- 1School for Mass Communication Research, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium

- 2School of Communication, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, United States

Themes of death and grief emerge in media entertainment in ways that are both poignant and humorous. In this experimental study, we extend research on eudaimonic narratives about death to consider those that are hedonic. Participants read a story about a woman giving a eulogy for her friend that was manipulated to be either poignant-focused or humor-focused, and answered questions about their responses to the story, feelings of connectedness with others, and death acceptance. The narrative conditions elicited similar levels of narrative engagement and appreciation, but the humor-focused narrative elicited more enjoyment than the poignant-focused narrative. Connectedness did not differ between conditions. However, the humor-focused narrative elicited more death acceptance when controlling for participants' personal loss acceptance and grief severity, and individual differences in the dark tetrad personality traits, trait depression, and religious upbringing. We tested these effects in an integrated path model and found that the model fit the data well and the narrative pathways explained variance in both death acceptance and connectedness. Our findings have implications for how death and grief are depicted in media entertainment: namely, that death is an inherently poignant topic and the addition of humorous elements in bereavement narratives may be especially effective in increasing death acceptance.

Introduction

“Life is only worth a damn because it's short. It's designed to be used, consumed, spent, lived, felt. We're supposed to fill it with every mistake and miracle we can manage.

And then, we're supposed to let go.”

– Pierce's mom, Community

In the episode, “The Psychology of Letting Go” of Community, character Pierce copes with the passing of his mother by insisting that in fact she is not dead but vaporized and being stored in an “energon pod” (a lava lamp) until she returns in a couple of years. His friends are unable to convince him that his mother is really gone, but he later finds a recording that his mother made for him before she died. In it, she insists that she is dead, not vaporized, and “that's how I like it.” She asks Pierce to accept that, tells him she loves him, and says goodbye.

Communication scholars have long proposed that stories can provide safe and consequence-free realms for audiences to approach real-world topics, including those that are emotionally taxing (Mar and Oatley, 2008; Slater et al., 2014; Green and Fitzgerald, 2017; Menninghaus et al., 2017; Fitzgerald et al., 2019). A growing body of research has explored how narratives can offer opportunities for audiences to cope with the topics of death and grief (Cox et al., 2005; Rieger et al., 2015; Rieger and Hofer, 2017; Slater et al., 2018; Fitzgerald et al., 2020; Das and Peters, 2022). This research has primarily focused on eudaimonic media experiences such as self-transcendent narratives and how these experiences can help reduce the fear of death (Rieger et al., 2015), foster loss acceptance (Hofer, 2013; Slater et al., 2018), and increase feelings of connectedness with others (Janicke-Bowles and Oliver, 2017; Das and Peters, 2022). This work has clear implications for the well-being of narrative audiences, particularly among those who have experienced personal loss. Yet, it remains unclear whether these findings are specific to narrative experiences that are eudaimonic in nature (i.e., those that focus on poignancy) or if another type of narrative experience (i.e., hedonic, or those that focus on light humor and pleasure) can also help individuals cope with death and grief.

In this study, we extend the body of research on what we refer to as bereavement narratives, or stories about death and grief, to compare a version of a story about death that has a focus on poignancy to a version that has a focus on humor, and assess their effect on death acceptance and connectedness in individuals who have experienced personal loss. We propose that both poignant-focused and humor-focused bereavement narratives can provide pathways to death acceptance and connectedness through narrative processes. We further propose that the effect of the narrative may depend on individual differences in personality, including the dark tetrad personality traits, trait depression, and religious upbringing, as well as the characteristics of one's grief, including acceptance of personal loss and severity of grief, in line with previous research (Das and Peters, 2022). To examine these questions, we test a path model of the effects of narrative condition on death acceptance and connectedness through narrative engagement and appraisal. Prior to reporting the current study, we provide a theoretical backdrop to our hypotheses and review the state of the literature related to bereavement narratives.

Coping with death and grief through narratives

The thought of death can evoke anxiety and existential dread (e.g., see Terror Management Theory; TMT; Pyszczynski et al., 1997; see also Greenberg et al., 1986), and bereavement of a close personal loss can be an especially difficult life event (Ott, 2003). Individuals turn to cultural and psychological defenses to manage the anxiety of death, but these coping mechanisms can lead to a variety of negative outcomes such as favoritism toward ingroup members and derogation of outgroup members (See and Petty, 2006). As such, it is important to promote constructive coping strategies for processing death and grief. Narrative entertainment may be an especially effective approach to promoting new and adaptive ways of coping because stories involve a unique combination of elements in which they can be both psychologically distant and highly engaging. This combination has been referred to as a “distancing-embracing” function (Menninghaus et al., 2017; see also Mar et al., 2006).

The distancing-embracing function of narratives

The Distancing-Embracing model (Menninghaus et al., 2017) was initially proposed to explain how negative emotions in art can be positively experienced. Distancing factors like fiction and art schema in mediated content help to keep negative emotions at a psychological distance, thereby providing a sense of safety for individuals to emotionally approach sad or tragic content. Distancing factors interact with embracing factors such as the interplay of positive and negative emotions and audiences' ability to construct meaning from the content to influence subsequent enjoyment. Thus, fictional stories may be particularly useful in instances where the events of real life are too distressing and have the potential to overwhelm individuals (Green and Fitzgerald, 2017).

Current theorizing in narrative and media entertainment, particularly the Temporarily Expanding the Boundaries of The Self (TEBOTS) model (Slater et al., 2014), is consistent with this proposition. The TEBOTS model suggests that narratives can provide an instrument through which audiences can alleviate life's psychological demands and burdens (Slater et al., 2014). This model helps to explain why we feel gratified and psychologically rewarded by narratives. It connects self-expansion—a fundamental human response to the constraints on one's agency, autonomy, and affiliation (Johnson et al., 2016, p. 387)—with the world of narrative, which can fulfill self-expansion needs. Stories allow audiences to encounter experiences that extend beyond the constraints of their normal life, such as forming new and complicated relationships, simulating social situations, experiencing events in different times and places, or imagining what it is like to have different personal characteristics from their real self (Mar et al., 2006; Slater et al., 2014; Johnson et al., 2016).

In addition to their distancing-embracing and self-expansion functions, narratives are especially effective tools for influencing attitudes and perspectives because they can be highly engaging and often elicit positive appraisal.

Processes of narrative reception

Narrative engagement

Three mechanisms of narrative engagement consistently emerge in the literature as playing a key role in narrative influence and persuasion. First, transportation describes the experience of immersion into the world of story, in which audiences become mentally and emotionally invested in the narrative's characters and events (Green and Brock, 2000). When transported, individuals become more likely to be persuaded by a story because their attention is focused more on understanding and enjoying the unfolding plot than on scrutinizing persuasive claims of the narrative.

A second mechanism of narrative engagement is identification (Cohen, 2001; Sestir and Green, 2010), in which narratives are engaging to the extent that audiences identify with story characters. The more individuals identify with characters, the more their attitudes and behavioral intentions align with those advocated by the characters in the story. Audiences who also closely identify with story characters become more likely to adopt the beliefs and perspectives advocated because they are more capable of envisioning the world of the story through the eyes of that character. For instance, if a story character promotes a worldview that involves a higher degree of connectedness, the audience may also adopt a more connected worldview (Das and Peters, 2022).

The third mechanism of narrative engagement that has emerged in the narrative and media literature is emotional flow, or the emotional shifts individuals experience over the course of a narrative (Nabi and Green, 2015). For instance, these shifts can be experienced as changes in the intensity or valence of emotions as the plot unfolds, or changes between discrete emotions as story characters suffer and overcome hardship (Nabi, 2015; Nabi and Green, 2015). Emotional flow aids in the sustained attention and elaboration of the story, and thus also enhances the influence of a narrative on post-message attitudes (Nabi and Green, 2015).

In addition to narrative engagement, the extent to which audiences positively evaluate the content may also have ramifications for the story's impact.

Narrative appraisal

How a narrative is mentally and emotionally processed during story reception plays an important role in determining the story's impact on audiences, but so too does the appraisal of the narrative experience. At its earliest conception in media entertainment research, enjoyment was described as audiences' feelings of delight or enlightenment (Vorderer et al., 2004). More recently, enjoyment has come to describe mostly hedonic experiences with media, whereas more eudaimonic experiences have been differentiated as appreciation (Oliver et al., 2014). While both responses involve a positive appraisal of the narrative, enjoyment is characterized by predominantly positive emotions (e.g., light humor) whereas appreciation is characterized by mixed emotions (e.g., poignancy; Oliver and Bartsch, 2010).

Through engagement and appraisal processes, narratives may prove useful tools in promoting positive coping mechanisms in response to death and bereavement. Some research has begun to examine this potential.

Past research on narratives, death, and bereavement

Research on death in narrative media entertainment and its use for coping with death anxiety and grief has centered around how eudaimonic or meaningful media1 experiences can help ease existential fears and encourage more accepting views of death.

In a first experimental study in this area, Hofer (2013) found that inducing mortality salience, or increasing one's awareness of their own death, was positively associated with appreciation of a meaningful film for those more inclined to search for meaning in life.

Other studies have similarly found that eudaimonic media can serve as an inspiration for generating meaning (Rieger and Hofer, 2017) and an anxiety buffer against the fear of death (Rieger et al., 2015; Slater et al., 2018). In a study particularly relevant to the current research, Das and Peters (2022) expanded the proponents of TEBOTS to describe how self-transcendence in stories (i.e., experiences in which audiences transcend themselves as individuals to view life in a way that is more elevated and connected to others and a larger “whole”; Janicke-Bowles and Oliver, 2017) can be “safe havens” for those who have/are experiencing a personal loss (Das and Peters, 2022, p. 323). The authors proposed that bereaved audiences may seek refuge from their grief in narratives. As a result, the narrative helps them vicariously experience loss acceptance and develop new perspectives of death and grief through the experiences of the narrative characters. Indeed, the results of the study suggested that transcendent narratives resonate with grieving individuals. Participants experienced increased engagement with and appreciation of the story, especially when their grief was severe, as well as increased elevation and connectedness, especially when grief was less severe.

Thus, certain narrative experiences seem to help individuals cope with death and loss, but this research has not been extended to narratives outside of eudaimonic media. Although we tend to think of death as a serious topic, it is often depicted in media entertainment in ways that are light, humorous, and hedonically enjoyed. In an exploratory study of death depictions in entertainment media, Fitzgerald et al. (2020) found that death scenes can elicit both eudaimonic responses—characterized by poignancy—and hedonic responses—characterized by fun and pleasure. Participants were asked to think about a death scene in a narrative that they found particularly meaningful, pleasurable, or memorable (an added control condition; see footnote 1 regarding the use of the term “meaningful”). Although death in narratives was generally remembered as a poignant experience, death scenes that were considered as “fun” or “a good time” were also easily recalled. Thus, bereavement narratives that use humor may also be effective in promoting adaptive coping of death and grief.

Humor as a coping mechanism

Humor has been identified as an adaptive way to cope with life's stressful events, particularly because it can suppress the effects of anxiety on mental health (e.g., Merz et al., 2009; Demjén, 2016; Eden et al., 2020). In a recent study, Morgan et al. (2019) found that humor may even buffer existential anxiety: when one's mortality was made salient to them, individual differences in the use of humor to cope with stress appeared to buffer against death-thought accessibility. This was particularly true for individuals low in trait coping humor, suggesting that humor could be an effective avenue for facing existential fears even among those who do not tend to use humor to cope. Moreover, humor can be used as a persuasive tool within narrative media messages. For example, a recent study found that humor appeals can influence beliefs and perceived risk in a media message about climate change (Skurka et al., 2022). Because humor is more closely associated with hedonic enjoyment, we would expect that the pathways through which hedonic narrative influence outcomes differ from those of eudaimonic narratives.

Proposing eudaimonic and hedonic pathways in bereavement narratives

In Fitzgerald et al. (2020), responses to narrative death scenes were found to be associated with distinct processes of narrative engagement and appraisal: meaningful death scenes were rated as being more engaging (i.e., through narrative transportation, Green and Brock, 2000; and character identification, Cohen, 2001; see supplemental analyses in Fitzgerald et al., 2020) compared to pleasurable death scenes. With regard to bereavement narratives, we would similarly expect that individuals transported in a story about death would be more open to accepting the notion that death is an inevitable part of life, if the story presents this perspective. Bereaved individuals may also connect to characters in a story who have also recently lost a loved one and vicariously process their grief through the bereavement of that character. Moreover, experiencing greater emotional flow in bereavement narratives may prolong the impact of the story on their emotions after the fact, which may contribute more to agreement with perspectives about death and grief that were advocated in the story. Taken together, the overall engagement in a story about loss should affect attitudes about death and grief in line with how they are depicted in the story. In particular, we propose the following hypothesis regarding narrative engagement:

H1: A poignant-focused bereavement narrative will elicit more narrative engagement overall compared to a humor-focused bereavement narrative.

Fitzgerald et al. (2020) further found that meaningful death scenes were associated more with narrative appreciation (being rated as meaningful, moving, and thought-provoking; Oliver and Bartsch, 2010) whereas pleasurable death scenes were more associated with narrative enjoyment (being rated as fun, entertaining, and a good time; Oliver and Bartsch, 2010). Regarding narrative appraisal, we would expect that appraisal responses to bereavement narrative would depend on the themes or focus of that narrative. In particular, we propose the following hypothesis regarding enjoyment and appreciation responses:

H2: A humor-focused narrative will elicit more enjoyment than a poignant-focused narrative (H2a); whereas a poignant-focused narrative will elicit more appreciation than a humor-focused narrative (H2b).

Through these engagement and appraisal processes, both poignant-focused and humor-focused bereavement narratives may influence narrative-based outcomes related to the well-being of those who have experienced personal loss. We propose that connectedness—the sense of being connected with humanity and part of a bigger whole (Janicke-Bowles and Oliver, 2017; Oliver et al., 2018; Das and Peters, 2022)—and a peaceful acceptance of death (Prigerson and Maciejewski, 2008) may be especially relevant outcomes for the emotional well-being of those processing death and grief.

Death acceptance and connectedness

First, difficulty accepting death can have negative consequences for the well-being of the bereaved (Neimeyer and Currier, 2009). Some research has found that those with prolonged grief or an inability to accept loss are at a heightened risk for stress and depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, suicidal ideation, functional disability and diminished quality of life (Lichtenthal et al., 2004; Prigerson et al., 2008). By contrast, peaceful acceptance of loss in which an individual confronts death with peace and equanimity (Prigerson and Maciejewski, 2008, p. 435), may help to alleviate the emotional pain associated with loss (Maciejewski et al., 2007). In a longitudinal study on the emotional pain and acceptance of loss in bereaved individuals, Maciejewski et al. (2007) found that an increase in peaceful acceptance of loss was associated with a decline in grief-related distress. The researchers concluded that “research that determines ways to promote peaceful acceptance offers the promise of offsetting the pain and misery frequently associated with dying and death” (Prigerson and Maciejewski, 2008, p. 437).

In addition to death acceptance, feeling connected with others and something greater (Janicke-Bowles and Oliver, 2017) may be another outcome of bereavement narratives that has implications for individuals' well-being. Das and Peters (2022) proposed that a connected, transcendent view of life may be relevant for the cognitive adjustment process of the bereaved (p. 321), and their findings suggested that a connected worldview seems to be a part of the grief experience (p. 338). Feeling connected with others may reduce the potential for the bereaved to feel alone or isolated in their grief because it encourages a sense of belonging and wholeness (Kelly, 1995). Connectedness may also contribute to eudaimonic well-being. For instance, some research has found that media which evokes connectedness also tends to evoke feelings of transcendence and an increased salience of spiritual beliefs related to self-actualization (Janicke-Bowles and Ramasubramanian, 2017).

Thus, we propose the following research questions regarding death acceptance and connectedness:

RQ1: Will a poignant-focused narrative or a humor-focused narrative have a stronger effect on death acceptance?

RQ2: Will a poignant-focused narrative or a humor-focused narrative have a stronger effect on connectedness?

Finally, outcomes of bereavement narratives may depend on certain individuating characteristics of the audience.

Individual differences regarding bereavement narratives

The influence of eudaimonic vs. hedonic depictions of death in narratives may differ between individuals. For example, eudaimonic media may resonate more with some individuals than others (Janicke-Bowles et al., 2021). Individual differences in the “dark tetrad” anti-social personality traits (e.g., narcissism, Machiavellianism, psychopathy, and sadism; Jonason and Webster, 2010; Appel et al., 2019) have been linked with more negative evaluations of eudaimonic media. Those high in these traits may view the media as being corny and inauthentic, and therefore are less likely to be moved by eudaimonic depictions of death in narratives. Other research suggests that individual differences in trait depression and religious upbringing affect the likelihood that eudaimonic or meaningful media will be appreciated (Das and Peters, 2022). These individual differences also have close ties with perspectives of death and grieving (Wortmann and Park, 2008). Thus, considering these differences, we propose the following research question regarding individual differences:

RQ3: Will the effectiveness of poignant-focused and humor-focused bereavement narratives depend on individual differences in the dark tetrad (RQ3a), trait depression (RQ3b), or religious upbringing (RQ3c)?

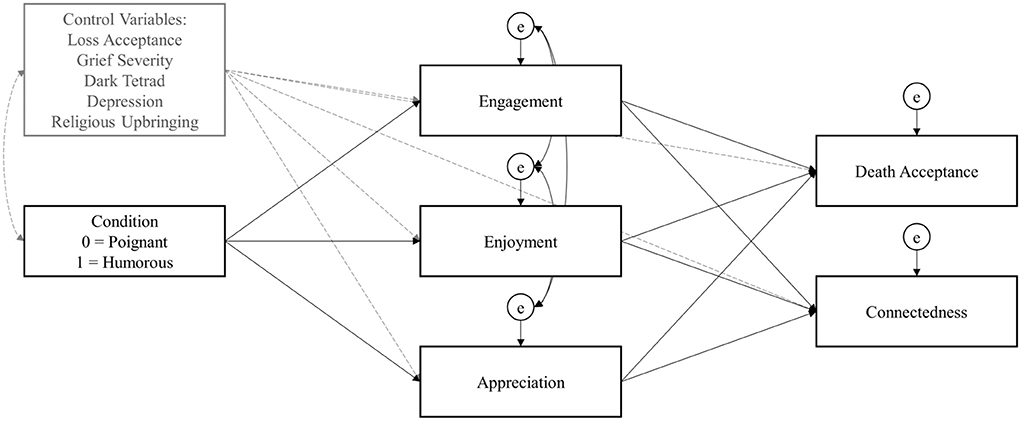

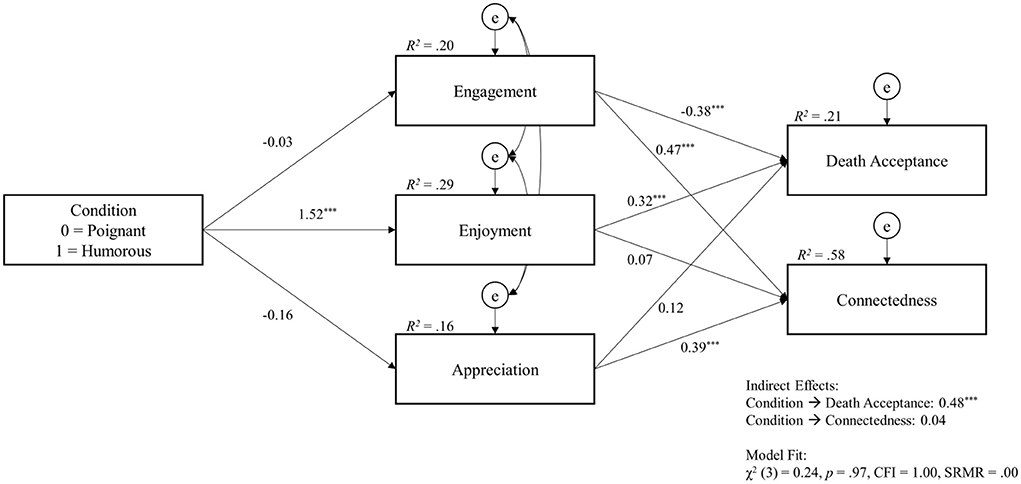

Finally, to account for any indirect effects of humor-focused and poignant-focused narratives on outcomes of death acceptance and connectedness through narrative engagement and appraisal processes, we propose a path model (Figure 1). The model accounts for pathways on narrative engagement (transportation, identification, emotional flow), narrative enjoyment and appreciation, and well-being outcomes, and, assesses how those effects differ when controlling for loss-related and individual trait difference. Moreover, we propose the final research question:

RQ4: Do narrative engagement and appraisal processes mediate the effect of humor-focused and poignant-focused narratives on death acceptance and connectedness?

Method

To test our hypotheses and research questions, we compared a poignant-focused and humor-focused version of a narrative about death and grief.

Participants and procedure

A total of 330 participants were collected via Amazon's Mechanical Turk. After providing consent, participants were randomly assigned to read a narrative about a woman giving a eulogy for the passing of her close friend at her funeral. We manipulated the story to be either poignant-focused or humor-focused (both narrative versions are available to read in our online supplement: https://bit.ly/3b9Nuwe)2. After the narrative, participants completed a series of measures which assessed (a) their narrative engagement and narrative appraisal; (b) death acceptance and connectedness; (c) loss-related and trait covariates; and (d) demographics.

We utilized three criteria for participant exclusion. First, we excluded participants if they did not have complete data across the main variables. Thus, 30 participants were dropped due to incomplete data. Second, we excluded participants based on two manipulation check items. These items asked about specific details of the narrative (e.g., “Where did [main characters] get married?”). Participants were excluded if they incorrectly answered either one of these checks. Consequently, 35 participants were excluded due to incorrect responses. Finally, we excluded participants if they had not experienced the loss of a loved one. Among our sample, 24 participants reported they hadn't experienced the loss of a loved one and were thus excluded. Our final sample consisted of 241 participants (nPoignant−focused = 120, nHumor−focused = 121), and a chi-square analysis indicated that these exclusion criteria did not systematically alter random assignment to either condition, χ2 = 0.015, p = 0.90.

Measures

Narrative variables

Narrative engagement

To assess overall narrative engagement, we measured the three narrative engagement processes. Transportation was measured with the 5-item transportation scale short form (TS-SF; Appel et al., 2015), including items such as “I could picture myself in the scene of the events described in the narrative” rated on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 7 (very much). To measure identification, we utilized the 3-item measure of character identification used in Sestir and Green (2010), adapted from Cohen (2001), with items such as “When reading the story, I wanted the character to succeed in achieving her goals” rated on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 7 (very much). Lastly, to measure emotional flow, we used a 4-item emotional flow scale, including items such as “I experienced a lot of different emotions” rated on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

To assess the validity of these constructs, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using a first-order, multidimensional factor structure. The measurement model demonstrated good fit and each scale had good reliability, χ2(df ) = 171.55(51), CFI = 0.94, SRMR = 0.05, αTransportation = 0.82, αIdentification = 0.81, αEmotionalFlow = 0.95. Given the high positive correlations between the scales (r = 0.79–0.88), the theoretical similarity of the processes, and to reduce the potential for collinearity of the scales when testing them within the hypothesized path model, we combined the three scales into a single composite that represented participants' overall narrative engagement (αEngagement = 0.88).

Enjoyment and appreciation

To measure narrative appraisal, we utilized Oliver and Bartsch's (2010) 3-item enjoyment scale and 3-item appreciation scale. Participants read the prompt, “The story was…” followed by enjoyment items (“fun,” “a good time,” “entertaining”) and appreciation items (“meaningful,” “moving,” “thought-provoking”) which they rated on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Using a first-order, multidimensional factor structure, the measurement model demonstrated adequate fit, χ2(df ) = 47.35(8), p < 0.001, CFI = 0.95, SRMR = 0.09, and the reliabilities for each scale were good (αEnjoyment = 0.87; αAppreciation = 0.85).

Outcome variables

Death acceptance

We used Slater et al.'s (2018) 11-item scale of death acceptance as our first well-being outcome. Example items include “Some people are frightened of death, but I am not” and “I am more afraid of death than old age” (reverse-scored). The measurement model using all 11 scale items did not fit well, χ2(df ) = 313.41(44), p < 0.001, CFI = 0.83, SRMR = 0.09. Therefore, we engaged in selective item retention to achieve satisfactory model fit. After removing items 9, 10, and 11, the measurement model demonstrated good fit and the scale had excellent reliability, χ2(df ) = 74.65(20), p < 0.001, CFI = 0.95, SRMR = 0.04 (α = 0.92).

Connectedness

For our second well-being outcome, we used Janicke-Bowles and Oliver's (2017) connectedness scale. The connectedness scale is a 26-item scale used to measure connectedness to close others, connectedness to a higher power, and connectedness to one's family. We used the first nine items of the scale to measure one's connectedness toward close others. Example items included “[The story] made me think about the power of love” and “[The story] made me cherish the people in my life.” The measurement model demonstrated adequate fit, χ2(df ) = 227.01(27), p < 0. 001, CFI = 0.92, SRMR = 0.04, and the scale had excellent reliability (α = 0.96).

Loss-related covariates

Loss acceptance and grief severity

Similar to Das and Peters (2022), we sought to control for the impact of one's experienced loss on our manipulation. The first measure we used was a 6-item scale of loss acceptance. Example items included “At this moment, I am able to think about my deceased loved one with positive thoughts” and “I find it difficult to be happy without the person I lost” (reverse-scored). The second measure was a 3-item scale of grief severity. Example items included “There were times that I thought I would never be able to bear the loss” and “There were times that I lost my sense of meaning in life due to the loss”. Using a first-order, multidimensional factor structure, the measurement model demonstrated inadequate fit, χ2(df ) = 252.20(26), p < 0.001, CFI = 0.83, SRMR = 0.19, so we engaged in selective item retention. By removing items 2 and 4 from the loss acceptance scale, the measurement model fit well and both scales demonstrated good reliability, χ2(df ) = 37.89(13), p < 0.001, CFI = 0.98, SRMR = 0.06 (αLossAcceptance = 0.83; αGriefSeverity = 0.94).

Trait covariates

We measured three trait variables that might impact the effect of our manipulation.

Dark tetrad

We utilized a 19-item scale to measure the dark tetrad. This scale was a combination of the 12-item Dirty Dozen dark triad scale (DDS; Jonason and Webster, 2010; Appel et al., 2019), which measures one's trait Machiavellianism, psychopathy, and narcissism (Appel et al., 2019) and the 7-item Variety of Sadistic Tendencies scale (VAST; Paulhus and Jones, 2015), which measures one's trait sadism in close relationships. After assessing the model fit of each subscale, we tested a measurement model where we loaded the composite subscales onto a single latent variable. The measurement model fit well, and the scale had good reliability, χ2(df ) = 19.82(2), p < 0.001, CFI = 0.95, SRMR = 0.04 (α = 80).

Depression

We measured trait depression using a 6-item scale (Das and Peters, 2022). Example items include “In my life, I have experienced episodes of at least 2 consecutive weeks when I experienced little pleasure in activities” and “In my life, I have experienced episodes of at least 2 consecutive weeks when I had recurring thoughts about death and suicide.” The measurement model fit adequately, and the scale had excellent reliability, χ2(df ) = 91.68(9), p < 0.001, CFI = 0.94, SRMR = 0.06 (α = 0.93).

Religious upbringing

We assessed religious upbringing using a 6-item scale (Das and Peters, 2022). Example items include “I was raised religiously/spiritually” and “My parents strongly believe that there is life after death.” The measurement model fit well, and the scale demonstrated good reliability, χ2(df ) = 106.74(9), p < 0.001, CFI = 0.93, SRMR = 0.04 (α = 0.94).

Results

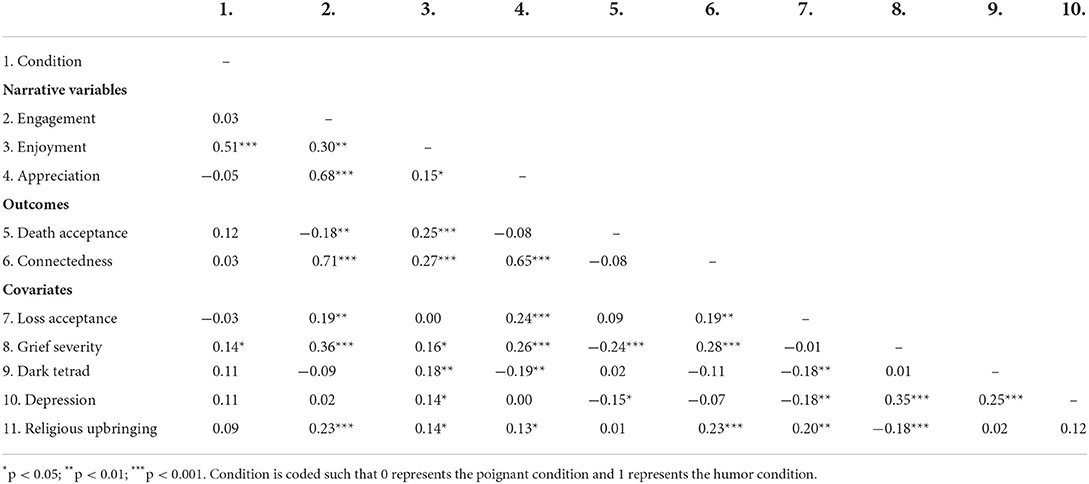

Bivariate relationships

We first examined the bivariate associations between our variables (see Table 1 for a correlation matrix of measured variables). A handful of notable patterns emerged. First, our manipulation had a strong positive correlation with enjoyment indicating that participants who read humor-focused version of our stimuli experienced more enjoyment than those who read the poignant-focused version. This association is in line with Fitzgerald et al. (2020) and the predicted effect of our manipulation. Second, we found a cluster of positive correlations between our narrative engagement, enjoyment, and appreciation variables. Specifically, we found that both narrative engagement and appreciation correlated significantly stronger with each other than with enjoyment (r = 0.68 to r = 0.30, Fisher's r-to-z transformation = 5.67, p < 0.001).

We also found distinct patterns between our narrative variables and each outcome. For death acceptance, we saw a positive correlation with enjoyment and a non-significant correlation with appreciation. We also saw a negative correlation with narrative engagement. For connectedness, we found positive correlations across all three narrative variables, with the engagement and appreciation correlations being significantly stronger than the enjoyment correlation (r = 0.65 to r = 0.27, Fisher's r-to-z transformation = 5.44, p < 0.001). Taken together, these correlations support the notion that different narrative pathways can be used to impact one's well-being. One's death acceptance seems to be primarily derived from the hedonic pathway (i.e., enjoyment), and one's feeling of connectedness seems to be derived from the eudaimonic pathway (i.e., appreciation). Finally, our covariates had a number of significant relationships with both the narrative and outcome variables, which indicates the necessity of controlling for these variables when testing our hypotheses.

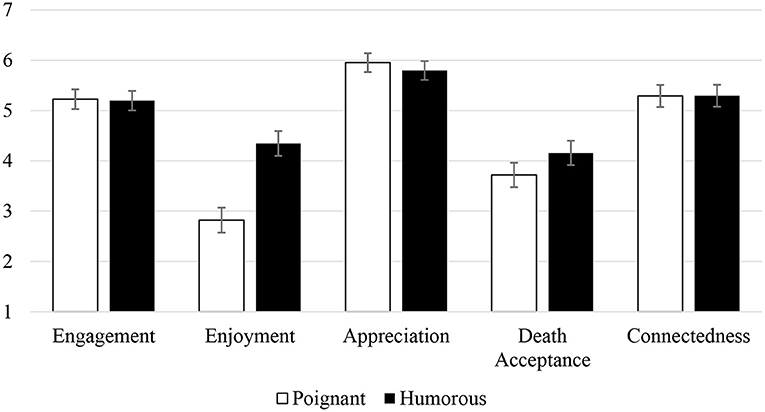

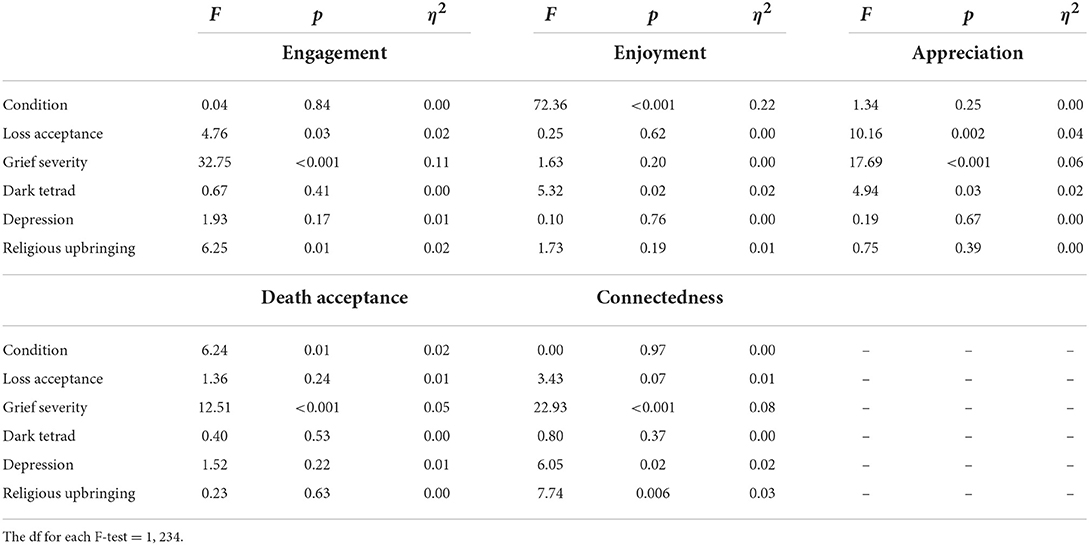

Effects of narrative condition

We tested our hypotheses using a multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA). We examined whether our manipulation impacted both our narrative variables and our outcome variables, while controlling for covariates. Narrative condition was entered as the fixed factor, narrative variables (engagement, enjoyment, appreciation) and outcome variables (death acceptance, connectedness) were entered as the dependent variables, and loss-related variables (personal loss, grief severity) and individual difference variables (dark tetrad, depression, religious upbringing) were entered as covariates. Results indicated a significant multivariate effect of condition [Wilks' Lambda = 0.74, F(5,230) = 16.61, p < 0.001, = 0.27]. Table 2 includes the between-subject effects of each predictor on the dependent variables, and Figure 2 provides a visual representation of the estimated marginal means of each dependent variable by condition.

Table 2. Between-subject MANCOVA effects of condition and covariates on mediators and outcome variables.

First, H1 predicted that the narrative conditions would differ in terms of narrative engagement, such that the poignant-focused narrative would elicit greater overall engagement than the humor-focused narrative. Results showed that engagement did not differ between the poignant-focused (EMM = 5.17, SE = 0.10) and humor-focused (EMM = 5.20, SE = 0.10) narratives. Thus, H1 was not supported, and we can conclude that participants processed the stories similarly regardless of whether it was intended to be more humorous or more poignant. H2a predicted that enjoyment would be higher in the humor-focused condition than in the poignant-focused condition. Enjoyment was significantly higher in the humor-focused narrative (EMM = 4.35, SE = 0.13) when compared to the poignant-focused version (EMM = 2.82, SE = 0.13). Thus, H2a was supported. H2b predicted that appreciation would be higher in the poignant-focused condition than in the humor-focused condition. Results indicated no significant difference between the poignant-focused (EMM = 5.95, SE = 0.10) and humor-focused conditions (EMM = 5.80, SE = 0.10). Thus, H2b was not supported. To this point, we note that appreciation was high in both conditions. This result may be due to the fact that stories about loss tend to be appreciated even when specifically intended to be humorous.

We additionally asked whether the poignant-focused or humor-focused narrative would elicit more death acceptance (RQ1) and connectedness (RQ2). Results indicated that death acceptance was significantly higher in the humor-focused condition (EMM = 4.16, SE = 0.12) than the poignant-focused condition (EMM = 3.72, SE = 0.12), suggesting that the more humorous narrative had an advantage over the more poignant narrative on affecting this outcome. Connectedness did not significantly differ between the poignant-focused (EMM = 5.29, SE = 0.11) and humor-focused conditions (EMM = 5.30, SE = 0.11). The connectedness results are consistent with Das and Peters (2022) and echo our findings regarding appreciation. Given the fact that connectedness was high in both conditions, it seems that participants may feel more connected to their loved ones when experiencing a narrative about death regardless of whether humor is intended or not.

We also asked whether any of the specified covariates would significantly impact our narrative and outcome variables (RQ3). Our multivariate effects indicated a significant effect of each covariate across the dependent variables featured in our model: loss acceptance [Wilks' Lambda = 0.95, F(5,230) = 2.46, p = 0.03, = 0.05], grief severity [Wilks' Lambda = 0.84, F(5,230) = 8.48, p < 0.001, = 0.16], dark tetrad [Wilks' Lambda = 0.95, F(5,230) = 2.57, p = 0.03, = 0.05], depression [Wilks' Lambda = 0.95, F(5,230) = 2.46, p = 0.03, = 0.05], and religious upbringing [Wilks' Lambda = 0.95, F(5,230) = 2.26, p = 0.05, = 0.05]. Thus, differences related to the characteristics of one's loss and the individual play a role in the engagement, appraisal, and effectiveness of bereavement narratives on one's well-being.

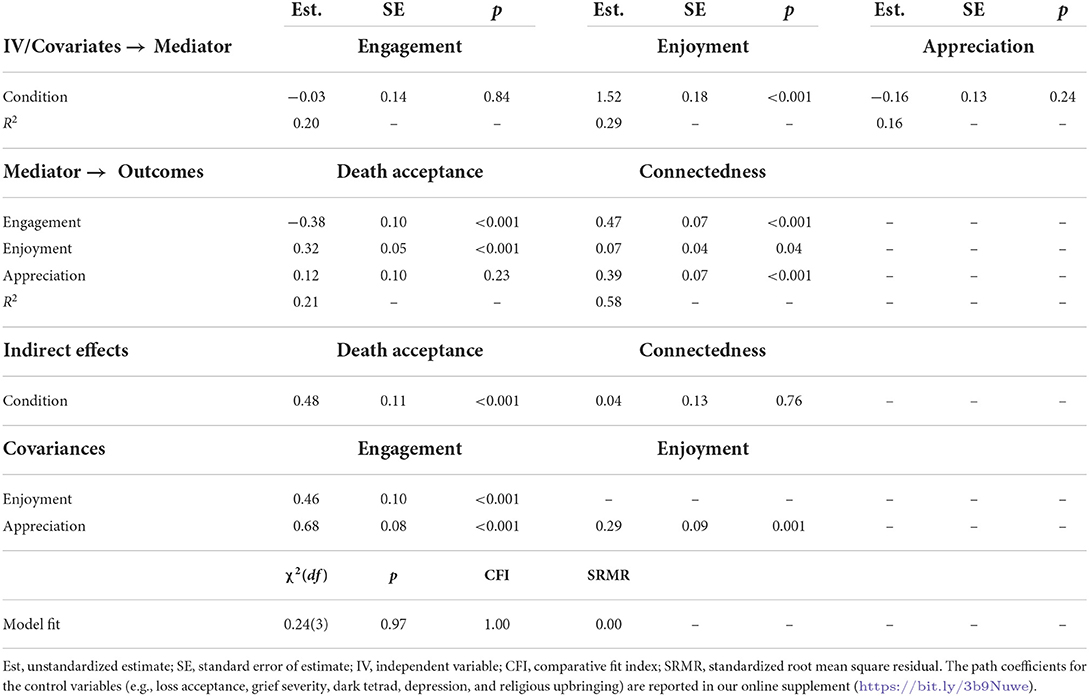

Hypothesized path model

Finally, RQ4 asked whether there would be indirect effects of the narrative condition on our outcomes through the narrative processes. We tested our model using maximum likelihood estimation in IBM Amos (Version 28). Indirect effects were estimated using 10,000 bootstrap samples and 95% bias-corrected CIs. Results of our model are included in Table 3 and Figure 3.

We found the model fit the data well and explained 21% of the variance in death acceptance and 58% of the variance in connectedness (see Table 3). For death acceptance, we found a significant indirect effect of our narrative manipulation. This result seems primarily driven by the positive direct effect of our condition on enjoyment and the positive direct effect of enjoyment on death acceptance. In other words, participants in the humor-focused condition experienced more narrative enjoyment which led to higher levels of general death acceptance. We note, additionally, that this indirect effect persisted even with the suppressing effect elicited by narrative engagement on death acceptance.

For connectedness, we found no indirect effect of our manipulation. When examining the direct effects of our mediators, it seems that changes in one's perceived connectedness were largely driven by their engagement and appreciation of the story. Thus, regardless of condition, participants who were more immersed and moved felt more connected to their loved ones. This finding again may be explained by the inherent meaningfulness of death. Experiencing death in a story leads audiences to be grateful for their loved ones, regardless of whether the story is meant to elicit humor or poignancy.

Discussion

In an experimental study, we examined how a poignant-focused vs. humor-focused story about loss affected general acceptance of death and feelings of connectedness among bereaved individuals. We found that audiences engaged with the narratives in a similar way regarding transportation, identification with characters, emotional flow, and appreciation, but the humor-focused narrative elicited greater enjoyment than the poignant-focused narrative. Moreover, the humor-focused narrative led to more death acceptance than the poignant-focused narrative. The results of our model test demonstrated that condition affected death acceptance indirectly, such that participants in the humor-focused condition experienced more narrative enjoyment which subsequently led to higher levels of general death acceptance. This finding suggests that our proposed hedonic narrative pathway through humor is worth exploring in addition to a eudaimonic one. We therefore recommend researchers continue to use this model in future studies examining bereavement narratives.

We found no differences between narrative versions for connectedness, consistent with Das and Peters (2022). However, our path model explained a high percent of the variance in connectedness, suggesting that bereavement narratives in general may promote self-transcendent feelings of being connected to others, given the inherent meaningfulness and phenomenological characteristics related to the topic of death. Further, it seemed from our model test that perceived connectedness was driven by narrative engagement and appreciation, and thus the experience of immersion and the perception of the narrative as poignant foster these feelings.

Our findings also underly the importance of considering individual differences in how bereavement narratives are processed. Each of the proposed individual difference variables emerged as a significant covariate of the effect of the story. First, the extent to which participants felt they had accepted the loss they had personally experienced, and the severity of their personal grief impacted how they experienced the story. This finding is consistent with past research (Das and Peters, 2022). It seems that grief is a highly individual experience, and that individualism extends to the realm of narratives. Personality traits (the dark tetrad and depression) and life experiences (religious upbringing) also played a role in how bereavement narratives were experienced. It may be interesting for future studies to directly assess the interplay of individual differences and narrative mechanisms, such as similarity to characters in the narrative, to explore whether marked similarities between the bereaved character and audience member impact how effectively the story influences perceptions and acceptance of death. For example, would a bereavement narrative about a character who lost a parent resonate more with an individual who was also grieving a parent? Such studies could help further identify how bereavement in narratives (and the characteristics of the bereaved) resonate with audiences differently, and how stories could be more effectively tailored to audiences.

The combination of humor and poignancy

Our current findings point to the idea that poignancy and humor in bereavement narratives do not appear to be orthogonal, but rather, they seem to complement one another in their effect on audiences. We note that our current stimuli, despite their ability to elicit significant differences in enjoyment, were unable to differentiate appreciation clearly. We attribute this result to the challenge of separating poignancy from the topic of death in general. A story about someone giving a eulogy is likely to evoke some poignancy even if the narrative is focused more on making audiences laugh or experience enjoyment. However, we also recognize that this finding may be due to our particular stimuli, and that perhaps other researchers would be more successful at crafting humorous stories about death that are not also experienced poignantly. Future research should continue to examine whether bereavement narratives can be made to elicit humor without also eliciting poignancy. If successful, such studies would be able to identify the potential benefits and downsides of humor vs. poignancy when used alone.

For instance, humor in media entertainment can be used to address serious topics in a way that is light-hearted (De Ridder et al., 2022), but humor alone might not be taken seriously. On the other hand, poignancy may be too serious and break down the distancing-embracing function of narratives that make them so effective at allowing audiences to approach negative topics. We encourage researchers to continue to assess whether a combination of humor and poignancy is best for bereavement narratives—and narratives about difficult topics in general. Some recent research suggests this is the case (De Ridder et al., 2022).

Limitations

There were some limitations in our current study that are worth noting. First, we only examined narrative effects in participants who expressed having experienced a personal loss. This included the large majority of our sample; however, it would be worthwhile to explore how our findings might differ for individuals who are less familiar with death and grief. For example, bereaved individuals may generally appreciate bereavement narratives more than those who have not experienced personal loss, and it may be possible to disentangle enjoyment and appreciation in humorous vs. poignant stories for these individuals. Similarly, narrative engagement may not play as key a role in death perceptions for individuals who are not bereaved.

Second, our findings suggest that grief is a very personal experience and although we tapped into some of the individual differences that influence the effect of bereavement narratives, there may be others that we did not consider. For instance, we asked participants to think of a single personal loss, or the person they were closest to, but we did not assess whether they had lost multiple loved ones. There may be individual differences related to familiarity with grief which may be considered in future studies. Other conditions of personal grief, such as whether the grief is disenfranchised, where the relationship, loss, or griever is not socially recognized (Doka, 1999) may be important to consider as well. Future research should also consider the time since the personal loss to explore how the temporal stages of grief might impact the effectiveness of narrative interventions3.

Conclusion

Death anxiety and bereavement can have lasting effects on well-being, yet both are an inevitable facet of life. In this study, we found that narratives are a good approach to increasing positive perspectives of death among the bereaved, and that humorous and poignant-centered approaches appear to complement each other. These findings help clarify the specific mechanisms that underlie how narratives can foster more acceptance of death: stories about loss and grief do not need to be heavy-handed with poignancy, as death is already inherently poignant. Instead, adding some humorous moments might make the content more consumable and more effective overall. For instance, returning to the episode of Community which opened this paper: after the heartfelt goodbye that Pierce's mother gave to him in her farewell recording, she “plays herself out” to a song akin to Top Gun's “Danger Zone.”

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: https://bit.ly/3b9Nuwe.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ohio State University. The Ethics Committee waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation.

Author contributions

KF, CF, and MG contributed to conception and design of the study and wrote sections of the manuscript. MG and CF organized the database. KF and CF performed the statistical analyses. KF wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This project was supported by internal funds provided to MG from The Ohio State University.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Elaine Paravati for her help in creating the narrative stimuli.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2022.973239/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^We note that the terms “meaningful,” “eudaimonic,” and “poignancy” are theoretically distinct and should not be used interchangeably. This is especially important to note in relation to the current study, as some narrative experiences that are hedonically enjoyed may also be meaningful to some viewers (e.g., parodies may use humor appeals that also evoke reflection of, or search for meaning in the content).

2. ^The conditions are not orthogonal such that the humor-focused condition has no poignancy and the poignancy-focused condition has no humor. Rather, we use these condition labels to denote that the humor-focused narrative has more of a focus that appeals to, or intends to evoke humor, and the poignant-focused narrative has more of a focus that appeals to, or intends to evoke poignancy.

3. ^As a supplemental measure, we asked participants in the current study how long it had been since their personal loss. We excluded this variable based on some concerns we had regarding the measurement and because we felt that grief severity would account for this individual difference. We note that there is no direct effect of this variable on any of our main variables, and no substantial changes to the significance, direction, or strength of our effects of interest (condition, narrative variables, death acceptance, and connectedness) when controlling for it.

References

Appel, M., Gnambs, T., Richter, T., and Green, M. C. (2015). The transportation scale–short form (TS–SF). Media Psychol. 18, 243–266. doi: 10.1080/15213269.2014.987400

Appel, M., Slater, M. D., and Oliver, M. B. (2019). Repelled by virtue? The dark triad and eudaimonic narratives. Media Psychol. 22, 769–794. doi: 10.1080/15213269.2018.1523014

Cohen, J. (2001). Defining identification: a theoretical look at the identification of audiences with media characters. Mass Commun. Soc. 4, 245–264. doi: 10.1207/S15327825MCS0403_01

Cox, M., Garrett, E., and Graham, J. A. (2005). Death in disney films: implications for children's understanding of death. OMEGA J. Death Dying 50, 267–280. doi: 10.2190/Q5VL-KLF7-060F-W69V

Das, E., and Peters, J. (2022). “They never really leave us”: transcendent narratives about loss resonate with the experience of severe grief. Hum. Commun. Res. 48, 320–345. doi: 10.1093/hcr/hqac001

De Ridder, A., Vandebosch, H., and Dhoest, A. (2022). Examining the hedonic and eudaimonic entertainment experiences of the combination of stand-up comedy and human-interest. Poetics 90:101601. doi: 10.1016/j.poetic.2021.101601

Demjén, Z. (2016). Laughing at cancer: humour, empowerment, solidarity and coping online. J. Pragmat. 101, 18–30. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2016.05.010

Eden, A. L., Johnson, B. K., Reinecke, L., and Grady, S. M. (2020). Media for coping during COVID-19 social distancing: stress, anxiety, and psychological well-being. Front. Psychol. 11, 577369. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.577639

Fitzgerald, K., Francemone, C. J., and Grizzard, M. (2020). Memorable, meaningful, pleasurable: an exploratory examination of narrative character deaths. OMEGA J. Death Dying. doi: 10.1177/0030222820981236. [Epub ahead of print].

Fitzgerald, K., Paravati, E., Green, M. C., Moore, M. M., and Qian, J. L. (2019). Restorative narratives for health promotion. Health Commun. 35, 356–363. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2018.1563032

Green, M., and Fitzgerald, K. (2017). Fiction as a bridge to action. Behav. Brain Sci. 40, 29–30. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X17001716

Green, M. C., and Brock, T. C. (2000). The role of transportation in the persuasiveness of public narratives. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 79, 701–721. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.79.5.701

Greenberg, J., Pyszczynski, T., and Solomon, S. (1986). “The causes and consequences of a need for self-esteem: a terror management theory,” in Public Self and Private Self, ed R. F. Baumeister (New York, NY: Springer), 189–212. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4613-9564-5_10

Hofer, M. (2013). Appreciation and enjoyment of meaningful entertainment: the role of mortality salience and search for meaning in life. J. Media Psychol. 25, 109–117. doi: 10.1027/1864-1105/a000089

Janicke-Bowles, S. H., and Oliver, M. B. (2017). The relationship between elevation, connectedness, and compassionate love in meaningful films. Psychol. Popul. Media Cult. 6, 274–289. doi: 10.1037/ppm0000105

Janicke-Bowles, S. H., and Ramasubramanian, S. (2017). Spiritual media experiences, trait transcendence, and enjoyment of popular films. J. Media Relig. 16, 51–66. doi: 10.1080/15348423.2017.1311122

Janicke-Bowles, S. H., Raney, A. A., Oliver, M. B., Dale, K. R., Jones, R. P., and Cox, D. (2021). Exploring the spirit in US audiences: the role of the virtue of transcendence in inspiring media consumption. J. Mass Commun. Q. 98, 428–450. doi: 10.1177/1077699019894927

Johnson, B. K., Slater, M. D., Silver, N. A., and Ewoldsen, D. R. (2016). Entertainment and expanding boundaries of the self: relief from the constraints of the everyday. J. Commun. 66, 386–408. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12228

Jonason, P. K., and Webster, G. D. (2010). The dirty dozen: a concise measure of the dark triad. Psychol. Assess. 22, 420–432. doi: 10.1037/a0019265

Kelly, E. W. Jr. (1995). Spirituality and Religion in Counseling and Psychotherapy. Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association.

Lichtenthal, W. G., Cruess, D. G., and Prigerson, H. G. (2004). A case for establishing complicated grief as a distinct mental disorder in DSM-V. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 24, 637–662. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.07.002

Maciejewski, P. K., Zhang, B., Block, S. D., and Prigerson, H. G. (2007). An empirical examination of the stage theory of grief. JAMA 297, 716–723. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.7.716

Mar, R. A., and Oatley, K. (2008). The function of fiction is the abstraction and simulation of social experience. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 3, 173–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00073.x

Mar, R. A., Oatley, K., Hirsh, J., Dela Paz, J., and Peterson, J. B. (2006). Bookworms versus nerds: Exposure to fiction versus non-fiction, divergent associations with social ability, and the simulation of fictional social worlds. J. Res. Pers. 40, 694–712. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2005.08.002

Menninghaus, W., Wagner, V., Hanich, J., Wassiliwizky, E., Jacobsen, T., and Koelsch, S. (2017). The distancing-embracing model of the enjoyment of negative emotions in art reception. Behav. Brain Sci. 40, 1–63. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X17000309

Merz, E. L., Malcarne, V. L., Hansdottir, I., Furst, D. E., Clements, P. J., and Weisman, M. H. (2009). A longitudinal analysis of humor coping and quality of life in systemic sclerosis. Psychol. Health Med. 14, 553–566. doi: 10.1080/13548500903111798

Morgan, J., Smith, R., and Singh, A. (2019). Exploring the role of humor in the management of existential anxiety. Humor 32, 433–448. doi: 10.1515/humor-2017-0063

Nabi, R. L. (2015). Emotional flow in persuasive health messages. Health Commun. 30, 114–124. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2014.974129

Nabi, R. L., and Green, M. C. (2015). The role of a narrative's emotional flow in promoting persuasive outcomes. Media Psychol. 18, 137–162. doi: 10.1080/15213269.2014.912585

Neimeyer, R. A., and Currier, J. M. (2009). Grief therapy: evidence of efficacy and emerging directions. Curr. Direct. Psychol. Sci. 18, 352–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01666.x

Oliver, M. B., Ash, E., Woolley, J. K., Shade, D. D., and Kim, K. (2014). Entertainment we watch and entertainment we appreciate: patterns of motion picture consumption and acclaim over three decades. Mass Commun. Soc. 17, 853–873. doi: 10.1080/15205436.2013.872277

Oliver, M. B., and Bartsch, A. (2010). Appreciation as audience response: exploring entertainment gratifications beyond hedonism. Hum. Commun. Res. 36, 53–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2958.2009.01368.x

Oliver, M. B., Raney, A. A., Slater, M. D., Appel, M., Hartmann, T., Bartsch, A., et al. (2018). Self-transcendent media experiences: taking meaningful media to a higher level. J. Commun. 68, 380–389, doi: 10.1093/joc/jqx020

Ott, C. H. (2003). The impact of complicated grief on mental and physical health at various points in the bereavement process. Death Stud. 27, 249–272. doi: 10.1080/07481180302887

Paulhus, D. L., and Jones, D. N. (2015). “Measures of dark personalities,” in Measures of Personality and Social Psychological Constructs, eds G. J. Boyle, D. H. Saklofske, and G. Matthews (London: Academic Press), 562–594. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-386915-9.00020-6

Prigerson, H. G., and Maciejewski, P. K. (2008). Grief and acceptance as opposite sides of the same coin: setting a research agenda to study peaceful acceptance of loss. Br. J. Psychiatry 193, 435–437. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.053157

Prigerson, H. G., Vanderwerker, L. C., and Maciejewski, P. K. (2008). “Prolonged grief disorder: a case for inclusion in DSM–V,” in Handbook of Bereavement Research and Practice: Advances in Theory and Intervention, eds M. S. Stroebe, R. O. Hansson, H. Schut, and W. Stroebe (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Press), 165–186. doi: 10.1037/14498-008

Pyszczynski, T., Greenberg, J., and Solomon, S. (1997). Why do we need what we need? A terror management perspective on the roots of human social motivation. Psychol. Inq. 8, 1–20. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli0801_1

Rieger, D., Frischlich, L., Högden, F., Kauf, R., Schramm, K., and Tappe, E. (2015). Appreciation in the face of death: meaningful films buffer against death-related anxiety. J. Commun. 65, 351–372. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12152

Rieger, D., and Hofer, M. (2017). How movies can ease the fear of death: the survival or death of the protagonists in meaningful movies. Mass Commun. Soc. 20, 710–733. doi: 10.1080/15205436.2017.1300666

See, Y. H. M., and Petty, R. E. (2006). Effects of mortality salience on evaluation of ingroup and outgroup sources: the impact of pro-versus counterattitudinal positions. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 32, 405–416. doi: 10.1177/0146167205282737

Sestir, M., and Green, M. C. (2010). You are who you watch: identification and transportation effects on temporary self-concept. Soc. Influen. 5, 272–288. doi: 10.1080/15534510.2010.490672

Skurka, C., Eng, N., and Oliver, M. B. (2022). On the effects and boundaries of awe and humor appeals for pro-environmental engagement. Int. J. Commun. 16:21.

Slater, M. D., Johnson, B. K., Cohen, J., Comello, M. L. G., and Ewoldsen, D. R. (2014). Temporarily expanding the boundaries of the self: motivations for entering the story world and implications for narrative effects. J. Commun. 64, 439–455. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12100

Slater, M. D., Oliver, M. B., Appel, M., Tchernev, J. M., and Silver, N. A. (2018). Mediated wisdom of experience revisited: delay discounting, acceptance of death, and closeness to future self. Hum. Commun. Res. 44, 80–101. doi: 10.1093/hcr/hqx004

Vorderer, P., Klimmt, C., and Ritterfeld, U. (2004). Enjoyment: at the heart of media entertainment. Commun. Theory 14, 388–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2004.tb00321.x

Keywords: narrative, humor, poignancy, death acceptance, grief/loss, enjoyment, appreciation

Citation: Fitzgerald K, Francemone CJ and Grizzard M (2022) Humor and poignancy: Exploring narrative pathways to face death and bereavement. Front. Commun. 7:973239. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2022.973239

Received: 19 June 2022; Accepted: 20 September 2022;

Published: 11 October 2022.

Edited by:

Anja Kalch, University of Augsburg, GermanyReviewed by:

Anna Wagner, Bielefeld University, GermanyConstanze Küchler, University of Augsburg, Germany

Copyright © 2022 Fitzgerald, Francemone and Grizzard. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kaitlin Fitzgerald, a2F0aWUuZml0emdlcmFsZEBrdWxldXZlbi5iZQ==

†ORCID: Kaitlin Fitzgerald orcid.org/0000-0002-4491-1768

C. Joseph Francemone orcid.org/0000-0003-3075-4412

Matthew Grizzard orcid.org/0000-0003-2883-0308

Kaitlin Fitzgerald

Kaitlin Fitzgerald C. Joseph Francemone

C. Joseph Francemone Matthew Grizzard

Matthew Grizzard