- Department of Science and Technology Studies, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria

The starting point for this article is that the COVID-19 global pandemic has brought normally invisible, taken-for-granted aspects of contemporary societies into sharp relief. I explore the analytical affordances of this moment through a focus on the nature of the contemporary academy, asking how this was performed on “academic Twitter” in the early months of the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, therefore contributing to work that has characterized contemporary university, research practice, and social media discussion of this. I draw on a dataset of tweets from academic Twitter, systematically downloaded between 1 March and 24 July 2020, that are concerned with the pandemic, analyzing these through a qualitative, multimodal, and practice-oriented approach. I identify themes of the disruption of academic work, of care and care practices, and of critiques of injustice and inequity within academia, but also argue that the ways in which these topics are instantiated—through distinctive repertoires of humor and of emotional honesty, positivity, and gratitude—are central to performances of academic life. The analysis thus further contributes to studies of communication to and by other publics, and in particular, the ways in which the content and form of social media communication are intertwined.

Introduction

I would like to start, if I may, with an anecdote from my own experiences during the early days of the pandemic in Europe. In Austria a hard lockdown came rather quickly into force: we went, it seemed, from vague concerns about other countries to a dramatic curtailment of movement in the space of a few days. In common with many others, my memory of those first days is of uncertainty, of rules and recommendations changing almost by the hour, and of a desperate search for new information. Those early hours, days, and weeks were marked by a dedication to media both new and old. Never before had I sat down deliberately to watch a government press conference; now, it was an event I planned my day around.

I was, both then and now, struck by the extent to which (my) sense-making was taking place through social media. This was a year in which the term “doomscrolling” (Markham, 2020) rose to prominence, and the notion perfectly captures my memory of obsessive scrolling through feeds in an effort to garner more knowledge, more certainty more collective meaning. Social media delivered local information (from the numbers of cases in my city to how to support local businesses), but it also showed how the global communities of which I am a part were making sense of the pandemic. Within my personal filter bubble (Pariser, 2011), academic jokes, stories, and debates were one aspect of this. Social media showed me how (some versions and parts of) academia were experiencing and defining this moment of crisis and change.

It was these experiences that led, in part, to this research, in that I became fascinated by what social media responses to the pandemic were revealing about academic cultures more generally. But the starting point for this article is not only my sense of social media as central to pandemic sense-making, but also a wider appreciation of the analytical affordances of moments of crisis or infrastructure breakdown. “The normally invisible quality of working infrastructure becomes visible when it breaks,” write Leigh Star and Ruhleder (1996), 113: “the server is down, the bridge washes out, and there is a power blackout. Even when there are back-up mechanisms or procedures, their existence further highlights the now-visible infrastructure.” Indeed, the COVID-19 global pandemic has brought normally invisible, taken-for-granted aspects of contemporary societies into sharp relief. In all its horror, the pandemic, its management in specific contexts, and public discourse on and responses to it have acted as analytical lenses through which the attitudes, practices, and values that underpin particular collectives—from nation states to specific institutions—can be rendered visible and therefore debatable. As many commentators have argued, the pandemic offers an opportunity to observe what is present and to suggest what might, and perhaps should, be otherwise.

In this article, I am specifically concerned with academic communities. In taking the pandemic as a moment of crisis in which taken-for-granted norms, assumptions, and ways of living are disrupted and therefore made visible, I seek to explore the nature of the contemporary academy as it was performed on “academic Twitter” in the early months of 2020. I therefore examine social media practices as a way of exploring the experiences of one particular public, that of academic researchers and teachers. In doing so, I build on previous scholarship in Science and Technology Studies (STS) and Higher Education Studies (HES) that has critically examined the ways in which academia is done in contemporary societies, from trends of marketization, massification, or internationalization to increased competition and precarity within academic careers. I am concerned with the following questions: How do scholars know and live in universities today? How are academia and the “good academic” performed, and how are these performances contested? What dynamics shape experiences of academia?

In what follows, I reflect on these questions through a qualitative, multimodal study of tweets from “academic Twitter.” I begin by outlining the literatures and conceptual sensitivities that frame the research, before describing the methodological approach taken. An extended empirical section describes three key aspects of the performances of academic life found within the data. I close by drawing my arguments together and reflecting on the wider implications of the analysis. What does it suggest more generally about academia, social media, and the COVID-19 crisis?

Literatures and Sensibilities

Life and Work in the Contemporary Academy

At the broadest level the question that animates this research concerns the nature of the contemporary academy, and what it is to live and work within it. It thus builds upon, and speaks to, a now extensive body of multidisciplinary work that has sought to characterize university and research practice today. Key themes within this have included the “projectification” of research (Ylijoki, 2014; Fowler et al., 2015), an increase in precarity (Courtois and O’Keefe, 2015; Sigl, 2016; Bataille et al., 2017; Roumbanis, 2019), the implementation of entrepreneurial or capitalistic logics to academic practice (Slaughter and Leslie, 1997; Fochler, 2016; Reitz, 2017; Rushforth et al., 2018), the rise of narratives of “excellence” as one way of auditing academic practice (Lund, 2015; Watermeyer and Olssen, 2016), and demands for international mobility and other often punitive ways of living the “ideal academic” (Lund, 2015; Balaban, 2018). Much of this literature has thus been concerned, explicitly or implicitly, with questions of equity and diversity (Ackers, 2008; Leemann, 2010; Heijstra et al., 2017; Angervall and Beach, 2018), as it suggests that only some people can afford—financially, emotionally, or intellectually—to maintain an existence within academia as it is currently instantiated. Relatedly, it has been argued that the emotional tenor of academic life has become skewed toward anxiety and a sense of insecurity, and away from practices of care or support (Cardozo, 2017; Lorenz-Meyer, 2018; Ivancheva et al., 2019).

This is now a substantial and diverse literature, and one in which there are key disagreements (for instance, concerning the extent to which “neoliberalism” is a helpful framing of the changes that are taking place: Amsler and Shore, 2017; Ball, 2015; Cannizzo, 2018). I do not attempt to review it further here, instead highlighting one aspect that will be particularly pertinent to my discussion: that of the ways in which “living” and “working” are increasingly entangled within academic identities (Felt, 2009). Felt and others have argued that academics exist within “epistemic living spaces” in which the epistemic is mingled with, and enacted through, diverse social, symbolic, and material practices (Felt and Fochler, 2012; Linkova, 2013). Knowledge production, the crafting of a career or professional identity, and other ways of living are thus entangled. Similarly, accounts of academic careers have described the quite stringent work that is required to craft and protect an academic identity, from avoiding imposter syndrome (Taylor and Breeze, 2020) to successfully inhabiting an academic role (Campbell, 2003; Winkler, 2013; Schönbauer, 2020), while discussion of international mobility or of “jetsetter” academics have emphasized the all-encompassing nature of what is required of individuals (Zippel, 2017; Balaban, 2018). Living and working in the contemporary academy appear on the one hand to draw on well-established notions of a “vocation” or “calling” (Shapin, 2009; Berthoin Antal and Rogge, 2020), while, on the other, merging these with more recent expectations of entrepreneurialism, self-reliance, and individual responsibility (Hakala, 2009; Loveday, 2017). Academic identities are therefore performed in ways that mingle knowledge production with informal relationships, the personal with the professional, and the material with the symbolic (Davies, 2020).

Networked Scholarship and Academic Twitter

If the starting point for this research is the question of how life and work in the academy are currently articulated, then a second frame is studies of how these academic lives are performed on social media. A growing body of work explores how academics make use of digital tools and platforms, from the use of online learning tools to academic social networks such as Academia.edu (e.g., Delfanti, 2020; Lupton et al., 2017). Within this, the work of George Veletsianos (Veletsianos, 2016; Veletsianos and Kimmons, 2012) on “networked participatory scholarship” has proven particularly influential. Veletsianos and Kimmons (2012), in the article that introduces the term, suggest that scholarship is changing through the emergence of digital tools; specifically, they write, “Networked Participatory Scholarship is the emergent practice of scholars’ use of participatory technologies and online social networks to share, reflect upon, critique, improve, validate, and further their scholarship” (p.768). This is not simply an amplification or development of existing practices. Rather, their contention is that academic practice is undergoing qualitative changes in ways that are entangled with digital technologies, including the emergence of new kinds of networks and of greater engagement with different kinds of audiences in and outside the academy. Thus, Veletsianos suggests, “paradigmatic shifts in and evaluation of our identity as scholars, the purposes of education and scholarship, and the academic preparation of scholars” (2016, 26) are underway.

One central aspect of this networked scholarship is the use of social media, and a number of studies have addressed the use of Twitter, in particular, by academics (Brantner et al., 2020; Gregory and Singh, 2018; Kimmons and Veletsianos, 2016). Stewart (2016), in an ethnographic study of academic Twitter users, argued that the platform “enables a collapsed space of engagement, wherein the analytic and text-based content of scholarship is shared via often-casual, participatory, and dialogic forms of exchange” (p.72). She charts the use of the platform not only for network-creation but for interactions involving intimacy, vulnerability, and care; as such, the now well-established notion of “context collapse” (Marwick and Boyd, 2011), where scholars may be subject to “unanticipated audiences and attention” (Stewart, 2016, 77), is a key risk. Other studies have shown, however, that academic users of Twitter are alert to these dangers and carefully manage their online presence. Self-disclosure, while potentially involving deeply intimate topics such as mental health or personal and professional challenges within the academy, is selective and tactical (Veletsianos and Stewart, 2016), while online identities are both “authentic” and “fragmented” (ibid; Jordan, 2020): social media users seek to present genuine expressions of the self, but spread across multiple platforms and designed for different audiences. While this work supports the notion of a sea change in academic practice—as Veletsianos and Stewart write, “scholars’ personal lives are often an integral part of online participation and as such mediate emergent forms of scholarship” (2016, 8)—more recent research has pointed out that opportunities to participate in such networked participatory scholarship are not distributed or experienced equally (Gregory and Singh, 2018). “Building an online academic presence,” argued Taylor and Breeze (2020), “is conditioned by the politics of class, race, and gender” (p.3). While Twitter appears to be a key site in which academics can perform identity work, for instance by rendering underrepresented identities within the academy more visible (Veletsianos and Stewart, 2016), not everyone is able to (safely) do this in the same way.

Memes, Communities, and “Folkloric Expression”

While the work described above has explored, in some detail, how scholars use social media, there has been less systematic attention to the content of what they post, with the emphasis largely having been on individual negotiations and performances of academic experience.1 In the context of this study, and of my interest in how academia is enacted, it is therefore important to draw on an adjacent body of work: that which has looked at the content of social media more generally, and specifically the “emerging patterns in public conversations” (Milner, 2018, 1) that can be identified within the rise of “mimetic media”: memes. Memes, Milner suggests, exist “in the space between individual texts and broader conversations, between individual citizens, and broader cultural discourses” (ibid, 2). They therefore offer an opportunity to explore the shared meanings held by (and sometimes contested within) particular communities.

Internet memes have been subject to academic study since at least 2014, when Limor Shifman defined the form as

(a) a group of digital items sharing common characteristics of content, form, and/or stance, which

(b) were created with awareness of each other, and

(c) were circulated, imitated, and/or transformed via the Internet by many users (Shifman, 2014, 41)

As Shifman suggests, memes are both multiple—involving many versions of, for instance, an original image or text—and intertextual, in that they refer to other (online) content. Shifman and others distinguish memes (which are constantly tweaked, for instance, through mimicry or adaption) from virals (a single piece of content with high circulation); memes, then, are inherently communal, forming part of a wider conversation that implies a collective of people “in the know” (Philips and Milner, 2017). The slipperiness of memes is exactly that they travel outside of these implied communities, such that context collapse (Marwick and Boyd, 2011) is inevitable, their meanings are unclear, and the intention of their authors ambiguous. As Dynel notes, “online users’ voices behind their humorous memetic produce [sic] can never be established beyond any doubt” (2021, 191). Philips and Milner (2017) situat such communication as a form of “folkloric expression,” arguing that rather than being something dramatically new, memes, trolling, and other forms of internet ambiguity have many of the same features of folklore (the “lore” of any group with at least one thing in common; p. 25). As with folklore, mimetic expression is vernacular, informal, and simultaneously stable and conservative (referring to “tradition” and widely shared meanings) and dynamic and creative (constantly adapted and remade by individuals). This perspective thus takes us again to understanding such communication as a set of practices that connect shared meanings with individual interpretations of these.

One further aspect of memetic media will be important for my discussion. Memes—like much of the rest of the internet environment—are multimodal, involving diverse communicative modes such as “word, image, audio, video, and hypertext” (Milner, 2018, 24). This, of course, renders them even more complex, as intertextual referencing, remixing, and adaptation can happen in one or several of the modes that they include (an image that tweaks another, or text that quotes or adapts lyrics or phrases; see Figure 1). It is important to note that this multimodality has also become important to virality: even text-only tweets are often captured with screenshots so that they can be circulated as images on other platforms. As I describe further below, I will primarily be focusing on textual content in my analysis, but will seek to pay attention to the ways in which this is situated and extended through other communicative modes.

FIGURE 1. Examples of memes; captured using the search term “You should be writing meme” and showing how both images and text are remixed in multiple combinations. “You should be writing” memes circulate within academically oriented social media but also in communities oriented to writing or study.

Materials and Methods

In describing work that explores the nature of the contemporary academy, networked scholarship, and memetic expression I have uncovered a number of conceptual sensitivities that will shape my analysis. I will, first, be interested in the ways in which contemporary academic life is performed, and particularly in the ways that these performances combine multiple facets of life, knowledge production, and work. Second, I am concerned with how such performances are done on Twitter, viewing academia-oriented tweets as the products of strategic and selective self-presentations. Finally, I treat this social media material as a form of mimetic expression that both references wider community (ies) and shared meanings and involves individual creativity. While I am, as noted, interested in a set of general questions concerning contemporary academic experience (including how scholars know and live in universities today, how academia and the “good academic” are performed, and how these performances are contested), the specific question that structures the following discussion is: how was the contemporary academy performed on “academic Twitter” in the early months of the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic? In line with my interest in performativity and the enactment of community, I take an approach that is ethnographically oriented and qualitative (Marwick, 2013; Hine, 2015), viewing social media material as records of digital practices (Hepp et al., 2017) and thereby constitutive of what they describe. I therefore adapt techniques used for big data analysis of Twitter corpuses, such as bulk download of tweets (e.g., Brantner et al., 2020; Graham and Smith, 2016), in order to create a dataset that is suitable for in-depth qualitative analysis. As described below, the focus of this adaptation was on tightly delimiting the dataset (Dynel, 2021), an approach that allows for an in-depth but inevitably highly specific analysis.

I explore Twitter rather than other social media platforms for two reasons. First, academic Twitter offers perhaps the most consolidated online academic community, and is certainly the most studied (Brantner et al., 2020; Gregory and singh, 2018; Kimmons and Veletsianos, 2016; Stewart, 2016; Veletsianos and Stewart, 2016). Second, it enables the collection of a coherent and clearly delimited dataset via the hashtags #AcademicTwitter and #AcademicChatter (in contrast to, for instance, Facebook, where there would be many relevant groups and users). The material I am concerned with thus consists of 1) tweets that 2) use the hashtags #AcademicTwitter or #AcademicChatter and were 3) published in the period March–July 2020, and 4) contain content (whether in the form of further hashtags or in the topics discussed) relating to the pandemic. This material has been gathered and curated in a number of steps. First, at the end of March 2020, I used Twitter’s search function to find tweets with the relevant hashtags, published in that month, which had been “favourited” 500 times or more.2 Tweets that mentioned or related to the COVID-19 crisis were saved as screenshots. Second, using the tool Twitter Archiver,3 I set up an automated download of all tweets with the hashtags #AcademicTwitter or #AcademicChatter from 4 April 2020 onward.4 Of this material, I have incorporated tweets from the first month (4 April–4 May) with 25 or more favorites into the dataset, along with tweets from the next three months (4 May–24 July) with 500 or more favorites. The result is a corpus of tweets with hashtags #AcademicTwitter or #AcademicChatter from March (17), April (326), May to July (204), or 547 tweets in total across 5 months.

As the preceding description suggests, the dataset has been hand-curated to ensure both a quantity of material that lends itself to in-depth qualitative analysis (hence the decision to largely work with tweets with 500+ favorites, which are limited in number) and the capacity to capture key moments within the pandemic (the choice to include all tweets with 25+ favorites in April). In all cases, by working with tweets with 25+ favorites, the material has achieved some level of virality— here understood as being due to its reflecting shared experiences or opinions within the community of academic Twitter users, with high numbers of favorites seen as a sign of community approval (Graham and Smith, 2016). This process of curation was, of course, imperfect on multiple levels. The aim has been to create a corpus that captures widely appreciated tweets over the early months of the pandemic in numbers suitable for qualitative analysis (Dynel, 2021), but it can be problematized in multiple ways: by excluding hashtags such as #blackintheivory, #pandemicpedagogy, #PhdChat, and #PhDlife, for instance, key constituencies are partially excluded or rendered less visible in the material. It also misses academia-oriented content that used no hashtags at all. Similarly, the balance between producing a dataset that is manageable (focusing on more frequently favourited tweets) and capturing more of the discussion (including less popular tweets) over the course of the pandemic has been a difficult one. Ultimately, the material I work with cannot be seen as straightforwardly representative of online articulations of experiences of academia during the pandemic; rather, it captures key aspects of discussion between users of Twitter (a rather select population within academia more generally) who specifically identify or engage with the communities associated with the hashtags #AcademicTwitter and #AcademicChatter.

Once compiled, the corpus was subject to two forms of analysis. I first carried out a thematic analysis (Rivas, 2018) of the material in order to identify repeated patterns and concerns, using the software MaxQDA as a means of organizing the material and developing a code scheme based on its content. I have, second, combined this thematic analysis with more focused exploration of multimodality (Machin, 2013) and with the conceptual sensitivities mentioned above, paying particular attention to how academia is (articulated as) lived in and embodied. In the discussion that follows, I use this second approach to explore particular tweets or aspects of the content in more detail, and to assess how particular themes are instantiated through social media practices.

It is important to note that working with Twitter data in this way raises issues relating to public space and ethical research. While early social media research embraced discourse on platforms such as Twitter as “public” and therefore as not being subject to the need for informed consent (Marwick, 2013), more recent scholarship has problematized this notion, pointing out that, while services such as Twitter explicitly state that “posts that are public will be made available to third parties,” many users assume some level of privacy or that their consent will be sought before tweets are used in research (Williams et al., 2017, 1150). Researchers have dealt with this in different ways, from following a decision flowchart where factors such as whether the tweeter is a “public figure” or deals with sensitive content shape the approach taken (Williams et al., 2017) to avoiding quotation entirely and instead crafting “autoethnographic fictions” that recreate how tweets might have been rendered (Taylor and Breeze, 2020). In this text, I use a variety of strategies. I avoid direct quotation as much as possible, instead discussing emergent themes and shared features of the corpus. I also paraphrase tweet content and describe, rather than including screenshots of, images and memes. Where I do quote directly, I do so from content that has been favourited thousands of times as well as frequently retweeted and replied to; such content, in my view, has become public by virtue of its popularity and reach. In all cases, I anonymize content and do not refer to specific users by name.

The next section presents the results of this analysis, describing and discussing three key themes that emerged from the data as central to depictions of academic life during this period: disruption, care, and critique.

Performing the Academy on Academic Twitter

Disruption

To say that experiences of disruption, crisis, and chaos were a key feature of tweets about the pandemic risks banality. Notions of a break from normality and of dramatic differences from the expected or mundane were common across mainstream media and in political and policy discussion; indeed, as noted above, this disruption is what allows underlying assumptions to be identified. In this section, I thus explore not only tweet content concerning a sense of chaos and crisis but also what this tells us about “normal” life in the academy.

Particularly during the early stages of the pandemic in March, tweets frequently noted or alluded to the “unprecedented” nature of the current moment. This was, as one tweeter wrote, a “GLOBAL PANDEMIC” (caps in the original) and therefore an entirely new situation. Not only was this moment unprecedented but it was also “trying,” “tough,” or “difficult” in multiple ways. Themes of struggling and of the need to endure repeatedly emerged within the dataset, with, for instance, stories of students with close family members ill with COVID, the “emotional toll” of the situation, the challenge of dealing with constant uncertainty, or the sadness of defending one’s thesis at a time of social distancing. Tweeters spoke of struggling to concentrate, feeling despair or demoralization, or of mental health issues triggered by the crisis.

Such emotions and experiences were certainly not unique to academics. What was it, exactly, that academic tweeters described as being disrupted? Here key themes concerned the interruption of “normal” academic life through home-working, home-schooling, and care responsibilities, but also through the sudden removal of conferences and other face-to-face events such as defenses, the demand for online teaching, and ubiquitous Zoom meetings. Thus, on the one hand, some tweeters talked about the pleasures or affordances of quarantine and lockdown: one might use the time to finally finish the PhD thesis, or to catch up on reading. On the other hand, tweeters also asked for advice concerning disrupted fieldwork and the need to move to digital formats, made jokes about missing the lab, and worried about students who had “disappeared” since the move to online teaching. Much of this discussion was oriented to the need to the need to produce – particularly text, in the form of theses or articles, but also CVs, datasets, or good student evaluations. Concerns about an inability to concentrate, disrupted work days (for instance due to home-schooling), or a desire to “stay in my pyjamas all day,” “eat ice cream,” and “cry” all relate to an imagination of academic life as oriented to productivity. What was being disrupted by the pandemic, and the changed work practices it entailed, was the steady production of text and the capacity to “get more writing done.”

If the academy is enacted as oriented to productivity and the creation of text (in particular) within these tweets, it is also framed as being simultaneously solitary and social. It is this dynamic that lies behind the dual acknowledgment that much research (and more specifically, writing) is carried out alone (and that academics might therefore be somehow better prepared for the pandemic), but that it also involves important communal occasions (conferences, group meetings, and defenses). The pandemic was therefore described as simultaneously involving continuities with mundane academic life and as dramatically different from it. Tweeters joked about the PhD experience—limited human contact, the need for self-discipline, and digital communication—as being good preparation for lockdown, while also telling stories of efforts to replicate, via Zoom or other tools, social encounters such as discussions over coffee or conference attendance. The opportunity to participate in communal celebration—at the conclusion of a PhD or course, for instance—was particularly missed. Here, as in other aspects of the material, there was a sense that face-to-face copresence was something intrinsic to academic life.

This material from academic Twitter thus enacts academic life as productivity-oriented and as simultaneously solitary and social. It is these features that were disrupted so violently by the pandemic: much of the anxiety and struggles that are described within the data come from interruptions of productivity–through additional care responsibilities, anxiety, or extra work connected to the pandemic, for instance—and from enforced changes in rhythms of solitude and copresence. Merely describing these themes, however, gives little sense of how they were enacted within tweets, and in particular the degree to which the use of humor to tell stories of disruption is key to these accounts. The themes described above were articulated in the form of jokes, humorous stories, and remixed memes as much as through straightforwardly descriptive text. The challenges of working from home, for instance, might be conveyed by a story about a child running in and asking to take their clothes off in the middle of a lecture, while disrupted rhythms are implied by joking questions about what day it is. Importantly, ideas about (lost) productivity were also conveyed in this way. One tweeter wrote that while they were impressed by people who were managing to finish articles or develop analyses during lockdown, all they had managed was a small-scale study of the relation between pandemics and wine consumption; another noted that with classes being canceled and university buildings closed, they would be forced to actually work on their dissertation. Such humor is an important feature both of the platform generally (Philips and Milner, 2017) and of this particular dataset. In referencing challenges in a lighthearted way, it reinforces particular imaginations of academic life—that productivity and professional demeanor are important, for instance—whilst also gently subverting them (showing that ideals are rarely lived up to, or that procrastination is as much an issue as lack of time).

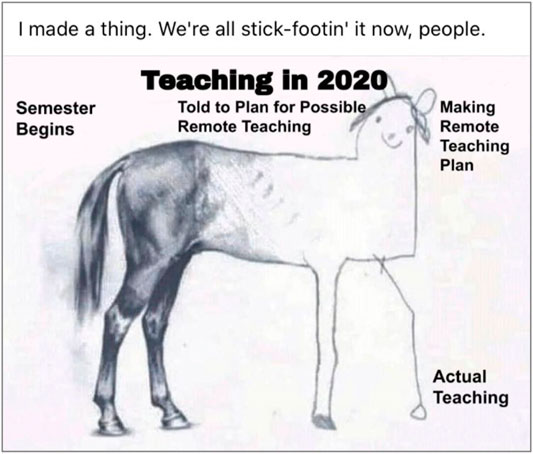

Performances of the contemporary academy are thus instantiated through a humorous tone that does complex work in both reinforcing and subverting ideals concerning what academic life should look like. This point can be further illustrated by one popular meme, an academia-oriented adaptation of the “unfinished horse drawing” meme5 which was circulated in mid-March. This appears in this dataset as a screengrab of another tweet, and has been favourited almost 1500 times, but the meme also traveled to other platforms, rapidly losing its original attribution. As shown in Figure 2, it uses the “unfinished horse drawing” image (used in multiple other memes) as a basis for a depiction of teaching in 2020 and, in particular, the move to online teaching. The online meme encyclopedia Know Your Meme notes that memes based on this image convey “the feeling of being rushed through a task and express the feeling that something's quality has diminished over time.” As such, its adaptation in the context of academic life and “pandemic pedagogy” communicates the disruption that has taken place and the drop in teaching quality that has occurred. It does so, however, in a manner that is humorous, highly visual, and self-mocking in the contrast between what is planned and what is actually carried out. The use of wry irony is typical of the humor that is deployed within discussion of pandemic disruption in this dataset, and of the ways in which even chaos and disruption are communicated through self-aware reflection.

FIGURE 2. Unfinished horse drawing “teaching in 2020” meme, captured from Twitter but widely circulated without attribution.

Care

If a first key theme within this material is of articulations of chaos and disruption that are frequently conveyed through humor and ironic self-reflection, a second relates to care and care practices. Tweets in this dataset are not only oriented to funny stories about disrupted working practices. Just as frequently, the content seeks to express compassion, care, and emotional honesty, and to offer (or request) support, empathy, or advice. Tweeters thus frame themselves as being part of particular groups (faculty, PhD students, supervisors, and academics generally), offering mutual support to those communities and giving guidance for supporting others outside of them.

Students are one frequent object of these care practices. Many tweeters expressed concern or gratitude for their students, or advised others about how to look out for them. One tweet, from Mrach favourited several thousand times, asked readers to “check in regularly on your PhD students … Many (perhaps most) live alone with no family nearby. We supervisors are the closest they have to a family.” Others focused more on junior students, advising others to drop penalties for late assignments, be cautious that using COVID-19 in teaching might be triggering for some individuals, or find ways to maintain relationships with students despite the move to remote teaching. Students were thus viewed as a key population which was suffering from the effects of the pandemic and which users of academic Twitter had the possibility to influence or support, whether by showing “kindness” or by trying to understand how to help individuals with little or no digital connectivity.

Tweeters also sought to care for “each other” and for “ourselves.” Articulations of care were directed within and between a community of academic Twitter users, with this community framed as being in need of compassion and care during the pandemic. Such articulations took different forms. Tweets might express offers of support (“we are here to support you”), discuss what it means in practice to “be kind to yourself,” remind people to check in on their friends and colleagues, ask for advice or for a “Zoom happy hour” because the tweeter was struggling, discuss the systems and structures in place at institutions to support well-being and mental resilience, or talk about how one was “staying sane” during such a difficult time (for instance, by painting or taking time off work). Such messages foregrounded the emotions tied to experiences of the pandemic, disclosing information about one’s own struggles and repeatedly emphasizing that it was normal to be finding the situation difficult. Tweeters thus both acknowledged negative emotions associated with the disruption described above, and affirmed that readers are “amazing and resilient” if they are managing to “survive.”

Care, in this material, is thus enacted as being vital to academia, but as often missing within it (cf. Cardozo, 2017; Ivancheva et al., 2019). The fact that so many of these tweets call for compassion and for care practices implies a backdrop where these are lacking or undervalued. Indeed, this is explicit within some tweets. One frequently favourited tweet discussed “the countless academics whose lack of compassion has consistently torn others down in the past few months,” and noted that this was more disappointing to them than their own, very natural, struggles. Similarly, the advice given—to check in on students or colleagues, to advise students that their mental health should be their priority, and to find things that help you “stay calm”—suggests that these practices are currently largely missing, and therefore need to be encouraged. Academic life is framed as requiring an influx of care through the mutual and self-supporting activities and practices the tweets promote.

Just as stories of disruption often came bundled with jokes and irony, expressions of care were instantiated through a distinctive affective repertoire. Here, memes and images were less important; instead, text (and sometimes Tweet threads, where several tweets are used to tell a longer story) was used to convey advice and support. The emotional tone of this content featured not only expressions of struggles or suffering and articulations of care and compassion in response to this but also gratitude, celebration, and motivational language. Thus, a thread of positivity ran through much of this content: tweeters wrote “props to other grads” who were similarly enduring difficult situations, that one needs to “survive to thrive” in “HARD” times, said “thank you” publically to colleagues or students, or gave “shout outs” to key individuals and groups. Similarly, academic Twitter was used as a key site to celebrate achievements (such as finishing or defending the PhD) or just enduring (even if one had not achieved anything, or were not pleased with your work, you should still consider yourself “excellent,” wrote one tweeter). As Veletsianos and others have suggested, then, disclosure is a central feature of how academic Twitter is used (Stewart, 2016; Veletsianos and Stewart, 2016; Jordan, 2020). In this material, tweeters rarely complained about their situations, although they might express that they were finding them hard in particular ways. Instead, they expressed gratitude, gave themselves and others advice, shared encouragement or motivation, and asked for support. I discuss the one key exception to this in the section below.

Critique

While tweeters in this material rarely discussed injustice or unfairness at a personal level,6 or complained about their individual situations (though they might disclose that they were finding these challenging), a thread of critique did run through the dataset. This critique was rarely aimed at individuals; instead, tweeters drew attention to inequity and injustice within academia, and criticized the institutions, structures, or systems seen as responsible for these. Academic Twitter, in this dataset, was thus not only concerned with personal struggles or with care practices within a community of academic Twitter users, but with wider questions of equity and with academia’s place within these.

The objects of this critique were institutions or groups such as “universities,” “faculty,” “this administration” (the Trump presidency in the United States), and “educators,” but also “us” and the “academic twittersphere.” Criticism or comment might also not be directed at any particular actor, but reflect on inequity without localizing blame to any specific site. The subject was, broadly, fairness or equity within the academy. Tweeters discussed, for instance, the different access students had to the technology that they now needed to access teaching, and their different home situations; the gendered challenges of working and teaching from home; cases where mainstream media focused on scientific work against COVID-19 by men, ignoring contributions by women; unfairness in how universities were treating their students and staff; and the ways in which casual or temporary academic staff were particularly badly affected by the situation. The discussion thus focused on the ways in which challenges (and opportunities) are differently experienced by those with different backgrounds and identities. As one tweeter wrote, “unearned privilege” was a central dynamic that structured how academics were able to deal with the pandemic and the demands it put on them.

This is well illustrated by a discussion that arose in response to a tweet by the celebrity scientist Neil deGrasse Tyson (Fahy, 2015). In a 1 April tweet that has been favourited 113,000 times (and which did not reference #AcademicTwitter or #AcademicChatter, and therefore does not form part of this dataset), deGrasse Tyson wrote that “When Isaac Newton stayed at home to avoid the 1665 plague, he discovered the laws of gravity, optics, and he invented calculus”: the point was, implicitly, that others stuck in lockdown situations might use the time productively. The tweet appears in this dataset as a screenshot alongside the comment that Newton did not have to deal with online teaching, home-schooling, shortages of essential supplies, and other aspects of daily life in the pandemic for many academics. By suggesting that “staying home” was straightforward, resulting in empty time that could be filled with scientific work, deGrasse Tyson was ignoring the diverse and often difficult situations that people found themselves in, and the degree to which having such empty time was a product of resources (family members who might care for one’s children, for instance, or a low teaching load). Other critique in this dataset was similarly focused on notions of productivity, which was seen as a key site where inequity became apparent. One tweeter wrote, addressing those anxious about their levels of productivity, that the pandemic “accentuates privileges” and that not everyone was able to be productive to the same extent, while another talked about the “duplicitous bullshit” of rewarding people who were managing to be particularly productive at a time of global crisis. Such comments relate to my earlier discussion of productivity—understood as the efficient and speedy creation of text or analysis—as central to enactments of the academy, but nuance and complicate this emphasis by pointing out that the ability to achieve this is in fact structured by unevenly shared privilege and opportunity.

By incorporating a thread of critique and attention to social justice, this Twitter material thus performs the academy as flawed not only through a deficit of care but also through its entanglements with and reflections of wider societal inequality. Particularly subject to criticism are university administrations and other institutional structures that demand productivity, a rapid switch to online teaching, or strict student attendance without acknowledging the barriers that some individuals and groups face in achieving this (from a lack of digital infrastructure to care responsibilities). While academics are themselves sometimes framed as complicit within this (hence the calls for “we,” the “twittersphere,” or “fellow researchers” to take heed of critique), the emphasis is on systemic factors that perpetuate historical privilege and on (flawed) university leadership. The academy is enacted as a place where an emphasis on productivity can all too easily be connected with a refusal to acknowledge unequal opportunities; this, in this material, leads to normative calls for institutions to act in more just ways, and for academics themselves—in the shape of the community that coalesces around #AcademicTwitter and #AcademicChatter—to be aware of injustice, show solidarity, and act in reflective and caring ways that seek to remedy or counter inequity.

Discussion

To summarize, analysis of this dataset from academic Twitter during the COVID-19 pandemic has led to the identification of themes of the disruption of academic work, frequently instantiated through ironic humor and memes; of care and care practices, generally discussed in a language of emotional honesty, positivity, and gratitude; and of critiques of injustice and inequity within academia, including (self-imposed) demands for productivity that ignore structural inequalities around who can achieve this. In this section, I want both to return to my research question—how was the contemporary academy performed on “academic Twitter” in the early months of the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic?—and to offer some more general reflections on the implications of these findings in the context of the literatures discussed at the start of the article.

How, then, was the academy performed within this material? As I have already started to sketch out, the version of academic life that is enacted within these Twitter discussions is one in which notions of “productivity” are contested but key. “Normal,” or perhaps rather “ideal,” academic life is one where it is possible to write, analyze, create datasets, read, or otherwise create knowledge products in effective and focused ways. Productivity is something that is constantly sought and that was disrupted by the pandemic. But this emphasis on production is neither taken for granted nor beyond criticism; indeed, a central focus of the critique that runs as a thread throughout the material is of the ability to produce being prioritized above well-being, mental health, or care for one’s community, and of unequal access to the possibility of such productivity. In this respect there are parallels with the literature that has analyzed the rise of “excellence” narratives within academia (Lund, 2015), discussed expectations of entrepreneurialism, self-reliance, and individual responsibility (Hakala, 2009; Loveday, 2017), or discussed current affective regimes of academic practice (Lorenz-Meyer, 2018). In such accounts, as in the material analyzed here, academics are expected to take personal responsibility for their careers, prioritizing the production of “excellent” research in order to ensure access to stable, long-term positions. Similarly, such work has also problematized ever-increasing demands to perform more and to perform better, and charted how these demands are being resisted or subverted by academics (Cannizzo, 2018; Rushforth et al., 2018). In this material, such resistance is done in part by an emphasis on care and care practices, an emphasis that has been hinted at in prior research (Cardozo, 2017; Heijstra et al., 2017; Ivancheva et al., 2019). By seeking to encourage care and “kindness,” these data enact the academy as fundamentally lacking in these things—a lack that is, at times, explicitly related to the emphasis on (personal) productivity. Similarly, the structural and institutional critique that appears on academic Twitter implies an academy that is unjust along multiple lines, and that demands intervention. The contemporary academy is performed as fundamentally flawed, both in its absence of equity and of care.

While this story of shortcoming and critique is certainly a key feature of this material, and one that is in line with other discussion of contemporary academia (Ball, 2015; Amsler and Shore, 2017), there are some complicating aspects. These emerge in particular from the ways in which these themes of productivity, deficiency, and critique are instantiated in the data, and the precise social media practices through which the academy is done. It matters, in other words, that the themes I have described are enacted through distinctive multimodal formats and through particular repertoires. It also matters that the academy is performed within stories of disruption as not only oriented to productivity but also involving rhythms of social interaction and solitude. Opportunities for celebration and togetherness are framed as key to academic life, and as deeply missed when the pandemic renders them impossible. The academy, then, is communal as much as being about writing and producing. Similarly, themes of productivity are often conveyed through ironic humor or memes (such as the unfinished horse drawing meme discussed above, or the joke about a study of pandemics and wine consumption) that both reference and distance oneself from the practices or priorities described. Efficient production of knowledge products might be an ideal, but it is one that is rarely achieved, and this lack of achievement is a key feature of self-aware humor. Wry joking becomes a way of enacting both what is demanded and resistance to it, in the form of highlighting the impossibility of these demands. More than this, however, such humor itself performs a shared community, one that participates in the production and circulation of particular forms of mimetic expression, sharing “in-jokes” and thereby crafting a shared identity. What is being done on academic Twitter, through these practices, is the enactment not only of a specific version of the academy but of a community that reflects upon this academy, at times critiques it, and mobilizes a specific repertoire and style within its communications (humor, but also emotional honesty, gratitude, and positivity). Academic Twitter, we might say, performs not only the academy but also a counterpublic (Graham and Smith, 2016) that sits both inside (in that it is a part of it) and outside (in that it offers distance and critique) of it.

While this study adds weight to previous work that has outlined an increasingly pressured and precarious academy, then, it also adds new dimensions to this by suggesting something of the style by which academics inhabit this space. On this platform, at least, humor, articulations of care, and the crafting of communities of solidarity were central to life and work in the academy during the pandemic. It is these dynamics which could be particularly valuable lines for future research, enabling investigations which seek to nuance accounts of experiences of precarity or injustice (for instance) through examination of the tools and practices through which these are rendered meaningful and bearable.

Conclusion

In examining how the contemporary academy was performed on “academic Twitter” in the early months of the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, I have argued that academic life is enacted in this material not only as oriented to productivity but also as involving rhythms of solitude and sociality, as lacking in care, and as often operating in unjust or unequal ways. At the same time, I have suggested that such a bald account misses much of the richness of the ways in which these performances are done. The use of humor, of registers of affect and solidarity, and of memes and other forms of multimodal expression all allow complex negotiations between acknowledgment of what one should be doing, and commentary on how things “really are.” Similarly, an emphasis on encouraging and enabling care practices and on social justice assists in the production of (a shared imagination of) an academic community that exists within academe, but that seeks to counter toxic features of it.

How does this relate to COVID-19 itself? Certainly, my account has richly illustrated the ways in which institutions such as academia have had their values laid bare by the pandemic, and how accounts of disruption can allow us to identify norms and practices that are being disrupted. While academic Twitter is not, of course, representative of all experiences of the academy, the analysis nonetheless provides us with insight into the nature of life and work in contemporary universities. It also shows us how one particular community used social media to discuss, reflect on, and share experiences of the pandemic. Academics—specifically those who use #AcademicTwitter and #AcademicChatter on Twitter—are certainly not alone in using the platform to build community, share and seek advice, and articulate struggles during ongoing experiences of COVID-19. I therefore hope that this analysis can contribute to studies of communication to and by other publics, and of the ways in which the content and form of social media communication are intertwined.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contribution

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

1See Veletsianos and Stewart, 2016 for one study of key themes within scholars’ “disclosures.”

2Twitter users “show their agreement with or appreciation for a tweet by giving it an endorsement and ‘favoriting’ it” (Graham and Smith, 2016, 437).

3See: https://digitalinspiration.com/product/twitter-archiver

4Technical issues meant that there was a break of 3 days in data collection, between April 1 and 4.

5See description on the Know Your Meme website: https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/unfinished-horse-drawing

6An observation which might in part be due to the methods used and in particular the decision to collect only tweets that had been favourited at least 25 times. More personal complaints may have resonated less widely and therefore achieved a lower level of virality.

References

Ackers, L. (2008). Internationalisation, Mobility and Metrics: A New Form of Indirect Discrimination?. Minerva 46 (4), 411–435. doi:10.1007/s11024-008-9110-2

Amsler, M., and Shore, C. (2017). Responsibilisation and Leadership in the Neoliberal University: A New Zealand Perspective. Discourse: Stud. Cult. Polit. Education 38 (1), 123–137. doi:10.1080/01596306.2015.1104857

Angervall, P., and Beach, D. (2018). The Exploitation of Academic Work: Women in Teaching at Swedish Universities. High Educ. Pol. 31 (1), 1–17. doi:10.1057/s41307-017-0041-0

Balaban, C. (2018). Mobility as Homelessness: The Uprooted Lives of Early Career Researchers. Learn. Teach. 11 (2), 30–50. doi:10.3167/latiss.2018.110203

Ball, S. J. (2015). Living the Neo-Liberal University. Eur. J. Education 50 (3), 258–261. doi:10.1111/ejed.12132

Bataille, P., Le Feuvre, N., and Kradolfer Morales, S. (2017). Should I Stay or Should I Go? The Effects of Precariousness on the Gendered Career Aspirations of Postdocs in Switzerland’. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 16. 313–331. doi:10.1177/1474904116673372

Berthoin Antal, A., and Rogge, J.-C. (2020). Does Academia Still Call? Experiences of Academics in Germany and the United States. Minerva 58 (2), 187–210. doi:10.1007/s11024-019-09391-4

Brantner, C., Lobinger, K., and Stehling, M. (2020). Memes against Sexism? A Multi-Method Analysis of the Feminist Protest Hashtag #distractinglysexy and its Resonance in the Mainstream News Media. Convergence 26 (3), 674–696. doi:10.1177/1354856519827804

Campbell, R. A. (2003). Preparing the Next Generation of Scientists. Soc. Stud. Sci. 33 (6), 897–927. doi:10.1177/0306312703336004

Cannizzo, F. (2018). ‘“You’ve Got to Love What You Do”: Academic Labour in a Culture of Authenticity’. Sociological Rev. 66 (1), 91–106. doi:10.1177/0038026116681439

Cardozo, K. M. (2017). Academic Labor: Who Cares?. Crit. Sociol. 43 (3), 405–428. doi:10.1177/0896920516641733

Courtois, A., and O’Keefe, T. (2015). Precarity in the Ivory Cage: Neoliberalism and Casualisation of Work in the Irish Higher Education Sector. J. Crit. Education Pol. Stud. 13 (1), 43–66.

Davies, S. R. (2020). Epistemic Living Spaces, International Mobility, and Local Variation in Scientific Practice. Minerva 58, 97–114. doi:10.1007/s11024-019-09387-0

Delfanti, A. (2020). The Financial Market of Ideas: A Theory of Academic Social Media. Soc. Stud. Sci. 51 (2). 259-276. doi:10.1177/0306312720966649

Dynel, M. (2021). COVID-19 Memes Going Viral: On the Multiple Multimodal Voices behind Face Masks. Discourse Soc. 32 (2), 175–195. doi:10.1177/0957926520970385

Fahy, D. (2015). The New Celebrity Scientists: Out of the Lab and into the Limelight. London: Rowman & Littlefield.

Felt, U. (2009). Knowing and Living in Academic Research: Convergences and Heterogeneity in Research Cultures in the European Context. (Prague: Institute of Sociology of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic).

Felt, U., and Fochler, M. (2012). Re-Ordering Epistemic Living Spaces: On the Tacit Governance Effects of the Public Communication of Science. In The Sciences’ Media Connection –Public Communication and its Repercussions, edited by S. Rödder, M. Franzen, and W. Peter, 133–154. (Springer Netherlands): Sociology of the Sciences Yearbook 28.

Fochler, M. (2016). Variants of Epistemic Capitalism. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 41 (5), 922–948. doi:10.1177/0162243916652224

Fowler, N., Lindahl, M., and Sköld, D. (2015). The Projectification of University Research. Int. J. Managing Projects Business 8 (1), 9–32. doi:10.1108/ijmpb-10-2013-0059

Graham, R., and Smith, S. (2016). The Content of Our #Characters. Sociol. Race Ethn. 2 (4), 433–449. doi:10.1177/2332649216639067

Gregory, K., and singh, S. S. (2018). Anger in Academic Twitter: Sharing, Caring, and Getting Mad Online. triple C 16 (1), 176–193. doi:10.31269/vol16iss1pp176-193

Hakala, J. (2009). The Future of the Academic Calling? Junior Researchers in the Entrepreneurial University. High Educ. 57 (2), 173–190. doi:10.1007/s10734-008-9140-6

Heijstra, T. M., Einarsdóttir, Þ., Pétursdóttir, G. M., and Steinþórsdóttir, F. S. (2017). Testing the Concept of Academic Housework in a European Setting: Part of Academic Career-Making or Gendered Barrier to the Top?. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 16. 200-214. doi:10.1177/1474904116668884

Hepp, A., Breiter, A., and Hasebrink, U. (2017). Communicative Figurations: Transforming Communications in Times of Deep Mediatization. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hine, C. (2015). Ethnography for the Internet: Embedded, Embodied and Everyday. New York, NY: London Bloomsbury Academic.

Ivancheva, M., Lynch, K., and Keating, K. (2019). Precarity, Gender and Care in the Neoliberal Academy. Gender, Work Organ. 26 (4), 448–462.

Jordan, K. (2020). Imagined Audiences, Acceptable Identity Fragments and Merging the Personal and Professional: How Academic Online Identity Is Expressed through Different Social Media Platforms. Learn. Media Tech. 45 (2), 165–178. doi:10.1080/17439884.2020.1707222

Kimmons, R., and Veletsianos, G. (2016). ‘Education Scholars’ Evolving Uses of Twitter as a Conference Backchannel and Social Commentary Platform: Twitter Backchannel Use’. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 47 (3), 445–464. doi:10.1111/bjet.12428

Leemann, R. J. (2010). Gender Inequalities in Transnational Academic Mobility and the Ideal Type of Academic Entrepreneur. Discourse: Stud. Cult. Polit. Education 31 (5), 605–625. doi:10.1080/01596306.2010.516942

Leigh Star, S., and Ruhleder, K. (1996). Steps toward an Ecology of Infrastructure: Design and Access for Large Information Spaces. Inf. Syst. Res. 7 (1), 25. doi:10.1287/isre.7.1.111

Linkova, M. (2013). Unable to Resist: Researchers’ Responses to Research Assessment in the Czech Republic. Hum. Aff. 24 (1), 78–88.

Lorenz-Meyer, D. (2018). The Academic Productivist Regime: Affective Dynamics in the Moral-Political Economy of Publishing. Sci. as Cult. 27 (2), 151–174. doi:10.1080/09505431.2018.1455821

Loveday, Vik. (2017). ‘“Luck, Chance, and Happenstance? Perceptions of Success and Failure Amongst Fixed-Term Academic Staff in UK Higher Education”: Luck, Chance, and Happenstance?. Br. J. Sociol. 69 (3). 758-775. doi:10.1111/1468-4446.12307

Lund, Rebecca. W. B. (2015). Doing the Ideal Academic - Gender, Excellence and Changing Academia. (Aalto, Finland): Aalto University.

Lupton, D., Mewburn, I., and Thomson, P. (2017). The Digital Academic: Critical Perspectives on Digital Technologies in Higher Education (Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, NY: Routledge).

Machin, D. (2013). What Is Multimodal Critical Discourse Studies?. Crit. Discourse Stud. 10 (4), 347–355. doi:10.1080/17405904.2013.813770

Markham, Annette. N. (2020). ‘Pattern Recognition: Using Rocks, Wind, Water, Anxiety, and Doom Scrolling in a Slow Apocalypse (To Learn More About Methods for Changing the World)'. Qualitative Inquiry, October, doi:10.1177/1077800420960191

Marwick, A. E., and boyd., d. (2011). I Tweet Honestly, I Tweet Passionately: Twitter Users, Context Collapse, and the Imagined Audience. New Media Soc. 13 (1). 114–133. doi:10.1177/1461444810365313

Marwick, A. (2013). “Ethnographic and Qualitative Research on Twitter,” in Twitter and Society. Editors K Weller, A Bruns, J Burgess, and M Mahrt (New York: Peter Lang), 109–22.

Milner, R. M. (2018). The World Made Meme: Public Conversations and Participatory Media. (Cambridge, Massachusetts London): The MIT Press

Phillips, W., and Milner, R. M. (2017). The Ambivalent Internet: Mischief, Oddity, and Antagonism Online. Cambridge, UK Malden, MA: Polity.

Reitz, T. (2017). Academic Hierarchies in Neo-Feudal Capitalism: How Status Competition Processes Trust and Facilitates the Appropriation of Knowledge. High Educ. 73 (6), 871–886. doi:10.1007/s10734-017-0115-3

Rivas, C. (2018). “Finding Themes in Qualitative Data,” in Researching Society and Culture: 431-453. Editor C. Seale (SAGE). doi:10.1332/policypress/9781447337683.003.0001

Roumbanis, L. (2019). Symbolic Violence in Academic Life: A Study on How Junior Scholars Are Educated in the Art of Getting Funded. Minerva 57 (2), 197–218. doi:10.1007/s11024-018-9364-2

Rushforth, A., Franssen, T., and de Rijcke, S. (2018). .Portfolios of Worth: Capitalizing on Basic and Clinical Problems in Biomedical Research Groups. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 44 (2). 209–236. doi:10.1177/0162243918786431

Schönbauer, S. M. (2020). ‘“From Bench to Stage” How Life Scientists’ Leisure Groups Build Collective Self-Care’. Sci. as Cult. January, 1–22.

Shapin, S. (2009). The Scientific Life: A Moral History of a Late Modern Vocation. London, United Kingdom: University of Chicago Press.

Sigl, L. (2016). On the Tacit Governance of Research by Uncertainty. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 41 (3), 347–374. doi:10.1177/0162243915599069

Slaughter, S., and Leslie, L. L. (1997). Academic Capitalism: Politics, Policies, and the. (Athens, Georgia): Entrepreneurial UniversityThe Johns Hopkins University Press.

Stewart, B. (2016). Collapsed Publics: Orality, Literacy, and Vulnerability in Academic Twitter. J. Appl. Soc. Theor. 1 (1), 61–86.

Taylor, Y., and Breeze, M. (2020). All Imposters in the University? Striking (Out) Claims on Academic Twitter. Women's Stud. Int. Forum 81 : 102367. doi:10.1016/j.wsif.2020.102367

Veletsianos, G. (2016). Social Media in Academia: Networked Scholars. New York: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315742298

Veletsianos, G., and Kimmons, R. (2012). Networked Participatory Scholarship: Emergent Techno-Cultural Pressures toward Open and Digital Scholarship in Online Networks. Comput. Education 58 (2), 766–774. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2011.10.001

Veletsianos, G., and Stewart, B. (2016). Discreet Openness: Scholars' Selective and Intentional Self-Disclosures Online. Soc. Media + Soc. 2 (3), 205630511666422. doi:10.1177/2056305116664222

Watermeyer, R., and Olssen, M. (2016). 'Excellence' and Exclusion: The Individual Costs of Institutional Competitiveness. Minerva 54 (2), 201–218. doi:10.1007/s11024-016-9298-5

Williams, M. L., Burnap, P., and Sloan, L. (2017). Towards an Ethical Framework for Publishing Twitter Data in Social Research: Taking into Account Users' Views, Online Context and Algorithmic Estimation. Sociology 51 (6), 1149–1168. doi:10.1177/0038038517708140

Winkler, I. (2013). Moments of Identity Formation and Reformation: A Day in the Working Life of an Academic. J. Org Ethnography 2 (2), 191–209. doi:10.1108/joe-11-2011-0001

Ylijoki, O.-H. (2014). Conquered by Project Time? Conflicting Temporalities in University Research. Universities in the Flux of Time. Abingdon, United Kingdom: Routledge, 108–21.

Keywords: social media, Twitter, academia, COVID-19, multimodality

Citation: Davies SR (2021) Chaos, Care, and Critique: Performing the Contemporary Academy During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Commun. 6:657823. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2021.657823

Received: 24 January 2021; Accepted: 13 April 2021;

Published: 30 April 2021.

Edited by:

Dara M. Wald, Iowa State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Kate Maddalena, University of Toronto Mississauga, CanadaBonnie Stewart, University of Windsor, Canada

Copyright © 2021 Davies. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sarah R. Davies, c2FyYWguZGF2aWVzQHVuaXZpZS5hYy5hdA==

Sarah R. Davies

Sarah R. Davies