- 1College of Animal Science and Technology, Gansu Agricultural University, Lanzhou, China

- 2Tianjin Key Laboratory of Agricultural Animal Breeding and Healthy Husbandry, College of Animal Science and Veterinary Medicine, Tianjin Agricultural University, Tianjin, China

- 3Huanshan Group Co., Ltd, Qingdao, China

- 4Tianjin Key Laboratory of Animal Molecular Breeding and Biotechnology, Tianjin Livestock and Poultry Health Breeding Technology Engineering Center, Institute of Animal Science and Veterinary, Tianjin Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Tianjin, China

Introduction: Lysozyme (LZ), a naturally occurring antimicrobial peptide, has demonstrated beneficial bioactivities. This study aimed to investigate the effects of dietary LZ supplementation on hepatic antioxidant function and glucolipid metabolism in weaned piglets.

Methods: Forty-eight weaned piglets (Landrace × Yorkshire, 22 days old) were randomly assigned to two dietary treatments: a control (CON) group fed a basal diet, and an LZ group fed the basal diet supplemented with 0.1% LZ for 19 days. Liver index and serum biochemical parameters were measured. Hepatic antioxidant enzyme activities and the mRNA expression of genes related to antioxidant function, lipid metabolism, and gluconeogenesis were determined. Liver fatty acid profiles were also analyzed.

Results: Dietary LZ supplementation significantly increased the liver index and serum concentrations of triglyceride (TG), total cholesterol (TC), and Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol (LDLC) (p < 0.05). In the liver, LZ significantly enhanced catalase (CAT) activity and up-regulated the mRNA expression of antioxidant genes, including NQO1, Nrf2, MnSOD, and CAT (p < 0.05). Furthermore, LZ altered the hepatic fatty acid profile by increasing the contents of C16:1, C17:0, C20:3n6, and C18:1n9t (p < 0.05). Gene expression analysis revealed that LZ up-regulated CPT1α and PPARα (p < 0.05) but down-regulated SCD and SREBP1 (p < 0.05). Additionally, LZ supplementation significantly increased the mRNA expression of gluconeogenic enzymes, including PEPCK, PC, and G6PC (p < 0.05).

Discussion: The results indicate that dietary LZ supplementation enhances the hepatic antioxidant defense system, likely through activation of the Nrf2 signaling pathway. Concurrently, LZ modulates lipid metabolism by promoting fatty acid oxidation (via up-regulation of PPARα and CPT1α) and inhibiting lipogenesis (via down-regulation of SREBP1 and SCD). The up-regulation of key gluconeogenic genes suggests improved hepatic glucose production. In conclusion, LZ improves antioxidant capacity and regulates glucolipid metabolism in the liver of weaned piglets, supporting its potential as a functional feed additive in pig production.

1 Introduction

In modern pig husbandry systems, weaning is a critical period for pig feeding (1, 2). However, weaning often results in stress, thereby reducing nutrient digestion and absorption (3). Piglets are born with limited energy stores and a restricted capacity to oxidize fatty acids and amino acids; thus, insufficient energy supply may ultimately cause death in weaned piglets (4). The liver plays a crucial role in energy utilization and maintaining normal hepatic energy metabolism (5). Dietary intervention provides a beneficial approach for meeting the nutritional needs of weaned piglets while supporting their health. Following China’s complete prohibition of antibiotic growth promoters in animal feed in 2020, developing novel, safe, and effective feed additives has become an important research priority for sustainable pig production (6). Consequently, there is an urgent need to identify a natural and effective feed additive to alleviate oxidative stress in piglets.

Lysozyme (LZ) is a protein peptide with natural antibacterial activity, widely distributed in animal and plant tissues as well as their secretions (7, 8). Accumulating evidence indicates that LZ exhibits beneficial bioactivities, including anti-inflammatory, anti-obesity, and intestinal microbiota-modulating effects (9). Significantly, LZ has demonstrated effective antioxidant capability. An in vivo study evaluating the impact of dietary LZ on antioxidant capacity in juvenile gibel carp reported a significant increase in serum superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity and a marked decrease in malondialdehyde content in the mid-intestine (10). Furthermore, LZ supplementation in broiler chickens induced upregulation of intestinal SOD1 and GSH-Px (11). However, the effects of LZ supplementation on hepatic glucose and lipid metabolism have not yet been studied.

This study aimed to evaluate the effects of dietary LZ supplementation on hepatic glucose and lipid metabolism, as well as antioxidant function in weaned piglets. The findings from this research will provide important insights into the molecular mechanisms by which LZ modulates metabolic pathways, supporting its potential application as a functional feed additive in swine production.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Animal ethics statement

The experimental design and procedure used in this study were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Institute of Subtropical Agroecology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (IACUC # 201302).

2.2 Experimental materials

The LZ used in the experiment was provided by Zhumadian Huazhong Chia Tai Co. Ltd. (Zhumadian, China) in powdered form with an activity of 50 U/mg (0.1%) and the main effective component being LZ dimer (12). The basal diet (Table 1) met or exceeded the nutritional requirements of weaned piglets as recommended by the United States National Research Council 1998.

2.3 Experimental design and treatments

In this experiment, 48 healthy weaned piglets (Landrace × Yorkshire, half male and half female) aged 22 d and of similar size were selected from 6 litters, and were randomly divided into 2 groups with 6 replicates in each group and 4 piglets in each replicate. Dietary treatments were designed as follows: (1) control group (CON, basal diet); (2) LZ group (LZ, basal diet + 0.1% LZ), and the experiment lasted for 19 d. Piglets in each replicate were bred in 1 pen, the ambient temperature was controlled at about 28 °C to 24 °C and the humidity was controlled at 65 to 75%. Piglets were fed 6 times a day (at 06:30, 09:00, 11:30, 14:30, 17:30 and 22:00, respectively) and had free access to water. All piglets were vaccinated according to the regulations of the farm. Throughout the experimental period, all piglets remained healthy, and no mortality or morbidity occurred.

2.4 Sample collection

On the final day of the trial, 6 pigs were randomly selected from each treatment for blood and tissue sampling. Blood samples were collected into 10 mL tubes and then centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C to recover serum samples. The liver, spleen, and kidneys were promptly collected after exsanguination. Liver samples were harvested and rinsed several times with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline and then immediately snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at 80 °C for RNA extraction. The liver, spleen, and kidneys were weighed immediately after collection for the subsequent calculation of organ indexes.

2.5 Serum parameters

Serum biochemical parameters, including blood urea nitrogen (BUN), triglyceride (TG), Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol (LDLC), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), total cholesterol (TC) were measured using an automated biochemistry analyzer (Synchron CX Pro, Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, United States) and the commercial kit (Aokai (Suzhou) Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Suzhou, China).

2.6 Measurement of antioxidant parameters in liver

The activities of antioxidant-related enzymes in liver homogenate including total antioxidative capacity (T-AOC), superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and the content of malondialdehyde (MDA) were determinated by kits purchased from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (Nanjing, China).

2.7 Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

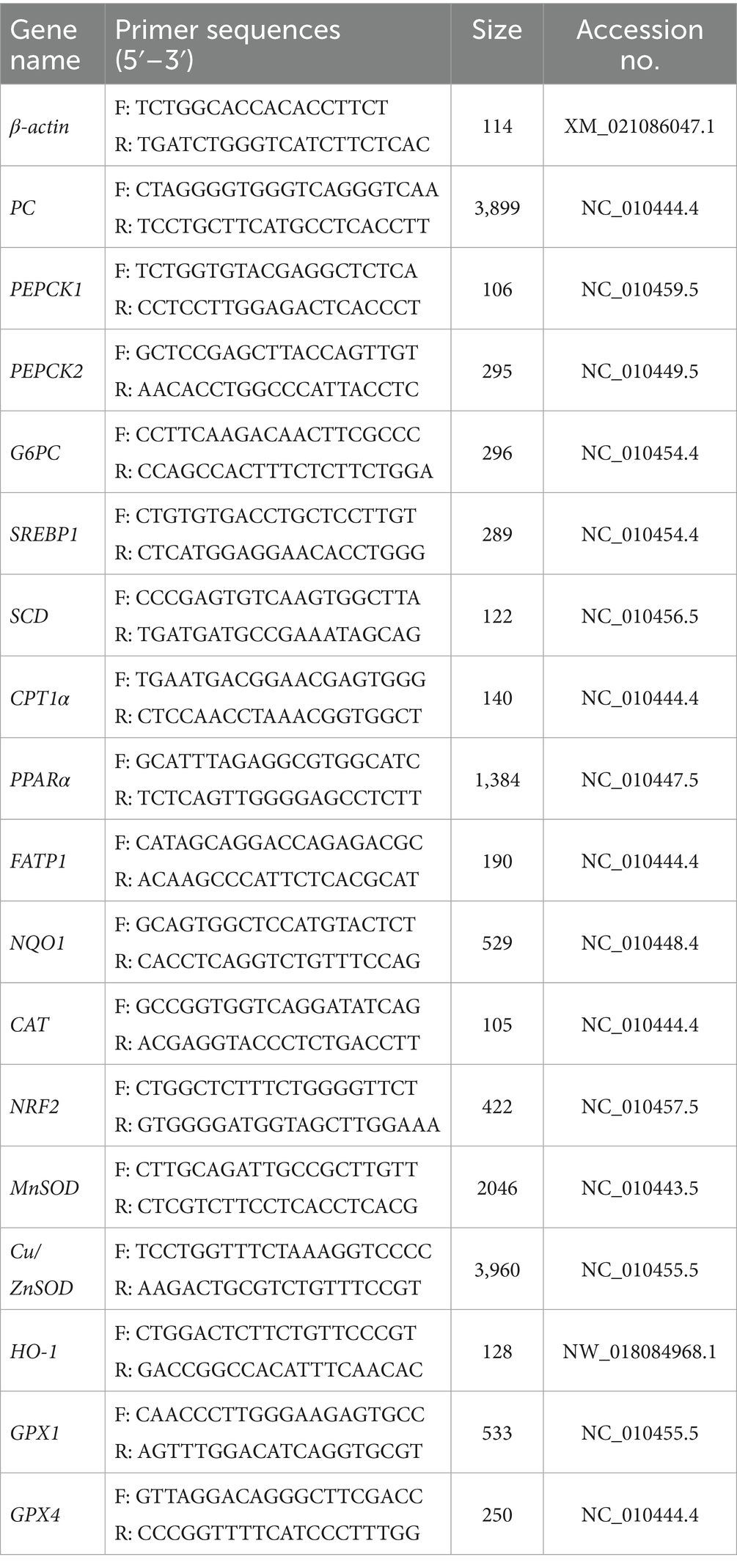

According to our previous study (3), total RNA was isolated from the liver tissue, and the concentration and purity of RNA were determined by NanoDrop Oneᶜ (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). According to the instructions of the Primer-script TM RT Reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (TaKaRa, Dalian, China; Code No. RR047A), gDNA was removed and reverse-transcribed and the reverse-transcribed cDNA was stored in a refrigerator at −20 °C for later use. According to the manufacturer’s protocol, the RT-qPCR was performed on a Roche LightCyclerfi 480 instrument II (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) with 10 μL total volume reaction, consisting of 5 μL 2X SYBRR Green Pro Taq HS Premix II, 2 μL cDNA template, 0.4 μL each of the forward and reverse primers, and 2.2 μL RNase free water. Relative gene expression levels were analyzed using the 2(-ΔΔCt) method and normalization with β-actin as a housekeeping gene. The primers required were shown in Table 2.

2.8 Fatty acids analysis in liver of piglets

Based on our previously published method (13), the fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) were prepared from liver samples. Briefly, total lipids were extracted with a chloroform-methanol mixture (2:1, v/v), followed by transesterification using 14% boron trifluoride-methanol to generate FAMEs. The FAMEs were then analyzed using an Agilent 6,890 N gas chromatograph (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with a flame ionization detector and a fused-silica capillary column. Individual fatty acids were identified by comparing their retention times with those of known FAME standards, and their contents were quantified based on peak area, expressed as a percentage of total fatty acids.

2.9 Statistical analysis

The original data were preliminarily sorted out by Excel 2010, and the independent sample t-test was carried out for the data by SPSS 19.0. Data were expressed as least squares means ± standard error of mean (SEM). The values were considered to be an extremely significant difference when p < 0.01, a significant difference when p < 0.05 and a tendency when 0.05 < p < 0.10.

3 Result

3.1 Growth performance

As previously reported in a study focused on growth performance from the same experimental cohort dietary LZ supplementation significantly improved the average daily gain in weaned piglets (14).

3.2 Organ indexs

Compared with CON, LZ significantly augmented the liver of weaned piglets (p < 0.05), but had no significant effect on spleen index and kidney index (p > 0.10) (Table 3).

3.3 Serum biochemical parameters

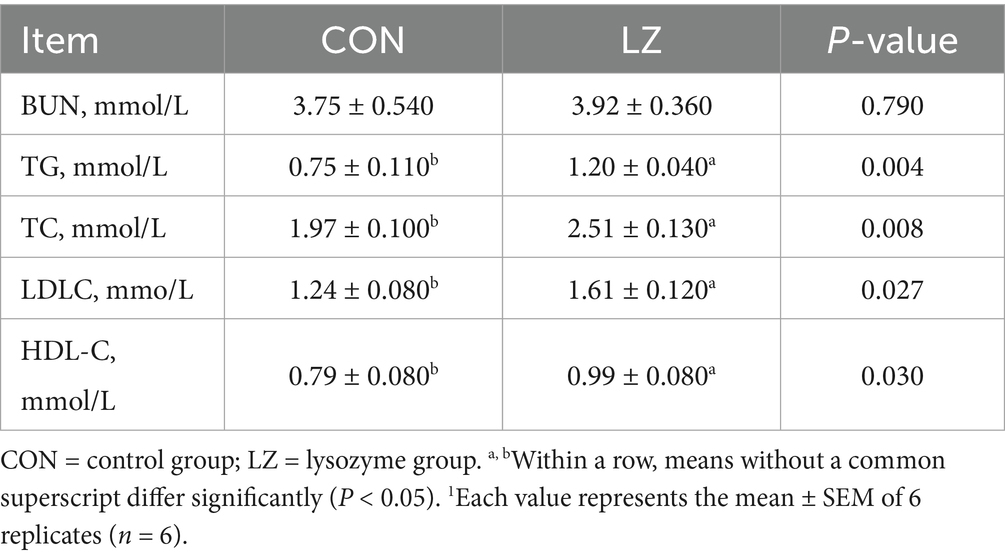

Table 4 showed the serum biochemical indices of weaned piglets. In this study, LZ significantly increased (p < 0.05) the concentration of TG, TC, HDL-C and LDLC in serum compared to CON group. However, no significant differences were found in serum BUN indices between the LZ and CON group (p > 0.10).

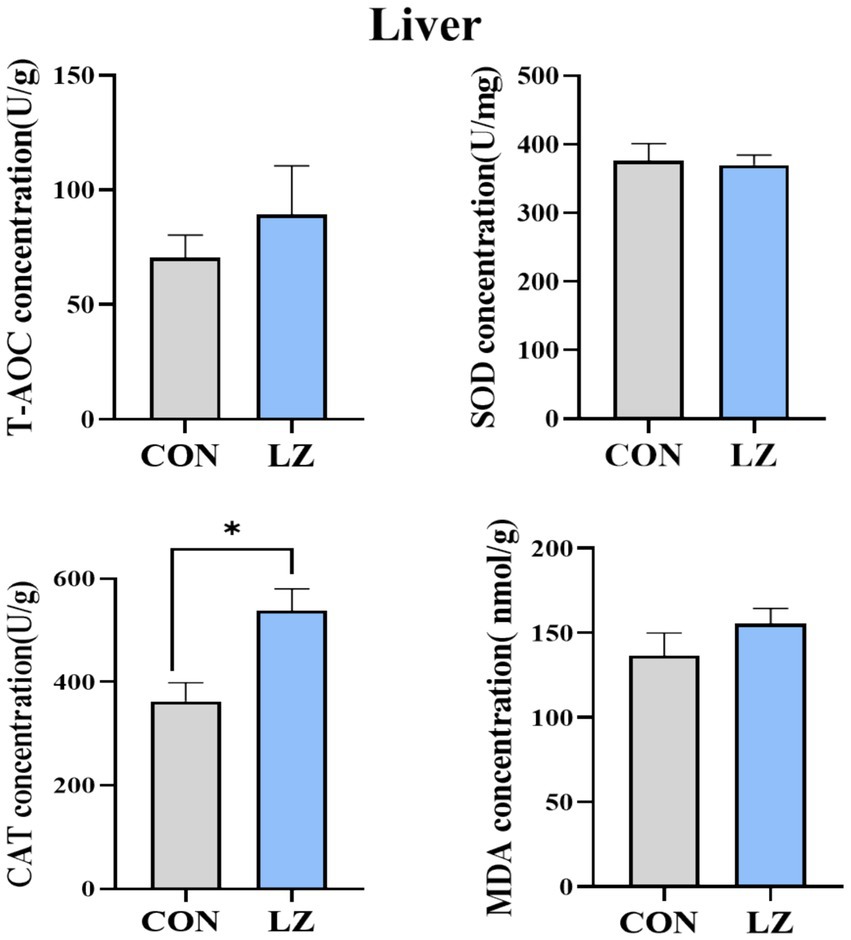

3.4 Liver antioxidant content

As shown in Figure 1, LZ supplementation affected the liver antioxidant parameters of weaned piglets. The liver CAT activities were significantly increased (p < 0.05) in the LZ group when compared with the CON group. There was no significant difference in serum T-AOC, SOD, MDA between the 2 groups.

Figure 1. Effects of LZ supplementation on hepatic antioxidant content in weaned piglets. Malonaldehyde. Values are presented as mean ± SEM; * and **indicate a statistically significant difference by t-test at p < 0.05 and p < 0.01. CON = control group; LZ = lysozyme group.

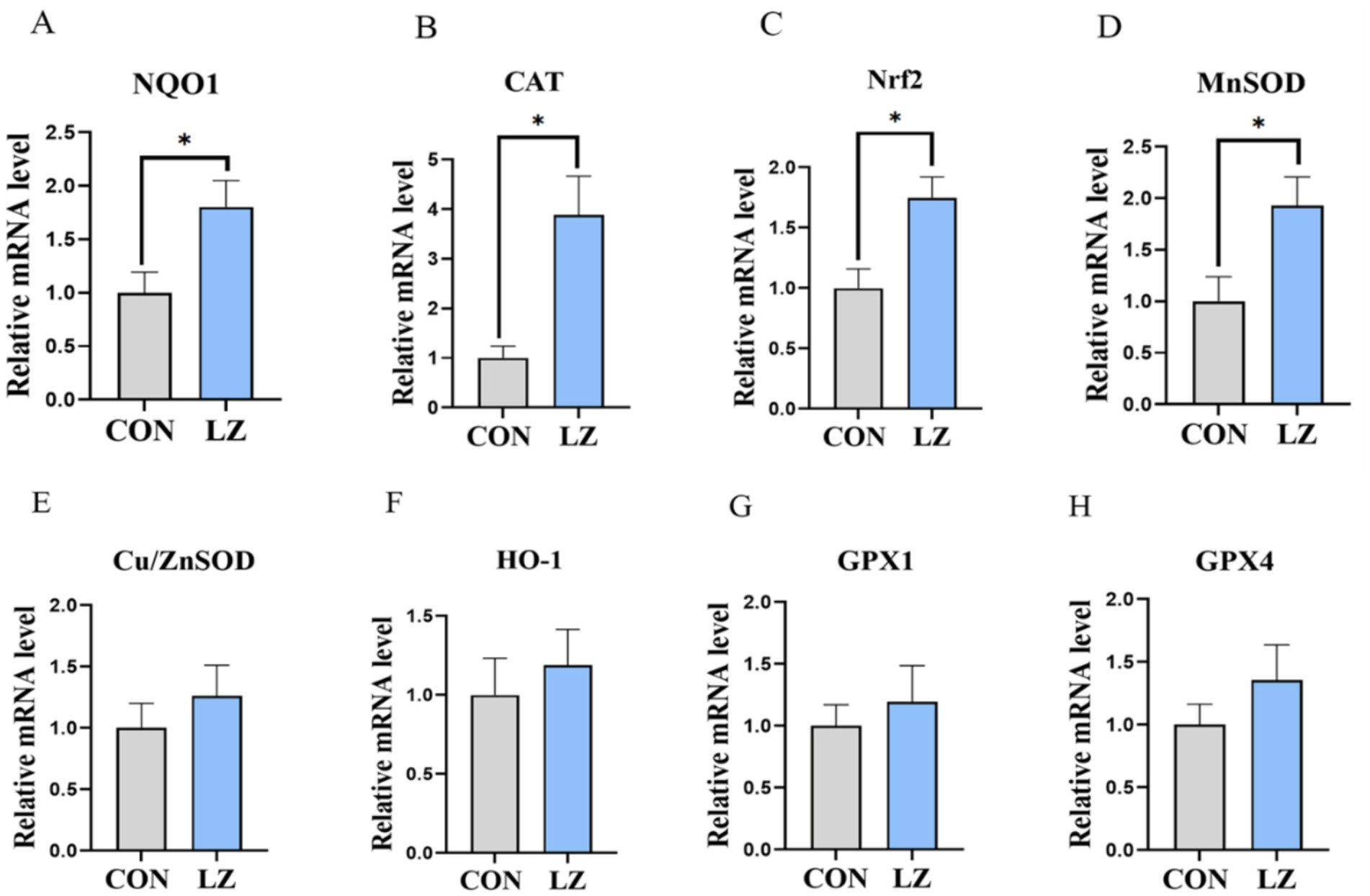

3.5 Antioxidant enzyme gene expression in liver

We also evaluated the effects of dietary LZ supplementation on antioxidant capacity of weaned piglets (Figure 2). The results exhibited that the mRNA expression of NADH quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1), nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), Mn superoxide dismutas (MnSOD), and catalase (CAT) were significantly up-regulated (p < 0.05) of the LZ group compared with the CON group.

Figure 2. (A–H) Effects of LZ supplementation on hepatic antioxidant activity in weaned piglets. Values are presented as mean ± SEM; * and **indicate a statistically significant difference by t-test at p < 0.05 and p < 0.01. CON = control group; LZ = lysozyme group.

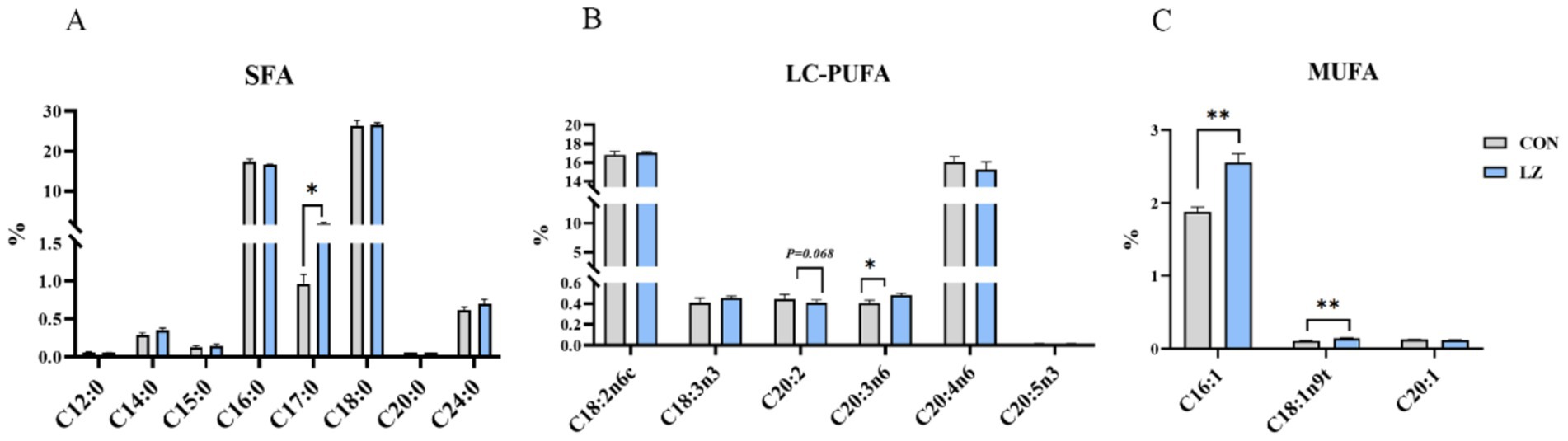

3.6 Liver fatty acid profile

The liver fatty acid profiles of the weaned piglets are shown in Figure 3. Interestingly, it was found that dietary LZ supplementation significantly increased the content of C16:1 fatty acid (p < 0.01), C17:0 fatty acid (p < 0.05), C20:3n6 fatty acid (p < 0.01) and C18:1n9t (p < 0.05) fatty acid in liver. Besides, the results showed that the C20:2 (p = 0.068) content in the liver of weaned piglets from the LZ group tended to decrease.

Figure 3. (A–C) Effects of LZ supplementation on hepatic fatty acid profile in weaned piglets. SFA, saturated fatty acid (including C12:0, C14:0, C16:0, C15:0, C17:0, C18:0, C20:0, and C24:0); MUFA, monounsaturated fatty acids (including C16:1, C18:1n9t, and C20:1); LC-PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acids (including C18:2n6c, C18:3n3, C20:2, C20:3n6, C20:4n6, and C22:5n3); Values are presented as mean ± SEM; * and **indicate a statistically significant difference by t-test at p < 0.05 and p < 0.01. CON = control group; LZ = lysozyme group.

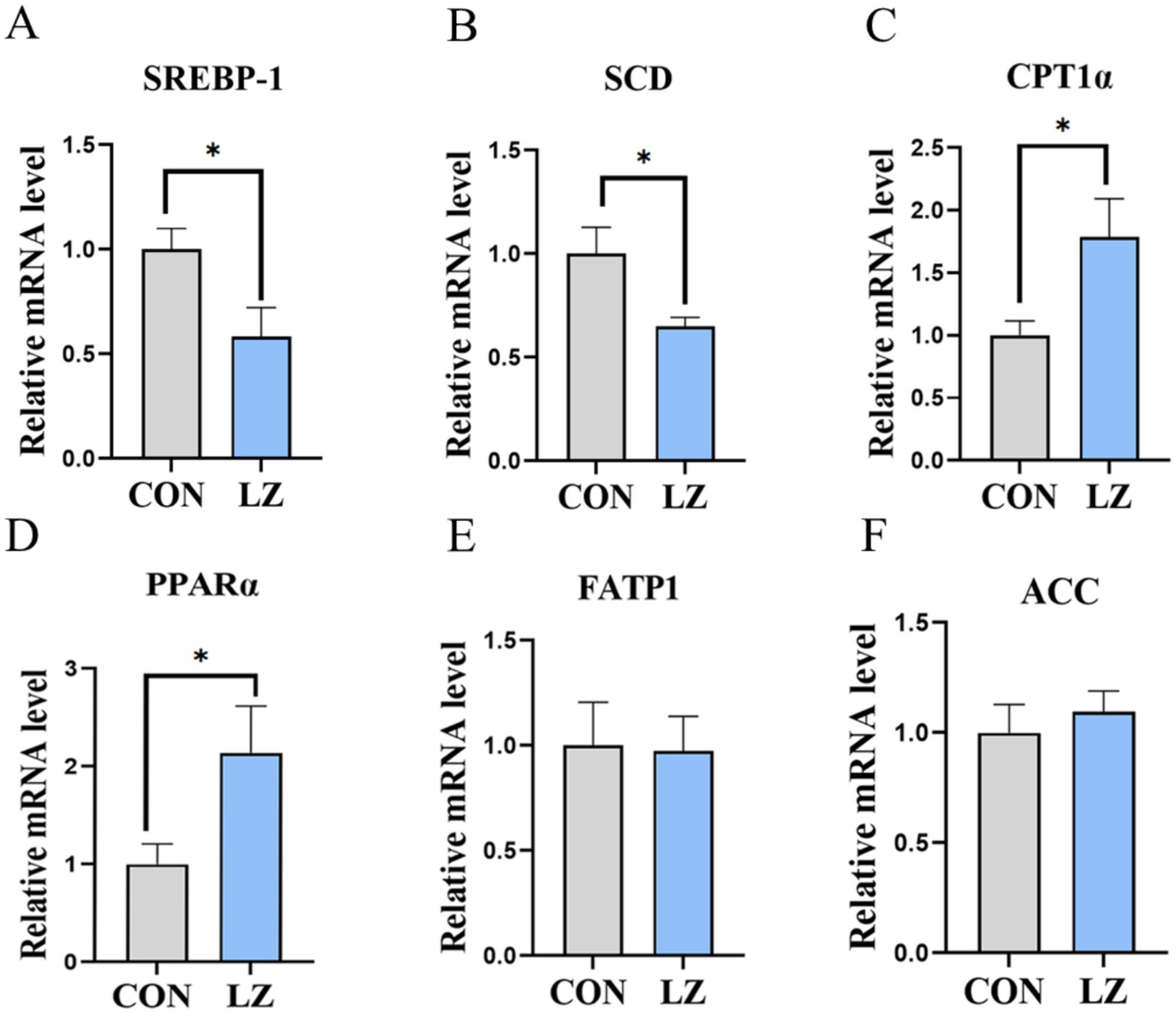

3.7 Hepatic lipid metabolism-related gene expression

To evaluate the effects of LZ supplementation on lipid synthesis, catabolism, and transport of weaned piglets, we measured the related gene expression in the liver (Figure 4). The results showed that the mRNA expression of carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1 α (CPT1α) and peroxisome proliferator activated receptors (PPARα) were significantly increased (p < 0.05), and stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD) and sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 (SREBP1)were significantly down-regulated (p < 0.05) in the liver in the LZ group compared with the CON group.

Figure 4. (A–F) Effects of LZ supplementation on hepatic lipid metabolism in weaned piglets. Values are presented as mean ± SEM; * and **indicate a statistically significant difference by t-test at p < 0.05 and p < 0.01. CON = control group; LZ = lysozyme group.

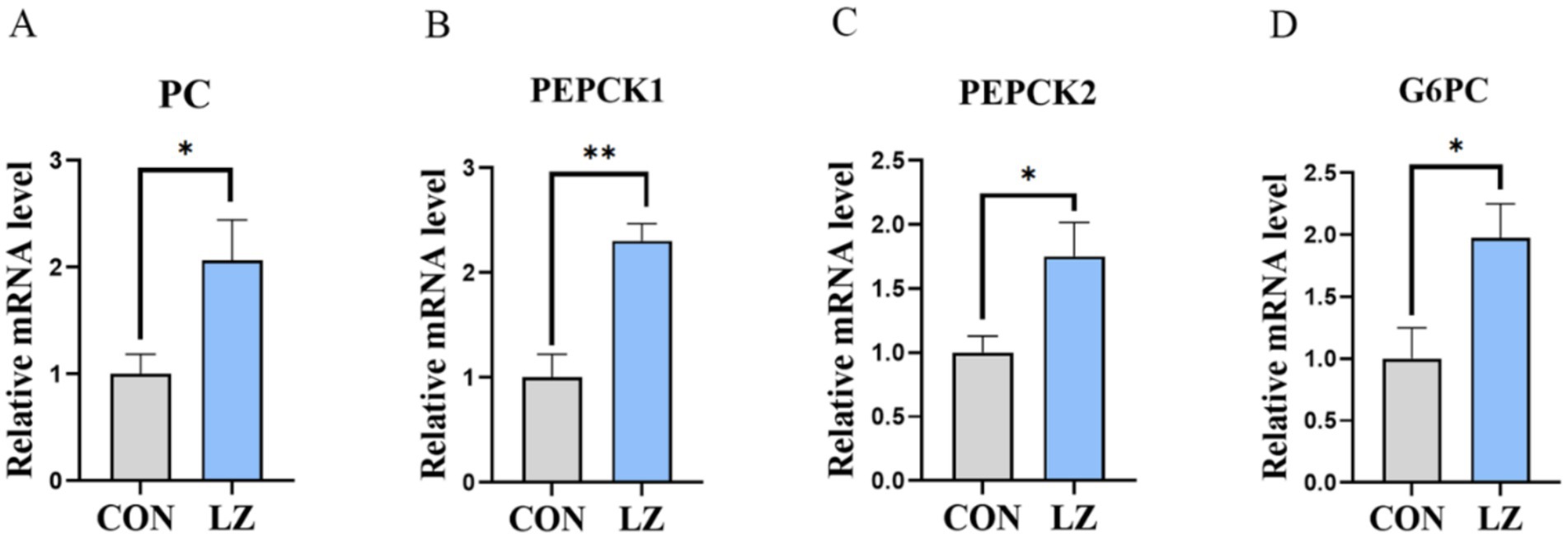

3.8 Gene expression of liver gluconeogenesis

Relative mRNA expression of genes related to glucose metabolism in the liver (Figure 5) showed that dietary LZ could significantly increase expression of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK), pyruvate carboxylase (PC) and Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PC).

Figure 5. (A–D) Effects of LZ supplementation on hepatic glucose metabolism in weaned piglets. Values are presented as mean ± SEM; * and **indicate a statistically significant difference by t-test at p < 0.05 and p < 0.01. CON = control group; LZ = lysozyme group.

4 Discussion

The liver participates in complex physiological processes, including lipid metabolism, glucose homeostasis, and oxidative stress, which play crucial roles in maintaining normal energy metabolism (4, 15). However, weaning stress induces hepatic oxidative stress and oxidative damage, severely impairing liver function in piglets. LZ is a safe, non-toxic biological enzyme with strong antioxidant properties (16–18). LZ contains a high proportion of hydrophobic and positively charged amino acids, whose antioxidant activities are markedly enhanced upon hydrolysis. Moreover, LZ can combine with other substances to further enhance antioxidant capacity (19, 20). Previous research demonstrated that dietary LZ supplementation significantly increased intestinal levels of SOD1 and GSH-Px in broiler chickens, indicating a beneficial effect on antioxidative capacity (11). Although few studies have reported the direct effects of LZ on glycolipid metabolism in weaned piglets, some studies suggested that LZ may indirectly influence glycolipid metabolism by modulating other biological functions (21). Thus, this study aimed to investigate the effects of LZ supplementation on hepatic glucolipid metabolism and antioxidant function in weaned piglets.

To some extent, the organ index can reflect organ function (22). The liver is the most metabolically active organ in the body and the largest digestive gland, responsible for glycogen storage, bile secretion, and synthesis of secretory proteins (23). Our results showed that LZ significantly increased the liver index in weaned piglets, indicating that LZ promoted hepatic development. Blood lipid concentrations reflect the status of lipid metabolism in the body (24). In this study, dietary LZ significantly increased serum levels of TC, TG, and LDLC compared to the control group. Cholesterol (CHOL) is released from the liver into the bloodstream, carried by LDL, and transported throughout the body to provide metabolic energy and support other vital activities (19, 20). Elevated LDLC and cholesterol levels may indicate improved nutrient absorption in rapidly growing piglets (25, 26). Collectively, our results suggest that LZ can enhance hepatic function in weaned piglets.

Under normal physiological conditions, animals maintain a state of dynamic redox balance. However, stressors such as weaning can stimulate excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), disrupting this redox equilibrium (27). Research has demonstrated that the liver of weaned piglets contains elevated levels of free radicals and significant lipid peroxidation (28). In this study, dietary LZ supplementation significantly increased catalase (CAT) activity in the liver of weaned piglets. To further elucidate the antioxidant mechanisms of LZ supplementation in weaned piglets, we examined gene expression levels. The Nrf2 signaling pathway constitutes a crucial defense mechanism against oxidative damage, promoting the transcription of multiple downstream protective proteins (29, 30). Our results revealed that LZ significantly upregulated the mRNA expression of the transcription factor Nrf2, a key regulator of antioxidant responses. The subsequent upregulation of its downstream target genes, including NQO1 and MnSOD, confirmed the activation of this cytoprotective pathway. Importantly, increased CAT mRNA expression correlated with significantly elevated catalase enzyme activity. This coordinated enhancement at both transcriptional and functional levels suggests that LZ fortifies the hepatic antioxidant defense system by activating the Nrf2 pathway, thus improving the ability of piglets to counteract oxidative stress (31).

A previous study indicated that lysosomal membrane proteins (LMPs) are closely associated with glucose and lipid metabolism (21). However, whether LZ affects glucolipid metabolism in weaned pigs and its underlying mechanisms remain unclear. Medium-chain fatty acids (MCFAs) and long-chain fatty acids (LCFAs) are efficiently absorbed and metabolized by piglets, providing immediate energy (19, 20). We evaluated hepatic fatty acid profiles in weaned piglets to determine the effects of LZ on fatty acid composition. We observed that LZ significantly increased the content of palmitoleic acid (C16:1), C17:0, C20:3n6, and C18:1n9t. As previously reported, increased C17:0 content is associated with ferritin, inflammation, and elevated glucose, triglyceride, and insulin levels (19, 20). As an unsaturated fatty acid, C16:1 participates in energy metabolism, inflammatory response regulation, cell signaling, antioxidant activity, and cell membrane structure and maintenance (32). C18:1n9t is a highly unsaturated fatty acid with significant potential in lipid metabolism regulation, cardiovascular protection, and anti-cancer activity (33). In addition, C20:2 content tended to decrease. This reduction in C20:0 proportion is associated with ceramide synthesis (19, 20).

The key processes of lipid metabolism include lipogenesis, lipolysis, and fatty acid oxidation, with the liver being the primary organ for fatty acid synthesis and utilization (34). Therefore, the mRNA expression levels of lipid metabolism-related genes were evaluated to further investigate the effects of LZ on lipid metabolism. Carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 alpha (CPT1α) is a rate-limiting enzyme in fatty acid β-oxidation, responsible for converting long-chain fatty acids into fatty acyl-coenzyme A, which subsequently enters mitochondria for β-oxidation to generate ATP and energy (35, 36). Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARα) is a nuclear transcription factor involved in regulating intracellular fatty acid uptake and triglyceride catabolism, as well as controlling CPT1α expression (37). Our results demonstrated that hepatic mRNA expression of CPT1α and PPARα was significantly upregulated in the LZ group compared with the CON group, suggesting that LZ promotes lipid catabolism in weaned piglets by regulating CPT1α expression. Furthermore, dietary LZ supplementation significantly increased the hepatic mRNA expression of stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD) and sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 (SREBP-1). SCD, primarily expressed in adipose tissue, is crucial for synthesizing monounsaturated fatty acids and determining the composition of phospholipids and triglycerides in cellular membranes (38). SREBP-1 plays an essential role in cholesterol biosynthesis and regulates lipid synthesis by activating the expression of lipid metabolism-related genes (39, 40). Thus, dietary LZ supplementation could enhance hepatic lipid metabolism in piglets.

The beneficial effects of LZ supplementation on hepatic function and systemic lipid metabolism are closely linked to its antioxidant properties. Activation of the Nrf2 signaling pathway enhanced the hepatic antioxidant defense system, as evidenced by increased CAT activity and upregulated expression of NQO1 and MnSOD. This improvement in antioxidant capacity likely established favorable conditions for lipid metabolic regulation. Given that oxidative stress impairs mitochondrial function and promotes lipotoxicity, LZ-mediated alleviation of oxidative stress may have contributed to the upregulation of PPARα and its downstream target CPT1α, which are critical regulators of fatty acid β-oxidation. Simultaneously, the downregulation of SREBP-1 and SCD suggests suppressed lipogenesis. Collectively, this metabolic shift from lipid accumulation toward oxidation and utilization provides a plausible explanation for the improved serum lipid profile and supports the conclusion that LZ enhances hepatic function. These findings demonstrate that LZ, by activating Nrf2-mediated antioxidant responses, promotes lipid metabolic reprogramming that ultimately benefits liver health.

In the case of long-term stress, animals regulate glucose homeostasis to meet energy demands (41). After birth, piglets rapidly deplete glycogen stores, making hepatic gluconeogenesis, the primary energy source for weaned piglets, extremely important for growth (42, 43). Gluconeogenesis is directly controlled by rate-limiting enzymes, including PEPCK, G6PC, and PC (44, 45). Although many tissues express gluconeogenic enzymes, only the liver and kidney express G6PC, which enables glucose release into the circulation and contributes to the systemic glucose pool. The gluconeogenic pathway involves both mitochondrial and cytosolic enzymes, and two forms of PEPCK have been identified in the liver of most mammalian species: mitochondrial PEPCK-2 and cytosolic PEPCK-1 (46). In the present study, analysis of mRNA expression levels of gluconeogenesis-related genes showed that LZ supplementation significantly increased the expression of key rate-limiting enzymes, including PC, G6PC, PEPCK1, and PEPCK2. Therefore, dietary LZ may enhance hepatic gluconeogenesis and help maintain glucose metabolic balance in weaned piglets by upregulating essential gluconeogenic enzymes.

5 Conclusion

In conclusion, we demonstrated that LZ could promote liver function such as improve liver lipid metabolism, enhance liver gluconeogenesis to maintain the balance of glucose metabolism in weaned piglets. Furthermore, we found LZ improve the antioxidant ability of weaned piglets by regulating Nrf2 signaling pathway and increasing antioxidant enzyme activities. This study provided an important theoretical basis for LZ to become a feed additive with broad application prospects in pig production.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by Animal Care and Use Committee of the Institute of Subtropical Agroecology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

YW: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. HZ: Methodology, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. YZ: Writing – review & editing, Resources. CX: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. GC: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Project administration.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The research work was supported by Lanzhou Talent Innovation and Entrepreneurship Project-Application and promotion of digital non-resistant sweet animal product production technology (23–3-110).

Conflict of interest

YZ was employed by the Huanshan Group Co., Ltd.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Campbell, JM, Crenshaw, JD, and Polo, J. The biological stress of early weaned piglets. J Anim Sci Biotechnol. (2013) 4:19. doi: 10.1186/2049-1891-4-19

2. Xiong, X, Yang, HS, Wang, XC, Hu, Q, Liu, CX, Wu, X, et al. Effect of low dosage of chito-oligosaccharide supplementation on intestinal morphology, immune response, antioxidant capacity, and barrier function in weaned piglets. J Anim Sci. (2015) 93:1089–97. doi: 10.2527/jas.2014-7851

3. Feng, Y, Wu, Y, Wang, J, Dong, Z, Yu, Q, Xia, S, et al. Enteromorpha prolifera polysaccharide-Fe(III) complex promotes intestinal development as a new iron supplement. Sci China Life Sci. (2024) 68:219–31. doi: 10.1007/s11427-023-2562-9

4. Xie, C, Wang, Q, Wang, J, Tan, B, Fan, Z, Deng, Z-Y, et al. Developmental changes in hepatic glucose metabolism in a newborn piglet model: a comparative analysis for suckling period and early weaning period. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2016) 470:824–30. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.01.114

5. Alamri, Z. The role of liver in metabolism: an updated review with physiological emphasis. Int J Basic Clin Pharmacol. (2018) 7:2271. doi: 10.18203/2319-2003.ijbcp20184211

6. Wen, R, Li, C, Zhao, M, Wang, H, and Tang, Y. Withdrawal of antibiotic growth promoters in China and its impact on the foodborne pathogen Campylobacter coli of swine origin. J Front Microbiol. (2022) 13:1004725. doi: 10.3389/FMICB.2022.1004725

7. Yu, S, Balasubramanian, I, Laubitz, D, Tong, K, Bandyopadhyay, S, Lin, X, et al. Paneth cell-derived lysozyme defines the composition of mucolytic microbiota and the inflammatory tone of the intestine. Immunity. (2020) 53:398–416. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.07.010

8. Yvon, S, Schwebel, L, Belahcen, L, Tormo, H, Peter, M, Haimoud-Lekhal, DA, et al. Effects of thermized donkey milk with lysozyme activity on altered gut barrier in mice exposed to water-avoidance stress. J Dairy Sci. (2019) 102:7697–706. doi: 10.3168/jds.2019-16642

9. Larsen, IS, Jensen, BH, Bonazzi, E, Choi, BSY, Kristensen, NN, Schmidt, EGW, et al. Fungal lysozyme leverages the gut microbiota to curb dss-induced colitis. Gut Microbes. (2021) 13:1988836. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2021.1988836

10. Chen, Y, Zhu, X, Yang, Y, Han, D, Jin, J, and Xie, S. Effect of dietary lysozyme on growth, immune response, intestine microbiota, intestine morphology and resistance to Aeromonas hydrophilia in gibel carp (Carassius auratus gibelio). Aquac Nutr. (2014) 20:229–41. doi: 10.1111/anu.12069

11. Abdel-Latif, MA, El-Far, AH, Elbestawy, AR, Ghanem, R, Mousa, SA, and Abd El-Hamid, HS. Exogenous dietary lysozyme improves the growth performance and gut microbiota in broiler chickens targeting the antioxidant and non-specific immunity mRNA expression. PLoS One. (2017) 12:e0185153. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0185153

12. Long, Y, Lin, S, Zhu, J, Pang, X, Fang, Z, Lin, Y, et al. Effects of dietary lysozyme levels on growth performance, intestinal morphology, non-specific immunity and mRNA expression in weanling piglets. Anim Sci. (2016) 87:411–8. doi: 10.1111/asj.12444

13. Zhang, Y, Guo, S, Xie, C, Wang, R, Zhang, Y, Zhou, X, et al. Short-term Oral UMP/UR Administration regulates lipid metabolism in early-weaned piglets. Animals. (2019) 9:2076–615. doi: 10.3390/ani9090610

14. Wu, Y, Cheng, B, Ji, L, Lv, X, Feng, Y, Li, L, et al. Dietary lysozyme improves growth performance and intestinal barrier function of weaned piglets. Anim Nutr. (2023) 14:249–58. doi: 10.1016/j.aninu.2023.06.003

15. Wu, G, Wu, Z, Dai, Z, Yang, Y, Wang, W, Liu, C, et al. Dietary requirements of “nutritionally non-essential amino acids” by animals and humans. Amino Acids. (2013) 44:1107–13. doi: 10.1007/s00726-012-1444-2

16. Vanderkelen, L, Ons, E, Van Herreweghe, JM, Callewaert, L, Goddeeris, BM, and Michiels, CW. Role of lysozyme inhibitors in the virulence of avian pathogenic escherichia coli. PLoS One. (2012) 7:e45954. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045954

17. Wang, G, Lo, LF, Forsberg, LS, and Maier, RJ. Helicobacter pylori peptidoglycan modifications confer lysozyme resistance and contribute to survival in the host. MBio. (2012) 3:e00409–12. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00409-12

18. Wu, T, Jiang, Q, Wu, D, Hu, Y, Chen, S, Ding, T, et al. What is new in lysozyme research and its application in food industry? A review. Food Chem. (2019) 274:698–709. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.09.017

19. Zhou, N, Zhao, Y, Yao, Y, Wu, N, Xu, M, Du, H, et al. Antioxidant stress and anti-inflammatory activities of egg white proteins and their derived peptides: a review. J Agric Food Chem. (2022a) 70:5–20. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.1c04742

20. Zhou, T, Cheng, B, Gao, L, Ren, F, Guo, G, Wassie, T, et al. Maternal catalase supplementation regulates fatty acid metabolism and antioxidant ability of lactating sows and their offspring. Front Vet Sci. (2022b) 9:1014313. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.1014313

21. Gu, J, Geng, M, Qi, M, Wang, L, Zhang, Y, and Gao, J. The role of lysosomal membrane proteins in glucose and lipid metabolism. FASEB J. (2021) 35:e21848. doi: 10.1096/fj.202002602R

22. Lazic, SE, Semenova, E, and Williams, DP. Determining organ weight toxicity with Bayesian causal models: improving on the analysis of relative organ weights. Sci Rep. (2020) 10:6625. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-63465-y

23. Grijalva, J, and Vakili, K. Neonatal liver physiology. Semin Pediatr Surg. (2013) 22:185–9. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2013.10.006

24. Grabner, GF, Xie, H, Schweiger, M, and Zechner, R. Lipolysis: cellular mechanisms for lipid mobilization from fat stores. Nat Metab. (2021) 3:1445–65. doi: 10.1038/s42255-021-00493-6

25. Maki, KC. The fat of the matter: lipoprotein effects of dietary fatty acids vary by body weight status. Am J Clin Nutr. (2019) 110:795–6. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqz166

26. Ooi, LG, Ahmad, R, Yuen, KH, and Liong, MT. Lactobacillus gasseri [corrected] cho-220 and inulin reduced plasma total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol via alteration of lipid transporters. J Dairy Sci. (2010) 93:5048–58. doi: 10.3168/jds.2010-3311

27. Jakubczyk, K, Dec, K, Kałduńska, J, Kawczuga, D, Kochman, J, and Janda, K. Reactive oxygen species - sources, functions, oxidative damage. Pol Merkur Lekarski. (2020) 48:124–7.

28. Yu, L, Li, H, Peng, Z, Ge, Y, Liu, J, Wang, T, et al. Early weaning affects liver antioxidant function in piglets. Animals. (2021) 11:679. doi: 10.3390/ani11092679

29. Tonelli, C, Chio, IIC, and Tuveson, DA. Transcriptional regulation by nrf2. Antioxid Redox Signal. (2018) 29:1727–45. doi: 10.1089/ars.2017.7342

30. Vomhof-Dekrey, EE, and Picklo, MJ Sr. The nrf2-antioxidant response element pathway: a target for regulating energy metabolism. J Nutr Biochem. (2012) 23:1201–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2012.03.005

31. Zhu, H, Jia, Z, Misra, BR, Zhang, L, Cao, Z, Yamamoto, M, et al. Nuclear factor e2-related factor 2-dependent myocardiac cytoprotection against oxidative and electrophilic stress. Cardiovas Toxicol. (2008) 8:71–85. doi: 10.1007/s12012-008-9016-0

32. Shramko, VS, Polonskaya, YV, Kashtanova, EV, Stakhneva, EM, and Ragino, YI. The short overview on the relevance of fatty acids for human cardiovascular disorders. Biomolecules. (2020) 10:1127. doi: 10.3390/biom10081127

33. He, M, Qin, C, Wang, X, and Ding, N. Plant unsaturated fatty acids: biosynthesis and regulation. Front Plant Sci. (2020) 11:390. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.00390

34. Hodson, L, and Gunn, PJ. The regulation of hepatic fatty acid synthesis and partitioning: the effect of nutritional state. Nat Rev Endocrinol. (2019) 15:689–700. doi: 10.1038/s41574-019-0256-9

35. Casals, N, Zammit, V, Herrero, L, Fadó, R, Rodríguez-Rodríguez, R, and Serra, D. Carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1c: From cognition to cancer. Prog Lipid Res. (2016) 61:134–48. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2015.11.004

36. Schlaepfer, IR, and Joshi, M. Cpt1a-mediated fat oxidation, mechanisms, and therapeutic potential. Endocrinology. (2020) 161:bqz046. doi: 10.1210/endocr/bqz046

37. Nakamura, M, Liu, T, Husain, S, Zhai, P, Warren, JS, Hsu, CP, et al. Glycogen synthase kinase-3α promotes fatty acid uptake and lipotoxic cardiomyopathy. Cell Metab. (2019) 29:1119–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.01.005

38. Zhu, X, Bian, H, Wang, L, Sun, X, Xu, X, Yan, H, et al. Berberine attenuates nonalcoholic hepatic steatosis through the ampk-srebp-1c-scd1 pathway. Free Radic Biol Med. (2019) 141:192–204. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2019.06.019

39. Ruiz, R, Jideonwo, V, Ahn, M, Surendran, S, Tagliabracci, VS, Hou, Y, et al. Sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1 (srebp-1) is required to regulate glycogen synthesis and gluconeogenic gene expression in mouse liver. J Biol Chem. (2014) 289:5510–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.541110

40. Zhao, Q, Lin, X, and Wang, G. Targeting SREBP-1-mediated lipogenesis as potential strategies for cancer. Front Oncol. (2022) 12:952371. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.952371

41. Legouis, D, Faivre, A, Cippà, PE, and De Seigneux, S. Renal gluconeogenesis: an underestimated role of the kidney in systemic glucose metabolism. Nephrol Dial Transplant. (2022) 37:1417–25. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfaa302

42. Theil, PK, Cordero, G, Henckel, P, Puggaard, L, Oksbjerg, N, and Sørensen, MT. Effects of gestation and transition diets, piglet birth weight, and fasting time on depletion of glycogen pools in liver and 3 muscles of newborn piglets. J Anim Sci. (2011) 89:1805–16. doi: 10.2527/jas.2010-2856

43. Theil, PK, Lauridsen, C, and Quesnel, H. Neonatal piglet survival: impact of sow nutrition around parturition on fetal glycogen deposition and production and composition of colostrum and transient milk. Animal. (2014) 8:1021–30. doi: 10.1017/S1751731114000950

44. Strakovsky, RS, Zhang, X, Zhou, D, and Pan, YX. Gestational high fat diet programs hepatic phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase gene expression and histone modification in neonatal offspring rats. J Physiol. (2011) 589:2707–17. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.203950

45. Wang, Z, and Dong, C. Gluconeogenesis in cancer: function and regulation of pepck, fbpase, and g6pase. Trends Cancer. (2019) 5:30–45. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2018.11.003

46. Kalhan, S, and Parimi, P. Gluconeogenesis in the fetus and neonate. Semin Perinatol. (2000) 24:94–106. doi: 10.1053/sp.2000.6360

Glossary

LZ - Lysozyme

BUN - Blood urea nitrogen

TG - Triglyceride

LDLC - Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol

HDL - High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol

TC - Total Cholesterol

β-actin - β-non muscle actin

PC - Pyruvate carboxylase

PEPCK1 - Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 1

PEPCK2 - Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 2

G6PC - Glucose 6-phosphatase

SREBP1 - Sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1

SCD - Stearoyl-CoA desaturase

CPT1α - Carnitine palmitoyl ltransferase1 α

PPARα - Peroxisomal Proliferator-activated Receptor α

FATP1 - Fatty acid transport protein 1

ACC - Acetyl-CoA Carboxylase

NQO1 - NADH quinone oxidoreductase 1

CAT - Catalase

Nrf2 - Nuclear factor E2-related factor 2

MnSOD - Mn Superoxide dismutase

Cu/ZnSOD - Cu/Zn-Superoxide Dismutase

HO-1 - Heme Oxygenase-1

GPX1 - Glutathione peroxidase 1

GPX4 - Glutathione peroxidase 4

T-AOC - Total antioxidant capacity

SOD - Superoxide dismutase

MDA - Malonaldehyde

Keywords: lysozyme (LZ), weaned piglet, lipid metabolism, glucose metabolism, antioxidant function

Citation: Wu Y, Zhang H, Zhang Y, Xie C and Chen G (2025) Lysozyme supplement enhances antioxidant capacity and regulates liver glucolipid metabolism in weaned piglets. Front. Vet. Sci. 12:1721300. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2025.1721300

Edited by:

Regiane R. Santos, Schothorst Feed Research, NetherlandsReviewed by:

Dongdong Lu, China Agricultural University, ChinaYang Gao, BaiCheng Normal University, China

Copyright © 2025 Wu, Zhang, Zhang, Xie and Chen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chunyan Xie, eGllLmNodW55YW5AZm94bWFpbC5jb20=; Guoshun Chen, Y2hlbmdzQGdzYXUuZWR1LmNu

Yuying Wu1

Yuying Wu1 Huihui Zhang

Huihui Zhang Yonggang Zhang

Yonggang Zhang Chunyan Xie

Chunyan Xie Guoshun Chen

Guoshun Chen