- Department of English, Université de Fribourg, Fribourg, Switzerland

When relevance theory tried to express the underlying processes involved during interpretation, Sperber and Wilson posited a process of context elaboration in which interpretation is seen as a path of least effort leading to the selection of a set of most salient contextual assumptions and implications. In this view, contextual assumptions are not randomly scattered in the hearer's cognitive environment during this context elaboration process. Instead, Relevance Theory claims that there are some organizing principles ordering contextual assumptions and determining which assumptions will be more likely to be accessed first in the process. The focus of this paper is on one such organizing principle captured by the notion of strength. Sperber and Wilson define it as the degree of confidence with which an assumption is held. While this notion has been posited right from the early days of Relevance theory, it has been left relatively untouched in relevance-theoretic accounts. In this paper, we will assess the explanatory potential of the notion of strength by linking it to the much-debated range of phenomena understood as related to commitment, i.e., the degree of speaker involvement in the truth of their utterance. Our goal will be to argue for a theoretical account of strength, in which strength is regarded as a cognitive marker of commitment, and more generally of the epistemic value of an utterance. In order to support this claim, we will present a series of original experimental designs in which we manipulated the level of speaker commitment in the information conveyed by their utterance. We predicted, on the basis of the theoretical model put forward, that such a manipulation would impact the level of strength. This cognitive effect, it is claimed, can in turn be measured through a recall task. We present results which support this model and discuss its implications.

1. Introduction

Commitment has attracted a lot of attention as it touches upon a range of central semantic and pragmatic phenomena such as truth, reported speech, modality and evidentiality, among others.1 As such, commitment appears in the work by scholars from different linguistic fields, including the French théorie de l'énonciation, Linguistic Polyphony, Speech Act Theory, Argumentation Theory, and Cognitive Pragmatics. All of these approaches pointed out that a speaker cannot always be said to be held responsible for what she communicates.2 Indeed, her degree of commitment—her level of endorsement of the information conveyed in her utterance—may vary and it can be linguistically modulated.

The purpose of this contribution is 2-fold: first it tries to further our understanding of the pragmatics of commitment phenomena by linking commitment to the properties which determine the salience of a given contextual assumption in the cognitive environment of a hearer. Thus, it offers a cognitive pragmatic model to account for the kind of processes at work when a hearer interprets an utterance and, crucially, when he has to assess the level of commitment associated with it. This model brings together the insights of the previously mentioned approaches to put forward a fine-grained, empirically testable pragmatic account of commitment. Second, this paper seeks to offer empirical evidence for the purported model by reporting on an experimental design that tests some of its most central predictions.

In Section 2, we offer some landmarks by providing a brief overview of the various approaches which have used the concept of commitment. We then proceed to propose a revised model for the analysis of commitment phenomena in a relevance-theoretic framework. In doing so, we also offer a detailed typology of commitment phenomena which allows us to identify more precisely the focus of this paper as the processes linked to the hearer's interpretation of the speaker's commitment. Section 4 develops the pragmatic model of commitment further and argues that the interpretation of the speaker's commitment to a given utterance contributes to determining the relative manifestness of the assumption derived from it in the cognitive environment of the hearer. Specifically, we claim that the perceived degree of speaker commitment to an utterance will directly influence the strength of the corresponding assumption in the hearer's cognitive environment. Based on these theoretical claims, the second part of the paper presents two experimental studies which test this main hypothesis. We conclude by discussing the results which provide support for the argument that commitment markers in a speaker's utterance have a cognitive effect on the manifestness of the corresponding assumption in the cognitive environment of the hearer.

2. Commitment

If commitment has long been recognized as a key aspect of communication, it has often been studied from an indirect theoretical perspective as a notion associated with some other linguistic phenomenon (see Coltier et al., 2009; Dendale and Coltier, 2011; Boulat, 2018 for an overview). Thus, even though the notion of commitment is repeatedly mentioned in contemporary linguistics, it is often combined with notions such as source, enunciation, truth, modality and assertion, to name just a few (Coltier et al., 2009; p. 7). Furthermore, scholars disagree on a number of properties associated with commitment: (a) its scope; (b) the person who is supposed to commit; (c) the type of content which one can be committed to; (d) the possibility of not being committed at all; and (e) the idea that commitment is a continuum rather than a categorical notion.

More specifically, commitment has been studied, often obliquely, through the lenses of linguistic domains such as Enunciation Theory (Culioli, 1971), Linguistic Polyphony (Ducrot, 1984; Nølke, 2001; Nølke et al., 2004; Birkelund et al., 2009), Speech Act Theory (Austin, 1975; Searle, 1979; Katriel and Dascal, 1989; Falkenberg, 1990. Argumentation Theory (Hamblin, 1970; Walton, 1992, 1993, 1996, 1997, 2008a,b; Beyssade and Marandin, 2009; Semantics (Papafragou, 2000a,b, 2006), as well as relevance-theoretic pragmatics (Sperber and Wilson, 1987/1995; Ifantidou, 2001; De Saussure, 2009; Moeschler, 2013; Vullioud et al., 2017; Mazzarella et al., 2018; Bonalumi et al., 2020).

Within the enunciative and polyphonic frameworks, commitment (referred to as endorsement)3 marks the speaker's subjectivity in the utterance and encompasses a range of linguistic phenomena (such as speech acts, modality, evidentiality, reported speech, amongst others) which give rise to a complex interplay between the speaker and the utterance itself. In Speech Act Theory, the speaker is not only construed as being committed to the meaning conveyed by the utterance, but also to what is being communicated, i.e., the action that she is trying to perform when uttering that utterance. Argumentation Theory construes commitment as a property that transfers from one statement to another. From this perspective, commitment forms a set of claims (the commitment store) that an arguer can be regarded as upholding in an argumentative exchange. Commitment is therefore thought of as a mental representation that captures an argumentative standpoint. Finally, Relevance Theory has addressed commitment from different perspectives by focussing on the way commitment expressed by the speaker interacts with the comprehension procedure in the epistemic evaluation of information. For example, studies on epistemic vigilance (Mascaro and Sperber, 2009; Sperber et al., 2010; Mercier and Sperber, 2017) have shown how the epistemic vigilance mechanisms will distinguish between the degree of commitment assumed by the speaker toward the content of the utterance and her degree of commitment as a function of her reliability as a competent source for the information conveyed by that utterance.4 In more recent approaches, scholars have investigated the impact that meaning-relations (explicit, implicit or presupposed) have on the perceived level of commitment to which a speaker can be held accountable (see Vullioud et al., 2017; Mazzarella et al., 2018; Bonalumi et al., 2020).

If each approach has attempted to find how best to represent the speaker's decision to endorse a given utterance at various degrees or to dissociate herself from that utterance, a survey of verbal aspects of commitment (see Boulat, 2018) shows that definitions and accounts of commitment markers in linguistics display the same heterogeneity observed on a conceptual level. Yet linguistic markers of commitment (such as plain assertions, epistemic modals and evidential expressions) have long been identified and studied in various areas of linguistic enquiry (see Ifantidou, 2001).

More recently, pragmatic approaches to commitment have tried to capture the cognitive aspects of commitment, as they have been highlighted by certain relevance-theoretic approaches (see De Saussure, 2008, 2009; Morency et al., 2008; Vullioud et al., 2017; Mazzarella et al., 2018; Bonalumi et al., 2020) for instance. This last type of approach on commitment phenomena looks promising and crucially lends itself to experimental testing.

In what follows, we are trying to revisit the notion of commitment to propose a new take on (a) its cognitive nature and (b) the part played by graded commitment markers in triggering commitment assignment processes. In doing so, we argue for a cognitively grounded pragmatic model which captures commitment as a determining factor for the strength of contextual assumptions stored in the cognitive environment of the hearer (see Sperber and Wilson, 1987/1995).

3. Revisiting a pragmatic model of commitment

In this paper, we want to extend the existing pragmatic account of commitment (see Boulat, 2015, 2018; Boulat and Maillat, 2017, 2018) as it has been set within cognitive, relevance-theoretic pragmatics (Sperber and Wilson, 1987/1995) and epistemic vigilance studies (Mascaro and Sperber, 2009; Sperber et al., 2010; Mercier and Sperber, 2017). In this model, we argue that commitment accounts tend to conflate different types of commitment phenomena which need to be distinguished and that it cannot be limited to the speaker's propositional attitude and to the result of a higher-level inference on the illocutionary force. Therefore, we propose a commitment typology, which includes and refines some of the categories identified by De Saussure (2008, 2009), Morency et al. (2008), Moeschler (2013).

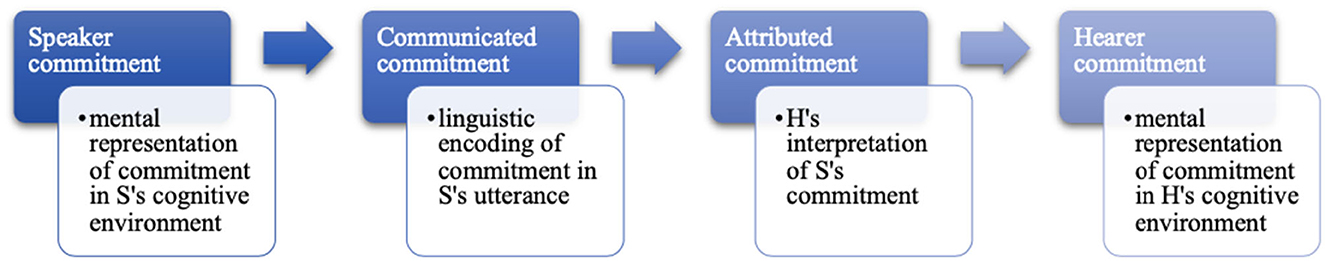

If scholars generally focus on a speaker-based pragmatic model of commitment, we think it is equally important to distinguish the hearer's perspective and therefore to include both utterance production and utterance comprehension phenomena in our account of commitment. Therefore, our proposal for a typology of commitment (Boulat, 2015, 2018; Boulat and Maillat, 2017, 2018), is inspired by an existing contrast in the theoretical literature on commitment between a linguistic and a cognitive focus on the one hand, and a production and comprehension focus on the other. This typology proposes to differentiate four types of commitment-related processes during a verbal interaction: speaker commitment, communicated commitment, attributed commitment and hearer commitment. The unfolding of these four different processes is illustrated in Figure 1.

In order to illustrate these typological distinctions, let us imagine a conversation between Elizabeth and Fitzwilliam, starting with utterance (1):

(1) Elizabeth: Jane is not a gold digger.

Before uttering (1), we must assume that Elizabeth has access to a mental representation of the assumption Jane is not a gold digger in her cognitive environment. This inscrutable side of commitment is what we refer to as speaker commitment, i.e., the degree of epistemic endorsement assumed by the speaker toward assumptions which are manifest in her cognitive environment.5 In relevance-theory this epistemic property which applies to the way contextual assumptions are represented in somebody's cognitive environment is captured under the notion of strength, which constitutes one of two properties of assumptions which determine their degree of manifestness in the cognitive environment.

“Manifestness depends on two factors […]: strength of belief and salience. These factors are quite different—one is epistemic and the other cognitive—and for some purposes it would be unsound to lump them together. However, we need to consider their joint effect in order to explain or predict the causal role of a piece of information in the mental processes of an individual (Sperber and Wilson, 2015; p. 133).6”

Going back to speaker commitment, Sperber and Wilson (1987/1995; p. 77) explain the type of parameters which affect the strength of a given assumption in her cognitive environment. They suggest that

[T]he initial strength of an assumption may depend on the way it is acquired. For instance, assumptions based on a clear perceptual experience tend to be very strong; assumptions based on the acceptance of somebody's word have a strength commensurate with one's confidence in the speaker; the strength of assumptions arrived at by deduction depends on the strength of the premises from which they were derived. Thereafter, it could be that the strength of an assumption is increased every time that assumption helps in processing some new information, and is reduced every time it makes the processing of some new information more difficult.

Hence, Elizabeth's assumption about her sister in example (1) is entertained with a high degree of strength. Since Elizabeth is a cooperative speaker (i.e., she wants to improve Fitzwilliam's representation of the world by giving him the opportunity to integrate an accurate piece of information in his cognitive environment), she produces utterance (1), which conveys a high degree of certainty, as it is presented as a plain assertion. Communicated commitment is thus defined as the public expression of what the speaker wants to convey about her level of commitment. Put differently, it refers to the speaker's ways of presenting her utterance with more or less certainty, and of presenting herself as more or less reliable.7 Obviously, speakers are not always cooperative so speaker commitment and communicated commitment are not necessarily aligned.

On the hearer's side, Fitzwilliam's understands Elizabeth's utterance and assesses the certainty of the content and Elizabeth's reliability. This is what we propose to call attributed commitment, which refers to the result of the hearer's assessment of the certainty of the communicated information and of the speaker's reliability, based on available linguistic cues and contextual assumptions. Elizabeth conveyed a plain assertion, therefore hinting at high certainty. Furthermore, Fitzwilliam knows Elizabeth well, he holds her in high esteem and thinks she is reliable. Based on this assessment of the content and of its source, Fitzwilliam integrates the piece of information Jane is not a gold digger in his cognitive environment. Since degrees of certainty and reliability translate into cognitive strength in our model (see below for a detailed discussion), Fitzwilliam assigns the assumption Jane is not a gold digger a high degree of strength. This is hearer commitment, which corresponds to the degree of strength assigned to the same piece of information as it is integrated in the hearer's cognitive environment.

Our proposition for a typology of the notion of commitment can be summarized as follows:

a. Speaker Commitment is the degree of strength assigned to the assumptions in the speaker's cognitive environment.

b. Communicated Commitment refers to the speaker's ways of explicitly presenting the piece of information with more or less certainty and reliability through the use of appropriate markers.

c. Attributed Commitment corresponds to the hearer's assessment of the certainty and reliability communicated by the speaker's utterance, based on available linguistic cues and contextual assumptions.

d. Hearer Commitment refers to the degree of strength assigned to this same piece of information as it gets integrated in the hearer's cognitive environment.

Not only does this typology distinguish the speaker's and hearer's perspective, it also draws a line between production and comprehension processes as well as the cognitive and linguistic component of commitment. Indeed, it deals with both mental representation (capturing commitment as a property of a cognitive representation) and linguistic marking (capturing commitment as a property of a linguistic form).

In the experimental design presented in this paper we explore the relationship between communicated commitment and hearer commitment showing how the linguistic markers of commitment in the speaker's utterance affects the integration of the information it conveys in the hearer's cognitive environment. In the next section, we extend our presentation of a cognitive pragmatics of commitment with a discussion of the concept of strength.

4. Measuring the strength of assumptions

Our alternative model of commitment is crucially built on the notion of strength which is a property of assumptions in the cognitive environment. According to Clark (2013; p. 114), most of our assumptions are tentatively entertained to varying degrees. This is what Sperber and Wilson (1987/1995; p. 75) refer to as the strength of an assumption, defined as the confidence with which it is held and as the result of its processing history (Sperber and Wilson, 1987; p. 701). Relevance Theory applies the concept of strength to all assumptions in an individual's cognitive environment. According to Ifantidou (2000; p. 139), degrees of strength are directly related to degrees of commitment. She writes that “the strength of an assumption for an individual is equated, roughly, with his degree of confidence in it” (Ifantidou, 2001; p. 73). Indeed, if the speaker chooses to use an evidential marker in her utterance, this marker is considered to affect the strength of her communicated assumptions, and therefore, her degree of commitment to the proposition expressed. In line with these authors, we claim that commitment has a bearing on the degree of manifestness of a given assumption as it influences its strength in the cognitive environment.

We argue further, in line with the claims made in Sperber et al. (2010), that the perceived commitment of the source to the information conveyed by her utterance will be determined by two factors: the degree of certainty with which the content is being communicated (by means of evidentiality markers) and the reliability of the source of information (evaluated in terms of competence and benevolence). These two notions are similar to those found in Mazzarella (2013). When she describes the mechanisms of Epistemic Vigilance posited by Sperber et al. (2010), she refers to an “alertness to the reliability of the source of information and to the believability of its content […].”

Crucially though, in this pragmatic account of commitment, the effect that commitment has on the hearer's processing of an utterance is not evaluated in terms of an inference drawn about the credibility of the speaker, or an inference about the impact the utterance has on the social reputation of the speaker, as proposed in recent relevance-theoretic studies of commitment phenomena (e.g., Vullioud et al., 2017; Mazzarella et al., 2018; Bonalumi et al., 2020). Instead, we want to propose that degrees of commitment leave a trace in the cognitive environment of the hearer by modifying the degree of manifestness of the representation of that utterance. Below, we consider how different linguistic markers of commitment can affect certainty and reliability, thereby altering the strength of the assumption conveyed by an utterance.

On the one hand, the kind of certainty envisaged here concerns the content of an utterance. It typically refers to the speaker's communicated assessment of the epistemic status of the state of affairs. This content can be said to be more or less certain as the speaker has the possibility to linguistically express more or less certainty via different markers, such as plain assertions, epistemic modals and evidential expressions (Papafragou, 2000a,b; Ifantidou, 2001; De Saussure, 2011; Hart, 2011; Marín-Arrese, 2011; Oswald, 2011; Wilson, 2012). Let us consider the following examples:

(2) Elizabeth is reading Mr Darcy's letter.

(3) Elizabeth may be reading Mr Darcy's letter.

(4) I think that Elisabeth is reading Mr Darcy's letter.

If the speaker utters a plain assertion as in (2), it conveys more certainty than if she modifies her utterance with an epistemic modal [see (3)] or with an evidential expression as in (4). Indeed, epistemic modals and evidential expressions are known to have either a weakening or strengthening function with respect to the speaker's commitment (Ifantidou, 2000, 2001). Therefore, the hearer assigns a degree of strength to the assumptions conveyed by the speaker's utterance, guided by these linguistic markers. We argue that this strength assignment impacts the hearer's integration of this same piece of information in his cognitive environment.

On the other hand, reliability is about the source of information, which includes two components: the speaker's reputation and her access to evidence. Following studies on epistemic vigilance (Mascaro and Sperber, 2009; Sperber et al., 2010; Mazzarella, 2013), the speaker's reputation is construed in terms of competence and benevolence. Competence refers to the fact that the speaker possesses genuine information, whereas benevolence corresponds to her wish to share her genuine knowledge with her audience. The speaker's access to evidence is the type of evidence she has when she communicates an utterance. Evidence is typically thought of as direct or indirect. The former type of evidence is usually considered more reliable than the latter. Indeed, an utterance based on direct evidence (i.e., evidence acquired via direct perception, as in 5) is presented as accurate and therefore more likely to be accepted by a hearer than an utterance based on indirect evidence, as in (6), (Cornillie and Delbecque, 2008; p. 39):

(5) I see that Mr Bingley is home.

(6) Reportedly, Mr Bingley is home.

From this perspective, (5) is more reliable than (6) because the speaker of (5) indicates that she has clear perceptual evidence about the fact that Mr Bingley is home. Yet, in (6), the evidence is marked as indirect, as the speaker uses the hearsay adverb reportedly, which suggests that she does not have direct evidence for what she communicates (Iten, 2005; p. 48).

According to our pragmatic model of commitment, commitment assignment processes take place in the relevance-theoretic comprehension procedure as theorized by Sperber and Wilson (1987/1995). It starts with the speaker producing an utterance of the type commitment marker (p). As previously mentioned, commitment is construed as a function of both certainty (which applies to the content of an utterance) and reliability (which applies to the speaker's reliability). These different degrees of certainty and reliability, which are communicated by the speaker's utterance, are represented in the hearer's cognitive environment through the derivation of higher-level explicatures, defined as a type of explicature “which involves embedding the propositional form of the utterance […] under a higher-level description such as a speech-act description, a propositional attitude description or some other comment on the embedded proposition” (Carston, 2002; p. 377). Following Ifantidou (2001), Papafragou (2006) and Moeschler (2013), we claim that these higher-level explicatures will determine the level of commitment assigned by the hearer to the assumption conveyed by the utterance (also echoing Katriel and Dascal, 1989 proposal). Therefore, through higher-level explicatures about the certainty and reliability associated with a given utterance, the degree of strength of the assumption will be modulated in the hearer's cognitive environment.

From this perspective, strength affects the degree of manifestness of all assumptions in the cognitive environment and can be regarded as the cognitive trace of commitment. We suggest further that if the hearer assumes the piece of information to be certain and the speaker to be reliable, then the corresponding assumptions in his cognitive environment will be assigned a high degree of strength and will be more made more manifest as a result.

For this model to be complete, we would want to be able to measure varying degrees of strength in the cognitive environment of the hearer. Interestingly, in their original discussion of strength, Sperber and Wilson identified a possible effect that varying degrees of strength could trigger. They write that:

Understood in this way, the strength of an assumption is a property comparable to its accessibility. A more accessible assumption is one that is easier to recall (Sperber and Wilson, 1987/1995; p. 77).

On the basis of this claim, it would follow that if an assumption were conveyed with a higher degree of commitment, both in terms of its certainty and/or reliability, it would impact its accessibility in the cognitive environment and, as a result, it would be expected to affect the hearer's ability to recall that assumption.

5. Experimental study

Based on these theoretical considerations, our prediction about the expressed degree of certainty is based on the obvious fact that linguistic markers such as plain assertions, epistemic modals and evidential expressions indicate the communicated degree of certainty the speaker assigns to her utterance. Hence, the more the piece of information is linguistically presented as certain, the more likely the hearer is to attribute a strong commitment to the speaker (modulo his assessment of her reliability). He will then be likely to integrate this same piece of information is his cognitive environment with a high degree of strength. Thus we claim that H1 high certainty markers (such as I am sure that, I know that, for sure, etc.) increase the degree of strength assigned to the communicated assumption in the cognitive environment of the hearer.

Our main contention is that certainty markers impact on the acceptance of a piece of information in an individual's cognitive environment, i.e., that they influence hearer commitment. This is in line with theoretical claims about epistemic vigilance mechanisms, as the more certain the piece of information is, the less activated the hearer's epistemic vigilance mechanisms are, and the more likely its acceptance will be (see Moore and Davidge, 1989; Sabbagh and Baldwin, 2001; Jaswal et al., 2007; Sperber et al., 2010; Bernard et al., 2012 and Mercier et al., 2014; inter alia). Thus, Sperber et al. (2010, p. 369) write:

“Factors affecting the acceptance or rejection of a piece of communicated information may have to do either with the source of the information—who to believe; or with its content—what to believe.”

Following up on this claim, we argue further that commitment markers will modulate the acceptance of a communicated assumption by assigning more strength to an utterance presented with high certainty markers, while low certainty markers will lead to lower strength.

Consider examples (8–10):

(8) I am sure that Caroline Bingley is interested in Mr Darcy.

(9) I think Caroline Bingley is interested in Mr Darcy.

(10) I don't know if Caroline Bingley is interested in Mr Darcy.

Comparatively, the hearer will be more likely to accept and integrate (8) in his cognitive environment given the certainty conveyed by the propositional attitude marker I am sure than (9) which suggests considerably less certainty. In our view, example (10), on the other hand, does not convey any commitment since the speaker communicates that she is unable to endorse the information that Caroline Bingley is interested in Mr Darcy with a sufficient degree of certainty.

Results of several empirical studies using a recall or recognition paradigm (see, for instance, Birch and Garnsey, 1995; Mobayyen and de Almeida, 2005; Ditman et al., 2010; Fraundorf et al., 2010 and Spalek et al., 2014) indicate that some linguistic features (such as focusing constructions, pitch accent type, focus particles, verb complexity or pronouns) lead to a stronger representation of the utterance in the participants' cognitive environment, and hence to a higher accessibility in memory than other features. In line with these results and the theoretical link connecting strength, accessibility and recall (see previous section), we hypothesize that commitment markers (i.e., markers of certainty) will also affect cognitive processing in the same way. Indeed, we claim that H2 the higher the certainty of a communicated content, the more accessible the assumption is in the hearer's cognitive environment. It follows that, within a recognition paradigm [where accuracy rates provide evidence regarding the accessibility of the representation of the test utterances (Traxler, 2012; p. 191)], an assumption that is highly accessible will trigger higher recognition scores. Therefore, the more committed the hearer is to a given assumption, the easier it will be for him to remember the assumption.

We posit a link between the relevance-theoretic notion of strength and an individual's ability to access assumptions stored in his cognitive environment. According to our model, cognitive strength translates into accessibility in the hearer's cognitive environment.8 Following Sperber and Wilson (1987/1995; p. 77), we argue that an assumption's assigned degree of strength, will affect its relative accessibility. We thus suggest that H3 hearer commitment impacts upon how information is remembered by an individual.

5.1. Experiment 1A about certainty

The aim of this first study was to test whether linguistic markers of certainty indicating different degrees of speaker commitment would impact how participants remember statements presented to them during a study phase. The predicted cognitive effect on memory was measured through accuracy in a recognition task taken after a distractor phase.

In order to test whether certainty markers impact on how participants recall given statements, linguistic markers were placed in three different groups: no-commitment markers (e.g., I don't know, I'm not sure, I hope); weak commitment markers (e.g., I guess, I think, It seems) and high commitment markers (e.g., I am sure, I know, No doubt).9,10 The influence of the three groups of commitment markers was tested with a yes-no recognition task where participants were presented with 30 factual statements about a fictional narrative, in which statements were presented with linguistic markers expressing different commitment levels. Within this recognition paradigm, better recall was predicted for statements containing a high commitment marker than for those including a no-commitment marker. A graded structure across the three categories of linguistic markers was also expected.

5.1.1. Participants

Ninety Seven native English speaking Mturk workers from the United States aged 18 to 60 (48 female, 49 male) participated for monetary compensation to an online survey.11 All workers provided written consent prior to taking the survey.12

5.1.2. Stimuli

We created 30 statements about a fictional narrative regarding a crime committed in Mr Black's house. These short factual statements were carefully controlled for number of words (M = 6.03 words) and frequency. 13 The critical words were the last word of each statement (n = 30) and were either previously studied or new. They were selected according to their length (1–2 syllables), part of speech (i.e., nouns) and frequency (50 to 600 occurrences per million words). New words were selected on the basis of the length, the part of speech, the frequency and the meaning of old words (i.e., the words previously studied). For example, for the following stimulus Mr Black called his old mother, the word mother was the “old” critical word (i.e., the word which had been previously studied before the recognition test) and the new word was father, which had not been studied before in that carrier sentence before the test.

5.1.3. Recognition test

This within-subject yes-no recognition task included 30 statements. Half of the statements were old (i.e., the exact same statements as presented to the participants in the study phase with the same linguistic marker of no-/weak/high commitment) whereas the remaining 15 statements were new (i.e., where only the critical word was modified and replaced by a word which was not presented in the study phase, but keeping the same linguistic marker of no-/weak/high commitment). Ten statements included a high commitment marker (e.g., I know, I am sure), 10 a weak commitment marker (e.g., I guess, I think) and 10 a no-commitment marker (e.g., I don't know, I hope). The statements were rotated through the different test conditions: the commitment levels (no-commitment, weak commitment, high commitment) and recognition (old vs. new). For example, the statement mentioned above Mr Black called his old mother, was rotated as follows through the different conditions in the study phase: Nobody knows if Mr. Black called his old mother (lists A and B), Mr. Black probably called his old mother (lists C and D) and Mr. Black clearly called his old mother (lists E and F). 15 trials were designed to prompt a positive response (i.e., “yes) and the other 15 trials a negative response (i.e., “no”). Six lists (i.e., A-F) were created by combining linguistic markers and old-new critical words using a Latin Square. As a result, there were 6 versions of the study, that is 6 lists of pseudo-randomized statements. Two sample pairs of stimuli used in the study phase and the recognition test are presented below.

Study phase

Mr. Black clearly called his old mother

I am unsure whether the old lady found a picture

…

Recognition test

I am unsure whether the old lady found a picture (correct answer: yes)

Mr. Black clearly called his old father. (correct answer: no)

…

5.1.4. Procedure

The experiment started with a consent form, a few demographics questions (i.e., age, gender and languages spoken) and with an on-screen instruction informing participants of the structure of the experiment. Participants were told that they would read statements the police got from a witness, about a crime committed in Mr Black's home. Participants were asked to carefully read the 30 statements provided by the witness. However, the format of the memory task was not specified. Participants were told that the to-be-recalled statements would appear briefly on the screen, for 3 s, during the study phase. After 3 practice trials, participants were warned that the task was about to start.

In line with Birch and Garnsey (1995) and Ditman et al. (2010) studies, statements were visually and individually presented for 3 s and appeared one at a time, before disappearing. Statements were presented on the screen black on white using the font Times New Roman, size 14 pt.They were then followed by the question “how would you evaluate the certainty of this piece of information?” Participants had to rate the statements on a 5-point Likert scale (where 1 = uncertain that it is the case and 5 = absolutely certain that it is the case). The ranking task was not timed so participants could answer at their own pace. The rationale for using a certainty rating as well as for not specifying the format of the memory task was to ensure that participants would process the whole statements (and not overlook the linguistic marker of certainty). Each participant was presented 30 statements and none was presented the same statement more than once. The experiment lasted 15 to 20 min. Following Ditman et al. (2010) design, a delay was placed between the study phase and the recognition test. Participants had to answer 60 simple arithmetic questions. This distractor task took ~10 min to complete.

After answering the 60 arithmetic questions, a message appeared on the screen and informed the participants that their memory of the statements would be tested. Participants were also told that they would be presented with the question “Did the witness say the following to the police?”, which would be followed by a statement such as Mrs Lily loved dark chocolate. The participants had to indicate whether the statement they would be presented with was one of the statements they previously read in the study phase or not. They were asked to tick the “yes” box only if the statement was exactly the same (e.g., Mrs Lily loved dark chocolate). However, they had to tick the “no” box if the statement was not exactly the same (for instance, if they were presented with the statement Mrs Lily loved white chocolate).

Participants finally took the yes-no recognition task where the last word of each statement was either old or new (e.g., I am unsure whether the old lady found a picture/paper or The butler clearly moved to the North/South). Participants were asked to answer “yes” or “no” for the 30 trials which were individually and randomly presented, in line with Ditman et al. (2010) design. When participants correctly ticked the “yes” box when the statement was old, it was recorded as a correct answer whereas if they incorrectly pressed “yes” when it was a new statement, it was scored as an incorrect answer.

5.1.5. Results

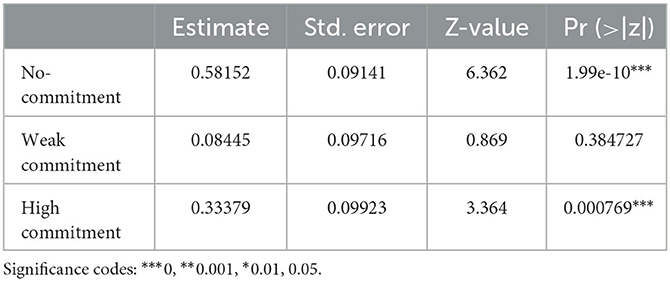

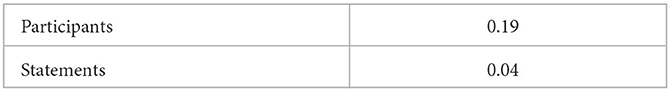

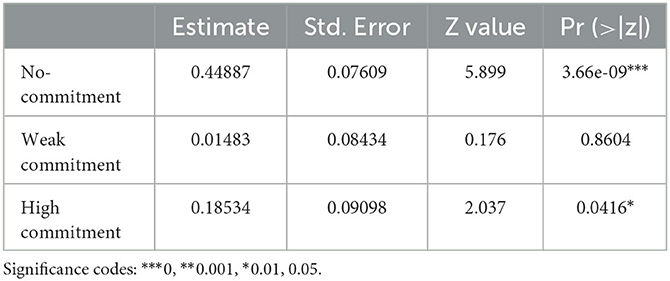

We used R (R Core Team, 2016) and the lme4 package (Bates et al., 2015) to run a generalized linear mixed effects analysis (with only random intercepts) of the interaction between commitment markers (i.e. the fixed effect) and accuracy. The analysis shows that the two categories of no-commitment and high commitment are good predictors for accuracy in the recognition task (see Tables 1, 2).

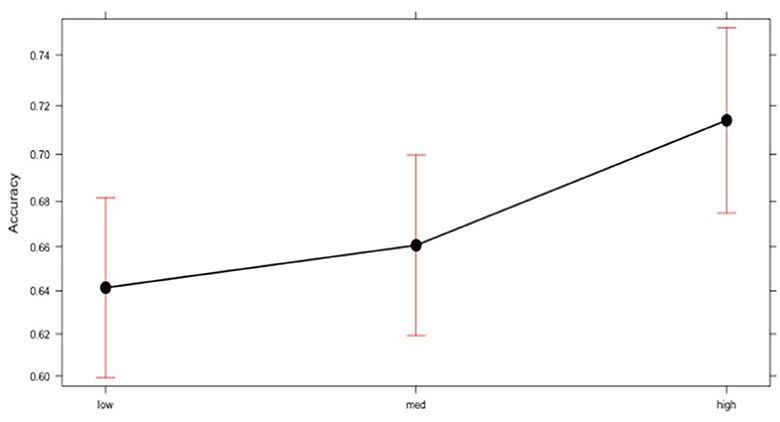

Converting the log odds given in the model (under “estimate” in Table 1) provides us with the probability of correct answers in the recognition task in each category of commitment markers: no-commitment category (0.64), weak commitment category (0.66, not significant p = 0.38) and high commitment category (0.71, p = 0.0007).

Given these results, we can say that commitment marker categories affect accuracy in the recognition task (χ2 (2) = 12.16, p = 0.002283). Figure 2 below shows a slight increase in accuracy between the no-commitment and the weak commitment (labeled “med” for medium in the graph) categories. Even though there is no statistically significant difference between the two categories, the expected graded trend is visible.

5.1.6. Discussion

Results of experiment 1a indicate that statements containing a high commitment marker were recalled significantly better than statements containing a no-commitment marker. These results are compatible with the predictions of our pragmatic model of commitment since the cognitive impact on the processing of utterances correlates with the level of commitment expressed in the stimulus, specifically through the use of certainty markers.

However, further analyses revealed a possible interaction between the length of the statements and accuracy. Indeed, it was found that the mean of syllables per linguistic marker category might have affected the results (i.e., for no-commitment markers, M = 4 syllables; for weak commitment markers, M = 3.7 syllables, and for high commitment markers, M = 2.5). Since literature on recall and recognition shows that longer words or longer utterances are harder to recall than their shorter counterparts, it is possible that participants' high accuracy rate in the high-commitment condition is due to the reduced length of the statements (and not to the fact that information conveying certainty is recalled better than information conveying uncertainty).

In order to check for this eventuality, the number of syllables per statement was factored in as an independent variable.14 Compared against the model with accuracy as the independent variable, we see that both models provide a good model fit (p = 0.002 when accuracy is the independent variable and p = 0.0001 when the length of the statement is). This could indicate a potential hidden variable in our initial model (namely, the length of the statement) which might explain the observed effect.

5.2. Experiment 1B

In this second study, our goal was to address some of the limitations identified in the first design and to rule out the possibility that the effect observed there was the result of a confounding factor. For that purpose, a new version of the same experimental design was set up which controlled for additional parameters.

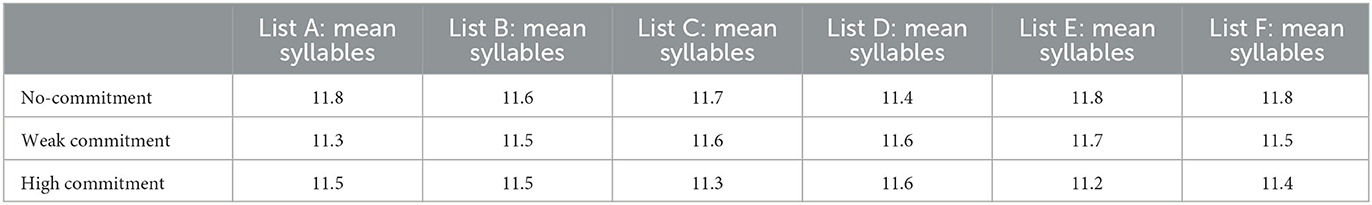

In order to confirm that commitment markers triggered the observed effect and to discard the hypothesis that it was due to the length of the statements, we controlled length across the different types of certainty markers in experiment 1b. Longer linguistic markers were matched to shorter statements (in terms of syllables) and shorter linguistic markers were matched to longer statements (see Table 3).

Furthermore, it was also noticed that the randomization of stimuli in experiment 1a was not optimal. For instance, the first five and last five statements contained too many linguistic markers of the same category in some lists, which may have led to primacy and recency effects. As a result, particular attention was paid to the randomization of statements in experiment 1b (the lists used in the study phase are provided in the online repository).

Finally, experiment 1b addresses the potential criticism that experiment 1a might be task-specific. Since participants were explicitly asked to rate the degree of certainty of the linguistic markers after reading them in a statement, the instructions might have made participants aware of what was really being tested and this might have biased their processing of the statements. To overcome this possible criticism, the ranking task was removed from experiment 1b.

5.2.1. Participants

One hundred and thirty three native English-speaking Mechanical Turk workers (from the United States) aged 18 to 60 (60 female, 73 male) participated for monetary compensation. All workers provided written consent prior to taking the survey.

5.2.2. Materials

Thirty short factual statements were used in experiment 1b as in experiment 1a. However, the statements in the 6 lists were randomized in such a way that the first and last five statements would not display more than 2 items of the same commitment category, to avoid primacy and recency effects.

5.2.3. Procedure

After agreeing to participate in the survey and answering a few demographics questions, participants were told that they would read statements the police got from a witness, regarding a crime committed in Mr Black's house. They were instructed to carefully read the 30 statements provided by the witness. The format of the memory task was not specified. Participants were warned that during the study phase, the to-be-recalled statements would appear on the screen for 3 s. Then, participants performed 3 practice trials. During the study phase, each participant was presented 30 statements and nobody was presented the same statement more than once. The experiment lasted 15 to 20 min. The distractor task and the recognition test were similar to those in experiment 1a.

5.2.4. Results

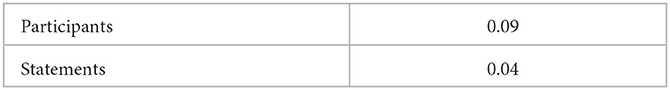

Our model uses commitment level as a fixed effect (i.e., no-commitment, weak commitment, and high commitment, based on the pre-test results) and as a categorical predictor for accuracy in the recognition task. The analysis shows that the two categories of no- and high commitment are good predictors for accuracy in the recognition task (as shown in Tables 4, 5):

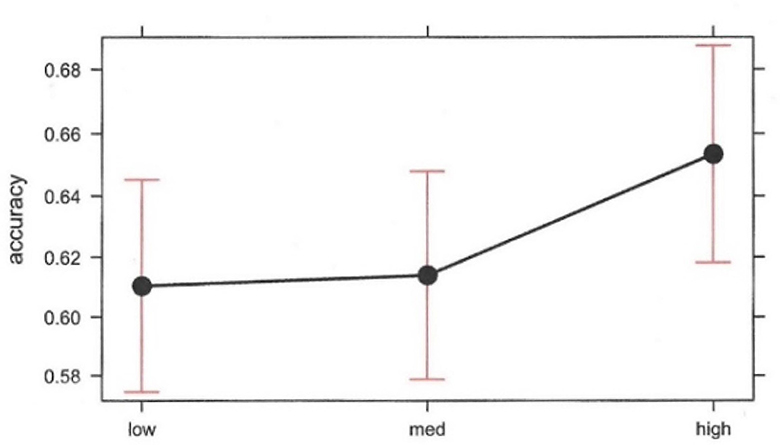

Converting the log odds given in the model (under “estimate,” in Table 4) provides us with the probability of correct answers in the recognition task in each category of commitment markers: no-commitment category (0.61), weak commitment category (0.61) and high commitment category (0.65, p < 0.05).

In light of these results, we can say that our findings are consistent with the predicted effect that commitment marker categories should have on accuracy in the recognition task (χ2 (2) = 5.17, p = 0.0754). Results indicate that commitment markers significantly impact the accessibility of assumptions.

Figure 3 shows a slight increase in accuracy between the no-commitment and the weak commitment categories (the weak commitment category is labeled “med” for medium in the plot below). Even though there is no statistically significant difference between the two categories, the expected graded trend is visible.

5.2.5. Discussion

The present results replicate the findings in study 1a, suggesting that participants remember statements conveying certainty differently than statements conveying uncertainty. Indeed, the participants' performance was significantly affected by commitment markers of high certainty. Once the ranking task had been removed and the stimuli controlled for length across all conditions, there is still a significant difference between the two categories of no-commitment and high commitment in terms of accuracy of recognition, even though the observed effect is weaker than in experiment 1a. Specifically, results show better retention of statements when participants were presented with a high commitment marker than with a no-commitment marker.

6. General discussion

Overall, our findings are fully in line with the predictions presented earlier and support our relevance-theoretic model of commitment which posits that commitment (as it is influenced by the communicated degree of certainty about the information conveyed) determines the strength of the contextual assumptions derived from the interpretation of a given utterance, which, in turn, affects the accessibility of these assumptions in a recall task.

Specifically, our findings provide supporting evidence for Hypothesis 1 which states that high certainty markers (such as I am sure that, I know that, for sure, etc.) increase the degree of strength assigned to the communicated assumption in the cognitive environment of the hearer. Moreover, it also goes toward confirming the relationship between communicated commitment, as expressed by the speaker in the utterance by means of linguistic markers, and hearer commitment, as measured by the strength of the assumption derived from that utterance.

Hypothesis 2 (the higher the certainty of a communicated content, the more accessible the assumption is in the hearer's cognitive environment) concerns the theoretically motivated relation between the relevance-theoretic notion of strength and the relative accessibility of a mental representation stored in the cognitive environment of the hearer. It appears that the early claims by Sperber and Wilson (1987/1995) about the impact of strength on recall are vindicated by these findings.

Crucially, because certainty was manipulated in these experiments as a parameter which determines the degree of commitment expressed by the speaker toward the information conveyed by her utterance, we can take our findings to speak in favor of a pragmatic model of commitment in which (communicated) commitment has a direct impact on the manifestness of an assumption. In particular, assumptions conveyed with a high level of commitment are more manifest to the hearer, than assumptions conveyed with a weaker level of commitment, as predicted in Hypothesis 3 (hearer commitment impacts upon how information is remembered by an individual).

Furthermore, although our statistical models are unable to tease out the intermediate commitment category (medium) from the other two, the expected trend can be observed between them. These promising results call for further investigation of the theoretically motivated graded structure of strength in the hearer's cognitive environment. In addition, they also call for an extension of the experimental paradigm to tap into the equally theoretically motivated effect that the source's reliability is predicted to have on strength.

To conclude, these results appear to open interesting perspectives in the study of commitment phenomena both on a theoretical level by linking commitment to manifestness in the cognitive environment; and on a methodological level by providing a new experimental design to investigate commitment assignment phenomena in pragmatics. Incidentally, they also open a new testing ground for the very central notion of strength within Relevance Theory.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: Material: https://figshare.com/s/8b348e17abb03598345b, Datasets: https://figshare.com/s/d010967de38bd88d3486, R Scripts: https://figshare.com/s/f52a4b8ce48aa2852833.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Cambridge University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

The experiments presented in this paper were carried out as part of KB's project under the supervision of DM. All authors have contributed to the discussion, preparation, and revision of the manuscript.

Funding

KB benefitted from a DOC.Mobility grant to study at Cambridge University for her project entitled “Are you committed? A pragmatic account of commitment” (P1FRP1_155140/2).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^During the elaboration of the experimental studies presented here, the first author discussed the design extensively with Napoleon Katsos. We wish to acknowledge the rich feedback and insights provided in the welcoming atmosphere of his lab. We would also want to thank two reviewers for providing us with very constructive comments. The usual disclaimers remain.

2. ^In this contribution we will refer to a female speaker, whereas the hearer will be assumed to be male.

3. ^“Prise en charge”, in French.

4. ^The degree of speaker commitment is only one of several dimensions that the Epistemic Vigilance filter controls for. Speaker benevolence, or informational coherence would also enter the evaluation process for instance.

5. ^As we will see later on and following up on the ideas put forward by Sperber et al. (2010) our model takes strength to be a function of the certainty of the communicated content and of the reliability of its source.

6. ^In a footnote linked to this discussion, Sperber and Wilson (2015) explain that the notion of salience mentioned here is equivalent to that of ‘accessibility' which is used extensively in relevance-theoretic accounts.

7. ^Obviously, a speaker can also report some other locutor's speech, in which case it is the latter person's reliability that will be factored in when determining the degree of commitment.

8. ^Accessibility is defined as “the ease or difficulty with which an assumption can be retrieved (from memory) or constructed (on the basis of the clues in the stimulus currently being processed)” (Carston, 2002; p. 376).

9. ^The research leading to these experiments was funded by a Doc. Mobility fellowship from the Swiss National Science Foundation to the first author for the project entitled “Are you committed? A pragmatic account of commitment”.

10. ^All the linguistic markers of certainty used in this experiment were tested and assessed by 41 native English speaking Mechanical Turk workers (from the United States) aged 18 to 61 (23 female, 18 male), in a pre-test (see Boulat, 2018).

11. ^Mturk is a crowdsourcing internet market which enables its users to post Human Intelligence Tasks (HITS) in exchange for money.

12. ^In order to take part in this experimental study, workers needed to be native English speakers, aged from 18 to 60 and to live in the United States. When these conditions were not met, workers were automatically redirected to the end of the survey.

13. ^The words in the 30 statements were obtained from Kucera and Francis (1967) list providing the 2200 most frequent English words (see http://www.auburn.edu/~nunnath/engl6240/kucera67.html), following Birch and Garnsey (1995), Chan and McDermott (2007) as well as Haist et al. (1992) studies on memory and recognition.

14. ^The total of number of syllables takes into account the linguistic marker and the statement (e.g., Obviously, the old lady saw a plane = 10 syllables).

References

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B., and Walker, S. (2015). Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1–48. doi: 10.18637/jss.v067.i01

Bernard, S., Hugo, M., and Fabrice, C. (2012). The power of well-connected arguments: early sensitivity to the connective because. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 111, 128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.07003

Beyssade, C., and Marandin, J. M. (2009). Commitment: attitude propositionnelle ou attitude dialogique? La notion de Prise en Charge en Linguistique, ed. D. Coltier, P. Dendale and Philippe de Brabanter. Langue Française 162. Paris: Editions Armand Colin, p. 89–107.

Birch, S. L., and Garnsey, S. M. (1995). The effect of focus on memory for words in sentences. J. Mem. Lang. 34, 232–267. doi: 10.1006./jmla.1995.1011

Birkelund, M., Henning, N., and Rita, T. (eds)., (2009). La Polyphonie Linguistique. Langue Française 164. Paris: Editions Armand Colin.

Bonalumi, F., Scott-Phillips, T., Tacha, J., and Heintz, C. (2020). Commitment and communication: are we committed to what we mean, or what we say? Lang. Cogn. 12, 360–384. doi: 10.1017/langcog.2020.2

Boulat, K. (2015). “Hearer-oriented processes of strength assignment: a pragmatic model of commitment,” Evidentiality and the Semantics Pragmatics Interface. eds B. Cornillie and J. I. Marín Arrese. [BJL 29], p. 19-39.

Boulat, K. (2018). It's All About Strength: Testing A Pragmatic Model of Commitment. PhD Dissertation, MS. University of Fribourg, Fribourg.

Boulat, K., and Maillat, M. (2017). She said you said I saw it with my own eyes: a pragmatic account of commitment. Formal Models in the Study of Language: Applications in Interdisciplinary Contexts, eds J. Blochowiak, S. Durrlemann, C. Laenzlinger, 261-279. Paris: Springer.

Boulat, K., and Maillat, M. (2018). “Be committed to your premises, or face the consequences: a pragmatic analysis of commitment inferences,” in Argumentation and Inference: Proceedings of the 2nd European Conference on Argumentation, eds Oswald, S. and Maillat, D. Fribourg (London: College Publications) 2017, 79–92.

Carston, R. (2002). Thoughts and utterances: The pragmatics of explicit communication. Oxford: Blackwell. doi: 10.1002./9780470754603

Chan, J. C.K., and McDermott, K. B. (2007). The testing effect in recognition memory: A dual process account. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 33, 431–437. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.33.2.431

Clark, B. (2013). Relevance theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017./CBO9781139034104

Coltier, D., Patrick, D., and Philippe, d. e. B. (eds)., (2009). La notion de prise en charge en linguistique. Langue Française. (162). Paris: Armand Colin. doi: 10.3917./lf.162.0003

Cornillie, B., and Delbecque, D. (2008). Speaker commitment: back to the speaker. Evidence from Spanish alternations. Commitment, ed. by Philippe De Brabanter and Patrick Dendale, 37-62. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. doi: 10.1075./bjl.22.03cor

Culioli, A. (1971). Modalité. Encyclopédie Alpha, t. 10. Paris, Grange Batelière et Novare, Istitutogeografico de Agostini. 4031.

De Saussure, L. (2008). L'engagement comme notion cognitive associée au destinataire. L'analisi linguistica e letteraria 16, 475–488.

De Saussure, L. (2011). Discourse analysis, cognition and evidentials. Disco. Stud. 13, 781–788. doi: 10.1177/1461445611421360b

De Saussure L. and Oswald, S.. (2009). Argumentation et engagement du locuteur: Pour un point de vue subjectiviste. Nouveaux Cahier de Linguistique Française 29, 215–243.

Dendale, P., and Coltier, D. (2011). La prise en charge énonciative: Etudes théoriques et empiriques. Paris, Bruxelles: De Boeck, Duculot.

Ditman, T., Tad, T. B., Caroline, R. M., and Holly, A. T. (2010). Simulating an enactment effect: pronouns guide action simulation during narrative comprehension. Cognition 115, 172–178. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.10014

Falkenberg, G. (1990). Searle on sincerity. Speech Acts, Meaning, and Intentions: Critical Approaches to the Philosophy of John R. Searle, ed. Armin Burkhardt (Berlin, New-York: Walter de Gruyter), p. 129-146. doi: 10.1515./9783110859485.129

Fraundorf, S. H., Duane, G. W., and Aaron, S. B. (2010). (2010). Recognition memory reveals just how CONTRASTIVE contrastive accenting really is. J. Mem. Lang. 63, 367–386. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.06004

Haist, F., Arthur, P. S., and Larry, R. S. (1992). On the relationship between recall and recognition. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 18, 691–702. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.18.4.691

Hart, C. (2011). Legitimizing assertions and the logico-rhetorical module: evidence and epistemic vigilance in media discourse on immigration. Disco. Stud. 13, 751–769. doi: 10.1177/1461445611421360

Ifantidou, E. (2000). Procedural encoding of explicatures by the Modern Greek particle taha. Pragmatic Markers and Propositional Attitude, ed A. Gisle and G. Thorstein (Amsterdam, Philadelphia: John Benjamins), p. 119-144.

Ifantidou, E. (2001). Evidentials and Relevance. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Iten, C. (2005). Linguistic Meaning, Truth Conditions and Relevance: The Case of Concessives. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

Jaswal Vikram, K., and Lauren, S. M. (2007). Turning believers into skeptics: 3-years-olds' sensitivity to cues to speaker credibility. J. Cogni. Develop. 8, 263–283. doi: 10.1080./15248370701446392

Katriel, T., and Dascal, M. (1989). Speaker's commitment and involvement in discourse. From Sign to Text: A Semiotic View of Communication, ed. T. Yishai. (Amsterdam, Philadelphia: John Benjamins). p. 275-95.

Kucera, H., and Francis, N. F. (1967). Computational analysis of present day American English. Providence, RI: Brown University Press. Available online at: http://www.auburn.edu/~nunnath/engl6240/kucera67.html (accessed September 26, 2017).

Marín-Arrese, J. I. (2011). Epistemic legitimizing strategies: commitment and accountability in discourse. Disco. Stud. 13, 789–797. doi: 10.1177/1461445611421360c

Mascaro, O., and Sperber, D. (2009). The moral, epistemic, and mindreading components of children's vigilance toward deception. Cognition 112, 367–380. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.05012

Mazzarella, D. (2013). “Optimal relevance” as a pragmatic criterion: the role of epistemic vigilance. UCL Work. Pap. Linguist. 25, 20–45.

Mazzarella, D., Robert, R., Ira, N., and Hugo, M. (2018). Saying, presupposing and implicating: how pragmatics modulates commitment. J. Pragm. 133, 15–27. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.05009

Mercier, H., Bernard, S., and Clément, F. (2014). Early sensitivity to arguments: how pre-schoolers weight circular arguments. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 3, 11. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.11011

Mercier, H., and Sperber, D. (2017). The Enigma of Reason. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Mobayyen, F., and de Almeida, R. (2005). The influence of semantic and morphological complexity of verbs on sentence recall: implications for the nature of conceptual representation and category-specific deficits. Brain and Cognition 58, 168–171. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.08039

Moeschler, J. (2013). Is a speaker-based pragmatics possible? Or how can a hearer infer a speaker's commitment? J. Prag. 48, 84–97. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.11019

Moore, C., and Davidge, J. (1989). The development of mental terms: pragmatics or semantics? J. Child Lang. 16, 633–641. doi: 10.1017/S030500090001076X

Morency, P., Oswald, S., and de Saussure, L. (2008). Explicitness, implicitness and commitment attribution: a cognitive pragmatic approach. Commitment, eds B. De Philippe and D. Patrick (Amsterdam: John Benjamins). p. 197–220.

Nølke, H. (2001). La ScaPoLine 2001. Version révisée de la théorie scandinave de la polyphonie linguistique. Polyphonie: linguistique et littéraire 3, 44–65.

Nølke, H., Kjersti, F., and Coco, N. (2004). ScaPoLine: La théorie scandinave de la polyphonie linguistique. Paris: Kimé.

Oswald, S. (2011). From interpretation to consent: arguments, beliefs and meaning. Disc. Stud. 13, 806–814. doi: 10.1177/1461445611421360e

Papafragou, A. (2000a). Modality: Issues in the Semantics-Pragmatics Interface. Oxford: Elsevier Science.

Papafragou, A. (2000b). On speech-act modality. J. Pragm. 32, 519–538. doi: 10.1016/S0378-2166(99)00062-4

Papafragou, A. (2006). Epistemic modality and truth conditions. Lingua 116, 1688–1702. doi: 10.1016/j.lingua.05009

R Core Team. (2016). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria. Retrieved from https://www.R-project.org/.

Sabbagh, M. A., and Baldwin, D. (2001). Learning words from knowledgeable versus ignorant speakers: links between preschoolers' theory of mind and semantic development. Child Development 72, 1054–1070. doi: 10.1111./1467-8624.00334

Searle, J. R. (1979). Expression and Meaning: Studies in the Theory of Speech Acts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Spalek, K., Nicole, G., and Isabell, W. (2014). Not only the apples: focus sensitive particles improve memory for information-structural alternatives. J. Mem. Lang. 70, 68–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.09001

Sperber, D., Clément, F., Heintz, C., Mascaro, O., Mercier, H., Origgi, et al. (2010). Epistemic vigilance. Mind Lang. 25, 359–393. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0017.2010.01394.x

Sperber, D., and Wilson, W. (1987). Précis of relevance: communication and cognition. Behav. Brain Sci. 10, 697–710. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X00055345

Sperber, D., and Wilson, W. (1987/1995). Relevance: Communication and Cognition. (2nd edition). Malden, Mass: Blackwell Publ.

Traxler, M. J. (2012). Introduction to Psycholinguistics: Understanding Language Science. Wiley-Blackwell: Malden, Oxford.

Vullioud, C., Clément, F., Scott-Phillips, T., and Mercier, H. (2017). Confidence as an expression of commitment: why misplaced expressions of confidence backfire. Evol. Human Behav. 38, 9-17. doi: 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.06002

Walton, D. (1992). The Place of Emotion in Argument. University Park Pa.: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

Walton, D. (1993). Commitment, types of dialogue, and fallacies. Inform. Logic 14, 93–103. doi: 10.22329/il.v14i2.2532

Walton, D. (1996). Arguments from Ignorance. University Park Pa.: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

Walton, D. (1997). Appeal to pity: Argumentum ad Misericordiam. New-York: State University of New York Press.

Walton, D. (2008b). Witness Testimony Evidence: Argumentation, Artificial Intelligence and Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Keywords: commitment, relevance theory, strength, experimental pragmatics, certainty, epistemic vigilance, evidentiality

Citation: Boulat K and Maillat D (2023) Strength is relevant: experimental evidence of strength as a marker of commitment. Front. Commun. 8:1176845. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2023.1176845

Received: 28 February 2023; Accepted: 09 June 2023;

Published: 06 July 2023.

Edited by:

Stavros Assimakopoulos, University of Malta, MaltaReviewed by:

Agnieszka Piskorska, University of Warsaw, PolandRyoko Sasamoto, Dublin City University, Ireland

Copyright © 2023 Boulat and Maillat. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Didier Maillat, ZGlkaWVyLm1haWxsYXRAdW5pZnIuY2g=

Kira Boulat

Kira Boulat Didier Maillat

Didier Maillat