- 1LMU Small Animal Clinic, Centre for Clinical Veterinary Medicine, Ludwig-Maximilians-University, Munich, Germany

- 2Diagnostic Centre for Small Animals - Day Clinic, Dresden, Germany

- 3Department of Veterinary Sciences, Ludwig-Maximilians-University, Munich, Germany

Objectives: Interest in feline kinetic gait variables has increased substantially. This study aimed to assess repeatability and intersession reliability of kinetic gait analysis in healthy cats using a pressure-sensitive treadmill.

Methods: Healthy client-owned cats (n = 9) and cats housed at the cattery of the Chair of Animal Nutrition and Dietetics (n = 5), without orthopedic abnormalities based on history, examination, and subjective gait analysis, were enrolled. Cats (mean body weight: 5.2 ± 0.9 kg, age: 4.1 ± 1.7 years) were acclimated to a pressure-sensitive treadmill system (FDM-T-CanidGait®, zebris Medical GmbH, Isny, Germany). Treadmill velocity was adjusted individually for comfortable walking. For data acquisition, cats were placed on the treadmill and repositioned if they jumped off (total duration: 10 min, 5 × 2 min). The first five sequences with six valid gait cycles were selected. Data acquisition was repeated after 2 weeks at the same speed. Average maximal pressure, loaded paw surface, step and stride length, step width, stance and swing phase percentages, hind reach, step-stride ratio, and symmetry indices were calculated. Repeatability was assessed with linear mixed-effects models and intersession reliability with intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs). Reliability was categorized as excellent, good, moderate, or poor, with statistical significance set at a p-value of < 0.05.

Results: Most parameters did not differ significantly between time points, except for the average maximal pressure of the left hindlimb (p = 0.037) and hind reach of both hindlimbs (p ≤ 0.001). ICCs demonstrated good to excellent reliability (0.885–0.988) for all variables, except for symmetry indices (moderate reliability; forelimbs: 0.547, hindlimbs: 0.676).

Conclusion and relevance: A pressure-sensitive treadmill provides repeatable feline gait measurements with good to excellent intersession reliability for most variables and moderate reliability for symmetry indices, offering a reference for future studies. Further studies involving larger cohorts are needed to confirm these results and support broader clinical application.

1 Introduction

During the past two decades, the number of domestic cats in Germany has increased significantly from 6.8 to 15.7 million (2000–2023) (1). In parallel, interest in feline gait and its analysis has also grown. The number of publications on feline gait analysis has more than doubled when comparing the periods 2000–2002 and 2022–2024 (online database searches: PubMed and Google Scholar, search terms: “cat” OR “feline” AND “gait” OR “locomotion” AND “analysis”).

Subjective visual lameness evaluation is known to have high intra- and inter-observer variability in dogs (2, 3) and should also be interpreted with caution in cats. Therefore, objective kinetic and kinematic gait analysis is essential to improve understanding of normal feline gait and to assess the effects of surgical, dietary, or medical interventions in cats with musculoskeletal disorders.

Compared to dogs, objective gait analysis in cats poses greater challenges, as they are often reluctant to walk or may adopt a crouched gait in clinical settings (4–6). However, cat-friendly handling techniques and sufficient acclimatization time can markedly facilitate kinetic gait analysis in cats (5, 6). A recent feline study also introduced deep learning-based kinematic gait analysis that eliminates the need for reflective markers, reducing stress and gait alterations during marker placement in cats (7). The availability of user-friendly pressure-sensitive walkways has increased the feasibility of performing kinetic gait analysis in clinical settings, extending its application beyond research environments. However, as most cats are not leash-trained, controlling de- and acceleration, walking speed, and direction is difficult in cats, complicating feline gait analysis on pressure walkways (8–11).

Although kinetic gait analysis is still rarely applied in clinical practice, its use is increasing in research, particularly in studies on cranial cruciate ligament injuries (12), osteoarthritis (13, 14), outcomes of femoral head and neck ostectomy, total hip replacement (15, 16), and monitoring the post-onychectomy recovery (17).

Pressure-sensitive treadmills and treadmill systems with integrated force platforms offer advantages, such as velocity control and potentially a more consistent linear gait pattern compared to walkway or floor-integrated force platform systems (18). This is crucial, as velocity changes may affect ground reaction forces and temporospatial parameters, mimicking lameness or musculoskeletal abnormalities (2, 19). Moreover, the unlimited “walkway” of a treadmill enables analysis of multiple continuous gait cycles, avoiding disruptions common on floor-based systems (2, 20). This continuity also allows for the observation of fatigue-related asymmetries, as there is no muscular recovery phase between trials (21).

Initial investigations of feline kinetic gait analysis using instrumented treadmill systems have predominantly been confined to experimental non-clinical settings (22–25). To the best of the authors’ knowledge, systematic analyses of ground reaction forces in feline treadmill locomotion have not yet been conducted (26–29).

The objective of this prospective study was to evaluate the reproducibility and reliability of kinetic gait analysis using a commercially available pressure-sensitive treadmill system (CanidGait®, zebris Medical GmbH, Isny, Germany) and to establish baseline reference values for healthy cats.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study population

This prospective study included healthy client-owned cats (n = 9) and cats housed at the cattery of the Chair of Animal Nutrition and Dietetics (n = 5) without orthopedic or neurological abnormalities based on history, general and orthopedic examination, and subjective gait analysis. Inclusion criteria were a minimal body weight of 4 kg and a body condition score (BCS) between 4 and 6 on a 9-point scale (30). All cats were required to walk freely, voluntarily, and comfortably on the treadmill to qualify for inclusion. Exclusion criteria comprised the presence of infectious or immunological diseases, clinically relevant cardiac conditions, or medication with analgesics or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs within 14 days prior to study participation.

2.2 Kinetic gait analysis

Kinetic gait analysis was performed using a pressure-sensitive treadmill system (FDM-T-CanidGait®; sensitivity is 0.5 N/cm2; Animal Analysis Suite RC-2.3.28; zebris Medical GmbH, Isny, Germany) with a sampling frequency of 100 Hz. Two video cameras (WinFDM Software v1.2.2; zebris Medical GmbH, Isny, Germany) synchronized with the treadmill were positioned behind and to the left of the treadmill to document the trials. Prior to data acquisition, each cat was individually acclimated to the testing environment, treadmill, and handlers, and was allowed to roam freely for up to 15 min. During this period, cats were encouraged to explore the room and the treadmill while it was switched off, and they were gradually exposed to the sounds and motion of the treadmill at low speeds. Handlers interacted calmly using toys or treats until the cat displayed a relaxed posture, steady exploration, and voluntary approach toward the treadmill and handlers, which were taken as signs of habituation. Testing conditions differed between client-owned cats and those housed in the cattery of the Chair of Animal Nutrition and Dietetics. Client-owned cats were examined in a 5 × 10 m room at the Animal Mobility Centre of the LMU Small Animal Clinic, whereas the cats at the Chair of Animal Nutrition and Dietetics were assessed in a 3 × 8 m room.

To initiate the trial, a handler placed the cat on a pedestal at the rear of the treadmill, prompting it to cross the motionless treadmill. A second caregiver, positioned behind the pedestal at the front of the treadmill, encouraged the cat to walk over the treadmill using verbal cues, toys, clickers, or food, depending on each cat’s preference. If the cat was comfortable walking across the motionless treadmill, it was then placed directly onto the moving treadmill set at lower velocity. If the cat was unwilling to cross the motionless treadmill, it was placed directly onto the moving treadmill. The treadmill speed was then gradually increased in 0.1 km/h increments until the cat reached a steady-state walking pattern (Figure 1). Steady-state walking was defined as continuous locomotion at a constant treadmill speed, characterized by uniform stride patterns and the absence of interruptions such as acceleration, deceleration, or stopping. A 2-min trial was conducted once a steady gait was achieved. If the cat jumped off during the trial, it was gently returned to the running treadmill, provided it remained comfortable and willing. Each cat completed five trials, contingent on its continued comfort and cooperation. Acclimation time was limited to a maximum of 30 min for each time point, and the total evaluation time did not exceed 60 min. Data acquisition was repeated after 2 weeks at the same velocity. Initial measurements of treadmill velocity were recorded at the first time point, and this velocity was subsequently used to assess treadmill walking at the second time point. Environmental conditions, including lighting and noise levels, were kept as constant as possible throughout the testing. Examinations were performed at normal room temperature under standard artificial lighting, and trials were repeated if unexpected noise or other disturbances occurred.

Figure 1. Cat walking on a pressure-sensitive treadmill system (FDM-T-CanidGait®; sensitivity 0.5 N/cm2; Animal Analysis Suite RC-2.3.28; Zebris, Isny, Germany).

2.3 Data evaluation

All trial sequences were processed using the complementary Animal Analysis Suite RC 2.3.28 software (zebris Medical GmbH, Isny, Germany). Gait cycles were excluded from analysis if apparent de- or acceleration, head movements, or directional changes were observed during video analysis. Small movements of the ears and tail, however, were considered acceptable. A valid trial was defined as a gait sequence of six consecutive steps at each paw. The first five valid sequences were used to calculate the average maximal pressure (% body weight), loaded paw surface (cm2), step and stride length (cm), step width (cm), stance and swing phase percentages (%), hind reach (cm), step-to-stride ratio, symmetry indices, and cadence at the two time points. Symmetry indices (SI) of the average maximum pressure (AMP) were calculated for each cat using the following formula:

The SI was calculated separately for the forelimbs and hindlimbs. A value of less than 9 was considered symmetrical (2).

2.4 Statistical analysis

Repeatability was evaluated using linear mixed-effect regression. Because of repeated measures, generalized linear mixed-effects models with the individual animal as a random effect were applied. Model assumptions were systematically assessed: (1) the normality of residuals with the Shapiro–Wilk normality test, (2) the homogeneity of variances between groups with Bartlett’s test, and (3) the heteroscedasticity (constancy of error variance) with the Breusch–Pagan test. If assumptions were fulfilled, generalized linear mixed effects models (R package - lmer) were applied; if violated, robust linear mixed effects models were applied (R package - robustlmm). Model assumptions were not met for the stance phase, swing phase, double stance, symmetry index, hind reach, and velocity. Linear and robust linear models were compared using the conditional coefficient of determination R2, the marginal coefficient of determination R2, the intraclass-correlation coefficients (ICCs), and root mean square error (RMSE) as performance quality indicators. The model with the most favorable overall fitting power was retained. Contrasts between the categories (time points or limbs) were evaluated after model-fitting using estimated marginal means (R package - emmeans) with Tukey p-value correction for multiple comparisons. Results are presented as means with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI), unless otherwise indicated. In addition, intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) were calculated to assess intersession reliability, providing a complementary, widely recognized metric to confirm the findings and to convey reliability intuitively. Reliability was categorized as excellent (ICC > 0.9), good (0.75–0.9), moderate (0.5–0.75), and poor (< 0.5) (31). Statistical significance was defined as a p-value of < 0.05. Depending on the data distribution, descriptive results are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or as median with interquartile range (IQR). All analyses were performed using R (version 4.5.0, 2025-04-11; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and IBM SPSS Statistics (version 28; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

3 Results

The study population comprised nine European Shorthair cats, two Norwegian Forest Cats, one Bengal, one domestic longhair, and one Maine Coon mix. Three were spayed females, two were intact males, and nine were neutered males. The cats had a mean age of 4.1 ± 1.7 years. Their mean body weight was 5.2 ± 0.9 kg, and the median body condition score was 5 (range 4–6) on a 9-point scale. The cats walked on the treadmill at a mean velocity of 2.4 ± 0.4 km/h.

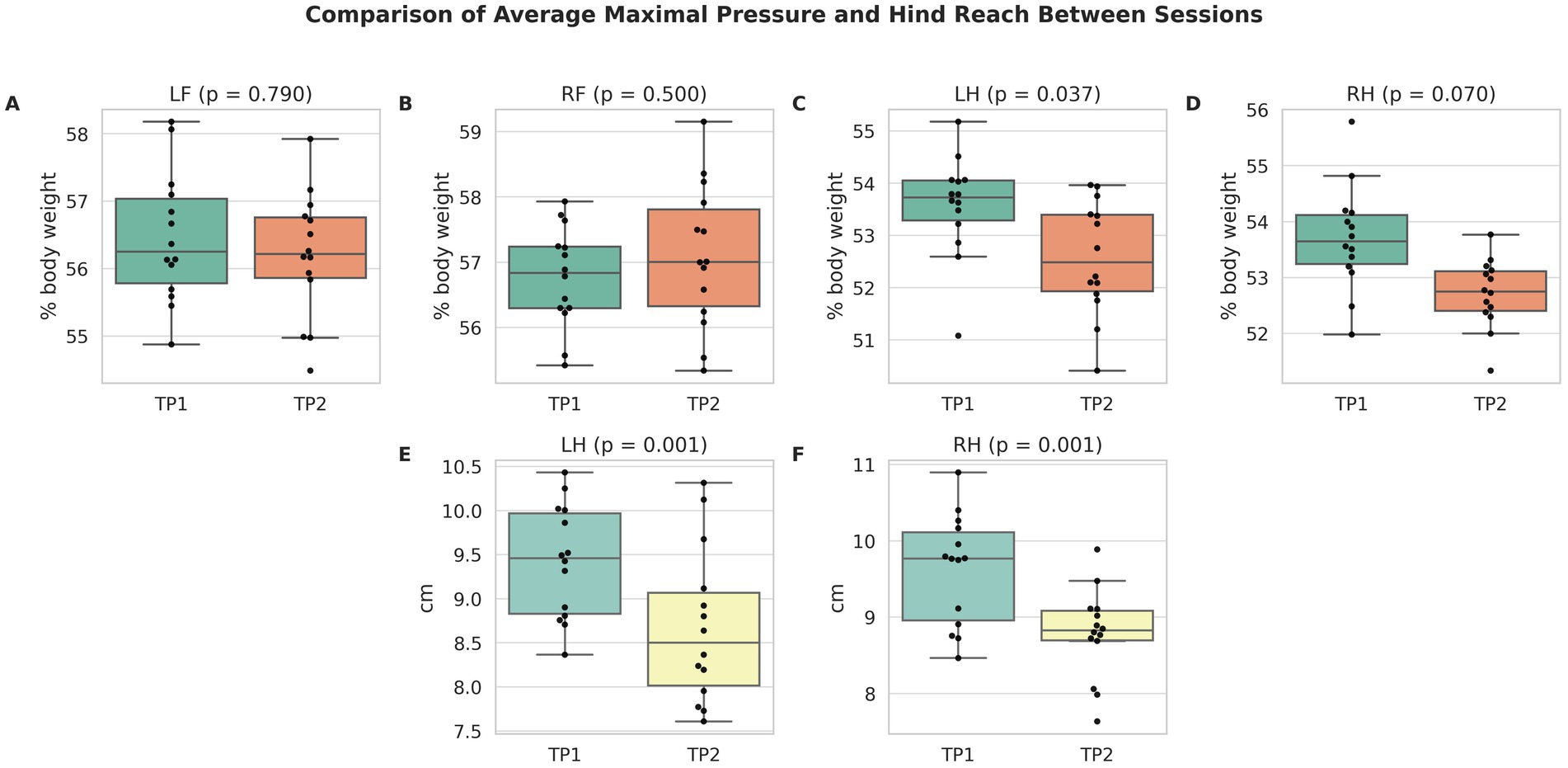

Limb-dependent kinetic and temporospatial parameters at both time points are presented in Table 1. At time point 1, the average maximal pressure was 56.6% of body weight (95% CI, 54.4–58.8) in the left forelimb, 56.9% (95% CI, 54.7–59.1) in the right forelimb, 53.7% (95% CI, 51.5–55.9) in the left hindlimb, and 53.9% (95% CI, 51.7–56.1) in the right hindlimb. The mean loaded paw surface measured approximately 18–19 cm2 across all limbs. Step lengths ranged from 25.6 to 26.6 cm. The stance phase accounted for 59–63% of the gait cycle, while the swing phase accounted for 37–41%. The step-to-stride ratio remained close to 50% in all limbs. Limb-dependent parameters did not differ significantly between time points, except for the average maximal pressure of the left hindlimb (p = 0.037) and hind reach of both hindlimbs (p = 0.001; p < 0.001) (Figure 2).

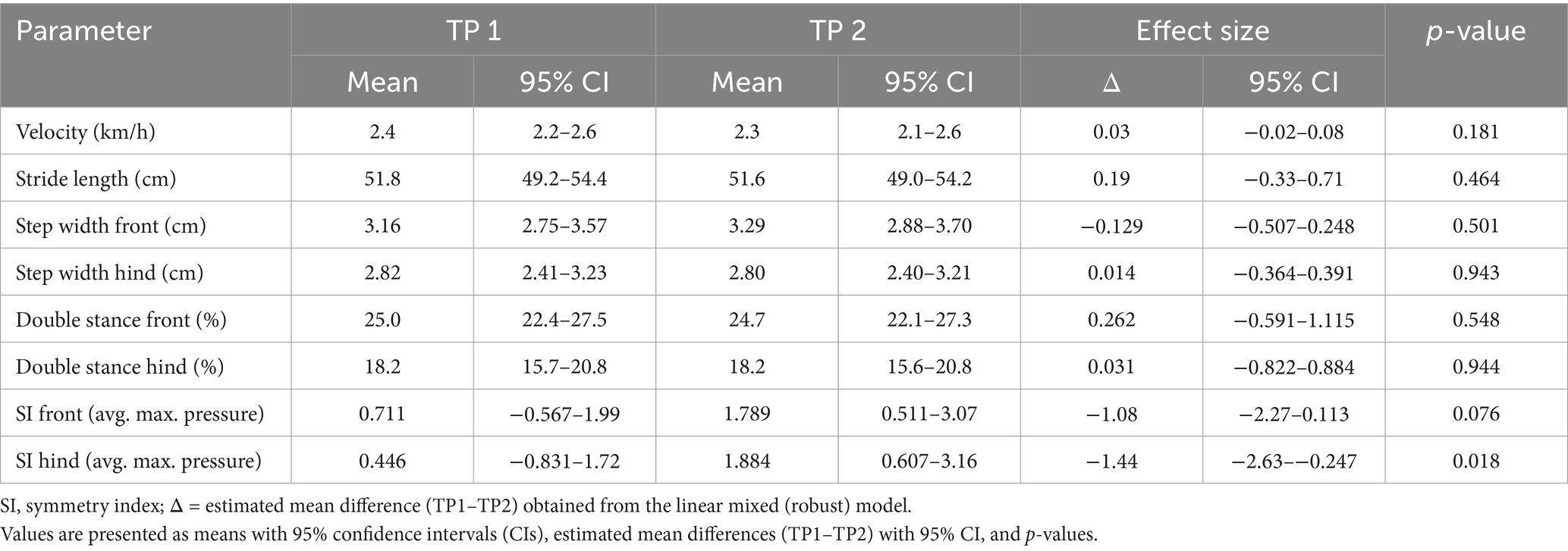

Table 1. Comparison of kinetic and temporospatial parameters between time point 1 (TP1) and time point 2 (TP2).

Figure 2. Comparison of average maximal pressure (A–D) and hind reach (E,F) between time point 1 (TP1) and 2 (TP2) for each limb. Boxplots show medians and interquartile ranges; black dots represent individual cats (n = 14 per session). p-values from mixed-effects models are shown above each pair. Only small differences were observed between time points, confirming high repeatability and intersession reliability.

Temporospatial parameters not assigned to individual limbs at both time points are presented in Table 2. At time point 1, the mean stride length was 51.7 cm (95% CI, 49.2–54.4), and the mean velocity during data acquisition was 2.3–2.4 km/h. Step width was 3.2 cm in the forelimbs and 2.8 cm in the hindlimbs. Double stance constituted 25% of the gait cycle in the forelimbs and 18% in the hindlimbs. Symmetry indices were consistently below 9, indicating symmetrical gait across the study population. These parameters did not differ significantly between time points, except for the hindlimb symmetry index (p = 0.018).

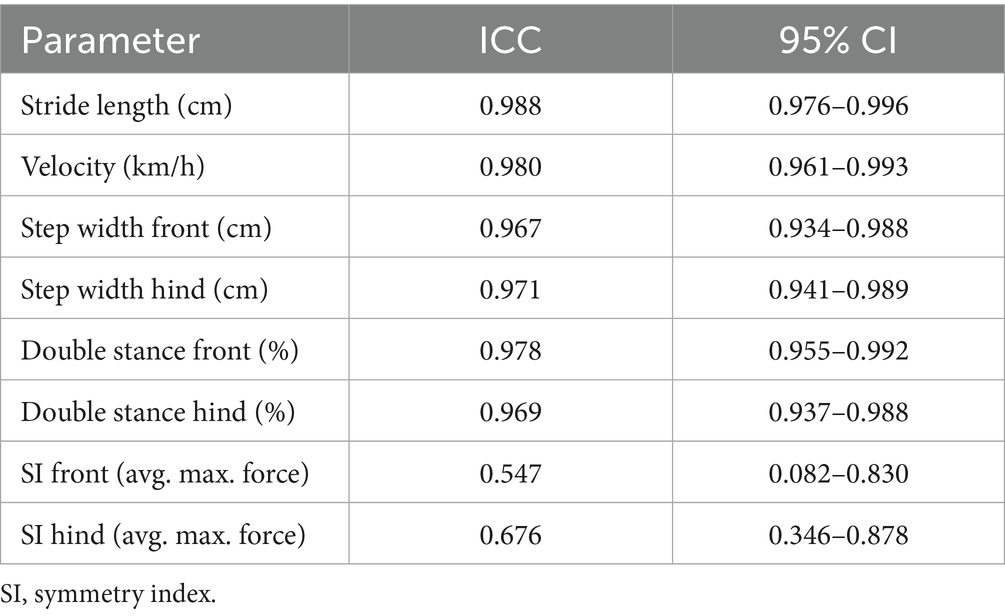

Intraclass correlation coefficients demonstrated good to excellent reliability for all parameters (0.885–0.988), except for the symmetry indices, which showed moderate reliability (ICC: forelimbs: 0.547; hindlimbs: 0.676) (Tables 3, 4).

Table 3. Reliability of kinetic and temporospatial parameters between both time points represented as intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Table 4. Reliability of kinetic and temporospatial parameters between both time points represented as intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

4 Discussion

This study investigated the acquisition of temporospatial parameters and gait patterns in healthy cats using a pressure-sensitive treadmill system. The hypothesis that the data would be repeatable and reliable was largely confirmed, with predominantly good or excellent reliability. These findings support treadmill-based gait analysis as an objective tool for feline gait assessment, particularly in cats reluctant to walk consistently on pressure walkways.

The statistically significant differences detected for the average maximal pressure of the left hindlimb and hind reach of both hindlimbs require cautious interpretation. While statistical significance was achieved, the magnitude of change was small and should not be assumed to indicate clinically meaningful alterations in gait. In recent treadmill studies in healthy dogs, mean absolute differences in peak vertical force between sessions were as low as 1.5 to 5.3% of body weight, with minimum detectable differences of up to 10% of body weight (32). These thresholds suggest that changes below this level likely reflect physiologic variability or habituation rather than true alterations in locomotor function. Reviews on objective gait analysis have similarly emphasized that statistical significance alone is insufficient for clinical interpretation and that effect sizes and minimum detectable differences provide a more meaningful assessment (33, 34). In the present study, the values remained within physiologic ranges, indicating that the observed changes are unlikely to be of clinical relevance. Habituation effects provide a plausible explanation for these findings. Short-term habituation has been documented in equine and human treadmill studies, with normalization of stance durations and kinematic patterns within minutes of exposure (35, 36). In dogs, repeated treadmill examinations revealed habituation effects for stance-phase duration and peak vertical force, manifesting as statistically significant but clinically minor changes between sessions (32). Comparable effects are plausible in cats, which often require longer acclimatization to novel environments and equipment (37). In unfamiliar environments, cats often exhibit stress-related behaviors such as crouching, hiding, or remaining motionless (4–6). These postural and behavioral adaptations can lead to acceleration or deceleration, altered paw loading, and inconsistent stride patterns, all of which may influence kinetic parameters and reduce measurement reliability. Adequate acclimatization is therefore essential to minimize behavioral artifacts and improve the repeatability and intersession reliability of gait data. The consistent reliability observed in the present study likely reflects the effectiveness of the standardized acclimatization protocol applied before data collection. The moderate intraclass correlation coefficients observed for symmetry indices also warrant cautious interpretation. Asymmetries of up to 6% have been described in clinically sound dogs during kinetic gait analysis (38–44). These findings indicate that moderate variability is not necessarily pathological but may reflect inherent biological variation. Symmetry indices should therefore not be interpreted in isolation but considered in conjunction with other kinetic and temporospatial parameters.

An important methodological advantage of treadmill-based gait analysis, in comparison to pressure-sensitive walkways or force plates, is the ability to maintain and precisely control velocity, thereby reducing variability associated with speed (20, 45). Given that variations in locomotor speed can markedly influence the accuracy and reliability of kinetic data, the ability to regulate velocity during treadmill-based assessments serves to reduce this source of variability (2, 18, 19). This control is particularly valuable in cats, where compliance and directional consistency are frequently challenging (5). Pressure-sensitive treadmill systems may therefore represent a robust adjunct to objective locomotor assessment and longitudinal monitoring of treatment outcomes (2, 39, 46–48).

A significant advantage of treadmill-based gait analysis is its capacity to capture changes in gait parameters related to fatigue or adaptation. This is facilitated by the “endless walkway” design, which enables uninterrupted observation of continuous locomotion (21). Unlike force plates or pressure walkways, the cat does not need to be repositioned after each pass, minimizing handling and manipulation and thereby reducing stress during gait assessment (4). Data acquisition and analysis using pressure-sensitive treadmills have also been shown to be considerably faster and more efficient than with pressure walkways, supporting their practical use in clinical and research contexts (20).

These technical and procedural advantages also translate into meaningful benefits for clinical application and research in feline locomotor disorders. The pressure-sensitive treadmill holds considerable translational value for both clinical and research applications. This method enables early detection of subtle gait asymmetries and provides objective quantification of locomotor recovery in cats with orthopedic or neurological disorders. In comparison with pressure walkways and force plates, treadmill-based gait analysis allows continuous steady-state assessment under controlled velocity, thereby improving measurement reliability (18). Although three-dimensional motion capture yields highly detailed kinematic information, the method requires the placement of skin markers and extended preparation time. Most cats do not tolerate markers well and benefit from minimal handling and short examination duration, which limits the clinical feasibility of this technique (7). Treadmill-based kinetic assessment, therefore, represents a practical and standardized tool for diagnostic evaluation and longitudinal follow-up in feline orthopedics and neurology.

A limitation of the present study is the absence of screening radiographs, as enrolled cats underwent only orthopedic examinations and subjective gait analysis. While radiographic imaging would have aided in excluding conditions such as osteoarthritis, when clinical signs are absent, sedation and full radiographic assessment in clinically healthy cats would have violated national animal welfare regulations. Consequently, osteoarthritis cannot be definitively ruled out in the study population, as it may not be detectable through physical examination and gait analysis alone (49–51). To mitigate this potential confounding factor, an age-based inclusion criterion was applied, given that the prevalence of osteoarthritis increases with advancing age (52, 53).

The study population also exhibited a sex bias, with a disproportionately high number of male cats. This imbalance was primarily due to fewer female cats meeting the inclusion criteria, as the minimum body weight threshold imposed by the sensitivity limits of the treadmill sensors excluded lighter individuals. Although this sex imbalance may represent a potential source of bias, prior studies using a pressure-sensitive walkway found no significant differences in temporospatial gait parameters between male and female crossbred cats, except for a longer stride length in males, which was attributed to their greater body size (54). Nevertheless, larger and more balanced samples are required to clarify whether sex influences gait characteristics in treadmill-based analyses. The overrepresentation of European Shorthair cats (9 of 14) in the present study may also limit the generalizability of the findings, although previous studies did not identify breed-related differences between Domestic Shorthair and Maine Coon cats (8).

The limited sample size reflects the exploratory nature of this study, which was intended to validate a novel measurement system for use with cats. Comparable pilot investigations in dogs and other species have likewise been conducted with small cohorts (18, 20). Considering the modest sample size, any generalization of these findings should be interpreted with caution. Future studies, including larger and more diverse cohorts, will be essential to establish reference intervals and to determine the clinical utility of treadmill-based gait analysis in cats with musculoskeletal and neurological diseases.

Walking on a treadmill may influence gait patterns and temporospatial parameters compared with overground locomotion, although published studies remain inconsistent. In dogs, treadmill walking has been associated with shorter stride length, increased stance time, and reduced swing time percentages (55), whereas another study reported only minimal differences, with mean deviations of less than 5% when compared to overground trotting (21). In mice, treadmill use increased stride frequency and decreased stride length but did not otherwise affect overall gait patterns compared to overground walking (56). In human participants, ground reaction forces and gait characteristics during treadmill walking were reported to be qualitatively and quantitatively comparable to overground walking, with no statistically significant differences (57–59). Such discrepancies may arise from species-specific locomotor adaptations, but also from methodological differences. The stationary body position relative to the environment during treadmill locomotion and mechanical inconsistencies in treadmill belt motion are likely sources of variability across studies (18). In a previous study comparing overground walking in dogs and cats, cats exhibited higher peak vertical forces during propulsion as well as greater propulsive force and hindlimb impulse (60). These findings suggest that cats may likewise show species-specific differences in gait parameters when walking on a treadmill compared to overground locomotion. Further research directly comparing treadmill and overground locomotion in cats is warranted to determine whether similar effects occur in this species.

In addition, a systematic assessment of feline acceptance of treadmill walking would be valuable, as acclimatization is critical for reliable measurements but was beyond the scope of the present study and would require a larger cohort.

5 Conclusion

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that a pressure-sensitive treadmill system provides repeatable measurements of feline gait, with good to excellent intersession reliability for most parameters. The statistically significant differences observed for a subset of variables were small, likely reflecting physiological variation or habituation, rather than clinically relevant changes. These findings establish a methodological foundation for future studies investigating gait alterations in cats with orthopedic and neurological disorders. Further studies on diseased feline populations are needed to confirm the clinical applicability and diagnostic value of this method.

Data availability statement

Restrictions apply to the availability of these data due to institutional and ethical regulations. Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and subject to approval.

Ethics statement

The animal studies were approved by Ethical Committee of the Centre of Veterinary Medicine, LMU Munich, Germany. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent was obtained from the owners for the participation of their animals in this study.

Author contributions

DW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. BD: Resources, Writing – review & editing. YZ: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. SL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the staff at the cattery of the Chair of Animal Nutrition and Dietetics for their outstanding support.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

SI, symmetry index; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficients; CI, confidence intervals.

References

1. Statista. (2023). Anzahl der Haustiere nach Tierarten bis 2023. Available online at: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/30157/umfrage/anzahl-der-haustiere-in-deutschen-haushalten-seit-2008/. [Accessed April 16, 2024]

2. Voss, K, Imhof, J, Kaestner, S, and Montavon, P. Force plate gait analysis at the walk and trot in dogs with low-grade hindlimb lameness. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol. (2007) 20:299–304. doi: 10.1160/VCOT-07-01-0008,

3. Waxman, AS, Robinson, DA, Evans, RB, Hulse, DA, Innes, JF, and Conzemius, MG. Relationship between objective and subjective assessment of limb function in normal dogs with an experimentally induced lameness. Vet Surg. (2008) 37:241–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-950X.2008.00372.x,

4. Kerwin, S. Orthopedic examination in the cat: clinical tips for ruling in/out common musculoskeletal disease. J Feline Med Surg. (2012) 14:6–12. doi: 10.1177/1098612X11432822,

5. Leonard, CA, and Tillson, M. Feline lameness. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. (2001) 31:143–63. doi: 10.1016/S0195-5616(01)50042-X,

6. Perry, KL. The lame cat: optimising orthopaedic examination and investigation. Compan Anim. (2014) 19:518–23. doi: 10.12968/coan.2014.19.10.518

7. Lecomte, CG, Audet, J, Harnie, J, and Frigon, A. A validation of supervised deep learning for gait analysis in the cat. Front Neuroinform. (2021) 15:712623. doi: 10.3389/fninf.2021.712623,

8. Schnabl-Feichter, E, Tichy, A, Gumpenberger, M, and Bockstahler, B. Comparison of ground reaction force measurements in a population of domestic shorthair and Maine coon cats. PLoS One. (2018) 13:e0208085. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208085,

9. Görska, T, Bem, T, Majczyński, H, and Zmysłowski, W. Unrestrained walking in intact cats. Brain Res Bull. (1993) 32:235–40. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(93)90182-B,

10. Donelan, JM, McVea, DA, and Pearson, KG. Force regulation of ankle extensor muscle activity in freely walking cats. J Neurophysiol. (2009) 101:360–71. doi: 10.1152/jn.90918.2008,

11. Frigon, A, D'Angelo, G, Thibaudier, Y, Hurteau, M-F, Telonio, A, Kuczynski, V, et al. Speed-dependent modulation of phase variations on a step-by-step basis and its impact on the consistency of interlimb coordination during quadrupedal locomotion in intact adult cats. J Neurophysiol. (2014) 111:1885–902. doi: 10.1152/jn.00524.2013,

12. Stadig, S, Lascelles, BDX, and Bergh, A. Do cats with a cranial cruciate ligament injury and osteoarthritis demonstrate a different gait pattern and behaviour compared to sound cats? Acta Vet Scand. (2016) 58:70. doi: 10.1186/s13028-016-0248-x,

13. Addison, ES, and Clements, DN. Repeatability of quantitative sensory testing in healthy cats in a clinical setting with comparison to cats with osteoarthritis. J Feline Med Surg. (2017) 19:1274–82. doi: 10.1177/1098612X17690653,

14. Moreau, M, Guillot, M, Pelletier, J-P, Martel-Pelletier, J, and Troncy, É. Kinetic peak vertical force measurement in cats afflicted by coxarthritis: data management and acquisition protocols. Res Vet Sci. (2013) 95:219–24. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2013.01.020,

15. Schnabl-Feichter, E, Schnabl, S, Tichy, A, Gumpenberger, M, and Bockstahler, B. Measurement of ground reaction forces in cats 1 year after femoral head and neck ostectomy. J Feline Med Surg. (2021) 23:302–9. doi: 10.1177/1098612X20948143,

16. Schweng, G, Bockstahler, B, Tichy, A, Zahn, K, Haimel, G, Schwarz, G, et al. Measurement of ground reaction forces in cats after total hip replacement. J Feline Med Surg. (2024) 26:7894. doi: 10.1177/1098612X241297894,

17. Romans, CW, Conzemius, MG, Horstman, CL, Gordon, WJ, and Evans, RB. Use of pressure platform gait analysis in cats with and without bilateral onychectomy. Am J Vet Res. (2004) 65:1276–8. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.2004.65.1276,

18. Bockstahler, BA, Skalicky, M, Peham, C, Müller, M, and Lorinson, D. Reliability of ground reaction forces measured on a treadmill system in healthy dogs. Vet J. (2007) 173:373–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2005.10.004,

19. Hans, EC, Zwarthoed, B, Seliski, J, Nemke, B, and Muir, P. Variance associated with subject velocity and trial repetition during force platform gait analysis in a heterogeneous population of clinically normal dogs. Vet J. (2014) 202:498–502. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2014.09.022,

20. Häusler, KA, Braun, D, Liu, N-C, Penrose, F, Sutcliffe, MP, and Allen, MJ. Evaluation of the repeatability of kinetic and temporospatial gait variables measured with a pressure-sensitive treadmill for dogs. Am J Vet Res. (2020) 81:922–9. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.81.12.922,

21. Söhnel, K, Fischer, MS, and Häusler, K. Treadmill vs. overground trotting - a comparison of two kinetic measurement systems. Res Vet Sci. (2022) 150:149–55. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2022.06.019,

22. Smith, JL, Chung, SH, and Zernicke, RF. Gait-related motor patterns and hindlimb kinetics for the cat trot and gallop. Exp Brain Res. (1993) 94:308–22. doi: 10.1007/BF00230301,

23. Blaszczyk, J, and Loeb, GE. Why cats pace on the treadmill. Physiol Behav. (1993) 53:501–7. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(93)90144-5,

24. Miller, S, Van Der Burg, J, and Meche, F. Locomotion in the cat: basic programmes of movement. Brain Res. (1975) 91:239–53. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(75)90545-4,

25. Miller, S, and Van Der Meche, F. Movements of the forelimbs of the cat during stepping on a treadmill. Brain Res. (1975) 91:255–69. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(75)90546-6,

26. Doelman, A. Forelimb and hindlimb adjustments to treadmill speed during quadrupedal locomotion after a lateral spinal hemisection in adult cats. Canada: Université de Sherbrooke (2019).

27. Akay, T, McVea, D, Tachibana, A, and Pearson, K. Coordination of fore and hind leg stepping in cats on a transversely-split treadmill. Exp Brain Res. (2006) 175:211–22. doi: 10.1007/s00221-006-0542-3,

28. Escalona, M, Delivet-Mongrain, H, Kundu, A, Gossard, J-P, and Rossignol, S. Ladder treadmill: a method to assess locomotion in cats with an intact or Lesioned spinal cord. J Neurosci. (2017) 37:5429–46. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0038-17.2017,

29. Thibaudier, Y, and Frigon, A. Spatiotemporal control of interlimb coordination during transverse split-belt locomotion with 1:1 or 2:1 coupling patterns in intact adult cats. J Neurophysiol. (2014) 112:2006–18. doi: 10.1152/jn.00236.2014,

30. Laflamme, D. Development and validation of a body condition score system for cats: a clinical tool. Canine Pract. (1997) 22:10–5.

31. Koo, TK, and Li, MY. A guideline of selecting and reporting Intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J Chiropr Med. (2016) 15:155–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jcm.2016.02.012,

32. Pietsch, S, Steigmeier-Raith, S, Reese, S, and Meyer-Lindenberg, A. Reliability of kinetic measurements of healthy dogs examined while walking on a treadmill. Am J Vet Res. (2020) 81:804–9. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.81.10.804,

33. Sandberg, GS, Torres, BT, and Budsberg, SC. Review of kinematic analysis in dogs. Vet Surg. (2020) 49:1088–98. doi: 10.1111/vsu.13477,

34. Off, W, and Matis, U. Ganganalyse beim Hund. Teil 1: Dynamometrische und kinemetrische Messverfahren und ihre Anwendung beim Tetrapoden. Tierarztl Prax. (1997) 25:8–14.

35. Buchner, H, Savelberg, H, Schamhardt, H, Merkens, H, and Barneveld, A. Habituation of horses to treadmill locomotion. Equine Vet J. (1994) 26:13–5. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.1994.tb04865.x

36. Taylor, NF, Evans, OM, and Goldie, PA. Angular movements of the lumbar spine and pelvis can be reliably measured after 4 minutes of treadmill walking. Clin Biomech. (1996) 11:484–6. doi: 10.1016/S0268-0033(96)00036-8,

37. Uccheddu, S, Miklósi, Á, Gintner, S, and Gácsi, M. Comparing pears to apples: unlike dogs, cats need habituation before lab tests. Animals. (2022) 12:3046. doi: 10.3390/ani12213046,

38. Pettit, EM, Sandberg, GS, Volstad, NJ, Norton, MM, and Budsberg, SC. Evaluation of ground reaction forces and limb symmetry indices using ground reaction forces collected with one or two plates in dogs exhibiting a stifle lameness. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol. (2020) 33:398–401. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1715494,

39. Oosterlinck, M, Bosmans, T, Gasthuys, F, Polis, I, Van Ryssen, B, Dewulf, J, et al. Accuracy of pressure plate kinetic asymmetry indices and their correlation with visual gait assessment scores in lame and nonlame dogs. Am J Vet Res. (2011) 72:820–5. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.72.6.820,

40. Budsberg, SC, Jevens, DJ, Brown, J, Foutz, TL, DeCamp, CE, and Reece, L. Evaluation of limb symmetry indices, using ground reaction forces in healthy dogs. Am J Vet Res. (1993) 54:1569–74. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.1993.54.10.1569,

41. Fanchon, L, and Grandjean, D. Accuracy of asymmetry indices of ground reaction forces for diagnosis of hind limb lameness in dogs. Am J Vet Res. (2007) 68:1089–94. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.68.10.1089,

42. Volstad, NJ, Sandberg, G, Robb, S, and Budsberg, SC. The evaluation of limb symmetry indices using ground reaction forces collected with one or two force plates in healthy dogs. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol. (2017) 30:54–8. doi: 10.3415/VCOT-16-04-0054,

43. Gillette, RL, and Zebas, C. A two-dimensional analysis of limb symmetry in the trot of Labrador retrievers. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. (1999) 35:515–20. doi: 10.5326/15473317-35-6-515,

44. Colborne, G. Are sound dogs mechanically symmetric at trot? Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol. (2008) 21:294–301. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1617375,

45. Torres, BT, Moëns, NMM, Al-Nadaf, S, Reynolds, LR, Fu, Y-C, and Budsberg, SC. Comparison of overground and treadmill-based gaits of dogs. Am J Vet Res. (2013) 74:535–41. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.74.4.535,

46. Clough, WT, Canapp, SO Jr, De Taboada, L, Dycus, DL, and Leasure, CS. Sensitivity and specificity of a weight distribution platform for the detection of objective lameness and orthopaedic disease. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol. (2018) 31:391–5. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1667063

47. López, S, Vilar, JM, Rubio, M, Sopena, JJ, Damiá, E, Chicharro, D, et al. Center of pressure limb path differences for the detection of lameness in dogs: a preliminary study. BMC Vet Res. (2019) 15:1–6. doi: 10.1186/s12917-019-1881-1,

48. Moreau, M, Lussier, B, Ballaz, L, and Troncy, E. Kinetic measurements of gait for osteoarthritis research in dogs and cats. Can Vet J. (2014) 55:1057–65.

49. Bennett, D, Zainal Ariffin, SM, and Johnston, P. Osteoarthritis in the cat: 1. How common is it and how easy to recognise? J Feline Med Surg. (2012) 14:65–75. doi: 10.1177/1098612X11432828,

50. Lascelles, BDX, Dong, Y-H, Marcellin-Little, DJ, Thomson, A, Wheeler, S, and Correa, M. Relationship of orthopedic examination, goniometric measurements, and radiographic signs of degenerative joint disease in cats. BMC Vet Res. (2012) 8:10. doi: 10.1186/1746-6148-8-10,

51. Stadig, SM, and Bergh, AK. Gait and jump analysis in healthy cats using a pressure mat system. J Feline Med Surg. (2015) 17:523–9. doi: 10.1177/1098612X14551588,

52. Godfrey, DR. Osteoarthritis in cats: a retrospective radiological study. J Small Anim Pract. (2005) 46:425–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.2005.tb00340.x,

53. Slingerland, LI, Hazewinkel, HAW, Meij, BP, Picavet, P, and Voorhout, G. Cross-sectional study of the prevalence and clinical features of osteoarthritis in 100 cats. Vet J. (2011) 187:304–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2009.12.014,

54. Verdugo, MR, Rahal, SC, Agostinho, FS, Govoni, VM, Mamprim, MJ, and Monteiro, FO. Kinetic and temporospatial parameters in male and female cats walking over a pressure sensing walkway. BMC Vet Res. (2013) 9:129. doi: 10.1186/1746-6148-9-129,

55. Assaf, N, Rahal, S, Mesquita, L, Kano, W, and Abibe, R. Evaluation of parameters obtained from two systems of gait analysis. Aust Vet J. (2019) 97:414–7. doi: 10.1111/avj.12860,

56. Herbin, M, Hackert, R, Gasc, J-P, and Renous, S. Gait parameters of treadmill versus overground locomotion in mouse. Behav Brain Res. (2007) 181:173–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.04.001,

57. Lee, SJ, and Hidler, J. Biomechanics of overground vs. treadmill walking in healthy individuals. J Appl Physiol. (2008) 104:747–55. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01380.2006,

58. Semaan, MB, Wallard, L, Ruiz, V, Gillet, C, Leteneur, S, and Simoneau-Buessinger, E. Is treadmill walking biomechanically comparable to overground walking? A systematic review. Gait Posture. (2022) 92:249–57. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2021.11.009,

59. Riley, PO, Paolini, G, Della Croce, U, Paylo, KW, and Kerrigan, DC. A kinematic and kinetic comparison of overground and treadmill walking in healthy subjects. Gait Posture. (2007) 26:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2006.07.003,

60. Corbee, RJ, Maas, H, Doornenbal, A, and Hazewinkel, HA. Forelimb and hindlimb ground reaction forces of walking cats: assessment and comparison with walking dogs. Vet J. (2014) 202:116–27. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2014.07.001,

Keywords: gait analysis, pressure-sensitive treadmill, locomotion, temporospatial parameter, kinetic gait, feline, cat

Citation: Weißig DM, Dobenecker B, Zablotski Y and Lauer SK (2025) Repeatability and reliability of kinetic and temporospatial gait parameters measured with a pressure-sensitive treadmill in healthy cats. Front. Vet. Sci. 12:1707477. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2025.1707477

Edited by:

Micaela Sgorbini, University of Pisa, ItalyReviewed by:

Datao Xu, Ningbo University, ChinaRainer da Silva Reinstein, Federal University of Santa Maria, Brazil

Copyright © 2025 Weißig, Dobenecker, Zablotski and Lauer. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Susanne K. Lauer, Uy5sYXVlckBsbXUuZGU=

Dorothea M. Weißig

Dorothea M. Weißig Britta Dobenecker

Britta Dobenecker Yury Zablotski

Yury Zablotski Susanne K. Lauer

Susanne K. Lauer