- Department of English Studies, University of Graz, Graz, Austria

It is a well-known fact that the United States has a very high prison population compared to other countries, and that it is particularly the private prison industry that has been thriving. This industry is based on a for-profit ideology that aims to save money by cutting costs wherever possible, and that, based on their profit-orientation, has no interest in rehabilitating offenders, since they make money with every incarcerated person. This paper investigates these issues from a linguistic perspective and takes a corpus of texts collected from the websites of the two largest private prison corporations in the United States (CoreCivic and The GEO Group) as a starting point for a corpus-assisted discourse analysis. The corpus comprises a total of 25,386 words and the analyses reveal that while both companies discursively background issues of violence, recidivism, and costs, they place a focus on the safety and security of their facilities and on their reentry programs for inmates. Thus, it is argued that the investigated corporations shift the discursive focus away from a negative discourse centering on violence and recidivism to a positive discourse centering on reentry and safety, which actively counters the findings that several researchers and journalists alike have revealed.

Introduction

Prisons as institutions of punishment have been known in Europe since the 12th century, and were introduced in the United States in the late 18th century (McShane, 2008, pp. 8–9). Their functions have been manifold, and range from reformation, incapacitation, retribution, and deterrence to more latent functions such as, among others, politicization, self-enhancement, provision of jobs, and slave labor (Reasons & Kaplan, 1975). Since the 1960s, the United States has led the development of prison privatization, closely followed by Australia, and, within Europe, the United Kingdom. The ideology of marketization is manifested in thinking that includes “privatized ownership and management, private sector design, finance, construction, and management of whole institutions, outsourcing or contracting out of core or ancillary functions, and competition or market testing processes in which public and private service providers are compared” (Ludlow, 2017, p. 914). While public maintenance of prisons has been associated with consistency and improved standards, the earliest private prisons in the United States were known for their exploitation and brutality (Hallett, 2006; Ryan & Ward, 1989 in; Ludlow, 2017, p. 915). While evidence about the effectiveness and efficiency of the private sector remains scarce (Ludlow, 2017), private prison organizations justify their existence with arguments of cost-effectiveness, increased safety and security, and reduced recidivism rates (e.g., pond cummings and Lamparello, 2016). The present paper focuses on the public and private discourses (i.e., the discourse that the companies oversee, such as the discourse on their own websites) of the two largest private prison corporations in the United States, namely CoreCivic and The GEO Group, Inc. (GEO). Before moving on to a review of the literature on prison privatization in the United States, CoreCivic and The GEO Group will be introduced.

CoreCivic

According to the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) (2019a), CoreCivic, founded in 1983, is the largest private prison corporation in the world, and they operate more than 100 correctional, detention, and reentry facilities in the United States. It is also claimed that CoreCivic is “the largest owner of private real estate used by the United States government” (AFCS, 2019a; online). CoreCivic manages not only prisons, many of which have developed a bad reputation, but also owns immigrant detention centers and reentry facilities. The “zero-tolerance” immigration policy adopted under the Trump administration (see, e.g., Kandel, 2018) has provided a secure and robust sales environment for CoreCivic. Both the immigrant detention centers and reentry facilities, too, have been accused of abuse, neglect, and mismanagement. It is important to note that CoreCivic now charges prisoners for many reentry services which used to be provided by non-profit organizations (AFSC, 2019a).

The GEO Group, Inc

The GEO Group, Inc. (GEO) was founded in 1984, a year after CoreCivic (The GEO Group, 2021). AFSC (2019b, online) refers to The GEO Group as “the world’s second largest private prison company”, which manages both prisons and immigrant detention centers. Similar to CoreCivic, The GEO Group has recorded increases in profits and revenue, and has profited from the zero-tolerance immigration policy introduced under President Trump. The GEO Group’s prisons and detention centers have developed a bad reputation in recent years; in particular, their youth detention centers have come under scrutiny after “systematic abuse, torture and mistreatment of incarcerated youth” (AFSC, 2019b, online) had been reported.

Literature Review: Private Prisons in the United States

In the United States, private prisons first emerged in the late 18th century, when Louisiana privatized its prison called “The Walls” (Angola Museum, 2019) in 1844 (Bauer, 2018). After the Civil War, the use of private prisons expanded rapidly (Bauer, 2018), and it was in the late 1980s that modern private prisons developed (Burkhardt, 2017; Ortiz & Jackey, 2019). Nowadays in the United States, two private prison corporations own the largest share of private prisons: The Corrections Corporation of America, known as CoreCivic, and The GEO Group, formerly known as Wackenhut Correction Corporation, WCC, which were introduced above. In 2010, these two corporations together “generated more than $2.9 billion in revenue […] with revenues ever increasing through 2019” (Craig and pond cummings, 2020, p. 268). Gotsch and Basti (2018, p. 12) state that CoreCivic owns more than 70 facilities, including prisons, immigrant detention, and reentry centers, totaling approximately 80,000 beds around the United States. CoreCivic is reported to have increased its profits by 500% within a span of only 20 years (pond cummings and Lamparello, 2016, p. 425). As of December 2016, more than 128,300 people were incarcerated in private prisons (Gaes, 2019, p. 270).

In recent years, however, a growing opposition towards private prisons (Craig and pond cummings, 2020) has been fighting for their abolishment. Enns and Ramirez (2018) cite studies that show how general criminal justice policies do not reflect public opinion (e.g., Beckett, 1997; Smith, 2004; Tonry, 2009; and; Zimring & Johnson, 2006). Their own study reveals that the public opinion on privatization of prisons is divided, yet a majority does not support this process, possibly due to the immoral incentives that Craig and pond cummings (2020, p. 264) hint at: “private prison corporations are driven by perverse and immoral incentives whereby an increase in crime and an increase in the number of human beings placed into America’s brutal prisons is good business news for that industry.” Thus, the question arises as to how this system works, which arguments are put forth for the continued reliance on private prisons, and at what and whose costs the corporations generate the reported high profits.

Research on the Conditions in Private Prisons

pond cummings and Lamparello, 2016 report that the living environments “deprive many inmates of basic needs”, many are “severely underfed” and have to live in “filthy quarters without working lights or toilets” (p. 427). Bauer (2016; 2018), who has worked undercover as a guard for 4 months in a private prison, has also disclosed horrible conditions. For instance, he reports that because a prisoner was refused any medical attendance, he lost his legs to gangrene. Further, guards were paid only $9 per hour and the prisons were very much understaffed: at times, only 24 guards were on duty but were responsible for more than 1,500 inmates. Thus, he concludes, it is unsurprising that private prisons have become rather violent. pond cummings and Lamparello (2016, p. 426), for example, report assault rates in private prisons as being between three and five times higher compared to public prisons. Another factor contributing to the increasing violence is the limited training that correctional officers receive: Bauer (2018) recalls being told not to intervene if a fight breaks out. Williams (2018, online) adds that “a mentally ill man on suicide watch hanged himself, gang members were allowed to beat other prisoners, and those whose cries for medical attention were ignored resorted to setting fires in their cells”—this is just an illustration of one experience, but stories and reports of violence and abuse in private prisons abound (see, e.g., Burnett, 2012; Esquivel, 2017; Pauly, 2017; Woodman, 2017; Wofford, 2014).

In line with the observations and arguments by (Bauer, 2018) and (Williams, 2018), Burkhardt, (2017, p. 26) notes that correctional officers in the private prison sector describe their job as ““the toughest beat” in law enforcement” (Lambert, Hogan, Griffin & Kelley, 2015; Page, 2011). Considering the minimum payment, harsh conditions and understaffed facilities, the staff turnover has been reported to be rather high (Craig and pond cummings, 2020, pp. 271–272). Therefore, it seems as if private prisons pose a danger to both staff and inmates. As Burkhardt, (2017, p. 31) points out, for prisoners an assignment to a private prison brings risks: of unfair discipline (Mukherjee, 2014), inadequate health care (Makarios & Maahs, 2012; Wessler, 2016), and idleness (Makarios & Maahs, 2012). For workers, employment in a private prison likely brings a low salary and an unpredictable future (Stephan, 2008; Bauer, 2016).

Arguments for and Against the Maintenance of Private Prisons

These findings raise the question as to how private prisons can still exist. First and foremost, pond cummings and Lamparello (2016, p. 420) argue that the main reasons put forth by the corporations to keep private prisons in business are cost-effectiveness, increased safety, and the humane treatment of inmates. However, (Simmons, 2013, online), for example, has shown that even though private prisons might be less expensive in the short term, they are likely to be more expensive in the long run (see also Austin & Coventry, 2001; Cornell University, 2020; Mamun, Li, Horn, and Chermak, 2020; McDonald, Fournier, Russell-Einhorn & Crawford, 1998; Pratt & Maahs, 1999). More importantly, though, the short-term cost-effectiveness seems to come at a high cost particularly for inmates, who are deprived of health care (Bauer, 2018), have fewer educational opportunities (Craig and pond cummings, 2020, p. 271; Bauer, 2018), and often earn only a few pennies an hour (Craig and pond cummings, 2020) or $1 a day (Gotsch & Basti, 2018, p. 9). Another important factor contributing to the perceived short-term cost-effectiveness is that, as Burkhardt, (2017, p. 24) argues, “critics have long suspected that private prison firms skim the best inmates with lowest needs in an attempt to minimize costs.” As his study confirms, the prison population of private prisons does not mirror the prison population of public prisons: they apparently favor younger inmates with fewer medical needs (p. 26) and “house [] a relatively large number of inmates serving less than 1-year sentences for federal authorities and […] employ [] female and black or Hispanic security staff” (p. 29) at a higher rate than their public counterparts. This confirms much of (Austin and Coventry, 2001) as well as (Gruberg, 2015) findings.

Furthermore, the argument of increased safety seems to be countered by research that indicates higher rates of violence in private compared to public prisons. While a small number of studies report that conditions in private prisons are of a higher quality compared to public ones, for example in terms of cleanliness, staff competence, and counsellor services (see, e.g., Hatry, Brounstein & Levinson, 1993; Logan, 1991; Lukemeyer and McCorcle, 2006; Thomas & Logan, 1993), Camp and Gaes (2002) hint at “systematic problems in maintaining secure facilities” (p. 444) by pointing at escape rates and drug usage. More recently, Buchholz (2021) presents statistics that show both higher inmate-on-inmate and inmate-on-staff assault in private prisons, in addition to a higher number of weapons, tobacco and drugs detected inside the private penitentiaries (see also Lopez, 2016). As mentioned above, this is also likely due to the fact that correctional officers do not receive adequate education and little to no arms for self-defense or the control of prisoners (Bauer, 2018). To illustrate, one institution in Idaho has become known as the “gladiator school” among inmates (pond cummings and Lamparello, 2016, p. 424).

The humane treatment of inmates, which is another common argument for the existence of private prisons, has also been questioned. Craig and pond cummings (2020) go as far as comparing the conditions which inmates of private prisons find themselves in to a modern form of slavery. They argue that the new name of “convict leasing” (p. 305) is just a euphemism for slavery and that it can be regarded as an indirect form of slavery that private prison corporations are paid for each incarcerated person as “governments contractually owe private prisons a certain fee per bed or prisoner” (pond cummings and Lamparello, 2016, p. 416). However, it is a more direct form of slavery when prisoners are leased to other companies for work, while the prison corporations keep most of the money the inmates earn (pond cummings and Lamparello, 2016, p. 419). An additional source of money for the corporations is that they overcharge inmates for video and telephone services (pond cummings and Lamparello, 2016, p. 425). In sum, Craig and pond cummings (2020) point out that the existence of private prisons is not only morally wrong (p. 265), but also “violates all three principles of the United States Department of Justice’s Office for Access to Justice: (namely) ensuring fairness, increasing efficiency, and promoting accessibility” (p. 274).

Another issue that has been raised in the literature is the recidivism crisis in the United States. For example, Durose, Cooper and Snyder (2014) report that 68% of released inmates reoffend after 3 years, and even more (76.6%) do so after 5 years (see also Katsiyannis et al., 2018). Mamun et al. (2020) report on studies that demonstrate that recidivism rates in private prisons are between 16.7% (Spivak & Sharp, 2008) and 22% (Duwe & Clark, 2013) higher when compared to public prisons. Powers, Kaukinen and Jeanis (2017) further present a statistically significant difference in recidivism rates for prisoners released from private prisons (68% compared to 45%). However, the impact of privatization on recidivism has been contested (e.g., Gaes, 2019). A problem connected to the quantification of recidivism is that its effects only appear up to 5 years later; therefore, it does not appear in statistics and thus benefits the statistics of private prison firms (Powers et al., 2017). Another aspect which private prison companies profit from is the overcrowding of prisons (Austin & Coventry, 2001), which “provides incentives for states to contract with private operators” (Price, Carrizales & Schwester, 2009, p. 82). Private prison corporations are thus found to “aggressively lobby for harsher prison sentences such as mandatory-minimums1 and three-strikes laws2; for legislation that creates new crimes requiring incarceration, such as criminalization of illegal immigration or active detention of schoolchildren; and against decriminalization” (Craig and pond cummings, 2020, pp. 267–8). Indeed, Craig and pond cummings (2020, p. 269) note that CoreCivic spent more than $3 million in 2005 and still more than $1.2 million in 2019 on federal lobbying, even though ever since 2012, the number of people incarcerated has been shrinking for the first time in a long time (Mamun et al., 2020, p. 4508). The reason that private prisons are still well off despite the shrinking numbers of incarcerated people is the “occupancy guarantee clause” that allows private prisons to “get first priority to house inmates, and possibly even get paid for empty cells” (Mamun et al., 2020, p. 4501). This likely explains why in the 16 years between 2000 and 2016, the private prison population was observed to grow “five times faster than the total prison population” (Gotsch & Basti, 2018, in; Mamun et al., 2020, p. 4500).

Given the amounts of money at stake, it is not surprising that corrupt practices are revealed from time to time, with the so-called Kids for Cash scandal likely being the most well-known example: in this particular case, two Pennsylvania judges were found to sentence juveniles to detention at much higher rates than the state average and were then paid kickbacks of $2.6 million (Craig and pond cummings, 2020, p. 270). A quote from Bauer’s (2018, online) article will close this section and provide the starting point for the analysis that is to follow in the remainder of this paper:

In May 2017, I bought a single share in the company [CoreCivic] in order to attend their annual shareholder meeting. As I sat and watched Terrell Don Hutto3 and other corporate executives discuss how their company’s objective was to “serve the public good”, I wondered how many times such meetings had been held throughout American history. How many times have men, be they private prison executives or convict lessees, gotten together to perform this ritual? They sit in company headquarters or legislative offices, far from their prisons or labor camps, and craft stories that soothe their consciences. They convince themselves, with remarkable ease, that they are in the business of punishment because it makes the world better, not because it makes them rich.

Data, Methodology and Research Questions

The data for this work is drawn from the websites of CoreCivic and The GEO Group. All texts available on their websites (as of January 2021) were copied and pasted and then cleaned and prepared for the analysis with the corpus program AntConc (Anthony, 2020). In total, the corpus of texts collected from both websites comprises 25,386 tokens; 10,032 of which belong to the CoreCivic sub-corpus, and 15,354 to the GEO sub-corpus.

Discourse Analysis, Critical Discourse Analysis and Corpus-Assisted Discourse Analysis

Johnstone (2018) explains that the starting point for a discourse analysis (DA) is a text on the basis of which an understanding for the context is developed. The text is therefore regarded as the product of discourse (Widdowson, 2004, p. 8), and discourse is seen as a form of social practice that is both socially constitutive and socially conditioned (Wodak, 2002). An important issue central to DA is that of representation. Fairclough (2003, p. 26) states that “representation is clearly a discoursal matter” and different discourses “may represent the same area of the world from different perspectives or positions.” In essence, it is argued that the way certain issues are portrayed are reflective of underlying ideologies, which Fairclough (2003, p. 9) states to be “representations of aspects of the world which can be shown to contribute to establishing, maintaining and changing social relations of power, domination and exploitation.” The representation of identities and self-images (Fairclough, 2003, p. 183) is in so far relevant to the present study as that, as marketing devices (e.g., Goddard, 1998), the websites of private prison corporations must present the corporations’ perspectives and positions within the larger discourse of crime, punishment, and justice, which has not always shed a favorable light onto these institutions. Thus, it is argued, they need to counter the representations of their institutions created by the media and scientific studies to keep their corporations in business. As highlighted in the quote by Bauer (2018, online) above, the corporations are trying to “convince themselves that they are in the business of punishment because it makes the world better, not because it makes them rich”, which reflects an underlying tension between the private and public discourses the prison corporations are engaged in.

In the context of political issues, methods of critical discourse analysis (CDA), which aim at uncovering hidden ideological positions, are useful, as CDA is “particularly concerned with (and concerned about) the use (and abuse) of language for the exercise of sociopolitical power” (Widdowson, 2007, p. 70). According to (Flowerdew, 2008, p. 196), “discursive situations where dominance and inequality are to the fore” are at the center of CDA. Such dominance and inequality are enacted and reproduced through texts and discourse, and, as argued in this paper, enacted in the self-presentation of the investigated private prison corporations.

The use of corpora to assist DA has become rather popular, although the number of studies making joint use of corpus linguistic (CL) tools and methods of (C) DA remains small (Baker et al., 2008). (Partington, 2003, p. 12) points out that at the simplest level, corpus technology helps find other examples of a phenomenon one has already noted. At the other extreme, it reveals patterns of use previously unthought of. In between, it can reinforce, refute or revise a researcher’s intuition and show why and how much their suspicions were grounded.

At the center of a corpus analysis is a large body of naturally occurring texts (Baker, 2006), which is then analyzed with a corpus program “in order to understand real linguistic usage” (Matthews & Kotzee, 2019, p.5). Importantly, as Matthews and Kotzee (2019) point out, the use of corpus tools in DA can shed light onto hidden phenomena (see also, e.g., Partington, 2008). This is achieved through the analysis of keywords, concordances and collocations, which can reveal discursive strategies and topics prevalent in the investigated discourse that are difficult to detect by investigating the data manually. Through the analysis of collocations and concordances, it is also possible to detect semantic prosody present in the discourse. In fact, (Griebel and Vollmann, 2019, pp. 576–7), state that CL methods “are well suited to detect quantitative regularities at the linguistic surface that give hints to ideologies found within a society that may stay unrecognized in purely qualitative research.” Many researchers have found corpus-assisted methods useful in DA (see, e.g. Baker, Gabrielatos, Khosravinik, Kryzanowski, McEnery & Wodak, 2008; Gabrielatos & Baker, 2008; Salama, 2011). In particular, the benefit of complementing a DA with a corpus or vice versa lies in the conjunction of quantitative and qualitative methods (Knoblock, 2020). A meta-analysis by Nartey and Mwinlaaru (2019) has shown that corpus-assisted approaches are frequently used in linguistics, and yet they identify a lack of such research “in the allied field of critical genre analysis and forensic contexts as well (as) those of contrastive/intercultural rhetoric, narrative inquiry/analysis, mediated discourse analysis, and conversation analysis have hardly been engaged” (p. 19, my emphasis). Thus, the present paper aims at contributing to the extant literature in the area of corpus-assisted discourse analysis in forensic contexts (e.g., Coulthard, 1994; Kredens, 2002; Cotterill, 2003; Heffer, 2005; Gruber, 2014; Felton Rosulek, 2015; Gales, 2015; Tkacuková, 2015; Wright, 2021), and it is also the first one, to my knowledge, to address the language of private prison corporations in the United States.

Methodology

In a first step, keyword and frequency lists were generated. The frequency lists of content words give indications as to the “aboutness” of the corpora (Baker, 2006). First, the corpora were tagged with the Stanford POS tagger (Stanford Tagger, 2003) and then checked manually for accuracy. Afterwards, the frequency lists were created. Secondly, the keyness of words (usually content words), which refers to how salient a word is in a corpus in comparison to another corpus (Baker, 2006; Matthews and Kotzee, 2019), was invesigated. Keywords, thus, can be argued to “reflect the main concepts, topics or themes in a text or corpus” (Wright, 2021, Chapter 37). For the purpose of the keyword analysis, the CoreCivic and GEO corpora were compared with the open American National Corpus (oANC), a general language corpus. The oANC covers American English data from a variety of genres, including web blogs, web pages, chats, email, and social media platform such as Twitter. Conceived in 2005 by the Linguistic Data Consortium (LDC), the oANC contains, at present, 15 million words with the ultimate aim of comprising 100 million words annotated for various linguistic phenomena once it is completed (ANC, 2015, online). Since the data used in the present study is drawn from American websites, the oANC was deemed appropriate for comparisons.

Keyword Analysis: A Bottom-Up Exploration

The keyword analysis presents a bottom-up approach to explore salient themes in the dataset. After identifying the most common keywords in both corpora, these keywords are then investigated in their contexts through collocation and concordance analyses to shed light onto the self-presentation and central concerns of the companies. The keyness score of a word reflects the saliency of the respective term, i.e. “the higher the (keyness) score, the stronger the keyness of that word” (Baker, 2013, p. 127). To determine the keyness of words, the log likelihood statistic was used, as this measure is useful in “overcom (ing) the issue of skewness” that is common in linguistic data (Baker, 2006, p. 126). Afterwards, the keywords were investigated in their contexts through collocation and concordance analyses. Collocations refer to “the characteristic co-occurrence of lexical patterns involving two or more words within a certain (limited) distance of one another” (Weisser, 2016, p. 272)4 and concordances refer to the listing of words within their contexts (KWIC, keywords in context) (Weisser, 2016). The generation of a concordance list, thus, allows words to be viewed in their contexts to determine, for example, their semantic prosody and connotations. Predication and modification of nouns and verbs will be investigated to determine the semantic prosodies and connotations of words identified in the keyword analysis. Semantic prosodies, or discourse prosodies, which is related to “the relationship of a word to speakers and hearers” (Baker, 2006, p. 87), and provides insights into evaluations and attitudes underlying the investigated discourse (see also, e.g., Hunston, 2007).

Top-Down Analysis of Central Issues

In addition to the bottom-up approach, a top-down approach was taken. That is, based on previous research, three main areas of interest and potential conflict between research findings and the representation of the self-image of the investigated companies emerged. First of all, as mentioned above, the main argument put forth by private prison corporations such as CoreCivic and The GEO Group is that they are cost-effective. However, this has continuously been refuted by researchers (e.g., Mamun et al., 2020). Therefore, the aspect of costs and cost-effectiveness as presented on the respective companies’ websites will be looked at in more detail. Secondly, research has identified safety issues in private prisons for both inmates and employees (e.g., Camp & Gaes, 2002) while the corporations maintain that private incarceration is safer than public incarceration. Thus, the issue of safety was marked as another interesting aspect deserving of further investigation. Thirdly, while private prison corporations argue that they provide reentry services to reduce recidivism, researchers have claimed that the corporations inherently do not show an interest in preventing recidivism, since they make profit off every single prisoner (e.g., pond cummings and Lamparello, 2016). Petersilia (2003) has marked the reintegration of prisoners into society as being a profound challenge in (America, and Thompkins, 2010) even describes the emerging apparatus of re-entry institutions and criminal justice agencies as “Prisoner Reentry Industry.” Further, the Second Chance Act was passed in 2007, which focuses on the improvement of reentering programs, after such programs had been abandoned after the 1970s (Ortiz & Jackey, 2019, p. 485). Recidivism and reentry were therefore chosen as the third area for investigation in this paper. Because researchers and corporations come to differing, if not opposite, conclusions in terms of these three issues, it is argued that the corporations have to do much identity work in these respects, which is why the following research questions were formulated:

1) Which topics are saliently presented on the CoreCivic and the GEO Group websites and are central to their identity presentation?

2) How is cost-effectiveness represented on the CoreCivic and GEO Group websites?

3) How are safety issues and violence represented on the CoreCivic and GEO Group websites?

4) How are recidivism and reentry represented on the CoreCivic and GEO Group websites?

Analysis and Results

The following section first looks at the findings for the CoreCivic Corpus and then proceeds to outline the findings for the GEO Group Corpus, before moving on to a comparison between the two corpora, and a discussion of the results.

Bottom-Up Exploration of CoreCivic’s Self-Presentation and Self-Image

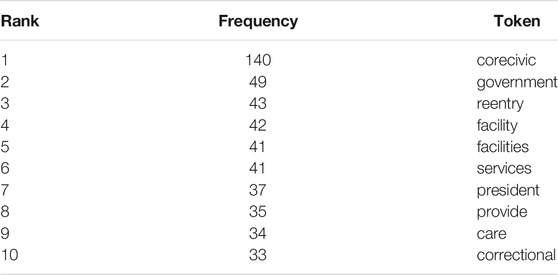

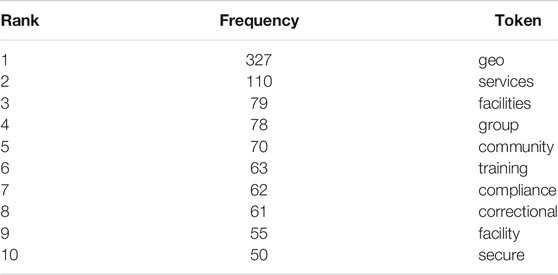

Firstly, a word frequency list of all content words in the CoreCivic corpus was generated (see Table 1). Table 1 displays the ten most common content words in the corpus, thereby providing more insight into the “aboutness” of the texts (Baker, 2006). With 140 occurrences, the by far most common word in the CoreCivic corpus is the proper noun and company name “CoreCivic.”

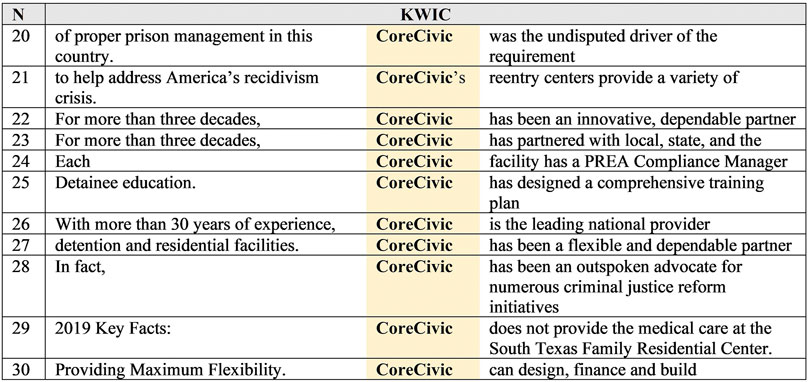

In terms of self-presentation, it is vital to understand how the noun CoreCivic is used on the website. For that purpose, concordance lines were created and some selected examples are reproduced in Figure 1 (examples were chosen to be representative of the corpus, as a reproduction of all examples is prohibited by spatial restrictions). As shown in the concordance lines, CoreCivic is presented as an active agent, and the language used on the website accredits the company with positive qualities such as dependability and innovation. The only exception in Figure 1 is line 29, which states a negative fact about CoreCivic. To arrive at a better understanding of what is happening in this case, one must investigate the full context of the sentence: this specific sentence is taken from a statement made about the passing away of a child at one of CoreCivic’s facilities (Mariee Juares, see, e.g., Silva, 2019), and the statement points out that the medical care was not provided by CoreCivic but by another organization, thereby negating and refuting the involvement of CoreCivic in the death of the child.

Next, consider the use of “government.” A collocation analysis shows that “partner” and “partners” appears as the R1 terms in 28.6% of all instances of “government”, and in 50% of these cases, the L1 word is the pronoun “our”. This makes the phrase “our government partner(s)” a prevalent one in the corpus. By referring to the government as “partners” in sentences such as “providing maximum flexibility for government partners”, “meet the needs of other government partners”, and “provide a broad range of solutions to government partners”, CoreCivic indicates that they are indeed serving the government, but they also view themselves as being in a powerful position with an equal standing.

Other frequent words of interest are “services” and “care.” A collocation analysis indicates that 41% of L1 collocates describe the services offered by the company in more detail through descriptive adjectives such as “religious,” “rehabilitate”, “psychological”, “orthodontic”, “educational”, “correctional” and “reentry”, and highlight that the services are of high quality. Similarly, 82% of instances of the verb “care” collocate with the L1 words “health”, “our”, “acute” and “dental”, thereby describing the types of provided care in more detail. The use of the possessive determiner “our” is of particular interest as it projects the social actor (i.e. CoreCivic) directly into the discourse (e.g., Fairclough, 2003). Possessive pronouns or determiners such as “our” indicate, as the name suggests, possession, or whole-part-relations (see, e.g., Blodgett & Schneider, 2018), as well as entitlement while simultaneously conveying a sense of belonging and ownership. Therefore, the construction “our” + NP indicates ownership of the implicit narrator/author of the text over what the NP denotes, while at the same time being important in the representation of a unitary identity of the company.

The noun “care” has a positive connotation in that it implies “painstaking or watchful interest”, “maintenance,” “charge”, or “supervision” (Merriam-Webster, 2021), while simultaneously implying a sense of superiority of the one taking care over the one who is being taken care of. Thus, when the possessive determiner “our” occurs together with “care”, as in the sentences “those entrusted in our care”, “inmates in our care”, and “ensure the safety over everyone in our care”, a sense of superiority and power of CoreCivic is visible. Together with regarding themselves as partners equal in position to the government, as being in charge of the inmates, and by describing the range of services offered by their facilities as professional and of high value and quality, CoreCivic’s self-presentation is entirely positive and yet authoritative and powerful.

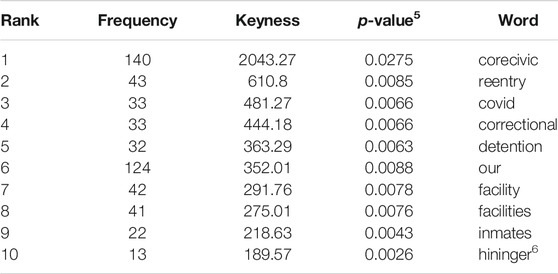

CoreCivic: Keywords in the Self-Presentation of the Company

The most common keyword in the list (see Table 2) is the name of the company itself, as discussed above. In the self-image of the company, “reentry” (see 4.1.2 for more detailed discussion), “our”, “facility”, and “facilities”, seem to be of key importance.

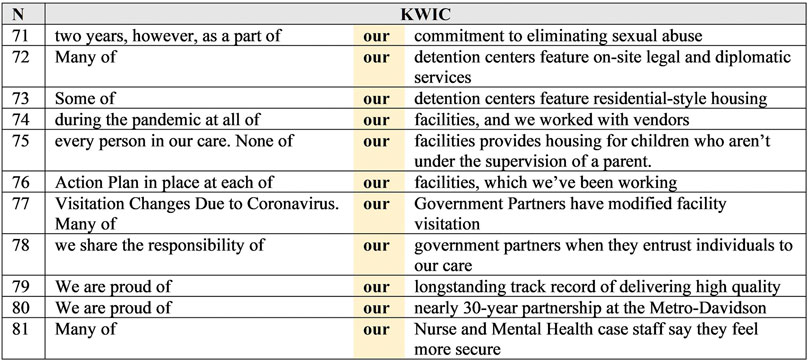

Even though all keywords would warrant further investigation, space restrictions prohibit detailed discussions of each of them. In light of the first research question, the keywords “our”, “facility” and “facilities” will be the focus of the subsequent analysis. Figure 2 shows selected concordance lines of “our.”

As discussed above, “our” conveys a sense of ownership, entitlement, and belonging. Additionally, the use of we-words such as “our” can be an indicator of perceived power and high status (Pennebaker, 2011, p. 171). This interpretation is in line with the above-mentioned findings that provide indications towards CoreCivic’s self-image as being powerful and authoritative. To further deepen the understanding of how CoreCivic’s self-image is presented on their website, it is worth examining the descriptions of CoreCivic’s facilities (see Figure 3) in more detail.

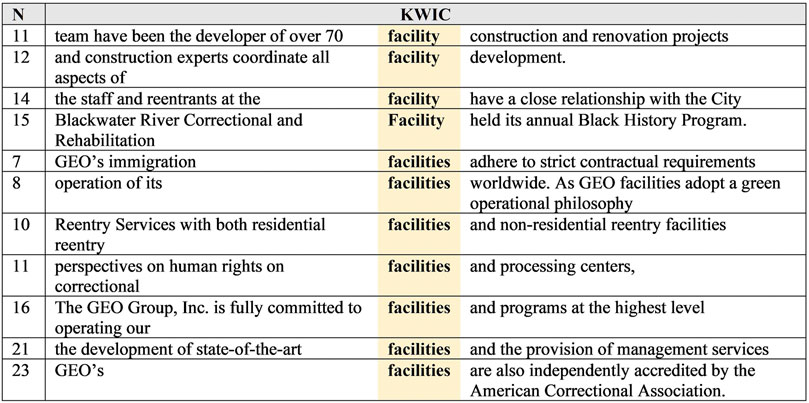

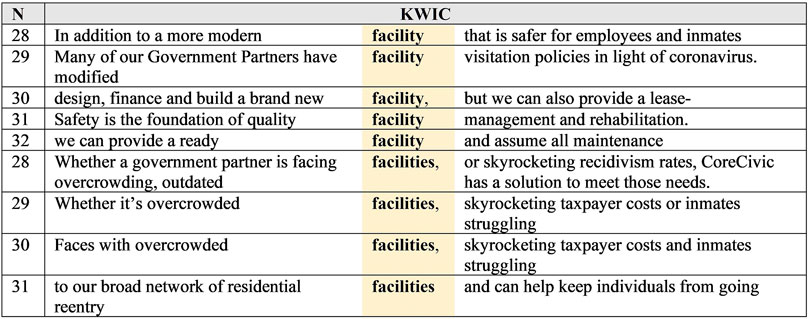

FIGURE 3. CoreCivic corpus, “facility” and “facilities” concordance lines 28–32 and 28–31, respectively.

Firstly, “facility” appears together with “correctional”, “detention”, and “CoreCivic” in 20 out of 42 concordance lines (47.6%), while the plural form collocates strongly with “our” (L1, 24%), and less strongly with “safe” (L1 and L2, 17%). Both morphological forms are used with attributive rather than predicative adjectives, which ascribe the noun phrase with an inherent quality and presuppose an underlying evaluative statement (Fairclough, 2003, p. 172; see also; Englebretson, 1997). For instance, “modern facility” presupposes the evaluative statement “this facility is modern”, thereby presuming a quality and presenting it as given and inherent.

CoreCivic: Top-Down Analysis of Issues of Interest

Previous research has revealed three potentially conflicting issues in the public and private discourses of private prison corporations: recidivism/reentry, violence/safety, and costs. The subsequent analysis will investigate these issues more closely.

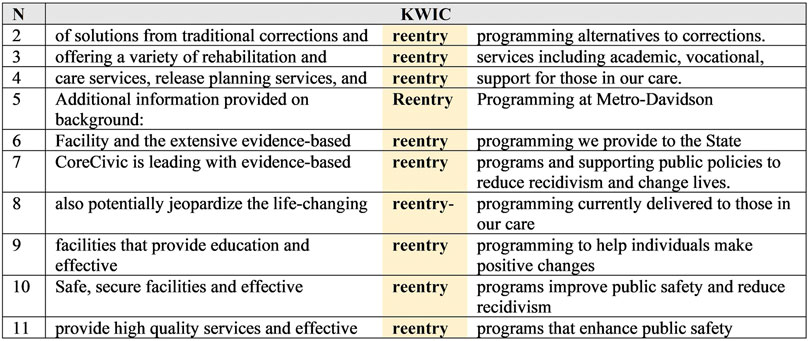

It is important to note that none of the initially identified words (recidivism, violence, safety, or costs) are explicitly mentioned in the corpus and are thus not present in either the frequency or the keyword lists, indicating their backgrounding in the discourse of the company. “Reentry”, however, which is a term related to the concept of recidivism, is the second most salient keyword in the dataset and will thus be discussed subsequently. While “reentry” takes the perspective of leaving the prison and reentering the community, “recidivism” describes a “relapse into criminal behavior” (Merriam-Webster, 2020). Thus, the focus on the CoreCivic website is on the positive process of “reentering the community”, while researchers have focused on CoreCivic’s role in the negative process of “reentering the prison” (i.e. recidivism). As Figure 4 shows, the website introduces the reader to the company’s reentry programs and describes them as evidence-based, effective, and of high quality.

A search for “recidivism” returns only 15 concordance lines (as opposed to 43 for “reentry”), six of which (i.e. 40%) occur together with either “reduce” or “reducing”. CoreCivic is described as being actively engaged in the fight against recidivism, even though the website acknowledges the recidivism crisis in the United States (see Examples (1)–(4) below).

1) working to help address America’s recidivism crisis.

2) reentry centers to help address America’s recidivism crisis.

3) are helping to address America’s recidivism crisis.

4) overcrowding, outdated facilities, or skyrocketing recidivism rates, CoreCivic has a solution

The search for “violence” and “violent” has revealed no instances of use on the CoreCivic website, indicating that these issues are not a part of the company’s discourse. The terms “safe” and “safety”, however, appear 19 and 14 times in the dataset, respectively. A collocation analysis shows that while the adjective “safe” describes “facilities” and “environments”, “safety” is associated with “corecivic” and “public.” In line with the results outlined above, these collocations suggest that CoreCivic facilities, environments, and services are presented as safe, even though the preoccupation with safety issues on the website is lower than might have been expected from previous findings. As semantically related terms, “secure” and “security” are also investigated (see Examples (5)–(10) below). Similar to “safe” and “safety”, both “secure” and “security” are used to describe CoreCivic’s facilities, and the reader is assured of the facilities’ safety and security even though this topic is not a salient one.

5) of delivering high quality, safe, cost saving secure corrections and meaningful reentry programs

6) to making a difference by operating safe, secure facilities and providing strong, active corporate

7) We operate safe, secure facilities that provide high quality services and

8) there have been modernizations in security, architectural practices, population needs and

9) environments can deem intimidating. However security is our business

10) than where they previously worked. Beyond security, our facilities are bright, clean, well-organized

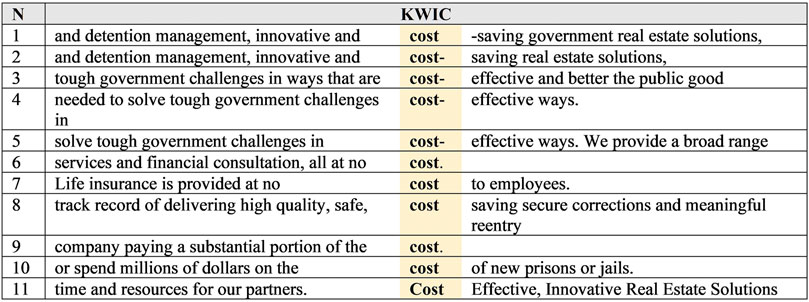

Lastly, previous research has hinted as “costs” being a central issue in the private prison industry. However, a concordance analysis of “cost” and “costs” reveals only eleven occurrences in the dataset. As shown in Figure 5, “costs” is associated with “effective” and “saving”. Thus, while “costs” are not a central concern of the company, when costs are discussed, the company’s facilities and services are presented as both cost-effective and cost-saving.

FIGURE 5. CoreCivic corpus, “cost” concordance lines.> The following section proceeds to present the findings for The GEO Group.

Bottom-Up Exploration of GEO’s Self-Presentation and Self-Image

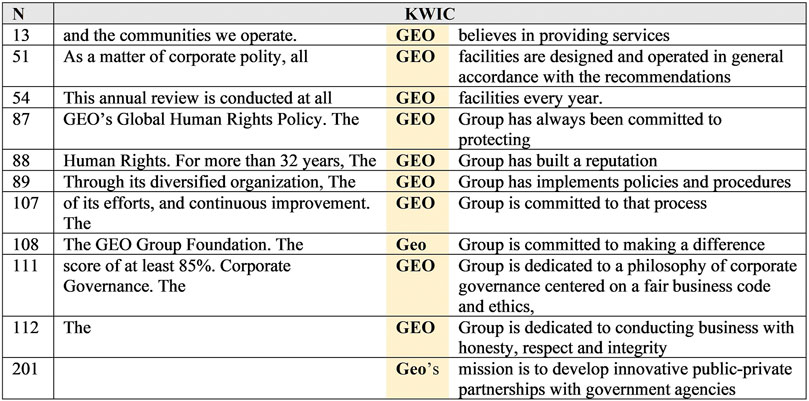

To begin the analysis, a list of the most common content words in the corpus was created (see Table 3). Similar to what was seen in Table 1 for CoreCivic, the company name is the most frequent content word in the corpus. In order to understand how the name is used in context, consider Figure 6.

The verbs “has” and “is” are identified as collocates of GEO, which suggests that GEO is presented as an active agent that does things. For examples, GEO + V constructions (25% of the dataset) depict GEO as supporting, providing, committing to, believing, striving, complying, offering and incorporating. These verbs are typically positively connoted, as the concordance lines in Figure 6 also suggest, thereby depicting the company as the initiators of positive actions.

In terms of self-presentation, the words “facilities” and “facility”, as well as “community” are of interest to this paper. Both “facility” and “facilities” are used in conjunction with descriptive adjectives such as “secure” and “rehabilitation”. In contrast to the CoreCivic website, however, the presentation of GEO’s facilities is more neutral and therefore less evaluative in nature (see Figure 7 for examples).

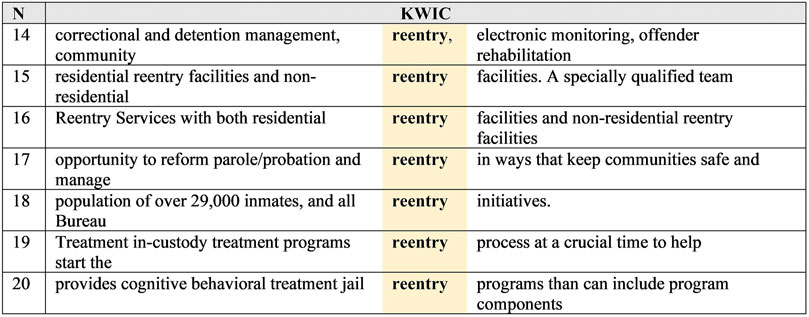

More interesting than the description of GEO’s facilities in the self-presentation of GEO is the use of the noun “community.” As Figure 8 shows, contrary to what might be expected, “community” is used to refer to the communities outside the prison rather than to the community within the prison. Thus, the use of “community” in this way creates a division between the world inside and outside the prison walls, a process which is comparable to the “othering” (e.g., Simpson, Mayr & Statham, 2019, pp. 23–26) of inmates by placing them outside the community.

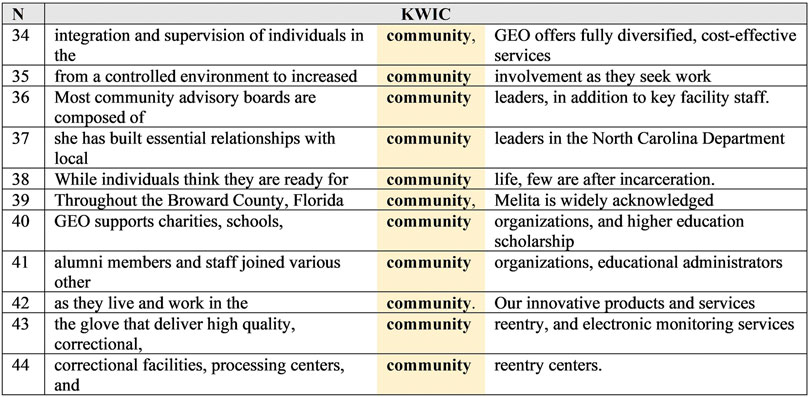

The GEO Group: Keywords in the Self-Presentation of the Company

Table 4 presents the keyword list of the GEO corpus. Intriguingly, the list of keywords is almost identical with the list of frequent words discussed above. Therefore, only the keywords “secure” and “reentry” will be investigated in more detail.

The most frequent R1 collocates of the keyword “secure” are “services”, “transportation”, “facilities”, “and”, and “environment” (80%). The adjective “secure” is thus used descriptively in conjunction with the GEO Group facilities, environments, and services, thereby reassuring the reader of their safety. This discourse strengthens GEO’s self-image as running secure facilities and counters the representations of the company’s institutions as violent created by both the media and researchers.

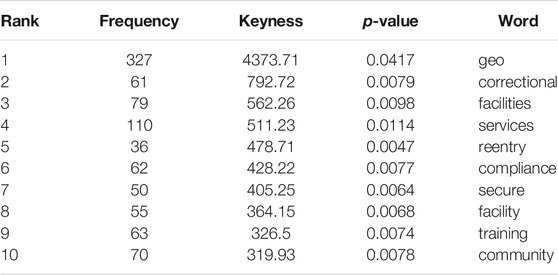

A search for “reentry” reveals 36 hits in the corpus, which shows that reentry is discussed more frequently on the website than recidivism (see below). As Figure 9 illustrates, in 50% of instances, “reentry” appears together with nouns such as “services”, “centers”, and “programs”, thereby hinting at a focus on the description of their offerings.

The GEO Group: Top-Down Analysis of Issues of Interest

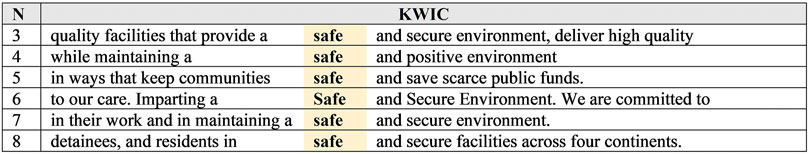

As semantically related terms of “secure”, the words “safety” and “safe” are also investigated in the context of the GEO website. Figure 10 shows that “safe” is not a common word in the GEO corpus, quite in contrast to the CoreCivic dataset. In fact, only 20 concordances were found. In 77% of the concordance lines, “safe” appears with descriptions of the environment and facilities, which are also described as “humane”, “positive”, “secure”, “nurturing”, and “structured.” Describing the facilities, services, and environments with such adjectives presents these qualities as inherent, which is a key factor in the preservation of a positive self-image of the company.

In order to view the issues of safety and security from the opposite perspective, the corpus was searched for uses of “violence” and “violent.” The search revealed two instances of the noun “violence” and no instances of the adjective “violent”, which lends support to the argument that violence is not a topic that is central to the discourse of the GEO Group. A concordance analysis further reveals that only one instance of the word “violence” is connected to events inside the prisons by referring to the “violence in the workplace policy”, while the other instance of use is connected to violence outside the prison (“to bring awareness to street violence”), thereby downplaying the importance of this issue.

Next, consider the term “recidivism”, which does not appear in the list of frequent words nor in the list of keywords, but is deemed central to the public discourse surrounding the private prison industry. Only one instance of use (Example (13) below) hints at recidivism as being an issue in the United States, while Examples (11) and (12) highlight the role of the GEO Group as actively working to reduce recidivism rates.

11) and post-release, aimed at reducing recidivism and helping the men and women

12) treatment and promoted effectiveness in reducing recidivism. By assessing inmate risks and needs and

13) reduce costs, and promotes public safety. Recidivism remains a major contributor to swelling prison

Lastly, the use of “cost” and “costs” on the GEO website is investigated. The search for “costs” reveals only eleven hits, which indicates that this topic is not central to the discourse. However, when “cost” or “costs” are used, they collocate with “effective”, “effectiveness”, and forms of “reduce” in 55% of the cases [see examples (14)–(19) below]. Thus, the GEO Group’s website stresses their cost-efficient ways of operating their prisons and related facilities, while not putting this issue at the center of their discourse overall.

14) Electronic monitoring is a safe, cost-effective, and efficient way to monitor offenders

15) in the community, GEO offers fully diversified, cost-effective services that deliver enhanced quality

16) emphasizes security, functionality, durability, and cost effectiveness as its prime objectives.

17) a green operational philosophy, both operating costs and emissions are lowered.

18) that works best for their needs, reduce costs, and promote public safety.

19) Recidivism remains a major contributor to swelling prison populations and skyrocketing costs.

Discussion

The analyses presented in this paper have revealed several interesting findings. At the outset of the analysis, it was presumed, based on the findings of previous research, that the discourse on the websites would center around the topics of costs, recidivism, and violence. The analyses have revealed that the companies are aware of and do mention the topics and issues raised by scholars and the media, but that they do so in a way that benefits their purpose of a positive self-presentation. Even though the companies address the issues of violence/safety/security and recidivism/reentry to a certain extent, they favor the presentation of the positive perspectives on these issues, i.e. they favor reentry over recidivism, and safety/security over violence. Fairclough’s (2003, p. 26) idea that different discourses “may represent the same area of the world from different perspectives or positions” is visible here: both CoreCivic and the GEO Group opt for the perspective that is favorable to them. Thus, there seems to be a discrepancy, or even a contradiction, between the public and private discourses surrounding CoreCivic and The GEO Group, Inc.

In terms of linguistic devices used for self-presentation, the companies employ descriptive adjectives and positively connoted verbs with the companies in the subject positions of the respective clauses. Further, they implicitly put themselves into a socially superior position, for example through the use of the pronoun “our”, and through implying their effectiveness, dependability, reliability, as well as strong governmental ties. This process might be supported by the “othering” of inmates and detainees through discursively dominating and controlling them—an idea which, however, has to be investigated in future research.

In contrast to expectations, neither company places a particular emphasis on “costs”, yet in those instances in which they do, they highlight the cost-effectiveness of their services and facilities. Based on what previous scholarship has demonstrated, this is a finding that can be expected; yet it counters studies such as (Mamun et al., 2020), who indeed find short-term cost-effectiveness, but no long-term benefits. This, however, is not problematized on the websites, since the websites can be regarded as marketing devices advertising the companies’ services. Advertising, as Goddard (1998, p.10, my emphasis) suggests, “is not just about the commercial promotion of branded products, but can also encompass the idea of texts whose intention is to enhance the image of an individual, group, or organisation.” Thus, the way the companies describe their services and facilities serves as a promotion of their positive self-images.

As pointed out above, violence and issues surrounding the discourse of violence and recidivism are rather backgrounded in the discourses of both companies, even though previous research has shown that reports on violence and abuse in private prisons abound (e.g., Lopez, 2016; Bauer, 2018; Williams, 2018; Ortiz & Jackey, 2019). This finding can be interpreted as the de-emphasizing of violence and recidivism. As Felton Rosulek (2015, pp. 40–50) discusses, information is de-emphasized in a certain discourse when it is present, yet only to a very small extent. That is, it is not afforded as much attention as information that is emphasized, yet it is not completely absent from the discourse either. And it is exactly that which can be said for the issues of violence and recidivism, as well as costs to a certain extent: they are present on the websites, but they are not emphasized. Thus, these issues are not a part of the private prison companies’ realities and, therefore, their private discourses. In contrast, and likely triggered by the increased news reporting on violence and abuse not only inside the penitentiaries but also inside the immigrant and youth detention centers, both corporations counter this discourse by placing a salient emphasis on the safety and security of their institutions. The findings presented in this paper can also be interpreted considering (van Dijk, 2011, p. 396) concept of the “ideological square”. This concept outlines that ideological discourse separates us from them. In the present context, this means that the prison corporations emphasize their good characteristics and achievements (e.g., active engagement in positive actions), while simultaneously de-emphasizing their own wrongdoings and problems (e.g., violence).

Furthermore, as pointed out, both websites place an emphasis on reentry and reentry services, while simultaneously backgrounding the recidivism crisis in the United States, thereby taking a positive view on their own actions as facilitating the reentry into the community rather than the reentry into prison. This focus on reentry that both corporations show is important in several respects. For example, as Ortiz and Jackey (2019) have pointed out, reentry programs have been reestablished and strengthened not long ago in order to support and facilitate offenders’ reintegration into society. However, the reigning for-profit ideology underlying the private prison system still emphasizes profit rather than rehabilitation, which clearly privileges those offenders who are in the lucky position to be able to afford reentry services. Thus, they conclude, “reentry fails even before incarcerated persons leave prisons” (Ortiz & Jackey, 2019, p. 490)—and this, they argue, is deliberate. What the presentation on the websites therefore reflects is, on the one hand, the increased general attention to the rehabilitation of offenders, but, on the other hand, just the description of another service which the corporations make profit from. It further allows the corporations to take a positive perspective on the issue and present themselves and their services in an entirely positive manner.

The research questions presented in this paper should be considered in the context of a quote by Fairclough (2003, p. 40): “what is ‘said’ in a text is ‘said’ against a background of what is ‘unsaid’, but taken as given.” Thus, it is not only of importance what kind of information the websites contain; it is indeed at least equally important what the websites do not contain. Often, information that is absent from the discourse is deliberately backgrounded or taken for granted—i.e. presupposed. Importantly, though, even if particular pieces of information are simply presupposed and thus not deemed worthy of mentioning, the missing pieces can reveal ideological positions and worldviews (e.g., Fairclough, 2003). As has been commented on above, the issues of costs and violence, for example, are rather backgrounded or silenced on both websites. However, they are likely de-emphasized, or even silenced, for different reasons: costs are possibly de-emphasized because it is presupposed that private prisons work more cost-efficiently than public prisons—it is therefore not deemed worth mentioning. Violence, though, does not receive much attention, as, on the one hand, the companies do not identify it as a central issue that needs to be discussed on the websites, and, on the other hand, it would not be good advertising for their companies. Therefore, they clearly prefer to strengthen their focus on safety and security, reassuring readers and policy makers that their environments, facilities, and services are both safe and secure for inmates and employees alike.

Conclusion

The problem of mass incarceration in the United States is tremendous. As (Liptak, 2008, online) points out, “the United States has less than 5% of the world’s population. But it has almost a quarter of the world’s prisoners.” It is therefore unsurprising that public facilities have been facing challenges with having to house high numbers of prisoners. As has been pointed out before, private prison corporations have a high interest in keeping their beds occupied: thus, they lobby for harsher punishment (Craig and pond cummings, 2020) and are said to have no actual interest in the rehabilitation of offenders (e.g., Bauer, 2018). It has further been argued that they play a critical role in the continued growth of the prison population in the United States. Craig and pond cummings (2020, p. 262) state that the creation of this private prison corporation ushered in a new carceral era where the traditional government function of adjudicating crime, punishment, and imprisonment became intertwined with the corporate governance principles and goals of profit maximization for shareholders; executive compensation based on profits and share price; forward-looking statements forecasting more robust prison populations; and increased profit levels built almost solely on human misery and degradation.

This paper has specifically investigated the language used on the CoreCivic and The GEO Group’s websites, and the analyses have revealed that both companies particularly strengthen their identities in terms of safety and security, while simultaneously de-emphasizing or backgrounding violence, recidivism, and costs. The corporations take a positive perspective on the issues raised by scholars and journalists in that they focus on “reentry” much more than on “recidivism”, for instance. On the one hand, the particular focus on reentry and safety may be a consequence of an increased reporting on the violence inside the prisons, and of a policy that centers on the rehabilitation of offenders while simultaneously earning money with each offender who makes use of a reentry program or service, on the other hand. The websites are therefore highly effective marketing devices for the private prison corporations and can be considered to be just one part of what pond cummings and Lamparello (2016, p. 429) baldly call the corporations’ “effective propaganda.”

Even though the picture painted in the quote from Craig and pond cummings’ (2020) article above is dire, there are promising movements into a new direction: indeed, after his inauguration as the 46th president of the United Stated, Joe Biden has signed an order that disallows the Department of Justice to renew contracts with private prison companies (Buchholz, 2021); a process that had been set into motion by former president Barack Obama but which was later reversed under the Trump administration (e.g., Enns & Ramirez, 2018, pp. 546–7). These actions may be the first step towards improved conditions for inmates and employees in private prisons.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: Websites of CoreCivic and The GEO Group.

Author Contributions

KM, as the sole author, collected the data, analyzed it, and summarized the findings as well as the literature on the topic.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the financial support by the University of Graz.

Footnotes

1Mandatory-minimums refer to the practice of punishing certain crimes with automatic minimum sentences (Famm.com, 2021, online).

2According to (San Diego County, 1994, online), the original purpose of Three Strikes Laws was to “dramatically increase punishment for persons convicted of a felony who have previously been convicted of one or more “serious” or “violent” felonies”, while nowadays many people who serve sentences on the basis of this law they have committed non-violent crimes (Stanford, 1994, online).

3The founder of CoreCivic (Bauer, 2018, online).

4As a collocation measure, Mutual Information (MI) was used, which is “calculated by examining all of the places where two potential collocates occur in a text (and then) comput(ing) what the expected probability of these two words occurring near each other would be, based on their relative frequencies and the overall size of the corpus” (Baker, 2006, p. 101).

5“The p-value (…) indicates the amount of confidence that we have that a word is key due to chance alone—the smaller the p-value, the more likely that the word’s strong presence in one of the sub-corpora isn’t due to chance but a result of the author’s (conscious or subconscious) choice to use that word repeatedly” (Baker, 2006, p. 125). In this study, the significance cut-off point was set at p = 0.05.

6President and Chief Executive of CoreCivic (CoreCivic, 2021).

References

AFSC (2019a). CoreCivic Inc. Available at: https://investigate.afsc.org/company/corecivic (accessed Feb 18th, 2021).

AFSC (2019b). The GEO Group Inc. Available at: https://investigate.afsc.org/company/geo-group (accessed Feb 18th, 2021).

ANC (2015). The Open American National Corpus. Available at: http://www.anc.org (accessed Dec 20th, 2020).

Angola Museum (2019). History of Angola. Available at: https://www.angolamuseum.org/history-of-angola (accessed Aug 20th, 2021).

Anthony, L. (2020). AntConc. (Version 3.5.8). [Computer Software]. Tokyo, Japan: Wasada University. Available from https://www.laurenceanthony.net/software.

Austin, J., and Coventry, G. (2001). Emerging Issues on Privatized Prisons. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Assistance. NCJ 181249.

Baker, P., Gabrielatos, C., KhosraviNik, M., Kryzanowski, M., Krzyżanowski, M., McEnery, T., et al. (2008). A Useful Methodological Synergy? Combining Critical Discourse Analysis and Corpus Linguistics to Examine Discourses of Refugees and Asylum Seekers in the UK Press. Discourse Soc. 19 (3), 273–306. doi:10.1177/0957926508088962

Bauer, S. (2016). My Four Months as a Private Prison Guard. Mother Jones. Available at: http://www.motherjones.com/politics/2016/06/cca-private-prisons-corrections-corporation-inmates-investigation-bauer (accessed Feb 10th, 2021).

Bauer, S. (2018). The True History of America’s Private Prison Industry. TIME. Available at: https://time.com/5405158/the-true-history-of-americas-private-prison-industry/ (accessed Dec 17th, 2020).

Blodgett, A., and Schneider, N. (2018). Semantic Supersenses for English Possessives. Proc. LREC, 1529–1534.

Buchholz, K. (2021). Private Prisons in the United States. Available at: https://www.statista.com/chart/24058/private-prisons/(accessed Feb 12th, 2021).

Burkhardt, B. C. (2017). Who Is in Private Prisons? Demographic Profiles of Prisoners and Workers in American Private Prisons. Int. J. L. Crime Justice 51, 24–33. doi:10.1016/j.Ijlcj.2017.04.004

Burnett, J. (2012). Miss. Prison Operator Out; Facility Called a ‘cesspool’. Available at: https://www.npr.org/2012/04/24/151276620/firm-leaves-miss-after-its-prison-is-called-cesspool?t=1613651715906 (accessed Dec 10th, 2020).

Camp, S. D., and Gaes, G. G. (2002). Growth and Quality of U.S. Private Prisons: Evidence from a National Survey*. Criminology Public Policy 1 (3), 427–450. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9133.2002.tb00102.x

CoreCivic (2021). Leading with Passion and Commitment. Available at: https://www.corecivic.com/about/executive-leadership (accessed Feb 17th, 2021).

Cornell University (2020). Private Prisons vs. Public Prisons and its Application in Networks. Available at: https://blogs.cornell.edu/info2040/2020/09/30/private-prisons-vs-public-prisons-and-its-application-in-networks/ (accessed Feb 16th, 2021).

Cotterill, J. (2003). Language and Power in Court: A Linguistic Analysis of the OJ Simpson Trial. Basingstroke, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Coulthard, M. (1994). On the Use of Corpora in the Analysis of Forensic Texts. Forensic Linguistics 1 (1), 27–43.

Craig, R., and pond cummings, a. d. (2020). Abolishing Private Prisons: a Constitutional and Moral Imperative. Univ. Baltimore L. Rev. 49 (3), 261–312.

Durose, M. R., Cooper, A. D., and Snyder, H. N. (2014). Recidivism of Prisoners Released in 30 States in 2005: Patterns from 2005 to 2010. Bur. Justice Stat. NCJ 244205. Available at: http://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=4986.

Duwe, G., and Clark, V. (2013). The Effects of Private Prison Confinement on Offender Recidivism. Criminal Justice Rev. 38 (3), 375–394. doi:10.1177/0734016813478823

Englebretson, R. (1997). Genre and Grammar: Predicative and Attributive Adjectives in Spoken English. Bls 23, 411–421. doi:10.3765/bls.v23i1.1272

Enns, P. K., and Ramirez, M. D. (2018). Privatizing Punishment: Testing Theories of Public Support for Private Prison and Immigration Detention Facilities. Criminology 56 (3), 546–573. doi:10.1111/1745-9125.12178

Esquivel, P. (2017). Detainees End Brief Hunger Strike at Adelanto Immigration Facility, Officials Say. Available at: https://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-ln-adelanto-hunger-strike-20170614-story.html (accessed Feb 1st, 2021).

Fairclough, N. (2003). Analysing Discourse. Textual Analysis for Social Research. London, UK & New York, NY: Routledge.

Famm.com (2021). How a Sentence Is Determines: Mandatory Minimums and Guidelines. Available at: https://famm.org/our-work/sentencing-reform/sentencing-101/(accessed Feb 15th, 2021).

Felton Rosulek, L. (2015). Dueling Discourses. The Construction of Reality in Closing Arguments. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Flowerdew, J. (2008). “Critical Discourse Analysis and Strategies of Resistance,” in Advances in Discourse Studies. Editors V. Bhatia, J. Flowerdew, and R. Jones (London, UK & New York, NY: Routledge), 195–210.

Gabrielatos, C., and Baker, P. (2008). Fleeing, Sneaking, Flooding. J. English Linguistics 36 (1), 5–38. doi:10.1177.007542420731124710.1177/0075424207311247

Gaes, G. G. (2019). Current Status of Prison Privatization Research on American Prisons and Jails. Criminology & Public Policy 18, 269–293. doi:10.1111/1745-9133.12428

Gales, T. (2015). The Stance of Stalking: a Corpus-Based Analysis of Grammatical Markers of Stance in Threatening Communications. Corpora 10 (2), 171–200. doi:10.3366/cor.2015.0073

Goddard, A. (1998). The Language of Advertising. Written Texts. London, England & New York, NY: Routledge.

Gotsch, K., and Basti, V. (2018). Capitalization on Mass Incarceration. U.S. Growth in Private Prisons. Washington, D.C.: Sentencing Project. Available at: https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/capitalizing-on-mass-incarceration-u-s-growth-in-private-prisons/.

Griebel, T., and Vollmann, E. (2019). We Can('t) Do This. Jlp 18 (5), 671–697. doi:10.1075/jlp.19006.gri

Gruber, M. C. (2014). “I’m Sorry for what I’ve done.” the Language of Courtroom Apologies. Oxford, England: OUP.

Gruberg, S. (2015). How For-Profit Companies Are Driving Immigration Detention Policies. Cent. Am. Prog. URL Available at: https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/immigration/report/2015/12/18/127769/how-for-profit-companies-are-driving-immigration-detention-policies/ (accessed Feb 10th, 2021).

Hallett, M. (2006). Private Prisons in America: A Critical Race Perspective. Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Hatry, H., Brounstein, P., and Levinson, R. (1993). “A Comparison of Privately and Publicly Operated Corrections Facilities in Kentucky and Massachusetts,” in Privatizing Correctional Institutions. Editors G. Bowman, S. Hakim, and P. Seidenstat (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction), 193–212.

Heffer, C. (2005). The Language of Jury Trial: A Corpus-Aided Analysis of Legal-Lay Discourse. Basingstroke, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kandel, W. A. (2018). The Trump Administration’s “Zero Tolerance” Immigration Enforcement Policy. CRS Report. Available at: https://trac.syr.edu/immigration/library/P14693.pdf (accessed Feb 23rd, 2021).

Katsiyannis, A., Whitford, D. K., Zhang, D., and Gage, N. A. (2018). Adult Recidivism in United States: A Meta-Analysis 1994-2015. J. Child. Fam. Stud. 27, 686–696. doi:10.1007/s10826-017-0945-8

Knoblock, N. (2020). Silent Majority or Vocal Minority: A Corpus-Assisted Discourse Study of Trump Supporters' Facebook Communication. Open Libr. Humanitites 6 (2), 1–37. doi:10.16995/olh.507

Kredens, K. (2002). “Towards a Corpus-Based Methodology of Forensic Authorship Attribution: a Comparative Study of Two Idiolects,” in PALC’01: Practical Applications in Language Corpora. Editor B. Lewandowska-Tomaszczyk (Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Peter Lang), 405–437.

Lambert, E. G., Hogan, N. L., Griffin, M. L., and Kelley, T. (2015). The Correctional Staff Burnout Literature. Criminal Justice Stud. 28 (4), 397–443. doi:10.1080/1478601x.2015.1065830

Liptak, A. (2008). Inmate Count in U.S. Dwarfs Other Nations. N.Y. TIMES. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/23/us/23prison.html (accessed Dec 10th, 2020).

Logan, C. (1991). Well Kept: Comparing Quality of Confinement in a Public and Private Prison. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice.

Lopez, G. (2016). A Federal Report Just Confirmed it: For-Profit Prisons Are More Dangerous Than Public Ones. VOX. Available at: https://www.vox.com/2016/8/12/12454410/private-prisons-violence-investigation (accessed Feb 12th, 2021).

Ludlow, A. (2017). “Marketizing Criminal justice,” in The Oxford Handbook of Criminology. Editors A. Liebling, S. Maruna, and L. McAra (Oxford, England: OUP), 914–937.

Lukemeyer, A., and McCorkle, R. C. (2006). Privatization of Prisons. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 36 (2), 189–206. doi:10.1177/0275074005281352

Makarios, M. D., and Maahs, J. (2012). Is Private Time Quality Time? A National Private-Public Comparison of Prison Quality. Prison J. 92, 336–357. doi:10.1177/0032885512448608

Mamun, S., Li, X., Horn, B. P., and Chermak, J. M. (2020). Private vs. Public Prisons? A Dynamic Analysis of the Long-Term Tradeoffs between Cost-Efficiency and Recidivism in the US Prison System. Appl. Econ. 52 (41), 4499–4511. doi:10.1080/00036846.2020.1736501

Matthews, A., and Kotzee, B. (2019). The Rhetoric of the UK Higher Education Teaching Excellence Framework: a Corpus-Assisted Discourse Analysis of TEF2 Provider Statements. Educ. Rev. 73, 523–543. doi:10.1080/00131911.2019.1666796

McDonald, D., Fournier, E., Russell-Einhorn, M., and Crawford, S. (1998). Private Prisons in the United States: An Assessment of Current Practice. Cambridge, MA: Abt Associates.

Merriam-Webster (2021). Care. Available at: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/care.

Merriam-Webster (2020). Recidivism. Available at: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/recidivism.

Mukherjee, A. (2014). Does Prison Privatization Distort justice? Evidence on Time Served and Recidivism. SSRN J. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2523238

Nartey, M., and Mwinlaaru, I. N. (2019). Towards a Decade of Synergizing Corpus Linguistics and Critical Discourse Analysis: a Meta-Analysis. Corpora 14 (2), 1–26. doi:10.3366/cor.2019.0169

Ortiz, J. M., and Jackey, H. (2019). The System Is Not Broken, it Is Intentional: the Prisoner Reentry Industry as Deliberate Structural Violence. Prison J. 99 (4), 484–503. doi:10.1177/0032885519852090

Page, J. (2011). The Toughest Beat: Politics, Punishment, and the Prison Officers' Union in California, Studies in Crime and Public Policy. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Partington, A. (2008). “Metaphors, Motifs and Similies across Discourse Types: Corpus Assisted Discourse Studies (CADS) at Work,” in Corpus-based Approaches to Metaphor and Metonymy. Editors A. Stefanowitsch, and S. T. Gries (Berlin, Germany: de Gruyter), 258–294.

Partington, A. (2003). The Linguistics of Political Argumentation: The Spin-Doctor and the Wolf-Pack at the White House. London, England: Routledge.

Pauly, M. (2017). In 3 Months, 3 Immigrants Have Died at a Private Detention center in California. Available at: https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2017/06/adelanto-death-immigration-detention-geo/(accessed Feb 1st, 2021).

Petersilia, J. (2003). When Prisoners Come home: Parole and Prisoner Reentry. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

pond cummings, A. D., and Lamparello, A. (2016). Private Prisons and the New Marketplace for Crime. Wake For. J. L. Pol. 6 (2), 407–440.

Powers, R. A., Kaukinen, C., and Jeanis, M. (2017). An Examination of Recidivism Among Inmates Released from a Private Reentry center and Public Institutions in Colorado. Prison J. 97 (5), 609–627. doi:10.1177/0032885517728893

Pratt, T. C., and Maahs, J. (1999). Are Private Prisons More Cost-Effective Than Public Prisons? A Meta-Analysis of Evaluation Research Studies. Crime & Delinquency 45 (3), 358–371. doi:10.1177/0011128799045003004

Price, B. E., Carrizales, T. J., and Schwester, R. W. (2009). Race and Ethnicity as Determinants of Privatizing State Prisons. Int. Rev. Public Adm. 13 (3), 81–88. Available at: https/doi.org/10.1080/12294659.2009.10805132. doi:10.1080/12294659.2009.10805132

Reasons, C. E., and Kaplan, R. L. (1975). Tear Down the Walls. Crime & Delinquency 21, 360–372. doi:10.1177/001112877502100408

Ryan, M., and Ward, T. (1989). Privatization and the Penal System: The American Experience and the Debate in Britain. Milton Keynes, England: Open University Press.

Salama, A. H. Y. (2011). Ideological Collocation and the Recontexualization of Wahhabi-Saudi Islam post-9/11: A Synergy of Corpus Linguistics and Critical Discourse Analysis. Discourse Soc. 22 (3), 315–342. doi:10.1177/0957926510395445

San Diego County (1994). Three Strikes Law – A General Summary. Available at: https://www.sandiegocounty.gov/public_defender/strikes.html (accessed Feb 15th, 2021).

Silva, D. (2019). Migrant Mom Details Daughter’s Death after ICE Detention in Emotional Testimony. NBC News. Available at: https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/migrant-mom-details-daughter-s-death-after-ice-detention-emotional-n1028471 (accessed Aug 26th, 2021).

Simmons, M. (2013). Punishment & Profits: A Cost-Benefit Analysis of Private Prisons. OKLA. Pol'y INST. Available at: http://okpolicy.org/punishment-profits-a-cost-benefit- analysis-of-private-prisons (accessed Feb 10th, 2021).

Smith, K. B. (2004). The Politics of Punishment: Evaluating Political Explanations of Incarceration Rates. J. Polit. 66, 925–938. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2508.2004.00283.x

Spivak, A. L., and Sharp, S. F. (2008). Inmate Recidivism as a Measure of Private Prison Performance. Crime & Delinquency 54 (3), 482–508. doi:10.1177/0011128707307962

Stanford Tagger (2003). Stanford Log-Linear Part-Of-Speech Tagger. Retrieved from: http://nlp.stanford.edu/software/tagger.shtml.

Stanford (1994). Three Strikes Basics. Available at: https://law.stanford.edu/stanford-justice-advocacy-project/three-strikes-basics/ (accessed Feb 10th, 2021).

Stephan, J. J. (2008). Census of State and Federal Correctional Facilities 2005. Washington, D.C: Bureau of Justice Statistics.

The GEO Group (2021). GEO Group History Timeline. Available at: https://www.geogroup.com/history_timeline (accessed Feb 18th, 2021).

Thomas, C., and Logan, C. (1993). “The Development, Present Status, and Future Potential of Correctional Privatization in America,” in Privatizing Correctional Institutions. Editors G. Brown, S. Hakim, and P. Seidenstat (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction), 213–240.

Thompkins, D. E. (2010). The Expanding Prisoner Reentry Industry. Dialectical Anthropol. 34, 589–604.

Tkacuková, T. (2015). A Corpus-Assisted Study of the Discourse Marker ‘well’ as an Indicator of Judges’ Institutional Roles in Court Cases with Litigant in Person. Corpora 10 (2), 145–170.

Van Dijk, T. A. (2011). “Discourse and Ideology,” in Discourse Studies: A Multidisciplinary Introduction. Editor T. van Dijk (London, England: Sage), 379–407.

Wessler, S. F. (2016). This man will almost certainly die. The Nation. URL. Available at: https://www.thenation.com/article/privatized-immigrant-prison-deaths/ (accessed Feb 10th, 2021).

Williams, T. (2018). Inside a Private Prison: Blood, Suicide and Poorly Paid Guards. The New York Times. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/03/us/mississippi-private-prison-abuse.html (accessed Feb 12th, 2021).

Wofford, T. (2014). The Operators of America’s Largest Immigrant Detention center Have a History of Inmate Abuse. Available at: https://www.newsweek.com/operators-americas-largest-immigrant-detention-center-have-history-inmate-293632 (accessed Feb 1st, 2021).

Woodman, S. (2017). Exclusive: ICE Put Detained Immigrants in Solidary Confinement for Hunger Striking. Available at: https://www.theverge.com/2017/2/27/14728978/immigrant-deportation-hunger-strike-solitary-confinement-ice-trump (accessed Dec 10th, 2020).

Wright, D. (2021). “Corpus Approaches to Forensic Linguistics. Applying Corpus Data and Techniques in Forensic Contexts,” in The Routledge Handbook of Forensic Linguistics. Editors M. Coulthard, A. May, and R. Sousa-Silva. 2nd edn. (London, England: E-book).

Keywords: forensic linguistics, private prisons, recidivism, safety, costs, violence, self-presentation

Citation: Marko K (2021) Serving the Public Good?—A Corpus-Assisted Discourse Analysis of Private Prisons and For-Profit Incarceration in the United States. Front. Commun. 6:672110. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2021.672110

Received: 25 February 2021; Accepted: 18 October 2021;

Published: 05 November 2021.

Edited by:

David Wright, Nottingham Trent University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Robbie Love, Aston University, United KingdomTara Coltman-Patel, Lancaster University, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2021 Marko. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Karoline Marko, a2Fyb2xpbmUubWFya29AdW5pLWdyYXouYXQ=

Karoline Marko

Karoline Marko