- 1Leverhulme Research Centre for Forensic Science, University of Dundee, Dundee, United Kingdom

- 2London South Bank University, London, United Kingdom

- 3Goldsmiths, London, United Kingdom

- 4Fast Familiar, London, United Kingdom

In a courtroom, it is essential that the scientific evidence is both understandable and understood, so that the strengths and limitations of that evidence, within the context of a legal case, can inform decision making. The Evidence Chamber brings together entertainment, public engagement with science and research into a public performance activity that is centred around digital storytelling and science communication. This experience engages public audiences with science and allows a better understanding of how people interpret scientific evidence. In this paper, we discuss how we created this experience as an in-person and fully virtual performance through successful collaboration between forensic science research, public audiences, public engagement professionals, the legal profession, and digital performance artists.

Introduction

Devonshire and Hathway note, “the concept of public engagement (PE) in science has evolved steadily over the last 30 years. Early PE activities were often delivered didactically in a one-way flow of information … Over time, PE has become more interactive.” (Devonshire and Hathway, 2014). Alan Irwin describes the early concepts as the “deficit model” (Irwin, 1995), implying that if only the public had more knowledge, everything would be improved. This model was based on scientists transmitting to passive, silent publics. More recent work has focused much more on two-way interaction (Rowe and Frewer, 2005). Ahmedien, meanwhile, argues that new media arts are an ideal vehicle for this interaction, because the digital technology deployed allow scientists to “communicate to laypeople and, simultaneously, collect their responses” (Ahmedien, 2021), and that “new-media arts can ensure the maximum level of the engagement of the public towards research.”

Recent approaches have also emphasised the importance of what Ahmedien calls the “entertainment-based learning approach” that uses strategies such as gamification. Entertainment would seem to be a valuable strategy; Sarah Davies has argued for the important role of pleasure and a greater focus in general on the role of emotion and affect, which she has described as “a lacuna in studies of public engagement” (Davies, 2014). She goes on to write: “we should as practitioners, actively seek to design participatory processes which enable the expression of knowledges and perspectives in modes which go beyond the discursive”, instead creating space for and welcoming “passion and outrage.”

The notion of making high stakes decisions based on scientific evidence is not a new concept within the context of legal proceedings. Within a court of law, scientific evidence is communicated by expert witnesses in response to questioning from defence and prosecution legal representatives. Recently, there has been increasing commentary that forensic science is at a “critical juncture” where the robustness of methods and the effective communication and understanding of increasingly complex information are being questioned (O’Brien et al., 2015; Science and Technology Committee 2019). It is critical that evidence presented in legal cases is understood by all parties in the courtroom to avoid miscarriages of justice, however this may not occur in reality. Research has begun to start understanding the challenges and potential approaches but it is still at an early stage (Black and Nic Daeid 2015; McCarthy Wilcox and NicDaeid, 2018; Hackman 2020; Hoffman et al., 2021).

The Evidence Chamber was initiated as a collaboration between forensic science researchers at the Leverhulme Research Centre for Forensic Science (LRCFS) and interactive digital performance artists at Fast Familiar in 2019. Members of the public became participants in an interactive digital performance by taking on the role of jury members in a fictional murder case. In The Evidence Chamber the audience is presented with two different types of scientific evidence, Gait and DNA through the medium of expert witness testimonies, they are also given informative scientific comics based on written primers that were produced for the judiciary. Following this evidence gathering and jury deliberation process they meet with a forensic expert and ask open questions in a debrief.

The aim was to create a new engagement experience that would immerse players within the setting of the court, where, within the theatre provided by the jury deliberation room, they are required to make life-changing decisions about the fate of another based on scientific evidence presented to them. The reaction of the “jury” to expert scientific evidence gives us a better understanding of how the communication of that information by experts is understood by lay audiences and whether aids, such as understandable science comics, could support that process.

There have previously been theatrical experiences and academic studies based on fictional jury trials (Barnard and De Meyer, 2020a). There have also been interactive digital experiences where participants take on the role of jurors (Barnard and De Meyer, 2020b). However, this format has not, as far as the authors are aware, previously been used as a public engagement with science activity. In addition, while in-person theatre for science public engagement is fairly well established (Shepherd-Barr, 2020), interactive digital performance is a new medium for engaging the public with science.

A distinctive feature of The Evidence Chamber is that it functions simultaneously as both a public engagement and a research tool, informing and provoking discussion about forensic science and its use to enable high stakes decision making. The inputs by the participants (conversations, questions and verdicts) to the experience were used to assess the ability of a jury to comprehend the scientific evidence presented in a video format. Secondly, the impact of scientific comics specific to the evidence types being presented and whether these aided comprehensions were explored. Within the event, the players receive information about the evidence presented to them in digital form. They need to be informed enough by this to engage in quality conversation to enable a guilty or not guilty decision to be formed with the understanding that there was no “correct” verdict.

Expert evidence is defined as being “admissible (in order) to furnish the court with information which is likely to be outside the experience and the knowledge of a judge or jury” (Crown Prosecution Service Criminal Practice Direction V Evidence 19A Expert Evidence, 2015). Forensic science experts in England and Wales must comply with the Core Foundation Principles and the Forensic Science Regulator’s Code of Conduct (Crown Prosecution Service, 2019) and with the Criminal procedure rules and practice directions 2020—rule 19 (Criminal Procedure Rules and practice Directions, 2020). In Scotland, expert witnesses must comply with the Expert Witness Code of Conduct (Law Society of Scotland, Expert witness code of practice). Forensic science experts initially provide written reports of evidence but they may be required to present oral evidence in court. It is their role to give their expert opinion based on their analysis of the available evidence.

In the UK, anyone between the ages of 18 and 70 years old; registered to vote in parliamentary or local government elections; a registered citizen in the UK, the Channel Islands or the Isle of Man for at least 5 years can be called for jury service. Part of this role may be to listen to scientific evidence presented in trial and in order to evaluate the weight of the evidence placed before them and make decisions, the jury must understand the scientific evidence presented to them.

To assist the judiciary when scientific evidence is to be put to the jury within a legal case, a series of judicial primers are being produced by scientists, the judiciary, the Royal Society and the Royal Society of Edinburgh in a unique partnership and ambitious public engagement activity. Each primer presents a clear and accurate position of the science which underpins a particular type of forensic scientific evidence including its limitations (Royal Society, 2017; Black and NicDaeid 2018). The LRCFS have used the judicial primers as the basis for science comics. The first two comics “Understanding Forensic Gait Evidence” which is an evaluation of how people walk (Murray et al., 2020a) and “Understanding Forensic DNA Evidence” (Murray et al., 2020b) were used in The Evidence Chamber.

Forensic gait analysis represents an example of a subjective comparison of features with little underpinning frequency data or standardised methodologies and has been heavily criticised for the absence of an objective or robust scientific methodology (Metropolitan Police). The analysis of DNA by forensic scientists in contrast, could be considered to be more objective in terms of the measurements which are robustly scientifically underpinned and validated with large data sets providing frequency data and an accepted standardised methodology. The explanation of both evidence types in court can be difficult to understand as it often contains a significant amount of specialist terminology, statistics and probabilistic reasoning.

Methodology—Creating The Evidence Chamber

The initial planning meeting for The Evidence Chamber brought together scientists, the Public Engagement Manager from LRCFS and artists from Fast Familiar. Fast Familiar had already created a jury based interactive digital experience based around the use of tablet devices where information is presented to individual participants allowing them to vote and add comments in response to prompts.

A scenario was created based on the two evidence types featured in the judicial primers and comics and Fast Familiar built a narrative around this including additional evidence presented by lay (non-scientific) witness as well as defence, and prosecution summations of the case. We prioritised presenting the scientific evidence in a way that reflected how expert evidence would be directed to a jury within a courtroom (verbally—in response to questioning by legal representatives). Within the context of the experience this presented several challenges;

i) the running length of the performance, a case presented in a court of law can take several days or weeks depending on the complexity of the evidence

ii) in a courtroom, expert witnesses respond to questions posed by the legal participants. For this performance format using ipad software it was not practical for the expert witnesses to have extensive questioning from defence and prosecution as it would take too long and only evidence in chief without cross examination) was presented.

iii) recreating the courtroom location within a simulation.

We addressed these challenges in the performance by limiting the total length for the experience of 90 min (which is a similar length of time to many other leisure activities) and restricted the expert witness videos to 5 min. For the expert witness videos we created presentations that were based on the responses to questions that could have been asked in a court in consultation with forensic science and legal experts. The in-person performance took place within a courtroom with the “jury” sitting in the witness deliberation room. In the virtual performance this feeling of “place” was carefully considered and this is discussed in further detail in Moving From In-Person to Virtual.

In addition to the oral evidence of the expert witnesses, the participants were also provided with factual evidence including bus route information, phone records and character references for the accused which were used to provide context to the case. Some artistic licence was used to ensure participants engaged with the story and players took on an active role in the experience they were asked to read some of the evidence and statements out loud.

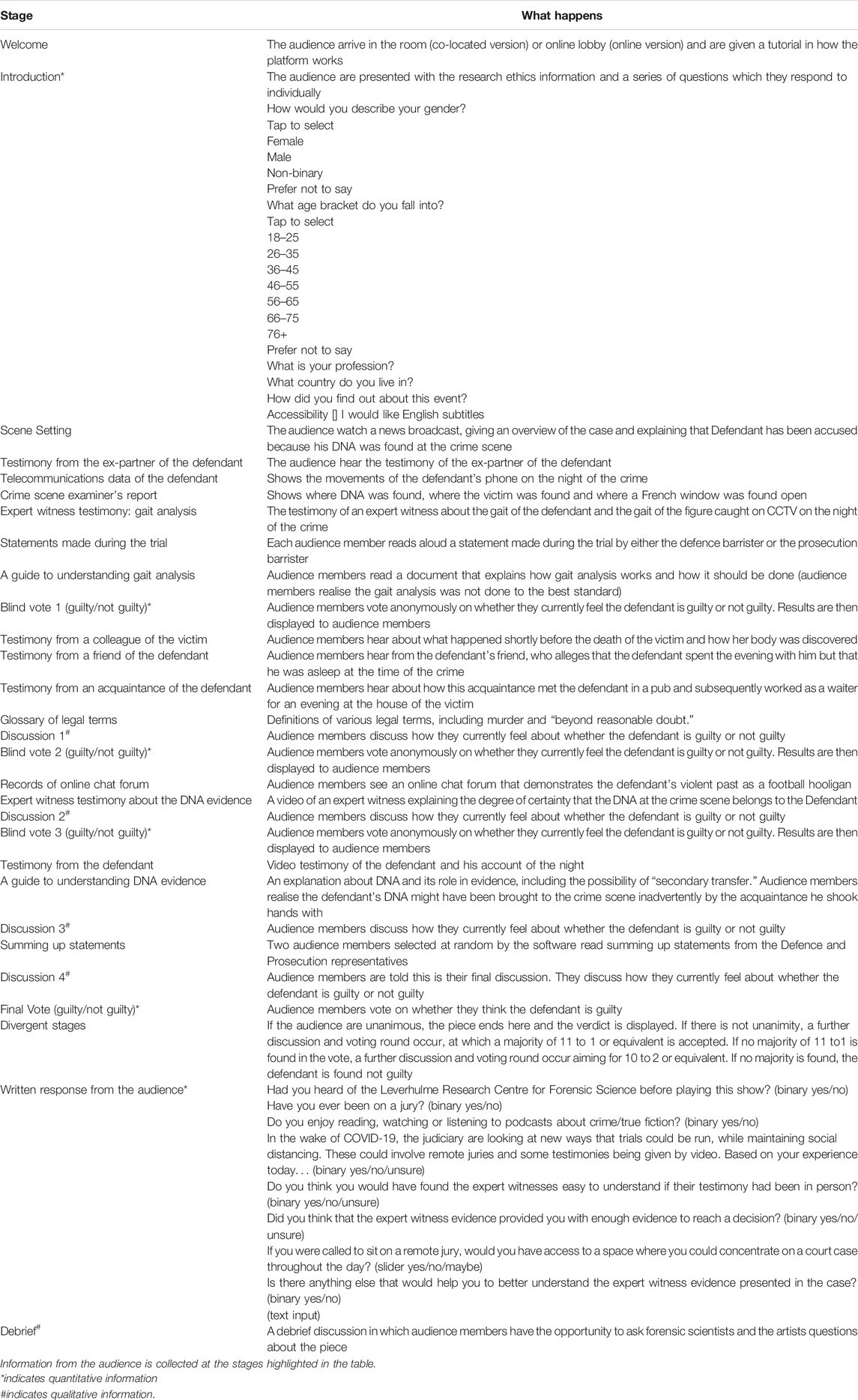

During The Evidence Chamber, the “jury” was given time to discuss the evidence at directed moments and for specified lengths of time. At various stages, the participants were also asked to vote on whether they thought the accused was guilty or not guilty culminating in a final decision of the group. The structure of the voting (after and before the comics/witness statements) allowed the gathering of data to explore how the evidence, comics and discussion affected their views. The full structure of the performance and information gathered from the audience is described in Table 1.

Testing and Refining

Once the story and evidence were created, paper versions of the video scripts were tested with scientists, forensic scientists and members of the public. These sessions provided feedback on the order in which evidence appeared. This order was carefully considered since it allowed the creation of a narrative which in turn, led participants into discussions at key points. It also ensured that there was enough uncertainty within the evidence presented, to provide opportunities for meaningful discussion. For example, the testimony of the defendant was moved from an earlier position to become the final testimony as it created more of a “climax” to finally meet the person about which the audience have heard so much. The DNA evidence was also moved later in the piece to improve the structure of alternating evidence pointing towards guilty and towards not guilty. The original order in which evidence was presented was revised as it showed a “reveal” happened too early in the process, stifling discussion.

Ethical permission was obtained from the University of Dundee ethics committee and all participants signed consent forms prior to taking part. During the experience, all participants remained anonymous and were referred to only by a juror number. Discussions of the “jury” were recorded along with the verdicts and responses to questions on the tablet devices.

The Performance

The first public performance took place in the jury deliberation room at Dundee Sheriff Court in October 2019. The public performance involved 15 jury members (based on the Scottish legal system). The setting gave a sense of theatre and “real life” to the experience while also offering the participants the opportunity to experience the layout and structure of a court. No introductions were given before the event and no prompts were given to allow introductions of the participants, much like in a real jury setting. This structure, the nature of their participation and the venue set a serious tone for the performance. The players took their roles seriously and engaged in meaningful discussions which frequently became detailed and sometimes passionate.

After a verdict was reached, participants were taken into the main courtroom where they had the opportunity to question representatives from LRCFS and Fast Familiar. This conversation was more informal and less structured offering the participants the opportunity to focus on any element they wished to. A full overview of the game experience and data collected is included in Table 1.

Moving From In-Person to Virtual

In 2020, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the face-to-face experience was converted to a virtual setting. The conversion used the same platform as the original piece but there were four key challenges:

I. Enabling Discussion in a virtual setting. This involved embedding a video calling Application Programming Interface into the software, so that participants could see and hear each other during the discussion phases, but which turned off when they were watching videos or reading documents.

II. Adapting to different browsers and devices. This involved adapting the video syncing software which plays the videos of the witnesses that participants watch, to allow it to use less processing power. The process also necessitated limiting the experience to two browsers: Chrome and Firefox.

III. Adapting to different broadband strengths and speeds. This involved using adaptive bitrate streaming, similar to Youtube; so that the definition of video streamed would increase or decrease based on the internet speed of the participant.

IV. Creating a smooth human-computer interaction. This involved designing the video call section to be in a grid that followed juror numbers and in which people remained in the same “place” on-screen and using iconography that felt familiar, such as similar hand raise and mute buttons to those used by popular video conferencing platforms such as Zoom and Microsoft Teams.

The story and the recorded/presented elements did not change in the virtual setting but we anticipated that the virtual experience would differ. It is more difficult to read more subtle body language and signals in a virtual situation as well as potentially more difficult for people to indicate they wish to speak. There were also potential issues with connectivity and reduced opportunities for the Fast Familiar team to assist if help is required.

The online version of the experience was tested with members of the public through the LRCFS “Citizens” “Jury”, a group of lay members who contribute to the work of the research centre. In this test the software was assessed along with the flow of discussion and ability of the jury members to interact with each other in this virtual setting. It became clear that a “Court Clerk” was needed to provide initial information, play a role in bringing the jury together, handle technical queries and manage the piece. One of the participants was assigned as a Foreman who could lead the discussions across the jury members at the appropriate times during the piece.

When participants booked the experience they were sent a copy of an accountability document, outlining the behaviour that would create a safe space for participants. One of the roles defined for the “Court Clerk” was to ensure adherence to this code.

The decision was also made to use a juror number rather than a name for participants. This had the benefit of ensuring that all jurors could be called on equally to speak, rather than people avoiding calling upon those with names they find harder to pronounce, which can further exacerbate societal inequalities. Being always referred to as a juror also reminded participants of their role as jurors and helped to focus them on the gravity of the (fictional) situation and the importance of their task. In addition to their juror number, their pronouns (which they had inputted at the beginning) would also appear at the bottom of their webcam within the video call. This avoided any accidental misgendering that might have occurred. All videos were captioned. The debrief was also maintained.

Discussion

The virtual experience launched in July 2020 to a public audience and was advertised via the University of Dundee, LRCFS and Fast Familiar through press releases, mailing lists, websites and social media. Each performance kept the attention of the audience for over 90 min with many participants indicating that they would like the performance to last longer.

Between July 2020 and the end of August 2020 the play was performed 23 times involving 253 participants (all shows sold out). 69% of players identified themselves as female, 27% as male, 3% non-binary and 1% not disclosed. 59% of players were aged between 26 and 45. Most participants were based in the UK but the virtual show also allowed players from around the world to join - an advantage over an in-person performance.

47% of participants were from an art, design, entertainment, sports and media background. This is perhaps a different audience than would be expected for a science communication activity but similar to what might be expected to attend a contemporary theatre production. Participation in the virtual experience has also been limited to those who have access to fast broadband connections and desktop/laptop computers and plan to run the performance face-to-face with groups when we are able to. A complete analysis of the verbal discussions is planned and will address the core areas which The Evidence Chamber was designed to explore. Preliminary observations suggest that the discussions within the performance and the debrief were detailed and sophisticated, which indicated that participants were engaged with the experience and all actively participated in sharing and receiving information. The Jury foreman made sure that all participants were given time to put forward their views in each case.

It has been observed that even on social media sites such as Twitter (which offer two-way interactions) it can be difficult to generate conversation between scientists and public audiences (Jahng and Lee, 2018). We believe The Evidence Chamber’s model of science engagement where peers interact with each other in addition to interacting with the science and experts has overcome some of these challenges in generating conversation.

Our hypothesis is that the discussions with the forensic expert would not be so specific and well informed were it not for the information shared through the comics and the self-directed discussions about the evidence that took place within the jury deliberation part of the performance. These questions were all led by the public audience rather than being directed by the expert. However, to fully test this hypothesis further research is needed—which would include collecting more knowledge on participants levels of understanding of scientific evidence types.

There is no single method of measuring engagement and very few use both qualitative and quantitative perspectives. This in turn means that demonstrating how engaged an audience is in an activity can be difficult (Trunfio and Rossi, 2021). In The Evidence Chamber the format allows members of the public to engage deeply and actively with scientific ideas, deploying them in their discussions and applying that knowledge to decision making. A benefit of using digital modes of delivery is that it becomes possible to gather much more detailed and granular data about how audience members are engaging with different pieces of information (how long they spend looking at different documents, for example). In addition, we gain insight into their deliberative process (as it is possible to measure how long it takes for participants to vote for example) along with qualitative data in the form of discussion recordings.

This model of engagement may be a useful method for others who wish to combine entertainment and education in science and health while also providing useful data from the experience to inform future communication practices. All sessions of The Evidence Chamber sold out, showing there was a public interest in an activity such as this. In addition, the piece has also been modified and used to structure professional training for legal practitioners, forensic psychologists and other students.

The key to the dual nature of the project is that The Evidence Chamber links engagement with science and research through an interactive narrative. Here we describe how and why it was created and the outcomes and learning so far. The Evidence Chamber was created by forensic scientists, science public engagement professionals and new media artists as an attempt to create a highly interactive science public engagement experience that engages public audiences emotionally through the design of an immersive scenario (a jury trial of a fictional case that rests on forensic evidence) that prompts passionate discussion about the science in the case and leads to a detailed live interaction between forensic scientists and members of the public at the end of the fictional scenario.

We believe this project demonstrates the potential for new media arts projects as a vehicle for meaningful, interactive public engagement with science and believe there is a need for further exploration of different new media arts tools and formats for this purpose. New media arts are already established as a field of public engagement with biomedical sciences (Ahmedien, 2021) but there is a need for further practice, research and evaluation in other scientific fields.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the University of Dundee, Centre for Anatomy and Human Identification Ethics Committee. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the creation of The Evidence Chamber experience. RB was the writer, DB the Director, JM the Computational Artist. HD, ND, and LH provided content, reviewed content and organised the public to play the game. HD played the role of an Expert Witness. HD and DB wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the manuscript, read and approved the submitted version.

Funding

Leverhume Trust RC-2015-011 Arts Council England ORGR-00232246.

Conflict of Interest

Author RB was employed by the company Fast Familiar.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The LRCFS Citizens’ Jury, Lesley Whitefield, Margaret Sherriff, Marion Todd, Samantha Henderson, Megan Young, Lindsey Eppy, Elizabeth Turner, Catherine Wooldridge, Gillian Stewart, David Evans, Anna Day. Kadja Manninen, University of Nottingham. Contributors to The Evidence Chamber; cast Sabrina Carter, Gillian Lees, Gary Mackay, John Milroy, Graeme Rooney, Paul McFadyen, Chris Hall. Thanks to Kris De Meyer, William Galinsky and Marianne Maxwell.

References

Ahmedien, D. A. M. (2021). New-media Arts-Based Public Engagement Projects Could Reshape the Future of the Generative Biology. Med. Humanities 47, 283–291. doi:10.1136/medhum-2020-011862

Barnard, D., and De Meyer, K. (2020b). The Justice Syndicate: Using iPads to Increase the Intensity of Participation, Conduct agency and Encourage Flow in Live Interactive Performance. Int. J. Perform. Arts Digital Media 16 (1), 68–87. doi:10.1080/14794713.2020.1722916

Barnard, D., and Meyer, K. D. (2020a). The Justice Syndicate: How Interactive Theatre Provides a Window into Jury Decision Making and the Public Understanding of Law. L. Humanities 14 (2), 212–243. doi:10.1080/17521483.2020.1801137

Black, S., and Nic Daeid, N. (2015). Time to Think Differently: Catalysing a Paradigm Shift in Forensic Science. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 370, 20140251. doi:10.1098/rstb.2014.0251

Black, S., and NicDaeid, N. (2018). Judicial Primers-A Unique Collaboration between Science and Law. Forensic Sci. Int. 289, 287–288. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2018.05.050

Criminal Procedure Rules and Practice Directions (2020). Criminal Procedure Rules and Practice Directions. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/rules-and-practice-directions-2020 (Accessed September 21, 2021).

Crown Prosecution Service (2019). Expert Evidence. Available at: https://www.cps.gov.uk/legal-guidance/expert-evidence (Accessed September 21, 2021).

Crown Prosecution Service Criminal Practice Directions 2015 Division V Evidence (2015). Expert Evidence. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/rules-and-practice-directions-2020 (Accessed September 21, 2021).

Davies, S. R. (2014). Knowing and Loving: Public Engagement beyond Discourse. S&TS 27 (3), 90–110. doi:10.23987/sts.55316

Devonshire, I. M., and Hathway, G. J. (2014). Overcoming the Barriers to Greater Public Engagement. Plos Biol. 12, e1001761. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001761

Hackman, L. (2020). Communication, Forensic Science, and the Law. Wires Forensic Sci. 3, e1396. doi:10.1002/wfs2.1396

Hoffman, B. L., Hackman, L., and Lindenfeld, L. A. (2021). Training for Communication in Forensic Science. Emerg. Top. Life Sci. 5 (3), 359–365. doi:10.1042/ETLS20200296

Irwin, A. (1995). Citizen Science: A Study of People, Expertise and Sustainable Development. London: Routledge.

Jahng, M. R., and Lee, N. (2018). When Scientists Tweet for Social Changes: Dialogic Communication and Collective Mobilization Strategies by Flint Water Study Scientists on Twitter. Sci. Commun. 40 (1), 89–108. doi:10.1177/1075547017751948

Law Society of Scotland Expert Witness Code of Practice. Available at: https://www.lawscot.org.uk/members/business-support/expert-witness/expert-witness-code-of-practice/(Accessed September 21, 2021).

McCarthy Wilcox, A., and NicDaeid, N. (2018). Jurors' Perceptions of Forensic Science Expert Witnesses: Experience, Qualifications, Testimony Style and Credibility. Forensic Sci. Int. 291, 100–108. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2018.07.030

Metropolitan Police Forensic Gait Analysis in the Investigation of Crimes. Available at: https://www.met.police.uk/foi-ai/metropolitan-police/disclosure-2020/october/forensic-gait-analysis-investigation-crimes/(Accessed September, 2021).

Murray, C., Vaughan, P., Nabizadeh, G., Findlay, L., Doran, H., Nic Daeid, N., et al. (2020a). Understanding Forensic Gait Analysis #1. (Understanding Forensic Gait Analysis) (Dundee: University of Dundee). doi:10.20933/100001152

Murray, C., Vaughan, P., Nabizadeh, G., Findlay, L., Nic Daeid, N., Doran, H., et al. (2020b). Understanding Forensic DNA Analysis (Dundee: UniVerse). doi:10.20933/100001175

O'Brien, É., Nic Daeid, N., and Black, S. (2015). Science in the Court: Pitfalls, Challenges and Solutions. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 370, 20150062. doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0062

Rowe, G., and Frewer, L. J. (2005). A Typology of Public Engagement Mechanisms. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 30 (2), 251–290. doi:10.1177/0162243904271724

Royal Society (2017). Science and the Law. Available at: https://royalsociety.org/about-us/programmes/science-and-law/#:∼:text=Primers%20for%20courts&text=Designed%20to%20assist%20the%20judiciary,the%20Royal%20Society%20of%20Edinburgh (Accessed September 21, 2021).

Science Technology Committee (2019). Forensic Science and the Criminal justice System: A Blueprint for Change. London: House of Lords. Available at: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld201719/ldselect/ldsctech/333/333.pdf (Accessed November 11, 2021).

Shepherd-Barr, K. (2020). The Cambridge Companion to Theatre and Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Keywords: science communication, forensic science, digital theatre, public engagement, law

Citation: Doran H, Barnard D, McAlister J, Briscoe R, Hackman L and Nic Daeid N (2021) The Evidence Chamber: Playful Science Communication and Research Through Digital Storytelling. Front. Commun. 6:786891. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2021.786891

Received: 30 September 2021; Accepted: 16 November 2021;

Published: 08 December 2021.

Edited by:

R. Lyle Skains, Bournemouth University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Will Grant, Australian National University, AustraliaMarina Joubert, Stellenbosch University, South Africa

Copyright © 2021 Doran, Barnard, McAlister, Briscoe, Hackman and Nic Daeid. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Heather Doran, aC5kb3JhbkBkdW5kZWUuYWMudWs=

Heather Doran

Heather Doran Dan Barnard

Dan Barnard Joe McAlister3

Joe McAlister3