- 1Department of Modern Languages, Literatures and Cultures of the University “G. d'Annunzio”, Chieti, Italy

- 2Department of Humanistic Studies, University of Roma Tre, Rome, Italy

Since the so-called phase one of the Coronavirus pandemic, media professionals have shown great attention to communication about the epidemic, so much so that a “glottology of COVID-19” has even been advocated to reflect on war metaphors referring to the disease. Despite media solicitations, however, reflection on communication at the time of COVID was not immediately the subject of linguistic analysis, at least in the Italian context. However, the issue of the relationship between language and culture, society, and thought has recently been explored in the face of the limitation of only formal analyses on language at the time of COVID. In the first stage, it quickly became apparent that the people in charge of institutional communication were used to talking mostly with experts on public health problems or research results, without the necessary training to modulate their language according to the degree of specialization of the audience. Instead, it is currently possible to detect an improvement in communication skills, and to observe the emergence of opposing factions with respect to the new resources of both preventive and therapeutic medicine, respectively the pro-vax and no-vax movements. These issues have been the focus of many Italian TV talk shows, such as the program “Non è l'Arena.” In the episode of 9/25/21, which is the subject of this article, the positions expressed in favor of one argument or the other would seem to adopt different mechanisms for managing the epistemic mode of certainty/uncertainty, such as semantic-syntactic and rhetorical-pragmatic devices, as well as conversational moves. This paper is aimed at describing the management of certainty/uncertainty in a media context through the qualitative fine-grained analysis of the interactional exchanges between host and representatives of opposite views in the dual theoretical framework of classical rhetoric and conversational analysis (CA), which, although starting from different scientific paths, share the vision of the centrality of speech in human action. The CA analysis indicated that, whilst the interviewer maintained a neutral stance in conducting the interview, he showed a position of affiliation toward the doctor who recommended therapies not in line with the Italian medical guidelines. This was evident through the space provided to him to explain his expertise, as well as through the repetition and emphasis of the evaluative elements expressed. The rhetorical analysis, focusing on the participants' ethos, reveals that the interviewer deliberately intervened in the construction of the epistemic authority of the representatives of the two positions. The rhetorical analysis, focusing on the ethos of the three participants in the interaction, shed light on selected strategies and argumentative chains used to gain credibility and to prevail in the discussion. The linguistic-rhetorical mechanisms used do not pertain to the field of dialectical discussion and aim at a direct attack on the opponent's thesis. Nevertheless, the clash remained balanced without any epistemic authority overpowering the other: both the rhetorical and conversation analyses demonstrate a polarized dialogue, wherein the two sides are portrayed as representatives of two distinct and incompatible perspectives.

1. Introductory remarks

This study will analyse, from both a rhetorical research and conversation analysis (CA) perspective, how the degree of certainty of scientific knowledge is made to descend from the epistemic authority of the person who expressed it, according to what was called the sophisma auctoritatis by the scholastics, and which Cicero summarized in the formula ipse dixit.

The cultural and historical context taken into consideration is that of the recent COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. Our country was the first in the West to cope with the spread of the virus, and the National Health System was faced with an emergency for which it had no resources (Fanelli and Piazza, 2020). In this dramatic situation, the choice of the Italian government was to make legislative interventions aimed at containing the pandemic based on the indications of a committee of experts, known as the Scientific Technical Committee (STC). In the first months of the spread of the contagion, the choices to counter its advance were mainly oriented toward the containment of contacts, with the forced closure of unnecessary commercial activities and the restriction of population movement. Especially during the initial phase of the pandemic, due to the absence of therapies and vaccines, the voice of experts' stimulated very conflicting discussions and debates on the therapies to be used to combat the virus. The media gave space to virologists, epidemiologists, immunologists, and a myriad of experts who, with sometimes problematic results in terms of communication, quickly moved from therapeutic practice and research to the role of communicators (Orletti, 2022a). Analogously to what occurred in the early 2000s in the case of SARS, the viral pandemic spread parallel to a worldwide “information epidemic” or “infodemic” (Rothkopf, 2003), which has seen an alternation of scientifically well-founded news and fake news about COVID-19 adversely impacting healthy attitudes and behaviors and further diminishing trust in science, institutions, and traditional media (Scardigno et al., 2023).

In Italy, as infection increased and the forces in the medical field dwindled due to the spread of the virus even among practitioners, the regional authorities recalled retired medical personnel and adopted the intervention of doctors without specific training in epidemiology to counter the advancing epidemic. In the absence of a certain orientation supported by science regarding therapeutic indications, the role of expert was therefore filled by doctors who are specialists in the most varied fields, and the most varied—at times even debatable—treatments were put forward in the first phase of the pandemic. A distinction emerged between those who are experts by institutional decision, such as the members of the Scientific Technical Committee, or by a specific cursus honorum, and those who are experts by ability. This distinction had already been outlined by Eyal (2013, p. 869) according to whom we can speak of “experts” and “expertise”, namely of “professionals recognized as being ‘experts’ and professionals who are not (necessarily) recognized as being ‘experts’ but who have the capacity to do so”. Defining what and how much expertise makes a professional an expert has become one of the problems faced not only by the population but also by the authorities themselves in the face of the virus outbreak.

In our study, based on the analysis of an interaction fragment from the talk show “Non è l'arena”, we will investigate the construction of the identity of an interaction participant as someone who has the expertise to deal with and treat cases of contagion, although he is not necessarily an expert, i.e., he is not a virologist nor a member of the Italian STC. We will see how interactants use a wide variety of attributes, ranging from university education to family culture, to define one of the participants as a suitable professional to treat cases of COVID 2019 infection, and to consider the therapies he has prescribed as valid. In line with the theoretical framework of CA adopted in this first part of the article, we will illustrate how within the interactional exchange his “expertise” is shaped and how his presence in a mediatic public debate between “experts” on valid COVID treatments is progressively negotiated and legitimized (sections 2, 3, 4). In the second part (sections 5, 6, 7, 8, 9), we will propose a complementary interpretation of the strategies employed by the participants to build credibility and gain the audience's trust, focusing on the rhetorical concept of ethos, in Aristotelian terms, the persuasiveness of a person's character (Aristotle, 1959; Rhetoric 1356a—henceforth Rhet.). This perspective of analysis appears most useful in the cultural and historical context taken into consideration here, given the persuasive force of the speaker's ethos in situations of uncertainty. As Aristotle stated, the character is persuasive if the speech is presented in such a way that the speaker appears credible, because “We believe good men more fully and more readily than others: this is true generally whatever the question is, and absolutely true where exact certainty is impossible and opinions are divided” (Rhet. 1356a).

2. Conversation analysis and identity

In all our interactions, we classify ourselves and others into social categories: This activity allows us to relate participants to the actions performed, to give meaning and significance to what is happening based on practical reasoning criteria. Sacks focused the attention of the early CA on this phenomenon and developed the so-called “membership categorization analysis” in the 1960s to study the principles and methods that participants use to socially categorize themselves, as well as others, and any element of reality through language. This continuous categorization activity leads people to place elements of reality into “collections of things” such as, for example the category of “family” or that of “young” or “old.” Belonging to a certain category results in the possession of a certain set of traits that Sacks calls “category-bound features”, which are common to all members of the category. Alongside this more formal and programmatic approach in dealing with the theme of identity construction by means of linguistic choices, a strand that will develop with a life of its own beyond the analysis of interaction (Hester and Eglin, 1997), Sacks shows how identities emerge through interactional sequences, that is they are “occasioned” by these and at the same time influence the development of the interaction in progress; in other words, they have “procedural consequentiality” on what takes place (Schegloff, 1992). An example of this way of conceiving identity can be found in a lecture on 11 March by Sacks (1992). Here, the sociologist shows how in the way food is offered and in the insistence used to respond to the recipient's obstinate refusal of the offer, the identity of the recipient is delineated as a fragile person in need of attention and care, a person who is elderly or otherwise unable to take care of himself. This focus on identity as constructed through the course of interaction, in which participants select from the external context only what they consider relevant, will return later in Schegloff (1987, 1991, 1992) devoted to the relationship between interaction and the external social context. An attempt to synthesize ethnomethodological and conversationalist perspectives in identity analysis is proposed by Antaki and Widdicombe (1998, p. 3). The authors elaborate a list of five tenets that come into play while analyzing the identity of a subject, be it the speaker, or the person being addressed:

- “for a person to ‘have an identity’- whether he or she is the person speaking, being spoken to, or being spoken about- is to be cast into a category with associated characteristics or features;

- such casting is indexical or occasioned;

- it makes relevant the identity to the interactional business going on;

- the force of ‘having an identity’ is in its consequentiality in the interaction;

- all this is visible in people's exploitation of the structures of conversation.”

As the aforementioned authors themselves point out, all these tenets are not always in place in every analysis, but in their totality, they reflect the way CA and ethnomethodology deal with the notion of social identity not as something derived from external reality but as a product of interaction.

3. The analyzed extract

The analyzed extract is from the Italian programme “Non è l'arena”, hosted by Massimo Giletti, which deals with current topics through news reports and a talk show with various guests. The debate during the programme is generally oriented toward the presentation of often strongly conflicting positions. There is a tendency to confront supporters of opposing stances and the broadcast unfolds as a verbal duel between the contenders.

The broadcast under analysis, which took place on 29 September 2021, deals with the controversy and clashes of opinion on effective therapies to combat COVID-19 infection.

The guests invited to the television studio are Dr. Stramezzi, a doctor who has no specific training in the field of epidemiology, but has, on his side, the reputation of having treated thousands of people, Dr. Pregliasco, considered an authority in the field, and Senator Vittorio Sgarbi, art historian and art critic, known for his polemical trait in debates, but who, as he himself will state, has no expertise on the subject under discussion.

The extract is transcribed using Jefferson notation (Jefferson, 2004), which is the system universally used by those who follow a conversational approach.

4. Analysis

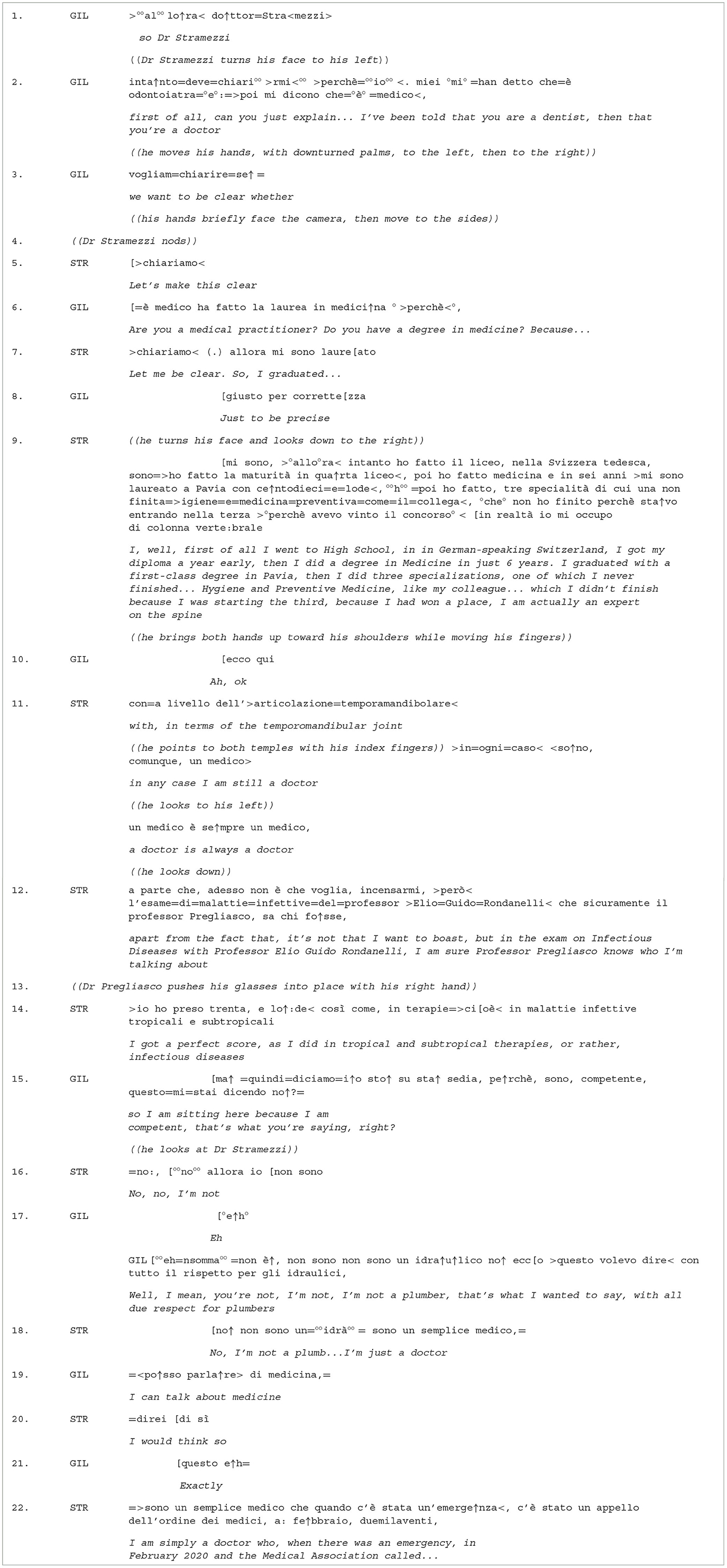

4.1. The meaning of being an “expert”: the role of educational career in Stramezzi's words

In Extract 1, from the very first turns, the presenter makes Dr. Stramezzi's professional identity relevant by asking him to clarify whether he is a doctor or a dentist. For readers unfamiliar with the Italian system, it is worth mentioning that until 1980, there was no specific training path differentiating the profession of doctor from that of dentist. A person becomes a dentist through specialization, after obtaining a degree in medicine, and therefore sharing the same medical degree with other medical specializations. Currently, however, some dentists have a medical degree and some dentists do not as there is a specific degree in dentistry and it is not necessary to graduate first in medicine. Dr. Stramezzi accedes to the request for clarification by beginning with the formulation (Garfinkel and Sacks, 1970; Heritage and Watson, 1979, 1980; Orletti, 1983, 2000; Fele, 2009) let's make it clear which defines the activity he is about to perform1.

The answer to his training retraces the path followed since high school. The details provided go far beyond the presenter's question by emphasizing the quality of the education received and the doctor's achievements. The education took place on time or even ahead of schedule, and the score achieved was the highest. The high school was completed in 4 years (not 5 years as in Italian high schools) at a school in German-speaking Switzerland. University was completed in the allotted 6 years. There were even three specializations that the doctor sought to achieve. And before these, he obtained a degree in Medicine with honors.

In the interviewee's statements, there is a lot of implicit information to which he seems to refer, to reinforce the idea of a distinguished training course. The non-ordinary character of the training course must be derived by the listener based on the knowledge of the world. The common-sense knowledge shared by the majority of the audience includes the fact that the school in the German-speaking part of Switzerland is synonymous with seriousness and social exclusivity, that one does not generally graduate in medicine in due time, and that being admitted to one specialization is extremely difficult, let alone three. The doctor, however, does not make this knowledge explicit and defers to the ability of the audience to activate it in its own minds. He merely expresses a list of objective facts, aiming at identifying himself as an expert by resorting to the elements, the type of studies, their duration, the marks obtained, and specializations that the external social context offers him for this purpose and that have a documentary, not subjective, character.

The use of external contextual factors, in Mehan (1991) terms “distal circumstances”, is made relevant by the presenter's initial question, which transforms these factors from external elements to elements that guide the interaction and activities of the members, i.e., they become “members' phenomena.”

The doctor then states to the presenter that he deals with the spinal column at the temporomandibular level and that he is in any case a doctor. He then adds, to reaffirm his expertise in the field of infectious diseases, that he has passed an examination on this subject with a distinguished scholar, and that he did so with honors.

He invokes confirmation from his “opponent”, Pregliasco, on the quality of the examining professor, but the virologist does not join the discussion.

The conductor takes up the interviewee's words with a summarizing formulation (Orletti, 1983, 2000), expressed in the form of a request for confirmation to the interlocutor, in which Dr. Stramezzi's competence is reiterated.

The conductor and interviewee co-construct the latter's identity as a doctor, paradoxically opposed to that of a plumber, who would have no right to intervene in therapeutic issues. The paradoxical comparison is introduced by the presenter and serves to dismiss and not answer what seems to us to be an underlying question: can any category of doctor, regardless of their specialisation, be considered an expert in the fight against COVID?

Stramezzi responds to this unspoken question by recalling that in February 2020, at the height of the care crisis, the regional medical authorities called for the intervention of all doctors, whatever their specialisation.

We will see later in Fragment No. 2, how in the confrontation with Pregliasco, it is not so much Stramezzi's identity as an expert that is being questioned, but the effectiveness of his therapies that are not provided by national guidelines.

4.2. Expertise at the test bench

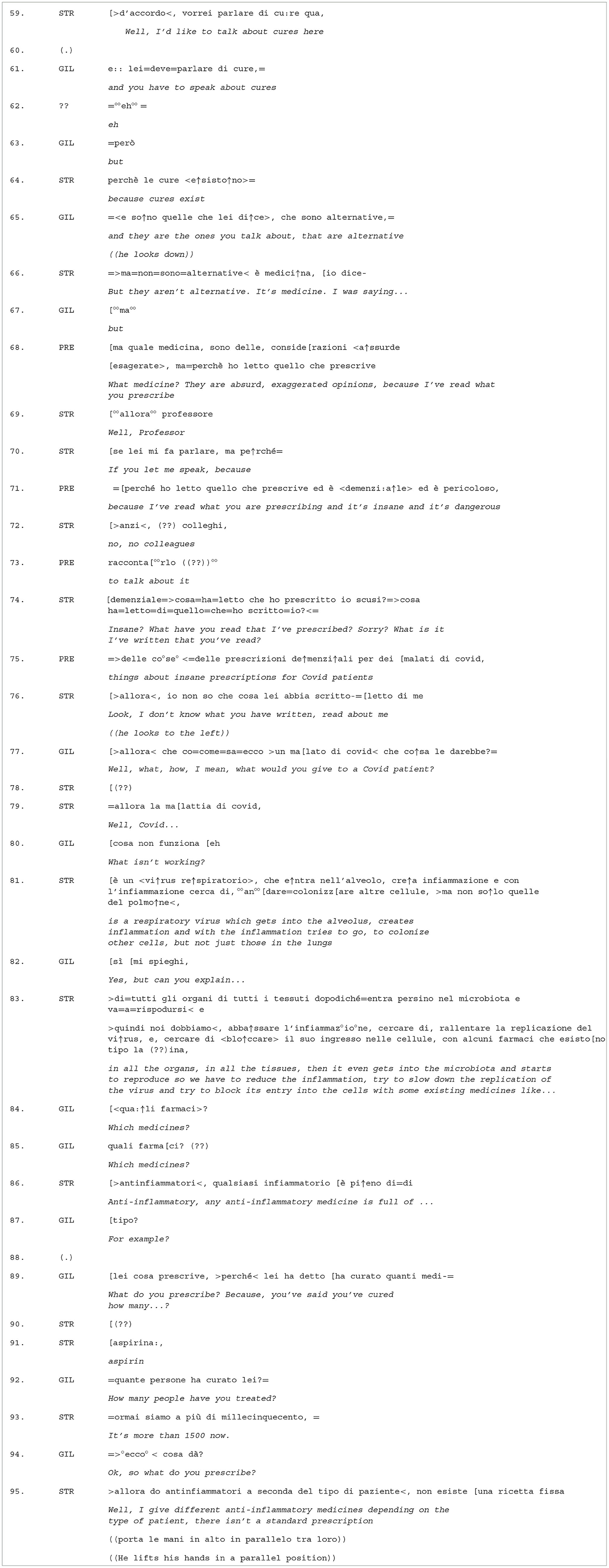

After a heated exchange with the doctor opposing him in the transmission, Professor Pregliasco, on the function of Ffp2 masks, Dr. Stramezzi shifted the topic of discussion to the therapies to be used in the case of COVID patients.

It should be recalled that at the time of the interview, the national guidelines were limited to prescribing, in the event of infection with fever, the use of Tachipirin, a drug based on an antipyretic, paracetamol, and watchful waiting, i.e., monitoring the evolution of the disease. Prescribing drugs, stating the existence of a possible treatment for COVID-19 infection, places the doctor who does so outside official medicine. But this is Dr Stramezzi's strong point, in his view, and this is where he shifts the focus. The topic is introduced, quite unusually in a televised debate2, not by the presenter but by the interviewee, who on line 59 (Extract 2) states “I would like to talk about cures here”. The presenter expresses the acceptance of the topic proposal by means of a deontic modality (you have to speak of treatments) reinforcing the action.

The reaction of the conductor, who reiterates that the action proposed by the interviewee is necessary, allows him to take over the conduct of the interview again. Stramezzi enacts insubordination (Leonardi and Viaro, 1983; Orletti, 2000) which could undermine the conductor's directing power over the interaction but which is minimized by the conductor's reprise which qualifies it as a required action.

While broadly following the structure of an asymmetrical institutional interaction, the host–respondent interaction often requires negotiation of interactional power (see Boden and Zimmerman, 1991; Drew and Heritage, 1992; Orletti, 2000; Orletti and Caronia, 2019). Certain critical moves, such as introducing the topic of discourse, or the expression of an evaluation, may require the joint action of the parties. We can observe in line 92 that the evaluation is a “sequential product”, achieved through the moves of the interviewee and interviewer. Giletti asks the interviewee how many people he has treated. The quantitatively relevant answer, 1,500 people, is by itself an evaluation. The presenter comments on it with the discourse marker “ecco”, which has in Italian, in face-to-face interaction, the meaning of confirmation and acceptance. The use of ecco in this case can be likened to what Poggi et al. (2011) consider a confirmation signal. As before in line 21 of fragment 1 (questo è/Exactly), Giletti seems to move away from the neutralization stance (Clayman, 1988, 1992; Greatbatch, 1988; Orletti, 2000; Clayman and Heritage, 2002) proper to the presenter. However, he manages to maintain a kind of neutrality through the adoption of these confirmation signals, which, unlike actual agreement, are more an acceptance of the transmitted information than the expression of an opinion.

In the host's question, in the use of the verb curare, there is a semantic finesse since in Italian curare can have a telic or non-telic value (Vendler, 1957). In this meaning, with the past verb form, the interplay with the value of completeness given by the verbal tense makes curare take on a telic value, whereby curare has an endpoint, i.e., the healing, or the regression of the illness at least. Giletti asks the interviewee how many people he has treated. According to this interpretation, Giletti by means of his question asks how many have been treated and achieved the goal of overcoming the COVID infection.

The attitude of neutrality returns in the concluding phase of the broadcast, in which the impossibility of formulating a definitive opinion on the question of cures is reiterated with Giletti's expression “we're not getting out of it” (non ne usciamo).

We observed that, in turn, Stramezzi alters the asymmetrical structure of the journalistic interview (line 92, Extract 2) according to which it is the interviewer who asks questions and who introduces themes (Orletti, 2000) by taking the floor without being questioned and deciding what to talk about. The presenter makes the theme proposal his own and brings the interaction back to order.

It has to be said that the conduct of the presenter is perfectly in line with what is described in the CA literature on journalistic interaction (Clayman, 1988, 1992; Greatbatch, 1988; Orletti, 2000; Clayman and Heritage, 2002), especially for that neutralistic stance, which the journalist must have in the interaction with regard to the transmitted content.

In close confrontation between Stramezzi and Pregliasco on therapeutic choices in which very strong adjectives such as “insane” and “dangerous” are expressed to comment on the treatments of the dentist-doctor, Giletti never takes a position.

He performs his task as an elicitor of information through a succession of explicit, direct questions, which give the doctor the opportunity to explain and describe his therapies, that are not in line with the official guidelines. The questions are pressing and require increasingly specific information.

Assessments of the effectiveness or otherwise of the proposed treatments are lacking and the comparison is left to the two doctors. The interviewer manifests the caution in expressing personal points of view and evaluations which is typical of broadcast interviews. This type of caution was defined by Clayman (1988, 1992), in a reinterpretation of Goffman's concept, as the so-called neutrality footing, both because neutrality is a trait required by the professional deontology of journalism, and because, as it has been suggested in the CA literature on broadcast interviews, the interviewer is not the real recipient of the elicited information but acts as an interface between the audience and the interviewee.

As it has been pointed out by the cited authors, neutralistic stance is achieved through the joint effort of interviewer and interviewee; it is a joint interactional achievement.

In the limited cases in which an evaluation emerges, i.e., at line 16, Giletti activates in the production format roles that see him neither as author nor principal, according to Goffman (1981) distinction. Here, he becomes the animator of the words spoken by Stramezzi, who turns out to be the actual author and, in the final formulation, he reaffirms the role of Stramezzi as expert by quoting his words. The presenter does not take authoritative responsibility for the evaluation. While maintaining a neutral position, the presenter contributes to Dr. Stramezzi's expertise coming to the fore through the questions addressed to him, which disproportionately broadens the interactional space occupied by the doctor. It is evident that Dr. Stramezzi's expertise is a result of the combined efforts of the presenter and the interviewee (line 81–83). Although Stramezzi goes to great lengths in expounding elements demonstrating his expertise, this emerges thanks to the host's contribution, however, not through explicit stances or overtly positive judgements, but through the way the interview is conducted (the pressing of questions on this specific topic and affiliative moves). The confrontation is kept on an equal footing, without the emergence of epistemic authority and thus certainty. Stramezzi's construction of his role is realized by the doctor using technical medical language, with both specific and collateral terms (Serianni, 2005; Orletti and Iovino, 2018; Orletti, 2019)3. The adoption of the technical language variety should identify him as someone who knows; nevertheless, it is not enough to speak like a doctor to be recognized as competent in medicine.

The display of “expert” knowledge is continually challenged by the antagonist, Pregliasco, through negative and highly insulting judgements, formulated by referring to national and international guidelines, and not to the expertise of an individual physician. In addition to the ascertained invalidity with experimental studies of the proposed solutions, the heavy burden of side effects they have is emphasized.

There is a lack of objective data and testimonies in favor of the proposed therapeutic choices. Senator Sgarbi's intervention says nothing about Dr Stramezzi's qualities as a doctor but builds his identity as a cultured person, an art lover, and a member of an important family. All qualities relate to the man but not to the professional. It shall be seen in due course how, in terms of rhetoric, this pertains to some aspects of the individual's ethos, but adds nothing to his epistemic authority, and consequently the possibility of arriving at a certain solution.

5. The rhetorical focus: the doctors' ethos

We will now address the negotiation of the epistemic authority of Dr. Stramezzi, Dr. Pregliasco, and of the critic Sgarbi from a rhetorical point of view. Drawing on the classic Aristotelian perspective that considers language as a medium of persuasion (Rhet. 1354a 4–6), we will illustrate how the interviewees appeal to ethos in arguing their opposite thesis. The term ethos denotes the persuasiveness of a person's character (Rhet. 1356a) and differs from pathos (the persuasiveness of an appeal to emotions) and logos (the persuasiveness of logical arguments using examples or enthymemes). A pre-Aristotelian tradition, founded by Isocrates and predominantly adhered to by the Latin rhetoricians, defines ethos as the speaker's prior reputation and social standing, thereby contradicting the predominance of Aristotle's discursive construction of a self-image. Aristotle's concept of ethos pertains solely to the credibility built up by the speaker by means of what he says (dia tou logou, Rhet. 1356 a 1) and not by means of external factors such as his fame (doxa). In this respect, although starting from a different epistemological horizon, a common trait of rhetoric and CA could be found in the fact that the latter examines the self-representation of the speaker in the making of the discourse, while Aristotle's concept of ethos relates to the trustworthiness established by the speaker through their utterances.4

The notion of ethos has been borrowed and differently declined in various horizons of linguistic research, including among others the pragmatics-semantics (Ducrot, 1984), the discourse analysis (Maingueneau, 1999), and the pragma-dialectical approach (van Eemeren and Grootendorst, 2004). The perspective adopted herein, which intersects with that of CA, necessitates the selection of the conceptualization of ethos advanced by Amossy (1999, 2001), which integrates sociological and pragmatic insights into a rhetorical perspective derived from Aristotle and built upon Perelman's new rhetoric. Perelman believes that the study of argumentation has many sociological applications because the speaker's discourse is audience-oriented. To effectively develop his argumentation, the speaker must communicate in a language that is understood by his audience and link his argument to the theses accepted by his hearers. Therefore, the recovery of the social and extralinguistic dimension is present in the new Perelmanian rhetoric on the axiological and socio-cultural levels. It is using common knowledge and beliefs that the speaker attempts to make his audience share his views (Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca, 1958; Amossy, 1999, 2001). In this framework, ethos is then considered with reference to the self-image constructed by the speaker in the discourse, the image he or she makes of his or her audience, and the credibility that listeners attribute to him or her (Amossy, 1999).

6. Ethotic arguments

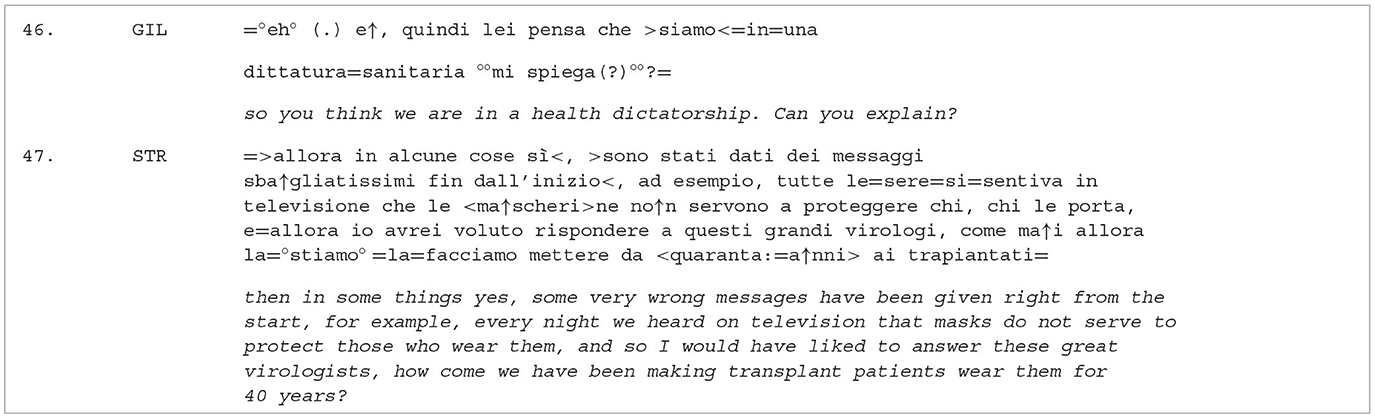

The image that the speaker tries to convey of himself to enhance his credibility by means of what he says (dia tou logou, Rhet. 1356a) is the most persuasive argument (Rhet. 1365a). Unlike the well-known virologist Pregliasco, Dr. Stramezzi is not acknowledged and will have to build his credibility in the space of an answer to the presenter's question. To reach this objective, he must display moral virtue (arete), skills, and practical wisdom regarding the subject matter (phronesis) along with goodwill toward the audience (eunoia) (Rhet. 1378a 6–19). The purpose of the third seems to correspond to the choice of an enallage of person, a figure of speech that consists of replacing a grammatical element with another—in this case, the pronoun “me” substituted by “us”—which has been classified among the figures of communion (TA 188). In saying “chiariamo/let's make this clear”, Dr. Stramezzi implements a strategy of complicity to make the audience actively participate in his exposition. His inclusive use of the pronoun “us” corresponds to a plural of modesty (Benveniste, 1946) and is intensified by Stramezzi's actio: he looks down and nods, showing benevolence to the interviewer and the audience since his very first utterance. Not even the use of specialist terminology, which recurs several times in the description of his brilliant educational background, disturbs this communion with the audience, thanks to gestural deixis that clarifies the meaning of unfamiliar medical terms [see lines 12 (Extract 2)]. Although his current field of intervention does not concern infectious diseases, Stramezzi reinforces his phronesis by resorting to a tautological diaphor (A doctor is always a doctor). Here, we have an improper extension of the principle of authority since his generic authority (to be a doctor) is reinforced by tautology while expanding its scope to a specialist context. Similarly, Stramezzi refers to himself by naming the authoritative professor by whom he has been taught and evaluated. At this point, he is interrupted by the presenter, who legitimizes Stramezzi's presence in this context by summarizing the doctor's words with a litotes (I'm not a plumber, that's what I wanted to say). Stramezzi then goes on to point out twice that he is merely a doctor who responded to an appeal from the nation in times of danger. While achieving a credibility effect by building his ethos in terms of arete as well through a constant note of submissive modesty, he is interrupted once again by the presenter. The latter asks Stramezzi to explain and substantiate the accusations leveled at the institutions' management of the pandemic during an earlier public event, in which the doctor spoke of a health dictatorship. Stramezzi downplays his judgement [in some things; s. line 46–47 (Extract 3)] and introduces the topic of false information given by virologists on television, according to whom masks serve no purpose in protecting the wearer.

Stramezzi gains ground in the discussion by means of an exemplum [Rhet. 1357b]: during the pandemic, the civilian population seems to have been governed by a concealed dictatorship, which appears, in some cases, to have passed on incorrect information, as in the case of “the ineffectiveness of the mask for those who wear it.” Stramezzi proceeds with inductive reasoning from a single case, but this is a false analogy, as he associates a complex and structured phenomenon such as health education with the issue of the dissemination of deliberately inaccurate information, amplified by the superlative (very wrong, sbagliatissime) and the adverbial locution (every night, tutte le sere). Moreover, it is precisely an inductive fallacy based on an undue generalization (a dicto simpliciter ad dictum secundum quid) believing that the use of the mask as it works for transplant recipients should have worked to protect against COVID, whereas the research then in progress was studying a whole series of differentiations from the specific case of COVID transmission. Additionally, this exemplum is uttered in the form of an apostrophe and a rhetorical interrogative (line 47, Extract 3), namely with two rhetorical figures that establish a communion with the audience (TA 168). At this point, the virologist Pregliasco, spokesperson for the institutions, is inevitably called upon and intervenes in the discussion.

7. Ad personam counterarguments

Pregliasco does not debate by opposing the false analogy with scientific information, exposing its character as an argumentative fallacy. The audience misses the complexity of the argument, and when Pregliasco replies that even for transplant recipients it is not totally effective against COVID, precisely by differentiating and not generalizing, he does not seem to have countered effectively. At various times during the broadcast, Pregliasco does not directly cite studies nor put forward data or any arguments pertaining to the logos. He merely counters with repeated ad personam hyperbolic arguments (lines 71, 75) and calls Stramezzi's treatments insane and dangerous. These were also refuted by ad ignorantiam argument: All treatments have not been tested and may have side effects, so the only therapy that can be given the benefit of the doubt is the one written in the guidelines because it has fewer side effects. It is an argumentative fallacy since the argument is not based on certainty but only on the fact that the thesis asserted applies and there is no evidence to the contrary. It is an argumentation used in interactions where the antagonist lacks argumentative fortitude but finds himself as if backed into a corner by not being able to prove the opposite (Lo Cascio, 2009, p. 320).

On several occasions, Pregliasco uses the weapon of personal attack to delegitimise his opponent in the eyes of the audience (s. lines 68, 71, 75; Extract 2). During the discussion, every part of Stramezzi's empirical and medical arguments is annihilated with words of outrage or exaggeration, but never with reference to direct medical studies, nor specific information. The strength of the setbacks inflicted on his opponent is justified by the fact that Stramezzi implicitly undermines the epistemic authority of the official guidelines by defending his treatments. But Pregliasco's counterargument is based on the constant recourse to authority: just generic “studies” or “guidelines” are mentioned, mostly conveyed through loci of quantity (all the studies are saying that…) (TA § 22). As Amossy (2010) reminds us, the ad hominem argument must appear veridical or at least supported by evidence; it must be related to the issue being debated, mentioned in the objectives of the debate, and—most of all—be built on the values and models of the community. All these criteria aim to justify the violence of the ethotic argument at every level: the logical level that condemns recourse to the passionate whose virulence covers and suffocates the rational; the dialectical level that blames the imposition of silence on the adversary, if not even his expulsion from dialogue; the interactive level that denounces the effort to make the other lose face; the linguistic level which deals appropriately with the insult and outrageous terms that society does not tolerate. If these criteria are not met, the ad hominem argument can even damage the speaker who uses it. This seems to happen to Pregliasco who is then invited by the presenter to give reasons for his criticism. It is noteworthy that the presenter does not ask Stramezzi to explain why his speech “would be” dangerous, but why it is. This choice of indicative mode betrays an alignment with the virologist's positions, just as shortly before he had assumed Stramezzi's role in legitimizing his epistemic authority. The presenter thus demonstrates that he continually intervenes in the construction of the ethos of the interviewees, with the precise intention of maintaining a kind of balance, without one doctor prevailing too much over the other.

8. The commentator's ethos

The notion of ethos sometimes refers to ethotic argumentation (Brinton, 1986; Walton, 1999), and it is often divided between “said ethos,” “shown ethos,” and “represented ethos,” the latter being the representation of the ethos of a speaker by commentators or members of the audience (Herman, 2022). In the television programme, the role of the commentator is assumed by Vittorio Sgarbi, who in offering a commentary on Stramezzi, simultaneously constructs his own ethos in his statements. He makes use, in his early statements, of the rhetorical figure of cleuasmos, a figure of speech whereby the speaker pretends to belittle himself to make himself better appreciated. It is a special form of irony (s. Lausberg § 583) or rather of subtle self-mockery that the speaker employs to make himself more sympathetic and trustworthy to his hearers. The verb chleuázo means indeed “to joke, to delight”: Using this figure, the speaker belittles himself, thus creating the impression of being a humble person of practical wisdom who knows well the limits of his own knowledge and intelligence as well as those of others. As noticed by Reboul (1994), cleuasmos belongs to the figures of ethos, because it shows a speaker who praises his own qualities in speech constructing his expertise. Sgarbi presents de facto a disadvantage as an advantage: he is not competent in infectious diseases, still he claims to be an expert connoisseur of Dr. Stramezzi. In reality, Stramezzi's ethos represented in Sgarbi's words does not coincide with Stramezzi's self-representation (the “said ethos”). The words with which Sgarbi describes Stramezzi do not refer to his excellent medical training (§ 4) nor the COVID cures of his patients. The represented ethos adds nothing on the level of phronesis, as Sgarbi merely describes Stramezzi as a man of great artistic sensitivity and, in mentioning the works of art in the doctor's valuable collection, constructs his own ethos as a art historian and art critic. In other words, Stramezzi's epistemic authority is not enhanced by Sgarbi's commentary. However, Sgarbi, by mentioning the doctor's valuable collection, implicitly alludes to the doctor's economic status. The audience thus concludes that Stramezzi did not treat so many patients out of mere economic interest. In this way, his disinterestedness makes him more popular with the audience: he shows benevolence (euonia) toward not only his patients, but toward the entire public.

Sgarbi's rhetorical strategy focuses only on ethotic arguments in support of Stramezzi, but without mentioning any direct ad rem arguments. Even if Stramezzi himself repeatedly invites others to talk about medicine, Sgarbi merely comments that Dr. Stramezzi has already won the public's sympathy, as evidenced by the text messages he received during the broadcast from people who would like Stramezzi to be their doctor. Sgarbi does not add any relevant data on Stramezzi's medical expertise in any part of his speech. He solely praises the doctor's abilities to appear credible and humorously suggests that Pregliasco should change his (rhetorical) strategy.

9. Conclusive remarks

However, it is perfectly legitimate to argue through authority if the argument is explicit, and it is known exactly who said what (Plantin, 2011), while it is not acceptable for this rational need for explanation to be replaced by the implicit insertion of authority into the discourse (just mentioning studies, guidelines in general), thus removing it from the possibility of refutation. To counter Stramezzi's theses, Pregliasco does not mention studies or concrete data; he only uses ad personam arguments that do not seem to work. Moreover, even when he counterargues Stramezzi's claims with data toward the conclusion of the interview, he is not convincing, or rather persuasive. This could be explained both through Pregliasco's wrong evaluation of the audience's common shared knowledge and values (endoxa), and with his lack of attention in building his credibility. He takes his epistemic authority for granted, without taking into consideration the necessary preliminary “agreement” with the audience (Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca, 1958, part II, § 15).

It is not self-evident that one comprehends the intricacy of the various kinds of masks or even the complexity of examining patients with bare hands due to the mode in which COVID is transmitted. In contrast, Stramezzi is always didactic both in words and gestures5. For example, when he says that he examines the patients with his bare hands and the virologist criticizes this mode of operation of his, he does not use concrete data to say that this is not risky but again resorts to the fallacious reasoning of the exemplum to generalize (I am still alive, so it is not dangerous to visit patients without gloves), and even of the etymology of the word surgeon, which derives precisely from the Greek chiros (hands). On closer inspection, he self-assigns himself the authority of a true surgeon, emphasized by the movement of his body that accompanies his statements with an appropriate actio (he shows and waves his hands in the air as if it were empirical evidence). Pregliasco strongly criticizes this mode of operation, fearing a dangerous risk, both for the doctor himself and for the patient, citing a fact: The COVID virus may be respiratory, but it remains active in the environment. However, his pressing and insufficiently explanatory counterargument does not seem to prevail in the discussion. Here is where Giletti has to intervene in bringing the credibility of the ethos of the two contenders up to par and prefers to balance the scales and concludes with the remark: “There is no way out” (non ne usciamo).

Considering the results of the rhetorical analysis and the CA on the ethos of the interviewees and the figure of the interviewer, it has emerged how the latter deliberately intervened in the construction of the epistemic authority of the representatives of the two positions. The CA analysis revealed that, while the presenter maintains a footing of neutrality in conducting the interview, a position of affiliation emerges in favor of Stramezzi. This occurs both through the space given to him to describe his expertise and in the repetition and underlining with summary formulations and repetitions of the evaluative elements expressed. But all this is not enough, the clash remains balanced without any epistemic authority emerging that overpowers the other and thus certainty. These findings are added to those of the analysis of the ethos of the three participants in the interaction, to identify—without any claim to exhaustiveness—the main strategies and argumentative chains used to gain credibility and to prevail in the discussion. The linguistic-rhetorical mechanisms used do not pertain to the field of dialectical discussion, but aim at a direct attack on the opponent's thesis; therefore, en dernière analyse both the rhetorical and conversation analyses and demonstrate a thoughtful polarization of the dialogue, wherein the two sides are portrayed as representatives of two incompatible perspectives with entirely disparate attributes.

COVID alternative home care treatments or official guideline therapies present a pertinent example to explore for the purpose of constructing ethos, as there is a continuous and fervent discourse from a variety of doctors and virologists, also related to the vexata quaestio of vaccinations and the diverse views concerning public health, safety, and individual freedom. A look at ethos as the most persuasive argument (Rhet. 1365a) may prove useful in similar media interactions, in a perspective that combines sociological and pragmatic insights into a rhetorical perspective derived from Aristotle and built upon Perelman's new rhetoric (Amossy, 2001) to explore persuasions strategy in the broader context of medical research communication.

The interaction examined here in the dual perspective of analysis is therefore paradigmatic of how in the media arena the scientific authority of Dr. Pregliasco—an academic virologist with clinical experience who occupied “the first place among the most cited experts” (Neresini et al., 2023)—must be accompanied by constant attention to building one's credibility with the public, to building one's role as an expert.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving human subjects in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent was not required for participation in the study or for the publication of any identifiable data/images included within the article.

Author contributions

FO is attributed Sections 2, 3, and 4, while MD'A Sections 5, 6, 7, and 8 and Sections 1 and 9 are in common. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was supported by the Department of Modern Languages, Literatures, and Cultures of the University G. d'Annunzio of Chieti-Pescara.

Acknowledgments

The Jeffersonian transcription of the interview was carried out by Bianca Di Giacinto (Sapienza University, Rome).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Formulations are metacommunicative comments (Orletti, 1983, 2000) used to describe what happens in the interaction. They provide order and rationality in the interaction.

2. ^The respondent, Stramezzi, would thus in this turn assume “semantic dominance” in the terms of Linell and Luckmann (1991).

3. ^Drew and Heritage (1992) has identified the issue of “lexical choice” as a key element of institutional interactions.

4. ^: “[…] Proofs (pistis) from character are produced, whenever the speech is given in such a way as to render the speaker worthy of credence—we more readily and sooner believe (pisteuomen) reasonable men (epieikeisi) on all matters in general and absolutely on questions where precision (akribeia) is impossible, and two views can be maintained. But this effect too must come about during the speech, not through the speaker's being believed in advance to be of a certain character” (Rhet. 1365a 4–13).

5. ^Another perspective of analysis relevant to the study of the negotiation of epistemic authority in the medical field could be that of multimodality; cf. in this respect Vincze and Poggi (2022), Orletti (2022b), along with Alfonzetti et al. (2023). We postpone a more in-depth study in this direction to a later study.

References

Alfonzetti, G., Banfi, E. and Orletti, F. eds. (2023). “Agire con le parole… e non solo,” in Studi Italiani di Linguistica Applicata, special issue (SILTA). 52.

Amossy, R. (1999). L'argumentation dans le discours: discours politique, littérature d'idées, fiction. Paris: Nathan.

Amossy, R. (2001). Ethos at the crossroads of disciplines: rhetoric, pragmatics, sociology. Poet. Today 22, 1–23. doi: 10.1215/03335372-22-1-1

Amossy, R. (2010). L'argomento ad hominem: riflessioni sulle funzioni della violenza verbale. Altre Modernità 3, 56–70.

Antaki, C., and Widdicombe, S. (1998). “Identity as an Achievement and as a Tool,” in Identities in Talk, eds. C. Antaki and S. Widdicombe (London: Sage Publications Ltd.) 1–14 doi: 10.4135/9781446216958.n1

Aristotle (1959). “Rhetorica, translated into English by W. Rhys Roberts,” in The Works of Aristotle, ed. W. D. Ross. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Benveniste, É. (1946). Structure des relations de personne dans le verbe. Bull. Soc. Linguist. 43, 1–126.

Boden, D., and Zimmerman, D. H. (1991). Talk and Social Structure Studies in Ethnomethodology and Conversation Analysis. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Clayman, S. E. (1988). Displaying neutrality in television news interviews. Soc. Probl. 35, 474–492. doi: 10.2307/800598

Clayman, S. E. (1992). “Footing in the achievement of neutrality: the case of news-interview discourse,” in Talk at Work, eds. P., Drew, and J., Heritage (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press) 163–211.

Clayman, S. E., and Heritage, J. (2002). The News Interview. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511613623

Eyal, G. (2013). For a sociology of expertise: The social origins of the autism epidemic. Am. J. Sociol. 118, 863–907. doi: 10.1086/668448

Fanelli, D., and Piazza, F. (2020). Analysis and Forecast of COVID-19 Spreading in China, Italy and France. Chaos: Solitons and Fractals. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.109761

Fele, G. (2009). “Glosse e formulazioni,” in Lingua e società. Scritti in onore di Franca Orletti, eds. by M. E., Sciubba, L., Mariottini, and M., Fatigante (Roma: Franco Angeli) 49–59.

Garfinkel, H., and Sacks, H. (1970). “On formal structures of practical action,” in Theoretical Sociology: Perspectives and Developments, eds. J. C., McKinney, and E. A., Tiryakian (New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts) 338–66.

Greatbatch, D. (1988). A turn-taking system for British news interviews. Lang. Soc. 17, 401–430. doi: 10.1017/S0047404500012963

Heritage, J., and Watson, R. (1979). “Formulations as conversational objects,” in Everyday Language: Studies in Ethnomethodology, ed. G., Psathas (New York: Irvington) 123–62.

Heritage, J., and Watson, R. (1980). Aspects of the properties of formulations in natural conversations: Some instances analysed. Semiotica 30, 245–262. doi: 10.1515/semi.1980.30.3-4.245

Hester, S., and Eglin, P. (1997). Culture in Action. Studies in Membership Categorization Analysis. Washington, DC: International Institute for Ethnomethodology and Conversation Analysis & University Press of America.

Jefferson, G. (2004). “Glossary of transcript symbols with an introduction,” in Conversation Analysis: Studies From the First Generation, ed. by G. H. Lerner (Philadelphia: John Benjamims) 13–31. doi: 10.1075/pbns.125.02jef

Leonardi, P., and Viaro, M. (1983). “Insubordinazioni,” in Comunicare nella vita quotidiana, ed F., Orletti (Bologna: Il Mulino) 147–174.

Linell, P., and Luckmann, T. (1991). “Asymmetries in dialogue: Some conceptual preliminaries,” in Asymmetries in Dialogue, eds. I., Marková, K., Foppa (New York: Harvester Wheatsheaf) 1–20.

Lo Cascio, V. (2009). Persuadere e convincere oggi. Nuovo manuale dell'argomentazione. Città di Castello (PG): Academia Universa Press.

Maingueneau, D. (1999). “Ethos, scénographie, incorporation,” in Images de soi dans le discours – La construction de l'ethos, ed. R., Amossy (Lausanne: Delachaux et Niestlé) 75–100.

Mehan, H. (1991). “The schoolwork of sorting students,” in Talk and social structure. Studies in ethnomethodology and conversation analysis, eds. D., Boden, D. H., Zimmerman (Cambridge: Polity Press) 71–90.

Neresini, F., Giardullo, P., Di Buccio, E., Morsello, B., Cammozzo, A., Sciandra, A., et al. (2023). When scientific experts come to be media stars: An evolutionary model tested by analysing coronavirus media coverage across Italian newspapers. PLoS ONE 18, 1–22. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0284841

Orletti, F. (1983). “Pratiche di glossa,” in Comunicare nella vita quotidiana, ed. F., Orletti (Bologna: Il Mulino) 77–103.

Orletti, F. (2019). Latin as a tool for social differentiation and epistemic asymmetry: The language of medicine. Dial. Instit. Sett. 9, 106–124. doi: 10.1075/ld.00034.orl

Orletti, F. (2022a). “Il plexiglass della comunicazione: Come le istituzioni mediche parlano al tempo del Coronavirus,” in Comunicazione, Linguaggi, Società. Studi in onore di Annibale Elia, eds. V., D'Antonio, G., De Bueriis, S., Messina, and A., Scocozza (Bogotà: Penguin books Random House) 405–422.

Orletti, F. (2022b). “La co-costruzione dell'agenda nella visita medica: una prospettiva multimodale,” in Arte e pratica della pazienza. Intorno al pensiero di Paola Cori sul corpo e la malattia, eds. M. Fatigante, C., Pontecorvo (Aprilia: Novalogos) 95–122.

Orletti, F., and Caronia L. (2019). “Dialogue in institutional settings,” in Language and Dialogue 1.

Orletti, F., and Iovino, R. (2018). Il parlar chiaro nella comunicazione medica: Tra etica e linguistica. Roma: Carocci.

Perelman, C., and Olbrechts-Tyteca, L. (1958). Traité de l'argumentation. La nouvelle rhétorique. Bruxelles: Édition de l'Université de Bruxelles, (1969 The New Rhetoric: A Treatise on Argumentation, translated by JohnWilkinson and Purcell Weaver, Notre Dame, IN: Notre Dame University Press).

Poggi, I., D'Errico, F., and Vincze, L. (2011). Agreement and its multimodal communication in debates: a qualitative analysis. Cogn. Comput. 3, 466–479. doi: 10.1007/s12559-010-9068-x

Rothkopf, D. J. (2003). When the Buzz Bites Back. The Washington Post. May 11. Available online at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/opinions/2003/05/11/when-the-buzz-bites-back/bc8cd84f-cab6-4648-bf58-0277261af6cd/ (accessed April 1, 2023).

Scardigno, R., Paparella, A., and D'Errico, F. (2023). Faking and conspiring about COVID-19: a discursive approach. Qualit. Rep. 28, 49–68. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2023.5660

Schegloff, E. A. (1987). “Between micro and Macro: Contexts and other connections,” in The micro-Macro link, eds. J. C., Alexander, B., Giesen, R., Munch, N. J., Smelser (Berkeley: The University of California Press) 207–234.

Schegloff, E. A. (1991). “Reflections on talk and social structure,” in Talk and Social Structure: Studies in Ethnomethodology and Conversation Analysis, eds. D., Boden, D. H. Zimmerman (Cambridge: Polity Press) 44–70.

Schegloff, E. A. (1992). “On talk and its institutional occasions,” in Talk at Work: Interaction in Institutional Settings, eds. J., Heritage, P., Drew (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press) 101–134.

van Eemeren, F. H., and Grootendorst, R. (2004). A Systematic Theory of Argumentation. The Pragma-Dialectical Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511616389

Vincze, L., and Poggi, I. (2022). Multimodal signals of high commitment in expert-to-expert contexts. Disc. Commun. 16, 693–715. doi: 10.1177/09579265221109091

Keywords: certainty/uncertainty, conversational interactions, rhetoric, conversation analysis, expert/expertise

Citation: D'Angelo M and Orletti F (2023) Being an expert in pandemic times: negotiating epistemic authority in a media interaction. Front. Commun. 8:1214927. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2023.1214927

Received: 30 April 2023; Accepted: 22 August 2023;

Published: 22 September 2023.

Edited by:

Ramona Bongelli, University of Macerata, ItalyReviewed by:

Francesca D'Errico, University of Bari Aldo Moro, ItalyRosa Scardigno, University of Bari Aldo Moro, Italy

Copyright © 2023 D'Angelo and Orletti. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mariapia D'Angelo, bWFyaWFwaWEuZGFuZ2Vsb0B1bmljaC5pdA==; Franca Orletti, ZnJhbmNhLm9ybGV0dGlAdW5pcm9tYTMuaXQ=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Mariapia D'Angelo

Mariapia D'Angelo Franca Orletti

Franca Orletti