- Department of Human Resource Management, School of Management, Shandong University, Jinan, China

As an emerging research field of leadership, inclusive leadership reflects the new style of leadership demanded by researchers and practitioners. Is it a leadership style that can better integrate employees and organizations and adapt to new complex management situation? Based on theories of social exchange, organizational support, and self-determination, this study investigated the impact of inclusive leadership on employee voice behavior and team performance through caring ethical climate. We evaluated the model with a time-lagged data of 329 team members from 105 teams in six cities in China. Results indicated as following: inclusive leadership was positively correlated with employee voice behavior at the individual level and team performance at the team level; caring ethical climate mediated the relationship between inclusive leadership and employee voice behavior at the individual level, as well as mediated the relationship between inclusive leadership and team performance at the team level. This study revealed the mechanism of the positive cross-level effects of inclusive leadership on the caring ethical climate, employee voice behavior, and team performance. These findings also provided important contributions for human resource management and practice.

Introduction

Given the rapid changes in market environment and fierce competition between companies, how to improve organizational competence becomes an extremely important issue. As teams in companies are more flexible and organized than individuals in confronting complicated problems, focusing on team behavior and performance provides numerous benefits for the companies. Currently, studies on factors influencing team performance and effectiveness have identified team leadership as the most important factor, particularly that which has the potential to motivate the team member and improve team performance.

Team members’ constructive behaviors, such as employee voice, can improve organizational performance (Hsiung, 2012) because, as a prosocial role behavior, the voice of the team member can shape a team-based work context and establish a relationship between the team members and thus benefit performance. However, few studies have focused on evaluating the relation between leadership with employee voice at the team level and the mechanism through which leadership affect the voice of the team member in the context of teamwork.

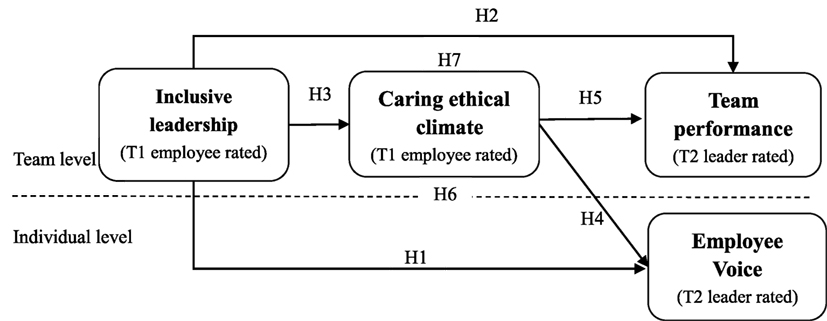

In this study, we used the data pertaining to 105 teams and 329 team members in China and conducted a multilevel empirical study to investigate the influence of an inclusive leadership style on team performance. We also investigated caring ethical climate as a mediator between inclusive leadership and team-member voice. The model of this research is presented in Figure 1.

Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

Inclusive Leadership and Employee Voice

Inclusive leadership was first defined by Nembhard and Edmondson (2006) as a relationship style that always accepts the differences of various members. Carmeli et al. (2010) emphasized that “inclusive leadership refers to leaders who exhibit openness, accessibility, and availability in their interactions with followers.” According to Ospina et al. (2011), leader inclusiveness does not only acknowledge the value of diversity but is also responsible for this variance. Current research shows that leadership inclusiveness correlates with diversity of team member behavior (Kearney and Gebert, 2009). These studies agree that inclusive leadership can shape the comprehensive work circumstance, overcome barriers between members with different backgrounds, and improve work coordination and other team performances (Wasserman et al., 2008; Shore et al., 2011; Mor Barak, 2013).

Hirschman (2011), who first proposed the definition of employee voice, assessed that employees who were not satisfied with their jobs would have two responses: to voice or to quit. Voice is the method of solving problems by expressing opinions. Employees willing to share their constructive suggestions can benefit the development of their organization. A number of management studies have been published to encourage employee voice (Farh et al., 2007).

Employee voice is a socially based behavior (Van Dyne and Le Pine, 1998). Suk et al. (2015) indicated that inclusive leadership can positively affect employee work engagement. Svendsen and Joensson (2016) demonstrated that transformational leadership can positively influence employee voice, productivity, and performance. Hirak et al. (2012) concluded that leadership inclusiveness implies acceptance of new information, listening to a new voice, and receiving a new challenge. These behaviors can change employee work attitudes, increase trust in leadership and the organization, and enhance attachment to their organization. The inclusive leader can also improve the psychological security (Hirak et al., 2012) and team identity of the subordinates (Mitchell et al., 2015). Therefore, the inclusive leader can build team member trust across the organization and increase attachment to the leader; thus, it can improve employee voice. Specifically, the following hypotheses are presented:

Hypothesis 1: Team-level inclusive leadership is positively related to individual-level employee voice.

Inclusive Leadership and Team Performance

To improve team-level performance, leaders consider not only how to improve performance at the individual level but also the need for team members to collaborate among themselves in order to improve team performance. To achieve these aims, leaders must first show an influential leadership. West (2004) suggested that if the leader shares with the team members his idea and information in the decision-making process, the team members are more likely to acknowledge their responsibility in the team, consequently improving team performance. Dionne et al. (2004) asserted that transformational leadership can improve team performance by improving individual performance as well as teamwork process. In addition to effective leadership, building a positive social environment in the context of teamwork is likewise necessary; this method might be the most important mediating mechanism to team output (Gladstein, 1984, Ancona and Caldwell, 1992, Anderson and West, 1998).

In some ways, leader inclusiveness is a mixture of transformational leadership and transactional leadership. Both types of leadership can positively affect team task performance. Inclusive leaders perceive team members as contributors, acknowledging everyone’s value. This behavior can increase the commitment of team members and motivate team members to handle their work in a flexible manner (Carmeli et al., 2010). In addition, leader inclusiveness can more effectively promote member perception of team goals, job satisfaction, and direct improvement of team task performance. Hence, we expect that:

Hypothesis 2: Inclusive leadership will be positively related to team performance.

Inclusive Leadership and Caring Ethical Climate

Organizational ethical climate is a component of organizational climate. It mainly refers to shared employee perceptions of ethical norms and behavior. Ethical climate can guide the ethical attitude, belief, and motivation of employees; likewise, it can affect ways to solve ethical problems at the organizational level. Several studies have been conducted to explore the antecedent of ethical climate (Rathert and Fleming, 2008, Mossholder et al., 2011). The majority of these studies have agreed that leadership exert a greater positive influence on ethical climate than other variables. On the one hand, if leader behavior conforms with ethical demand, the behavior of low-level employees would be more ethical because they regard leader behavior as a reference point (Calabrese and Roberts, 2002; Treviño et al., 2003). On the other hand, leaders are always given behavior criteria for ethical issues, and some of these rules would be published as institutional. These activities can improve ethical climate (Grojean et al., 2004).

Victor and Cullen (1988) proposed the five dimensions of ethical climate: “caring,” “rules,” “law and code,” “independence,” and “instrumental.” The inclusive leader pays close attention to the different demands and characteristics of the subordinates (Yukl, 2006). The influence of this close interaction between leader and members can be explained by social exchange theory. First, those who feel encouraged tend to share their opinion and knowledge, reinforcing knowledge sharing; second, frequent communication can create a “strong situation,” and this situation can show kindness and concern, similar to caring climate.

Unlike other dimensions of ethical climate that need to match a set of management activities, including organization routines and HR systems, caring ethical climate can be attributed to social processes. In the context of teamwork, leaders create an environment to share their ethical cognitions and values, shaping a caring ethical climate.

Hypothesis 3: Inclusive leadership is positively related to team caring ethical climate.

Caring Ethical Climate and Team Member Employee Voice

Caring ethical climate implies a shared manner of behavior in an organization (Cullen et al., 2003). The team members tend to share information and discuss the ethical issues directly, similar to that in a motivating environment. These activities can increase the willingness of the members to open up on issues concerning team development and put forward their own advice for work issues.

When team members are in a caring ethical environment, influence becomes obvious. Concern for the needs of others increases mutual trust within the team and emphasizes the importance of helping others. Employee voice becomes louder in this situation. The following hypothesis is thus proposed:

Hypothesis 4: Caring ethical climate can positively influence team member employee voice at the individual level.

Caring Ethical Climate and Team Performance

The ethical climate also exerts a positive effect on employee performance and can influence employee routines and norms in ethical issues. Such overall guidance provides good logic for employees in their job performance.

A caring ethical climate generally influences the prevailing thinking mode in a team. If everyone in the team cares about the welfare of others, the team members would tend to cooperate in complex tasks and effort and the efficiency would increase. The following hypothesis is thus proposed:

Hypothesis 5: Caring ethical climate positively affects team performance.

The association of leadership with employee behavior has been supported by a number of evidence. Inclusive leaders give team members norms to develop, encourage full communication, take additional responsibilities, and speak out. Leaders also have ability to create a new ethical climate. Employee voice is a type of self-determined behavior (Meyer et al., 2002), and ethical climate can subtly influence the thought mode of the employees. An inclusive leader can institute ethical guidelines and encourage members to learn the boundaries for their behavior and provide directions. Such an inclusive behavior is likely to promote shared attention by team members. We therefore propose:

Hypothesis 6: The positive relationship between inclusive leadership at the team level and employee voice at the individual level is mediated by caring ethical climate at the team level.

Team leadership shows a close relationship with ethical climate in a team, and leaders always play the critical role in shaping the thoughts and perceptions of team members (Schminke et al., 2005), In addition, leaders also exert additional enforcement through the institution and ethical codes. These effects have been cited in previous research.

Inclusive leaders can affect the perceptions of the team member by showing acceptance and respect. In the context of teamwork, the team member does not only care about the needs of others but also take into serious consideration the advice of the leader from different angles, all of which can substantially improve team performance. Accordingly, we posit a mediated hypothesis:

Hypothesis 7: The positive relationship between inclusive leadership and team performance is mediated by caring ethical climate at the team level.

Method

Sample and Procedures

The study was conducted among teams of enterprises from six major cities in China including bank, retail, law, oil, estate, and information technology. A total of 364 employees were administered at random from 116 teams participated in this study. To test our hypotheses, two separate survey questionnaires were designed with a view of minimizing single source of data bias. Questionnaire I was distributed to employees, it included measures of demographical variables, inclusive leadership and caring ethical climate. In addition, 3 months later, the direct supervisors of those employees received a second questionnaire in which they were asked to assess their subordinates on employee voice behavior and team performance. All respondents were given time to complete the survey during working hours and were assured full confidentiality. And they were instructed to completed surveys directly with the envelopes sealed to the researchers.

With the help of HR department, each of the questionnaire was coded, so that 3 months later, each supervisor still knew who he/she was rating. After the questionnaires were matched based on code, the response rate was 90.8%. The questionnaires of 35 employees were eliminated because they were incomplete or failed to conform with the requirements. The final sample included 329 employees from 105 teams with an effective recovery rate of 82%. The sample structure of the survey was as follows: in terms of gender, males were dominant, with 55.2% of the sample, and females comprised 44.8% of the sample; in terms of age, the youngest was 26 years old, whereas the oldest was 55 years old, with those in the 36–45 years comprising 46.7% of the sample.

Ethics Approval

An ethics approval was not required as per institutional guidelines and national laws regulations because there’s no unethical behaviors existed in the research procedures. We just conducted questionnaire survey and were exempt from further ethics board approval since our research did not involve human clinical trials or animal experiments. Also, the content of the questionnaire does not involve any sensitive or personal privacy or ethical and moral topics. In the first page of the questionnaire, information on consent procedures was included in information provided to participants and participants were notified that consent was to be obtained by virtue of survey completion. Meanwhile, we informed that participants about the objectives of the study and guaranteed their confidentiality and anonymity. The way to fill in the questionnaire is to take out the secret system, which can further ensure the rights of the people who answer the questionnaire. All the participants were completely free to join or drop out the survey. Only those who were willing to participate were recruited.

Measures

All the assessments in the current study were conducted in Chinese. We followed Brislin’s (Brislin, 1980) translation/back-translation procedure to translate the English-based measures into Chinese. Without exception, participants responded to all measures using a five-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree).

Inclusive Leadership

Team members were asked to indicate, using a 9-item inclusive leadership scale developed by Carmeli et al. (2010). The sample items were as follows: “The team leader is open to hearing new ideas,” “The leader is attentive to new opportunities to improve work processes,” and “The manager is available for consultation on problems.”

Caring Ethical Climate

We used the Ethical Climate Questionnaire developed by Victor and Cullen (1988) to measure caring ethical climates, which included seven items. The sample items were as follows: “The most important concern is the good of all the people in the team as a whole,” “Our major concern is always what is best for the other person,” and “In this team, people look out for each other’s good.”

Employee Voice Behavior

Employee voice behavior was measured using a 10-item scale adapted from Liang et al. (2012). The sample items were as follows: “Proactively develop and make suggestions for issues that may influence the team,” “Proactively suggest new projects, which are beneficial to the work team,” and “Raise suggestions to improve the team’s working procedure.”

Team Performance

Team leaders provided a comprehensive rating of the team performance by using a 6-item measure of effective performance developed by Barker et al. (2010). The sample items were as follows: “Members in this team can work effectively” and “Members in this team can achieve or over the work demands.”

Control Variables

We statistically controlled for demographic variables such as gender, age, education, and tenure in the team as control variables at the individual level because of their potential effects on the voice behavior of the team member (Wang et al., 2016). To assess the caring ethical climate and team performance at the team level, we also controlled for the gender, age, education, and tenure of the leader.

Analytical Approach

Data Aggregation

According to previous studies, data such as leadership style, ethical climate, and performance at the team level are often collected through individuals in the team and then integrated into the team level. Since inclusive leadership and caring ethical climate at the team level are rated by team members, the data need to be integrated. To support the aggregation, we calculated two intra class correlation indexes (ICCs) to determine whether aggregation of measures to group level was justified (Raudenbush, 2004). ICC(1) indicates how much of the proportion of the variance is explained by team membership (Hox and Mass, 2002), and ICC(2) indicates whether teams can be differentiated on the basis of the variable under consideration. We also used the interrater agreement (Rwg) to justify aggregation, with all mean Rwg values over the acceptable 0.70 cutoff (George and Bettenhausen, 1990). The ICC(1) and ICC(2) for inclusive leadership were 0.65 and 0.85, and the Rwg of 99% teams for inclusive leadership were ≥0.70. The ICC(1) and ICC(2) for caring ethical climate at the team level were 0.57 and 0.80, and the Rwg of 98% teams for the caring ethical climate at the team level were ≥0.70. They all met ICC(1) > 0.05, ICC(2) > 0.5, and more than 90% of the team Rwg ≥ 0.7. Taken together, these evidences support the aggregation of the leadership style, ethical climate, and performance ratings.

Descriptive Statistics

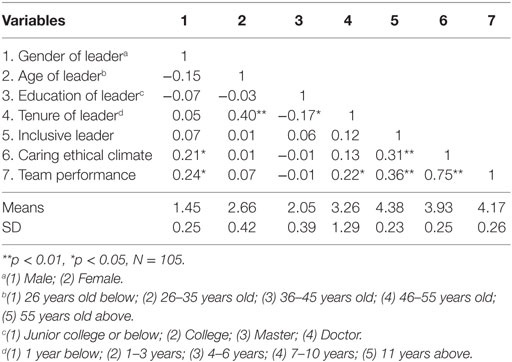

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics of the variables at the team level, and Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of the variables at the individual level. Inclusive leadership correlated significantly (p < 0.05) with caring ethical climate (r = 0.31; p < 0.01) and team performance (r = 0.36; p < 0.01), and caring ethical climate correlated significantly with team performance (r = 0.75; p < 0.01).

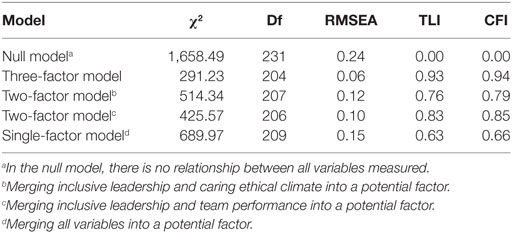

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

AMOS 20.0 was used to verify the confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) of variables at the team level to establish construct validity. Table 2 presents the CFA results. As shown, the data of the 3-factor model were in good fit [χ2(204) = 291.23, values of CFI ≥ 0.94, TLI ≥ 0.93, and RMSEA = 0.06]. The goodness-of-fit of this model is significantly better than the other factor models (2-factor model and single-factor model), indicating that the measurement has a good discriminant validity.

Hypothesis Tests

Regression Analysis

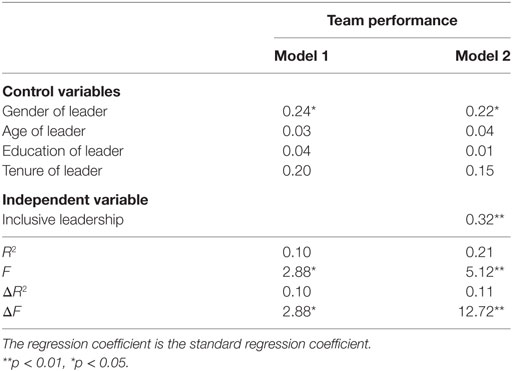

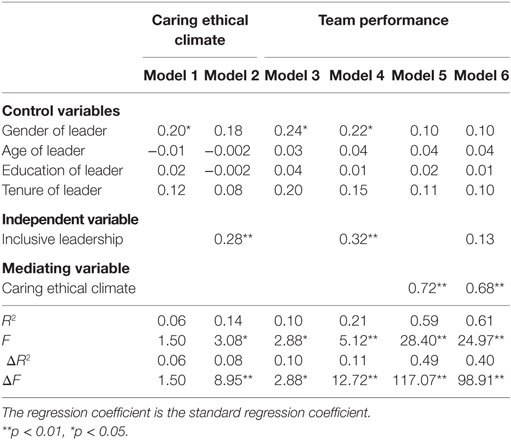

Table 3 presents the results of regression analysis in the demographic variables. Gender of leadership shows a significantly positive correlation with team performance (β = 0.24, p < 0.05). The F-values of each model were tested at the significance level of p < 0.01, indicating a good fit of the equation, and the inclusive leadership showed good explanatory power for team performance. The univariate correlations between inclusive leadership and team performance (β = 0.32, p < 0.01) provided a preliminary evidence to support Hypothesis 2, which states that inclusive leadership exhibits a positive relationship with team performance.

The control, independent, and mediator variables were entered in separate steps. As shown in Table 4, inclusive leadership was positively associated with both caring ethical climate (β = 0.28, p < 0.01, Model 2) and team performance (β = 0.32, p < 0.01, Model 4), supporting Hypotheses 3 and 5. As presented in Model 5, caring ethical climate was positively related to team performance (β = 0.72, p < 0.01, Model 5). In Model 6, after putting in the mediator variance of caring ethical climate, no significant relation between inclusive and team performance was found; however, the effect of inclusive leadership on team performance remains significant (β = 0.68, p < 0.01, Model 6), providing a preliminary evidence to support Hypothesis 7, which states that caring ethical climate totally mediated the relationship between inclusive leadership and team performance.

Hierarchical Linear Modeling

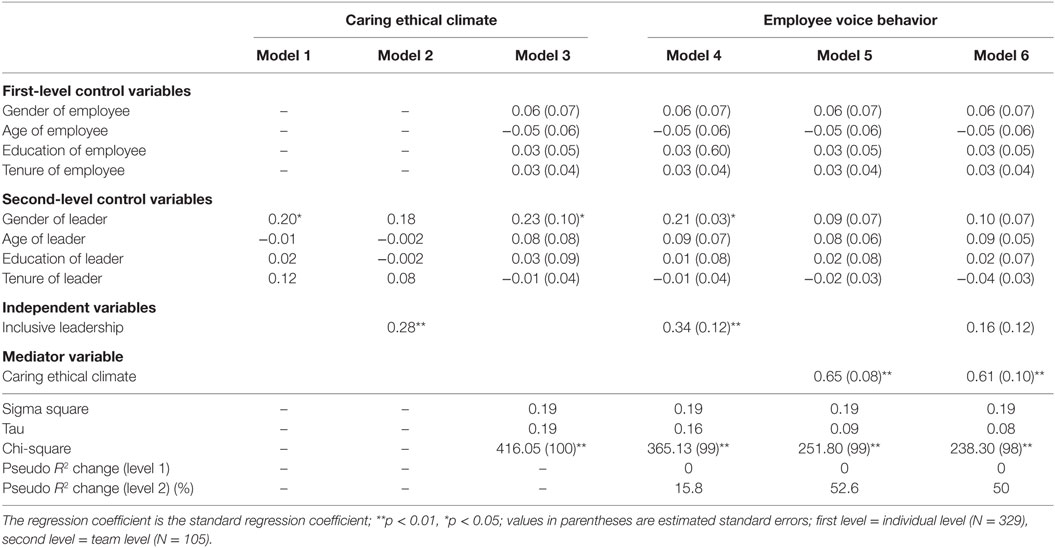

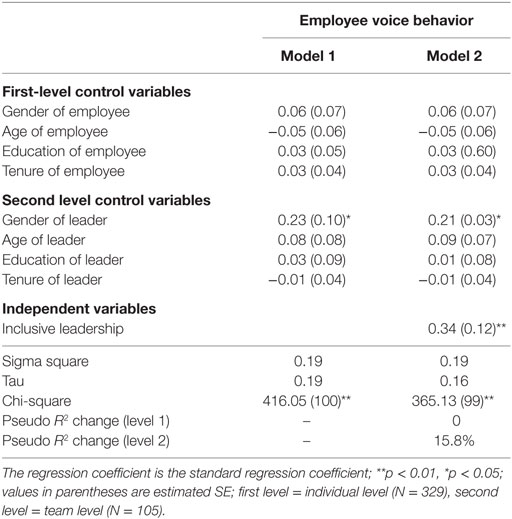

HLM6.02 was used to verify the hypotheses in this study. Hypothesis 1 proposed the main effect that inclusive leadership exerted a significantly positive effect on employee voice behavior. First, the control variables of the first and second levels, as well as the independent variable of inclusive leadership were entered in separate steps. As shown in Table 5, inclusive leadership was positively associated with employee voice behavior (β = 0.34, p < 0.01, Model 2), supporting Hypothesis 1.

Table 5. Results of hierarchical linear analysis of inclusive leadership and employee voice behavior.

Hypothesis 6 predicted that caring ethical climate mediates the relationship between inclusive leadership and employee voice behavior. According to Baron and Kenny (1986), full mediation is supported provided that the following four conditions are met: (1) the independent variable is significantly related to the mediator; (2) the independent variable is significantly related to the dependent variable; (3) the mediator is significantly related to the dependent variable; and (4) when the mediator is present, the relationship between the independent and dependent variables becomes non-significant. In support of Hypothesis 6, the results in Table 6 indicated the following: (1) inclusive leadership was positively related to caring ethical climate (β = 0.28, p < 0.01, Model 2); (2) inclusive leadership was positively related to employee voice behavior (β = 0.34, p < 0.01, Model 4); (3) caring ethical climate was positively related to employee voice behavior (β = 0.65, p < 0.01, Model 5); and (4) after entering caring ethical climate, the relationship between inclusive leadership and employee voice behavior became non-significant (β = 0.16, n.s., Model 6), whereas caring ethical climate was still positively related to employee voice behavior (β = 0.61, p < 0.01, Model 6). These results suggest that caring ethical climate totally mediates the relation between inclusive leadership and employee voice behavior. Thus, H6 is supported.

Discussion

The present study contributes to our understanding of inclusive leadership. At the individual level, we investigate and verify the mechanism of inclusive leadership on employee voice behavior on the basis of self-determination theory. At the team level, we investigate and verify the mechanism of inclusive leadership on team performance on the basis of social exchange theory. Prior research has examined many factors that affect employee voice behavior, such as psychological antecedents (Liang et al., 2012), HR practice (Conway et al., 2016), leaders’ positive affect (Liu et al., 2017), etc. While few studies investigated the relationship between inclusive leadership and employee voice behavior. The style of team leadership has an important role in the voice behavior of the team members (Bienefeld and Grote, 2014). We found evidence for the effect of inclusive leadership on employee voice behavior. Employees who seek for equality and mutual benefit relationship tend to exhibit behavior that is beneficial to team or organization, such as proposing suggestions (promotive voice) that can promote the operational efficiency of the organization and pointing out problems (prohibitive voice) that would be harmful to the organization, or to enhance team performance to continuously improve work efficiency and quality in order to repay the leader and the team.

Inclusive leadership can positively affect the caring ethical climate if team leaders treat employees inclusively, match words with deeds, express their ideas truthfully, listen to the opinions of others, improve their working methods consistently, and promote their ability to work. Team members tend to work for the overall interests of the team and take care of one another. The caring ethical climate significantly affects employee voice behavior. In the caring ethical climate at the team level, the team members are willing to help one another, unite as one, and offer positive advice to enhance efficiency, help colleagues, serve customers, and help the team improve. The caring ethical climate significantly affects and promotes team performance. In the caring ethical climate at the team level, the team members help one another, unite to reduce conflicts in the workplace, and promote team performance. From the point of view of the mediating role of caring ethical climate, team leadership indirectly affects employee behavior and team performance through the team ethical climate.

Theoretical Contributions

Overall, three contributions emerge. First, our theory and results help enrich inclusive leadership research. Inclusive leadership is a new leadership style, and few studies on the empirical study of inclusive leadership have been published locally. Our findings suggest that comparative studies on the role of other mediating variables should be conducted in the future to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of the tolerance mechanism of leadership on employee behavior and team performance and build a complete and systematic theoretical model.

Second, we found that inclusive leadership indirectly affects employee voice behavior and team performance through the mediating effect of the caring ethical climate. To encourage employees to speak up, leaders may need to directly invite them to do so by showing more specific, participative/open leadership behaviors (Tangirala and Ramanujam, 2012). Accordingly, the team members in our sample who are in the caring ethical climate are more willing to express their suggestions, which contribute to team improvement.

Finally, this study revealed the mechanism of positive cross-level effects of inclusive leadership on caring ethical climate, employee voice behavior, and team performance. Our results indicated that leadership can positively affect employee behavior through employee cognition. This outcome not only supported the conclusions in previous research but also elucidated the relationship between leadership style and employee voice behavior. Therefore, this study extends the theoretical vision of inclusive leadership, team ethical climate, and employee voice behavior.

Practical Contributions

Our findings provide three important contributions for human resource management and practice. First, the results of our study indicate that team leaders should be aware that high-quality inclusive leadership style can lead to higher levels of caring ethical climate so that they need to pay attention to leadership behavior. Team leaders should demonstrate ethical and proper behavior to their employees through their own individual behaviors and interpersonal interaction with employees. These behaviors should be reflected by consistent words and deeds, such as caring about employees, showing respect to employees, and helping employees develop their ability. In formulating strategic planning and management decisions, leaders should attach importance to the shaping of inclusive leadership style, enhance the sense of belonging of employees, and exhibit a high degree of loyalty. Employees will then be willing to contribute to the team or organization with suggestions and self-value.

Second, given the importance of the caring ethical climate for highly satisfactory team performance, our results suggest the value of actively focusing on organizational ethics. Organizational ethics should be taken into consideration as enterprises develop organizational development strategy and planning. Enterprises should adopt positive ethical policies and increase individual perception of the ethical environment of the organization. At the organizational level, ethical systems, such as corporate ethics policy, as well as ethics consultation, teaching, and training should be constructed.

Third, the consistent results that we found involving caring ethical climate as the mediating variable provide important practical contributions for positive employee behavior. Enterprises need to create caring ethical climate to help employees obtain a greater value and stimulate their higher-order needs. Employees receive emotional benefits such as creating positive emotions, gaining mental and physical pleasure, being assured of obtaining care, and feeling organizational warmth from caring ethical climate. Leaders should pay attention to their interaction with employees, encourage and help them carry out their tasks, enhance their sense of belonging, as well as create a harmonious and friendly ethical climate.

Limitations and Future Studies

As with any research, this study includes limitations that are worth noting. First, the study has a small sample size. Whether the sample size affected the results is difficult to determine. In the future, a study with a larger sample size for data analysis should be conducted. With time and resource constrains considered, the samples in this study reflect a narrow scope of enterprises. Future studies should select better enterprise samples across the country and attempt to reduce outcome deviations that are attributable to regional differences.

Another limitation concerns the generalizability of our results. In the conduct of the study, we found a significant difference in voice behavior between the financial and manufacturing industries. The team performance of high-technology enterprises and non-high-technology enterprises also reflect a significant difference. In the future, studies on the effect of leadership style on employee behavior and team performance can be evaluated among different industries for the conclusion to provide more practical contributions.

Finally, this study only validated the mediating role of perceived caring ethical climate, implying that other mediators that can reflect psychological cognition have yet to be excavated; similarly, this study only verified the positive effects of inclusive leadership on positive employee behavior such as employee voice behavior; the effects on other positive employee behaviors (such as feedback seeking behavior and organizational citizenship behavior) also need to be explored. Therefore, while future studies can further investigate the mediating effect of other variables, they should also explore the influence of inclusive leadership on driving positive action and outcome as well as conduct a cross-cultural comparative study of inclusive leadership.

Ethics Statement

This research is carried out by means of a questionnaire survey, the content of the questionnaire does not involve any sensitive or personal privacy or ethical and moral topics. The way to fill in the questionnaire is to take out the secret system, which can further ensure the rights of the people who answer the questionnaire. Therefore, there’s no need to apply for the permission of the ethics committee.

Author Contributions

Substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work: LQ and BL. Statistical analyses: LQ. Drafting the work: LQ and BL. Critically revising the manuscript: LQ and BL. All authors read and approved the final version.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Social Science Foundation “The research on leadership style, team ethical climate and employee deviant behavior in Chinese situation” (14BGL073); Major Program of Humanities and Social Sciences of Shandong University; and Youth Team Project of Humanities and Social Sciences of Shandong University.

References

Ancona, D. G., and Caldwell, D. F. (1992). Demography and design: predictors of new product team performance. Organ. Sci. 3, 321–341. doi: 10.1287/orsc.3.3.321

Anderson, N. R., and West, M. A. (1998). Measuring climate for work group innovation: development and validation of the team climate inventory. J. Organ. Behav. 19, 235–258. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1379(199805)19:3<235::AID-JOB837>3.3.CO;2-3

Barker, J., Tjosvold, D., and Andrews, I. R. (2010). Conflict approaches of effective and ineffective project managers: a field study in a matrix organization. J. Manage. Stud. 25, 167–178. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6486.1988.tb00030.x

Baron, R. M., and Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 51, 1173–1182. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

Bienefeld, N., and Grote, G. (2014). Speaking up in ad hoc multiteam systems: individual-level effects of psychological safety, status, and leadership within and across teams. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 23, 930–945. doi:10.1080/1359432X.2013.808398

Brislin, R. W. (1980). Translation and Content Analysis of Oral and Written Material. Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 389–444.

Calabrese, R. L., and Roberts, B. (2002). Character, school leadership, and the brain: learning how to integrate knowledge with behavioral change. Int. J. Educ. Manage. 16, 229–238. doi:10.1108/09513540210434603

Carmeli, A., Reiter-Palmon, R., and Ziv, E. (2010). Inclusive leadership and employee involvement in creative tasks in the workplace: the mediating role of psychological safety. Creat. Res. J. 22, 250–260. doi:10.1080/10400419.2010.504654

Conway, E., Fu, N., Monks, K., Alfes, K., and Bailey, C. (2016). Demands or resources? The relationship between HR practices, employee engagement, and emotional exhaustion within a hybrid model of employment relations. Hum. Resour. Manage. 55, 901–917. doi:10.1002/hrm.21691

Cullen, J. B., Parboteeah, K. P., and Victor, B. (2003). The effects of ethical climates on organizational commitment: a two-study analysis. J. Bus. Ethics 46, 127–141. doi:10.1023/A:1025089819456

Dionne, S. D., Yammarino, F. J., Atwater, L. E., and Spangler, W. D. (2004). Transformational leadership and team performance. J. Organ. Change Manage. 17, 177–193. doi:10.1108/09534810410530601

Farh, J. L., Hackett, R. D., and Liang, J. (2007). Individual-level cultural values as moderators of perceived organizational support–employee outcome relationships in China: comparing the effects of power distance and traditionality. Acad. Manage. J. 50, 715–729. doi:10.5465/AMJ.2007.25530866

George, J. M., and Bettenhausen, K. L. (1990). Understanding prosocial behavior, sales performance, and turnover: a group-level analysis in a service context. J. Appl. Psychol. 75, 698–709. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.75.6.698

Gladstein, D. L. (1984). Groups in context: a model of task group effectiveness. Admin. Sci. Q. 29, 499–517. doi:10.2307/2392936

Grojean, M. W., Resick, C. J., Dickson, M. W., and Smith, D. B. (2004). Leaders, values, and organizational climate: examining leadership strategies for establishing an organizational climate regarding ethics. J. Bus. Ethics 55, 223–241. doi:10.1007/s10551-004-1275-5

Hirak, R., Peng, A. C., Carmeli, A., and Schaubroeck, J. M. (2012). Linking leader inclusiveness to work unit performance: the importance of psychological safety and learning from failures. Leadership Q. 23, 107–117. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.11.009

Hirschman, A. O. (2011). Exit, voice, and loyalty: responses to decline in firms, organizations, and states. Soc. Forces 25, 47–56.

Hox, J. J., and Mass, C. J. M. (2002). Multilevel analysis. Vol. 28. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 785–793.

Hsiung, H. H. (2012). Authentic leadership and employee voice behavior: a multi-level psychological process. J. Bus. Ethics 107, 349–361. doi:10.1007/s10551-011-1043-2

Kearney, E., and Gebert, D. (2009). Managing diversity and enhancing team outcomes: the promise of transformational leadership. J. Appl. Psychol. 94, 77–89. doi:10.1037/a0013077

Liang, J., Farh, C. I. C., and Farh, J. L. (2012). Psychological antecedents of promotive and prohibitive voice: a two-wave examination. Acad. Manage. J. 55, 71–92. doi:10.5465/amj.2010.0176

Liu, W., Song, Z., Li, X., and Liao, Z. (2017). Why and when leader’s affective states influence employee upward voice. Acad. Manage. J. 60, 238–263. doi:10.5465/amj.2013.1082

Meyer, J. P., Stanley, D. J., Herscovitch, L., and Topolnytsky, L. (2002). Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: a meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. J. Vocat. Behav. 61, 20–52. doi:10.1006/jvbe.2001.1842

Mitchell, R., Boyle, B., Parker, V., Giles, M., Chiang, V., and Joyce, P. (2015). Managing inclusiveness and diversity in teams: how leader inclusiveness affects performance through status and team identity. Hum. Resour. Manage. 54, 217–239. doi:10.1002/hrm.21658

Mor Barak, M. E. (2013). Managing Diversity: Toward a Globally Inclusive Workplace, 3rd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Mossholder, K. W., Richardson, H. A., and Settoon, R. P. (2011). Human resource systems and helping in organizations: a relational perspective. Acad. Manage. Rev. 36, 33–52. doi:10.5465/AMR.2011.55662500

Nembhard, I. M., and Edmondson, A. C. (2006). Making it safe: the effects of leader inclusiveness and professional status on psychological safety and improvement efforts in health care teams. J. Organ. Behav. 27, 941–966. doi:10.1002/job.413

Ospina, S., Hadidy, W. L., Caicedo, G., and Jones, A. (2011). Leadership, Diversity and Inclusion: Insights from Scholarship. Vol. 3. Graduate School of Public Service, NYU Wagner, 3–30.

Rathert, C., and Fleming, D. A. (2008). Hospital ethical climate and teamwork in acute care: the moderating role of leaders. Health Care Manage. Rev. 33, 323–331. doi:10.1097/01.HCM.0000318769.75018.8d

Raudenbush, S. W. (2004). HLM 6: Hierarchical Linear and Nonlinear Modeling. Chicago: Scientific Software International.

Schminke, M., Ambrose, M. L., and Neubaum, D. O. (2005). The effect of leader moral development on ethical climate and employee attitudes. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process 97, 135–151. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2005.03.006

Shore, L. M., Randel, A. E., Chung, B. G., Dean, M. A., Holcombe Ehrhart, K., and Singh, G. (2011). Inclusion and diversity in work groups: a review and model for future research. J. Manage. 37, 1262–1289. doi:10.1177/0149206310385943

Suk, C. B., Hanh, T. B. T., and Byungll, P. (2015). Inclusive leadership and work engagement: mediating roles of affective organizational commitment and creativity. Soc. Behav. Person. 43, 931–943. doi:10.2224/sbp.2015.43.6.931

Svendsen, M., and Joensson, T. S. (2016). Transformational leadership and change related voice behavior. Leadership Organ. Dev. J. 37, 357–368. doi:10.1108/LODJ-07-2014-0124

Tangirala, S., and Ramanujam, R. (2012). Ask and you shall hear (but not always): examining the relationship between manager consultation and employee voice. Person. Psychol. 65, 251–282. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2012.01248.x

Treviño, L. K., Brown, M., and Hartman, L. P. (2003). A qualitative investigation of perceived executive ethical leadership: perceptions from inside and outside the executive suite. Hum. Relat. 56, 5–37. doi:10.1177/0018726703056001448

Van Dyne, L., and Le Pine, J. A. (1998). Helping and voice extra-role behaviors: evidence of construct and predictive validity. Acad. Manage. J. 41, 108–119. doi:10.2307/256902

Victor, B., and Cullen, J. B. (1988). The organizational bases of ethical work climates. Admin. Sci. Q. 33, 101–125. doi:10.2307/2392857

Wang, D., Gan, C., and Wu, C. (2016). LMX and employee voice: a moderated mediation model of psychological empowerment and role clarity. Person. Rev. 45, 605–615. doi:10.1108/PR-11-2014-0255

Wasserman, I. C., Gallegos, P. V., and Ferdman, B. M. (2008). “Dancing with resistance: leadership challenges in fostering a culture of inclusion,” in Diversity Resistance in Organizations, ed. K. M. Thomas (New York: Taylor and Francis), 175–200.

West, M. A. (2004). Effective Teamwork: Practical Lessons from Organizational Research, 2nd Edn. Oxford: BPS Blackwell.

Keywords: inclusive leadership, team ethical climate, employee voice behavior, team performance, cross-level analysis

Citation: Qi L and Liu B (2017) Effects of Inclusive Leadership on Employee Voice Behavior and Team Performance: The Mediating Role of Caring Ethical Climate. Front. Commun. 2:8. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2017.00008

Received: 24 February 2017; Accepted: 07 August 2017;

Published: 27 September 2017

Edited by:

Annamaria Di Fabio, University of Florence, ItalyReviewed by:

Gabriela Topa, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (UNED), SpainGary Lee Mangiofico, Pepperdine University, United States

Copyright: © 2017 Qi and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bing Liu, bGl1YmluZ0BzZHUuZWR1LmNu

Lei Qi

Lei Qi Bing Liu*

Bing Liu*