- School of Journalism and Communication, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

This qualitative phenomenological study explores how private press journalists perceive, narrate and interpret their personal challenges and hardships they faced with the judicial system of Ethiopia. In addition, this study explored lived experiences of the journalists and their effort to fight to get a proper court trial in the country. To explore those challenges, and hardships the study considered a time framework embedded the late Prime Minister of Ethiopia Meles Zenawi's tenure. The study used a theory of Alfred Schutz's “Life World” as a lens to provide a “pure” description of the participants' lived experiences. The theory entails a thorough assessment of the participants' encounters and a focus on their lived experiences concerning lack of freedom of judicial system. The data was obtained through a semi-structured interview, which is widely regarded as the most effective method for gathering information for an Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis study. Interviews with the journalists were conducted and transcribed with the goal of allowing participants to tell their own stories. The interview transcripts were studied one by one, and each transcript was read and reread to uncover themes that were then organized and further investigated. This study discovered that private press journalists undergo a variety of problems, hardships, and sufferings as a result of lack of free judicial system in Ethiopia during Meles Zenawi's nearly quarter-century rule. Thus, we propose that if we want to see true freedom in every dimension, including press freedom, the legal system must be totally free from the grip of political power and cease functioning like a puppet and doing what it is instructed.

1. Introduction

Judicial independence, according to Robert and William (1999), is a promise of democracy that acts as a cornerstone of a free society and the rule of law. It simply means that talking about democracy or rule of law in a society where the population denies judicial freedom is meaningless. Therefore, this article addresses how private press journalists in Ethiopia describe the hurdles they encountered with the judiciary in getting free and fair court trial.

The participants discussed their shared views on judicial independence, noting that the judges assigned to hear their cases were either the ruling Ethiopian peoples' Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) political cadres or the regime loyalists. The participants, in this regard, state unequivocally that all judges were appointed based on their political and ethnic ties to the dictatorship, and that they did not anticipate judicial independence from “political cadres posing as judges.”

The participants revealed the ordeals they went through during their case's judicial processes. The judges appear uninterested in even listening to their argument, regardless of how important the truth and reliability are. This researcher evaluates their depiction of lived experience, which may be utilized to show how courts exercised law throughout the Meles' administration in Ethiopia.

According to Maru (2009), the rule of law refers to a government based on laws rather than personalities. Individuals working for the government are expected to carry out their official tasks and responsibilities in a legal manner. To put it another way, rule of law denotes the dominance of the law.

The descriptions of the research participants show that the courts investigated their cases and rendered judgments without regard, or consideration for the rule of law. According to Maru (2009), who quotes Dicey (1995), the rule of law entails three elements in practice: No one is punishable except for a distinct breach of law established in the ordinary legal manner before the ordinary courts of the land; No one is above the law; and Courts play an important role in protecting individual rights. However, these three crucial aspects were missing from the legal system and court practices when it came to investigating and providing a fair trial to the charges leveled against private press journalists. In contrast to Article 29 of the constitution and its subordinate articles, there were practices of invoking the provisions by the public prosecutor, and judges were appointed with the goal of functioning and implementing the regime's will and wish, regardless of where the truth resides.

2. Literature review

2.1. Philosophical and theoretical framework

The epistemological position of this research study is interpretive philosophy, while the two most notable alternatives of Interpretivism: Phenomenology and Hermeneutics are recommended as research theories to conduct the study's description and interpretation (Collins, 2010).

According to Denscombe (1983), understanding “what some people think and do, what kinds of problems they face, and how they deal with them within a given socio-historical context” (p. 87) is one of Interpretivism's characteristics, and it usually focuses on meaning and may employ multiple methods to reflect different aspects of the issue. This researcher employs the theoretical foundations of Phenomenology, specifically Alfred Schutz's “Life World Theory” in studying the lived experience of private press journalists that of the suffering they face due to the absence of free judicial system during Meles Zenawi's rule of Ethiopia.

Schutz (1967) took the idea of Intersubjectivity, a term originally coined by the philosopher Husserl (1931), to his theory and states that: “Intersubjectivity is the basis for living and sharing the understanding of the life-world with others” (p. 124). For Schutz (1967) intersubjectivity refers to “…person to person social interaction, in our day to day experience as human beings with others connected by actions, influences, ideas, etc., in the course of understanding and being understood by others, in mutual attempts in making sense of the world and others” (p. 125).

According to Schutz (1967), the life-world is where our lived experience is created. It is where the past is deposited, the present emerges, and the future is shaped. As a result, without the life-world, we cannot understand social interaction. Schutz further elaborated his “intersubjectivity” idea in his theory in the following manner:

I assume that all that makes sense to me makes sense to all those with whom I share the life-world. My actions make sense, and I suppose that others are interpreting them meaningfully as well, and I make sense of what others do too. In these reciprocal acts of giving and positing meaning to yourself and others, inter-subjective social life is built. It is also the social life of others (p. 123).

Vargas (2020) also describes Schutz idea of inter-subjectivity by stating that it is the foundation for coexisting with others in particular dimensions of time and space and for imparting to them a grasp of the life-world. When the stock of knowledge is only partially derived from personal experience, intersubjectivity helps us refine it by validating or modifying it to later experiences.

The researcher uses Alfred Schutz's theory, which emphasizes on “how people perceive social phenomena” rather than the European approach, which concentrates on “the core of human experience.” The researcher would be describing what is being experienced, rather than “attempting to unearth the essence of what is meant by the phrase,” according to Schutz's definition of Life-World Phenomenology.

2.2. “Authoritarian rule” and the press

The history of print media in the developed world is investigated because they have always been active agents in political change, economic development, and social formation rather than simply recorders of society (Craig, 2007). In contrast, in emerging countries such as Ethiopia, the media has not had a significant role in bringing about political change, economic progress, or social formation. If look, at least, the past 100 years of government type that Ethiopians have gone through various kinds of political leadership found with a totally different ideological orientation, but with a similar type of ruling system—an authoritarian one.

Emperor Haileselassie ruled Ethiopia under an authoritarian monarchical system of government for more than 44 years (from 1930 to 1974), in which a single man dictatorial power ruled the country with harsh censorship laws for all media outlets (Gasiorowski, 1990). The Emperor, like many authoritarian tyrants throughout history, did not allow free thought or speech.

Bahiru (2002) cites Article 4 of the Emperors' 1955 constitution as evidence of absolute power:

“By virtue of His Imperial Blood, as well as the anointing which he has received, the Emperor's person is sacrosanct, His dignity is inviolable, and His power irrefutable” (p. 13).

This just demonstrates how citizens were not permitted to oppose or denounce the Emperor verbally or in writing. In 1974, the Emperor was deposed from his throne and the monarchy was abolished by a military junta known as the “Derg,” which literally means “committee.” The “Derg” adopted communism as an ideology, declaring Ethiopia a Marxist-Leninist one-party state with itself as the vanguard party in a provisional government (Henze, 1985).

The Derg, led by another dictator, Colonel Mengistu Hailemariam, declared socialist philosophy to be the highest law of the country, and no commercial media was permitted to exist in Ethiopia (Keller, 1985). Some believe that the Derg adapted its philosophy from rival Marxist parties, all of which emerged from the student movement. The Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Party (EPRP), for example, was so committed to civilian government that it waged urban guerrilla war against the military rulers, resulting in anarchy in the years that followed (Marcus and Crummey, 2006). Others, however, disputed this assessment, claiming that when Somalia was at war with Ethiopia, America was unhelpful and that the Derg simply fell into the hands of the Soviet Union (Gebru, 2000).

Whatever the case, the Derg proved to be an authoritarian during its 17 years in power by publicly banning citizens from using all democratic values and assets, including freedom of speech and opinion.

Following the demise of the Derg in May 1991, Meles Zenawi's TPLF, which eventually became the EPRDF, assumed control of the government with a socialist bent. The Front's name, Marxist Lenninist League of Tigray (MLLT), was a clear indication of their leftist political beliefs from the start (Young, 1991; Aregawi, 2009).

In May 1991, the TPLF, which eventually became the EPRDF, assumed control of the government under the socialist leadership of Meles Zenawi. The Front's name, Marxist Lenninist League of Tigray (MLLT), was a clear indication of their leftist political beliefs from the start (Young, 1991).

Bach (2011) conducted a thorough examination of the ruling EPRDF party's political position, concluding that it is “authoritarian.” He says the following in this regard:

Since 1991 and the arrival of the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) into power, the Ethiopian ideologists have maintained revolutionary democracy (abyotawi democracy in Amharic) as their core doctrine. The notion inherited from the struggle (1970s−1980s) aims at legitimizing a political and economic structure which de facto implies the resilience of authoritarianism (p. 643).

That means that, according to Bach's assessment of the EPRDF's philosophy, the term “authoritarianism” might be applied not just to those who have seized power through a military coup or without a democratic election, but also to those who have concealed their power under the appearance of democracy. One method to understand such governments is to look at how they “handle” their country's media and journalists.

Despite his success in delivering economic progress to Ethiopia, many people regard Meles Zenawi as an authoritarian leader who does not respect freedom of expression and thinking (Freedom House, 2012). De Waal (2012) writes the following about Meles and his political ideology in one of his review articles on Meles Zenawi's unfinished Master's thesis, “African Development: Dead Ends and New Beginnings.”

World leaders have lauded Meles' economic achievements without acknowledging their theoretical basis. Human rights organizations have decried his political record as though he were a routine despot with no agenda other than hanging on to power (p. 148).

In a similar vein, Mark Tran wrote an article for The Guardian on August 12, 2012 titled “Ethiopia's renaissance under Meles Zenawi tainted by authoritarianism,” in which he states that while Meles has received praise for his economic record, his regime's intolerance of dissent has drawn criticism from human rights groups and the UN, and raises awkward questions for aid donors. In the following way, Tran (2012) describes how Meles' dictatorship had a negative impact on the country's private press:

… In July, Eskinder Nega, a prominent journalist and blogger, was sentenced to 18 years in prison, and an opposition activist, Andualem Arage, was given a life sentence for breaking anti-terrorism laws. Other journalists have been charged under the same sweeping anti-terrorism law that was introduced in 2009, prompting Navi Pillay, the UN high commissioner of human rights, to say journalists, human rights defenders and critics were facing a “climate of intimidation” in Ethiopia (p. 12).

This study aims to discover from the perspectives of the participants whether Meles' dictatorship was granted constitutional status out of a sincere desire to advance democracy and press freedom in the country or if it was only a publicity act to win over Western countries.

2.3. Overview of absenting judicial independence

The breakdown of separation of powers in Ethiopia is a result of a system in which a political organ with strong ties to the executive is the last judge of the constitutionality of the executive's political acts and one effect of this strategy is that judges are reluctant to make decisions on politically sensitive issues.

Yemane (2011) states that, the rule of law is a must requirement for the protection of individual freedoms and rights, and advancement of limited governance. One of the various means of achieving these ends of the rule of law, according to Yemane, is the principle of separation of powers. “The original theory of separation of powers provides for the division of government powers between the two organs, the legislature and the executive, leaving the judiciary out” (Yemane, 2011, p. 31).

Yemane (2011) states what Montesque confesses with regard to separation of power and the rule of law as follows:

“Liberty is threatened when one branch of the government acquires more than one of the powers of government and all the more so when it acquires all three of the powers; so that in order to have liberty it is necessary that law be made by a legislative body, but administered by a separate executive, and applied by an independent judiciary” (p. 32).

What Montesquieu insisted upon saying is that in order to foster governmental accountability and safeguard citizens' fundamental liberties from the arbitrary whims of the state, it is critical to maintain a clear division of powers between the legislative branch, the executive branch, and the judicial branch.

Darou-Salim (2017) states a couple of problems in the allocation of judicial power in Ethiopia, and one is that the Supreme Court in Ethiopia cannot interpret the constitution. Therefore, the judiciary has limited power in terms of their control over the administration due to a law passed by the Congress to reduce the review decisions of administrative agencies. Due to this constitution, the judiciary in Ethiopia does not have a lot of say in laws that control freedom of the press and free media.

Capitalizing on the weakness of the country's judicial institutions, Ross (2009) on his part states, the Ethiopian government used its advantage to pass a law that is repressive toward the press. According to Ross (2009), the Ethiopian government, for instance, established a mass media law in July 2008 that provided the government the authority to swiftly bring defamation lawsuits and levy severe financial penalties on publishing organizations and journalists who disobeyed government regulations. Additionally, by granting that authority to the minister of information, it allowed the government the ability to quickly deny the registration and licensing of journalists and media organizations (FDRE Constitution, 1995).

Article 43(7) of the same law stipulates that defamation or false accusation against any constitutionally elected official judiciary or executive can be prosecuted. This law, therefore, seals the mouth of journalists when it comes to criticizing government officials (Ross, 2009). The vagueness of the definition of defamation and false accusation gives a lot of freedom to the government to define it as it pleases.

The judiciary in the country does not allow for free review of laws voted by the Congress, giving almost total power to the Congress to act as they please. These practices impede human rights from being respected in the country.

Furthermore In 2009, the Ethiopian Senate passed the anti-terror law Proclamation No. 652/2009, that contains a vague definition of terrorism and allows the government to jail journalists and citizens easily (FDRE Anti-Terrorism Proclamation, 2009). According to Ross (2009) the law does not conform to any international definition of terrorism and violates human rights. A number of journalists were illegitimately jailed under that law. The law was not reviewed by the House of Federation despite the opposition of human rights activists, journalists, and opposition members.

First off, because of a law approved by the House to limit the review judgments of administrative agencies, the judiciary has limited authority in terms of its supervision over the administration (Yemane, 2011). Also, the constitution of Ethiopia does not precisely outline the procedures for reviewing administrative decisions. Yemane (2011) also claims that some provisions in Ethiopia's constitution permit the House of People's Representative to transfer authority from the judiciary to a special ad hoc court or an administrative agency. This constitution limits the judiciary's ability to influence legislation governing press freedom and free speech in Ethiopia.

3. Methodology

The current study used Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) as a methodology as it allows the researcher to “present and write the participants' lived experience as it is; i.e., quotations from participants—how they describe things and how they see the phenomenon they encounter.” According to Creswell (2013), IPA will also assist the researcher in “...focusing on a small number of persons and going deep to develop the detail; and exploring the problem in an open-ended fashion” (p. 138–139).

The study looks at the judicial procedures and examines the problems, hurdles, and sufferings the journalists' faced. Because IPA employs both phenomenology and hermeneutic interpretation, the researcher formulates both positive and negative questions about their lived experience. To clear the ethical dilemma of the current study the researcher obtained oral consent of each participants and the name of the participants were used anonymously.

According to Alase (2017), “IPA is being used as a methodological approach in many qualitative research studies as it helps to investigate and interpret the ‘lived experiences' of people who have experienced similar (common) phenomena,” in addition to allowing researchers “to develop bonding relationships with their research participants” (p. 11–12).

The researcher discusses the findings of results by interpreting lived experiences of the participants by imploring Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis of the themes and subordinate themes prepared from the data-collection process in a series of breakdowns that enable the reader to identify the connections between participants' lived experiences, and the phenomena that was existed during Meles Zenawi's era of Ethiopia. The discussion of findings of results is reported “thematically across the individuals” (Friberg, 2001; Ferm, 2004; Carlsson, 2011), therefore presentation and interpretation of the findings are based on the themes designed at the data gathering process.

Though IPA has its own data analysis steps—aligned more with hermeneutics phenomenology and is being used for interpretative analysis of the study—this researcher adopts Braun and Clarke (2016) step-wise thematic categorization, which is also acceptable to use in an IPA framework to conduct a phenomenological study, and Pietkiewicz and Smith (2014) four stages of inductive analysis for the interpretative part. Therefore, the researcher describes and interprets the interview data gathered from the participants using both the thematic Analysis and IPA with a qualitative phenomenological approach of study.

The researcher uses an inductive approach to give interpretative analysis of the findings based on theme identification from Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA), as it aims to compile and examine the interpretations people make on their experiences (Reid et al., 2005). Because the goal of IPA is to learn about the participants' perspectives, the process includes the researcher's interpretative activity, sometimes known as “double hermeneutic” (Tuffour, 2017). In other words, the researcher's interpretation of experiences is just as important as the subjects'.

According to Smith et al. (2009), due to its commitment to exploring, characterizing, interpreting, and contextualizing the participants' sense-making of their experiences, IPA has become a popular method for doing phenomenological research. This researcher mainly employs the inductive approach of IPA by using Pietkiewicz and Smith (2014)'s four key stages of phenomenological inductive analysis, which underpins the double hermeneutic, in which the researcher attempts to make sense of the participant's sense-making activity.

3.1. Research question

The research questions posed by the researcher and addressed in this article are:

RQ1: What obstacles and challenges did Ethiopian journalists face in their quest for a fair trial with the legal system?

RQ2: How did Ethiopian journalists tackle the challenges they ran against when they were being tried?

3.2. Type of data and sampling method

The type of data employed by this researcher is primary data, which consists of texts transcribed from interviews conducted with private press journalists and will be used to investigate the phenomenon under investigation in this study.

With this type of data, the researcher has two alternatives. The “Face to Face” or “One-on-One” Interview is the first type of data. The researcher conducts face-to-face interviews with private press journalists who are affected by, or have knowledge of, the issue under study in order to acquire the essential data.

The researcher also conducts online interviews with the then private press journalists who are currently living overseas. The interviews were performed using Skype or other online tools that allowed the researcher to connect with the participants face to face.

This study identified 12 private press journalists available to participate in one semi-structured in-depth interview between December 2020 and January 2022. The researcher uses the purposive sampling method to identify a more narrowly defined group for whom the research issue is relevant. Purposeful sampling, according to Creswell (2016), “is the act of selecting participants for a qualitative project by enlisting individuals who can help explain the study's key phenomenon” (p. 109).

When performing a phenomenological study, the researcher used sample data from “... only a few folks who have experienced the phenomenon” (Starks and Trinidad, 2007, p. 1374)—and who can provide a thorough account of their experience that might be enough to identify its core elements.

This researcher also applies Reushle (2005) principles of Connectivity, Humanness, and Empathy (CHE principles) for the ethical and methodological advantages of semi-structured interview research practices used to gather data.

Familiarity, topic grouping, emerging theme analysis, and write up are the four steps of analysis established by Pietkiewicz and Smith (2014) and used by the researcher in the results and discussion section.

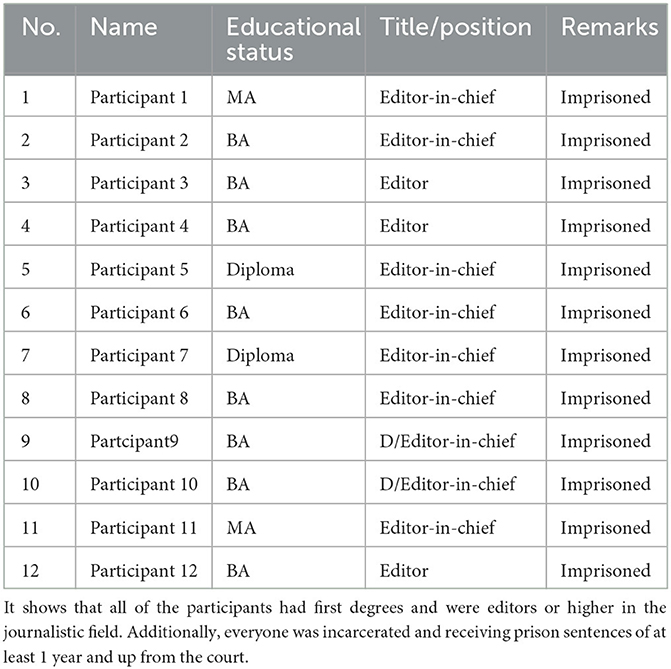

3.3. Participants' demographics

This study identified 12 private press journalists available to participate in one semi-structured in-depth interview between December 2020 and October 2021. The researcher drew on the participants' real experiences in addition to the demographic data provided in Table 1 at the end of this article.

4. Results and discussion

Courts, according to Ginsburg and Moustafa (2012), are frequently utilized to further the goals of authoritarian governments, but they are also sometimes transformed into key centers of political resistance (p. 6–7). Unfortunately, it appears the Ethiopian courts have chosen to take the former position.

According to Dicey, as cited by Mark (2012), just recognizing rights in a constitution does not safeguard or ensure an individual's rights. When the rights guaranteed by a constitution and other laws are violated, they must be maintained or defended in court.

Regarding the lack of judicial freedom in Ethiopia during the Meles era, Mgbako et al. (2008), also state:

The breakdown of separation of powers in Ethiopia is a result of a system in which a political organ with strong ties to the executive is the final arbiter of the constitutionality of the executive's political acts. One of the outcomes of this system is that judges are fearful of ruling on politically sensitive cases (p. 290).

The participants discussed the difficulties and problems they had encountered during their court case. They claim that the legal system is completely dominated by political power, and that it is just behaving like a puppet and doing what it is told. The three major themes that participants describe in their responses to this study question are: (a) Judicial freedom, (b) The proceedings, and (c) The verdicts. As a result, the researcher divided the question into three subordinate themes for interpretation, which are: (a) “Political operatives dress up as judges,” (b) “I knew you were innocent,” and (c) “I was punished without being charged,” under the major themes.

4.1. Judicial freedom

The breakdown of separation of powers in Ethiopia is a result of a system in which a political organ with strong ties to the executive is the last judge of the constitutionality of the executive's political acts (Mgbako et al., 2008). One of the consequences of this approach is that “judges are hesitant to rule on matters that are politically sensitive” (p. 290).

The participants described the difficulties and problems they encountered due to lack of freedom and independence of the judiciary, and based on their responses, this researcher interprets that the judicial system was completely under the control of political power, and that it was simply acting like a puppet and doing what it was told.

“Political operatives dress up as judges”.

Participant 1 was arrested more than ten times, and in each of those instances, he did not see a judge who was free of political bias or association. It seemed to him as though they had been appointed by the party or by Meles himself to indict and prosecute him and his colleagues with a crime. Judges never challenge or reject prosecutors' requests or appeals, whereas their plea was readily rejected and their ability to plead on a matter was lost. For him, it was a good example of the regime's dictatorial reign, which had lasted more than a quarter-century.

According to Participant 2 personal experience, there was no judicial freedom during Meles' era, and it was even amusing to witness how judges exercised their judicial power. All judges were appointed based on their political and ethnic affiliation with the regime. Of the two or three benches that were assigned on a regular basis to look into the cases of politicians and journalists accused of various crimes artificially designed by the regime, all judges were appointed based on their political and ethnic affiliation with the regime. Judges have pretended to be neutral in some cases, but as soon as they exhibit such behavior, they are sent to different benches.

Judges were assigned to preside over cases involving detained private press journalists and opposition politicians on a permanent basis, says the other participant. He claims that expecting judicial independence from political operatives posing as judges is impossible. Some of the regime's high-ranking officials had regularly encouraged him to work for them, but he had previously declined their offer. Though the prosecutor did not cite the regime's retaliatory action in his accusations, the judges' reflections revealed that they were aware of it. They had been mentioning such things in the middle of the procedure on occasion, and they had unwittingly betrayed their disdain for him.

Naturally, after his case had been adjudicated for more than a year, new judges were assigned to rule over his case. He recalls the new judges expressing a preference for his innocence or reluctance to accept the prosecutor's claims. Then, to seek for his case, other new judges who had proven their loyalty to the leadership swiftly replaced them.

Participant 4 recalls that the regime's high-ranking officials or the Party leaders personally appointed the judges. Some of the judges were members of the EPRDF or had some sort of affiliation with the party. So, Participant 4 wonders, how can one expect to see judicial freedom when all of the actors were chosen and allocated in such a way that they were expected to serve their political party rather than the public's interest? She had been treated by a slew of judges who treated her as if she were a criminal, displaying their open hatred for her.

She recalls judges being assigned to review the files of suspected politicians and journalists on a regular basis. In brief, the judicial system was set up in such a way that those linked with the EPRDF held decision-making power, and then judges were assigned who could be trusted to deliver rulings that the regime's leaders were happy with.

The other Participant sadly recalls the judiciary's lack of total freedom during Ethiopia's Meles era, when all press cases were referred to the high court's 10th criminal bench, which was presided over by Assefa Abreha, a top TPLF central committee member at the time. Meles appointed Assefa, the older brother of the then-defense minister Seiy Abreha, while his sister Timnit Abreha was also a government minister.”

When Assefa was appointed as a presiding judge to the only bench authorized to review cases of private press journalists accused with different press-related offenses, Participant 5 and his pals realized what the dictatorship was up to. Assefa and the other justices showed no interest in hearing their appeal at least once.

Participant 6 recalls the judges who presided over his case, and he is certain they were all members of the ruling party. According to him, anyone accused of political crimes was deemed an enemy of the state, and it was often impossible for him to even submit his case as a citizen with every legal right to defend himself, let alone secure a fair trial.

During Meles Zenawi's reign of Ethiopia, Participant 7 has never experienced judicial freedom all at once. He claimed that judges were chosen mostly on the basis of their political stance toward the ruling party, as well as their ethnic background. When the prosecutor delivered the charges, he recalls the judges refusing to let him register a complaint. They read their verdicts, and he was led to prison by the cops. He agreed with the other participants that there were judges who were specifically chosen and assigned to look into political issues, and that when private press journalists were arrested, their cases were also brought before these courts. They were appointed to promote the regime's interests and had no regard for the constitution or citizens' rights, he continues, his voice trembling.

Participant 8 agrees with the other participants that the judiciary was not free at all, because the bulk of the judges selected to hear their cases were either EPRDF party cadres or supporters. Meles had been arguing constantly, mentioning the Derg era, in which individuals were just pulled off the street and slaughtered, whereas during his rule, people were taken to appear in court for a fair and free trial. The paradox, according to Elias, was that prosecutors and judges were not politically neutral, as Meles had claimed for years, and they were passing their judgments on defendants after lengthy consultations with prosecutors or even security officials who seized them.

Participant 9 only had one chance to appear in front of the court, and it was in the judge's private office. He was thrown in jail without being charged with a crime, and the young judge, who was in her late twenties at the time, granted the police an additional 14 days for further investigation without allowing him to speak. He felt that his personal experience would aid him in comprehending the facts surrounding judicial freedom during the Meles era.

After being charged of instigating public unrest as well as being involved in a terrorist attack, Participant 10 appeared in court twice. However, because the prosecutors were unable to substantiate any of the charges filed against him in court, the judge allowed his release with a bail of 2,000 birr. However, they disobeyed the court order and threw him in jail, where he was ignored. Despite the fact that the court ordered his release, he spent nine months in the regime's brutal prison cells.

Participant 12 chooses one example to demonstrate how the judicial system was built to support the EPRDF government. It was about how she was interrogated about a relationship she had with someone who wrote a political piece on their blog page opposing the regime. As evidence, a Central Investigation Agency agent produced voice recorded material claiming to prove her relationship to the author of the piece. The prosecution presented the evidence against her in court and requested that the charge be accepted as adequate evidence implicating her for her role in a terrorist act. The judge dismissed Partcipant 12 request for the court to hear the recorded voice material brought against her as evidence. She cries out, “How can one expect to defend oneself in a court where the judge has refused his right to see the evidences produced against him?”

Participant 11 testified that in none of his four repeated wrongful arrests, he did not have the option to appear before an unbiased court with judicial independence. Participant 11 notices the judges' prejudice toward the government from the 1st day in court, and he subsequently witnesses how they ignore the defendant's appeal and make decisions based on the prosecutors' demands and requests.

4.2. The proceedings

According to Ginsburg and Moustafa (2012), courts are frequently utilized to further the goals of authoritarian governments, but they are also sometimes transformed into key centers of political resistance. Unfortunately, it appears the Ethiopian courts have chosen to take the former position.

The participants revealed the ordeals they went through during their case's judicial processes. The judges appear uninterested in even listening to their argument, regardless of how important the truth and reliability are. This researcher evaluates their depiction of lived experience, which may be utilized to show how courts exercised law throughout the EPRDF time.

“I knew you were innocent!”

Participant 1 discusses the court procedures that he went through after spending several months in jail for an inquiry. Following the secret operatives' acts of cruelty and brutality against him, he was met with judges who shared his viewpoint.

He first appeared in front of the court when he was the publisher of the weekly newspaper Ethiopis. The then editor-in-chief of the newspaper was also charged with encouraging violence between nations and nationalities, as well as broadcasting false information to the public. Their bail plea was denied, and they were obliged to defend themselves from prison.

According to Participant 1, he tried everything he could to defend himself, but the judges were uninterested in hearing his reasons. Instead, they granted police requests for more investigative time and repeatedly incarcerated him. The judge refused his bail rights, putting him in a dark room prison for a year until the prosecution persuaded the judge that if he was set free, he would have no complaints, and the judge gave his freedom. The prosecutor requested that the editor-in-chief be sentenced to 2 years in prison, which the judge granted. The editor-in-chief was sentenced to two more years in prison without being permitted to defend himself in a court proceeding in a free manner.

Judges, according to him, are essentially puppets of the administration who are appointed based on their political affiliation or ethnic background. He has never been allowed to defend himself in a court of law, despite the constitution's guarantee of citizens' rights and benefits. “It was difficult to expect a proper legal procedure presided over by such politically biased justices,” he recalls.

Participant 2 was first arrested in 2010 and was charged with 35 criminal offenses. After 4 months, he was hit with an additional 69 charges, bringing his total to 104 files. He believed that the allegations were brought against him in order to force him to flee the country or to frustrate and destroy his career as a journalist. However, he remained adamant, and they realized this and chose three accusations from the large list of crimes he was accused of. They charged him with “misleading the public's image of government,” “try to disrupt the constitutional system through mutiny,” and “defaming the government's good name.”

He recalls his lawyer asking the court how the government's name, if it has one, could be slandered, given journalists are supposed to be part of the government. According to Temesgen, it was unusual and unprecedented for a government to accuse a journalist of defaming its name.

Yared, a Harvard law professor, also appeared in court and gave a 1-hour long statement in which he rebutted all of the claims leveled against Participant 2. A total of 2,000 documents were provided to the court, which could have adequately contested all of the charges while also validating his innocence. However, the court ignored all of his reasons and sentenced him to 1 year in prison for each crime, for a total of 3 years in prison.

The indictment against Participant 3, he recalls, was that he published several articles in publications and on the internet associating with terrorist organizations such as the OLF, ONLF, Ginbot 7, and others. However, he stated that he had never had any personal contact with these organizations or any type of communication with them throughout his life. Surprisingly, there was no proof to support the claims leveled against him. The prosecutor once called four witnesses against him, but all of them testified in his favor.

The prosecutor read the charge against him as though he had been caught red-handed committing a crime on June 24. However, he refuted the accusation, claiming that he was arrested on June 22 and that it was impossible to commit a crime on June 24, as the accuser claimed. The judges, on the other hand, were unconcerned about it, instead informing the prosecutor to change the date of the crime for which he was charged.

Participant 4 recalls that the prosecutor was unable to provide evidence to prove her guilt, despite being charged with numerous crimes including: act of aggression against and attempt to destroy infrastructures; assisting terrorist groups through her journalistic career; receiving money from organizations designated as terrorists by the regime; and numerous others. On the other hand, the judges refused to hear her witnesses while allowing those who came to testify against her to do so.

She has asked the court twice to have two renowned politicians, Professor Merera Gudina and Doctor Yakob Hailemariam, attend as her witnesses and provide their professional testimony, but the judges have turned down her request both times. A judge even informed her at one of the court sessions that the court is not a parliament or a place for political debate. She expresses her displeasure with the way she has been treated in court over the years. The courts were hearing all the fake accusations and charges that the prosecutor had filed against her, she recalls with agony.

Even when the prosecution dismissed two counts, Participant 5 was charged with seven criminal offenses. As a result, he was required to appear in court once or twice a month. He was taken from his home and from prison by the authorities on several occasions. The charges alleged defamation of the government's and officials' good names. Though it is still unclear to him how a government can have a name that may be defamed, he was charged with and expected to defend himself on various allegations, including reporting fake news and inciting public insurrection against the government. However, they were unable to produce any solid evidence to the court that would show his guilt.

Participant 6 describes how the cops filed a criminal complaint against him and took him to court, where the matter was heard by a judge who was a young woman in her early twenties. The judge didn't seem disturbed while yelling and screaming about how he had been subjected to a lengthy inquiry and torture, as well as protesting why the police had denied him his constitutional right to appear in court within 48 h. While he was screaming and cursing, the officer requested an additional 14 days of investigation, alleging that the police probe had not yet been completed.

The young judge motioned for the officer to approach the bench and whisper to each other for a few minutes before deciding that the police would be given an additional 28 days to perform their investigation. He recalls her being the only judge presiding over cases involving political prisoners, and he regarded the court procedures in his case as a demonstration of the “so-called judiciary's freedom” during Meles' reign.

Participant 7 had been charged with a number of criminal offenses, and the judges were more concerned with the charges leveled against him by the police and secret service agents than with the evidence that may have disputed their assertions. On one charge, he was sentenced to 1 year in prison, and then the same court summoned him again to hear another case. Heportrays the judicial procedures at the time as a manufactured drama intended to appease Meles' government on the one hand, while punishing those who resisted or attacked him on the other.

Among the various claims leveled against him, Participant 8 recalls fostering hate between nations and nationalities, aiming to destroy the people's chosen government, as well as reporting or manufacturing lies to aid terrorist organizations. He was also charged with “using his journalistic career to incite public violence.” He was first charged in a news report published by “Awramba Times,” and the other two allegations were related to his membership in the Ginbot 7 party, which the regime designated as a terrorist group. But, after suffering and pain in their prison houses owing to the slow-moving legal proceedings, he was eventually released free of all the counts he was accused of.

Despite the fact that Participant 9 was suspected of being part in a terrorist act with the Al-Shabab group, he was never given the opportunity to defend himself in court throughout his 2 months in prison. The security guards, who had been drinking the night before when they arrived at his residence, took him to a detention center and interrogated him, hoping to find evidence of his involvement with the terrorist Al-Shabab group.

The court process had only taken place once, in the judge's private chamber, and she had done it on purpose to avoid journalists who had come to the courtroom to report on his case. After speaking with the security officers, the judge ordered his arrest and gave them an extra fourteen days to probe further. He couldn't speak even if he wanted to, but he was perplexed and even more startled to learn why they were wasting their time in such a foolish charade.

Participant 10 views the judges who were reviewing his case as political appointees, and he did not expect a fair trial from such a court. Those security agents who placed him in jail returned to the courtroom to watch his trial. The court didn't bother to inquire about their legal standing to file a charge at a prosecutor's office. She merely gave herself an extra 14 days to research, followed by another 3 months. When the police told her a bogus story that had incriminated him, the judge nodded her head in agreement throughout the court proceedings, Participant 10 laments.

Participant 11, who was charged with terrorism for the first time, claiming that the charge included no truth and that all of the stories were made up, claims that the charge included no truth and that all of the stories were made up. According to him, no witnesses or evidence were presented to demonstrate that he was guilty, and the judges were also aware from the beginning that he was innocent of all charges, but they just permitted the police to imprison him and continue their investigation. Participant 11 wept because the judges had denied him all of his rights to bond since he was accused with terrorism. For refusing to cooperate with secret service officers and police, the court sentenced him to almost 2 years in one of the country's worst prisons.

Participant 12 appeared in two courts; on her initial appearance in the first instance court, the police asked and were allowed further time to conduct their investigation. She reappeared after a month, and the prosecutor had already presented all of the fabricated documents, which contained numerous charges against her, including recruiting young people to join the Ginbot 7 Party, writing articles supporting a terrorist organization, and assisting members of the party by providing information, among others. Despite the fact that the cops and secret service agents couldn't discover a single piece of evidence to back up their assertions, the judge chose to convict her just by looking at the paperwork piled on his desk. She was also rejected a bail request since the charge leveled against her was “involvement in a terrorist act.”

During one of the court proceedings, the police said that while conducting an investigation, they discovered an Oromo Democratic Front (ODF) manifesto inside her computer files. After more than 2 months of creating evidence, the judge decided to transfer her case to the high court terrorism criminal bench, where she began to suffer for more than 2 years while defending herself.

The judges, Participant 12 says, had strong ties to the ruling party, the EPRDF, and couldn't seem to keep their disdain and anger toward her hidden. They were only interested in hearing the prosecutor's claims, and she was never permitted to invite her family, friends, or coworkers to any of the court proceedings. On one of her court dates, she invited a friend, who was a journalist at the time, and the secret service agents spotted him secretly filming the court procession late that day. The next night, she was violently removed from her cell and hauled to their investigation room. They forced her to remove her clothes and stand naked in front of them, where they began tormenting her in a terrible and abusive manner. One of the cops punched her in the face with his powerful biceps, while the other flogged her with an electric wire. She was beaten to death and returned to her cell at morning, tormented by all of their heinous acts, just because she invited a journalist friend to go and watch the court proceedings that day.

4.3. The judgments

Timothewos (2010) claims that the Ethiopian courts lacked expertise in interpreting the constitution because they were simply convicting journalists based on provisions invoked by the public prosecutor in his study paper, which focuses on how a lack of constitutional jurisprudence in Ethiopian courts can undermine freedom of expression. According to Timothewos (2010) in most cases, “…the courts carried on and applied the statutory provisions claimed by the public prosecutor without any attempt to attenuate the concerns that might arise in connection with the unfavorable ramifications of these provisions for freedom of expression and the press” (p. 226).

The descriptions of how the participants were convicted and how they received their verdict led the researcher to question the judicial organ's independence from government intervention during the Meles Zenawi era, as well as the courts' expertise in interpreting the law in accordance with the stated articles in the constitution, particularly the freedom of expression.

“I was punished without being charged”.

Participant 1 was charged with instigating violence and encouraging the public to destabilize the country's peace eight times. He was once accused of using guns to topple the regime, while admitting to never having had such an objective or experience in his entire life. He had never been released from prison, or at the very least, the judge had always sentenced him to pay a fine to the government, despite the fact that they couldn't find him guilty of any crime in practically all of the charges. They tortured him in their prisons for a period of time before releasing him with a monetary fee or spent 1 or 2 years in prison.

During the EPRDF dictatorship, he was sentenced to 18 years in prison for allegedly participating with the Ginbot 7 organization, which the regime categorized as a terrorist organization. Despite the fact that no evidence of his involvement in the group had been given to the court, he was sentenced to 18 years in jail. It has been difficult to defend oneself once charged with such a crime because the charge will be based on the country's Anti-Terrorism Law, which was purposefully written by the regime's officials to eradicate opposition groups. After that, he was held in Kaliti prison for six and a half years until a new administration led by Dr. Abiy Ahmed took control and freed him. Being a journalist, as well as having the courage to speak inner thoughts without fear, were seemingly to be considered crimes for Participant 1 to spent more than a decade in prison during the EPRDF era.

Participant 2 was taken aback when he realized that his case had been heard for more than 2 years, during which time the judges had been replaced five times. When the previous judge was transferred to another bench, the newly appointed judge began investigating his case from the beginning. But the judge who was finally appointed to preside over his case didn't bother to pore through the file like the others did, and he declared Participant 2 “guilty” of all the allegations against him. In less than a week, this judge sentenced him to 1 year of harsh jail on each charge, for a total of 3 years in prison without any evidence of wrongdoing. Because of a political decision rather than a judicial conscience, the judge allowed him to endure for 3 years in those dreadful dungeons.

Participant 3 had been held captive in several prisons across the country for the past 8 years, accused of terrorism. The kangaroo court of Meles Zenawi condemned him after reviewing his case under the country's Anti-Terrorism Law, but in actuality, his crime was simply stating the truth. He appears to be the only individual in Ethiopian legal history who has been found guilty and sentenced to 14 years in jail without any charges or evidences being presented to the court. He does not deny that there were a few judges with noble intentions and a strong commitment to the law. Unfortunately, when such judges were discovered, they were reassigned to different benches, while others trusted to carry out the regime's wishes were given an automatic appointment to hear his case. The judge who finally ruled over his case did not allow him to defend himself, but one day he rushed up to the courtroom and gave out a 14-year sentence without even glancing at Wubeshet (2016) face.

Participant 4 feels that the Meles dictatorship reacted against many of them in terms of judicial power, using such subsidiary laws as pretexts. She described the regulations as tools used by the regime to prevent private press journalists from carrying out their tasks in a free and independent manner, causing them to live in terror and despair. She was dissatisfied with the courts because they had never attempted to examine her case with a clear conscience and a guilt-free mentality. They were well aware that they were not practicing law with seriousness, and that they were not honoring their pledge in all of the court processions summoned to hear her case. They simply accepted the prosecutor's claim and sentenced her to 14 years in prison and a fine of 33,000 birr. The judges were well aware that the judgment made against her was a political one.

Participant 5 was charged with seven criminal counts before the Federal High Court, two of which were dismissed by the prosecutor while the remaining five were investigated. In the meantime, he was granted bail and began to await his verdict, after which he fled to Kenya to seek refuge. Many of the private press journalists who traveled to Kenya at the time realized that getting a free and fair trial in Ethiopia was difficult due to the kangaroo court system established during Meles' rule.

Friends of Participant 5 later informed him that the day after he traveled to Kenya, one of the criminal benches sentenced him to 1 year and 6 months in prison. It was one of the five cases in which he was charged. Then he interpreted the judgment issued in his absence as a clear message from the administration to abandon his ambition to return to Ethiopia if he did not want to face prison. There was no need for the judges to investigate the other charges against him since they knew he wouldn't want to return to the country where he had already endured enough misery and torment.

Participant 6 case did not receive a judicial decision. He had been imprisoned for months in a dark chamber, and secret service agents had been interrogating him day and night, in a hard and violent manner. In each of those instances, he appeared in court four times, with the judge granted the police a further 28 days to complete their investigation into him at each appearance. The judge, who was in her twenties, was only there to allow the police to do what they wanted. He eventually recognized that the cops had taken him to court to escape media criticism for depriving him of a fair trial.

Participant 6 received his judgment 1 day after being held in a dark room for months and being interrogated at all hours of the day and night. He was brought from his dungeon to the office of the Chief of the Criminal Investigation Agency by a police officer. “You may now return to your house,” the Head remarked, satisfied and smiling. He was forced out of the room before he could say anything. Sileshi received his verdict and was set free in this manner.

For writings and stories published in Ethop weekly, Participant 7 was charged with nine criminal counts. He referenced, for example, the news he broke about the Tigray Hotel bombing, for which he was condemned to 1 year and 4 months in prison by a first-instance court for publishing. He was then called by the court from prison to defend himself on other allegations. By appealing to the Supreme Court, he was able to defend himself and win prosecutor charges in a few cases. The case in which he was accused of press crime and sentenced to 1 year of hard jail by the first instance court exemplifies this. He eventually appealed to the Supreme Court, and the judge who investigated the case agreed with him.

Participant 7 was also charged with participating in an act of hostility with the Coalition for Unity and Democracy party (CDU) leaders, for which he was sentenced to 8 years in solitary confinement by the court. Despite his declaration that he had no relationship with the CDU at the time, the dictatorship utilized the claim to punish him for his activities as a free press journalist. There was also a charge of being part in a terrorist attack, for which he could face life in prison or 25 years in prison, but he vanished for a while and the administration changed before they realized their vengeance on him.

Participant 8 was imprisoned for 7 months without ever having the opportunity to appear in court. They took him to court after he had been in prison for 7 months. Without hearing his plea, the judge sentenced him to Kaliti prison, vowing to pursue his case from there. He suffered for a few months in Kaliti prison until the court summoned him again, and the new young female judge in charge of his case declared him guilty on his first appearance before the bench. She ordered his release and a fifty-thousand-birr bond to allow him to defend himself outside of jail. She further directed that if he wanted to travel overseas, a letter be drafted to the Immigration Agency telling them not to issue him an exit visa. It took more than 4 years for Elias' case to be closed once a new judge took her place. The new judge absolved him of all allegations brought against him in court, which he had been wrongly accused of.

In a court of law, Participant 9 received no verdict. He was seized from his home by security personnel late at night, imprisoned, and tortured for a year in several jails. He recalls a security official who had ordered his detention coming to the prison where he had been imprisoned for a year and shouting his name. When he walked out of his cell, the officer advised him to go home because he had been cleared of all charges. After a year in one of the harshest prisons in the capital, Participant 9 received his verdict in this manner.

In a similar vein, Participant 10 was released due to a police officer's judgment rather than a judicial order. He was not told to go home immediately, but rather through his brother, who had come to see him that day. He couldn't trust his brother when he told him the “wonderful news” at first because he had been suffering there for nearly a year. He was entitled to appear in front of a court of law at any point throughout that period. He didn't ask the police officer “why” that day, nor did he go to the police station to protest about the unjust suffering simply was subjected to in prison, but he fled. The officer later told his brother that he was freed because of a court order of 2000 birr bail, but he recalled that the court had issued such an order 9 months before, and he couldn't think of any reason why the police needed nearly a year to carry it out. He was released after a year in prison for a cause that even his arresters were unaware of.

Participant 12 was imprisoned for 3 years at the Central Investigation Bureau detention center and Kaliti jail, after which the prosecutor dropped the terrorist allegation against her and replaced it with “incitement of violence among different ethnic groups” in Ethiopia. The judge then granted her bail and allowed her to defend herself. A year later, the judge exonerated Participant 12 of all allegations against her. She recalls the judge's decision, which stated that all of the evidence given in court was “insufficient” to prove the charges she was accused of. When Hailemariam Desalegn came to power after being tortured, abused, and tormented for nearly 3 years by Meles Zenawi's thugs, she was liberated.

Participant 11 was charged with terrorism with the purpose of imprisoning him for years, if not his entire life, by the regime. The judges, he claims, showed no regret toward him, at least not out of professional or ethical values; rather, they were there to carry out the government's wishes. They couldn't find a single piece of evidence to indicate he was guilty of the charges against him after more than 2 years in prison, so they ultimately let him go.

He claims that his release was not due to the fact that the judges followed the law, but rather due to foreign and internal pressure on the government to recognize and order the courts to decide what it detested. So, after allowing the police to torture him for over 2 years, the court cleared him of all charges, but he was not allowed to leave the country until Prime Minister Abiy assumed office, at which point the new court decided to dismiss his case and grant him true freedom.

5. Summary and conclusion

5.1. Summary

In the 20 years of Prime Minister Meles' rule, hundreds of private press journalists were arrested, tortured, or forced to shut down their newspapers and magazines; and some managed to flee from the country in fear of persecution (Amnesty International, 1998, 2008; Human Rights Watch, 2001, 2015; Amnesty International Report - Ethiopia, 2002; Freedom House, 2012).

Following Prime Minister Meles Zenawi's ascension to power by toppling the Derg regime, a number of international and human rights organizations expressed concern about “unlawful arrest and torture of Ethiopian independent press journalists” (Amnesty International, 1998, 2008; Article 19 Report, 2001; Committee to Protect Journalists, 2001; Human Rights Watch, 2001, 2015; Reporters Without Borders, 2001; Amnesty International Report - Ethiopia, 2002; Freedom House, 2011). Reports which had been made by foreign organizations throughout the world were also routinely criticizing the dictatorship of Meles Zenawi as “one among the predators” of freedom of the press.

Many scholarly publications were also written, as well as analyses, on the dictatorship of Meles Zenawi's lack of press freedom (Alemayehu, 2003; Dagim, 2009; Skjerdal, 2009; Meseret, 2013). The government, on the other hand, accused the journalists of being “criminals and saboteurs” (Committee to Protect Journalists, 2001; Freedom House, 2011); they were also branded as war and destabilization provocateurs, and some were even designated as terrorists (Fesmedia-international, 2011; VOA News, 2012; Fortin, 2015; Human Rights Watch, 2015).

All those international human rights organizations accused Meles of “deceiving the world” as a democratic leader by simply putting the rights of freedom of the press and speech on paper, when in reality he was a true authoritarian whose government should be accused of committing numerous crimes and human rights violations in Ethiopia (Committee to Protect Journalists, 2001; Human Rights Watch, 2015).

Daniel Bekele, the former Executive Director of Human Rights Watch's Africa Division and currently Commissioner of the Ethiopian Human Rights Commission, was one of many who spoke out about the matter. “Its human rights record has dramatically deteriorated, non-violent protests have been shut down, opposition leaders, activists, and journalists have been arrested or forced to flee the country,” Daniel said, acknowledging that Ethiopia made economic advances under the late Prime Minister Meles Zenawi. Accusations of “terrorism” have been used to stifle critics and intimidate activists (Committee to Protect Journalists, 2001; Human Rights Watch, 2015).

The researcher, based on the participants' reply, discovered and came to the conclusion that the Ethiopian judicial processes during the Meles' era were to blame for their sorrow and despair, as majority of the participants saw the court of the time as a platform for regime officials to admit their wrongdoing, while the remainder saw the judges as puppets who were brought there to serve the dictatorship's evil goals. The researcher also knows that the participants believe the administration used the legal system as a tool to carry out its nefarious schemes against anyone who firmly voiced their objections.

The participants' responses led the researcher to the additional conclusion that the judges assigned to hear their cases were either EPRDF political cadres or regime supporters because they categorically state that all judges were chosen based on their ties to the dictatorship on a political and ethnic level and that they did not expect judicial independence from “political cadres posing as judges.”

These researcher, based on the participants description of the difficulties and problems they encountered due to lack of freedom and independence of the judiciary, finally interpreted that the judicial system was completely under the control of political power, and that it was simply acting like a puppet and doing what it was told.

5.2. Conclusion

This researcher interprets the socio-political phenomena that occurred during Meles Zenawi's rule of Ethiopia based on participants' feedback, as it often uses Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) as a methodology to develop new knowledge about a phenomenon not well-known or explored before, so that it has achieved its aim at filling the gap previous researchers didn't bother to look on.

Moreover, by exploring the lived experiences of private press journalists during Meles' regime the researcher shed new light on the then socio-political phenomenon by attempting to answer many unanswered questions, such as the crimes that the private press journalists were charged with, which resulted in their being imprisoned, tortured, and/or forced to flee the country, as well as the types of sufferings and ordeals that they endure to get a fair trial, and how they manage to survive them.

The researcher also interprets the journalists' perspectives on Meles and his regime, which have not yet been sufficiently studied and explored, as well as the struggles and hardships they go through to get a fair trial, the various ways the regime's security agents interfere with them as they go about their jobs, and their views on the constitution and other local and international laws relating to press freedom.

Examining the bleak aspects of the past will aid in rekindling the hopes for the future. Hundreds of private press journalists were arrested, tortured, and some managed to flee the country under Meles Zenawi's administration. However, the level of misery and anguish experienced by private press journalists in striving to practice their profession while exercising their constitutional rights remains unknown, both in academic and empirical investigations.

This research study can be regarded as innovative because no other research studies attempted to undertake a phenomenological analysis of the lived experience of private press journalists by examining how they dealt with all of those trials and tribulations in getting a fair judgment during Meles Zenawi's administration of Ethiopia.

The researcher is also convinced that studying the lived experiences of private journalists in Ethiopia during Meles Zenawi's rule is crucial for understanding the socio-political phenomenon of the time and for imparting crucial lessons to other African leaders as well as to future Ethiopian journalists and political figures on how to prevent repeating such heinous events. As Santayana (1905) puts it, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

Finally, the following issues have been listed by this study's interpretation as causes limiting journalistic freedom in Ethiopia under Meles Zenawi, which also, in a manner, contributes to the absence of judicial freedom:

5.2.1. Defamation provision

Article 43 (7) of the statute provides that defamation and false accusation against “constitutionally mandated legislators, executives and judiciaries” will be prosecutable “even if the person against whom they were committed chooses not to press charge[s].”

In essence, the Press Law allows for the criminal prosecution, punishment, or imprisonment of media professionals for defamation even in cases when there is no victim. This clause appears regressive and draconian in view of how criminal defamation laws are seen around the world, particularly for offenses committed against governments.

The media cannot carry out its duty to give the public with complete and accurate information if it is not allowed to comment on any and all news, whether it concerns the government or not. Also, there is a blatant violation of the public's right to knowledge.

5.2.2. Registration system

The authority of the then-Ministry of Information (MOI) was broadened in 2007 to include supervision of media source licensing and registration, partly as a result of the discussion surrounding the Draft Press Law. The Press Law recognizes this additional power and gives the MOI extensive latitude in deciding whether to issue licenses.

By establishing a licensing system, the Press Law not only establishes a connection between them but also a relationship in which the media is unable to function independently of the government. The press cannot afford to challenge the government's assertions or actions under this type of environment. The scope of the government's power is excessive: if the government views a media outlet's reporting as criminal, it may be closed down, investigated, or even brought to justice.

5.2.3. Huge penalties

Excessive fines levied against the press for insignificant infractions of the law are another way that the government may utilize the Press Law to repress the media. For instance, under the press law, the maximum fine for a defamation conviction is 100,000 Birr.

Should a media outlet be found guilty of what other jurisdictions would consider minor criminal violations, the severity of the fines levied by the Press Law might easily force it out of business. Furthermore, if the person or media source is unable to pay, the exorbitant fines could result in further punishment.

5.2.4. Putting journalists in prison

Almost 200 editors and writers from the independent private press have been incarcerated since 1992, according to an Amnesty International (1998). All of these arrests were related to newspaper stories that were critical of the government. The majority of them are regarded by the agency as political prisoners who were put in prison due to their journalistic work and peaceful expression of their ideas.

5.2.5. Using the press law as a weapon against press criticism

A variety of criminal and imprison able offenses were introduced in the Press Law's “Responsibilities of the Press” chapter to replace earlier legislation that restricted the media. Any press coverage that violates the restrictions stated under Article 10 (2) is punishable by up to 3 years in prison and/or a fine of up to 50,000 birr (equal to $7,700 USD).

In this regard, the researcher found that there were several instances of journalists being detained for denouncing government policies, intimidating the opposition, government personnel abusing their positions of authority or engaging in corruption, or for objecting to specific government actions. Some people were detained because of rumors that might not be genuine, were speculative, or were difficult to verify. Particular attention was paid to reporting on armed conflict, a topic with little government information.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alase, A. (2017). The interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA): a guide to a good qualitative research approach. Int. J. Educ. Liter. Stud. 5, 9. doi: 10.7575/aiac.ijels.v.5n.2p.9

Alemayehu, G. M. (2003). A discourse on the draft ethiopian press law. Int. J. Ethiop. Stud. 1, 103–120.

Amnesty International (1998). Journalists in prison - press freedom under attack, Ethiopia. Report. Available online at: https://www.amnesty.org.AFR/25/10/98 (accessed March, 2021).

Amnesty International Report - Ethiopia (2002). Ethiopia: Fear of Torture/ Prisoners of Conscience. Available online at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/40b5a1f310.html

Amnesty International. (2008). Prisoners of conscience and other political prisoners. Report - Ethiopia. Available online at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/483e278a41html (accessed April, 2021).

Aregawi, B. (2009). A Political history of the Tigray People's Liberation Front (1975-1991). Los Angeles, CA: Tsehai Publishers and Distributors.

Article 19 Report (2001). Annual Report of Meles Zenawi to the FDRE Parliament, The Issue of Press Freedom in Ethiopia. Retrieved from: https://www.article19.org

Bach, J. N. (2011). Abyotawi Democracy: Neither revolutionary nor democratic, a critical review of EPRDF's conception of revolutionary democracy in post-1991 Ethiopia. J. African Stud. 5, 641–663. doi: 10.1080/17531055.2011.642522

Bahiru, Z. (2002). A History of Modern Ethiopia - (1855–1991) (2nd. ed.) (a). Eastern African Studies: Ohio University Press.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2016). (Mis)conceptualizing themes, thematic analysis, and other problems with Fugard and Potts' (2015) sample-size tool for thematic analysis. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 19, 739–743. doi: 10.1080/2F13645579.2016.1195588

Carlsson, N. (2011). Struggling with written language. Adult students with reading and writing difficulties in a life-world perspective. Unpublished dissertation, ActaUniversitatisGothoburgensis, Gothenburg, Sweden.

Collins, H. (2010). Creative Research: The Theory and Practice of Research for the Creative Industries. Singapore: AVA Publications.

Committee to Protect Journalists (2001). “Attacks on the Press 2000: Ethiopia,” News, pp1, Available online at: http://www.cpj.org (accessed April, 2021).

Craig, G. (2007). The Media Politics and Public Life. South Asian Edition, Australia: Allen and Unwin.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design Choosing Among Five Approaches. New York: SAGE.

Dagim, A. (2009). Media and Democracy in Ethiopia: Roles and Challenges of the Private Media Since 2005, MA Thesis Submitted to the School of Journalism and Communication. AAU.

Darou-Salim, A. Q. (2017). Political Conditionality And Press Freedom: The Efficacy of Usaid Press Conditionalities in Ethiopia and Mozambique. Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma.

De Waal, A. (2012). The theory and practice of Meles Zenawi. African Affairs. 112, 148–155. doi: 10.1093/afraf/ads081

Dicey, A. V. (1995). Introduction to the Study of the Law of the Constitution. New York, NY: Macmillan.

FDRE Anti-Terrorism Proclamation (2009). Proclamation No. 652/2009; NegaritGazeta. Berhanena Selam Printing Press.

FDRE Constitution (1995). NegaritGezeta, FDRE Proclamation of Broadcasting Service, Proclamation No. 533/2007, NegaritGazeta. BerhanenaSelam Printing Press.

Ferm, C. (2004). Openness and awareness. A phenomenological study of music didactical interaction. Unpublished dissertation, Luleá University of Technology, Luleå, Sweden.

Fesmedia-international (2011). Ethiopia's media blues continues: new anti-terrorism law. Friedrich Ebert Foundation Report. Available online at: https://www.fesmedia-africa.org (accessed January, 2021).

Fortin, J. (2015). “Conflating terrorism and journalism in Ethiopia”, in An Annual Report by Committee to Protect Journalists. Available online at: https://www.CPJ.org

Freedom House (2011). Countries at the Crossroads-Ethiopia. UNHCR. Available online at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/4ecba64d32.html; http://www.refworld.org (accessed August, 2020).

Freedom House (2012). The Unhappy Legacy of MelesZenawi. Fromothermedia Available online at: https://freedomhouse.org (accessed January, 2021).

Friberg, F. (2001). Pedagogical encounters between patients and nurses in a medical ward. Towards a caring didactics from a lifeworld approach. Unpublished dissertation, ActaUniversitatisGothoburgensis, Gothenburg, Sweden.

Gasiorowski, M. J. (1990). The political regimes project. Stud. Compar. Int. Dev. 25, 109–125. doi: 10.1007/BF02716907

Gebru, T. (2000). The Ethiopia-Somalia war of 1977 revisited. Int. J. African Histor. Stud. 33, 635–667. doi: 10.2307/3097438

Ginsburg, T., and Moustafa, T., (eds.). (2012). Introduction: The Function of Courts in Authoritarian Poitics. Cambridge University Press.

Human Rights Watch (2001). Human Rights Development on Ethiopia. World Report. Available online at: https://www.hrw.org (accessed September, 2019).

Human Rights Watch (2015). Journalism is not a crime: violations of media freedoms in Ethiopia Report.

Husserl, E. (1931). Ideas: General Introduction to Pure Phenomenology (D. Carr, Trans.). Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

Keller, E. J. (1985). State, party, and revolution in Ethiopia. African Stud. Rev. 28, 1–17. doi: 10.2307/524564

Marcus, H. G., and Crummey, D. E. (2006). Socialist Ethiopia. Encyclopidia Brittanica, Inc. Available online at: https://www.britannica.com/place/Ethiopia/Socialist-Ethiopia-1974-91 (accessed January, 2020).

Mark, D. W. (2012). Dicey on writing the law of the constitution. Oxford J. Legal Stud. 32, 21–49. doi: 10.1093/ojls/gqr031

Meseret, C. R. (2013). The Quest for Press Freedom, One Hundred Years of History of the Media in Ethiopia. Lanham, MA: Row Man and Littlefield Publishers.