- 1Department of German Studies, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria

- 2Institute for Communication and Media Studies, University of Leipzig, Leipzig, Germany

Internet memes are an integral part of social media communication and a popular genre for humorous engagement in online political discourses. A meme is a collective of multimodal signs that refer to each other through shared formal, content-related, and/or stance-related characteristics and can be recontextualized on different levels: (1) language, (2) mode of presentation, and (3) humor. In this paper, we examine the perceptions and effects of recontextualization in image macros—the most prominent meme subgenre. Two between-subjects online experiments from Austria offer a holistic approach to meaning-making through multimodal recontextualization in political image macros. The first experiment explored the perception of language variety and its effects on users' intentions to forward a humorous image macro. The second experiment further investigated the effects of a political message's language variety, mode of presentation, and humor on users' perceptions and behavioral intentions. The experiments' results indicate that perceptions and behavioral intentions are mainly affected by a political message's presentation as an image macro, while the recontextualization of language variety and humor plays a minor role. The study contributes to the growing body of knowledge on Internet memes as multimodal and recontextualizable political messages from the receivers' point of view.

1. Introduction

Internet memes (in short, memes) and their meanings are essentially constructed by recontextualization practices (Shifman, 2014; Kirner-Ludwig, 2020)—not to say that recontextualization is a “genre constitutive practice” (Gruber, 2019, p. 55) for memes. According to Linell (2009, pp. 144–145) recontextualization is the “dynamic transfer-and-transformation of something from one discourse/text-in-context […] to another”. Recontextualization can be identified through the existence of contextualization cues, which, for example, allow messages to be reinterpreted in subtle ways (Gumperz, 1982). The (linguistic) resources that can be used as contextualization cues to recontextualize messages are seemingly unlimited, ranging from micro-level features, such as phonetic-phonological cues in spoken interactions, to macro-level features, such as certain modalities or the conscious use of varieties via all sorts of grammatical and lexical elements. In this vein, recontextualization involves shifting and is thus, as Kirner-Ludwig (2020, p. 7) describes it for memes, “any act of quoting, with a quoter shifting a source text of their choosing into new context as a target text. Whilst doing so, they channel the source text through a meaning-making process (Gruber, 2019) and (re-)evaluate it in that new context it has been shifted into”. Since this paper is specifically concerned with the perceptions and effects of already recontextualized (political) messages, we refer to the cues that are operationalized for this purpose in this article as (re-)contextualization cues.

The use of certain (re-)contextualization cues is also characteristic of a certain multimodal genre of memes—the so-called image macros. Image macros consist of a static background image, usually from everyday life, pop culture, or politics, which is typically recontextualized by many users through linguistic captions. Variation and recontextualization, however, can take place not only at the level of the linguistic elements but also at the level of the images (e.g., through image editing and photomontages). Taken together, image macros embody many of the appropriative and intertextual practices, such as recontextualization, that are typical of digital communication environments (Huntington, 2020; Pfurtscheller, 2020; Wagner and Schwarzenegger, 2020).

Image macros have also become an integral practice of political engagement in social media (Shifman, 2014; Wagner and Schwarzenegger, 2020). Due to Internet memes' increasing importance in sociopolitical online discourses, a growing body of communication and linguistic research has focused on political memes as vehicles for meaning-making, explicating their multimodal characteristics (Dynel, 2021), their potential for political participation (Ross and Rivers, 2017; Johann, 2022), and their diffusion in social networks (Johann and Bülow, 2019). Although humor—and, in particular, sarcasm (Taecharungroj and Nueangjamnong, 2015)—is often associated with Internet memes, political image macros do not need to involve humor at all, and those that do may communicate serious meanings (Dynel, 2016).

While many studies have begun to grasp the potential of Internet memes, less research has been conducted in the context of their audiences (Huntington, 2020). Thus, this article brings together expertise from linguistics and communication science to investigate the effects, perceptions, and attitudes entangled with the different results of recontextualization practices in political image macros. Hence, this study is not about how recontextualization processes are structured. Rather, it is concerned with the still-open question of how users evaluate various products of common recontextualization practices. Regarding the specific characteristics of image macros, we argue that language, multimodality, and humor represent decisive possibilities for the memetic recontextualization of political online messages. Specifically, taking a quantitative perspective based on an experimental design, we focus on the question of how different results of recontextualization practices by means of various (re-)contextualization cues on the levels of (1) language variety, (2) modality, and (3) humor affect users' perceptions and behavioral intentions. Meme producers might apply (re-)contextualization cues, such as dialect features, to foreground certain aspects of context for interpretation, and recipients use these cues to infer which aspects of context they must make relevant to their inferencing of a plausible interpretation. For example, in the German-speaking area, we know that “Austrian speakers strategically index social meanings attaching to the use of dialect, thus making them relevant to interpretation and the interactional activity of creating and negotiating meaning” (Soukup, 2009, p. 11). In this vein, we consider it particularly fruitful to integrate sociolinguistic insights on language perceptions and attitudes into meme research.

Generally, little is known about how the use of a certain language variety affects human behavior (Heblich et al., 2015)—particularly in the context of dialects in social media artifacts such as political image macros. Therefore, we not only aim to investigate the perception of recontextualized political messages in image macros but also the effects on users' behavioral intentions. Specifically, we focus on the question of how certain (re-)contextualization cues affect the intention to forward political image macros and the political messages' effectiveness, which are core characteristics of online content's memetic success (Shifman, 2014). To tackle this objective, we conducted two between-subjects online experiments testing perceptions and attitudes as well as the intention to forward various adaptations of political image macros. As (re-)contextualization cues, we applied different varieties (Austrian Standard German vs. East Central Bavarian dialect), presentation modes (written plain text vs. image macro), and expressions of humor (sarcastic vs. non-sarcastic) that are known to be used to recontextualize memes. In line with Kirner-Ludwig (2020), we assume that source texts are recontextualized by (re-)contextualization cues establishing new contexts and thereby also undergo re-evaluation in the process of meaning-making.

Next, we first outline theoretical considerations and summarize the state of the research focusing particularly on perceptual- and effect-related aspects of both image macros and language varieties in Austria. Then we present the first online experiment representing a first exploration of the perception and effects of linguistic varieties in political image macros in Austria. The findings from this study will then be broadened in a second online experiment. In addition to the perception and effects of linguistic varieties, this second study deals with the perception and effects of recontextualizing political messages through different presentation modes and aspects of humor that are typical for memes. The overall results of the two studies are jointly discussed and summarized.

2. Literature review and state of research

2.1. Internet memes as recontextualized information

The term “meme” was coined by the evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins, who aimed at describing a form of sociocultural evolution. In this sense, memes “are to culture what genes are to life. Just as biological evolution is driven by the survival of the fittest genes in the gene pool, cultural evolution may be driven by the most successful memes” (Dawkins, 1976, p. 3). Dawkins' (1976) meme concept made it possible to describe the transmission of cultural artifacts that are primarily reflected in human behavior. Over time, the meme concept has evolved, subsuming imitation-based dissemination processes. Specifically, in the era of user-generated content on social media platforms, Internet memes refer to “a group of digital items sharing common characteristics of content, form, and/or stance, which […] were created with awareness of each other, and […] were circulated, imitated, and/or transformed via the Internet by many users” (Shifman, 2014, p. 41). In memes, users intentionally adapt and spread information, making creativity an essential characteristic of meme culture (Wiggings and Bowers, 2015). Their dissemination, for instance, by creating new adaptations and/or forwarding existing adaptations, is not only the reason for but also the ultimate goal of successful transmission.

Looking at the meme concepts' history and various attempts to define Internet memes, imitation is pronounced as the most important mechanism for adapting specific content, forms, or stances. In this sense, memetic is what is “transformed” (Shifman, 2014, p. 41), “imitated” (Shifman, 2014, p. 41; Molina, 2020; p. 392), “recoded” (Nooney and Portwood-Stacer, 2014, p. 249), what users “appropriate, adjust and share” (Denisova, 2019, p. 10), or what is underlying specific “repackaging strategies” (Shifman, 2013, p. 365). Regarding the various ways in which information is adapted on the Internet, we argue that meme producers' practices of multimodal recontextualization are a key strategy in memetic communication. There is broad consensus that the individual adaptation of memes is mainly realized by altering the linguistic elements in order to transfer information into a new context (e.g., Gruber, 2019; Piata, 2019; Kirner-Ludwig, 2020). However, due to the multimodal nature of memes (Huntington, 2020) and their genuine humorous character (Dynel, 2016), recontextualization is also possible with regard to their visual and humorous presentation. These other forms or products of multimodal recontextualization are less researched.

Generally, recontextualization is a communicative strategy aimed at the “dynamic transfer-and-transformation of something from one discourse/text-in-context […] to another” (Linell, 2009, pp. 144–145), and multimodality refers to an information's specific way of presentation. The basic assumptions of multimodality are that communication is genuinely multimodal and that an information's meaning is always constructed multimodally (i.e., that different modes work together requiring specific affordances to unfold meaning) (Jewitt, 2014). In this vein, Milner (2013, p. 2359) described Internet memes as “multimodal symbolic artifacts created, circulated, and transformed by countless meditated cultural participants”. Linking the concepts of multimodality and recontextualization with the functional logic of memes, it can be concluded that memes multimodally display at least one (re-)contextualization cue for interpretation and meaning-making.

The interplay of different modalities, such as language and image, is particularly relevant for the best-known genre of memes: image macros (Shifman, 2014). Image macros usually consist of a static image, typically originating from everyday life, pop culture, or politics. The specific meaning of image macros is constructed through variable linguistic captions. By a meme producer's active selection of a specific image and caption, meaning is constructed multimodally. In other words, altering specific (re-)contextualization cues on the level of the multimodal presentation of information indexes the recontextualization of a meme's meaning. In image macros, multimodal recontextualization can usually be realized through the variation of the image, the language, or the interplay between the image and language, for instance, by using humor.

Based on these considerations, we argue that multimodal recontextualization is an integral strategy in memes in general and in image macros in particular. Through this lens, we define an Internet meme as a collective of multimodal signs that refer to each other through shared formal, content-related, and/or stance-related characteristics and that can be recontextualized at different levels of modality.

2.2. Political Internet memes and memeified politics

Internet memes have become a widely adopted practice in the participatory culture of the Internet, and politics has become crucial for the production and consumption of memes (Shifman, 2014; Wiggings and Bowers, 2015). Consequently, memes have developed from a pure entertainment format into a serious means of social and political deliberation (Denisova, 2019). The low barriers to the production, dissemination, and consumption of memes allow users not only to engage in politics but also to express political opinions or criticism and raise awareness of sociopolitical topics without leaving the virtual space. As young people increasingly rely on low-threshold forms of political engagement (Kim et al., 2016), it is not surprising that memes have become an inherent part of their media repertoires (Lindgren, 2017; Willmore and Hocking, 2017). Here, they represent an innovative and humorous source of political information that complements traditional resources (Cortesi and Gasser, 2015).

By creating a sense of belonging to the community and fostering group relationships as well as collective identity, memes fulfill a social function (Willmore and Hocking, 2017; Denisova, 2019). In this way, Internet memes are mainly used for persuasion or political advocacy, grassroots action, and expression in public discussions in both democratic and nondemocratic settings (Shifman, 2014). Research highlights the memes' potential for users' political participation (Johann, 2022) as well as the mobilization of political movements and activism (Williams, 2020). Overall, the last few years have seen a “memefication of political discourse” (Bulatovic, 2019, p. 250), giving rise to political Internet memes as a widespread genre of online communication (Wiggings and Bowers, 2015).

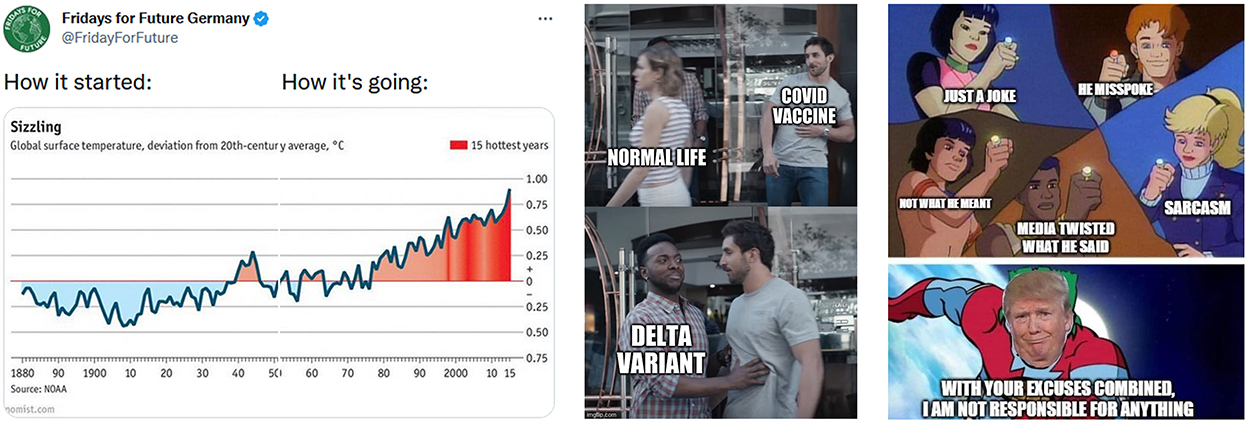

Internet memes are political when they refer to societal interests or conflicts, specific political actors, their acts, or decisions (Johann and Bülow, 2019). From a multimodal point of view, political cues can occur in the image used (e.g., depicting politicians), language (e.g., writing about political topics), or the interplay of image and language (e.g., creating humor through playful visual exaggeration). In this vein, Chagas et al. (2019) provided a typology of political Internet memes, including persuasive memes, grassroots action memes, and public discussion memes. Persuasive memes are mainly used to support political actors by reinforcing their emotional appeal and credibility. When Fridays for Future Germany uses a meme referencing temperature statistics, the movement aims to create evidence-based awareness to support its climate policy (see Figure 1 on the left). Grassroots action memes aim at mobilizing and generating a collective sense by fostering a sense of connective action. For instance, during the COVID-19 pandemic, there was widespread bottom-up support in the memesphere for global vaccination campaigns (see Figure 1 in the middle). Finally, public discussion memes usually use humor (e.g., references to popular culture) to comment on specific political actors and evoke certain reactions or expressions. In the example, a user references a 1990s TV series to criticize former U.S. President Donald Trump (see Figure 1 on the right). While persuasive and grassroots action memes often occur in strategic contexts, such as political advocacy and activism, public discussion memes are less institutionalized. Research indicates that humorous public discussion memes are the predominant type of memes in political contexts (Chagas et al., 2019).

Figure 1. Types of political Internet memes [(left) persuasive meme, source: FridayForFuture (2020); (middle) grassroots action meme, source: MapleSyrupSupremacy (2021); (right) public discussion meme, source: KylieFan_89 (2019)].

Humor has been proven as a decisive strategy to recontextualize political messages in memes (Vicari and Murru, 2020; Glǎveanu and de Saint Laurent, 2021), usually to criticize and discredit political actors (Ross and Rivers, 2017). Therefore, political humor expressed in the meme format can create a public arena on social media where politics can be commented on in a rather pleasant and harmless way (Tsakona and Popa, 2011). Political humor itself is an umbrella term for any humorous content dealing with political actors, issues, events, processes, or institutions (Young, 2014). Mainly relying on contextual knowledge, political humor includes those in the in-group who share this knowledge and excludes those in the out-group. Looking again at the examples in Figure 1, it is obvious that the audience needs a certain degree of scientific, political, and pop cultural knowledge to fully relate to the memes and their inherent political messages. Thus, political memetic humor serves both a transactional function, in that it transmits political information, and an interactional function, in that it separates the informed audience from the uninformed (Tsakona and Popa, 2011). Although several studies have shown that political humor has positive effects on an audience's interest, knowledge, attitudes, and behavior, the understanding of political humor's effects is “far from clear” (Young, 2014, p. 10). Thus, researching the perceptual and behavioral effects of political memes should help to better grasp the complex nature of memetic humor.

Previous research on the application of different types of humor in memes indicates that sarcasm is the most prevalent form of memetic humor (Taecharungroj and Nueangjamnong, 2015). Sarcasm is defined by its goal to cause verbal harm through the use of words to convey a meaning opposite the literal meaning (Dynel, 2014). Sarcasm “provides a more socially acceptable way over direct criticism to elaborate on the negative stereotypes of the out-group and to enhance in-group cohesion by justifying in-group superiority” (Harvey et al., 2019, p. 1020). In this vein, Shifman (2014, p. 143) argued that “memetic responses […] can be seen as the bottom-up, digital incarnations” of classical political satire. Thus, sarcasm in memes can result in harsh mockery, irony, cynicism, or satire, all of which are hard to distinguish concepts of humor or comic style (see, for the implementation of specifying comic style markers, Ruch et al., 2018).

While previous research has extensively studied the effects and perceptions of political humor in domains such as classical political entertainment formats on TV, the effects of political Internet memes have long been neglected. One important attempt to close this gap was made by Huntington (2020), who examined the role of partisanship and the memetic mode of presentation in the perceived effectiveness and quality of political messages. The results of this experimental study provide evidence of partisan perception of memes and the lack of relevance of the specific presentation mode. In contrast, Veerasamy and Labuschagne (2014) emphasized in their framework on meme effectiveness the importance of a message's visual mode to be disseminated and to attract users' attention. Other studies dedicated to the effects of political memes found that the consumption of memes has positive effects on users' political engagement (Zhang and Pinto, 2021; Johann, 2022) and that the memetic presentation of credible information results in higher levels of engagement, such as commenting and sharing political memes (Wasike, 2022). Moreover, studies inside and outside the political context have shown that memes trigger users' emotions and subtle perceptions of the presented messages (Williams et al., 2016; Akram et al., 2020; Gardner et al., 2021) and that humor plays an important role as an enabler of cognitive and affective outcomes (Gardner et al., 2021; Myrick et al., 2021; Wong and Holyoak, 2021).

Overall, previous research indicates that political Internet memes have the potential to stimulate emotional, cognitive, and affective reactions. Although research has begun to pay more attention to the effects of memes, few attempts have been made to integrate the interplay of memetic recontextualization products, such as presentation mode, language variety, and humor. The role of language variety in particular has been treated shabbily, although it is a common practice to recontextualize image macros, especially in constellations where varieties transfer social meaning. For this reason, it seems worthwhile to expand the existing body of research with a more holistic approach to studying the effects of political memes.

2.3. Language perceptions and attitudes in the Austrian language context

There is an extensive body of literature showing that speakers use linguistic cues to socially categorize and stereotype varieties (and their speakers). These stereotypes provide the basis for the emergence of attitudes toward varieties or their single features (Soukup, 2021). For example, in German-speaking areas, various studies of language perceptions and attitudes have demonstrated that speakers consistently evaluate non-standard varieties (e.g., traditional dialects, such as Bavarian) more favorably on measures of warmth or likeability, representing the solidarity dimension of language perception. At the same time, the use of these varieties leads to less favorable assessments of competence (e.g., intelligence and confidence), which are attributed to the status dimension (Soukup, 2009, 2021; Bellamy, 2012). Standard varieties, such as Austrian Standard German, in contrast, are evaluated more favorably on measures of competence and less favorably on measures of friendliness (Soukup, 2009; Bellamy, 2012). These findings hold for most standard languages and non-standard varieties (for a broad review, see Giles and Marlow, 2011, pp. 165–166).

Note that non-standard varieties often carry (covert) prestige. They are highly valued in speech communities or communities of practice in which they form the speech norm. This is especially true for the use of Bavarian dialects in rural Austria. Here, dialect use is still widespread and highly valued. Dialects are used not only in informal settings but also in more formal situations (Lenz, 2019; Vergeiner et al., 2022). Linguistic cues, such as dialect features, do not a priori trigger positive or negative perceptions. Rather, language perceptions are highly dynamic and dependent on context. In addition, social expectations may affect perceptions, as speakers often attend to linguistic cues that are consistent with their expectations of a particular communicative situation. Thus, language perceptions are the result of an active process of sense-making in concrete contexts (e.g., Giles and Rakić, 2014; Heblich et al., 2015), interwoven with and intimately linked to speakers' experiences, prior attitudes, and linguistic knowledge (Levon and Fox, 2014).

With regard to Austria, where, in large parts, a diaglossic language situation1 prevails, the research focus is on the use of as well as the perceptions and attitudes toward Central Bavarian dialects in comparison to standard Austrian German. Thus, in what follows, we summarize what is known about perceptions and attitudes Austrians have toward Standard German and the Central Bavarian dialects. One of the first major studies was conducted by Moosmüller (1991), showing not only that speakers were able to distinguish between dialect features and standard features but also that prototypical East Central Bavarian dialect features are negatively evaluated and stigmatized by informants of all social classes. Soukup (2009) conducted another pioneering study in the Austrian context. The author not only demonstrated that dialect is used as a (re-)contextualization cue in political TV debates, but results from a within-subjects experimental study with 242 participants also indicated that the Central Bavarian dialect is perceived as more natural, honest, emotional, relaxed, humorous, likable, and aggressive than Austrian Standard German. In contrast, Austrian Standard German is perceived as more polite, intelligent, educated, gentle, serious, and refined but also, for example, as more arrogant than the dialect (Soukup, 2009, pp. 114, 127). Follow-up within-subjects studies on language perceptions and attitudes in Austria have largely replicated Soukup's findings (e.g., Bellamy, 2012). These studies show that varieties as (re-)contextualization cues are associated with different evaluations in the East Central Bavarian language area in Austria. A good overview of the complex situation regarding Austrian Standard German is given, for example, by Moosmüller et al. (2015) and Koppensteiner and Lenz (2020, 2021).2

A large part of language perception and attitude research deals with spoken stimuli (so-called “guises”). However, some studies also deal with language perceptions of and attitudes toward written stimuli or stimuli combining written language and images, which is particularly relevant for this study. Stimuli with written and pictorial elements are often applied to examine the perceptions and effects of language choice in advertising.3 Most of these studies (e.g., Gerritsen et al., 2010; Hendriks et al., 2017; Van Hooft et al., 2017) use stimuli that contain a pictorial basis and have been recontextualized to differ only in language choice (e.g., English vs. Dutch) but not in general appearance. For example, Gerritsen et al. (2010) and Hendriks et al. (2017) examine the use of English in product advertisements—such as those found in magazines—in countries in Western Europe (e.g., the Netherlands), where English is not the native language. In contrast, recontextualization through language choice in advertising has hardly been studied in digital environments, such as social networking sites. This also holds true for Central Bavarian, which, from the perspective of strategic use in the sense of language choice, has so far only been studied in offline advertising contexts (Bülow, 2014; Wahl, 2020; Blahak, 2021).

In sum, language perception and attitude research are important to better understand the social dimension of language use. The use of certain varieties or certain linguistic features may affect “social decision-making that can have significant real-world consequences” (Giles and Marlow, 2011, p. 165). To better understand the effetcs of langugage choice, language perception and attitude research has developed techniques to adequately study social associations of different varieties.4 However, little research has been done on both the effects of language perceptions and attitudes toward dialects and standard languages in political contexts in Austria and social media environments. This is especially true for the use of these varieties in political memes, which play an increasingly important role in digital political communication (Johann and Bülow, 2019). Thus, we know very little about the perceptions and effects of recontextualization using different language varieties in political image macros.

3. Users' perceptions of language variety in sarcastic political image macros

Previous findings from language perception and attitude research have shown that East Central Bavarian dialects and Austrian Standard German are perceived differently in Austria and evoke different associations in multimodal settings (Soukup, 2018, 2021). However, no research has been conducted on how different language varieties are perceived in digital political contexts, such as political image macros. Thus, we conducted the first online experiment to explore the effects on perceptions and behavioral intentions of recontextualized political messages through different language varieties (Austrian Standard German and East Central Bavarian dialect) in image macros.

Specifically, as political Internet memes usually use sarcasm to express political criticism (Taecharungroj and Nueangjamnong, 2015), we examined how sarcastic political image macros in Austrian Standard German or East Central Bavarian dialect are perceived by young adolescents. The focus of both studies is on young adolescents, as they have deeply integrated political memes into their information and communication repertoires (Lindgren, 2017; Willmore and Hocking, 2017). As there has been a lack of research on this topic thus far, we investigate the following research question:

RQ1: How do the participants perceive different language varieties in sarcastic political image macros?

As little is known about how the use of certain varieties or languages affects behavioral outcomes in social media contexts, we also aimed to study how recontextualization through different language varieties affects the participants' behavioral intentions. Behavioral intention refers to “the degree to which a person has formulated conscious plans to perform or not perform some specified future behavior” (Warshaw and Davis, 1985, p. 214). We particularly focus on the intention to forward messages, as the circulation of individually adapted memes and the sharing of existing meme adaptations are crucial practices for the diffusion of Internet memes and memetic success (Shifman, 2014; Johann and Bülow, 2019). Forwarding can be realized, for instance, by sharing or reposting memes on social media platforms. These can then, in turn, serve as templates for imitation and adaptation by other users. Based on these considerations, we pose the following research question:

RQ2: How do different language varieties affect the participants' intentions to forward sarcastic political image macros?

3.1. Methods study I

The research question was examined using a single-factor experimental design (Austrian Standard German vs. East Central Bavarian dialect). The study was conducted between 22 February and 21 March 2021 using an online questionnaire. The initial sample consisted of 273 teacher training students from the universities of Vienna and Salzburg, of which 64 participants could not be included in the analysis because they aborted the online survey or because their first language was not German.5 Consequently, the final sample consisted of 209 participants between 18 and 41 years of age (M = 24.00, SD = 3.92), largely sharing the same sociocultural background. Female participants predominated, making up 79% (n = 164) of the sample compared to 20% (n = 42) of male participants, 1% (n = 3) of the participants identified themselves as non-binary.

We tested six pairs of so-called public discussion memes (Chagas et al., 2019) that transport criticism on different political issues in Austria. Each pair shows an image of Sebastian Kurz (see Figure 2), the Austrian chancellor at that point in time, and a political message in a sarcastic tone.6 We used mockery, irony, cynicism, and/or satire markers for the design of the sarcastic messages (Dynel, 2014; Ruch et al., 2018). For instance, we formulated paradox constellations to mark irony (see Figure 2 on the left, on the right) or integrated rhetorical questions to point out the satirical character of the presented situation (see Figure 2 on the second left). The stimuli pairs differ only in that one variant presents the linguistic message in standard, while the other uses dialect (displaying regional dialect features). In other words, the presented political message was recontextualized through means of language variety. In the end, each participant was exposed to six political image macros, either in Austrian Standard German (Group 1, n = 105) or in the East Central Bavarian dialect (Group 2, n = 104).

Figure 2. Stimuli used in study I [(top row) Austrian Standard German; (bottom row) East Central Bavarian dialect; from left to right: Adaptation A1, A2, A3, A4, A5, A6].

Language perceptions were measured using semantic differential items based on Soukup (2018; for the implementation of this task in social psychology, see Lambert et al., 1960). The participants were asked to evaluate only the language (“I find the language of the meme…”) on 5-point bipolar semantic differential scales using nine opposing pairs of adjectives (“likable”—“not likable”; “funny”—“not funny”; “modern”—“not modern”; “trustworthy”—“not trustworthy”; “attractive”—“not attractive”; “emotional”—“not emotional”; “beautiful”—“not beautiful”; “natural”—“not natural”; and “intelligent”—“not intelligent”).

Meme perception was also measured using semantic differentials (Soukup, 2018). The participants were asked to evaluate the presented image macro as a whole (“I find the meme as a whole…”) on 5-point bipolar semantic differential scales using eight adapted pairs of adjectives (“likable”—“not likable”; “funny”—“not funny”; “modern”—“not modern”; “trustworthy”—“not trustworthy”; “attractive”—“not attractive”; “emotional—not emotional”, “successful”—“not successful”; “creative”—“not creative”; and “convincing”—“not convincing”).

The participants' intentions to forward were measured by a single item on a 5-point scale indicating whether they would “forward” or “not forward” the presented image macro adaptation.

3.2. Results study I

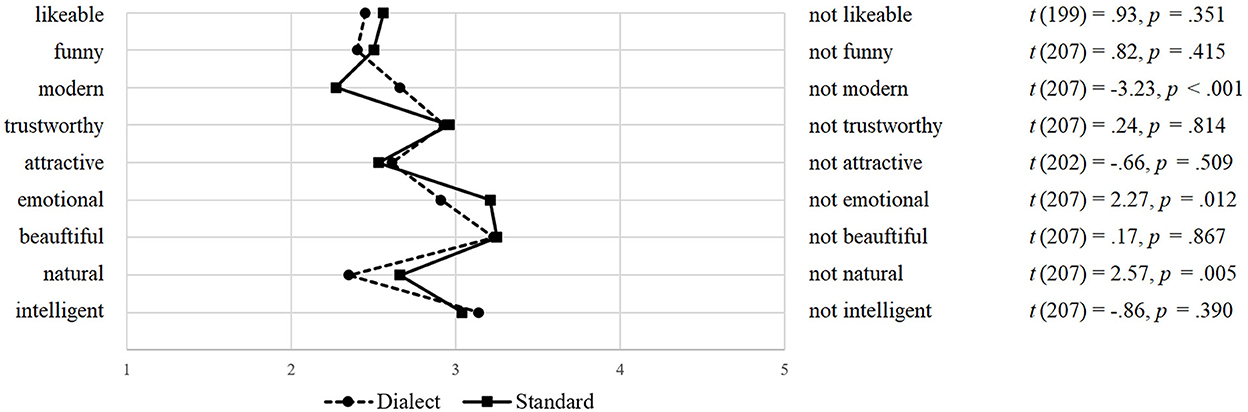

The mean values for the six meme adaptations were aggregated and compared using t-tests. As the data sets also included missing data (e.g., single unanswered items), the t-tests showed various degrees of freedom. Overall, the level of missing data was low. First, we asked how the language variety presentend in the image macros was perceived (RQ1). The results show three significant differences (see Figure 3). Dialect is perceived as less modern but more emotional and natural than Austrian Standard German. For the other six pairs of adjectives tested, there were no significant differences in the participants' perceptions.

Second, to test multimodal recontextualization effects, we wanted to determine how the entire political image macros are perceived depending on their respective language variety. Here, the results indicate that there is no significant difference in the perception of image macro adaptations in dialect and standard (see Figure 4). Consequently, language recontextualization does not seem to play a role when it comes to the evaluation of political image macros as a whole.

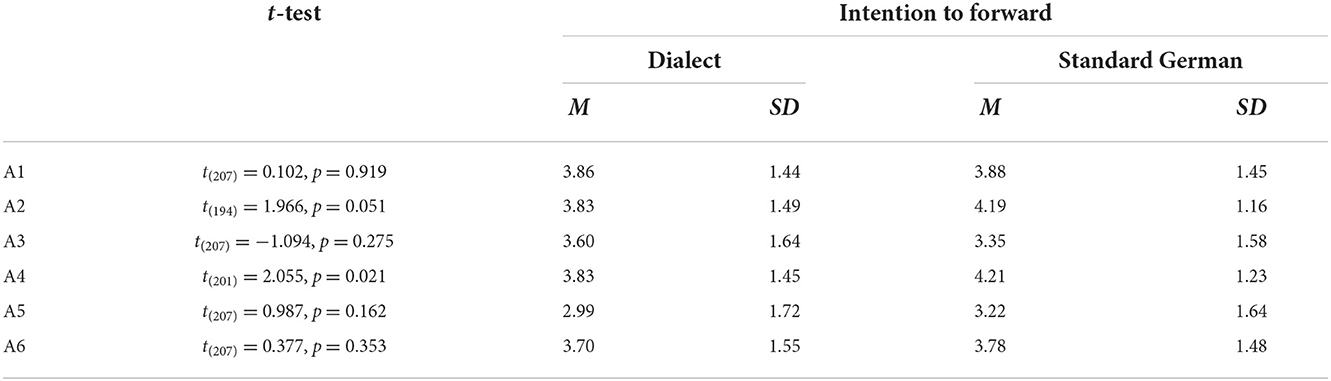

We also wanted to explore the participants' intentions to forward the various political image macro adaptations (RQ2). As presented in Table 1, most adaptations did not differ significantly in the respondents' intentions to forward. Only adaptation 4 received significantly different scores, indicating that the adaptation recontextualized in dialect is more likely to be forwarded than the adaptation in Austrian Standard German. However, we cannot confirm the overall effect of recontextualization through language variety in political image macros.

3.3. Discussion study I

This study offers the first attempt to explore language perceptions and recontextualization effects through different language varieties in sarcastic political image macros. In contrast to what we know from previous results, this study indicates that recontextualization by language variety does not significantly influence the perception of sarcastic image macros. Rather, it turned out that the image macro adaptations were rated very similarly for all semantic differential items, regardless of whether the linguistic message was presented in dialect or standard language.

However, looking at the language perceptions in the presented political image macros only, we observed some significant differences between the East Central Bavarian dialect and Austrian Standard German. While the dialect is perceived as more natural and emotional, the use of standard language is rated as more modern. These results are not surprising and largely consistent with previous findings in which Bavarian dialects have an edge over standard German varieties regarding “affect”-related scores on the solidarity dimension of language perceptions, such as emotionality and naturalness, and the standard German varieties are rated higher for the prestige- or status-dimension (modernness) (Soukup, 2009, 2018, 2021). What is more surprising is that no significant differences are found for the other tested adjective pairs, such as “intelligent vs. not intelligent” or “likable vs. not likable,” which have been shown in previous studies to be susceptible to differences in perception (Soukup, 2009, 2018, 2021; Bellamy, 2012).7 The differences could be explained by the fact that our study used a between-subjects design (i.e., the participants were only exposed to the stimuli in dialect or standard). Previous matched guise studies have always used within-subjects designs in which the participants rated all the language variety conditions. Thus, it was always possible for these participants to compare the dialect and the standard language directly with each other, which was not possible with our study design. Although participants in within-subjects designs usually function as their own controls, there is a lack of independence of the stimuli used, leading to undesired effects on the dependent variables (Keren and Lewis, 1993). In this way, previous matched guise designs relying on within-subjects designs might have caused sensitization effects among the participants, leading them to generate their hypotheses about language variety effects and biased perceptions (Greenwald, 1976). We argue that between-subjects designs offer advantages in terms of internal validity to isolate the language variety perception effects in sarcastic political image macros.

Furthermore, in previous studies, speakers were assessed using the matched or verbal guise technique. In the present study, in contrast, it is rather utterances that were assessed. Hence, more speaker-related characteristics, such as intelligence or likeability, may play only a minor role because the test items could not be assigned to specific social characteristics of the speakers, such as gender. In traditional matched and verbal guise studies, gender, in particular, is an important factor (Strand, 1999; Soukup, 2001, 2009). In the design used here, the participants had no further information about the meme producer. Thus, our stimuli were gender neutral to control for the influence of this factor. However, this might also explain the possible differences from previous studies.

The fact that we obtained no differences in the perceptions of the image macros as a whole indicates that recontextualization through variety plays no or only a minor role for the participants. This is also reflected in the finding that recontextualization by language variety does not influence the intention to forward image macro adaptations. Hence, because recontextualization through language variety does not seem to be the decisive factor in the perception and effects of political image macros, the notion of recontextualization practices in these artifacts needs to be further investigated regarding other recontextualization practices. In the following study, we will therefore take a closer look at the factors of modality and humor.

4. Users' perceptions and effects of multimodal recontextualization of political messages

To investigate users' perceptions and effects of multimodal recontextualization in political image macros in more detail, we conducted a second online experiment. To further consider the effects of recontextualized political messages as well as the persuasive power of multimodality (Huntington, 2020) and humor (Taecharungroj and Nueangjamnong, 2015; Dynel, 2016) in image macros, we varied the humorous nature of the presented political message (sarcastic vs. non-sarcastic) and its mode of presentation (plain text vs. image macro). Similar to the first study, we also varied the language variety (Austrian Standard German vs. East Central Bavarian dialect), resulting in a 2 × 2 × 2 experimental design. Regarding the dependent variables, we again investigated the present messages' relations to the perceptions of language variety (Soukup, 2018, 2021) as well as the participants' intentions to forward the message (Shifman, 2014; Johann and Bülow, 2019). As we approached recontextualization from a more holistic perspective in the second study, focusing on the different possibilities of recontextualizing a political message, we also investigated relations to the participants' perceived message effectiveness (Kang and Cappella, 2008).

Regarding the factor of humor, research has shown that especially humorous content is more likely to be forwarded online (Golan and Zaidner, 2008). Therefore, it was expected that sarcastic messages in political image macros would be perceived as more effective and are more likely to be forwarded than political image macros without sarcasm:

H1: Image macros with sarcastic messages are perceived as more effective than image macros without sarcasm.

H2: Image macros with sarcastic messages are more likely to be forwarded than image macros without sarcasm.

Given the persuasive impact of multimodality in political image macros (Huntington, 2020), it was further assumed that sarcasm in image macros is perceived as more effective and is more likely to be forwarded than sarcasm in plain text messages:

H3: Sarcastic messages presented as image macros are perceived as more effective than sarcastic plain text messages.

H4: Sarcastic messages presented as image macros are more likely to be forwarded than sarcastic plain text messages.

The effectiveness of messages and the willingness to forward them might also be affected by using a certain language variety. The use of a (written) dialect in online contexts often signals identity and membership in a particular community of practice, sharing common values and attitudes (Meyerhoff and Strycharz, 2013). Thus, it is expected that sarcastic messages in political image macros formulated in the participants' dialect (East Central Bavarian) are perceived as more effective and are more likely to be forwarded than political image macros in standard language:

H5: Image macros with sarcastic messages formulated in the participants' dialect are perceived as more effective than image macros in standard language.

H6: Image macros with sarcastic messages formulated in the participants' dialect are more likely to be forwarded than image macros in standard language.

Finally, in accordance with the first study, we are interested in the effects of memetic recontextualization products. As recontextualization solely through language variety has been proven not to affect the participants' perceptions in the first study, we not only ask for the overall message perception, but specifically for the perception of recontextualization by language variety, mode of presentation, and sarcasm:

RQ3: How do participants perceive the recontextualized (language variety, humor, mode of presentation) political messages?

4.1. Methods study II

We conducted a second online experiment to examine the hypotheses and the research question (2 × 2 × 2 between-subjects experiment). The study was carried out between 31 May and 24 June 2021 using an online questionnaire. Again, the sample consisted of students from the universities of Vienna and Salzburg (n = 279). Although different students participated in the second study than in the first study, the two samples are similar regarding the participants' ages ranging from 18 to 40 years (M = 24.03, SD = 4.05) and gender distribution (79% females, n = 219; 20% males, n = 57; 1% non-binary, n = 3).

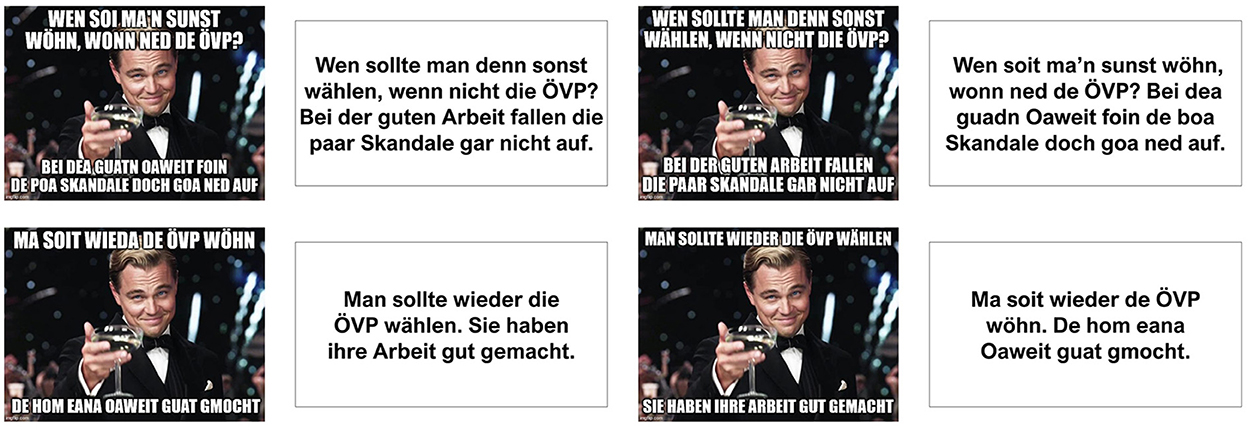

In the second study, we presented only one stimulus to the participants (see Figure 5). Either the stimulus contained a sarcastic or a non-sarcastic political message, which was either presented in Austrian Standard German or the East Central Bavarian dialect and was either embedded in an image macro or shown as written plain text. In this way, we recontextualized the presented political message on politics in Austria in different multimodal facets that are typical of political image macros. Similar to the first study, we used mockery, irony, cynicism, and/or satire as indicators for sarcasm. In total, we presented eight stimuli, resulting in eight experimental groups (nA2 = 33; nA2 = 34; nA3 = 39; nA4 = 34; nA5 = 35; nA6 = 35; nA7 = 33; and nA8 = 36). Both the sarcastic and non-sarcastic messages deal with politics in Austria related to the ÖVP (“Austrian People's Party”), representing the governing party at that point in time.8 Similar to the first study, we used public discussion memes to create political image macros (Chagas et al., 2019). The pictorial basis of the image macros is the well-known template “Great Gatsby Reaction” from the Hollywood movie “The Great Gatsby” (Luhrmann, 2013) (https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/great-gatsby-reaction-leonardo-dicaprio-toast) showing the actor Leonardo di Caprio toasting. Plain text messages were presented as black text on a white background. By varying language variety, humor, and mode of presentation, we aimed to test the effects of recontextualized political messages. In this vein, the stimuli represent prototypical products of common recontextualization practices in political image macros.

Figure 5. Stimuli used in study II [(top row) sarcastic messages from left to right: A1, A2, A3, A4; (bottom row) non-sarcastic messages from left to right: A5, A6, A7, A8].

Overall message perception was measured with the same semantic differentials we used in the first study (adapted from Soukup, 2018). To measure message effectiveness, we adapted three items from Kang and Cappella (2008). The respondents had to express their agreement on a 5-point scale from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”) to the statements: “I found this message persuasive,” “I did not find this message convincing” (reverse-coded), and “I think people different from me would find this message persuasive” (α = 0.76). Intention to forward was measured by two items adapted from Chiu et al. (2007). On a 5-point scale from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”), the respondents indicated their agreement with the following statements: “This message is worth sharing with others” and “I will recommend this message to others” (α = 0.93).

4.2. Results study II

We used ANOVA to test the differences between the experimental groups. Again, there were single missing answers in the data regarding why degrees of freedom differ slightly. The first pair of hypotheses tested the relevance of recontextualization through sarcasm in political image macros. Here, only image macro adaptations were considered in the analysis (n = 140), as we expected that image macros with sarcastic messages are perceived as more effective (H1) and are more likely to be forwarded (H2) than image macros without sarcasm. Overall, image macros with sarcasm recontextualized in dialect (M = 2.78, SD = 0.63) scored similar mean values in terms of perceived message effectiveness as sarcastic image macros in Austrian Standard German (M = 2.79, SD = 0.63) as well as non-sarcastic image macros in dialect (M = 2.81, SD = 0.60) and Austrian Standard German (M = 2.81, SD = 0.35). The ANOVA revealed no significant differences between sarcastic and non-sarcastic image macro adaptations in terms of message effectiveness [F(3,135) = 0.03, p = 0.994].

Similarly, there were no significant differences between the tested image macros with regard to the participants' intentions to forward the memes [F(3,135) = 1.93, p = 0.127]. Moreover, the results indicate that recontextualization through language variety does not affect the results. Consequently, hypotheses H1 and H2 must be rejected.

The second pair of hypotheses was concerned with the recontextualization effects of presentation mode. Specifically, we expected that sarcastic messages presented as image macros would be perceived as more effective (H3) and are more likely to be forwarded (H4) than sarcastic plain text messages. Only cases with sarcastic messages were included (n = 140). Sarcastic image macros in dialect (M = 2.78, SD = 0.63) as well as in Austrian Standard German (M = 2.79, SD = 0.63) scored higher mean values than sarcastic plain text messages in dialect (M = 2.33, SD = 0.69) and sarcastic plain text messages in Austrian Standard German (M = 2.52, SD = 0.56). The ANOVA indicated significant differences [F(3,136) = 1.71, p = 0.006]. A post hoc analysis using Bonferroni corrections revealed that sarcastic image macros in dialect significantly differ from sarcastic plain text messages in dialect (p = 0.028). There were also significant differences between sarcastic plain text messages in dialect and sarcastic image macros in standard language (p = 0.014).

Regarding the participants' intentions to forward, the results reveal similar findings. Sarcastic image macros in dialect (M = 1.89, SD = 1.07) and Austrian Standard German (M = 1.74, SD = 1.00) reached higher mean values than sarcastic plain text messages in dialect (M = 1.18, SD = 0.44) and Austrian Standard German (M = 1.41, SD = 0.86). The ANOVA indicated significant differences [F(3,136) = 4.64, p = 0.004], which were further identified using post hoc tests with Bonferroni corrections. While sarcastic image macros in dialect significantly differ from sarcastic plain text messages in dialect (p = 0.006), sarcastic image macros in standard language also differ from sarcastic plain text messages in dialect. Taken together, hypotheses H3 and H4 can be partially confirmed. Sarcastic image macros differ only from sarcastic plain text messages when plain texts are written in dialect.

Finally, the third pair of hypotheses was dedicated to the effects of language recontextualization in political image macros. In this regard, we expected that image macros with sarcastic messages formulated in dialect were perceived as more effective (H5) and were more likely to be forwarded (H6) than sarcastic image macros in standard language. To test the hypotheses, we included only interventions with sarcastic image macros (n = 72). Regarding message effectiveness, sarcastic image macros in dialect (M = 2.78, SD = 0.63) reached similar scores as sarcastic image macros in Austrian Standard German (M = 2.79, SD = 0.63). A t-test indicated no significant difference between the two groups [t(70) = −0.11, p = 0.909]. In a similar vein, we could not observe significant differences between sarcastic image macros in dialect (M = 1.89, SD = 1.07) and Austrian Standard German (M = 1.74, SD = 1.00) with regard to the participants' intentions to forward the presented adaptations [t(70) = 0.62, p = 0.539]. Considering these findings, we reject hypotheses H5 and H6. Recontextualization through language variety in political image macros does not lead to significant effects.

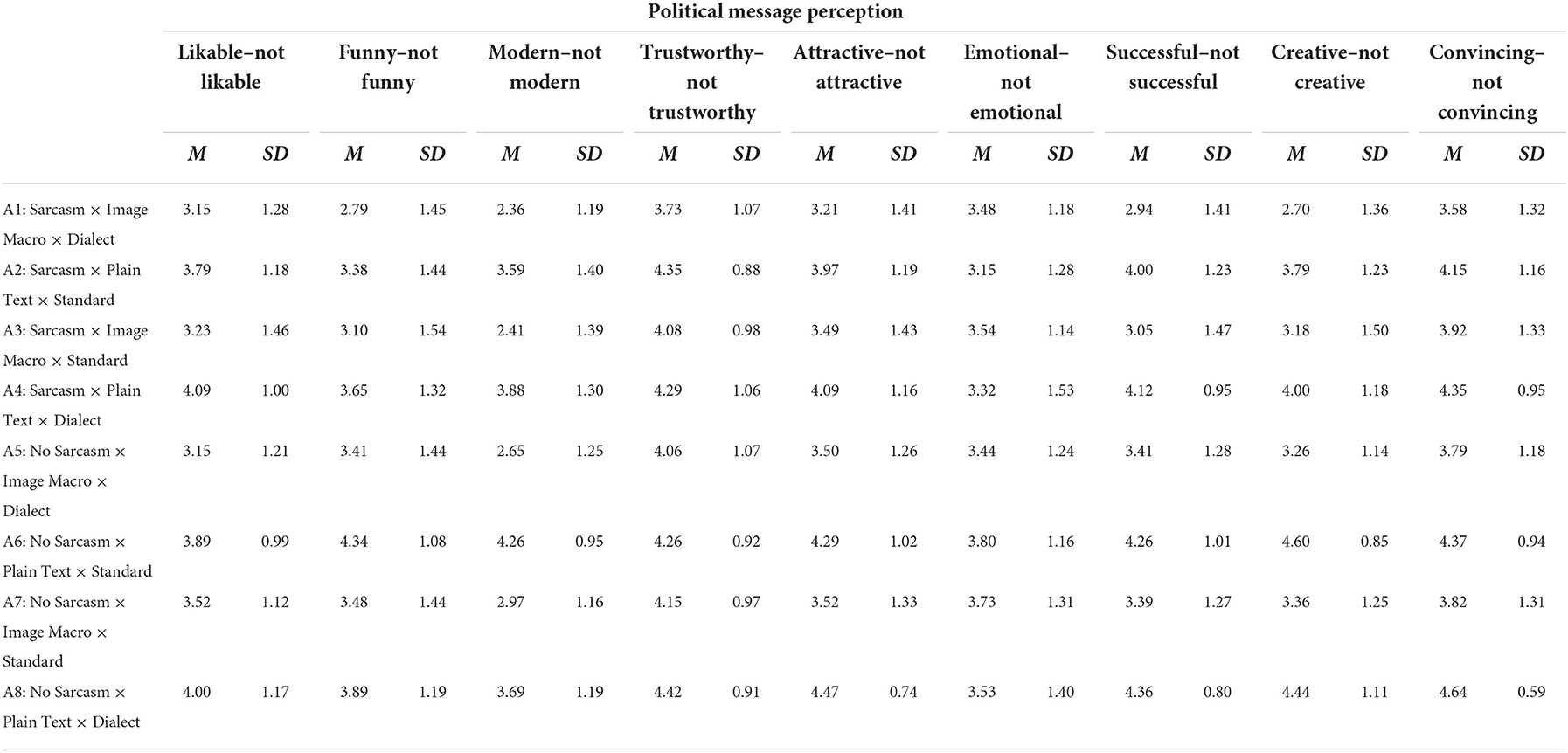

In addition to the presented recontextualization effects on perceived message effectiveness and the participants' intentions to forward, we asked how political messages are perceived depending on their specific recontextualization through sarcasm, presentation mode, and language variety (RQ3). Table 2 provides an overview of the meme perception scores.

We used ANOVA to test whether the different recontextualization products were related to political message perception. The data indicated that there were significant differences regarding the messages' perceptions as likable [F(7,270) = 3.76, p < 0.001], funny [F(7,270) = 4.16, p < 0.001], modern [F(7,270) = 11.95, p < 0.001], attractive [F(7,270) = 4.79, p < 0.001], successful [F(7,270) = 7.65, p < 0.001], creative [F(7,270) = 10.17, p < 0.001], and convincing [F(7,270) = 3.55, p = 0.001]. There were no differences in the participants' ratings as trustworthy [F(7,270) = 1.67, p = 0.115] or emotional [F(7,270) = 0.90, p = 0.509].

Post hoc tests with Bonferroni corrections revealed significant differences between the different recontextualizations in political messages and the particular perceptual dimensions. In this way, we observed that messages recontextualized as sarcastic image macros in dialect are more likable than sarcastic plain text messages in standard language (p = 0.040). Moreover, sarcastic plain text messages in dialect were less likable than non-sarcastic image macros formulated in dialect (p = 0.035).

When it comes to the messages' perceived funniness, the data revealed that messages in dialect with a sarcastic image macro format were significantly rated funnier than non-sarcastic plain text messages in dialect (p = 0.027) and standard language (p < 0.001). In addition, sarcastic image macros in standard language were perceived as funnier than non-sarcastic plain text messages in standard language (p = 0.004).

In terms of the messages' perception as modern, sarcastic image macros in dialect prove to be seen as more modern than sarcastic plain text messages in dialect (p < 0.001) and standard language (p = 0.002) as well as non-sarcastic plain text messages in dialect (p < 0.001) and standard language (p < 0.001). Similarly, sarcastic image macros using standard language were perceived as more modern than sarcastic plain text messages in dialect (p < 0.001) and standard language (p = 0.002) as well as non-sarcastic plain text messages in dialect (p < 0.001) and standard language (p < 0.001). Sarcastic plain text messages in dialect were rated less modern than non-sarcastic image macros in dialect (p < 0.001). Non-sarcastic image macros in dialect were seen as more modern than non-sarcastic plain text messages in dialect (p = 0.013) and standard language (p < 0.013). In addition, non-sarcastic image macros in standard language were rated more modern than their adaptation as plain text (p < 0.001).

When it comes to the political messages' perception as attractive, sarcastic image macros in dialect prove to be more attractive than non-sarcastic plain text messages in dialect (p < 0.001) and standard language (p = 0.009). Sarcastic image macros in standard language were also rated as more attractive than non-sarcastic plain text messages in dialect (p = 0.014). Non-sarcastic image macros in standard language were also more attractive to the participants than non-sarcastic plain text messages in dialect (p = 0.033).

When the participants had to rate whether they perceived the recontextualization as successful, the data indicated some major differences between the single political messages' adaptations. Sarcastic image macros in dialect were rated as more successful than sarcastic plain text messages in dialect (p = 0.002) and standard language (p = 0.010) as well as non-sarcastic plain text messages in dialect (p < 0.001) and standard language (p < 0.001). Sarcastic image macros in standard language were also seen as more successful as sarcastic plain text messages in dialect (p = 0.005) and standard language (p = 0.024) as well as non-sarcastic plain text messages in dialect (p < 0.001) and standard language (p < 0.001). Non-sarcastic image macros in dialect tended to be more successful than non-sarcastic plain text messages in dialect (p = 0.030). Finally, non-sarcastic image macros in standard language were rated as more successful than non-sarcastic plain text messages in dialect (p = 0.026).

Regarding perceived creativity, the data revealed similar findings. Sarcastic image macros in dialect tended to be rated as more creative than sarcastic plain text messages in dialect (p < 0.001) and standard language (p = 0.008) as well as non-sarcastic plain text messages in dialect (p < 0.001) and standard language (p < 0.001). Moreover, sarcastic image macros in standard language were rated as more creative than non-sarcastic plain text messages in dialect (p < 0.001) and standard language (p < 0.001). We also observed that non-sarcastic image macros in dialect were evaluated as more creative than non-sarcastic plain text messages in dialect (p = 0.002) and standard language (p < 0.001). Non-sarcastic image macros in standard language were also perceived as more creative than non-sarcastic plain text messages in dialect (p = 0.008) and standard language (p = 0.001).

Finally, sarcastic image macros were seen as more convincing than non-sarcastic plain text messages formulated in dialect (p = 0.003). Other differences in terms of persuasiveness could not be observed.

4.3. Discussion study II

The aim of the second study was a deeper investigation of recontextualization in image macros beyond language variety. Other factors might also influence users' perceptions and behavioral intentions. Therefore, we examined the effects of recontextualization products on message effectiveness and the intention to forward in three ways: by varying the humorous nature of the message (sarcastic vs. non-sarcastic), by the choice of linguistic variety (Austrian Standard German vs. East Central Bavarian dialect), and by changing the presentation mode (image macros vs. written plain text). As in the first study, we wanted to know how differently recontextualized stimuli are perceived. Consequently, we tested three pairs of hypotheses, taking message effectiveness and intention to forward into account, and examined one research question, that asked for the perception of recontextualized political messages.

For hypotheses H1 and H2, we expected that sarcastic political image macros would be perceived as more effective and are more likely to be forwarded than non-sarcastic political image macros. Ultimately, the results show no significant differences between sarcastic and non-sarcastic adaptations regarding both message effectiveness and intention to forward, which is why we must reject hypotheses H1 and H2. The distinction between sarcastic and non-sarcastic image macros also does not influence the perceptual dimension. There are no significant differences between sarcastic and non-sarcastic image macros regarding semantic differentials. Therefore, we conclude that recontextualization by sarcasm has no influence on perception, message effectiveness, or the willingness to forward political image macros.

We also must reject hypotheses H5 and H6, in which we expected that sarcastic messages in political image macros using the participants' dialect are perceived as more effective and are more likely to be forwarded than in standard language. The results indicate that recontextualization through language variety does not lead to significant effects. This is largely consistent with the findings of the first study, for which no significant influence on the intention to forward through recontextualization by linguistic variety was found. In addition, for the distinction between sarcastic image macros using dialect or standard language, the perceptual dimension did not show any significant results. We thus conclude that recontextualization by language variety does not affect the perception, message effectiveness, and intention to forward sarcastic political image macros.

In contrast, the analyses' results partly support hypotheses H3 and H4, in which we tested the recontextualization effects of different presentation modes. We expected that sarcastic messages presented as image macros are perceived as more effective and are more likely to be forwarded than sarcastic written plain text messages. For both measures, it shows that sarcastic image macros significantly differ from sarcastic plain text messages when the plain texts are written in dialect (i.e., sarcastic image macros in dialect and Austrian Standard German significantly differ from sarcastic plain text messages in dialect but not in standard language). Thus, when a sarcastic political message is presented as plain written text, recontextualization by language variety does not make a difference. However, if language variety varies in image macros, the message effectiveness and the intention to forward sarcastic political messages are enhanced. These findings extend previous research (Veerasamy and Labuschagne, 2014; Huntington, 2020), suggesting that the effects of multimodal recontextualization in memes are complex and cannot be reduced to one single factor.

These effects are also partly evident at the perceptual level for the semantic differentials tested (RQ3). Sarcastic image macros in dialect are perceived as more modern, successful, and creative than sarcastic plain text messages in dialect. Furthermore, sarcastic image macros in standard language are more modern and successful than sarcastic plain text messages in dialect. Thus, we conclude that recontextualization by different presentation modes affects perception, message effectiveness as well as intention to forward sarcastic political messages. Furthermore, it seems that these effects are influenced by the choice of variety; for example, the participants rate the message effectiveness of sarcastic plain text messages in dialect as being weaker. Furthermore, sarcastic plain text messages in dialect are more likely not to be forwarded compared to the sarcastic plain text message in standard language (stimulus A4) and compared to the sarcastic image macros in dialect and Austrian Standard German (stimuli A1 and A3). This means, for example, for strategic communication, that the recontextualization of a political message through Bavarian dialect features is especially effective for image macros.

In addition, the results on the perception of the stimuli reveal some other interesting results. It shows, for example, that sarcastic image macros in dialect are perceived as more likable, modern, successful, and creative than sarcastic plain text messages in standard language.

What ultimately causes the perceptual differences cannot be answered. However, a comparison of the stimuli shows that image macros are generally considered more modern and successful, regardless of linguistic variety. From what we know from matched guise studies (Soukup, 2009; Bellamy, 2012), it would have been expected that the stimuli in standard language would be rated as more modern and successful compared to the dialect. Since the opposite is partly the case, it can be assumed that the perception of image macros as more modern and successful is caused by the specific multimodal genre of image macros. To what extent the specific template plays a role in this must remain open and needs to be considered in follow-up studies. Considering that image macros as a genre are still a fairly young online phenomenon that is also gaining in importance in political contexts (Bülow and Johann, 2019; Wagner and Schwarzenegger, 2020), it is plausible to assume that political messages in this format are evaluated as more modern and more successful, especially in online experiments. This also fits with our finding that messages in image macros are perceived as more convincing than plain text messages.

5. Overall discussion

As little research has been done in the context of memes' audiences (Huntington, 2020), the central aim of this paper was to investigate how different results of recontextualization practices affect the perceptions and effects of political Internet memes in Austria. Considering their memetic nature, we not only defined Internet meme as a collective of multimodal signs that refer to each other through shared formal, content-related, and/or stance-related characteristics and that can be recontextualized at different levels of modality, but we also argued that recontextualization is an integral strategy and “genre constitutive practice” (Gruber, 2019, p. 55) in (political) image macros. Thus, in conducting two online experiments, we focused on the question of how recontextualization through (1) language variety (Austrian Standard German vs. East Central Bavarian dialect), (2) presentation mode (written plain text vs. image macro), and (3) humor (sarcastic vs. non-sarcastic) affects users' perceptions of political image macros and their behavioral intentions.

While we measured language and meme perception using semantic differentials, the results on behavioral intentions (Warshaw and Davis, 1985) are based on measures of the intention to forward and the message effectiveness. The (re-)contextualization cues correspond to important resources that can be varied by users in the context of political image macros. They can be adhered to as meme creators “in order to create intertextuality on multiple levels through recontextualizing implicit and explicit references to telecinematic and pop cultural sources and various items of culturally shared as well as non-shared knowledge within a target political frame” (Kirner-Ludwig, 2020, p. 31). From our perspective, the (re-)contextualization cues tested provide the foundations for a model of multimodal recontextualization in image macros, including language, mode of presentation, and humor. However, the development of such a model—even if the first steps are made (Kirner-Ludwig, 2020)—is still a major desideratum for future research.

Surprisingly, recontextualization through linguistic variety does not turn out to be a decisive factor in the perception of political image macros in either study. Even though the linguistic varieties per se were partially evaluated differently in the first study (dialect was evaluated as less modern, but more emotional and natural than Austrian Standard German), no significant differences emerged at the meme level, which is why the use of linguistic variety in political image macros is not crucial from a strategic perspective, unless—as the second study suggests—the sarcastic effect in image macros is to be emphasized. However, we found no evidence that our participants made language variety relevant for meaning-making when evaluating the image macros as a whole. This is also reflected in the finding that recontextualization by language variety does not influence the intention to forward or the message effectiveness of image macro adaptations. Even though no significant influence can be demonstrated at the level of language variety, the result is important in that it contributes to the body of the few studies (e.g., Zhoa and Liu, 2021) that have so far looked at the perception and effects of standard and non-standard varieties in social media contexts.

The second study revealed that other (re-)contextualization cues' influence political messages' perception and the receivers' behavioral intentions. We showed that the mode of presentation influences users' perceptions of political messages. Written plain text messages are less likely to be forwarded and less effective than image macros. Although previous research did not find any effects of the presentation mode in memes (Huntington, 2020), our study suggests that multimodal meaning-making needs a more holistic approach. It is well known from advertising (e.g., Childers and Houston, 1984; Seo, 2020) and communication research (e.g., Abraham, 2009; Veerasamy and Labuschagne, 2014) that pictorial elements (in combination with written language) have a particular persuasive power and lead to deeper reflections of the presented messages. This also seems to be constitutive of political image macros in this study, suggesting that the interplay of different (re-)contextualization cues can lead to perceptual and behavioral effects.

Humor has also been expected to unfold effects in political message recontextualization. Surprisingly, the second study indicated that humor is not a significant factor when it comes to the evaluation of message effectiveness and the intention to forward the presented messages. This might be explained by the fact that memes are subject to biased cognitive processing, in particular for “selective judgment or motivated skepticism, in viewers' processing of political internet memes” (Huntington, 2020, p. 204). Thus, future research on political image macros should emphasize the question of partisan motivated reasoning (Bolsen et al., 2014; Huntington, 2020). As social media often reflects both users' social networks and mass media information, it has qualities of what O'Sullivan and Carr (2018, p. 1161) call “masspersonal communication”. Given that memes widely circulate within personal networks on social media, users are selectively exposed “to memes which reinforce their own views” (Huntington, 2020, p. 204). In contrast, McLoughlin and Southern (2021) found that there is a high degree of incidental exposure to political memes on social media, suggesting that users might also be exposed to memes that contradict their own views or that they simply don't understand. This emphasizes the relevance of meme literacy (Lankshear and Knobel, 2019) to fully unpack a political meme's message. Therefore, to enhance the understanding of recontextualization by (re-)contextualization cues triggering motivated reasoning in political image macros, future research may also wish to better explore the cognitive processes of judgment in the context of incidental and selective exposure.

From a methodological point of view, this study offers an experimental approach to the perception and effects of political image macros. While previous studies have mainly conducted within-subjects designs to test differences in language perception (Soukup, 2009; e.g., Bellamy, 2012), we argue that a between-subjects design, as presented in this paper, is better suited to isolate perceptual effects, as sensitization effects and consecutive biased perceptions can be avoided (Greenwald, 1976). However, this study also has some limitations, mainly rooted in its methodological approach. For instance, in both studies, we used stimuli that criticized Austria's chancellor and governing party in a sarcastic way. As partisanship is an important factor when it comes to the evaluation of political memes (Huntington, 2020), this might also be an experimental factor to consider in future efforts to holistically uncover perceptual effects. Overall, this study serves as a starting point for testing other political topics with and without national significance. Moreover, the sample of this study is limited to the Austrian political sphere and young adolescents. Although memes play an important role for young people (Cortesi and Gasser, 2015; Lindgren, 2017; Willmore and Hocking, 2017), perceptions of digital immigrants—users who might have not grown up with digital communication practices—might also be worthwhile to study through the lens of meme literacy. Finally, further qualitative studies could foster an understanding of memetic recontextualization practices. Here, qualitative approaches to both memes as recontextualized political messages (e.g., content analyses and discourse analyses) and meme creators as contextualizing political actors (e.g., interviews and focus groups) could help to better grasp recontextualization from a procedural perspective.

6. Conclusion

In this paper, we shed light on the question of how different results of recontextualization practices in political Internet memes influence users' perceptions and behavioral intentions. More specifically, in two online experiments, we tested how the recontextualization of political messages through language variety, presentation mode, and humor affects perceptions of various political image macros in the Austrian context as well as their effectiveness and users' intentions to forward political messages. Taken together, both experiments indicated that recontextualization through standard and non-standard language variety is not a decisive factor for both perceptions and behavioral intentions. This also accounts for recontextualization through humor. However, users' perceptions and behavioral intentions are significantly affected by the presentation mode of the political message. Image macros are more likely to be forwarded and perceived as more effective than written plain text messages. Thus, despite previous findings (Huntington, 2020), our study suggests that multimodal meaning-making in image macros needs a more holistic approach. We argue that multimodal recontextualization has a particular persuasive power that leads to deeper reflections of the presented messages. Consequently, the study contributes to the growing body of knowledge on Internet memes as multimodal and recontextualizable vehicles from the receivers' point of view.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

LB and MJ designed the experimental studies reported in this paper. While LB focused on theoretical and methodological questions of perceptual language effects and was responsible for the data collection. MJ was concerned with theoretical and methodological questions of behavioral effects and was responsible for the data analysis. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^The Central Bavarian dialect area in Austria is characterized by a diaglossic language situation (Auer, 2005; Lenz, 2019; Vergeiner et al., 2020), leading to complex patterns of variation across the dialect-standard-axis. However, the conceptual modeling of this axis is still the subject of many controversial debates (Scheutz, 1999; Lenz, 2019; Vergeiner et al., 2022). Even though the dialect's prototypical domain is the private offline conversation among family members and friends, it is nowadays also extensively used in social media contexts.

2. ^In a nutshell: Austrian Standard German is in a complex state of tension with Federal German Standard German (Lanwermeyer et al., 2019).

3. ^A synoptic overview of the use of written “guises” in language perception and attitude research is provided by Soukup (2021, pp. 244–245).

4. ^In most studies, stimuli are given that differ (only) in terms of the linguistic form, that is, which are as identical as possible in terms of content and which are evaluated by subjects based on rating scales (usually semantic differentials) with regard to various (social) characteristics (Soukup, 2021, p. 242).

5. ^The students received no ECTS or money for completing the survey.

6. ^Literary translation of each stimulus pair from left to right: “Highest unemployment in years; spends 210 million euros on PR,” “Transparency; what is that again?,” “Closes schools and stores; opens ski resorts,” “Pays €700,000 for “Kaufhaus Österreich”; platform does not work,” “If you don't have a thesis; there is no threat of plagiarism,” “If you cannot afford the rent, then buy the apartment.”

7. ^Note, for example, that Soukup (2009, p. 112) found significant differences for all 22 tested items.

8. ^Literary translation of the sarcastic message: “Who else should one vote for if not the ÖVP? With its good work, the few scandals are not even noticed.” Literary translation of the non-sarcastic message: “One should vote for the ÖVP again. They have done their job well”.

References

Abraham, L. (2009). Effectiveness of cartoons as a uniquely visual medium for orienting social issues. J. Commun. Monogr. 11, 117–165. doi: 10.1177/152263790901100202

Akram, U., Drabble, J., Cau, G., Hershaw, F., Rajenthran, A., Lowe, M., et al. (2020). Exploratory study on the role of emotion regulation in perceived valence, humour, and beneficial use of depressive internet memes in depression. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-57953-4

Auer, P. (2005). “Europe's sociolinguistic unity. A typology of European dialect/standard constellations,” in Perspectives on Variation. Sociolinguistic, Historical, Comparative, ed. J. van der Auwera, N. Delbecque and D. Geeraerts (New York: Mouton de Gruyter), 7–42.

Bellamy, J. (2012). “Language attitudes in England and Austria,” in A sociolinguistic investigation into perceptions of high and low-prestige varieties in Manchester and Vienna. Stuttgart: Steiner.

Blahak, B. (2021). “Daham statt Islam”: Zur funktionalen Einbindung von Dialektstrukturen in die Sprache politischer Werbeplakate. Zeitschrift für Dialektologie und Linguistik 88, 21–56. doi: 10.25162/zdl-2021-0002

Bolsen, T., Druckman, J. N., and Cook, F. L. (2014). The influence of partisan motivated reasoning on public opinion. Pol. Behav. 36, 235–262. doi: 10.1007/s11109-013-9238-0

Bulatovic, M. (2019). The imitation game: The memefication of political discourse. Eur. View 18, 250–253. doi: 10.1177/1781685819887691

Bülow, L. (2014). “Werbesprachliche Inszenierung des bairischen Dialekts in der überregionalen und regionalen Bierwerbung,” in Skandal und Tabubruch—Heile Welt und Heimat. Bilder von Bayern in Literatur, Film und anderen Künsten, ed. J. Oliver, and H. Krah (Passau: Stutz), 293–313.

Bülow, L., and Johann, M. (2019). Politische Internet-Memes—Theoretische Herausforderungen und empirische Befunde. Berlin: Frank and Timme.