- Department of Communication, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, Spain

In spite of the well-documented links between global warming and the animal-based diet, human dietary choices have been only timidly problematized by legacy media in the recent decades. Research on news reporting of the connection between the animal-based diet and climate change shows a clear coverage deficit in traditional journalism. In order to reflect on the reasons for this failure, this paper discusses moral anthropocentrism as the human-supremacist moral stance at the roots of mainstream ethics and the climate crisis. Accordingly, the animal-based food taboo is defined here as our reluctance not only to change but to even discuss changing our food habits, a strong evidence that moral anthropocentrism is not addressed as a problem, which amounts to a type of denial. Through a literature review conducted on the most relevant comparative studies of deontological codes, this paper shows that codes of journalism do not escape moral anthropocentrism, and thus contribute to prevent journalists from stressing the relevant role diet plays in our ethics and sustainability efforts. The paper ends by suggesting ways to expand and update media ethics and deontological codes in journalism to dismantle both the taboo and the moral anthropocentric stance it is based on.

Introduction

Climate change denial refers to the stances that advocate against the evidence posited for human-induced global warming. This typically includes denial of any or all of these aspects: The warming of the earth and climate change (trend skepticism); the attribution to human activities as the cause of climate change (attribution skepticism); the severity of the consequences of climate change (impact skepticism); and the strong scientific agreement on the reality and human cause of climate change (consensus skepticism) (McCright, 2016). These dimensions, however, only refer to literal and interpretative types of denial, that is the denial of facts and of the logical consequences derived from facts—following Cohen (2001) categories of denial. There is a third type of denial which is actually much more spread. Many people and organizations do not deny either the facts, evidence or consequences of the current climate crisis yet they do deny the psychological, political or moral implications that conventionally follow (a dimension of denial that Cohen labeled as implicatory denial). This latter dimension directly impacts the solutions adopted (or lacking) by non-denialists and shows that rejection in the issue of climate change is much more complex than simply pointing at the right- wing denial countermovement alone. This paper aims to contribute to this realization by focusing on this latter type of denial–here defined as the denial of the moral anthropocentrism that prevails in society and prevents humans from adopting the important behavior changes needed to mitigate global warming. Amongst those changes, the animal-based diet outstands.

Since the publication of Livestock's Long Shadow by the Food and Agriculture Organization in 2006 (Steinfeld, 2006), an increasing number of governmental and non-governmental organizations and independent researchers have pointed at animal agriculture, and, by extension, animal-based diets, as a primary contributor to global warming (e.g., Bailey et al., 2014; Scarborough et al., 2014; Springmann et al., 2016; UNEP, 2018; UN News, 2018; IPCC, 2019). At the same time, over the last few decades, animal advocates, animal rights organizations, and many scholars and experts from a wide array of fields have revealed the cruelty and misery inflicted on non-human animals in industrial farms throughout the world, as well as the immorality of animal exploitation even on so-called “humane” farms (e.g., Singer, 1975; Regan, 1983; Gruen, 2011). Extensive and intensive animal exploitation have proven to be both ethically problematic and environmentally unsustainable.

Some counterarguments, promoted mostly by the agrifood lobbies and scientists linked to the industry (Stanescu, 2020), attempt to neutralize the problematic impact of animal agriculture on the environment. These include, for example, pointing out the need for animal waste for healthy agricultural environments and asserting the possibility of sustainable animal farming through, for instance, improving waste management and food technology. Regarding the first argument, it has long been known by farmers that it is possible to grow food with plant-based fertilizers alone, a practice already applied even at current industrial-scale agriculture (Philpott, 2013). Green manure is very ancient indeed (Warman, 1980). On the other hand, the argument for a clean exploitation of other animals implies blind faith in a future technological solution which may never arrive and leaves unsolved the ethical issue of exploiting sentient beings. Only in vitro meat seems to allow for a real abolition of animal agriculture as we know it today, but so far it is very unclear whether this is really a sustainable or ethical option (Mattick et al., 2015; Lynch and Pierrehumbert, 2019). Likewise, shifts from one type of animal-based food to another (such as shifting to poultry and aquaculture) fall into the same problem as moving from intensive to extensive systems; once these are analyzed in depth, it is fairly clear that they are not a solution, but rather a part of the problem. They have more drawbacks than benefits, extensive systems including, for example, a tremendous impact on deforestation and land degradation (Henders et al., 2015; Thorstad et al., 2015; Yuan et al., 2019).

Since humans don't need animal protein to thrive—actually, the opposite seems to be the case, because animal-based diets are linked to major human diseases (c.f., Chang et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2018; Bradbury et al., 2019; OMS, 2019)—a change of diet has become one of the most fundamental challenges humans face during twenty first century.

However, in spite of the connection between climate change and our food habits, the animal-based diet has been only rarely and timidly problematized by the leading institutions in society, including legacy media with the largest audiences. Research on the news media representation of the links between the animal-based diet and global warming unveils significant newspaper coverage deficits (Neff et al., 2008; Kiesel, 2009; Bristow and Fitzgerald, 2011; Friedlander et al., 2014; Almiron and Zoppeddu, 2015; Olausson, 2018; Moreno-Cabezudo, 2019). It seems that the news media have been as uninterested in making a connection between climate change and animal agriculture as they have been in covering the connection between ethics and the consumption of other animals' flesh and fluids. This has only started to change in the last few years, largely due to multiple scientific reports confirming the impact of animal-based diets on the environment, including further validations from different branches of the United Nations which the media have been compelled to report. The extent to which this is altering the legacy media discourse is yet to be researched, but some related studies point at a slow progression. For instance, the plant-based diet, which is both implicitly and explicitly identified by research as a crucial factor in the mix of solutions needed for the reduction of anthropogenic global warming, is not receiving objective and sufficient news coverage or is even ridiculed or criminalized according to the limited research conducted so far on this topic (Cole and Morgan, 2011; Masterman-Smit et al., 2014; Cole, 2015; Ulmane, 2020).

This paper names this incongruency “the animal-based food taboo,” a denial of the possibility of a full replacement of animal-based food by plants. I call it a taboo since this possibility is considered unworthy of discussion or unacceptable by a large number of humans, mostly for cultural and economic reasons. It is no news that global warming mitigation is severely limited due to ideological reasons linked not only to habits and symbolic values but also to economic interests. The fact that some ideas—particularly the neoliberal set of ideas—are behind the main causes of anthropogenic global warming has been extensively addressed by the group of scholars analyzing the denial countermovement in the US since the 1990's (the “denial machine” as coined by Dunlap and McCright, 2015). However, the set of ideas that the animal-based food taboo is based on cannot be explained solely by the neoliberal triumph. As history shows, neither capitalism nor modern times have the monopoly of environmental destruction and lack of moral consideration for other species (Peterson, 1993/2019; Shapiro, 2001; Nibert, 2013; Harari, 2014). Ethicists have consistently related this reality with moral anthropocentrism, an issue that is largely left untouched in mainstream analyses of anthropogenic climate change. This is considered elsewhere a sort of “ideological denial,” that is a denial not only of the scientific evidence for anthropogenic climate change, but also the denial of the human-supremacist ideas that are at the roots of the problem (Almiron, 2020).

The animal-based food taboo is certainly weaker today compared to the past. A number of organizations, alternative media and citizens have clearly abandoned it—certainly have around 75 million vegans that are estimated existed in the world (Veganbits, 2020). However, this is not the prevalent stance amongst the political, social and economic elites with which the old media is interconnected.

As shown by the previous mentioned research on newspapers, legacy news media coverage has contributed extensively to this denial by persistently underreporting or misreporting not only the links between climate change and animal exploitation for food, but also, and mostly, by adopting a speciesist approach—giving priority to human interests solely—in the coverage of how humans treat nature and other animals in general (c.f., Molloy, 2011; Almiron et al., 2016). In this paper I suggest that news media ethics, particularly Western media codes, has contributed to this failure in reporting because they replicate the moral anthropocentric stance. Considering the problems attached to the animal-based diet, it follows this is a counter-productive, narrow media ethics approach that needs to be overcome.

To discuss this view, this paper is structured as follows. The first section examines what moral anthropocentrism is as well as its role in the ideological denial of climate change. Second, a review of the major tenets of news media codes is conducted to identify their core ideas, including their moral anthropocentric roots anchored in some Enlightenment ideals. Third, it is argued that if moral anthropocentrism is to be rejected, then it follows that the ethics of communication in general, and journalistic ethics in particular, need to update their moral boundaries, and that this would have a major net impact on climate action. Finally, to this end, a few specific ideas for an expansion and reinterpretation of the current codes are suggested.

In short, this paper discusses how Western news media codes—and the main tenets of media ethics they reflect—need to be reinterpreted and expanded if we seek to promote effective climate action. The perspective of the author is grounded in animal ethics and critical animal studies, and thus is illuminated by a critique of human supremacism and speciesism—a stance not allocating full moral consideration to non-human species. Since current global warming is due to human activities, this perspective may be of help because it focuses not on fixing the consequences of our activities but on the ideological roots of these activities, as well as on promoting a change based upon principles, rather than upon pragmatical, self-serving concerns.

Moral Anthropocentrism and the Ideological Denial of Climate Change

A number of scholars have defined the behavior the human species exhibits on the planet as supremacist since, for millennia, both consciously and unconsciously a majority of humans have abused all living things on the planet as if all life on Earth were here just to fulfill humans. For instance, a vast majority of humans consider that the growth of human population on the earth is not only good, but a human right,1 even if as a consequence other animals on the planet are left without a proper habitat to live in, or in some cases, no habitat whatsoever. The majority of humans do not view themselves as supremacists,2 yet they behave in as such when they accept premises such as the previous one, thereby putting humans and human interests or preferences above anything else.

In the context of ecology, the critique of human supremacism on Earth has typically been associated with environmental ethics because of the claim this branch of philosophy makes against anthropocentrism. However, although eco-centrism acknowledges moral consideration of the biosphere, this view fails to address the full moral consideration of other animals. This failure is consistent with the core values of environmental ethics, which are mostly anchored in the Land Ethics approach (Leopold, 1949), devoted to preserving the “integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community” (Callicott, 2014, p. 66). Land ethics has been universally applied to the management of the Earth by humans and entails the practice of culling individuals of certain species to preserve an alleged balance in ecosystems. Precisely because of this lack of full moral consideration of other animals, environmental ethics has been unable to develop a critique of industrial farming until very recently.

Not allocating full moral consideration to other animals is the main trait of moral anthropocentrism. Because the reason of doing this is species membership, moral anthropocentrism is also speciesist. Not belonging to the homo sapiens species is the main motive of discrimination (though speciesism also means giving different species different values according to humans' needs or preferences; for instance, dogs are given a higher moral consideration than are pigs or worms).

This has been formulated in a variety of ways by a number of animal ethics and animal rights scholars who share the conviction that moral anthropocentrism is incompatible with the principle of equal consideration of interests (for a literature overview see https://www.animal-ethics.org/speciesism-bibliography/). This principle claims that one should give equal weight in one's moral decision making to the like interests of all those affected by one's action (Singer, 2011). If this is true, then species is as irrelevant as race or sex to the evaluation of the interests of the non-human beings involved in our actions and decisions. If we do not agree with this latest statement, because we think the human species makes a difference that race and sex do not, this is tantamount to applying a morally anthropocentric and speciesist logic. However, this logic has been proven to be ungrounded. As Faria and Paez summarize:

None of the usual attributes used to draw a moral divide between all humans and all non-humans succeeds in its task, since none is possessed by all humans, or lacking in all non-humans. Whatever the attribute that grounds full moral consideration might be, if it is to include all human beings, it must include non-humans as well. Because what matters for moral reasoning is determining who can be affected by our actions, such attribute is sentience. Therefore, all sentient beings, both human and non-human, are to be equally morally considered (Faria and Paez, 2014, p. 102).

These and other authors acknowledge that decision-making should be inspired by major considerations rather than circumstantial ones such as race, sex, or species. In this regard, as mentioned in the previous quote, one major attribute widely accepted as salient for moral reasoning is sentience, that is “whether a being can be affected by a certain action or event and, thereby, harmed or benefited by it” (Faria and Paez, 2014, p. 101). Note that, accordingly, sentience is not the mere capacity to perceive stimuli or react to some action but the capacity to be affected positively or negatively, that is the capacity to have experiences.

Because the belief in human superiority has proved to be so dramatically damaging for life in the planet, it follows that adopting a critical standpoint toward it can also be of benefit for addressing the current climatic emergency. This of course includes the dismantling of the taboos, such as the animal-based food taboo, that prevent us from changing habits. However, even though the IPCC reports implicitly identify moral anthropocentrism as a cause of anthropogenic climate change, it has typically been excluded from its pack of solutions until very recently (IPCC, 2019). However, it is important to note that the UN has so far addressed the dietary shift as a mere individual choice rather than a structural urgency to replace animal agriculture business (Centre for Biological Diversity, 2018).

Oddly enough, this ideological core denial is a trait shared by both climate change deniers and climate change advocates. On the one hand, organized climate change denial has rejected not only the anthropogenic causes of climate change, as well as its seriousness, but also the idea that capitalism, at least in its current form, is unsustainable. This stance not only refutes science, but also any need for structural change. Underneath this rebuttal is the approval of current capitalist values, including the supremacist idea of having a right to exploit all life in the planet as a commodity (Jacques, 2012). On the other hand, although climate advocates (e.g., environmentalists) seem to be much more aware of the system's failures, they typically neglected to address the core issues challenged by the IPCC's diagnosis, including the need to change our diet. Traditional environmental NGOs have only very recently started to address the issue but have done so without questioning the speciesist view underlying it and thus neglect to challenge the core ideas that are at the root of global warming. The Greenpeace campaign “Less meat, more veg now!” (https://lessismore.greenpeace.org/) is a good example of this with its call for a mere reduction in consumption of meat rather than a shift toward a full plant-based diet, which would be the logical recommendation if the planet's health were the priority rather than human dietary preferences. Also, the support a majority of green organizations keep providing to extensive animal farming reveals that the animal-based food taboo remains rooted in them—since extensive animal agriculture has clearly been pointed out by research as part of the environmental problem, not of the solution (for its need of vast amounts of land to be devoted to pastures, its impact on deforestation, land degradation and loss of biodiversity, amongst other problems, in spite of its reduced on-farm fossil fuel use, see references in the Introduction).

To summarize the point made in this section, although a large number of humans reject supremacism of any type on theoretical grounds, an overwhelming majority of homo sapiens on the planet effectively have moral anthropocentrism as their vital compass. The logic conclusion is that a large number of humans are in denial about their core ideas. Because of this ideological denial, choices such as animal-based diets are considered not fit for discussion and so become taboo. Any discussion of their replacement is considered problematic despite the fact that such behaviors are contributing massively to the planetary collapse and must be urgently reconsidered for the benefit of all. In the next sections I examine how Western media codes, as a synthesis of the main tenets of media ethics, prevent (or at least do not help) journalists from expanding their circle of compassion toward non-human animals. This produces an ethical bias that it may contribute to neglect the relevant role diet plays in our ethics and sustainability efforts.

Journalistic Codes and Media Ethics

Media ethics addresses issues of moral principles and values that apply to the role, content and behavior of the media. Having developed in parallel with the emergence of newspapers, the ethics of journalism is the strongest branch in media ethics and became a baseline for the rest of media ethics that followed.

Normative theories of public communication have traditionally allocated a number of roles to news media and journalism. Classical examples are Four Theories of the Press (Siebert et al., 1956)—which introduced the authoritarian, libertarian, social responsibility and Soviet Communist models—and Normative Theories of the Media (Christians et al., 2009)—which discusses the monitorial, facilitative, radical, and collaborative roles of the media. More recently, Media Ethics and Global Justice in the Digital Age (Christians, 2019) includes reflection on the ethics of being, truth, human dignity, and non-violence. In all cases media ethicists have attempted to clarify what is and what should be expected of the media.

However, the standpoint from which media ethics was established, as well as scrutinized, has been rather homogeneous, inasmuch as media and ethical reflection on it has largely been a concern born from classical liberalism within Western capitalist societies. This is why the field has been dominated by a rationalist view that has received criticism mainly because of its strong reliance on prescriptions and general rules. For instance, Clifford Christians criticizes what he calls the “fallacy of rationalistic ethics” in media, the linear and dualistic normative ethics constrained by the rationalism of the Enlightenment, a “Eurocentric ethics of rationalism” that “produces rule-ordered abstractions” that have proven incapable of addressing the complexities of our time (Christians, 2019, p. 107). This directly refers to the insufficiency of codes of ethics and the individualist rationalism and utilitarianism that have historically dominated codes' emergence and media ethics in general. This dominion has actually had an impact on language since, as Christians and Traber noticed more than two decades ago, what we call codes of ethics should indeed be called deontological codes (Christians and Traber, 1997, p. 27)—deontology, or deontological ethics, is just one approach to ethics.

On paper, journalism's codes gather general principles of ethics useful for the professionals. The majority of them revolve around common elements (including the principles of truthfulness, accuracy, objectivity, impartiality, fairness and public accountability) while others also include other topics, as for instance mentions on how to avoid discriminatory coverage. The final aim is to assist journalists with ethical dilemmas and by defining acceptable practices. However, their influence is relative and depends on the corporate and professional culture. As Christians et al. (2009) put it:

The most important influence in the ethical formation of professional communicators is socialization into the accepted culture of the profession. If a culture is ethically demanding, then norms will be important. Codes of ethics are merely the formalization in public, written, and consensual form of the most important general principles of the professional ethos. These codes are formulated, adopted, maintained, and enforced by professional associations, and they generally mean only what the associations want them to mean (p. 69).

Certainly, a major criticism received by deontological codes is that they are purely cosmetic and rhetoric public relations tools (Himelboim and Limor, 2010). Still, it is also true that they are the most important factual outcome of social responsibility theory, which has successfully ingrained in communication ethics the idea that not only the media has the moral obligation to consider the needs of society in journalistic decision-making, but that this must be done to avoid external regulation and with the aim of producing the greatest good. Therefore, codes may be considered both tools for improving the work of journalists and a way for professionals and media companies to publicly show they are concerned about ethics, at least theoretically.

Although there had been media codes of ethics for decades before the II World War, the idea of codes serving as accountability tools for journalists, which helped maintain media independence from regulators while reinforcing the democratic role of the media, can be considered a legacy of the Hutchins Commission on Freedom of the Press created in the United States in 1947. The impact of its set of codes reflects the general controversy surrounding journalistic ethical codes in general. As Pickard (2015) remembers:

Despite finding fundamental flaws in the commercial press's structure and content, the Hutchins Commission set codes of professionalization that would, ironically, help shield the industry by elevating an intellectual rationale for self-regulation under social responsibility—a framework that was easily co-opted to serve a libertarian agenda (p. 194).

The debate around the ultimate influence and use of codes of ethics for journalists is long-standing and will certainly continue. However, codes have typically been considered “a most valuable resource for research about values behind journalistic practice” (Nordenstreng, 2008, p. 64). As “collections of dos and don'ts” of professional activity, codes in theory reflect the broader ideals of professional journalism across societies, the media and journalistic organizations (Himelboim and Limor, 2010, p. 76). Correspondingly, codes are useful for our purposes in this paper in that they allow us to observe to what degree journalistic values are capable of addressing and challenging moral anthropocentrism.

Journalistic Codes and Moral Anthropocentrism

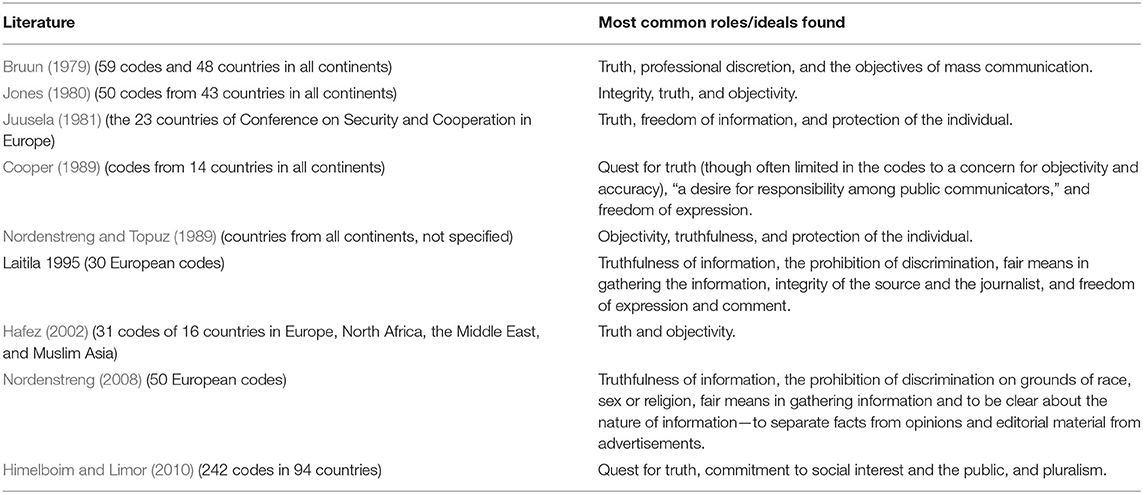

Research on compared media codes of ethics started in the 1970's and overall is scarce, in spite of the important boost given to the field by scholars like Kaarle Nordenstreng; particularly, studies that examine all existing codes are very few. On one hand, comparative works are difficult due to the lack of unified, effective measurement tools. On the other, changes in codes are rare, what extends the validity of past research. For this paper, I conducted a literature review and selected nine works that include benchmark comparative studies about the values embedded in journalistic codes. In spite of a prominence of European codes, altogether these works examine codes from a large number of countries in all five continents.

As can be noted in Table 1, the first major comparative work is from 1979 while the latest one is published in 2010 (though with data from 2006). I could not find any relevant international comparative work centered on the values promoted by codes of journalism after this date. A number of studies actually confirm the lack of major changes in codes across time. Nordenstreng, in his examination of 50 codes in Europe in 2008, noted that the standards have remained more or less the same compared to 1995 (Laitila, 1995). In 2015, Díaz-Campo and Segado-Boj (2015) examined 99 codes from around the world to see whether Internet and Communication Technologies (ICTs) had had any impact on codes. They found only 9 mentions to ICTs. Therefore, as Nordenstreng (2008) noted for Europe, it seems that codes are well-established and solid ideals that, in spite of regular updating, remain rather stable in their core tenets.

The analysis of the selected works provides, in general, a rather homogenous landscape. Table 1 summarizes the most common roles/ideals found by the authors. As Table 1 shows, values such as truthfulness, objectivity, and freedom of expression are some of the most commonly found in deontological codes of journalism everywhere.

Among the literature reviewed, Himelboim and Limor (2010) study stood out as a cornerstone, far-reaching research of journalistic codes. In their work, the authors analyzed 242 codes of ethics in 94 countries—including national organizations (59% of all codes analyzed) and newspapers (24%)—and provided two main conclusions. First, that as a reflection of the professional values and ideals held by media organizations, codes “fail to reflect some of [the media's] most fundamental expected roles in society.” Second, that this happens regardless of the geopolitical context (Himelboim and Limor, 2010, p. 89). Their research answered three basic questions that deserve to be detailed for the relevance of this work.

The first research question was related to the roles that codes of journalistic ethics address and to how they do this. They found that media and non-media organizations prefer to focus on roles low on the involvement (toward the public) and adversarial (toward loci of power) dimensions. The most commonly found roles toward the public were “distributing information” (48%) and “commitment to social interest” (40%), as contrasted with the low presence of roles such as “mobilizing public opinion” (5%), becoming involved in the community” (2%), and “suggesting solutions to social problems” (1%). Adversarial roles were rarely presented and the most common was investigative—“seeking/pursue truth” (47%), as contrasted with roles such as: “serve as media watchdog” (9%), “protect public rights” (7%), and “protect against information distortion and manipulation” (6%). Of special interest here was the role “commitment to the environment,” which was one of the least found in codes (1%), while any mention of individuals of any non-human species was completely absent.

These results allowed the authors to state that, according to deontological codes, the role of journalists and media organizations is neutral since they give priority to simply disseminating information. Himelboim and Limor (2010, p. 83) pointed out that

codes rarely address duties associated with civic journalism, such as becoming involved in society or directing and affecting social processes. Furthermore, the over- all absence of the role of “providing a stage for different voices in society” can provide some support to Picard (1985) claim that the media have abandoned this role … findings can support the notion that press and government should not be rivals—at least not in democratic countries.

The second research question in Himelboim and Limor (2010) study aimed to discern whether the different role perceptions originated from national characteristics, that is geopolitical and political-economic variables. The answer was negative: their findings show that codes exhibit no marked differences based on independent geo-political variables.

The third research question attempted to differentiate in role perception according to organizations (to the type of organization formulating the code). Here a difference was found, “the codes of newspapers and media chains addressed the social role of journalism toward both society and loci of power much less than did critic codes.”

Himelboim and Limor's results showed a total contradiction with the media as “the fourth estate” cliché:

Codes rarely reflected related social roles, such as the watchdog function or fighting corruption. Media organizations and institutions, particularly in Western countries, declared a more unified approach, emphasizing neutral roles and rarely addressing the more involved roles in their communities and society. These gaps raise the concern that some of the fundamental roles of media in society are disintegrating not only in practice, as many media critiques have suggested, but also as objectives (Himelboim and Limor, 2010, p. 88).

As Himelboim and Limor also note, whether a more adversarial or a greater involvement are desired roles for news media is a highly controversial topic amongst journalistic communities at both the professional and academic levels. To discuss this further is beyond the scope of this paper, but what the current codes reflect is useful to our purpose here. Current codes around the world appear to largely be based on values such as detachment and not confrontation, rather than surveillance, enhancement or denunciation. With such an emphasis, it is no surprise that neither moral anthropocentrism in general nor any particular behavior attached to it in particular are problematized by media coverage, since doing so would mean confronting the status quo, which is incongruous with the codes' promotion of neutrality. Thus, the lack of commitment to directing and affecting social processes and the lack of interest in serving as a stage for different voices are two of the elements that likely most contribute to the lack of interest by the media in problematizing the links between climate change and animal agriculture, and the links between ethics and our diet.

From this, it follows that journalistic codes represent agreements on the basis of lowest common denominators, always behind societal changes, neither ahead of them nor useful tools for challenging societal wrongs. Their stressed neutrality resonates with the ideology of neutral instrumentalism attached to the digital age, the idea that the information society is based on technological advances that are neutral or value free. According to Christians (2019), this idea has led to the dominance of technical modes of thought in society over the human orders of politics, ethics, and culture, which appear to have weakened morality. This way, through the fulfillment of technical routines (truth, integrity, objectivity…) it is assumed that social commitment, whatever this means, is pursued. However, neutral principles only rarely transform the status quo, since they are not useful for dismantling specific taboos and myths. The liberal approach that dominates current codes is therefore as blind to human bias as moral anthropocentrism is.

It is also of course of interest to look at the values promoting commitment and change in the codes. These are less emphasized and have a much lesser presence but can also tell us about the codes' capacity to challenge society. Nordenstreng and Topuz (1989) particularly mention the birth at their time of a new generation of ethical principles that they identified as being incorporated in the codes, including: the development of human rights; securing the respect for a variety of cultures, philosophical, and ideological convictions; defending peace and security; avoiding aggression and war propaganda; obtaining disarmament; forbidding racialism; fighting against colonialism; and contributing toward international understanding. These principles are fully aligned with what we can currently find, for instance, in the Global charter of ethics for journalists (1954) produced by the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ), a global union federation of journalists' trade unions—the largest in the world—that represents more than 600,000 media workers from 187 organizations in 146 countries. In the IFJ's code, there is a single article not related to journalistic routines and clearly promoting involvement toward the public and challenging wrong social behaviors:

Article 9. Journalists shall ensure that the dissemination of information or opinion does not contribute to hatred or prejudice and shall do their utmost to avoid facilitating the spread of discrimination on grounds such as geographical, social or ethnic origin, race, gender, sexual orientation, language, religion, disability, political, and other opinions.

Nordenstreng and Topuz (1989) findings and Article 9 of the IFJ's charter, as is the case with all similar articles in journalistic codes, reflect the ideas that animated the human rights movement developed in the aftermath of the Second World War, which culminated in the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Paris by the United Nations General Assembly in 1948. The true forerunner of these ideas is the European Enlightenment (especially as found in the political discourse of the American and French revolutions), but it is not until the latter half of the twentieth century that the modern human rights movement emerges due to the horrors of war and human violence that took place in the first half of that century.

These Enlightenment ideas brought about a radically positive transformation for humanity. They undermined the authority of absolute monarchs and religion, focused decision-making on reason, and paved the way for the political revolutions of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. These revolutions promoted ideals such as liberty, toleration, and fraternity, and gave birth to liberalism, socialism, and the concept of human rights. The spreading of the universalist and egalitarian ideals they encouraged is at the core of the development of not only modern civil rights but also of the increasing consciousness of the need to avoid harming nature and the rest of species that inhabit the planet with us. That is, many of the current (although still minoritarian) claims against moral anthropocentrism that underlies human “progress” have their roots in, as well as opportunity to further develop, the Enlightenment ideals.

Paradoxically, however, the secularism and scientific revolution of Enlightenment also led to new modalities of domination (such as colonialism) and to an anthropocentric humanism that became a dominant tradition in Western countries, which was quickly followed by non-western cultures. As non-speciesist critical scholars Weitzenfeld and Joy summarize, the humanism promoted by the Enlightenment is anthropocentrist “due to its ideological commitment to conceptualizing human being over and against animal being, and privileging human consciousness and freedom as the center, agent, and pinnacle of history and existence” (Weitzenfeld and Joy, 2014, p. 5). As critical animal studies scholar Carl Bogg remembers, Enlightenment thinking came “to attach to humans a range of qualities identified as unique to the species—thought, reflection, morality, planning” (Bogg, 2011, p. 75). This for instance led to the promotion of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights by invoking species hierarchy, as Will Kymlicka remembers: “Human beings are owed rights because of our discontinuity with and superiority to animals” (Kymlicka, 2018, p. 763). Nowadays science has confirmed that most of these allegedly superior traits are possessed to varying degrees by members of other species as well, while we, the humans, also have varying degrees of them and are missing or have undeveloped traits other species possess—it turns out that the human species is cognitively and sensorially impaired compared to many other species. But the collapsing of the human-superiority fallacy as an idea did not diminish the strong human-animal dualism in practice, launched during the age of Enlightenment but actually born during the Ancient Greek time, with philosophers as Protagoras proclaiming “man is the measure of all things.”

Theodor Adorno and Marx Horkheimer, two of the most prominent social research thinkers of the Frankfurt School, and very severe critics of the culture industry created by capitalism under the rationality of Enlightenment, targeted this anthropocentric bias of humanism in their work and provided an analysis that proves useful for analyzing media ethics.

As Gerhard (2011, p. 142) remembers, Adorno and Horkheimer believed the ethical treatment of animals and humans to be related. In their work, especially the Dialectics of Enlightenment, they discuss how humans' relationship to nature and to other animals forms part of the larger ideology of domination. Adorno and Horkheimer provide conceptual tools for critical theory that are relevant for critical media studies (and for our thesis here of fighting against climate change by means of unveiling and neutralizing moral anthropocentrism). Drawing upon these ideas, John Sanbonmatsu, for instance, remembers that “[c]ommodity fetishism and privatization destroy human and human-non-human solidarity, estrange us from nature, and compromise and weaken democratic institutions, stripping all living beings of any intrinsic value other than one—surplus value (commercial profit)” (Sanbonmatsu, 2011, p. 31). Dennis Soron, for its part, applies the idea of fetishism to meat consumption and marketing: “[F]etishism both constricts the meaning of meat by bracketing off the context of its production, and dramatically expands it by enabling marketing and other cultural practices to infuse the commodity with new values and connotations” (Soron, 2011, p. 62).

In the Dialectics, Horkheimer and Adorno also state: “Throughout European history the idea of the human being has been expressed in contradistinction to the animal. The latter's lack of reason is the proof of human dignity” (Horckheimer and Adorno, 2002, p. 203). John Sanbonmatsu deciphers this quote for readers unfamiliar with the German theorists:

the early modern period saw the rise of a secular-scientific worldview that “disenchanted” the living natural world and reduced all living beings—including human ones—to the status of mere things to be controlled. The humanist faith in “the dignity of man”—the principle from which all modern progressive movements eventually evolved—was from the start drawn in contradistinction to the perpetually degraded and irrational animal (Sanbonmatsu, 2011, p. 25).

Human dignity, exceptionalism, and perfectionism are considered by scholars critical of moral anthropocentrism as the three main premises that support the hierarchy of anthropocentric humanism (Sanbonmatsu, 2011; Nocella et al., 2014). While human dignity has reached deontological codes of journalism literally as such, the other two premises—human exceptionalism and perfectionism—are not explicitly proclaimed in codes but they are implicit inasmuch as there is a total lack of consideration of humans' treatment of other species (not to mention an omission of respect for nature). Codes of journalism are, first, exclusively concerned with humans (either the journalists or the humans covered by them) and, second, and bizarrely, not concerned about all human deeds: the ethics of human treatment of non-human life is almost absent in the case of nature, and totally absent in the case of our treatment of other species in particular.

Therefore, it seems that deontological codes of journalism have inherited both the progressive values and rights promoted by the Enlightenment to alleviate social injustice but also the anthropocentric view that became dominant. Unfortunately, they miss the progressive ideals also triggered by Enlightenment toward the rest of non-human life in the planet. In short, codes align with the dominion of moral anthropocentrism deployed as speciesism and a fetishism for technology and reason. Because of this, deontological codes can neither identify nor neutralize the anthropocentric bias in society. They originate in and implement the same bias.

Discussion: The Urgent Need to Update Deontological Codes of Journalism

It is well-known that the women rights movement introduced the metaphor of putting on feminist glasses in order to help recognize sexism in everyday life. Likewise, it can be claimed that antispeciesist glasses are needed for recognizing moral anthropocentrism in media ethics and society. As with sexism, we may stay blind to moral anthropocentrism in spite of, or because of, being immersed in it. Of course, the question of how to incorporate the antispeciesist gaze in journalistic deontological codes, that is, a gaze that does not discriminate against some sentient beings merely because of species membership, might be addressed in different ways. One way could be by adopting the essence and ideas precisely missing from the mindset that produced the codes. It can be argued, then, that the lack of moral consideration for the individuals of other species and the belief of an alleged human superiority can be neutralized by, I suggest, interspecies justice and a feminist interspecies ethics.

In speaking of interspecies justice, I here refer to the moral equality and shared set of rights suggested by Cochrane's theory of global interspecies justice (Cochrane, 2018). Cochrane establishes that the fact that many non-human animals are sentient imposes a duty on humans as moral agents to establish and maintain a political order dedicated to non-human animals' interests. In what Cochrane (2018) labels as “sentientist politics,” a “sentientist cosmopolitan democracy” should be deployed to guarantee that all non-human animals' interests are included in deliberations over what is in the public good for communities. In this way, society and politics will be organized in a more democratic way, addressing not only the needs and interests of humans, but the needs and interests of all sentient beings, which, returning to our argument here, in turn will have a positive impact on the environment.

Feminist interspecies ethics have been developed mostly by non-speciesist ecofeminists (e.g., Donovan, 2011; Willett, 2014) and refer to the need for a contraposition of classical liberal male ethics with an ethics based on social roles and interdependencies amongst subjects and communities of species. In this way, the emphasis on rationalistic analysis of autonomous subjects and abstract principles (e.g., justice and interests) emphasized by the former is replaced with the latter's courage to address social interdependencies with care, i.e., with compassion, empathy and love. To be fair, compassion is what Adorno and Horkheimer, following Schopenhauer, also called for to address our relationship with other animals and to dismiss the idea of reason as an ultimate end of humanity. Because moral anthropocentrism is a trait intensely intertwined with the patriarchal mind dominating society, as the non-speciesist ecofeminists explain, and because journalism has traditionally been both an academic and professional field dominated by the male mind, the incorporation of a feminist interspecies gaze may help introduce the discussion of the wrongs and faults of moral anthropocentrism in media ethics in general, and in journalistic deontological codes in particular.

Specifically, introducing a compassionate gaze in the codes means, in short, expanding the circle of compassion to include other species, which in turn means widening morality. This is because compassion is not an irrational emotion, but rather a prosocial behavior (Kemeny et al., 2012), a response to the suffering of others, and a willingness to alleviate it (Curtin, 2014). As a prosocial mind-set and a proactive behavior against suffering, the current public's increasing compassion toward other animals should be seen as progress toward a more ethical society. Therefore, it is a matter of evolution in human ethics and consciousness to expand our circle of compassion beyond humans.

Both stances, interspecies justice and feminist interspecies ethics, could easily be incorporated into media ethics and reflected in deontological codes by including consideration of the consequences of human action or inaction on individuals of other species. This might help, in turn, unveil taboos such as the animal-based food taboo, which might be more easily dismantled by compelling humans to contrapose ethics with mere and arbitrary food choices. Good examples of such a stance in news reporting already exist, as in the case of Sentient Media (https://sentientmedia.org). This is a non-profit media organization precisely focused on the links between agriculture, animal oppression and the environment from an interspecies stance—in their words, “working to create transparency around industrial agriculture and the impact it has on humans, the environment, and animals.”

The Sentient Media case shows, in alignment with what Christians and Traber (1997) admonition, that the interspecies gaze needed for the moral progress of media ethics cannot be produced by the deontological codes alone; it requires the creation of what these authors call the “moral person.” By “moral person,” they refer to the fact that only “people who are truthful, forthright, gentle and compassionate are able to perform their duties—also as communicators—without analytical recourse to ethical codes.” That is, codes are useful and necessary, but professional ethics cannot be grounded merely on them but on the development of those moral traits that produce “moral people” able to decode codes ethically or to make ethical decisions without them, when codes are not useful or absent. “The proper approach,” according to Christian and Traber, “must be an ethical foundation that generates basic questions from a global perspective and places them in the concrete social and cultural contexts where communication processes take place” (Christians and Traber, 1997, p. 155).

Therefore, to be able to morally expand and interpret the deontological codes of journalism with an interspecies justice and feminist interspecies ethics, these approaches should also be introduced in media ethics in general, within academic and professional organizations' training of communication practitioners, and in discussions about how to update codes. Accordingly, deontological codes should be read and expanded so that there is an acknowledgment of the ubiquitous moral anthropocentric bias in society: the positioning of humans at the very center of meaning, value, knowledge, and action, and the lack of attention to what this means for the individuals of other species. Until this happens, the current bias will continue to prevent media ethics and journalistic codes from addressing a most remarkable aspect that also shapes the quality or condition of being human: our relationship with the rest of sentient beings on the planet. Furthermore, this bias prevents codes to properly address the totality of human interaction, neglecting a major component of domination and oppression.

Of course, this is a vast task that cannot be undertaken easily. However, efforts to an introduction of the ecofeminist and interspecies gaze may found fertile soil amongst the younger generations of communication practitioners, because of their increasing awareness and concern toward other animals and the environment. At the same time, the current codes, as they presently stand, already allow for significant protection of behaviors and ideals aligned with ethical and more sustainable modes of consumption. As Nordenstreng and Topuz (1989) found, a number of codes include securing the respect for a variety of cultures, philosophical and ideological convictions—what Article 9 of the IFJ's code mentions to avoid facilitating the spread of discrimination on grounds of political and other opinions.

This is aligned with the protection guaranteed to ideological minorities by the constitutions of all democratic countries (in the form of statements on the freedom of conscience, ideology or expression), by Article 10 of the European Union's Charter of Fundamental Rights, or by the Declaration on the Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious and Linguistic Minorities, approved by the United Nations in 1992 (Article 1). In this regard, in alignment with the topic of this paper, the news media should feel encouraged to respect, promote, and protect ideologies that peacefully promote lifestyles that represent a reduction in humans' global greenhouse gas emissions. This fully applies, for instance, to veganism, which is of interest here because of its relatively lower impact on the environment and a contrasted lower level of global warming emissions compared to omnivorous lifestyles, as mentioned in the introduction.

Veganism, according to the coiners of the term (see www.vegansociety.com), is a political stance that rejects the commodity status of animals and abstain, strictly for animal ethical reasons, from the use or consumption of products or services that involve animal exploitation. However, the vegan diet is also adopted often for health reasons or for environmental activism. In all cases it can be regarded as an ethical behavior implemented by a collective of people that fulfill the criteria of an ideological minority. Hence, journalists could start expanding the interpretation of codes by considering that vegans, particularly animal and environmental ethical vegans, form an ideological minority that deserve a fair treatment merely for the sake of moral justice. As such, they are protected by the principles of many deontological codes supporting respect and the lack of discrimination against other opinions. Until codes are not updated, this protection already allows the introduction of the respect for other animals in media ethics and deontological codes that this paper has argued is needed to unveil and neutralize the moral anthropocentrism at the core of our unsustainable environmental behavior.

This paper has thus examined media ethics through an usually neglected aspect of climate change denial: the ideological denial linked to environmentally harmful food habits, which it has been argued here has become a sort of taboo (our reluctance to not only abandon but to discuss the animal-based diet). In order to dismantle the taboo, I have suggested that media ethics and deontological codes address the moral anthropocentrism that lie at their foundations; more specifically, this anthropocentrism adopts the form of speciesism, the refusal to allocate moral consideration to other animals only because of their membership in non-human species. This paper has shown how current codes are blind to this bias and have suggested alternatives: the stances of interspecies justice and feminist interspecies ethics, as well as the implementation of the protection of ideologies like veganism already allowed by current codes. All these suggestions actually reflect ideals born also in the age of the Enlightenment and the progress made by normative moral ethics in general.

Climate change denial is also—if not mostly—about the denial of the moral anthropocentrism that has justified and triggered the unethical and unsustainable human practices that are today warming our planet to unprecedented levels. The claim made here, it must be stressed, is not a mere strategical claim, but rather an ethical one. As Karen Davis observes at the end of a very sensitive reflection on the identity of other animals, “we have become accustomed, through the environmental movement, to think of species extinction as the worst fate that can befall a sentient organism,” but for the animals confined and exploited for their flesh and fluids, their doom is just the opposite, never to become extinct (Davis, 2011, p. 64). In other words, while the usual public environmental concern focuses on biodiversity and extinction in nature because of anthropogenic climate change, there is a paradoxical parallel reality for billions of sentient individuals living in the same farms that bring about extinction in nature: the fact that their destiny is precisely to endure, individual after individual, life after life, the most excruciating misery.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The author was deeply grateful to the reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions.

Footnotes

1. ^We have actually created “reproductive rights.” These are legal rights and freedoms defined by the World Health Organization as follows: “Reproductive rights rest on the recognition of the basic right of all couples and individuals to decide freely and responsibly the number, spacing and timing of their children and to have the information and means to do so, and the right to attain the highest standard of sexual and reproductive health” (WHO, 2020).

2. ^See for instance the EU barometers on “Attitudes of Europeans towards Animal Welfare.” The latest: Special Eurobarometer 442 (European Union, 2016).

References

Almiron, N. (2020). “Rethinking the ethical challenge in climate change lobbying: a discussion of ideological denial,” in Climate Change Denial and Public Relations. Strategic Communication and Interest Groups in Climate Inaction, eds N. Almiron, and J. Xifra (London: Routledge), 9–25. doi: 10.4324/9781351121798-2

Almiron, N., Cole, M., and Freeman, C. P. (Eds.). (2016). Critical Animal and Media Studies. New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315731674

Almiron, N., and Zoppeddu, M. (2015). Eating meat and climate change: the media blind spot—a study of Spanish and Italian press coverage. Environ. Commun. J. 9, 307–325. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2014.953968

Bailey, R., Froggatt, A., and Wellesley, L. (2014). Livestock–Climate Change's Forgotten Sector Global Public Opinion on Meat and Dairy Consumption. London: Chatman House.

Bogg, C. (2011). “Corporate power, ecological crisis and animal rights,” in Critical Theory and Animal Liberation, eds J. Sanbonmatsu (New York, NY: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers), 71–98.

Bradbury, K. E., Murphy, N., and Key, T. J. (2019). Diet and colorectal cancer in UK Biobank: a prospective study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 49, 246–258. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyz064

Bristow, E., and Fitzgerald, A. J. (2011). Global climate change and the industrial animal agriculture link: the construction of risk. Anim. Soc. 19, 205–224. doi: 10.1163/156853011X578893

Bruun, L. (1979). Professional Codes in Journalism. Vienna: International Organization of Journalists.

Callicott, J. B. (2014). Thinking Like a Planet: The Land Ethic and the Earth Ethic. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199324880.001.0001

Centre for Biological Diversity (2018). The Climate Cost of Food at COP24. Available online at: https://www.biologicaldiversity.org/programs/population_and_sustainability/sustainability/pdfs/COP24-menu-analysis-fact-sheet.pdf (accessed October 22, 2020).

Chang, Q., Wang, W., Regev-Yochay, G., Lipsitch, M., and Hanage, W. P. (2015). Antibiotics in agriculture and the risk to human health: how worried should we be? Evol. Appl. 8, 240–247. doi: 10.1111/eva.12185

Christians, C. G. (2019). Media Ethics and Global Justice in the Digital Age. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/9781316585382

Christians, C. G., Glasser, T. L., McQuail, D., Nordenstreng, K., and White, R. A. (2009). Normative Theories of the Media. Journalism in Democratic Societies. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Cochrane, A. (2018). Sentientist politics. A Theory of Global Inter-Species Justice. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780198789802.001.0001

Cohen, S. (2001). States of denial: Knowing about atrocities and suffering. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Cole, M. (2015). “Getting (green) beef: anti-vegan rhetoric and the legitimizing of eco-friendly oppression,” in Critical Animal and Media Studies. Communication for Nonhuman Animal Advocacy, eds. N. Almiron, M. Cole, and C. P. Freeman (New York, NY: Routledge), 107–123.

Cole, M., and Morgan, K. (2011). Vegaphobia: derogatory discourses of veganism and the reproduction of speciesism in UK national newspapers. Br. J. Sociol. 62, 134–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-4446.2010.01348.x

Curtin, D. (2014). “Compassion and being human,” in Ecofeminism: Feminist Intersections With Other Animals and the Earth, eds C. J. Adams, and L. Gruen (New York, NY: Bloomsbury), 39–58.

Davis, K. (2011). “Procrustean solutions to animal identity and welfare problems,” in Critical Theory and Animal Liberation, eds J. Sanbonmatsu (New York, NY: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers), 35–54.

Díaz-Campo, J., and Segado-Boj, F. (2015). Journalism ethics in a digital environment: how journalistic codes of ethics have been adapted to the internet and ICTs in countries around the world. Telematics Inform. 32, 735–744. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2015.03.004

Donovan, J. (2011). “Sympathy and interspecies care: toward a unified theory of eco- and animal liberation,” in Critical Theory and Animal Liberation, eds J. Sanbonmatsu (New York, NY: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers), 277–294.

Dunlap, R. E., and McCright, A. M. (2015). “Challenging climate change: the denial countermovement,” In Climate Change and Society: Sociological Perspectives, eds R. E. Dunlap, and R. Brulle (New York, NY: Oxford University Press), 300–332. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199356102.003.0010

European Union (2016). Attitudes of Europeans Towards Animal Welfare. Special Eurobarometer 442. Brussels: European Union.

Faria, C., and Paez, E. (2014). Anthropocentrism and speciesism: conceptual and normative issues. Rev. Biotica Derecho 32, 82–90. doi: 10.4321/S1886-58872014000300009

Friedlander, J., Riedy, C., and Bonfiglioli, C. (2014). A meaty discourse: what makes meat news. Food Stud. 3, 27–43. doi: 10.18848/2160-1933/CGP/v03i03/40579

Gerhard, C. (2011). “Thinking with: Animals in Schopenhauer, Horckheimer, and Adorno,” in Critical Theory and Animal Liberation, ed. J. Sanbonmatsu (New York, NY: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers), 137–146.

Gruen, L. (2011). Ethics and Animals. An Introduction. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511976162

Hafez, K. (2002). Journalism ethics revised: a comparison of ethics codes in Europe, North Africa, the Middle East, and Muslim Asia. Polit. Commun. 19, 225–250. doi: 10.1080/10584600252907461

Henders, S., Persson, U. M., and Kastner, T. (2015). Trading forests: land-use change and carbon emissions embodied in production and exports of forest-risk commodities. Environ. Res. Lett. 10:12. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/10/12/125012

Himelboim, I., and Limor, Y. (2010). Media institutions, news organizations, and the journalistic social role worldwide: a cross-national and cross- organizational study of codes of ethics. Mass Commun. Soc. 14, 71–92. doi: 10.1080/15205430903359719

Horckheimer, M., and Adorno, T. H. (2002). Dialectic of Enlightenment. Philosophical Fragments. Standford, CA: Standford University Press. doi: 10.1515/9780804788090

IPCC (2019). IPCC Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse gas fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems. IPCC. Available online at: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/srccl/ (accessed October 22, 2020).

Jacques, P. J. (2012). A General Theory of Climate Denial. Glob. Environ. Politics 12, 9–17. doi: 10.1162/GLEP_a_00105

Jones, J. C. (1980). Mass Media Codes of Ethics and Councils: A Comparative International Study on Professional Standards. Paris: UNESCO. Available online at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000042302?posInSet=1andqueryId=56062f16-379c-46cc-8f37-e43eb4cb9b5c (accessed October 22, 2020).

Juusela, P. (1981). Journalistic Codes of Ethics in the CSCE Countries. Tampere: University of Tampere.

Kemeny, M., Foltz, C., Cavanagh, J. F., Cullen, M., Giese-Davis, J., Jennings, P., et al. (2012). Contemplative/emotion training reduces negative emotional behavior and promotes prosocial responses. Emotion 12, 338–350. doi: 10.1037/a0026118

Kiesel, L. (2009). “A comparative rhetorical analysis of US and UK newspaper coverage of the correlation between livestock production and climate change,” in Environmental Communication as a Nexus, eds E. Seitz, T. Wagner, and L. Lindenfeld (Maine, ME: University of Portland Maine), 246–255.

Kymlicka, W. (2018). Human rights without human supremacism. Can. J. Philos. 48, 763–792. doi: 10.1080/00455091.2017.1386481

Laitila, T. (1995). Journalists codes of ethics in Europe. Eur. J. Commun. 10, 527–544. doi: 10.1177/0267323195010004007

Lynch, J., and Pierrehumbert, R. (2019). Climate impacts of cultured meat and beef cattle. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 3:5. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2019.00005

Masterman-Smit, H., Ragusa, A., and Crampton, A. (2014). “Reproducing speciesism. A content analysis of Australian media representations of veganism,” in 2014 Proceedings of the Australian Sociological Association (TASA) Conference. Challenging Identities, Institutions and Communities, eds B. West (Adelaide, SA: University of South Australia), 1–13.

Mattick, C. S., Landis, A. E., Allenby, B. R., and Genovese, N. J. (2015). Anticipatory life cycle analysis of in vitro biomass cultivation for cultured meat production in the United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 11941–11949. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b01614

McCright, A. M. (2016). Anti-reflexivity and climate change skepticism in the US general public. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 22, 77–107. doi: 10.22459/HER.22.02.2016.04

Molloy, C. (2011). Popular Media and Animals. London: Palgrave MacMillan. doi: 10.1057/9780230306240

Moreno-Cabezudo, J. A. (2019). ‘Hablemos de la Carne, pero sin Demonizarla’. Representacin en la Prensa Espaola del Impacto Climtico de la Explotacin de Animales en Granjas [Let's Talk About Mea, but Without Demonizing It. Representation in the Spanish press of the climate impact of the exploitation of animals in farms] (Master Thesis). Barcelona: Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Department of Communication.

Neff, R. A., Chan, I. L., and Smith, K. C. (2008). Yesterday's dinner, today's weather, tomorrow's news? US newspaper coverage of food system contributions to climate change. Pub. Health Nutr. 12, 1006–1014. doi: 10.1017/S1368980008003480

Nibert, D. (2013). Animal Oppression and Human Violence. Domesecration, Capitalism, and Global Conflict. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Nocella, A. J., II, Sorenson, J., Socha, K., and Matsuoka, A. (eds.). (2014). Defining Critical A Studies. New York, NY: Peter Lang. doi: 10.3726/978-1-4539-1230-0

Nordenstreng, K. (2008). “Cultivating journalist for peace,” in Communicating Peace: Entertaining Angels Unawares, ed P. Lee (Penang: Southbound), 63–80.

Nordenstreng, K., and Topuz, H. (eds.). (1989). Journalist: Status, Rights and Responsibilities. Prague: International Order of Journalists.

Olausson, U. (2018). “Stop blaming the cows!”: how livestock production is legitimized in everyday discourse on facebook. Environ. Commun. 12, 28–43. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2017.1406385

OMS (2019). IARC Monographs on the Identification of Carcinogenic Hazards to Humans. (Agents Classified by the IARC Monographs, Volumes 1–123). Available online at: https://monographs.iarc.fr/agents-classified-by-the-iarc/ (accessed October 22, 2020).

Peterson, D. J. (1993/2019). Troubled Lands: The Legacy of Soviet Environmental Destruction. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780429269615

Philpott, T. (2013, September 9). One weird trick to fix farms forever. Mother Jones. Available online at: https://www.motherjones.com/environment/2013/09/cover-crops-no-till-david-brandt-farms/ (accessed October 22, 2020).

Picard, R., G. (1985). The press and the decline of democracy: The Democratic Socialist response in public policy. Westport, CT: Greenwood.

Pickard, V. (2015). America's Battle for Media Democracy. The Triumph of Corporate Libertarianism and the Future of Media Reform. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139814799

Sanbonmatsu, J., (ed.). (2011). Critical theory and animal liberation. New York: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers.

Scarborough, P., Appleby, P. N., Mizdrak, A., Briggs, A. D., Travis, R. C., Bradbury, K. E., et al. (2014). Dietary greenhouse gas emissions of meat-eaters, fish-eaters, vegetarians and vegans in the UK. Clim. Change 125, 179–192. doi: 10.1007/s10584-014-1169-1

Shapiro, J. (2001). Mao's War Against Nature: Politics and the Environment in Revolutionary China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511512063

Siebert, F. S., Peterson, T., and Schramm, W. (1956). Four Theories of the Press: The Authoritarian, Libertarian, Social Responsibility and Soviet Communist Concepts of What the Press Should be and do. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Singer, P. (1975). Animal Liberation: A New Ethics for our Treatment of Animals. New York, NY: Random House.

Singer, P. (2011). Practical Ethics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511975950

Saron, D. (2011). “Road kill. Commodity fetishism and structural violence,” in Critical Theory and Animal Liberation, ed. J. Sanbonmatsu (New York, NY: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers), 55–70.

Springmann, M., Godfray, H. C. J., Rayner, M., and Scarborough, P. (2016). Analysis and valuation of the health and climate change cobenefits of dietary change. PNAS 113, 4146–4415. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1523119113

Stanescu, V. (2020). “‘Cowgate’: meat eating and climate change denial,” in Climate Change Denial and Public Relations. Strategic Communication and Interest Groups in Climate Inaction, eds N. Almiron, and J. Xifra (London: Routledge), 178–194. doi: 10.4324/9781351121798-11

Steinfeld, H. (2006). Livestock's Long Shadow: Environmental Issues and Options. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

Thorstad, E. B., Todd, C. D., Uglem, I., Bjorn, P. A., Gargan, P., Vollset, K. W., et al. (2015). Effects of salmon lice Lepeophtheirus salmonis on wild sea trout Salmo trutta–a literature review. Aquaculture Environ. Interact. 7, 91–113. doi: 10.3354/aei00142

Ulmane, P. (2020). Media Coverage on Veganism in the Context of Climate Crisis in Spanish and French Media. Final master Project presented at the Master in Discourse Studies: Communication, Society and Learning. Barcelona: Universitat Pompeu Fabra.

UN News (2018, November 8). Every Bite of Burger Boosts Harmful Greenhouse Gases: UN Environment Agency. Geneva: United Nations. Available online at: https://news.un.org/en/story/2018/11/1025271 (accessed October 22, 2020).

UNEP (2018, November 8). What's in Your Burger? More Than You Think. Available online at: https://www.unenvironment.org/news-and-stories/story/whats-your-burger-more-you-think (accessed October 22, 2020).

Veganbits (2020). How Many Vegans in The World? In the USA? (2020). Available online at: https://veganbits.com/vegan-demographics/ (accessed October 22, 2020).

Wang, Z., Bergeron, N., Levison, B. S., Li, X. S., Chiu, S., Jia, X., et al. (2018). Impact of chronic dietary red meat, white meat, or non-meat protein on trimethylamine N-oxide metabolism and renal excretion in healthy men and women. Eur. Heart J. 40, 583–594. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy799

Warman, P. R. (1980). The Basics of Green Manuring. Ecological Agriculture Projects. Available online at: https://eap.mcgill.ca/publications/EAP51.htm (accessed October 22, 2020).

Weitzenfeld, A., and Joy, M. (2014). “An overview of anthropocentrism, humanism, and speciesism,” in Defining Critical Animal Studies, eds A. J. Nocella II, J. Sorenson, K. Socha, and A. Matsuoka (New York, NY: Peter Lang), 3–27.

WHO (2020). Gender and reproductive rights. World Health Organization website. Available online at: https://web.archive.org/web/20090726150133/http://www.who.int//reproductive-health/gender/index.html (accessed October 22, 2020).

Willett, C. (2014). Interspecies Ethics. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. doi: 10.7312/will16776

Keywords: climate change denial, ethics, moral anthropocentrism, speciesism, deontological codes, journalism

Citation: Almiron N (2020) The “Animal-Based Food Taboo.” Climate Change Denial and Deontological Codes in Journalism. Front. Commun. 5:512956. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2020.512956

Received: 18 November 2019; Accepted: 05 October 2020;

Published: 11 November 2020.

Edited by:

Toby Miller, University of California, Riverside, United StatesReviewed by:

Jennifer Peeples, Utah State University, United StatesKajsa-Stina Benulic, Linköping University, Sweden

Copyright © 2020 Almiron. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Núria Almiron, bnVyaWEuYWxtaXJvbkB1cGYuZWR1

Núria Almiron

Núria Almiron