Abstract

A suspicion for perspectives that differ from one’s own is not new to human interactions. What is new, however, is the disregard and the resultant disrespect that colours mainstream discourse across the globe today, whether in the media or in person. This creates barriers to healthy interaction and hence to learning from collaboration. Our team comprises a Tibetan Buddhist monk, a writer, an editor, and a neuroscientist, and we hope this paper, guided and crafted by a regard for the diversity of our experiences across two continents, can demonstrate how respectful and productive conversations can be achieved. We begin by stating the need for forms of communication that are very different from prevailing modes of interaction. We then examine the mechanics of debate that form the foundations of communication and learning in Buddhist monastic communities and discuss how this form of debate can help us arrive at harmonious interactions. Finally, we propose a format for respectfully initiating, maintaining, and ending conversations that take place anywhere from the classroom to the boardroom and newsroom.

Introduction

Conversations these days reflect our socio-political reality—fragmented, polarised, distrustful, and disrespectful. The reasons for this are many—political demagoguery, religious xenophobia, aggressive sports, identity politics and media echo chambers—and these and other inflammatory social forces build upon and reinforce the “us versus them” mindset that is deeply ingrained into human social structures across the globe. This perfect storm of upheaval keeps us divided and steals opportunities for us to work collaboratively towards creating a safer and harmonious world for all. Our work has exposed us to a range of diverse experiences, from those of a Tibetan Buddhist monk learning the scientific method, a neuroscientist teaching his subject to Tibetan Buddhist monastics as part of the Emory Tibet Science Initiative, and of writing and editing literature through a multi-cultural lens. This wealth of experience has shown us the need to foster dialogue in the Tibetan tradition—respectful engagement with diverse perspectives, focused not so much on being right as on discovering what is right for all. We view collaborative and not partisan conversation to be part of that utopia and we use this writing to articulate why and how we can achieve the same.

Conversations as Competitive Sport

Ideally, conversations with differing perspectives would be conducted in the manner of two respectful pugilists in the ring. They would greet each other at the beginning, pay mind to the rules of the sport, tease with their strengths while drawing out weaknesses, and each aim to achieve their goal slowly and by accumulating technical points for successive punches landed. Now, conversations resemble the chaos of modern boxing. They are loud, flashy, designed to overwhelm the opponent with bluster, and are often played short and only until one can land a knock-out blow, regardless of whether a point has truly been made or not.

The Gonpa as a Benevolent Battleground

The debating courtyard of any Tibetan Buddhist monastery (a gonpa) in the evening is like a sea at sunset. It is colourful, calm and still on the surface, but it thrums with the often unseen and unheard movements of minds in motion with one another. Clapping, and even stomping, punctuate the indistinct murmuring. This often leads the brain into thinking one is in the expectant crowd gathering before a rally or concert, waiting for things to begin. Such aural confusion is reinforced by the sight of waves of monks and nuns in these courtyards, clad in their maroon robes as they undulate like gentle swells on their way in to the sands of serenity. Their traditions of debate date back centuries, and watching these scholars debate complex existentialist thought in a joyful and respectful manner is as revealing as a Sun rising over a dark ocean and lighting up their steps in the sand. It is in following in these footsteps that we believe the path to changing the tenor and outcomes of our contemporary conversations lies.

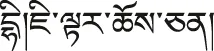

The way every debate begins is itself demonstrative of how antithetical this style is to current styles of discourse and why it might serve as the antidote we so sorely need. No matter whether the debate includes two monastics or whole debating “teams”, every debate begins with  (Dhee Jhe Tar Choe Chen), which translates into “Let us mover closer to the truth.” After invoking this mantra, one member (or team) assumes the role of the defender of the matter being debated and sits, while the other remains standing and assumes the role of the challenger. And so, the debate begins.

(Dhee Jhe Tar Choe Chen), which translates into “Let us mover closer to the truth.” After invoking this mantra, one member (or team) assumes the role of the defender of the matter being debated and sits, while the other remains standing and assumes the role of the challenger. And so, the debate begins.

The first thing that gets put away is ego, and the desire to move closer to the truth becomes the driving force of this serious and intense pursuit. Often, debates start with the clear defining of every component of the construct in question. This ensures that the grounds for debate are known to both parties, creating a clearly stated and agreed upon set of priors which can be discussed sans misinterpretation. The debaters then start challenging and defending their positions by employing logic and citing testimonial resources and references from their texts. If an agreement has not been reached at the end of this period of personal debate, many monastics tend to take the topic into group debates that begin right after the one-on-one debate has ended. If the groups and all their varied perspectives still cannot help resolve the debate, it is then presented to their teachers in pursuit of further clarification and eventual resolution. Debates can become heated affairs. Sometimes, debates are resolved and sometimes, both parties agree that there is a differing of their views which makes agreement not possible. But regardless of the end result, there is no winner or loser in this form of engagement. Only happy seekers of a truth that applies to all.

One of the more interesting aspects of the debate is the role that gestures play, each of which has its own significance. One of these occurs when one palm is slapped downwards by the other in a rapid cadence and the hitting palm then slightly withdrawn towards the body. This might sometimes be accompanied by a jump and/or a swivel. The slap of the palm is meant to signify striking a wisdom nerve in the hope that the challenger and defender receive wisdom. The downward motion symbolises closing the door to ignorance. The slight backward pull of the hitting hand serves as a reminder to open the door of knowledge, and to not hold on to opinions too tightly. Slight variations of these gestures and movements are a manifestation of that monastic’s personality and it is heartening to see the debate leave room for personal expression.

But it isn’t all fun and games at the gonpa. Debating monastics prepare rigorously. They read their scriptures, receive learning from their teacher, reflect over it, and then arrive at their own interpretation of the scripture. Fortified by this process, the monastic then enters the debate. Like boxers sizing up one another, the debaters spar and use their arguments as punches and counterpunches, but with one critical difference from the ring—there is no winner or loser at the end of this match. Instead, the monastics retire to their khangtsens (living quarters), where they reflect upon the debate. Then, they revisit both sides of the debate and refine their positions in preparation for a rematch the next day. However, there is one key difference here. In the next round, they swap positions! Yesterday’s defender is today’s challenger and vice versa. This forces the debaters to examine every aspect and angle of the same argument, exposing each of them to perspectives that they might otherwise not have encountered. Any dogma can now be dispelled and objectivity can now be pursued. This leads to a nuanced understanding of not only the topic before the debater but also the one sitting across.

Reading about the mechanics and interpretation of this tradition might leave one wondering about its utility. What, after all, is the purpose of a debate if not to change minds? Here, too, the underlying motivation to debate sheds light on its usefulness. The primary reason for engaging in debate is sharpening one’s intellectual understanding of a certain concept so as to refine or restructure one’s philosophical and spiritual knowledge of the concept and achieve spiritual growth. Never is it intended to pit winning against losing. Instead, it is designed and engaged in for the purpose of enriching logical understanding of concepts with depth and width of perspective. Through the exchange of contrary ideas about the concept that is being debated, the debate is considered to be an analytical meditation that one can use to build logical foundations to maintain or restructure convictions of philosophical concepts. This rigor also reinforces the importance of objectivity, a key component of fruitful and respectful debate. Using the building blocks of logic is an integral principle of the debate that serves to internalize and mold existing understanding of the concept into practical and transformative spiritual practices.

Learnings From the Monastery for a Modern World—Conversations as Collaborations and Not Competitions

To have an objective, respectful conversation is to come away from it with an expanded perspective that serves to educate and inspire oneself and those we engage with. It is worth noting that debate teams and clubs in Western society afford participants rigorous training in the discussion and defence of multiple positions on a given issue. In doing so, such debating teams and clubs allow us to hope that wrestling with diverse perspectives is both a possible and worthy pursuit. However, with less attention now paid in these venues towards maintaining objectivity and respectful dialogue while facing the headwinds of polarization outside their doors, the Tibetan debating system shines light to guide our path to this goal.

Surrender “Us Versus Them.”

Divided as we are, we have been further polarized by the COVID-19 pandemic. These turbulent times have heightened the suspicions that many have of those who look, talk, dress, worship, and vote differently from themselves, giving rise to an unprecedented level of identity politics. In the United States, 64% of the population believes that inter-personal trust is declining, and 70% believe that this is a big hindrance to problem solving (Pew Research Center, 2019). One of the factors that builds up this mistrust is the egotism that can accumulate from an insular approach to life in our media, social and political bubbles. This approach makes us believe that we and our ways are superior to anyone else and theirs. If we learn from how Tibetan monastics shed their ego before they enter their debates, trusting the person across from us can become easier. We can then look to learn from everyone we meet and engage with since we discover that we are but one piece in the mosaic that is humanity.

Be Curious, yet Patient

The monastics are among the most curious students that our neuroscientist teammate has ever encountered. Their desire to understand the world around us better is deeply rooted in wanting to understand the causes and consequences of suffering with a view towards eliminating it. Driven by this lofty goal, they soak up every strand of information they encounter during the debate and weave it into their existing tapestry of knowledge. And to do so, they pay rapt attention to what is being discussed, listening more than speaking, waiting patiently for their turn to share their perspectives on the matters being discussed.

Prepare Rigorously and Objectively

Even if we choose one side of a debate, we should be prepared to argue both. Spend time reading and researching, engage with teachers, peers, and loved ones, and reflect on all one has heard and gleaned before entering the debate. This allows for a fuller immersion into the topic before we step into its waters. Delving deeper into both perspectives of a debate also allows for an objectivity that leads to a lack of attachment to one’s position. While this lack of anchoring runs counter to how we are raised and how discourse is now conducted, it opens us to the objective truth and reduces subjective bias. Additionally, grappling with contrasting perspectives allows for a distinction to be made between the position being debated and making a value judgement about the person engaged in the debate. By doing so, we can create and hold space for those whose views differ from our own.

Disagree Respectfully

In the debating courtyards of the gonpas, there are no permanent positions in the pursuit of a destination. The challenger and defender exchange positions and accept any perspectives that help them understand their goal better. Attachment to one’s ideas and aversion to other perspectives is forgone in the acceptance of one not possibly holding all the knowledge required to move closer to the truth on the topic being discussed. In the same way, we should remember to not be stubborn about our perspectives when debating because this can often lead to fractious engagement from which we gain nothing and only lose friends and allies. The monastics teach us two lessons that do not necessarily remedy disagreement but move us closer towards doing so. First, they lean into the discomfort of conflict knowing that it is a critical component of moving closer to the truth. By not fighting this disquiet, the ego is not stung by disagreement and accepts it as par for course. Second, the monastics accept that some differences are bigger than what the current conversation can address. From this perspective, they pivot to a collective effort and include more partners in their conversations either by way of bringing the disagreement to a group debate or seeking counsel from their teachers.

In conclusion, there is an immediate and critical need to alter the tone and tenor of our current conversations. The Tibetan system of monastic debate has the potential to show us how to arrive at harmony from our current cacophony. To bring the various pieces together into a symphony might be easier said than done. However, with intention and attention to its various parts as outlined above, we posit that we can create this music. Together.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

BGD conceived of the concept. LS, MD, ND and BGD wrote the article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Pew Research Center (2019). Trust and Distrust in America. https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2019/07/22/trust-and-distrust-in-america/ (Accessed Sep. 21, 2021).

Summary

Keywords

conversation, respect, monastics, disagreement in conversations, principles of good conversation

Citation

Sangpo L, Dhuldhoya M, Dhuldhoya N and Dias BG (2021) Fostering Respectful and Productive Conversations: Lessons Learned From Debating Courtyards in Tibetan Buddhist Monasteries. Front. Commun. 6:755445. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2021.755445

Received

08 August 2021

Accepted

14 September 2021

Published

08 October 2021

Volume

6 - 2021

Edited by

Arri Eisen, Emory University, United States

Reviewed by

Odaro Huckstep, US Air Force Academy, United States

John F. Rawls, Duke University, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2021 Sangpo, Dhuldhoya, Dhuldhoya and Dias.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Brian G Dias, bdias@chla.usc.edu

This article was submitted to Science and Environmental Communication, a section of the journal Frontiers in Communication

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.