- Faculty of Science Division II, Tokyo University of Science, Tokyo, Japan

A previous study categorized uncommon names in present-day Japan. However, it was presented in Japanese mainly for native Japanese speakers and thus failed to explain shared knowledge about naming practices, making it difficult for non-native Japanese speakers to understand the study. It is important to share cultural practices not only within but also beyond the culture. Moreover, considering that Japanese names are difficult to read, reducing the risk of failing to read names correctly is helpful especially for non-native Japanese speakers. Therefore, by adding supplementary explanations, this paper systematically describes the characteristics and patterns of uncommon names in present-day Japan. Uncommon names largely take two forms: names with an uncommon reading of Chinese characters and names with uncommon Chinese characters. Regarding the reading, there are three types: 1-1) names that abbreviate the common reading of Chinese characters, 1-2) names that are pronounced as a foreign word, and 1-3) names that are pronounced based on the meaning/image of Chinese characters. Regarding the writing, there are two types: 2-1) names with Chinese characters used infrequently and 2-2) names with silent Chinese characters adding to the semantic meaning without contributing to the pronunciation. Further, a combination of these methods makes names more unique.

Introduction

Prior studies have demonstrated that unique names increased over time in several countries, such as Germany (Gerhards and Hackenbroch, 2000), the U.S. (Twenge et al., 2010; Twenge et al., 2016), Japan (Ogihara et al., 2015; Ogihara and Ito, 2020; for reviews, see Ogihara, 2017, 2018) and China (Cai et al., 2018; but also see Ogihara, 2020b). Yet, how parents/guardians express uniqueness in names can differ across cultures (e.g., Ogihara, 2020b). In this paper, I explain how people in Japan give uncommon names to their babies in a manner understandable to non-native Japanese speakers.

Uncommon Names in Present-Day Japan

There exist various patterns of unique names. To understand the underlying nature of the phenomenon of giving uncommon names to babies, it is important to describe the characteristics of uncommon names and to categorize them. Considering that unique names have been investigated across various academic fields such as humanities (e.g., linguistics, anthropology), social sciences (e.g., psychology, sociology), and natural sciences (e.g., medicine, engineering), this task is vital as a first step.

One previous study systematically described the characteristics and patterns of uncommon names in present-day Japan (Ogihara, 2015). The author analyzed actual (not hypothetical) baby names obtained from private companies (e.g., Ogihara, 2020a) and municipality newsletters (e.g., Ogihara and Ito, 2020).

However, the paper (Ogihara, 2015) was presented mainly for native Japanese speakers and written in Japanese, making it difficult for non-native Japanese speakers to understand. Culturally shared knowledge about Japanese names and naming practices was not explained in the paper (Ogihara, 2015). Thus, even if the paper is translated into other languages with translation software, the difficulty for non-native speakers would still remain given the lack of information.

To globally and internationally discuss naming behaviors/practices and advance research on these topics, it is also necessary to help non-native Japanese speakers understand naming practices in Japan. Cultural factors should be examined from both internal and external perspectives. For people within a culture, such cultural factors are too natural and taken for granted, and thus their essence may be overlooked. To this end, sharing cultural naming practices within and beyond Japan is required.

Naming Practices in Japan

Japanese names are difficult to read correctly. Here, “correctly” means not differently from the original readings that parents or guardians gave. Indeed, even native Japanese speakers cannot read part of names correctly at first glance. More specifically, in most cases, they can guess possible readings, but they cannot always choose the correct one from among several options. Yet, there are also times when native Japanese speakers have no idea how to read a name.

The reason why Japanese names are difficult to read correctly is the usage of Chinese characters. In Japan, three types of characters can be used for baby names: hiragana, katakana, and Chinese characters. Hiragana and katakana are phonograms, that is, symbols representing speech sounds without reference to meaning, like the letters of the alphabet. Their readings are fixed (e.g., hiragana さ and katakana サ are always pronounced as sa), so no mistakes can be made when reading names using hiragana/katakana. For instance, the name さくら (Sakura) is always pronounced as sakura.

In contrast, Chinese characters are ideograms, symbols representing a concept without reference to sound. Thus, their readings are flexible. Many Chinese characters have multiple formal readings in Japan unlike in China, where most Chinese characters have one reading (Ogihara, 2020b). For instance, take one of the most common written forms of boys’ names, 大翔. The Chinese character 大 (meaning big or large) has many readings, such as dai, tai, hiro, and haru in Japan. In the same way, the Chinese character 翔 (meaning fly or wing) is pronounced in multiple ways, such as to(bu), ka(keru), and sho. Thus, their combination 大翔 can be read in many ways, such as Daito, Daisho, Taito, Taiga, Taisho, Hiroto, and Haruto.

Japanese learn the formal readings of Chinese characters in schools. Thus, people can assume the most likely reading of a Chinese character (the most frequently used reading in most cases), but it is not always the case that the assumed reading is consistent with the reading intended by parents/guardians. This practice makes reading Japanese names complicated.

Even more complex, parents can give whatever readings to a Chinese character in addition to the formal readings of it in the naming context (Ogihara, 2020b). This is not prohibited by law. Thus, for instance, people can read 大翔 as Tsubasa and Sora in which the formal readings of the characters are not included. People do not learn such new readings in schools. This practice makes reading Japanese names much more complicated.

So far, I have explained the difficulty of reading names. However, there is another difficulty related to Japanese names: how they are written. Multiple Chinese characters can be used to write the same pronunciations. For example, こはる (Koharu) can be written such as 小春, 小陽, 小晴, 小遥, 小暖, 小華, 小桜, 心春, 心陽, 心晴, 心遥, 心暖, 心温, 心花, 胡春, 瑚春, 瑚遙, 瑚華, 瑚桜, 湖春, 洸晴, 木春, 来春, 恋華, 虹花, 香遥, 紅春, and 向桜 (also こはる in hiragana; Ogihara and Ito, 2020). The way these characters are read/pronounced is the same, but the ways they are written are different. Thus, they are different names.

Practical Implication

Describing patterns of uncommon names and their characteristics is important not only for researchers in various fields (e.g., psychology, sociology, anthropology, linguistics, medicine, and engineering), but also for people in general. This is because such descriptions enable understanding and interpretation of uncommon names, which can decrease the risk of being unable to read a name or of reading it incorrectly. In communication with others, being unable to read a name and reading a name incorrectly should be avoided.

As explained above, many Chinese characters used in Japan have multiple readings. Thus, it is impossible to perfectly predict the reading of a name. Yet, it is possible to avoid situations where one cannot read a name at all and to increase the likelihood of reading the name correctly.

This information is more effective and useful for non-native Japanese speakers. For example, medical service workers (e.g., doctors, nurses, and hospital staff) and educational service workers (e.g., teachers, instructors, and school staff) frequently face situations where they must read names correctly. Many people whose native language is not Japanese work in Japan. Because naming practices differ widely across cultures, it is natural that they are unfamiliar with Japanese naming practices. Japanese names (especially recent baby names) are complicated. Considering that even native Japanese speakers cannot read part of names, reading names correctly is more difficult for non-native Japanese speakers. Thus, for them, reducing the risk of failing to read names correctly is crucial.

Present Paper

To help non-native Japanese speakers fully understand uncommon names in Japan and to increase their probability of reading such names correctly, I summarize patterns of uncommon names in present-day Japan and systematically describe their characteristics. I add sufficient explanations of Japanese names and naming practices, which were lacking in the previous paper (Ogihara, 2015).

Patterns and Characteristics of Uncommon Names

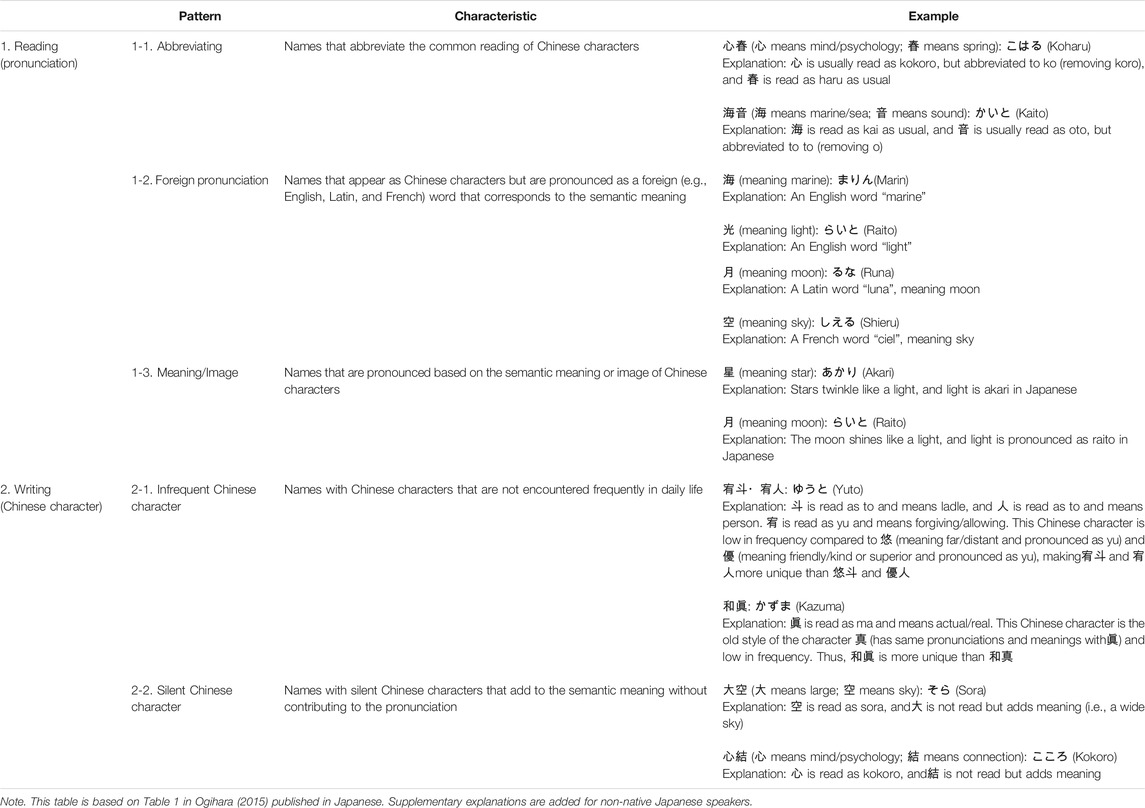

Uncommon names largely take two forms in present-day Japan: 1) names with an uncommon reading/pronunciation of Chinese characters and 2) names with uncommon Chinese characters (Table 1).

1. Names with an Uncommon Reading/Pronunciation of Chinese Characters

Among names with uncommon readings, there are three types: 1-1) names that abbreviate the common reading of Chinese characters, 1-2) names that appear as Chinese characters but are pronounced as a foreign word that corresponds to the semantic meaning, and 1-3) names that are pronounced based on the semantic meaning or image of Chinese characters.

1-1. Names that Abbreviate the Common Reading of Chinese Characters

Most Chinese characters have several formal readings. Parents/guardians abbreviate them and give them an uncommon reading, which makes names unique.

For example, 心春 (心 means mind and psychology, and 春 means spring) can be read as こはる (Koharu). 心 is usually read as kokoro, but abbreviated to ko (removing koro), and 春 is read as haru as usual (this is a common reading). A similar but slightly different pattern can be found in 心美 (美 means beautiful), which can be read as ここみ (Kokomi). 心 is read as koko (removing ro from kokoro), and 美 is read as mi as usual (this is a common reading).

Another example is 海音 (海 means marine and sea, and 音 means sound), which can be read as かいと (Kaito). 海 is read as kai as usual, and 音 is usually read as oto, but abbreviated to to (removing o).

1-2. Names that Appear as Chinese Characters but are Pronounced as a Foreign Word that Corresponds to the Semantic Meaning

Giving an uncommon reading of a Chinese character by reading the character with the pronunciation of a foreign word that corresponds to the character’s semantic meaning makes names more unique. This method deviates from the popular reading of a given Chinese character.

For instance, 海 (meaning marine) is usually read as kai or (u)mi and used in such as 海斗 (かいと; Kaito) 拓海 (たくみ; Takumi), and 七海 (ななみ; Nanami). However, 海 is uniquely read as まりん (Marin), corresponding to the English word “marine”. Another example is 光 (meaning light). 光 is usually read as hikari or hikaru, but is uniquely read as らいと (Raito), corresponding to the English word “light”.

The foreign pronunciations are not limited to English words. For example, 月 (meaning moon) is usually read as tsuki or zuki and used in such as 美月 (みつき; Mituki) and 葉月 (はづき; Hazuki). However, 月 is uniquely read as るな (Runa), corresponding to the Latin word “luna” meaning moon. Moreover, 空 (meaning sky) is usually read as sora, but it is uniquely read as しえる (Shieru), corresponding to the French word “ciel” meaning sky.

1-3. Names that are Pronounced Based on the Semantic Meaning or Image of Chinese Characters

Each Chinese character has a meaning or image. Parents give readings based on the semantic meaning or image of Chinese characters. Such readings also deviate from the common readings of a Chinese character.

For example, 星 (meaning star) is usually read as hoshi or sei, but read as あかり (Akari). Stars twinkle like a light, and light is akari in Japanese. This is not an official reading of the Chinese character.

Similarly, 月 (meaning moon) is usually read as tsuki or zuki, but read as らいと (Raito). The moon shines like a light, and light is pronounced as raito in Japanese. 翔 (meaning fly or wing), which is usually read as sho but read as つばさ (Tsubasa; wing is pronounced as tsubasa in Japanese), is another instance of this naming mode.

2. Names with Uncommon Chinese Characters

There are two types of names with uncommon Chinese characters: 2-1) names with Chinese characters that are not encountered frequently in daily life and 2-2) names with silent Chinese characters that add to the semantic meaning without contributing to the pronunciation.

2-1. Names with Chinese Characters that are not Encountered Frequently in Daily Life

Using uncommon Chinese characters that do not appear frequently in daily life and in baby names can make names unique. Even if the pronunciation of two names is the same, if the characters are written differently, they are different names.

For example, the popular pronunciation Yuto (ゆうと) can be written in many ways, such as 悠斗 and 宥斗. Both names use the same Chinese character 斗 (meaning a ladle), which is read as to. Both Chinese characters 悠 (meaning far/distant) and 宥 (meaning forgiving/allowing) are pronounced as yu, but their frequencies of usage differ. Although the Chinese character 悠 is frequently used in daily life and in baby names, 宥 is not. This usage of an uncommon Chinese character makes 宥斗 more unique than 悠斗.

The same pattern is found in the comparison between 優人 and 宥人, both of which are also pronounced as Yuto. Both names use the same Chinese character 人, which means person and is pronounced as to. Although the Chinese character 優 (meaning friendly/kind or superior) is frequently used in daily life and in baby names, 宥 is not. This usage of an uncommon Chinese character makes 宥人 more unique than 優人.

Another example of this naming mode involves using the old style of Chinese characters (旧字体) in Japan. Parts of Chinese characters are very complicated and difficult to write, so a new character style (新字体) was introduced to simplify the old character style. Thus, although both the old and new character styles have the same meanings, the old character style is basically more complicated than the new character style. Parts of uncommon names given to babies are based on this difference. For instance, 眞 is the old style of character 真 (meaning real and actual) and is used in 和眞 (かずま; Kazuma) and 悠眞 (ゆうま; Yuma), which are less popular than 和真 (かずま; Kazuma) and 悠真 (ゆうま; Yuma). Thus, if you know both character styles of a Chinese character, you can guess how to read the character. Another example of using old style of Chinese characters can be found in 廣 (meaning open/large and pronounced as kou or hiro), which is the old style of the character 広. This old style Chinese character is used in names such as 廣太郎 (こうたろう; Kotaro) and 廣之 (ひろゆき; Hiroyuki), which are more unique than 広太郎 (こうたろう; Kotaro) and 広之 (ひろゆき; Hiroyuki).

2-2. Names with Silent Chinese Characters that Add to the Semantic Meaning Without Contributing to the Pronunciation

Each Chinese character used in baby names is usually pronounced. However, in this naming mode, a Chinese character is not pronounced, but it adds semantic meaning to the name (i.e., works as a silent Chinese character).

For example, 大空 (大 means big/large and 空 means sky) is read as そら (Sora). 空 is usually read as sora, but 大 is not pronounced, which adds the rich meaning of big or large (i.e., a wide sky). Here, 大 works as a silent Chinese character. Compared to only 空, 大空 gives a richer image and makes a stronger impression on others. Such an image and impression may be what parents want their babies to be. This enables parents to show more clearly and explicitly their aspirations and expectations for their babies and others. 青空 (そら: Sora) is another similar example: 青 (meaning blue) is usually read as ao, but it is not read here but enriches the meaning (i.e., a blue and clear sky). 青 is the silent Chinese character in this context.

As another instance of this mode, 心結 is read as こころ (Kokoro). 心 means mind and psychology and is read as kokoro. 結 means connection and is usually read as ketsu or yu(u), but in this case is not read. Here, 結 works as a silent Chinese character (is not read but adds meaning). A similar example is 心優, which is also read as こころ (Kokoro). 優 means kind and is read as yu or yasashii. Yet, this character is not pronounced, instead adding the meaning and image (i.e., kind-hearted).

Combinations of the Methods

It is not always necessary to use more than one of the methods explained above to give uncommon names because a single method is sufficient. Yet, combinations of these methods can make names more unique.

For example, 月雫 (るな: Runa) is constructed based on two of the methods above: foreign pronunciation (1-2) and a silent Chinese character (2-2). As explained above, 月 is read as るな (Runa), following the Latin word meaning moon. 雫 (meaning droplet) is usually read as shizuku, but in this case is not read, only adding an image of a droplet (i.e., a droplet of the moon). 愛月 (るな: Runa) is another instance of the same combination of the two methods. 月 is read as るな (Runa), but 愛 (meaning love; usually read as ai) is a silent Chinese character.

As another example, 輝星 is read as らいと (Raito), in which the meaning/image (1-3) and silent Chinese character (2-2) methods are used. Although 星 (meaning star) is usually read as hoshi or sei, here it is read as raito. Stars twinkle like a light, and light is pronounced as raito in Japanese, which is an unusual and unofficial reading. 輝 (meaning shining) is usually read as ki or kagaya(ku), but works as a silent Chinese character, adding the meaning of shining (i.e., a shining star). In the same combination of the two methods, both 大翔 and 飛翔 are read as つばさ (Tsubasa). Specifically, as I explained above, 翔 (meaning fly or wing) is usually read as sho but read as tsubasa (wing is pronounced as tsubasa in Japanese). 大 (meaning big/large) and 飛 (meaning flying) work as silent Chinese characters and add the meaning of being big (i.e., a big wing) and flying (i.e., a flying wing).

Discussion

In this paper, I summarized patterns of uncommon names in present-day Japan and systematically describe their characteristics in a way that even non-native Japanese speakers can understand. In other words, I reviewed how parents have given uncommon names to their babies in Japan in recent years. There are mainly two methods: 1) giving an uncommon reading/pronunciation to Chinese characters and 2) giving uncommon Chinese characters. There are some typical patterns in each of the two methods.

Regarding the reading, there are at least three methods: 1-1) abbreviating the common reading of Chinese characters (abbreviating), 1-2) reading Chinese characters with the pronunciation of a foreign (e.g., English, Latin, and French) word that corresponds to the semantic meaning (foreign pronunciation), and 1-3) giving readings based on the semantic meaning or image of Chinese characters (meaning/image). Because Chinese characters used in Japan have multiple readings, it is difficult to read Japanese names correctly. These methods further increase the difficulty of reading Japanese names correctly. Regarding the writing, there are two methods: 2-1) giving Chinese characters that are not encountered frequently in daily life (infrequent Chinese characters), and 2-2) including silent Chinese characters that add to the semantic meaning without contributing to the pronunciation (silent Chinese characters). In addition to each of these independent methods, a combination of these methods makes recent names more unique, further increasing the difficulty of reading names correctly.

Previous studies have indicated that unique names increased in Germany (Gerhards and Hackenbroch, 2000), the U.S. (Twenge et al., 2010; Twenge et al., 2016), Japan (Ogihara et al., 2015; Ogihara and Ito, 2020; for reviews, see Ogihara, 2017, 2018) and China (Cai et al., 2018; but also see Ogihara, 2020b). Yet, methods of expressing uniqueness in names can differ across cultures (e.g., Ogihara, 2020b). Moreover, to capture the underlying nature of the phenomenon of giving unique names, it is important to summarize patterns in uncommon names. This work is crucial because unique names have been examined across various academic fields such as humanities (e.g., linguistics, anthropology), social sciences (e.g., psychology, sociology), and natural sciences (e.g., medicine, engineering). One prior study achieved this in the context of Japan (Ogihara, 2015). However, the study was presented mainly for native Japanese speakers, and thus it was difficult for non-native Japanese speakers to follow. To advance the global and international investigation of naming practices, it is also necessary to help non-native Japanese speakers understand these practices and behaviors. Therefore, there was a need for an explanation of uncommon naming methods presented in a way that even non-native Japanese speakers can understand.

From a practical perspective, categorizing uncommon names and describing their characteristics is important for people in general as well as researchers in various academic fields (e.g., psychology, sociology, anthropology, linguistics, medicine, and engineering). Although it may be difficult to read Japanese names always correctly, this work can contribute to increasing the probability of reading Japanese names correctly. Considering that Japanese names (especially recent baby names) are complicated, this importance is more pronounced for non-native Japanese speakers who are unfamiliar with Japanese naming practices.

Limitations and Future Directions

This paper does not capture all types of uncommon names in present-day Japan because there are many methods to give uncommon names. Moreover, new methods of giving uncommon names can appear. However, this paper covered the major methods of giving uncommon names in present-day Japan, contributing to a better understanding of uncommon names in Japan today.

It is unclear how the rates of each uncommon naming pattern have changed over time. It might be that some methods have become more popular than others. It would be important to examine the differences and temporal changes in such patterns and the possible reasons for those changes in the future.

Conclusion

Prior work has categorized uncommon names in present-day Japan and described their characteristics (Ogihara, 2015). However, that study was presented in Japanese mainly for native Japanese speakers and thus failed to explain shared knowledge about naming practices in Japan, making it difficult for non-native Japanese speakers to fully understand the study. By adding supplementary explanations, this paper systematically described the characteristics and patterns of uncommon names in present-day Japan. This contributes to sharing cultural practices of naming both within and beyond Japanese culture. Furthermore, given that Japanese names are difficult to read correctly, reducing the risk of failing to read names correctly is helpful especially for non-native Japanese speakers.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Cai, H., Zou, X., Feng, Y., Liu, Y., and Jing, Y. (2018). Increasing need for uniqueness in contemporary China: empirical evidence. Front. Psychol. 9, 554. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00554

Gerhards, J., and Hackenbroch, R. (2000). Trends and causes of cultural modernization: an empirical study of first names. Int. Sociol. 15, 501–531. doi:10.1177/026858000015003004

Ogihara, Y. (2015). Characteristics and patterns of uncommon names in present-day Japan. J. Hum. Environ. Stud. 13, 177–183. doi:10.4189/shes.13.177

Ogihara, Y. (2017). Temporal changes in individualism and their ramification in Japan: rising individualism and conflicts with persisting collectivism. Front. Psychol. 8, 695. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00695

Ogihara, Y. (2018). “Economic shifts and cultural changes in individualism: a cross-temporal perspective,” in Socioeconomic environment and human psychology: social, ecological, and cultural perspectives. Editors A. Uskul, and S. Oishi (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 247–270. doi:10.1093/oso/9780190492908.003.0010

Ogihara, Y. (2020a). Baby names in Japan, 2004–2018: common writings and their readings. BMC Res. Notes 13, 553. doi:10.1186/s13104-020-05409-3

Ogihara, Y. (2020b). Unique names in China: insights from research in Japan—commentary: increasing need for uniqueness in contemporary China: empirical evidence. Front. Psychol. 11, 2136. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02136

Ogihara, Y., Fujita, H., Tominaga, H., Ishigaki, S., Kashimoto, T., Takahashi, A., et al. (2015). Are common names becoming less common? The rise in uniqueness and individualism in Japan. Front. Psychol. 6, 1490. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01490

Ogihara, Y., and Ito, A. (2020). “Unique names increased in Japan over 40 years: baby names published in municipality newsletters show a rise in individualism, 1979–2018,” in The 21st annual meeting of society for personality and social psychology (New Orleans, LA).

Twenge, J. M., Abebe, E. M., and Campbell, W. K. (2010). Fitting in or standing out: trends in American parents’ choices for children’s names, 1880–2007. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 1, 19–25. doi:10.1177/1948550609349515

Keywords: name, uniqueness, reading, writing, Chinese character, baby, Japan, communication

Citation: Ogihara Y (2021) How to Read Uncommon Names in Present-Day Japan: A Guide for Non-Native Japanese Speakers. Front. Commun. 6:631907. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2021.631907

Received: 21 November 2020; Accepted: 12 January 2021;

Published: 15 March 2021.

Edited by:

Stephen Croucher, Massey University, New ZealandReviewed by:

Dr. Paromita Pain, University of Nevada, Reno, United StatesBeverly Jane, California University of Pennsylvania, United States

Copyright © 2021 Ogihara. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yuji Ogihara, eW9naWhhcmFAcnMudHVzLmFjLmpw

Yuji Ogihara

Yuji Ogihara