- University of Duisburg-Essen, Essen, Germany

Despite the challenges of connectivity and the digital divide that persists in Central Africa, an increasing number of citizens is engaging and interacting in social networks for fulfilling their informational needs. In these contexts, connected independent journalists act as gatekeepers linking the virtual and the physical offline spaces of the orality and mythical traditions of their societies. Myths are a way of making sense of reality and in times of crisis, lack of information truthfulness can open the gateways for uncertainties and disorientation. A more culture-centered approach to social media may provide an opportunity to halt misconceptions in these contexts serving as a corrective mechanism against false information. This paper asks: How do fact-checkers combat/halt Covid-19 myths and misconceptions in the Democratic Republic of Congo and the Central African Republic? How do they engage in social media networks toward sense-giving and sharing corrective information? It discusses two cases of online media projects, ‘Congo Check’ and ‘Talato’, led by independent journalists that combine fact-checking skills when communicating the pandemic and attempt to engage civil society to better consume information. The data collection comprises of interviews with the journalists, as well as the Twitter handling of these projects. This study sheds light to how independent voluntary initiatives can foster the correction of Covid-19 myths and misconceptions in their localities.

Introduction

Amidst challenges of the digital divide and information poverty in some African contexts, connected journalists act as gatekeepers and gatewatchers linking the virtual and the physical offline spaces of the orality and mythical traditions of their cultures. This paper explores the experience of independent journalists working as fact-checkers in two media projects on verification against false information on the new coronavirus pandemic in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and the Central African Republic (CAR).

In public health crises, misconceptions can have life-or-death effects and make societies and individuals vulnerable to false or misleading information. This qualitative paper asks: How do fact-checkers combat/halt Covid-19 myths and misconceptions in the DRC and the CAR? How do they engage in social media networks toward sense-giving and sharing corrective information? It discusses two cases of online media projects led by Congolese and Central African journalists that combine fact-checking skills when communicating the pandemic and attempt to engage civil society in better consume information. Born out of the Ebola outbreak in 2018 in the DRC, twenty independent journalists created the fact-checking online platform called ‘Congo Check’. In the CAR, nine journalists built the collaborative website ‘Talato’ for fact-checking on the coronavirus.

The aim is to explore how journalists engage in social networks bridging the online-offline spheres toward providing corrective information and how they act as sense-givers as a way of truth seeking and truth sharing. The interviews explored the journalists’ understanding of myth, misconceptions and rumor and whether they operationalized these terms. The data collection approached the journalists with interviews through instant messengers and a sample of Tweets posted by the projects. This study is three-fold: it bridges the journalists’ testimonials of the projects they are part of; how they connect with users online; and how they understand their role on the offline environment by detecting and filtering possible misconceptions and myths on Covid-19 that should be under scrutiny and verification. As argued, online social media should not be seen as disconnected from offline social spaces.

From Myth to Rumors and Gatekeeping – A Conceptual Discussion

This section approaches three segments: myths as a way of making sense of reality; gatekeeping and gatewatching roles; and the relation between misconceptions and truth seeking. The notion of gatekeeping might no longer be exclusively controlled by journalists being instead a shared collective task. In times of crisis, lack of information truthfulness can open the gates for uncertainties and disorientation. A better approach to social media may provide an opportunity to halt misconceptions serving as a corrective mechanism to false information.

The Mythical Domain for Sense-Making of Reality

Myths have functioned as ‘narrative theories’ of the world or as a ‘knowledge system’ for explaining human origins and actions. In popular use, myth can mean a false belief or an untrue story (Lule 2005) that express ideals, ideologies, values and beliefs as they explain origins and attempt to create order. A myth is always changing and being ‘transcribed’ on top of old versions. The memory of authorship is of little importance (Goody 2010, 41–46) and its content is seen as true. The orality of myths cannot be considered static as they are diverse and multiple (2010, 56–66). Theorized by Barthes (1972), myth is a type of speech that implies a system of communication, more specifically, a message. “It is not an object, a concept, or an idea; it is a mode of signification, a form” (1972, 107). As a type of speech, it is defined by its intention rather than by its literal sense (1972, 122). It is conveyed by a discourse and by the way in which it articulates the message. This type of discourse is not solely confined to the class in power, as it can be borrowed by classes outside power (Moriarty 1988, 197–98). It is everywhere and diffused through all social practices. Initially viewed as fundamentally political, Barthes presented an evolution of the concept of power embracing the ideological notion that was imbued in myth to support existing relations of power.

A mythic characterization of contemporary events work as an instinctive strategy for sense-making. In general terms, sense-making involves the process of assigning meaning to events “when individuals collectively come to an understanding about the meaning of an experience they have had” (Kramer 2016, 1). It is grounded in individual and social activities by applying stored knowledge, values and beliefs to new situations in an effort to understand them. Sense-making is associated with an interpretive perspective of communication since it focuses on how meaning is socially constructed. It does not entail that there be any objective truth to it (Kramer 2016, 1; Gioia and Kumar, 1991; Weick 1995). Information seeking and information use are key to sense-making during crises situations, as individuals attempt to bridge the cognitive gaps they face in everyday life as well as during non-routine times (Heverin and Zach 2012, 34; Dervin 1983; Stieglitz et al., 2017; Mirbabaie et al., 2020). Although the function of myth would include an ideal of sense-making of reality, it can also distort, deceive, pervert, misconstrue and misrepresent. Generally speaking, myth prefers to work with “poor, incomplete images” (Barthes 1972, 125). Societies do not hold a relationship with myths based on truth but based on use, “they depoliticize according to their needs” (1972, 144). As myth is a value, truth is not a guarantee of it. It is present as a “single snapshot of a complex process”, discussed (McLuhan, 1959, 339).

Both myth and news partake an emphasis on ‘real stories’ (Lule 2005, 105) sharing traditions of public storytelling. Media use narratives and mythical structures to add value to characters and events (Car 2008, 160) and to give meaning, as they largely influence people’s life and affect in the collective sense-making of experiences. There is, yet a debate on the difference between actual events and stories about those events. If media do not explain the context of a story, the news content can be confusing for the audience where political myths can gain a strong format (2008, 161). Hence, myths are more than fabrications of the truth, as they are one response to surmount our cognitive limits to understanding and making sense of the world. They do not always provide a satisfactory or acceptable response, but instead they aim that contradictions are ‘scalable’ (Mosco 2004, 28). Understanding myth offers a key tool to explore the construction of meaning in media narratives, as they may activate motifs embedded in oral culture and provide community members ‘guidance’ and information through a psychological identification process (Morales 2013, 33–34).

It is relevant to remark the notion of ‘sense-giving’ that is used to explain the mechanisms behind intentional information provision for collective meaning creation. This notion has also been used in the sphere of social media crisis communication. It is defined as an attempt to influence someone’s sense-making by having a preferred definition of reality in mind (Mirbabaie et al., 2020, 196–206). Sense-giving is concerned with the process of “attempting to influence the sense-making and meaning construction of others toward a preferred redefinition” of reality (Gioia and Kumar, 1991, 442). While sense-making deals with the justifications of a phenomenon; sense-giving is about influencing the perception of a situation looking at the diffusion of a justification (Giuliani 2016, 221; Mirbabaie et al., 2020, 198). The web would then become a ‘source of myth-making’ and could bring back its mythic form of consciousness where anything that appears is seen as “believable, whether or not it is real or true” (Danesi 2018, 64).

Gatekeeping in the Online Sphere

This segment considers the shifting concept of gatekeeping and the journalists roles amid the transition to the virtual sphere. Gatekeeping no longer exclusively refers to “how events pass through gates and end up as news dissemination” (Tandoc and Vos 2016, 13; Vos and Heinderyckx 2015). In an overloaded online information environment, the distribution has become important and journalists have embraced social media and integrated them in their news work (Tandoc and Vos 2016, 2–5). Gatekeeping is a popular metaphor in journalism studies and originally a theory of news selection (Vos and Heinderyckx 2015; Tandoc and Vos 2016; Tandoc 2018). It has been conceptualized as a journalistic role, a model that describes the flow of news, and a theory that explains the news selection referring to the process of “how bits of information pass through a series of gates and end up in the news” (Tandoc 2018, 235). The so-called ‘gatekeepers’ can close or open the gates, “constraining or facilitating” (2018, 239) the flow of information.

Gatekeeping has traditionally prioritized editorial autonomy (Shoemaker and Vos 2009; Tandoc and Vos 2016) and that the amount of autonomy a journalist has may as well influence gatekeeping. News organizations have had to adjust their operations due to the increased relevance of the audience shaped by social media. Initially designed as networking platforms, social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter have become sources of news for a growing number of people and the journalists’ relationship with their sources and audiences has changed (Tandoc 2018; Tandoc and Vos 2016, 236).

Audiences can influence the dissemination of news articles that flow from the journalist channel by what they share on their social media accounts. Journalists can amplify and expand what audiences are spreading on social networks by reporting about it through their own channels (Tandoc 2018). The expanded role of the user was facilitated by technology repositioning the gatekeeping role (Singer, 2014, 55–56). Users now have the capability to make what would have been previously limited to editorial judgments about what is worthy or not, or what others should read or ignore. Users have the power to make news more (in) visible to others. An interactive online environment enables a two-step gatekeeping process where users are active recipients of the news (Singer 2011; Singer, 2014, 56–58). News consumption is a “socially-engaging and socially-driven activity” with the public becoming part of the news process (Purcell et al., 2010).

The changing role of journalism from solely controlling the construction of social reality to curating it by re-publishing content through journalistic platforms after it is already visible on the web turn journalists into ‘gatewatchers’ (Bruns, 2005; Wallace, 2018, p. 277). Gatewatching more often results in publicizing existing content. Notably, most user-generated news items do not influence the public agenda by themselves, the publication can remain irrelevant unless it is republished by other individuals. These decentralized gatekeeping mechanisms take different forms, Facebook and Twitter as the most popular (Wallace 2018, 283–84).

Misconceptions and Truth Seeking

During a public health crisis, people seek information to help understand and make sense of risks as well as to make decisions on how to respond (Starbird et al., 2020). This process of collective sense-making can be exploited by those who wish to mislead and delude by seeding an ‘information disorder’, a term coined to describe toxic informational environments (Wardle and Derakhshan 2017). The field of misinformation studies draws from different traditions having rumors as an influential one. Rumor is a byproduct of the collective sense-making process referring to “information that is unverified at the time it is being discussed” (Starbird et al., 2020, paragraph 7). Periods of crisis comprise events with high levels of uncertainty and anxiety, and official sources may offer limited or untimely information. Thus, rumoring can become a collective problem-solving strategy as a way to improvise news so as to make sense of the evolving situation and cope with uncertainties (Shibutani 1966; Starbird et al., 2020).

“if such information is not forth-coming from formal news channels, demand for news remains. Men still have to meet the situation; unless they can put together some kind of definition, they cannot act. In such contexts they are likely to pool their intellectual resources and to improvise an interpretation” (Shibutani 1966, 174).

Rumors circulate “like the air we breathe” (Rosnow 1988, 12). They are public and informal social communications that reflect private hypotheses about how the world works. It is a hypotheses of unconfirmed propositions (1988, 13–14). They are disseminated without official verification. As myth, it is an informal social communications with a mode of transmission-mostly by word-of-mouth. Its aim is to present surprising news and not to “satisfy” (Knapp 1944, 22–23). Factors for rumor generation and transmission are anxiety, general uncertainty, credulity, and topical importance (Rosnow 1988, 20). A rumor transmits to others the claim it embodies as if it were true, even in acknowledging a lack of verification (Pendleton 1998, 71).

There are three types of information disorder: 1) dis-information, information that is false and deliberately created to harm a person, social group, organization or country; 2) mis-information, information that is false and mistaken but not created with the intention of causing harm; and 3) mal-information, that is based on reality, but used to inflict harm on a person, organization or country (Wardle and Derakhshan 2017, 20; Fetzer 2004, 231). Whether it results from an honest mistake, negligence, unconscious bias, or (as in the case of disinformation) intentional deception, inaccurate information can mislead people. Disinformation can harm people indirectly by eroding trust and thereby inhibiting our ability to effectively share information with one another (Fallis 2015, 401–2).

Contexts of crisis open the door for uncertainties, disorientation and challenges in verifying information. This may often result in limited ability to clarify facts or check sources (Starbird et al., 2020, paragraph 11). Misinformation can appear with different forms, such as publicizing false medical advice, spread conspiracy theories about underlying causes of the crisis, or other intentional disinformation campaigns for political gain (paragraph 26). Conspiracy theories can spread as fast as virus and in the context of the new coronavirus pandemic, a recent example in the media claimed that the symptoms associated with Covid-19 were caused by 5G technologies and that powerful people were conspiring to hide this truth (Andrews 2020; Downing et al., 2020; Goodman and Carmichael 2020). Such claim did not stop rumors going global “leading to protests even in countries where the technology doesn’t yet exist” (Goodman and Carmichael 2020).

A conspiracy theory is defined as a proposed plot by powerful people or organizations working together in secret to accomplish some dire goal. Conspiracy theories are not by definition false; but when wrong, they are resistant to falsification, with new layers of conspiracy being added to rationalize each new piece of disconfirming evidence (Wood et al., 2012, 767). Several internet platforms became ground for the growth of conspiracy theories. Without the barrier of traditional media gatekeepers, users can post their own conspiracy content. They generally express anxieties about losing control in a particular setting. Some theories have an ideological focus, others express a distrust of government or official stories of the media. The overarching themes of these theories remain expressing anxieties about loss of control within a religious, political, or social order (Lewis and Marwick 2017, 18).

A lack of information truthfulness is a challenge to communications (van der Meer and Jin 2020) rendering it difficult to determine what is reliable, which one to trust, and in the meantime, emotions such as fear, fright, anxiety, sadness and uncertainty can mobilize people and shape their actions (Starbird et al., 2020; van der Meer and Jin 2020). During the Zika epidemic an ‘emotional resonance’ was aggravated by misinformation about the crisis (Bode and Emily, 2018). The widespread misinformation concerning the Ebola epidemic in West Africa was reported to circulate on popular media platforms including social media (Tan et al., 2015, 675). Larson (2018) warned that the biggest pandemic risk would be viral misinformation and that the next major outbreak would be exacerbated by efforts to sow distrust in the vaccines developed for the pandemic. When public health authorities are not seen as credible sources, population tend to turn to informal ways to find information on health (Jang and Young, 2019). This study showed that less credible information “led to more frequent use of online news, interpersonal networks, and social media” (2019, 991) in the context of the 2015 Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) outbreak in South Korea.

Given the daily presence in users’ lives, social media may also offer an opportunity to combat misinformation. van der Meer and Jin (2020) agree that if corrective information is present rather than absent in the communication channels, incorrect beliefs are “debunked and the exposure to factual elaboration, compared to simple rebuttal, stimulates intentions to take protective actions” (2020, 560). Although the simple presence of corrective information does not necessarily move individuals to change their behavior, correcting information might increase awareness among audiences and give a sense of the seriousness of a crisis situation and alter their perception and state of emotions. In times of public health crisis, corrective information may counter misperception and improve belief accuracy after individuals’ exposure to misinformation (2020, 568).

The Use of Social Media to Disseminate False Information in Africa

The phenomenon of false information has been largely studied in the United States and Europe with relatively low attention to the context of African countries (Madrid-Morales and Wasserman 2018). Disinformation has taken the shape of extreme speech with violence incitement with messages incorporating racism and xenophobia. These messages have often been disseminated on mobile phones through platforms of instant messages (e.g., WhatsApp). There is a relationship between perceived exposure to misinformation and fake news and declining overall media trust. When asked whether people had shared what they knew was made up, one-in-five South Africans and one-in-four Kenyans and Nigerians said ‘yes’ in a survey (Wasserman and Madrid-Morales 2019). The public is seen as bearing the largest responsibility in stopping the spread of misinformation. More than two-thirds of respondents said that the public have a deal of responsibility, followed by social media companies and the government (Madrid-Morales and Wasserman 2018; Wasserman and Madrid-Morales 2019).

Powerful countries have been accused of fostering information disorder. Facebook announced December 2020 that it removed almost 500 accounts and pages tied to French and Russian disinformation campaigns that largely focused on the Central African Republic elections, scheduled for December 27, 2020, that also targeted users in 13 other African countries including Algeria, Cameroon, Libya and Sudan (Matiashe 2020; Stubbs 2020). The Russian disinformation campaign in African countries had been denounced a year earlier (Davey and Frenkel 2019; Fidler 2019) posing a test for the internet policy in Africa.

The information ecosystem in the Democratic Republic of Congo is seen as fragmented and fragile with a great number of media outlets, but with a low level of professionalism and a high vulnerability to partisan capture. This fragility is replicated in the online space. The Congolese population rely heavily on informal sources of information such as interpersonal communication with family and friends. The scarcity of reliable information open avenues for rumors and misinformation (Demos, 2019). Belief in misinformation was widespread, showed a survey in September 2018 in the areas of Beni and Butembo in the province of North Kivu in eastern DRC with respondents believing that the Ebola outbreak was not real (Vinck et al., 2019). Low institutional trust and belief in misinformation were associated with a decreased likelihood of adopting preventive behaviors. A higher proportion of respondents believed that the Ebola outbreak was fabricated for financial gains or to destabilize the region. Community radio stations as well as family and friends were the main source of Ebola information. Besides, national radio stations, religious leaders and health professionals were important channels of receiving information. In contrast, fewer respondents had heard about Ebola from local authorities or national government (Vinck et al., 2019, 533).

Information about Covid-19 has been shared and viewed over 270 billion times online and mentioned almost 40 million times on Twitter and web-based news sites in the 47 countries of the African region between February and November 2020, according to the UN Global Pulse, the United Nations’ Secretary-General’s initiative on big data and artificial intelligence (WHO 2020). A large proportion of this information is inaccurate and misleading and continues to be shared by social media users intentionally or unknowingly every day. The Covid-19 infodemic is amplified online through social media but health misinformation is also circulating offline, informed the WHO. Measuring precisely how much of what is circulating is misinformation is difficult, but fact-checking organizations in Africa say they debunked more than 1,000 of such misleading reports since the beginning of the pandemic. Some of the widely shared misinformation include conspiracies around unproven treatments, false cures and anti-vaccine messages (WHO 2020).

The year of 2020 saw the announcement of different initiatives to halt the spread of mis-/disinformation. The World Health Organization launched December 2020 a new alliance named ‘Africa Infodemic Response Alliance’ (AIRA), to coordinate actions and pool resources in combating misinformation around Covid-19 pandemic and other health emergencies in Africa. AIRA supports individual African countries in developing tailored infodemic management strategies. In a similar line, September 2020 UNESCO and six media development and advocacy organizations articulated the ‘Covid -19 Response in Africa’, a 18-months project to foster reliable and critical information about the coronavirus. In rural areas there is little information on Covid-19 and many people are not aware of the gravity of the situation. In some countries there is a lack of government transparency on the infections and deaths (Free Press Unlimited 2020). Both CAR and DRC are among the countries contemplated in the AIRA and the consortium project of UNESCO.

In the Central African Republic

The first imported Covid-19 case (from Italy) dated from March 14, 2020. By 6 July, the country had four thousand confirmed cases. Since the last crises, the country experienced a rise in rumors and misinformation, reinforced by a high rate of illiteracy–nearly six out of 10 Central African 10-year-olds cannot read or write (Mouguia 2020). Some Central Africans are said to be reluctant to respect the sanitary measures taken by the government to slow down the spread of the pandemic. Some described Covid-19 as a “divine punishment against sinners” (Mouguia 2020, paragraph 6).

Despite the claims to respect the instructions via radio and television announcements, and from the mobile telephone companies (SMS and audio messages), residents of Bangui appeared insensitive: “gatherings are common, e.g., for football matches in quartiers; funerals (also prohibited); handshakes are rife, and drinking places that officially remain closed operate behind closed doors” (Mouguia 2020, paragraph 6). In the surroundings of the town of Bossangoa (northwest of CAR), people refused to take part in awareness-raizing sessions organized by NGOs because they rejected the imposition of the distancing measures. In other places like Batangafo where insecurity situation increased, people denied the very existence of the pandemic. The churches and schools were closed, but mosques and Koranic schools remained functional. Even in the capital Bangui, in the Muslim neighborhood of PK5, the mosques were opened during Ramadan (Mouguia 2020, paragraph 8).

In the Democratic Republic of Congo

The challenge is convincing people that coronavirus exists. Fake news polluted Congolese social media platforms including Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp, and Instagram with conspiracy theories denying the existence of the pandemic (Cirhigiri 2020). Government distrust, lockdown, and increased social media access hasten the spread of mis- and disinformation in the country. With more than 11 thousand registered cases in early November 2020, the DRC is the Central African country most affected by the Covid-19 pandemic, reported an American-based media development organization. “The level of trust of the citizens toward public institutions is extremely low” (Dende 2020). Likewise, in the first months of the 2018 Ebola outbreak in the provinces of North Kivu and Ituri led to a denial of the existence of the virus and to the proliferation of a considerable number of rumors and fake news, such as a disbelief that the virus existed, or that traditional leaders would ensure protection through witchcraft (Dende 2020, paragraph 3). The pandemic disseminated quickly when the Congolese government announced the first deaths of Covid-19 in March 2020. When people in popular areas of the capital Kinshasa heard that chloroquinine could be used as treatment, some people associated with a quinine-based drug Kongo Bololo or the traditional remedy muvuke made with aromatic plants of eucalyptus and lemon.

Community radio journalists spotted local WhatsApp groups as the origin of Covid-19 rumors and saw how youth and community leaders spread rumors by word-of-mouth (Dende 2020, paragraph 6). A new word borrowed from French, coroniser, was invented meaning that “fake cases put in quarantine to help the state fabricate statistics to access money” (paragraph 4). Local press reported lack of transparency in fund management that fostered narratives that authorities were profiting through the virus (Okapi, 2020). Some factors could be responsible for the spread of fake news in the DRC such as mistrust toward government officials, contradictions concerning the nationality of the first case that was initially identified as a Belgian then as a Congolese living in France, reported the local press (Cikuru, 2020a; Cikuru, 2020b). The lack of digital literacy plays a role in the fake news dissemination in the country where less than 20% have access to internet (Aganze and Kusinza 2020, 33). One of the main worries of a Doctors Without Borders’ officer in the province of South Kivu was misinformation or lack of reliable information, as he reported:

“Far too often, people lack reliable sources of information, such as recognized medical experts who are working on this new coronavirus or the Ministry of Health. Instead, they get their news from unchecked and often untrustworthy sources through social media, especially WhatsApp. These sources, in most cases, spread rumors rather than truth. Without clear official communications, it’s hard for everyone, even me, to discern the truth” (MSF 2020, paragraphs 5-6).

Challenges of Connectivity and Case Studies

This segment discusses the persistent digital divide in Central Africa despite the increasing rates of online connectivity in the region and the idea that a culture-centered approach could be harnessed when connected citizens surf on internet and engage in social media. It also introduces the two media projects in the DRC and CAR that will serve as case studies.

Considering the Digital Divide

Digital divide is used to describe inequalities brought about by emerging technologies and has had a critical impact on the ways in which information across Africa is developed, shared, and perceived (Ragnedda and Mutsvairo 2019, 13). Mobile telephony is growing ‘extortionately’ in Africa and the rise of smartphones allowed some citizens easy access to social networks. Yet several groups are left out of the digital participation since online activity is limited to those who can read and understand the colonial languages and afford the cost of connectivity.

“The digital divide–the unavoidable void between those with access to information and communication technologies (ICTs) and those without ‒ remains a major problem in Africa. Mobile phones are too expensive for many and accessing mobile internet is even worse” (Ragnedda and Mutsvairo 2019, 14).

Overall, internet users in emerging and developing countries are more likely to use social media compared with those in the developed world (Poushter 2016). In Africa, a continent with an estimated 1.3 billion people, internet penetration in the population is 39% and around 200 million people use social media (Internetworldstats 2020) – among internet users, 76% rely on social networks (West 2017). It is important to remark the existence of gender gaps on many aspects of technology in African nations concerning smartphone ownership where men are more likely to own a smartphone (Poushter 2016). Additionally, urban areas in the continent have a greater access to internet than rural sites (Essoungou 2019). One in five adults (20%) have access to both a smartphone and a computer, while 43% only have access to a basic cell phone, reported a policy paper from Afrobarometer released in June 2020 (Krönke 2020).

Digital media remain beyond many Africans’ reach, wrote Conroy-Krutz (2020). There is a pronounced digital divide – younger, better-educated, wealthier, male and urban-dwelling Africans are much more likely to access the online world. The internet and social media have been a “double-edged sword” (2020, paragraph 1) when it comes to fighting Covid-19 in Africa. On the one hand, governments and health authorities have used Twitter, WhatsApp, Facebook and other social media to reach large number of people with information on how to stay healthy and limit the virus’s spread; on the other hand, these technologies have facilitated the spread of misinformation (2020, paragraph 2).

Africa’s media landscape is changing swiftly. Reliance on digital sources for news has doubled in five years, with more than one-third of respondents across 18 countries reporting that they turn to the internet or social media at least a few times a week for news. As digital media access continues to rise across demographic groups and in most countries, the possibilities of creating better-educated, more-active populations appear to be exciting as majority of Africans see digital media as having mostly positive effects on society. There is, nonetheless, suspicion as new media is also seen as facilitating the spread of false information and hate speech (Conroy-Krutz and Joseph, 2020, 1).

Particularly in the Sahelian region (that includes the CAR, Chad, Mali, Niger, and Guinea), no more than 64% of people have a working mobile phone, compared with 71% in the rest of sub-Saharan Africa, and 95% worldwide, informed a report from the World Bank (Lopez-Calix and Rogy 2017, 10; Ragnedda and Mutsvairo 2019). As Frère (2012) discussed, connectivity in the continent remains low, but change is afoot led by the growth of mobile internet access. On a report about news media in the DRC, Rwanda, and Burundi, Frère described that most media outlets have an online presence and that interactivity granted voice to rising numbers of users. The development of the internet and mobile telephony brought significant changes in the information sector in a “region where the lack of freely and widely circulating information has probably fueled mass violence” (2012, 47). The improvements in media operations and journalistic practices in Central Africa are intimately linked to the growing use of ICTs.

According to the DataReportal (Kemp, 2020) by January 2020, there were 16 million internet users in the DRC, having increased by 122% (nine million users) from 2019. The internet penetration in the country was 19% and there were three million users of social networks in the country corresponding to 3.5% of the social media penetration by early 2020 (Kemp, 2020; Internetworldstats 2020). Regarding mobile connections, there were 35 million mobile connections in January 2020 representing 40% of the total population. As for the CAR, by January 2020, there were 655 thousand internet users, having increased by 20% from 2019 (Kemp, 2020). The internet penetration in the country is 14% and there were 120 thousand social media users in the country standing around 2.5% of the social media penetration by early 2020 (Kemp, 2020; Internetworldstats 2020). There were 2,3 million mobile connections by January 2020 (48% of the total population). These figures express the potential in both DRC and CAR of increasing internet users through mobiles, despite the infrastructure challenges.

The communications infrastructure and capacity have been severely damaged after the conflict that erupted in CAR with the seizure of the capital Bangui by an alliance of northern and Muslim rebel groups, Séléka, in March 2013, and further in December 2013 the attack of a Christian militia, anti-Balaka. These events turned the violence into a sectarian conflict pushing the international community to react with a UN peace operation. A national media and information survey in 2015 conducted by Internews, an American based media development organization, measured the access to media, listening habits, and information needs of the Central African population in 14 of the 16 préfectures (provinces of the country). Radio was evidenced to be the most popular media in the capital and community radios in semi-urban areas. Friends, neighbors and family appeared as the second source of information in CAR (Hasan and Benard-Dende 2015, 27). Socio-economic inequalities had a direct impact on access to information (media, mobile phones and internet). The inequality in the access to mobile was significant – 51% of women did not use mobile phone and the main reason was related to poverty. Access to information on internet was poor and unequal: 96% of female declared they never used internet against 84.6% of male respondents (Hasan and Benard-Dende 2015, 18–19).

A decade ago, there were doubts on the possibility of Africa’s success in the global social media sphere because of the widespread poverty and the unequal distribution of access to ICT tools (Ephraim 2013, 276). The idea to incorporate a component of information ethics to make users of social networks responsible by granting them a conscience while engaging on social media forums as a culture-centered approach was put forward (Ephraim 2013). Ethical standards involve “virtues of honesty, respect for human dignity, compassion, loyalty; the right to life, the right to freedom from injury, and the right to privacy” (2013, 281). In a proposed culture-centered approach, internet and social networks are platforms for communication and information exchange and “not tools for attacking or taking advantage of people irrespective of age, sex, race, social status or sexual orientation” (2013, 281). Online users are humans and their rights and dignities should be respected. Such approach to social media could enhance and foster the sharing of truthful information and halt the spread of myths and misconceptions.

Verifying With 'Congo Check' and 'Talato'

Born out of the Ebola outbreak in 2018 in the DRC, twenty independent journalists created the fact-checking online platform ‘Congo Check’, the first information media specialized in verification in the country1. It is a signatory of the code of principles of the International Factchecking Network and has the mission to “fight against false information that has become commonplace on the internet in the DRC, most of which is disseminated by malicious individuals on social networks and sometimes by websites” (Congo Check, 2020). A special section on Covid-19 was launched in March 2020 with a work mostly done voluntarily. Congo Check is based in Goma, capital of North Kivu in eastern DRC, with 13 journalists working in the headquarters and across the country around 20 journalists are spread as correspondents. Among its activities, they produce “verification articles on facts relayed either by the media, executives and other public figures as well as ordinary internet users” (Congo Check, 2020). The project additionally assists local newsrooms, other independent journalists and users with free training sessions on fact-checking strategies. Within the ground rules of the project, the journalists do not express their personal opinion in their articles and keep their conduct to strictly examining the facts. In November 2020, the Congolese fact-checking media project received the Francophone media innovation award from the International Organization of the Francophonie, RFI (Radio France International) and Reporters Without Borders (RFI 2020).

In the neighboring country CAR, nine independent journalists built in March 2020 the collaborative website ‘Talato’ for fact-checking on the coronavirus information in the country. Talato is a project of the Association of Central African Bloggers (ABCA). This association was launched in 2017 and currently gathers around 80 members among journalists, bloggers and artists working in the freedom of information in the online environment. Talato is a “digital, independent and participatory news media”2. The platform is intended to foster “information governance on the Central African Republic in the context of the coronavirus epidemic” (Talato 2020) by offering news articles, fact-checking and statistical data of the disease.

Internet-Based Data Collection As a Method

Due to the global spread of the Covid-19 pandemic, the geographical constraints of displacement and the need to keep social distancing, the use of social networks for research purposes has quickly developed. This paper approached the journalists through a platform of instant messenger and analyzed a sample of Tweets posted by Congo Check and Talato. We now discuss the challenges of researching media networks, particularly microblogging and the use of remote interviews as a way of overcoming distances.

Interviews With Instant Messenger

In unstable environments and conflict-prone settings, logistical considerations emerge when planning research (Chiumento et al., 2018) including restricted access added to the limitation of traveling and social distancing generated by the Covid-19 pandemic. One way to overcome access difficulties was to use internet communication technologies through online interviewing. The decision to incorporate online synchronous interviews was necessary due to security and sanitary measures preventing travel to the research sites to conduct in-person interviews. Instant messenger interviewing was then the method chosen for approaching Congo Check and Talato journalists between 30 July and August 4, 2020. The qualitative interviews asked questions that encouraged the journalists to share their experiences in their own words. This type of platform to conduct interviews offered advantages for hard-to-reach participants for data capture as it does not require the participants to be in the same physical location (Lannutti 2017, 237–40).

The study initially used text-based communication through typed words and when the journalist agreed to participate in the research a call was scheduled through WhatsApp. Some technical challenges included sound quality issues, a time-lag in the audio feed in which sound was relayed slower than real time and potential technological failure (Chiumento et al., 2018, 3). Participants were contacted through a snowball sampling and informed their consentment during the call. They agreed to answer to questions and were aware and in accordance with the conversation being recorded. The interviews were recorded through the use of a (offline) device recorder to protect the safety of the data. When (during the interviews) the internet cut the conversation continued through exchange of voice messages nearly in real time. The level of immediacy and timing of response was near-synchronous as most of the e-interviews proceeded as planned. The semi-structured interviews had the same type of open-ended questions asked in a similar sequence, but with varied follow-up questions (Salmons 2012, 20).

In highly sensitive contexts, guaranteeing complete anonymity to participants can be an “unachievable goal” in qualitative research argued scholars (Hoonaard, 2003, 141; Saunders et al., 2015). The priority was to maximize the protection of participants’ identities and safeguard the value and integrity of the data. Privacy was guaranteed by not sharing personal information of the participants. Due to the online format, though, the researcher is unable to control the participant’s environment or the location from which participants were placed (Chiumento et al., 2018, 4). Yet, an attempt was established for a safe online environment that could encourage the participant disclosure in interviews. Interviews through WhatsApp offer a low risk of a breach of confidentiality since the data is encrypted (Security Page, 2020). Online interviewing is not a flawless technique to research data and to protect participants, it is nevertheless a valid and effective means of research when all others fail to grant at least some degree of protection (Chiumento et al., 2018).

Twitter As a Source of Data

As a relational networked cultural environment, Twitter is well-suited to research into situated knowledges (Stewart 2016) and myths once this platform is based around interactions, its lens is multiple and relatively non-hierarchical. Its structure is based on a ‘logic of virality’ (2016, 4) being a valuable platform for research into decentralized non-gatekept professional cultures. Twitter was created in 2006 and is a popular microblogging tool with 330 million monthly users and 145 million daily active users who post around 500 million tweets per day. Each user surfs on Twitter less than 4 min (Lin 2020) and two thirds say they use this network to get news (Omnicore 2020). While Twitter is not as widely used as Facebook, it has had a “transformative effect on how information and news diffuse throughout society” (McCay-Peet and Quan-Haase 2016, 6). By allowing only brief messages – the maximum length of a ‘tweet’ is 280 characters – interactivity occurs with commands of ‘replying to’ or mentioning others with tagging so that people can follow a public conversation with hashtags and ‘retweet’ them. The role of information sharing through social media tools for collective sense-making during crises is yet to be enhanced in research, discussed Heveri and Zach (2012). Examining social media gives the general impression that it is a universe in itself in isolation (McCay-Peet and Quan-Haase 2016, 10). Such perspective is short sighted, disregarding how social network and the phenomena that emerge within are interlaced to other spheres of life.

Facebook is the most widely used social network in the DRC, followed by Twitter; and WhatsApp is the widely used online messaging service (Demos, 2019, 4). The most shared sites and opinion on WhatsApp are local in scope than the ones shared via Twitter. WhatsApp is rather used by the community at the local level for information about daily processes. A significant proportion of the Twitter posts mentioned rumors, conspiracy theories or misinformation (Demos, 2019). In the eastern DRC, the most influential Twitter accounts in public conversations during the 2018 Ebola epidemic and the Congolese electoral processes in 2018 were accounts of politicians (also opposition leaders), news websites and individual journalists and institutional branches (Demos, 2019). In the context of Ebola, the most reported accounts were those of the Ministry of Health, Congolese journalists, youth political movement, news sites, politicians and international NGOs. “Even in a country where Twitter is rarely used, it can still allow ordinary citizens to make their voices heard and provide them with significant public exposure” (Demos, 2019, 33).

Scholarly research still lacks in assessing social media usage of journalists and citizens in CAR. Press reports (Smith, 2016) suggested that social network was central in pushing out former President François Bozize in 2013. Images circulated on Facebook were partly the reason why the Séléka rebels’ support increased in the country, they also contributed to former president Bozize’s fall due to lack of popular support. When the rebels seized the capital Bangui, social media activists used the same method against the Séléka. This time around, journalists and politicians used social media to expose the new government’s abuses (Smith, 2016, paragraph 7). When the country held its first presidential elections after the conflict (2015), watchdogs used social media to keep the outcome honest. Before the electoral commission could declare a winner, local electoral observers used social media to announce the president-elect drawing from firsthand accounts from individual Central Africans observing the votes being counted (Smith, 2016, paragraph 11).

Findings and Discussion

The data comprised interviews conducted with eight journalists between 30 July and August 4, 2020 and Twitter posts of Congo Check and Talato (5 May - 21 October 2020). The findings are presented and discussed in this section.

'Congo Check' and 'Talato' Journalists

The interviews were examined using thematic analysis that explored the pattern of meaning across texts, particularly journalists’ understanding of myth, misconceptions and rumor and whether they distinguished the use of such concepts. Thematic analysis is the process of identifying, describing, analyzing, and reporting themes. It is a theoretically-flexible approach for qualitative analysis that not simply summarizes the content, but also organizes and describes the empirical material in richer detail (Boyatzis 1998; Braun and Clarke 2006; Clarke and Braun 2017; Clarke and Braun, 2018; Evans and Lewis 2018). It was used to interrogate patterns with personal and social meaning (Clarke and Braun 2017, 297–98). The analysis was done in seven thematic blocks: 1) the journalists’ professional work and how they described their role and the fact-checking projects; 2) fake news profusion; 3) gatekeeping online-offline; 4) Covid-19 misconceptions; 5) emitters of false information; 6) audience; and 7) social media as a tool for awareness raising.

Professional Work

Both Congolese and Central African journalists affirmed the notion of collectivity in their work. They expressed the idea that they act as a ‘radar’ or a sensor detecting myths that could disinform regarding the spread of the virus. Being a ‘Covid-19 radar’ for myths is seen in a broad sense – informing the correct numbers of cases and healed patients as for Talato, as well as facts involving the management of the crisis regarding public measures for Congo Check. When engaging in social networks, the reporters embody the role of gatewatchers curating the information and operating as sense-givers for truth sharing. In Sango, language spoken in CAR, ‘talato’ means radar. A radar is a device or a system of a “synchronized radio transmitter and receiver that emits radio waves and processes their reflections for display and is used especially for locating objects or surface features”3. On a figurative way, this word is used as being “aware of something”4.

Their professional work is done with their own means in a voluntary way with “enormous difficulties”, said G. On their account, their role consists of providing the ‘good information’ to fill the gap of communication. Both projects attempt to influence the construction of meanings and aspire to be recognized as a reference in their countries for other media and for the population. According to them, fact-checking is a job on its own. When the first case of Covid-19 was declared in the CAR (March 14, 2020), Talato journalists were concerned: “Not only did people not believe, but at one point there was a news campaign circulating about this disease”, said G who described the collective experience against ‘intox’ referring to intoxication of information:

“Talato deals exclusively with the question of Covid-19, we do verification work, when there are cases of disinformation, ‘intox’, we write explanatory verification articles that can establish the truth. We also do statistics, how many cases, how many people tested positive, how many deaths, how many cured (…) Are the measures being taken? Are the funds being managed by the partners?” (G-Talato, originally in French)

The coronavirus is a ‘sensitive question’ and that sometimes sources entitled to offer the correct information are afraid of speaking. Journalists are often targeted and harassed by authorities when they publish information considered as a critique. R described their job as “complicated” in CAR and criticized the leaders and institutions that lack better communication with the society. F explained the project strives to publish twice a week:

“There are voluntary contributing editors and two interns. We have no remuneration, we have no money. We try to work on a voluntary basis. We have two WhatsApp groups (…), the first group of the Talato editorial staff which concerns the proposal of the topic, the discussion on the content, the correction of the articles and the validation for the publication. And the second group is open, it’s a communication group that we’ve integrated a lot of people, in this group we share the articles.” (F-Talato, originally in French)

When Talato was created “it was not for nothing”, there was a concern among the group of journalists on how to raise awareness and give the truthful information about the disease, explained SL. In order to do so, the journalists reach out to different organizations and not only the government:

“We get our information from authorized government sources, international organizations like the WHO [World Health Organization], MSF [Doctors without Borders], we work with all these people so that they can give us real information about this pandemic, to make the community understand that this pandemic really exists and it’s devastating other countries, even if here they say they don’t see the dead, they don’t see the sick people”. (SL-Talato, originally in French)

False information is everywhere in the DRC, according to the journalists. People use social network to spread their ideas and myths in an attempt to “find a place in society”, said D. In the DRC, “the false information may kill” and “someone who is mal informed may die of its own ignorance”, complemented D stressing that the group of Congolese journalists could not keep the “arms crossed without doing nothing”. Their testimonials suggest that the fact checkers constantly endeavor to link the physical spaces of life to the virtual world. Within their accounts, online media should not be seen as disconnected from offline social spaces. D claimed that the good information would be able to destroy the bad. M said to feel motivated to join the initiative by witnessing the damage done with the spread of myths in relation to Ebola. According to the reporter, verifying and halting misinformation is “patriotic” despite a voluntarily job. For RS, in order to combat the rumors and myths, it is necessary to “identify them in their roots”. While rumors act as a kind of improvised news, myths try to generate explanations for a given event or circumstance and in both cases the reporters pointed to the need of being vigilant and diagnose these messages from the moment they flourish. Their voices granted similar understanding of myths and misconceptions embracing rumors, disinformation or conspiracy theories all in one general category of ‘intox’. Their perception overlapped using different terminologies as synonyms.

Fake News Profusion

False information has the ability to spread faster and to gain more space than the truthful information. The work of halting misconceptions is done as a professional commitment to their society, accounted the reporters. With the eagerness and keenness to generate meaning to certain processes and in order to understand events and facts from reality, myths take a single and simplistic view of a complex process that may create distorted representations. The risk is that its literal meaning can be interpreted as true, especially in situations of lack or mismatched information where the population yearns for accurate news to meet its information needs.

The lack of media literacy of citizens is a component that fuels the dissemination of misconceptions, the reporters informed. F showed concern that the efforts of halting myths and misconceptions might not reach everyone and agreed that false information proliferates on a daily basis.

“Despite everything, we are not going to convince everyone, there are people who remain skeptical about the existence of the disease in Africa (…) There are fake news practically every day. (…) We are in a political context, which is the contradiction, the political struggle, also in the field of social networks. (…) I believe that there are people who are paid to convey this false information on the net.” (F-Talato, originally in French)

Everyone may become a source of false information – being them myths, rumors, conspiracy theories or disinformation –, said G who sees the effort of halting false information a priority particularly in a conflicting context as CAR. The fight against misinformation is seen as an important element for building peace: “If I want my country to find lasting peace today, we must fight against disinformation. That is why I said to myself, the little that I know how to do, I must put at the service of the public”, stressed G. R described the gravity of the spread of myths:

“In our country, fake news can lead to the assassination of a person. Just say that ‘such a woman is a witch’, I swear that the whole neighborhood will come out for that person.” (R-Talato, originally in French)

D believes that one aspect that leads to the profusion of misconceptions in the DRC is the politicians by attempting to “favor their image and downplay their adversaries”. Generating a rumor is an act of egoism and selfishness:

“False information circulates too much in the country for selfish interests of each and every case, be it politics, civil society (…). There is always someone every day who want to attract the sympathy of this or that other person through social networks (…) to be heard, to be talked about.” (D-Congo Check, originally in French)

Misconceptions, being them mis-/disinformation, rumors, and mythical explanations that are not true reached a dangerous rhizomatic dimension. They are easily graspable gaining space a lot faster than the truthful information. Despite done voluntarily, M feels committed: “We really need to get into this false news environment to destroy it and bring the good news”. Myths seek that contradictions expand in scale and a lack of information truthfulness becomes a challenge to communications. RS remembered that misconceptions about Ebola made the epidemic even more perilous and deadly, something similar that happened again during the Covid-19 pandemic:

“It does not allow a good fight against the pandemic. The virus circulates because the population is pessimistic, it is opposed to the existence of the pandemic, it is difficult to be able to treat people who are victims of infox, that’s how Congo Check gives itself the duty to be able to fight against this kind of thing. (…) We are looking for all the false information, and we verify to give the right information to the community.” (RS-Congo Check, originally in French)

Gatekeeping/Gatewatching Online-Offline

Both Congolese and Central African journalists see their role with responsibility in trying to filter myths and rumors that have been spread on the online and offline world, on the streets, on the markets, in their private groups. They acknowledged the difficulty of being a news curator and maintaining the role of detecting prejudicious misconceptions. SL explicitly said that “we also work on word-to-mouth subjects”. G stressed that many people are used to speak without having any knowledge from where or from whom the person received the information. F agreed that a rumor is “very difficult to combat”. The fact that not everyone has social media is somewhat difficult to reach those who are excluded from the digital environment, but who can still be affected by misconceptions in the offline space.

“There is a majority of people who continue to believe in spite of the denial and continue to spread false information by word-of-mouth. (…) what is being said in bars, in neighborhoods, for us it is difficult to deny (…), if we ourselves are in an environment where people say ‘this or that’ on a discussion, we can show that it is not true. (…) people are not well educated to question the information they receive.” (F-Talato, originally in French)

RS believes Congo Check’s work has started to be known by many and that other media relay information verified by the group.

“At least a lot of people know that Congo Check exists and that it does fact-checking in the DRC where false information is on the front page” (RS-Congo Check, originally in French)

They stressed that they receive a growing demand for verification by the society. Individuals reach out to the Congolese journalists to request verification of various types of information. They act within the idea of the gatekeeping process, i.e., an attempt to separate the trust- and newsworthy from the unworthy, but they acknowledge the incorporation of more participants in this process. Yet, they imbue themselves with the power of holding the gates of reliable verification, fact-checking authority and critique.

Covid-19 Misconceptions

Journalists recount several misconceptions that have been circulating in relation to the new coronavirus. The types of mal-information do not vary much from one country to another, they mainly suggest that the disease is a “white illness” and that it does not impact the “black population”. Other myths say that the prolonged use of masks can harm the brain, that different personalities in their countries died due to the virus, that there were vaccines already being used (by the time the interviews were conducted, there was not official information about approval or beginning of vaccination in the countries), or that certain types of medicines could cure the patients. Conspiracy theories also circulate, such as a recent one that the patients in CAR who were in confinement received 25 euros per day for “political reasons” so that the World Health Organization would give financial resources to the government. Other types of information disorder concerned the use of chloroquine as a treatment or that the donations arriving from Europe were contaminated with the virus.

“People have a lot of prejudices, for example, ‘it’s very hot here, the virus cannot circulate in Africa’ (…). All this was an alert, we had to go to the health professionals, to the ministry, to give the right information”. (F-Talato, originally in French)

Since the first cases affected important people in the DRC, it was said that “normal citizens” could not be contaminated, recalled M pointing to a list of other myths that circulated in the country:

“There are also others who think that there are animals that are forbidden to be contaminated, or that you should not eat raw meat, you should not eat fish (…) You really have to be in the middle of all this to say ‘no, it’s not true’, and go to the source”. (M-Congo Check, originally in French)

Emitters of False Information

The main emitters of Covid disinformation range from public authorities and opposition leaders in a non-institutional way, as well as people seeking economic gains. Although it is not possible to affirm precisely, the journalists suggested the emitters are dispersed and non-orchestrated movements. In CAR, R believes it is mainly the local population that is motivated to spread misconceptions due to the absence of the authorities: “the lack of communication from the authorities encourages the population to go for the fake news.”

In the DRC, the biggest propulsors of false information are members of the political class, affirmed D who likewise criticized the existent gap of communication: “when a message is not well communicated, it disorients the population”. In the capital Kinshasa, political or opinion leaders could be the ones fostering disinformation, but in eastern DRC, M says not to be certain who would be disseminating.

“Here in the province of North Kivu, I won’t be sure. It is more often personalities who are looking for popularity who do it (…) for the sympathy of the population. Or if they are pastors, men of Gods (…) it depends on the interest of each and every one”. (M-Congo Check, originally in French)

Audiences

Talato journalists do not have a proper evaluation of their audience reach. The website had between four and five thousand pageviews in one day by the time the interviews were collected with the possibility of having “dozens of hundreds of shares”, said R. They only have a perception of what their audience could be:

“There is a significant number of people who are affected, but I can’t give exact figures or an estimate. It is a work that is bearing fruit”. (F-Talato, originally in French)

The audience is not only composed by the internet users but by indirect ways of receiving the fact-checked content, such as radios that use the information published on the website of Talato.

“The work we do is picked up by a number of stations, radio stations, or in the print media because Talato can be considered as a press agency that gives the news and that all the others relay”. (F-Talato, originally in French)

This process works similarly in the DRC where Congo Check supplies verified information to other media. So as to reach more citizens, the project created a program called ‘SMS Covid19’ to inform by mobile messages people who do not have access to internet. In June 2020 there were sent around 11,000 SMS to one thousand subscribers exclusively with Covid-19 content. Congo Check website had around 40 to 50 thousand pageviews. S does not have an exact dimension of the audience outreach but hopes that they are able to touch around 100,000 people by its verification work. They also emphasized the almost three thousand Twitter followers of Congo Check and the 15 thousand on Facebook. The reporters recognized the challenges of connection to internet and that this still imposes hindrances to online engagement.

Social Media as a Tool

When asked how social media can be a tool to help sensitize the population, both Congo Check and Talato journalists showed enthusiasm to use the online engagement for this purpose. They hold the view that it is necessary to educate society on media literacy and on how to better consume information, as well as to educate the opinion leaders so they learn how to adequately communicate in the virtual spaces. They advocated for the need to train journalists in the values that guide the profession so as to avoid reporters falling themselves into the mythic cycle of misconceptions. It is as well necessary to provide conditions for them to verify. G argued that knowing how to work in social networks should be seen as a component of development in the country.

“It’s a question of education. (…) A lot of people today are on social networks to disseminate photos to slander, and not to get good information. (…) Social networks are a way of development in our country, the internet is a way of development. (…) There are some provinces where there are no networks, there is no internet, people are there on their own”. (G-Talato, originally in French)

Verification is a hard duty agreed the Congolese journalists, a work that “should not be abandoned” said D, where the journalists cannot “lower their arms” and pursue informing with the “good” information. The social networks are a channel through which it is possible to reach several people in a short period of time and that can be used for “the good cause, use it for the truth, use it to build and not to destroy, use it to heal and not to kill”, said D.

The awareness raising should start by the basis in the communities, informed M, to teach how to use social media with a conscious manner. As a way of contributing to enhance media literacy, the Congolese journalists recently launched a program named ‘Congo Check Academy’ to inform and train internet users and bloggers the basic rules of verification of content on how to avoid disseminating false information on the web. “We have a responsibility to share”, said S.

Against Covid-19 Myths and Misconceptions on Twitter

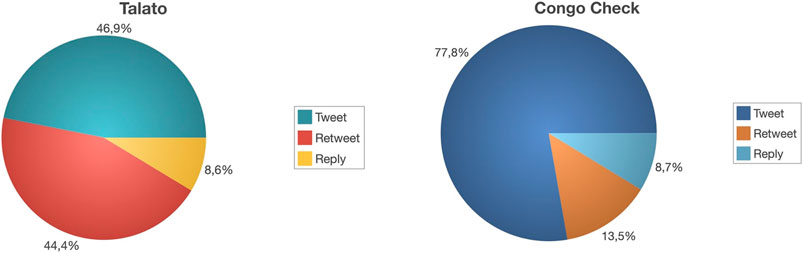

The dataset of ABCA analyzed 81 posts – 38 original Tweets (47%), 36 Retweets (44%) and seven replies. Congo Check had 126 posts – being them 98 original Tweets (78%), 17 Retweets and 11 replies (Figure 1).

Both Congo Check and Talato showed similar patterns of twitter handling, such as engaging with international NGOs and official representations in their country by ‘tagging’ them. This strategy of relating to official authorities confers legitimacy and credibility to the journalists’ work. There have been though some differences between them that are compared below.

Talato did not create a Twitter account of its own and used the bloggers’ association profile, similarly with Congo Check as they used their already created profile to disseminate verified information on the coronavirus. The difference is that Congo Check was designed exclusively for fact-checking purposes unlike ABCA that embraced the work done by Talato but had other purposes, such as advocating for freedom of press. ABCA profile was open in July 2018, it followed other 478 Twitter accounts. Five months when the last post in the sample was tweeted (October 3, 2020), the profile gathered 1,268 followers, having added more than 300 new followers. As for Congo Check, it was created in March 2018 and by October 22, 2020 it had posted 608 Tweets and followed other 146 accounts. Five months of the last post of the sample (October 19, 2020), Congo Check had 2,707 followers, having added more than 600 new ones. This relation appears to be proportional to the size of Congo Check since it has the double of fact-checkers as members.

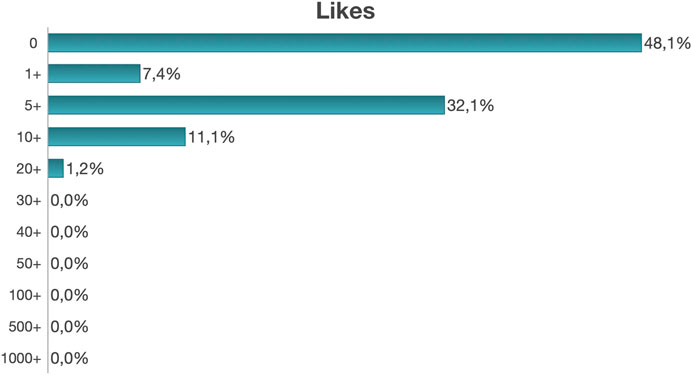

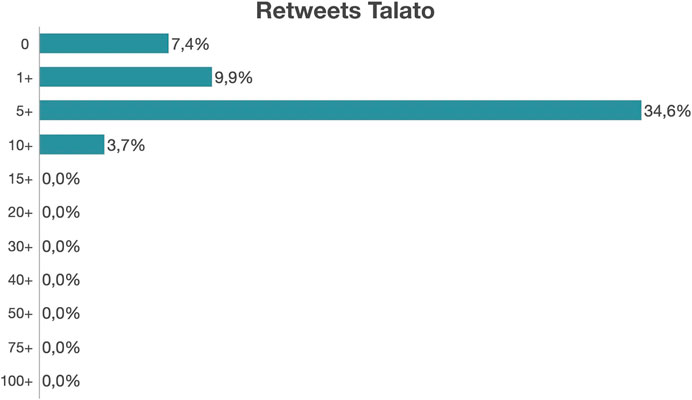

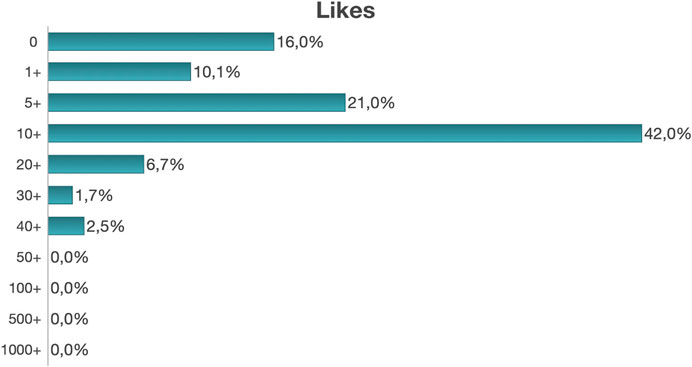

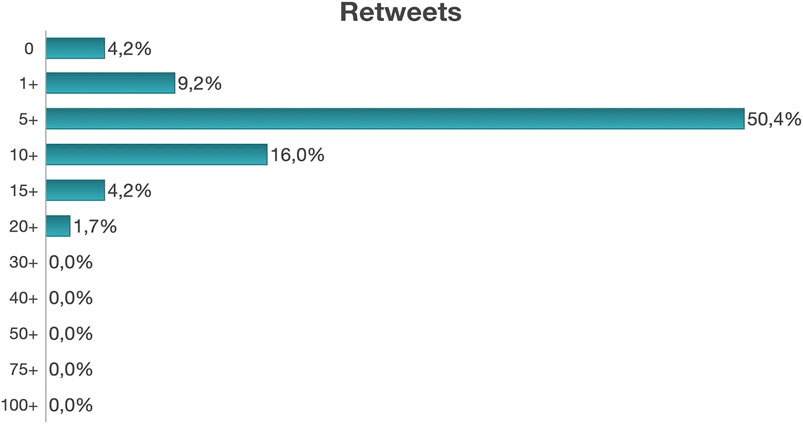

Talato created original posts, but equally retweeted on the same volume. The retweets were mainly originated from the Talato founder’s personal account. In contrast, the great majority of Congo Check comprehended original tweets and very few retweets. Disseminating original tweets not only make journalists informational providers and sense-givers but imbue them with the role of closing possible knowledge gaps so as to reduce uncertainties and foster preventive action. The engagement of ABCA with other accounts was not significant, it received few replies and few ‘likes’ (Figure 2). One 10th of ABCA posts received more than ten likes. The sharing of their posts was low, almost 35% of them was retweeted five times (Figure 3). In comparison, Congo Check showed a little more engagement with 42% of the posts receiving ten likes (Figure 4) and 80% of its posts were more than five times retweeted. The majority of the tweets (50%) was shared between five and less than ten times (Figure 5). Their potential for creating cascade effects of tweets is still to be harnessed.

From the 81 tweets analyzed in ABCA’s profile, 57 were related to Covid-19, corresponding to two thirds. In Congo Check, less than 40% of the posts were related to the pandemic issues (45 out of 120 posts) indicating that the team tried to balance the Covid-19 verification with other topics that were also subject to misconception, mainly political issues. From end of July, the number of ABCA tweets fell drastically for no more than three posts per week. There were weeks at the last two months of the sample with no posts. Congo Check had a similar pattern, in the first two months of the sample most posts concerned the coronavirus that reached the peak in mid-June. After that, there was a tendency of reducing the amount of Covid-19 related posts and on the last two months of the sample, the pandemic was not mentioned in the Twitter feed of Congo Check. This ‘disappearance’ of Covid-19 information in the last portion of the dataset could be a reflection of what was reported in the press (Soy 2020) that some African countries had not been dramatically hit by the virus with figures lower than other continents.

ABCA posted many tweets sharing links of articles published elsewhere instead of articles published in Talato’s website. It was perceptible that most of the tweets publicized what ABCA was doing (e.g., workshops and trainings), advertisement about the need to halt false information, but not much was posted on top of the verification work of Talato itself, only when the updated numbers of coronavirus cases in the country were released. This platform could have been better used to post the headlines and the verified content in order to correct and debunk the wrong facts, as Congo Check did. This was seldom seen in the Twitter handling of ABCA. On the other hand, Congo Check mainly shared the headlines of verified content addressing to its website. It also advertised the project’s achievements. A clear example of the journalists moving beyond the virtual sphere and creating offline engagement with people who are not regular users of social media was the posts on the street mobilization for their program of ‘SMS Covid-19’. This hybridity of online-offline arrangement offers more visibility turning their verification work more impactful and conferring their work higher informational value.

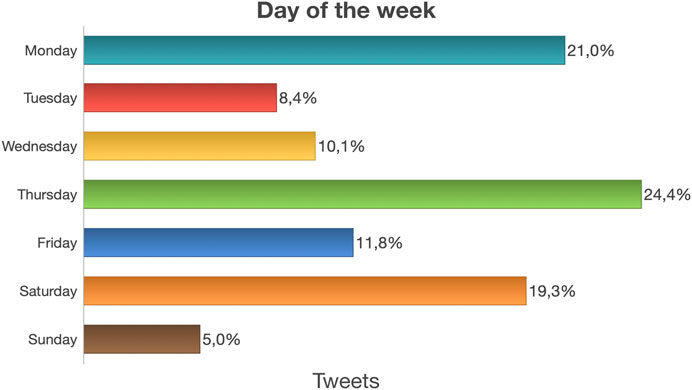

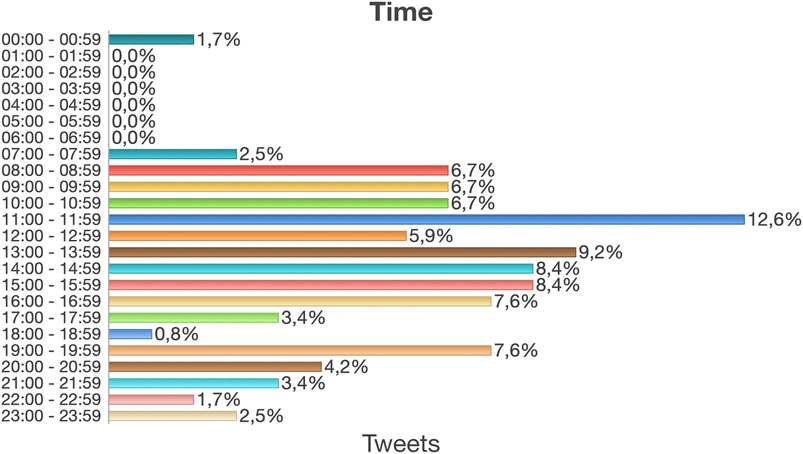

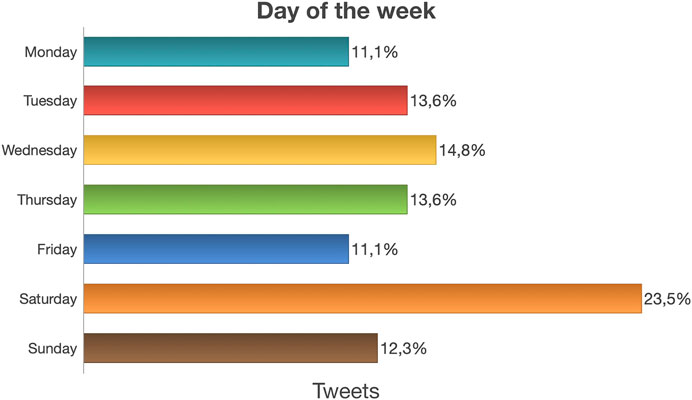

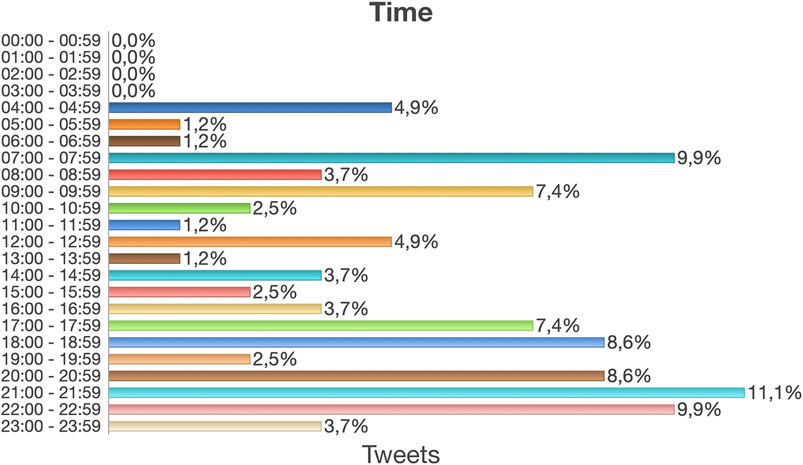

Congo Check had a pattern of tweeting mainly on Mondays, Thursdays and Saturdays (Figure 6) having a peak of the day in the late mornings and early afternoon (Figure 7). It is not possible to infer that such pattern resembles an integrated communication strategy for disseminating on Twitter. As for Talato, it was not observed a consistent pattern of organized posts. Majority of ABCA Tweets were posted on Saturday, followed by Wednesdays, Tuesdays and Thursdays with the same proportion (Figure 8). The flow of tweets were usually in the morning from 7–10 am with a peak of tweets in the evening from 5–11pm (Figure 9). It shows there was not a systematized strategy of communicating through social media. The level of engagement might have been higher if there was a plan of posting on Twitter during particular days of the week and on particular hours. Noting that Talato journalists work on a voluntary basis and have to conciliate with other income generating jobs. This is what may explain that the higher flow of posts happened in the evenings. If a communication strategy for social media networks was developed, the level of interaction could have been higher.

Tagging international representations and organizations in the country gives legitimacy and reliability to both projects. The level of trustworthiness could also be expanded if ABCA and Congo Check attempted to engage with local based organizations, entities, associations, opinion and community leaders. Considering that online social media should not be seen as disconnected from offline social spaces, a more local and contextual engagement of the posts with local actors could be more impactful.

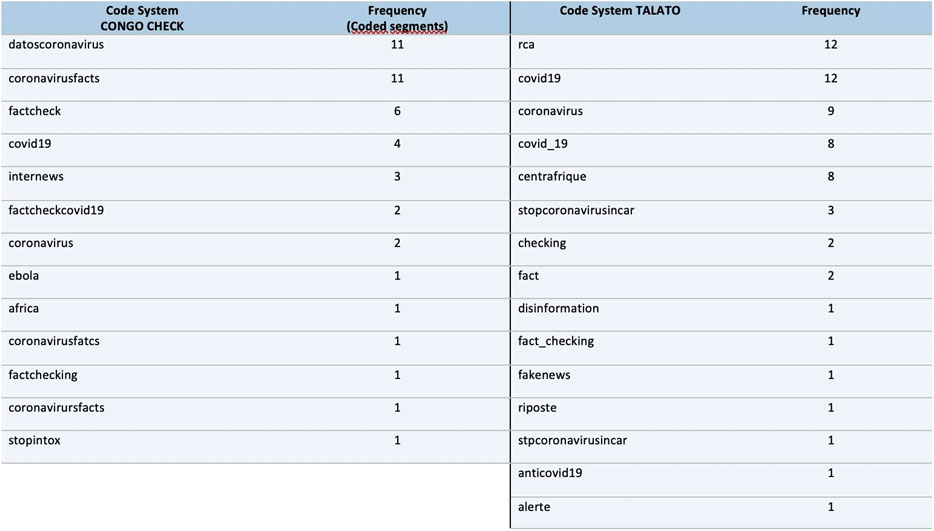

How did myth and misconceptions appear in the Twitter analysis of Congo Check and ABCA? In practice, the definitions that characterize myth, rumor and the three types of information disorder did not essentially differ in the dataset, they emerged concomitantly in the analysis under the codes of ‘fake news’, ‘fact checking’ and ‘coronavirus facts’. Few codes used explicitly the terms ‘stop intox’ and ‘disinformation’. There is in effect no differentiation of the concepts appearing under a loose idea of false information. The code system for each media project was created based on the used hashtags. There were 15 codes on the ABCA account and 13 codes on Congo Check (Figure 10).

ABCA tweeted on 13 May a call for fighting against the spread of the new coronavirus. The dissemination of false news associates fear and armed violence, informed the post that used hashtags: #Coronavirus #RCA #StopCoronavirusInCAR. It said that: “more than 2,6 million inhabitants are in need for urgent humanitarian assistance” (originally in French). This post attached visual graphic illustrating the number of cases and received ten likes and eight shares.

On 18 June, ABCA informed the updated numbers of Covid-19 cases in the country and criticized the difficulties to track the circulation of the virus due to lack of detailed information about the regions. It tagged journalists, a radio station, the EU representation in the country, the UN mission in CAR, the national government and the Health Ministry. It used the hashtags #Covid_19 #RCA and attached a scanned official copy of the cases and visual graphics. It had four shares and nine likes.

A workshop conducted for journalists and bloggers about the protective measures against Covid-19, the rights of the patients, as well as training on fact-checking mechanisms and on the code of good practices for media was announced by ABCA on 4 July. This workshop received the support of the United Nations. It tagged the UN peace mission in the country and attached four photos of the event. It had 20 likes and six shares – including a share of the UN mission spokesperson who mentioned back ABCA who further tagged the CAR government and the official account of the UN System in the country.

Some Congo Check tweets informed that it was false that the Congolese spokesperson had died due to the coronavirus (8 June, 7 shares and 15 likes); or that it was false that the coordinator of the national response team against Covid-19 had lifted the state of health emergency (19 July, 9 shares and 13 likes). These posts included a link with the verification articles on Congo Check’s website. They used hashtags #FactcheckCovid19 #CoronavirusFacts #DatosCoronaVirus and tagged the presidency and the Congolese Health Ministry, as well as international organizations such as Doctors without Borders and a media development NGO.

Congo Check used Twitter to publicize their initiative of registering phone numbers to receive verified information by SMS. On 30 May, they announced the ‘SMS Covid‐19’ and received 14 shares and 24 likes. They tagged international representations in the DRC, NGOs and media and attached a banner with information on how to register in the program. A month later, on 4 July, a post announced that the Congo Check team was going out to the streets to inform the population about their SMS service. It received 9 shares and 27 likes. When a post denounced on 7 September that a journalist member of Congo Check had been arrested by the police and was kept in the military intelligence office in Goma, it received 17 shares and 30 likes. It tagged the profile of the journalist arrested and advocacy organizations for press freedom.

The social media interaction could have been more sustained and spread if local connections would have been established with more groups of citizens rather than mainly authorities. An important tactic for increasing sharing on social media is to create ‘coalitions’ with other actors of civil society. Congo Check showed some advances in building alliances, but Talato did not do it meaningfully. The use of hashtags should be more strategic, consistent and avoid misspellings. If a post uses several hashtags of the same type, a cascade effect of the conversation gets disperse and may decrease the flow of interaction with other tweets. It is additionally necessary to take into account the digital divide that keeps several people away from the online networks since owning mobile data is sometimes not affordable. The impact of social media is still limited in these contexts, but an effort in engaging local-based organizations and associations that might have some social media accounts could be a strategy so as to involve them in the conversation of misconceptions and encourage that they address these concerns within the sphere of their communities on offline spaces. The key argument is the need for journalists fact checkers to curate news online and offline and to work with society groups on the ground providing corrective information as a way of touching communities that might have little or no internet access.