- Research in User eXperience (RUX) Laboratory, Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, Department of Human Factors and Behavioral Neurobiology, Daytona Beach, FL, United States, Daytona Beach, FL, United States

Augmented Reality (AR) technologies hold tremendous potential across various domains, yet their inconsistent design and lack of standardized user experience (UX) pose significant challenges. This inconsistency hinders user acceptance and adoption and impacts application design efficiency. This study describes the development of a validated UX heuristic checklist for evaluating AR applications and devices. Building upon previous work, this research expands upon this checklist through expert feedback, validation with heuristic evaluations, and user tests with five diverse AR applications and devices. The checklist was refined to 12 heuristics and 109 items and integrated into a single auto-scored Excel spreadsheet toolkit. This validated toolkit, named the Derby Dozen, empowers practitioners to evaluate AR experiences, quantify results, and ultimately inform better design practices, promoting greater usability and user satisfaction.

1 Introduction

The concepts of extended reality (XR), augmented reality (AR), and mixed reality (MR) are not novel, with definitions dating back to 1968 (Sutherland, 1968). However, the technology has advanced rapidly since. AR technologies of the early 1970s–2000s, differ significantly from contemporary iterations (Caudell and Mizell, 1992; Milgram and Kishino, 1994). Along with the technology, the terminology associated with XR has changed. Rauschnabel et al. (2022) describe an updated framework for XR, AR, and VR. They define XR as “xReality”, an umbrella term in which “x” is a placeholder for any form of reality, including AR and VR, which does not extend the physical world. AR integrates real and virtual content in real-time, where the real world is a visible and integral part of the user experience. VR, conversely, immerses the user entirely within a computer-generated world, excluding the real environment from the experience. Within the AR spectrum, a further distinction is made between Mixed Reality (MR) and assisted reality. On one end of the spectrum, MR represents an integration of real and virtual elements, while at the opposite end lies assisted reality, which is characterized by overlays and digital information superimposed onto the real world, creating a less immersive but informational experience. Reported use cases for AR solutions are wide-ranging, including navigation, remote assistance, situation awareness, simulation, virtual user interface, visualization, maintenance, guidance, collaboration, and inspection (Apple Inc, 2020). This paper focuses on the evaluation of AR applications (assisted reality to mixed reality) and devices, specifically.

1.1 Heuristic evaluation and AR

Despite the progress in technology and the proliferation of AR applications, a consensus on best practices for design remains to be established. While researchers have developed internal guidelines, a lack of validated usability heuristics applicable across diverse devices and applications persists. The method of heuristic evaluation offers an efficient complement to user testing, enabling professionals to evaluate applications or devices from a best-practice perspective, even in early prototyping stages. Heuristic evaluations provide designers and developers with a foundation for iterative design improvements, enhancing usability and user experience. The most common set of heuristics for product evaluation is Nielsen’s 10 Usability Heuristics (Nielsen, 1994). While useful, these heuristics provide a general level of evaluation and do not always allow the evaluator to examine more detailed interactions that may be specific to the technology. Therefore, the development of a comprehensive set of AR usability heuristics is crucial for evaluating this technology.

Recent literature that explores the development of AR heuristics reveals several attempts to establish a common set of heuristics for immersive environments based on Nielsen’s 10, the technology acceptance model, and human cognitive processing (Sumithra et al., 2024), for both AR and VR environments (Mohammad and Pedersen, 2022; Omar et al., 2024), but no validated heuristic checklists for a wide range of AR applications and devices specifically. Sumithra et al. (2024) integrated components from the Technology Acceptance Model, Nielsen’s heuristics, and the Software Usability Measurement Inventory to produce a checklist based on the theory of Norman’s cognitive processing model. Similarly, Omar et al. (2024) compiled 52 metaverse-specific heuristics by merging multiple existing checklists originally developed for mobile, AR, VR, and virtual worlds, including work by Sutcliffe and Gault (2004), Endsley et al. (2017), Rusu et al. (2011), and Mohammad and Pedersen (2022). Nishchyk et al. (2024) followed a similar pattern in their elderly-centered AR heuristics, using Derby and Chaparro (2022) and validation methods from Quiñones et al. (2018). Other heuristic checklists target specific AR use cases, such as wearable VR educational applications (Othman et al., 2025) or mobile AR design (Szentirmai and Murano, 2023), primarily derived from pre-existing heuristic principles rather than introducing an original set of items grounded in AR’s unique interactions. Lima and Hwang (2024) further reinforce this gap by showing how heuristic type and evaluator traits can significantly influence usability outcomes, emphasizing the importance of standardized, validated tools.

This widespread reliance on adapted checklists, while valuable, stresses the ongoing quest to establish a rigorously validated, standalone heuristic evaluation checklist designed specifically for AR applications and devices. The lack of a thoroughly validated heuristic evaluation checklist poses challenges for AR application developers, particularly those targeting multiple device types such as mobile devices and head-mounted displays (HMDs).

Work by Derby and Chaparro (2022) attempted to fill this gap by creating a heuristic checklist comprising 11 heuristics and 94 items. This checklist was developed using a comprehensive and rigorous eight-step methodology for heuristic checklist development and validation (Quiñones et al., 2018). This methodology includes an in-depth analysis of the current literature within the domain, mapping activities to connect UX and usability issues with existing heuristics to identify current gaps, formal definitions to new heuristics, validation of the newly defined heuristics (by expert reviewers, heuristic evaluations, and comparing results to findings from usability studies), and refinement based on the results from the validation. The 11 heuristic categories included: Unboxing & Set-up, Help & Documentation, Cognitive Overload, Integration of Physical & Virtual Worlds, Consistency & Standards, Collaboration, Comfort, Feedback, User Interaction, Recognition Rather than Recall, and Device Maintainability. Despite the thorough development process, a limitation of this work was that only two AR applications (a puzzle game and a human anatomy application) and 3 devices (2 AR headset types and a mobile device) were used in the validation. Given the breadth of use cases prevalent today, the authors suggested the need for further iteration and refinement to explore critical usability considerations across a broader range of applications and devices.

2 Purpose

The purpose of this study was to expand and revalidate the Derby and Chaparro AR/MR Heuristic Checklist (2022) for AR device and application evaluation to ensure that it is valid for a wider breadth of AR hardware and use cases.

3 Method

The authors followed the Quiñones et al.’s 8-step methodology to create and validate usability/UX heuristics (Quiñones et al., 2018). Step 1: Exploratory was a literature review, conducted to evaluate the current literature about the AR domain, features, UX attributes, and existing heuristics. Step 2: Experimental was an analysis of the previous usability evaluations discovered in the literature to identify critical elements of AR that have been shown to impact its usability. In Step 3: Descriptive, the researchers selected and prioritized the information found in the previous steps. In Step 4: Correlational, features found in the previous steps were mapped to existing UX attributes and heuristics. In Step 5: Selection, if step 4 resulted in mapped heuristics, they were kept or adapted. If features did not map to existing heuristics, heuristics were either added or discarded as a result. This mapping enabled formalized definitions of the experimental heuristic checklist in Step 6: Specification. This experimental heuristic checklist was then validated on its effectiveness and efficiency through: 1) expert judgements by experts in the AR domain, 2) heuristic evaluations conducted on specified applications, and 3) a comparison of the heuristic evaluation results with user testing results of the same applications. Finally, in Step 8: Refinement, the experimental heuristics were refined and improved based on the validation results in Step 7.

4 Results

The authors completed all of the 8 steps in Quiñones et al.’s methodology (Quiñones et al., 2018). The results from these steps are described in four sections: exploring the literature, defining heuristics, heuristic validation, and heuristic refinement.

4.1 Steps 1–4: exploring the literature to establish possible heuristics

In steps 1-4, an exploration and analysis of the literature was completed to understand the current state of AR research. The researchers identified current design guidelines, definitions, and results from usability studies and experiments in the domain. The literature from Derby and Chaparro’s previous work (2022) and articles found from the following search terms were included: (1) Heuristics AND (AR OR MR), (2) Privacy AND (AR OR MR), (3) Privacy AND (AR OR MR) AND Multi-User, (4) Collaboration AND (AR OR MR) AND UX, (5) Cybersickness AND (AR OR MR), (6) Motion sickness AND (AR OR MR). The terms AR and MR were used due to evolving definitions, resulting in similar technologies being identified with both “AR” and “MR” signifiers. These technologies identified in this literature search were verified as “AR” according to the updated framework by Rauschnabel et al. (2022).

As a result of steps 1–4, 10 design guidelines, and 42 user studies, experiments, and review articles were identified in addition to the articles that were used in the previous iteration of the heuristic checklist (Derby and Chaparro, 2022). These newly discovered articles focused more deeply on UX principles related to user privacy, collaborative apps, physiological risks, and ethics than the previous iteration of the heuristic checklist defined. For example, many of these articles identified the importance of keeping private content when in collaborative spaces, privacy and transparency when collecting user data, and aspects that contribute to sickness (e.g., heat, eye strain, manipulation of 3D content, etc.). These principles were prioritized and correlated with existing heuristics (Derby and Chaparro, 2022). It was determined that the current heuristic lists did not sufficiently evaluate the AR domain, and it was necessary to continue with a new set of heuristics.

4.2 Steps 5–6: defining the set of heuristics

A set of experimental heuristics was created and defined with the goal of covering the gaps identified in the previous steps. A heuristic ID, priority value, name, definition, explanation, application feature, examples of violations and compliance with the heuristics, benefits gained when the heuristic is satisfied, anticipated problems of heuristic misunderstanding, the checklist items, and usability/UX attributes were mapped to each heuristic.

This current work expanded upon the existing heuristic checklist (Derby and Chaparro, 2022). The existing heuristic checklist was used as a base, and changes were made based on the findings from steps 1–4. A total of 49 changes were made (2 checklist items eliminated, 13 checklist items added, and 34 checklist items rephrased), yielding an experimental heuristic checklist with 11 heuristics and 105 checklist items.

4.3 Step 7: validation

To validate the experimental heuristics, a series of expert judgements, heuristic evaluations, and user tests were performed. All three of the validation procedures suggested by Quiñones et al. were conducted to provide a holistic evaluation of the experimental heuristics (2018). Expert judgements allowed the researchers to gather feedback about the utility, clarity, and ease of use of the heuristic checklist based on experts’ experience in the domain. Heuristic evaluations allowed the researchers to assess the effectiveness of the experimental heuristics. User tests allowed the researchers to assess how many similar usability issues were found between this method and the experimental heuristics.

4.3.1 Expert evaluations

First, expert judgements were conducted by five experts in the AR field, unfamiliar with the original Derby and Chaparro (2022). These experts were chosen because they were currently designing AR or MR applications within their companies. Their backgrounds represented a range of industries including defense, technology, and social media. These experts were provided a copy of the experimental heuristic checklist and were asked to evaluate one application with the device of their choosing, at their own pace. The applications that experts chose were later categorized into four application types: educational, games, entertainment, navigation, and training applications. Depending on the application that they chose, experts either used the Meta Quest Pro, HoloLens 2, T-45 MR simulator, or a mobile phone. Evaluators provided feedback on the checklist by leaving comments in the excel spreadsheet. These comments provided feedback on its utility, clarity, ease of use, necessity, importance, completeness, and intention to use it in the future. The researchers of this study used a thematic analysis technique to find patterns in the evaluator’s comments.

The expert evaluators scored the experimental heuristic checklist positively and found that the heuristics were easy to use, mostly complete, and useful. They stated that they would use it again in the future to evaluate AR apps. The most useful heuristics were reported to be Unboxing & Set-Up, Cognitive Overload, and User Interaction. Experts stated that the items in these categories required them to think critically about their applications in a way they had not considered initially. The heuristics of Help & Documentation, Cognitive Overload, Consistency & Standards, and Comfort were also reported to be critical to the overall usability of an AR application. The experts provided feedback that led to changes. For example, Expert 2 stated that an addition should be made to “Include an example about authentication and general usage in secure corporate environments (privacy) - e.g., ability to password protect, have different user accounts, work offline,” which resulted in the creation of the Privacy heuristic. A total of 19 changes were made to the experimental heuristics from this stage.

4.3.2 Heuristic evaluations

After these changes were made, heuristic evaluations were completed using the experimental heuristics and a competing set of control heuristics (de Paiva Guimarães and Martins, 2014) for comparison. Experienced researchers were randomly assigned one of the heuristic sets to conduct a heuristic evaluation for five distinct applications and devices (Figure 1). These included: 1) Local applications on the Epson Moverio BT-300, 2) Wayfair Spaces on the Magic Leap 1, 3) Fan Blade Replacement Training on the Magic Leap 2, 4) ShapesXR on the Meta Quest Pro, and 5) Google Maps Live View on a mobile phone. These were chosen due to their distinct differences in use case, representation in industry, physical form factor, application type (e.g., markerless, marker-based, or location-based), amount of movement involved by the user, input devices, and collaborative capabilities. Each of these devices also differed in their form factors, which contribute to user comfort levels. For example, the Meta Quest Pro was a head-mounted display that used video passthrough technology and required the use of controllers for its application, whereas the Epson Moverio BT-300 was a lightweight ocular see-through device designed similarly to eyeglasses, and the mobile phone did not require a head-mounted device. A description of these applications is described in Table 1. The researchers’ aim was to validate across a breadth of AR applications and devices to ensure that the new experimental heuristic checklist could account for a range of experiences.

Figure 1. Applications and devices used in the validation study. Top left to bottom right: Wayfair Spaces (Magic Leap 1) (A), Local Applications (Epson Moverio) (B), Google Maps (mobile) (C), ShapesXR (Meta Quest Pro) (D), Fan Blade Replacement Training (Magic Leap 2) (E).

Table 1. Descriptions of applications used in the Heuristic Evaluation and User Testing validation stages.

For each of the five applications, six human factors student researchers from Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University were chosen to conduct heuristic evaluations. These researchers were chosen based on their previous experience, as they were trained on the heuristic evaluation method. Each researcher was provided either the experimental or the control heuristics. Three evaluations were completed using the experimental heuristics, and three were completed using the control heuristics (de Paiva Guimarães and Martins, 2014). The results from these evaluations were compared to identify which heuristic checklist identified more usability/UX, domain-specific, and severe/critical issues across applications.

The experimental heuristics identified more usability/UX issues (M = 41, SD = 8.46), domain-specific issues (M = 17.2, SD = 4.97), and severe/critical issues M = 12.8, SD = 2.78) than the control checklist. Krippendorff’s Alpha analysis was completed to identify the inter-rater reliability of the heuristic evaluations for each of the five applications (Hayes and Krippendorff, 2007). Overall, the experimental heuristics were more reliable than the control heuristics across all five applications, Epson Moverio and variety of apps (α = 0.4457, α = 0.072), Magic Leap 1 and Wayfair Spaces (α = 0.4774, α = 0.1811), Magic Leap 2 and Fan Blade Replacement (α = 0.3975, α = 0.0999), Meta Quest Pro and ShapesXR (α = 0.1909, α = 0.1502), and Mobile Phone and Google Maps Live View (α = 0.2817, α = 0.1517), respectively. Evaluators who used the experimental heuristic checklist rated the applications more similarly to each other than those who used the control heuristic checklist. The alpha scores for both the experimental and control heuristic checklists, however, were low (<0.67). This is consistent with previous studies on heuristic evaluations, as different evaluators may find a wider breadth of usability issues (Smith, 2021; Leverenz, 2019; White et al., 2011), and when few evaluators provide feedback (e.g., 3 evaluators) (Moran and Gordon, 2023). Edits were made to the checklist based on the evaluator’s comments and suggestions, yielding 12 changes to the experimental checklist from this stage.

4.3.3 User testing

For the final validation test, the results from the heuristic evaluations were compared to user testing results with the same five applications and devices. This was done to compare the types of usability issues identified using both methods. A total of 41 participants were recruited from the local university and surrounding area for each of these user studies. They signed an informed consent form, completed a demographic questionnaire about their previous experience with XR products, and then were asked to complete tasks using their assigned application. Details on all of the tasks and accompanying measures can be found in Table 1 and Derby (2023).

Overall, both heuristic evaluations and user testing methods identified a variety of usability issues related to comfort, quality of the virtual objects, the user interface, consistency throughout the app, responsiveness, and feedback to users. If an application scored positively in the heuristic evaluations, it often also scored positively during the user tests. This similar pattern was also seen when applications scored poorly. However, some unique issues and recommendations were identified using each method. For example, during user testing, participants noted a “weird glitch” that occurred when picking up some objects, but not others. The heuristic evaluators identified this same issue as an inconsistency in how users could interact with 3D objects. Specifically, objects with holes, like virtual baskets, could only be picked up by grabbing the 3D frame, not through the small holes in the 3D object. In contrast, other objects allowed users to pick them up from any point, making this behavior feel inconsistent and unintuitive. A summary of all user testing and heuristic evaluation findings is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Comparison of findings from usability studies and heuristic evaluations. The middle area of the overlapping circles indicates findings in common from both methods.

User tests identified usability issues that involved user emotions, adaptivity, previous experiences that impacted their expectations, and social awkwardness, the user reported using the application in a public situation. For example, when a user indicated that the application was “cool”, “fun”, or “tedious” and “confusing”, they noted it in their experience. How users controlled a 3D object impacted this greatly. For example, ShapesXR’s feature that allows a user to throw an object across the room to delete it was interpreted to be humorous and brought enjoyment to the action, whereas controlling 3D objects with the user’s head in Epson Moverio applications brought a more negative experience, causing dizziness, eye strain, and discomfort. When users had an enjoyable time and found the controls easy to use, they often stated they wanted more options available to them to allow for different ways to have a fun experience. However, if an input method was difficult, users wished they had alternatives available that were easier to use. When in collaborative spaces, users reported having a more positive time when they knew that others around them were also involved in the experience. For example, when collaborating with a remote user in ShapesXR or when thinking about working with other students during the Fan Blade Replacement Training, users were excited about the possibilities that AR enabled. However, when using the Google Maps Live View in public, around bystanders who may have no knowledge of the app. Users felt closed off and embarrassed by the technology. Users reported that it felt like they were invading others’ privacy, because holding up the phone to look at the 3D content looked as if they were recording bystanders around them without consent.

Heuristic evaluations identified usability issues that involved long-term use, such as maintenance, how to recover from and report system errors when users encounter them, and the ease of completing real-world tasks. Evaluators identified how easy it was to clean and order replacement parts, and how customizable the hardware was for personal protective equipment (PPE), when necessary. Other context-dependent information was identified. For example, when evaluating Google Maps Live View, heuristics evaluators described how arm fatigue may occur after lengthy use and how it may be difficult to complete other phone tasks, such as taking a call or texting, while using the AR application. Additionally, heuristic evaluations identified specific improvements for instructional content and the importance of user content privacy. Evaluations included recommendations for additional instructional content, and information directing the user where to get help. Finally, heuristic evaluations also identified if a diverse set of users was represented. When creating avatars in ShapesXR, evaluators noted how a variety of options were available, enhancing the inclusive feelings toward the application.

Overall, results that indicated the applications’ usability strengths and weaknesses were found in both user tests and heuristic evaluations. Different specifics and issues were identified, however, which is consistent with findings in previous studies on heuristic evaluation validation (Smith, 2021; Leverenz, 2019). Both user testing and heuristic evaluation are complementary methods that are necessary when evaluating the overall usability of AR applications.

4.4 Step 8: refinement

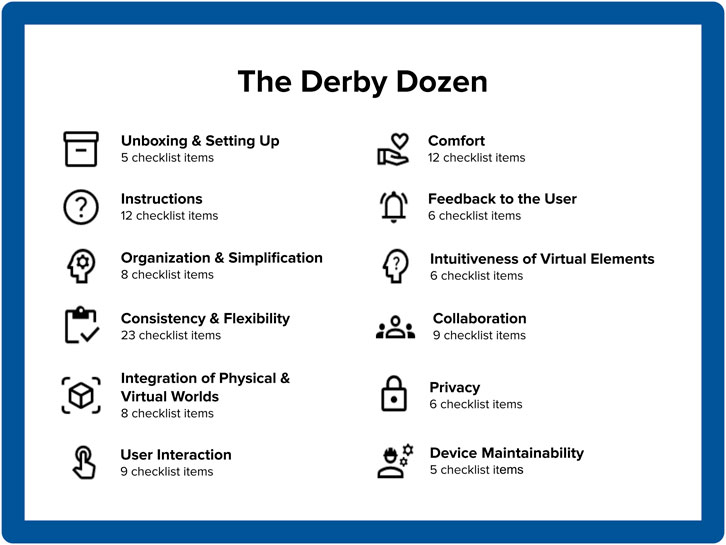

After incorporating the analysis from the expert review, heuristic evaluation, and user testing in validation step 7, a total of 38 changes were made to the experimental checklist since step 6, resulting in the Derby Dozen. Nineteen of these changes were a result of the expert evaluations and an additional 19 were from the heuristic evaluations and user testing. For example, in user testing, users identified that their feelings of privacy was a strong factor in their overall perceptions of the Google View application, so an additional heuristic was created to account for this. Compared to the original Derby and Chaparro heuristic checklist, 100 total changes were made (2022). These changes included 1 new heuristic, 19 new checklist items and 19 accompanying examples, 3 checklist items reworded, omission of 2 checklist items, 44 examples reworded, 12 other changes (checklist items moved to different heuristics, and toolkit quality-of-life changes such as auto-calculations and formatting changes). The Derby Dozen includes 12 heuristics (Figure 3) and 109 checklist items.

4.5 Practitioner toolkit

To facilitate easy analysis, the validated AR heuristic checklist was incorporated into an Excel toolkit that practitioners can use when evaluating their AR solutions. This toolkit includes the final 12 heuristics and 109 checklist items that had been validated in step 7 and refined in step 8, instructional material about how to complete a heuristic evaluation using these heuristics, and an automated calculation summary of the toolkit user’s evaluation results. Each heuristic is organized into a separate Excel tab, which includes details about each checklist item and space for the evaluator to rate each item and provide comments. These details are compiled immediately into the results tab for quick analysis. This toolkit has been validated and refined by comments from the expert evaluators and heuristic evaluators as previously described in step 7. This toolkit is provided in the Supplementary Material of this paper for download.

5 Discussion

The use of this toolkit has been reported in the literature to evaluate AR applications, including visual inspection in forestry (Fol et al., 2025), training for the military (Derby et al., 2024), reality-based learning for children (Baki et al., 2023), commercial product retail (Ford et al., 2022), and device comparison (Aros et al., 2025). As AR gains popularity within the training, educational, and consumer space, companies such as Apple and Meta have stated that this technology is the future of our work, communication, and entertainment (Apple Inc., 2020; Meta Reality Labs, 2020). There is much promise in how this emerging technology may impact our future lives. However, some examples of this technology have thrived while others have failed to gain traction. In order for it to succeed, researchers must consider the usability of this technology, as it plays a large role in its acceptance and users’ repeat use. Researchers can use methods such as heuristic evaluation to assess the usability of an application or device throughout the development process, well before it gets into potential users’ hands. This is a benefit, as it allows this method to seamlessly integrate within the iterative design process, so changes to enhance the usability can be discovered and fixed quickly and effectively.

5.1 Conclusion and future research

Through a rigorous development process described in this paper, the Derby Dozen AR heuristic toolkit demonstrated it can be used for successful assessment of usability issues in a variety of AR hardware types and use cases. This toolkit can be used to assess current hardware and software designs and make recommendations about how to improve the usability of the design in a way to make the experience more effective, efficient, and satisfying for users. Future research should continue to validate the toolkit under a variety of settings and applications and with the latest technology and devices (e.g., smart glasses), given the rapidly changing landscape of AR.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the approved IRB protocol states that information collected as part of this research will not be used or distributed for future research studies. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to amVzc3ljYWRlcmJ5QGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

JD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. MA: Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. BC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing, Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Augmented Reality Enterprise Alliance (AREA) for their support of this research. We also gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the students at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University who assisted with data collection and analysis.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frvir.2025.1700915/full#supplementary-material

References

Apple Inc (2020). Augmented reality in business. Available online at: https://www.apple.com/business/docs/resources/Augmented_Reality_in_Business_Overview_Guide.pdfApple.

Aros, M., Arnold, H., and Chaparro, B. (2025). “Exploring device usability: a heuristic evaluation of the apple vision Pro and Meta Quest 3,” in Communications in computer and information science, 3–12. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-94150-4_1

Baki, R., Mumu, A., Zannat, R., Rahman, M., Mahmud, H., and Islam, M. N. (2023). “Usability analysis of augmented reality-based learning applications for kids: insights from SUS and heuristic evaluation,” in International Conference on Design and Digital Communication, 122–135. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-47281-7_10

Caudell, T. P., and Mizell, D. W. (1992). “Augmented reality: an application of heads-up display technology to manual manufacturing processes,” in Proceedings of the Twenty-Fifth Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 659–669. doi:10.1109/HICSS.1992.183317

de Paiva Guimarães, M., and Martins, V. F. (2014). “A checklist to evaluate augmented reality applications,” in Proceedings of the 2014 XVI Symposium of Virtual and Augmented Reality, 45–52. doi:10.1109/SVR.2014.17

Derby, J. (2023). Designing tomorrow’s reality: the development and validation of an augmented and mixed reality heuristic checklist. Doctoral dissertation. Daytona Beach (FL). Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University. ERAU Scholarly Commons. Available online at: https://commons.erau.edu/edt/771.

Derby, J. L., and Chaparro, B. S. (2022). “The development and validation of an augmented and mixed reality usability heuristic checklist,” in Virtual, Augmented and Mixed Reality: Design and Development. HCII 2022. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Editors J. Y. C. Chen, and G. Fragomeni (Cham: Springer), 153–170. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-05939-1_11

Derby, J., Hughes, C., and Archer, J. (2024). “Utilizing extended reality usability heuristics to drive effective XR training applications,” in Proceedings of I/ITSEC 2024 Conference.

Endsley, T. C., Sprehn, K. A., Brill, R. M., Ryan, K. J., Vincent, E. C., and Martin, J. M. (2017). “Augmented reality design heuristics: designing for dynamic interactions,” in Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, 2100–2104. doi:10.1177/1541931213602007

Fol, C. R., Zhao, J., Späth, L., Murtiyoso, A., Remondino, F., and Griess, V. C. (2025). Advancing forest biodiversity visualisation through mixed reality. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 15908. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-00285-y

Ford, S., Miuccio, M., Shirley, L., Duruaku, F., and Wisniewski, P. (2022). “Mobile augmented reality design evaluation,” in Proceedings of the 2022 HFES 66th International Annual Meeting, 66 1 1275–1279. doi:10.1177/1071181322661382

Hayes, A. F., and Krippendorff, K. (2007). Answering the call for a standard reliability measure for coding data. Communication Methods and Measures 1 (1) 77–89. doi:10.1080/19312450709336664

Leverenz, T. (2019). The development and validation of a heuristic checklist for clinical decision support Mobile applications.

Lima, I. B., and Hwang, W. (2024). Effects of heuristic type, user interaction level, and evaluator’s characteristics on usability metrics of augmented reality (AR) user interfaces. Int. J. Human–Computer Interact. 40 (10), 2604–2621. doi:10.1080/10447318.2022.2163769

Meta Reality Labs (2020). The future of work and the next computing platform. Available online at: https://tech.facebook.com/reality-labs/2020/5/the-future-of-work-and-the-next-computing-platform/.

Milgram, P., and Kishino, F. (1994). A taxonomy of mixed reality visual displays. IEICE Trans. Inf. Syst. E77-D (12), 1321–1329. Available online at: https://globals.ieice.org/en_transactions/information/10.1587/e77-d_12_1321/_p (Accessed: 17 February 2025).

Mohammad, A., and Pedersen, L. (2022). Analyzing the use of Heuristics in a virtual reality learning context: a literature review. Informatics 9 (3), 51. doi:10.3390/informatics9030051

Moran, K., and Gordon, K. (2023). How to conduct a heuristic evaluation. Nielsen Norman Group. Available online at: https://www.nngroup.com/articles/how-to-conduct-a-heuristic-evaluation/ (Accessed February 17, 2025).

Nielsen, J. (1994). “Enhancing the explanatory power of usability heuristics,” in Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI '94), Boston, Massachusetts, USA, 24–28 April 1994 (New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery), 152–158. doi:10.1145/191666.191729

Nishchyk, A., Sanderson, N. C., and Chen, W. (2024). Elderly-centered usability heuristics for augmented reality design and development. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 24, 1–21. doi:10.1007/s10209-023-01084-w

Omar, K., Fakhouri, H., Zraqou, J., and Marx Gómez, J. (2024). Usability heuristics for metaverse. Computers 13 (9), 222. doi:10.3390/computers13090222

Othman, M. K., Mat, R., and Zulkiply, N. (2025). WVREA heuristics: a comprehensive framework for evaluating usability in wearable virtual reality educational applications (WVREA). Educ. Inf. Technol. 30, 13599–13662. doi:10.1007/s10639-024-13234-5

Quiñones, D., Rusu, C., and Rusu, V. (2018). A methodology to develop usability/user experience heuristics. Computer Standards & Interfaces 59, 109–129. doi:10.1016/j.csi.2018.03.002

Rauschnabel, P. A., Felix, R., Hinsch, C., Shahab, H., and Alt, F. (2022). What is XR? Towards a framework for augmented and virtual reality. Comput. Hum. Behav. 133, 107289. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2022.107289

Rusu, C., Muñoz, R., Roncagliolo, S., Rudloff, S., Rusu, V., and Figueroa, A. (2011). “Usability heuristics for virtual worlds,” in Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Advances in Future Internet, France, 21–27 August 2011, 16–19.

Smith, D. (2021). Flux VR: the development and validation of a heuristic checklist for virtual reality game design supporting immersion, presence, and flow. Doctoral dissertation. Wichita, KS: Wichita State University. Available online at: https://soar.wichita.edu/handle/10057/21577.

Sumithra, T. V., Ragha, L., Vaishya, A., and Desai, R. (2024). Evolving usability heuristics for visualising Augmented reality/Mixed Reality applications using cognitive model of information processing and fuzzy analytical hierarchy process. Cognitive Comput. Syst. 6 (1–3), 26–35. doi:10.1049/ccs2.12109

Sutcliffe, A., and Gault, B. (2004). Heuristic evaluation of virtual reality applications. Interact. Comput. 16 (4), 831–849. doi:10.1016/j.intcom.2004.05.001

Sutherland, I. E. (1968). “A head-mounted three-dimensional display,” in AFIPS Conference Proceedings, 33 Part I 757–764. doi:10.1145/1476589.1476686

Szentirmai, A. B., and Murano, P. (2023). “New universal design heuristics for mobile augmented reality applications,” in Lecture notes in computer science, 404–418. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-48041-6_27

Keywords: AR devices, augmented reality, heuristic evaluation, heuristics, mixed reality, usability

Citation: Derby JL, Aros M and Chaparro BS (2025) The validation of a heuristic toolkit for augmented reality: the derby dozen. Front. Virtual Real. 6:1700915. doi: 10.3389/frvir.2025.1700915

Received: 07 September 2025; Accepted: 28 November 2025;

Published: 18 December 2025.

Edited by:

Sazilah Salam, Technical University of Malaysia Malacca, MalaysiaReviewed by:

Sam Van Damme, Ghent University, BelgiumJoko Triloka, Informatics and Business Institute Darmajaya, Indonesia

Stefan Graser, Hochschule RheinMain, Germany

Copyright © 2025 Derby, Aros and Chaparro. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jessyca L. Derby, amVzc3ljYWRlcmJ5QGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Jessyca L. Derby

Jessyca L. Derby Michelle Aros

Michelle Aros Barbara S. Chaparro

Barbara S. Chaparro