- 1Department of Basic Sciences, Applied College, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- 2College of Languages and English Language Institute, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- 3Department of Linguistics and English Language, Lancaster University, Lancaster, United Kingdom

In this study, we assess the applicability and usefulness of a particular theoretical framework for qualitative analysis of communicative strategies in discourses from beyond the English language. The theory in question is Cialdini's model of persuasion (and the related concept of pre-suasion). We present an operationalisation of this framework in terms of concrete linguistic features, which is implemented using the computer-assisted methods of corpus linguistics. As a case study, we explore a particular type of Arabic-language online public discourse surrounding an issue of pressing contemporary concern, namely the COVID-19 Pandemic. Specifically, we use a large collection of texts produced by the Ministry of Health of Saudi Arabia via the medium of the Ministry's official Twitter account. The tweets in question were produced in the context of a campaign to persuade the public to modify their behavior to comply with policies on protective measures. While the use of corpus-assisted linguistic approaches to examine public discourses around socially or culturally prominent issues is well-developed in the Anglosphere, it remains much more rarely utilized in the Arab World context, and especially in application to discourses in the Arabic language itself. In addition to the contribution arising from the improvements generated in our understanding of the particular issue at hand, this paper aims to contribute to the broader field of Arabic linguistics by modeling a suitable approach—albeit one whose use we show to be subject to some complicating factors—to address other questions in the study of persuasive language in Arabic.

Introduction and background

COVID-191 is an infectious disease caused by a newly discovered coronavirus. While most of those infected experience symptoms similar to normal flu, older people, and those with underlying medical problems such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic respiratory disease, and cancer are more likely to become seriously ill and need to be hospitalized, potentially in intensive care units. The novel coronavirus emerged in the city of Wuhan, China, in December 2019. The World Health Organization (WHO) declared the coronavirus outbreak a pandemic2 on 11 March 2020. At the time of writing, the world had experienced in excess of 170 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 and 3.5 million confirmed deaths.

In early 2020, governments across the world implemented many measures to attempt to slow down the spread of the coronavirus. These included halts to international travel; locking down cities, regions, or entire countries; and urging people to stay at home3 From 16 March 2020, the government of Saudi Arabia closed all schools and universities; suspended operations of many markets and malls; prohibited outdoor gatherings; closed restaurants except for take-away services; closed stores except for pharmacies and grocery stores; imposed a nationwide curfew; and suspended international and domestic transportation.

Prior to the introduction of vaccines4 in the winter of 2020/2021, such measures were the only way to mitigate the pandemic. From early in the crisis, the WHO recommended that governments should inform people about the virus, the disease it causes and how to protect themselves from infection5 In Saudi Arabia, the public body responsible is the Ministry of Health (MoH). Among other means, the MoH uses its official Twitter account to communicate information on the best practices for avoiding coronavirus infection.

In this paper, we take the use of Twitter during the pandemic by the Saudi MoH as a case study with which to explore the use within non-English corpus-based discourse-pragmatics of a cross-disciplinary model of persuasive language, that of Robert Cialdini. In doing so, we have two goals, one practical and one theoretical. In practical terms, Cialdini's model, though popular, has been expounded almost exclusively with English texts. We wished to see whether it would prove a workable model of persuasive communication in the Arabic language—and, specifically, in the context of a novel crisis (COVID-19) and a comparatively novel medium (social media6, specifically Twitter7). Theoretically, we wished to identify any limits of the applicability of Cialdini's non-linguistic approach within an explicitly linguistic investigation.

In the context of public health ‘social media has the potential to improve the way public health agencies engage, interact and communicate with its various audiences” (Thackeray et al., 2012). Social media not only disseminate health related information but can also be used to engage users, which is likely to maximize the benefit of social media (Neiger et al., 2013). In a discussion of social media in emergency scenarios, Crowe notes that “social media systems are not going away and neither are disasters, therefore, it is paramount for emergency managers and the profession as a whole to find ways to understand and embrace how social media are impacting their lives and communities” (Crowe, 2011, p. 418). Crowe also observes that “[s]ocial media also create an inherently higher trust factor for information because of the shared network of friends, contacts and organizations” (Crowe, 2011, p. 410). Social media has the “potential to enhance existing and foster new cultures of openness” (Bertot et al., 2010, p. 267). Citing evidence from Starbird and Palen (2010) showing that “Twitter users overwhelmingly retweet messages from official information sources such as emergency management or news media organizations,” Latonero and Shklovsky conclude that “[s]ource credibility is essential during crisis communications” (Latonero and Shklovski, 2011, p. 9).

Currently, in Saudi Arabia, most ministries and governmental organizations have official Twitter accounts, which are used not only for broadcast announcements but also interactively, e.g., to respond to queries from the public. The role of social media is not to be neglected as the percentage of Twitter users in Saudi Arabia is among the highest in the world (Algaissi et al., 2020, p. 836). Saudi Arabia, as of January 2021, is ranked 8th among countries in terms of its number of Twitter users8.

During the Coronavirus crisis, the Saudi MoH has used their official Twitter account to run awareness campaigns to get the public informed about the situation.9 The main aim of these campaigns is to motivate the public to follow WHO guidelines for infection control and to abide by other safety measures introduced by the government. Other media exploited for this awareness campaign include nationwide mobile text messages, as well as the more usual print and broadcast mass media.

This course of action by the Saudi MoH illustrates a particular pattern. In situations of risk, most governments (depending on the specific laws and type of polity) have authority to take countermeasures and to implement institutional safeguards, steps which can have an impact upon millions of lives, in order to protect their people. These measures may necessitate the promulgation of new rules or recommendations to the public, restricting or requiring particular behaviors so as to mitigate the risk situation. Public appreciation of the need to abide by such restrictions or requirements is typically then also needed to avoid or at least reduce the need for direct enforcement. To achieve this, the ruling body in question must inform the public of the situation, in particular, the gravity of the risk.

The role of the media in risk communication has been tackled in many studies (e.g., Krimsky and Golding, 1992; Quigley, 2008; Friedman and Egolf, 2011; George, 2012). Most such research deals with traditional mass media, i.e., television and newspapers. The growth of social media since circa 2005, along with increasing global penetration of the prerequisite technology to participate in it, has furnished organizations with a powerful new tool for risk communication. Social media can be considered “an important arsenal in crisis communication” which has deservedly “become a vital part of some organizations' crisis management policy” (George, 2012, p. 33).

The Saudi MoH uses its official Twitter account to communicate with the public with updates about the transmission of the virus, the numbers of confirmed cases, deaths and recoveries, the measures taken by the government to overcome the crisis, and advice and instructions on best protection practices. The MoH is credible as a source of information due to being the official health authority in Saudi Arabia. This credibility is evidenced in the increase in the number of followers of the MoH Twitter account from 1.2 million followers in February 2020 to 4.9 million in June 2021 (according to the numbers observable on Twitter on those dates).

A number of studies dealt with Arabic tweets during the COVID-19 crisis. Alqurashi et al. (2020) collected and described a dataset of Arabic tweets on COVID-19 aiming to help researchers and policy makers in studying different societal issues related to the pandemic including information sharing, misinformation and rumors spreading. Mubarak and Hassan (2021) presented the largest manually annotated dataset of Arabic tweets related to COVID-19 from all the Arab regions. They described the annotation guidelines, analyzed the dataset and built effective machine learning and transformer-based models for classification. Some studies were interested in analyzing people's emotions during the crisis. Bahja et al. (2020) used (NLP) techniques to identify COVID tweets and demonstrate the initial results of determining the relevancy of the tweets and what Arabic speaking people were tweeting about the three disease related feelings/emotions about COVID: Safety, Worry, and Irony. Alhazmi and Alharbi (2020) investigated the public's emotional responses associated with the pandemic as reflected in the Saudis' tweets during the lockdown. Al-Shargabi and Selmi (2021) explored the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on Saudi users' tweeting behavior, adopting a social network analysis (SNA) for COVID-19 Arabic tweets. Alhumoud (2020) analyzed the influence of COVID-19 using machine learning and deep learning methods to quantify the sentiments shared publicly on Twitter and assessed their correlation with the actual number of cases reported over time. Alhassan and AlDossary (2021) have used the Crisis and Emergency Risk Communication model to explore the MOH's use of Twitter and the public's engagement during different stages of the COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia. They identified message types, including risk messages, warnings, preparations, uncertainty reduction, efficacy, reassurance, and digital health responses, and assessed the effect of these message types on public engagement. Our paper focuses mainly on communication strategies relevant to persuasion, or, more particularly, the persuasion principles that MoH depended on to reach people and persuade them toward the desired changes in behavior.

Cialdini's framework of pre-suasion and persuasion

There are several behavior change theories in the literature (see Michie et al., 2014 and Pinder et al., 2018 for an overview). In this era, utilizing digital technology to “foster or support behavior change” is quite common (Michie et al., 2017). This tendency is known as digital behavior interventions and is manifest in a wide variety of domains, such as encouraging physical activity (Nguyen and Masthoff, 2010), healthy eating (Grasso et al., 2000; Mazzotta et al., 2007), healthy weight management (Purpura et al., 2011), skin self-examinations by cancer patients (Smith et al., 2016), and so on. One of the techniques used to effect behavior change is persuasive messages (Kaptein et al., 2010).

Our research is guided by the theory of the psychologist Cialdini (2016). This has been widely implemented in studies such as Orji (2016) on differences and similarities in perceived persuasiveness between different cultural communities; Orji et al. (2015), Oyibo et al. (2017), Thomas et al. (2017), Oyibo and Vassileva (2019), and Wall et al. (2019) on the effect of age, gender, and personality traits on persuasive strategies; Smith et al. (2016) on persuasive reminders for skin cancer patients; and Siegel et al. (2017) on persuasive interventions to encourage help-seeking among people with depression.

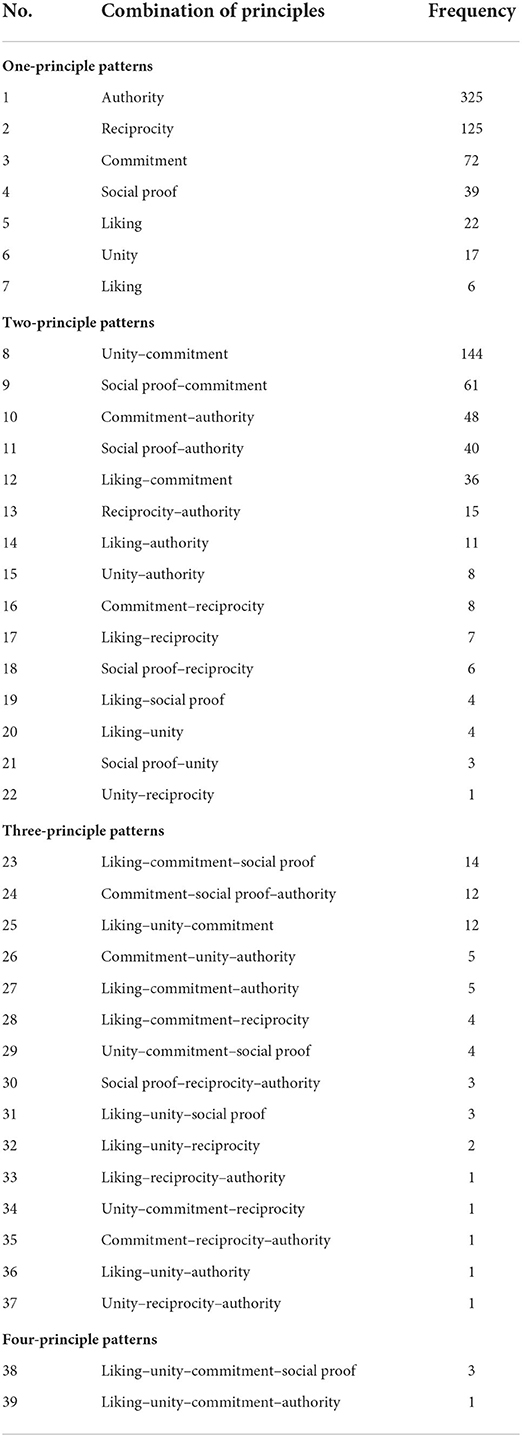

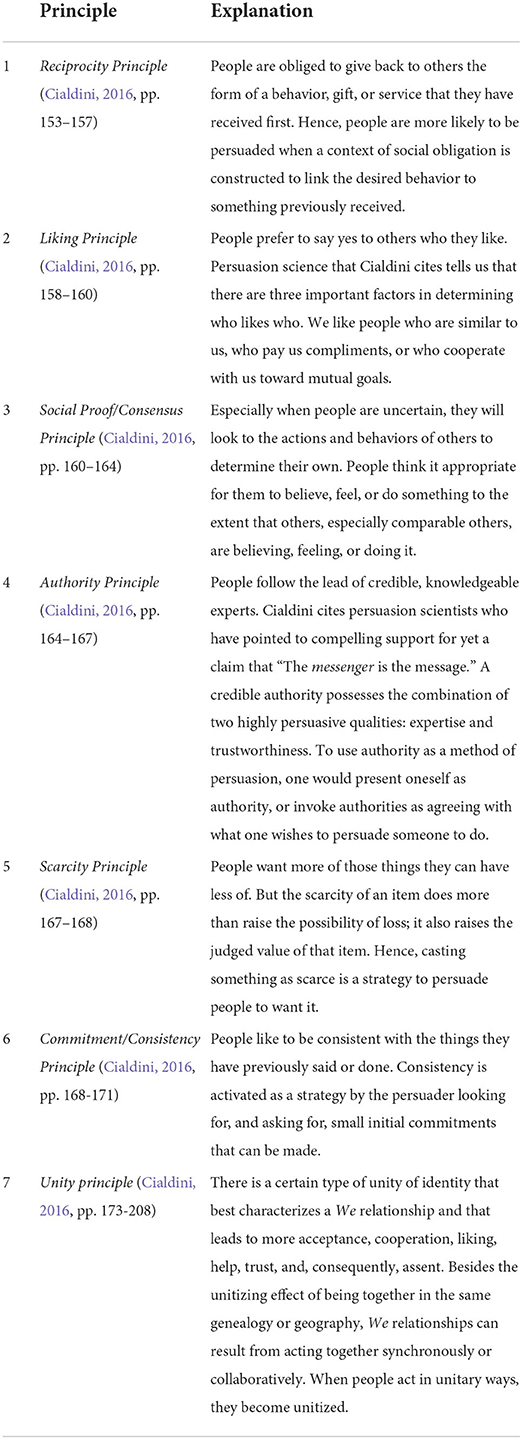

Cialdini (2009) proposed six persuasive principles that guide human behavior which he labeled “Universal Principles of Influence.” These principles—Reciprocity, Liking, Social Proof, Commitment, Authority, and Scarcity—are techniques that can be employed to motivate behavior and/or attitude change. Later, Cialdini (2016) added a seventh principle, Unity. Cialdini claimed that “[t]here is good reason for their prevalence and success, for these are the principles that typically steer people in the right direction when they are deciding what to do” (Cialdini, 2016, p. 17); and that “[t]hese principles are highly effective general generators of acceptance because they typically counsel people correctly regarding when to say yes to influence attempts” (Cialdini, 2016, p. 152). The principles are described briefly in Table 1.

Table 1. Cialdini's Principles of Influence (adapted from Cialdini, 2016, pp. 152–208).

According to Cialdini, persuasion is more likely to occur optimally if it is accompanied by pre-suasion, i.e., the process of preparing recipients to be receptive to a message before they encounter it, or more informally, of grabbing their attention. Persuaders should use a number of strategies, commonly referred to by behavioral scientists as frames, anchors, primes, mindsets or first impressions (Cialdini, 2016, p. 8). Cialdini calls them openers,

because they open up things for influence in two ways. In the first, they simply initiate the process; they provide the starting points, the beginnings of persuasive appeals. But it is in their second function that they clear the way to persuasion, by removing existing barriers. In that role, they promote the openings of minds … (Cialdini, 2016, p.8).

Successful openers pre-suasively channel recipients' attention only to those concepts that are associated favorably with the communicator's particular goal (Cialdini, 2016, p. 152).

Pre-suasion tactics have the purpose of making people more receptive to a message, request, or proposal before it is even delivered to them. These tactics depend mainly on mastering attention, evoking unity and fostering mental connections. Attention is central to pre-suasion. When we pay attention to something, it automatically becomes important to us. Moreover, attention is limited, as definitionally a person can pay attention to only one thing at a time. To persuade anyone of anything, it is necessary to capture, hold and direct their attention. Cialdini (2016, pp. 31–96) proposes four tactics for control of attention, although the criticism may fairly be made that the four overlap very extensively and are by no means clearly distinct. The first tactic is changing the direction of someone's attention. By having their attention shifted to a certain issue, the way people view this issue also shifts. The second tactic is asking targeted questions, i.e., questions asked directly to the addressee on the topic needed to be in the center of attention. The third tactic is grabbing attention through using topics that, by their nature, are more likely to get through to a potential addressee. Attention grabbers include sex, danger and novelty. The fourth tactic is holding people's attention, by means of focusing the communication specifically on the addressee(s), crafting it to speak directly to them, talking about their characteristics, and, hence, personalizing them. All these tactics will make people pay attention.

The next facet of pre-suasion, evoking unity (Cialdini, 2016, pp. 172–208), involves a communicator evoking in their addressee(s) the feeling of being a part of something bigger than themselves. This could be a shared group, a shared identity, or even a shared world view. Evoking unity thus might typically involve language intended to make addressees focus on their belonging to some relevant group. It is notable that Cialdini's model repeats the concept of unity within the discussion of pre-suasion, having already included it as the seventh principle of influence, or, in other words, as a persuasion strategy.

The final part of pre-suasion is fostering mental connections (Cialdini, 2016, pp. 97–115), that is, engineering in the addressee novel or reworked mental associations between concepts in such a way as to facilitate the desired change in the addressee's stance toward one or more of those concepts. Straightforward examples of this emerge from advertising, among the primary aims of which is to create associations between a product and other (presumably positive) concepts so as to facilitate an addressee becoming more favorable toward the prospect of buying that product. Connections can be subtly formed via specific words, images, or music.

Cialdini emphasizes the need for using by public health communicators to use persuasive language:

What's the persuasive alchemy that allows a communicator to trouble recipients deeply about the negative outcomes of their bad habits without pushing them to deny the problem in an attempt to control their now heightened fears? The communicator has only to add to the chilling message clear information about legitimate, available steps the recipients can take to change their health-threatening habits. In this way, the fright can be dealt with not through self-delusional baloney that deters positive action but through genuine change opportunities that mobilize such action. This approach, then, is how public health communicators can best deploy truthful yet frightening facts: by waiting to convey those facts until information about accessible assistance systems—programs, workshops, websites, and help lines—can be incorporated into their communications (Cialdini, 2016, pp. 67–81).

Cialdini also refers to the effect of using persuasive language on recipients in health communication:

In the province of personal health, when recipients get a message that is self-relevant because it has been tailored specifically for them (for example, by referencing the recipient's age, sex, or health history), they are more likely to lend it attention, find it interesting, take it seriously, remember it, and save it for future reference (Cialdini, 2016, pp. 82–96).

Cialdini's comments on the use of pre-suasion and persuasion in health communication or, more generally, medical discourse, illustrate how communication studies should illuminate the discursive practices occurring outside academia and help the people who participate in these discourses. Health communicators, both healthcare workers and lay people, can benefit immensely from persuasion studies. Discursive practices of these kinds of communicators, such as giving and receiving medical advice on parameters of health, treatment, and prevention, can be tailored according to the principles of influence. People's tendency to resist and challenge medical authority and control of their bodies is evident (Mulderrig, 2011). Hence, when healthcare workers learn to communicate using more persuasive discourse, the probability of lay people complying with their advice will eventually increase.

Materials and methods

As previously stated, this study's goal is to explore the Saudi MoH's Twitter-based coronavirus campaign from the perspective of persuasion and persuasiveness. Specifically, we analyze tweets within the framework of Cialdini's (2016) principles of persuasion and pre-suasion, as introduced in Material and methods Section, which we have found highly suitable as a means of addressing a question which we might frame as “In what way(s) are the MoH's tweets persuasive?” We approach the analysis on two fronts: as well as examining the “types” of persuasion, in the terminology of Cialdini's Principles, we also consider the linguistic structures that realize the pre-suasion tactics which make people more susceptible to persuasion.

The data under analysis was collected directly from the MoH Twitter account in the period from mid-March to mid-August 2020. Our data includes 1,323 tweets, 1,176 in Arabic and 147 in English. The English tweets include 58 announcements of the “Highlights of the press conference of the official spokesperson” and 89 English counterparts of some of the Arabic tweets.

Our analysis is divided into two parts, addressing respectively Cialdini's categories of pre-suasion and persuasion. The first part uses corpus annotation and manual analysis to identify the actual linguistic devices used by the MoH to focus public attention on the issue of the pandemic—that is, to achieve pre-suasion. These include particular choices of words, repetition, use of targeted questions, direct address and imperatives; the evoking of unity through use of the first-person plural; and formation of associations through the use of metaphor.

The first two devices (particular choices of words and repetition) are detected through examining the frequency list. We also ran queries to extract verbs and nouns with first- or second-person enclitics or imperative marking, by specifying annotations for morphological properties (using CQPweb; see Hardie, 2012). Finally, metaphors and targeted questions were identified through manual analysis of the whole corpus.

Our consideration of metaphor as a subtle way of forming connections in aid of pre-suasion is motivated by prior work that has identified metaphors in public communication as a strategic rhetorical resource able to convey certain ideologies and thus usable for persuasion (e.g., Charteris-Black, 2005; Semino, 2008; Hart, 2010; Jeffries, 2010). Messages are persuasive when they: (1) relate to something in which the persuadee already believes (anchor) and (2) evoke things that are already known or at least familiar (Charteris-Black, 2004, p. 18). Thus metaphors, which structure abstract or unfamiliar concepts in terms of concrete or familiar ones, can be a powerful tool in achieving persuasion. Looking at metaphor alongside more precise features such as word choice, repetition, and so on allows us to address the issue of linguistic devices for pre-suasion at multiple levels of abstraction.

The second part of the analysis focuses on Cialdini's framework for understanding persuasion. We apply manual coding to the entire dataset to identify instances of Cialdini's seven persuasion principles in use, with additional analysis of the interaction(s) or intersection(s) of different principles within a single tweet. This was not a difficult process, since the principles' definitions lend themselves very well to operationalization in this way. We looked for certain features as evidence for the use of each principle in a tweet, based on the definitions outlined in Material and method Section:

• The Reciprocity Principle is deemed to be operative when the MoH tells people about the benefits they will gain by following the rules and using the MoH's health services (including screening, examination and treatment, provision of clinics, and development of mobile apps). This positions the actions desired of the addressees as an act of returning favors done for them by the MoH (or the Saudi government or country more broadly). The Reciprocity principle is thus identified by detecting references in the tweets to the services in question. These include Tatamman “Be reassured” clinics; Taakkad “Be certain” centers; the Sihhaty “My health” application; the Tabaaud “Distancing” application; the Tawakkalna “We trust” contact-tracing application; the MoH WhatsApp Health 937 around-the-clock response service; the Mawid “Appointment” service; and free Coronavirus tests.

• The Liking Principle is deemed to be operative when a tweet includes a reference to a person's family, friends or loved ones; or a compliment or good wish.

• The Social Proof Principle is deemed to be operative when there is reference to some model person or group framed as having set a good example to follow, by engaging in the behavior(s) which the persuasion aims to elicit.

• The Commitment Principle is deemed to be operative when a tweet refers to obeying instructions or adhering to preventive measures. It is also operative when there are explicit imperatives to the reader to engage in some desired behavior. Examples include keeping a safe distance from others, washing and sanitizing hands, wearing face masks, and committing to precautionary habits.

• The Authority Principle is deemed to be operative in tweets which make reference to advice from healthcare professionals, government-imposed measures, or religious decrees.

• The Unity Principle is deemed to be operative in tweets that refer to belonging to the same group, the need to act as a group, and/or a common nationality. Examples include direct reference to the homeland and the use of plural first-person pronouns in a manner inclusive of the addressee to invoke nationality as a common group identity.

• We observed that the Scarcity Principle is not utilized in the tweets, since the MoH instead stresses the abundance and broad availability of services offered to the public as part of the efforts of the government to eradicate the pandemic.

The criteria outlined above are, of course, inevitably subject to interpretation when applied to genuine texts, and therefore it is to some degree subjective whether or not a particular persuasion principle is active in a particular tweet. However, while some amount of subjectivity does not invalidate a method, if the principles claimed to be active in each example change radically depending on who is making the claims, then the replicability and reliability of any conclusions drawn from such data are, to say the least, in question. To satisfy ourselves of the validity of the criteria for determining the presence of the persuasion principles, we conducted a small-scale inter-rater reliability test. The main rater trained a second rater10 to identify principles according to the criteria above, a process which included discussion of numerous examples. Then, a random sample of 50 tweets was taken from the overall corpus, excluding any discussed during training. The second rater applied the method independently to these 50 tweets. Then, the principles identified by the two raters were compared. Over 50 tweets, the first rater identified 150 instances of some operative principle (in the majority of these tweets, multiple persuasion principles can be observed). The second rater identified 148, all of which were among the 150 found by the first analyst. That is, the two raters agreed on 148 out of 150 analytic judgements, and the two disagreements were omissions rather than differing interpretations. The inter-rater agreement rate is thus 98.7%.11 This is very high, and satisfies us that despite their potential for subjectivity, the criteria outlined above can in fact be applied by analysts with a high degree of consistency. Quantitative and qualitative analysis based on instances of the persuasion principles detected by these criteria may thus be deemed, at least provisionally, methodologically valid.

Results

Pre-suasion tactics

This section presents the analysis of linguistic devices used by the MoH in the three areas of pre-suasion tactics suggested by Cialdini: focusing public attention, invoking unity and forming associations.

Focusing public attention on the pandemic

In this section, we consider what linguistic devices these communications employ to guide, grab and hold people's attention. Cialdini (2016) suggested using linguistic devices such as targeted questions to guide attention, particular word choices and repetition to grab attention, and direct address and imperatives to hold attention. Though he does not provide a detailed description of how these devices are used, he acknowledged that they are key to achieving the function in question. However, we find it difficult to distinguish “grabbing” vs. “holding attention,” particularly in terms of what linguistic devices might be involved. Hence, we decided to deal with the three functions of guiding, grabbing and holding attention jointly.

According to Hyland (2005) it is necessary to pull addressees into the discourse using engagement markers such as reader pronouns (i.e., first person plural and second person pronouns), targeted questions (i.e., questions including reader pronouns) and imperatives.

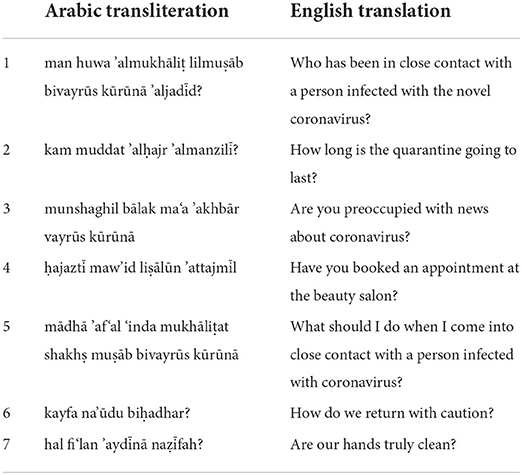

Targeted questions

We manually identified all 136 questions in the data (see examples in Table 2 below). Of these, 56 questions include no pronouns referring to the reader (Examples 1, 2); 69 have second person subjects expressed via enclitics added to nouns (Example 3) or verbs (Example 4); and 6 have a first-person singular subject expressed via enclitics added to verbs (Example 5); and 5 questions include first-person plural subject pronouns, verb agreement or clitic possessive pronouns (Examples 6, 7). In the latter two cases, use of first-person plural frames the scenario as the MoH speaking in the hypothetical “voice” of some individual among the addressees.

These questions demonstrate a tendency for two pre-suasive tactics relating to attention to become blended together, namely, guiding attention and holding attention.

The use of the first person evokes unity with and among the audience. Notably, in questions with singular first-person subjects, the MoH actually speaks in the voice of an assumed reader—expressing the questions that the reader is presumed to be thinking.

Some questions present in the data are left unanswered. Their function may thus be identified as primarily (if not purely) gaining and managing audience attention. Most of the questions, however, are answered in a video or infographic posted in the same or a subsequent tweet; thus, they serve the additional function of guiding addressees” attention to the information in the answer provided.

Repetition

According to Cialdini (2016), attention can be grabbed by repetition of particular wording related to the issue one wants to grab attention for. In this case, we suggest that grabbing attention works in the same way as entrenchment through repeated exposure. People's sustained engagement with protective measures including hygiene and physical distancing is the most critical factor in reducing the transmission of COVID-19 (Bonell et al., 2020). The literature lists a number of cognitive factors which would increase people's engagement with health-protective behaviors during disease outbreaks: the perception of risk or susceptibility to a threat (Petrie et al., 2016), having knowledge about the virus' mode of transmission (Petrie et al., 2016) and having knowledge about ways to reduce the risk of infection (Bish and Michie, 2010). The somewhat repetitive MoH tweets thus can be seen as intended to enhance people's perception of risk from the coronavirus, and to increase through repeated exposure their knowledge of health-protective behaviors, high-risk groups, medication services, virus transmission prevention and so on.

The tweets include particular common wordings related to the pandemic. Exposing people repeatedly to words that connote the pandemic, responsibility and preventive measures increases their awareness of the gravity of the situation and their willingness to follow the protective measures laid down by MoH. Examining the frequency list of the corpus, we extracted all nouns and adjectives whose senses relate to the pandemic. These frequently-repeated words include terms used to name the virus, repercussions, procedures for protection, and so on. Examples include kūrūnā “coronavirus” (frequency of 629), vayrūs “virus” (f.160), 'alwiqāyah “prevention” (f.148), ‘ālāt “cases” (f.146), ta‘āfi “recovery” (f.139), ‘iṣābah “infection” (f.138), ’almuta‘āfiyah “recovered” (f.134), wafiyyāt “deaths” (f.128), ‘alwiqā’yyah “the precautionary” (f.41), ’a‘rāḍ “symptoms” (f.36), ’al‘adwā “infection” (f.33), and so on.

The MoH created a number of hashtags related to the crisis and used them frequently in its tweets. Multiword hashtags are joined up using underscores (Arabic script lacking capitalization, the WordInitialCapitals method used in English-language Twitter is not available). Examples of these hashtags include #wiqāyah “prevention” (f.160), #kullunā_masul “#we_are_all_responsible” (f.146), #na‘ūd_biḥadhar “#we_return_with_caution” (f.106), among others. Terms referring to COVID-19—'alvayrūs “the virus,” 'alwabā' “the epidemic,” and 'aljā'iḥah “the pandemic”—also recur frequently. They can be considered a key element of communication about the crisis. Naming can shape how people perceive things and “how humans communicate with each other and organize their world” (Hough, 2016, p. 1). Indeed, the name given to a disease can shape how people deal with it (Gwyn, 2001). The terms used for COVID-19 emphasize its serious and widespread transmission. In addition to naming, associated words with strong negative connotations, including 'iṣābah “infection,” wafiyyāt “deaths,” ’al‘adwā “infection,” and bimuḍā‘afāt “with complications,” reinforce the effect when repeated.

Other prominent words in the frequency list emphasize (a) government services, e.g., taṭbīq “application,” ‘iyādāt “clinics,” marākiz “centers,” ṣiḥḥatī “my health,” khidmat “service”; (b) precautionary procedures, e.g., 'alwiqāyah “prevention,” 'alkimāmah “face mask,” 'al'ijrā'āt “procedures,” 'alwiqā'yyah “the precautionary,” #mitr_wi_nuṣ “meter_and_a half,” #khallik_bilbayt (colloquial) “#stay_at_home,” naṣā'iḥ “advice”; (c) people's safety, e.g., salāmtak “your safety,” ṣiḥḥatak “your health,” 'āminah “safe,” 'āminin “safe (plural),” #bisalām_'āminin “#peacefully_safe”; (d) the public sense of responsibility and belonging, e.g., 'alwaṭan “the homeland,” #kullunā_masul “#we_are_all_responsible”.

Repeated exposure to these pandemic-related items is intended to grab addressees' attention and lead them to focus on the severity of the situation.

Second-person address and imperatives

Engagement markers, particularly second-person address and imperatives, are used for pre-suasive effect in the tweets, namely holding addressees' attention. Second-person address does not only inform addressees through a text but rather also implicates them in it (Van Leeuwen, 2005, p. 150). Engaging addressees by this means therefore aligns with the MoH's inferred purpose of attracting people's attention and persuading them to adhere to preventive measures.

Identifying second-person address in Arabic is complicated by the fact that independent pronouns are rare; instead, agreement affixes and enclitic pronouns express second-person reference. We therefore used the frequency list to extract verbs and nouns with the appropriate morphology. 35 verbs were found with the second person singular enclitic =k, such as yumkinak “you can” (f.28), and yaḥmīk “protects you” (f.6). 20 verbs were found with the second person plural enclitic =kum, such as yaḥfaẓkum “saves you(pl.)” (f.6), and nad‘ūkum “we call on you(pl.)” (f.4). 10 nouns were identified with second person singular enclitics (with possessive meaning), e.g., baytak “your house,” rizqak “your sustenance,” and ṣiḥḥatak “your health.” Imperative-mood verbs also express a second-person reference and thus may serve the same purpose of engaging addressees and implicating them in the discourse. 29 imperative verbs were found, e.g., taṭamman “be reassured” (f.47), ‘ish “live” (f.42), ta‘arraf “recognize” (f.28), and 'itba‘ “follow” (f.12). In addition, examples of code-switching to English often included verbs used as imperatives. Overall, the high number of second-person references of these various forms strongly suggests that they are being used for attention manipulation and thus pre-suasion.

Unity tactics

Just as second-person address instantiates the tactic of focusing attention, so can first-person plural address function as a tactic to invoke unity. The construction of a We that includes the reader allows the text to present the responsibility to take action as broadly shared across the in-group thus implied. First person plural reference must be identified, just as with the second person, by finding words with particular agreement inflection or object enclitics. Thus, again, we extracted and examined verbs and nouns with first-person inflection or enclitics.

We found 37 verbs with first person plural subject agreement, e.g., Examples include na‘ud [we return] (f.68), nafqid [we lose] (f.3), and naḥriṣ [we be careful] (f.3). Locating verbs with first person plural enclitic pronoun =nā was complicated slightly by the fact that the Arabic word for coronavirus, Kurunā, by happenstance ends in nā. This could cause it to be mistakenly annotated as a verb. Thus, Kurunā had to be manually excluded from the results. This left 15 verbs with the first person plural enclitic, such as tawakkalnā [we trust entirely] (f.3), yuqarribnā [get us close] (f.2), and tuhimmunā [matter to us] (f.2).

The use of the first-person plural, which constructs an in-group, is very useful in crisis communication, to boost people's sense of national unity, belonging and solidarity. Consequently, this should help the government to mobilize people to assist in the crisis management. After all, people's compliance with the protective measures is the key to eradicating the COVID-19 pandemic.

Connection tactics

Finally, pre-suasion is accomplished by forming associations through the use of metaphor. Framing a situation, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, can influence the way people perceive it; the resulting differences in how people construct the situation conceptually have potential consequences for what measures in response will be accepted as appropriate, necessary, and justified. Thus, promulgating metaphors that foster mental connections between the pandemic and the framing that is desired for persuasive purposes is a pre-suasive tactic.

War metaphors are known to have been used in discourse around previous epidemics, such as SARS (Koteyko et al., 2008, p. 247–259; Joye, 2010, p. 594) and avian flu (de la Rosa, 2007, p. 18–26, de la Rosa, 2008, p. 91–94). Hence, to find war metaphors being used in the context of COVID-19 is not surprising: the war metaphors detected are given in Table 3. These metaphors structure the situation as a battle against the virus. Health workers are presented as champions fighting a front-line battle (8). The whole populace is depicted as soldiers facing and resisting an attack by adhering to preventive measures (9, 10), and the country is defending itself, fighting for its health security (10, 11). Preventive measures and awareness constitute a defensive shield (12). These metaphors play an important role in pre-suading the public by establishing connections to a familiar conceptual framing in which the pandemic is cast in terms of another situation requiring drastic action as a national collective, viz. a war. They thus prepare the public to be persuaded to accept new, exceptional measures being enforced to change their lifestyle and hygiene and social behaviors.

Another metaphor frames COVID-19-related matters in terms of space. Getting tested is conceptualized as a journey to check one's safety (13). Safety and social distancing are also highlighted (14, 15). A smartphone application called tabā‘ud “distancing” was promoted by the MoH's tweets. It warns its owner if they get close to a person diagnosed with COVID-19. One interesting point here is that distance is also made non-figurative in this discourse. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the term social distance was most often metaphorical, referring to a lack of personal closeness in the sense of intimacy. But as of March 2020, social distance has come to refer primarily to literal, physical distance−2 m of actual empty space between two people in the physical world.

Two scenarios are created in the metaphors. The war/defense scenario drives people to think of themselves and their country as being under attack; its being linked to the pandemic creates a frame within which the MoH's messages may be less unpalatable, since awareness of and sticking to the rules is the only way (the shield) to protect the country. In this scenario, each action one takes—such as sanitizing or washing one's hands, wearing masks and so on—is part of one's country's defense effort. Other aspects of the scenario include casting healthcare workers as the defending soldiers in charge of the defense effort. The other scenario is designed in terms of space which can be seen as both literal and metaphorical, since we are required both to literally physically distance ourselves and to distance ourselves metaphorically from the virus and its causes of transmission. The use of these scenarios forms certain associations in people's minds and makes it easier to persuade them to follow the precautionary measures suggested either by MoH or the World Health Organization.

The discourse of healthcare workers as heroes/soldiers/defenders of their nations has emerged globally to characterize the collective response of front-line healthcare workers, many of whom compromised their personal safety to care for others. This discourse is performed not only linguistically in official communications such as tweets, but also by the public in the form of singing from balconies, clapping, and other gestures of appreciation directed to healthcare workers across the world. This latter discourse expression is understudied, albeit some studies have acknowledged the positive effects of this discourse on enhancing the visibility of healthcare workers but have also problematised its effects on the healthcare workers' professional, social, and political identities (Einboden, 2020; Morin and Baptiste, 2020; Mohammed et al., 2021).

Persuasion principles in the tweets

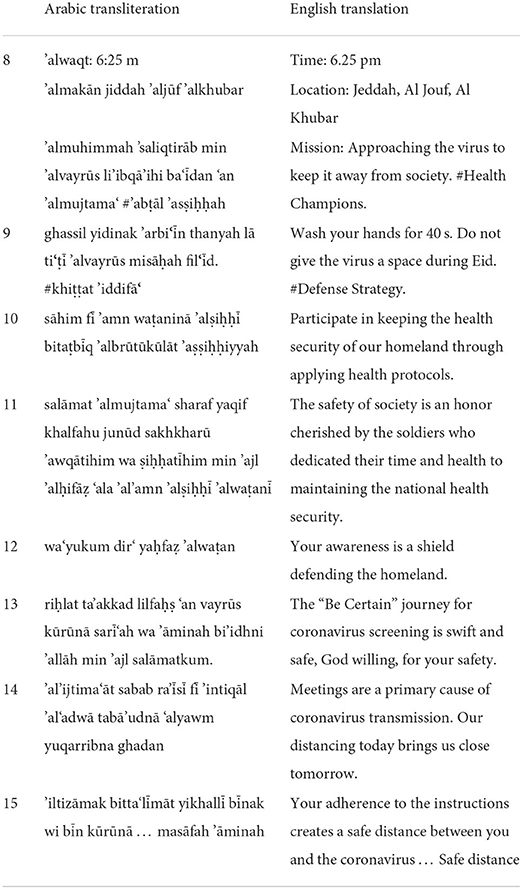

To look at persuasion, we manually identified all observable instances of Cialdini's Persuasion Principles in the tweets; Table 4 presents counts of the instances we found.

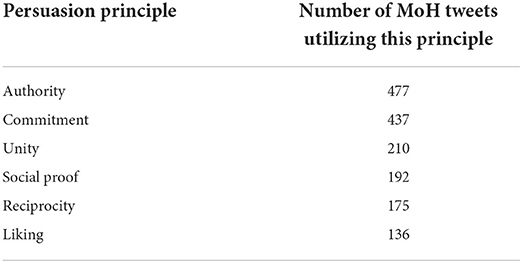

We found that many tweets exemplify more than one principle. In fact we observed the principles in combinations ranging from 2 to 4 in the same tweet. We spotted, in all, 39 distinct patterns of simultaneously operative persuasion principles, listed in Table 5; specific examples of tweets in which different principles, and patterns of their combinations, are observed will now be considered.

Authority

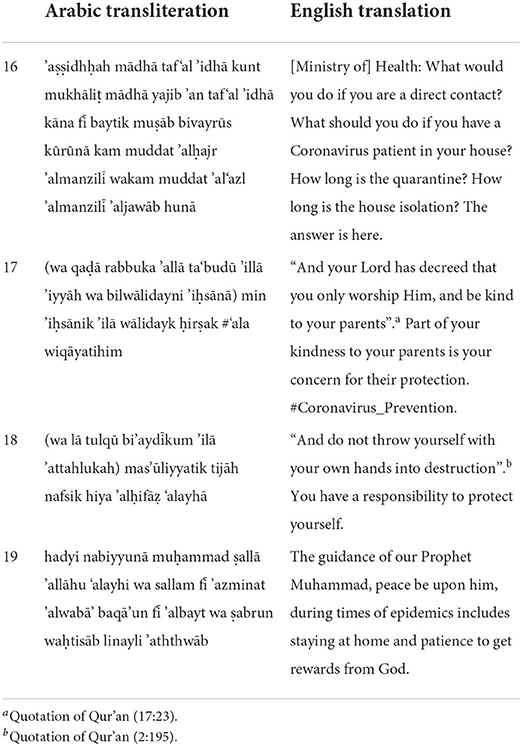

The Authority pattern is exemplified in Table 6. In (32), it is expressed by the explicit mention of the MoH, the highest authority for health services, as the source of information (here, and in some other examples, referred to solely by the noun 'aṣṣiḥḥah “health”)—unnecessarily, since the context of being an MoH tweet implies the source. The reliability of this information is likely to be deemed high by, and thus to be persuasive to, readers, since it comes from the chief governmental health authority. Example (32) shows how the government attempts to ensure public compliance of the through soft power, embodied in the focused MoH campaign which advised people to follow protective measures for their own interest. Example (13), on the other hand, exemplifies the government's expression of their hard power in the warning that people will face legal consequences if they violate protective measures. The principle of authority is clearly employed to persuade here, and the source of the authority is actual governmental power rather than authority in any figurative sense.

The Divine as authority can be seen in Example (16). Here, authority is expressed by the quotation of Allah's decree that one has to be kind to one's parents. In the context of COVID-19, being kind to one's parents can be associated with protecting them against the Coronavirus. Example (17) also asserts divine authority by implicitly equating Allah's ruling against hurting oneself with the pandemic regulations, thus enlisting divine authority in the act of persuasion. Example (18), on the other hand, draws directly on the authoritative guidance of the Prophet Muhammad on what Muslims should do during epidemics; unlike the two examples with Qur'anic quotations, no parallel needs to be implied, as the topic is already defense against contagions. These three examples depend on Islamic belief as the source of the authority that is deployed to persuade people to comply with protective measures. As Islam's place of origin and home to its most scared location, Saudi Arabia is at the spiritual center of the Muslim world. It may safely be posited that religious discourse is highly salient in Saudi, and possibly all Arab, culture. From the start of the pandemic, Muslims have been pleading for Allah to eradicate the virus. These pleas have been echoed in communal prayers led by Imams. This predominant social discourse, rooted in religious practice, is drawn on by the MoH tweets to buttress their persuasive efforts with religious duty.

Reciprocity

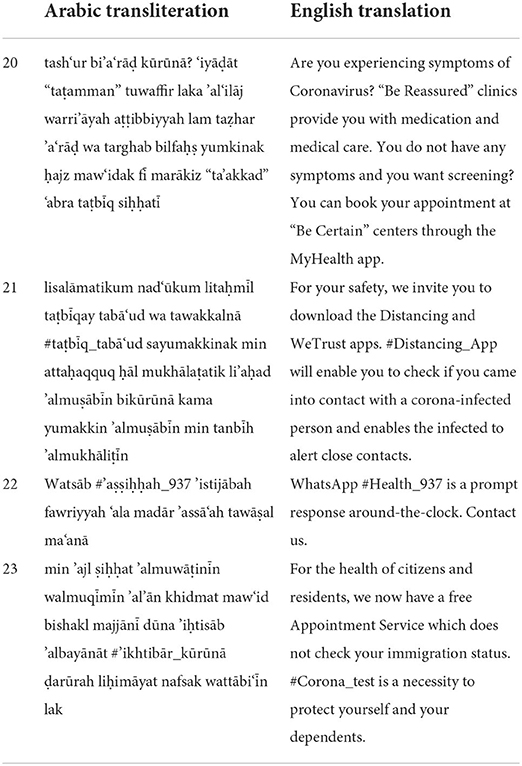

The Reciprocity Principle is detected in tweets referring to services provided by the MoH, with the desired reciprocal action being compliance with the MoH's measures, as illustrated in Table 7.

Examples (20)–(23) list clinics, testing centers, and appointment-booking systems, especially mobile apps. In (23), for example, illegal immigrants are encouraged to engage with health services to avoid getting or spreading COVID-19, and in exchange for them doing the right thing, they are not put at risk of deportation for doing so. Examples (20)–(22) depict a general normative scenario whereby the MoH helps citizens, and they reciprocate by sticking to regulations. Example (23), on the other hand, addresses a particular case whereby immigrants help the MoH by engaging with services, and the MoH reciprocates by not (potentially) deporting them. The Saudi government is aware that the only way to contain the pandemic was to provide health care for everyone living within its borders, even those whose migration status is not legal. particularly because those people might suffer from the socioeconomic consequences of the pandemic and become one of the most-at-risk groups.12

The list of services provided by the MoH has the additional benefit of stressing the effectiveness of public health interventions to curb the transmission of the virus.

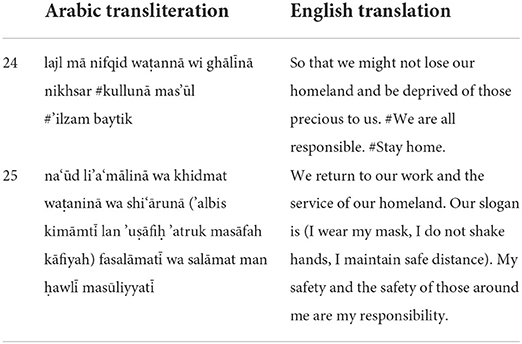

Unity–commitment

Combinations of the principles of Unity and Commitment are identified when there is reference people's obligation to unite to get through the pandemic crisis. Examples (24) and (25), in Table 8, use plural-first person enclitics to foreground the shared identity.

Commitment is evoked here through the concepts of “service,” “responsibility,” and the characterization of the statement of required actions as a “slogan.” The principle of commitment is supported by references to what could be lost if precautionary measures are not followed.

Social proof–commitment

Combinations of the principles of Social proof and Commitment are identified when there is a reference to the pandemic situation, models of people or groups, and their commitment to the protective measures to get through the crisis.

Example (26) in Table 9 refers to a couple celebrating their wedding while complying with preventive measures. The couple are presented as a model and are complemented, since their adherence to protective measures signals their awareness and sense of responsibility. The construction of those who abide by the regulations and safety measures as “model citizens” evokes people's sense of responsibility and duty to obey the public authority. By default, this construction implies that any person who does not appreciate the severity of the pandemic and violates the safety measures would be a bad person.

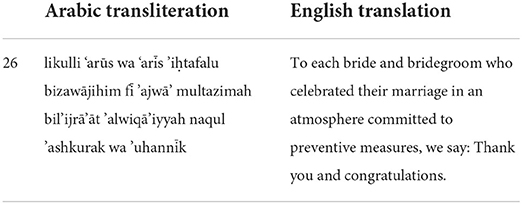

Liking–commitment–social proof

This combination adds to the previous category the principle of liking, evidenced by expressions of MoH's (or the government's in general) care and best wishes.

Example (27) (Table 10 begins by addressing people as “Dear brother, dear sister” to establish a fictive kinship and thereby evoke liking; advises them to commit to the prevention measures; and then, expresses a wish that MoH does not want the addressees and their loved ones to be a part of the statistics of confirmed cases and deaths. Social proof is evoked when there is a reference to a specific group and hence the addressee is invited to identify with them by having the addressee perform certain things and hence become a model for commitment. Example (28) evokes the combination of the three principles in addressing a certain group of people, the elderly, expressing MoH's concern for the health of this group, then advising them to follow the health instructions and apply them to protect themselves against the virus.

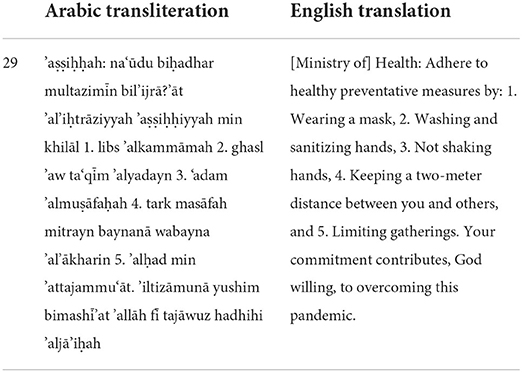

Commitment–social proof–authority

Combinations of the principles of commitment, social proof and authority include references to the pandemic situation, models of people or groups, their commitment to the protective measures to get through the crisis, and a credible source of authority. All four factors are evident in Example (29) in Table 11.

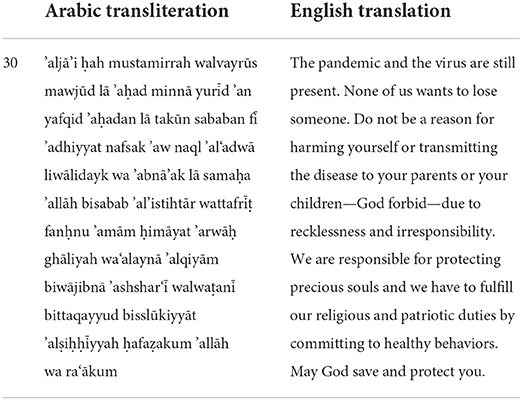

Liking–unity–commitment–social proof

The combination of the principles of liking, unity, commitment and social proof is identified when a tweet includes references to the pandemic situation, model people or groups, people's obligation to unite to get through that crisis, and expressions of care and best wishes for people. Example (30) in Table 12 utilizes both second person (promoting commitment) and first person plural (unity)in the manners already discussed in support of the introduction of these themes. The example reminds people of their responsibility to protect the precious souls of their family and of their national and religious obligation to commit to healthy behaviors (unity, commitment). And finally, it expresses a good wish for the people praying for the addressees to be kept and protected by God (liking). This combination is quite effective in evoking a sense of religious and personal/communal/national responsibility and commitment.

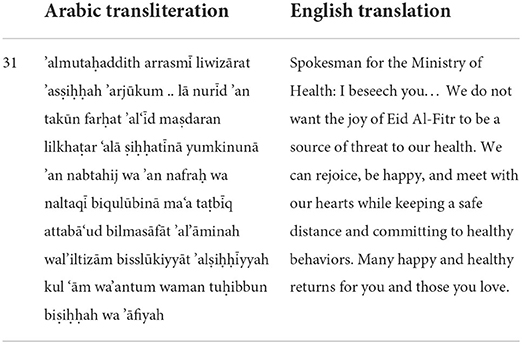

Liking–unity–commitment–authority

The combination of the principles of liking, unity, commitment and authority is identified with references to the pandemic situation, people's obligation to unite to get through that crisis, expressions of care and best wishes for people, and a credible and trustworthy source. Example (31) in Table 13 is a tweet authored by the official MoH spokesperson, addressing people in a caring tone. The tweet starts with a plea. Arabic 'arjūkum “I beseech you” has the same connotation here as English beseech, i.e., of requesting someone to do something that is actually to the requester's own benefit. This generates the impression of a caring tone, which is emphasized by the subsequent first-person plurals establishing unity across the speaker and the addressees.

Discussion

We set out to determine to what extent Cialdini's approach to pre-suasion and persuasion would provide a workable model for analyzing persuasive communication in Arabic, taking the MoH's tweets in the early phases of the COVID-19 crisis as our case study. Cialdini's model of pre-suasion and persuasion offers a framework of categories of analysis that, he claims (Cialdini, 2016), underlie all acts of persuasion, from trying to sell something, to convincing children of something, to public speaking and convincing voters, to all facets of life. This is the first study, to our knowledge, that has focused on applying Cialdini's principles of influence to discourse in Arabic. Having done so, our verdict on the model's workability is somewhat mixed. We are confident that Cialdini's ideas have proved usefully extensible to the Arabic language and, in this specific case, to government-body media posts on Twitter. However, over the course of our analysis, we found that they are to some degree less than satisfactory as a framework for analysis of discourse, in part because of the unfilled gap between high-level principles or tactics and low-level linguistic devices or practices which must concretise those principles or tactics.

While Cialdini himself generally does not propose precise linguistic devices to be expected as realizations of the tactics he discusses, it is generally not difficult to infer some specific linguistic items that should be sought out as examples of his principles or tactics in use. But our implementation of Cialdini's model revealed that the boundaries among the analytic categories of pre-suasion and persuasion are unfortunately porous. Some kinds of tactic are asserted to exemplify multiple areas of the framework (unity). In other cases, e.g., “grabbing” and “holding” attention, aspects of the pre-suasion process are conceptualized as separate in theory but blur together in practice. This considerably problematises the process of identifying linguistic realizations that can be sought out as indicators of a principle in use. Yet other elements of the framework are unsatisfactorily defined so that, depending on how broadly they are interpreted, they might apply to equally to everything in the analysis or be absent from a set of persuasive texts entirely (as is the case, in the MoH tweets, for the principle of scarcity). Any researcher who attempts to utilize Cialdini's conceptual framework at the level of a pragmatic, discourse, or other linguistic analysis, as we have done here, must be aware from the start of the issues of implementation we have highlighted; caveat emptor.

Our study has addressed a type of online public discourse in relation to an issue of pressing contemporary concern. We explored the strategies adopted in the MoH campaign around the coronavirus pandemic to persuade Saudi citizens and residents to abide by the MoH's recommendations for protection against coronavirus. The novel contribution of our research, beyond its assessment of the utility of Cialdini's model for this kind of analysis, is that, while the use of corpus-assisted linguistic approaches to examine public discourses around socially or culturally prominent issues is well-developed in the Anglosphere, it remains much more rarely utilized in non-English-speaking contexts. As well as improving our understanding of the particular issue at hand, then, this study helps the field of Arabic linguistics to move forward in an area where it has presently fallen behind relative to other languages and, particularly, to English.

The MoH's tweets aim to steer how the public should think and behave during the pandemic. They employ both pre-suasive and persuasive strategies to encourage the compliance of the public. We believe that there are possibilities for deliberately deploying the principles of pre-suasion and persuasion to inform healthcare communication, particularly in time of crisis. Thus, in future work, we aim to assist non-academic practitioners in health communication, and to deepen and extend current scholarly understanding of persuasion in general, particularly in novel online contexts. This could provide a resource for practitioners (policymakers, communication specialists) outside academia to better understand persuasive and representational strategies relevant to their areas of concern, and thus enable these practitioners to improve the approaches that they adopt for engagement with the online public sphere. Further studies should also focus on the reception of these principles of pre-suasion and persuasion in order to examine their effectiveness within the context of health crisis management.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: the formal Twitter account of the Saudi Ministry of Health: https://mobile.twitter.com/SaudiMOH.

Author contributions

WI was responsible for data collection, data analysis, the theoretical framework, and writing. HA participated in data collection and data analysis. AH participated in data analysis, the methodology, and writing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, through the Research Funding Program (FRP-1442-2).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^https://www.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus#tab=tab_1

2. ^Remarks by WHO Director-General, archived at https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19-−11-march-2020.

3. ^https://www.bbc.com/news/world-51235105

4. ^It should be noted that by June 1, 2021 Saudi Arabia has administered 14,206,748 vaccine doses, according to MoH Twitter on https://mobile.twitter.com/SaudiMOH.

5. ^https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public

6. ^The effects of social media are twofold. On the positive side, social media can act as invaluable tools for social networking, marketing, and seeking business opportunities. On the negative side, the internet is laden with a number of risks associated with online communities such as, for example, cyber bullying, time wastage, reduction in real human contact. Another negative aspect of social media involves the rise of false emotionalized information which may promote engaging texts over other types. See Siddiqui and Singh (2016) and Akram and Kumar (2017) for a review of the positive and negative effects of social media.

7. ^This study focuses on Twitter because it occupies the third place among the 10 most used social media platforms in Saudi Arabia: WhatsApp 87.40%, Instagram 78.10% and Twitter 71.90%. Also, Twitter is used by all governmental and official institutions in Saudi Arabia to communicate with the public. See https://www.globalmediainsight.com/blog/saudi-arabia-social-media-statistics/ for more information about the Saudi media statistics (last updated 17 June 2022).

8. ^Leading countries based on number of Twitter users as of January 2020. https://www.statista.com/statistics/242606/number-of-active-twitter-users-in-selected-countries/ (accessed June 3, 2021).

9. ^One potentially important question, given Twitter originated in the US but is used worldwide, is the matter of how strategies of persuasion via social media channels, their reception, and their success, may be influenced by international differences in media law and in standard media regulation practices. However, to address this matter in sufficient rigor would be beyond the scope of the present study.

10. ^The first rater, who also applied this analysis to the full dataset, was the first author of this paper. The second rater was the second author of this paper. Both are native speakers of Arabic currently resident in Saudi Arabia.

11. ^This is a direct proportion of shared analyses out of all analyses (148 ÷ 150) and therefore does not account for the probability of agreement by chance alone – as does, for example, Cohen's kappa—since, for this data, that probability is not calculable (because there is no way to know in how many cases some “true” example of a principle was missed by both raters).

12. ^See this article for more information about the migrant health in Saudi Arabia during the COVID-19 pandemic http://www.emro.who.int/emhj-volume-26-2020/volume-26-issue-8/migrant-health-in-saudi-arabia-during-the-covid-19-pandemic.html.

References

Akram, W., and Kumar, R. (2017). A study on positive and negative effects of social media on society. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Eng. 5, 347–354. doi: 10.26438/ijcse/v5i10.351354

Algaissi, A. A., Alharbi, A. K., Hassanain, M., and Hashem, A. M. (2020). Preparedness and response to COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia: building on MERS experience. J. Infect. Public Health 13, 834–838. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.04.016

Alhassan, F. M., and AlDossary, S. A. (2021). The Saudi Ministry of Healths Twitter communication strategies and public engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic: content analysis study. JMIR Public Health Surv. 7:e27942. doi: 10.2196/27942

Alhazmi, H., and Alharbi, M. (2020). Emotion analysis of Arabic Tweets during COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 11, 77. doi: 10.14569/IJACSA.2020.0111077

Alhumoud, S. (2020). Arabic sentiment analysis using deep learning for COVID-19 Twitter data. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Netw. Secur. 20, 132–138. doi: 10.22937/IJCSNS.2020.20.09.16

Alqurashi, S., Alhindi, A., and Alanazi, E. (2020). Large Arabic Twitter dataset on COVID-19. arXiv:2004.04315.

Al-Shargabi, A. A., and Selmi, A. (2021). Social network analysis and visualization of Arabic Tweets during the COVID-19 pandemic. IEEE Access 9, 90616–90630. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3091537

Bahja, M., Hammad, R., Kuhail, M., and Amin. (2020). “Capturing public concerns about coronavirus using Arabic Tweets: an NLP-Driven approach,” in IEEE/ACM 13th International Conference on Utility and Cloud Computing (UCC) (2020), 310–315. doi: 10.1109/UCC48980.2020.00049

Bertot, J. C., Jaeger, P. T., and Grimes, J. M. (2010). Using ICTs to create a culture of transparency: e-government and social media as openness and anti-corruption tools for societies. Govern. Inf. Q. 27, 264–271. doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2010.03.001

Bish, A., and Michie, S. (2010). Demographic and attitudinal determinants of protective behaviours during a pandemic: a review. Br. J. Health Psychol. 15, 797–824. doi: 10.1348/135910710X485826

Bonell, C., Michie, S., Reicher, S., West, R., Bear, L., Yardley, L., et al. (2020). Harnessing behavioural science in public health campaigns to maintain ‘social distancing” in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: key principles. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 74, 617–619.

Charteris-Black, J. (2004). Corpus Approaches to Critical Metaphor Analysis. New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Charteris-Black, J. (2005). Politicians and Rhetoric: The Persuasive Power of Metaphor. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Cialdini, R. B. (2016). Pre-Suasion: A Revolutionary Way to Influence and Persuade. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

Crowe, A. (2011). The social media manifesto: a comprehensive review of the impact of social media on emergency management. J. Bus. Continuity Emerg. Plan. 5, 409–420.

de la Rosa, M. V. M. (2007). A global war against avian influenza. RAEL Rev. Electron. Ling. Apl. 6, 16–30.

de la Rosa, M. V. M. (2008). The persuasive use of rhetorical devices in the reporting of “Avian Flu”. Vigo Int. J. Appl. Linguist. 5, 87–106.

Einboden, R. (2020). SuperNurse? Troubling the hero discourse in COVID times. Health (United Kingdom) 24, 343–347. doi: 10.1177/1363459320934280

Friedman, S. M., and Egolf, B. P. (2011). A longitudinal study of newspaper and wire service coverage of nanotechnology risks. Risk Anal. 31, 1701–1717. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2011.01690.x

George, A. M. (2012). “The phases of crisis communication,” in Case Studies in Crisis Communication, eds George, A. M. and Pratt C. B. (New York: Routledge), 31–50.

Grasso, F., Cawsey, A., and Jones, R. (2000). Dialectical argumentation to solve conflicts in advice giving: a case study in the promotion of healthy nutrition. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 53, 1077–1115. doi: 10.1006/ijhc.2000.0429

Hardie, A. (2012). CQPweb—combining power, flexibility and usability in a corpus analysis tool. Int. J. Corpus Ling. 17, 380–409. doi: 10.1075/ijcl.17.3.04har

Hart, C. (2010). Critical Discourse Analysis and Cognitive Science. New Perspectives on Immigration Discourse. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Hough, C. (2016). “Introduction,” in The Handbook of Names and Naming, ed Hough, C. (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 1–16.

Hyland, K. (2005). Stance and engagement: a model of interaction in academic discourse. Discourse Stud. 7, 173–192. doi: 10.1177/1461445605050365

Joye, S. (2010). News discourses on distant suffering: a critical discourse analysis of the 2003 SARS outbreak. Discourse Soc. 21, 586–601. doi: 10.1177/0957926510373988

Kaptein, M., Lacroix, J., and Saini, P. (2010). “Individual differences in persuadability in the health promotion domain,” in International Conference on Persuasive Technology, Springer, 94–105. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-13226-1_11

Koteyko, N., Brown, B., and Crawford, P. (2008). The dead parrot and the dying swan: the role of metaphor scenarios in UK press coverage of avian flu in the UK in 2005-2006. Metaphor Symbol 23, 242–261. doi: 10.1080/10926480802426787

Krimsky S. and Golding, D. (eds.)., (1992). Social Theories of Risk. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers.

Latonero, M., and Shklovski, I. (2011). Emergency management, Twitter, and Social Media Evangelism. Int. J. Inf. Syst. Crisis Resp. Manag. 3, 1–16. doi: 10.4018/jiscrm.2011100101

Mazzotta, I., de Rosis, F., and Carofiglio, V. (2007). Portia: a user-adapted persuasion system in the healthy-eating domain. Intell. Syst. IEEE 22, 42–51. doi: 10.1109/MIS.2007.115

Michie, S., West, R., Campbell, R., Brown, J., and Gainforth, H. (2014). ABC of Behaviour Change Theories. Sutton: Silverback Publishing.

Michie, S. L., Yardley, R., West, K., and Greaves, P. F. (2017). Developing and evaluating digital interventions to promote behavior change in health and health care: recommendations resulting from an international workshop. J. Med. Internet Res. 19, 7126. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7126

Mohammed, S., Peter, E, Killackey, T., and Maciver, J. (2021). The “nurse as hero” discourse in the COVID-19 pandemic: A poststructural discourse analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 117, 103887. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.103887

Morin, K. H., and Baptiste, D. (2020). Nurses as heroes, warriors and political activists. J. Clin. Nurs. 29, 15353. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15353

Mubarak, H., and Hassan, S. (2021). ArCorona: analyzing Arabic Tweets in the early days of Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. arXiv:2012.01462 [cs.CL].

Mulderrig, J. (2011). Reframing obesity: a critical discourse analysis of the UKs first social marketing campaign. Critic. Policy Stud. 11, 24–40. doi: 10.1080/19460171.2016.1191364

Neiger, B. L., Thackeray, R., Burton, S. H., Thackeray, C. R., and Reese, J. H. (2013). Use of Twitter among local health departments: an analysis of information sharing, engagement, and action. J. Med. Internet Res. 15, e177. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2775

Nguyen, H., and Masthoff, J. (2010). “Mary: A personalised virtual health trainer,” in 18th International Conference on User Modeling, Adaptation, and Personalization, Big Island of Hawaii, HI, USA, June 20–24, 2010, Adjunct Proceedings, pp. 58–60. University of Hawaii.

Orji, R. (2016). “Persuasion and culture: individualism-collectivism and susceptibility to influence strategies,” in PPT@ PERSUASIVE 30–39.

Orji, R., Mandryk, R. L., and Vassileva, J. (2015). “Gender, age, and responsiveness to Cialdinis persuasion strategies,” in Proceedings of rhw International Conference on Persuasive Technology, 147–159. Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-20306-5_14

Oyibo, K., Orji, R., and Vassileva, J. (2017). “Investigation of the influence of personality traits on Cialdinis persuasive strategies,” in PPT@PERSUASIVE.

Oyibo, K., and Vassileva, J. (2019). The relationship between personality traits and susceptibility to social influence. Comput. Human Behav. 98, 174–188. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2019.01.032

Petrie, K., Faasse, K., and Thomas, M. G. (2016). Public perceptions and knowledge of the ebola virus, willingness to vaccinate, and likely behavioral responses to an outbreak. Disaster Med. Public Health Prepar. 10, 674–680. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2016.67

Pinder, C., Vermeulen, J., Cowan, B. R., and Beale, R. (2018). Digital behaviour change interventions to break and form habits. ACM Trans. Comput. Hum. Interact. 25, 3196830. doi: 10.1145/3196830

Purpura, S. V., Schw, K., Williams, W., and Stubler Sengers, P. (2011). “Fit4life: The design of a persuasive technology promoting healthy behavior and ideal weight,” in Proceedings of the International Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, May 7–12, 2011, 423–432. ACM. doi: 10.1145/1978942.1979003

Quigley, K. F. (2008). Responding to Crises in the Modern Infrastructure: Policy Lessons From Y2K. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Siddiqui, S., and Singh, T. (2016). Social media its impact with positive and negative aspects. Int. J. Comput. Appl. Technol. Res. 5, 71–75. doi: 10.7753/IJCATR0502.1006

Siegel, J., Lienemann, B., and Rosenberg, B. (2017). Resistance, reactance, and misinterpretation: Highlighting the challenge of persuading people with depression to seek help. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 11, e12322. doi: 10.1111/spc3.12322

Smith, K. A., Dennis, M., and Masthoff, J. (2016). “Personalizing reminders to personality for melanoma self-checking,” in Proceedings of the 2016 Conference on User Modeling Adaptation and Personalization, 85–93. ACM. doi: 10.1145/2930238.2930254

Starbird, K., and Palen, L. (2010). “Pass it on? Retweeting in mass emergency,” in Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Systems for Crisis Response and Management, Seattle, WA.

Thackeray, R., Neiger, B. L., Smith, A. K., and Van Wagenen, S. B. (2012). Adoption and use of social media among public health departments. BMC Public Health. 12, 1–6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-242

Thomas, R. J., Masthoff, J., and Oren, N. (2017). “Personalising healthy eating messages to age, gender and personality: using Cialdinis principles and framing,” in IUI17 Companion, March 13–16, 2017. Limassol, Cyprus: ACM.

Wall, H. J., Campbell, C. C., Kaye, L. K., Levy, A., and Bhullar, N. (2019). Personality profiles and persuasion: an exploratory study investigating the role of the Big-5, Type D personality and the Dark Triad on susceptibility to persuasion. Pers. Individ. Dif. 139, 69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2018.11.003

Keywords: Arabic discourse studies, pre-suasion, persuasion, coronavirus—COVID-19, Saudi Ministry of Health, Twitter

Citation: Ibrahim WMA, Abaalalaa HS and Hardie A (2022) Pre-suasive and persuasive strategies in the tweets of the Saudi Ministry of Health during the 2020 coronavirus pandemic: A corpus linguistic exploration. Front. Commun. 7:984651. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2022.984651

Received: 05 July 2022; Accepted: 15 August 2022;

Published: 09 September 2022.

Edited by:

Douglas Ashwell, Massey University Business School, New ZealandReviewed by:

Bandar Alhumaidi A. Almutairi, Qassim University, Saudi ArabiaVian Bakir, Bangor University, United Kingdom

Stephanie Liu, The Ohio State University, United States

Copyright © 2022 Ibrahim, Abaalalaa and Hardie. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wesam M. A. Ibrahim, V01JYnJhaGltQHBudS5lZHUuc2E=

Wesam M. A. Ibrahim

Wesam M. A. Ibrahim Hessah S. Abaalalaa

Hessah S. Abaalalaa Andrew Hardie3

Andrew Hardie3