Abstract

Early weaning of piglets is an important strategy for improving the production efficiency of sows in modern intensive farming systems. However, due to multiple stressors such as physiological, environmental and social challenges, postweaning syndrome in piglets often occurs during early weaning period, and postweaning diarrhea (PWD) is a serious threat to piglet health, resulting in high mortality. Early weaning disrupts the intestinal barrier function of piglets, disturbs the homeostasis of gut microbiota, and destroys the intestinal chemical, mechanical and immunological barriers, which is one of the main causes of PWD in piglets. The traditional method of preventing PWD is to supplement piglet diet with antibiotics. However, the long-term overuse of antibiotics led to bacterial resistance, and antibiotics residues in animal products, threatening human health while causing dysbiosis of gut microbiota and superinfection of piglets. Antibiotic supplementation in livestock diets is prohibited in many countries and regions. Regarding this context, finding antibiotic alternatives to maintain piglet health at the critical weaning period becomes a real emergency. More and more studies showed that probiotics can prevent and treat PWD by regulating the intestinal barriers in recent years. Here, we review the research status of PWD-preventing and treating probiotics and discuss its potential mechanisms from the perspective of intestinal barriers (the intestinal microbial barrier, the intestinal chemical barrier, the intestinal mechanical barrier and the intestinal immunological barrier) in piglets.

Introduction

As a critical period, the health of piglets during the weaning period determines later growth performance (Gresse et al., 2017). In the modern porcine industry, early weaning generally occurs at 3-4 weeks of age to improve economic efficiency (Sutherland et al., 2014). Nevertheless, the digestive and immune systems of piglets are immature at this stage. Study has shown that the activities of piglets’ digestive enzymes, such as pepsin, trypsin, chymotrypsin and amylase, significantly decreased within 1 week of early weaning, making feed difficult to digest (Jensen et al., 1997). Simultaneously, the change of feed from liquid milk to solid feed results in the destruction of intestinal physical barrier, including the destruction of tight junctions (TJs), reducing mucin production, and increasing of gut permeability, etc. (Le Dividich and Seve, 2000; Hu et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2016a). Additionally, early weaning causes the loss of microbial diversity and dysbiosis of gut microbiota, and further increases the risk of gastrointestinal diseases of piglets (Guevarra et al., 2018). Studies have reported that weaning transition reduces the relative abundance of Lactobacillus (the primary gut microbiota in piglet shaped by the sows’ milk), increases the relative abundance of Clostridium spp., Prevotella spp., Proteobacteriaceae, and E. coli (Konstantinov et al., 2006). Early weaned piglets are susceptible to enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) infection and causing PWD, which kills up to 50% of piglets worldwide each year (Gresse et al., 2017).

In modern farming, antibiotics are heavily used to prevent and treat pig diseases in order to reduce economic losses. (Li, 2017). The long-term overuse of antibiotics is a screening process of bacteria and accelerates the spread of drug-resistant bacteria in animal gastrointestinal tract (Pamer, 2016). Such as, ETEC shows significant high resistance in porcine intestinal tract (Laird et al., 2021). While the gut microbial ecosystem is normally resilient, the composition of gut microbiota is relatively simple in the newborn mammals, resulting in a low resilience of the gut microbiota. The use of antibiotics permanently changes the structure of the microbial community and interferes with the intestinal homeostasis of newborn mammals (Sommer et al., 2017; Zong et al., 2020). Furthermore, studies have shown that antibiotics promote intestinal inflammation (Zeng et al., 2017), and antibiotics are associated with the decrease of microbiota diversity, exacerbating the vicious circle of PWD (Perez-Cobas et al., 2013). Antibiotics can also remain in the bodies of livestock, ultimately affecting human health. Therefore, antibiotics have been forbidden to be fed on livestock in many countries and regions. As the world’s largest pig farming country, since 1 July 2020, China have started to ban the feed production enterprises to product commercial feed containing growth-promoting drugs feed additives. Hence, there is an urgent need for developing nonantibiotic alternative to restore microbial balance and control PWD of piglets. The effects of probiotics, an alternative to antibiotics, on treating PWD are widely documented in recent years (Table 1). The most frequently used microorganisms are Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Enterococcus, Bacillus and yeasts from the genus Saccharomyces (Liao and Nyachoti, 2017). A comprehensive understanding of the interactions between probiotics and intestinal barrier of piglets during PWD will help develop new probiotics interventions strategies that can enhance piglets’ growth performance and protect piglets from PWD.

Table 1

| Microorganism Category | Microorganism Name | Treatment | Host Health Influence | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lactic acid bacteria | Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus casei, Bifidobacterium thermophilum and Enterococcus faecium | Piglets weaned at 28 d of age were fed the basal diet mixed the probiotics (0.25 × 108 CFU/g for each strain) for 25 days, and orally administered with ETEC F18+ (2 × 109 CFU/g) on day 13 postweaning | Decreasing serum TNF-α; increasing jejunal villus height, and especially villus height-to-crypt depth ratio in piglets | (Sun et al., 2021b) |

| Lactobacillus delbrueckii | The piglets were orally administrated with Lactobacillus delbrueckii (50 × 108 CFU/mL) at amounts of 1, 2, 3, and 4 mL per animal at 1, 3, 7, and 14 d of age | Increasing the height of intestinal villi of piglets; promoting the expression of intestinal TJs proteins, and reducing the incidence of diarrhea by more than 50% | (Li et al., 2019b) | |

| Enterococcus faecalis | Piglets weaned at 26 d of age were fed basal diet supplemented with Enterococcus faecalis (2.5 ×109 CFU/kg) for 28 days | Enterococcus faecalis and neomycin sulfate decreased diarrhea index and improve growth performance, Enterococcus faecalis increased Lactobacillus in feces | (Hu et al., 2015) | |

| Lactobacillus plantarum | Piglets (4 d of age) were orally administrated with Lactobacillus plantarum (5 × 1010 CFU/kg) for 15 days and then orally administrated with ETEC F4 (1 × 108 CFU per pig) | Improving performance and effectively preventing the diarrhea; improving function of the intestinal barrier by protecting intestinal morphology and intestinal permeability and the expression of genes for TJs proteins | (Yang et al., 2014) | |

| Lactobacillus zeae and Lactobacillus casei | Piglets weaned at 28 d of age were fed corn-soybean meal mixed feed fermented by Lactobacillus zeae and Lactobacillus casei for 3 days, and then orally challenged with 1 mL Salmonella (1 × 106 CFU/mL) | Decreasing pro-inflammatory cytokine expression and alleviating Salmonella infection | (Yin et al., 2014) | |

| Yeast | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Piglets weaned at 14 d b of age were fed basal diet supplemented with 3.0 g kg–1 live yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (4.3 × 109 CFU/g) for 21days | Decreasing numbers of Escherichia coli in the ileum and cecum contents; increasing serum SOD activity and jejunum mucosal SIgA secretions | (Zhu et al., 2017a) |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Piglets weaned at 28 d of age were fed basal diet supplemented with 5 g/kg live yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae for 14 days, orally challenged with ETEC F4 (1.5 × 1011 CFU/piglet) after weaning (d 29) | Significantly lower daily diarrhea scores, duration of diarrhea, and shedding of pathogenic ETEC bacteria in feces and increasing IgA levels in the serum of piglets | (Trckova et al., 2014) | |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Piglets weaned at 21 d of age were fed basal diet supplemented with Saccharomyces cerevisiae fermentation products for 8 days and then orally challenged with ETEC F4 | Saccharomyces cerevisiae fermentation products and carbadox increased average daily feed intake, Saccharomyces cerevisiae fermentation products decreased the ileal mucosa adherent Escherichia coli ETEC F4 | (Kiarie et al., 2011) | |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae var. boulardii | Piglets weaned at 26 d of age were fed basal diet supplemented with 200 g/t live Saccharomyces cerevisiae var. boulardii for 16 days, and then dosed via indwelling jugular catheters with Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (25 μg/kg of BW) | ADG increased by 39.9% and LPS-induced piglet mortality was reduced 20% | (Collier et al., 2011) | |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Piglets weaned at 21 d of age were fed Saccharomyces cerevisiae fermentation products for 14 days, and then orally administrated with Salmonella (1 × 109 CFU) | Increasing compensatory body weight gains after Salmonella infection and increasing Salmonella shedding in feces | (Price et al., 2010) | |

| Bacillus | Bacillus subtilis KN-42 | Piglets weaned at 28 d of age were fed basal diet supplemented with 20 × 109 CFU/kg feed of B. subtilis KN-42 for 28 days | Bacillus subtilis KN-42 increased average daily gain (ADG) and feed efficiency of piglets, Bacillus subtilis KN-42 and neomycin sulfate decreased diarrhea index and the relative number of Escherichia coli | (Hu et al., 2014) |

| Clostridium butyricum | Piglets (7.09 ± 0.2 kg) were fed basal diet supplemented with Clostridium butyricum (5 × 105 CFU/g) for 15 days and then orally administered with ETEC F4 (1 × 109 CFU/g) | Alleviating intestinal villi injury caused by ETEC F4 challenge | (Li et al., 2021) | |

| Three types of mixed bacteria | Enterococcus faecium, Bacillus subtilis, Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Lactobacillus paracasei | Piglet weaned at 28 d of age were fed the basal diet mixed the probiotics (>1 × 108 CFU/g for each strain) for 21days | Increasing fecal acetic acid and propionic acid; increasing growth performance and significantly reducing PWD | (Lu et al., 2018) |

Effects of probiotics on treating PWD of piglet.

Intestinal Barriers of Piglets

The intestinal barriers of piglets are consisted of microbial barrier, mucosal barrier and immunological barrier. The intestinal barriers play an important role in maintaining the homeostasis of the gut internal environment (Maynard et al., 2012). As a critical line of defense, intestinal barrier prevents the pathogenic antigens, toxins and pathogenic microorganisms from invading the internal environment of the body (Baumgart and Dignass, 2002).

Newborn piglets develop a diverse and complex microbial community in the gastrointestinal tract by milk intake and exposure to the external environment (Blaut and Clavel, 2007). The dynamic balance, formed by interdependence and mutual restraint among different gut microbiota, provides the first barrier for gut. In the face of the external threats, the gut microbiota works together to counteract its own disadvantages (Hooper and Macpherson, 2010; Shanahan, 2010). There are three widely accepted mechanisms of gut microbial barrier function: 1) occupying the binding site and settlement space; 2) nutrition competition; 3) promoting the improvement of intestinal function (regulating the secretion of mucus and the development of intestinal immune system) (Buffie and Pamer, 2013; Kamada et al., 2013).

The mucosal barrier, the second intestinal barrier in piglets, consists of chemical and mechanical barriers (Sperandio et al., 2015). Chemical barrier is composed of the mucus secreted by the intestinal mucosa epithelium, digestive liquid, and bacteriostatic substances produced by normal parasitic bacteria in the intestinal lumen. Paneth cells and goblet cells contribute to the natural immune defense that supports epithelial barrier function (McCracken and Lorenz, 2001). Paneth cells produce antimicrobial agents such as defensins and lysozyme, and they can damage bacterial cell walls or membranes to inhibit or kill pathogenic bacteria and maintain gut mucosal homeostasis (Salzman et al., 2007; Bevins and Salzman, 2011; Salzman, 2011; Sun et al., 2021a). Additionally, the mucin, produced by goblet cells, forms a protective layer to prevent pathogenic microbes from binding to intestinal epithelial cells (Desai et al., 2016). The gut microbiota and the host immune cells can ingeniously modulate these barriers to avoid unnecessary immune responses to gut commensal microbes by spatially segregating the gut microbiota and the host immunity (Okumura and Takeda, 2018). The structure of mechanical barrier is based on intact intestinal epithelial cells (ICEs) and TJs between epithelial cells. ICEs and TJs can effectively prevent bacteria and endotoxins from entering the blood from intestine (Wang et al., 2014; Balda and Matter, 2016; Zong et al., 2021).

Early weaning is a challenge to the immature gut immune system as it must adapt to gut microbial colonization and feed antigens. In the early weaning period, the innate immune system defenses responsible for barrier function are more mature compared to the adaptive immune system. Therefore, the early weaning piglet is more reliant on innate immunity (Humphrey et al., 2019). The intestinal immune system is stimulated to maintain homeostasis in the intestinal epithelium by secreting immunoglobulins, interleukins and interferons. At approximately 6 weeks of age, piglets have stable numbers of lymphocytes and mature secondary lymphoid organs, such as Peyer’s patches (PPs) in the gut (Moeser et al., 2017). PPs are covered by a specialized follicle associated epithelium containing M cells, which is a pathway for antigens to enter the lamina propria. The lamina propria contains a variety of immune cells, mainly including B cells, macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs) and T cells (Allaire et al., 2019). The perception of microbes by epithelial cells, DCs and macrophages is mediated by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) such as toll-like receptors (TLRs) (Xiao et al., 2017). The T cells closely related to probiotics in the lamina propria are T helper (Th) and regulatory T (TReg) cells. The activation of PRRs often induces microbial killing pathways and activates T helper 1 (Th1) and T helper 17 (Th17) cells and adaptive immune cells (Liew, 2002).

Probiotics Relieve PWD by Regulating the Intestinal Microbial Barrier

Probiotics can improve the richness of gut microbiota and shape the gut microbiota oriented by beneficial bacteria to resist infection by pathogenic microorganisms (Tang et al., 2020). Study has shown that supplementation with S. cerevisiae and Bacillus licheniformis reduced diarrhea incidence and the relative abundance of intestinal E. coli, and increased the relative abundance of Lactobacillus in ETEC-challenged piglets (Pan et al., 2017). Several recent studies suggested that dietary supplementation of lactic acid bacteria (Lactobacillus johnsonii, Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus delbrueckii and Enterococcus faecalis) increased the relative abundance of Lactobacillus or Bifidobacterium spp., decreased E. coli and enhanced production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) in the gut of weaning piglets (Wang et al., 2019a; Wang et al., 2019b; Xin et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021). This probiotic-mediated increase of SCFAs in the gut contributes to defend against pathogenic microbial invasion by downregulating the pH of the gastrointestinal tract, and enhances gut barrier function by providing energy to intestinal epithelial cells (Guilloteau et al., 2010; D'Souza et al., 2017). In addition, intestinal inflammation caused by PWD often leads to increased oxygen in the piglet intestine, which provides proliferation conditions for the facultative anaerobe, such as Escherichia coli (E. coli) (Wei et al., 2017). The increase of E. coli usually exacerbates PWD and creates a vicious cycle. Some aerobic probiotics (such as Bacillus subtilis) or facultative anaerobic probiotics (such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae) rapidly consume oxygen upon entering into the intestine, creating an anaerobic environment that inhibits the growth of aerobic pathogens in the gut (Hillman et al., 1994; Han et al., 2012).

Piglets are sensitive to pathogen colonization of the intestinal tract during weaning (Dubreuil, 2017). ETEC causes PWD in piglets mainly through intestinal mucosa adhesion, colonization and toxin production. Probiotics can exclude pathogens from attaching to mucosal surfaces by competition for shared binding sites and steric hindrance of protein adhesins of pathogenic bacteria (Nair et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2018). Wang et al. (2018) suggested that Lactobacillus plantarum inhibited the adhesion of ETEC to IPEC-J2 cells in a dose-dependent manner. Collado et al. (2007) found that Bifidobacterium lactis and Lactobacillus rhamnosus inhibited the adhesion of Salmonella, Clostridium and E. coli to pig intestinal mucus. Saccharomyces cerevisiae var. boulardii and β-galactomannan also inhibited in vitro adhesion of ETEC on cell surface of porcine intestinal IPI-2I cells (Badia et al., 2012a). In addition to inhibiting the adhesion of pathogens to the intestinal mucosa through competitive exclusion, probiotics also can secrete antimicrobial substances, such as bacteriocins, organic acids and hydrogen peroxide (Dicks and Botes, 2010; O'Shea et al., 2012; Knaus et al., 2017). The antimicrobial compounds exert direct antimicrobial effect against competing entero-pathogens and prevent the pathogenic colonization in the gastrointestinal tract of piglets (van Zyl et al., 2020). Moreover, Bifidobacterium was reported to bind and neutralize lipopolysaccharides (LPS) or Vero cytotoxin from E. coli (Kim et al., 2001; Park et al., 2007).

Therefore, the regulatory effects of probiotics to alleviate PWD of piglet through the intestinal microbial barrier mainly include the following three aspects: 1) shaping the gut microbiota oriented by beneficial bacteria; 2) competitive exclusion of pathogen; 3) producing antimicrobial substances. From the research status on the regulatory effect of probiotics on the intestinal microbial barrier of postweaning piglets, probiotics appear to be more effective in preventing PWD than in treating PWD. Screening for probiotics (such as Lactobacillus) that can stably colonize the piglet’s gut, efficiently produce antibacterial substances and competitively exclude of pathogen to prevent PWD may be an effective strategy. In addition, supplementing probiotics to accelerate the maturation of gut microbiota or to shape a PWD-preventing gut microbiota in weaned piglets are worthy of further study.

Probiotics Relieve PWD by Regulating the Intestinal Chemical and Mechanical Barrier

The mucus layer in the intestine acts as the gatekeeper, separating the luminal microbiota from the epithelial cells (Birchenough et al., 2015; Zong et al., 2019a). Carvalho et al. (2012) reported that ETEC degraded MUC2 by secreting a serine protease (Eat A), which enabled bacteria to penetrate the mucus layer to reach the epithelium and triggered an inflammatory response (Kumar et al., 2014). Zhang et al., (Zhang et al., 2017) suggested that Bacillus licheniformis-b and Bacillus subtilis up-regulated the expression of Atoh1 in the ileum of weaned piglets, which increased goblet cells number and MUC2 to protect the mucus barrier from the degradation of ETEC. Lactobacillus reuteri also enhanced intestinal mucosal barrier with the increase of goblet cells and antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) expressions of MUC2, Lyz1, and pBD1 of piglets. Liu et al. (2017) reported that Lactobacillus reuteri increased the expression of porcine β-Defensin2 (PBD2), pBD3, pBD114, pBD129 in the IPEC-J2 cells and colon of piglets. Similarly, Fu et al. (2021) reported that piglets treated by Clostridium butyricum or Bacillus licheniformis up-regulated the gene expression of pBDs and PR-39 in jejunum. In another study, the bacterial secretory circular peptide and gassericin A of Lactobacillus gasseri LA39 and Lactobacillus frumenti can combine with Keratin 19 on the plasma membrane of intestinal epithelial cells to promote the fluid absorption and secretion reduction, thereby reducing the diarrhea of piglets (Hu et al., 2018b).

Many studies reported that probiotics relieved PWD by modulating the gut mechanical barrier. Yang et al. (2014) suggested that Lactobacillus plantarum alleviated the increase of urine lactic acid and plasma concentration and the decrease of ZO-1 and Occludin mRNA and protein in the jejunum of piglets caused by ETEC. Hu et al. (2018a) demonstrated that oral administration of Lactobacillus frumenti can significantly improve the intestinal integrity and up-regulate the intestinal TJs proteins (ZO-1, Occludin, and Claudin-1) of piglets. Similarly, Clostridium butyricum, Bacillus licheniformis and Lactobacillus reuteri compete with potential pathogens for intestinal epithelial binding sites to promote TJs proteins expression (Li et al., 2019b; Zhao et al., 2019; Zong et al., 2019b). Study showed that Lactobacillus plantarum reversed EIEC infection resulting in a centripetal retraction of the peri-junctional actin filaments with separation of actins from the apical cellular borders and EIEC-induced rearrangements of Claudin-1, Occludin, JAM-1 and ZO-1 proteins in Caco-2 (Qin et al., 2009).

In summary, the protection of mucosal barrier in piglets by probiotics may be achieved mainly through stimulating secretion of mucin and antimicrobial peptides, promoting intestinal fluid absorption and reducing fluid secretion, and upregulating the expression of intestinal TJs protein. From the research status on the regulatory effects of probiotics on the intestinal chemical and mechanical barriers of postweaning piglets, probiotics play an important role in both prevention and treatment of PWD. On the one hand, probiotics promote the secretion of mucin and antimicrobial peptides and up-regulating the expression of TJs protein to prevent PWD. On the other hand, it can alleviate the damage of the intestinal chemical and mechanical barriers caused by PWD. However, the specific regulatory mechanism of probiotics on the intestinal chemical and mechanical barriers in postweaning piglets still needs further research.

Probiotics Relieve PWD by Regulating the Intestinal Immunological Barrier

Piglets are exposed to complex microbiota after weaning from environment. The intestinal immune system needs to rapidly identify harmful microorganisms and dietary antigens, and trigger the correct mucosal immune response. However, the intestinal mucosal immune system of piglets does not mature until about two weeks after early weaning (Butler and Wertz, 2012). In recent years, many studies have reported the effect of probiotics on the gut immunity of weaned piglets (Table 2). Probiotics (such as Lactobacillus, Bacillus, yeast, etc.) and their metabolites (such as organic acids, mannan oligosaccharide and β-glucan of yeast cell wall, etc.) seem to act as immune activators, which can trigger the proliferation and differentiation of T lymphocytes and B lymphocytes, and promoting the secretion of a series of cytokines and generating a series of immune responses (Sharma et al., 2010).

Table 2

| Microorganism Category | Microorganism Name | Treatment | Host Health Influence | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lactic acid bacteria | Lactobacillus salivarius | Porcine intestinal epithelial were stimulated with Lactobacillus salivarius (5 × 107 cells/mL) | Improving IFN-β, IFN-λ and antiviral factors expression in PIE cells | (Indo et al., 2021) |

| Lactobacillus delbrueckii | The piglets were orally administrated with Lactobacillus delbrueckii (50 × 108 CFU/mL) at amounts of 1, 2, 3, and 4 mL per animal at 1, 3, 7, and 14 d of age | Increasing the concentration of IgG in serum; promoting the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-4 and IL-10, and reducing the content of pro-inflammatory factor IL-1β | (Li et al., 2019a) | |

| Lactobacillus frumenti | Piglets received a PBS suspension (2 mL, 108 CFU/mL) containing the Lactobacillus frumenti by oral gavage once a day during the period of 6–20 days of age prior to early weaning | The level of serum IgG, intestinal sIgA, and IFN-γ were significantly increased | (Hu et al., 2018a) | |

| Lactobacillus reuteri | Intestinal porcine epithelial cells were treated with ETEC and Lactobacillus reuteri | Inhibited ETEC-induced expression of pro-inflammatory transcripts IL-6 and TNF-α and protein IL-6 and increased the level of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 | (Wang et al., 2016b) | |

| Lactobacillus plantarum | Piglets weaned at 25 d of age were fed basal diet supplemented with Lactobacillus plantarum (2 × 1010 CFU/day) for 7 days, and then orally challenged with ETEC F4 (109 CFU/mL) | The level of serum TNF-α was significantly increased | (Guerra-Ordaz et al., 2014) | |

| Yeast | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Piglets (20 d of age) were fed with Saccharomyces cerevisiae (2 × 108 CFU/mL) for 10 days (10 mL/day) | Increasing the numbers of plasmocyte and lymphoid nodule; promoting the development of PPs and germinal center | (Zhaxi et al., 2020) |

| Brewery hydrolyzed yeast | Piglets weaned at 25 d of age were fed basal diet supplemented with 2 g/kg brewery hydrolyzed yeast for 28 days | Increased IgG and IgM antibodies in serum-binding KLH, and increased SRBC agglutination titers | (Molist et al., 2014) | |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae var. boulardii and β-galactomannan | Porcine small intestine epithelial cell was challenged in vitro with Escherichia coli F4 and then treated with Saccharomyces cerevisiae var. boulardii and β-galactomannan | Decreased the mRNA ETEC-induced gene expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-6, GM-CSF and chemokines CCL2, CCL20 and CXCL8 on intestinal IPI-2I | (Badia et al., 2012b) | |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Porcine small intestine epithelial cell was challenged in vitro with Escherichia coli F4 and then treated with Saccharomyces cerevisiaee | Inhibited the ETEC-induced expression of pro-inflammatory transcripts IL-6, IL-8, CCL20, CXCL2, and CXCL10, as well as proteins IL-6 and IL-8 | (Zanello et al., 2011) | |

| Bacillus | Clostridium butyricum | Piglets (7.09 ± 0.2 kg) were fed basal diet supplemented with Clostridium butyricum (5 × 105 CFU/g) for 15 days and then orally administered with ETEC F4 (1 × 109 CFU/g) | Including myeloid differentiation factor, toll-interacting protein, and B cell CLL/lymphoma 3, in the intestines of ETEC F4-challenged piglets | (Li et al., 2021) |

| Bacillus cereus var. Toyoi | Piglets (14 d of age) were fed basal diet supplemented with Bacillus cereus var. Toyo (6.5 × 105 CFU/g) and then orally administrated with Salmonella (3 × 109 CFU per pig) on d 29 | Reduced frequencies of CD8+ γδ T cells in the peripheral blood and the jejunal epithelium | (Scharek-Tedin et al., 2013) | |

| Three types of mixed bacteria | Lactobacillus plantarum, Bacillus subtilis and Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Weaning pigs basal diet supplemented with 15% fermented soybean meal | The level of serum IgG, IgM and IgA were significantly increased, and autophagy factor LC3B in piglets showed a downward trend | (Zhu et al., 2017b) |

Effects of probiotics on immunity of piglets.

When weaned piglets are not infected by pathogens such as E. coli, the supplement of probiotics actually activates the immune system of piglets to develop towards a more stable and less vulnerable direction. The supplement of probiotics, to a large extent, helps piglets to establish intestinal immunity response against the invasion of pathogens after weaning without causing severe inflammatory responses. Van Baarlen et al., (van Baarlen et al., 2011) reported that lipoteichoic acid, a cell surface molecule of Lactobacillus plantarum, regulated the activation of extracellular signaling kinase through the TLR signaling pathway, in turn activating NF-κB to regulate the release of Th1 cytokines and subsequent Treg and Th1 development. Lactobacillus rhamnosus can regulate the proliferation of T-lymphocytes and increase the number of CD3+ CD4+ T-lymphocytes in the intestine of early weaning piglets (Shonyela et al., 2020). In addition, probiotics also play a role in the stimulation of antibodies in the gut, particularly slgA, which can inhibit pathogen adherence to IECs. Zhu et al. (2017a) suggested that weaning pigs diet supplemented with Saccharomyces cerevisiae increase the content of slgA in intestinal mucosa.

On the other hand, when weaned piglets are infected with pathogens, these pathogen-associated molecular patterns are well recognized by the cells of the immune system that reside within the lamina propria, and their activation results in the release of pro-inflammatory mediators and inflammatory responses (Humphrey et al., 2019). Probiotics can enhance the proliferation and differentiation of intestinal immune cells, and inhibit the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and promote the expression of anti-inflammatory cytokines, thus protecting the intestinal tract from damage caused by pathogen-related inflammation. Zanello et al. (2011) reported that Saccharomyces cerevisiae inhibited the ETEC-induced expression of pro-inflammatory transcripts IL-6, IL-8, CCL20, CXCL2, and CXCL10. Probiotics tend to increase the plasma level of IL-2, and inhibit pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1 and IL-18) expression and promote anti-inflammatory cytokines (IFN-γ, IL-4 and IL-10) expression (Ngo and Vo, 2019; Xiang et al., 2020). Wang, et al., (Wang et al., 2016b) suggested Lactobacillus reuteri inhibited ETEC-induced the expression of pro-inflammatory transcripts IL-6 and TNF-α and increased the level of the anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-10. Zhu et al. (2014) found that the amelioration of PWD in piglets by Lactobacillus rhamnosus is associated with the generation of lamina propria CD3+CD4+CD8−T cells and the expansion of PPs CD3+CD4−CD8− and CD3−CD4−CD8+ cells. In addition, Virdi et al. (2019) suggested that a single-gene-encoded monomeric immunoglobulin A(IgA)-like antibody, mVHH-IgA, secreted from Pichia pastoris, prevent the colonization of F4 fimbriae-bearing enterotoxigenic E. coli in small intestine of piglets. Lactobacillus plantarum was also reported to partially inhibit F4-triggered expression of inflammatory cytokines IL-8 and TNF-α. The induction of negative regulators of TLRs by Lactobacillus plantarum in IPEC-J2 may be important for the inhibition of inflammatory cytokines and may be mediated through the NF-κB and MAPK pathways (Wu et al., 2016).

Overall, in terms of intestinal immunological barrier, probiotics prevent or mitigate PWD by triggering a range of immunological defense mechanisms, including promoting the production of slgA and inflammatory cytokines, and promoting the differentiation of intestinal immune cells. From the research status on the regulatory effects of probiotics on the intestinal immunological barrier of postweaning piglets, probiotics also play an important role in both prevention and treatment of PWD. Probiotics and their metabolites act as immune activators to activate the immune system of postweaning piglets and increase the body’s resistance to pathogenic bacteria, thereby preventing PWD. Additionally, probiotics protect the intestinal tract from damage caused by pathogen-related inflammation. In production, we recommend selecting appropriate probiotics as immune activators to prevent PWD, which may have better economic effects.

Regulation Mechanism of Probiotics on Intestinal Barriers of Postweaning Piglets

The surface components of probiotics, such as flagella, pili, surface layer proteins (SLPs), capsular polysaccharide (CPS), lipoteichoic acid, and lipopolysaccharide, constitute microbial-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs). They can specifically bind to pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) such as NOD-like receptors (NLRs) and TLRs (Lebeer et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2020). The underlying mechanisms have been proposed for the probiotic (such as Lactobacillus rhamnosus and Lactobacillus plantarum) effect on epithelial barrier modulation, involving protein kinase C (PKC)- and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)-dependent pathways, and inhibition of cytokine-induced epithelial cell apoptosis and damage through a phosphoinositide 3-kinase–AKT-dependent pathway. These and similar studies have provided insights into the mechanisms by which probiotics may affect epithelial barrier function at the molecular level (Seth et al., 2008; Anderson et al., 2010; Bron et al., 2012). Lactobacillus plantarum also improve epithelial barrier function by inhibiting the reduction of TJs proteins, and reducing the expression of proinflammatory cytokines induced by ETEC F4, possibly through modulation of TLRs, NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathway (Wu et al., 2016). Lactobacillus acidophilus was reported to promote Th1 cell development by inducing the production of Th1 cytokines via an IFN-STAT3-NF-κB signaling axis (van Baarlen et al., 2011). Fu et al. (2021) reported that Clostridium butyricum improved intestinal chemical and mechanical barriers (up-regulating the gene expression of pBDs, JTs protein and mucin) of weaning piglets by the TLR-2-MyD88-NF-κB signaling. Prebiotics can promote the proliferation of SCFAs-producing microorganisms in the hindgut of weaning piglets, and then reduce the expression of intestinal proinflammatory factors through the MyD88-NF-κB signaling pathway to improve the intestinal immunological barrier (Tian et al., 2022). In addition, metabolites produced by probiotics, such as secreted proteins, indole and SCFAs, also protect the intestinal barriers. Butyrate secreted by Clostridium butyricum can promote the expression of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF-1α) to upregulate the expression of its targeted downstream intestinal JTs, mucin and antimicrobial peptides, and promote intestinal IL-22 secretion, thereby improving the gut barrier and immune function (Pral et al., 2021).The indole-3-lactic acid produced by Bifidobacterium infantis and Lactobacillus reuteri activates the aryl hydrogen receptors (AhRs) of the gut epithelium by increasing their nuclear localization and up-regulating the protein expression of CYP1A1. The activation of AhRs then leads to lL-22 transcription, which can further increase the expression of antimicrobial peptides (Ehrlich et al., 2018; Hou et al., 2021). The soluble proteins P40 and p75 isolated from Lactobacillus rhamnosus can activate EGFR and then up-regulate the expression of an A proliferation-inducing ligand (APRIL) in the epithelium, thus stimulating the secretion of lgA by B cells. Besides, P40 and p75 can activate EGFR–PIK3–Akt signaling pathway to maintain gut homeostasis (Wang et al., 2017).

In summary, the surface molecules and metabolites of probiotics may modulate postweaning piglets’ gut barrier function via multiple signaling pathways. Direct use of the surface components and metabolites of probiotics may be considered to prevent or treat PWD instead of probiotics during weaning of piglets.

Conclusion and Future Perspectives

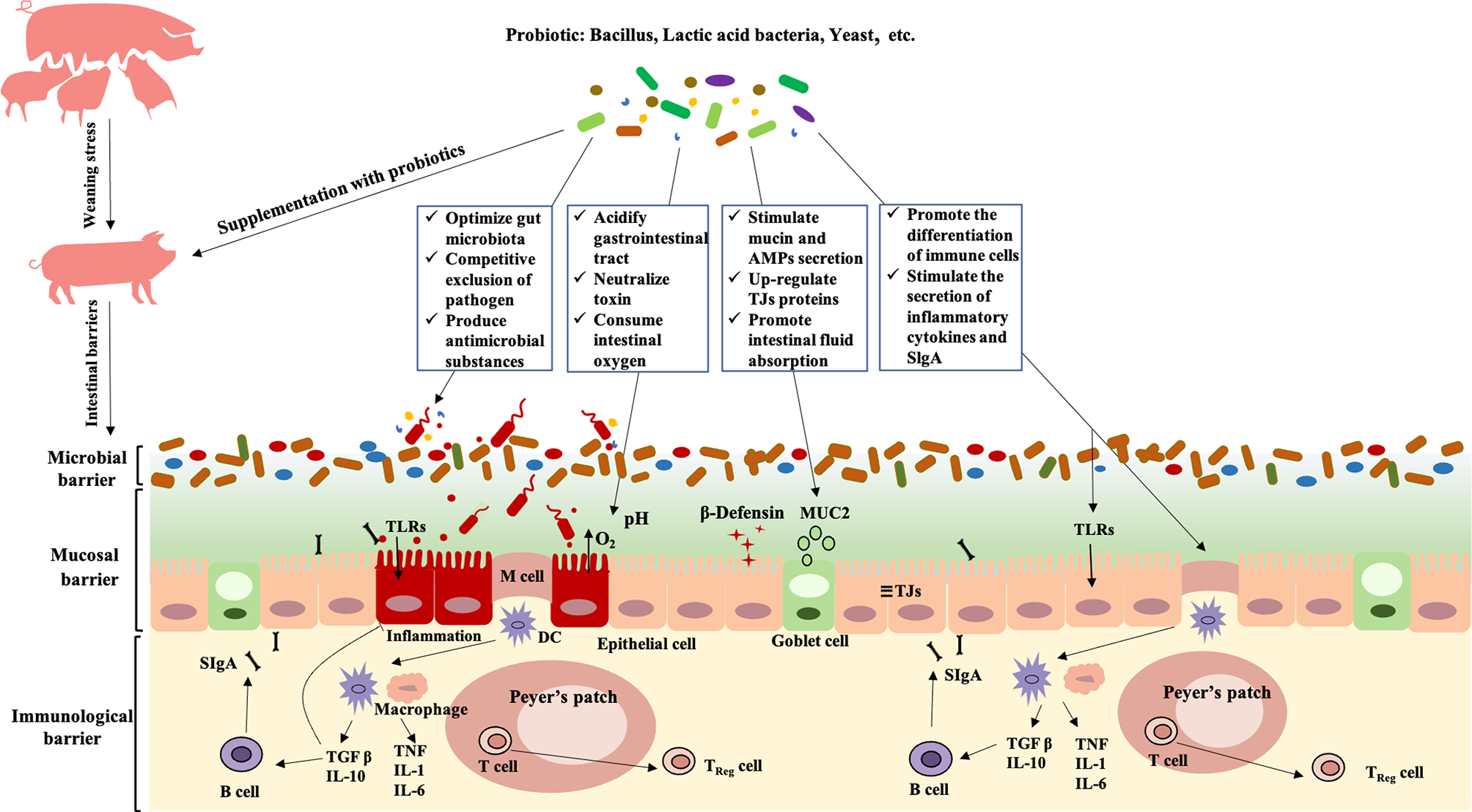

Probiotics is a potential alternative to antibiotics for the prevention and treatment of PWD. We review the research status of PWD-preventing and treating probiotics and discuss its potential regulatory mechanism from the perspective of intestinal barriers. Different from antibiotics, probiotics generally play a role in PWD through restoring the balance of intestinal microecology and regulating intestinal mucosal and immunological barriers. Different probiotic species exert their health-regulatory effects for PWD through diverse ways such as competitive exclusion of pathogen, producing antimicrobial substance and neutralizing toxin, improving intestinal permeability, and promoting the proliferation and differentiation of intestinal immune cell (Figure 1). Consequently, probiotics have unique advantages and considerable potential in application to PWD of piglets.

Figure 1

Modulation of probiotics on intestinal barriers in postweaning diarrhea piglets. Probiotics relieve PWD by regulating the intestinal microbial barrier: 1) shaping the gut microbiota oriented by beneficial bacteria; 2) competitive exclusion of pathogen; 3) producing antimicrobial substance and neutralize toxin. Probiotics relieve PWD by regulating the intestinal mucosal barrier: 1) stimulating the secretion of mucin and antimicrobial peptides; 2) upregulation of intestinal tight junction protein expression; 3) maintaining normal intestinal permeability, and promoting intestinal fluid absorption and secretion reduction. Probiotics relieve PWD by regulating the intestinal immunological barrier: 1) promoting the proliferation and differentiation of intestinal immune cell; 2) stimulating the secretion of inflammatory and SlgA. TLRs, Toll-like Receptors; MUC2, Mucin 2; TJs, Tight Junctions; DC, Dendritic Cell; TGF-β, Transforming growth factor-β; TNF, Tumor Necrosis Factor); IL, Interleukin; SIgA, Secretory Immunoglobulin A;AMPs, antimicrobial peptides.

From the research status on the regulation effect of probiotics on the intestinal barriers of postweaning piglets, prevention and treatment combinations may be future directions. More in vivo or in vitro experiments should be carried out to screen for probiotics (such as Lactobacillus) from normal weaned healthy piglets that can stably colonize the piglet’s gut, efficiently produce antibacterial substances, competitively exclude of pathogen, improve intestinal mucosal barrier and activate the immune system to prevent PWD. Although some fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) experiments have been carried out and achieved good results (Ma et al., 2021), the effect of specific flora or strains on intestinal colonization of early piglets still needs further research. In addition, supplementing probiotics to accelerate the maturation of gut microbiota or to shape a PWD-preventing gut microbiota in weaned piglets are worthy of further study. Furthermore, probiotics may be used as a restorative agent to restore the disorders of gut microbiota and immune system that caused by antibiotics in piglets. Probiotics (prevention) - antibiotics (treatment) - probiotics (repair) may be a new combination strategy for early weaning piglets. Additionally, regulation mechanism of probiotics on intestinal barriers by the surface molecules and metabolites of probiotics suggested that direct use of the surface components and metabolites may be a viable and efficient strategy to prevent or treat PWD instead of probiotics during weaning of piglets.

Funding

The authors thank the specialized research fund from China Agriculture Research System of MOF and MARA (CARS-35), National Center of Technology Innovation for Pigs, Major Science and Technology Projects of Zhejiang and Shandong (2021C02008, 2019JZZY020602, 2019C02051, CTZB-2020080127).

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Statements

Author contributions

WS: Conceptualization, Writing - original draft. TG and ZJ: Writing - review & editing. ZL and YW: Resources, Writing - review and editing, Supervision. All authors edited, critically revised, and approved the final manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1

AllaireJ. M.CrowleyS. M.LawH. T.ChangS. Y.KoH. J.VallanceB. A. (2019). The Intestinal Epithelium: Central Coordinator of Mucosal Immunity. Trends Immunol.40, 174–174. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2018.12.008

2

AndersonR. C.CooksonA. L.McNabbW. C.ParkZ.McCannM. J.KellyW. J.et al. (2010). Lactobacillus Plantarum MB452 Enhances the Function of the Intestinal Barrier by Increasing the Expression Levels of Genes Involved in Tight Junction Formation. BMC Microbiol.10, 316. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-10-316

3

BadiaR.ZanelloG.ChevaleyreC.LizardoR.MeurensF.MartinezP.et al. (2012). Effect of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Var. Boulardii and Beta-Galactomannan Oligosaccharide on Porcine Intestinal Epithelial and Dendritic Cells Challenged In Vitro With Escherichia Coli F4 (K88). Vet. Res.43, 4. doi: 10.1186/1297-9716-43-4

4

BaldaM. S.MatterK. (2016). Tight Junctions as Regulators of Tissue Remodelling. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol.42, 94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2016.05.006

5

BaumgartD. C.DignassA. U. (2002). Intestinal Barrier Function. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr.5, 685–694. doi: 10.1097/00075197-200211000-00012

6

BevinsC. L.SalzmanN. H. (2011). Paneth Cells, Antimicrobial Peptides and Maintenance of Intestinal Homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.9, 356–368. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2546

7

BirchenoughG. M. H.JohanssonM. E. V.GustafssonJ. K.BergstromJ. H.HanssonG. C. (2015). New Developments in Goblet Cell Mucus Secretion and Function. Mucosal Immunol.8, 712–719. doi: 10.1038/mi.2015.32

8

BlautM.ClavelT. (2007). Metabolic Diversity of the Intestinal Microbiota: Implications for Health and Disease. J. Nutr.137, 751s–755s. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.3.751S

9

BronP. A.van BaarlenP.KleerebezemM. (2012). Emerging Molecular Insights Into the Interaction Between Probiotics and the Host Intestinal Mucosa. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.10, 66–U90. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2690

10

BuffieC. G.PamerE. G. (2013). Microbiota-Mediated Colonization Resistance Against Intestinal Pathogens. Nat. Rev. Immunol.13, 790–801. doi: 10.1038/nri3535

11

ButlerJ. E.WertzN. (2012). The Porcine Antibody Repertoire: Variations on the Textbook Theme. Front. Immunol.3. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00153

12

CarvalhoF. A.KorenO.GoodrichJ. K.JohanssonM. E. V.NalbantogluI.AitkenJ. D.et al. (2012). Transient Inability to Manage Proteobacteria Promotes Chronic Gut Inflammation in TLR5-Deficient Mice. Cell Host Microbe12, 139–152. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.07.004

13

ColladoM. C.GrzeskowiakL.SalminenS. (2007). Probiotic Strains and Their Combination Inhibit In Vitro Adhesion of Pathogens to Pig Intestinal Mucosa. Curr. Microbiol.55, 260–265. doi: 10.1007/s00284-007-0144-8

14

CollierC. T.CarrollJ. A.BallouM. A.StarkeyJ. D.SparksJ. C. (2011). Oral Administration of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Boulardii Reduces Mortality Associated With Immune and Cortisol Responses to Escherichia Coli Endotoxin in Pigs. J. Anim. Sci.89, 52–58. doi: 10.2527/jas.2010-2944

15

D'SouzaW. N.DouangpanyaJ.MuS.JaeckelP.ZhangM.MaxwellJ. R.et al. (2017). Differing Roles for Short Chain Fatty Acids and GPR43 Agonism in the Regulation of Intestinal Barrier Function and Immune Responses. PloS One12, e0180190. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0180190

16

DesaiM. S.SeekatzA. M.KoropatkinN. M.KamadaN.HickeyC. A.WolterM.et al. (2016). A Dietary Fiber-Deprived Gut Microbiota Degrades the Colonic Mucus Barrier and Enhances Pathogen Susceptibility. Cell167, 1339. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.043

17

DicksL. M. T.BotesM. (2010). Probiotic Lactic Acid Bacteria in the Gastro-Intestinal Tract: Health Benefits, Safety and Mode of Action. Benef. Microbes1, 11–29. doi: 10.3920/BM2009.0012

18

DubreuilJ. D. (2017). Enterotoxigenic Escherichia Coli and Probiotics in Swine: What the Bleep Do We Know? Biosci. Microb. Food H36, 75–90. doi: 10.12938/bmfh.16-030

19

EhrlichA. M.PachecoA. R.HenrickB. M.TaftD.XuG. G.HudaM. N.et al. (2020). Indole-3-Lactic Acid Associated With Bifidobacterium-Dominated Microbiota Significantly Decreases Inflammation in Intestinal Epithelial Cells. Bmc Microbiol20, 357 doi: 10.1186/s12866-020-02023-y

20

FuJ.WangT. H.XiaoX.ChengY. Z.WangF. Q.JinM. L.et al. (2021). Clostridium Butyricum ZJU-F1 Benefits the Intestinal Barrier Function and Immune Response Associated With Its Modulation of Gut Microbiota in Weaned Piglets. Cells-Basel10, 527. doi: 10.3390/cells10030527

21

GresseR.Chaucheyras-DurandF.FleuryM. A.Van de WieleT.ForanoE.Blanquet-DiotS. (2017). Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis in Postweaning Piglets: Understanding the Keys to Health. Trends Microbiol.25, 851–873. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2017.05.004

22

Guerra-OrdazA. A.Gonzalez-OrtizG.La RagioneR. M.WoodwardM. J.CollinsJ. W.PerezJ. F.et al. (2014). Lactulose and Lactobacillus Plantarum, a Potential Complementary Synbiotic To Control Postweaning Colibacillosis in Piglets. Appl. Environ. Microb.80, 4879–4886. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00770-14

23

GuevarraR. B.HongS. H.ChoJ. H.KimB. R.ShinJ.LeeJ. H.et al. (2018). The Dynamics of the Piglet Gut Microbiome During the Weaning Transition in Association With Health and Nutrition. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechno.9, 54. doi: 10.1186/s40104-018-0269-6

24

GuilloteauP.MartinL.EeckhautV.DucatelleR.ZabielskiR.Van ImmerseelF. (2010). From the Gut to the Peripheral Tissues: The Multiple Effects of Butyrate. Nutr. Res. Rev.23, 366–384. doi: 10.1017/S0954422410000247

25

HanG. Q.XiangZ. T.YuB.ChenD. W.QiH. W.MaoX. B.et al. (2012). Effects of Different Starch Sources on Bacillus Spp. In Intestinal Tract and Expression of Intestinal Development Related Genes of Weanling Piglets. Mol. Biol. Rep.39, 1869–1876. doi: 10.1007/s11033-011-0932-x

26

HillmanK.MurdochT. A.SpencerR. J.StewartC. S. (1994). Inhibition of Enterotoxigenic Escherichia-Coli by the Microflora of the Porcine Ileum, in an in-Vitro Semicontinuous Culture System. J. Appl. Bacteriol.76, 294–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1994.tb01631.x

27

HooperL. V.MacphersonA. J. (2010). Immune Adaptations That Maintain Homeostasis With the Intestinal Microbiota. Nat. Rev. Immunol.10, 159. doi: 10.1038/nri2710

28

HouQ. H.YeL. L.LiuH. F.HuangL. L.YangQ.TurnerJ. R.et al. (2021). Lactobacillus Accelerates ISCs Regeneration to Protect the Integrity of Intestinal Mucosa Through Activation of STAT3 Signaling Pathway Induced by LPLs Secretion of IL-22. Cell Death Differ.28, 2025–2027. doi: 10.1038/s41418-020-00630-w

29

HuJ.ChenL. L.ZhengW. Y.ShiM.LiuL.XieC. L.et al. (2018a). Lactobacillus Frumenti Facilitates Intestinal Epithelial Barrier Function Maintenance in Early-Weaned Piglets. Front. Microbiol.9. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00897

30

HuY. L.DunY. H.LiS. N.ZhangD. X.PengN.ZhaoS. M.et al. (2015). Dietary Enterococcus Faecalis LAB31 Improves Growth Performance, Reduces Diarrhea, and Increases Fecal Lactobacillus Number of Weaned Piglets. PloS One10, e0116635. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116635

31

HuY. L.DunY. H.LiS. A.ZhaoS. M.PengN.LiangY. X. (2014). Effects of Bacillus Subtilis KN-42 on Growth Performance, Diarrhea and Faecal Bacterial Flora of Weaned Piglets. Asian Austral J. Anim.27, 1131–1140. doi: 10.5713/ajas.2013.13737

32

HuJ.MaL. B.NieY. F.ChenJ. W.ZhengW. Y.WangX. K.et al. (2018b). A Microbiota-Derived Bacteriocin Targets the Host to Confer Diarrhea Resistance in Early-Weaned Piglets. Cell Host Microbe24, 817. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2018.11.006

33

HumphreyB.ZhaoJ.FarisR. (2019). Review: Link Between Intestinal Immunity and Practical Approaches to Swine Nutrition. Animal13, 2736–2744. doi: 10.1017/S1751731119001861

34

HuC. H.XiaoK.LuanZ. S.SongJ. (2013). Early Weaning Increases Intestinal Permeability, Alters Expression of Cytokine and Tight Junction Proteins, and Activates Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases in Pigs. J. Anim. Sci.91, 1094–1101. doi: 10.2527/jas.2012-5796

35

IndoY.KitaharaS.TomokiyoM.ArakiS.IslamM. A.ZhouB. H.et al. (2021). Ligilactobacillus Salivarius Strains Isolated From the Porcine Gut Modulate Innate Immune Responses in Epithelial Cells and Improve Protection Against Intestinal Viral-Bacterial Superinfection. Front. Immunol.12. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.652923

36

JensenM. S.JensenS. K.JakobsenK. (1997). Development of Digestive Enzymes in Pigs With Emphasis on Lipolytic Activity in the Stomach and Pancreas. J. Anim. Sci.75, 437–445. doi: 10.2527/1997.752437x

37

KamadaN.SeoS. U.ChenG. Y.NunezG. (2013). Role of the Gut Microbiota in Immunity and Inflammatory Disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol.13, 321–335. doi: 10.1038/nri3430

38

KiarieE.BhandariS.ScottM.KrauseD. O.NyachotiC. M. (2011). Growth Performance and Gastrointestinal Microbial Ecology Responses of Piglets Receiving Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Fermentation Products After an Oral Challenge With Escherichia Coli (K88). J. Anim. Sci.89, 1062–1078. doi: 10.2527/jas.2010-3424

39

KimS. H.YangS. J.KooH. C.BaeW. K.KimJ. Y.ParkJ. H.et al. (2001). Inhibitory Activity of Bifidobacterium Longum HY8001 Against Vero Cytotoxin of Escherichia Coli O157:H7. J. Food Prot.64, 1667–1673. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-64.11.1667

40

KnausU. G.HertzbergerR.PircalabioruG. G.YousefiS. P. M.dos SantosF. B. (2017). Pathogen Control at the Intestinal Mucosa - H2O2 to the Rescue. Gut. Microbes8, 67–74. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2017.1279378

41

KonstantinovS. R.AwatiA. A.WilliamsB. A.MillerB. G.JonesP.StokesC. R.et al. (2006). Post-Natal Development of the Porcine Microbiota Composition and Activities. Environ. Microbiol.8, 1191–1199. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01009.x

42

KumarP.LuoQ. W.VickersT. J.SheikhA.LewisW. G.FleckensteinJ. M. (2014). EatA, an Immunogenic Protective Antigen of Enterotoxigenic Escherichia Coli, Degrades Intestinal Mucin. Infect. Immun.82, 500–508. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01078-13

43

LairdT. J.AbrahamS.JordanD.PluskeJ. R.HampsonD. J.TrottD. J.et al. (2021). Porcine Enterotoxigenic Escherichia Coli: Antimicrobial Resistance and Development of Microbial-Based Alternative Control Strategies. Vet. Microbiol.258, 109117. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2021.109117

44

LebeerS.BronP. A.MarcoM. L.Van PijkerenJ. P.O'Connell MotherwayM.HillC.et al. (2018). Identification of Probiotic Effector Molecules: Present State and Future Perspectives. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol.49, 217–223. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2017.10.007

45

Le DividichJ.SeveB. (2000). Effects of Underfeeding During the Weaning Period on Growth, Metabolism, and Hormonal Adjustments in the Piglet. Domest. Anim. Endocrin.19, 63–74. doi: 10.1016/S0739-7240(00)00067-9

46

LiJ. Y. (2017). Current Status and Prospects for in-Feed Antibiotics in the Different Stages of Pork Production - A Review. Asian Austral J. Anim.30, 1667–1673. doi: 10.5713/ajas.17.0418

47

LiaoS. F.NyachotiM. (2017). Using Probiotics to Improve Swine Gut Health and Nutrient Utilization. Anim. Nutr.3, 331–343. doi: 10.1016/j.aninu.2017.06.007

48

LiewF. Y. (2002). T(H)1 and T(H)2 Cells: A Historical Perspective. Nat. Rev. Immunol.2, 55–60. doi: 10.1038/nri705

49

LiY. H.HouS. L.ChenJ. S.PengW.WenW.ChenF. M.et al. (2019b). Oral Administration of Lactobacillus Delbrueckii During the Suckling Period Improves Intestinal Integrity After Weaning in Piglets. J. Funct. Foods63, 103591. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2019.103591

50

LiY.HouS.PengW.LinQ.ChenF.YangL.et al. (2019a). Oral Administration of Lactobacillus Delbrueckii During the Suckling Phase Improves Antioxidant Activities and Immune Responses After the Weaning Event in a Piglet Model. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev.2019, 6919803. doi: 10.1155/2019/6919803

51

LiH. H.LiuX. J.ShangZ. Y.QiaoJ. Y. (2021). Clostridium Butyricum Helps to Alleviate Inflammation in Weaned Piglets Challenged With Enterotoxigenic Escherichia Coli K88. Front. Veterinary Sci.8. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.683863

52

LiuH. B.HouC. L.WangG.JiaH. M.YuH. T.ZengX. F.et al. (2017). Lactobacillus Reuteri I5007 Modulates Intestinal Host Defense Peptide Expression in the Model of IPEC-J2 Cells and Neonatal Piglets. Nutrients9, 559. doi: 10.3390/nu9060559

53

LiuQ.YuZ.TianF.ZhaoJ.ZhangH.ZhaiQ.et al. (2020). Surface Components and Metabolites of Probiotics for Regulation of Intestinal Epithelial Barrier. Microb. Cell Fact19, 23. doi: 10.1186/s12934-020-1289-4

54

LuX.ZhangM.ZhaoL.GeK.WangZ.JunL.et al. (2018). Growth Performance and Post-Weaning Diarrhea in Piglets Fed a Diet Supplemented With Probiotic Complexes. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol.28, 1791–1799. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1807.07026

55

MaynardC. L.ElsonC. O.HattonR. D.WeaverC. T. (2012). Reciprocal Interactions of the Intestinal Microbiota and Immune System. Nature489, 231–241. doi: 10.1038/nature11551

56

MaX.ZhangY.XuT.QianM.YangZ.ZhanX.et al. (2021). Early-Life Iintervention Using Exogenous Fecal Microbiota Alleviates Gut Injury and Reduce Inflammation Caused by Weaning Stress in Piglets. Front. Microbiol.12, 671683. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.671683

57

McCrackenV. J.LorenzR. G. (2001). The Gastrointestinal Ecosystem: A Precarious Alliance Among Epithelium, Immunity and Microbiota. Cell Microbiol.3, 1–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2001.00090.x

58

MoeserA. J.PohlC. S.RajputM. (2017). Weaning Stress and Gastrointestinal Barrier Development: Implications for Lifelong Gut Health in Pigs. Anim. Nutr.3, 313–321. doi: 10.1016/j.aninu.2017.06.003

59

MolistF.van EerdenE.ParmentierH. K.VuorenmaaJ. (2014). Effects of Inclusion of Hydrolyzed Yeast on the Immune Response and Performance of Piglets After Weaning. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol.195, 136–141. doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2014.04.020

60

NairM. S.AmalaradjouM. A.VenkitanarayananK. (2017). Antivirulence Properties of Probiotics in Combating Microbial Pathogenesis. Adv. Appl. Microbiol.98, 1–29. doi: 10.1016/bs.aambs.2016.12.001

61

NgoD. H.VoT. S. (2019). An Updated Review on Pharmaceutical Properties of Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid. Molecules24, 2678. doi: 10.3390/molecules24152678

62

O'SheaE. F.CotterP. D.StantonC.RossR. P.HillC. (2012). Production of Bioactive Substances by Intestinal Bacteria as a Basis for Explaining Probiotic Mechanisms: Bacteriocins and Conjugated Linoleic Acid. Int. J. Food Microbiol.152, 189–205. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.05.025

63

OkumuraR.TakedaK. (2018). Maintenance of Intestinal Homeostasis by Mucosal Barriers. Inflammation Regener.38, 5. doi: 10.1186/s41232-018-0063-z

64

PamerE. G. (2016). Resurrecting the Intestinal Microbiota to Combat Antibiotic-Resistant Pathogens. Science352, 535–538. doi: 10.1126/science.aad9382

65

PanL.ZhaoP. F.MaX. K.ShangQ. H.XuY. T.LongS. F.et al. (2017). Probiotic Supplementation Protects Weaned Pigs Against Enterotoxigenic Escherichia Coli K88 Challenge and Improves Performance Similar to Antibiotics. J. Anim. Sci.95, 2627–2639. doi: 10.2527/jas.2016.1243

66

ParkM. S.KimM. J.JiG. E. (2007). Assessment of Lipopolysaccharide-Binding Activity of Bifidobacterium and its Relationship With Cell Surface Hydrophobicity, Autoaggregation, and Inhibition of Interleukin-8 Production. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol.17, 1120–26. doi: 10.1007/s10295-007-0211-y

67

Perez-CobasA. E.GosalbesM. J.FriedrichsA.KnechtH.ArtachoA.EismannK.et al. (2013). Gut Microbiota Disturbance During Antibiotic Therapy: A Multi-Omic Approach. Gut62, 1591–1601. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303184

68

PralL. P.FachiJ. L.CorreaR. O.ColonnaM.VinoloM. A. R. (2021). Hypoxia and HIF-1 as Key Regulators of Gut Microbiota and Host Interactions. Trends Immunol.42, 604–621. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2021.05.004

69

PriceK. L.TottyH. R.LeeH. B.UttM. D.FitznerG. E.YoonI.et al. (2010). Use of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Fermentation Product on Growth Performance and Microbiota of Weaned Pigs During Salmonella Infection. J. Anim. Sci.88, 3896–3908. doi: 10.2527/jas.2009-2728

70

QinH. L.ZhangZ. W.HangX. M.JiangY. Q. (2009). L. Plantarum Prevents Enteroinvasive Escherichia Coli-Induced Tight Junction Proteins Changes in Intestinal Epithelial Cells. BMC Microbiol.963. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-63

71

SalzmanN. H. (2011). Microbiota-Immune System Interaction: An Uneasy Alliance. Curr. Opin. Microbiol.14, 99–105. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2010.09.018

72

SalzmanN. H.UnderwoodM. A.BevinsC. L. (2007). Paneth Cells, Defensins, and the Commensal Microbiota: A Hypothesis on Intimate Interplay at the Intestinal Mucosa. Semin. Immunol.19, 70–83. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.04.002

73

Scharek-TedinL.PieperR.VahjenW.TedinK.NeumannK.ZentekJ. (2013). Bacillus Cereus Var. Toyoi Modulates the Immune Reaction and Reduces the Occurrence of Diarrhea in Piglets Challenged With Salmonella Typhimurium DT104. J. Anim. Sci.91, 5696–5704. doi: 10.2527/jas.2013-6382

74

SethA.YanF.PolkD. B.RaoR. K. (2008). Probiotics Ameliorate the Hydrogen Peroxide-Induced Epithelial Barrier Disruption by a PKC- and MAP Kinase-Dependent Mechanism. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol.294, G1060–G1069. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00202.2007

75

ShanahanF. (2010). Probiotics in Perspective. Gastroenterology139, 1808–1812. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.10.025

76

SharmaR.YoungC.NeuJ. (2010). Molecular Modulation of Intestinal Epithelial Barrier: Contribution of Microbiota. J. BioMed. Biotechnol, 2010, 305879. doi: 10.1155/2010/305879

77

ShonyelaS. M.FengB.YangW. T.YangG. L.WangC. F. (2020). The Regulatory Effect of Lactobacillus Rhamnosus GG on T Lymphocyte and the Development of Intestinal Villi in Piglets of Different Periods. Amb. Express10, 76 doi: 10.1186/s13568-020-00980-1

78

SommerF.AndersonJ. M.BhartiR.RaesJ.RosenstielP. (2017). The Resilience of the Intestinal Microbiota Influences Health and Disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.15, 630–638. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.58

79

SperandioB.FischerN.SansonettiP. J. (2015). Mucosal Physical and Chemical Innate Barriers: Lessons From Microbial Evasion Strategies. Semin. Immunol.27, 111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2015.03.011

80

SunD.BaiR.ZhouW.YaoZ.LiuY.TangS.et al. (2021a). Angiogenin Maintains Gut Microbe Homeostasis by Balancing Alpha-Proteobacteria and Lachnospiraceae. Gut70, 666–676. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-320135

81

SunY. W.DuarteM. E.KimS. W. (2021b). Dietary Inclusion of Multispecies Probiotics to Reduce the Severity of Post-Weaning Diarrhea Caused by Escherichia Coli F18(+) in Pigs. Anim. Nutr.7, 326–333. doi: 10.1016/j.aninu.2020.08.012

82

SutherlandM. A.BackusB. L.McGloneJ. J. (2014). Effects of Transport at Weaning on the Behavior, Physiology and Performance of Pigs. Anim. (Basel)4, 657–669. doi: 10.3390/ani4040657

83

TangW. J.ChenD. W.YuB.HeJ.HuangZ. Q.ZhengP.et al. (2020). Capsulized Faecal Microbiota Transplantation Ameliorates Post-Weaning Diarrhoea by Modulating the Gut Microbiota in Piglets. Vet. Res.51, 55. doi: 10.1186/s13567-020-00779-9

84

TianS.WangJ.WangJ.ZhuW. (2022). Differential Effects of Early-Life and Postweaning Galacto-Oligosaccharide Intervention on Colonic Bacterial Composition and Function in Weaning Piglets. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.88, e0131821. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01318-21

85

TrckovaM.FaldynaM.AlexaP.ZajacovaZ. S.GopfertE.KumprechtovaD.et al. (2014). The Effects of Live Yeast Saccharomyces Cerevisiae on Postweaning Diarrhea, Immune Response, and Growth Performance in Weaned Piglets. J. Anim. Sci.92, 767–774. doi: 10.2527/jas.2013-6793

86

van BaarlenP.TroostF.van der MeerC.HooiveldG.BoekschotenM.BrummerR. J. M.et al. (2011). Human Mucosal In Vivo Transcriptome Responses to Three Lactobacilli Indicate How Probiotics may Modulate Human Cellular Pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA108, 4562–4569. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000079107

87

van ZylW. F.DeaneS. M.DicksL. M. T. (2020). Molecular Insights Into Probiotic Mechanisms of Action Employed Against Intestinal Pathogenic Bacteria. Gut. Microbes12, 1831339. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2020.1831339

88

VirdiV.PalaciJ.LaukensB.RyckaertS.CoxE.VanderbekeE.et al. (2019). Yeast-Secreted, Dried and Food-Admixed Monomeric IgA Prevents Gastrointestinal Infection in a Piglet Model. Nat. Biotechnol.37, 527–530. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0070-x

89

WangK.ChenG.CaoG.XuY.WangY.YangC. (2019a). Effects of Clostridium Butyricum and Enterococcus Faecalis on Growth Performance, Intestinal Structure, and Inflammation in Lipopolysaccharide-Challenged Weaned Piglets. J. Anim. Sci.97, 4140–4151. doi: 10.1093/jas/skz235

90

WangX. L.LiuZ. Y.LiY. H.YangL. Y.YinJ.HeJ. H.et al. (2021). Effects of Dietary Supplementation of Lactobacillus Delbrueckii on Gut Microbiome and Intestinal Morphology in Weaned Piglets. Front. Vet. Sci.8. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.692389

91

WangY.LiuL.MooreD. J.ShenX.PeekR. M.AcraS. A.et al. (2017). An LGG-Derived Protein Promotes IgA Production Through Upregulation of APRIL Expression in Intestinal Epithelial Cells. Mucosal Immunol.10, 373–384. doi: 10.1038/mi.2016.57

92

WangT. W.TengK. L.LiuY. Y.ShiW. X.ZhangJ.DongE. Q.et al. (2019b). Lactobacillus Plantarum PFM 105 Promotes Intestinal Development Through Modulation of Gut Microbiota in Weaning Piglets. Front. Microbiol.10. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00090

93

WangZ. L.WangL.ChenZ.MaX. Y.YangX. F.ZhangJ.et al. (2016b). In Vitro Evaluation of Swine-Derived Lactobacillus Reuteri: Probiotic Properties and Effects on Intestinal Porcine Epithelial Cells Challenged With Enterotoxigenic Escherichia Coli K88. J. Microbiol. Biotechn.26, 1018–1025. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1510.10089

94

WangJ.ZengL. M.TanB.LiG. R.HuangB.XiongX.et al. (2016a). Developmental Changes in Intercellular Junctions and Kv Channels in the Intestine of Piglets During the Suckling and Post-Weaning Periods. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechno.7, 4. doi: 10.1186/s40104-016-0063-2

95

WangJ.ZengY. X.WangS. X.LiuH.ZhangD. Y.ZhangW.et al. (2018). Swine-Derived Probiotic Lactobacillus Plantarum Inhibits Growth and Adhesion of Enterotoxigenic Escherichia Coli and Mediates Host Defense. Front. Microbiol.9, 1364. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01364

96

WangH.ZhangW.ZuoL.DongJ.ZhuW.LiY.et al. (2014). Intestinal Dysbacteriosis Contributes to Decreased Intestinal Mucosal Barrier Function and Increased Bacterial Translocation. Lett. Appl. Microbiol.58, 384–392. doi: 10.1111/lam.12201

97

WeiH. K.XueH. X.ZhouZ. X.PengJ. (2017). A Carvacrol-Thymol Blend Decreased Intestinal Oxidative Stress and Influenced Selected Microbes Without Changing the Messenger RNA Levels of Tight Junction Proteins in Jejunal Mucosa of Weaning Piglets. Animal11, 193–201. doi: 10.1017/S1751731116001397

98

WuY. P.ZhuC.ChenZ.ChenZ. J.ZhangW. N.MaX. Y.et al. (2016). Protective Effects of Lactobacillus Plantarum on Epithelial Barrier Disruption Caused by Enterotoxigenic Escherichia Coli in Intestinal Porcine Epithelial Cells. Veterinary Immunol. Immunopathology.172, 55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2016.03.005

99

XiangQ. H.WuX. Y.PanY.WangL.CuiC. B.GuoY. W.et al. (2020). Early-Life Intervention Using Fecal Microbiota Combined With Probiotics Promotes Gut Microbiota Maturation, Regulates Immune System Development, and Alleviates Weaning Stress in Piglets. Int. J. Mol. Sci.21. doi: 10.3390/ijms21020503

100

XiaoY.YanH. L.DiaoH.YuB.HeJ.YuJ.et al. (2017). Early Gut Microbiota Intervention Suppresses DSS-Induced Inflammatory Responses by Deactivating TLR/NLR Signalling in Pigs. Sci. Rep-Uk7, 3224. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-03161-6

101

XinJ.ZengD.WangH.SunN.ZhaoY.DanY.et al. (2020). Probiotic Lactobacillus Johnsonii BS15 Promotes Growth Performance, Intestinal Immunity, and Gut Microbiota in Piglets. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins12, 184–193. doi: 10.1007/s12602-018-9511-y

102

YangK. M.JiangZ. Y.ZhengC. T.WangL.YangX. F. (2014). Effect of Lactobacillus Plantarum on Diarrhea and Intestinal Barrier Function of Young Piglets Challenged With Enterotoxigenic Escherichia Coli K88. J. Anim. Sci.92, 1496–1503. doi: 10.2527/jas.2013-6619

103

YangJ.QianK.WangC.WuY. (2018). Roles of Probiotic Lactobacilli Inclusion in Helping Piglets Establish Healthy Intestinal Inter-Environment for Pathogen Defense. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins10, 243–250. doi: 10.1007/s12602-017-9273-y

104

YinF. G.FarzanA.WangQ.YuH.YinY. L.HouY. Q.et al. (2014). Reduction of Salmonella Enterica Serovar Typhimurium DT104 Infection in Experimentally Challenged Weaned Pigs Fed a Lactobacillus-Fermented Feed. Foodborne Pathog. Dis.11, 628–634. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2013.1676

105

ZanelloG.MeurensF.BerriM.ChevaleyreC.MeloS.AuclairE.et al. (2011). Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Decreases Inflammatory Responses Induced by F4(+) Enterotoxigenic Escherichia Coli in Porcine Intestinal Epithelial Cells. Veterinary Immunol. Immunopathology.141, 133–138. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2011.01.018

106

ZengM. Y.InoharaN.NunezG. (2017). Mechanisms of Inflammation-Driven Bacterial Dysbiosis in the Gut. Mucosal Immunol.10, 18–26. doi: 10.1038/mi.2016.75

107

ZhangW.ZhuY. H.ZhouD.WuQ.SongD.DicksvedJ.et al. (2017). Oral Administration of a Select Mixture of Bacillus Probiotics Affects the Gut Microbiota and Goblet Cell Function Following Escherichia Coli Challenge in Newly Weaned Pigs of Genotype MUC4 That Are Supposed To Be Enterotoxigenic E. Coli F4ab/ac Receptor Negative. Appl. Environ. Microb.83, e02747–16. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02747-16

108

ZhaoW. S.YuanM.LiP. C.YanH. L.ZhangH. F.LiuJ. B. (2019). Short-Chain Fructo-Oligosaccharides Enhances Intestinal Barrier Function by Attenuating Mucosa Inflammation and Altering Colonic Microbiota Composition of Weaning Piglets. Ital. J. Anim. Sci.18, 976–986. doi: 10.1080/1828051X.2019.1612286

109

ZhaxiY. P.MengX. Q.WangW. H.WangL.HeZ. L.ZhangX. J.et al. (2020). Duan-Nai-An, A Yeast Probiotic, Improves Intestinal Mucosa Integrity and Immune Function in Weaned Piglets. Sci. Rep-Uk10, 4556. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-61279-6

110

ZhuJ. J.GaoM. X.ZhangR. L.SunZ. J.WangC. M.YangF. F.et al. (2017b). Effects of Soybean Meal Fermented by L. Plantarum, B. Subtilis and S. Cerevisieae on Growth, Immune Function and Intestinal Morphology in Weaned Piglets. Microb. Cell Fact16, 191. doi: 10.1186/s12934-017-0809-3

111

ZhuY. H.LiX. Q.ZhangW.ZhouD.LiuH. Y.WangJ. F. (2014). Dose-Dependent Effects of Lactobacillus Rhamnosus on Serum Interleukin-17 Production and Intestinal T-Cell Responses in Pigs Challenged With Escherichia Coli. Appl. Environ. Microb.80, 1787–1798. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03668-13

112

ZhuC.WangL.WeiS. Y.ChenZ.MaX. Y.ZhengC. T.et al. (2017a). Effect of Yeast Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Supplementation on Serum Antioxidant Capacity, Mucosal Siga Secretions and Gut Microbial Populations in Weaned Piglets. J. Integr. Agr.16, 2029–2037. doi: 10.1016/S2095-3119(16)61581-2

113

ZongX.CaoX. X.WangH.XiaoX.WangY. Z.LuZ. Q. (2019a). Cathelicidin-WA Facilitated Intestinal Fatty Acid Absorption Through Enhancing PPAR-Gamma Dependent Barrier Function. Front. Immunol.10. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01674

114

ZongX.FuJ.XuB. C.WangY. Z.JinM. L. (2020). Interplay Between Gut Microbiota and Antimicrobial Peptides. Anim. Nutr.6, 389–396. doi: 10.1016/j.aninu.2020.09.002

115

ZongX.WangT. H.LuZ. Q.SongD. G.ZhaoJ.WangY. Z. (2019b). Effects of Clostridium Butyricum or in Combination With Bacillus Licheniformis on the Growth Performance, Blood Indexes, and Intestinal Barrier Function of Weanling Piglets. Livest. Sci.220, 137–142. doi: 10.1016/j.livsci.2018.12.024

116

ZongX.XiaoX.JieF.ChengY. Z.JinM. L.YinY. L.et al. (2021). YTHDF1 Promotes NLRP3 Translation to Induce Intestinal Epithelial Cell Inflammatory Injury During Endotoxic Shock. Sci. China Life Sci.64, 1988–1991. doi: 10.1007/s11427-020-1909-6

Summary

Keywords

piglets, postweaning diarrhea, antibiotics, probiotics, intestinal barriers

Citation

Su W, Gong T, Jiang Z, Lu Z and Wang Y (2022) The Role of Probiotics in Alleviating Postweaning Diarrhea in Piglets From the Perspective of Intestinal Barriers. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 12:883107. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.883107

Received

24 February 2022

Accepted

04 May 2022

Published

30 May 2022

Volume

12 - 2022

Edited by

Arun K. Bhunia, Purdue University, United States

Reviewed by

Zhaolai Dai, China Agricultural University, China; Shenfei Long, China Agricultural University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2022 Su, Gong, Jiang, Lu and Wang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yizhen Wang, yzwang321@zju.edu.cn

This article was submitted to Microbiome in Health and Disease, a section of the journal Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.