Abstract

Historically, Campylobacteriosis has been considered to be zoonotic; the Campylobacter species that cause human acute intestinal disease such as Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli originate from animals. Over the past decade, studies on human hosted Campylobacter species strongly suggest that Campylobacter concisus plays a role in the development of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). C. concisus primarily colonizes the human oral cavity and some strains can be translocated to the intestinal tract. Genome analysis of C. concisus strains isolated from saliva samples has identified a bacterial marker that is associated with active Crohn's disease (one major form of IBD). In addition to C. concisus, humans are also colonized by a number of other Campylobacter species, most of which are in the oral cavity. Here we review the most recent advancements on C. concisus and other human hosted Campylobacter species including their clinical relevance, transmission, virulence factors, disease associated genes, interactions with the human immune system and pathogenic mechanisms.

Introduction

Campylobacter, along with Arcobacter and Sulfurospirillum, are the three genera that belong to the family, Campylobacteraceae. Campylobacter species are Gram-negative, curved or spiral shaped, and most of them are motile with a single polar flagellum present at one or both ends of the bacteria, allowing them to have a corkscrew-like motion during movement (Lastovica et al., 2014). Campylobacter species have low G + C content in their genome, and the median G + C content for most of the Campylobacter species ranges from 28 to 40% (Pruitt et al., 2007). There are few Campylobacter species which have G + C content of more than 40% in their genomes, including Campylobacter curvus, Campylobacter rectus, Campylobacter showae and Campylobacter gracilis (Pruitt et al., 2007). A majority of the Campylobacter species are microaerophiles, while some require anaerobic conditions for their growth (Debruyne et al., 2008).

Most Campylobacter species live as normal flora in the gastrointestinal tract of various animals (Lastovica et al., 2014). Some of these animal hosted Campylobacter species, such as Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli, can cause acute bacterial gastroenteritis in humans through consumption of contaminated food or water (Galanis, 2007). In addition to gastroenteritis, C. jejuni also causes Guillain-Barré syndrome, due to molecular mimicry between its sialylated lipooligosaccharides and the human nerve gangliosides (Takahashi et al., 2005).

As C. jejuni and C. coli are the main Campylobacter pathogens which cause human acute intestinal disease and they originate from animal sources, Campylobacteriosis has historically been considered to be zoonotic. Several Campylobacter species utilize humans as their natural host and accumulated evidence supports their role in chronic inflammatory diseases of the human intestinal tract. Here we review recent advancements on human hosted Campylobacter species, their clinical relevance, transmission, virulence factors, disease associated genes, interactions with human immune system and pathogenic mechanisms. Most of the studies on the human hosted Campylobacter species in the past decade were on Campylobacter concisus, this bacterium is therefore the focus of this review. In addition, other human hosted Campylobacter species were also reviewed.

The natural hosts of Campylobacter species and human diseases associated with Campylobacter species

The natural host of a bacterium refers to the host that the bacterium normally lives and reproduces (Haydon et al., 2002; Control and Prevention, 2006). Bacterial species are usually not harmful to their hosts, although there are exceptions. For example, Helicobacter pylori is a human hosted bacterial species, causing gastritis and gastric ulcers and being a risk factor for gastric cancer (Roesler et al., 2014).

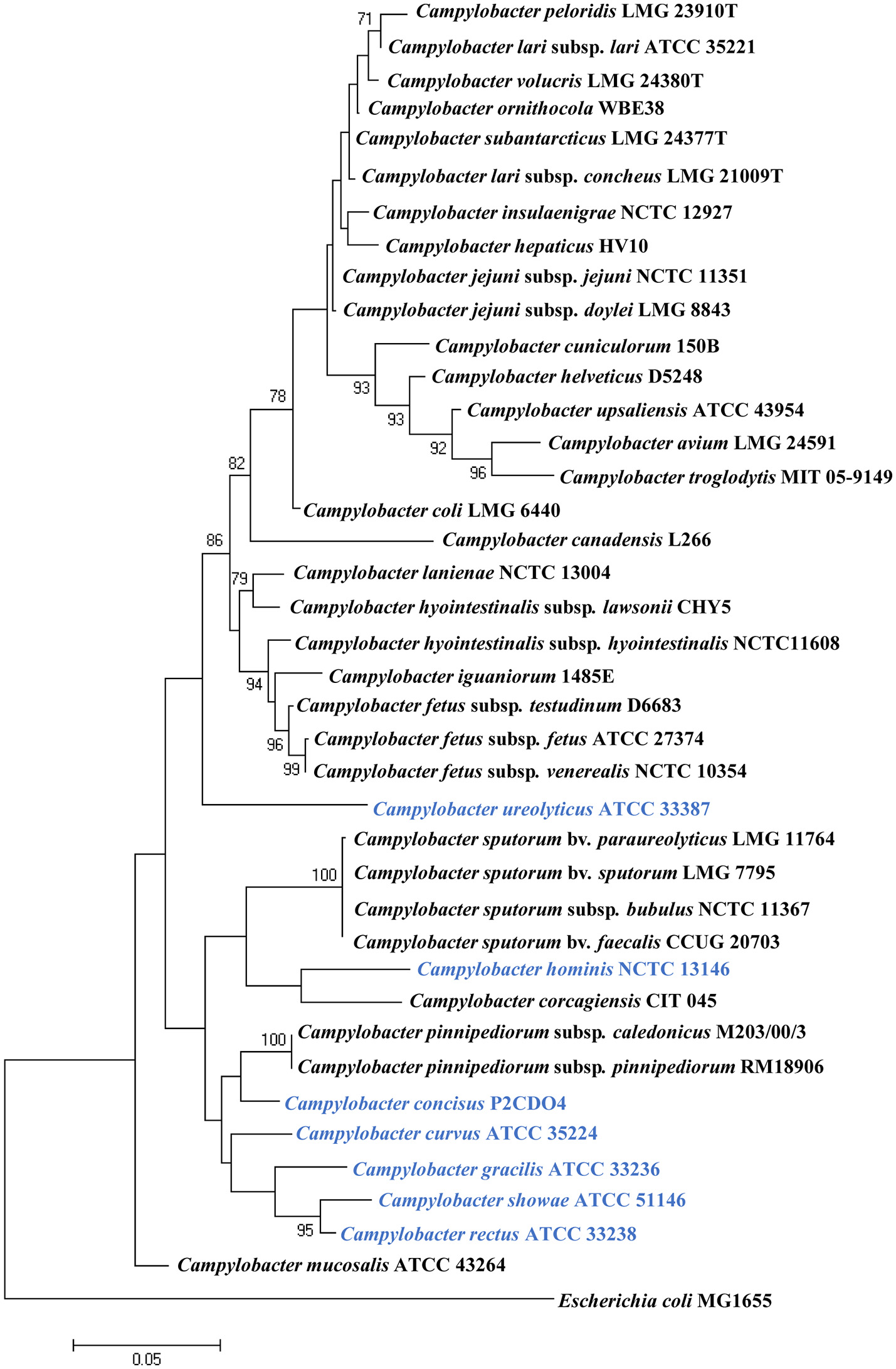

To date, 40 Campylobacter species and subspecies have been isolated from a wide variety of animal or human sources (Figure 1). Many Campylobacter species are naturally hosted by domesticated animals raised as food such as chicken, cattle and pigs (Lastovica et al., 2014). They survive as commensal bacteria in their hosts, and some species, such as C. jejuni and C. coli, can cause human diseases. The main human disease caused by animal hosted pathogenic Campylobacter species is acute gastroenteritis and clinical disorders can also arise if bacterial species colonizing sterile sites of the body (Table 1). A number of Campylobacter species are also able to cause diseases in animals. For example, Campylobacter fetus is known to cause abortion in bovine and ovine, and Campylobacter hepaticus is the causative agent of spotty liver disease in chicken (Campero et al., 2005; Van et al., 2016).

Figure 1

Phylogenetic tree based on the 16S rRNA gene of Campylobcter species. The tree was generated using the maximum likelihood method implemented in MEGA7. Bootstrap values were generated from 1000 replicates. Bootstrap values of more than 70 were indicated. Escherichia coli MG1655 was included as an outgroup. Human hosted Campylobacter species are in blue. Campylobacter geochelonis was not included because its 16S rRNA sequence was not available.

Table 1

| Campylobacter species | Isolation sources | Clinical relevance of human diseases | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Campylobacter coli | Gastroenteritis: feces Bacteraemia: blood Septic abortion: blood; maternal placenta; amniotic fluid Acute cholecystitis: gallbladder Retroperitoneal abscess Meningitis: CSF |

Gastroenteritis* Abortion* Bacteraemia* |

Skirrow, 1977; Kist et al., 1984; Blaser et al., 1986; Møller Nielsen et al., 1997; Lastovica and Roux, 2000; Galanis, 2007; Liu Y. H. et al., 2017; |

| Campylobacter fetus subsp. fetus | Bacteraemia: blood Gastroenteritis: feces Meningitis: feces; blood; CSF Chorioamnionitis: blood Cellulitis lesion: subcutaneous aspirate Cellulitis and bacteraemia: blood; feces Abortion: vagina; feces; blood; gastric aspirate; skin; liver; spleen; lung; spinal fluid Postsurgical abscess: groin abscess Post abortion infection: amniotic fluid Hemiparesis and aphasia: blood Cystic fibrosis: feces Surgical fever: blood Fever, chills, endocarditis: blood Immune deficiency disease: blood Sepsis, encephalitis, fever, myalgia: blood and CSF Cellulitis and diarrhea: ankle abscess Post-neurosurgery for metastatic esophagocardial carcinoma: brain abscess Chronic alcoholism: brain abscess Prematurity: brain abscess Heroin and barbiturate abuse: pulmonary abscess Alcoholism: gluteal abscess; blood Post-hemilaminectomy for disc herniation: epidural mass in pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis Hyperthyroidism: thyroid gland abscess |

Bacteraemia* Abortion* Meningitis* Abscess* Gastroenteritis |

Blaser et al., 1980a,b; Edmonds et al., 1985; Francioli et al., 1985; La Scolea, 1985; Klein et al., 1986; Simor et al., 1986; Morrison et al., 1990; Sauerwein et al., 1993; Kwon et al., 1994; Neuzil et al., 1994; Steinkraus and Wright, 1994; Morooka et al., 1996; Ichiyama et al., 1998; Lastovica and Roux, 2000; Viejo et al., 2001; Krause et al., 2002; Fujihara et al., 2006; De Vries et al., 2008; Liu Y. H. et al., 2017 |

| Health status unknown: Blood and synovial fluid | |||

| Campylobacter fetus subsp. testudinum | Leukemia: blood Liver cancer (bloody diarrhea, pulmonary edema): pleural fluid Asthma: hematoma Lymphoma, hypertension, and heart disease (fever, chills, rigor, cough, and diarrhea): blood Diarrhea: bile Diabetes (cellulitis of leg): blood |

Leukemia* | Tu et al., 2004; Patrick et al., 2013 |

| Campylobacter fetus subsp. venerealis | Bacteraemia: blood Infective aneurysm: blood Vaginosis |

Garcia et al., 1995; Tu et al., 2001; Hagiya et al., 2015; Liu Y. H. et al., 2017 | |

| Health status unknown: blood | |||

| Campylobacter helveticus | Health status unknown: feces | Lawson et al., 1997 | |

| Campylobacter hyointestinalis (subsp. hyointestinalis and lawsonii) | Proctitis: rectum Gastroenteritis: feces |

Gastroenteritis* | Fennell et al., 1986; Edmonds et al., 1987; Lastovica and Roux, 2000; Gorkiewicz et al., 2002 |

| Campylobacter insulaenigrae | Gastroenteritis: blood Bacteraemia: blood |

Gastroenteritis Bacteraemia* |

Chua et al., 2007 |

| Campylobacter jejuni (subsp. jejuni and doylei) | Bacteraemia: blood; feces Gastroenteritis: feces Sepsis: blood, feces, placenta Meningitis: CSF Appendicitis: appendix Myocarditis: feces Reactive arthritis: feces Guillain-Barré syndrome: feces Fisher syndromes: feces; gastric biopsy; CSF Recurrent colitis: blood; feces Acute cholecystitis: gallbladder Urinary tract infection: urine Chronic renal failure: peritoneal prodialysis fluid Ovarian cyst: peritoneal cyst fluid Thoracic wall abscess: thoracic wall Meningitis and hypogammaglobulinemia: CSF |

Gastroenteritis* Bacteraemia* Guillain-Barré syndrome* Meningitis* Appendicitis Myocarditis Reactive arthritis |

Skirrow, 1977; Thomas et al., 1980; Gilbert et al., 1981; Megraud et al., 1982; Chan et al., 1983; Blaser et al., 1986; Dhawan et al., 1986; Goossens et al., 1986; Klein et al., 1986; Kohler et al., 1988; Korman et al., 1997; Meyer et al., 1997; Møller Nielsen et al., 1997; Manfredi et al., 1999; Lastovica and Roux, 2000; Wolfs et al., 2001; Hannu et al., 2002, 2004; Cunningham and Lee, 2003; Takahashi et al., 2005; Lastovica, 2006; Galanis, 2007; Pena and Fishbein, 2007; Mortensen et al., 2009; Liu Y. H. et al., 2017 |

| Campylobacter lanienae | Healthy: feces | Logan et al., 2000 | |

| Campylobacter lari (subsp. concheus and lari) | Urinary tract infection: urine Bacteraemia: blood Gastroenteritis: feces |

Bacteraemia* | Bézian et al., 1990; Morris et al., 1998; Lastovica and Roux, 2000; Martinot et al., 2001; Krause et al., 2002; Werno et al., 2002 |

| Campylobacter mucosalis | Gastroenteritis: feces | Figura et al., 1993 | |

| Campylobacter peloridis | Health status unknown: feces | Debruyne et al., 2009 | |

| Campylobacter sputorum (biovar faecalis, paraureolyticus, sputorum, and bubulus) | Gastroenteritis: feces Axillary abscess Leg abscess Pus from pressure sore |

Gastroenteritis Abscess* |

Roop Ii et al., 1985; Steele et al., 1985; Lindblom et al., 1995; Tee et al., 1998; De Vries et al., 2008 |

| Health status unknown: oral cavity; feces | |||

| Campylobacter troglodytis | Gastroenteritis: feces | Platts-Mills et al., 2014 | |

| Campylobacter upsaliensis | Abortion: blood and fetoplacental material Bacteraemia: blood Gastroenteritis: feces Breast abscess |

Gastroenteritis Bacteraemia* |

Lastovica et al., 1989; Gurgan and Diker, 1994; Jimenez et al., 1999; Lastovica and Roux, 2000; Lastovica and Le Roux, 2001; De Vries et al., 2008 |

Clinical relevance of animal hosted Campylobacter species.

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

Campylobacter species that have established associations with human diseases or have been isolated from a sterile site. Species which have not yet been isolated from humans were not included.

Campylobacter species hosted by humans include C. concisus, C. curvus, C. gracilis, Campylobacter hominis, C. rectus, and C. showae; to date these six Campylobacter species have only been isolated from humans (Hariharan et al., 1994; Zhang, 2015). Campylobacter ureolyticus was isolated from human samples in most cases, with only one study isolating C. ureolyticus from the endometria of healthy horses (Hariharan et al., 1994). Therefore, in this review, C. ureolyticus is considered as a human hosted Campylobacter species. In contrast to animal hosted Campylobacter pathogens, the human hosted Campylobacter pathogens are more often involved in chronic inflammatory conditions of the gastrointestinal tract (Table 2).

Table 2

| Campylobacter species | Isolation sites in human | Clinical relevance of human diseases | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Campylobacter concisus | Healthy: saliva; subgingival site; intestinal biopsy; feces | Inflammatory bowel disease* Diarrheal diseases Barrett's esophagus* Periodontal disease |

Tanner et al., 1981; Lindblom et al., 1995; Lastovica and Roux, 2000; Macuch and Tanner, 2000; Lastovica, 2006; Macfarlane et al., 2007; De Vries et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2010; Kalischuk and Inglis, 2011; Mukhopadhya et al., 2011; Nielsen et al., 2011, 2013; Blackett et al., 2013; Mahendran et al., 2013; Zhang, 2015; Kirk et al., 2016 |

| IBD: saliva; intestinal biopsy Diarrhea: feces Barrett's esophagus: esophageal aspirate; distal esophageal biopsy Brain abscess: secondary to chronic frontal osteomyelitis Periodontal disease: subgingival site |

|||

| Campylobacter curvus | Healthy: subgingival site | Gastroenteritis Abscess |

Koga et al., 1999; Lastovica and Roux, 2000; Macuch and Tanner, 2000; Abbott et al., 2005; Petersen et al., 2007; De Vries et al., 2008; Mendz et al., 2014; Horio et al., 2017 |

| Periodontal disease: subgingival and periodontitis site Thoracic empyema: pleural effusion Premature birth: vaginal swabs Alveolar abscess Metastatic ovarian cancer: liver abscess Liver abscess: blood Lung cancer: bronchial abscess Guillain-Barré syndrome: feces Fisher's syndrome: feces Gastroenteritis: feces |

|||

| Campylobacter gracilis | Healthy: subgingival site | Periodontal disease* | Tanner et al., 1981; Johnson et al., 1985; Yu and Chen, 1997; Macuch and Tanner, 2000; De Vries et al., 2008; Shinha, 2015 |

| Bacteraemia: blood Brain abscess (post-partum) Tubo-ovarian abscess Periodontal disease: subgingival and periodontitis site Visceral or head and neck infection |

|||

| Campylobacter hominis | Healthy: feces | Septicaemia | Lawson et al., 1998, 2001; Linscott et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2009 |

| Septicaemia: blood CD: intestinal biopsy |

|||

| Campylobacter rectus | Healthy: subgingival site | Periodontal diseases* IBD |

Von Troil-Lindén et al., 1995; Lastovica and Roux, 2000; Macuch and Tanner, 2000; Han et al., 2005; Macfarlane et al., 2007; De Vries et al., 2008; Mahlen and Clarridge, 2009; Zhang et al., 2009; Man et al., 2010b; López et al., 2011; Mukhopadhya et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2012; Leo and Bolger, 2014; Noël et al., 2018 |

| Periodontal disease: subgingival and periodontitis site Barrett's esophagus: distal esophageal mucosal biopsy Fatal thoracic empyema: pleural liquid Septic cavernous sinus thrombosis: blood Gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma: palate abscess Breast abscess Vertebral abscess Gastroenteritis: feces |

|||

| Campylobacter showae | Healthy: subgingival site; gingival crevices | IBD | Etoh et al., 1993; Macuch and Tanner, 2000; De Vries et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2009; Man et al., 2010b; Suzuki et al., 2013 |

| Periodontal disease: subgingival and periodontitis site CD: intestinal biopsy Intraorbital abscess Bacteraemia: blood |

|||

| Campylobacter ureolyticus | Healthy: Male: urine Female: genital tract |

IBD Gastroenteritis Genital tract diseae |

Duerden et al., 1982, 1987, 1989; Johnson et al., 1985; Bennett et al., 1990, 1991; Petersen et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2009; Bullman et al., 2011; Mukhopadhya et al., 2011; O'doherty et al., 2014 |

| CD: intestinal biopsy Gastroenteritis: feces Periodontal disease: deep periodontal pockets Superficial soft tissue or bone infections Male: Non-gonococcal, non-chlamydial urethritis Non-gonococcal urethritis Superficial necrotic or gangrenous lesions Penile wound Female: Perineal, genital and peripheral ulcers Genital tract: excess vaginal discharge; lower genital tract symptoms |

|||

| Health status unavailable: Amniotic fluid; urine |

Clinical relevance of human hosted Campylobacter species.

Campylobacter species that have established associations with human diseases or have been isolated from a sterile site.

C. concisus

C. concisus has a curved or spiral shape and a single polar flagellum, with the size being 0.5–1 by 4 μm (Tanner et al., 1981). Its colony appears as convex shaped, translucent and is ~1 mm in diameter (Tanner et al., 1981). In early literature, C. concisus was described as a microaerophile, due to the growth of this bacterium under microaerophilic atmosphere enriched with hydrogen (H2) (Lastovica, 2006). Later, Lee et al. demonstrated that C. concisus is not a microaerophile, as they found that none of the 57 C. concisus strains grew in the microaerophilic conditions generated using the Oxoid BR56A and CN25A gas-generation systems (Lee et al., 2014). These C. concisus strains were able to grow under anaerobic conditions, with tiny colonies observed after 3 days of culture under anaerobic conditions, showing that C. concisus is an anaerobic bacterium. The anaerobic condition used in the study was generated using AN25A gas-generation system which absorbs oxygen with simultaneous production of CO2.

C. concisus is a chemolithotrophic bacterium, capable of using H2 as a source of energy to markedly increases its growth (Lee et al., 2014). C. concisus is able to oxidize H2 under both anaerobic and microaerobic conditions, although greater growth was observed under anaerobic conditions in the presence of 2.5–10% H2 (Lee et al., 2014). C. concisus is catalase negative, contributing to its inability to grow under microaerobic conditions (Tanner et al., 1981).

Transmission of C. concisus

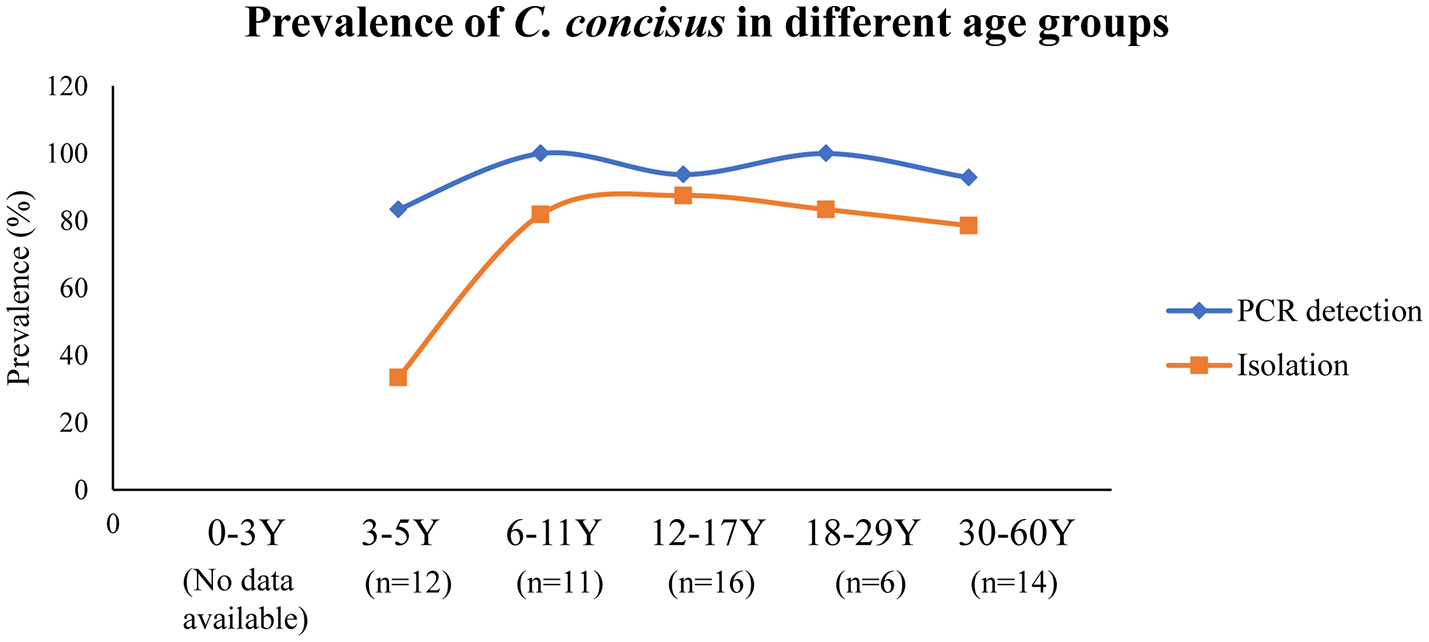

Currently, humans are the only known hosts of C. concisus with oral cavity being its natural colonization site (Zhang et al., 2010; Mahendran et al., 2013). C. concisus has been isolated from saliva samples of children as early as 3 years old, although the positive isolation rate was significantly lower than the other age groups (33 vs. 79–88%); and the highest C. concisus isolation rate was seen in the age group of 12–17 (Zhang et al., 2010) (Figure 2). When a PCR method was used for detection, the children from the 3 to 5 years old age bracket had a detection rate that was similar to other age groups (83 vs. 93–100%). These data show that although C. concisus colonize humans at the early stages of life, 3–5 year old children have lower bacterial loads of C. concisus in their saliva as compared to older children and the adults. Currently, no data are available regarding C. concisus colonization in children below 3 years old.

Figure 2

Detection and isolation rates of C. concisus from saliva samples in different age groups. The PCR detection rate of C. concisus from children of different age groups varied between 80 and 100%. However, the isolation rate of C. concisus from children at 3–5 years was only 33% (4/12), which was significantly lower than that in other age groups, indicating younger children were colonized with lower numbers of bacteria. Data are from Zhang et al. (2010).

Given that C. concisus colonizes the oral cavity, transmission would occur through saliva. The stability of C. concisus in saliva samples is related to sample storage. We were able to isolate C. concisus from saliva samples stored at 4°C for 3–6 days. However, we were unable to isolate C. concisus from the same saliva samples after storage at room temperature for 24 h. This suggests that in addition to direct contact, C. concisus contaminated food or drinks, particularly those stored in refrigerators, may also play a role in C. concisus transmission. Multiple strains of C. concisus have been isolated from saliva samples and enteric samples of given individuals, suggesting a possible dynamic colonization of new C. concicus strains in the human gastrointestinal tract (Ismail et al., 2012).

Association of C. concisus with human diseases

Gingivitis and periodontitis

Gingivitis is a common bacterial disease which affects 90% of the population (Coventry et al., 2000). The oral mucosa consists of stratified squamous epithelial cells (Lumerman et al., 1995). Periodontitis develops when gingivitis is not well-treated (Pihlstrom et al., 2005). As disease progresses, a loss of attachment between the gingivae and the teeth leads to the formation of a periodontal pocket, which then allows extensive colonization by anaerobic bacteria causing further inflammation of the mucosa (Highfield, 2009). In periodontitis patients, higher proportions of Gram-negative and anaerobic bacterial species are present in the oral cavity as compared to healthy controls (Newman and Socransky, 1977). C. concisus was initially isolated from the oral cavity of patients with gingivitis and periodontitis (Tanner et al., 1981). However, studies have not revealed a clear association between C. concisus and gingivitis and periodontitis, its role in human oral inflammatory diseases remains unclear.

Barrett's esophagus

The esophagus is a muscular conduit with stratified squamous epithelial layers; its mucosa is colonized by microbes dominated by members of the genus Streptococcus (Di Pilato et al., 2016). Disturbances of the microbiota composition, such as the abnormal enrichment of some Gram-negative bacteria including Campylobacter spp. has been reported to be associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and is suggested to contribute to the development toward Barrett's esophagus and oesophageal adenocarcinoma (Di Pilato et al., 2016).

By analyzing the microbiome composition in biopsy samples of the distal esophagus collected from normal individuals and patients with esophagitis or Barrett's esophagus, Yang et al. found that type I microbiome (Gram-positive aerobic microbiome) was mainly associated with normal esophagus (11/12, 91.7%), while type II microbiome (Gram-negative anaerobic microbiome) was more closely associated with abnormal esophagus including esophagitis and Barrett's esophagus (13/22, 59.1%) (Yang et al., 2009). Furthermore, Campylobacter species was found to be one of the genera with increased abundance in type II microbiome (Yang et al., 2009).

By using bacterial cultivation methods, Macfarlane et al. found that high levels of C. concisus and C. rectus were present in oesophageal aspirate and mucosal samples of patients with Barrett's esophagus, but not in control subjects (Macfarlane et al., 2007). Similar findings were reported by another study, in which the Campylobacter genus dominated by C. concisus colonized patients with GERD and Barrett's esophagus with increased bacterial counts, accompanied by a significant decrease in bacterial counts for all other genera (Blackett et al., 2013). This relationship was not observed in patients with oesophageal adenocarcinoma. It is possible that C. concisus contributes to the inflammation associated with GERD and Barrett's esophagus.

Gastroenteritis

Gastroenteritis is an inflammatory condition of the gastrointestinal tract which is characterized by diarrhea, abdominal pain, fever and vomiting (Galanis, 2007). It is usually self-limiting within 2–5 days (Galanis, 2007). Gastroenteritis can be caused by bacteria, viruses, parasites and fungi; the most common causes are rotavirus and bacterial species such as Escherichia coli, C. jejuni, and C. coli (Galanis, 2007).

A number of studies have reported the isolation of Campylobacter species other than C. jejuni and C. coli in diarrheal stool samples. Lindblom et al. found that in stool samples from diarrheal patients, Campylobacter upsaliensis, Campylobacter sputorum, and C. concisus were the most common species in addition to C. jejuni, of which C. concisus was only isolated from children (Lindblom et al., 1995). Similarly, Lastovica et al. reported that in addition to C. jejuni, C. concisus was the second most frequently isolated Campylobacter species from diarrheic stools of pediatric patients (Lastovica and Roux, 2000). Nielsen et al. also found that C. concisus was more frequently found in diarrheal stool samples of young children and elderly (Nielsen et al., 2013). The same group later reported a clinical study comparing clinical manifestations between adult patients infected with C. concisus and C. jejuni/C. coli, and they showed that although C. concisus infection seems to induce a milder course of acute gastroenteritis in comparison to that induced by C. jejuni/C. coli, it is associated with prolonged diarrhea (Nielsen et al., 2012). Recently, Serichantalergs et al. reported a significantly higher detection rate of C. concisus in traveller's diarrhea cases as compared to that in asymptomatic controls in Nepal (Serichantalergs et al., 2017). Another recent study by Tilmanne et al. showed that C. concisus had a similar prevalence in children with acute gastroenteritis as compared with the control group (Tilmanne et al., 2018). Unfortunately, most of the studies that reported the isolation of C. concisus from diarrheal stool samples did not have control fecal samples from healthy individuals, making it difficult to judge the role of this bacterium in gastroenteritis; and for those studies with control groups included, the results were controversial. Thus, whether C. concisus plays a role in gastroenteritis remains to be investigated.

Inflammatory bowel disease

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the gastrointestinal tract with Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) being two of its major forms (De Souza and Fiocchi, 2016). The two forms of IBD mainly differ in pathology. CD is characterized by having discontinuous “skip lesions” of transmural inflammation and the abnormalities can be found throughout the gastrointestinal tract (Walsh et al., 2011). In contrast to CD, the inflammation involvement for UC is usually confined to the mucosa and submucosa without skip lesions and mostly occurs in the large intestine (Walsh et al., 2011).

The etiology of IBD is not fully understood. Accumulated evidence has suggested that the mucosal immune system in genetically predisposed individuals has mounted responses to intestinal commensal bacterial species, which is believed to contribute to the pathogenesis of IBD (Knights et al., 2013). Intestinal commensal bacterial species have co-evolved with the intestinal mucosal immune system thus the immune responses to intestinal commensal bacterial species would need an external trigger. Microbes that have the ability to cause a prolonged primary intestinal barrier defect or alter the mucosal immune system are more likely to trigger IBD.

C. concisus is commonly present in the oral cavities of almost all individuals. However, patients with IBD have a significantly higher prevalence of C. concisus detected in their intestinal tissues as compared to healthy controls (Zhang et al., 2009, 2014; Man et al., 2010b; Mahendran et al., 2011; Mukhopadhya et al., 2011; Kirk et al., 2016). Comparison of the housekeeping genes and genomes of oral and enteric C. concisus strains suggests that enteric strains originate from oral C. concisus strains (Ismail et al., 2012; Chung et al., 2016).

C. concisus, C. hominis, C. showae, and C. ureolyticus have also been isolated from patients with CD. Additionally, C. homonis, C. showae, C. rectus, C. gracilis, and C. ureolyticus have been detected from fecal specimens of children with newly diagnosed CD (Zhang et al., 2009; Man et al., 2010b). However, no association has been found between the prevalence of these Campylobacter species in CD patients and healthy controls.

Genomospecies of C. concisus

C. concisus strains can be separated into two major genomospecies (GS), consistently defined by the analysis of core genomes and housekeeping genes (Istivan, 2005; Miller et al., 2012; Mahendran et al., 2015; Chung et al., 2016; Nielsen et al., 2016). C. concisus 23S rRNA gene has polymorphisms, which was also used to define the genomospecies by comparison of the entire 23S rRNA gene sequence or PCR amplification of 23S rRNA gene fragments (Engberg et al., 2005; Kalischuk and Inglis, 2011; On et al., 2013; Huq et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2017).

Quantitative PCR methods targeting the polymorphisms of the 23S rRNA gene revealed that there were more GS2 than GS1 C. concisus in samples collected from the upper and lower gastrointestinal tract of both patients with IBD and healthy controls, suggesting that GS2 C. concisus is better adapted to the human gastrointestinal tract (Wang et al., 2017). A meta-analysis of the composition of the isolated GS1 and GS2 C. concisus strains showed similar findings except that in healthy individuals, a significantly lower number of GS2 C. concisus strains than GS1 C. concisus were isolated from fecal samples. This suggests a potential difference in the C. concisus strains or the enteric environment between patients with gastrointestinal diseases and healthy controls (Wang et al., 2017).

The two GS of C. concisus do not differ in morphology but have GS-specific genes and may have different pathogenic potentials. By examining C. concisus strains isolated from diarrheal fecal samples, Engberg et al. found that bloody diarrhea was only present in individuals infected with GS2 C. concisus strains (Engberg et al., 2005). Furthermore, Kalischuk and Inglis demonstrated that GS2 C. concisus exhibited higher levels of epithelial invasion and translocation (Kalischuk and Inglis, 2011). Similarly, Ismail et al. reported that the oral C. concisus strains that were more invasive to intestinal epithelial cells were GS2 strains (Ismail et al., 2012).

Recently, comparative genomic analyses have identified two novel genomic islands CON_PiiA and CON_PiiB that carry proteins homologous to the type IV secretion system, LepB-like and CagA-like effectors (Chung et al., 2016). CON_PiiA and CON_PiiB were found in strains from both GS1 and GS2 (Chung et al., 2016). The effects of the proteins possessed by CON_PiiA and CON_PiiB on human cells require further examination.

Both GS1 and GS2 contain diverse C. concisus strains. The isolation sources of C. concisus strains do not seem to contribute to the phylogenetic relatedness. C. concisus strains isolated from saliva, intestinal biopsies and feces are found in both GS1 and GS2, as are the strains isolated from patients with enteric disease and healthy controls. A recent study examining the genomes of 104 C. concisus strains isolated from saliva, mucosal biopsies and fecal samples of patients with IBD, gastroenteritis and healthy individuals showed that sampling site rather than disease phenotype was associated with the particular GS (Kirk et al., 2018). In that study, authors reported that genes involved in cell membrane synthesis were common in oral strains, while those related to cell transport, metabolism, and secretory pathways were more often found in enteric isolates. These results indicate that GS alone is unable to differentiate virulent C. concisus strains from commensal strains.

A recent study reported the identification of an exoprotein named C. concisus secreted protein 1 (Csep1) (Liu et al., 2018). The csep1 gene was found to be localized in the bacterial chromosome and the pICON plasmid. The chromosomally encoded csep1 gene was only found in GS2 C. concisus strains, while the pICON plasmid encoded csep1 gene was found in both GS1 and GS2 strains. Some csep1 genes contained a six-nucleotide insertion at the position 654–659 bp (csep1-6bpi). Importantly, the csep1-6bpi gene in oral C. consisus strains was found to be associated with active CD. So far, the csep1-6bpi gene is the only molecular marker in C. concisus reported to have an association with IBD.

Pathogenic mechanisms of C. concisus

Motility, adhesion, and invasion

Campylobacter movement through the mucus layer is driven by its polar flagellum, which is crucial for approaching, attaching, and invading the intestinal epithelial cells (Young et al., 2007). In C. jejuni, the extracellular flagella filament is composed of multimers of flagellin proteins with a major flagellin protein FlaA and a minor flagellin protein FlaB. FlaA has been shown to be essential for invasion of INT 407 cells and optimal colonization in chicken gut (Wassenaar et al., 1991, 1993). The flagellum also serves as a type III secretion system for transportation of Campylobacter invasion antigens to the host cells (Buelow et al., 2011; Neal-Mckinney and Konkel, 2012; Samuelson et al., 2013).

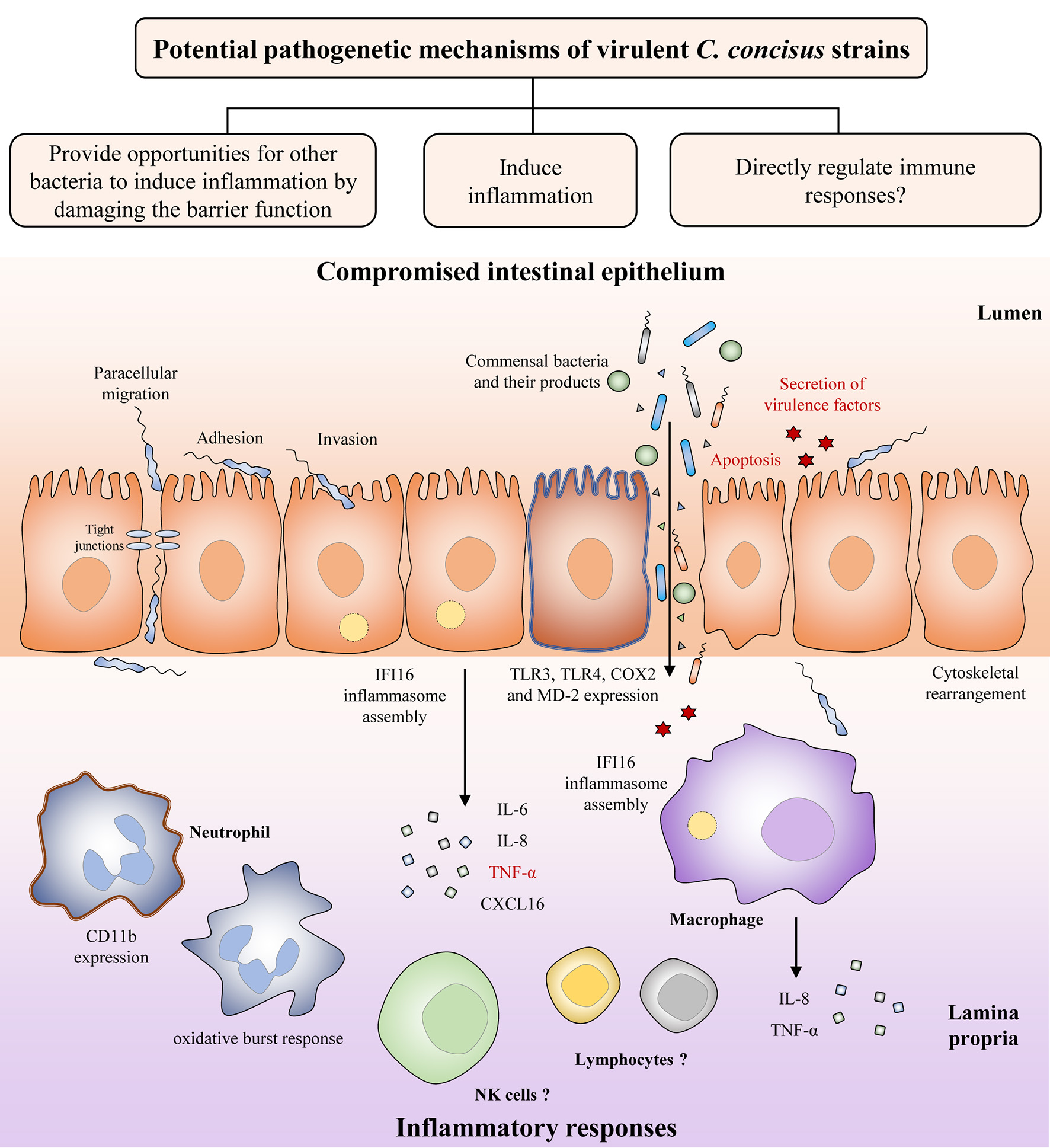

Both C. concisus and C. jejuni are spiral shaped. Unlike C. jejuni. which can have either single or bi-polar flagella, C. concisus only has a single polar flagellum. Although the flagellum in C. concisus has not been comprehensively investigated, studies have shown that C. concisus flagellum might be a virulence factor that contributes to its pathogenicity. Man et al. have observed flagellum mediated attachment and invasion of C. concisus to Caco-2 cells (Figure 3) (Man et al., 2010a).

Figure 3

Potential pathogenetic mechanisms of virulent C. concisus strains. Once it reaches the intestine, C. concisus adheres and invades the epithelium with the help of its flagellin and spiral shape. This is followed by a number of host responses such as cytoskeletal rearrangement, inflammasome assembly, expression of toll-like receptors, and the release of proinflammatory cytokines. Expression of virulence factors such as the zonula occludens toxin also results in proinflammatory cytokine production, as well as apoptosis (colored in red). The resulting compromised intestinal epithelium allows the increased translocation of commensal bacteria and their products from the lumen to the lamina propria. Proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines released by intestinal epithelial cells recruit immune cells to the site of infection and contributes to inflammatory response development.

Several studies have examined the motility of C. concisus strains isolated from saliva, feces and intestinal biopsies of patients with IBD, gastroenteritis, and healthy individuals. The motility was shown to be strain dependent, and no statistically significant association was found between patients and healthy controls (Lavrencic et al., 2012; Ovesen et al., 2017). The authors also reported that the motility of C. concisus was lower than that of C. jejuni and C. fetus (Ovesen et al., 2017). Furthermore, comparative genomic analysis of C. concisus strains had identified proteins required for flagellin glycosylation pathway, which may affect bacterial flagellar filament assembly, autoagglutination, adhesion and invasion (Kaakoush et al., 2011).

Bacterial flagella are also involved in forming biofilm, a bacterial interaction that is important for its survival in the host (Reeser et al., 2007; Svensson et al., 2014). C. concisus was also shown to have the ability to form biofilms, and this ability did not differ between the strains examined (Lavrencic et al., 2012).

Damaging the intestinal epithelial barrier

The intestinal epithelium is constructed by simple columnar epithelial cells (Clevers, 2013). Increased intestinal permeability is known to be associated with a number of chronic human diseases including IBD, being considered as a risk factor for its development (Hollander et al., 1986; Wyatt et al., 1993; Irvine and Marshall, 2000; D'Incà et al., 2006; Meddings, 2008). A compromised intestinal epithelial barrier may lead to loss of tolerance to the commensal enteric microbiota. Using in vitro cell culture models, several studies have indicated that C. concisus is able to increase the intestinal permeability. The intestinal epithelial permeability in Caco-2 cells was increased following C. concisus infection, and C. concisus also induced movement of tight junction proteins zonula occludens-1 and occludin from cell membrane into cytosol (Figure 3) (Man et al., 2010a). These changes in tight junction protein arrangement significantly increased the barrier permeability (Man et al., 2010a). These effects were also observed in HT-29/B6 intestinal epithelial cells, in which the cell monolayers infected with both oral and fecal C. concisus strains revealed epithelial barrier dysfunction (Nielsen et al., 2011).

Induction of proinflammatory cytokines

Inflammatory cytokines are produced in enteric infections (Figure 3). C. concisus strains were able to stimulate the productions of interleukin (IL)-8 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α in THP-1 macrophages, and the productions of IL-8 and cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 in HT-29 cells (Man et al., 2010a; Ismail et al., 2013). COX-2 is an enzyme responsible for producing prostaglandins and other inflammatory mediators (Williams et al., 1999). Some C. concisus strains, mostly those isolated from patients with IBD, have been shown to upregulate surface expression of lipopolysaccharides (LPS) receptors including Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 and myeloid differentiation factor 2 in HT-29 cells (Ismail et al., 2013). Activation of neutrophil adherence molecule CD11b and oxidative burst response have been shown in neutrophils following C. concisus infection (Sørensen et al., 2013). Additionally, by using transcriptomics analysis, assembly of IFI16 inflammasome has been observed in both intestinal epithelial cells and macrophages following C. concisus infection (Kaakoush et al., 2015; Deshpande et al., 2016). The IFI16 inflammasome plays important role in the innate immune responses, acting as a nuclear pathogen sensor that promotes caspase-1 activation (Xiao, 2015). Production of mature proinflammatory cytokines, IL-1β, and 1L-18, is caspase-1 dependent (Xiao, 2015). A recent study has found that C. concisus was able to elevate the mRNA expression of p53, TNF-α, and IL-18 in Barrett's cell lines, however these effects have not been demonstrated at protein level (Namin et al., 2015).

Flagellin from various Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria are capable of triggering nuclear factor kappa light chain enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) signaling responses in intestinal epithelial cells, where it is recognized by TLR5 expressed on the surface of the host cells (Eaves-Pyles et al., 2001; Gewirtz et al., 2001). The conserved region on flagellin that is recognized by TLR5 has been studied in Salmonella typhimurium (Smith et al., 2003). Campylobacter flagellin shares limited sequence similarity with that of S. typhimurium, which explains why it is a poor stimulator of TLR5 (Watson and Galán, 2005). Studies have demonstrated that C. jejuni, C. coli, and C. concisus have limited potential to activate TLR5 (De Zoete et al., 2010; Ismail et al., 2013).

To date, only two virulence factors of C. concisus have been characterized, one of which is the zonula occludens toxin (Zot). Initially described in Vibrio cholerae, Zot is a known virulence factor that causes an increase in intestinal permeability. The zot genes in Campylobacter species are encoded by prophages and are divided into two clusters, which encode ZotCampyType_1 and ZotCampyType_2, respectively (Zhang et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2016). Although the two types of Zot toxins share common motifs, their overall sequence identities vary greatly, particularly at the C-terminal compartment (Liu et al., 2016). Mahendran et al. have detected a similar prevalence of the cluster 1 zot gene in the oral C. concisus strains isolated from patients with IBD and healthy controls (Mahendran et al., 2013). Later on, Mahendran and colleagues found that the ZotCampyType_1 caused prolonged damage on Caco-2 monolayers (Mahendran et al., 2016). The damaging effect is different from that of V. cholerae Zot which induces transient and reversible damage to the intestinal epithelium (Fasano et al., 1991). This prolonged damaging effect induced by C. concisus Zot is at least partially due to the induction of cell apoptosis and/or intestinal epithelial cell production of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-8 (Mahendran et al., 2016). Furthermore, pre-exposure to Zot causes increased phagocytosis of E. coli K12 by THP-1 macrophages, suggesting a possible role for C. concisus in enhancing responses of macrophages to other enteric bacterial species (Mahendran et al., 2016). Additionally, transcriptomics analysis showed that C. concisus Zot was able to upregulate the expression of TLR3, proinflammatory cytokines IL-6, IL-8, and chemokine CXCL16 (Deshpande et al., 2016). The zot-containing prophages are also found in a number of other human and animal hosted Campylobacter species including C. ureolyticus, Campylobacter corcagiensis, C. gracilis, C. jejuni, Campylobacter hyointestinalis, and Campylobacter iguanorium, however their pathogenic effects on human cells have not been examined (Liu et al., 2016).

In additional to Zot, another C. concisus virulence factor characterized is the membrane protein phospholipase A. Istivan et al. have examined the activity of haemolytic phospholipase A2 (PLA2) from C. concisus strains isolated from children with gastroenteritis and found that PLA2 activity is detected in strains from both GS. Membrane extracts containing PLA2 exhibited cytolytic effects on CHO cells, supporting the idea that C. concisus may have potential to cause tissue destruction related to intestinal inflammation (Istivan et al., 2004).

To date, only one study has examined the effects of C. concisus in animal model (Aabenhus et al., 2008). Mice displayed a significant loss of body weight between day 2 and day 5 following C. concisus inoculation via gastric route. Signs of inflammation in the gut were not consistently found, but micro abscesses were found in liver of infected animals. Additionally, infiltration of lymphocytes was also observed in the jejunum and colon of infected mice. However, the details of the C. concisus strains used were not provided.

Responses to environmental factors

Environmental factors present in the gastrointestinal tract such as bile and pH have been found to affect the growth of C. concisus in vitro (Ma et al., 2015). Reduction in C. concisus growth was observed with lower pH. The gastric pH values in patients with CD and UC range between 1.5–4.1 and 1.55–4.4, respectively, which are significantly higher than those in healthy individuals (0.95–2.6) (Press et al., 1998). Under laboratory conditions, C. concisus strains were unable to grow following exposure to pH 2 for 30 min, while only 20% of the strains were able to survive following exposure to pH 3.5 for 30 min, and exposure to pH 5 for 120 min had minor effects on C. concisus growth (Ma et al., 2015). The sensitivity of C. concisus toward low pH suggests that the acidic environment may prevent C. concisus from colonizing the stomach and intestinal tract. The less acidic gastric environment observed in patients with IBD may provide a better condition for C. concisus colonization (Press et al., 1998). Recently, Ma et al. reported that the derivatives of the food additive, fumaric acid, were able to enhance the growth of C. concisus strains (Ma et al., 2018). It was found that C. concisus strains showed the greatest increase in growth when cultured in media containing 0.4% of neutralized fumaric acid, neutralized monosodium fumarate and sodium fumarate. These results imply that removal of fumaric acid and its salts from diet of patients with IBD may help to improve their condition.

Campylobacter species have different ability in bile resistance. Some oral C. concisus strains are able to grow in the presence of 2% bile, suggesting they are able to survive in the enteric environment. Enteric Campylobacter species such as C. jejuni and C. hominis are bile resistant. Fox et al. have demonstrated that although significant growth inhibition was observed when C. jejuni was cultured in the presence of 2.5% bile, C. jejuni was still able to proliferate in cultures containing 5% bile (Fox et al., 2007). Lawson et al. showed that C. hominis strains isolated from stool samples were able to tolerate 2% bile (Lawson et al., 2001).

Antimicrobial resistance of C. concisus

There has been an increase in antibiotic resistance in Campylobacter isolates from both humans and animals worldwide (Luangtongkum et al., 2009; Iovine, 2013). Among antimicrobial therapies for treatment of Campylobacter enteritis, fluoroquinolones, and macrolides are most commonly used, while tetracyclines are rarely used (Alfredson and Korolik, 2007). Intravenous aminoglycosides are sometimes used to treat serious bacteraemia and other Campylobacter induced systemic infections (Alfredson and Korolik, 2007). Campylobacter species resist antibiotics by several mechanisms such as modification or occupation of target sites thus preventing the binding of antibiotic compounds; efflux pump systems that reduce intracellular antibiotic concentrations; changes in bacterial membrane permeability that prevents entering of antibiotic compounds; and hydrolysis of antibiotic compounds (Alfredson and Korolik, 2007; Iovine, 2013). The resistance determinants in C. jejuni and C. coli and their mechanisms of action have been widely studied, however the resistance determinants in C. concisus have not been investigated in detail. It is thought that antibiotics resistance has not developed in C. concisus as it is susceptible to a variety of antibiotics, of which tetracycline, erythromycin, ciprofloxacin, and macrolides are most commonly reported (Johnson et al., 1986; Aabenhus et al., 2005; Vandenberg et al., 2006; Nielsen et al., 2013). Ciprofloxacin, along with other antibiotics, have been shown to be effective in treating certain phenotypes of CD (Sartor, 2004).

Antibiotics are used as primary or adjuvant treatment along with anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive drugs for the treatment of IBD (Sartor, 2004). Antibiotics are used to selectively reduce tissue invasion, decrease luminal, and mucosal bacterial loads and their translocation (Sartor, 2004). Some patients with IBD are colonized with multiple C. concisus strains, and a significantly higher prevalence of multiple oral C. concisus strains in patients with active IBD than healthy controls has been reported (Mahendran et al., 2013). Furthermore, for IBD patients who are in remission, those without antibiotic treatment usually have a higher prevalence of multiple oral C. concisus strains than those who were receiving antibiotics, indicating antibiotics were able to alleviate but not eradicate C. concisus growth in the intestinal tract (Mahendran et al., 2013).

In addition to antibiotics, the antimicrobial potentials of immunomodulating and anti-inflammatory drugs used for IBD treatments have not been widely tested. Immunosuppressive drugs such as azathioprine (AZA) and mercaptopurine (MP) used in the treatment of IBD have been reported to exhibit inhibitory effect on the growth of C. concisus strains, with the effect of AZA being more potent than MP (Liu F. et al., 2017). In their use as immunosuppressive drugs, both AZA and MP are eventually metabolized to purine analogs that interfere with DNA synthesis in immune cells (Nielsen et al., 2001). However, bioinformatics analysis has not identified all the enzymes required for AZA and MP metabolism in the C. concisus genome, indicating the inhibitory action of AZA and MP on C. concisus growth is not through the conventional pathway. AZA and MP can also reduce the growth of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis, another bacterium that is associated with human CD (Sanderson et al., 1992; Collins et al., 2000; Sieswerda and Bannatyne, 2006; Greenstein et al., 2007; Shin and Collins, 2008).

5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) is an anti-inflammatory drug that is also commonly used to induce and maintain remission in IBD (Hanauer, 2006; Nikfar et al., 2009). Its effect on C. concisus growth varies between strains as it inhibits the growth of some C. concisus strains, while it promotes the growth of other strains, features which appears to be independent of C. concisus GS (Schwartz et al., 1982). Although 5-ASA is often used in the treatment of IBD, in some cases 5-ASA medications are found to cause exacerbations of colitis (Schwartz et al., 1982). The enhancement of C. concisus growth induced by 5-ASA may have implications in the deteriorated clinical conditions observed in patients with IBD following 5-ASA medications.

While antimicrobials may be effective in limiting the growth of C. concisus in the intestinal tract, continuous transportation of C. concisus from the oral cavity along with saliva and food makes eradication of this bacterium a challenge. Thus, antimicrobials targeting C. concisus in the oral cavity, particularly virulent strains, should be developed.

C. rectus

C. rectus (formerly named as Wolinella recta) is a small, straight, rod shaped, single polar flagellated bacterium with the size being 0.5 by 2–4 μm (Tanner et al., 1981). The colonies of C. rectus appear as convex shaped and spread or corrode blood agar plates (Tanner et al., 1981). C. rectus was initially identified using anaerobic condition consisting of 80% N2, 10% CO2, and 10% H2, although the study indicated that some stains can grow in the presence of 5% oxygen (Tanner et al., 1981). A number of studies have used anaerobic conditions for the isolation of C. rectus from different clinical samples such as dental plaques, feces, and oesophageal mucosal biopsies (Rams et al., 1993; Gmur and Guggenheim, 1994; Von Troil-Lindén et al., 1995; Lastovica and Roux, 2000; Macuch and Tanner, 2000; Macfarlane et al., 2007). A study comparing different atmospheric conditions on the growth of C. rectus demonstrated that its growth could be observed at 30, 35, and 42°C under anaerobic conditions; in contrast it did not grow in a conventional microaerophilic atmosphere consisting 5% O2, 10% CO2, and 85% N2 (Mahlen and Clarridge, 2009). Given all these findings, C. rectus is an anaerobic bacterium instead of microaerophilic bacterium.

C. rectus was first isolated from individuals with periodontal diseases (Tanner et al., 1981). It has since been isolated from various locations of the oral cavity including periodontal sulcus, tongue, cheek mucosa, and saliva (Könönen et al., 2007; Cortelli et al., 2008). C. rectus is predominantly localized in the middle and deep periodontal pocket zones, and tends to form clumps in tooth-attached and epithelium associated plaque areas (Noiri et al., 1997). A number of studies have reported the association between C. rectus and periodontal diseases. Macuch and Tanner detected C. rectus from 90% (42/47) of the subgingival sites of initial and established perondontitis individuals, which was signficianlty higher than that from gingivitis subjects (20%, 3/14) and healthy controls (10%, 2/18) (Macuch and Tanner, 2000). Dibart et al. also showed that C. rectus had a signfiicantly higher prevalence in supragingival plaque obtained from periodontally diseased subjects as comapred with healthy individuals (7/24 vs. 0/27) (Dibart et al., 1998). Furthermore, von Troil-Lindenl et al. reported that C. rectus was more frequently detected in saliva samples of subjects with advanced periondontitis (100%, 10/10) as comapred with individuals with initial or no periondontitis (40%, 4/10) (Von Troil-Lindén et al., 1995). Additionally, several studies have examined the prevalence of C. rectus in periondontitis patients with different disease status, however healthy subjects were not included. Several virulence factors of C. rectus including LPS, GroEL-like protein, and surface-layer protein have been characterized.

C. rectus acts as a stimulator of inflammation in the gingival tissue. It has been shown to enhance the production of IL-6 and IL-8 in human gingival fibroblasts (Dongari-Bagtzoglou and Ebersole, 1996). IL-6 is a multifunctional cytokine, as it can be both proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory, and its secretion is thought to drive the tissue damaging process in diseases such as periodontal disease (Irwin and Myrillas, 1998). C. rectus LPS is able to stimulate both plasmin activity and plasminogen activator activity in human gingival fibroblasts (Ogura et al., 1995). Plasmin is an enzyme that is converted from plasminogen via plasminogen activator catalysis (Martel-Pelletier et al., 1991). Plasmin is present in blood which degrades many blood plasma proteins such as fibrin clots (Martel-Pelletier et al., 1991). Significantly enhanced activities of plasmin and plasminogen activator activities have been observed in gingival fluid in periodontal disease (Hidaka et al., 1981; Talonpoika et al., 1990). Furthermore, C. rectus LPS also induces higher levels of IL-6 and prostaglandin E2 productions in aged human gingival fibroblasts as compared with those in younger cells, which may explain the increased susceptibility of periodontal disease in aged individuals (Ogura et al., 1996; Takiguchi et al., 1996, 1997).

The C. rectus GroEL-like protein is a 64 kDa protein with antigenic properties (Hinode et al., 1998). It was found to cross-react with antibodies against human heat shock protein 60, Helicobacter pylori whole cells and the GroEL-like protein from Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, a bacterial species that is associated with localized aggressive periodontitis (Hinode et al., 1998, 2002; Tanabe et al., 2003; Henderson et al., 2010). The C. rectus GroEL-like protein is also able to stimulate the production of IL-6 and IL-8 from the human gingival fibroblast monolayer (Hinode et al., 1998). The C. rectus GroEL-like protein is also found to possess immunodominant epitopes within both amino and carboxyl termini, and it may share same carboxyl epitopes with the C. rectus surface-layer (S-layer) protein (Hinode et al., 2002).

The S-layer is a monomolecular layer of a single secreted protein surrounding the entire surface which is found in almost all archaea and some Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria (Konstantinov et al., 2008). The S-layer protein (SLP) in C. fetus and C. rectus have been previously characterized, and the gene encoding SLP is also carried by C. showae (Tay et al., 2013). The C. rectus SLP has a molecular weight ranging between 130 and 166 kDa (Kobayashi et al., 1993; Nitta et al., 1997). C. rectus strains expressing SLP are resistant to complement and phagocytic mediated killing in the absence of specific antibodies (Okuda et al., 1997). However, C. rectus SLP does not play a major role in bacterial adhesion. C. rectus strains lacking the crsA gene which encodes the SLP protein are less effective at adhering to Hep-2 oral epithelial cells, with CrsA+ cells only 30 to 50% more adherent than the CrsA- cells (Wang et al., 2000). The CrsA- cells exhibit no difference in inducing the production of IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α in Hep-2 cells as compared with CrsA+ cells. However, CrsA- C. rectus strains induce higher levels of these cytokines at early time points of the infection, suggesting that the S-layer in C. rectus may facilitate bacterial survival at the site of infection by delaying the cytokine responses (Wang et al., 2000).

Macrolides are a class of antibiotics used to treat a wide variety of infections (Hirsch et al., 2012). It inhibits protein synthesis by acting on the P site of the 50S ribosomal subunit, thus preventing peptide elongation (Payot et al., 2006). The rRNA methylase enzyme encoded by the erythromycin ribosome methylase (erm) gene methylates a single adenine in the 23S component of the 50S subunit, which sterically hinders the proper interaction between the macrolide and the 50S subunit, providing antibiotic resistance (Weisblum, 1995). C. rectus is the only Campylobacter species that has the erm determinants described. These determinants include Erm B, Erm C, Erm F, and Erm Q, though their clinical implications have not been examined (Roe et al., 1995).

In addition to its role in periodontal disease, C. rectus has been implicated in the association between maternal periodontitis and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Madianos et al. reported that a significantly elevated level of fetal IgM to C. rectus was observed among premature infants as compared to full-term neonates, indicating that C. rectus, as a maternal oral pathogen, may act as a primary infectious agent in fetus that leads to prematurity (Madianos et al., 2001). Later study by the same group demonstrated that C. rectus mediated growth restriction in a pregnant mice model, as higher numbers of growth-restricted fetuses were observed in the groups subcutaneously challenged by C. rectus as compared to the non-challenged groups (Yeo et al., 2005). The same group also showed that maternal C. rectus infection increased fetal brain expression of proinflammatory cytokines IFN-γ (Offenbacher et al., 2005). Furthermore, Arce and colleagues demonstrated that C. rectus was more invasive to human trophoblasts as compared to C. jejuni, paralleled with significantly upregulated mRNA and protein expressions of IL-6 and TNF-α in a dose-dependent manner (Arce et al., 2010). Moreover, the study also showed that C. rectus was able to translocate in vivo from a distant site of infection to the fetoplacental unit (Arce et al., 2010). Taking together, these studies suggest that as a pathogen in the oral cavity, C. rectus has the potential to contribute to the adverse pregnancy outcomes.

C. ureolyticus

C. ureolyticus (formally known as Bacteroides ureolyticus) was first described in 1978 by Jackson et al., the strain was isolated from amniotic fluid using anaerobic condition (Jackson and Goodman, 1978). A later study has isolated C. ureolyticus from 103 superficial necrotic or gangrenous lesions. However, C. ureolyticus was rarely the sole bacterial species isolated from the site of infections, suggesting other microorganisms may be responsible for the pathogenesis of these diseases (Duerden et al., 1982).

C. ureolyticus has been frequently isolated from the genital tracts of both male and female. By examining the whole cell proteins of C. ureolyticus strains, Akhtar and Eley showed that strains isolated from urethra of men with and without non-gonococcal urethritis showed no difference in SDS-PAGE patterns (Akhtar and Eley, 1992). Later studies by Bennett et al. reported that C. ureolyticus was isolated from healthy individuals at a similar prevalence as compared with that from males and females presenting non-gonococcal urethritis (Bennett et al., 1990, 1991). These results indicate that C. ureolyticus is a part of the normal flora in the genital tract of both male and female.

In the past decades, C. ureolyticus has been considered as an emergent Campylobacter species in gastroenteritis as it is frequently isolated from fecal samples of patients presenting with diarrheal illness. By using a multiplex-PCR systems, Bullman et al. first reported the isolation of C. ureolyticus from feces of patients with gastroenteritis. Among all the Campylobacter positive samples being screened, 24% (83/349) was found to be positive for C. ureolyticus, of which 64% (53/83) had C. ureolycitus as the sole Campylobacter species detected (Bullman et al., 2011). By using PCR methods, another study by Bullman et al. also found that C. ureolyticus was the second most common non-C. jejuni/C. coli species in fecal samples collected from patients presenting diarrheal illness (Bullman et al., 2012). However, healthy controls were not included in these studies.

By combining the bacterial isolation and molecular detection methods, Collado et al. reported that C. ureolyticus is the third most prevalent species of the Campylobacteria family in diarrheic stool samples in addition to C. concisus and C. jejuni, but no statistical difference was found between the diarrheic and healthy groups (Collado et al., 2013). A recent study has also reported the detection of C. ureolyticus from traveler's diarrhea cases (Serichantalergs et al., 2017). This study showed that C. ureolyticus was detected at a similar prevalence in patients presenting diarrhea and healthy individuals.

Despite being frequently isolated or detected from diarrheal stool samples, the association between C. ureolyticus and diarrheal diseases has not been established. However, the pathogenic potentials of C. ureolyticus have been examined by a number of in vitro studies. Through whole genome sequencing of C. ureolyticus strains, genes encoding known virulence factors have been identified. These factors were involved in bacterial adhesion, colonization, invasion, and toxin production (Bullman et al., 2013). By using an intestinal epithelial cell line model, C. ureolyticus was shown to be capable of adhering to Caco-2 cells but unable to invade, with the bacterial adhesion followed by cellular damage and microvillus degradation. Furthermore, secretome analysis had also detected release of putative virulence and colonization factors (Burgos-Portugal et al., 2012).

Hariharan et al. reported the isolation of C. ureolyticus from endometria of apparently normal mares under anaerobic condition (Hariharan et al., 1994). So far, this is the only study has reported isolation of C. ureolyticus from animal sources.

C. gracilis

C. gracilis (formally known as Bacteroides gracilis) was first isolated by Tanner et al. in 1981 from patients with gingivitis and periodontitis (Tanner et al., 1981).

C. gracilis has been isolated from patients with periodontal and endodontic infections, however its pathogenetic role in these diseases is still controversial. Macuch et al. reported that in addition to C. rectus, C. gracilis was the most dominant Campylobacter species isolated from subgingival sites among eight Campylobacter species being examined. However, similar levels of C. gracilis were detected in healthy, gingivitis and periodontitis sites, suggesting that its prevalence or quantity was unrelated to periodontal health or disease (Macuch and Tanner, 2000). A study by Siqueira and Rocas examining the prevalence of C. gracilis in patients with primary endodontic infections also found that it was not associated with clinical symptoms of the diseases (Siqueira and Rocas, 2003).

The first complete genome of C. gracilis was sequenced by Miller et al., which lead to identification of genes encoding for virulence factors including haemagglutinins, Zot, immunity proteins and other putative pathogenic factors (Miller and Yee, 2015). Nevertheless, supporting evidence for the virulence of C. gracilis is still lacking.

C. showae, C. hominis, and C. curvus

C. showae was first isolated by Etoh et al. in 1993 from dental plaque of gingival crevices of healthy adults (Etoh et al., 1993). A study later by Macuch et al. examining the prevalence of oral Campylobacter species from subgingival sites showed that in addition to C. rectus, C. showae was also found more frequently and in higher levels from patients with periodontitis and gingivitis than from healthy controls (Macuch and Tanner, 2000).

C. hominis was first described in 1998 by Lawson et al. through Campylobacter specific PCR assays. C. hominis was detected from stool samples of 50% of the 20 healthy individuals, while it was absent in all the saliva samples of the same individuals (Lawson et al., 1998). Later in a study by Lawson et al., C. hominis was isolated from the fecal samples of healthy individuals (Lawson et al., 2001).

By using PCR methods targeting the Campylobacter 16S rRNA gene, C. showae and C. hominis have been detected from intestinal biopsy samples collected from macroscopically inflamed and noninflamed areas. Furthermore, this was the first study reported the isolation of C. concisus, C. showae, C ureolyticus, and C. hominis from intestinal biopsies (Zhang et al., 2009). A later study by Man et al. also detected C. showae and C. hominis from stool specimens collected from children with CD (Man et al., 2010b). However, no association was found between the prevalence of C. showae and C. hominis in patients with CD and healthy controls.

C. curvus (previously named as Wolinella curva) was first described in 1984 by Tanner et al. (Tanner et al., 1984). C. curvus is a rarely encountered Campylobacter species in humans. Lastovica et al. reported an isolation rate of C. curvus as low as 0.05% (2/4122) from diarrheic stools of pediatric patients (Lastovica and Roux, 2000). A study by Abbott et al. also isolated C curvus from stool samples and showed that the prevalence of C. curvus was associated with sporadic and outbreak of bloody gastroenteritis and Brainerd's diarrhea in Northern California (Abbott et al., 2005). There was one study which reported isolation of C. curvus and C. upsaliensis from stools of patients with Guillain-Barré syndrome and Fisher's syndrome (Koga et al., 1999). However, serological examination of the patient from whom C. curvus has been isolated did not detect antibodies to this bacterium.

Conclusion

Accumulated evidence from the past decade supports the role of human hosted C. concisus in the development of IBD and possibly Barrett's esophagus and GERD. Recently, a CD-associated C. concisus molecular marker csep1-6bpi has been identified, strongly suggests that csep1-6bpi positive C. concisus strains is a potential causative agent of human CD. In addition to C. concisus, the association between human hosted C. rectus and periodontal diseases has also been established.

Statements

Author contributions

FL played the major role in writing the review. LZ, RM, and YW provided critical feedback and helped in editing the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by a Faculty Research Grant awarded to LZ from the University of New South Wales (Grant No.: PS46772).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

- 5-ASA

5-aminosalicylic acid

- AZA

azathioprine

- CD

Crohn's disease

- CFU

colony forming unit

- COX

cyclooxygenase

- Erm

erythromycin ribosome methylase

- GERD

gastroesophageal reflux disease

- GS

genomospecies

- IBD

inflammatory bowel disease

- IFN

interferon

- IL

interleukin

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- MP

mercaptopurine

- NF-κB

nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- PLA2

phospholipase A2

- TLR

toll-like receptor

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- UC

ulcerative colitis

- Zot

zonula occludes toxin.

Abbreviations

References

1

Aabenhus R. Permin H. Andersen L. P. (2005). Characterization and subgrouping of Campylobacter concisus strains using protein profiles, conventional biochemical testing and antibiotic susceptibility. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.17, 1019–1024. 10.1097/00042737-200510000-00003

2

Aabenhus R. Stenram U. Andersen L. P. Permin H. Ljungh A. (2008). First attempt to produce experimental Campylobacter concisus infection in mice. World J. Gastroenterol.14, 6954–6959. 10.3748/wjg.14.6954

3

Abbott S. L. Waddington M. Lindquist D. Ware J. Cheung W. Ely J. et al . (2005). Description of Campylobacter curvus and C. curvus-like strains associated with sporadic episodes of bloody gastroenteritis and Brainerd's diarrhea. J. Clin. Microbiol.43, 585–588. 10.1128/JCM.43.2.585-588.2005

4

Akhtar N. Eley A. (1992). Restriction endonuclease analysis and ribotyping differentiate genital and nongenital strains of Bacteroides ureolyticus. J. Clin. Microbiol.30, 2408–2414.

5

Alfredson D. A. Korolik V. (2007). Antibiotic resistance and resistance mechanisms in Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett.277, 123–132. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00935.x

6

Arce R. Á. Diaz P. Barros S. Galloway P. Bobetsis Y. Threadgill D. et al . (2010). Characterization of the invasive and inflammatory traits of oral Campylobacter rectus in a murine model of fetoplacental growth restriction and in trophoblast cultures. J. Reprod. Immunol.84, 145–153. 10.1016/j.jri.2009.11.003

7

Bennett K. Eley A. Woolley P. (1991). Isolation of Bacteroides ureolyticus from the female genital tract. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis.10, 593–594. 10.1007/BF01967281

8

Bennett K. Eley A. Woolley P. Duerden B. (1990). Isolation of Bacteroides ureolyticus from the genital tract of men with and without non-conococcal urethritis. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis.9, 825–826. 10.1007/BF01967383

9

Bézian M. Ribou G. Barberis-Giletti C. Megraud F. (1990). Isolation of a urease positive thermophilic variant of Campylobacter lari from a patient with urinary tract infection. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis.9, 895–897. 10.1007/BF01967506

10

Blackett K. Siddhi S. Cleary S. Steed H. Miller M. Macfarlane S. et al . (2013). Oesophageal bacterial biofilm changes in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, Barrett's and oesophageal carcinoma: association or causality?Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther.37, 1084–1092. 10.1111/apt.12317

11

Blaser M. J. Glass R. I. Huq M. I. Stoll B. Kibriya G. Alim A. (1980a). Isolation of Campylobacter fetus subsp. jejuni from Bangladeshi children. J. Clin. Microbiol.12, 744–747.

12

Blaser M. J. Laforce F. M. Wilson N. A. Wang W. L. L. (1980b). Reservoirs for human Campylobacteriosis. J. Infect. Dis.141, 665–669.

13

Blaser M. J. Perez G. P. Smith P. F. Patton C. Tenover F. C. Lastovica A. J. et al . (1986). Extraintestinal Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli infections: host factors and strain characteristics. J. Infect. Dis.153, 552–559. 10.1093/infdis/153.3.552

14

Buelow D. R. Christensen J. E. Neal-Mckinney J. M. Konkel M. E. (2011). Campylobacter jejuni survival within human epithelial cells is enhanced by the secreted protein CiaI. ?Mol. Microbiol.80, 1296–1312. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07645.x

15

Bullman S. Corcoran D. O'leary J. Lucey B. Byrne D. Sleator R. D. (2011). Campylobacter ureolyticus: an emerging gastrointestinal pathogen?Pathog. Dis.61, 228–230. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2010.00760.x

16

Bullman S. Lucid A. Corcoran D. Sleator R. D. Lucey B. (2013). Genomic investigation into strain heterogeneity and pathogenic potential of the emerging gastrointestinal pathogen Campylobacter ureolyticus. PLoS ONE8:e71515. 10.1371/journal.pone.0071515

17

Bullman S. O'leary J. Corcoran D. Sleator R. Lucey B. (2012). Molecular-based detection of non-culturable and emerging campylobacteria in patients presenting with gastroenteritis. Epidemiol. Infect.140, 684–688. 10.1017/S0950268811000859

18

Burgos-Portugal J. A. Kaakoush N. O. Raftery M. J. Mitchell H. M. (2012). Pathogenic potential of Campylobacter ureolyticus. Infect. Immun.80, 883–890. 10.1128/IAI.06031-11

19

Campero C. M. Anderson M. Walker R. Blanchard P. Barbano L. Chiu P. et al . (2005). Immunohistochemical identification of Campylobacter fetus in natural cases of bovine and ovine abortions. Zoonoses Public Health52, 138–141. 10.1111/j.1439-0450.2005.00834.x

20

Chan F. Stringel G. Mackenzie A. (1983). Isolation of Campylobacter jejuni from an appendix. J. Clin. Microbiol.18, 422–424.

21

Chua K. Gürtler V. Montgomery J. Fraenkel M. Mayall B. C. Grayson M. L. (2007). Campylobacter insulaenigrae causing septicaemia and enteritis. J. Med. Microbiol.56, 1565–1567. 10.1099/jmm.0.47366-0

22

Chung H. K. Tay A. Octavia S. Chen J. Liu F. Ma R. et al . (2016). Genome analysis of Campylobacter concisus strains from patients with inflammatory bowel disease and gastroenteritis provides new insights into pathogenicity. Sci. Rep.6:38442. 10.1038/srep38442

23

Clevers H. (2013). The intestinal crypt, a prototype stem cell compartment. Cell154, 274–284. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.004

24

Collado L. Gutiérrez M. González M. Fernández H. (2013). Assessment of the prevalence and diversity of emergent Campylobacteria in human stool samples using a combination of traditional and molecular methods. DMID75, 434–436. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.12.006

25

Collins M. T. Lisby G. Moser C. Chicks D. Christensen S. Reichelderfer M. et al . (2000). Results of multiple diagnostic tests for Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and in controls. J. Clin. Microbiol.38, 4373–4381.

26

Control and Prevention (2006). Principles of Epidemiology in Public Health Practice: An Introduction to Applied Epidemiology and Biostatistics. Atlanta, GA: US Dept. of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention(CDC), Office of Workforce and Career Development.

27

Cortelli J. R. Aquino D. R. Cortelli S. C. Fernandes C. B. De Carvalho-Filho J. Franco G. C. N. et al . (2008). Etiological analysis of initial colonization of periodontal pathogens in oral cavity. J. Clin. Microbiol.46, 1322–1329. 10.1128/JCM.02051-07

28

Coventry J. Griffiths G. Scully C. Tonetti M. (2000). ABC of oral health: periodontal disease. BMJ321:36. 10.1136/bmj.321.7252.36

29

Cunningham C. Lee C. H. (2003). Myocarditis related to Campylobacter jejuni infection: a case report. BMC Infect. Dis.3:16. 10.1186/1471-2334-3-16

30

De Souza H. S. Fiocchi C. (2016). Immunopathogenesis of IBD: current state of the art. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.13:13. 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.186

31

De Vries J. Arents N. Manson W. (2008). Campylobacter species isolated from extra-oro-intestinal abscesses: a report of four cases and literature review. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis.27, 1119–1123. 10.1007/s10096-008-0550-2

32

De Zoete M. R. Keestra A. M. Roszczenko P. Van Putten J. P. (2010). Activation of human and chicken toll-like receptors by Campylobacter spp. Infect. Immun.78, 1229–1238. 10.1128/IAI.00897-09

33

Debruyne L. Gevers D. Vandamme P. (2008). Taxonomy of the family Campylobacteraceae in Campylobacter, 3rd Edn, eds NachamkinI.BlaserM. J.SzymanskiC. M. (Washington, DC: American Society of Microbiology), 3–25.

34

Debruyne L. On S. L. De Brandt E. Vandamme P. (2009). Novel Campylobacter lari-like bacteria from humans and molluscs: description of Campylobacter peloridis sp. nov., Campylobacter lari subsp. concheus subsp. nov. and Campylobacter lari subsp. lari subsp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol.59, 1126–1132. 10.1099/ijs.0.000851-0

35

Deshpande N. P. Wilkins M. R. Castano-Rodriguez N. Bainbridge E. Sodhi N. Riordan S. M. et al . (2016). Campylobacter concisus pathotypes induce distinct global responses in intestinal epithelial cells. Sci Rep6:34288. 10.1038/srep34288

36

Dhawan V. K. Ulmer D. D. Rao B. See R. C. Nachum R. (1986). Campylobacter jejuni septicemia-epidemiology, clinical features and outcome. West. J. Med.144:324.

37

Di Pilato V. Freschi G. Ringressi M. N. Pallecchi L. Rossolini G. M. Bechi P. (2016). The esophageal microbiota in health and disease. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci.1381, 21–33. 10.1111/nyas.13127

38

Dibart S. Skobe Z. Snapp K. Socransky S. Smith C. Kent R. (1998). Identification of bacterial species on or in crevicular epithelial cells from healthy and periodontally diseased patients using DNA-DNA hybridization. Mol. Oral Microbiol.13, 30–35. 10.1111/j.1399-302X.1998.tb00747.x

39

D'Incà R. Annese V. Di Leo V. Latiano A. Quaino V. Abazia C. et al . (2006). Increased intestinal permeability and NOD2 variants in familial and sporadic Crohn's disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther.23, 1455–1461. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02916.x

40

Dongari-Bagtzoglou A. Ebersole J. (1996). Production of inflammatory mediators and cytokines by human gingival fibroblasts following bacterial challenge. J. Periodont. Res.31, 90–98. 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1996.tb00469.x

41

Duerden B. Bennet K. Faulkner J. (1982). Isolation of Bacteroides ureolyticus (B corrodens) from clinical infections. J. Clin. Pathol.35, 309–312. 10.1136/jcp.35.3.309

42

Duerden B. Eley A. Goodwin L. Magee J. Hindmarch J. Bennett K. (1989). A comparison of Bacteroides ureolyticus isolates from different clinical sources. J. Med. Microbiol.29, 63–73. 10.1099/00222615-29-1-63

43

Duerden B. Goodwin L. O'neil T. (1987). Identification of Bacteroides species from adult periodontal disease. J. Med. Microbiol.24, 133–137. 10.1099/00222615-24-2-133

44

Eaves-Pyles T. Murthy K. Liaudet L. Virág L. Ross G. Soriano F. G. et al . (2001). Flagellin, a novel mediator of Salmonella-induced epithelial activation and systemic inflammation: IκBα degradation, induction of nitric oxide synthase, induction of proinflammatory mediators, and cardiovascular dysfunction. J. Immunol.166, 1248–1260. 10.4049/jimmunol.166.2.1248

45

Edmonds P. Patton C. Barrett T. Morris G. Steigerwalt A. Brenner D. (1985). Biochemical and genetic characteristics of atypical Campylobacter fetus subsp. fetus strains isolated from humans in the United States. J. Clin. Microbiol.21, 936–940.

46

Edmonds P. Patton C. Griffin P. Barrett T. Schmid G. Baker C. et al . (1987). Campylobacter hyointestinalis associated with human gastrointestinal disease in the United States. J. Clin. Microbiol.25, 685–691.

47

Engberg J. Bang D. D. Aabenhus R. Aarestrup F. M. Fussing V. Gerner-Smidt P. (2005). Campylobacter concisus: an evaluation of certain phenotypic and genotypic characteristics. Clin. Microbiol. Infect.11, 288–295. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2005.01111.x

48

Etoh Y. Dewhirst F. Paster B. Yamamoto A. Goto N. (1993). Campylobacter showae sp. nov., isolated from the human oral cavity. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol.43, 631–639. 10.1099/00207713-43-4-631

49

Fasano A. Baudry B. Pumplin D. W. Wasserman S. S. Tall B. D. Ketley J. M. et al . (1991). Vibrio cholerae produces a second enterotoxin, which affects intestinal tight junctions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.88, 5242–5246. 10.1073/pnas.88.12.5242

50

Fennell C. Rompalo A. Totten P. Bruch K. Flores B. Stamm W. (1986). Isolation of “Campylobacter hyointestinalis” from a human. J. Clin. Microbiol.24, 146–148.

51

Figura N. Guglielmetti P. Zanchi A. Partini N. Armellini D. Bayeli P. F. et al . (1993). Two cases of Campylobacter mucosalis enteritis in children. J. Clin. Microbiol.31, 727–728.

52

Fox E. M. Raftery M. Goodchild A. Mendz G. L. (2007). Campylobacter jejuni response to ox-bile stress. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol.49, 165–172. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2006.00190.x

53

Francioli P. Herzstein J. Grob J.-P. Vallotton J.-J. Mombelli G. Glauser M. P. (1985). Campylobacter fetus subspecies fetus bacteremia. Arch. Intern. Med.145, 289–292. 10.1001/archinte.1985.00360020125020

54

Fujihara N. Takakura S. Saito T. Iinuma Y. Ichiyama S. (2006). A case of perinatal sepsis by Campylobacter fetus subsp. fetus infection successfully treated with carbapenem–case report and literature review. J. Infect.53, e199–e202. 10.1016/j.jinf.2006.01.009

55

Galanis E. (2007). Campylobacter and bacterial gastroenteritis. CMAJ177, 570–571. 10.1503/cmaj.070660

56