- 1Department of Cardiology, The First Hospital of Jilin University, Changchun, Jilin, China

- 2School of Clinical Medicine, Jilin Medical University, Jilin City, Jilin, China

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common type of arrhythmia encountered in the clinical setting, and its occurrence is influenced by various factors, particularly aging. Senescence of atrial myocytes plays an important role in the development of AF, although the precise mechanisms underlying this association remain unclear. This review explores the pivotal role of atrial myocyte senescence in AF pathogenesis, moving beyond chronological age. It provides evidence that aging creates a pro-arrhythmic substrate via three interconnected mechanisms: 1) inflammatory activation (mitochondrial ROS, NLRP3, and SASP), 2) dysregulated calcium handling (RyR2 and SERCA2), and 3) cell cycle disruption (p16, p21, and p53). These pathways, compounded by epigenetic changes and SIRT1/mTOR signaling dysregulation, drive the electrical and structural remodeling that triggers and sustains AF. The review highlights promising therapeutic targets such as SIRT1 activators and NLRP3 inhibitors, proposing an integrated “senescence–AF axis” model, while identifying key research gaps in cell-type specificity and clinical translation. This comprehensive review outlines current progress in research in this area and future research directions and provides valuable references for forthcoming studies.

1 Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a type of cardiac arrhythmia that is commonly observed in clinical practice. It is characterized by rapid ectopic atrial impulses that replace sinus node’s control over atrial activity, leading to rapid and irregular atrial contractions. Consequently, impaired atrial contractile function manifests as palpitations, chest discomfort, and other clinical symptoms. Various factors contribute to the development of AF, including age, sex, smoking, and underlying comorbidities, with age being a particularly significant risk factor (Andrade et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2021). It is primarily associated with cellular senescence, whereby aging cells progressively lose their regenerative capacity and accumulate cellular damage, ultimately leading to senescence of organs (van Deursen, 2014; He and Sharpless, 2017). This phenomenon also affects the heart (Shimizu and Minamino, 2019). Cardiac aging is closely linked to the aging of myocardial cells, which is defined by the irreversible loss of cellular proliferative capacity accompanied by a gradual decline in physiological function (Mao et al., 2012). Notably, most cardiomyocytes stop dividing early in life (<1% retain proliferative capacity). This suggests that cardiomyocytes may begin accumulating age-related changes from a young age. While the frailty index provides a functional measure of aging, epigenetic aging—quantified via DNA methylation—offers a molecular perspective on cellular senescence. A study utilized the frailty index, rather than chronological age, to assess cellular aging in mice. The results demonstrated positive correlations between the frailty index scores and both AF susceptibility and duration. This provides evidence that biological aging status, not just chronological age, drives AF development (Jansen et al., 2025). Thus, epigenetic age estimates cellular aging more accurately than chronological age. Unlike chronological age, which is calculated based on time, epigenetic age is determined by measuring DNA methylation levels. This provides a better representation of a cell’s biological stage. Aging of myocardial cells is influenced by various factors, including oxidative stress and the activation of intracellular inflammatory pathways (Picca et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2022), changes in DNA methylation and cellular ion channels (Nattel et al., 2020; Kao et al., 2010), and changes in the expression levels of cell-cycle-related genes, such as p16, p53, and p21 (Kumari and Jat, 2021; Ou and Schumacher, 2018). Although these processes contribute to cardiomyocyte aging, their mechanistic links to AF initiation and progression remain poorly understood. This review proposes and elaborates on a unified conceptual framework—the senescence–AF axis—to synthesize the complex interplay between key aging mechanisms in atrial myocytes and AF pathogenesis. We posit that this axis is principally constituted by three cores, which are mutually reinforcing pathways: 1) chronic intracellular inflammatory activation (e.g., via mitochondrial ROS, NLRP3 inflammasome, and SASP), 2) dysregulation of calcium handling and ion homeostasis, and 3) disruption of cell cycle control and associated signaling (e.g., p16/p21/p53 and SIRT1/mTOR). These pathways collectively foster a pro-arrhythmic substrate characterized by electrical remodeling, structural fibrosis, and impaired cellular repair, thereby driving both the initiation and perpetuation of AF. This integrative model provides a scaffold for understanding how diverse age-related changes coalesce to promote AF and for identifying novel therapeutic targets aimed at modulating the senescence process itself, thereby offering a new perspective for geriatric cardiology and paving the way for personalized interventions targeting the biological basis of AF.

2 Mechanisms of initiation and maintenance of AF

AF is widely viewed to arise from ectopic depolarizations, primarily originating from the pulmonary veins but also from the vena cava and atria themselves, which override the sinoatrial node control (Brundel et al., 2022; Haissaguerre et al., 1998; Chen et al., 1999; Tsai et al., 2000). These depolarizations, which enhance local excitation of the myocardial tissue, stem from changes in the local myocardial cells exhibiting increased automaticity (Brundel et al., 2022; Ward-Caviness, 2021). While AF has traditionally been attributed to electrical remodeling, emerging evidence highlights cellular senescence as a key driver of atrial structural and functional deterioration (Chen et al., 2021b). The mechanisms of AF can be categorized as triggering or maintenance. Early and delayed after-depolarizations in the pulmonary veins may serve as the basis for this ectopic activity (Nattel et al., 2020). The precise formation of these impulses involves changes in the ion channels of atrial myocytes and the autonomic nervous system. Eliminating the excitatory connection between these vessels and the atria by ablation can effectively eliminate AF (Willems et al., 2006; Katritsis et al., 2010). While ectopic triggers initiate AF, structural remodeling and electrophysiological changes sustain it. In terms of maintenance mechanisms, some patients may not revert to sinus rhythm immediately after ablation and require electrical cardioversion, indicating the existence of mechanisms that are independent of the original ectopic impulses (Katritsis et al., 2010). Recognized maintenance mechanisms for AF include the multiple wavelet theory, reentry, and focal activity (Nattel et al., 2017).

Pathological changes, such as atrial fibrosis, impair the atrial muscle, leading to local conduction blockages. The incidence of these blockages is higher in patients with long-standing persistent AF than in those with acute AF (Allessie et al., 2010). These conduction impairments create conditions for atrial reentry, where anatomical and functional abnormalities can result in the formation of spiral waves that sustain AF (Quintanilla et al., 2021). Both the triggering and maintenance of AF involve common pathological and physiological changes, including alterations in myocardial cells, the myocardial interstitium, and the autonomic nervous system. During atrial myocyte aging, key changes such as mitochondrial dysfunction, increased reactive oxygen species (ROS), abnormal calcium channel activity, and expression of senescence-associated genes occur. These alterations closely resemble the pathological features observed in AF, suggesting a potential link between atrial myocyte aging and AF development (Chen et al., 2024; Ma et al., 2021). Together, these findings indicate that atrial myocyte senescence promotes both AF triggers (via ectopic activity) and maintenance (via structural/electrical remodeling), highlighting aging as a therapeutic target.

3 Senescence of atrial myocytes and its relationship with AF

While the precise triggers of cardiomyocyte senescence remain unclear, three key mechanisms have been implicated. The first involves the activation of intracellular inflammatory signaling pathways, leading to cell damage and reduced cellular protection. This includes the generation of ROS from mitochondrial dysfunction, activation of NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasomes and the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling, and decreased sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) activity. The second mechanism involves changes in DNA methylation and cellular dysfunction resulting from cytoskeletal disintegration, primarily affecting ion channels and intracellular calcium balance. The third entails inhibition of cell proliferation-related genes, such as p53, p21, and p16. Together, these senescence mechanisms create a pro-arrhythmic substrate via structural remodeling (fibrosis), electrical dysfunction (ion channels), and impaired repair (cell cycle arrest), thus collectively promoting AF initiation and persistence. Supplementary Table S1 summarizes current research on the relationship between AF and the aging of atrial cardiomyocytes. The subsequent sections of this article integrate these findings to elucidate how the aging process influences the pathogenesis of AF.

3.1 Mitochondrial dysfunction and activation of intracellular inflammatory signaling

3.1.1 Mitochondrial dysfunction and ROS-induced damage to atrial cells

Mitochondria, the primary energy source in cardiomyocytes, also generate ROS as byproducts (Kim et al., 2005). Their continuous replication throughout the cell’s lifespan can lead to mitochondrial DNA damage and mutations (Picca et al., 2018). To counteract this damage, cells activate the DNA repair enzyme poly ADP-ribose polymerase-1 (PARP-1) (Zhang et al., 2019). However, this energy-consuming repair process depletes nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+), thereby reducing mitochondrial energy production (Zhang et al., 2019). The resulting depletion of NAD+/NADH levels impairs the electron transport chain, which increases ROS production, promotes mitochondrial DNA mutations (Picca et al., 2018; Ramos-Mondragón et al., 2023), and induces protein oxidation (Kauppila et al., 2017; van Deursen, 2014), thereby further exacerbating mitochondrial DNA damage (Zhang et al., 2019; Yu et al., 2013). These mutations, in turn, lead to increased ROS generation (Hahn and Zuryn, 2019). Furthermore, during cellular senescence, declining autophagic clearance of damaged mitochondria causes impaired energy production and excessive ROS (Chapman et al., 2019). This vicious cycle of mitochondrial dysfunction, coupled with alterations in ion channels, contributes to AF development (Zhang et al., 2019; Wiersma et al., 2019). Supporting this mechanism, studies have shown that pharmacological supplementation of NAD + or inhibition of PARP-1 can prevent impairment of atrial contractility (Ramos and Brundel, 2020). Thus, mitochondrial ROS generation creates a pro-arrhythmic environment via DNA damage, energy depletion, and ion channel dysfunction, making it a potential therapeutic target in AF (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Mitochondrial dysfunction and activation of intracellular inflammatory signaling. The presence of ROS generated due to impaired mitochondrial function induces the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome within myocardial cells. Moreover, the influence of LPS produced by the gut microbiota results in the generation of pro-IL-18 and pro-IL-1β within myocardial cells. This process ultimately culminates in cellular aging and the activation of fibroblasts. Abbreviations: CD14, cluster of differentiation 14; FOXOs, fork head box O transcription factors; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; IL-18, interleukin-18; LBP, LPS binding protein; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; NF-κB, nuclear factor-kappa B; NLRP3, NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SASP, senescence-associated secretory phenotype; SIRT1, sirtuin 1; SMAD, small mothers against decapentaplegic; TLR4-MD2, toll-like receptor 4 co-receptor myeloid differentiation protein 2. Created with BioRender.com.

3.1.2 Activation of NLRP3 and AF

Building on mitochondrial ROS overproduction, aging also triggers NLRP3 inflammasome activation—a key inflammatory pathway in AF pathogenesis. Age-related gut microbiota dysbiosis increases intestinal barrier permeability (Thevaranjan et al., 2017), allowing lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from gut bacteria to enter the bloodstream and reach atrial tissue. LPS subsequently activates atrial NLRP3 inflammasomes, which promote AF occurrence (Zhang et al., 2022). This pathway is supported by evidence from animal experiments showing that elevated serum LPS contributes to AF development (Sun et al., 2016) and by clinical trials demonstrating that increased serum LPS predicts adverse events in AF patients (Pastori et al., 2017). Furthermore, comparative studies involving fecal microbiota transplantation in rodents have revealed that younger rats exhibit higher LPS levels and NLRP3 expression after transplantation than older rats. Inhibition of NLRP3 activation using MCC950 effectively suppresses atrial fibrosis and mitigates AF occurrence (Zhang et al., 2022). In summary, these findings position the LPS/NLRP3 axis as a modifiable risk pathway in age-related AF, with MCC950 demonstrating therapeutic potential (Figure 1).

LPS is transferred via LPS-binding protein and cluster of differentiation 14 to activate toll-like receptor 4 co-receptor myeloid differentiation protein 2 (TLR4-MD2) on cell membranes (Ryu et al., 2017), which subsequently activates nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) within cells (Zhao et al., 2021). NF-κB translocates to the nucleus, promoting transcription of interleukin (IL)-1β/IL-18-related genes and generation of pro-IL-1β/pro-IL-18 (Ajoolabady et al., 2022). In the presence of ROS, inactive NLRP3 (which consists of leucine-rich repeat domains, a central nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain, and an amino-terminal pyrin domain) assembles with caspase-1 and the caspase recruitment domain to form the active NLRP3 inflammasome (Lamkanfi and Dixit, 2014). This complex activates caspase-1, which subsequently cleaves pro-IL-1β/pro-IL-18 into active IL-1β/IL-18 (Cordero et al., 2018; Ajoolabady et al., 2022). Extracellular IL-1β/IL-18 then activates atrial fibroblasts, thus promoting atrial fibrosis and ultimately leading to AF (Ajoolabady et al., 2022). Additionally, LPS can directly enter the cytoplasm to activate caspase-11 (Vanaja et al., 2016), leading to NLRP3-independent activation of IL-1β/IL-18, while ROS can also directly activate NLRP3 inflammasomes to promote atrial fibrosis (Kelley et al., 2019). All in all, these pathways converge on the release of IL-1β/IL-18, creating a fibrotic substrate for AF through sustained fibroblast activation (Figure 1).

3.1.3 Senescence-associated secretory phenotype and aging

NLRP3-activated IL-1β promotes the production of the SASP (Figure 1), a concept first introduced by Coppe et al. (2008). SASP comprises various signaling molecules—including cytokines, chemokines, growth factors, and proteases—released by senescent cells that can impact nearby cells (Acosta et al., 2013; Coppe et al., 2010). It is associated with aging and age-related diseases (Watanabe et al., 2017; Birch and Gil, 2020) due to its link to the chronic inflammation observed in cellular senescence (Franceschi et al., 2000), a process that occurs early in patients with cardiometabolic disease and causes significant physiological damage (Liberale et al., 2020). SASP consists mainly of pro-inflammatory cytokines and extracellular matrix remodeling factors. It can reinforce cellular senescence through autocrine signaling in senescent cells themselves and induce it in neighboring cells via paracrine signaling (Gorgoulis et al., 2019; He and Sharpless, 2017; Acosta et al., 2013; Lujambio et al., 2013). This paracrine signaling may lead to abnormal senescence in previously unaffected cells, triggering additional SASP generation (Acosta et al., 2013). For example, SASP from cardiac myocytes can activate cardiac fibroblasts and impair endothelial cell function (Anderson et al., 2019). Conversely, SASP can also attract natural killer cells and macrophages, promoting the clearance of the very senescent cells that release it (Krizhanovsky et al., 2008), which is a crucial mechanism in suppressing cancer development (Eggert et al., 2016). Moreover, SASP contributes to the maintenance and intensification of inflammation, leading to chronic systemic inflammation even in the absence of disease (Ferrucci and Fabbri, 2018; Bandeen-Roche et al., 2006), which, in turn, induces senescence in other cells. Therefore, SASP may mediate the harmful effects of senescent cells in age-related diseases (Lopes-Paciencia et al., 2019; Coppe et al., 2010). Its production can be triggered by sustained DNA damage (Takahashi et al., 2012) and is also linked to the accumulation of the cGAS–STING pathway. This occurs when cytoplasmic DNA—which accumulates due to the reduced activity of cytoplasmic DNA enzymes (Takahashi et al., 2018)—activates immune responses and enhances SASP production (Gluck et al., 2017; Faget et al., 2019).

SASP is a key feature of cellular senescence that involves multiple signaling pathways. One crucial pathway is mediated by IL-1β, as evidenced by IL-1β knockout mice showing decreased SASP production (Yoshimoto et al., 2013). Senescent cells activate pathways including cGAS–STING, NF-κB, and C/EBPβ (CCAAT box/enhancer-binding protein beta), leading to the secretion of various inflammatory substances that constitute the SASP. The SASP plays a dual role, promoting both tissue healing and inflammation (Demaria et al., 2014; Coppe et al., 2008). Given its involvement in age-related diseases and tissue damage, inhibiting SASP has emerged as a therapeutic strategy. Studies have shown that SASP inhibition via the JAK/STAT pathway can reduce inflammation (Griveau et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020) and restore insulin sensitivity (Xu et al., 2016). Similarly, inhibiting the mTOR signaling pathway with rapamycin can significantly decrease SASP levels, thereby reducing inflammation and senescence (Weichhart, 2018; Wang et al., 2017).

3.1.4 Sirtuin 1 and senescence

As mentioned earlier, NLRP3 activation causes inflammation in atrial cells, a process that can be inhibited by certain signaling molecules such as SIRT1. The sirtuins are a group of NAD-dependent deacetylases and ADP-ribosyltransferases (Wang et al., 2021), comprising seven known types (SIRT1–7), that primarily facilitate histone deacetylation and are linked to age-related diseases (Haigis and Sinclair, 2010; Almeida and Porter, 2019). Among them, SIRT1—an NAD + -dependent deacetylase that is highly conserved across species—has been extensively studied for its critical role in regulating aging and lifespan-associated transcription factors through substrate deacetylation (Imai et al., 2000; Chen et al., 2020; Almeida and Porter, 2019; Jin et al., 2024; Ramis et al., 2015). While different studies have reached contrasting conclusions regarding its role in promoting or reducing atrial fibrosis through different mechanisms, the evidence generally supports its protective functions. Mouse studies show that decreased SIRT1 levels can induce oxidative stress (Imai and Guarente, 2014), whereas SIRT1 activation alleviates aging-related processes, including oxidative stress, inflammation, and cell apoptosis (Campisi et al., 2019). Furthermore, SIRT1 maintains the redox balance in cardiac cells during ischemia/reperfusion, thereby delaying cellular senescence (Zhang et al., 2020), and it inhibits dynamin-related protein 1 via peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha, thus reducing mitochondrial fission and extending cell lifespan (Ding et al., 2018). As a deacetylase, SIRT1’s active site binds NAD+ and NADH. An imbalance in the NAD+/NADH ratio prompts SIRT1 to deacetylate proteins in key signaling pathways—including adenosine 5′-monophosphate (AMP)-activated protein kinase (AMPK) (Figure 2) (Park et al., 2016), forkhead box O transcription factors (FOXOs) (Figure 1) (Jenwitheesuk et al., 2018), p53 (Figure 3) (Tran et al., 2014), NF-κB, and sirtuins (Figure 1) (Nopparat et al., 2017; Yi and Luo, 2010; Almeida and Porter, 2019)—thereby regulating cellular senescence. Through these pathways, SIRT1 exerts protective effects on myocardial cells. It is required for AMPK activation and regulates mitochondrial function via the AMPK pathway (Price et al., 2012), thereby promoting autophagy and protecting against oxidative stress (Luo et al., 2019). This mechanism is exemplified by metoprolol, which activates the SIRT1–AMPK pathway to alleviate impaired myocardial energy metabolism (Sun et al., 2017). Furthermore, SIRT1 controls FOXO transcription via histone deacetylation to prevent oxidative stress damage (Chen et al., 2021a), modulates apoptosis by inhibiting p53 and regulating p21 (Figure 3), and attenuates inflammation while reducing oxidative stress via inhibition of the NF-κB pathway (Figure 1) (Yi and Luo, 2010; Kauppinen et al., 2013; Zhou et al., 2018).

Figure 2. Mammalian target of rapamycin signaling pathway and senescence. Both the NLRP3 inflammasome and IGF-1 have the capacity to initiate the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. However, it is noteworthy that the activity of IGF-1 is hindered by the presence of Klotho. Conversely, the activation of mTORC1 is inhibited by LKB1 and SIRT1 through the modulation of the AMPK pathway. Abbreviations: AKT, protein kinase B; AMPK, adenosine 5′-monophosphate-activated protein kinase; GDP, guanosine diphosphate; GTP, guanosine triphosphate; IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor; LKB1, liver kinase B1; mTORC1, mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1; NLRP3, NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; Rheb, RAS homolog enriched in brain; SIRT1, sirtuin 1; TSC1/2, tuberous sclerosis complex 1 and 2. Created with BioRender.com.

Figure 3. Alterations in cell-cycle-related genes and ERK signaling pathway activation. Perturbations in the expression levels of cell-cycle-related genes, namely, P16, P21, and P53, caused by various influences, including ERK1/2, TGF-β1, and SIRT1, contribute to the process of cellular senescence and serve as precursors to the onset of atrial fibrillation. Abbreviations: E2F, E2 transcription factor; ERK1/2, extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2; EZH2, enhancer of zeste homolog 2; H3K27me3, histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation; IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; MDM2, murine double minute 2 protein; MYC, oncogenic transcription factor c-myc; PAI-1, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1; Rb, retinoblastoma protein; RSK, ribosomal S6 kinase; SASP, senescence-associated secretory phenotype; SIRT1, sirtuin 1; TGF-β1, transforming growth factor beta 1; CDK 4/6, cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6. Created with BioRender.com.

SIRT1 reduces NLRP3 inflammasome activation through the AKT signaling pathway (Han et al., 2020b). Consistently, aged NLRP3 knockout mice exhibit inhibition of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, improved autophagy, increased SIRT1 protein expression, and delayed cardiac cell senescence (Figure 2) (Marin-Aguilar et al., 2020). Furthermore, SIRT1 can alleviate cardiac fibrosis by negatively regulating the small mothers against decapentaplegic (SMAD) pathway, an anti-fibrotic effect potentially mediated through modification of SMAD2/3 and its influence on transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) signaling (Figure 1) (Bugyei-Twum et al., 2018).

Numerous studies have established a connection between SIRT1 and AF occurrence. The nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (Nampt)/NAD/SIRT1 axis, which is a key modulator of cellular senescence, is implicated in this process; decreased Nampt and NAD expressions are associated with aging and obesity, and partial Nampt deficiency in mice promotes diastolic calcium leakage and high-fat diet-induced AF (Feng et al., 2020). Furthermore, decreased SIRT1 expression has been observed in the atrial tissues of elderly humans and aged rats. Atrial-specific SIRT1 knockout mice developed atrial dilation and increased AF susceptibility. Mechanistically, acetyl-proteomics revealed that SIRT1 deficiency promotes receptor-interacting protein kinase 1 acetylation, triggering mixed-lineage kinase domain-like protein phosphorylation and atrial necroptosis. The necroptosis inhibitor necrosulfonamide reversed atrial remodeling and AF susceptibility in SIRT1-deficient mice, while resveratrol prevented age-related AF by activating SIRT1 and suppressing necroptosis (Jin et al., 2024). Elevated plasma homocysteine levels also contribute to atrial fibrosis via interaction between transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily C3 (TRPC3) and SIRT1, further underscoring that SIRT1 downregulation is a contributing factor in AF (Han et al., 2020a). Various agents, including fenofibrate, Dingjifumai Tang, resveratrol, curcumin, naringenin, and SRT1720, have been identified as SIRT1 activators (Liu et al., 2016; Liang et al., 2021; Howitz et al., 2003; Xiao et al., 2016; Testai et al., 2020; Mitchell et al., 2014).

However, research on whether SIRT1 activation reduces AF occurrence has yielded conflicting results. A study investigating the effect of B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) on atrial fibrosis in mice found that tumor necrosis factor-alpha enhances fibrosis by increasing matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) expression and collagen accumulation (Tsai et al., 2019). Since BNP also stimulates MMP-2 expression in human atrial myofibroblasts and SIRT1 inhibition significantly reduces this BNP-induced expression, these findings suggest SIRT1 may mediate BNP’s regulation of MMP-2 (Tsai et al., 2019). This implies that SIRT1 activation could potentially promote atrial fibrosis, highlighting the need to clarify its association with AF.

3.1.5 mTOR signaling pathway and senescence

In addition to activating caspase-1, NLRP3 activates the mTOR signaling pathway. Rapamycin, an antifungal antibiotic extracted from Streptomyces hygroscopicus (Vezina et al., 1975), was later found to selectively inhibit the mTOR protein—a serine/threonine kinase of the PI3K-related kinase family (Keith and Schreiber, 1995)—leading to its designation as the ‘mammalian target of rapamycin’ (Brown et al., 1994; Sabatini et al., 1994). mTOR exists in two complexes, mTORC1 and mTORC2. Research across various organisms, including nematodes, fungi, and insects, has associated mTOR activation with aging, while its inhibition extends lifespan (Vellai et al., 2003). This is also observed in mammals, where depleting or inhibiting mTORC1 prolongs the lifespan and maintains health (Wu et al., 2013; Bitto et al., 2016). Mechanistically, mTOR inhibition restores age-related declines in autophagy (Hansen et al., 2018), and mTORC1 promotes stem-cell exhaustion (Yilmaz et al., 2012) and contributes to the functional decline of healthy tissues (Nacarelli et al., 2016; Herranz et al., 2015; Laberge et al., 2015). Although rapamycin has been used to extend the lifespan in model organisms (Bjedov et al., 2010; Robida-Stubbs et al., 2012), its clinical anti-aging application is limited by adverse effects. Intermittent administration may help mitigate these (Arriola Apelo et al., 2016a; Arriola Apelo et al., 2016b), and low-dose rapamycin may even exert immunoenhancing effects despite its immunosuppressant properties (Figure 2) (Mannick et al., 2018).

mTOR is linked not only to aging but also to AF occurrence. Activation of the AKT/mTOR pathway was observed in a rodent AF model (Zou et al., 2016), and gene set enrichment analysis of human atrial tissue confirmed the mTOR pathway’s association with AF development, although a causal relationship requires further validation (Ebana et al., 2019). mTOR is believed to promote AF through inflammation and structural remodeling. In human AF models, atrial cells show increased signaling in pathways such as mitogen-activated protein kinase and mTOR (Wei et al., 2020). In mice, NLRP3 inhibition suppresses the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, thus protecting cardiac function and extending lifespan (Marin-Aguilar et al., 2020). Similarly, while insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) activates the PI3K pathway, Klotho inhibits it, thereby reducing mTOR activation (Dalton et al., 2017; Kurosu et al., 2005). Furthermore, inhibiting the ERK1/2 (extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2) and AKT/mTOR pathways in AF mice reduces the recruitment of CD3+ T lymphocytes and F4/80+ macrophages, thereby mitigating atrial inflammation and structural remodeling (Liu et al., 2021). Loss of liver kinase B1 (LKB1) in mice leads to heart failure and AF, accompanied by increased mTOR phosphorylation and alterations in the AMPK and mTOR/p70S6K/eEF2 pathways that contribute to cardiac hypertrophy and dysfunction (Figure 2) (Ikeda et al., 2009).

3.2 DNA methylation and changes in intracellular ion balance

3.2.1 DNA methylation

DNA methylation is a vital epigenetic mechanism for gene regulation and serves as an important determinant of an organism’s epigenetic age (Lee et al., 2016). It involves the addition of methyl groups to specific nucleotides, typically cytosine in cytosine–phosphate–guanine islands, without altering the DNA sequence (Movassagh et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2018). This process is catalyzed by DNA methyltransferases, which transfer methyl groups from S-adenosylmethionine to the 5′carbon of cytosine (Hannum et al., 2013; Simpkin et al., 2016). DNA methylation alters gene expression by modifying DNA-binding proteins and chromatin structure (Unnikrishnan et al., 2019), primarily silencing gene promoters and regulatory regions (Donate Puertas et al., 2017). Its effect depends on the location: high promoter methylation inhibits transcription, while low promoter methylation promotes it (de Mendoza et al., 2022). During aging, global cytosine–phosphate–guanine methylation decreases outside promoter regions, while methylation levels at promoter regions increase (Day et al., 2013; Calvanese et al., 2009).

DNA methylation regulates the expression of calcium handling proteins and contributes to the development of AF. For instance, tumor necrosis factor-alpha reduces the expression of sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2 (SERCA2)—a protein responsible for transporting calcium ions into the sarcoplasmic reticulum during cardiac myocyte relaxation—via DNA methyltransferase-1-mediated promoter methylation (Kao et al., 2010). Studies suggest that JUN N-terminal kinase 2 activates SERCA2, thereby enhancing sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium uptake (Yan et al., 2021). Furthermore, DNA methylation affects ryanodine receptor 2 (RyR2) expression. In AF patients, increased methylation in the promoter of the long non-coding RNA LINC00472 elevates the levels of competing RNA miR-24, which directly binds and negatively regulates both LINC00472 and junctophilin-2. Reduced junctophilin-2 expression disrupts RyR2 function and is associated with AF occurrence (Figure 4) (Wang et al., 2019).

Figure 4. DNA methylation and changes in intracellular ion balance. DNA methylation interferes with the expression of genes associated with LINC00472 and SERCA2, leading to diminished quantities of sarcoplasmic reticulum-resident RYR2 and SERCA2. Consequently, this disruption gives rise to an altered equilibrium of cellular calcium ions, thereby rendering myocardial cells more susceptible to excitatory stimuli, ultimately promoting the occurrence of atrial fibrillation. Abbreviations: CaMKIIδ, calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II delta; DNMT1, DNA methyltransferase 1; ERK1/2, extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2; HDAC6, histone deacetylase 6; IP3, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate; JNK2, JUN N-terminal kinase 2; JP2, junctophilin-2; MCU, mitochondrial calcium uniporter; NCX, sodium–calcium exchanger; miR-24, miRNA-24; NLRP3, NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3; ROS, reactive oxygen species; RyR2, ryanodine receptor 2; SERCA2, sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2; SR, sarcoplasmic reticulum; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Created with BioRender.com.

3.2.2 Alterations in calcium-handling proteins and the occurrence of ectopic excitation

The mechanism triggering AF involves abnormal stimulation of atrial myocardial cells and extends to connected blood vessels, a process associated with changes in ion channels (Nattel et al., 2007; Christ et al., 2004). Key ion channels impacting atrial impulse generation include sodium, potassium, and calcium channels, with age-related changes in calcium channels playing a crucial role in ectopic activity (Dridi et al., 2020; Christ et al., 2004). Myocardial contraction relies on calcium-induced calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (Figure 4). During contraction, calcium influx through L-type channels activates RyR2 channels on the sarcoplasmic reticulum, triggering a rapid calcium release that drives contraction (Bers, 2014). During diastole, RyR2 channels are normally closed, and intracellular calcium is sequestered by SERCA2 or extruded via the sodium–calcium exchanger (Bers, 2014). The molecular mechanism for RyR2 generating abnormal impulses involves diastolic calcium leakage from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (Nattel et al., 2020). In AF-susceptible individuals, ROS-induced sarcoplasmic reticulum stress can activate JUN N-terminal kinase (Davis, 2000), which, in turn, activates calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II delta (CaMKIIδ), promoting RyR2 dysfunction (Chiang et al., 2014; Yan et al., 2018b) and diastolic calcium leakage (Yan et al., 2021; Yan et al., 2018b). A human study corroborated this, finding that senescent CD8+ T cells in AF patients’ left atrial appendage secrete interferon-γ, activating the CaMKII/RyR2 pathway. This increased sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium leakage caused action potential alternans, significantly decreased conduction velocity, and markedly prolonged AF induction and duration, suggesting that RyR2-mediated leakage contributes to AF development (Xiang et al., 2024). RyR2 channel leakage during cardiac diastole elevates cytosolic calcium concentration in myocardial cells, thereby increasing myocardial excitability and contributing to arrhythmias (Bers, 2014; Yan et al., 2021). Atrial myocardial cells exhibit stronger SERCA and NCX functionality than ventricular cells, leading to higher sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium levels (Walden et al., 2009). However, this finding stems from rodent studies, and given the species’ differences in calcium handling dependence, it is uncertain whether it fully translates to human cardiomyocytes. When stimulated, RyRs become more prone to spontaneous calcium leakage (Chelu et al., 2009; Venetucci et al., 2008). This leaked calcium can bind the mitochondrial calcium uniporter, leading to mitochondrial calcium accumulation, ROS release, and subsequent NLRP3 inflammasome activation (Masters et al., 2010). The activated NLRP3 inflammasome then enhances CaMKIIδ-dependent RyR2 phosphorylation and pro-arrhythmic calcium activity (Heijman et al., 2020; Chelu et al., 2009; Neef et al., 2010). Animal experiments confirm that this CaMKIIδ-mediated calcium dysregulation underlies AF (Li et al., 2014). Although these calcium channel alterations collectively contribute to AF, caution is warranted when extrapolating these findings to humans pending clinical confirmation (Figure 4).

Phosphorylation of striated preferentially expressed protein kinase reduces RyR2-mediated release of calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum, and decreased phosphorylation of striated preferentially expressed protein kinase promotes the occurrence of AF (Campbell et al., 2020). Therefore, RyR2 not only influences the initiation of AF but also its maintenance.

3.2.3 Changes in intracellular cytoskeleton structure

As mentioned earlier, sarcoplasmic reticulum stress increases calcium accumulation in cardiac myocytes. This elevated intracellular calcium concentration induces alterations to the cytoskeleton in atrial myocytes. The cytoskeleton, composed of microtubules, microfilaments, and intermediate filaments, provides structural support, determines organelle distribution, and participates in inter-organelle transport (Dogterom and Koenderink, 2019). Elevated cytosolic calcium can activate histone deacetylase 6, which deacetylates and depolymerizes α-tubulin, thereby degrading microtubules (Zhang et al., 2014). Animal experiments have demonstrated that histone deacetylase inhibition can reverse cardiac fibroblast activation and improve diastolic dysfunction (Travers et al., 2021). Diastolic dysfunction, which shares risk factors with AF, promotes arrhythmogenesis through mechanisms such as increased atrial afterload, myocardial stretch, and wall stress (Rosenberg and Manning, 2012). The frequent coexistence of AF and diastolic dysfunction suggests shared underlying pathological mechanisms (Packer et al., 2020). Structural cytoskeletal abnormalities impede inter-organelle communication; for instance, impaired microtubule function can disrupt mitochondrial mechanosensing, leading to abnormally high intracellular calcium levels and promoting ectopic excitations (Figure 4) (Miragoli et al., 2016).

3.2.4 Disruption of protein homeostasis in atrial cardiomyocytes

Protein homeostasis is essential for normal physiological function and organismal development and aging; its disruption can lead to various metabolic, neurodegenerative, and cardiovascular diseases (Balch et al., 2008). AF has been associated with abnormalities in the protein quality-control system (Brundel et al., 2022; Brundel et al., 2006a), which comprises chaperone proteins (e.g., heat shock proteins [HSPs]), the ubiquitin–proteasome system, and the autophagy system (Henning and Brundel, 2017).

Rapid atrial excitation can cause myolysis, a process against which HSPs can confer protection (Brundel et al., 2006b). Under physiological conditions, HSPs localize to microtubules and stabilize the cytoskeleton (Hu et al., 2019). At AF onset, HSP27 expression increases in atrial myocytes but gradually depletes with AF prolongation, leading to myocyte dissolution (Brundel et al., 2006a). Therefore, increasing HSP expression may protect atrial cell function and represent a novel strategy to prevent clinical AF (Brundel et al., 2006a; Brundel et al., 2008).

Autophagy, the lysosomal degradation of cellular components (Mizushima and Komatsu, 2011), includes macro-autophagy, micro-autophagy, and chaperone-mediated autophagy (Mizushima and Levine, 2020). AF induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and activates macro-autophagy; however, excessive activation in atrial myocytes promotes atrial remodeling. Conversely, inhibiting intracellular autophagy in both animal and human atria can prevent AF-induced cardiac contractile dysfunction (Wiersma et al., 2017). In summary, disrupted protein homeostasis during cellular senescence contributes to AF development.

3.2.5 Alterations in gap junction proteins of atrial myocytes

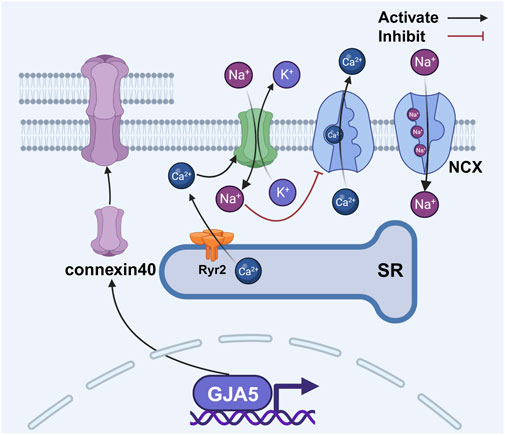

Coordinated atrial contraction relies on gap junctions composed of connexin proteins in cardiac myocytes. The atria express connexin43 and connexin40, with the latter being more abundant in the right atrium (Desplantez, 2017; Leybaert et al., 2017; van der Velden and Jongsma, 2002). Structurally, six connexins form a hemichannel, and two hemichannels connect to create a gap junction (Chaldoupi et al., 2009). These junctions enable rapid electrical synchronization between adjacent atrial myocytes (Rohr, 2004), but external stressors can alter them, causing conduction delays (Saffitz, 2006; Yan et al., 2018a) that promote reentrant circuits. Changes in the expression and distribution of connexin40 and connexin43 contribute to atrial conduction heterogeneity (Ryu et al., 2007; Choi et al., 2012). During cellular senescence, gap junction proteins undergo changes, making them a proposed therapeutic target for AF (Spach and Starmer, 1995; Sykora et al., 2023). A large meta-analysis of over 180,000 AF patients implicated cell junction genes such as Plakophilin-2 in AF pathogenesis, suggesting that age-related functional decline of these genes may drive atrial fibrosis and electrical remodeling, ultimately elevating AF risk (Roselli et al., 2025). Supporting this, studies in a mouse model of heart failure revealed decreased connexin43 and connexin40 expression, contributing to abnormal signal conduction (Tong et al., 2022). Mutations in the GJA5 gene (encoding connexin40) may predispose individuals to idiopathic AF by impairing gap junction assembly or electrical coupling (Gollob et al., 2006). Conversely, animal research demonstrates that gene transfer-mediated overexpression of connexin40 and connexin43 can reduce AF occurrence (Figure 5) (Igarashi et al., 2012).

Figure 5. Changes in gap junction proteins between atrial myocytes disrupt the balance of intracellular calcium. The activation of RyR2 results in an elevation of intracellular calcium concentration, thereby facilitating the activation of connexin 43 hemichannels. This activation, albeit indirectly, serves to modulate the activity of the NCX, leading to further augmentation of intracellular calcium levels. Abbreviations: NCX, sodium–calcium exchanger; RyR2, ryanodine receptor 2; SR, sarcoplasmic reticulum. Created with BioRender.com.

In addition to gap junctions, connexin hemichannels also play a role in AF. Activation of RyR2 increases intracellular calcium concentration, which promotes the opening of connexin43 hemichannels (Lissoni et al., 2021). These hemichannels function as non-selective pores, allowing potassium efflux and sodium influx. The resulting increase in intracellular sodium levels inhibits the sodium–calcium exchanger (NCX), leading to further calcium accumulation (Fakuade et al., 2021). This elevated calcium facilitates sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium release and delays atrial repolarization, thus collectively increasing atrial excitability and contributing to AF occurrence (Figure 5) (Voigt et al., 2012).

3.3 Alterations in cell-cycle-related genes and activation of the ERK signaling pathway

3.3.1 P16 signaling pathway

P16 (cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A or P16INK4A) regulates the cell cycle by inhibiting the cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) 4/6 complex. This inhibition prevents retinoblastoma protein (Rb) phosphorylation and the dissociation of the Rb–E2F complex, thereby suppressing E2F transcriptional activity and inducing cell cycle arrest and senescence (Kumari and Jat, 2021). P16 levels increase exponentially with age in various stem cell tissues and mouse models, limiting regenerative capacity and suggesting an acceleration of senescent cell accumulation over time (Molofsky et al., 2006; Krishnamurthy et al., 2006; Janzen et al., 2006; Krishnamurthy et al., 2004; Burd et al., 2013; Herbig et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2009). P16 is also involved in tissue injury repair, with its promoter activating after damage and silencing upon repair (Demaria et al., 2014; Sorrentino et al., 2014). As a key senescence marker alongside p21 (Gasek et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2022), p16 can be induced by ROS and other stressors (Chen et al., 2015). For instance, TGF-β1 increases ROS production to upregulate both p16 and p21, leading to stem cell apoptosis (Fan et al., 2019). While p53 initiates senescence, p16 maintains it (Stein et al., 1999; Alcorta et al., 1996), a cooperation underscored by their shared downstream target, the E2F transcription factor (Rowland et al., 2002). Mechanistically, p16 binding to CDK4/6 disrupts its interaction with cyclin D, blocking cell cycle initiation (Pavletich, 1999). Sustained p16 expression stably inhibits proliferation by maintaining Rb activation and E2F suppression, arresting cells in the G1 phase (Bazarov et al., 2012; Sherr and McCormick, 2002) and influencing senescence-associated heterochromatin foci formation (Narita et al., 2003). Cells expressing p16 undergo prolonged, telomere-length-independent cell cycle arrest, which is characteristic of oncogene-induced senescence (Figure 3) (Gray-Schopfer et al., 2006). Epigenetically, p16 is negatively regulated by histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation, a modification promoted by the enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (Al-Hasani et al., 2022; Jacobs et al., 1999; Mirzaei et al., 2022).

P16 plays a dual role in both aging and AF. Expression of p53, p16, and tissue factor is significantly increased in the right atrial appendage of AF patients, and since p53 and p16 are markers of cellular senescence, this indicates that AF progression is associated with cellular senescence (Jesel et al., 2019). P16 may promote AF by facilitating atrial fibrosis. Analysis of left atrial appendage tissue from mice with AF shows increased fibrosis in regions positive for senescence-associated beta-galactosidase and p16 (Xie et al., 2017). Research in diabetic mouse models found that accumulation of advanced glycation endproducts increases p16/Rb protein expression, increases the number of senescence-associated β-galactosidase-positive cells, prolongs action potential duration, and increases AF susceptibility. Critically, intervening in the p16/Rb pathway reverses these effects, suggesting that it could be a new therapeutic strategy (Zheng et al., 2022). However, given the differences in electrophysiology (e.g., shorter action potential durations in humans), further human studies are needed to confirm this hypothesis. Supporting the clinical relevance, analysis of intraoperative left atrial appendage tissue from AF patients revealed upregulation of p16, p21, and p53, with p21 identified as an independent predictor of early AF recurrence (Adili et al., 2022). Although numerous studies associate p16 upregulation with AF occurrence, the underlying mechanisms remain unclear.

3.3.2 P21 signaling pathway

P21 (cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1) is a gene involved in aging and cancer that inhibits cyclin-dependent kinase complexes to regulate the cell cycle, DNA replication, and repair (Kumari and Jat, 2021). Located on chromosome 6p21.2, it encodes a protein that, when expressed, induces G1-phase cell cycle arrest (Xiong et al., 1993; Yoshikawa et al., 2010). Its function depends on subcellular localization: nuclear p21 inhibits cell division and acts as a tumor suppressor, whereas cytoplasmic p21 promotes tumor growth (Maria Teresa and Stefania, 2012; Romanov et al., 2012; Romanov and Rudolph, 2016). P21 promotes cellular senescence by interacting with various pathways. For instance, TGF-β1 increases ROS production to upregulate p21 and induce stem cell apoptosis (Fan et al., 2019), and the ERK1/2 pathway can activate p21 to trigger premature senescence (Cammarano et al., 2005). Activated ERK1/2 promotes senescence by modulating proteins such as ribosomal S6 kinase, Sprouty, and c-myc (Campaner et al., 2010; Sun et al., 2018). It also interacts with other pathways, such as promoting SASP production via NF-κB activation (Catanzaro et al., 2014), enhancing mTOR signaling to help sustain senescence (Leontieva and Blagosklonny, 2010; Laberge et al., 2015) and coinciding with the gradual activation of the tumor-suppressor p38 (Kim et al., 2003; Freund et al., 2011). Notably, mTOR signaling regulates SASP, and its inhibition with rapamycin can reduce SASP, thereby alleviating inflammation and senescence (Weichhart, 2018; Wang et al., 2017). Klotho delays aging by inhibiting IGF-1 signaling and reducing ERK1/2 phosphorylation (Dalton et al., 2017; Kurosu et al., 2005; Wolf et al., 2008). SIRT1 can inhibit p53 (Tran et al., 2014), IGF-1 can inhibit SIRT1 (Tran et al., 2014), and Klotho can inhibit the action of IGF-1 (Wolf et al., 2008). Therefore, Klotho can indirectly inhibit the activation of p53, thereby delaying cellular senescence (Figure 3).

Apart from its association with aging, p21 is also linked to AF occurrence. A human study found increased senescent cell area in the left atrial appendage (LAA) of AF patients, with those experiencing recurrence exhibiting higher p21 mRNA levels. Multivariate analysis confirmed p21 as an independent predictor of early AF recurrence (Adili et al., 2022). Further experiments demonstrated that inhibiting p21 reduces tachycardia-pacing-induced cellular senescence, decreases the release of inflammatory factors (IL-1β and IL-6), and partially restores sarcoplasmic reticulum protein expression, suggesting a key role for p21 in AF-related senescence and electrical remodeling (Adili et al., 2022). Although the exact mechanisms are not fully understood, p21 is considered to contribute to AF by regulating atrial remodeling. For instance, thrombin-induced upregulation of p21 and p16 promotes cellular senescence in atrial endothelial cells, leading to atrial remodeling (Hasan et al., 2019; Jansen et al., 2025).

3.3.3 P53 signaling pathway

P53, a tumor suppressor gene, plays a central role in cellular senescence by maintaining genomic integrity. It facilitates DNA repair and induces cell cycle arrest to prevent the proliferation of damaged cells. Upon DNA damage, the p53–p21 and p16–pRb axes are activated, leading to cell cycle arrest and initiating processes for DNA repair, cellular senescence, or apoptosis (Ou and Schumacher, 2018). Consequently, lowered p53 levels can result in genomic instability (Williams and Schumacher, 2016), while premature aging syndromes with defective DNA repair are often characterized by genomic instability and increased p53 activity (Reinhardt and Schumacher, 2012). P53 thus exhibits a dual function, balancing tumor-suppressive and aging-promoting activities (Timofeev et al., 2020). For instance, phosphorylation of its DNA-binding domain can reduce tumor-suppressive activity and prevent senescence, whereas p53 activation can also induce senescence and apoptosis, contributing to organismal degeneration and loss of regenerative capacity (Timofeev et al., 2020; Schumacher et al., 2021; Serrano et al., 1997).

Mitochondrial dysfunction is a key component of cellular senescence (Wiley et al., 2016). P53 can exacerbate this by suppressing peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha and 1-beta, leading to increased ROS production. This, in turn, activates p53 through a feedback loop (Sahin and DePinho, 2012). Once established, this cycle drives continuous cellular senescence via the p21 and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) pathways (Dulic et al., 1994; Kortlever et al., 2006; El-Deiry et al., 1993). Murine double minute 2 protein is the most well-known p53 inhibitor (Haupt et al., 1997; Zhu et al., 2022), although no clinical drugs currently target this interaction (Figure 3).

Interestingly, aside from its role in aging, p53 is also associated with AF occurrence. Bioinformatics analysis of atrial tissue from AF patients revealed differential gene expression, implicating pathways including the “p53 pathway,” thus suggesting its involvement in AF development (Chiang et al., 2015). Supporting this, analysis of right atrial appendage tissue from cardiac surgery patients showed significantly increased expression of p53 and p16 in AF patients, with multivariate analysis identifying them as the sole predictors of AF (Jesel et al., 2019). Furthermore, p53 upregulation was confirmed in the left atrial appendage of AF patients (Adili et al., 2022). These findings consistently demonstrate a close connection between AF and cellular senescence in atrial cells. Mechanistically, studies using HL-1 cell models demonstrated that telomerase reverse transcriptase regulates calcium-handling proteins (SERCA2a, CaV1.2, and NCX1.1) via the p53/PGC-1α pathway. This pathway is aberrantly activated during aging, directly contributing to age-related atrial electrical remodeling and calcium dysregulation. Telomerase reverse transcriptase silencing recapitulated key features of aged cardiomyocytes, including calcium overload, mitochondrial dysfunction, and electrophysiological disturbances—core pathological mechanisms underlying age-related AF (Li et al., 2024).

Studies have indicated a connection between p53 and AF occurrence, though the exact causal relationship and underlying mechanisms remain uncertain. Researchers have identified three genes involved in atrial fibrosis—SERPINE1/PAI-1, TIMP3, and DCN—with PAI-1 being the most significant. Molecular experiments have demonstrated that p53 regulates PAI-1, and this relationship is supported by the increased expression of both p53 and PAI-1, which is observed in atrial tissue from AF patients. These findings suggest that the p53/PAI-1 signaling axis may play a role in the pathophysiology of AF (Li et al., 2021).

4 Clinical importance and future directions

This review systematically examines the link between AF and cardiomyocyte senescence. It explores three key mechanisms: inflammatory activation, calcium handling abnormalities, and cell cycle dysregulation. The analysis reveals how aging promotes AF through multiple pathways. Moreover, the review identifies several potential therapeutic targets. These include mitochondrial ROS, NLRP3 inflammasome, and SIRT1/mTOR pathways. These targets serve as both senescence markers and novel intervention points for AF. The findings provide crucial theoretical support for developing anti-aging therapies against AF.

There are several important unanswered questions regarding the role of senescence of atrial myocytes in AF. First, multiple signaling molecules are associated with both AF and cellular senescence, but they are part of complex networks rather than individual pathways. Current research on AF and atrial myocyte senescence is limited by fragmented mechanistic studies, inadequate models, poor cell-type specificity, and challenges in clinical translation. Identifying the key pathway that promotes AF and aging requires further research because interventions targeting these pathways are still under exploration. Second, aging is a complex phenomenon involving intricate alterations in intracellular signaling pathways. Cardiac tissue consists of various cell types, including cardiac myocytes, fibroblasts, conduction bundles, neural tissue, and inflammatory cells. Senescence has distinct effects in each cell type, making it challenging to fully comprehend the relationship between aging and AF. Most studies focus on tissues when investigating AF and aging, leaving uncertainty regarding the specific cell type for which senescence has the greatest impact on AF. The specific cell type that plays a major role in the occurrence of AF awaits clarification. Third, promotion of AF involves multiple cell types in the heart, including fibroblasts and endothelial cells, and senescence of atrial myocytes alone may not be sufficient to cause AF. The relationship between various cell types in the occurrence and maintenance of AF requires further investigation.

5 Conclusion

This review proposes that atrial myocyte senescence is a central driver in the pathogenesis of AF, moving beyond the traditional focus on chronological age. The evidence synthesizes into a coherent senescence–AF axis. The interplay of key mechanisms—including mitochondrial dysfunction, NLRP3 inflammasome activation, the SASP, and dysregulation of SIRT1 and mTOR signaling—creates a pro-arrhythmic substrate. This is further compounded by epigenetic alterations, disrupted calcium handling, and the action of cell cycle inhibitors such as p16, p21, and p53, which collectively promote electrical and structural remodeling. These pathways converge to facilitate both the triggers and maintenance of AF. Targeting these fundamental aging mechanisms—such as with SIRT1 activators, NLRP3 inhibitors, or mTOR modulators—holds significant promise for developing novel therapeutic strategies. Future research must delineate the dominant pathways and clarify the contribution of senescence in specific cardiac cell types to translate these insights into effective anti-arrhythmic treatments. Moreover, translating the senescence–AF axis from a concept to clinical practice is a paramount future goal, necessitating interdisciplinary collaboration to advance therapies that directly target cardiac aging into cardiovascular clinical trials.

Author contributions

ZW: Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. ZL: Supervision, Writing – original draft. NQ: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Acknowledgements

Figures were created with BioRender.com. The authors thank Liwen Bianji (Edanz) (www.liwenbianji.cn) for editing the English text of a draft of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcell.2025.1702207/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

AF, atrial fibrillation; AMPK, adenosine 5′-monophosphate activated protein kinase; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; CaMKIIδ, calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II delta; CDK, cyclin-dependent kinase; ERK1/2, extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2; FOXOs, fork-head box O transcription factors; IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor 1; IL, interleukin; JAK/STAT, Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; MMP-2, matrix metalloproteinase-2; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; NAD, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; NCX, sodium-calcium exchanger; NF-κB, nuclear factor-kappa B; NLRP3, NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3; NOD, nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain; PAI-1, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1; PARP-1, poly ADP-ribose polymerase-1; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase; ROS, reactive oxygen species; RyR2, ryanodine receptor 2; SASP, senescence-associated secretory phenotype; SERCA2, sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2; SIRT1, sirtuin 1; SMAD, small mothers against decapentaplegic; TGF-β, transforming growth factor beta; TLR4-MD2, toll-like receptor 4 co-receptor myeloid differentiation protein 2.

References

Acosta, J. C., Banito, A., Wuestefeld, T., Georgilis, A., Janich, P., Morton, J. P., et al. (2013). A complex secretory program orchestrated by the inflammasome controls paracrine senescence. Nat. Cell Biol. 15, 978–990. doi:10.1038/ncb2784

Adili, A., Zhu, X., Cao, H., Tang, X., Wang, Y., Wang, J., et al. (2022). Atrial fibrillation underlies cardiomyocyte senescence and contributes to deleterious atrial remodeling during disease progression. Aging Dis. 13, 298–312. doi:10.14336/AD.2021.0619

Ajoolabady, A., Nattel, S., Lip, G. Y. H., and Ren, J. (2022). Inflammasome signaling in atrial fibrillation: JACC state-of-the-art review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 79, 2349–2366. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2022.03.379

Al-Hasani, K., Khurana, I., Mariana, L., Loudovaris, T., Maxwell, S., Harikrishnan, K. N., et al. (2022). Inhibition of pancreatic EZH2 restores progenitor insulin in T1D donor. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 7, 248. doi:10.1038/s41392-022-01034-7

Alcorta, D. A., Xiong, Y., Phelps, D., Hannon, G., Beach, D., and Barrett, J. C. (1996). Involvement of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p16 (INK4a) in replicative senescence of normal human fibroblasts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93, 13742–13747. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.24.13742

Allessie, M. A., De Groot, N. M., Houben, R. P., Schotten, U., Boersma, E., Smeets, J. L., et al. (2010). Electropathological substrate of long-standing persistent atrial fibrillation in patients with structural heart disease: longitudinal dissociation. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 3, 606–615. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.109.910125

Almeida, M., and Porter, R. M. (2019). Sirtuins and FoxOs in osteoporosis and osteoarthritis. Bone 121, 284–292. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2019.01.018

Anderson, R., Lagnado, A., Maggiorani, D., Walaszczyk, A., Dookun, E., Chapman, J., et al. (2019). Length-independent telomere damage drives post-mitotic cardiomyocyte senescence. EMBO J. 38, e100492. doi:10.15252/embj.2018100492

Andrade, J., Khairy, P., Dobrev, D., and Nattel, S. (2014). The clinical profile and pathophysiology of atrial fibrillation: relationships among clinical features, epidemiology, and mechanisms. Circ. Res. 114, 1453–1468. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.303211

Arriola Apelo, S. I., Neuman, J. C., Baar, E. L., Syed, F. A., Cummings, N. E., Brar, H. K., et al. (2016a). Alternative rapamycin treatment regimens mitigate the impact of rapamycin on glucose homeostasis and the immune system. Aging Cell 15, 28–38. doi:10.1111/acel.12405

Arriola Apelo, S. I., Pumper, C. P., Baar, E. L., Cummings, N. E., and Lamming, D. W. (2016b). Intermittent administration of rapamycin extends the life span of female C57BL/6J mice. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 71, 876–881. doi:10.1093/gerona/glw064

Balch, W. E., Morimoto, R. I., Dillin, A., and Kelly, J. W. (2008). Adapting proteostasis for disease intervention. Science. 319, 916–919. doi:10.1126/science.1141448

Bandeen-Roche, K., Xue, Q. L., Ferrucci, L., Walston, J., Guralnik, J. M., Chaves, P., et al. (2006). Phenotype of frailty: characterization in the women's health and aging studies. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 61, 262–266. doi:10.1093/gerona/61.3.262

Bazarov, A. V., Lee, W. J., Bazarov, I., Bosire, M., Hines, W. C., Stankovich, B., et al. (2012). The specific role of pRb in p16 (INK4A) -mediated arrest of normal and malignant human breast cells. Cell Cycle. 11, 1008–1013. doi:10.4161/cc.11.5.19492

Bers, D. M. (2014). Cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium leak: basis and roles in cardiac dysfunction. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 76, 107–127. doi:10.1146/annurev-physiol-020911-153308

Birch, J., and Gil, J. (2020). Senescence and the SASP: many therapeutic avenues. Genes. Dev. 34, 1565–1576. doi:10.1101/gad.343129.120

Bitto, A., Ito, T. K., Pineda, V. V., Letexier, N. J., Huang, H. Z., Sutlief, E., et al. (2016). Transient rapamycin treatment can increase lifespan and healthspan in middle-aged mice. Elife. 5, e16351. doi:10.7554/eLife.16351

Bjedov, I., Toivonen, J. M., Kerr, F., Slack, C., Jacobson, J., Foley, A., et al. (2010). Mechanisms of life span extension by rapamycin in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster. Cell Metab. 11, 35–46. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2009.11.010

Brown, E. J., Albers, M. W., Shin, T. B., Ichikawa, K., Keith, C. T., Lane, W. S., et al. (1994). A mammalian protein targeted by G1-arresting rapamycin-receptor complex. Nature. 369, 756–758. doi:10.1038/369756a0

Brundel, B. J., Henning, R. H., Ke, L., Van Gelder, I. C., Crijns, H. J., and Kampinga, H. H. (2006a). Heat shock protein upregulation protects against pacing-induced myolysis in HL-1 atrial myocytes and in human atrial fibrillation. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 41, 555–562. doi:10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.06.068

Brundel, B. J., Shiroshita-Takeshita, A., Qi, X., Yeh, Y. H., Chartier, D., Van Gelder, I. C., et al. (2006b). Induction of heat shock response protects the heart against atrial fibrillation. Circ. Res. 99, 1394–1402. doi:10.1161/01.RES.0000252323.83137.fe

Brundel, B. J., Ke, L., Dijkhuis, A. J., Qi, X., Shiroshita-Takeshita, A., Nattel, S., et al. (2008). Heat shock proteins as molecular targets for intervention in atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res. 78, 422–428. doi:10.1093/cvr/cvn060

Brundel, B., Ai, X., Hills, M. T., Kuipers, M. F., Lip, G. Y. H., and De Groot, N. M. S. (2022). Atrial fibrillation. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 8, 21. doi:10.1038/s41572-022-00347-9

Bugyei-Twum, A., Ford, C., Civitarese, R., Seegobin, J., Advani, S. L., Desjardins, J. F., et al. (2018). Sirtuin 1 activation attenuates cardiac fibrosis in a rodent pressure overload model by modifying Smad2/3 transactivation. Cardiovasc Res. 114, 1629–1641. doi:10.1093/cvr/cvy131

Burd, C. E., Sorrentino, J. A., Clark, K. S., Darr, D. B., Krishnamurthy, J., Deal, A. M., et al. (2013). Monitoring tumorigenesis and senescence in vivo with a p16(INK4a)-luciferase model. Cell. 152, 340–351. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.010

Calvanese, V., Lara, E., Kahn, A., and Fraga, M. F. (2009). The role of epigenetics in aging and age-related diseases. Ageing Res. Rev. 8, 268–276. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2009.03.004

Cammarano, M. S., Nekrasova, T., Noel, B., and Minden, A. (2005). Pak4 induces premature senescence via a pathway requiring p16INK4/p19ARF and mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling. Mol. Cell Biol. 25, 9532–9542. doi:10.1128/MCB.25.21.9532-9542.2005

Campaner, S., Doni, M., Verrecchia, A., Faga, G., Bianchi, L., and Amati, B. (2010). Myc, Cdk2 and cellular senescence: old players, new game. Cell Cycle. 9, 3655–3661. doi:10.4161/cc.9.18.13049

Campbell, H. M., Quick, A. P., Abu-Taha, I., Chiang, D. Y., Kramm, C. F., Word, T. A., et al. (2020). Loss of SPEG inhibitory phosphorylation of ryanodine receptor Type-2 promotes atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 142, 1159–1172. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.045791

Campisi, J., Kapahi, P., Lithgow, G. J., Melov, S., Newman, J. C., and Verdin, E. (2019). From discoveries in ageing research to therapeutics for healthy ageing. Nature. 571, 183–192. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1365-2

Catanzaro, J. M., Sheshadri, N., Pan, J. A., Sun, Y., Shi, C., Li, J., et al. (2014). Oncogenic ras induces inflammatory cytokine production by upregulating the squamous cell carcinoma antigens SerpinB3/B4. Nat. Commun. 5, 3729. doi:10.1038/ncomms4729

Chaldoupi, S. M., Loh, P., Hauer, R. N., De Bakker, J. M., and Van Rijen, H. V. (2009). The role of connexin40 in atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res. 84, 15–23. doi:10.1093/cvr/cvp203

Chapman, J., Fielder, E., and Passos, J. F. (2019). Mitochondrial dysfunction and cell senescence: deciphering a complex relationship. FEBS Lett. 593, 1566–1579. doi:10.1002/1873-3468.13498

Chelu, M. G., Sarma, S., Sood, S., Wang, S., Van Oort, R. J., Skapura, D. G., et al. (2009). Calmodulin kinase II-mediated sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ leak promotes atrial fibrillation in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 119, 1940–1951. doi:10.1172/jci37059

Chen, S. A., Hsieh, M. H., Tai, C. T., Tsai, C. F., Prakash, V. S., Yu, W. C., et al. (1999). Initiation of atrial fibrillation by ectopic beats originating from the pulmonary veins: electrophysiological characteristics, pharmacological responses, and effects of radiofrequency ablation. Circulation. 100, 1879–1886. doi:10.1161/01.cir.100.18.1879

Chen, P. M., Lin, C. H., Li, N. T., Wu, Y. M., Lin, M. T., Hung, S. C., et al. (2015). c-Maf regulates pluripotency genes, proliferation/self-renewal, and lineage commitment in ROS-mediated senescence of human mesenchymal stem cells. Oncotarget. 6, 35404–35418. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.6178

Chen, C., Zhou, M., Ge, Y., and Wang, X. (2020). SIRT1 and aging related signaling pathways. Mech. Ageing Dev. 187, 111215. doi:10.1016/j.mad.2020.111215

Chen, J., Chen, H., and Pan, L. (2021a). SIRT1 and gynecological malignancies (Review). Oncol. Rep. 45, 43. doi:10.3892/or.2021.7994

Chen, Y. C., Voskoboinik, A., Gerche, A. L., Marwick, T. H., and Mcmullen, J. R. (2021b). Prevention of pathological atrial remodeling and atrial fibrillation: JACC state-of-the-art review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 77, 2846–2864. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2021.04.012

Chen, Y. C., Wijekoon, S., Matsumoto, A., Luo, J., Kiriazis, H., Masterman, E., et al. (2024). Distinct functional and molecular profiles between physiological and pathological atrial enlargement offer potential new therapeutic opportunities for atrial fibrillation. Clin. Sci. (Lond). 138, 941–962. doi:10.1042/CS20240178

Chiang, D. Y., Kongchan, N., Beavers, D. L., Alsina, K. M., Voigt, N., Neilson, J. R., et al. (2014). Loss of microRNA-106b-25 cluster promotes atrial fibrillation by enhancing ryanodine receptor type-2 expression and calcium release. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 7, 1214–1222. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.114.001973

Chiang, D. Y., Zhang, M., Voigt, N., Alsina, K. M., Jakob, H., Martin, J. F., et al. (2015). Identification of microRNA-mRNA dysregulations in paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Int. J. Cardiol. 184, 190–197. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.01.075

Choi, E. K., Chang, P. C., Lee, Y. S., Lin, S. F., Zhu, W., Maruyama, M., et al. (2012). Triggered firing and atrial fibrillation in transgenic mice with selective atrial fibrosis induced by overexpression of TGF-beta1. Circ. J. 76, 1354–1362. doi:10.1253/circj.cj-11-1301

Christ, T., Boknik, P., Wohrl, S., Wettwer, E., Graf, E. M., Bosch, R. F., et al. (2004). L-type Ca2+ current downregulation in chronic human atrial fibrillation is associated with increased activity of protein phosphatases. Circulation. 110, 2651–2657. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000145659.80212.6A

Coppe, J. P., Patil, C. K., Rodier, F., Sun, Y., Munoz, D. P., Goldstein, J., et al. (2008). Senescence-associated secretory phenotypes reveal cell-nonautonomous functions of oncogenic RAS and the p53 tumor suppressor. PLoS Biol. 6, 2853–2868. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0060301

Coppe, J. P., Desprez, P. Y., Krtolica, A., and Campisi, J. (2010). The senescence-associated secretory phenotype: the dark side of tumor suppression. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 5, 99–118. doi:10.1146/annurev-pathol-121808-102144

Cordero, M. D., Williams, M. R., and Ryffel, B. (2018). AMP-activated protein kinase regulation of the NLRP3 inflammasome during aging. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 29, 8–17. doi:10.1016/j.tem.2017.10.009

Dalton, G. D., Xie, J., An, S. W., and Huang, C. L. (2017). New insights into the mechanism of action of soluble klotho. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 8, 323. doi:10.3389/fendo.2017.00323

Davis, R. J. (2000). Signal transduction by the JNK group of MAP kinases. Cell. 103, 239–252. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00116-1

Day, K., Waite, L. L., Thalacker-Mercer, A., West, A., Bamman, M. M., Brooks, J. D., et al. (2013). Differential DNA methylation with age displays both common and dynamic features across human tissues that are influenced by CpG landscape. Genome Biol. 14, R102. doi:10.1186/gb-2013-14-9-r102

De Mendoza, A., Nguyen, T. V., Ford, E., Poppe, D., Buckberry, S., Pflueger, J., et al. (2022). Large-scale manipulation of promoter DNA methylation reveals context-specific transcriptional responses and stability. Genome Biol. 23, 163. doi:10.1186/s13059-022-02728-5

Demaria, M., Ohtani, N., Youssef, S. A., Rodier, F., Toussaint, W., Mitchell, J. R., et al. (2014). An essential role for senescent cells in optimal wound healing through secretion of PDGF-AA. Dev. Cell. 31, 722–733. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2014.11.012

Desplantez, T. (2017). Cardiac Cx43, Cx40 and Cx45 co-assembling: involvement of connexins epitopes in formation of hemichannels and gap junction channels. BMC Cell Biol. 18, 3. doi:10.1186/s12860-016-0118-4

Ding, M., Feng, N., Tang, D., Feng, J., Li, Z., Jia, M., et al. (2018). Melatonin prevents Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fission in diabetic hearts through SIRT1-PGC1alpha pathway. J. Pineal Res. 65, e12491. doi:10.1111/jpi.12491

Dogterom, M., and Koenderink, G. H. (2019). Actin-microtubule crosstalk in cell biology. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 20, 38–54. doi:10.1038/s41580-018-0067-1

Donate Puertas, R., Meugnier, E., Romestaing, C., Rey, C., Morel, E., Lachuer, J., et al. (2017). Atrial fibrillation is associated with hypermethylation in human left atrium, and treatment with decitabine reduces atrial tachyarrhythmias in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Transl. Res. 184, 57–67 e5. doi:10.1016/j.trsl.2017.03.004

Dridi, H., Kushnir, A., Zalk, R., Yuan, Q., Melville, Z., and Marks, A. R. (2020). Intracellular calcium leak in heart failure and atrial fibrillation: a unifying mechanism and therapeutic target. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 17, 732–747. doi:10.1038/s41569-020-0394-8

Dulic, V., Kaufmann, W. K., Wilson, S. J., Tlsty, T. D., Lees, E., Harper, J. W., et al. (1994). p53-dependent inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinase activities in human fibroblasts during radiation-induced G1 arrest. Cell. 76, 1013–1023. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(94)90379-4

Ebana, Y., Sun, Y., Yang, X., Watanabe, T., Makita, S., Ozaki, K., et al. (2019). Pathway analysis with genome-wide association study (GWAS) data detected the association of atrial fibrillation with the mTOR signaling pathway. Int. J. Cardiol. Heart Vasc. 24, 100383. doi:10.1016/j.ijcha.2019.100383

Eggert, T., Wolter, K., Ji, J., Ma, C., Yevsa, T., Klotz, S., et al. (2016). Distinct functions of senescence-associated immune responses in liver tumor surveillance and tumor progression. Cancer Cell. 30, 533–547. doi:10.1016/j.ccell.2016.09.003

El-Deiry, W. S., Tokino, T., Velculescu, V. E., Levy, D. B., Parsons, R., Trent, J. M., et al. (1993). WAF1, a potential mediator of p53 tumor suppression. Cell. 75, 817–825. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(93)90500-p

Faget, D. V., Ren, Q., and Stewart, S. A. (2019). Unmasking senescence: context-dependent effects of SASP in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 19, 439–453. doi:10.1038/s41568-019-0156-2

Fakuade, F. E., Tomsits, P., and Voigt, N. (2021). Connexin hemichannels in atrial fibrillation: orphaned and irrelevant? Cardiovasc Res. 117, 4–6. doi:10.1093/cvr/cvaa308

Fan, C., Ji, Q., Zhang, C., Xu, S., Sun, H., and Li, Z. (2019). TGF-beta induces periodontal ligament stem cell senescence through increase of ROS production. Mol. Med. Rep. 20, 3123–3130. doi:10.3892/mmr.2019.10580

Feng, D., Xu, D., Murakoshi, N., Tajiri, K., Qin, R., Yonebayashi, S., et al. (2020). Nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (Nampt)/Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) axis suppresses atrial fibrillation by modulating the calcium handling pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 4655. doi:10.3390/ijms21134655

Ferrucci, L., and Fabbri, E. (2018). Inflammageing: chronic inflammation in ageing, cardiovascular disease, and frailty. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 15, 505–522. doi:10.1038/s41569-018-0064-2

Franceschi, C., Bonafe, M., Valensin, S., Olivieri, F., De Luca, M., Ottaviani, E., et al. (2000). Inflamm-aging. An evolutionary perspective on immunosenescence. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 908, 244–254. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06651.x

Freund, A., Patil, C. K., and Campisi, J. (2011). p38MAPK is a novel DNA damage response-independent regulator of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype. EMBO J. 30, 1536–1548. doi:10.1038/emboj.2011.69

Gasek, N. S., Kuchel, G. A., Kirkland, J. L., and Xu, M. (2021). Strategies for targeting senescent cells in human disease. Nat. Aging. 1, 870–879. doi:10.1038/s43587-021-00121-8

Gluck, S., Guey, B., Gulen, M. F., Wolter, K., Kang, T. W., Schmacke, N. A., et al. (2017). Innate immune sensing of cytosolic chromatin fragments through cGAS promotes senescence. Nat. Cell Biol. 19, 1061–1070. doi:10.1038/ncb3586

Gollob, M. H., Jones, D. L., Krahn, A. D., Danis, L., Gong, X. Q., Shao, Q., et al. (2006). Somatic mutations in the connexin 40 gene (GJA5) in atrial fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 354, 2677–2688. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa052800

Gorgoulis, V., Adams, P. D., Alimonti, A., Bennett, D. C., Bischof, O., Bishop, C., et al. (2019). Cellular senescence: defining a path forward. Cell. 179, 813–827. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2019.10.005

Gray-Schopfer, V. C., Cheong, S. C., Chong, H., Chow, J., Moss, T., Abdel-Malek, Z. A., et al. (2006). Cellular senescence in naevi and immortalisation in melanoma: a role for p16? Br. J. Cancer. 95, 496–505. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6603283

Griveau, A., Wiel, C., Ziegler, D. V., Bergo, M. O., and Bernard, D. (2020). The JAK1/2 inhibitor ruxolitinib delays premature aging phenotypes. Aging Cell. 19, e13122. doi:10.1111/acel.13122

Hahn, A., and Zuryn, S. (2019). Mitochondrial genome (mtDNA) mutations that generate reactive oxygen species. Antioxidants (Basel). 8, 392. doi:10.3390/antiox8090392

Haigis, M. C., and Sinclair, D. A. (2010). Mammalian sirtuins: biological insights and disease relevance. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 5, 253–295. doi:10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092250

Haissaguerre, M., Jais, P., Shah, D. C., Takahashi, A., Hocini, M., Quiniou, G., et al. (1998). Spontaneous initiation of atrial fibrillation by ectopic beats originating in the pulmonary veins. N. Engl. J. Med. 339, 659–666. doi:10.1056/NEJM199809033391003

Han, L., Tang, Y., Li, S., Wu, Y., Chen, X., Wu, Q., et al. (2020a). Protective mechanism of SIRT1 on Hcy-induced atrial fibrosis mediated by TRPC3. J. Cell Mol. Med. 24, 488–510. doi:10.1111/jcmm.14757

Han, Y., Sun, W., Ren, D., Zhang, J., He, Z., Fedorova, J., et al. (2020b). SIRT1 agonism modulates cardiac NLRP3 inflammasome through pyruvate dehydrogenase during ischemia and reperfusion. Redox Biol. 34, 101538. doi:10.1016/j.redox.2020.101538

Hannum, G., Guinney, J., Zhao, L., Zhang, L., Hughes, G., Sadda, S., et al. (2013). Genome-wide methylation profiles reveal quantitative views of human aging rates. Mol. Cell. 49, 359–367. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.016

Hansen, M., Rubinsztein, D. C., and Walker, D. W. (2018). Autophagy as a promoter of longevity: insights from model organisms. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 579–593. doi:10.1038/s41580-018-0033-y

Hasan, H., Park, S. H., Auger, C., Belcastro, E., Matsushita, K., Marchandot, B., et al. (2019). Thrombin induces angiotensin II-Mediated senescence in atrial endothelial cells: impact on pro-remodeling patterns. J. Clin. Med. 8, 1570. doi:10.3390/jcm8101570

Haupt, Y., Maya, R., Kazaz, A., and Oren, M. (1997). Mdm2 promotes the rapid degradation of p53. Nature. 387, 296–299. doi:10.1038/387296a0