- Negotiation and Conflict Resolution, School of Professional Studies, Columbia University, New York, NY, United States

This article focuses on the necessity to build relationships with people across cultures, while doing participatory action research (PAR). There are many assumptions attached to the term “participation” and it is not only worth exploring how these assumptions are formed and how they manifest during participatory action research projects, but is necessary to build trusting relationships. Taking a communication perspective through the lens of Coordinated Management of Meaning (CMM), provides the framework to see which voices are heard and privileged, and how researchers with more formal experience blend in partnership with those possessing local knowledge and practices. These many influences shape the dynamics of the relationships, create the episodes of which these experiences are a part, and impact the efficacy of the work. These layers of complexity need to be considered and addressed. CMM Models and concepts aid us in becoming aware of the moral or “logical” forces that are attached to the contexts we prioritize and was applicable to the case study we did in Medellín, Colombia, which was key to developing self-awareness. These contextual influences are culturally bound and in order to have equitable participatory processes across cultures, becoming more aware of the origin of these tendencies is critical. In addition, the more self-aware all the researchers become, the more it leads to developing better partnerships in these PAR processes.

Introduction

The world is becoming a smaller space. You are traveling more and even in your hometowns, you are interacting with people from different cultural backgrounds and orientations. The homogeneity you knew in your schools, communities and workplaces has given way to an increase in diversity. With this increase in diversity comes a proliferation of perspectives adding to the complexity of everyday life, so that you can no longer comfortably make assumptions that you are all on the same page with the same interests and points of view. Doing so will lead to making many erroneous assumptions that will leave you with silence and missing information or more “in your face” conflict.

There are some who seek to engage with people different from their own background, understanding and welcoming the different perspectives, values, and practices. The balance of predictability and the unexpected can produce the aesthetic and increase engagement [Dewey in Crippen and Schulkin (2020)] and this sustains the will to persevere even in the face of adversity. However, good intentions alone and heightened desire to engage may not prevent these differences from getting in the way of building trust and developing respectful relationships, critical in engaging in participatory action research (PAR) (Chevalier and Buckles, 2019; 153). Social customs can enhance or interfere when developing relationships with others. Some of these customs influence perceptions and practices related to health and hygiene.

There are cultural measures that highlight similarities and differences according to the general tendencies of populations from particular cultures. One example of this is the continuum on individual or collective orientations (Triandis, 1995; 19). The United States for example, is measured as being more individualistic in goal setting and achievement than many Latin American countries, whereas Latin American countries are known for having a stronger collectivist and group orientation (Triandis, 1995; 91). There are implications here for how work gets done, how goals are achieved and the expectations as to whether they will be addressed individually or as a member of a group. People from more individualistically-oriented cultures will propel themselves forward on their own and expectations will be that other individuals will also come forward on their own. However, from more collectively-oriented cultures, there will be forms of group monitoring, permission-seeking and consensus before moving forward because it is a group effort and not up to any individual alone.

There are other cultural markers that differentiate one group from another, such as differences across gender and socioeconomic groups. The strength of these cultural attributes determine how malleable the norms and practices are when it comes to interfacing with people from different cultural orientations. This is also known as how tight or loose a culture is and how wedded they are to their practices and belief systems (Gelfand, 2018; 106). A tight mindset would reflect more adherence to a specific set of rules to follow, while a loose mindset would allow for more flexibility in interpreting these rules.

If you take a step back you can see that each group you belong to has its own set of characteristic norms, beliefs and practices. In order to be considered a member of that group you need to follow the prescribed protocol that acculturates you into that community. Some groups you are born into and others you choose to belong. It is up to the elders in the group or those assigned to impart knowledge and customs to educate you about what it means to be a member of that group. Some of these customs are set very tight and are more prescribed than others that are loose and open to a broader range of interpretation.

To illustrate this point further, we can think about criteria that are established as rites of passage to be allowed to enter into a group of your choosing. In a professional case, if you want to be a professor in an academic institution, you need to demonstrate competency in research and knowledge and one way of doing that is by obtaining a Ph.D. This is a fairly tight cultural norm although on occasion there are exceptions to the rule when there are acceptable tradeoffs. For example, in some situations professors may not have a Ph.D. if there are other qualifications they bring that are attractive to the university. In this situation there is some wiggle room on the norm.

In social settings, there are certain protocol in place about hierarchy in a home and who gets served first. In traditional Japanese homes, the head of household, which is usually a man, gets to read the newspaper first, take his bath or ofuro first, and gets his meals served first. The wife in these situations was considered to be doing the duties of her role by making this happen. Over the years, these cultural traditions have loosened as more women are in the workforce, the younger generation has access to more external influence and is not willing to put up with these practices, and the pace of life is faster and seeking more conveniences. The originally tight cultural norms have been loosened by the changing demands of modern life.

Cultural Norms in PAR

Adhering to cultural norms really hits home when doing PAR and interventions in cultures that differ from your own. It is a challenge to figure out what to do to build relationships and trust, with the customs and expectations being so different and in some cases really test your willingness to participate. This raises questions of where you are willing to compromise and where a line is present that you just cannot cross. It is where deeply rooted beliefs and values are found.

Any outsider to a particular group does not immediately know the norms and customs of this different culture and observable practices may not be enough to further understanding. Borrowing from ethnography, there is a need for thicker descriptions to take place so that a richer understanding can be gleaned, which will in turn influence the meaning making process. The act of this engagement can also serve the dual purpose of building relationship and developing trust because there is sincere curiosity and what Deetz (2014) refers to as genuine conversation because in partnership there is “growing and changing together in response to situations and events” (226). The external researcher is open to learning and the members of the group are open to sharing and informing. If the researcher then integrates this understanding into further actions and the group integrates their understanding of the researcher and her intentions, this reflexive cycle of action and meaning making continue to inform one another (Wasserman and Fisher-Yoshida, 2017; 13).

One example that is related to health and hygiene is that there are many cultural and religious practices that differ in terms of how food is prepared, meals are eaten, personal hygiene is attended to, and other ways in which cleanliness standards may be tested (WHO, 2009). There is also the consideration of socio-economic status and access to clean water, soap and the everyday habits developed of keeping clean and ranking how important that is in terms of other demands of living and survival.

An illustration of this is when a participatory researcher from the United States is eating meals or having a drink with a group of youth leaders in Colombia. Each person orders his or her own meal, yet there is a lot of passing of plates and sometimes portions are shared with the same fork. When in a bar listening to music, shots of guaro (a clear liquor distilled from sugar cane) are poured and the plastic shot glasses are interchanged. Do you accept the food and taste some? Do you accept the shot of guaro from a communally shared shot glass? In most cases, the researcher is being carefully watched to see how she participates and so it is not easy to fake it. You are in or you are not.

In these times of pandemic virus, the challenge of these customs is highlighted even more. Those “moments of truth” when you need to decide about how to maintain your sense of health and safety and at the same time, continue to build trust and relationship and not offend others, is prime. This is going to happen within cultural groups, as well, as you either take initiative or wait and see whether you stay diligent to health warnings or slip back into traditional cultural customs.

There are the obvious actions that are able to be witnessed and then there are the implied values and practices that are layered and not visible. It is a matter of knowing what the appropriate protocol is because knowing the signals of whether you are in sync with what is expected or you transgressed a sacred norm may be convoluted and not understood. These cultural overlays to what may appear to be straightforward communication is what makes these situations that much more complex. You may enter into the environment with certain intentions, yet how those intentions are enacted can make the difference as to whether you are understood as you had hoped, you missed the mark and no harm was done, or you not only missed the mark, but caused a great deal of insult and injury. There are tools to support the unpacking of these meaning making moments, such as those used in the practical communication theory, Coordinated Management of Meaning (CMM), which will be explored in the next section.

PAR Material and Methods

The researcher will describe two scenarios she faced when doing PAR in Colombia in which critical moments of decision-making have been fateful to the quality of the relationship-building and success of the project. Participatory action research is built on the three pillars of participation, action and research, that involves local populations actively participating in research and knowledge-making processes (Chevalier and Buckles, 2019; 24–25). In participation as per PAR, the researchers from the university and the local researchers in the community both partner in deciding the action steps to be taken and how the research will be conducted. None of the parties partakes passively, rather all have a voice in any and all aspects of the engagement (27). Walking the talk of participation involves taking a step back from the project and really examining your own deeply held beliefs of what it means to participate, the rules that are present and adhered to, the values of doing research, and more.

Communication Perspective

The CMM, a practical theory that takes a communication perspective, will be used to analyze these scenarios and surface implicit cultural norms and values and how meaning is made in relationship through communication (Fisher-Yoshida, 2014; 877). Theories from the field of intercultural communication, specifically, individualism and collectivism (Triandis, 1995; 50–51) and tightness and looseness (Triandis, 1995; 52–60; Gelfand, 2018; 35–52) will be used as lenses to interpret the different cultural practices, norms and expectations (Bennett, 2015; xxiii–xxvii). Together this set of theories will elicit and make sense of interactions that happen between people across cultural norms and how that affects their relationships and the social worlds they are making, which in turn impacts the quality of the output and impact of the participatory research.

When we engage in this communication, or speech act, it can be spoken or unspoken and is governed by what took place before and what will take place in response to these actions we are performing now. CMM helps us define the triplet of past action, action, future action, is understood in the context it is in, which can be the particular episode or relationship. The episode can be the creation of the PAR project, for example, and the relationship is between the researcher and the local participants or among the local participants, for example (Pearce, 2007; 205). How we make meaning in this situation changes by which context has a stronger influence: the episode of creating the PAR project or the quality of the relationship, and the relevance of these contexts can shift depending on what is happening and what is being elevated as having more influence. As mentioned earlier, every action leads toward meaning making and every meaning made about the episode or about the relationship, then influences subsequent actions in a reflexive process.

The actions that are decided can originate from the local community or the external researcher coming to the community. They can be activities that the community has been engaging in over time or they can be activities recently introduced specifically for the project. Regardless of the action’s origins, all parties need to agree to the actions being taken and they can be modified as appropriate to the specific situation. The research approach is a combination of bringing in new lenses of how to “see” the community from external sources, which will elevate aspects of interactions and occurrences that may not have been noticed prior to the engagement. CMM offers ways in which to make explicit points of view that may have been implicit before and this shift in perspective can generate fear of the unknown or if the right balance is achieved, an aesthetic experience.

This ability to see patterns of thinking and acting that may previously not been disclosed, with the use of CMM models, offers new insights into how decisions are made. Deciding what qualifies as data needs to be explored and here is where there is opportunity for all involved members to surface their assumptions as to what qualifies as data, what purpose it serves, how it will be interpreted and understood, and how it will be applied to subsequent interventions and potential transformations. These new sources of data may affect the speed at which decisions are made. Previously, when information was assumed to be familiar, decisions could be made quickly without a lot of reflection, similar to what Kahneman describes as system one thinking (Kahneman, 2011; 20–24). New information from new data sources, forces decisions to be made at a slower and more reflective pace, characteristic of system two thinking. CMM surfacing of patterns in communication leads toward more system two thinking.

Belief Systems

There are many ways the researcher’s belief system is tested and it is a great opportunity for developing more self-awareness as a result. The researcher gets to determine what is critically important and what is not, as there are many moments in which challenges are presented in the form of decisions to be made. These are critical moments and points of choice as to whether to act in accordance with the way research has always been done or slow down the process to question the origin of these practices and how they hold up in this new cultural context. It will influence how participation is actually achieved.

It is important to highlight that the researcher is entering into a system that has existed over time with many previous parties in conversation, many actions taken, and many meanings made. It is unrealistic to think that there will be a completely fresh start because all involved have their past experiences that provide lenses for how they understand the present. In following the triplet form at a more macro level, you can see there were many influences that created the community to be the way it is today, and all of those experiences shape how the situation and context of this PAR intervention are created, that will then shape the future direction of the community.

Case/Scenario: Getting to Know the People and the Landscape

The researcher is involved in developing educational programs for youth leadership development, social and conflict transformation in communities, and transforming narratives as a way to both foster and measure these changes. In order to develop approaches that are relevant and effective outside the academy, it is important to do fieldwork to more fully understand these real-life situations to encourage more alignment between what is being taught and what is applicable in the field. The researcher has an orientation of partnership and recognizes there are different types of knowledge and that it takes these different forms of knowledge and experience to create a comprehensive program that gets at the heart of stimulating sustainable conflict transformation.

Creating these partnerships and engaging in mutual learning was the impetus behind the researcher’s interest in doing this fieldwork. Being invited into these communities by a colleague who had previously established relationships was the opening needed. This also allowed for a foundational layer of trust to be present from the start because the introduction assumed goodwill and was based on the understanding that my friend is your friend, too, or at least not your enemy. The researcher knew that reputation is everything and wanted to not only honor this favor from her colleague, but also establish her own reputation in the right light. Her colleague had been researching the conflict in Colombia and the assumption by the youth leaders was the researcher would be doing something along similar lines. She knew that she was entering into an existing relationship and set of conversations involving multiple parties.

The researcher believed that in order to get access to information that was critical to deeply understanding this environment, she would need to establish trusting relationships with these youth leaders. There is the presentation of self in everyday life that one puts on in the world, but that is not necessarily the truest form of self (Goffman, 1959; 2). We do this as a form of protection and it takes trust to let down our guard. According to CMM principles (Pearce, 2007; 101), we make our social worlds through our communication and in order to have the type of relationship that would allow for more honest communication there needed to be trust. Open and honest communication takes away any façade that may initially be there and makes the people in communication with each other potentially vulnerable. It is this vulnerability that demands trust in that people will open themselves up to others because they trust the others will not hurt them or take advantage of them in the process. The researcher believed this level of trust, openness, and vulnerable communication was critical to obtaining the information that would lead to more effective youth leadership development programs.

Trust is a complex concept in itself and how trust gets enacted and understood is also susceptible to cultural interpretations. If we think of these communities as systems of people interacting with each other, there is a certain balance that is derived and this keeps the status quo intact. The balance comes from the familiarity of knowing the social norms, what is to be expected of each other, and how to respond in those situations. Yet, life does not always stay the same, nor is it always predictable, so someone coming from the outside entering the complex system without an awareness of the members or the norms and practices, might create a disturbance that sends ripples throughout the system. However, the system is open and adaptive and will either embrace the intruder and make it part of the system, thus building trust, or reject the intruder damaging the relationship (Durie and Wyatt, 2013; 176). If done with respect and the right balance of new and different to slightly shake the taken for granted assumptions about how the world works, it could provide the appropriate level of engagement.

Entering the Medellín System

There are some researchers who want to “go native” when they are learning about and experiencing different cultural environments. Sometimes there is not really a choice because of the physical conditions and resource limitations of particular places. One example of this was when the researcher was first visiting Medellín, Colombia and getting to know the environment and the youth leaders she was meeting. The center of the city is developed and enjoys a high standard of living with all the amenities of comfort you could seek. However, the fringe territories that developed in response to the long-term civil war in the country and the high number of internally displaced persons and without urban planning, is another story.

These territories are very hilly and were built of makeshift lean-tos with no indoor plumbing or electricity. Over the years and their longer than expected residency, the residents have refurbished some of these haphazardly built lean-tos into brick structures even if they do not hold titles of ownership nor have building permits. Needless to say there is not an abundance of public facilities or any in some places, so as we went on these long 4 h hikes nature would call as it is known to do. This is a situation in which the researcher felt the disadvantage of being a woman. She had to deal with the discomfort of having to wait and then when a facility was found that she could use, she needed to just get in there and do her business in as clean and safe a way as possible.

None of this was ideal and yet there was a felt obligation to continue going on these hikes for several reasons. The researcher wanted to get to know the environment from the perspective of the people living there and to understand their everyday struggles. She also wanted to be respectful of the youth leaders who took great pride in planning and guiding her on these journeys. These were “critical moments” or moments of truth in their relationship-building. The youth leaders may have known there were points of discomfort for her and they wanted to see how she would handle them, what she was made of, or they were so used to experiencing these living conditions they may not have even realized there was inconvenience involved.

In taking a communication perspective, as is characteristic of CMM, to look at patterns within communication, there is an interplay between actions and meaning making. Pearce (1989) coins these as resources and practices in that resources are expressed in practices and these practices then (re)construct resources (25). Pearce goes on to say that, “From a communication perspective, both change and permanence in political and economic systems are achieved by the (re)construction of resources in practice, and both are equally interesting” (24–25). The practice of engaging in these long hikes to bear witness to the resources available to these youth leaders, in the physical terrain in which they operate, in the camaraderie they have with one another, and in the motivation and desire to make a better social world, are present and open to change and enhancement in coordination with the researcher. This invitation and responsibility was felt by the researcher.

The first 2 years of the researcher visiting Medellín involved at least one of these hikes each trip, which was several times a year. The patterns of struggle and the resilience of the people was constant. The stories of struggle and surviving violence were profound and the scars they bore were visceral. Yet there was still a determination to not give into it and to find ways to deal with it, overcome it, and make it better for the next generation. Inherent in all of this was a force of will and knowledge. In order for the researcher to learn from them in this very personal way, she needed to sacrifice her comfort for those spans of time that may have felt never-ending, but were really only a day here and there of unease.

Understanding Priorities

In the above scenario, the CMM (Pearce, 2007; 141–148) was used for interpreting these dynamics. The CMM hierarchy model shows the different levels of context and how these levels set priorities from which the actors act (Pearce, 2007; 141–142). The context that is placed at the top of the hierarchy is the most important at that time and has the largest amount of influence on all decisions and actions. The context directly beneath that is second, and so on for a few layers of context.

The contexts can shift around and change depending on what else is taking place that might influence their placement. Life is fluid and this assembling and ordering of contexts reflects this fluidity as well. Within each context there are characteristic behaviors that are culturally and morally appropriate and connected. These are called logical forces and promote people like us to perform these types of acts in situations like these (Pearce, 2007; 156).

It was soon evident that the local youth leaders were tacitly following an unwritten protocol of how to behave in certain situations, their local logical forces, and did not always find it necessary to inform the external researcher about these norms. First, they were most probably not aware of the need to inform because these habits were such a part of their everyday life they did not even notice them and assumed it was common knowledge. Second, is that it further highlighted the “foreignness” of the external researcher because she did not know what these norms were and tried to follow along by observing what was taking place. However, on the flip side, the external researcher could use her “ignorance” to ask certain questions to intentionally provoke the participants to reflect on the assumptions they have, their values, and moral codes of what should and should not be for the purpose of making them explicit. Then they can have conversations about the value of these norms, how they serve them, how they may enhance or get in the way of transformations they claim to desire.

Interrupting the System

This inquiry would add a disruption to the taken for granted flow of activities (or practices) that were based on the assumption that all involved parties would tacitly know how to proceed. The researcher was coming into an already established pattern that started before her and would continue after her, yet the degree of the interference and its value would determine the trajectory of the flow of activities or how their practices would be enacted, directly following the disruption. Viewing this as a triplet of events, with the researcher’s inquiry in the middle, elevates the meaning of the interruption. The researcher by her very being there is now a part of that system and as a member can decide how active or passive she wants to be. Asking questions of the meaning behind the practices is a conscious act of making an explicit disturbance into the system for the very purpose of both trying to gain a deeper understanding of what was taking place and at the same time, bringing to awareness these tacit practices in which the youth leaders had been engaging.

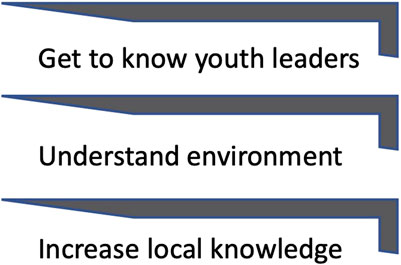

The researcher made the decision to continue to go on these hikes and put her personal discomfort as a lesser priority for these spans of time. Her first priority was to get to know the youth leaders she was meeting, to understand their environment to know the context better, and to continue to increase her local knowledge so she could think of ways to make connections with her own tacit knowledge base. The temporal conditions that framed these encounters was that they were the necessary beginning to build a foundation for a long-term relationship, a midpoint in the triplet of events. Each journey was viewed as a building block toward something deeper and richer and while the significance attached to each encounter was always high, it was less critical as individual meetings in themselves and more critical toward creating the pattern of the longer-term relationship. The researcher was new to the system and integrating into it on some level.

The logical forces at work in the ordering of the hierarchy in this sequence are practical and implicative (Pearce, 2007; 156) (Figure 1). The practical forces create situations in order for something to happen as a consequence. In the case of the researcher agreeing to go on these long hikes with youth leaders, she was making a decision that this would build better relationships. She understood that the only way to really get to the heart of the matter and what she wanted to affect, she needed to demonstrate respect and interest in order to build trust. These hikes to share intimate local knowledge was their way of extending an invitation into their world and it carried meaning on so many levels. The researcher also knew this would set the tone for subsequent encounters because news travels fast in these circles through conversations, WhatsApp, and Facebook. One picture from the hike posted on these social media platforms is very telling.

Adding Resources to Practice

A visual representation of what was taking place would be a new resource added into the mix of what had been everyday practices of the youth leaders. The photograph would express that there was a change in the system by the mere presence of the researcher and this would spark curiosity or mystery, one of three principles of CMM, into the minds of others seeking to engage. The mystery about what was taking place and wondering how it might affect others or how they may want to be affected by it, was now another resource that could play a role in affecting subsequent practices of engagement. This could lead to more coordination, a second principle of CMM, of practices and meaning making, between the researcher, youth leaders and community members.

The implicative force in this scenario is that the researcher wanted to convey intentionality to work in partnership to transform the context. The youth leaders were sharing their plight and the initiatives they had spearheaded to address the hardships the community was experiencing. They were also seeking support and resources to continue to be more effective in their outcomes and building their own knowledge base and so this act of shared experience hiking together was aimed to foster a mutually beneficial and trusting working relationship. It was an action loaded with meaning making for the youth leaders and the researcher about the social world they were co-constructing.

One of the goals in developing this partnership was to identify the ways in which the learning from the academy could be transferred to these youth leaders to enhance the work they were already initiating in their communities. In addition, in order to carry out the participatory research with these youth leaders, the ambition was to prepare them to be co-researchers. This meant that certain provisions needed to be made in terms of assessing their skills and knowledge and enhancing them so they could be fully present as researchers. This would be adding a new resources into the mix and shifting some of the practices in which the youth leaders would be more equipped to engage. In addition, it would have an impact on their identities and feelings of self-worth.

This may sound like a lot of calculations on the part of the researcher, and at the core of all of these decisions was that she wanted to be effective in what she was setting out to do. In order to create a dynamic of true participation she knew she needed to build relationships and this was a good way to do it. It is through the use of these analytical tools that you can see more specifically why dynamics work the way they do and therefore, be more intentional in your actions to foster the reactions you seek. It is a way of asserting more agency into the meaning making process.

Case/Scenario: Performance in Social Gatherings

Customs relating to food preparation have historic roots connected to health and utilizing what is locally available and attuned to the seasons. You have certain habits based in traditions long ago about how to prepare food so that there were limitations on bacteria meant to keep you healthy (Prakash, 2016; 1–4). This also influenced specific food combinations and the use of local herbs (Prakash, 2016; 4–5). Over the years some of these customs have been modified with modern advances, the spread of ideas through travel, changes in everyday lifestyle habits and limitations imposed out of necessity because of lack of access to resources.

There are also sanitary guidelines attached to hand washing as a way to limit the spread of germs and not sharing utensils and cups so as not to spread disease from person-to-person (WHO, 2009). However, there are certain times when social norms and acts of camaraderie supersede those messages of healthy practices. Someone might offer you some of their meal as a gesture of hospitality and bonding. How you respond in that moment is fateful because it sends the message of who you are in relation to the person making the offer.

Another example of this could be in the context of inviting someone to your home. The relationship is you being a host and when a guest comes to your home you offer them a beverage. Depending on the cultural context, you could ask their preference of beverage or you could just serve them a beverage so they are not in the potentially awkward situation of selecting something you may not have available. If you are on the receiving end of this beverage, you may accept at once or refuse several times because that is typical polite behavior according to your cultural norms. These are logical forces associated with specific contexts. Earlier, practical and implicative logical forces were exemplified and in this case, you look at what is expected from contextual logical forces. Each context has its own guidelines of what you “should” do in situations such as this. As a host you make an offer and as a guest you receive this offer.

Customs Through a Communication Lens

The gesture of “just offering and receiving a drink” is built on layers and layers of cultural practices that are loaded with implicit beliefs that influence meaning making. If the engaged parties are from different cultural backgrounds, the resources they have from which to make meaning of this practice may not be the same and thus the meaning construed may differ slightly or greatly. In order for the two parties to continue on their journey of relationship building, they will need to coordinate their efforts to create a shared understanding, so that they can also gain internal coherence, the third CMM principle. There is a dance between coordinating efforts with others and feeling coherent in the process.

In the case of the researcher, there was a moment when she had to make a decision about which context was more important in her own hierarchy; usual hygiene and personal choice or building relationships across cultures. These are not easy choices to make because they are governed by habits and habits are difficult to break. In addition to the physical discomforts that might be faced there are also the moral, emotional and psychological barriers to cross. Logical forces are deeply embedded in your core being as they are products of cultural values and norms that you have become accustomed to over time and are deeply ingrained.

What may have started out as living habits that have hygienic roots has morphed into a value-based judgment of what is right and wrong. It is easy to lose sight of the origins of your customs if you even ever had knowledge of the reasons for their beginnings and think of them instead as the way things have always been done and the only way they should be done.

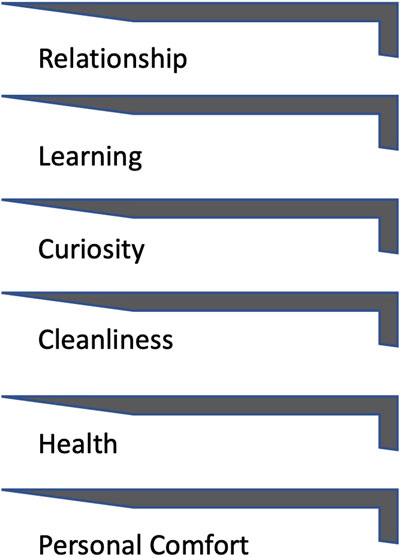

If the researcher stays with the context setting in this order:

She risks alienating the people with whom she is working on a participatory research project (Figure 2). This is her personal preference when she is home and on her own turf and all living conditions are arranged so this standard can be maintained. However, when stepping outside of this familiar zone of comfort there are decisions as to how malleable these cultural practices will be. If the researcher can attribute particular approaches to everyday life as part of the culture and accept that it is not necessarily good or bad, rather relative to the culture, it may be easier to abide by the local norms (Caduff, 2011; 467–470). “When in Rome…”

What Do the Youth Think?

For the youth leaders with whom the researcher was becoming familiar, she was an unknown entity and there may have been suspicions about her and her real intentions to come to their community, which were unknown to them and they did not trust. They may also have viewed this as an opportunity to expand on their resource base since the researcher was coming from abroad, an elite educational institution, and the assumptions attributed here are she is resource-rich and we want to benefit. Plus, in the past, there have been other visitors who seem to depend on the local youth leaders for information, yet the youth leaders and community do not actually end up benefitting from these visits.

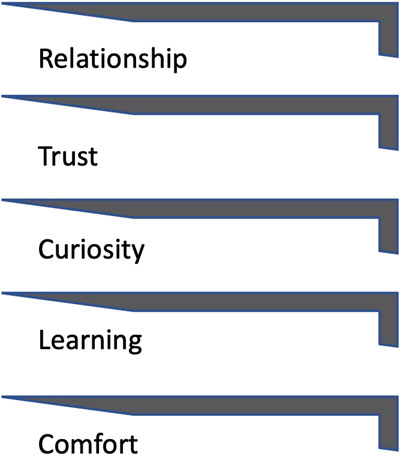

Their hierarchical ordering of contexts may look more like:

Health and cleanliness may not even be a consideration because they are in their usual environment and are accustomed to the way they are living and maybe have always lived (Figure 3). There is nothing different happening for them to make them consider health factors. Instead, what is important to them is this new person entering into their community and wondering whether this person can be trusted and if this will be another one-off visit as from others in the past or there will be short and long-term benefits to the community.

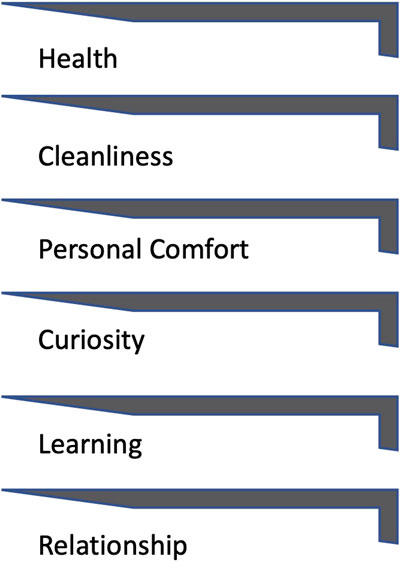

The researcher needs to realize there is a lot at stake here. The relationship and the relative success of the project is at risk and the next steps will influence how well the participation will be in this project. If she can gain the trust and confidence of the youth leaders then the project they are embarking on together will have a much higher rate of success. In order for that level of coordination to happen, the researcher will need to reorder her hierarchy of contexts to reflect these intentions and subsequent behavior. Instead, they should be:

More recently, with the spread and likelihood of further occurrences of global pandemics, decisions on how to interact take on new dimensions of ethical or moral responsibility (Caduff, 2011; 476–477) (Figure 4). This is also subject to being influenced by differing belief systems as to the validity of science, scientific findings, and recommendations of courses of action, especially if there is suspicion attached to these findings. This is also nurtured by belief systems that are grounded in the norms, values and practices that are culturally influenced. Some who believe in what science advocates and that you cannot argue with facts, follow a system of there being a universal moral code, while others believe that moral or ethical judgment is culturally bound.

Discussion

Stating that a process is participatory generates expectations that certain types of behavior will be engaged that actually foster participation. However, as witnessed earlier, how priorities are framed in the decision-making process is critical because the associated practices may differ. There needs to be shared understanding from various cultural lenses about what participation will be in this PAR project. The name alone does not infer that everyone involved is on the same page.

These matters need to be clarified early in the process to create trust and mutual understanding and lessen the possibility of conflict, damaged relationships, and unsuccessful projects. Prior to these interactions and on a repeated basis, it would behoove the researcher to engage in critical self-reflection so as to continue to refine and develop a keener sense of self-awareness to become a better researcher (Fisher-Yoshida, 2009; 74–76). This is an iterative process and as relationships continue to build, it would strengthen the working relationship with others to engage in a dialogic critical reflection as a way to deepen mutual understanding and improve the quality of the relationship and work.

Another undertaking that needs to be done in order to ensure as much success as possible for all parties, is a skill and knowledge assessment. In the beginning and periodically throughout the engagement, there needs to be a shared understanding of what the parties need to know, what they need to do, how they will be held accountable, and how to get what is needed if not already present. During the ebb and flow of the project there will be different tasks along the way and at each of these junctures or turning points a review of the performance thus far and an eye toward what is on the horizon will benefit all parties, their working relationship, and the project.

Communities are complex systems and wanting to enact change so that violence ends and communities are transformed into safer spaces can be challenging. When you “poke” in one part of the system an outcome may happen somewhere unexpected and then unintended consequences arise. And just as it is challenging for an external researcher to learn and understand the complexities of a system of which they are not from, there is also an advantage of “otherness” being outside the system, that offers perspectives that cannot develop solely from within. Since systems are shaped by human agency, this entering into the system and disrupting it is bringing a sense of agency that will support emergence of different outcomes, such as transformation (Orton et al., 2019; 50). It can also foster higher levels of engagement when there is an appreciated aesthetic achieved.

Contribution to the Field

These considerations are relevant and important for several reasons. First, your mindset is critical because you need to assume there will be differences and enter into these engagements and relationships with curiosity and a mind to explore and discover. This may pose challenges as it is in your nature to judge partly because it is a survival instinct for you to determine whether you are safe, whether this is friend or foe; and to classify how you rank in comparison. Social norms and expectations have developed around these types of comparison so it is not only a matter of judging for survival, but also judging for preference. There are many ramifications of this type of judging and the rules of engagement have been set from so many experiences in the past they have a strong influence on the meaning making process.

Second, is that in order for the research to be fully participatory there needs to be a level of trust and respect amongst all of the people involved, including the researchers. This calls for respecting different forms of knowledge as relevant and important for developing shared understanding, buy-in, and interventions that lead to sustainable outcomes. Local knowledge is critical to informing the intervention ensuring that whatever is decided is culturally relevant to that particular community in that specific locale. Some of the learning can be generalized and adapted to other situations, but the essence of the intervention has to be localized. There are resources and practices characteristic of all communities and the transformation process changes the balance through introducing new resources and practices and getting rid of those that are no longer useful.

A third reason is about decision-making and in developing the ability at analyzing behavioral choices at differing temporal occurrences. There is the immediate reaction of being in the present moment and making a choice based on limited information. There is the near-term effect of this choice and then the longer-term effect for the lifetime of the relationship. It is easy to prioritize immediate decisions because you may respond in what Kahneman (2011, 20-24) refers to as system one thinking. When actions are done out of habit, there is a knee-jerk reaction so that when you say this, the other person does that. This perpetuates the patterns of communication that have existed and will continue to exist even if you and the other party in the communication stake claims that you want to change the dynamics. You are not giving yourselves opportunities to make those changes because you are responding at lightning speed without any conscious thought to what you are saying or doing.

If you slow down the process of your response to system two thinking, and have at your disposal tools that allow you to do this effectively, such as CMM hierarchy model, you will be able to make decisions that have more positive long-term effects. Positive effects are determined by aligning what you want to achieve as outcomes, both in the immediate situation, as well as, the longer-term relationship. This is influenced by the context in which it takes place and from which meaning is made, which is made more explicit when using the CMM hierarchy model. The key here is to slow down the process so that alternative actions and responses can surface and then you have the option of considering a different response from the norm. This slowing down the process also allows for other parts of your brain to kick in, such as the neo-cortex, which allows more rational levels of thinking to occur, rather than the emotional responses from the limbic system in the brain, which are more immediate as in system one thinking.

These actions together will forge better quality long-term working relationships and will help to really keep the focus on participation in participatory action research initiatives.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the author, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

You need to assume there will be differences and enter into these engagements and relationships with curiosity and a mind to explore and discover. Social norms and expectations have developed to make comparisons so it is not only a matter of judging for survival, but also judging for preference. In order for the research to be fully participatory there needs to be a level of trust and respect amongst all of the people involved, including the researchers. This calls for respecting different forms of knowledge as relevant and important for developing shared understanding, buy-in, and interventions that lead to sustainable outcomes. Local knowledge ensures that whatever is decided is culturally relevant to that particular community in that specific locale. There is the immediate reaction of being in the present moment and making a choice based on limited information. There is the near-term effect of this choice and then the longer-term effect for the lifetime of the relationship. It is easy to prioritize immediate decisions. If you slow down the process and have tools that allow you to do this effectively, such as CMM hierarchy model, you will be able to make decisions that have more positive long-term effects. BF-Y is the sole author of this publication, and revised, read, and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

J. M. Bennett (Editor) (2015). “Introduction,” in The sage encyclopedia of intercultural competence. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, xxiii–xxvii.

Caduff, C. (2011). Anthropology’s ethics: moral positionalism, cultural relativism, and critical analysis. Anthropol. Theory 11 (4), 465–480. doi:10.1177/1463499611428921

Chevalier, J. M., and Buckles, D. J. (2019). Participatory action research: theory and methods for engaged inquiry. New York, NY: Routledge.

Crippen, M., and Schulkin, J. (2020). Mind ecologies: body, brain, and world. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Deetz, S. (2014). “Power and the possibility of generative community dialogue,” in The coordinated management of meaning: a Festschrift of W. Barnett Pearce. Editors S. W. Littlejohn, S. McNamee, C. Creede, V. E. Cronen, R. Penmanet al. (Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press), 217–234.

Durie, R., and Wyatt, K. (2013). Connecting communities and complexity: a case study in creating the conditions for transformational change. Crit. Publ. Health 23 (2), 174–187. doi:10.1080/09581596.2013.781266

Fisher-Yoshida, B. (2014). “Creating constructive communication through dialogue,” in Handbook of conflict resolution: theory and practice. 3rd Edn, Editors P. T. Coleman, M. Deutsch, and E. C. Marcus (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass), 877–897.

Fisher-Yoshida, B. (2009). “Transformative learning in participative processes that reframe self-identity,” in Innovations in transformative learning: space, culture, and the Arts. Editors B. Fisher-Yoshida, K. Dee Geller, and S. A. Schapiro (New York, NY: Peter Lang), 65–86.

Gelfand, M. (2018). Rule makers, rule breakers: how tight and loose cultures wire our world. New York, NY: Scribner.

Orton, L., Ponsford, R., Egan, M., Halliday, E., Whitehead, M., and Popay, J. (2019). Capturing complexity in the evaluation of a major area-based initiative in community empowerment: what can a multi-site, multi team, ethnographic approach offer? Anthropol. Med. 26 (1), 48–64. doi:10.1080/13648470.2018.1508639 |

Pearce, W. B. (1989). Communication and the human condition. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

Pearce, W. B. (2007). Making better social worlds: a communication perspective. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Penman, R., and Jensen, A. (2019). Making better social worlds: inspirations from the theory of coordinated management of meaning. Oracle, AZ: CMMI Press.

Prakash, V. (2016). “Introduction: the importance of traditional and ethnic food in the context of food safety, harmonization, and regulations,” in Regulating safety of traditional and ethnic foods. Editors V. Prakash, O. Martín-Belloso, L. Keener, S. Astley, S. Braun, H. McMahonet al. (Amsterdam, NL: Elsevier), 1–6.

Wasserman, I. C., and Fisher-Yoshida, B. (2017). Communicating possibilities: a brief introduction to the coordinated management of meaning. Chagrin Falls, OH: Taos Institute.

WHO (2009). WHO guidelines on hand hygiene in health care: first global patient safety challenge clean care is safer care. Religious and cultural aspects of hand hygiene. Geneva, CH: World Health Organization, 17. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK143998/.

Keywords: participatory action research, culture, communication, context, relationships, trust

Citation: Fisher-Yoshida B (2021) Case Report: Are You One of Us and Can We Trust You?: Taking a Communication Perspective in Participatory Research. Front. Commun. 5:599286. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2020.599286

Received: 26 August 2020; Accepted: 21 December 2020;

Published: 27 January 2021.

Edited by:

John Parrish-Sprowl, Indiana University, United StatesReviewed by:

Rodger D. Johnson, Indiana University; Purdue University Indianapolis, United StatesArthur Jensen, Syracuse University, United States

Copyright © 2021 Fisher-Yoshida. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Beth Fisher-Yoshida, YmYyMDE3QGNvbHVtYmlhLmVkdQ==

Beth Fisher-Yoshida

Beth Fisher-Yoshida