- 1Discipline of Sociology and Criminology, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 2Royal United Services Institute, London, United Kingdom

This article presents and discusses data from two research methods on journalism in Afghanistan before the Taliban takeover of power in August 2021. News reports from the time of the intra-Afghan peace talks in September 2020 were analyzed using the Peace Journalism model. These were found to be predominantly War Journalism, leaving audiences cognitively primed for violent conflict responses and likely to overlook or fail to value peace initiatives. Interviews with 16 Afghan journalists revealed this pattern to be at odds with their aspirations and role perceptions. They wanted to report more in the style of Peace Journalism: revealing backgrounds and contexts; highlighting successes and achievements; giving a voice to all rival parties, and covering peace initiatives from whatever level. The constraints they identified, as impeding their preferred reporting approaches, were categorized using Reese and Shoemaker's Hierarchy of Influences model. Some were attributed to the commercial competitive market structure of Afghan media under the internationally supported government, after an initial infusion of development aid was reduced. In any such intervention in future, it is argued, news can play a positive role in building a constituency for peace—but only if aid interventions ensure that media are not left to operate on a purely commercial basis.

Introduction and research questions

Data from field experiments has shown that people are influenced in their responses to conflict by the ways in which it is represented in media reporting. These are codified in the Peace Journalism model, which provides a set of headings under which ideational distinctions in the news framing of conflicts can be identified and contrasted. Audiences exposed to Peace Journalism have been found more likely to “consider and value nonviolent responses to conflict” (Lynch, 2014) and inclined to form “less polarized mental models” of a conflict (Kempf, 2007). They are less likely to favor military measures (Schaefer, 2006). While no audience research was conducted for the present study, therefore, we can infer, from these previous studies, the likely interactions between patterns of coverage detected in our content analysis of Afghan media in particular, and the responses of news audiences who read, watched and listened to it.

Prospects for peacemaking and peacebuilding depend on success in forming a “constituency for peace” (Stanton and Kelly, 2015, p. 34) at all levels of society. Leaders involved in fashioning, proposing and discussing peace initiatives and agreements stand to benefit, therefore, from being able to engage with media (and, through them, the wider public) when represented in the form of Peace Journalism (PJ). On the other hand, their efforts may be impeded, or outright thwarted, if represented through War Journalism, since this is unlikely to prompt or enable public support for their aims. The latter form is commonly identified, in relevant scholarship, as dominant in most media, most of the time; though studies in content analysis have also found varying proportions of Peace Journalism (Lee and Maslog, 2005; Ross and Tehranian, 2008; Lynch, 2014).

Furthermore, the chief influences on news content are generally identified as stemming from the structures of media industries in which journalists are employed to gather, report and disseminate news (Galtung and Ruge, 1965; Bennett, 1990). The overarching purpose of the present research is to determine what contribution, if any, the reporting of conflict issues by Afghan news journalism was likely to have made to the formation of a constituency for peace, by the time of the peace talks; to identify influences on news content in the form of constraints on and affordances for the work of journalists—and to consider implications of these results for the design of media sector structures in conflict-affected societies in any future intervention.

In pursuit of this overarching purpose, two Research Questions were addressed:

1. In content analysis, what elements of War Journalism and Peace Journalism, respectively, were evident in the work of Afghan journalists when they reported on conflict issues in Afghan media at the time of the peace talks?

2. In interviews with these journalists, how far did the pattern of coverage so revealed match their own aspirations and role perceptions, based on their own beliefs as to how they should be reporting? To the extent that these diverged, what kinds of constraints did they identify, preventing them from reporting as they would wish to?

RQ1: Content analysis

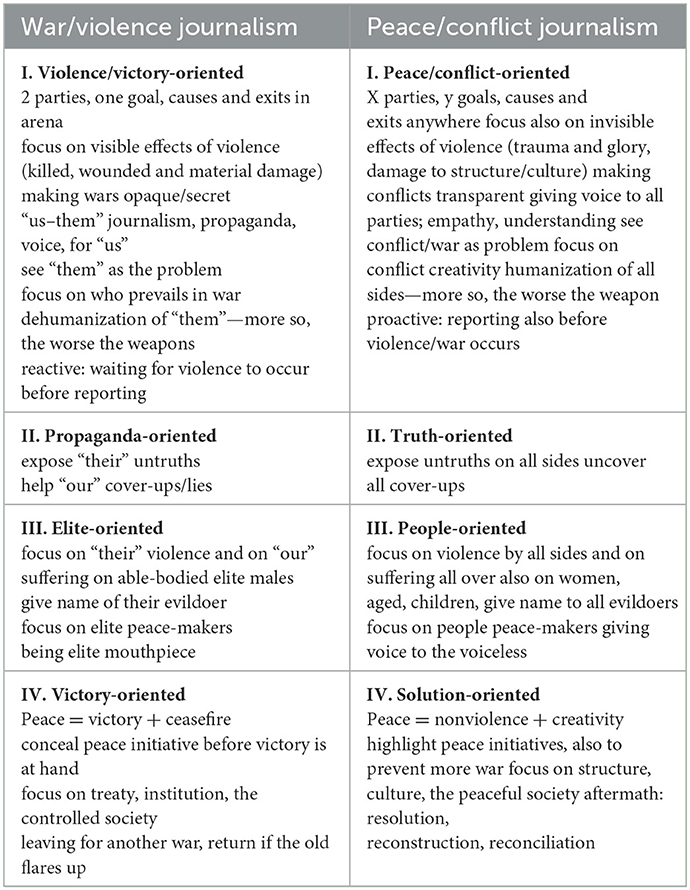

The content analysis of news reporting was carried out using evaluative criteria derived from distinctions in the Peace Journalism model devised by Johan Galtung, which takes the form of a table setting out a series of dyads (Table 1). Whereas the mainstream of news reporting about conflicts is:

• Violence-oriented;

• Propaganda-oriented;

• Elite-oriented, and

• Victory-oriented.

So PJ adopts the opposite of each of these, being, instead:

• Peace and conflict-oriented;

• Truth-oriented;

• People-oriented, and

• Solution-oriented (Lynch and Galtung, 2010, p. 13).

To elaborate on these: in a war and violence-orientation, conflict is represented as a zero-sum game, where two antagonistic parties contest the single goal of victory (which, for the other, means inevitable defeat). Causes of—and possible exits from—the conflict are confined to the immediate arena of hostilities. Whereas a peace and conflict-orientation means going beyond the familiar tit-for-tat sequence of direct violence, instead allowing for multiple parties and goals, with causes and exits anywhere in time and/or space.

In practical terms, by reporting only violent incidents, or ritualized denunciations of the “enemy” by leaders on either of two “sides”, War Journalism typically omits the goals of the parties, or the issues (of grievance, relative deprivation, injustice, unmet needs and interests) that lead them to engage in the conflict, including through violence, in the first place. Generally, their reasons for acting as they do remain obscure. If they appear to act without reasons, they can seem unreasonable, so there is no point reasoning (negotiating) with them. This can render news audiences cognitively primed for violent responses. “By focusing on physical violence divorced from context, and on win–lose scenarios... news unwittingly incentivizes conflict escalation and ‘crackdowns”' (Hackett, 2011, p. 40).

Truth-orientation may refer to the familiar duty of public service media to accurate reporting. At any rate, it indicates, in the specific context of reporting conflict, the inclusion and/or juxtaposition of material calculated or likely to activate critical thinking by audiences served up with propaganda, or partial, self-serving claims and statements, by one or more parties.

A people-orientation is often fulfilled by featuring the efforts at conflict resolution, bridge-building and peaceful coexistence by actors and institutions at sub-elite levels. Conflict coverage can be seen, finally, as solution-oriented if causes are explained, and problems diagnosed, in terms of intelligible sequences of stimulus and response. If audiences can see how the processes of a conflict lead up to the events—including violent events—that dominate the news, they are more likely to be receptive to treatment recommendations in the shape of proposals for nonviolent policy responses, which can be seen as peace initiatives. Table 1 sets out Galtung's original Peace Journalism model (Lynch and Galtung, 2010, p. 13).

This model is typically operationalised in relevant research by treating these orientations as a set of headings, and allotting particular dyadic distinctions of representation, in samples of news reporting about particular conflicts, under each heading (Lynch, 2014). This process is guided both by the subsidiary characteristics named by Galtung, in the boxes of the table, and by attention to the conflict milieu—considered with reference to established precepts of conflict analysis—to pinpoint the differentials of newsgathering and story-telling that are likely to produce the strongest interactions in audience meaning-making.

As Nohrstedt and Ottosen (2011, p. 224–225) point out, “journalistic products are perceived to carry and contain meanings on several levels. These cannot be collapsed into a single ‘manifest content' level”. In all studies where the PJ model is used as the basis for deriving evaluative criteria to use in content analysis, therefore, some further allowance is made for the discursive context into which the sample of reporting would have entered, and how the distinctions “caught” by such criteria would be likely to influence audience responses.

The Afghan context

The Afghan context of 2020 had been forming since a US-led military operation overthrew the Taliban regime and installed a new government backed by a coalition of intervening countries, who committed themselves to the country's reconstruction through the 2001 Bonn Agreement. Opposition to the new dispensation coalesced around conservative clerics and ousted former Taliban officials, who made common cause with jihadist groups. Strong Tajik and Hazara representation in the new central government led some Pashtun officials to support this opposition. The “cause” drew in battle-hardened jihadists with experience of resisting Russian forces in Chechnya and, a little later, US forces in Iraq. Nato and allied countries deployed militarily to fight the insurgents.

At community level, meanwhile, underlying factors fuelled the insurgency from below. Continuing armed Western intervention alienated Afghan regional actors. The Taliban recruited among “underemployed young men with frustrated aspirations and a limited stake in society” (Ladbury, 2009, p. 2). Policies pursued by international forces, such as destroying opium crops, closed down sources of livelihood. State functions performed by branches of the internationally supported government—including everyday transactions with local officials and law courts—rapidly became a byword for corruption, further alienating communities, and leading some to express a preference for Taliban rule (Nelson, 2010).

Such grievances, when compounded by a lack of perceived “political efficacy”—that is, expectation that competent authorities can and will respond effectively to them—have been identified as a combination predicating individual support for political violence (Dyrstad and Hillesund, 2020). By 2009, Susanne Schmeidl, who interviewed civilians in Uruzgan province for a report commissioned by the Australian government (which had deployed its troops there as part of the International Security Assistance Force) found them to be united in demanding an end to US bombing of their homes and villages. Many complained that their own government was not “competent or responsive”. One informant, a tailor from Zabul, complained: “The Americans are ruling us in our homeland and the government is not capable to prevent wars and bombardments. If they cannot stop Americans from bombing us, how can they help us?” (Schmeidl, 2009).

At the same time, life under the internationally supported authorities brought significant benefits for some Afghans. The presidential government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan operated a strong human rights framework. A Bill of Rights was written into the country's 2004 constitution, protecting freedoms of conscience, expression and association. As time went on, these were honored in the breach as much as the observance. Toward the end of the period, in particular, monitoring groups raised the alarm over the deteriorating human rights situation. A 2018 report from Amnesty International noted:

“Human rights defenders faced constant threats to their life and security… Women human rights defenders continued to face threats and intimidation by both state and non-state actors across Afghanistan. Most cases were not reported to police because of lack of trust in the security agencies, which consistently failed to investigate and address these threats… A string of violent attacks and intimidation against journalists, including killings, further underlined the steady erosion of freedom of expression. Media freedom watchdog Nai reported more than 150 attacks against journalists, media workers and media offices during the year. These included killings, beatings, detention, arson, attacks, threats and other forms of violence by both state and non-state actors”.1

From the present perspective, however, it can be gauged, in retrospect, how much media freedom and civil society space was still provided for, through updated reports showing how far they have been dismantled under the newly restored Taliban rule. Reporters Without Borders found that Afghanistan lost 40% of its media outlets and 60% of journalism jobs within months of the takeover in August 2021. “Media and journalists are being subjected to iniquitous regulations that restrict media freedom and open the way to repression and persecution”, RSF concluded.2

Occasional indications emerged of a potential constituency for peace in the country, if only it could be mobilized. An opinion poll conducted by the International Republican Institute in 2009 indicated that fully 68% of respondents wanted the government to reconcile with the Taliban; only 14% did not (quoted in Lynch and Galtung, 2010, p. 141). Only 10 years later were concrete proposals for peace negotiations made, however—at the instigation of the Trump administration, which was seeking an exit from Afghanistan for the few thousand remaining US troops. These antecedents thus feed into our evaluative criteria for analyzing the representation of the conflict in the sample of news, at the point in September 2020 when talks involving both government and Taliban representatives finally got underway.

One of the first studies of this kind, using Galtung's model in content analysis, remarks that “peace journalism is supported by framing theory” (Lee and Maslog, 2005, p. 311). In a landmark study of frames in journalism, Entman (1993) identifies the link between, on the one hand, “moral evaluation, causal explanation, and problem definition” and, on the other, “treatment recommendation” for the conflict being represented.

Afghan journalism would have needed to use its relatively high degree of notional freedom under the internationally supported government, to expose and ventilate some of the issues identified in this brief discussion—manifest in unmet needs and unaddressed grievances at community level—for any credibility to attach to a peace agreement as a “treatment recommendation”. It would have had to look beyond merely blaming one or other “side” for the causes of conflict and the problems arising from it, if audience interest were to be engaged in any response other than further armed interdiction to “destroy the enemy” (Johnson, 2010).

Peace was now under discussion at elite levels—which could be expected, given widespread reporting conventions, to be reflected in news. However, since success in such endeavors depends on creating a “constituency for peace” at all levels of society, it would have been important to supplement prominent official and leadership sources with others from sub-elite levels, able to speak from their own experience of living with the conflict, its exigencies, and possible ways forward. This would have enabled peace to make sense, as it were, as a way of solving problems manifest in everyday life.

Results and discussion

Based on the foregoing discussion, evaluative criteria were developed, based on the distinctions in the PJ model. These were used to analyse 132 articles drawn from the BBC Monitoring service, which produced English translations from a wide range of Afghan media outlets (working in original languages of Pashto and Dari), covering a period from September 5–17, 2020: a week leading up to the talks, and the week of the first (and, it turned out, only) meeting, in the Qatari capital, Doha.

The sample comprised all of BBC Monitoring's output that referenced the conflict and/or the peace talks in this period. Media included both print and broadcast sources, with stories from those seen as both sympathetic to the government, and oppositional. The number of articles drawn from each source was as follows:

• Tolo (privately owned TV station) 32.

• Afghan Islamic Press news agency 25.

• Afghanistan Channel 1 (government-run TV station) 16.

• Hasht-e-Sobh newspaper 10.

• Ariana (privately owned TV station) 9.

• Etilaat-e-Roz newspaper 8.

• Hewad newspaper 7.

• Daily Afghanistan newspaper 7.

• Maseer newspaper 6.

• Arman-e-Melli newspaper 3.

• Weesa newspaper 2.

• Shamshad (privately owned TV station) 2.

• Arzu (privately owned TV station) 2.

• Voice of Jihad 1.

• National Afghanistan TV (government-run TV station) 1.

• Office of the President (government information service) 1.

Rather than seek to connect characteristics of the content of reporting offered by each of these media individually, with its ownership and/or political or other affiliation, we took the sampling by BBC Monitoring as representative of Afghan media in the round. This was justified because we were seeking to establish patterns of reporting in general, rather than to detect distinctions between different media outlets.

Evaluative criteria

• The first evaluative criterion was whether an article mentioned any of the underlying issues in the conflict, referred to in the Galtung model as “causes”. By exploring such issues—including those outlined in the previous section—the conflict is made “transparent”, enabling “empathy [and] understanding”, and thus the “humanization of all sides”. A direct implication of this for the present study is the inclusion of material revealing the reasons why some people supported the Taliban, while others supported the internationally-backed government. This would see the article rated as conflict-oriented. If, on the other hand, such material was excluded, then—as argued above—the only treatment recommendation that would apparently have “made sense” would be further violence, or a “focus on who prevails in war”.

• A second criterion, corresponding to the second headline distinction in the table, would earn the article a classification as truth-oriented by the occurrence of material to enable and prompt audiences to reflect critically on claims made by all sides in the conflict. This would have to apply equally to those from the government and its allies as to those from the Taliban, since the requirement is to expose “all untruths and cover-ups”.

• Two further criteria were adopted to reflect the distinction in the Galtung table between elite and people peace-makers. Afghan media in this period had reached the stage when waiting for leaders to discuss, or at least mention peace, was over. So an article was classified as peace-oriented if it referred to the peace talks in the offing (or actually underway, by the time of the later articles in the sample)—commonly, it could be expected, by quoting or alluding to elite sources.

• It could “score” a further point, as being people-oriented, for the addition of material pertaining to, or perspectives from, non-elite sources—including attempts at coping with issues and grievances in communities; statements of goodwill or good intent across divides, and so forth. This was interpreted generously, to “catch” any trace of awareness, or reminder to audiences, that a broad-based peace constituency would be required, in order for peace to succeed on any sustained basis. So, for instance, the relatively rare occasions when the voices of men and women in the street appeared, in vox populi format, were counted.

• The final criterion corresponded to the solution-orientation of Peace Journalism, which would be satisfied by any mention, in the article in question, of what peace would look like. This would include references to the kind of political, social and/or economic arrangements that could be provided for in an agreement; how feasible such arrangements could be, and how they might correspond with the issues identified as bearing upon the lived experience of people at all levels from the unresolved conflict.

Table 2 sets out the results in summary form.

The articles were coded by the two researchers independently, with >90% score for inter-coder reproducibility in the initial analysis. Any disagreements would be reconciled by consensus. With 132 articles in the sample, and five criteria, the total of points available was 660. The “score” of Afghan media in this period, of 164, gives an overall PJ quotient of 25%. Is this high or low? An apt comparison comes from Lee and Maslog's (2005) study, quoted above, which carried out a similar evaluation of ten Asian newspapers. Sample material was drawn from a phase of conflict in two of the study countries, Sri Lanka and the Philippines, when—as here in Afghanistan—the government in each case was actively engaged in peace talks (with the Tamil Tigers, and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front, respectively). This was reflected in high ratings: the equivalent PJ quotient for Sri Lanka's Daily News & Sunday Observer and Daily Mirror was 58%; and, for the Philippine Daily Inquirer and Philippine Star, 52.5%.

So the Afghan media in this period exhibited relatively little PJ content. Moreover, the modal average score for the articles was 1 (with 62), reflecting, in the vast majority of cases, a glancing reference to the peace talks or plain factual account of their occurrence, with no other qualifying material. Hence the relatively high score for the third criterion, relative to the others.

In the category with the second-highest rating, conflict-orientation, a significant number of the qualifying articles mentioned the disagreement between the two sides in the negotiation over the system of government Afghanistan should have: either an Islamic republic, as under the present authorities, or an Islamic Emirate, as reportedly favored by the Taliban. A point was awarded for articles that elaborated on this distinction to specify the practical differences this would make: with democracy, human rights and the rule of law (including media freedom) under a republic, while all these could be ended or significantly downgraded under an Emirate, being an authoritarian system.

There were a few articles that scored highly, including two that achieved a full five points. These higher scores were gained through diverse sourcing, enabling a fuller suite of relevant issues to be explored. In one of these cases, a report from September 14 on the privately owned Tolo TV station (translated in BBC Monitoring under the heading “No-one should doubt government's sincerity in intra-Afghan talks—spokesman”) reported details of a study raising concerns over women's rights as an issue in the peace talks, needing to be reflected in any agreement. It interviewed a representative of the Taliban, as well as the government, and speakers from two political parties, along with several members of the public. The juxtaposition of these elements was used to enable audiences to think critically about the statements, particularly from the Taliban (by comparing their actual record in office before 2001).

However, in many other articles, the journalists found the parties apparently unresponsive. Many reported that the Taliban had been approached for a statement but had not commented on a particular development—whether an issue pertaining to the talks, or a violent incident. And more than one lamented the paucity of information made available to media attempting to cover the negotiations themselves, once they got underway in Doha. In a column published on September 16 (translated in BBC Monitoring under the heading, “Afghan daily says urgently mobilize support for negotiating team”), a privately owned newspaper, the Daily Afghanistan, seemed to endorse the view put forward above, that media have a potentially important role to play in enabling a peace constituency as an indispensable component of successful conflict resolution:

“The third shortcoming of the government… is the lack of a strong and efficient media strategy on the peace process. We are at a stage where mobilizing public opinion in favor of the republic and the achievements of the last two decades, and in supporting the negotiating team are extremely important. Today, however, we do not have such a strategy”.

The same newspaper featured the sole example in the data set to discuss the problems of corruption and cronyism besetting the Afghan government, which fed into support for the Taliban. An editorial by Mohammad Hedayat, published in English by BBC Monitoring on September 17 under the heading, “Afghan daily says corruption will plague new ministers”, referred to a “mafia culture of deals, getting votes in return for money”. “Key institutions and departments” were run in a “mafia and shareholder atmosphere”, he continued. So preoccupied were office-holders with arranging payback to their political supporters, that “expectation of any success and efficiency from these important central institutions will continue to be futile”.

Afghan media development

Support to the media sector was a major part of development funding to Afghanistan following the fall of the Taliban regime in 2001. By 2015, when the Obama Administration declared the US combat mission in the country to be over, “more than a hundred million dollars of Western government funding had been invested in development of liberal democratic journalism” (Relly and Zanger, 2017, p. 1,233). This was spent partly on training programs for journalists, with the Internews media development agency estimating that it had trained up to 30,000 Afghan editors and reporters—as well as direct subsidy to community media.

Internews itself had won USD$4m in funding from USAID to establish and support a network of 32 regional radio stations, and to provide them with a satellite uplink to use in broadcasting. With Afghan journalists in the network, it developed a national program, Salaam Watander (“Hello Homeland”), which ran for 4 h per day on each of these stations (DT, 2007). As nearly 90% of Afghan households possess a radio receiver, this was seen as a good way to reach a large audience. Content for Salaam Watander was devised to “aid development and reconciliation”. There was “diverse programming on issues such as maternal health, agricultural education, national and international news, and radio soap operas which use entertaining formats to educate families on subjects such as health and rule of law”. In listener participation segments, Salaam Watander “allowed a public, open forum of debate on current politics, something that had never existed before in Afghanistan”—fostering, perhaps, a generalized sense of political efficacy and responsiveness.

By 2005, however, funding had already begun to diminish. Internews switched focus to providing assistance to the stations to raise their own funds by selling on-air advertising, as direct funding for program content (and paid-for public service announcements by international agencies) dwindled. A business development module, introduced that year, was aimed at supporting radio stations to “design business models for the stations and to set up rate cards for advertisers to begin purchasing advertising spots”. Gone were the themes of reconciliation and development, to be replaced by entertainment, and news that was increasingly drawn to dramatic and sensational coverage, as cheap ways to attract audiences in what was now a media market dominated by competition between commercial operators.

The ostensibly independent media that survived in this competitive environment were subject to various forms of “capture” (Relly and Zanger, 2017), either consciously by political and/or violent actors operating behind the scenes, or indirectly through constraints on their ability to gather news, for instance when officials, under no direction to engage with them, failed or refused to share information with journalists. When international funding for media development dried up, it no doubt helped to balance aid budgets—but the $100 million or so that was thus saved was a drop in the ocean compared with the overall cost of the Afghan war, conservatively estimated by researchers at the Brown University Costs of War Project at over USD$2 trillion to the US alone (Brown University Costs of War Project, 2022).

The form of media development that prevailed in Afghanistan—by default, as purposive interventions petered out—exemplified a “modernization approach”, in which “the expansion of privately held technological resources for communication is seen as a key to raising the level of both prosperity and democracy in recipient countries” (Lynch, 2008, p. 293). To make this suitable for countries affected by violent conflict, Thompson and Price advocate “peace broadcasting”, but add that this “ideally consists of professional, pluralist journalism [rather than] pressures to highlight [certain] kinds of information” (Thompson and Price, 2002, p. 18).

However, the distinctively commercial, competitive media structure to which the modernizing approach typically gives rise (and did, albeit with some local variations, in Afghanistan) is also, in general, a structure that produces dominant patterns of War Journalism. It leads to sensationalized reporting and the highlighting of sudden, usually negative events in a conflict, at the expense of process, contexts and backgrounds. At issue in the present study is whether media development in situations of conflict requires more sustained, purposive direction, to enable different modes of reporting—perhaps by underwriting different, non-commercial structures—if it is to contribute to constituencies for peace.

RQ2: Journalist interviews

How far did the pattern of coverage revealed by the content analysis match the aspirations and role perceptions of Afghan journalists, based on their own beliefs as to how they should be reporting? To the extent that these diverged, what kinds of constraints did they identify, preventing them from reporting as they would wish to?

To explore these issues, semi-structured interviews were conducted with 16 Afghan journalists between the end of 2020 and May 2021, in English, Dari and Pashto3 (with material in the latter two languages being translated to English for analysis). This method allows for initial lines of inquiry to be set according to the research design, but to permit some sharing of the agenda with interviewees, since follow-up questions can respond to information they divulge. Their own experiences and perspectives can therefore be elicited through the interview process. The sample included both former journalists now working for media-related NGOs, and serving journalists. The latter included one owner, four editors and five reporters working in radio and TV, all but one interviewee working for privately-owned stations. Of the 16, two were women and four were based outside Kabul.

In each interview, the subject was first asked to outline their ideal-typical view of how Afghan media should report on the situation and the conflict around them, given an “open book” of options from which to choose. In every case, the ideal differed, in the respondent's own assessment, from the actual reality of the reporting that did take place—often to a significant extent.

They were then asked to specify the reasons for this divergence, between the ideal and the real—what was stopping them, and what was stopping journalists in general, from reporting in the ways they would like to. In this, the method adopted followed that of Pedelty (1995), in a pathbreaking ethnographic study of correspondents, for both local and international media, reporting from El Salvador in the 1980s.

Supplementary questions in each of these main categories took the form of prompts to explain further the points made in response to the initial questions, so they differed according to the nature and content of the previous answers. Themes were developed from answers to the two common, starting-point questions, guided by the need to gather insider perspectives on the patterns of representation detected in the content analysis, understanding how and why they arose. So, comments by interviewees were treated as revealing layers of explanation, and subjected to Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (Smith and Maria Jarman, 1999).

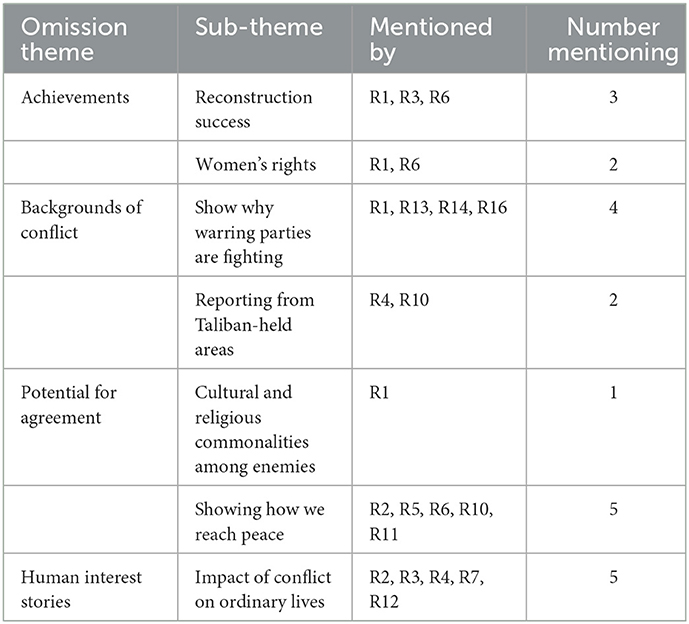

In analyzing the interview transcripts, themes were heuristically allotted under either one of two main headings, “sins of omission” and “sins of commission”. The former denoted things media were failing to do, which the interviewee felt they should, or should do more; the latter, things they were doing, or doing to excess, where the interviewee's opinion was that a reduction or outright cessation of these aspects of coverage would constitute an improvement. The third theme was the range of constraints identified by interviewees, preventing them from remedying these “sins” in their own journalistic work.

Sub-themes emerged from a study of the data, whereby particular aspects of omission and commission, and particular sources of constraining influence, were mentioned. The interviews were thus analyzed with due attention to grounded theory, adopting (Strauss and Corbin's, 1998) three-pronged approach in which micro-analysis of the responses was based on themes identified in prior layers of coding, to produce an axial schema. In the examples given below, respondents were anonymized (as R1, R2 etc) with sufficient detail given about their journalistic role to enable appreciation of their position in the overall structure of Afghan media.

Results from journalist interviews

Sins of omission themes

Themes allotted under the “sins of omission” heading were the failure by media to report, or to accord due weight in their reporting to:

• Achievements made in Afghanistan since western-backed governments first assumed office in 2001;

• Backgrounds and contexts of conflict;

• Potential for agreement in peace talks;

• Human interest stories, showing the reality of conflict as experienced in communities.

Sub-themes

R1, a former journalist now working at an NGO, wanted to see more “solution-based journalism” from Afghan media. “They should go back a little bit to its roots”, he went on (meaning the roots, or underlying causes, of the conflict). “What was the cause of that, how it can be prevented?”

Afghan media devoted too little attention to “positive reports”, R1 continued. Instead, they should give more coverage to “What has been achieved, what has been constructed in Afghanistan on construction projects, about women's rights, the gains which have been made over the past 20 years so that they can build a little bit, they can raise the hope of the people about the future”. Later, R1 called for media to take “a conflict resolution approach... [featuring] systematic discussions on TV channels and also on radios, so that it should give the people some kind of hope and also to share the information about the cultural commonalities, religious and also coexistence, and also how it's possible to remove the differences” between the warring parties.

R2, Head of News at a TV channel, wished to see more “human interest stories” to show how the years of conflict impacted ordinary Afghans. This included people in Taliban-controlled areas, who “should be able to see themselves” when watching news. Media needed to provide “peace education... [showing] how we get to peace”, and offer “bridging” between warring parties. R3, a radio journalist, called for a “focus on the bright spots” where people had succeeded in building peace at a local level—a form of coverage that would entail “giving people a voice”.

R4, an experienced film-maker who took a senior position with an international broadcast news organization, identified “the humanitarian angle”, showing the impact of conflict “in the villages” (including in “Taliban held areas”), as the main missing element of coverage. R5, who also worked for international media, called for Afghan media “to report in a way that promotes peace, rather than promoting division and tension and conflict”.

R6, a war correspondent for a commercial TV channel, called for more reporting about peace, and more attention to the achievements of Afghan society under internationally supported rule, with particular reference to media freedom and women's rights. R7, Head of News at a different commercial TV channel, wished to see more coverage of the “everyday” reality in “the other Afghanistan”, away from the constant coverage of violent incidents.

R12, a radio news producer and reporter, wished Afghan journalists could carry out more “investigative journalism” to expose more of the effects of conflict on everyday life in rural areas.

Table 3 summarizes the themes and sub-themes under the “sins of omission” heading, along with the interviewees who mentioned each one, and the number who mentioned them.

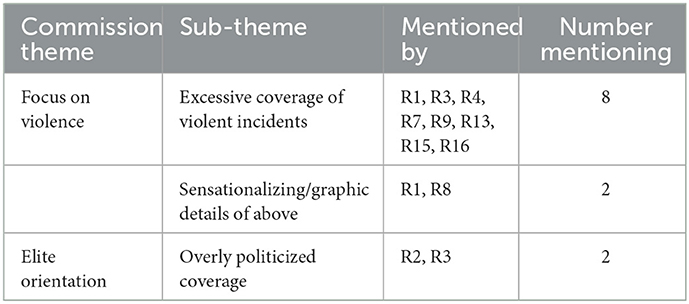

Sins of commission themes

Themes allotted under the “sins of commission” heading were the excessive reporting of:

• Acts of direct violence;

• Casualty figures and “gory details” from the above;

• Overly politicized coverage, including official sources blaming everything on the Taliban.

Sub-themes

R1 identified “endless bloodshed”, from incidents of direct violence, as a dominant theme of existing reporting, which needed to be reduced: “they should avoid showing too much graphic footage of these incidents because it has a very, very negative psychological impact on the people”. Later, R1 clarified that, while violent incidents should be reported, they needed to be supplemented with other aspects: “in a state of five or six reports about the violence, they could at least add one or two more positive reports on their bulletin”, while also offering material to illuminate “why they are fighting”.

R2 reflected that news about the conflict was too “politicized”, relying on elite sources. R3 agreed, observing that, when a violent incident is placed into context, “the focus turns on the political side of peace rather than the social aspect of peace”. R9 said: “sometimes it's hard to take a step back because everything is so immediate”. There was an excessive focus on violence, although R9's own TV station was claimed to be “the first to cover civilian casualties”.

Table 4 summarizes the themes and sub-themes under the ‘sins of commission' heading, along with the interviewees who mentioned each one, and the number who mentioned them.

In sum, then, Afghan journalists wanted to do more in-depth reporting, exploring underlying causes, backgrounds and contexts of conflict, and revealing potential for agreement, notably by reaching out beyond the familiar official sources to engage with the reality on the ground in communities.

They wanted to see less concentration on the daily drumbeat of violent incidents, the graphic details of them and the political “blame game” that would inevitably follow. These preferences correlate directly with the distinctions in the PJ model, used in the content analysis. The latter revealed Afghan media to be practicing War Journalism in dominant mode, whereas the interviewees themselves would all rather have been doing more Peace Journalism: conflict-oriented, people-oriented and solution-oriented.

Influences on news content

The interviewees were all asked to nominate influences on news content to account for the prevalence of aspects of reporting they disliked, and the constraints preventing journalists from doing more of the kind of journalism they would like to see, in ideal circumstances.

Themes that emerged were:

• Competition between commercially funded news organizations leading to prevalent news values of sensation and immediacy, at the expense of reporting backgrounds and contexts;

• Physical danger preventing journalists from doing extensive on-the-ground reporting;

• Failure and/or reluctance by authorities to provide timely, accurate information to journalists;

• A lack of training for Afghan journalists;

• Some media owned by parties to the conflict that did not want peace;

• Partisanship among sources for news.

R1 blamed the “lack of experience and knowledge among reporters”, who found themselves “overwhelmed” by the frequency and severity of violent incidents, and lacked the skills to add backgrounds and contexts. Government sources were interested only in “undermining the Taliban”, rather than giving impartial information. And journalists lacked training to enable them to offer different perspectives.

R3 argued that, while Afghan journalists were well versed in reporting violent incidents, getting information from familiar elite sources, they were in need of further training in order to enable them to develop human interest reporting to add background and context. “If you ask them to go outside and prepare a report, they would find it very difficult to identify a good story just by walking out in the market and looking at things”. Newsrooms lacked “capacity” and “financial support” to do anything other than respond to the “overwhelming” news of violent incidents, R3 went on.

R4 was one of many of the opinion that Afghan journalists were in need of more training, especially in “story-telling”. But media in a competitive information market lacked the capacity to offer it: “when you have a lot of breaking news, that sells. You don't need to make a lot of efforts for storytelling to do other stuff”. R7 blamed the commercial interests of media who had to think of their “customers”. R8 drew attention to the fact that, on one commercial TV channel, “the third headline is always about the owner”.

R9 set the exigencies of journalism in the context of a commercial business environment, in which their own TV station had to work hard to survive: “We do entertainment programs, we do documentaries, we do reality TV, we do sports, and we do news”. The news division was “barely profitable”, having received “some grants” while setting up, but now expected to be “self-sustaining”.

R11 had founded a radio station and, likewise, had to generate commercial income to cover costs: “fund it by my personal budget and do all the affairs independently”. Covering conflict “needs lots of resources”, R11 reflected; if only the station could afford “expert journalists and higher payment” to offer more angles. R12, who called for more investigative journalism, lamented the shortage of resources available to the journalist wishing to do it: “A journalist is given 5,000 Afghanis [equivalent to GBP£50]; with that amount no journalist can cover a good report or go somewhere far to investigate. Journalists need to have access to facilities and expertise to cover quality reports”.

R5's answers opened with a specific complaint that Afghan journalists lacked awareness and competence in “conflict-sensitive reporting”—a deficiency that should be remedied with further training. R10, a radio reporter and presenter, called specifically for training in “peace journalism”. Lack of training, to enable more sophisticated or multi-angled coverage, was, indeed, the factor mentioned as a constraint by more interviewees than any other. International donors had provided training, R9 reflected, but not always of the right kind: “They could have done so much more with that money” if they had, instead, used it as direct subsidy to Afghan media. R14, a television reporter, complained of the “huge financial challenges” which meant journalists lacked the “time and facilities” to peer beyond the daily incidents of violence to reveal underlying causes and the dynamics of cause and effect in lived experience.

These results can be arranged, following the Hierarchy of Influences model put forward by Shoemaker and Reese (1996), on five distinct, if often overlapping levels: (1) personal influences, operating directly on the individual journalist; (2) professional influences (reporting routines and news values); (3) organizational influences (economic imperatives and editorial control); (4) extra-media influences (including threats and intimidation from state and non-state actors); and (5) broader societal influences.

Table 5 combines these levels with sub-themes in the “influences on news content” theme, along with the interviewees who mentioned each one, and the number who mentioned them.

The aspects of coverage deprecated by journalists, as divergent from their ideal image of what they should be doing, were a close match for the dominant trends identified in the content analysis: excessive concentration on violent events; demonization of each “side”; little or no in-depth engagement with the conflict as experienced in communities; tendency to overlook achievements already made under the internationally supported government, and little or no material exploring the prospects for a peace agreement.

Their perceptions of their ideal role as journalists in Afghan society echoed findings by Mitra, who interviewed Afghan photojournalists, finding them motivated by a “wish to depict positive, peaceful Afghanistan… [which] show[ed] concurrence with PJ norms and point[ed] to the opportunities for acceptance of PJ” (Mitra, 2017, p. 23). They were also a close match for those revealed by survey evidence as prevalent in other developing countries, emphasizing “social intervention, national development, and educating people” (Kalyango et al., 2017, p. 576).

Among the chief sources of constraints, attributed by nine respondents with significant influence on news practice and content and their derogation from these ideals, was the commercial and competitive nature of the media industry, which deprived them of the time and resources they needed to report as they would wish to, and mandated a sensationalized, adversarial, event-driven brand of coverage as a cheap way to attract audiences. This was surpassed only by a lack of suitable training (named by 11 respondents), particularly in PJ. The other widely perceived constraint (eight respondents) was the sheer physical danger to journalists as the security situation in the country deteriorated.

Conclusions

This research set out to establish what contribution, if any, the news provided by Afghan media, under the internationally supported political regime that was overthrown in August 2021, could have made to the formation of a constituency for peace in Afghanistan. It did this by analyzing news coverage of conflict, offered by these media, in September 2020, when intra-Afghan peace talks got underway. And it explored the factors influencing the content of such news through semi-structured interviews with 16 Afghan journalists. The journalists were also asked for their assessment of their own reporting and that of Afghan media generally, and to compare it with the kind of reporting they themselves believed should be done.

From the content analysis, it is clear that the mainstream of reporting by Afghan media, up to and during this crucial juncture, was dominated by what can be identified, using the Galtung model, as War Journalism—so-called because it is shown to render audiences “cognitively primed” for further violence. It did little to prompt or enable readers, listeners or viewers to consider and value nonviolent conflict responses, as by then envisaged for the negotiation process.

News reporting at the time of the peace talks generally concentrated on violent incidents; presented polarized and polarizing viewpoints; blamed the Taliban for prolonging the conflict (particularly by continually reporting government demands for a unilateral ceasefire); de-humanized their attitudes and behavior, and minimized the voices and concerns of ordinary Afghans, thereby overlooking issues of unmet needs, grievances, thwarted interests and endangered rights in wider society, as contributory factors in want of creative political solutions.

In interviews, participating journalists generally regarded aspects of War Journalism—such as an excessive concentration on traumatic events, and insufficient attention to backgrounds and contexts—as undesirable and inadequate, diverging from what they considered ideal. The dominant pattern of coverage did not align with their own notions of how the conflict and the issues in the peace negotiations should be reported.

At the same time, Afghan journalists interviewed for this study wanted to do more PJ, defined as “when editors and reporters make choices—of what to report and how to report it—that create opportunities for society at large to consider and value nonviolent responses to conflict” (Lynch et al., 2010, p. 6). This effect on audience meaning-making is supported by data from several fieldwork studies, as discussed earlier.

The results show Afghan journalists did not consider it an option to be neutral toward peace; they presumed journalism to be inherently purposive and involved the responsibility to support nascent peace processes. Yet, they were constrained by the structure of the media industry that emerged after international direct subsidy was removed, subject to a variety of pressures and lacked the capacity—training, skills and resources—to report on the conflict in the way they would ideally have wanted to.

The interviewees believed that journalists were constrained from making such choices by a range of factors, including some that could have been readily targeted by policies of media development aid. Professional training for Afghan journalists, funded by international donors, covered such aspects as “skill building, technical, and other Western-style journalistic values such as accuracy and fairness” (Relly and Zanger, 2017, p. 1,235). To this could have been added training based on the PJ and conflict-sensitive reporting principles that have been successfully implemented through training programs in dozens of countries (Lynch, 2021). Donors could have supported governing authorities to engage with journalists in more systematic and transparent ways. And aid for media to establish themselves and go on to operate on a protected, not-for-profit basis—as in the initial phase of development assistance, under the internationally supported government, after 2001—could have been sustained and spread. Instead, its abrupt curtailment consigned journalists to a struggle for economic survival in a competitive commercial market for information. This ensured the journalism they produced could not make a substantial contribution to a constituency for peace.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the University of Sydney. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Union [Project: STRIVE Afghanistan IFS/2018/397-251]. This publication was produced with the financial support of the European Union. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Tea Hornbak Stigler to this research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^https://www.refworld.org/docid/5a99395da.html

2. ^“Afghanistan has lost almost 60% of its journalists since the fall of Kabul”. Viewed on September 24, 2022 at https://rsf.org/en/afghanistan-has-lost-almost-60-its-journalists-fall-kabul.

3. ^The research obtained approval from the University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee, project number 2020/681. Participants signaled their informed consent by signing an approved consent form.

References

Bennett, W. L. (1990). Towards a theory of press-state relations. J. Communication 40, 103–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1990.tb02265.x

Brown University Costs of War Project (2022). US Costs to Date for the War in Afghanistan. Available online at: https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/figures/2021/human-and-budgetary-costs-date-us-war-afghanistan-2001-2022 (accessed November 20, 2022).

DT (2007). New Media and Development Communication: community radio in Afghanistan. Available online at: http://www.columbia.edu/itc/sipa/nelson/newmediadev/Afghan%20Radio%20Network.html (accessed November 20, 2022).

Dyrstad, K., and Hillesund, S. (2020). Explaining support for political violence: Grievance and perceived opportunity. J Confl. Resol. 64, 1725–1753. doi: 10.1177/0022002720909886

Entman, R. (1993). Framing: towards clarification of a fractured paradigm. J. Commun. 43, 51–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

Galtung, J., and Ruge, M. H. (1965). The Structure of Foreign News: the presentation of the Congo, Cuba and Cyprus crises in four Norwegian newspapers. J. Peace Res. 2, 64–91. doi: 10.1177/002234336500200104

Hackett, R. A. (2011). “New vistas for peace journalism: alternative media and communication rights,” in Expanding Peace Journalism: Comparative and Critical Approaches, eds, I. S. Shaw, J. Lynch, and R. A. Hackett, 33–67. Sydney: Sydney University Press.

Johnson, C. N. (2010). Marines Seek and Destroy Taliban Hold on Afghan Locals”. US Central Command, Dec 3. Available online at: https://www.centcom.mil/MEDIA/NEWS-ARTICLES/News-Article-View/Article/884194/marines-seek-and-destroy-taliban-hold-on-afghan-locals/ (accessed on July 20, 2022).

Kalyango, Y., Folker Hanusch, J. R., Terje Skjerdal, M. S. H., Nurhaya Muchtar, M. S. U., and Levi Zeleza Manda, S. B. K. (2017). Journalists' development role perceptions. Journal. Stud. 18, 576–594. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2016.1254060

Kempf, W. (2007). “Two experiments focusing on de-escalation orientated coverage of post-war conflicts,” in Peace Journalism: The State of the Art, eds W. Kempf and D. Shinar, 136–157. Berlin: regener.

Ladbury, S. (2009). Testing Hypotheses on Radicalisation in Afghanistan, Why do men join the Taliban and Hezb-e Islami? How much do local communities support them? Independent Report for the Department of International Development, Report 14 August. London: Department for International Development.

Lee, S. T., and Maslog, C. C. (2005). War or Peace Journalism in Asian Newspapers. J. Commun. 55, 311–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2005.tb02674.x

Lynch, J. (2008). Modernisation or participatory development: the emerging divide in journalist training for conflict-affected societies. Global Change Peace Secur. 20, 237–242. doi: 10.1080/14781150802390400

Lynch, J. (2021). Study analyses magazine's PJ seminar articles. Peace Journalist 10, 4–5. Available online at: https://www.park.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/peace-journalist-oct-2021.pdf

Lynch, J., McGoldrick, A., and Adnan, I. (2010). “How to improve reporting of the war in Afghanistan: feminize it!” in Afghanistan, War and the Media: Deadlines and Frontlines, eds. J. Mair and R. Keeble. Bury St Edmunds: Arima Publishers.

Lynch, J., and Galtung, J. (2010). Reporting Conflict: New Directions in Peace Journalism. St Lucia: University of Queensland Press.

Mitra, S. (2017). Adoptability and acceptability of peace journalism among Afghan photojournalists: Lessons for peace journalism training in conflict-affected countries. J. Assoc. Journal. Educ. 6, 17-27. doi: 10.1080/17512786.2019.1696697

Nelson, S. S. (2010). “Afghan government enters Marjah to cool reception,” in National Public Radio All Things Considered. Available online at: https://www.npr.org/transcripts/123979363

Nohrstedt, S. A., and Ottosen, R. (2011). “Peace journalism–critical discourse case study: media and the plan for swedish and norwegian defence cooperation,” in Expanding Peace Journalism: Comparative and Critical Approaches, eds. I. S. Shaw, J. Lynch, and R. A. Hackett, 217–238. Sydney: Sydney University Press.

Relly, J.E., and Zanger, M. (2017). The enigma of news media development with multi-pronged ‘capture': The Afghanistan case. Journal. Theor. Criticism Pract. 18, 1233–1255. doi: 10.1177/1464884916670933

Ross, S. D., and Tehranian, M. (2008). Peace Journalism in Times of War. In Peace and Policy, Vol. 13, eds. R. S. Dente and M. Tehranian. Tokyo: Toda Institute for Peace and Policy Research.

Schaefer, C. D. (2006). The effects of escalation-vs. de-escalation-orientated conflict coverage on the evaluation of military measures. Confl. Commun. Online 5, 1–17. Available online at: https://www.cco.regener-online.de/2006_1/pdf_2006-1/schaefer.pdf

Schmeidl, S. (2009). Who guards the guardians? The Protection of Civilians in Afghanistan”. Available online at: https://www.mei.edu/publications/who-guards-guardians-protection-civilians-afghanistan (accessed July 20, 2022).

Smith, J. A., and Maria Jarman, M. O. (1999). Doing Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. In Qualitative Health Psychology, eds.Michael P. Murray and Kerry Chamberlain, 218–240. London: Sage.

Stanton, E., and Kelly, G. (2015). Exploring barriers to constructing locally based peacebuilding theory: the case of Northern Ireland. Int. J. Confl. Engage. Resolut. 1, 33–52. doi: 10.5553/IJCER/221199652015003001002

Strauss, A., and Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of Qualitative Research: Second Edition: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Keywords: Peace Journalism, Afghanistan, media development, conflict, peace

Citation: Lynch J and Freear M (2023) Why intervention in Afghan media failed to provide support for peace talks. Front. Commun. 8:1118776. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2023.1118776

Received: 08 December 2022; Accepted: 26 January 2023;

Published: 15 February 2023.

Edited by:

Tobias Eberwein, Austrian Academy of Sciences (OeAW), AustriaReviewed by:

Richard Lance Keeble, University of Lincoln, United KingdomMetin Ersoy, Eastern Mediterranean University, Türkiye

Copyright © 2023 Lynch and Freear. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jake Lynch,  amFrZS5seW5jaEBzeWRuZXkuZWR1LmF1

amFrZS5seW5jaEBzeWRuZXkuZWR1LmF1

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

‡ORCID: Jake Lynch orcid.org/0000-0002-3959-1974

Jake Lynch

Jake Lynch Matt Freear2†

Matt Freear2†