- The University of Electro-Communications, Department of Informatics, Chofu, Japan

The Hanger Reflex (HR) is a tactile illusion phenomenon in which involuntary head rotation occurs when a person wears a wire hanger on the head. This rotation is induced by skin deformation caused by pressure on the head, and can occur in multiple directions, including yaw, pitch, and roll. However, it has been reported that the Hanger Reflex tends to occur more easily along certain axes, while being less likely along others. To address this limitation, we propose a method to alter the direction of head rotation induced by the Hanger Reflex by simultaneously presenting optical flow (OF) stimuli. In our experiment, we presented optical flow stimuli with varying directions and phases while inducing the Hanger Reflex. As a result, we confirmed that the head rotation, which originally occurred primarily along the yaw axis due to the Hanger Reflex, could be shifted to the pitch or roll axis depending on the direction of the presented optical flow. Furthermore, compared to the condition using only the Hanger Reflex, the combined condition with optical flow and the Hanger Reflex produced 2.1 to 2.7 times more head rotation in the pitch and roll directions. These findings suggest that a Hanger Reflex-based device, originally limited to yaw-axis head rotation, can be repurposed as a head rotation actuator in arbitrary directions when combined with optical flow. This has potential applications in the design of VR content.

1 Introduction

The Hanger Reflex (HR) is a phenomenon in which wearing a wire hanger on the head causes involuntary head rotation (Matsue et al., 2008; Sato et al., 2009). This phenomenon occurs due to pressure applied at two points on the head, which leads to skin deformation. The direction of this deformation influences the resulting movement (Sato et al., 2014; Miyakami et al., 2018; 2022). Early studies on the Hanger Reflex primarily focused on head rotation around the yaw axis. However, subsequent research has reported that, in addition to yaw-axis rotation, movements around the pitch and roll axes can also be induced by lateral stretching of the skin (Kon et al., 2016; Kon et al., 2018).

Although several studies have explored tactile feedback displays based on skin deformation for navigation and interaction purposes (Aggravi et al., 2018; Nakamura and Kuzuoka, 2024; Lin et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2019; 2020; Shim et al., 2022), these approaches inherently require multiple actuators to achieve multi-degree-of-freedom feedback, which increases device size and complexity.

In contrast, the Hanger Reflex offers a particularly strong and direct method for inducing head motion, and because it relies on an illusion rather than mechanical actuation, it can be implemented in a compact form, making it a promising candidate for integration into haptic-enabled head-mounted displays (HMDs) (Kon et al., 2018; Li et al., 2022; Kon et al., 2017a).

That said, the intensity of Hanger Reflex-induced motion along the pitch and roll axes is generally weaker than that along the yaw axis and tends to exhibit greater individual variability. One possible approach to address this limitation is to combine the Hanger Reflex with other modalities. Previous research has shown that the magnitude of motion induced by the Hanger Reflex can be modulated by the interpretation of prior instructions or contextual information (Kon et al., 2017b). For instance, combined a wrist-mounted Hanger Reflex with electrical muscle stimulation (EMS) targeting forearm movement, using the Hanger Reflex to induce yaw-axis motion and EMS to control pitch-axis motion (Sakashita et al., 2019). However, EMS may be less socially acceptable, especially when applied around the head. Our approach is to combine the Hanger Reflex with visually induced self-motion, known as vection. Vection is an illusion of self-motion triggered by visual optical flow (OF) stimuli and can be accompanied by involuntary bodily movement. Although some studies have examined the integration of vection and tactile interfaces (Farkhatdinov et al., 2013; Murovec et al., 2021), these have primarily relied on vibratory tactile stimuli applied to the soles of the feet. In contrast, combining vection and the Hanger Reflex—both of which can be incorporated into an HMD—offers high potential for seamless and practical integration.

However, the challenge of presenting stable, multi-DoF pseudo-force and motion sensations with a compact mechanism in haptic-enabled HMDs remains unresolved. While the Hanger Reflex enables strong, compact yaw rotational induction, its effects on pitch and roll axes are comparatively weak. Optical-flow-based vection, on the other hand, can convey motion sensations in multiple directions, but its perceptual intensity and capability to imply force or physical motion remain limited. Therefore, there is still a strong demand for a lightweight, HMD-integrable method capable of expanding pseudo-force feedback across multiple DoFs in both intensity and directional expressiveness. To address this gap, this study systematically evaluates whether the visual–reflexive integration of the Hanger Reflex and optical-flow-induced vection can enhance the intensity and directional controllability of pseudo-force feedback.

In this study, we focused on the movement and intensity induced by the Hanger Reflex. We conducted experiments to investigate how perceptual responses are affected when optical flow stimuli presented via an HMD are overlaid with Hanger Reflex stimulation. We previously reported preliminary findings on the combined presentation of Hanger Reflex and optical flow in an extended abstract (Kon and Kajimoto, 2025). However, that work offered only a brief introduction to the concept and a small set of experimental results with minimal analysis. In contrast, the present paper provides the full experimental methodology, includes comprehensive quantitative analyses of both head motion and perception, and offers an in-depth discussion of multisensory interactions. This approach enables the simplest 1-DoF Hanger Reflex hardware to provide multi-degree-of-freedom (3-DoF) force and motion feedback.

2 Combined presentation system

2.1 Hanger reflex presentation

Based on a previous study that utilized air-driven balloons for Hanger Reflex induction (Kon et al., 2018), we developed a Hanger Reflex presentation device (Figure 1). The device consists of a rigid, oval-shaped aluminum shell that covers the entire circumference of the head and four air-actuated balloons. These balloons apply distributed pressure to the user’s head, thereby inducing the Hanger Reflex. The system incorporates a microcontroller (ESP32-DevKitC-32D, Espressif Systems), a pressure sensor (MIS-2503-015G, METRODYNE MICROSYSTEM CORP), an air pump (SC3701PML, SHENZHEN SKOOCOM ELECTRONIC), and solenoid valves (SC415GF, SHENZHEN SKOOCOM ELECTRONIC) to manage control and communication processes. The microcontroller operates at a refresh rate of 1.2 kHz, which includes sensing, actuation, and communication tasks. Sensor values obtained via ADC are stored in a ring buffer with a capacity of nine samples, and the median value is used for processing. Each air-driven balloon measures 40 mm

The air-driven balloons were actuated to reach a target pressure of 16.510 kPa as set in the microcontroller, and the pressure sensor responded within approximately 30 m at maximum. The Hanger Reflex was presented using the following Equation 1, defined in this study:

where

The actuation patterns of the four air-driven balloons are detailed in (Kon and Kajimoto, 2025). For example, actuating Balloons 3 and 4 located at the back of the head causes the head to tilt upward along the pitch axis. As another example, actuating Balloon 1 on the left side of the forehead and Balloon 4 on the right rear side of the head causes the head to rotate leftward along the yaw axis. These actuation patterns have been validated in previous studies (Kon et al., 2018; Kon and Kajimoto, 2025).

2.2 Optical flow presentation

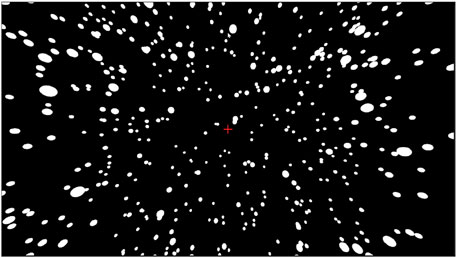

As shown in Figure 2, the optical flow stimuli were presented using a Head-Mounted Display (HMD). We randomly placed 2000 spheres, each with a diameter of 0.1 m, in the space surrounding the participant’s head at a distance ranging from 2.0 m to 5.0 m.

Figure 2. Screenshot of the Unity Editor screen. Participants were instructed to gaze at the red cross mark in the center of the screen.

The camera within this space was rotated according to the following Equation 2, defined in this study:

In the equation,

3 Experiment

This experiment aims to investigate the combined effects of the Hanger Reflex and optical flow. Specifically, we examined the influence of optical flow parameters, namely, direction and phase shift, on head rotation, perception, and the experience of VR sickness. A total of 11 participants (10 male, 1 female), aged between 21 and 24 years (mean age: 22), took part in the study. This experiment was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Electro-Communications, and informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to participation.

3.1 Experimental design and conditions

This study employed a factorial experimental design in which several independent variables related to Optical Flow (OF) and the Hanger Reflex (HR) were systematically manipulated. The variables included the presence or absence of Optical Flow, the direction of Optical Flow along the pitch, yaw, or roll axis, the initial phase of Optical Flow, the presence or absence of the Hanger Reflex, and the initial phase of the Hanger Reflex. The structure of these variables and the combinations that produced the individual experimental conditions are summarized in Table 1. By combining the levels of these variables, a total of thirty-nine distinct experimental conditions were generated, and each of these conditions was presented once, resulting in thirty-nine trials in total.

Table 1. The table shows combinations of Hanger Reflex and optical flow phase conditions. Optical flow phases are expressed in radians. OF(sin) and OF(cos) indicate sinusoidal and cosinusoidal optical flow patterns, respectively, while HR(sin) and HR(–sin) indicate the direction of head rotation induced by the Hanger Reflex. Red cells indicate conditions in which only the Hanger Reflex was presented, blue cells indicate conditions in which only optical flow was presented, and yellow cells indicate combined Hanger Reflex and optical flow conditions.

To organize the experiment, the conditions were grouped into three condition sets: an Optical Flow–only set, a Hanger Reflex–only set, and a combined Optical Flow and Hanger Reflex set. The Optical Flow set contained the baseline no-flow condition and all variations of direction and initial phase. The Hanger Reflex set contained the no-stimulation baseline and both initial-phase variations. The combined set consisted of all conditions in which Optical Flow and the Hanger Reflex were presented simultaneously. The order of these three condition sets was fixed so that participants first experienced the Optical Flow set, then the Hanger Reflex set, and finally the combined set, while the order of the trials within each set was randomized.

After each trial, participants reported the perceived direction of force (item A) and the perceived strength of the force (item B). In contrast, the evaluation of VR sickness (item C) was not conducted after every trial but only once at the end of each condition set. Accordingly, VR sickness was assessed three times in total: once after the completion of the Optical Flow set, once after the Hanger Reflex set, and once after the combined set. A simplified seven-point Likert scale was used for this purpose because administering a full Simulator Sickness Questionnaire after every trial would have been impractical given the large number of trials.

For the Optical Flow (OF) conditions, listed as “OF” in the table, the maximum rotation angle was set to 90°, the period to 10 s, and the presentation time to 30 s. Four initial phase (IP) conditions were used: 0,

Figure 3. Example of combined hanger reflex and optical flow stimulation used to investigate their interaction on head motion. Hanger Reflex:

As a result, the total number of conditions was 39, excluding overlapping conditions where no optical flow was presented in the OF conditions and no Hanger Reflex was presented in the HR conditions. Each condition was conducted once, resulting in a total of 39 trials. The experiment was conducted in the following order: Optical Flow conditions, Hanger Reflex conditions, and Combined (OFHR) conditions. This order was chosen to observe how participants, after becoming somewhat accustomed to the Hanger Reflex through earlier trials, would respond when it was combined with optical flow. The presentation order within each set of conditions was randomized. The participants were asked to respond to and evaluate the following items. Items A and B were assessed after each trial, while item C was assessed at the end of each condition.

3.1.1 Perceived direction of force

The participants were asked to indicate the direction of the force they perceived during the trial by selecting one or more from the options: None, PitchUp, PitchDown, YawRight, YawLeft, RollRight, RollLeft. For example, PitchUp refers to a rotation around the pitch axis that causes the face to tilt upward. Note that they were allowed to choose multiple options, and if they perceived right and left rotation along yaw axis, they responded by choosing YawRight and YawLeft.

3.1.2 Perceived intensity of force

The participants were asked to rate the strength of the force they perceived during the trial by 7-point Likert scale (1: did not feel anything, 7: felt extremely strong).

3.1.3 VR sickness

The participants were asked to indicate the current intensity of VR-induced sickness using a 7-point Likert scale (1: no sickness at all, 7: extremely strong feeling of sickness). This measure was used as a preliminary and simplified assessment, since the large number of trials made it difficult to administer a comprehensive evaluation after each trial. Although the Simulator Sickness Questionnaire (SSQ) would have been more appropriate for a full assessment, it was not feasible to administer it repeatedly during the experiment.

During the experiment, participants wore the Hanger Reflex device, the HMD, and canal-type earphones, and were seated on a non-rotating chair. They were instructed to maintain a natural posture and not to resist any sensations of force or movement they might experience during the trials. White noise was played through the earphones throughout the experiment to mask environmental sounds.

After each trial, participants were asked to return their head to a forward-facing position and answered items A and B. Head rotation angles were measured using the head-tracking functionality of the HMD. After completing one set of trials for the Optical Flow conditions, the Hanger Reflex conditions, or the Combined conditions, they were asked to complete the assessment regarding VR sickness. Thus, the VR sickness assessment was administered three times in total.

3.2 Experimental results

3.2.1 Perceived direction of force

Tables 2–4 summarize the participants’ responses regarding the perceived direction of force under three conditions: Hanger Reflex only, optical flow only, and the combination of optical flow and Hanger Reflex.

Table 2. Response rate for perceived direction of force when only the Hanger Reflex was presented. Values indicate the percentage of trials classified into each perceived direction category. IP denotes the initial phase of the Hanger Reflex stimulus, expressed in radians. Red cells indicate the dominant perceived direction under each phase condition.

Table 2 shows the response rates for perceived direction of force when only the Hanger Reflex was presented. In the “None” condition, where no Hanger Reflex was applied, 100% of responses indicated “None” as the perceived force. In conditions where the Hanger Reflex was presented with an initial phase of IP = 0 or IP =

Table 3. Response rate for perceived direction of force for optical flow-only conditions. Values indicate the percentage of trials classified into each perceived direction category. The optical flow axis indicates the axis along which visual motion was presented. Red cells indicate the dominant perceived direction for each optical flow axis condition.

Table 4. Response rate for perceived direction of force when optical flow along the pitch, yaw, and roll axes was presented in combination with yaw-axis Hanger Reflex. Values indicate the percentage of trials classified into each perceived direction category. The optical flow axis indicates the axis along which visual motion was presented. Red cells indicate the dominant perceived direction under each condition.

3.3 Received intensity of force

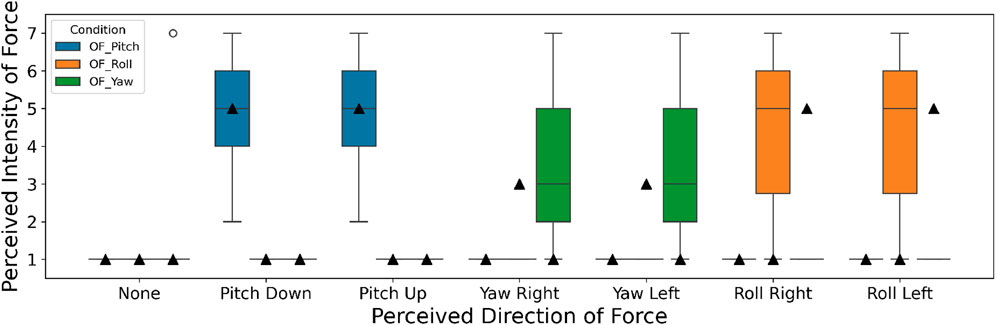

Figures 4–6 summarize the participants’ responses regarding the perceived intensity of force under three conditions: Hanger Reflex only (HR), optical flow only (OF), and the combination of optical flow and Hanger Reflex (OFHR).

Figure 4 shows the results for the perceived intensity of force when only the Hanger Reflex was presented. In the condition with initial phase IP = 0, the average scores were 6 for “Yaw Right” and 5 for “Yaw Left.” In the condition with IP =

Figure 6. Results of perceived intensity of force when optical flow along the pitch, yaw, and roll axes was presented in combination with yaw-axis Hanger Reflex.

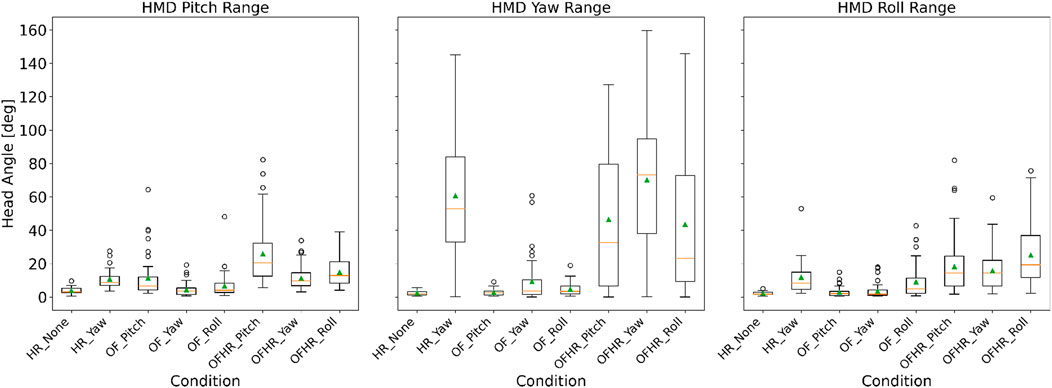

3.4 Change of head orientation

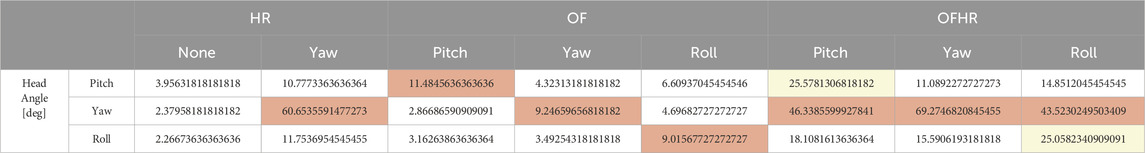

During the 30-s presentation period, three cycles of head movement occurred. The amount of head orientation change during this motion was measured. For example, in the case of rotational movement around the yaw axis (i.e., turning the head left and right), the difference between the maximum leftward and rightward rotation angles was defined as the head orientation change along the yaw axis (e.g., 30° to the right and 30° to the left would result in a 60-degree change). The average measured head angles are shown in Table 5. In the HR-None condition, where no Hanger Reflex was presented, the average change in head orientation was less than 4° for all axes (pitch, yaw, and roll). In the HR-Yaw condition, where yaw-axis Hanger Reflex was presented, the change in head orientation was approximately 60°. In the condition where optical flow was presented along the pitch axis, the head movement along the pitch axis was the largest, averaging approximately 11.5°. When optical flow was presented along the yaw axis, the largest movement occurred along the yaw axis at approximately 9.2°. For optical flow along the roll axis, the largest movement was observed along the roll axis, averaging approximately 9.0°. When yaw-axis Hanger Reflex was combined with optical flow along the pitch axis, the average head movement was approximately 46° along the yaw axis and 25° along the pitch axis. When yaw-axis Hanger Reflex was combined with optical flow along the yaw axis, the yaw-axis movement increased to approximately 69°. When combined with optical flow along the roll axis, the average head movement was approximately 43° along the yaw axis and 25° along the roll axis.

Table 5. Average head rotation angle for each experimental condition. Values represent the mean head rotation angle in degrees for the pitch, yaw, and roll axes. Columns indicate stimulation conditions, including Hanger Reflex only, optical flow only, and combined optical flow and Hanger Reflex conditions.

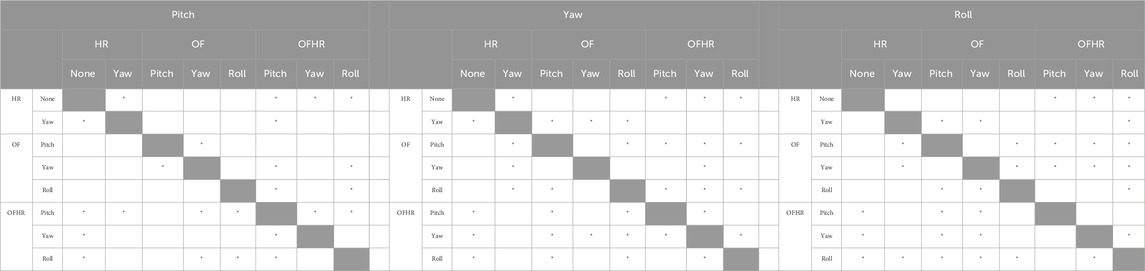

The measured average head angles are shown in Figure 7. The horizontal axis of the graph represents the amplitude of head movement (in degrees) along the pitch, yaw, and roll axes for each of the eight conditions listed in Table 6. According to the Shapiro–Wilk test for normality, no normal distribution was observed for pitch-axis head angles in any condition except HR_None. For yaw-axis head angles, normality was not confirmed in any condition except HR_None, HR_Yaw and OFHR_Yaw. For roll-axis head angles, normality was not confirmed in any condition except HR_None. A Friedman test revealed significant differences across conditions for all three axes (pitch, yaw, and roll) (p < 0.001). Table 6 summarizes the results of post hoc multiple comparisons using Wilcoxon signed-rank tests with holm correction. For the pitch axis, the OFHR_Pitch condition—where yaw-axis Hanger Reflex was combined with pitch-axis optical flow—showed a significant difference compared to all other conditions. For the yaw axis, the OFHR_Yaw condition—where yaw-axis Hanger Reflex was combined with yaw-axis optical flow—showed a significant difference compared to all conditions except HR_Yaw. For the roll axis, the OFHR_Roll condition—where yaw-axis Hanger Reflex was combined with roll-axis optical flow—showed a significant difference compared to all conditions except HR_Yaw, OFHR_Pitch, and OFHR_Yaw.

3.5 VR sickness

A preliminary analysis of VR-induced sickness was conducted using the simplified 7-point Likert scale. A Friedman test revealed a significant difference among the three condition sets (p = 0.0126). Post-hoc Wilcoxon signed-rank tests with Bonferroni correction indicated significant differences between the Hanger Reflex condition and the optical flow condition (p = 0.01), as well as between the Hanger Reflex condition and the combined condition (p = 0.03). No significant difference was found between the optical flow and combined conditions (p = 0.55). Given that this assessment was preliminary and used a simplified measure, these findings should be interpreted with caution.

4 Discussion

4.1 Perceived force intensity and direction

Consistent with prior findings, the participants clearly perceived force along the yaw axis under conditions that induced the Hanger Reflex around the yaw axis. When optical flow was presented along the pitch, yaw, or roll axis, they reported feeling force aligned with the corresponding axis of motion. In contrast, when the yaw-axis Hanger Reflex was combined with optical flow along any of the three axes, they most clearly perceived force in the direction of the optical flow, with the yaw-axis force also perceived additionally. In other words, when combining the Hanger Reflex with optical flow, the direction of perceived force was primarily dominated by the optical flow, with the Hanger Reflex force direction being additive.

4.2 Direction and magnitude of head rotation

Table 7 summarizes the magnitude ratios of head rotation angles. For both OF (optical flow only) and OFHR (combined) conditions, only the head rotation angles in the direction of optical flow presentation were extracted. The first three columns on the left show the average rotation angles under OF, HR (Hanger Reflex only), and OFHR conditions, respectively. The two columns on the right show the ratios of OFHR to OF, and OFHR to HR, respectively. As shown in Table 7, when optical flow was presented in combination with the Hanger Reflex, the head rotation in the direction of the optical flow was consistently enhanced compared to the Hanger Reflex alone. This effect was particularly pronounced in the pitch and roll axes, where the rotation was more than twice as large. Similarly, compared to head movement induced by optical flow alone, the combination with the Hanger Reflex always resulted in greater rotation in the direction of the optical flow, again especially along the pitch and roll axes, where the increase was more than twofold.

Table 7. Multiplicative increase in head rotation angle in the OFHR condition compared to the OF and HR conditions.

These results indicate that the combination of optical flow and Hanger Reflex stimulation enhances head rotation in the direction of the optical flow. This suggests the possibility of controlling the direction of motion induced by the Hanger Reflex using optical flow. One key advantage of this approach is that it enables generation of motion along axes other than yaw by leveraging the high induction rate and strong movement produced by the yaw-axis Hanger Reflex. Using only a yaw-axis Hanger Reflex device simplifies the mechanical structure and control mechanisms required for stimulation. Furthermore, because the system relies solely on head-mounted devices—the Hanger Reflex device and HMD—this approach supports compact and efficient head posture control.

4.3 VR sickness

Experimental results indicated that combining optical flow with the Hanger Reflex did not lead to a significant increase in VR sickness. Although the VR sickness scores in the OFHR condition were higher than those in the OF condition, this may be attributed to the order of presentation and the number of trials due to the experimental design. Since the OFHR condition was conducted last, participants may have experienced fatigue. Additionally, the OFHR condition involved twice as many trials as the OF condition. To more accurately assess VR sickness, it would be necessary to randomize the presentation order of the OF, HR, and OFHR conditions and collect subjective VR sickness ratings after each trial.

To more accurately assess VR sickness, it would be necessary to randomize the presentation order of the OF, HR, and OFHR conditions and collect subjective VR sickness ratings after each trial. In addition, the use of a standardized measure such as the Simulator Sickness Questionnaire (SSQ) (Kennedy et al., 1993) would be required for a more reliable assessment. Although we initially expected that adding haptic feedback would help mitigate VR sickness (Shin et al., 2025), our results did not support this assumption. Furthermore, previous studies have reported changes in vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR) gain when the Hanger Reflex is applied (Takahashi and Johkura, 2022), suggesting that the altered interpretation of visual information may have influenced participants’ VR sickness responses.

5 Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the experiment was conducted without accounting for the latency of the Hanger Reflex and optical flow stimuli, and no timing calibration was performed. As a result, we were unable to evaluate the influence and effects of phase differences based on participants’ perception. Future work should include conditions that consider stimulus latency to more precisely examine the interactions between the two modalities. Second, the experiment was conducted using only a limited set of parameters. Further investigation is needed to explore the interaction effects when varying common parameters such as amplitude, frequency, waveform, and period. For example, by conducting experiments that manipulate amplitude, it may be possible to identify the threshold at which head movements induced by the Hanger Reflex begin to influence perception in the direction of optical flow.

Third, this study used a simplified 7-point Likert scale to assess VR-induced sickness instead of the standard Simulator Sickness Questionnaire (SSQ). Because the experiment included a large number of trials, it was impractical to administer the SSQ repeatedly, and therefore only a preliminary assessment of VR sickness was conducted three times (once for each condition set). As a result, the evaluation of VR sickness in this study may lack the sensitivity and diagnostic depth provided by the full SSQ.

Finally, a significant limitation of this study is the participant demographics. The experiment involved only 11 participants (10 male, 1 female), which is a small sample size exhibiting extreme gender bias. Furthermore, the participants were limited to a narrow age range of young adults (21–24 years old). This sample composition does not represent a typical distribution in perceptual research and thus markedly limits the generalizability of our findings. It is known that individual differences exist in the perception of illusions such as the Hanger Reflex and vection, and the susceptibility to these phenomena may vary across different populations, including by gender or age. Therefore, it is essential to verify whether the effects confirmed in this study—namely, the shifting of the rotation axis and the enhancement of rotation magnitude by combining yaw-axis Hanger Reflex with optical flow—are applicable to a more diverse population. Future studies must address this limitation by recruiting a larger and more diverse sample, balanced for gender and age, to confirm the robustness and validity of this method.

6 Conclusion

In this study, we demonstrated that combining the Hanger Reflex with optical flow stimuli can induce head rotation in the direction of the optical flow, even when the initial motion is triggered by the Hanger Reflex. We also showed that both the perceived direction and intensity of force were similarly influenced by the direction of the optical flow. Compared to conditions with optical flow alone or Hanger Reflex alone, the combined condition resulted in more than double the head movement, particularly along the pitch and roll axes. Potential applications of this method for force and motion presentation include the following. First, integration into head-mounted displays (HMDs) could enhance the VR content experience. By incorporating a yaw-axis Hanger Reflex mechanism, it is possible to induce natural head movements synchronized with VR visuals, thereby amplifying the perceived force and contributing to a more immersive user experience. Second, the method may enhance real-world experiences. For example, when combined with amusement rides such as roller coasters, it could generate natural head movements and intensified force perception synchronized with the actual visual experience, resulting in heightened realism. Similarly, when paired with 4DX digital theaters, this approach could enable natural head motion in sync with movie content, while minimizing the required movement of theater seats and their mechanical complexity—potentially improving the cinematic experience with more compact systems. In future work, we plan to investigate additional parameters beyond phase difference and conduct more detailed analyses focusing on the latency and timing between Hanger Reflex induction, optical flow presentation, and resulting head movements.

7 Nomenclature

7.1 Resource identification initiative

To take part in the Resource Identification Initiative, please use the corresponding catalog number and RRID in your current manuscript. For more information about the project and for steps on how to search for an RRID, please click here.

7.2 Life Science Identifiers

Life Science Identifiers (LSIDs) for ZOOBANK registered names or nomenclatural acts should be listed in the manuscript before the keywords. For more information on LSIDs please see Inclusion of Zoological Nomenclature section of the guidelines.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the ethics committee of the University of Electro Communications. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

YK: Writing – original draft. HK: Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank all individuals who generously dedicated their time to participate in this study. Their insightful feedback was essential for developing and validating the findings presented in this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. The author declares that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript to enhance the quality.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:HR, Hanger Reflex, A tactile illusion causing involuntary head rotation by pressure on the head; OF, Optical Flow, Visual motion pattern that induces a sense of self-motion (vection); OFHR, Combined Optical Flow and Hanger Reflex condition, Combination condition of HR and OF stimuli; HMD, Head-Mounted Display, Device for presenting visual stimuli in virtual reality; IP, Initial Phase, Parameter controlling the phase shift of the sine-wave stimulus;

References

Aggravi, M., Pausé, F., Giordano, P. R., and Pacchierotti, C. (2018). Design and evaluation of a wearable haptic device for skin stretch, pressure, and vibrotactile stimuli. IEEE Robotics Automation Lett. 3, 2166–2173. doi:10.1109/LRA.2018.2810887

Farkhatdinov, I., Ouarti, N., and Hayward, V. (2013). “Vibrotactile inputs to the feet can modulate vection,” in 2013 world haptics conference (WHC), 677–681. doi:10.1109/WHC.2013.6548490

Kennedy, R. S., Lane, N. E., Berbaum, K. S., and Lilienthal, M. G. (1993). Simulator sickness questionnaire: an enhanced method for quantifying simulator sickness. Int. J. Aviat. Psychol. 3, 203–220. doi:10.1207/s15327108ijap0303_3

Kon, Y., and Kajimoto, H. (2025). “Preliminary investigation of the effects of combining hanger reflex and optical flow,”, 25. Ext. Abstr. CHI Conf. Hum. Factors Comput. Syst. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, 1–6. doi:10.1145/3706599.3720025

Kon, Y., Nakamura, T., Sato, M., Asahi, T., and Kajimoto, H. (2016). “Hanger reflex of the head and waist with translational and rotational force perception,” in AsiaHaptics 2016. vol. 432 of lecture notes in electrical engineering. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-4157-0_38

Kon, Y., Nakamura, T., and Kajimoto, H. (2017a). “Hangerover: Hmd-embedded haptics display with hanger reflex,” in ACM SIGGRAPH emerging technologies. doi:10.1145/3084822.3084842

Kon, Y., Nakamura, T., and Kajimoto, H. (2017b). “Interpretation of navigation information modulates the effect of the waist-type hanger reflex on walking,” in 2017 IEEE symposium on 3D user interfaces (3DUI) (Los Angeles, CA, USA), 107–115. doi:10.1109/3DUI.2017.7893326

Kon, Y., Nakamura, T., Yem, V., and Kajimoto, H. (2018). “Hangerover: mechanism of controlling the hanger reflex using air balloon for hmd embedded haptic display,” in IEEE VR 2018. doi:10.1109/VR.2018.8446582

Li, W., Nakamura, T., and Rekimoto, J. (2022). “Remoconhanger: making head rotation in remote person using the hanger reflex,” in Adjunct proceedings of the 35th annual ACM symposium on user interface software and technology (UIST ’22 adjunct) (New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery), 1–3. doi:10.1145/3526114.3558700

Lin, Y., Zhang, P., Ofek, E., and Je, S. (2024). “Armdeformation: inducing the sensation of arm deformation in virtual reality using skin-stretching,” in Proceedings of the 2024 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems (CHI ’24) (New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery), 1–18. doi:10.1145/3613904.3642518

Matsue, R., Sato, M., Hashimoto, Y., and Kajimoto, H. (2008). “Hanger reflex – a reflex motion of a head by temporal pressure for wearable interface,” in SICE annual conference, 1463–1467doi. doi:10.1109/SICE.2008.4654889

Miyakami, M., Kon, Y., Nakamura, T., and Kajimoto, H. (2018). “Optimization of the hanger reflex (i): examining the correlation between skin deformation and illusion intensity,” in Haptics: science, technology, and applications, 36–48. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-93445-7_4

Miyakami, M., Takahashi, A., and Kajimoto, H. (2022). Head rotation and illusory force sensation by lateral skin stretch on the face. In Front. Virtual Real. 3:930848. doi:10.3389/frvir.2022.930848

Murovec, B., Spaniol, J., Campos, J. L., and Keshavarz, B. (2021). Multisensory effects on illusory self-motion (vection): the role of visual, auditory, and tactile cues. Multisensory Res. 34, 869–890. doi:10.1163/22134808-bja10058

Nakamura, T., and Kuzuoka, H. (2024). Rotational motion due to skin shear deformation at wrist and elbow. IEEE Trans. Haptics 17, 108–115. doi:10.1109/TOH.2024.3362407

Sakashita, S., Satoshi, H., and Yoichi, O. (2019). “Wrist-mounted haptic feedback for support of virtual reality in combination with electrical muscle stimulation and hanger reflex,” in HCII 2019: human-computer interaction. Recognition and interaction technologies (Springer International Publishing). doi:10.1007/978-3-030-22643-5_43

Sato, M., Matsue, R., Hashimoto, Y., and Kajimoto, H. (2009). “Development of a head rotation interface by using hanger reflex,” in IEEE international symposium on robot and human interactive communication, 534–538. doi:10.1109/ROMAN.2009.5326327

Sato, M., Nakamura, T., and Kajimoto, H. (2014). “Movement and pseudohaptics induced by skin lateral deformation in hanger reflex,” in The 5th workshop on telexistence.

Shim, Y. A., Kim, T., and Lee, G. (2022). “Quadstretch: a forearm-wearable multi-dimensional skin stretch display for immersive vr haptic feedback,” in Extended abstracts of the 2022 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems (CHI EA ’22) (New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery), 1–4. doi:10.1145/3491101.3519908

Shin, H., Shimizu, Y., Kim, H., Sawabe, T., and Kim, G. J. (2025). “Mitigating cyber and motion sickness with haptic and visual feedback for vr users in autonomous vehicle,” in Proceedings of the extended abstracts of the CHI conference on human factors in computing systems (CHI EA ’25) (New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery), 1–9. doi:10.1145/3706599.3720076

Takahashi, K., and Johkura, K. (2022). Vestibulo-ocular reflex gain changes in the hanger reflex. Elsevier 438, 120277. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2022.120277

Wang, C., Huang, D.-Y., wen Hsu, S., Hou, C.-E., Chiu, Y.-L., Chang, R.-C., et al. (2019). “Masque: exploring lateral skin stretch feedback on the face with head-mounted displays,” in Proceedings of the 32nd annual ACM symposium on user interface software and technology (UIST ’19) (New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery), 439–451. doi:10.1145/3332165.3347898

Wang, C., Huang, D.-Y., Hsu, S.-W., Lin, C.-L., Chiu, Y.-L., Hou, C.-E., et al. (2020). “Gaiters: exploring skin stretch feedback on legs for enhancing virtual reality experiences,” in Proceedings of the 2020 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems (CHI ’20) (New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery), 1–14. doi:10.1145/3313831.3376865

Keywords: hanger reflex, head-mounted display, multisensory interaction, opticalflow, perceived self-motion

Citation: Kon Y and Kajimoto H (2026) Combination of hanger reflex and optical flow enhances head rotation and influences its direction. Front. Virtual Real. 6:1685366. doi: 10.3389/frvir.2025.1685366

Received: 13 August 2025; Accepted: 17 December 2025;

Published: 08 January 2026.

Edited by:

Myunghwan Yun, Seoul National University, Republic of KoreaReviewed by:

Arnulph Fuhrmann, Technical University of Cologne, GermanyGary Li-Kai Hsiao, National Taiwan University of Science and Technology, Taiwan

Namgyun Kim, Texas A&M University San Antonio, United States

Copyright © 2026 Kon and Kajimoto. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yuki Kon, a29uQGthamktbGFiLmpw

Yuki Kon

Yuki Kon Hiroyuki Kajimoto

Hiroyuki Kajimoto