- Department of English, Faculty of Arts and Humanities, University of Macau, Taipa, China

Previous research on Cantonese-English contact in Hong Kong has focused on lexical phenomena, primarily lexical borrowing and intra-sentential, single-word code-switching (or code-mixing). Although code-switching may also involve longer English phrases, the English elements are mostly inserted into Cantonese-framed sentences in accordance with the Matrix Language Frame/MLF Model. In other words, the syntax of Cantonese appears to be largely intact despite words or phrases drawn from English. This paper underscores that in fact English syntax can be melded more intricately with lexis from both Cantonese and English, thus defying the MLF Model; however, recurrent cases are limited to three constructions so far, namely, the which-relative, the English PP-postmodifier, and an [NP COP P NP] sequence with an English preposition. A re-examination of these three constructions reveals that, rather than linguistic economy, they are semantically and pragmatically motivated to convey some specific meaning. Moreover, all these constructions are lexico-syntactic in the sense that they prototypically contain an English word, namely, the relativizer which, an English noun and an English preposition, respectively. Accordingly, these cases can also be treated as code-switching, though structural borrowing better captures the fact that some English syntactic structure is transferred. In line with Construction Grammar, these constructions are better understood as constructional borrowing in which each construction as a whole—composed of not only words from Cantonese and English but also a syntactic structure—conveys specific meaning. As for why such cases of structural or constructional borrowing are limited or partial, this paper suggests that it is more due to a soft constraint that separates English and Cantonese grammars—Hong Kong speakers still tend to convey a sense that they speak Cantonese among themselves—although they draw on linguistic resources from English. In this light, the Borrowability Hierarchy may be recast as a continuum of language separation and fluidity, which offers a more nuanced view to translanguaging.

Introduction: Language Contact Phenomena Involving English in Hong Kong Cantonese

Language contact between English and Cantonese has a long history. Earliest records of lexical borrowings from English are dated even before the colonization of Hong Kong by Britain in 1842, as British traders had already had businesses with Chinese entrepreneurs in Canton (see Bolton, 2003; Bauer, 2006). In the specific context of Hong Kong, language contact phenomena involving Cantonese and English have received much scholarly attention, and a lot of research has been done that documents and analyzes lexical borrowings from English and, more recently, code-switching (or code-mixing). This literature has primarily focused on how Cantonese adopts and integrates English elements at all levels of grammar, namely, phonology, morphology, and syntax. In other words, it is Cantonese which serves as the host language or the Matrix Language (Myers-Scotton, 1993, 2002) while English plays a limited role in inserting content words into the bilingual sentences or the discourse. Put in socio-cultural terms, Cantonese remains the language spoken by the majority of Hong Kong Chinese speakers, despite the depth and breadth of influence from English. In the case of lexical borrowing, most studies address the ways in which different English words are integrated into Cantonese. An early work on the topic, Chan and Kwok (1982) suggest that the process of borrowing is complete not only with an English word being phonologically adapted to Cantonese, but the English word is also assigned standard Chinese characters in writing; furthermore, it is frequently used by many speakers and eventually it becomes a word in Standard Written Chinese [e.g., 咖啡/gaa3-fe11 (coffee)]. More recent lexical borrowings from English may not have standard Chinese characters yet [e.g., kei1-si2 (case)]; however, whether established or recent, English loanwords are mostly phonologically adapted to Cantonese [e.g., /s/ in bus becomes the onset of another syllable in 巴士/baa1-si2 (bus), as Cantonese does not allow a fricative in coda position—see Bauer and Benedict, 1997 for more details], whereas English words that are not phonologically adapted have been treated as code-mixing/code-switching (Reynolds, 1985; Leung, 1987, 2001; Chan, 1992, 1998, 2021). In addition to phonotactics, multi-syllabic English words are often truncated in accordance with the typical word length of corresponding word classes in Cantonese (Luke and Lau, 2005; Li et al., 2016); that is, nouns are truncated to mono-syllabic or bi-syllabic words (e.g., physics becomes fi1; qualification becomes kwo1-li2) and verbs to mono-syllabic words (e.g., monitor becomes mon1). Apart from phonological adaptation (including truncation), another hallmark for lexical borrowing from English is that an English word forms a compound with another Cantonese morpheme [i.e., the loan-blends such as 檸檬水/ling4-mung1 seoi2 (lemon tea), RAP-歌/rap go1 (rap song)—see Chan and Kwok, 1982; Wong et al., 2009]. Moreover, English loanwords involve distinctly Cantonese morphological processes [e.g., a verb is affixed by a Cantonese aspect marker, such as 肥咗/fei4-zo2 (failed) or check-咗/check-zo2 (checked)—see Wong et al., 2009]. Also implied—if not explicitly stated—is that these English loanwords appear in syntactic positions where their corresponding word classes in Cantonese appear; that is, verbs appear in predicative position, nouns appear as heads of noun phrases which are subjects or objects of a sentence, etc. Talking about morpho-syntax, these loanwords are not much different from single-word code-switching (or code-mixing),2 except that in code-switching the English words are not phonologically adapted (i.e., they are pronounced very much like English); nor are multisyllabic English words truncated to fit into typical word lengths in Cantonese (Chan, 1992, 1998, 2021).3 Of course, code-switching also involves longer elements or phrases from English, though they are also supposed to be inserted into a Cantonese-framed sentence (Chan, 1998; Leung, 2001). In sum, Cantonese-English code-switching largely observes the Matrix Language Frame Model (henceforth the MLF Model—Myers-Scotton, 1993, 2002, etc.) in which the Matrix Language (ML) sets the structure and word order of a code-switched sentence (via the Morpheme Order Principle) and provides the grammatical morphemes to that sentence (via the System Morpheme Principle). In light of the MLF Model, Cantonese is usually the Matrix Language (ML) and English is the Embedded Language (EL) which only inserts free and contentful morphemes—known as content morphemes in the MLF Model—into the code-switched sentences (Chan, 1998; Leung, 2001).

One perennial issue arising, in addition to enlarging the vocabulary and expressive power of Hong Kong Cantonese speakers, is whether English has impacted Cantonese in more extensive and profound ways, specifically in terms of morphology and syntax. To approach this issue, we start with the observation that Hong Kong bilingual speakers can and do use distinctively English morphological and syntactic features in what has been described as code-mixing or intra-sentential code-switching. For instance, in an early work, Leung (1987) noted that the English plural marker quite often appears [e.g., see (1) below], even though Cantonese only has a plural marker used exclusively with pronouns [e.g., ngo5 [first person]-dei6 [plural] (we/us)].

Syntactic features of English may be detected in fragments of English too [e.g., (2)].

In (2) above, the English noun phrase with a PP postmodifier (i.e., for admission) shows distinctive English syntactic structure as modifiers are largely prenominal in Cantonese NPs (Matthews and Yip, 2011, also see more discussion below). Translated into Cantonese, the English noun phrase would become one with a pre-modifier, as illustrated in (2a) below.

Features of English morphology and syntax are also evident when English acts as the Matrix Language framing a code-switched sentence; in such examples, Cantonese acts as the Embedded Language inserting words or phrases into that sentence [e.g., (3)].

In Cantonese, (3) would have to be expressed in a way in which baby puppy and my housemate precede—rather than follow—the verb live. In fact, as illustrated in (3a) below, the whole adverbial complement [i.e., with gau2-zai2 bi4-bi1 (baby puppy) and my tung4-uk1 (housemate)] comes before zyu6 (live).4

Despite features of English morphology and syntax in (1), (2), and (3), they arguably appear only when the speaker is speaking English. For (1) and (2), especially under the conception of code-switching, the speaker invoked these morphosyntactic features only after they had switched to English. In the Matrix Language Frame Model (Myers-Scotton, 1993, 2002, etc.), the plural marker -s is an early system morpheme activated alongside the content morpheme chapter, both of which are from English, the Embedded Language. In (2), the English noun phrase is an Embedded Language Island which is formed according to the syntax of the Embedded Language (i.e., English) rather than the Matrix Language (i.e., Cantonese), with the requirement that all words/morphemes are drawn from the Embedded Language. Notwithstanding these instances, there is little evidence in which Hong Kong speakers constantly transfer these features [i.e., plural-marking of common nouns in (1), postmodification in (2)] to Cantonese and use them with Cantonese lexical items (but see more discussion below).5 English acting as the Matrix Language, as exemplified in (3), is possible but rare (Chan, 1998; Leung, 2001; Chen, 2005) among Hong Kong Cantonese speakers. The pattern seems more frequent and likely to be used when a Cantonese speaker is addressing a non-Cantonese speaker or answering an English question (Setter et al., 2010); or else the speakers are returnees who grew up in English-speaking countries and it is a style of their in-group talk (Chen, 2005, 2008, 2015). Although the returnees are supposed to be more marginal in their language practices and identity compared to “local Hongkongers” (Chen, 2008), their speech offers a glimpse into how Cantonese and English can be blended in more intricate ways that defy the asymmetry between the Matrix Language and the Embedded Language as conceptualized in the Matrix Language Frame Model (Myers-Scotton, 1993, 2002, etc.). This is illustrated in (4) below.

It is implausible to determine which language—namely, Cantonese or English—is the Matrix Language or the Embedded Language for this code-switched sentence. On the one hand, many bound morphemes—or the so-called “system morphemes” in the Matrix Language Frame Model—are drawn from Cantonese, including the aspect marker (zo2), the nominalizer (ge3), the classifier (zung2), the plural marker (dei6), and the sentence-final particle (le3), suggesting that Cantonese is the Matrix Language; however, the subject noun phrase is clearly English in structure whose head noun way is followed by a postmodifying that-clause with a postverbal adverbial [i.e., by lei-go3 (your) language], whereas in Cantonese modifiers are largely prenominal and adverbials are preverbal. What defies the Matrix Language Frame Model (Myers-Scotton, 1993, 2002, etc.) here is that this complex noun phrase cannot be an Embedded Language Island [refer to discussion of (2) above] since there are Cantonese determiners [lei5-go3 (your)] within the PP adverbial. Moreover, it is important to note that the Matrix Language Frame Model is designed in such a way that English and Cantonese cannot be both the Matrix Language in this sentence—according to the Asymmetry Principle (Myers-Scotton, 2002, p. 9), if Cantonese is the Matrix Language, English must be the Embedded Language, and vice versa.6

In sum, Hong Kong bilingual speakers do not usually invoke English morphosyntax with Cantonese lexical items although they may do it occasionally. Exceptions such as (3) and (4) indicate that speakers can and do incorporate Cantonese lexical items into English syntactic structures, but very likely they are used in specific social situations which are considered to be more English-oriented. In other words, the constraint is not only a grammatical one per se (such as the Principles in the Matrix Language Frame Model) but also a sociolinguistic and an ideological one. That is to say, integrating Cantonese lexical items with English morphosyntax is generally deemed not appropriate when local Hong Kong Cantonese speakers converse with each other. In addition to the relative rarity of these instances—in comparison with lexical borrowing and single-word code-switching in the related literature—this is evidenced by the fact that the returnees would spontaneously shift to a more Cantonese-dominant “code-mixing style” and avoid English-dominant patterns such as (3) or (4) when talking to local Hong Kong speakers (Chen, 2008, 2015).7 The indexical association of different “code-mixing styles”—i.e., the more Cantonese-dominant one vs. the more English-dominant one—and different groups of speakers—i.e., the local Hong Kong speakers vs. the returnees—is an ideological construction (Silverstein, 2003; Agha, 2007), and so is the distinction between the “local” and the “returnees” itself.

Putting aside the code-mixing style of returnees, the question arises as to whether the so-called local Hong Kong speakers ever incorporate Cantonese lexical items into English morphosyntactic structures. If there is a general ban on melding Cantonese lexical items into English morphosyntactic structures, why would the speakers invoke these patterns? Gibbons (1987) observed a few individual English words that automatically bring along an English structure, which Gibbons (1987) describes as distinctive features of “the mixed code” [e.g., (5)]. An equivalent of (5) exhibits a different word order in pure Cantonese [e.g., (5a)].

In a similar vein, Li (1999) argues that some English verbs introduce an English VO order [e.g., (6)], since the equivalent expression in Cantonese would be an OV structure [e.g., (6a)].

What is more, the VO structure is preferred over the OV structure since the former is more economical in invoking fewer syllables/morphemes and structure; for example, (6) requires less effort than (6a) in that the former invokes 2 words or 3 syllables whereas (6a) invokes 3 words or 4 syllables. However, as Li (1999) notes himself, the alternative VO order is available in Cantonese too, especially in spoken Cantonese [e.g., in relation to (6) and (6a), we can also say lyun4-lok3 nei5 (contact you) in Cantonese].8 More research and quantitative evidence is called for to confirm the claim that the English verbs have indeed introduced an English syntactic structure, or else these English verbs are inserted into a VO order framed by Cantonese along the lines of the Matrix Language Frame Model (i.e., Cantonese is the ML). At any rate, Li (1999) highlights the possibility of an English word bringing along some English syntactic structure, which he calls “lexicosyntactic transference” (p. 31).

The remainder of this paper reviews three patterns of code-switching which violate the general constraint on incorporating Cantonese lexical items into English syntactic structures. Instead of linguistic economy (Li, 1999), it is argued that all three constructions are motivated by some semantic/pragmatic function which is hard to fulfill in pure Cantonese in the light of Cognitive Grammar (Langacker, 2008). The communicative benefit thus outweighs the ban on invoking English syntactic structures with Cantonese lexis. While all three constructions—composed of words from Cantonese and English—can be seen as instantiations of code-switching, they are better treated as a separate phenomenon since some English syntactic structure is triggered by an English word. Whereas this aspect is well-captured by the concept of lexicosyntactic transference (Li, 1999; Leung, 2010), structural borrowing seems more appropriate in highlighting the fact that a particular syntactic structure is borrowed. In the Conclusion section, I shall suggest that structural borrowing is recast as constructional borrowing according to which the structure of the code-switched or bilingual sentence itself contributes to the meaning of the code-switched or bilingual sentence, along the lines of Construction Grammar (Croft, 2001). Despite huge difference in their forms and way or degree of integration (to Cantonese), constructional borrowing and lexical borrowing or single-word code-switching are in fact the same in being the mot juste (i.e., the best expression—Poplack, 1988) in specific communicative contexts.

The Postmodifying Which-Clause

Adopting Li's (1999) ideas, Leung (2010) discusses the postmodifying which-clause in Hong Kong Cantonese, suggesting that it is yet another instance of lexicosyntactic transference induced by the Principle of Economy. The construction is most likely drawn from English grammar since Cantonese relative clauses are premodifers in an NP (Yip and Matthews, 2000; Matthews and Yip, 2011). Limited as they are, the available naturalistic data (Leung, 2010, p. 71–74)—collected by the author and his friends in casual conversations and group meetings (Leung, 2010, p. 28)—show deviations from the conventional behaviors of relative clauses in English.9 To begin with, it is actually a specific type of English relative clauses that is being borrowed. First and foremost, the relative clause mostly modifies the previous clause rather than an NP in it. In other words, which largely refers backwards to a clausal antecedent [14 out of 20 tokens in Leung's (2010) diary data], as illustrated in (7) below.

In (7) above, which introduces the speaker's comment (i.e., which I do not know is like that or not) on a situation rather than an entity expressed in the previous clause (i.e., they are an organization who will make replies). Even when the relative pronoun which refers to an NP in the beginning of the sentence, as in (8) below, the relative clause also always follows the matrix clause which contains the NP antecedent.10

There are no data in which the relative clause is embedded into the matrix clause [e.g., The man [whom you talked to]RELATIVE CLAUSE is her husband]. The separation between a relativized NP and the relative clause is also possible in English, if it is supposedly a case of extraposition that happens when the relative clause is much longer or heavier than “the material that would follow it in the matrix clause if it occupied its default position following its antecedent” (Huddleston et al., 2002, p. 1066).

Leung (2010, p. 11) argues that the postmodifying which-clause is prompted by the Principle of Economy (Li, 1999). Assuming the which-relative clause becomes more integrated with the previous clause, the information content is expressed in one sentence; without the which-relative, the same content would have to be expressed in two completely separate sentences. Intuitively, it is true that which is optional in (7); that is, without which, the two clauses in Cantonese would sound perfectly grammatical. Moreover, Cantonese lacks a similar connective which is anaphoric to an antecedent in the matrix clause. Nonetheless, it is at best doubtful whether the which-relative in (7) is indeed integrated with the matrix clause and at worst misguided to treat the which-relative as more economical than the pure Cantonese counterpart without which—after all, in Li's (1999) formulation, the Principle of Economy refers rather straightforwardly to the use of fewer words/syllables. The separation of the NP antecedent and the which-relative in (8) further points to the rather loose connection between the which-relative and the matrix clause. At any rate, the Principle of Economy cannot explain why in Hong Kong Cantonese the relative clause always follows the matrix clause—that is, it never appears in the middle of it—and it modifies a clause [e.g., (7)—i.e., 14 out of 20 tokens in Leung's (2010) data] much more frequently than an NP [e.g., (8)—i.e., 6 out of 20 tokens]. What is more, only which has been attested in the relative clauses in Hong Kong Cantonese; in other words, relative pronouns such as where, who/whom, and the complementizer that are not found. The absence of these forms, however, follows naturally if the which-relatives in Hong Kong Cantonese are quintessentially non-restrictive, supplementary relative clauses which canonically refer to a preceding clausal antecedent and in which the only appropriate relative pronoun is which (Huddleston et al., 2002).

Another difference between the which-relative in Hong Kong Cantonese and that in Standard English lies in the optionality of which in the former. That is, the which-relative still sounds grammatical if which is deleted. Obviously, this would not apply for subject relative clauses—of which the which-relative clause in (7) is apparently an example11—in Standard English. For instance, which cannot be deleted in an English sequence such as Derek wants to quit his job and become a Youtuber, which is shocking, as it would render the second clause without a subject (i.e., *Is shocking). The possibility of which-deletion in (7), however, becomes sensible, if which is not really moved from inside the relative clause as in generative analysis of English relatives. That is, the subject of the predicate—i.e., hai6-m4-hai6 gam2 [roughly “(it) is like that or not)”]—can be analyzed as phonologically null as it is in Cantonese or other Sinitic languages (i.e., Chinese has been considered a pro-drop language in generative syntax, with pro being the covert pronoun—Yip and Matthews, 2000). In this light, it is likely that which in Hong Kong Cantonese is not an argument in the relative clause; more specifically, which in (7) may well be more like a connective (i.e., [whichi ngo5 m4 zi1 (proi) hai6-m4-hai6 gam2] (which I do not know is like that or not)) than a relativizer binding a gap in the relative clause (i.e., [whichi ngo5 m4 zi1 ___i hai6-m4-hai6 gam2]). Similarly, in Hong Kong Cantonese, which sounds omissible too in an object relative clause such as (8). Parallel to (7), in (8), which is also tagged to the relative clause and coreferential with an empty pronoun—i.e., [whichi ngo5 gok3 dak1 m4 sai2 zoi3 jiu3 recap (proi)] [which I think (we) do not need to recapitulate]—rather than moved from within the relative clause—i.e., [whichi ngo5 gok3 dak1 m4 sai2 zoi3 jiu3 recap ___i].

A third deviation from Standard English concerns the emergence of another variant of the construction in which the relativizer takes the form of which-is instead of which (7 out of 20 tokens in Leung, 2010). Precisely how which-is may have arisen from which remains cryptic. At any rate, in the same way as the which-relatives in Hong Kong Cantonese, the which-is variant always follows the matrix clause and is mostly anaphoric to a clausal antecedent in Leung's (2010) naturalistic data [see (9) below].

Similar to which, which-is rarely refers to an NP antecedent, and there is only one such example in Leung's (2010) data.

Leung (2010) suggests that which-is is a variant of which and a word in its own right. In other words, neither which nor is is an integral element in the relative (second) clause, but rather it is tagged to the relative (second) clause like a connective or conjunct (e.g., nonetheless or moreover in English—this would explain why which-is can be preceded by a conjunction [tung4-maai4 (and) in (10)]. The intuition that which-is can be omitted in (9) and (10) lends further support to such an analysis, even though the version without which-is would sound less coherent (but nonetheless grammatical) in either case.

The above facts or properties of which-relatives point to a picture in which, precisely speaking, Hong Kong Cantonese borrows the non-restrictive, supplementary relative clause construction which modifies a clausal antecedent expressed in the matrix clause. Those which-relative clauses referring to an NP antecedent and the which-is variant are likely to be extensions from the canonical form (i.e., the sentential/clausal relative clause). Looking back at earlier literature, a similar example of sentential relative clause can be attested in Chan (1992), a possible precursor from which the which-relatives and their variants discussed in Leung (2010) could have evolved—notably, in this example, which refers backwards to a clause, and it is clearly not an argument in the relative (second) clause.

Following this line of analysis, the current construction [CLAUSE [which/which is CLAUSE]CLAUSE] involves two separate clauses. Consequently, it defies an account by the Matrix Language Frame Model (Myers-Scotton, 1993, 2002) since the latter—together with its Principles—applies to a mono-clause, which is couched as a CP (Complementizer Clause) in terms of generative grammar.

If we conceptualize the which-relatives in Hong Kong Cantonese as essentially non-restrictive, supplementary relative clauses referring to a clausal antecedent, we reach a better understanding of the meaning or motivation of the construction beyond the Principle of Economy (Li, 1999). Crucially, the construction enables a speaker to elaborate on a situation presented as an objective fact (i.e., as encoded in the first/matrix clause), and very often this elaboration represents the speaker's personal assessment of the situation (i.e., as encoded in the second/relative clause—see (7)–(10)). Accordingly, the English relativizer which/which-is is used to introduce the speaker's personal assessment. In this light, which/which-is in Hong Kong Cantonese functions as a discourse or pragmatic marker (Schiffrin, 1987) which gives the listener a hint of the speaker's upcoming verbal action (i.e., giving an assessment of the first clause). Without the discourse marker, the listener would still be able to infer that the second clause represents the speaker's personal assessment of the situation expressed in the matrix/first clause, but more processing cost would be required for the inference (Sperber and Wilson, 1995). In other words, the which/which-is relative is not more economical in terms of the number of words/morphemes invoked (Li, 1999). Rather, the construction is more explicit and thus more economical in terms of “processing cost” (Sperber and Wilson, 1995); that is, it spares the listener's cognitive effort in inferring the speaker's intentions and his/her ongoing message, hence functioning as a contextualization cue (Gumperz, 1982).

An English Noun and a Postmodifying PP

Based on a small corpus of naturalistic data, Chan (2015) discusses another construction which also involves a postmodifier, but here the postmodifier is well-integrated with the clause, namely, a PP post-modifier in a complex NP, as illustrated in (12) below.

As mentioned above, Cantonese is head-final in NPs with different types of premodifiers (Yip and Matthews, 2000; Matthews and Yip, 2011).12 In Cantonese syntax, the information content in the postmodifying PP in (12) would be mapped into a premodifier, as shown in (12a) below.

Examples (12) and (12a) appear to be semantically equivalent. In terms of the number of words or syllables the English NP structure in (12) is not more economical than (12a), and hence it is not likely to be prompted by the Principle of Economy (Li, 1999). Furthermore, in a way very similar to (4) discussed above, (12) violates the Matrix Language Frame Model (Myers-Scotton, 1993, 2002)—whereas the system morphemes are drawn from Cantonese, the putative Matrix Language, such as the plural marker (dei6), the demonstrative (go2) and the classifier (go3), the complex NP follows English grammar with a PP modifier, flouting the Morpheme Order Principle. Crucially, the NP which contains Cantonese elements (i.e., go2 go3) is not an Embedded Language (EL) Island which may elude the grammar of the Matrix Language (i.e., Cantonese) under the Matrix Language Frame Model. In addition to word order in the complex NP, another feature of the data clearly suggests that the NP is formed according to English grammar; that is, an English noun may idiomatically select a particular English preposition apart from of which introduces the PP postmodifier [e.g., contribution to in (13) below].

Given that in most cases Cantonese-English code-switching abides by the Matrix Language Frame model (Chan, 1998; Leung, 2001), we may wonder why a structure like (12) or (13) is invoked in the first place.

Drawing on Cognitive Grammar (Langacker, 2008), Chan (2015) proposes that the postmodifier structure [e.g., (12)] and the premodifier structure [e.g., (12a)], while looking the same in meaning, in fact convey different construals. That is, both instances represent the same event, and yet the entities in the event receive different levels of attention. In particular, in (12), the head noun (plenary speakers) is preposed and foregrounded, whereas in (12a), it is the NP modifier [go2 go3 conference (that conference)] that is foregrounded. In other words, (12) focuses on what they did in the conference (i.e., in answer to the question—What did they do in that conference?), while (12a) highlights that conference in which they were plenary speakers (i.e., in answer to the question—Which conference were they plenary speakers of ?). In terms of Cognitive Grammar (Langacker, 2008), in (12), plenary speakers is the profile/figure which marks new or focused information whereas go2 go3 conference (that conference) is the base/ground which marks given or background information. On the other hand, in (12a), go2 go3 conference (that conference) is the profile/figure while plenary speakers is the base/ground. This analysis explains the fact that, in the majority of the examples in the dataset, the backgrounded NP embedded in the PP postmodifier is frequently marked by various forms of definite reference [i.e., 25 out of 33 tokens, e.g., go2-go3 (that) in (12) and (13)]. However, the determiner of the complex NP is more variable [i.e., zero determiner in plenary speakers in (12) and indefinite determiner in jat1-di1 contribution (some contribution) in (13)].

As for the foregrounded head noun which appears before the PP postmodifier, it often cancels a possible inference of a speaker's previous utterance, as in (14) below.

The context of example (14) was a wedding banquet in which the speaker told a friend in Cantonese that the “waist” (code-switched in English too) could be even “better,” suggesting that his friend looked plump despite much work-out. But actually the speaker was referring to the cutting of his friend's jacket rather than his physique, hence example (14). The word cutting—in contrast with the listener's body as possibly inferred—is thus highlighted to clarify the speaker's previous comment.

Under this analysis, it makes sense to say, on a par with the which/which-is relatives discussed in section The Postmodifying Which-Clause (Leung, 2010), the postmodifying PP construction in Hong Kong Cantonese also borrows a specific type of structure or construction from English; only a certain type of postmodifier (i.e., PP) is borrowed among the full range of English postmodifiers in complex NPs (e.g., relative clauses,13 non-finite clauses, that-clauses). Moreover, this PP contains an NP which marks given or background information, although, in English, the information status of this NP is more flexible and it can encode new or focused information too (e.g., Churchill was a man of great courage; This is a book about conspiracy theory.). Notwithstanding, variants of this pattern can be expected as language always keeps evolving. In the following example, the NP in the PP is horrendously complex, and in context it appears to encode new information. Plausibly prompted by end-weight or end focus (within the NP), crucially, this NP is marked by the indefinite determiner [i.e., jat1-di1 (some)] rather than the more common definite determiners.

An issue that remains unresolved is whether this construction of complex NP with a postmodifying PP is triggered by lexicosyntactic transference (Li, 1999). It is highly plausible that an English noun triggers the construction, as it appears in most of the examples [i.e., 27 out of 33 tokens, e.g., (12)–(15)]. This analysis could have interesting and significant implications in the language contact literature since nouns are often thought to be detached from specific syntactic patterns which involve them [for instance, English nouns are detached from a complex NP [DET N PP]], and so they are easily borrowed or transferred into different syntactic patterns of NP in another language). In this set of data, however, we see that an English noun can bring along a postmodifying PP, which is a distinctively English construction, although there are also plenty of examples in which an English noun is embedded into a typical Cantonese NP structure with premodifiers, as illustrated in (16) below.

Another complication is that there are a few examples in which the head noun is drawn from Cantonese, as illustrated in (17) below from Chan's (2015) dataset.

Chan (2015) explains this pattern by resorting to schematization, drawing on the idea that a construction can be completely specific (e.g., an idiom in which all the words are fixed), completely schematic (e.g., a pattern of DET N in which different words may be inserted into the two syntactic slots—i.e., DET and N), or partially schematic or specific (e.g., NP gives NP to NP)—in line with Construction Grammar (Croft, 2001). A complex NP involving an English head noun and a postmodifying PP [e.g., (12)–(15)] is seen as a partially schematic and specific construction which requires the head noun and the preposition to be drawn from English, but it has become more schematic more lately and so the head noun may be drawn from Cantonese too.

Judging from the idiomatic selection between the English counterpart of the Cantonese head noun in (17) (i.e., data collection) and the English preposition (i.e., on), there may well be another alternative account which is no less plausible. That is, even though the speaker is uttering the words in Cantonese [i.e., zi1-liu2 sau2-zaap6 (data collection)], the English synonym (data collection) is also co-activated,14 and the postmodifier PP and the particular preposition it selects (i.e., data collection on X but not *data collection in X) are also triggered. Also, recall that Cantonese NPs are head-final, and a Cantonese noun presumably does not select a following PP complement; hence the PP [i.e., on go2 di1 tickets (on those tickets)] is most likely to be selected by an English noun though it is not chosen and outputted here. This account would allow us to maintain that the postmodifying PP—as a case of structural borrowing—is triggered lexically, even though in the minority of examples like (17) the triggering process is more indirect via a co-activated English noun.15

An English Preposition in a Predicative PP

The last construction discussed here which involves structural borrowing from English is a sequence of [NP COP PEnglish NP] in which the preposition has to be drawn from English (Chan, 2018). In fact, the English preposition is also involved in a number of other constructions, no less the NP postmodifier discussed in the above section. However, the [NP COP PEnglish NP] sequence appears most frequent in naturalistic data (e.g., the datasets in Chan, 2018); what is more, the construction is the earliest one to emerge with an English preposition in the literature. The following example is drawn from Gibbons (1987) whose data of the speech of Hong Kong University students were collected in the late 1970s.

In Cantonese syntax, (18) would have to be expressed with a localizer (i.e., a postposition—Matthews and Yip, 2011; Chan, 2018), as illustrated in (18a) below.

In addition to the localizer/postposition leoi5-min6 (within/inside), a locative verb hai2 has to be used, whereas the segmentally homophonous (but in a different tone) copular verb hai6 is optional. Actually, hai6 has become more of an optional focus marker (i.e., a sentence remains grammatical without it) except in contexts where the predicate is an NP [e.g., Keoi5 hai6 ji1-saang1 (He/she is a doctor)—Matthews and Yip, 2011; Chan, 2018]. Looking at (18) again, it is not difficult to see that its structure is drawn from English grammar—it is much more similar to the structure of an English sentence [see the translation of (18)] rather than that of a Cantonese-framed sentence [i.e., (18a)]. Moreover, once again, it is difficult to assign Cantonese the status of Matrix Language here. Although the system morphemes—function words or bound morphemes such as the numeral and classifier (i.e., jat1-go3)—are drawn from Cantonese, the word order (i.e., NP COP P NP) of the sentence is drawn from English, thus flouting the Morpheme Order Principle (Myers-Scotton, 1993); nor is it plausible to treat English as the Matrix Language, as the function words and bound morphemes would then be supplied by English but not Cantonese.

In case the English preposition does not denote a temporal/spatial position (e.g., for), the sentence would be expressed by a serial verb construction in Cantonese syntax, as illustrated in (19) and (19a) below.

In (19a), the semantic equivalent of for is wai5, both being a marker introducing a BENEFICIARY. In Sinitic languages, however, it is often analyzed as a coverb rather than a preposition (Matthews and Yip, 2011), since it is obligatorily followed by another verb (i.e., ji4-cit3 [to install/set up)], and, in general, they are more like verbs morphologically (e.g., most of them may take an aspect marker or a verbal particle).

Alternatively, the English preposition may be replaced by a full verb in Cantonese, as illustrated in (20) and (20a) below.

It is not immediately obvious whether examples (19) and (20) abide by the Matrix Language Frame Model (Myers-Scotton, 1993, 2002), since the English prepositions for and from are treated as content words (or content morphemes) on par with nouns and verbs, and they can be drawn from English, the putative Embedded Language (EL), according to the model. In a similar fashion, neither (19) nor (20) violates the word order of Cantonese, the putative Matrix Language, and accordingly the Morpheme Order Principle, if we treat the English preposition for or from as equivalent to Cantonese coverbs [e.g., wai6 (for) in (19b)] or even verbs [e.g., lei4-zi6 (come from) in (20b)], both of which are followed by an obligatory NP complement. Nonetheless, in view of (19b) and (20b), the English preposition could not be inserted into a Cantonese-framed sentence in (19) and (20). If the English preposition for were inserted along the lines of the Matrix Language Frame Model (Myers-Scotton, 1993, 2002), there should be a second predicate following the PP as in (19a). As for (20), it is doubtful as to why a preposition from can be inserted into a verb position [e.g., lei4-zi6 (come from) in (20a)], with categorial equivalence being assumed to be a precondition for such insertion (Muysken, 2000; Chan, 2018).

There are a number of other more intricate arguments for the [NP COP PEnglish NP] construction [e.g., (18), (19), and (20)] to be considered a case of structural borrowing from English, which are not detailed here (but see Chan, 2018). For the purpose of this paper, it is sufficient to note that examples such as (18), (19), and (20) would be translated into different constructions with different syntax in Cantonese grammar [i.e., a postposition in (18a); a serial verb construction in (19a), and a verb in (20a)]. What is more, when an English preposition appears in predicative position in a Cantonese sentence, the Cantonese hai6 appears more obligatory as a predicator, in other words, a bona fide copular verb rather than a focus/emphatic marker which is optional in Cantonese in most contexts. If hai6 is absent, there must be another element which serves as the predicator; for instance, the English preposition itself is reanalyzed as a verb which may take a Cantonese aspect marker, or else the English preposition behaves as a coverb with another verb or predicate following. However, in comparison with the [NP COP PEnglish NP] sequence, these are really different constructions which are fewer in naturalistic data (e.g., the datasets in Chan, 2018) and which most likely emerged later (see detailed discussion in Chan, 2018). In a nutshell, although the copular verb is always drawn from Cantonese (i.e., hai6) for some unclear reason, [NP hai6 PEnglish NP] originates from English grammar and is hence a case of structural borrowing.

As for the motivation for this construction, the Principle of Economy (Li, 1999) seems to apply—as the [NP hai6 PEnglish NP] construction contain fewer words or morphemes than its corresponding expressions which are more in line with Cantonese grammar [e.g., (18a), (19a) and (20a)]. Putting aside other issues concerning the Principle of Economy,16 it somehow assumes that a bilingual or code-switched construction is semantically identical to a counterpart in pure Cantonese; that is, it is only through its comparison with the Cantonese counterpart that the code-switched construction is considered more economical. However, through the lens of Cognitive Grammar (Langacker, 2008), the [NP hai6 PEnglish NP] construction actually conveys nuanced meaning which eludes their apparent counterparts and which motivates its usage in specific communicative contexts. In other words, the pairs of sentences illustrated in (18)/(18a), (19)/(19a), and (20)/(20a) are not exact paraphrases and they in fact convey different construals (Langacker, 2008) of the same event (Chan, 2018). More specifically, in (18a), the English preposition within represents a RELATIONSHIP which links the trajectory [the figure or profiled/highlighted entity—i.e., jat1-go3 society (a society)] and the landmark [the ground or backgrounded entity—i.e., jat1-go3 country (a country)]. On the other hand, in (18a), the postposition/localizer leoi5-min6 (within/inside) is conceptualized as a THING which is part of the landmark and which apparently conceptualizes a well-defined or bounded space (Chan, 2018). In (19), the PP [i.e., for di1 lecturers (for the lecturers)] is conceptualized as a property of the subject NP [i.e., ni1 go3 course (this course)], whereas the corresponding coverb phrase [i.e., wai5 di lecturers (for the lecturers)] is presented as an adjunct of another verb [i.e., ji4-cit3 (to install/set up)]. Overall, (19a) encodes a more dynamic process than (19) with an additional verb or predicate (Chan, 2018). Concerning the last pair, (20a) encodes a more specific process as the verb is spelt out [i.e., lei4-zi6 (come from)], whereas (20) sounds more schematic with the copular verb hai6 which is vaguer in meaning. All in all, the [NP hai6 PEnglish NP] construction is semantically or pragmatically motivated to convey a certain construal which differs from those conveyed by similar constructions in Cantonese [i.e., (18a), (19a) and (20a)].

Discussion and Conclusions

More than a century of Cantonese-English contact, concomitant with more widespread use of English and a higher English competence among Cantonese speakers (see Bolton et al., 2020 for a recent survey), has facilitated outcomes beyond the familiar cases of lexical borrowing and code-switching in Hong Kong Cantonese, in which single words or phrases may be borrowed or transferred from English and inserted into a Cantonese-framed sentence. That is, a grammatical structure or construction can also be borrowed from English with words or morphemes drawn from both English and Cantonese. This paper surveys three examples of such structural borrowing that have been documented in the existing literature, including the which/which-is relative, an NP with a postmodifying PP headed by an English preposition, and a sequence of [NP COP P NP] with an English preposition. All three constructions are deployed to convey some subtle semantic or pragmatic effect instead of encoding some new concept or information content without a proper word in Cantonese, as has often been observed to be the case for lexical borrowing or intra-sentential code-switching (Poplack, 1988; Myers-Scotton, 1993—also see Li, 2000 for Cantonese-English code-switching in Hong Kong).

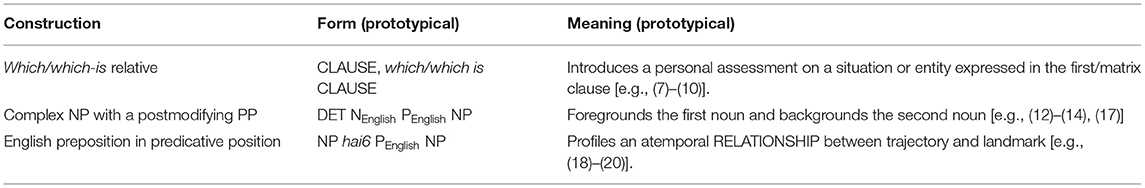

Syntactically speaking, while single words or phrases from English are inserted into a Cantonese-framed sentence in lexical borrowing or intra-sentential code-switching, structural borrowing defies this generalization, as some kind of English structure is transferred. This difference is well-illustrated by the fact that the former abides by the Matrix Language Frame Model (Myers-Scotton, 1993) with Cantonese being the Matrix Language and English being the Embedded Language, but the latter constructions defy it in one way or the other. One mechanism underlying these three constructions of structural borrowing from English in Hong Kong Cantonese is lexicosyntactic transference (Li, 1999), in which an English word (i.e., which/which-is, an English noun, and an English preposition, respectively) is interwoven with an English grammatical structure. Construction Grammar (e.g., Croft, 2001) offers a more holistic framework which unifies lexicosyntactic transference (Li, 1999) and the respective semantic/pragmatic motivation of the constructions discussed above, seeing a construction as a sign which is a mapping of form and meaning. More concretely, these constructions are partially schematic and partially specific, and each of them conveys a prototypical semantic/pragmatic meaning. In light of this, the three cases of structural borrowing discussed here may be recast as constructional borrowing (Table 1).

What may be the implications of these cases of constructional borrowing on the broader picture of language contact in Hong Kong? In one perspective, as proposed in Chan (2015, 2018, 2021), Cantonese and English are in fact more deeply intertwined than the more familiar and documented cases of lexical borrowing or code-switching. This perspective tallies with previous suggestions that Cantonese-English code-switching is in fact a mixed-code (Gibbons, 1987; Li, 2000) which draws resources from the two languages at all levels (i.e., phonological, lexical and syntactic). Though not identical, such a view also comes close to the hugely popular concept of translanguaging, according to which bi/multilingual speakers draw on language resources to make meaning and to communicate efficiently irrespective of the boundaries of “named languages” (Otheguy et al., 2015, 2019; Li, 2018). Whereas Cantonese-English bilinguals can certainly manipulate and mix features from both languages in their speech, taking into consideration the whole literature of Cantonese-English contact in Hong Kong, we do find that the three constructions reviewed in this paper are apparently rarer in comparison with lexical borrowing and code-switching in Cantonese-framed sentences.17 What is more, these constructions most probably emerged later than lexical borrowing and code-switching, even though among them the [NP hai6 PEnglish NP] sequence was documented earlier in Gibbons (1987), and it presumably arose earlier than the which/which-is relative (Leung, 2010) and the NP with a postmodifying PP (Chan, 2015). Another point to note is that there are in fact plenty more syntactic differences between Cantonese and English and we may wonder why constructional (or structural) borrowing has been confined to only the three constructions so far.18 In particular, in the case of which/which-is relative and the NP postmodifier, the structural borrowing is in a sense not complete. As discussed above, in the former case, only the non-restrictive and supplementary relative with which/which-is as relativizer is borrowed; in the latter, only PP postmodifiers but not other types of NP postmodifiers (e.g., relative clauses, that-clauses) are borrowed. While a much wider range of constructions have appeared with an English preposition (see Chan, 2018 for details), the [NP hai6 PEnglish NP] sequence remains dominant and there is little data in which a preposition, for instance, introduces a postverbal adjunct (e.g., Daniel is doing his work-out in the gym.).

All the above facts considered, these cases of constructional (or structural) borrowing are exceptions to the general tendency for English to be transferred to Cantonese on a lexical level (recall discussion in section Introduction: Language Contact Phenomena Involving English in Hong Kong Cantonese). Taking a bird's-eye view on Cantonese-English contact, we may see that bi/multilingual speakers are always disposed to draw resources from their holistic linguistic repertoire regardless of the boundaries of “named languages” for efficient communication—as what Li (2018) has called the Translanguaging Instinct. Nonetheless, in early phases of language contact, when bi/multilingual speakers transfer materials from a foreign language, these materials are adapted in various ways to be nativized into the host or borrowing language. Such adaptations may be seen as these speakers demarcating the two languages despite the borrowing—in the specific context of Cantonese-English contact, phonological adaptation and truncation of an English word, as well as assigning Chinese characters to it on a graphical level—may be seen as ways in which Cantonese speakers turn it into “Cantonese” and accordingly draw a boundary between Cantonese and English. In code-switching, English words and phrases are not adapted phonologically and pronounced as they would be in “English” irrespective of the phonotactic constraints of Cantonese (Chan, 2021); in a way, the boundary between Cantonese and English has faded. In structural or constructional borrowing, as illustrated in the three constructions reviewed in this paper, the distinctiveness between the two languages blurs even further as a syntactic pattern may be drawn from English amidst others in Cantonese. If this is on the right track, the often-quoted Borrowability Hierarchy (Thomason and Kaufman, 1988) would receive an explanation along the continuum of language separation and fluidity—that is, different types of language contact phenomena, including lexical borrowing, code-switching (i.e., lexical insertions without phonological adaptation) and structural (or constructional) borrowing, often appear in fixed sequence one after another because the sequence reflects how bi/multilingual speakers draw boundaries between “named languages” in language contact at first but gradually relax them in a speech community. As for now, the prevalence of lexical borrowing and code-switching over structural (or constructional) borrowing in Hong Kong Cantonese reflects the vitality and dominance of Cantonese in the language ecology of Hong Kong despite a prolonged period of contact with English.19 However, as suggested by the three constructions discussed here, the separation of syntax between Cantonese and English is determined more plausibly by a soft constraint that is sociolinguistically or ideologically driven (i.e., Hong Kong speakers generally still tend to keep the syntax of Cantonese intact despite materials transferred from English) than by an absolute one imposed by the language faculty along the lines of the Matrix Language Frame Model (Myers-Scotton, 1993, 2002).

Author's Note

In this paper, “Hong Kong Cantonese” is intended to be a general descriptive label for the kind of Cantonese spoken in Hong Kong; differences between Hong Kong Cantonese and other varieties of Cantonese (e.g., as spoken in Macau or Canton/Guangzhou) are not dealt with here.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

1, first person pronoun; 2, second person pronoun; 3, third person pronoun; ASP, aspect marker; CL, classifier; COP, copular verb; COV, coverb; DEM, demonstrative; EMP, emphatic marker; EXIST, existential marker; FOC, focus marker; LOC, locative marker; LNK, linking particle; MOD, modal verb; NEG, negation marker; NOM, nominalizer; NUM, numeral; P, preposition/postposition; PL, plural marker; PRT, verbal particle; QUAN, quantifier; SFP, sentence-final particle.

Footnotes

1. ^Transcriptions of Cantonese in this paper are based on Jyut6-Ping3—the Cantonese Romanization Scheme designed by the Linguistic Society of Hong Kong. See https://www.lshk.org/jyutping.

2. ^The term “code-mixing” tends to be used in earlier works in the literature in referring to intra-sentential alternation of languages (Gibbons, 1987; Chan, 1992, etc.), but “code-switching” has emerged to become a more popular umbrella term which refers to both inter-sentential and intra-sentential alternation of languages (Chan, 1998; Leung, 2001) in alignment with influential works in the related literature (e.g., Gumperz, 1982; Myers-Scotton, 1993).

3. ^There remain different views as to whether single-word items transferred from another language are code-switching or borrowing—Poplack (2018) argues that they are mostly borrowing or loanwords as long as there is morpho-syntactic integration with the host language, whereas Myers-Scotton (1993) holds that single-word code-switches are more widespread though less frequent than established loanwords. As for Cantonese-English contact in Hong Kong, the distinction between lexical borrowing and (single-word) code-switching is far from clear-cut. Since this study focuses on structural or constructional borrowing from English, I cannot delve into the issue here, but see Chan (2021) for some discussion.

4. ^Notice, however, that (3a) is not exactly an SOV structure. The object noun phrase—gau2-zai2 bi4-bi1 tung4-maai4 ngo5 tung4-uk1 (baby puppy and my housemate)—follows tung4 (with), which is more of a verbal element than a preposition, technically known as a coverb in Sinitic languages (Matthews and Yip, 2011—see below for more details). In other words, (3a) is a serial verb construction [i.e., S V(COV) O V].

5. ^Very occasionally internet users may use-s after a Chinese/Cantonese noun but instances like that are extremely rare and they seem to be funny and attention-seeking. For instance, a recent post on Instagram includes the word “鏡粉s” [literally Mirror (the name of a very popular boys' band in Hong Kong) + fan + s, that is, the fans of Mirror].

6. ^Myers-Scotton (2002) did mention the possibility of a Composite Matrix Language which draws from grammatical resources of the two languages participating in code-switching. Nevertheless, a Composite Matrix Language is supposed to be an outcome of Matrix Language Turnover in a contact situation of abrupt language shift in society or language attrition of individual bilingual speakers. These scenarios do not seem to apply to the majority of data discussed in this paper, as Cantonese has always remained the most widely spoken (home) language and most speakers are local Hong Kong bilinguals—maybe except the returnees Chen (2005, 2008, 2015) discussed.

7. ^We can actually see (4) as an example of such “style-shifting” (Chen, 2008) as the speaker is trying to become more Cantonese-dominant in the middle of the sentence—the more English-dominant subject is followed by the more Cantonese-dominant predicate.

8. ^It is noteworthy that Li (1999) based his discussion on data of written Cantonese in popular press, which may be more heavily influenced by Standard Written Chinese and somewhat different from spoken Cantonese.

9. ^Though not detailed further, in my reading of the data, the participants or speakers were most likely young university students (including the author and his friends) who organized activities for a Christian fellowship at school. In addition to the naturalistic data, Leung (2010) also conducted a grammaticality test with a list of invented samples of Cantonese-English code-switched sentences, including some items involving the which/which-is relative. This paper is primarily concerned with real usage of the construction and hence the findings of the grammaticality test are not considered here.

10. ^Notice that in this particular example the NP is not exactly in Subject but in Topic position. An English translation of the sentence paying close attention to the word order of the example would read: [The questions on this sheet]NP, (we) have already discussed (them) a bit in the camp, which I think (we) do not have to recap. There is another piece of data in Leung (2010) where which apparently refers to an NP at the beginning of a sentence, but that NP appears to be a Topic as well. In Standard English, a relative clause is not used to refer to a Topic NP, whether it is immediately following it (e.g., *Those books, which are interesting, I have read) or separated from it (*Those books I have read, which are interesting). This shows another deviation of which-relatives in Hong Kong Cantonese from the norms of Standard English.

11. ^The relative clause in (7) is a subject relative clause if we take which to originate from the subject position of the embedded clause [i.e., which hai6-m4-hai6 gam2 (roughly “which is like that”)] and it moves up to a higher clause [i.e., whichi ngo5m4zi1___i hai6-m4-hai6 gam2 (whichi I do not know ___i is like that or not)] as in generative grammar. See below.

12. ^Luke (1998) suggests that there are in fact postnominal relative clauses in Cantonese, which are intuitively more frequent in spoken communication.Chan (2015, p. 20) points out that these putative relative clauses always modify an object NP in the matrix clause, and they may well be secondary predicates rather than relative clauses per se.

13. ^Recall that the which/which-is relatives discussed in section The Postmodifying Which-Clause (Leung, 2010) above are analyzed as non-restrictive and supplementary clauses following the matrix clause. They are not treated as post-nominal relative clauses in an NP in this paper.

14. ^In the relevant psycholinguistic literature, it has been widely agreed that bilinguals co-activate words in both languages even though they are speaking only one language (Green, 1986; Kroll and Ma, 2017). Different patterns of language use—in either language or in different patterns of code-switching—are results of the bilinguals controlling and inhibiting resources from either languages in their output (Green and Li, 2014).

15. ^I leave open other factors which may favor the triggering of a syntactic pattern via a co-activated word; for instance, the speakers may well be in a mode in which the non-selected language (i.e., English in this case) is more active (Green and Li, 2014).

16. ^The Principle of Economy (Li, 1999) has been taken for granted in this paper rather uncritically, though, obviously, there is much room for discussion. In my understanding, it is a simplistic generalization based on observations on some code-switched patterns which appear to be more economical (i.e., invoking fewer words/morphemes) than their monolingual Cantonese counterparts. However, it is not clear if code-switched constructions are always more economical than their Cantonese counterparts. Furthermore, there is little evidence for bilinguals comparing a code-switched construction and its Cantonese equivalent when they engage in code-switching.

17. ^Either based on the author's own intuition/experience or the smaller number of studies in which these constructions are documented.

18. ^Yip and Matthews (2000, 2007) focused on syntactic transfer—akin to what I call structural (or constructional) borrowing here—between Cantonese and English of bilingual children in Hong Kong. They identified a wide range of constructions being borrowed from one language to another. Although the direction of transfer is primarily from Cantonese to English due to the dominance of Cantonese in the input and the environment, these works somehow testify to the possibilities of structural (or constructional) borrowing beyond the three constructions discussed here.

19. ^Various strands of evidence testify to the vitality of Cantonese in Hong Kong, including the latest 2011 census and 2016 by-census results, in which Cantonese has been the most widely spoken home/usual language (as cited in Bolton et al., 2020, p. 454), and the ideology that Chinese people in Hong Kong should speak Cantonese among themselves (Chen, 2008). Also see Note 18 above.

References

Bauer, R. S. (2006). The stratification of English loanwords in Cantonese. J. Chin. Linguist. 34, 172–191.

Bolton, K. (2003). Chinese English: A Sociolinguistic History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bolton, K., Bacon-Shone, J., and Luke, K.-K. (2020). “Hong Kong English,” in The Handbook of Asian Englishes, eds W. Botha and A. Kirkpatrick (Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley and Sons), 449–478.

Chan, B. H.-S. (1992). Code-mixing in Hong Kong Cantonese-English Bilinguals: constraints and processes (M.A. Dissertation). The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China.

Chan, B. H.-S. (1998). “How does Cantonese-English code-mixing work?,” in Language in Hong Kong at Century's End, ed M. C. Pennington (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press), 191–216.

Chan, B. H.-S. (2015). A diachronic-functional approach to explaining grammatical patterns in code-switching: postmodification in Cantonese–English noun phrases. Int. J. Bilingualism 19, 17–39. doi: 10.1177/1367006913477921

Chan, B. H.-S. (2018). Single-word English prepositions in Hong Kong Cantonese: a cognitive-constructionist approach. Chin. Lang. Discourse 9, 46–74. doi: 10.1075/cld.17013.cha

Chan, B. H.-S. (2021). “Language contact phenomena in Hong Kong Cantonese: what after code-switching and lexical borrowing?,” in Crossing-Over: New Insights Into the Dialects of Guangdong, eds C. L. Tong and J. Kuong (Macau: Hall de Cultura), 149–164.

Chan, M., and Kwok, H. (1982). A Study of Lexical Borrowing From English in Hong Kong Cantonese. Hong Kong: Centre of Asian Studies, University of Hong Kong.

Chen, K. H.-Y. (2005). “The social distinctiveness of two code-mixing styles in Hong Kong,” in ISB4: Proceedings of the 4th International Symposium on Bilingualism, eds J. Cohen, K. T. McAlister, K. Rolstad, and J. MacSwan (Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Press), 527–541.

Chen, K. H.-Y. (2008). Positioning and repositioning: Linguistic practices and identity negotiation of overseas returning bilinguals in Hong Kong. Multilingua 27, 57–75. doi: 10.1515/MULTI.2008.004

Chen, K. H.-Y. (2015). “Styling bilinguals: analyzing structurally distinctive code-switching styles in Hong Kong,” in Code-Switching Between Structural and Sociolinguistic Perspectives, eds G. Stell and K. Yakpo (Berlin; Munich; Boston: Walter de Gruyter), 163–183.

Gibbons, J. (1987). Code-Mixing and Code-choice: A Hong Kong Case Study. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Green, D. W. (1986). Control, activation, and resource: a framework and a model for the control of speech in bilinguals. Brain Lang. 27, 210–223. doi: 10.1016/0093-934X(86)90016-7

Green, D. W., and Li, W. (2014). A control process model of code-switching. Lang. Cogn. Neurosci. 29, 499–511. doi: 10.1080/23273798.2014.882515

Huddleston, R., Pullum, G., and Peterson, P. (2002). “Relative constructions and unbounded dependencies,” in The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language, R. Huddleston and G. Pullum (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 1031–1096.

Kroll, J. F., and Ma, F. (2017). “The bilingual lexicon,” in The Handbook of Psycholinguistics, eds E. M. Fernández and H. S. Cairns (Oxford: John Wiley and Sons), 294–319.

Langacker, R. W. (2008). Cognitive Grammar: A Basic Introduction. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Leung, K.-W. (2010). Lexicosyntactic transference in Cantonese-English code-switching: the case of which-relatives (M.A. Dissertation). The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China.

Leung, T. T.-C. (2001). An optimality-theoretic approach to Cantonese/English code-switching (M.Phil. Dissertation). The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China.

Leung, Y.-B. (1987). Constraints on intrasentential code-mixing in Cantonese and English (M.A. Dissertation). The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China.

Li, D. C.-S. (1999). Linguistic convergence: impact of English on Hong Kong Cantonese. Asian Englishes 2, 5–36. doi: 10.1080/13488678.1999.10801017

Li, D. C.-S. (2000). Cantonese-English code-switching research in Hong Kong: a Y2K review. World Englishes 19, 305–322. doi: 10.1111/1467-971X.00181

Li, D. C.-S., Wong, C. S.-P., Leung, W.-M., and Wong, S. T.-S. (2016). Facilitation of transference: The case of monosyllabic salience in Hong Kong Cantonese. Linguistics 54, 1–58. doi: 10.1515/ling-2015-0037

Li, W. (2018). Translanguaging as a practical theory of language. Appl. Linguist. 39, 9–30. doi: 10.1093/applin/amx039

Luke, K.-K. (1998). The post-modification of noun phrases in Cantonese (粵語名詞組中的後置修飾語). Fangyan (方言) 1, 48–52.

Luke, K.-K., and Lau, C.-M. (2005). On loanword truncation in Cantonese. J. East Asian Ling. 17, 347–362. doi: 10.1007/s10831-008-9032-x

Matthews, S., and Yip, V. (2011). Cantonese: A Comprehensive Grammar. Second edition. New York, NY: Routledge.

Muysken, P. (2000). Bilingual Speech: A Typology of Code-Mixing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Myers-Scotton, C. (1993). Dueling Languages: Grammatical Structure in Codeswitching. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Otheguy, R., García, O., and Reid, W. (2015). Clarifying translanguaging and deconstructing named languages: a perspective from linguistics. Appl. Linguist. Rev. 6, 281–307. doi: 10.1515/applirev-2015-0014

Otheguy, R., García, O., and Reid, W. (2019). A translanguaging view of the linguistic system of bilinguals. Appl. Linguist. Rev. 10, 625–651. doi: 10.1515/applirev-2018-0020

Poplack, S. (1988). “Contrasting patterns of code-switching in two communities,” in: Codeswitching: Anthropological and Sociolinguistic Perspectives, ed M. Heller (Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter), 215–255.

Poplack, S. (2018). Borrowing: Loanwords in the Speech Community and in the Grammar. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Reynolds, S. (1985). Code-switching in Hong Kong (M.A. Dissertation). University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China.

Schiffrin, D. (1987). Discourse Markers (Studies in Interactional Sociolinguistics). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Setter, J., Wong, C. S.-P., and Chan, B. H.-S. (2010). Hong Kong English. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Silverstein, M. (2003). Indexical order and the dialectics of sociolinguistic life. Lang. Commun. 23:193–229. doi: 10.1016/S0271-5309(03)00013-2

Thomason, S. G., and Kaufman, T. (1988). Language Contact, Creolization, and Genetic Linguistics. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Wong, C. S.-P., Bauer, R., and Lam, Z. (2009). The Integration of English loanwords in Hong Kong Cantonese. J. Southeast Asian Linguist. Soc. 1, 251–265.

Yip, V., and Matthews, S. (2000). Syntactic transfer in a Cantonese-English bilingual child. Bilingualism Lang. Cogn. 3, 193–208. doi: 10.1017/S136672890000033X

Keywords: Cantonese-English contact, code-mixing/code-switching, constructional borrowing, lexical borrowing, structural borrowing, translanguaging

Citation: Chan BH-S (2022) Constructional Borrowing From English in Hong Kong Cantonese. Front. Commun. 7:796372. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2022.796372

Received: 16 October 2021; Accepted: 30 March 2022;

Published: 19 May 2022.

Edited by:

Peter Siemund, University of Hamburg, GermanyReviewed by:

Zhiming Bao, National University of Singapore, SingaporeLijun Li, University of Kiel, Germany

Copyright © 2022 Chan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Brian Hok-Shing Chan, YmhzY2hhbkB1bS5lZHUubW8=

Brian Hok-Shing Chan

Brian Hok-Shing Chan