- Institute of Communication Studies, Faculty of Humanities, University of Duisburg-Essen, Essen, Germany

The article presents results of a study on the dynamics between Donald Trump’s use of terms that relate COVID-19 to China and news media publications concerning this use. Qualitative content analysis with elements of discourse analysis was conducted to 1) describe the case as a type of populist discourse on COVID-19, and 2) illustrate the following hypotheses with the help of empirical material: 1) News media and the dynamics of political communication based on the difference of friend and enemy help legitimizing populist claims and directing public attention toward them while feeding into a narrative of a diffuse category of threats that creates objects of angst and thereby enhances social cohesion. 2) With resources derived from popular culture, populists exploit the culture of political correctness, which is facilitated through the ascription of authenticity. The hypotheses emerged in the course of organizing and preliminarily examining the data collected for an ongoing broader study on populist communication and its repercussions in different public spheres in view of the following assumptions: 1) Political communication is guided by the distinction of friend and enemy. 2) In populist communication, this distinction appears as the difference of ‘the people’ and allegedly corrupt elites, including news media. 3) Angst enhances social cohesion among the audiences of populist speakers directly or mediated by fear. 4) Populist communication is more likely to produce a type of fear that populists benefit from when it depicts the elite as a diffuse category composed of various interlinked enemies. Trump’s contextualized use of the following terms in the time period between March 13 and September 15, 2020, was examined: China flu, China plague, China virus, Chinese plague, Chinese flu, Chinese virus, Wuhan virus, and Kung flu. 38 speeches from Trump’s election campaign or rallies, 28 talks at presidential events or meetings, 47 interviews, 37 press conferences, 35 tweets and seven re-tweets as well as selected news media responses were subjected to analysis. The case has been successfully described as a type of populist discourse on COVID-19 and both hypotheses have been illustrated with empirical material.

Introduction

In the context of societal polarization, the term “populism” receives increasing attention—as a political battle cry and an analytical instrument in academic discourses. The term denotes a rather fuzzy concept that, however, is organized around a core meaning. Populists are considered persons, groups, and organizations that present themselves as advocates of the imagined community (Anderson, 2006) of the people who they contrast with allegedly corrupt elites.

Depending on the author, different attributes are added to this core meaning such as advocacy for direct forms of democracy (Crowther, 2018; Zaccaria, 2018), attacks on news media (Higgins 2017), the use of social media (Baldwin-Philippi, 2018), nativism (Betz, 2018), and an unorthodox relation to the truth (Harsin, 2018). Populism is often related to a certain emotional style, particularly a rhetoric of anger, resentment, and indignation (Canovan, 1999; Demertzis, 2006; Higgins, 2017; Betz, 2018; Zaccaria, 2018) that does not aim at guiding listeners to rational decisions but to emotionally driven actions. Despite its generally rather negative connotations, some authors describe populism as an agent of social change (Crowther, 2018) or as a phenomenon that is unavoidable in democracies (Canovan, 1999).

Dichotomizations like the one referred to here as the defining criterion of populism are no strangers to politics as suggested by Carl Schmitt’s concept of the political. Unlike economics with its leading difference of profitable and non-profitable and aesthetics with the difference of beautiful and ugly, to Schmitt (1963) political action is governed by the difference of friend and enemy. Likewise, the theme of emotions and politics accompanies the occidental history since the Sophists as a practical concern and has first been developed to a morally restrained psychagogy by Aristotle (1995).

Emotions provide in many ways the foundations for processes of “sociation,” a term derived from Simmel (1908). This is most obvious in the case of love in intimate relationships and families (Luhmann, 1983; Honneth, 2003). Even anger can provide the basis of human interaction such as in certain types of conflicts, particularly in quarrels (Kurilla, 2013; Kurilla, 2020a). Jealousy and envy, each in its distinctive way, are characteristic for certain types of communication processes in triangular relationships (Simmel, 1908).

The performance of fear as a medium of sociation is not so obvious although even Hobbes (1998) considers fear the means of state formation. Hobbes begins his “Leviathan” with an empiricist treatise on affects. Hobbes assumes that all humans share the same sensory equipment as well as related action tendencies. From this viewpoint, conflict arises because humans desire the same objects. This premise leads Hobbes to his conception of the state of nature in which homo homini lupus est. Hobbes’ state of nature subjects humans to a condition of perpetual fear of other humans. As a consequence, they use a considerable amount of their resources to protect themselves from each other. To Hobbes, perpetual fear combined with rational choice led humans to confer their innate, natural rights to a sovereign that governs human intercourse.

Following Montesquieu, Simmel (1908) underscores that fear holds together states, i.e., enhances social cohesion. Although Simmel uses the German term “fürchten,” he does not refer to a tangible, present object the emotion is directed to but rather to a diffuse threat. In German, the latter is considered an antecedent of “Angst” rather than “Furcht” which is related to a concrete threat.

Historical evidence supports this conception. Nazi propaganda exploits the cohesion enhancing performance of angst1 by condensing a multitude of inherently different opponents such as Jews, Marxists, financial elites, and the “mainstream” media to one single category of opponency. As a result, the threat associated with these opponents appears diffuse. In the inside views of leading Nazi officials, this condensation is necessary to avoid the dissipation of forces and paralysis, the latter being considered a negative consequence of fear.2 The pathologizing rhetoric of “Volkskörper” (body of the people) and “Hygiene” typical for Nazi propaganda strengthens the impression of a diffuse threat and thus potentially increases social cohesion fostered by angst. In a similar fashion, the security dilemma of the Cold War that was oriented on the axis of East/West and propelled by a Hobbesian anthropology can be understood as a play of forces that fosters inner cohesion and external closure. This might also hold true for George W. Bush’s rhetoric of an axis of evil.

Building on Heidegger (1962), Ahmed (2014) distinguishes between furcht and angst3 in a slightly different way. Furcht or fear “is felt [here and now] in the absence of the object that approaches” as an embodied “anticipation of [future] hurt or injury.” To Ahmed, fear becomes more intense when the object “passes by,” as it is not ‘contained’ anymore. Angst, in turn, is depicted as perpetual changes in the directedness to individual objects. “In other words, [angst] tends to stick to objects, even when the objects pass by. [Angst] becomes an approach to objects rather than, as with fear, being produced by an object’s approach.” From this perspective, the attachment to a range of different objects that is characteristic for angst can be considered the base of fear in concrete situations. In a given moment, fear can be elicited by Marxists as well as by financial elites, as the case may be, in narratives on sources of potential harm. The narrative fabrication of objects of fear marks boundaries between self and others. Fear, then, enhances social cohesion because it does not only move individuals away from the feared others but also makes them turn to the inside of their groups, to the beloved communities the individuals identify with and/or belong to.

Combining the two differentiations of angst and fear leads to the following apprehension. Angst enhances social cohesion either directly as a result of a diffuse category of enmity or mediated by fear in the case of the appearance of a concrete object. In both cases, the narrative fabrication of a range of objects of fear fosters cohesion—either on the level of potentiality or on the level of actuality, to use a Husserlian (1950) distinction. Both conceptions explain how social cohesion benefits from the narrative fabrication of a wide category of interlinked enemies, which in both conceptions is related primarily to angst.

Despite its performances for the constitution of society and enhancement of cohesion, Rico et al. (2017), e.g., do not regard the listeners’ fear (or, respectively, angst) as an emotion that populism benefits from. According to these authors, fear does not motivate action but the cognitive examination of unclear circumstances. This argument neglects the sociation function of angst and the fact that even in evolution-theoretical accounts fear is often connected to flight behavior. Zaccaria (2018) does recognize the functionality of a rhetoric of fear. He describes how the threat of losing important goods can translate into aggressions toward the people allegedly responsible for the feared loss. Zaccaria, however, also does not pay tribute to the sociating effects of fear.

These considerations can be condensed to the following assumptions. 1) Political communication in general is guided by the distinction of friend and enemy. 2) In populist communication this distinction appears as the difference of the people and allegedly corrupt elites, including news media. 3) Angst enhances social cohesion among the audiences of populist speakers either directly or mediated by fear. 4) Populist communication is more likely to produce a type of fear that populists benefit from when it depicts the elite as a diffuse category composed of various interlinked enemies.

In the course of the preparations for a broader study on populist communication, data have been collected of publicly available political communication. The data comprise communication offers of governmental officials, news media publications, influential social media content, and public protest messages. The process of organizing and preliminarily examining the data in view of the theoretical preconceptions outlined above led to the tentative formulation of the following hypotheses: 1) News media as well as the dynamics of political communication based on the difference of friend and enemy help legitimizing populist claims and directing public attention toward them while feeding into a narrative of a diffuse category of threats that creates objects of angst and thereby enhances social cohesion. 2) With resources derived from popular culture such as reality TV, commodities, and pop songs, populists exploit the culture of political correctness, which is facilitated through the ascription of authenticity4 (preliminarily understood in the everyday language sense as the interpretation of action as not governed by social norms or expectations but by the actor’s genuine inclinations and convictions).

The dynamics between Trump’s use of terms like “China virus,” “Chinese plague,” and “Kung flu” that relate COVID-19 to China and news media publications concerning this use were chosen to 1) describe the case as a type of populist discourse on COVID-19, and 2) illustrate the hypotheses with the help of empirical material and thereby concretize them in relation to a single case. In the context of the broader study, this is an exploratory process in a double sense. Firstly, hypotheses can be modified and refined during later stages of research. Secondly, the described case will be compared to other cases and revisited for conceptual modifications.

To reach its aims, the study relies on qualitative methods that guarantee the necessary openness for irritations from the field and allow for conceptual modifications that render theoretically guided drafts of categories more adequate in view of the data. Qualitative content analysis combined with elements of discourse analysis has been chosen as the primary method. On the foundation of the understanding generated by this method, a non-positivistic sequence analysis that sheds light on the dynamics of political communication was conducted. The details of the methods and their methodological justification are described in the next section.

The rationale for choosing the dataset is as follows. The author’s previous research traced the relations between political communication and fear theoretically (Kurilla, 2019). For its manifold relations to fear in public discourse as well as its politicization by various actors, the pandemic delivers an excellent occasion to observe these relations empirically. The dataset provides researchers with the opportunity to observe and analyze how the theme of COVID-19 becomes intertwined with other politically relevant topics, particularly with China, and how friend/enemy-lines are organized along one thematic string. The latter becomes obvious in the time preceding political elections when the friend/enemy divide is very pronounced. Moreover, the COVID crisis is an unprecedented situation evolving in a highly dynamic environment with multiple repercussions in political communication, giving researchers the chance to study the emergence of a controversial theme and of its discursive ramifications. In Trump’s entire public communication, expressions like “China virus” appear for the very first time on March 13, 2020. A time period of 6 months has been chosen as a sample for three reasons. Firstly, the contents of Trump’s public communication become increasingly repetitive and redundant towards the end of the sample. Secondly, 6 months seems to be a time frame long enough to observe the emergence of themes and their ramifications but, at the same time, not too complex to handle in a qualitative study. Thirdly, 7 weeks prior to the elections relevant themes seemed fully emerged to a point when candidates were prepared to communicate canonized building blocks of their campaign contents. Consequently, it seemed very unlikely that the increase of data complexity due to higher frequencies of communicative events towards the end of the campaign would have been compensated by new insights.

Trump’s remarks on China occur amid rising tensions between Beijing and Washington. Considering China’s rise as an economic and military power and its geopolitical moves, these tensions could be seen as mere competition between two global powers. There is, however, also an ideological element at work that has strained the relations between the two countries from the beginning. This is not so much related to China’s self-understanding as a socialist country, as Washington’s early approaches to Beijing served primarily to drag Beijing further away from Moscow to establish a new balance in the Cold War. The US administrations from the 1980s and the 1990s may have criticized China for its human rights violations every now and then and enacted sanctions upon the country, especially after the Tiananmen Square incident in 1989, but economic relations flourished. After 9–11, the United States and China even joint forces in the fight against global terrorism. Issues of economic competition were discussed more intensely in the wake of the global economic crisis. Despite concerns about a possible manipulation of Chinese currency in order to increase exports, strategic collaborations on security and environmental issues predominated.

Intellectual property rights, human rights, and issues of cyber security were topics of concern occasionally but were never taken so seriously as to govern the relations to Beijing. China’s seemingly unstoppable rise as an economic power in the last decade, however, fundamentally questions a narrative of US politics and highlights a complete misunderstanding of China. The narrative depicts democracy and a free market as preconditions of prosperity and the “good life.” If China achieves both with a one-party system and a state-directed economy, this narrative loses its evidence. Others could follow China’s example, so that its model would eventually spread. As a result, international politics could change to the extent that illiberal countries become the majority in international organizations or establish an “alternative institutional architecture” (Barma and Ratner, 2006). Vukovich (2012) shows how a misconception of China as “becoming the same” as the United States has been underlying US foreign policy. According to Vukovich, even the 1989 protests in China were fueled with more Maoism than ‘the West’ was able to comprehend. To Vukovich (2019), illiberalism is a Chinese achievement established in a long series of social quarrels. In addition, the Chinese collective identity suggests that China has its own way in everything it does. Accordingly, China does not just take things from the outside but renders them Chinese. Pragmatism combined with the notion of efficiency have long been internalized in a very Chinese way. The undeniable efficiency of China’s handling of the COVID-19 crisis once again questions the narrative of liberalism automatically producing the most efficient forms of government. In this context, it comes to no surprise that China became an election topic of both sides of the political aisle in the United States.

Materials and Methods

The study follows a qualitative methodology, as the hypotheses are not formulated to be falsified but emerged during research based on an abstract theoretical framework and can be modified in view of additional data and insights. The case study is illustrative in nature and not quantitatively representative. The case and its characteristics, not their frequencies in social reality are the subjects of study. This approach pays tribute to Kelle’s “empirisch begründete Theoriebildung” inspired by Glaser and Strauss (2009) and Strauss and Corbin (1998) as well as to Popper (2002) depiction of a “quasi-inductive evolution of science.” From the viewpoint of quantitative methodology, the study can be considered explorative.

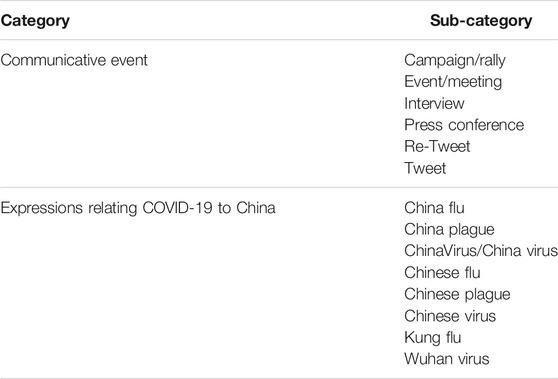

Eight expressions were identified that Trump uses to relate COVID-19 to China: China flu, China plague, ChinaVirus/China virus, Chinese plague, Chinese flu, Chinese virus, Wuhan virus, and Kung flu. All of Trump’s public references to COVID-19 with these terms between March 13 and September 15, 2020, were identified with the help of transcripts from the database factba.se. None of the terms had been used prior to this time period. The broader contexts of these references were examined in the transcripts as well as the corresponding video and audio recordings. The data were organized in a table for each of the terms where the date and the type of communication event were specified. The tables helped to asses and graphically depict the frequencies of use for each term.

Subjected to analysis were 38 speeches in the context of Trump’s election campaign and rallies, 28 talks at presidential events or meetings, 47 interviews, 37 press conferences, 35 tweets and seven re-tweets. The data were partly dialogic in nature, so that the interactive fabrication of Trump’s remarks could be examined. In order to highlight the dynamics between Trump’s utterances and news media publications, reactions of the press were included into the dataset. Additional data were obtained from a White House press conference where Trump’s use of the term “Kung flu” was discussed, although Trump was not present. The concerns raised by news media and the press secretary’s reactions to these, however, form part of the sequence of Trump’s statements and news media resonance.

MAXQDA2020 was used to organize the data and conduct qualitative content analysis with elements of discourse analysis. The content analysis was oriented on Mayring (2010). Following Lamnek’s (1995) critique on this procedure, however, the categories of analysis have not been entirely determined prior to analysis. Instead, the theoretical framework was rather abstract as outlined above, allowing to be adapted to irritations from the data during the process of analysis.

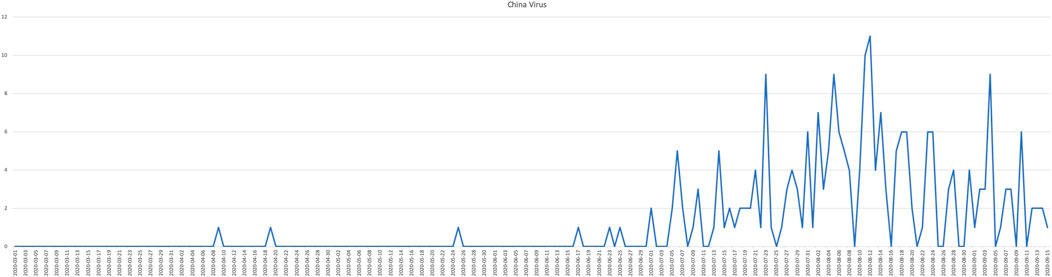

The eight categories of terms relating COVID-19 to China and six categories for communicative events were used as the base to organize the data (see Table 1). 174 additional categories emerged from the data in view of the broader contexts and were used for coding. A total of 1,613 segments were coded with the 188 codes in this step. Multiple coding of segments allowed a single segment to be viewed from different category contexts. In the next step, the categories were organized around 28 themes that emerged during analysis. Of these 28 themes, 15 were subsumed under three broader themes (see Table 2). In this process, the total number of coded segments was reduced to 1,575, as some categories seemed to be irrelevant for the present study and others were merged with other categories. For a complete overview of all themes, sub-themes, sub-subthemes, descriptions of categories, and samples of coded text please refer to Supplementary Table S1.

The outlined procedure bears elements of discourse analysis in three regards, which will be explained in the subsequent paragraphs after introducing the underlying understanding of discourse analysis. To Foucault (1969), discourses are social practices that create objects and distribute scarce resources, which relates them to power and makes them objects of political battles. Foucault might have focused more on the power aspect of discourses in his later works (Foucault, 1976; Foucault, 1991), but without the aspect of the creation of objects, discourse analyses would be deprived of its matter. In his influential work on the discourse analysis of the sociology of knowledge, Keller (2011) also emphasizes the link between knowledge (of objects) and power. His method, however, rather prioritizes the analysis of discursive power relations. Unlike Keller, the analysis employed here is concerned with the discursive formation of objects and disregards its relation to power. Unlike linguistic discourse analyses, the analysis is not primarily concerned with identifying linguistic devices such as speech acts or tropes but with the formation of objects and thus acts as a method of the sociology of knowledge, which undeniably bears some hermeneutical aspects.

1) The content analysis was informed by discourse analysis in the sense that it connected Trump’s utterances to broader discursive sources instead of trying to interpret them in as individual entities. Without the knowledge of, e.g., Western discourses on China or the neoliberal economic discourse, it is very unlikely that the content analysis would have been faithful to its data. According to Foucault (1969), however, these elements of different discourses can only be considered as such when they appear in their proper discursive contexts. In the same manner, an argument from the evolution-biological discourse ceases to be a part of this discourse when it is used to justify jealousy in a quarrel among romantic partners (Kurilla, 2020b).

2) The content analysis was also part of a discourse analysis. The anatomy of political discourses was identified with the help of Schmitt who could also have been consulted to classify economic, aesthetic, etc. discourses by recurring to their leading differences. Other authors were consulted regarding the characteristics of populism. In other words, the theoretical background helped to identify parameters to describe Trump’s communication as a political and populist discourse. Orienting on these parameters, the content analysis not only examined the contents of speech but also identified themes and narratives as elements of discourse as a means to constitute objects.

3) Discourse analytical considerations also provided guidance to conduct the analyses of communication sequences. Unlike some adherents of conversation analysis seem to suggest (see Flader and Trotha, 1988), sequences of communication do not emerge from the data. Their discovery rather depends on preconceptions. Without the knowledge of the workings of discourses of political correctness, e.g., some of Trump’s utterances could not adequately be set in relation with neither comments and publications of news media nor their communicative environments in general.

Considering the size of the dataset, more themes may still emerge from the data during further analysis. For the purpose of the current study, however, the author is confident that a sufficient level of theoretical saturation in the sense of Saunders et al. (2018) has been reached and that possible additional themes do not concern the focus of research.

Results

Trump’s public utterances are increasingly repetitive in the time period under consideration. The basic themes in the context of expressions that relate COVID-19 to China, however, were present almost from the start. Narratives were adapted to new situations but did not fundamentally change. This section starts with a chronology of events. Subsequently, Trump’s claims of being a people’s president will be examined, followed by an analysis of how Trump depicts the people’s enemies. The section concludes with a depiction of how Trump exploits the culture of political correctness with the help of popular culture.

A Chronology of Events

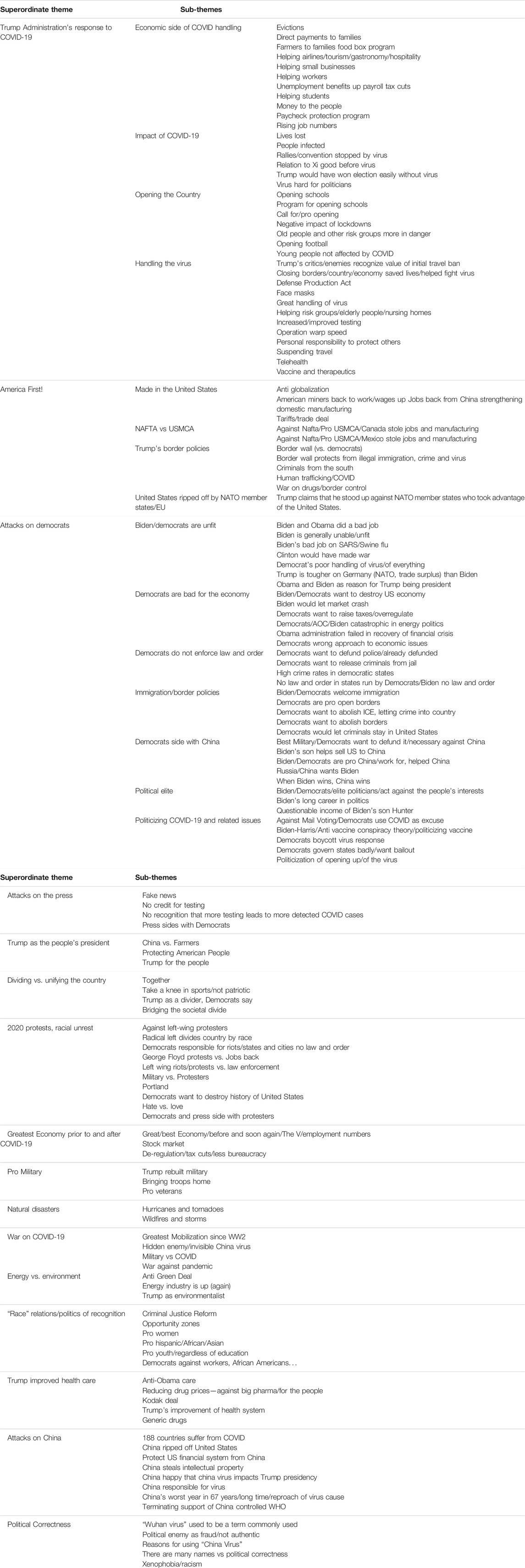

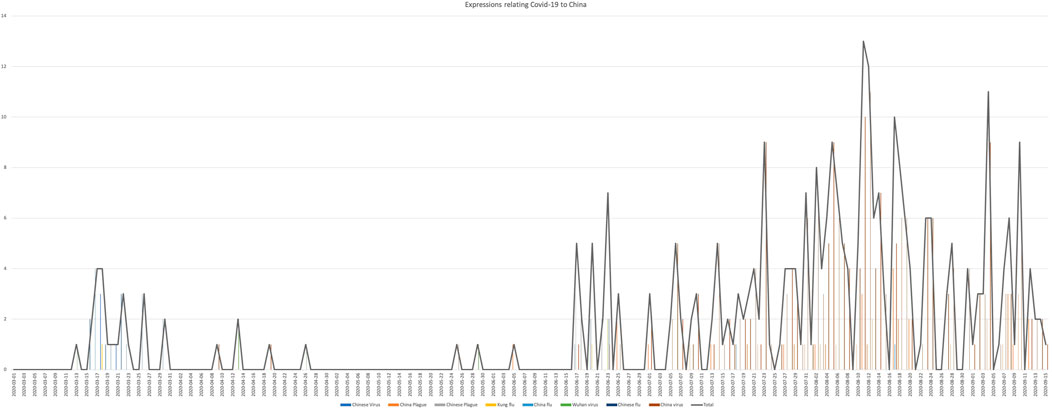

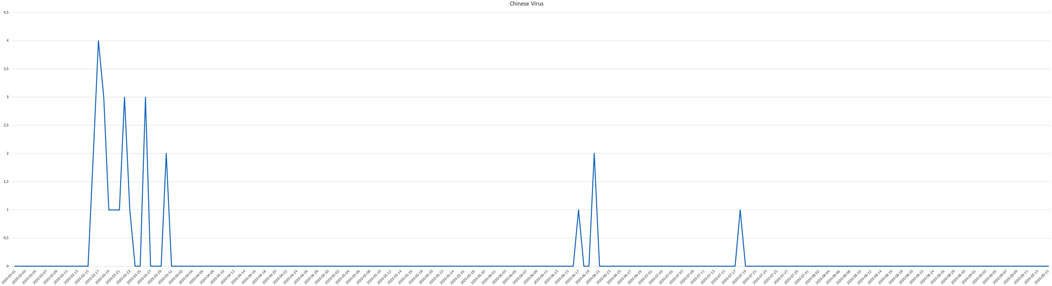

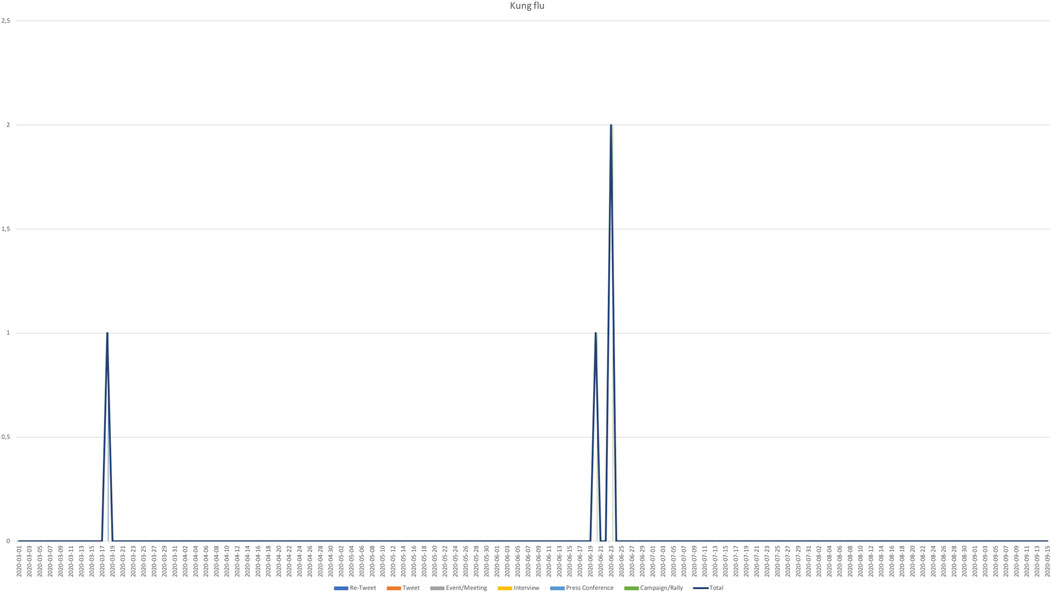

In the period between March 13, and September 15, 2020, Trump used the expressions under consideration 319 times in public. The expression “China virus” was used 228 times, “China plague” 43 times, “Chinese virus” 25 times, “Chinese plague” nine times, “Wuhan virus” five times, “Kung flu” four times, “China flu” three times, and “Chinese flu” twice. See Figure 1 for an overview of the frequencies of use over time. “China virus” appeared first on April 9 and later became the most frequent expression (see Figure 2), replacing “Chinese virus” which had been used 21 times before and subsequently only four times (see Figure 3). The first expression used was “Wuhan virus” that subsequently was only used four more times. “China plague” appeared first on June 5 and was used 42 times thereafter. “China plague” was only employed nine times between June 17 and June 22. The peak of the use of “China virus” begins on July 1. The sharp rise starting in mid-June results partly from the increase of Trump’s public appearances in the context of his election campaign and the fact that he resumed regular press conferences on COVID-19 which had been suspended before. Just at the beginning of this rise in use, Trump employed “Kung flu” three out of a total of only four times (see Figure 4). This case is particularly insightful for understanding the dynamics of populist communication as will be detailed below.

On March 13, a retweet of Trump campaign “rapid response director” Andrew Clark emerges on Trump’s twitter account: “Oh no! CNN’s reporter just called it the ‘Wuhan virus’ and added ‘which originated, as we know, in Wuhan, China.’ Someone call @Acosta about this blatant xenophobia! […]” This tweet is linked to a video in which a CNN reporter announces that “the Chinese government” claimed that “the US military could be to blame” for COVID-19. The first appearance of “Chinese virus” in an actual tweet occurs on March 16, announcing that the Trump administration will support the industries affected by COVID-19. Another tweet from the same day blames New York governor Cuomo for politicizing the virus. On March 17, three tweets appear on Trump’s twitter account, assuring that the economy will be stronger than ever after the pandemic. The tweets also assert that Trump’s handling of the virus is flawless and that news media create a negative public opinion: “Many lives were saved. The Fake News new narrative is disgraceful and false!” On the same day, during a meeting with representatives of the tourism industry, Trump again claims that his administration handled the crisis very well. The theme of helping workers, industries, and small businesses affected by the virus is also present here. Trump further states that COVID-19 has unified Democrats and Republicans in the fight against the virus, introducing a war metaphor and depicting the virus as “the hidden enemy.” Also present here is the motif that the Trump administration created “the strongest economy on Earth” that may currently be affected by the virus but will rise to new heights.

On March 18, a tweet of Trump’s account announces that he signed the “Defense Production Act” enabling him to use resources from the private sector to combat the virus, underlining that “we are all in this TOGETHER!” Beside emphasizing his alleged achievements regarding telehealth, he introduces the theme of increasing domestic manufacturing, i.e. “Made in the United States,” in response to the virus, and again asserts that Democrats and Republicans are unified by the effort of overcoming the crisis. During a press conference on the same day, Trump places COVID-19 in the proximity of natural disasters for the first time.

More importantly, Trump’s states that he uses the term “Chinese virus” as a reaction to Chinese officials’ accusation that the virus “was caused by American soldiers.” In response to a journalist’s doubt whether Trump is not worried that the use of “Chinese virus” could have caused “dozens of incidents of bias against Chinese Americans,” Trump maintains that he uses the term not in a xenophobic or discriminating way but only to indicate that the virus originated in China, assuring that he has “great love for all the people from our country.” Interestingly, Trump responds to a question about a White House official’s alleged use of the term “Kung flu” by asking the reporter who this person was and, obviously not acquainted with the expression, to repeat the term.

During a press conference on March 19, Trump continues his attacks on the press and holds China explicitly responsible for the spread of COVID-19. In a press conference on March 20, Trump announces that he wants to “minimize the impact of the Chinese virus on our nation’s students” by not enforcing standardized exams and waiving the interest on student loans.

Media reactions regarding the terms under consideration are mostly negative. On March 18, The New York Times quotes “experts” who consider the use of “Chinese virus” dangerous for bearing racist connotations and provoking xenophobia. On March 20, The Washington Post takes a similar stance, citing “experts” who state that the term “Chinese virus” “is racist and […] creates xenophobia.” Similarly, Democratic congresswoman Judy Chu tells CNN on March 21 that using the term is dangerous, xenophobic, and results in violence against Asian Americans. On March 24, however, Maegan Vazquez from CNN writes that Trump would be “pulling back from calling novel coronavirus the ‘China virus.’”

Trump’s use of the terms actually decreases until mid-June. On March 26, Trump confirms in an interview that he did not intend to call COVID-19 the “Chinese virus” but wanted to underline that the pandemic originated in China and was not spread by US soldiers. During a press conference on the same day, Trump repeats this claim regarding the expression “China virus.” Trump reiterates this narrative during an interview on March 30, recognizing that he “wouldn’t say [the Chinese] were thrilled with that statement.” On April 9, the term “China virus” emerges on Trump’s twitter account although only as a re-tweet. In an attack on the press and the Democrats on April 13, Trump uses the term “Wuhan virus” but implies that it was the term commonly employed in January, which, as the data show, is not even true for Trump who started to use the terms under consideration on March 13. Trump defends his decision to issue “a travel restriction from China,” stating that members of the Democratic Party as well as news media considered this decision xenophobic and racist although, according to Trump, it saved lives and stands for his excellent handling of the crisis.

On April 19, a re-tweet on Trump’s twitter account is linked to an interview with Nancy Pelosi in which she justifies that she promoted visits to San Francisco’s Chinatown: “She calls it ‘the flu’ and says that calling it the China Virus is racist towards Asian Americans just as Xi Jinping ordered.” A similar re-tweet containing the term “Wuhan virus” appeared on Trump’s account on April 26. Almost 1 month later, on May 25, “China virus” is used in a tweet of Trump’s account although this time the use is far more cautious: “Great reviews on our handling of COVID-19, sometimes referred to as the China Virus.” On May 29, Trump attacks China and blames the country for letting the “Wuhan virus” escape. On June 5, Trump claims that “prior to the China plague that floated in we had [job] numbers, the best in history for African-American, for Hispanic American and for Asian American and for everybody. Best for women, best for people without a diploma, young people without a diploma, I mean so many different categories.”

Starting on June 17, the use increments extremely and is increasingly combined with a variety of themes. Asked what he could do to unify the country in view of race relations and the protests concerning the deaths of George Floyd and Rayshard Brooks, Trump simply refers to the economic situation prior to the COVID-19 crisis: “[W]e were doing phenomenally well, the economy was great, jobs were great, best unemployment rates we’ve ever had for African American, for Hispanic, for Asian, for women, for everybody […]. And then, we got hit with the Chinese virus […].”

Trump’s answer to the division of the country being to “get jobs back,” he points to the criminal justice reform and opportunity zones that his administration implemented to improve race relations. Trump combines similar views with attacks on the Obama administration in another interview on the same day. He also prides himself on negotiating a trade deal with China contributing to the economic success prior to COVID-19. During a roundtable session with governors on June 18, Trump assures that the economy will have a quick recovery (“in a V shape”). In a subsequent interview, Trump again blames “the Chinese plague” for worsening race relations by forcing the administration to close the economy. It follows an attack on Biden who Trump does not consider able to handle the ongoing protests.

At a rally in Tulsa, Oklahoma on June 20, Trump uses the term “Kung flu” for the first time without repeating it in response to a question like on March 18. “[This] disease without question has more names than any disease in history. I can name Kung flu. I can name 19 different versions of names. Many call it a virus, which it is. Many call it a flu, what difference? I think, we have 19 or 20 versions of the name[.]” Trump basically repeats this utterance during a campaign speech in Phoenix on June 23: “I said the other night, ‘There’s never been anything where they have so many names.’ I could give you 19 or 20 names for that, right? […] ‘Wuhan.’ ‘Wuhan’ was catching on. ‘Coronavirus,’ right? [Audience member shouts ‘Kung flu’] ‘Kung flu,’ yeah. [Applause] Kung flu. ‘COVID.’ ‘COVID-19.’ ‘COVID.’ I said, ‘What’s the ‘19’?’ ‘COVID-19.’ […] Some people call it the ‘Chinese flu,’ the ‘China flu.’ Right? They call it the ‘China,’ as opposed to ‘Chi-’—the ‘China.’” In both situations, the audience was very enthusiastic about these expressions.

The news media, however, took a different stance. The Guardian calls “Kung flu” “racist language” on June 21. On the same day, Business Insider refers to the expression as a “racist term.” Vox calls it Trump’s “latest effort to stoke xenophobia” on June 23. Critical voices also come from Daily Mail on June 21, NBC News on June 23, Sky News on June 24, The Globe Post on June 29, etc. During a press conference on June 22, White House press secretary McEnany confronts criticism by journalists regarding Trump’s use of “Kung flu.” Her justification follows Trump’s narrative: “What the president does do is point to the fact that the origin of the virus is China. It’s a fair thing to point out, as China tries to ridiculously rewrite history, ridiculously blame the coronavirus on American soldiers.” (rev.com) She goes on citing mass media using similar terms like “Wuhan virus,” “Chinese coronavirus,” “Chinese virus” on different occasions. Confronted with the claim that “‘Kung flu’ is extremely offensive to many people in the Asian-American community,” she asserts that “the media is trying to play games with the terminology of this virus, where the focus should be on the fact that China let this out of their country. The same phrase that the media roundly now condemns has been used by the media […].”

Trump as the People’s President

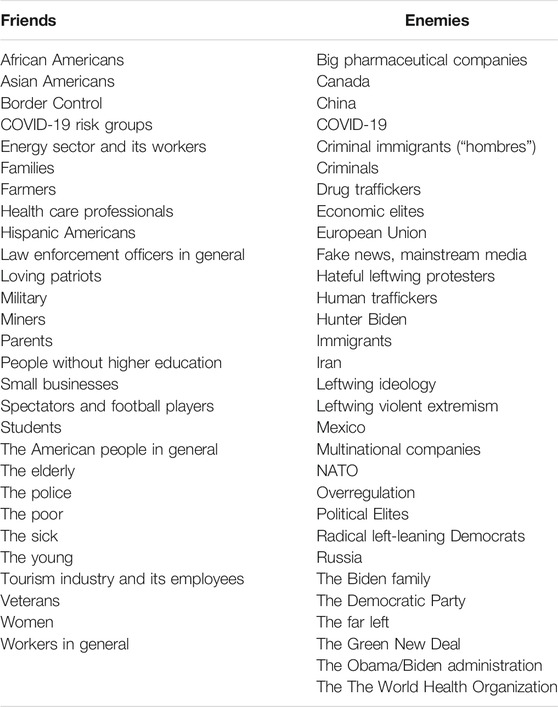

This section examines Trump’s depictions of his political friends or ‘the people’ whereas the next section is concerned with Trump’s portrayal of his political enemies. Table 3 gives an overview of Trump’s categorization of political friends and enemies as derived from the data.

The theme “Trump administration’s response to COVID-19” allows for insights into who Trump is, rhetorically, siding with. The sub-theme “Economic side of COVID-19 handling” is particularly insightful. One of the earliest topics that appears in Trump’s public statements is that he is supporting workers. On March 17, Trump states, “[m]y administration has taken decisive action to support American workers and businesses. We love our workers.” Until August 24, the topic appears 15 times in Trump’s statements. From June 17 to September 13, Trump constantly claims praise for rising job numbers. On March 20, Trump already announces that he will help students to cope with the situation by suspending interests on student loans. This theme becomes very repetitive between August 8 and August 12.

On March 16 and 17, Trump addresses his efforts of helping the tourism industry and its employees. “Helping small businesses” is also an early theme. Trump affirms to support those businesses and their workers on March 17 already and refers to it ten times until August 24. With regard to helping small businesses and their workers, he promotes his Paycheck Protection Program three times between August 12 and 28. “Direct payments to families” becomes an explicit topic on August 14. On August 24, Trump takes praise for the “farmers to families food box program” that supposedly helps both farmers and families.

Insights into who Trump sides with can also be obtained from the sub-theme “Handling the virus.” On March 21 he claims to take care of health care professionals involved in the response to the crisis. Between July 14 and August 9, Trump emphasizes 19 times that he takes special care of elderly people and other risk groups as well as the related institutions such as nursing homes and health care professionals.

The sub-theme of “Opening the country” also bears insights into what groups Trump supposedly considers his friends. According to Trump, opening schools helps parents as well as students, a topic he addresses at least 18 times between July 7 and September 10. The negative consequences of lockdowns like a rise in drug abuse and depression were addressed ten times between July 23 and September 13. Trump praises himself for promoting to allow football matches to support football spectators and players about four times between August 11 and September 10.

The broad theme “America First!” and the sub-theme “Made in the United States” are closely connected to Trump’s support of workers, asserting to bring “jobs back to America.” On July 9, Trump claims to have “an undying loyalty to the American worker,” supposedly shown by his efforts to stop companies from shifting production to China. Between March 18 and September 10, Trump prides himself 38 times on bringing jobs back to or keeping them in the United States, partly in relation to the Defense Production Act. Trump also refers to the trade deal he negotiated with China and the tariffs he imposed on the country that supposedly were implemented to help workers and farmers. This topic is addressed 25 times between March 26 and September 15. Trump explicitly addresses miners on August 17 and praises himself for having created jobs in the energy sector on June 20 and July 29.

The sub-theme “Trump’s border policies” depicts Trump as the defender of ‘the people’ against drugs, crime, illegal immigration, COVID-19, human trafficking, etc. It has been addressed from different angles 21 times. On July 23, Trump claims that “[t]here’s nothing more important in our country than keeping our people safe, whether that’s from the China virus or the radical-left mob […].” Accordingly, Trump claims to support law enforcement and the military on numerous occasions. At least in three situations, August 24, 27, and 31, Trump assures that he also worked to support military veterans.

Trump repeatedly claims praise for his support of minorities and vulnerable disadvantaged groups such as African, Hispanic, and Asian Americans (30 times) and women (13 times). While he addresses various groups as ‘the people,’ the manner in which he claims to help is rather homogeneous as clearly shown in the theme “Greatest economy prior to and after COVID-19.” He asserts in 82 contexts that he created the greatest national economy of all time prior to COVID-19 and will achieve a V-shaped recovery. The economy appears to be Trump’s answer to the political division of the country. On July 23 and August 18, Trump claims that race relations and relations among different political groups had improved due to a successful economy and have only suffered recently because of the economic impact of the COVID-19 restrictions. Trump attributes his supposed economic success to deregulations, tax cuts, trade deals, tariffs, and supporting national manufacturing. Another means Trump claims to help ‘the people’ with is the support of law enforcement, border control and the military.

The People’s Enemies

Trump holds China responsible for spreading the virus on many occasions. At least ten times, Trump claims that China had its worst economic year in 67 years while the US economy was at its best ever. He repeatedly accuses China of taking advantage of the United States. On May 29, e.g., Trump states that “China raided our factories, offshored our jobs, gutted our industries, stole our intellectual property, and violated their commitments under the World Trade Organization.” On June 23, Trump praises himself for opposing China: “I stood up to China like no other administration in history. For decades, they’ve ripped us off.” Trump frequently assures, e.g., on July 14, that his trade deal stopped China from taking $500 billion a year out of the US economy and that he forced China to buy goods for $240 billion from the United States. He subsequently implies that China could have intentionally launched the virus to resist the economic disadvantages resulting from the deal.

Similarly, Trump accuses Mexico (on July 18 and August 17) and Canada (on August 17) of stealing US jobs and manufacturing. On September 10, Trump blames the EU and NATO for stealing from the United States. A common denominator of Trumps attacks on China, Canada, Mexico, the EU, and NATO is that Trump insinuates that Democrats helped those countries and institutions to the disadvantage of “the people.” On June 16, e.g., Trump states that “nobody has been tough on China like I am. […] Look under Obama and Biden, they got away with murder.” In a similar manner, Trump asserts on September 3 that “we ended the NAFTA nightmare and signed the brand-new U.S.-Mexico-Canada agreement into law, which is in effect now and really doing well. […] I took the toughest-ever action to stand up to China’s pillaging from during and rampant theft of Pennsylvania and many other places’ jobs. […] Joe Biden’s agenda is made in China. My agenda is made in America.”

The data contain several additional attacks on Democrats. Trump accuses Biden on July 14 of opposing tariffs on Chinese products as well as Trump’s COVID-19 related, allegedly xenophobic travel ban. Trump also maintains that Democrats support China with their plan to defund the military. On September 10, Trump attacks Biden’s sun Hunter, accusing him of facilitating “the sale of a Michigan auto parts producer to a leading Chinese military defense contractor. […] China’s military got American manufacturing jobs, and the Biden family got paid a lot of money. And I said, ‘If Joe Biden ever got elected, China will own America.’ Between March 26 and September 10, Trump accuses Democrats in 25 contexts of aiding China. On July 17, Trump claims that Democrats “want to raise your taxes. They want to tear down our history. They want to absolutely get rid of our great history and they want to […] demolish our economy.” In 16 contexts, Trump criticizes the Democrats’ alleged plan to overregulate the economy and raise taxes, harming “the people” and businesses. Trump insists on six occasions that their policies would have a devastating impact on the energy sector and the jobs therein. Although Trump depicts himself as an environmentalist, he strictly opposes the Democrats’ environmental policies for their negative impact on the energy sector, e.g., on June 5: “the Green New Deal would kill our country.”

Trump further describes Democrats as unable to maintain law and order. On September 4, he accuses Democrats of planning to release criminals from prison. On various occasions, e.g., July 7, August 8, and August 18, he criticizes the proposal of defunding the police. On July 18 and August 19, Trump points to high crime rates in states and cities governed by Democrats. Trump also blames Democrats for their immigration and border policies. On August 18, Trump asserts that Democrats want to open borders, so that crime and drugs can enter and jobs leave the country. In six contexts, Trump turns against Democrats’ immigration policies for not being strict enough.

Trump depicts Democrats as elite politicians with no interest for ‘the people.’ He repeatedly (e.g., June 18, July 14, August 27) contrasts Biden’s long career in politics with his allegedly few achievements. On September 8, Trump alleges that Biden acts against the interest of African Americans: “Biden spent the last 47 years, betraying African-American voters. […] He closed the factories in Baltimore and sent them to Beijing. […] He shuttered the plants in Chicago and sent them to Shanghai.” As professional politicians, Trump asserts, Democrats neglect “the people” and even politicize the COVID-19 crisis, sabotaging Trumps’ efforts to support US citizens. On September 12, Trump accuses Democrats of letting people suffer for political reasons: “[A]n ungrateful Governor in New York, Cuomo, […] we sent him ships. […] We […] built a convention center with 2,800 beds and he […] hardly used the beds at all. He hardly used the ships at all […] and now he gets political.”

On August 8, Trump blames Democrats for not having supported his efforts of increasing “unemployment benefits, protecting Americans from eviction, and providing additional relief payments to families. Democrats have refused these offers. […] That has nothing to do with the China virus. […] Nancy Pelosi and Chuck Schumer have chosen to hold this vital assistance hostage on behalf of very extreme partisan demands and the radical-left Democrats, […].” A tweet from August 14, contains a similar reproach: “I am ready to have @USTreasury and @SBA send additional PPP payments to small businesses that have been hurt by the ChinaVirus. DEMOCRATS ARE HOLDING THIS UP!”

Only July 14, Trump accuses Democrats of politicizing the re-opening of the country in general and of schools in particular despite the psychological and economic impact a lockdown can cause. Trump makes a similar allegation on August 2: “We’ve already gained a record 7.5 million jobs. It’s a new record, despite the fact that the Democrats and Biden want to keep it closed […]. They want to do it for political reasons. After November 3rd, […] that’s Election Day […], you’ll find everything gets opened […], and you don’t want Joe Biden as your President. […] Who does want him is China, Iran, Russia.” The dataset contains 21 of these allegations.

Trump insinuates that Biden would not be able to contain protests: “If Joe Biden gets in, the far left, Democrats have total control over him […]. He’s a puppet, and they will get into power and they’ll destroy our country.” (August 5) On August 7, Trump blames a Democratic mayor for the escalation of the protests in Portland: “The disgraced mayor of the city has ordered the police to stand down in the face of rioters, leaving his citizens at the mercy of this mob. […] Mayor Wheeler has abdicated his duty and surrendered his city to the mob. […] Leftwing, violent extremism poses an increasing threat to our country, and we stop it […], but it’s an ideology we have to stop.” Trump contrasts the Democrats’ approach to handling the protests with his own deployment of federal forces, leading to numerous arrests that Trump assures will result in long prison sentences (August 19). On August 5, Trump distinguishes between his followers and his opponents by ascribing love and hatred: “The Democrats are consumed with hatred for our history, for our heritage and our constitution, our values, our police, our traditional values, our businesses, and most of all, the hatred for anyone who rejects their politically insane ideas, their dogma, but their ideas. They can’t stand it, but our movement is based on love of our country and our communities, our fellow citizens, and our American flag.”

The quotes above indicate that Trump depicts Democrats as unable to handle the situation, blames them for siding with the protesters, and thus identifies them with the radical left. The following quote from June 20 shows that Trump also considers the news media to be biased in favor of the protesters: “Americans have watch[ed] left-wing radicals burn down buildings, loot businesses, destroy private property injure hundreds of dedicated police officers. […] And injure thousands upon thousands of people, only to hear the radical fake news say, what a beautiful rally it was. And they never talk about COVID. […] You never hear them saying, they’re not wearing their mask. You don’t hear them say, as they’re breaking windows and running in. And then, when I say, the looters, the anarchists, the agitators, they’ll say, what a terrible thing for a President to say.”

The dataset bears numerous instances in which Trumps attacks the news media, e.g., for not reporting Trump’s achievements in handling COVID-19 (March 17, March 21, April 13, June 25, July 14, July 19, July 20, July 29, August 1, August 2, August 8, August 10, September 4, September 7, September 8, September 10), for being too politically correct (March 13, September 8), not reporting on the corruption related to Democrats (July 14), treating the administration disrespectful (March 19), generally distorting the truth (March 30, April 9, April 14), euphemizing the protests (June 18, June 20), being biased in favor of Democrats (August 6, August 17), falsely reporting on Republicans’ racial hatred (August 28), and even treating Lincoln badly during his presidency (September 8).

While the analysis above has shown that Trump’s utterances bear different categories of the people’s enemies, in the recipients’ eyes, the boundaries of these categories get blurred and are constantly mixed up in situated speech phenomena. Democrats, China, mainstream media, NATO, left-wing protesters, Mexico, Canada, the political and economic elites in general, etc. are characterized as enemies of “the people.” Numerous relations are laid out among those potential addressees of fear, so that they all fit into one category. According to the theoretical background of this study, this enhances cohesion either directly through angst or in the presence of the individual objects included in this category by fear.

Exploiting the Culture of Political Correctness With the Help of Popular Culture

Since the end of the 20th century, there has been a rapid change regarding the criteria for the ascription of authenticity. In many media formats, fiction frames and reality frames get blended. Documentaries resemble fiction films and, conversely, fiction films appear to be documentaries. The success of the film “Blair Witch Project” anticipates this development. In the same year, the show “Big Brother” initiates reality TV in Netherlands. Countless formats follow whose success is based primarily on the assumption that they show real emotions and not enacted ones, as even method acting has become identifiable as acting, that it is not convincingly authentic anymore. Once the acting of everyday life people has been unmasked as acting either, however, this propels the development of new ascription criteria. At first, a person might appear authentic when violating conventionalized norms. Then, someone might be considered authentic when following these norms, as this may seem to be a genuine expression of this person’s personal inclinations. The change of criteria for the ascription of authenticity may help to understand how a former actor became the president of the United States in 1981 and a reality TV star in 2017.

Through “The Apprentice,” Trump has created an image of himself as a merciless boss whose favorite phrase consists in an unemphatically enunciated “You are fired!” At the beginning of each episode, Trump already breaks with the moral imperative of modesty, bluntly demonstrating his decadent lifestyle as a billionaire. Even as a politician, Trump seems to be “shooting from the hip” and “calling a spade a spade” in disregard of politeness and diplomacy. Paying tribute to a supposedly common, everyday reality with a seemingly nonreflective use of language may facilitate the impression that Trump genuinely cherishes the taste, lifestyle, and concerns of “the people.” Trump’s treatment of a friend as a friend and an enemy as an enemy might violate conventions of courtesy and the imperative of political correctness, but it earns him the quality seal of authenticity. The left’s renunciation of a politics of redistribution in favor of a politics of recognition (Fraser, 2003) surely helps turning political correctness into a target of populist attacks. Some parts of society feel left alone by politicians that seem to prefer categorical ideals to people.

The dataset shows that Trump violates the expectations of political correctness in numerous situations. This is most obvious when Trump uses the terms under consideration and becomes particularly visible as a breach of expectations when he is criticized like during a press conference on March 18: “Question: Why do you keep calling this the ‘Chinese virus’? There are reports of dozens of incidents of bias against Chinese Americans in this country. […] Trump: Because it comes from China. Comment: People say it’s racist. Trump: It’s not racist at all. […] It comes from China. That’s why. […] I want to be accurate. […] I have great love for all of the people from our country. But […] China tried to say […] that it was caused by American soldiers.” Trump banalizes the use of the terms just like in the following quote from March 26: “I talk about the Chinese virus and, and I mean it. That’s where it came from. You know, if you look at Ebola, if you look at […] Lyme. Right? Lyme, Connecticut. You look at all these different, horrible diseases, they seem to come with a name with the location. And this was a Chinese virus.” On March 30, Trump again affirms that he locates the origin of COVID-19 in China with the help of the expression “Chinese virus” to repudiate the claim that the virus originated among US soldiers. Identifying his own statements as “very strong against China,” Trump evokes the impression that he stands up against injustice in spite of unfavorable consequences.

Trump depicts Biden’s behavior as the opposite of Trump’s self-proclaimed straightforwardness, effectiveness, and disregard for political correctness: “As Vice President, Biden opposed tariffs, and he was standing up for China. He didn’t want to do anything to disrupt the relationship with China, even though China was taking us to the cleaners. He opposed my very strict travel ban on Chinese nationals to stop the spread of the China virus. He was totally against it. ‘Xenophobic,’ he called me. ‘Xenophobic.’” (July 14) Trump typically asserts that the media side with the Democratic party, hypocritically condemning him in the name of political correctness: “So, on January 17th, there wasn’t a case, and the fake news is saying, ‘Oh, he didn’t act fast enough.’ […] [W]hen I did act, I was criticized by Nancy Pelosi, by Sleepy Joe Biden. […] In fact, I was called xenophobic. […] I was called other things by Democrats and […] by the media, definitely. […] On January 21st, […] there was one case of the virus. At that time, we called it the ‘Wuhan virus,’ right? Wuhan” (April 13).

These examples also show that Trump uses the accusations of his opponents to victimize himself. Trump depicts his accusers as acting out of political reasons, endangering the wellbeing of ‘the people’ for their own goals. This is also exemplified by the following exchange from July 22: “Question: […] Would you like to respond to Joe Biden, who, today, described you […] as the first racist to be elected President. […] Trump: […] it’s interesting because we […] passed criminal justice reform, something that Obama and Biden were unable to do. We did opportunity cities.”

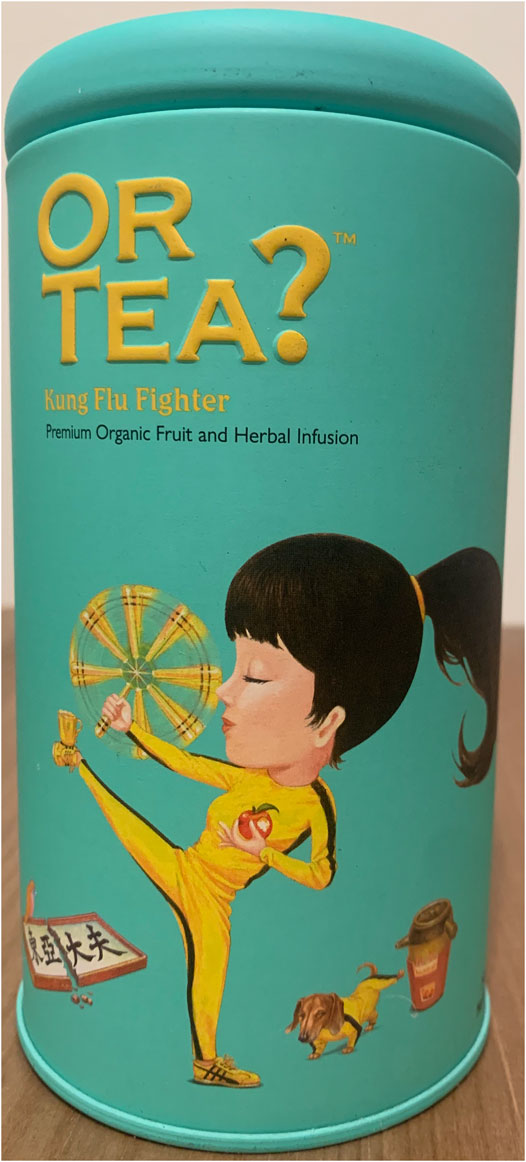

As shown above, the use of the term “Kung flu” was heavily criticized even before Trump actually used it. In fact, Trump used the term only on two occasions in the context of his campaign in June. Subsequently, Trump repeatedly suggested that COVID-19 had a lot of different names (July 10, July 13, July 14, July 15, July 17, July 18, July 23, August 4, August 8, August 12, August 13, August 18, August 24). This draws the attention of the audiences to both Trump’s courage to use politically incorrect terms and to the criticism from his opponents. Attacks on various actors that Trump depicts as ‘the people’s’ enemies are condensed in just one instance of speech. The term “Kung flu” is present as an implication. The term is not even an invention of Trump or his supporters but rather a resource obtained from popular culture that, in other contexts, does not at all bear racist or xenophobic connotations, which marks Trump’s opponents as being hypersensitive. There is, e.g., a herbal infusion that is branded as “Kung Flu Fighter” the packaging of which presents a caricature of an apparently Asian female fighter dressed like the main character of the film “Kill Bill” by Quentin Tarantino and placed in an environment humorously adorned with Chinese iconography (see Figure 5). The author could not find any negative remarks on this tea brand or reproaches of racism. Before Trump used the term “Kung flu” on June 20 and 23, several video parodies of the song “Kung Fu Fighting” by Carl Douglas as “Kung Flu Fighting” appeared on the Internet. The popularity of this resource alone indicates that “Kung flu” could resonate with Trump’s audiences and thus act as political capital.

Other means obtained from popular culture that enable Trump to counteract the culture of political correctness and thus provoke sympathy among his followers are his designation of Joe Biden as “Sleepy Joe Biden” (e.g., April 13, August 12, September 2) of Nancy Pelosi as “Crazy Nancy” (August 2, 3, 11) and of the mainstream media as “lamestream media” (June 18, July 29).

The news media are very likely to report and comment on such transgressions of norms, which provides Trump with additional attention. Clips of Trump’s behavior are repeatedly shown on television and shared on the Internet. News media may criticize what Trump does, but this does not determine how different audiences perceive and evaluate his actions, since media content is necessarily polysemic (Barker 2001). The process of meaning making takes place on the listeners’ side (Schmitz, 1994, Schmitz, 1998) and depends, among other things, on their characteristics, the reception context, and simultaneous and subsequent interactions. Some audiences may find a confirmation of Trump’s narrative that the media is “brutalizing” him when they see he is repeatedly criticized. Consequently, news media unwillingly provide Trump with a podium and facilitate his victimization. Provocations act as valuable tools of populist communication. Parallels to the criticism from the Democratic party may blur boundaries between journalists and Democrats in the eye of the beholder. Shared outrage about Trump’s use of “Kung flu,” “China virus,” etc. may lead some audiences to merge China, the “fake news,” and the “far-left” Democrats into one single category of enmity that threatens one’s standard of living, social prestige, and recognition.

Although journalists may indeed not be politically biased, they may still help populists to gain attention and become victimized. One of the classics of communication studies, the news factor theory and its derivates, might provide an explanation. Through their socialization, journalists learn what is newsworthy. Lippmann (1922) considers the characteristics of events themselves to be responsible for their news value whereas Schulz (1976) holds the journalists’ understanding of events responsible. Schulz’ criteria of prominence, conflict, relevance, etc. could be accountable for considering Trump’s provocations as newsworthy. Whatever the actual criteria may be, the academic and practical socialization of journalists influences their relevance structures (Schütz and Luckmann, 2017), so that it becomes foreseeable what, and sometimes in what way, they will report about. This is why provocations and even attacks on news media can, counterintuitively, help populists to instrumentalize them for their purposes.

Discussion

The study bears some limitations. No attention has been paid to the production processes of communication contents like, e.g., communication between Trump and his strategists and speech writers. Reception processes of different types of audiences were not examined. Interactive sense-making among audiences and their peers have not been studied either. The results can, however, be employed to sensitize researchers for relevant themes and discourses in the context of a thorough communication analysis.

The results regarding the emotional dynamics of populist communication have not emerged from the data or been obtained from the audiences’ viewpoints but were derived from the theoretical background presented in the introduction. This background can, however, be empirically strengthened in future studies by, e.g., examining whether audiences do in fact experience angst in view of references to enemies that Trump merges into one diffuse category. In this regard, the study is explorative.

The results clearly portray Trump’s utterances on COVID-19 in relation to China as populist discourse. It has been shown that, according to Trump’s narratives, he sides with workers, students, families, miners, African Americans, the elderly, women, etc., that is, “the people.” Trump draws a clear line between these categories and their supposed enemies which include political and economic elites such as NATO, the EU, the Democratic Party, the pharmaceutical industry, multinational companies, etc. Even in cases such as immigrants, criminals, and COVID-19 (the “invisible enemy”) in which the enemies do not belong to an elite collective, Trump presents them as being protected and supported by elites, mostly for personal gains, political reasons, or in the name of an ideology. News media, China and the Democratic Party constitute the primary targets of Trump’s attacks. They seem mutually supportive, inherently linked, and plotting against Trump and “the people.”

Trump also uses a rhetoric of anger, resentment, and indignation, which is not necessarily perceptible in his nonverbal expressions but can be inferred by the contents of speech. The antecedents of these emotions are usually described as an experienced injustice whereas the behavioral manifestations consist in standing up against it (e.g., Averill, 1980, Averill, 1986; Demertzis, 2014), which in the present case is expressed, e.g., by using terms that situate the origin of COVID-19 in China. Counterintuitively, the data did not show that Trump has an unorthodox relation to the truth regarding his claims that the media used some of those terms first. This fact supports Trump’s narrative of being unjustly persecuted by media and Democrats. Trump’s criticism of NATO and the EU may elicit the impression that Trump represents a thin type of populism (Dzur and Hendriks, 2018), aiming not at improving participatory institutions but at abolishing them. Closer examination reveals, however, that the results of the study, unlike Trump’s post-electoral behavior, are not conclusive in this respect.

US China policies served Trump as a vehicle of distinction from the Democratic Party long before the pandemic came into play. According to Trump, China stole employment, especially blue-collar jobs with the support of the Democratic Party. In Trump’s narrative, his protectionist implementation of tariffs on Chinese goods and the trade deal with China benefitted the domestic production sector, especially the workers. The antagonism between Trump’s discourse and the Democratic Party’s approach can hardly be described with classic distinctions such as neoliberalism/socialism. In Trump’s depictions, the Democratic Party pursues neoliberal policies, i.e. free trade, internationally and a bureaucratic state domestically while Trump aims at internal neoliberal policies and external protectionist policies or, put differently, internal deregulation and external regulation. Trump prides himself on deregulating domestic markets for the benefit of “the people” and rebukes Democrats for overregulating the domestic economy to the disadvantage of US Americans.

Trump’s logic becomes particularly obvious in relation to health care, as he states that unregulated competition of pharmaceutical companies would benefit “the people” more than a nationwide health care system like Obama Care which to him harms the economy and, as a result, the poor. He contrasts affordable medication through deregulation with regulated health care. This line of argumentation draws parallels between the Chinese approach of a state-directed economy and the policies of the Democratic party. According to Vukovich (2012), comparisons with policies that aim at state-regulated systems, especially to Maoism have a long history as a means of stigmatization, as they have been applied to extremisms like Nazism and Wahhabism. From this viewpoint, Trump’s depiction of ‘the Democrats’ as supporting the far left and its ideologies resembles the rhetoric of McCarthyism.

COVID-19 helps Trump to portray China as an adversary and to justify his policies. Trump explicitly holds China responsible for not containing the virus and for not informing the international community about the threat of a pandemic. He also insinuates that the virus could have been a response to his strict trade policies that benefited the US and harmed the Chinese economy. This claim alone would have disqualified China as an ally. Trump continues, however, to blame China for its insincere statement that the virus was spread by US soldiers, which he uses as a justification for employing terms like “China virus.” Despite the country’s alleged disregard for ‘the people,’ Trump suggests, the Democratic Party still sides with China and blocks his attempts of combatting COVID-19 for political reasons or personal interests, again merging both China and his domestic political opponents into one category of enmity.

Although even scholars like Schell (2020) suggest that particularly the rise of Xi Jinping renders the traditional “framework of engagement” of US China policy obsolete and creates the need for a paradigm shift, Trump overshoots the mark by denying common interests and reducing the relations between the two countries to one single dimension: an economic zero-sum game. Trump turns inward, redefining China as an adversary in the name of the people. He leaves the missionary project of supporting China to build prosperity by fostering democracy and a free market. The US ceases to be a “freedom-fighter and purveyor of enlightenment and universal human values.” (Vukovich, 2012) The narrative of “becoming the same” seems obsolete. From the viewpoint of past approaches to China, it might appear that China’s recent development made these adjustments necessary. The inside views of China, however, may suggest that China had been misunderstood in the past as assimilating, as being on the way to becoming like the West (ibid.). In this sense, Trump’s approach appears to be less colonialist and assertive regarding cultural differences. Expressed positively, Trump promotes an external politics of recognition (Taylor, 1994).

Whether China owes its success in defeating COVID-19 to its illiberal system does not matter to Trump who treats ideological conflicts rather as domestic affairs. He blames China only for hiding the danger of a pandemic and not containing it effectively. US external relations and international influence, however, may suffer from Trump’s recognition of authoritarian governments in two regards. On the one hand, liberal countries may feel betrayed because the US leave the shared path towards a democratic world order. On the other, China could set an example of an efficient state to copy or to cooperate with, without having to commit to liberal standards. Consequently, the international community may experience a shift toward authoritarianism, weakening the influence of democratic countries (Barma and Ratner, 2006). Turning inward, which is also mirrored by decreasing the engagement of the US in international military conflicts, disappoints the international allies. In Trump’s narrative, Democrats side with external partners for moral or power reasons to the disadvantage of ‘the people’ at home. Attacks on Trump’s foreign policy seem to confirm this narrative.

Trump turns those attacks into political capital, particularly when they are based on inappropriate assumptions. Trump rhetorically recognizes racial diversity as part of the nation, drawing the boundaries of the nation by culture, not by race. Blaming Trump for being a racist can backfire. The contemporary right promotes “cultural distinctiveness and diversity,” particularly with regard to the ingroup, which serves “as a rhetorical tool to counter charges of xenophobia, racism, and extremism.” (Betz, 2018) Traditionally a leftwing concern while particularly the conservative right tended toward an expansionist universalism, identity politics has gained territory in considerable parts of the political right. The sharp line that Trump draws is situated between internal diversity and external threats to it in the form of multiculturalism, crime, and predatory trade relations. Economic success seems to be Trump’s recipe to heal all types of social division. The reduction to the economic sphere is the basis of Trump’s “new realism” in the sense of “confronting reality ‘as it really is’ rather than as it is being constructed by the elite; breaking taboos, and speaking out frankly about societal ills; standing up for ordinary people and their common sense; and […] affirming the positive sides of the Western value system and of national identity” (ibid.).

New realism is directed against ‘hegemonic’ institutions such as news media, academia, the political establishment, etc. As postulated in H1, Trump’s populist discourse as outlined above is, counterintuitively, partly sustained through attacks by news media and the dynamics of political communication. It has been shown that the working logic of news media is to a certain degree predictable and can thus be exploited. Provocations such as “Kung flu” resonated among journalists, and their reactions aided in dragging attention to Trump and fed into Trump’s narrative of a diffuse threat composed of various antagonists including news media, the Democratic Party, and China. Similarly, it is likely, due to the dynamics of political communication, that the opposition criticizes its political enemy, blocking its proposals whenever possible, even in times of crisis. Trump depicts the reactions of Democrats to his suggestions to solve the COVID-19 crisis as sabotage motivated by political reasons alone, asserting that Democrats belong to the elitist enemies of the people. Any response by Democrats that is based on the difference of friend and enemy feeds into this narrative and the narrative of victimization.

H2 has also been illustrated with empirical material. It has been shown that Trump uses the culture of political correctness to his advantage by provocatively transgressing norms, which facilitates the ascription of authenticity. “Chinese virus,” “China virus,” etc. provoked public indignation among news media and politicians, seemingly confirming that Trump’s opponents are hypocritical and as such part of an intellectual, political, and economic elite that follows its own interests, no matter at what cost for “the people.” Trump, in turn, seems to say things “how they are” and to follow a disenchanted zero-sum approach instead of distorting facts to please the expectations of an elitist etiquette, disguising reality: “It comes from China. I want to be accurate.” This approach breaks with the culture of political diplomacy, fostering direct confrontations. As shown by Trump’s use of the term “Kung flu,” Trump obtains resources for “authentic” communication from popular culture. Numerous references to other elements of popular culture such as football, actors, humor, etc. are present in countless excerpts of Trump’s public utterances, which might evoke the impression that Trump genuinely cherishes the taste, lifestyle, and concerns of ‘the people.’

The current discordance and barriers of US political communication is symptomatic for the contemporary emotional climate of public communication in general. Seemingly unspectacular events provoke enormous public indignation. There is rising tension between the increasingly prominent imperative to be sensitized or “woke” regarding moral transgressions, particularly in language use and the resistance against it that considers this imperative the outcome of a “cancel culture.”

Some of the reasons for this heated emotional climate might lie in the changes in the political landscape. According to Fraser (2003), the left has shifted toward a politics of recognition, giving up their politics of redistribution. This includes a shift to multiculturalism. “The ethnopluralist claim has allowed the radical right to redefine the enemy and redraw the antagonistic field of contestation central to populist discourse. For the radical right, the traditional left-right conflict has largely become obsolete, having been replaced by a new front line pitting the defenders of identity against the advocates of multiculturalism.” (Betz, 2018) As has been shown by the example of Trump, the contemporary right engages in identity politics, capitalizing on the opposition of news media and political elites by promoting itself “as the lone voice of ordinary citizens […]; as indefatigable advocates of the silent majority, victimized by multiculturalism and political correctness” (ibid.).

The change toward a politics of recognition also implies that the left turns its back on its formerly most important group of voters, the workers. As a result, some may feel underrepresented by politicians and search for alternatives to restore their former status. To Knobloch (2018), the left has adopted a neoliberalist worldview, promoting free trade on a global scale. This gives the populist right the chance to attract those who feel abandoned with simplistic programs to nationalize production, impose tariffs, bring back jobs and manufacturing, etc. Although their solutions might not be viable in nowadays’ interdependent world, they lure the “abandoned” into a counterfactual trap of nostalgy and simple structures. Even though some of the protagonists of these populist movements like Trump have profited from international trade and cheap production abroad, their proficiency of playing on the partiture of authenticity seems to obfuscate this fact in the eyes of their followers, eliciting angst of a diffuse enemy that lurks on every corner.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

RK drafted the manuscript, designed the study and participated in each of its phases, and participated in the review and revision of the manuscript, and has approved the final manuscript to be published.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the reviewers for their valuable comments and the Institute of Communication Studies at the University of Duisburg-Essen, particularly Jens Loenhoff, for the inspiring intellectual exchanges and the fabulous working conditions.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2021.624643/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1Emotions terms set in italics indicate that they are employed as a catachresis for a word of another language or speech community.