane, S, and Mishra, U. Lipases: sources, production, purification, and applications. Recent Pat Biotechnol. (2019) 13:45–56. doi: 10.2174/1872208312666181029093333

60. Park, J, and Jeon, M. SA25 diagnostic test accuracy of serum amylase and lipase for diagnosing acute pancreatitis: a meta-analysis. Value Health. (2024) 27:S400. doi: 10.1016/J.JVAL.2024.03.1872

61. Jiang, R, Zhang, X, Xia, M, Zhao, S, Wang, Y, Pu, T, et al. Effects of age and season on blood parameters of captive Giant pandas: a pilot study. Animals. (2023) 13:3023. doi: 10.3390/ani13193023

62. Chunbo, Z, Tianyu, Z, Yuanyuan, L, Xianfeng, L, Xiaopeng, Y, Linlin, L, et al. The hepatic AMPK-TET1-SIRT1 axis regulates glucose homeostasis. eLife. (2021) 10. doi: 10.7554/eLife.70672

63. Yunxiao, S, Yanchun, Z, Fang, RJJ, Lisha, J, Xiaoming, L, and Libiao, Z. Association of plasma glucose in cynomolgus monkeys withseasonal temperature variation. Chin J Comp Med. (2019) 29:58–62. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1671-7856.2019.05.009

64. Salazar, JH. Overview of urea and creatinine. Lab Med. (2014) 45:e19-e20. doi: 10.1309/LM920SBNZPJRJGUT

65. Teng, T, Guodong, S, Hongwei, D, Xin, S, Guangdong, B, Baoming, S, et al. Characteristics of glucose and lipid metabolism and the interaction between gut microbiota and colonic mucosal immunity in pigs during cold exposure. J Anim Sci Biotechno. (2023) 14:84. doi: 10.1186/s40104-023-00886-5

66. Mouisel, E, Bodon, A, Noll, C, Sourdy, SC, Marques, MA, Flores, RF, et al. Cold-induced thermogenesis requires neutral-lipase-mediated intracellular lipolysis in brown adipocytes. Cell Metab. (2024) 37:429–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2024.10.018

67. Cutler, HB, Rogg, SJ, Thillainadesan, S, Cooke, KC, Masson, SWC, et al. Cold exposure stimulates cross-tissue metabolic rewiring to fuel glucose-dependent thermogenesis in brown adipose tissue. Sci Adv. (2025) 11:t7369. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adt7369

68. Liu, A, Duan, G, Yang, L, Hu, Y, Zhou, H, and Wang, H. Low-temperature stress-induced hepatic injury in Darkbarbel catfish (Pelteobagrus vachelli): mediated by gut–liver Axis dysregulation. Antioxidants. (2025) 14:762. doi: 10.3390/antiox14070762

69. Xiaoshi, W, Hao, W, Zixiang, W, Jinpeng, Z, Weijie, W, Junhong, W, et al. Rumen-protected lysine supplementation improved amino acid balance, nitrogen utilization and altered hindgut microbiota of dairy cows. Anim Nutr. (2023) 15:320–31. doi: 10.1016/j.aninu.2023.08.001

70. Bragagna, L, Maqboul, L, Baron, R, Harloff, M, Spasova, M, Noori, S, et al. A high-protein diet with and without strength training shows no negative effects on oxidative stress markers in older adults. Redox Biol. (2025) 85:103707. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2025.103707

71. Kant, S, Peng, M, and Rothstein, SJ. Genetic regulation by NLA and microRNA827 for maintaining nitrate-dependent phosphate homeostasis in arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. (2011) 7:e1002021. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002021

72. Fisher, RJ, Chen, JC, Sani, BP, Kaplay, SS, and Sanadi, DR. A soluble mitochondrial ATP synthetase complex catalyzing ATP-phosphate and ATP-ADP exchange. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (1971) 68:2181–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.9.2181

73. Belloir, P, Méda, B, Lambert, W, Corrent, E, Juin, H, Lessire, M, et al. Reducing the CP content in broiler feeds: impact on animal performance, meat quality and nitrogen utilization. Animal. (2017) 11:1881–9. doi: 10.1017/S1751731117000660

74. Yaron, JR, Gangaraju, S, Rao, MY, Kong, X, Zhang, L, Su, F, et al. K(+) regulates ca(2+) to drive inflammasome signaling: dynamic visualization of ion flux in live cells. Cell Death Dis. (2015) 6:e1954. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.277

75. Cazzola, R, Porta, MD, Piuri, G, and Maier, JA. Magnesium: a defense line to mitigate inflammation and oxidative stress in adipose tissue. Antioxidants. (2024) 13:893. doi: 10.3390/antiox13080893

76. Guangping, H, Dunwu, Q, Zhisong, Y, Rong, H, Wenyu, S, Fangqing, Z, et al. Gut microbiome as a key monitoring indicator for reintroductions of captive animals. Conserv Biol. (2023) 38:4173. doi: 10.1111/COBI.14173

77. Feilong, D, Chengdong, W, Desheng, L, Yunjuan, P, Linhua, D, Yunxiang, Z, et al. The unique gut microbiome of giant pandas involved in protein metabolism contributes to the host’s dietary adaption to bamboo. Microbiome. (2023) 11:180. doi: 10.1186/S40168-023-01603-0

Keywords: giant panda, foraging strategy, blood physiology and biochemistry, adaptability, reintroduction

Citation: Gu J, Yu X, Qi D, Hou R, Zhang L, Lan G, Feng F, Bi W, Xue F, Liu J, Huang C, Li Z, Zhou Y, Chen C, Wu W, Li P, Yang X, Zhang M, He H, Yang H and Ma R (2025) Giant panda seasonal adaptations in feeding strategies and blood physiology. Front. Vet. Sci. 12:1703367. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2025.1703367

Edited by:

Qinlong Dai, Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine, ChinaReviewed by:

Cheng Li, Chengdu Normal University, ChinaHelin Chen, Southwest Minzu University, China

Copyright © 2025 Gu, Yu, Qi, Hou, Zhang, Lan, Feng, Bi, Xue, Liu, Huang, Li, Zhou, Chen, Wu, Li, Yang, Zhang, He, Yang and Ma. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rui Ma, bWFydWlfcGFuZGFiYXNlQG91dGxvb2suY29t

Jiang Gu

Jiang Gu Xiang Yu1

Xiang Yu1 Dunwu Qi

Dunwu Qi Guanwei Lan

Guanwei Lan Yanshan Zhou

Yanshan Zhou Rui Ma

Rui Ma