- 1Schreyer Institute for Teaching Excellence, The Pennsylvania State University, State College, Pennsylvania, PA, United States

- 2Instructional Design, STADIO Higher Education, Durbanville, South Africa

- 3Centre for Innovation in Learning and Teaching, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa

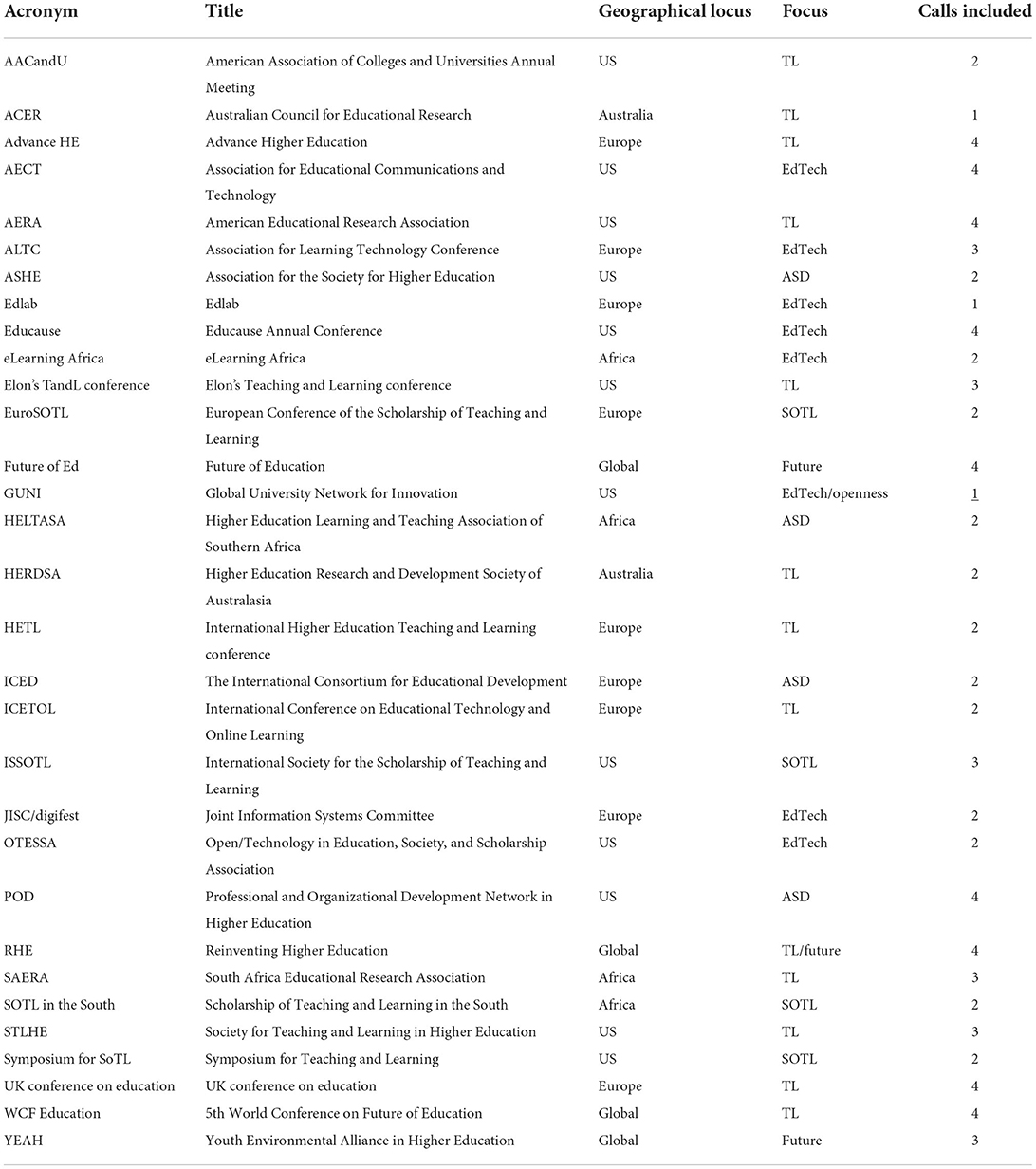

In view of the recent pandemic and growing wicked problems associated with an uncertain, complex and unknown future, this paper explores academics' conceptualizations of the future. Inspired by Kuhn, we chose the academic conference as a public sphere where members of small networks of trusted peers and other such micro-communities gather, creating and recreating the past, present, and future through conversation and collaboration as the site of this paper. We thematically analyzed 83 calls from 39 conferences covering four English speaking regions: North America, Europe, Africa, and Australia/International and five different conference foci, including Teaching and Learning, SOTL, academic staff/faculty development, educational technology and Future Conferences, from 2019 to 2022. Applying thematic analysis, two main themes emerged in relation to the future: responsiveness and temporality. Responsiveness is reflective of the currently dominant neo-liberal paradigm, which seeks to foster incremental adaptations to changing conditions whereas temporality is indicative of more fundamental shifts in thinking. The findings reflect not just what the future may hold, but potentially deeper changes in the relationship between universities and their past, present, and future.

Introduction

In the post-pandemic world, higher education is faced with an increasingly uncertain and super-complex future. These challenges include external pressures, such as globalization, climate change, poverty, racial and ethnic inequities, and internal pressures, such as a decrease in funding, increased competition by private education providers, a move to the recasting of “students as customers” (Mendes et al., 2020), the metrification of knowledge production (Beer, 2016), the growing precarity of academic labor (Megoran and Mason, 2020), and more. It could be said that now, more than ever, universities have to contend with a proliferation of so-called wicked problems, which require the identification and implementation of similarly complex and creative responses.

In a recent essay, Georgetown University Provost Randall (Randy) Bass suggests that one of the biggest wicked problems faced by academia is “reimagining and enacting education so that it plays a meaningful role in creating a more just society and fostering a sustainable human future” (Bass, 2020, p. 10). His call for a professional capacity for imagination comes at a time when that ability is perhaps most endangered. Exacerbated by the recent COVID-19 crisis, the neoliberal academy model has led to an increased sense of alienation among staff (Harley, 2017; Hall, 2018; Mendes et al., 2020), a sense of inevitability of the status quo, “futurelessness,” with decreasing agency or control over “a normalization of crisis” (Fisher, 2009, p. 1). In other words, present circumstances seem to leave little room for dreaming up a better future.

With the intention of bolstering our collective capacity to dream, this paper is interested in exploring where and how academics engage with the notion of their own collective future. We start by analyzing calls for conferences in the context of teaching and learning (T&L), the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SOTL), academic staff development (ASD), educational technologies (EdTech) and future studies across the global English-speaking world (North America, United Kingdom, Australia, and Africa), in the years before, during, and after the profound disruptions caused by the global COVID-19 pandemic.

Literature review

It seems undeniable that the shared experience of the global COVID-19 pandemic has thrown the world for a proverbial loop, leaving a legacy of heightened uncertainty, profound disruption, and generalized anxiety in its wake. Even prior to the pandemic, critics had been persistently taking contemporary academia to task for lacking the ability to adapt nimbly to changing global circumstances like these, often citing the significant weight of historical baggage that seems to weigh down the complex enterprise that is the modern university (Scott, 2006; Marshall, 2010; Connell, 2019). The pandemic has only accelerated the dire rhetoric of crisis, including widespread reporting of Harvard business professor Clayton Christensen's infamous prediction that over half of all U.S. institutions of higher education are likely to close their doors by 2028 if they cannot adapt more rapidly than ever before (Christensen and Eyring, 2011).

Indeed, the weight of the past remains prevalent in academe. Theorists have pointed out that the university is one of the most historically persistent of all organizational types, surviving with its basic medieval characteristics in place for over 500 years longer than any other business corporation (Cruz, 2014). Despite the lingering influence of the past, the work of higher education is fundamentally future-oriented and has been since its inception. What this means is that the academic enterprise has long been pointed toward the future, whether in terms of the creation of new knowledge, the innovative application of that knowledge to evolving circumstances, and/or the inculcation of knowledge and experience into the citizens and employees of tomorrow. The fundamental challenge of future orientation, somewhat ironically, is that the future does not (yet) exist and is, therefore, to varying degrees, unknown, perhaps even unknowable (Barnett, 2012). This suggests an inherent, but perhaps essential, tension between the past, present, and future of academic life and work; a tension that has only been exacerbated by the conditions afforded by the global pandemic.

The invocation of the phrase “essential tension” in the previous statement is an intentional reference to the work of historian of science Thomas Kuhn, who applies the term to the constructive tension between tradition and innovation in scientific research (Kuhn, 1977). For those not familiar with Kuhn's work, his scholarly legacy has served largely to contextualize the creation of knowledge within the social milieu from which it has sprung (Donmoyer, 2006). This means that ideas, and the adaptation of ideas within disciplines, do not occur in a vacuum but rather are constructed and communicated by people who exist within a particular period of time, organizational context, and other related attributes. In other words, the shared experience of the pandemic has shaped us and will continually shape how we reconcile current realities with future possibilities in academia.

Fortunately for Kuhn, he had access to a wealth of tangible artifacts of scientific research, i.e., centuries of (primarily western) academic treatises and manuscripts, which he used as a proxy for/tracer of disciplinary dialogue and debates. In other words, he studied how scientific knowledge had been constructed in the past and then, based on those insights, inferred how those dynamics might apply to the present day. If knowledge was constructed in the past, then it would stand to reason that future knowledge, perhaps even knowledge of the future, would also be constructed. This, in turn, begs the question of when, where, and how those constructions take place, especially when these insights cross over multiple disciplines, a widening proliferation of institutions and institutional types, and an expanding body of stakeholders; all via a shifting array of technology-enabled communication platforms. In this study, we begin to consider the question of how, when, where, and by whom the future of post-pandemic higher education is discussed, debated, and, ultimately, constructed.

Following in Kuhn's footsteps, we may start with conventional sources of knowledge: academic journals and books. Here we find the work of educational philosophers, such as the University of London's Ronald Barnett, who predicted the increasing precarity and insecurity of knowledge, calling not just for responding to possible emerging global challenges, but for more fundamentally revisiting the future-orientation of higher education (Barnett, 2012). Outside of the Global North, philosophical perspectives tend to be increasingly critical, often drawing on the legacy of seminal Brazilian philosopher Paolo Freire (1972, 1994). This latter group not only seeks greater social justice in the world, but also within universities and academic systems, with many calling for the radical de-colonization, i.e., removal of historical baggage, of all facets of academic life and work (Mbembe, 2016; Shahjahan et al., 2022).

While philosophers tend to consider universities globally and abstractly, policy makers look for more tangible representations and outcomes, which are often susceptible to more localized shifts in political perceptions of education as a public good (Marginson, 2011). In their current neo-liberal context, universities are treated primarily as subsidized businesses that must compete for “customers” (students and, at times, faculty) and “resources” (external funding) in order to remain viable, even vital, enterprises (Slaughter and Rhoades, 2000; Davies et al., 2006; Mendes et al., 2020). Indeed, British education scholar Stephen Ball argues that the commodification of all aspects of academic life and work is the hallmark of neo-liberal academia (Ball, 2012, 2015). Remnants of these broader policy-laden conversations can be found in conventional academic outlets, but perhaps the most timely of these debates take place on senate floors, in boardrooms, and within reports generated by consultants and think tanks. These stages are also the domain of the futurist, i.e., professionals trained to predict broad emerging trends that enable strategic enterprises to leverage competitive advantages. Rather than seeking radical change, neo-liberal stakeholders tend to look for forces of stability and frequently champion incremental responses to changing circumstances.

Falling somewhere between the historical ideals of the ivory tower and the data-driven strategies of the neo-liberal boardroom, a third primary arena in which the future of higher education is co-created could perhaps best be represented by the hallway. Arguably, the majority of the members of academe, i.e., faculty and students, largely do not read heady, often somewhat esoteric, works of philosophy nor do they concern themselves with the machinations of high level political debates navigated by the likes of university presidents. On the other hand, an increasing body of research highlights the emergent nature of knowledge of teaching and learning, with an emphasis on micro-communities and small networks of trusted peers as the primary conduits of knowledge, practice, and innovation (Roxå and Mårtensson, 2009; Stark and Smith, 2016).

And scattered evidence suggests that these hallway encounters proliferated and expanded under the conditions of global quarantine, fueled by widespread adoption of technological communication tools, especially web conferencing and social media such as Twitter and WhatsApp (Bolisani et al., 2021; Delgado et al., 2021; Gachago et al., 2021). Despite their rising prevalence, we know relatively little about how these micro-communities function, largely because the conversations that take place are often personal, private, and invisible to others outside of the network. If the future of higher education is being constructed in these elusive arenas, then it seems possible that we may not be able to find out how, except perhaps in the one public sphere where members of these micro-communities converge: the academic conference.

The study

This study aims to explore academics' conceptualization of the future of higher education through the analysis of conference calls. While we acknowledge that conference calls are designed by a small group of conference organizers to elicit interest and possibly shape contributions, and are thus not necessarily representative of all the conversations that academics are engaged in at these conferences, they do capture the “zeitgeist” of certain contexts at very specific moments in time. We analyzed conference calls from 39 conferences (see list of conferences in the Appendix), covering four English speaking regions: North America (US/Canada), Europe, Africa, and Australia/International (grouped under Global) and five different conference foci, including T&L, SOTL, ASD, EdTech and Future conferences, across the years 2019–2022—a total of 83 calls. Of the 39 conferences, four were based in Africa, two in Australia, 13 in Europe, 12 in the US and Canada and four had global reach. Four conferences focused on ASD, nine on EdTech, two on future studies, four on SOTL, and 17 on T&L more generally. Many of the conferences cover more than one focus, so the categorization was not always as clear-cut. Where multiple foci were present, in each case we chose the most prominent focus.

We considered the overall foci of the conferences and analyzed the calls thematically, establishing broad categories of codes in a first round of coding and fine tuning these codes in a second round of coding using MAXQDA. Through coding, two main overarching themes emerged, which we termed Responsiveness and Temporality and which are discussed below. These themes are characterized through a range of codes: transformation and change, diversity, equity and inclusion, sustainability, employability, student learning/voice, and community connection.

Findings

Theme 1: Responsiveness

The first theme that we identified is responsiveness. In the conference calls we found invitations for change, calling for the need “to rethink and reimagine… to regroup and rebuild” (UK Conference on Education: 13). Conceptions about the future are inevitably framed in relation to the recent past, especially the COVID-19 pandemic:

What can we learn from our rich history (recent and long past) of distance and open education as we navigate our way forward (hopefully) beyond the pandemic? (OTESSA: 22–22)

And what of the future, after the pandemic?...Will there be a return to ‘normal', and is that a good thing? And if not, what will the ‘new' normal look like? (SoTL in the South: 10–10)

Acknowledgment of the change and the conditions that prompted such change in the HE context feature prominently across all of the conference types.

A defining characteristic of this theme focuses on incremental strategies for change, often with careful planning and assessment:

Proposals documenting the effectiveness of innovations made necessary by the COVID-19 pandemic are especially welcome, ideally reflecting on the aspects of those innovations that may have value continuing into the future. (Future of Ed: 57–57)

One of the most pressing challenges in today's fast-paced environment is navigating rapid change, an issue which is complicated by culture and climate, change fatigue, and the difficulty of measuring the impact of change…What skills and competencies do we need to successfully navigate change? What tools and frameworks can help us plan for and successfully execute change? (EDUCAUSE: 16–17)

Prominent subjects for incremental change included student learning, employability, sustainability (e.g., “African ideas of community and partnership with nature could soon mean that Africa is increasingly recognized as a resource of knowledge, experience and education for the whole world” (eLearning Africa: 11) and diversity (e.g. “in what ways can we build and extend upon existing research and education with technology to increase ethical, inclusive and diverse policies and practices?”(OTESSA: 9–9)

Theme 2: Temporality

The second theme that we identified is temporality, which is indicative of more fundamental shifts in thinking, not just considering what the future may hold, a perennial question for higher education, but deeper changes in the relationship between universities and their past, present, and future. The term of temporality reflects a more critical and systemic view of change, in which we are not simply preparing for an imagined future, but rather a questioning of the concept of the future as a linear outcome of past and present trajectories.

Under this theme, the pandemic emerges less as a temporary disruption, but rather as a catalyst to change, especially systemic changes related to social justice issues. As Burke and Manathunga (2020, p. 664) point out: “[w]hile the pandemic has certainly exacerbated these pre-existing inequities, in some small ways the challenging of dominant senses of time during this pandemic exposes more of us to how relationships with time are structured differently in relation to class, gender, ethnicity and race, [dis]ability and other key intersectional factors.”

For those calls that were coded from indications of shifts in temporality, time is referenced as flexible, shifting and complex (POD: 19). This fluctuating conception of time demands the need for adaptability and resilience (eLearning Africa: 10), to harness the “positive momentum for … transformation” (JISC/digifest: 23). Change must be “lasting” (JISC/digifest: 23), and therefore nostalgia, a longing for the past (POD: 26–26) and idealizing history should be avoided (ASHE: 33):

Moving backward to how things were before is always tempting because nostalgia and selective memory long for the good ol' times that never actually happened…moving forward, however, is scary even when you know it's the right direction. Forward is full of mystery, risk, failure, and adventure. Forward is the space where we put what we've learned to work – when we reimagine, reconnect, and restart our vision for our communities. (POD: 26 – 26)

Calls under this thematic heading often reflected a collaborative and activist stance, calling on potential contributors to work together toward crafting a future as they wish to see it:

The future that lies ahead for all of us is one that is already being shaped, and education needs to address how it will contribute to the shaping of such a future so that the future is not one that is marked by inequality, gross excesses of power and the unbridled digitalization of our lives and selves. (SAERA: 36–42)

To lead challenging new conversations that can help us understand and shape our changing reality… so that together we can build a future that is more diverse, sustainable, democratic, and just. (OTESSA: 26–26)

This co-created future reflects an essential tension between the local and the global, or “independence and interdependence” (UK Conference on Education). Institutional voices, power, and identities that are culturally situated describe the focus on the local (ICED, AECT). For example, African conferences (eLearning Africa, HELTASA), express the need to create space for southern narratives, the global south, and ubuntu. At the same time, a picture is painted of global engagement and networking, and expanding views beyond institutional and geographical boundaries (SAERA, RHE, HETL). These global orientations highlight the co-mingling of shared experiences, and different perspectives (ALTC).

Discussion and conclusion

Thomas Kuhn's work posited the existence of an academic public sphere, in which scholars engaged in conversations that served not just to disseminate scientific knowledge, but to actively shape and construct it. In this study, we propose that the academic conference as a contemporary locus for a similar academic space, in which the past, present, and future of higher education are created and re-created through conversation and collaboration. This is not a recent occurrence, either, as conferences have served this function for decades, arguably even centuries. It could prove to be an interesting exercise, for example, to resurrect conference calls far older than those used in this study and ascertain the accuracy with which they were able to imagine their future selves.

Our analysis of these more recent calls, however, suggests glimmers of perhaps a more profound shift in the epistemological foundations upon which modern higher education rests, a foreshadowing of potential paradigm shifts in our near future. Our first theme, responsiveness, is reflective of the currently dominant neo-liberal paradigm, which seeks to foster incremental adaptations to changing conditions and rests on the eighteenth-century belief in the inevitable, indeed inexorable, forward march of historical progress. Our second theme, temporality, on the other hand, seeks not just to imagine a different version of our possible future, but rather to lay bare the historical assumptions wrapped up in our very notions of time itself. By positing our relationship to the future as socially constructed, or something over which we can exercise collective agency, we open up possibilities for more profound disruptions, not unlike Kuhn's paradigmatic shifts, which do not occur gradually, but rather in often highly disruptive—and contested—bursts (Gleick, 2008).

Given that we are all presently enveloped in our current paradigm of higher education, it may seem almost impossible to imagine our work life through completely different-colored, even inverted, lenses. This impossibility has two root causes—first, we are constrained from doing so by the current environment, which often engages in strategies focused on self-preservation. In organizational theory, for example, it is well-known that all institutions tend to become more risk-averse over time, seeking increasingly to maintain the status quo into which it has much invested. This is where supra-institutional, liminal spaces, such as those afforded by academic conferences, may provide the necessary breathing space for these conversations to take place. That said, because of the environment of constraint, it is likely that many, if not the majority, of these conversations, take place in proverbial back rooms or stages, and are, therefore, elusive subjects for research. The public-facing conference calls utilized in this study are proxy measures of these discussions at best, but we suggest that they may represent the public-facing tips of larger, invisible icebergs. It could prove to be an interesting line of future research to explore the other liminal spaces that populate academic life and work.

Indeed, a number of scholars have attempted studies of digital backchannels, such as Twitter feeds, now commonplace at many academic conferences (McCarthy and Boyd, 2005; Ross et al., 2011), but these forms of communication are often limited in both length and scope, which may not necessarily provide sufficient space for the kind of contemplation that accompanies more profound meaning making. Under conditions of paradigm shifts, Kuhn argues, the leaders that emerge are most often philosophers rather than scientists or politicians. And our current philosophers of higher education, such as Achille Mbembe and Ronald Barnett, have called upon all of us who work in academia, to not just prepare for an increasingly unknown or uncertain future, but to serve as vital co-creators of our own shared reality and who face the increasingly complex and interdependent challenges of teaching and learning with genuine alacrity, good grace, and creative inspiration.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ball, S. J. (2012). Performativity, commodification and commitment: an I-spy guide to the neoliberal university. Br. J. Educ. Stud. 60, 17–28. doi: 10.1080/00071005.2011.650940

Ball, S. J. (2015). Living the neo-liberal university. Eur. J. Educ. 50, 258–261. doi: 10.1111/ejed.12132

Barnett, R. (2012). Learning for an unknown future. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 31, 65–77. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2012.642841

Bass, R. (2020). What's the problem now? To improve the academy .J. Educ. Dev. 39, 3–29. doi: 10.3998/tia.17063888.0039.102

Bolisani, E., Fedeli, M., Bierema, L., and De Marchi, V. (2021). United we adapt: communities of practice to face the CoronaVirus crisis in higher education. Knowl. Manage. Res. Pract. 19, 454–458. doi: 10.1080/14778238.2020.1851615

Burke, P. J., and Manathunga, C. (2020). The timescapes of teaching in higher education. Teach. High. Educ. 25, 663–668. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2020.1784618

Christensen, C. M., and Eyring, H. J. (2011). The Innovative University: Changing the DNA of Higher Education From the Inside Out. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley and Sons.

Connell, R. (2019). The Good University: What Universities Actually Do And Why It's Time For Radical Change. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Cruz, L. (2014). Opposing forces: institutional theory and second generation SoTL. Int. J. Scholarsh. Teach. Learn. 8. doi: 10.20429/ijsotl.2014.080101

Davies, B., Gottsche, M., and Bansel, P. (2006). The rise and fall of the neo-liberal university. Eur. J. Educ. 41, 305–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3435.2006.00261.x

Delgado, J., Siow, S., de Groot, J., McLane, B., and Hedlin, M. (2021). Towards collective moral resilience: the potential of communities of practice during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. J. Med. Ethics 47, 374–382. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2020-106764

Donmoyer, R. (2006). Take my paradigm… please! The legacy of Kuhn's construct in educational research. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 19, 11–34. doi: 10.1080/09518390500450177

Gachago, D., Cruz, L., Belford, C., Livingston, C., Morkel, J., Patnaik, S., et al. (2021). Third places: cultivating mobile communities of practice in the global south. Int. J. Acad. Dev. 26, 335–346. doi: 10.1080/1360144X.2021.1955363

Hall, R. (2018). On the alienation of academic labour and the possibilities for mass intellectuality. TripleC, 16, 97–113. doi: 10.31269/triplec.v16i1.873

Harley, A. (2017). Alienating academic work. Educ. Change 21, 1–4. doi: 10.17159/1947-9417/2017/3489

Kuhn, T. S. (1977). The Essential Tension: Selected Studies in Scientific Tradition and Change. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. doi: 10.7208/chicago/9780226217239.001.0001

Marginson, S. (2011). Higher education and public good. High. Educ. Q. 65, 411–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2273.2011.00496.x

Marshall, S. (2010). Change, technology and higher education: are universities capable of organisational change? Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 26, 179–192. doi: 10.14742/ajet.1018

Mbembe, A. J. (2016). Decolonizing the university: new directions. Arts Humanit. High. Educ, 15, 29–45. doi: 10.1177/1474022215618513

McCarthy, J. F., and Boyd, D. M. (2005, April). “Digital backchannels in shared physical spaces experiences at an academic conference,” in CHI'05 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Portland), 1641–1644. doi: 10.1145/1056808.1056986

Megoran, N., and Mason, O. (2020). Second-Class Academic Citizens. Available online at: https://www.ucu.org.uk/media/10681/second_class_academic_citizens/pdf/secondclassacademiccitizens (accessed May 04, 2022).

Mendes, J. E., Costa, E. R., Themelis, S., and Gadelha de Carvalho, S. M. (2020). From alienation to solidarity: educational perspectives and possibilities in Brazil and the UK. Beijing Int. Rev. Educ. 2, 571–589. doi: 10.1163/25902539-02040010

Ross, C., Terras, M., Warwick, C., and Welsh, A. (2011). Enabled backchannel: conference Twitter use by digital humanists. J. Doc. 67, 214–237.doi: 10.1108/00220411111109449

Roxå, T., and Mårtensson, K. (2009). Significant conversations and significant networks–exploring the backstage of the teaching arena. Stud. High. Educ. 34, 547–559. doi: 10.1080/03075070802597200

Scott, J. C. (2006). The mission of the university: medieval to postmodern transformations. J. High. Educ. 77, 1–39. doi: 10.1353/jhe.2006.0007

Shahjahan, R. A., Estera, A. L., Surla, K. L., and Edwards, K. T. (2022). “Decolonizing” curriculum and pedagogy: a comparative review across disciplines and global higher education contexts. Rev. Educ. Res. 92, 73–113. doi: 10.3102/00346543211042423

Slaughter, S., and Rhoades, G. (2000). “The neo-liberal university,” in New Labor Forum, (New York: Labor Resource Center, Queens College, City University of New York, NY: Labor Resource Center, Queens College, City University of New York), 73–79.

Stark, A. M., and Smith, G. A. (2016). Communities of practice as agents of future faculty development. J. Fac. Dev. 30, 59–67.

Appendix

Keywords: future orientation, temporality, wicked problems, higher education, conferences, micro communities

Citation: Cruz L, Morkel J and Gachago D (2022) Future tense—Reorienting higher education toward an unknown future. Front. Commun. 7:991698. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2022.991698

Received: 11 July 2022; Accepted: 26 August 2022;

Published: 15 September 2022.

Edited by:

Philippa Rappoport, Smithsonian Office of Educational Technology, United StatesReviewed by:

Elizabeth Root, Oregon State University, United StatesMichelle Epstein Garland, University of South Carolina Upstate, United States

Copyright © 2022 Cruz, Morkel and Gachago. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Laura Cruz, bHhjNjAxQHBzdS5lZHU=

Laura Cruz

Laura Cruz Jolanda Morkel

Jolanda Morkel Daniela Gachago

Daniela Gachago