- 1Center for Teacher Education, Institute of Education, International Graduate Program of Education and Human Development, National Sun Yat-sen University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan

- 2Department of Psychology, University of Texas at Arlington, Arlington, TX, United States

- 3Department of Psychology and Counseling, University of Central Arkansas, Conway, AR, United States

- 4Center for Teacher Education, Cheng Shiu University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan

- 5International Graduate Program of Education and Human Development, National Sun Yat-sen University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan

- 6Communication Science Department, Brawijaya University, Malang, Indonesia

An online survey was used to collect participants' retrospective accounts of an encounter with an “instant enemy” and an encounter with an “instant ally” in samples of 262 American and 250 Taiwanese respondents. Using software that measured the relative use of various word categories, we examined ingroup/outgroup differences and cultural differences in the experience and perception of an “instant enemy” and an “instant ally.” With regard to ingroup/outgroup differences, we found that inclusive and positive emotion words were used more frequently to describe the instant ally encounters, whereas exclusive and negative emotion words were used more frequently in reports of the instant enemy encounters. We also found that our respondents' descriptions of instant ally encounters were more likely to be put into a context defined by words related to leisure, work, and space, whereas their descriptions of instant enemy encounters were more likely to ignore the context and focus instead on what type of person the instant enemy was, as defined by more personal pronouns and words denoting specific categories of humans. With regard to cultural differences, we replicated previous findings indicating that Asian respondents tend to have thoughts and perceptions that are more holistic and integrated than those of Western respondents, as indicated by more words related to cognitive and affective processes, insight, and awareness of causation. Viewed collectively, the findings make a strong case that word-category usage can reveal both well-established and novel findings in comparisons of individuals from different cultures.

Introduction

Two strangers meet on the bus. They begin to talk in an increasingly animated way and, in < 5 min, they are hurling angry insults at each other. Two other strangers meet on the next bus. They begin to talk in an increasingly animated way, and, in < 5 min, they have exchanged smiles and phone numbers and have agreed to get together for lunch.

Although we don't experience these kinds of incidents every day, each of us can probably remember an occasion when, without any advance notice, we suddenly found ourselves in the presence of an “instant enemy” or an “instant ally.” Although encountering “instant enemies” or “instant allies” seems to be an occasional fact of most people's lives, these incidents have not yet become the focus of social science research. Our goal in the present study, therefore, was to begin to address these intriguing phenomena. In this study, we used an online survey method to collect participants' retrospective accounts of an encounter with an “instant enemy” and with an “instant ally,” and to analyze features of words that they wrote to describe their “instant enemy” and “instant ally” experiences.

Many previous studies have reported cultural differences in people's behaviors, communication styles, and facial expressions of emotions (Kitayama et al., 2000; Schroder et al., 2013; Heise, 2014; Huang et al., 2015). As Markus and Kitayama (1991) have noted, such differences typically reflect the effects of different environments, conventions, and cultural values on people's habitual ways of thinking, acting, and expressing themselves (Clore, 1992). Consistent with this research tradition, the second goal in the current study was to investigate how individuals in different cultures react to their instant enemy and instant ally.

Individualism vs. collectivism

The most widely studied dimension of cultural variation is individualism vs. collectivism (Hofstede, 1991, 2011). Individualism emphasizes several features related to personal achievement, such as ability, talent, personal goals, independence, and self-reliance. Individualism also involves a focus on the identity of “I” or “myself,” and generally prioritizes personal interests over collective ones. In contrast, collectivism typically prioritizes group goals and interests over personal ones, and emphasizes cohesion within one's social groups. Individuals in collectivist cultures usually feel obligated to sacrifice their own interests if they conflict with the welfare of the larger society (Hui, 1988; Hofstede, 1991; Chan, 1994; Yamaguchi, 1994; Kitayama et al., 1997).

Most Asian cultures tend to be collectivistic, and the primary purpose of communication for collectivists is to maintain harmony (Lee and Yang, 1998; Yang, 2002). Collectivists therefore tend to act in a more circumspect and emotionally restrained way when compared to individualists (Suh et al., 1998), and self-restraint in emotional expression is regarded as an important social skill in the collective cultures (Kitayama et al., 2000). In contrast, individuals in Western cultures, such as Canada and the U.S., are more likely to believe that the straightforward expression of one's emotions is both positive and less likely to provoke subsequent misunderstandings (Tsai, 2016).

Social connections often result from mutual convenience, so relationships and group membership in social environments can be easily formed and dissolved (Chiang, 2010). The degree to which people in a specific social environment believe they can initiate or terminate relationships is known as relational mobility (Schug et al., 2010). Individuals with higher levels of relational mobility, such as those in Western cultures, may pay less attention to their social and physical environments because they are less concerned about causing discomfort to others, making it easier for them to initiate or terminate social relationships (Martin et al., 2019). People tend to form self-conceptions that are appropriate to their sociocultural contexts. For example, Markus and Kitayama (1991) explain that individuals living in individualist environments are more likely to perceive themselves as operating independent of others, which allows them to act in ways that reflect their internal tendencies, preferences, and values. In contrast, individuals living in collectivist environments are more likely to form an interdependent self-construal, a sense of self that enables them to act in ways that foster and maintain harmonious relationships.

Besides observing behavioral differences among different cultures, researchers have also investigated language differences between different cultures because language is the primary medium for cultural transmission (Schroder et al., 2013; Heise, 2014). Previous studies have reported different communication styles between Eastern and Western cultures. For example, because Confucianism emphasizes humility and modesty as cultural values, Asian collectivists tend to have a “high-context” communication style in which most information is assumed to be already available in the physical context or internalized within the person (Hall, 1976), and this style leads Asian collectivists to provide more ambiguous responses than Western individualists do. Asians also tend to express fewer emotions in public. In Confucianism, humility is related to a world-focused rather than self-focused communication style, so Asians' communications usually focus on places, objects, and events, rather than on the direct expression of personal feelings (Yang, 1988; Yum, 1988; Freeman and Habermann, 1996; Elsevier, 1998; Gudykunst, 2001; Park and Kim, 2008). Additionally, according to Hall (1976), there is a fundamental difference between Eastern and Western cultures in how they convey and interpret meaning through communication. In their discussion of high-context and low-context cultures, Kittler et al. (2011) argue that meaning is created through a combination of context and information. For instance, people in people in high-context cultures (e.g., Japan, Korea, or China) rely heavily on contextual cues to avoid conflict or embarrassment. In contrast, people in low-context cultures (e.g., the U.S, Canada, or the Netherlands) tend to use explicit and coded messages, such as written or verbal language, and rely less on context to convey meaning (Gudykunst et al., 1996).

In the present study, we propose that people's use of language to describe an instant ally and an instant enemy differ in an individualist vs. a collectivist culture because the perspectives on interpersonal relations are different in their social constructions according to the Social Identity Theory (SIT; Tajfel and Turner, 1979, 1986). For instance, West Africans exhibited higher levels of apprehension toward making friends than North Americans did, and this difference may be attributed to the fact that North Americans tend to be less aware of the potential risks associated with friendship due to living in relatively safer environments (Adams and Plaut, 2003). In addition, SIT (Tajfel and Turner, 1986) suggests that positive behavior, both verbal and nonverbal, stems from positive evaluations of the in-group rather than the out-group (Turner et al., 1979). To counteract the potential negative impact of others' reactions and avoid social rejection, people may exercise personal restraint (Downey and Feldman, 1996). Furthermore, sensitivity to social rejection varies across cultures. For example, Hong Kong-Chinese individuals may be more sensitive to social rejection and have stronger beliefs in destiny than European Canadians due to the lower perception of relational mobility in Hong Kongese culture (Lou and Li, 2017). As another example, Russell et al. (2019) examined how social orientations affect social attention in Japanese and European Canadians and found that the relationship context influences whether East Asians and North Americans prioritize congruence with others. Contextual factors such as relationship types and distances may also impact behavior, suggesting that cultural differences in the self-conceptions are more complex than previously thought (e.g., Markus and Kitayama, 1991; Triandis, 1995).

As Nisbett et al. (2001) have noted, the thinking of Eastern cultures tends to be holistic, in that individuals are more likely to consider the sources of causality in the entire environment and tend to explain events in terms of situational factors. In contrast, individuals in Western cultures tend to have a low-context communication style in which their own thoughts and feelings are given greater emphasis and expression, and which often relies on intuition than on a complex assessment of causality (Hall, 1976; Kim, 1993, 1994; Gudykunst et al., 1996; Nisbett et al., 2001). Interestingly, both written and oral expressions should reveal these cultural differences but have rarely been studied, to the best of our knowledge. Such a study would be complicated by the fact that sentence structures often differ substantially among languages. On the other hand, because language use is an important source of information about people's deepest thoughts and feelings, we would expect to see the same differences in the cognitive and perceptual styles of our American and Taiwanese respondents that Nisbett et al. (2001) have identified. Indeed, perhaps the most essential attribute of cultures is communication (Giles and Watson, 2008) because cultures have to depend on languages to adopt, develop, survive, and flourish (McQuail, 1992). The current study therefore used a new method of studying individual cultural differences in the psychological categories of words used to describe instant allies and instant enemies. These differences are expected to provide insight into how and what people think and feel in different cultures.

Ingroup/outgroup distinctions within a culture

Cultural differences are not the only factors that affect people's behaviors in social interactions. When two people meet for the first time, they each form an impression of the other person. According to Rogers and Biesanz (2015), this first impression is more likely to be influenced by information such as stereotypes about social groups (Fiske and Neuberg, 1990) or an understanding of what people are like on average rather than information that is directly observed during the initial interaction. In addition, people's initial reactions to a stranger are determined more by their perceived group membership than by their personal characteristics, attitudes, or interests. This is particularly true when there is a history of conflict or tension with other members of the stranger's apparent “outgroup.” For example, sports teams compete with each other in zero-sum games in which one group's win comes at the expense of the other group's loss (Branscombe and Wann, 1994). That this type of perceived competition could engender mutual hostility was noted early on by Allport (1954/1979) and by Sherif et al. (1961), among others. In addition, there is evidence that the simple distinction between ingroup vs. outgroup is itself sufficient to create prejudice and discrimination, as illustrated in the research stimulated by Tajfel and Turner's (1979) Social Identity Theory. Indeed, social categorization is a sufficient antecedent of ingroup-favoring discrimination (e.g., Tajfel's minimal group paradigm; Tajfel, 1970), and the mere recognition that the other person is an outgroup member may be sufficient to cause the other to be regarded as an “instant enemy” (cf . Sherif et al., 1961).

What behaviors, what behaviors might typify such interactions? One obvious prediction is that instant enemy encounters will be characterized by expressions of antipathy and aggressive behavior, because we tend to dislike and aggress against those whom we believe to be our adversaries (Pulkkinen, 1987). For example, the research on peer victimization and mutual antipathies (which are both similar to the “instant enemy” phenomenon), reveals that these relationships are fraught with the various forms of aggression and mistrust (Kochenderfer and Ladd, 1996; Crick and Bigbee, 1998). On the other hand, interactions with an ingroup member generally lead to more positive emotions such as trust and caring (Allport, 1954/1979; Amodio and Devine, 2006; Ratner et al., 2014). More generally, the study of intergroup relations in psychology shows how the brain processes information from the social environment and various stimuli to form individuals' perceptions (Tajfel, 1982), which can be either positive or negative.

Intergroup communication

In the current study, we asked participants to report incidents where they met a stranger and discovered that they were instant allies/enemies. The instructions gave examples that individuals met someone and discovered that they were affiliated with the same team, group, social cause, or organization that they both identified with strongly, or they were affiliated with different teams, groups, social causes, or organizations whose goals were in direct competition with each other, such as political allies (both of them being staunch conservatives or liberals) or political opposites (one of them being a staunch conservative and the other one being a staunch liberal) (see Appendix 3). In this study setting, participants were guided to think about their instant enemies/allies based on their social/group identity. In addition, the study required participants to report retrospective experiences of encountering an instant enemy and an instant ally, therefore the descriptions of these encounters might involve both verbal and non-verbal communicative behaviors.

Communication Accommodation Theory (CAT, developed from Speech Accommodation Theory; Giles, 1973) focuses on both verbal and nonverbal behaviors in social interactions and argues that individuals accommodate their speech, vocal patterns, and gestures to their interaction partners, consistent with the assumptions of SIT (Tajfel and Turner, 1979). CAT suggests that individuals categorize themselves and others using language (Reid, 2012), and according to Burgoon et al. (2017), this entails evaluating not only verbal messages but also those encoded in nonverbal cues or symbolic characteristics of strangers (e.g., appearance, race, religious beliefs, accent, gestures, or personality) as well as other information not delivered in words. In addition, according to the description of Bruner (1957, as cited in Cikara and Van Bavel, 2014) when someone encounters a new person or group, they make social categorizations of both self and other based on their prior knowledge. These self and social classifications in turn activate group or individual preferences in intergroup relationships (Cikara and Van Bavel, 2014). As Tajfel and Turner (1986) have argued, social categorizations are, in effect, cognitive tools that partition and organize the social world, prompting individuals to participate in diverse social behaviors while simultaneously providing a framework for self-referential guidance (social identity). As a result, individual try to adjust their communicative behavior dynamically during interactions based on their evaluation and perceptions of the participants' personal characteristics, as well as their intentions of maintaining a favorable social and personal identity (Dragojevic et al., 2016).

Based on CAT, there are several ways to adjust communication that help individuals create or maintain their positive personal and social identities. The major strategies are convergence, divergence, and maintenance (Gallois et al., 2005; Dragojevic et al., 2016; Adams et al., 2018). Convergence refers to adjusting one's communicative behaviors to be similar to his or her interlocutor(s) verbally, non-verbally, or both based on Similarity-Attraction Theory (Byrne et al., 1971). Increasing perceived interpersonal similarity also increases interpersonal attraction. In contrast, divergence refers to adjusting communicative behaviors to be more dissimilar to interlocutors in order to signify differences, whereas maintenance refers to no adjustment or accommodation to interlocutors, which has functions similar to divergence. Divergence or maintenance behaviors typically convey a message of dislike according to Similarity-Attraction Theory (Byrne et al., 1971), and tend to reinforce social identity by emphasizing distinctiveness according to SIT (Tajfel and Turner, 1979, 1986).

These theoretical considerations lead us to predict that when they encounter an instant ally, individuals are more likely to apply the convergence strategy, whereas when they encounter an instant enemy, they are more likely to apply the divergence strategy, with effects that should be evident in both their conversation and their written retrospective recall as well. With regard to cultural differences, Gallois and colleague reported that collectivists belong to few ingroups but have a strong and loyal ingroup identity, leading them to make stronger distinctions between the ingroup and outgroup. In contrast, individualists belong to relatively many ingroups and emphasize a personal rather than an ingroup identity more; therefore, they tend to make more interpersonal comparisons but fewer intergroup comparisons (Gallois et al., 1995). From CAT's perspective, although a convergence strategy would be adopted more often in encountering ingroup members and divergence would be used more often in encountering outgroup members, individualists compared to collectivists may be more likely to display convergence to outgroups in a relatively positive way because of their softer group boundaries. Collectivists, on the other hand, may be more likely to diverge from outgroups because of their harder group boundaries (Giles, 1979; Gallois et al., 1995; Dragojevic et al., 2016).

Overall, we therefore expect that people's reports of their encounters with an instant ally will be affectively positive and accepting of the other person by convergence, whereas people's reports of their encounters with an instant enemy will be affectively negative and rejecting (e.g., critical and dismissive) of the other person by divergence. This was the first hypothesis that we sought to test in the present investigation, but the cross-cultural aspect of the study is equally important. One culture (i.e., Taiwanese) might, for example, encourage a very strong distinction between ingroup and outgroup members that could be evident across a wide range of outcome measures. On the other hand, another culture (i.e., American) might prescribe a much weaker distinction between ingroup and outgroup members, perhaps because of a strong hospitality norm or because of demographic ideals (e.g., Heine and Lehman, 1997; Triandis and Trafimow, 2001; Hewstone et al., 2002).

Finally, specific cultural features, such as norms for displaying emotions, can also impact the particular content of one's perceptions and expressed emotional reactions toward in-group and out-group members (Parkinson et al., 2004; Caprariello et al., 2009; Mackie and Smith, 2015). These norms are defined as the culturally-accepted ways in which individuals can express their emotions, including what is considered acceptable or unacceptable behavior, and the rules for expressing emotions to others, including when, how, and to whom (Matsumoto et al., 1999). For instance, a comparison of emotion display norms in Canada, the U.S., and Japan revealed that the Japanese tended to suppress the expression of strong emotions such as anger, scorn, and disgust compared to the members of the two North American countries. Moreover, the Japanese communicated their positive emotions, such as happiness and surprise, less frequently than the members of the Canadian sample did (Gullekson and Vancouver, 2010).

Content analysis using linguistic inquiry word count (LIWC)

To identify the content differences in writing that are associated either with cultural differences or with the ingroup/outgroup distinction, we used the LIWC (Linguistic Inquiry Word Count) software program developed by Pennebaker and his colleagues (Pennebaker et al., 2007). LIWC analysis is, by now, a widely accepted research tool. It has, for example, been used in many previous investigations of how linguistic content varies as a function of variables such as the respondent's mental state (Campbell, 2003; Pennebaker and Stone, 2004; Kahn et al., 2007; Pennebaker and Chung, 2007), the respondent's personality (Pennebaker and Graybeal, 2001; Lee et al., 2007; Oliver et al., 2008), or the respondent's current situation (Mehl and Pennebaker, 2003; Pasupathi, 2007; Vrij et al., 2007). It therefore seemed reasonable to expect that LIWC could also be used to identify cultural and/or ingroup/outgroup differences as well.

Language can signify a person's social identity (Scott, 2007). For example, individuals use language to signal different levels of formality, social distance, and psychological distance (Iwasaki and Horie, 2000). Language represents more than just a medium for communication; it can also be used to study the convergence and divergence of behaviors within social groupings (Ethier and Deaux, 1994; Bryden et al., 2013). There is evidence, for example, that individuals' linguistic expressions depend on the community culture within which they are currently interacting (Tamburrini et al., 2015).

To recall a communication event in a participant's story is to describe a direct verbal conversation that reflects a person's intentions, interests, and emotions, such as fear, anger, like, and dislike, as defined by Ekman (1997). Words as expressions of language categories can also convey individuals' positive feelings of belonging or acceptance (Baumeister and Leary, 1995) or their negative feelings reflective of social rejection, avoidance, and ignorance (Lambert and Hopwood, 2016). Accordingly, the present study examined how individuals manage their language when adjusting to a particular social situation by convergence, divergence, and maintenance (Stabile et al., 2013).

The LIWC (LIWC2007; Pennebaker et al., 2007) software program enables researchers to break down the specific categories of word use in text-file samples of each participant's writing and obtain the percentage of words that belong to each of 80 linguistic categories. These categories include standard linguistic categories (pronouns, negations, assents, articles, prepositions, and numbers), psychological processes (words about affective or emotional processes, cognitive processes, sensory and perceptual processes, and social processes), relativity (words about time, space, and motion), personal concerns (words about occupation, leisure activity, money and financial issues, metaphysical issues, physical states and functions), and other, more miscellaneous categories that were developed for use in previous research (e.g., swear words and non-fluencies).

In recent years, the developers of LIWC have created versions that can be used to categorize the words in different languages, including Mandarin Chinese. In the present study, we used both the original English-language version of LIWC and the newer, Mandarin Chinese-language version of LIWC to compare and contrast U.S. and Taiwanese college students' written reports about (1) a situation in which they met a person whom they regarded as an “instant enemy,” and (2) another situation in which they met a person whom they regarded as an “instant ally.” We expected the resulting data to shed light on both ingroup/outgroup differences and cultural differences in the experience and perception of an “instant enemy” and an “instant ally.” By applying LIWC to the respondents' writing, we were able to analyze the psychological facets of word-category usage in various situations and cultures.

Based on the complementary theoretical perspectives of CAT and SIT, we proposed that individual identity has an impact on communication behavior when adapting to social interactions. With regard to possible cultural influences, we investigated differences between Western respondents (the Americans) and Asian respondents (Taiwanese) in how they use words from different linguistic categories in relationship contexts that tend to evoke either convergence or divergence). Previous research has suggested that low-context cultures, such as those found in America and the West, tend to place a greater emphasis on self-expression and promotion, while high-context cultures, such as those found in Taiwan and other parts of Asia, prioritize pleasing others and controlling emotional expression for successful communication. Therefore, the current study aims to answer two research questions: (1) Are there differences in linguistic expression when recalling encounters with strangers as either an instant ally or an instant enemy? (2) Are there differences in verbal and linguistic expressions between Americans and Taiwanese people when encountering strangers as an instant ally or enemy? The study will use the 80 linguistic categories of the Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC) to identify content differences in verbal expression between situational contexts (ally vs. enemy) and cultural contexts (Americans vs. Taiwanese). The study was expected to demonstrate that when comparing people from different cultures, word-category usage might disclose both well-established and novelty findings.

Method

Participants

A previous study comparing Eastern and Western perspectives on interpersonal relations as social constructs demonstrated cultural differences (McCann and Giles, 2006). In light of these findings, the present study chose to focus on Americans and Taiwanese as they represent high-context and low-context cultures as well as individualistic and collectivistic cultures, respectively (Hofstede, 1991, 2011). These cultural differences were chosen to highlight the variation that exists between cultures. A prior power analysis was carried out using G*Power to estimate the required sample size of each group. The estimation of the required sample was calculated under the condition of a small effect size, with Cohen's f = 0.13. It was revealed that the total required sample should be 467 (around 230 participants per country).

The U.S. participants were 262 undergraduate students at a large-sized public research university in the Southern United States. 236 of the 262 participants answered the online survey completely; 16 provided an incident report involving an instant ally but not one involving an instant enemy; 3 provided an incident report involving an instant enemy but not one involving an instant ally, and 7 did not provide either type of incident report. The 262 respondents included 70 males, 185 females, and 7 individuals who did not provide their gender. The sample proportions based on ethnic backgrounds were 38.8% White/Anglo; 19.5% Black/African; 13.4% Hispanic/Latino; 15.3% Asian/Pacific Islander; 4.6% Middle Eastern; 5.7% multiracial; and 2.7% missing data.

The Taiwanese participants were 250 undergraduate students at a middle-sized national/public research university in Northern Taiwan. 198 participants answered the online survey completely; 26 provided an incident report involving an instant ally but not one involving an instant enemy; 23 provided an incident report involving an instant enemy but not one involving an instant ally; and 3 did not provide either type of incident report.1The 250 respondents included 110 males and 140 females.

Procedure

The procedure was the same for both the U.S. and the Taiwanese samples. In text boxes that appeared with accompanying instructions in the online survey to which they were directed, the respondents were asked to provide paragraph-long written accounts of (1) an incident in which they met a person whom they regarded as an “instant enemy” and (2) a separate incident in which they met a person whom they regarded as an “instant ally.” The order in which these two accounts were written was counterbalanced: half of the respondents wrote their instant enemy account first, and the other half wrote their instant ally account first. In the instructions that introduced these two parts of the survey (see Appendix 3), we asked the respondents to think about the concept of “instant enemies” (or “instant allies”) and then write a paragraph in which they described an actual (and preferably recent) incident from their own life in which they found themselves in the presence of a stranger whom they quickly came to regard as an “instant enemy” (or an “instant ally”).

For example, in the U.S. sample, one respondent described his “instant enemy” as a person who was on the opposing team in a basketball game, whereas another respondent described his “instant ally” as a person who had many things in common with himself. In the Taiwan sample, one respondent described his “instant enemy” as a person who had very different opinions and a very dissimilar personality from his own, whereas another respondent described her “instant ally” as a person who had attended and graduated from the same high school that she had.

Content analysis of the incident report data using LIWC 2007

We separately analyzed the linguistic content of each participant's reported incidents in which they encountered an instant ally or an instant enemy using the Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count software (LIWC, 2007) that was developed by Pennebaker, Francis, and Booth. LIWC2007 processed the text files for each of the participant's two incident reports and computed the percentage of the words in each file that belonged to each of 81 linguistic category measures.

These measures include standard linguistic categories (pronouns, negations, assents, articles, prepositions, and number), psychological processes (words about affective or emotional processes, cognitive processes, sensory and perceptual processes, and social processes), relativity (words about time, space, and motion), personal concerns (words about occupation, leisure activity, money and financial issues, metaphysical issues, physical states and functions), and certain experimental dimensions that were developed for use in previous research (swear words, non-fluencies, etc.). However, four of these categories are never found in Mandarin Chinese (i.e., articles, past tense, present tense, future tense), and because near-zero word use in certain LIWC categories could invalidate the results of the corresponding statistical tests, we followed a convention recommended by Dr. James Pennebaker (personal communication, 2012) and deleted all LIWC categories with a percentage use of < 1% in both the U.S. and the Taiwanese samples. The application of this selection criterion resulted in the retention of 43 of the original 81 LIWC categories.

To understand how interactions with strangers can lead to either immediate alliance or enmity, this study examines the CAT framework developed by Gallois et al. (2005) and categorized the linguistic expressions into three groups: (1) divergence, which encompasses denial, negation, swear words, negative emotions, anxiety, anger, discrepancy, exclusivity, filler words, positive emotions (sadness), and inclusivity; (2) convergence, which includes social processes, positive emotions, inclusivity, personal concerns, and (3) maintenance, which covers agreement, insight, causation, tentativeness, and non-fluencies. Overall, encounters with instant enemies were expected to feature language that was more exclusive, absolute, and negative, indicating outgroup hostility and divergence, while encounters with instant allies featured language that was more inclusive, less absolute, and more positive, suggesting ingroup favor and convergence in content.

Results

To determine whether the U.S. and the Taiwanese college students reported “instant enemy” and “instant ally” incidents that differed in their linguistic content when compared across both incident type and culture, we analyzed the data for each retained LIWC measure using the same mixed model ANOVA. In this model, culture (Taiwan versus U.S.) was treated as the between-subject independent variable, incident type (Enemy versus Ally) was treated as the within-subjects independent variable, and the 43 retained LIWC categories were the DVs. The culture X incident type interactions were also tested.

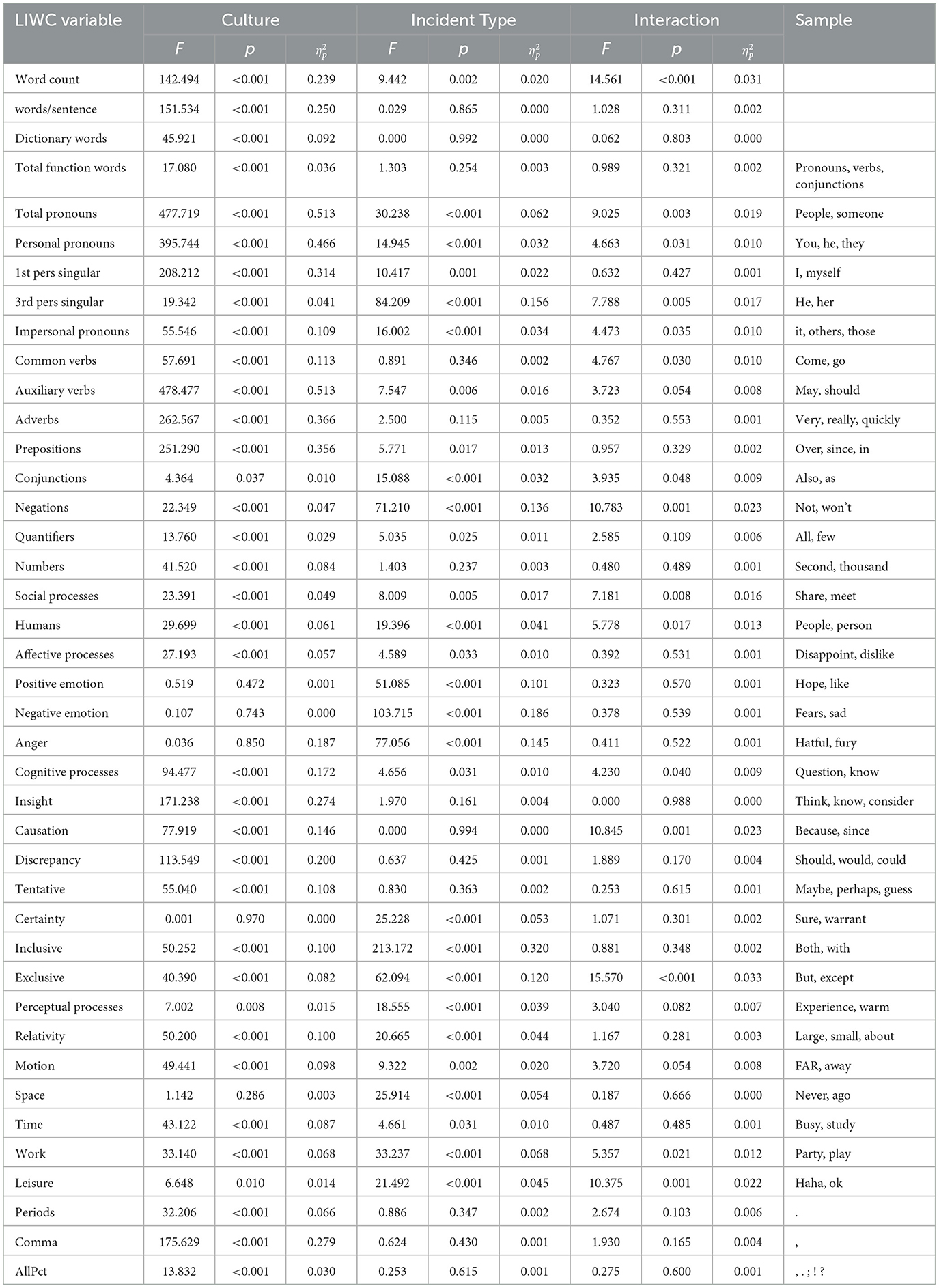

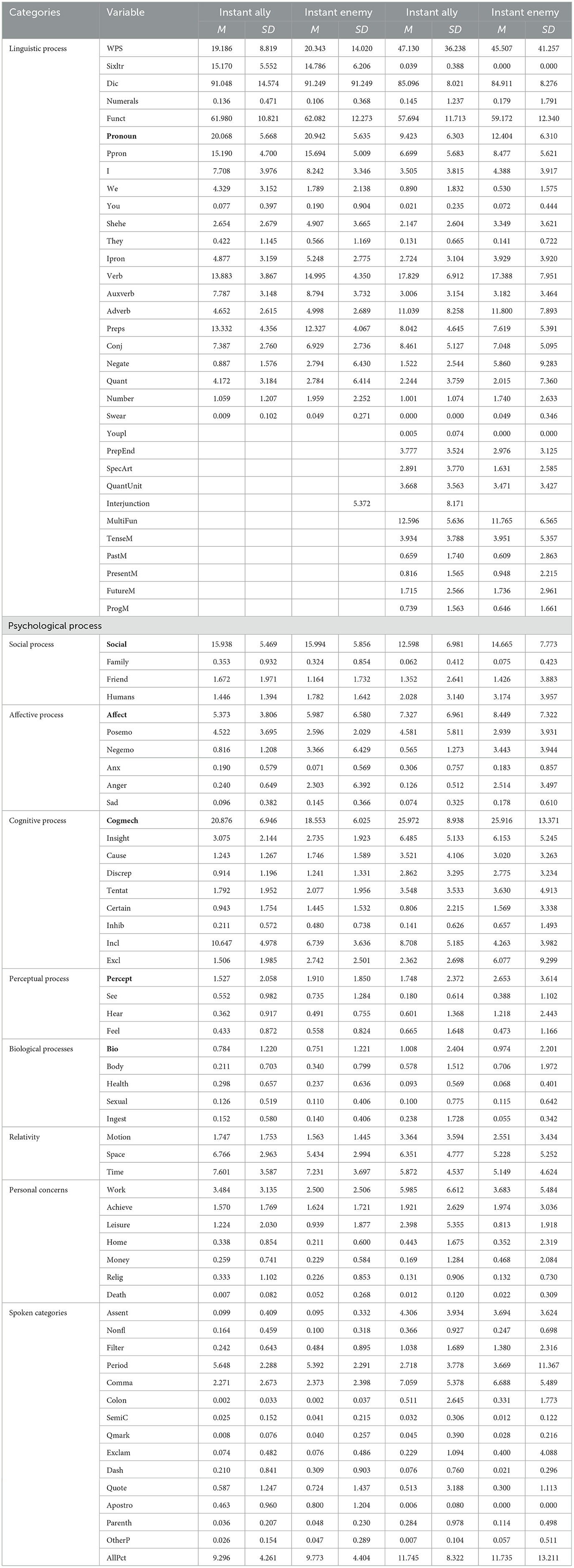

To avoid the inflated Type I error that results when a large number of effects are tested, we adjusted the required significance level from p < 0.05 to a much more stringent p < 0.001 by adopting the Bonferroni family-wise adjustment. The effects that were significant at this more stringent level are reported in Table 1. We first consider the “main effects” of incident type and culture and then consider the significant incident type X culture interaction effects.

Main effects of incident type (instant enemy vs. instant ally)

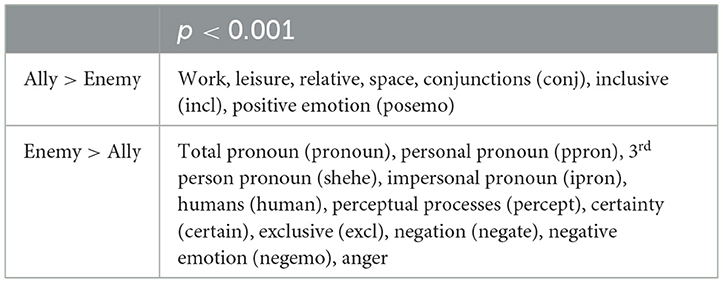

There was a significant (p < 0.001) main effect of incident type in 18 of the 43 retained LIWC categories (see Table 2). Comparing the two incident types (instant ally and instant enemy), there were 11 LIWC categories that were used more frequently to describe encounters with instant enemies, and 7 other categories that were used more frequently to describe encounters with instant allies. The incident-type effects for these category variables were significant (p < 0.001) across both of the cultures studied.

Overall (see Table 5) the mean and standard deviation of all variables of instant ally and instant enemy, the reports of Ally incidents were characterized by the use of more conjunctions (e.g., “and” and “thus”) and more inclusion words (e.g., “with”, “include”, “and”), whereas the reports of Enemy incidents were characterized by the use of more negation words (e.g., “not,” “no”) and exclusion words (e.g., “but,” “without”, “exclude”), as well as certain words that suggest a categorical absolute (e.g., “never,” “always”) for emphasis. Also, and not surprisingly, there were more positive emotion words (e.g., “pretty,” “sure,” “good”) in the accounts of the Ally incidents but more negative emotion words (e.g., “disgust,” “wrong,” “hate,” “blame”) in the accounts of the Enemy incidents). In summary, the accounts of encounters with instant enemies featured words that were more exclusive, more absolute, and more negative, which revealed out-group hatred and divergence in their encounters; whereas the accounts of encounters with instant allies featured words that were more inclusive, less absolute, and more positive, which may indicate in-group favor and convergence in encounter content.

The word categories of pronouns, including both personal pronouns (especially the 3rd person singular pronouns such as “he” and “she”), and impersonal pronouns (e.g., “those”), as well as human words (e.g., “adult,” “person”) were also used more frequently in the accounts of instant enemy than in those of instant ally incidents When viewed in the context of the findings we have just reported above, these data suggest a greater motivation to understand what kind of person the instant enemy was, perhaps in the service of assessing the degree of threat he or she posed and to better identify these kinds of people in the future.

Finally, the respondents' descriptions of Ally incidents were more likely to include words about personal concerns (e.g., “jobs,” “majors”), leisure activities (e.g., “movie,” “apartment,” “cook”), and relative words (e.g., “area,” “bend,” “about,” “large”) that included space words (e.g., “down,” “in”), all of which help to specify the types of situational contexts in which the instant ally encounters occurred. In contrast, the respondents' descriptions of Enemy incidents were more likely to include perceptual processes words (e.g., “hear,” “feel”), suggesting that the instant enemy incidents led the respondents to focus more on their immediate sensations and feelings than on the context in which these sensations and feelings occurred. Because encountering an instant enemy is likely to be more uncommon, more surprising, and more distressing than encountering an instant ally, a shift from a focus on the situational context to one's own perceptual and emotion reactions may underlie this set of findings.

Main effects of culture (Taiwan vs. U.S.)

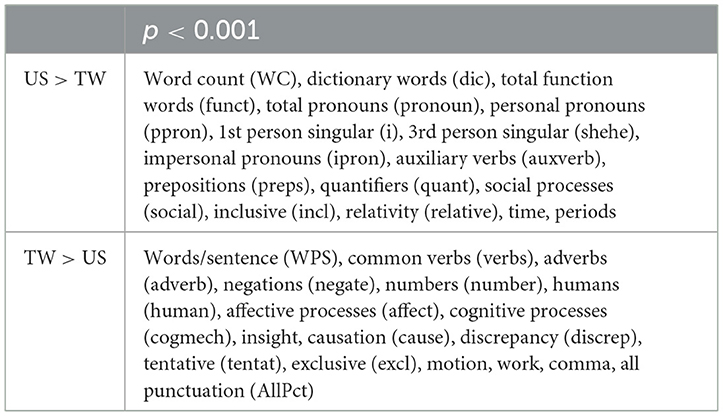

The main effect of the cultural factor was significant in 33 of the 43 retained LIWC categories (see Table 3). There were 16 LIWC categories that were used more frequently in the U.S. sample, and 17 categories that were used more frequently in the Taiwanese sample. Some of these differences appeared to reflect cultural differences in the usual sense; however, others appeared to reflect nothing more than the linguistic and writing conventions that are peculiar to the respective written languages of English and Mandarin Chinese.

Language-based differences

As examples of these language-based differences, the incident accounts in the U.S. sample included more words in total, whereas the average number of words in sentences was higher in the Taiwanese sample. In correspondence with this finding, there were more commas used in the sentences produced by the Taiwanese sample, but more periods used in the accounts provided by the U.S. sample. These findings appear to reflect the differences in the typical sentences that writers construct when using the languages of English vs. Chinese. Compared to the alphabetic characters that are used in English, the characters in Chinese are hieroglyphic and have multiple meanings that must be disambiguated by the context of the text in which they appear (Wang and Chen, 2013). To provide the appropriate disambiguation, average sentences in Chinese tend to be relatively longer than their English-language counterparts but require the use of fewer total words (Wang and Chen, 2013). On the other hand, accounts written in English may require more sentences and therefore need more periods, whereas accounts written in Chinese may require fewer sentences with fewer periods but more commas and other context-defining punctuation.

In addition, auxiliary verbs (e.g., “did,” “had”), prepositions (e.g., “to,” “with,” “above”) and words related to time (e.g., “recently,” “past, “then”) were used more frequently in the U.S. sample, whereas verbs, adverbs, and negations (e.g., “not,” “no”) were used more frequently in the Taiwanese sample. These findings may also reflect the respective natures of the English and Chinese languages. As we know, English specifies tenses, such as past tense, present tense, and future tense, by transforming verbs with auxiliary verbs (e.g., “did,” “do,” “will do,” “have done”), as well by as adding time-related qualifiers such as “recently,” “after,” and “then.” In Chinese, tense is not denoted by the use of verbs or auxiliary verbs. According to Wang and Chen (2013), verbs in English are the center of sentences that control the relationship between components (i.e., subject, object), whereas in Chinese, verbs are usually grouped together within a sentence to represent the time order, a language convention that results in a higher use of verbs in writing. Corresponding with the larger number of verbs, adverbs were also used more frequently in Chinese in order to qualify or modify the verbs.

In addition, because Chinese is written in hieroglyphic characters, it requires more negation words than English does, along with other words that convert a given word into its negation. For example, the English word “dislike” would be expressed as “not like” in Chinese. Furthermore, words related to number (e.g., “one,” “second”) were also used more frequently in the Taiwanese sample than in the U.S. sample. The main reason is that there is no “article” in Chinese. When we say “a boy” in English, “a” is the article. However, in Chinese, the form is “one boy” where “one” would be placed in the category of words related to number.

Culture-based differences

Other differences between the accounts written by U.S. vs. Taiwanese respondents appear to be based less on the respective language conventions of English vs. Chinese and more on culture-based differences, as they are traditionally conceived. For example, Nisbett et al.'s (2001) have noted that individuals in Western cultures tend to have relatively friendly and open communication styles and to convey information that is highly personalized, whereas individuals in Asian cultures tend to have more reserved communication styles and to convey information that is less personalized but more “holistic” (i.e., more influenced by the surrounding social and physical environment, giving more attention to backgrounds and their links to the targets). In addition, individualists are found to possess softer boundaries between ingroups and outgroup whereas collectivists have harder boundaries (Giles, 1979; Gallois et al., 1995).

Consistent with Nisbett et al.'s (2001) observations regarding friendliness and the tendency to personalize, as well as Giles's (1979) and Gallois et al.'s (1995) proposal of individualists' softer boundaries between ingroups and outgroups, we found that the American respondents used more “personalizing” pronouns (e.g., 1st person singular, 3rd person singular), social process words (e.g., “meet,” “share”), inclusive words (e.g., “all,” “both,” and “with”), and quantifiers (most were positive quantifiers, such as “many,” “much,” “more”), whereas the Taiwanese respondents used more generic and ambiguous references to people in general (e.g., “person, “people,” “someone”), as well as more exclusive words (e.g., “but,” “except”). According to the differences in words, perhaps the Taiwanese declined the importance of the self-definition within intergroup comparisons as a motivational base to prevent discrimination (Vanbeselaere, 1991), in order to succeed the social interactions (Brewer, 1991); conversely, the Americans adopted more self-promotions and focused on their achievements (Li and Masuda, 2015).

Moreover, consistent with Nisbett et al.'s (2001) observations regarding the Asian tendency to view things more holistically, Wang and Chen (2013) and Li et al. (2014) reported that Asians tend to have thoughts and perceptions that are more holistic and integrated with the surrounding environment, whereas Americans tend to have thoughts and perceptions that are more rational and analytic. In the present study, we found that the Taiwanese respondents were more likely to use words that conveyed thoughtfulness, insight, awareness of causation, and awareness of discrepancy. Specifically, when compared to the American respondents, the Taiwanese respondents used more words that indicated insight [e.g., “think,” “know,” “consider”), cognitive processes (e.g., “question,” “know”)], affective process (e.g., “hope,” “like,” “conflict,” “friend”), awareness of causation (e.g., “because,” “since”), awareness of discrepancy (e.g., “would,” “could,” “should”), and awareness that conclusions must be tentative (e.g., “maybe,” “perhaps,” “guess”). These findings suggest that the Taiwanese respondents were more likely to see other people within a context of causal factors leading to outcomes that are often tentative and inconclusive, whereas American respondents were more likely to see others as distinct individuals whom one can know with less regard to the context in which they think and act.

Last, the category of words relating to work (e.g., “classmate,” “class,” “college,” “senior high”) was also used more frequently in the Taiwanese sample. When we read the texts carefully, we found that the most frequently used words relating to work were “classmate,” “class,” and even “senior high school.” In other words, when asked to think of an incident in which they encountered an instant enemy or an instant ally, our Taiwanese respondents appeared to be more sensitive to the social context in which these incidents had occurred. When the Taiwanese face an intergroup context, their word expression presented as an accommodative communication way (e.g., maintaining self-impression, reaching positive conversation; Giles and Ogay, 2006), compared to their Americans.

Incident type X culture interaction effects

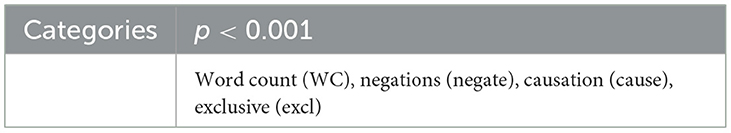

Finally, our analyses revealed four LIWC categories for which there was a significant interaction of incident type and culture (see Table 4).

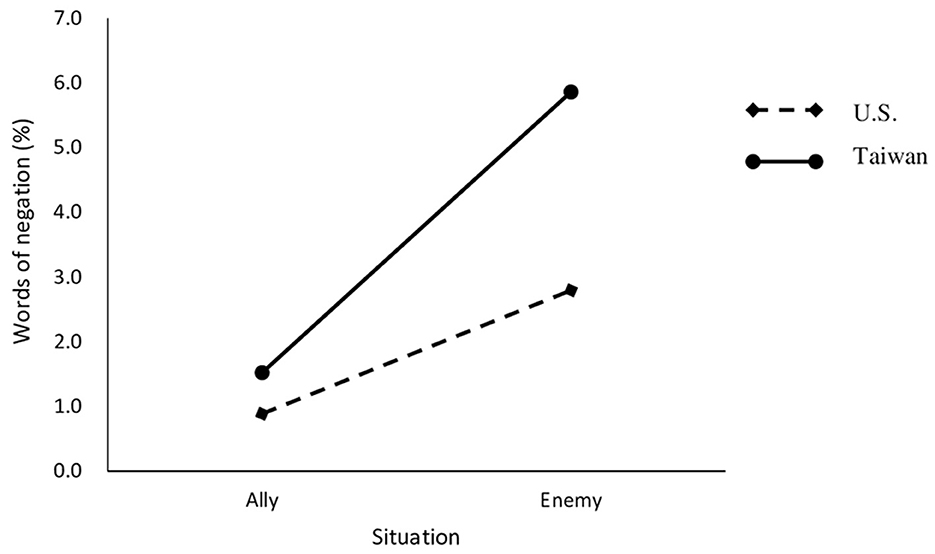

First, negation words were generally used more in the instant enemy situation than in the ally situation, but this difference was larger in the Taiwanese sample than in the U.S. sample (see Figure 1). A possible language-based explanation was noted above: that hieroglyphic characters in Chinese require more negation words to be paired with other words in order to convey the concept of negation.

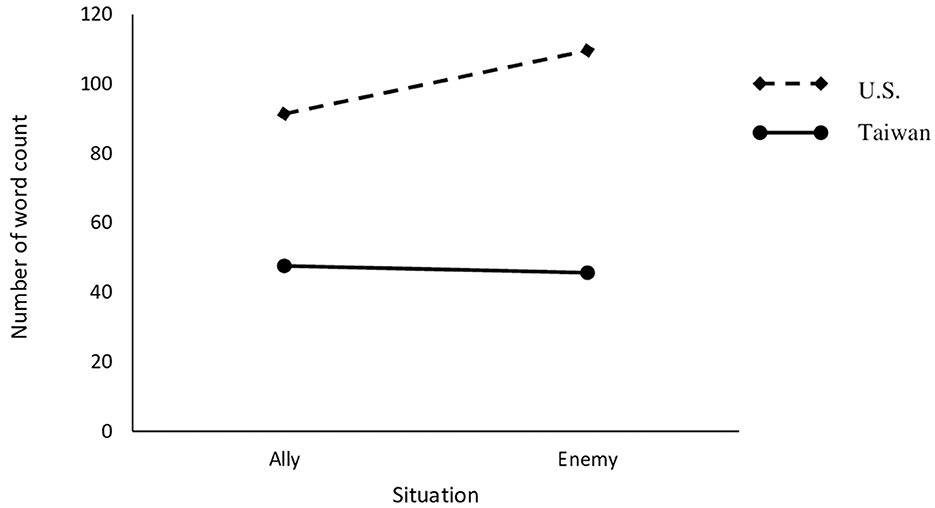

Second, although the American respondents used more overall words than the Taiwanese respondents did, the Americans used significantly more words to describe their instant enemy incident than their instant ally incident, whereas no such difference was evident in the Taiwanese sample (see Figure 2). The wordier accounts of the instant enemy incident observed in the American sample might be accounted for, at least in part, by the next interaction we report.

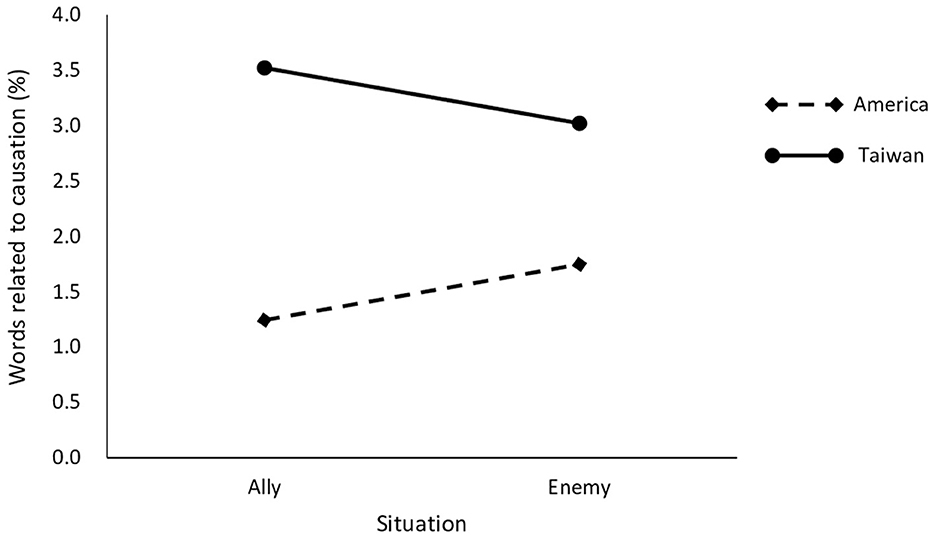

Third, we found that causation words appeared more frequently in the Enemy situation compared to in the Ally situation in the American sample, whereas the reverse occurred in the Taiwanese sample (see Figure 3). Because there is evidence that Americans have relatively friendly and open communication styles (Nisbett et al., 2001), they might have felt more need to explain at length any failure to avert the tense interactions they experienced in the unpleasant enemy situation. However, because the Taiwanese respondents are expected to work diligently to achieve the cultural values of “harmony” and group cohesion, they might be more sensitive to causal factors that led another person to be viewed as their instant ally. Overall, the Taiwanese used more causation words in reporting both the enemy and the ally incidents than did the Americans, as we have noted previously.

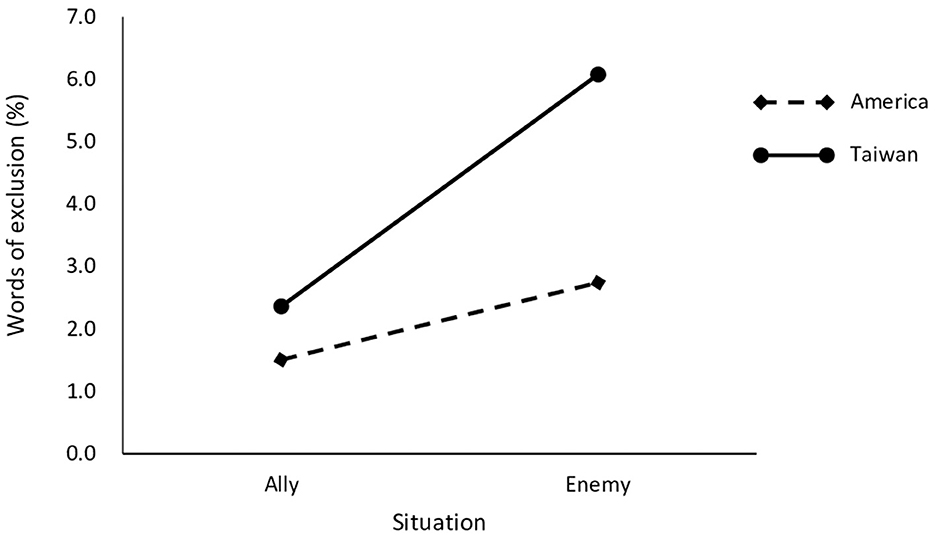

Fourth, exclusive words were used more in the enemy incidents than in the ally incidents, but this difference was greater in the Taiwanese sample than in the U.S. sample (see Figure 4). Specifically, we found that respondents in the Taiwanese sample were more likely to give positive information before mentioning negative statements, and use exclusive words (such as “but,” “except”) as connections, especially in the Enemy situation. We speculate that because Taiwanese have clearer group boundaries, are more reserved and more motivated to maintain society harmony and in-group cohesion, the exclusive words were used to moderate the negative information by prefacing it with positive information that would soften its impact.

Discussion

The present study used the Linguistic Inquiry Word Count software (LIWC) to test for differences in how respondents from two cultures (U.S. and Taiwan) described their initial encounters with an “instant enemy” and with an “instant ally.” The study involved 512 college students (262 from the U.S. and 250 from Taiwan), and all participants were required to write about their experience during an initial encounter with an instant enemy and an instant ally (order counterbalanced).2 The text accounts of both the enemy and ally encounters were later analyzed by LIWC (English and Mandarin-Chinese versions) to calculate the percentages of word usage in 81 LIWC word categories, and only 43 LIWC word categories with an average usage over 1% were examined in the current study.

Main effects of incident type (instant enemy vs. instant ally)

With regard to the ingroup/outgroup distinction, as captured by the contrast between the “instant ally' and the “instant enemy,” we predicted that the respondents' reports of their encounters with an instant ally would be affectively positive and accepting of the other person by using more convergence strategies in interactions, whereas the respondents' reports of their encounters with an instant enemy would be affectively negative and rejecting (e.g., critical and dismissive) of the other person by adopting relative divergence strategies in interactions. These predictions were confirmed in our analyses of the LIWC data. Specifically, we found that regardless of the respondents' nationality, inclusive (e.g., “both,” “with,” “we,” “and”) and positive emotion words (e.g., “pretty,” “sure,” “good”) were both used more frequently to describe the instant ally encounters than to describe the instant enemy encounters. On the other hand, the word categories exclusive (e.g., “but,” “without”), negation (e.g., “didn't”), certainty (e.g., “absolutely,” “always,” “extremely,” “never”), and negative emotions (e.g., “disgust,” “wrong”) including anger (e.g., “hate,” “blame”) were used more frequently in reports of the instant enemy encounters. As Motro and Sullivan's (2017) findings, the individuals who see a threat (e.g., instant enemy) would initially experience anxiety, subsequently adopt an avoidance orientation and try to escape from the threat. Inclusive word expressions served as indicators of a preference for avoiding discrimination against others, while exclusive words suggested interpersonal rejection. Moreover, the use of positive and negative tones provided insight into individuals' psychological states, and stylistic phrases were employed to measure their social interaction (Tausczik and Pennebaker, 2010). Absolute or certain words expressions (such as always or never) were also used by our participants to convey a definite impression of an instant enemy incident, in accordance with the Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC) framework (Pennebaker et al., 2007). On the other hand, relative words (such as area, bend, exit, and stop) were employed to express consideration in relation to instant ally incidents. This is a possible explanation for the use of relative words in instant ally encounters.

Obviously, these findings are commonsensical and intuitive, rather than counterintuitive, but they are important in showing that the word categories used to distinguish an instant ally from an instant enemy are similar across two very different languages (English and Mandarin Chinese), suggesting some degree of cross-cultural generality in this regard. By implication, these findings indicate that a LIWC analysis is sensitive enough to reveal predicted effects, and that it might also be sensitive enough to reveal unexpected effects as well. As an example of such an expected effect, we found that our respondents' descriptions of instant ally encounters were more likely to be put into a context defined by words related to leisure, work, and space which categorized into personal concerns. In contrast, their descriptions of instant enemy encounters were more likely to ignore the context and focus instead on what type of person the instant enemy was, by using more personal pronouns and words by denoting specific categories of humans (e.g., “man,” “boy”). This finding supports the suggestion put forward by (DeVito and DeVito, 2007) in his book “The Interpersonal Communication,” which outlines the first two stages of interpersonal relationships as involving contact and the exchange of essential details such as name and place of origin between the two communication participants. If the first stage of contact generates a positive impression, it leads to the second stage of “involvement,” during which both individuals seek to learn more about each other. Discussions during this phase may revolve around topics such as work, education, and hobbies. If both individuals successfully pass through the involvement stage, the initial contact is considered a success, and the communicators are identified as allies.

Main effects of culture (Taiwan vs. U.S.)

The cultural differences we found in our data are remarkably consistent with the differences between Asian culture and U.S. culture that previous writers have identified. Previous studies have found that Western respondents tend to have softer group boundaries (Giles, 1979; Gallois et al., 1995; Dragojevic et al., 2016) and have a low-context communication style in which their own thoughts and feelings are given greater emphasis and expression (Gudykunst, 2001; Park and Kim, 2008). This individualistic style is relatively friendly and open, and it contains more personalized information (Nisbett et al., 2001). In contrast, Asian respondents tend to have relatively harder group boundaries (Schug et al., 2009), as well as have a high-context communication style that contains more ambiguous responses (Gudykunst, 2001). This collectivistic style is more world-focused than self-focused, and it tends to discourage the direct expression of one's own personal feelings (Hall, 1976; Yang, 1988; Yum, 1988; Freeman and Habermann, 1996; Elsevier, 1998; Gudykunst, 2001; Nisbett et al., 2001; Park and Kim, 2008). This finding is consistent with the study conducted by Schug et al. (2009), which showed that the similarity between friendship partners was higher in the U.S. than in Japan, although the preference for similarity in friends did not differ between the U.S. and Japan. This suggests that Asian individuals, including the Taiwanese, may find it easier to accept dissimilarity and adjust for harmony (Russell et al., 2019). As a result, we found that Americans used the pronoun ‘I” more frequently, implying that individuals from social contexts with higher relational mobility might be more likely to engage in self-disclosure (Schug et al., 2010). Similarly, our study aligns with the findings of Gullekson and Vancouver (2010), which indicate that Taiwanese individuals were more considerate and thoughtful in their interactions compared to Americans (see Table 5). For instance, Americans used swear words to convey negative feelings and express negative emotions more frequently, consistent with Tsai (2016), who found that Westerners view such expressions positively and are less likely to freely express their emotions. However, swear words were not used frequently among Taiwanese individuals due to the concept of emotion display norms within collectivist cultures, as Matsumoto (1989) argues that expressions of anger, fear, and sadness should be less intense to avoid interfering with group harmony or cohesion. Additionally, Matsumoto's further research revealed that Japan, an Eastern country, implies less expression intensity compared to Americans (Matsumoto et al., 1999).

Consistent with these thematic cultural differences, we found that our American respondents used more “personalizing” pronouns (e.g., 1st person singular, 3rd person singular), social process words (e.g., “meet,” “share”), inclusive words (e.g., “all,” “both,” and “with”), and quantifiers (most were positive quantifiers, e.g., “many,” “much,” “more”). In contrast, our Taiwanese respondents used more words that conveyed thoughtfulness (words related to cognitive and affective processes, e.g., “question,” “know,” “hope”), insight (e.g., “think,” “know,” “consider”), awareness of causation (e.g., “because,” “since”), awareness of discrepancy (e.g., “would,” “could,” “should”), and awareness of social environment (words related to work, e.g., “class,” “college”) as an attempt toward harmony in terms of collectivism culture (Lee and Yang, 1998; Yang, 2002). Taken together, these findings offer considerable evidence (and within a single data set), that Western individualists have softer group boundaries and have a communication style that can be characterized as friendly, direct, personalized, and emotionally expressive communication style, whereas Asian collectivists have harder group boundaries and have a communication style that can be characterized as more reserved, indirect, and emotionally restrained, one which views other people within a more holistic context of causal factors leading to outcomes that are often tentative and inconclusive. Reflection to this concept, our study identified despite Taiwanese having harder boundaries with strangers (Schug et al. (2009) as require for harmony, Taiwanese as Asian interdependent were willing to be more carefully manage their communication behavior by adapting to be more in-group and employing less negative language expressions (less in swear, negative emotion, negation, inclusion), than American respondents which focus on self (dependent) and freely expressing feeling for rejection which result in instant enemy.

Finally, the data from the current study revealed a pattern of differences that appears to derive from different conventions of the Chinese and English languages. For example, there were generally fewer words in the Taiwanese accounts than in the U.S. accounts because Chinese characters are hieroglyphs that have multiple meanings. However, in order to disambiguate these meanings in Chinese, the context in which the characters appear (i.e., the “sentences”) have to be relatively longer and require more commas and other context-defining punctuation compared to English. On the other hand, the accounts written in English were characterized by shorter sentences, and therefore by more periods (Venezky, 1970, 1999; Perfetti and Liu, 2006; Wang and Chen, 2013). Although these language-based differences may be of greater interest to scholars of comparative linguistics than to social and cross-cultural psychologists, they may also reflect differences in cognitive processes between the two cultures (cf. the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis, Whorf, 1956; Drivonikou et al., 2007; Everett, 2013).

Incident type X culture interaction effects

Although we did not predict any incident type (instant ally vs. instant enemy) X culture interaction effects, we found four significant effects of this type in our data. These unpredicted effects vary in their interpretability, but their presence in the data is noteworthy because they suggest that culture can either amplify or dampen certain differences in the way that an instant ally and an instant enemy are perceived. For example, although the respondents in both samples were more likely to use exclusive words (e.g., “but,” “just,” “except”) in the Enemy situation than in the Ally situation, the Consisted to Nisbett et al. (2001) a typical Eastern thinking cultures, Taiwanese respondents used significantly more exclusive words than the American sample in the Enemy situation—as if to emphasize how exceptional it was to encounter an “instant enemy” in a culture that emphasizes harmony and social cohesion (Lee and Yang, 1998; Yang, 2002).3 Individuals from collectivist cultures such as Taiwan expected to encountered someone who is congruent with their values, but they are also willing to learn and adapt incongruent values as c used to involves in collaboration and solidarity (Gudykunst et al., 1996). Moreover, in terms of communication, individual modify their language to manage convergence, divergence, and maintenance the interpersonal aims (Stabile et al., 2013). Consistent with our study, Taiwanese express more thoughtfulness, insight, awareness of causation, and awareness of discrepancy as within Eastern cultures, there is a strong emphasis on considering the potential consequences of one's actions and how they will impact future social connections with others (Martin et al., 2019). Future research may design to examine the instant ally and enemy phenomena in the relative sophisticated way.

Interpreting the remaining interaction effects is more difficult, and perhaps should be deferred until a follow-up study reveals which of these effects are replicable and which ones are not. For the present, however, we will note that such effects are intriguing in their implication that cultural differences can interact with the ingroup/outgroup distinction in ways that have not yet been identified, let alone predicted.

Conclusion

With regard to ingroup/outgroup differences, we found that inclusive and positive emotion words were frequently used to describe instant ally encounters, demonstrating a sense of similarity and creating a favorable impression (Byrne et al., 1971; Turner et al., 1979), whereas exclusive and negative emotion words were more commonly used in reports of instant enemy encounters, highlighting out-group distinctions (cf. Sherif et al., 1961; Lou and Li, 2017). We also found that our respondents' descriptions of instant ally encounters were more inclined to include context characterized by self-disclosure words associated with leisure, work, and spaces for sharing attraction and commonalities (Schug et al., 2009, 2010; DeVito, 2012). On the other hand, the descriptions of instant enemy encounters often disregarded context, focusing instead on the type of person the instant enemy was, as indicated by a greater usage of personal pronouns and words denoting specific categories of people.

With regard to cultural differences, we replicated previous findings indicating that Western respondents have a low-context communication style in which their own thoughts and feelings are given greater emphasis and direct expression (Gudykunst, 2001; Nisbett et al., 2001; Park and Kim, 2008) whereas Asian respondents have a high-context communication style that focuses more on the external world and less on one's own personal feelings (Hall, 1976; Yang, 1988; Yum, 1988; Freeman and Habermann, 1996; e.g., Elsevier, 1998). An example of the findings is that American respondents tended to use more “personalizing” pronouns which is consistent with individualistic cultures that prioritize self-focus (Hofstede, 1991, 2011), social process words, and inclusive words. In contrast, Taiwanese respondents used more words that expressed thoughtfulness, such as words related to cognitive and affective processes, insight, and awareness of causation (Lee and Yang, 1998; Yang, 2002). Finally, the present study also revealed that culture can either amplify or dampen certain differences in the way that an instant ally and an instant enemy are perceived.

Viewed collectively, the present findings make a strong case that word-category usage, as assessed by the Linguistic Inquiry Word Count software (LIWC), can reveal both well-established and novel findings in comparisons of individuals from different cultures. This study also demonstrates that language use is an important source of information about people's thoughts and feelings, even in cross-cultural settings (Kitayama et al., 2000; Schroder et al., 2013; Heise, 2014; Huang et al., 2015). Researchers can study cultural differences in thoughts and feelings between or among cultures by using linguistic analysis tools such as LIWC. Although languages cannot be compared directly, examining the psychological facets of word-category usage within languages may provide some insights into cultural differences (Tausczik and Pennebaker, 2010). As Giles and Watson (2008) noted, the most essential attribute of cultures may be the styles of communication.

However, follow-up studies should be conducted to determine which of our findings are replicable and will generalize to comparisons between other Western and Eastern cultures. It is also important to keep in mind that some cultural differences are “built into” the respective languages involved, and that distinguishing language-based differences from ones that do not depend on language conventions is a challenging task that may require the cooperative efforts of both cultural linguists and cultural psychologists. As a suggestion for future research, it would be beneficial to expand the sample to include a more diverse range of individuals from different age groups, educational backgrounds, and cultural backgrounds. This could provide a more comprehensive understanding of how cultural differences impact communication in various contexts. Moreover, future studies could utilize more objective measures of communication, such as nonverbal behavior, to complement the linguistic analysis employed in this study.

Another limitation of this study is that it focused solely on encounters with instant allies and instant enemies. While this is a useful starting point, it may not be representative of all interpersonal interactions. Future research could explore how cultural differences impact communication in other types of relationships, such as long-term friendships or romantic partnerships. Finally, while triangulation was used to enhance the trustworthiness of the findings, it is important to acknowledge that the results are still subject to potential researcher biases and subjectivity. Future studies could employ a larger research team and utilize intercoder reliability checks to increase the reliability and validity of the findings.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by University of Texas at Arlington, Office of Research Compliance. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

WC: conceptualization, design research, methodology, data collection, data analyses, and writing—original draft preparation, reviewing and editing. WI: conceptualization, design research, and methodology. AP: design research and data collection. H-JW: draft preparation, reviewing, and editing. YR: conceptualization, discussion, and writing—reviewing and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2023.1036770/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^Chi square tests were conducted to determine if the cultures differed in the relative frequencies of respondents who reported (1) both types of incidents, (2) an instant ally incident but not an instant enemy incident, (3) an instant enemy incident but not an instant ally incident, or (4) neither. The results revealed no significance differences between the two different cultures in the frequencies of reports of (1) both types of incidents (χ2 = 1.60, p =.206), (2) an instant ally incident but no instant enemy incident (χ2 = 2.38, p =.123), and (4) neither incidents (χ2 = 3.33, p =.068). However, there was a significant difference in the frequencies of reports of (3) an instant enemy incident but no instant ally incident (χ2 = 15.39, p < .001). Specifically, the U.S. participants were more likely to report an instant enemy incident only compared to the Taiwanese participants. Because the Taiwanese tend to strive for greater harmony and social cohesiveness in their interactions than Americans do, the Taiwanese respondents might have found it more difficult to know whether a stranger was truly a personal “ally” or was merely someone who was trying to uphold the strongly-prescribed cultural values of harmony and social cohesiveness, which makes it much easier to accept differences (Schug et al., 2009).

2. ^The distinction between an instant enemy and an instant ally was intended to capture the distinction between a person who was immediately perceived to be either an outgroup member or an in group member within the particular culture studied.

3. ^This interpretation is consistent with our observations that the Taiwanese respondents were more likely to mention positive information before making negative statements, and tended to connect them by exclusive words, especially in the Enemy situation.

References

Adams, A., Miles, J., Dunbar, N. E., and Giles, H. (2018). Communication accommodation in text messages: exploring liking, power, and sex as predictors of textisms. J. Soc. Psychol. 158, 474–490. doi: 10.1080/00224545.2017.1421895

Adams, G., and Plaut, V. C. (2003). The cultural grounding of personal relationship: friendship in North American and West African worlds. Pers. Relatsh. 10, 333–347. doi: 10.1111/1475-6811.00053

Amodio, D. M., and Devine, P. G. (2006). Stereotyping and evaluation in implicit race bias: Evidence for independent constructs and unique effects on behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 91, 652–661. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.4.652

Baumeister, R. F., and Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol. Bull. 117, 497–529. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

Branscombe, N. R., and Wann, D. L. (1994). Collective self-esteem consequences of outgroup derogation when a valued social identity is on trial. Europ. J. Social Psychol. 24, 641–657. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2420240603

Brewer, M. (1991). The social self: on being the same and different at the smae time. Soc. Personal. Social Psychol. 17, 475–482. doi: 10.1177/0146167291175001

Bryden, J., Funk, S., and Jansen, V. A. (2013). Word usage mirrors community structure in the online social network Twitter. EPJ Data Sci. 2, 1–9. doi: 10.1140/epjds15

Burgoon, J., Dunbar, N. E., and Giles, H. (2017). “Social signal processing,” in J. K. Burgoon, N. Magnenat-Thalmann, M. Pantic, and A. Vinciarelli, eds Interaction coordination and adaptation (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press), p. 78–96. doi: 10.1017/9781316676202

Byrne, D., Gouaux, C., Griffitt, W., Lamberth, J., Murakawa, N. B. P. M., Prasad, M. M., et al. (1971). The ubiquitous relationship: attitude similarity and attraction: a cross-cultural study. Human Relations, 24, 201–207. doi: 10.1177/001872677102400302

Campbell, N. (2003). Emotional disclosure through writing: an intervention to facilitate adjustment to having a child with autism. Dissert. Abstracts Int. Section B Sci. Eng. 64, 2380. doi: 10.1177/1362361303007001004

Caprariello, P. A., Cuddy, A. J. C., and Fiske, S. T. (2009). Social structure shapes cultural stereotypes and emotions: a causal test of the stereotype content model. Group Process. Intergr. Relat. 12, 147–155. doi: 10.1177/1368430208101053

Chan, D. K. (1994). “Colindex: A refinement of three collectivism measures,” in U. Kim, H. C. Triandis, C. Kagitcibasi, S. Choi, and G. Yoon, eds. Individualism and collectivism: Theory, methods, and applications, 2nd ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications), p. 200–210.

Chiang, Y. S. (2010). Self-interested partner selection can lead to the emergence of fairness. Evolution Human Behav. 31, 265–270. doi: 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2010.03.003

Cikara, M., and Van Bavel, J. J. (2014). The neuroscience of intergroup relations: an integrative review. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 9, 245–274. doi: 10.1177/1745691614527464

Clore, G. L. (1992). “Cognitive phenomenology: Feelings and the construction of judgment,” in L. L. Martin and A. Tesser, eds. The construction of social judgments (Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates), p. 133–164.

Crick, N. R., and Bigbee, M. A. (1998). Relational and overt forms of peer victimization: a multi-informant approach. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol., 66, 337–347. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.66.2.337

Downey, G., and Feldman, S. I. (1996). “Implications of rejection sensitivity for intimate relationships.” J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 70, 1327–1343. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.70.6.1327

Dragojevic, M., Gasiorek, J., and Giles, H. (2016). “Accommodative strategies as core of CAT,” in H. Giles, ed. Communication accommodation theory: Negotiating personal and social identities across contexts (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press), p. 36–59. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781316226537.003

Drivonikou, G. V., Kay, P., Regier, T., Ivry, R. B., Gilbert, A. L., Franklin, A., et al. (2007). Further evidence that Whorfian effects are stronger in the right visual field than the left. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA., 104, 1097–1102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610132104

Ekman, P. (1997). Should we call it expression or communication?. Innovation 10, 333–344. doi: 10.1080/13511610.1997.9968538

Elsevier, B. (1998). “Don't take my word for it.”—understanding Chinese speaking practices. Int. J. Intercultural Relat. 22, 163–186. doi: 10.1016/S0147-1767(98)00003-0

Ethier, K. A., and Deaux, K. (1994). Negotiating social identity when contexts change: maintaining identification and responding to threat. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 67, 243–251. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.67.2.243

Everett, C. (2013). Linguistic Relativity: Evidence Across Languages and Cognitive Domains. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. doi: 10.1515/9783110308143

Fiske, S. T., and Neuberg, S. L. (1990). “A continuum model of impression formation, from category-based to individuating processes: influence of information and motivation on attention and interpretation,” in M. P. Zanna, ed., Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (New York, NY: Academic Press), p. 1–74. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60317-2

Freeman, N. H., and Habermann, G. M. (1996). “Linguistic socialization: a Chinese perspective,” in M. H. Bond, ed. Handbook of Chinese Psychology (Oxford: Oxford, England: Oxford University Press), p. 79–92.

Gallois, C., Giles, H., Jones, E., Cargile, A. C., and Ota, H. (1995). “Accommodating intercultural encounters: elaborations and extensions,” in R. L. Wiseman, ed. Intercultural Communication Theory. (Thousand Oaks, CA, US: Sage), p. 115–147.

Gallois, C., Ogay, T., and Giles, H. (2005). “Communication accommodation theory: A look back and a look ahead,” in W. Gudykunst, ed. Theorizing About Intercultural Communication (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), p. 121–148. doi: 10.1177/1057567707310554

Giles, H. (1979). “Ethnicity markers in speech,” in Scherer, K. R., and Giles, H., eds Social Markers in Speech. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), p. 251–289.

Giles, H., and Ogay, T. (2006). Communication accommodation theory. In B. Whaley an W. Samter (Eds.), Explaining communication: Contemporary theories and exemplars (pp. 293–310). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Giles, H., and Watson, B. (2008). “Intercultural and intergroup communication,” in W. Donsbach, ed. International Encyclopedia of Communication (Oxford: Blackwell), p. 2337–2348. doi: 10.1002/9781405186407.wbieci049

Gudykunst, W. B. (2001). Asian American ethnicity and communication. Choice Rev. Online 38, 38–5868. doi: 10.4135/9781452220499

Gudykunst, W. B., Matsumoto, Y., Ting-Toomey, S., Nishida, T., Kim, K., Heyman, S., et al. (1996). The influence of cultural Individualism-Collectivism, self Construals, and individual values on communication styles across cultures. Hum. Commun. Res. 22, 510–543. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2958.1996.tb00377.x

Gullekson, N. L., and Vancouver, J. B. (2010). To conform or not to conform? An examination of perceived emotional display rule norms among international sojourners. Int. J. Intercultural Relat. 34, 315–325. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2009.05.002

Heine, S. J., and Lehman, D. R. (1997). The cultural construction of self-enhancement: an examination of group-serving biases. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 72, 1268–1283. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.72.6.1268

Heise, D. R. (2014). Cultural variations in sentiments. Springerplus 3, 170. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-3-170

Hewstone, M., Rubin, M., and Willis, H. (2002). Intergroup bias. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 53, 575–604. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135109

Hofstede, G. (1991). Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind-Intercultural Cooperation and its Importance for Survival. London: McGraw-Hill.

Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing cultures: the hofstede model in context. Online Read. Psychol. Cult. 2, 2307–0919. doi: 10.9707/2307-0919.1014

Huang, J., Xu, D., Peterson, B. S., Hu, J., Cao, L., Wei, N., et al. (2015). Affective reactions differ between Chinese and American healthy young adults: a cross-cultural study using the international affective picture system. BMC Psychiatry 15, 1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0442-9

Hui, C. H. (1988). Measurement of individualism-collectivism. J. Res. Pers. 22, 17–36. doi: 10.1016/0092-6566(88)90022-0

Iwasaki, S., and Horie, P. I. (2000). Creating speech register in thai conversation. Language Society 29, 519–554. doi: 10.1017/S0047404500004024