- Department of Language and Literacy Education, The University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada

Although researchers of language and communication have become increasingly interested in both embodiment and conflict in recent years, little is known about how elementary students use embodied actions modeled by their teachers as they engage in peer conflicts. This paper addresses such questions, focusing on the “quiet coyote” gesture and the “open hand prone” gesture, two emblems commonly used as classroom management strategies in elementary grades. Building on work in language socialization, gesture studies, and other areas of discourse analysis, I propose what I call a gestural socialization perspective for analyzing the nuanced ways the US second-grade children in this study use and socialize one another to use these gestures, as well as other semiotic resources, to handle peer disputes. An ethnographically informed, multimodal discourse analysis centering on a multiracial group of girls reveals how students' gesture practices draw on their teacher's gestural socialization practices while also diverging from them, especially with regard to gestural form, stance object, intended recipient, and accompanying metapragmatic commentary. These aspects of the participants' appropriations of the “open hand prone” and “quiet coyote” emblems, together with their use of gestural innovations, metagestures, and other semiotic resources, allow them to take more oppositional stances than those made relevant by the teacher's practices. Through these multimodal stances, students take a hands-on approach to starting, continuing, and closing peer disputes on their own terms. Overall, the study highlights how participants' handling of disputes often subverted a local emphasis on conflict avoidance, efficiency, and appropriateness and the developmentalist, neoliberal, and standard language ideologies underpinning these norms. The paper closes with a discussion of implications for research and pedagogy, emphasizing the importance of closely attending to the multimodal, interactionally emergent, and culturally situated nature of conflicts among children and people of all ages.

1. Introduction

As various scholars of multimodal communication have noted, research in much of sociolinguistics and gesture studies has historically attended more to polite and inclusive interaction than argumentative and conflictual interaction (e.g., Goodwin and Alim, 2010; Pagliai, 2010a; Wehling, 2017). This bias has been discussed as reflective of various influences, such as White, middle-class values (Goodwin, 1990), speech act theory (Sifianou, 2019), and scholarly and lay discourses that define conflict as the opposite of cooperation and equate it with breakdowns of the social order (Pagliai, 2010b). Interestingly, this relative inattention to conflict is more notable in studies of adults than in those of children; as Berman (2014) discusses, the tendency to focus on conflict in studies of children and on resolution or avoidance of conflict in studies of adults shapes and is shaped by developmentalist views of children and by language ideologies related to (in)directness and (im)politeness. Also prevalent in scholarship on conflicts among children are psychologizing views of particular people or behaviors as either “antisocial” or “prosocial”, labels which, as Bateman (2012) argues, oversimplify the ways (children's) disputes sequentially unfold in particular contexts.

This paper aims to contribute to the small but growing body of scholarship that unsettles these views of (children's) conflicts by investigating peer disputes in a multiracial girls' friendship group in a US second-grade classroom. Specifically, I examine how students handle peer conflicts through the use of two emblems (McNeill, 1992) salient in their ethnographic setting: the vertical palm (VP) variant of the open hand prone gesture (hereafter simply “OHP”) (see Kendon, 2004) and the quiet coyote (hereafter “coyote”) gesture (see, e.g., Gee et al., 2015). Drawing on work in language socialization, gesture studies, and other areas of sociocultural linguistics, I propose a gestural socialization perspective for analyzing how participants' gesture practices, along with their use of other semiotic resources, were fundamental to the stances they took within and on peer conflicts. This analysis addresses gaps in several areas, including the need for multimodal approaches to conflict (e.g., Sifianou, 2019), more research on embodiment in children's disputes (e.g., LeMaster, 2020), greater attention to gestures that signal control and domination (e.g., Wehling, 2017), and perspectives on stance-taking that integrate various modes and stance types (e.g., Andries et al., 2023). The next section situates these contributions within relevant literature and then presents the gestural socialization perspective that guides the study.

2. Researching and theorizing the use of gestures in peer conflicts

By contrast with dominant views of children as unruly and incapable of handling conflict, research from various discourse analytic perspectives has painted a more complex picture of children's conflictual interactions. This section reviews this literature, focusing particularly on interactional studies of younger children's multimodal practices in peer conflicts in school settings. I then discuss the theoretical framework for the study in more detail.

2.1. Multimodal research on peer conflicts

Several decades of language socialization and other discourse analytic research have shown how conflicts are interactionally situated, culturally variable, and socially valuable. As Goodwin (2006) puts it, conflict is “neither an aberration nor something to be avoided at all costs” (p. 33) but is pervasive in everyday interaction and is important in that it serves social goals for children—just as it does for adults (see also Berman, 2014). To be sure, peer conflicts can have significantly harmful effects, such as contributing to the ostracization of students from peer groups (e.g., Goodwin and Alim, 2010; Evaldsson and Svahn, 2012), but in some cases, they may initiate rather than thwart friendships (Corsaro and Rizzo, 1990) and provide opportunities for rearranging social orders (Goodwin, 2006). Conflicts also play a central role in children's and others' socialization into culturally salient practices and values, as becomes especially apparent when comparing and contrasting teachers' approaches to mediating peer conflicts in different sociocultural settings. For example, preschool teachers in Cekaite's (2020) study supported children's affective stances and elicited all conflict co-participants' individual accounts, thereby socializing students into practices of perspective taking and ideologies of justice common in Swedish schools, whereas preschool teachers in Moore's (2020) study encouraged suppression of negative feelings and minimized conflicts in ways that emphasized the (performance of) positive, friendly relationships valued in much of Russian society.

As with research in other areas of communication, recent research on children's conflict navigation practices has increasingly taken a multimodal perspective. Particularly important in this regard is embodied action, which has historically been backgrounded or altogether overlooked in much interactional research in light of dominant discourses that frame the body as “secondary to language rather than as the sine qua non of language” (Bucholtz and Hall, 2016, p. 174). Gestures are one case in point; as Goldstein and Hall (2021) argue, the “cleansing” of gestures from many research practices speaks to still-influential Cartesian and Chomskyan perspectives that “[position] language capacity as a thing of the (human) mind and gestural capacity as a thing of the (animal) body” (p. 700). Given that these dualisms often place children in a shared category with animals (e.g., Hohti and Tammi, 2019), the nuances of the embodied actions of children are particularly subject to being overlooked.

These trivializations and infantilizations of embodied action have been challenged by research attending to the complex ways children and young people use embodied resources to navigate everyday interactions, including peer conflicts. Such work has uncovered a variety of relationships between embodied actions and language: for instance, some research has demonstrated how gestures support, intensify, or emphasize verbal actions (Goodwin, 2006; Bateman, 2012), other work has illustrated how gestural resources may be used to perform styles quite different from those indexed by concurrent verbal actions (Goodwin and Alim, 2010), and still other studies have found embodied actions may altogether replace verbal action, as when students move disputes to the embodied channel so as to exercise agency over when and how conflicts are resolved (LeMaster, 2020). Another important finding of much multimodal work on peer conflict, as with language socialization research more generally (e.g., Goodwin and Kyratzis, 2011), is that children often take up the semiotic practices encouraged or modeled by teachers in unexpected and creative ways that suit their own purposes, as when participants in Moore's (2020) study lie down next to each other in order to appear to comply with the teacher's directives to be friendly while actually verbally continuing a dispute, or when a child in Burdelski's (2020a) study appropriates the teacher's control touch practices in ways that escalate rather than mitigate conflict.

While this multimodal peer conflict research has helped shed light on the interactional and social significance of children's agentive uses of embodied actions, less attention has been paid to how children use specific gestures in peer conflicts. Of particular interest for understanding how communities and individuals develop knowledge to deal with recurrent activities like conflicts are conventionalized, culturally shared gestures (see, e.g., Ladewig and Hotze, 2021), including emblems (McNeill, 1992), which are conventionalized form–meaning pairings that often have a label and are frequently used in the absence of speech, and recurrent gestures (Ladewig, 2014), a near neighbor of emblems that are partly conventionalized and tend to co-occur with speech (see also Gawne and Cooperrider, 2022). Some examples of conventionalized gestures include the palm up open hand gesture (Müller, 2004), the cyclic gesture (Ladewig, 2011), and—especially relevant to the present analysis—the OHP gesture (Kendon, 2004). Although studies on children's recurrent use of conventionalized gestures have tended to adopt developmental perspectives (e.g., Graziano, 2014; Beaupoil-Hourdel and Morgenstern, 2021), some attend to the interactionally emergent and locally situated nature of gestural meaning-making practices, such as Ladewig and Hotze's (2021) study on how Berlin preschoolers' use of recurring slapping gestures to protest or stop others' actions showed the “children's growing practical knowledge of dealing with conflictive situations” (p. 306). Much as these authors focus on children's use of recurrent gestures as a way of understanding how they learned to deal with conflicts, the present analysis focuses on emblems recurrently used in the participants' classroom so as to better understand how they learned to engage in peer conflicts.

With regard to the two emblems at the center of the present analysis—the OHP and coyote gestures—there is a dearth of research, particularly from discourse analytic perspectives. The few published works that briefly discuss one or the other of these gestures frame them as classroom management strategies, a focus which reflects wider developmentalist ideologies about children and children's bodies as unruly, untrustworthy, and in need of regulation through various techniques of power (e.g., Antonsen, 2019). For instance, Gee et al. (2015) describe the quiet coyote gesture as a “fun” way to discourage students from talking (p. 206), and Khan (2019) discusses the OHP gesture, used by many teachers as part of a multimodal practice referred to as “give me five” (to be discussed below), as a “really beneficial” (p. 154) strategy for helping students learn to attend to the teacher. To the author's knowledge, no studies have discussed either of these gestures in terms of how children actually use them in classroom interactions (conflictual or otherwise). However, OHP gestures, which Bressem and Müller (2017) categorize as part of the “away family” of gestures generally associated with negative assessments and refusals, have been relatively well-documented in adults' conflictual and competitive interactions, with gesturers using them to claim a co-participant's turn is interruptive (Kamunen, 2018), to hold off counterarguments (Bressem and Wegener, 2021), and to disagree with an interlocutor's claims (Wehling, 2017). Such gestural moves of disalignment are relevant to the present analysis, which builds on these studies of OHP and on the peer conflict studies discussed above by analyzing participants' multimodal stance-taking practices through the gestural socialization framework that will be discussed in the following section.

2.2. Theoretical perspective: gestural socialization

The concept of gestural socialization that I propose here integrates various principles and concepts from language socialization, gesture studies, and other areas of sociocultural linguistics. Much as Sembiante et al. (2022) build on language socialization scholarship to propose a multimodal socialization framework that emphasizes the centrality of multiple semiotic modes to classroom practices, I offer the concept of gestural socialization as a means of highlighting the crucial role of embodied actions in the reproduction and transformation of cultural practices and social structures. Rather than conceiving of gestures as separate from or more significant than other semiotic resources and practices, this perspective is intended to emphasize a mode of communication that has historically been neglected, as discussed above. Gestural socialization, then, highlights gestural aspects of language socialization by focusing on members' socialization to and through the use of gestural resources and practices (cf. Schieffelin and Ochs, 1986). Both movements and non-movements of the body (Wehling, 2017) as well as participants' use of other semiotic resources (e.g., linguistic, material) may be important to gestural socialization in any given community of practice. And just as all modes matter for gestural socialization, so too do all participants; socialization flows to, from, and through all parties in an interaction, with experts and novices exerting socializing influences on each other, and with learners socializing one another (e.g., Duff and Talmy, 2011; Lee and Bucholtz, 2015).

The particular focus of this study is on peer gestural socialization practices related to two emblems (OHP and coyote), both of which the children in this study appropriate (Bakhtin, 1981) as control gestures that signal control or domination (Wehling, 2017). These control gestures are in turn useful for co-constructing conflictual or oppositional stances. Though fleeting, such stances can harden into well-worn itineraries of identity (Bucholtz et al., 2012). It is worth noting that the focus of this analysis on emblems and on oppositional stances does not preclude the inclusion of attention to other types of stances or gestures. Indeed, a range of stances—such as friendly stances—and gesture types—including more spontaneous and iconic gestures, recurrent gestures, and narrative-referential gestures (Wehling, 2017)—are also aspects of gestural socialization, as some of the below examples illustrate. To contextualize these examples, I turn now to an overview of the ethnographic and discourse analytic approaches to data generation and analysis that guided this study.

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Setting, participants, and data generation

From 2013 to 2016, I, a middle-class English–Spanish bilingual White woman from the U.S., served as a volunteer in Room Z, a second-grade classroom (i.e., ages 7–8 years) at Beachside Elementary School. Beachside is located in a suburban area near a mid-sized California city and serves a racially and linguistically diverse student body. During the 2014–15 school year (the year I generated data for this study), Room Z roughly reflected the linguistic and ethnoracial demographics of the school as a whole: With regard to language status, nine of Room Z's 21 students were English learners; and with regard to ethnoracial categories, ten students were Latinx, five were White Euro-Americans, one was Latinx and White, one was Mexican and Italian, one was Indian American, one was Arab American, one was African American, and one was Filipino American. Their teacher, Ms. Martin, was a well-liked middle-class White woman with over a decade of teaching experience.

The 2014–15 academic year was significant for the school in that it marked the first year of Beachside's full implementation of the Common Core State Standards (CCSS), a set of standards that have been characterized as “the center-point of neoliberal reforms in the United States” (Brass, 2014, p. 127). Within the CCSS and other neoliberal reforms and discourses, students' agency, prior knowledge, and lived experiences tend to be instrumentalized or altogether marginalized, as exemplified by the narrow view of literacy underpinning the emphasis on close reading in the CCSS (e.g., Aragón, 2022). Neoliberalism intertwines with developmentalism (Richardson and Langford, 2022), constructing a de-agentialized view of students as “continually flattened of experience and stripped of sovereignty by virtue of being a child rather than a human being” (Sonu and Benson, 2016, p. 232). Such flattening of experience was likewise present in CCSS-era Room Z, as reflected by some aspects of Ms. Martin's socialization of “academic” communication and conflict negotiation practices, discussed in more detail in the Results section.

As is typically the case in ethnographic participant observation, my role in Room Z was a hybrid one. Ms. Martin and her students knew me as one of several adult classroom volunteers (often referred to as “teachers” by Ms. Martin) and also as a researcher interested in academic language, the focus of the larger study for which the data analyzed here were generated (see, e.g., Corella, 2020, 2022). In this volunteer–researcher role, I engaged in ethnographic participant observation 2–4 days per week throughout the year during language arts and math activities, and at times during other activities (e.g., recess, art). During my visits, I supported students and Ms. Martin with academic tasks and social interactions, including mediating peer conflicts, while simultaneously generating fieldnotes, collecting copies of student work and other classroom texts, and audio- and video-recording approximately 300 h of classroom interactions and ethnographic interviews. These audio and video recordings—the primary data source for this analysis—were collected through an HD camcorder and a set of two digital audio recorders equipped with lapel microphones worn by two students per day; the day's focal students were chosen based on their own requests to wear the microphones.

Before beginning data generation, I discussed the study with Ms. Martin, the school principal, and the district superintendent. After they approved (and having received approval from my institution's ethics review board), I approached parents with the help of Ms. Martin, who invited me to present my study at Back-to-School Night. In the weeks after this event, parents of 20 students returned signed consent forms, and I then proceeded to obtain oral assent from these students. Of these 20 students, nine regularly positioned themselves as eager to participate by frequently asking to be interviewed and/or to be the focus of audio and video recordings. I decided to concentrate on these students for my analyses since I view participants' repeated expressions of desire to participate as an important aspect of the meaningful face-to-face ethnographic consent practices described by others (e.g., Metro, 2014).

In this analysis, I focus particularly on Brooklyn,1 a seven-year-old White student, in part because she was one of the aforementioned nine students who regularly expressed interest in participating in the study, and also because she was often positioned as disruptive by Ms. Martin and her peers. The co-construction of what Brooklyn herself (cheerfully) described to me as a “sassy” persona and (tearfully) as a “trouble maker” identity began early in the year; for instance, my fieldnotes for the second day of school detail an incident in which a highly visible reproach–response sequence (see also Talmy, 2009; Evaldsson and Melander, 2017) culminated in Ms. Martin sending Brooklyn to the principal's office. The involvement of the principal and other adults in mediating conflicts between Brooklyn and other peers would become a recurring pattern throughout the school year, intensifying around March due to a series of disputes between Brooklyn and her three “best friends” in Room Z, Natalie, Sabrina, and Noelle, all three of whom were female-identified students of color2 and were the most popular girls in the classroom. By March, the four girls, a multiracial clique similar in its exclusivity to the groups studied by Goodwin (2006), were at the center of what Ms. Martin described to me as considerable “girl drama”, leading the teacher, several parents, and the principal to meet and begin implementing rules directing each of the four girls to refrain from talking with, playing with, and/or sitting with one or more members of their friendship group. I have chosen to examine gesture-mediated conflicts between Brooklyn and one or more of these three (former) friends as a “telling case” that helps “make previously obscure theoretical relationships suddenly apparent” (Mitchell, 1984, p. 239), including the relationships between gestures and peer conflicts in Room Z. It should be noted that despite the focus on female-identified students across the examples, my analytic focus is not on gender-specific practices or norms, a point on which I elaborate in the Discussion section.

3.2. Data analysis

The below analysis is based on ~15 h of video recordings from the larger dataset and began with a broad question about how students used the OHP and coyote gestures in their peer interactions. I decided to focus on both of these gestures since I had observed that students often used them in seemingly synonymous or overlapping ways, and as will be discussed in further detail below, I had also noticed that students seemed to use both gestures in ways that differed from Ms. Martin's usage. I thus proceeded to randomly sample the video data, often initially watching footage with the audio muted so as to prioritize embodied aspects of interaction (Wilmes and Siry, 2021) as I deductively coded for instances of both gestures. Since this initial analysis suggested that many tokens of the gestures occurred in moments of peer conflict, I decided to focus more specifically on conflictual exchanges, identifying them initially through the use of logs created by research assistants for the larger academic language study. My identification of conflicts was guided by Moore and Burdelski's (2020) definition of conflict as a “sequentially and situationally organized activity, composed of at least two sequential actions or oppositional stances by two or more parties” (p. 1; emphasis added). Within conflictual episodes, I continued deductively coding for OHP and coyote, adding inductive sub-codes capturing more specific observations about particular embodied actions (e.g., “OHP in peer's face”, “bouncing coyote”), the nature of the conflict (e.g., “seating conflict”), and participants' assessments of others' actions (e.g., “annoying”, “rude”).

Once I had decided to focus on Brooklyn for the aforementioned reasons, I transcribed conflict episodes in more detail using conventions adapted from Du Bois (2006) and Bucholtz et al. (2012) (see Supplementary material for transcription conventions). As I transcribed, I attended particularly to aspects of participants' embodied actions highlighted in my literature review, such as types of force used (Wehling, 2017), use of space and other “utterance qualities” (Hoenes del Pinal, 2011, p. 601), and other (non-manual) aspects of embodiment, such as facial expression and gaze (e.g., Beaupoil-Hourdel and Morgenstern, 2021; Heller, 2021). My transcription and analysis were also guided by sociocultural linguistic scholarship on stance-taking, particularly by a non-logocentric view of stance as a multimodal phenomenon (see, e.g., Andries et al., 2023) and by Kiesling's (2018a) view of stance as involving the creation of three types of relationships: “investment (relationship to the talk itself), evaluation (relationship to entities in talk), and alignment (relationship to others in the interaction)” (p. 10). The episodes presented below were chosen for more in-depth analysis because they include clear examples of not only the target gestural forms and situated social uses of these forms, but also metapragmatic reflections on them, such as “meta-corporeal” comments (Burdelski, 2020b) constructing particular bodily forms in culturally specific ways. The analysis presented in the next section shows how all these aspects of students' practices were central to their socialization to and through the use of gestures for handling peer conflict in Room Z.

4. Results

In this section, I present analyses of several interactions in which Brooklyn and her peers socialized one another to use OHP and coyote, along with other semiotic practices, as resources for taking a range of affective and deontic stances central to instigating, mitigating, mediating, (de)escalating, and concluding peer conflicts. I begin with a sketch of the teacher's gestural socialization practices related to the two emblems, briefly situating them within the local ethnographic and broader sociocultural context. I then present an in-depth interactional analysis of how Brooklyn and her peers appropriated these gestures for their own purposes, reanalyzing their meanings and forms in ways that shaped and were shaped by their conflicts with one another.

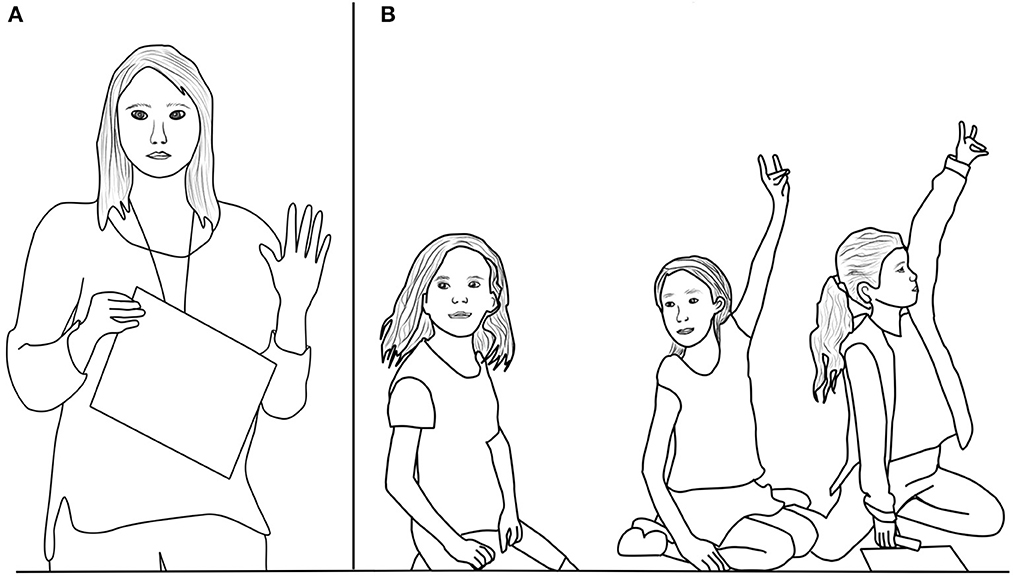

4.1. Ms. Martin's gestural socialization of efficient, scholarly conduct

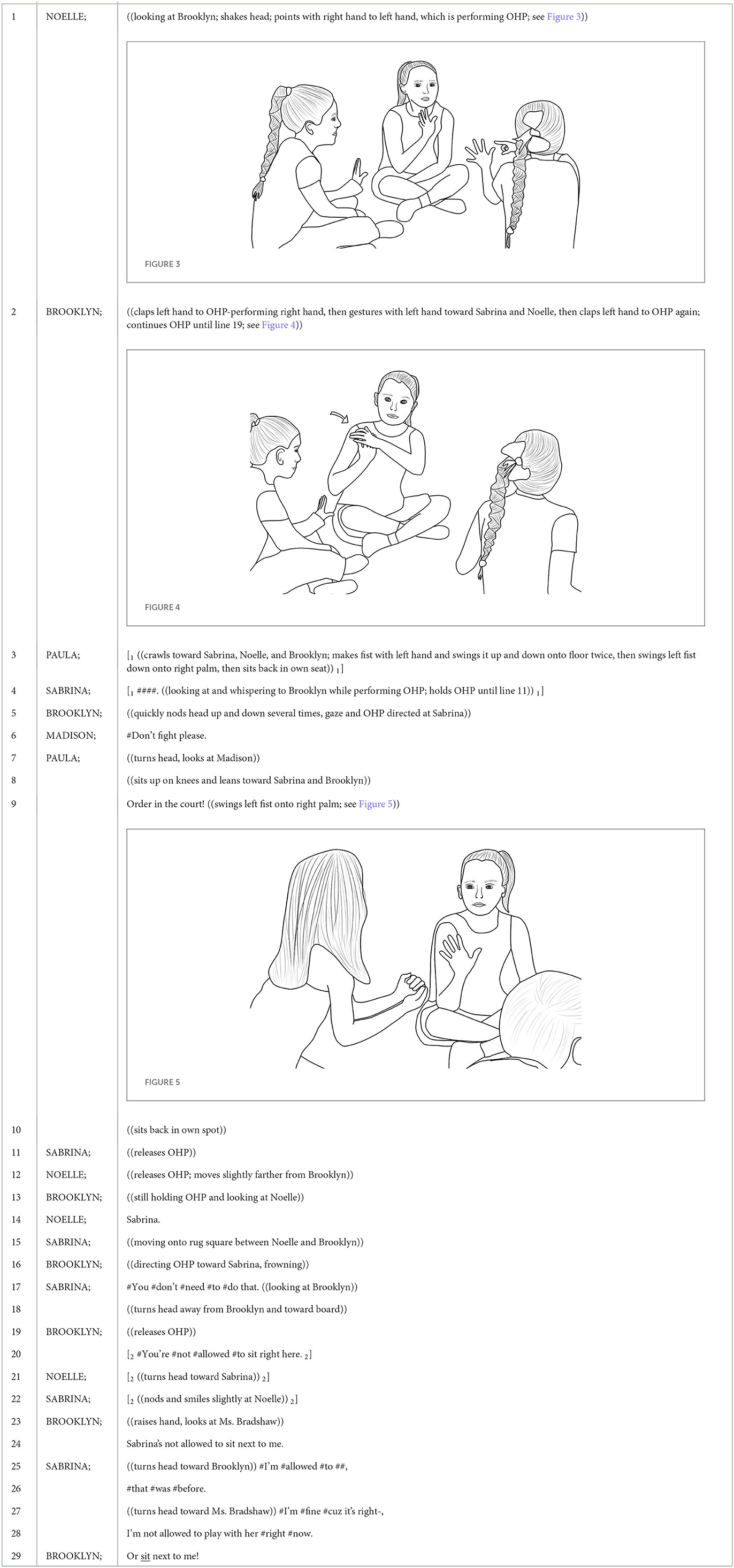

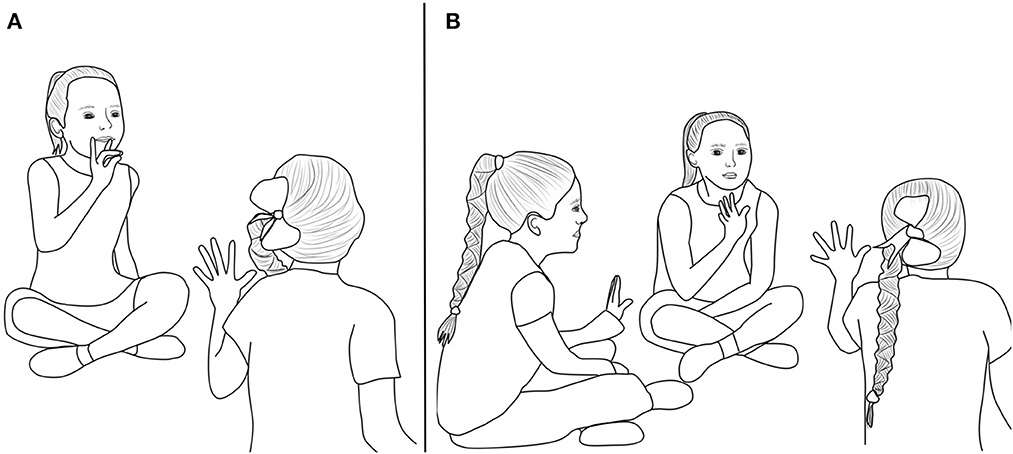

To understand the relationships between OHP and quiet coyote in the students' and teacher's practices, it is useful to begin with a description of each gesture as socialized by Ms. Martin. For its part, the OHP gesture—glossed as “give me five” in Room Z—was an embodied reference to a prominently displayed mass-produced poster listing five aspects of “good listening”: “eyes on speaker,” “lips closed,” “ears listening,” “sit up straight,” and “hands and feet quiet.” Framing these five listening practices as what “good students” and even “scholars” do, Ms. Martin routinely reminded students of them by holding up her own hand near her chest, OHP-performing palm faced outward toward the recipient (always a child), a relatively serious or neutral expression on her face (see Figure 1A). Her uses of OHP communicated stances of deontic authority in that they were often accompanied by verbal imperatives (e.g., “Brooklyn, give me five”) or negative evaluations indexing the poster (e.g., “I think you're having trouble with number two”). She also encouraged students to perform OHP in the manner shown in Figure 1A toward peers as a way of being “helping” others by “reminding” them of the listening norms if there were breaches, especially if a breach was “distracting” to the gesturer. Thus, rather than directly indexing the casual, solidarity-building stances and identities conventionally associated with the idiom “give me five”, in Ms. Martin's gestural socialization practices, the OHP gesture, its “give me five” emic label, and the listening practices to which they referred indexed relatively high investment in affectively serious, compliant stances toward the teacher's discourse and toward semiotic practices enregistered (Agha, 2003) as “academic”, an enregisterment intertwined with raced, gendered, and classed ideologies of appropriateness (see also Corella, 2020, 2022).

Figure 1. (A) The “give me five” OHP gesture and (B) the “quiet coyote” gesture as socialized by the teacher.

Similarly, the “quiet coyote” gesture as modeled by Ms. Martin indexed compliant stances toward academic discourse and the teacher's authority, but it differed from OHP with regard to form, intended recipient, and stance object. Whereas the “give me five” OHP gesture was to be directed at peers to communicate a negative evaluation of a peer's behavior and to take a stance of deontic authority similar to a verbal directive (e.g., “give the teacher five”), quiet coyote was to be performed toward the teacher and was designed to convey a positive evaluation of the gesturer's own verbal and embodied conduct, akin to a verbal statement in the indicative mood (e.g., “I'm quiet and ready to listen”). Given these differences in stance, stance object, and recipient, the two gestures also differed from each other with regard to gestural space (Hoenes del Pinal, 2011): Whereas the OHP gesture was to be performed briefly and close to the gesturer's chest, with both palm and gaze oriented toward the offending peer (see Figure 1A), the quiet coyote gesture was usually longer in duration, was performed as a choral activity by multiple (or all) students once they were ready to listen, and occupied more space since, in order to be visible to the teacher, it was performed above the gesturer's head, with the “ears” and “nose” of the coyote usually facing toward the teacher (see Figure 1B).

Despite these differences, the two gestures overlapped with regard to the ideologies they indexed. The ways Ms. Martin socialized students to and through the use of both gestures emphasized several interrelated cultural values and practices, particularly standard language ideologies related to “academic” language, (neoliberal) efficiency, and developmentalist ideologies of bodily containment. In Ms. Martin's gestural socialization practices, both gestures indexed communication locally enregistered as “academic” in that she used them to emphasize listening “like scholars” and otherwise behaving “appropriately”. She also used both gestures to encourage silent and “efficient” transitions between classroom activities (in fact, efficient, like appropriate, was part of a set of about 25 words locally marked as “academic vocabulary”). This verbal and gestural emphasis on efficient, appropriate, and academic conduct tended to mean that Ms. Martin, like many other early childhood educators (e.g., LeMaster, 2020; Moore, 2020), typically worked to minimize peer conflicts, encouraging students to leave disputes on the playground. Besides implicitly reinforcing views of conflict as irrelevant to academic work and as something to be avoided, Ms. Martin's OHP and coyote gestural socialization practices also reinforced the developmentalist ideologies discussed above in that she and other adults in Room Z—much like teachers in other classrooms (see, e.g., Gee et al., 2015; Khan, 2019)—used both gestures as resources for socializing children to perform bodily containment, a defining feature of normative adulthood (see, e.g., Liddiard and Slater, 2018).

4.2. Peer gestural socialization for handling conflict

In their interactions with one another, and especially during peer conflicts, students often used the two gestures in ways that pushed back against these ideologies of containment, efficiency, and standard language by creating space for a wider range of evaluations and stances than those made relevant by the teacher's OHP and coyote practices. One indication of both gestures' utility, flexibility, and salience in Room Z's communicative ecology is their prevalence. Within the 15 h of video analyzed, I identified 79 tokens of OHP and 30 tokens of quiet coyote produced by students in peer interactions, meaning that on average within the data sampled, one of the two gestures was visible on camera about every 8 min in the classroom. Of the 79 OHP tokens produced by students, 45 tokens (about 57%) occurred in moments of peer conflict, and of the 30 quiet coyote tokens, 16 tokens (about 53%) occurred in moments of conflict.

The tokens of OHP and coyote produced by students both drew on and diverged from Ms. Martin's gestural socialization practices. With regard to coyote, students' use of it to silence one another (exemplified below) reflected its association with silence in Ms. Martin's practices, yet their use of it to convey negative evaluations and take oppositional stances in peer conflicts represented a departure from the teacher's socialization of the gesture as a resource for facilitating efficient, collaborative transitions through visible positive assessments of one's own conduct. These differences in pragmatic meanings were linked to differences in form: students' coyotes often made different use of gestural space, with the gesture performed close to their faces or chests instead of above their heads, as will be exemplified below. For its part, the ways OHP was used by students for handling conflicts generally reflected the negative evaluations performed by the teacher's use of it and by others' use of OHP in other contexts (e.g., Wehling, 2017; Kamunen, 2018).3 Importantly, however, students' OHP practices during moments of peer conflict differed from the teacher's practices in that their oppositional uses of OHP did not necessarily relate to Ms. Martin's intended use of the gesture—namely, to “remind” peers to adhere to “give me five” listening practices so as to mitigate distractions, but not disputes per se. Rather, students' negative OHP evaluations tended to arise in relation to actions students themselves deemed “illegal” (Bateman, 2012), offensive, or otherwise accountable, as became especially clear in moments in which students produced verbal assessments alongside OHP gestures. These verbal assessments included characterizations of peers' behavior as “rude” (as in Example 3 below), as violating norms not related to academic communication practices (as in Examples 1 and 3), or as not worth listening to (as in Example 2). The below examples also highlight other ways students' gestural socialization practices departed from Ms. Martin's, including with regard to uses of gestural space, gestural duration, types of stance taken, stance objects, gesture recipients, and metapragmatic commentary on gestures and stances. As will be shown, all of these aspects of the students' semiotic practices point to the strategic ways they used and socialized one another to use OHP and quiet coyote—as well as other gestures not modeled by Ms. Martin—as resources for co-constructing a range of stances, and investing to varying degrees in these stances, during peer conflicts.

4.2.1. Gestural socialization into covertly handling conflicts

The first example demonstrates how students agentively used OHP and quiet coyote, as well as metagestures and other gestures, to covertly carry out conflicts by conducting them largely in the embodied mode rather than the verbal mode (see also LeMaster, 2020). This example occurs as the class is about to begin a daily routine involving recording the temperature, forecast, and other related observations. Some students have already taken seats on the classroom area rug, which has thick black lines dividing it into 20 squares, each of which was typically occupied by one Room Z student—a material affordance sometimes used by Ms. Martin as a means of socializing students into practices for mitigating or avoiding conflicts. For example, a few weeks earlier, at the beginning of a 3-month period marked by near-daily conflict between Brooklyn, Sabrina, Noelle, and Natalie, Ms. Martin had suggested semi-permanently assigning the four girls rug squares located at a distance from one another by putting tape with each of their names on particular squares. However, this formal seating assignment system was never actually implemented, with Ms. Martin instead deciding to leave it to the four students to ensure they kept their distance from one another or otherwise avoided further conflictual interactions with one another.

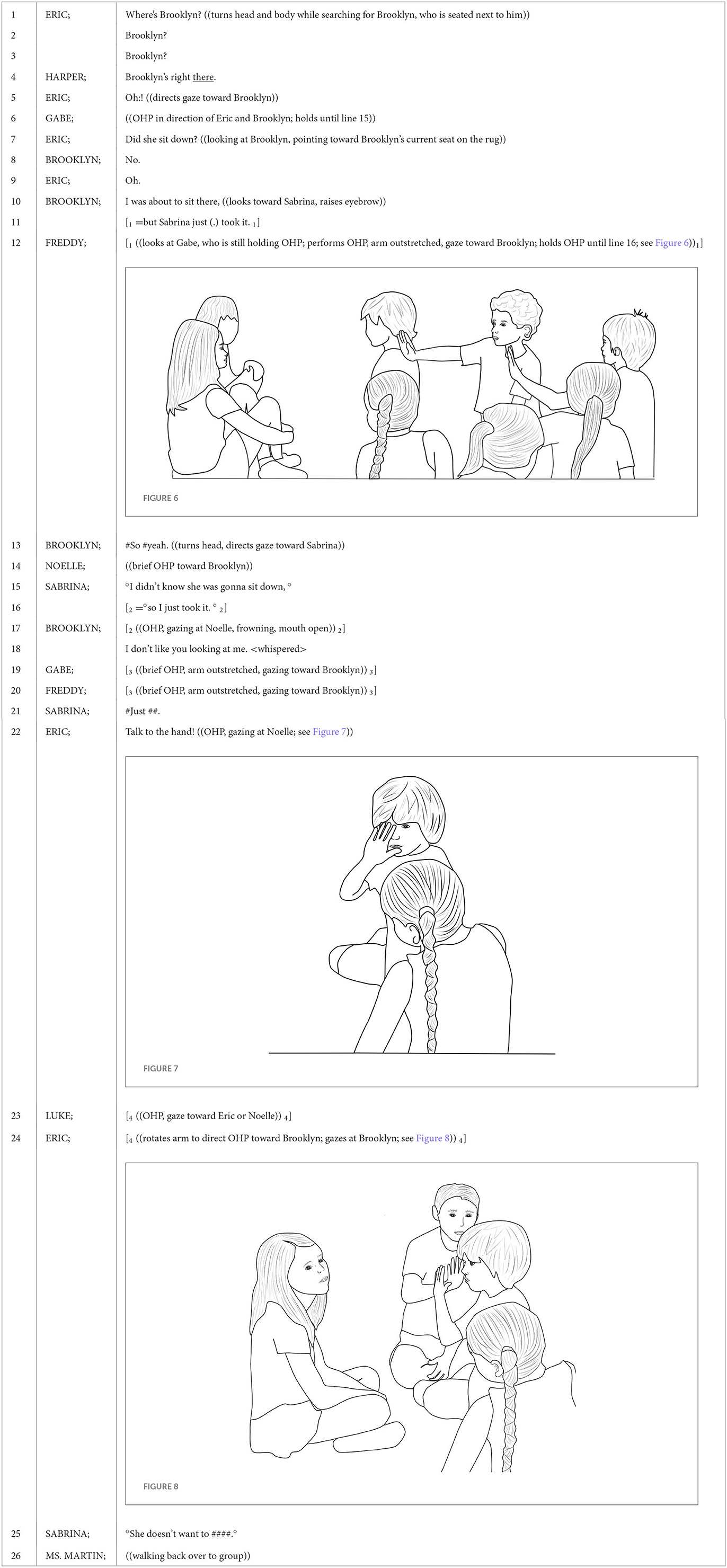

Seating comes to figure prominently in the conflict represented in the following figures and transcript. In this interaction, a dispute between Brooklyn and Noelle is already underway when the day's footage begins. The two students are seated on the rug in the same row as each other, one unoccupied rug square between them, and are facing each other, periodically shaking their heads, and occasionally addressing each other in low voices, their brief utterances during this part of the exchange unintelligible. A few seconds into the video, Noelle visibly disaligns with Brooklyn by directing an OHP toward her, who immediately gesturally responds with a quiet coyote performed not above her head (as socialized by Ms. Martin) but close to her face and directed toward Noelle (see Figure 2A), exemplifying how the students had reanalyzed the form and pragmatic meaning of the coyote gesture as a resource for handling conflict. A fraction of a second later, Brooklyn releases the fingers forming the “snout” of the coyote gesture such that her coyote transforms into an OHP; meanwhile, Noelle continues her own OHP. Considering OHP's use within Ms. Martin's practices as a resource for negatively assessing others' actions, Brooklyn's shift from a coyote into an OHP can be seen as upgrading her disalignment to a more deontically authoritative, oppositional stance toward Noelle, and the coyote–OHP sequence as a whole is relatively marked and thus emphatic.

Figure 2. (A) Brooklyn (left) directs a coyote gesture at Noelle (right) while Noelle directs an OHP at her. (B) Moments later, Sabrina (left), Brooklyn (center), and Noelle (right) begin a three-way OHP standoff; Sabrina's and Noelle's OHPs are directed toward Brooklyn, and Brooklyn's OHP is directed at the other two students.

Moments later, Sabrina sits down near them and joins Noelle in performing an OHP toward Brooklyn. The three girls are now performing a three-way OHP (see Figure 2B), Sabrina and Noelle disaligning with Brooklyn and aligning with each other through OHPs directed at Brooklyn, who shifts her gaze and her own OHP back and forth between her two peers, disaligning with them both. Though accompanied by only a few short, low-volume utterances, this quite literal stance triangle (cf. Du Bois, 2007) of OHPs is markedly conflictual, as becomes apparent as two nearby peers, Paula (a quiet Latina student generally positioned as kind and smart) and Madison (a Latina peer seen as less academically able but as friendly and well-behaved), intervene moments later in Example 1 below. By the time the below exchange begins, Brooklyn, Noelle, and Sabrina have already been in a multi-party OHP standoff for about 20 s. Below, the students' continued use of OHP and metagestures about OHP as well as other resources—especially gestural neologisms and verbal citations of morally authoritative figures, practices, and norms—all become central to their gestural socialization of one another into multimodal practices for navigating multiparty disputes (Example 1; Table 1).

One striking feature of Example 1 is Noelle's and Brooklyn's use of metagestures as emphatic metapragmatic comments on their own OHPs (lines 1, 2). Here, their metacorporeal commentary serves neither to correct non-normative embodied actions (cf. Burdelski, 2020b) nor to highlight the communicative and pedagogical relevance of specific aspects of their gestures (cf. Arnold, 2012), but to draw additional attention to the OHP as a whole, thereby heightening both students' investment in their oppositional stances. Importantly, such pragmatic emphasis is accomplished not only through each individual metagesture on its own, but also through the sequential emergence of these metagestures as cooperative, responsive actions that demonstrate the kinds of selective repetition and recycling of prior turns documented in practices of format tying (Goodwin, 2006), dialogic syntax (Du Bois, 2007), and dialogic embodied action (Arnold, 2012). That is, while both Brooklyn and Noelle use metagestures to refer to their own OHP gestures, their metagestures are not identical; for example, Noelle's metagesture in line 1 (see Figure 3) is more brief and occupies less gestural space than Brooklyn's metagesture in line 2 (see Figure 4), and the two also differ in that Brooklyn uses her metagesture not only to indicate her own OHP but also to point to Noelle and Brooklyn in a rapid sequence in which she first claps her OHP hand, then gestures in a wide arc toward her two peers, and then claps her OHP hand once again, as if to say, “this OHP applies to both of you”.

While practices of format tying may have a variety of effects—for instance, they can contribute to escalating conflicts or help shift them into more playful alignments (e.g., Rodgers and Fasulo, 2022)—the metagesture sequence here is treated in the former manner, as evidenced not only by Noelle's, Brooklyn's, and Sabrina's continuation of their OHPs beyond line 2, but by the subsequent intervention of Paula and Madison. Paula intervenes first, attempting mediation through the gestural mode by swinging her fist up and down several times (line 3). Yet her embodied actions elicit no visible or audible response from Brooklyn, Noelle, and Sabrina, nor do the three girls visibly respond to Madison's verbal directive to “please” stop fighting (line 6). However, Paula appears to attend to and build on Madison's request; after turning to look at Madison (line 7), she summons the authority of a judge by repeating her gesture from line 3, coupling it with the verbal directive “order in the court!” (line 9). Given this utterance, Paula's gestural phrases in lines 3 and 9 can be interpreted as iconic representations of a judge's gavel, a spontaneous gestural neologism not observed elsewhere in the data. Perhaps due to its markedness and to the pushing force of the lean-in (Wehling, 2017) with which Paula performs this gesture, this novel multimodal directive is met with a partial de-escalation in that Noelle and Sabrina release their OHPs (lines 11, 12).

Unlike Noelle and Sabrina, Brooklyn does not visibly respond to Madison's and Paula's moves to mitigate the conflict, instead positioning herself as holding onto the conflict by holding her OHP. She does eventually release her OHP when Sabrina verbally evaluates it as unwarranted and looks away from her (lines 17, 18), but she keeps hold of her negative evaluation of Sabrina's actions, verbally rebuking Sabrina about her choice of seat (line 20) and appealing to Ms. Bradshaw, an adult volunteer, for mediation (lines 23, 24). In response to being positioned as violating a rule by sitting where she is “not allowed” to sit (likely a reference to the aforementioned adults' rules for the four girls), Sabrina takes a stance of epistemic authority, positioning herself as more knowledgeable about the specificities of the rules than Brooklyn by using temporal markers (“before”, “right now”) to signal she has registered rule changes that now permit her to sit near Brooklyn but not play with her (lines 25–28). For her part, Brooklyn remains invested in her oppositional stance and in the conversation, prosodically emphasizing the word “sit” as she counters that Sabrina is not allowed to sit or play with her (line 29). Although this accusation sequence ends at line 29, the conflict is not over, as evidenced by the fact that Brooklyn performs several more OHP and coyote gestures toward Sabrina in the 10 min following Example 1 and by the fact that 2 weeks later, Brooklyn and Sabrina once again have a dispute about seating, as shown in the next example.

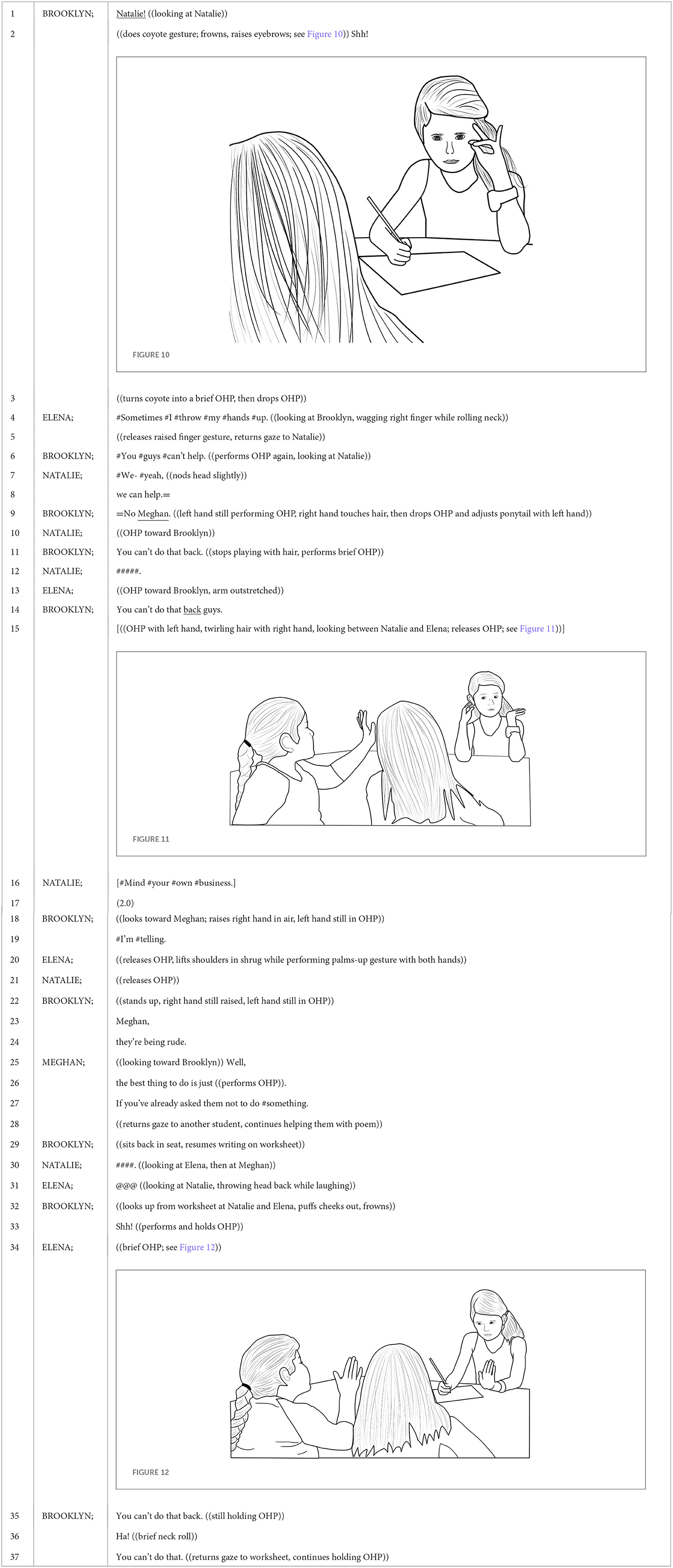

4.2.2. Gestural socialization into taking stances on others' conflicts

As in Example 1, the conflict in the next example revolves around seating, is mediated by peers, and features multiple tokens of OHP. However, unlike Example 1, in Example 2 below, OHP is used not only by conflict co-participants but by a number of bystanders in ways that allow these peers to physically and figuratively have a hand in a dispute that otherwise does not involve them, highlighting the role of OHP in students' gestural socialization as a resource for taking stances on others' conflicts and on others' moment-to-moment stances during these conflicts. About 1 min before the below example begins, Brooklyn and Sabrina have walked to the rug and have reached the same square at approximately the same time, but Sabrina (apparently having not seen Brooklyn) sits down right before Brooklyn appears to be about to sit, whereupon Brooklyn repeatedly and increasingly loudly says to Sabrina that she was about to sit there. These repetitions and increased volume are treated as mediation requests by others. First, a nearby peer, Eric (an outgoing White male-identified student), tells Brooklyn that “it doesn't matter” where she sits. Next, Ms. Martin likewise downplays Brooklyn's complaints by asking Brooklyn to simply find a different spot, thereby working to restore the moral order rather than ascribe individual blame (see Cekaite, 2012). When Brooklyn protests, Ms. Martin tells Brooklyn, “You were about to [sit down], but she was also about to, and she sat down. It's not a big deal”.

However, it appears to be a rather “big deal” for at least several students; about 1 min later, after Brooklyn has found another seat and the group has resumed their discussion of geometry, the dispute is revisited. Line 1 of the exchange below occurs about 2 s after Ms. Martin has begun walking to the back of the room in order to check a student's geometry work while continuing to explain the concept of area to the group (for reasons of space and analytic focus, the teacher's concurrent geometrical explanations are not represented in the below transcript). With the teacher now at some distance from the group and occupied with explaining geometry, Eric, Brooklyn, and several other peers return to the seating dispute, mobilizing OHP, metapragmatic commentary about OHP, and other semiotic resources to position themselves as highly invested in taking a range of negative evaluative stances toward not only Brooklyn's and Sabrina's actions but other peers' actions as well (Example 2; Table 2).

The pervasiveness and range of uses of the OHP gesture in Example 2 emerge within an interactional sequence in which Eric—the peer who, as discussed above, had been the first to downplay the dispute—proposes revisiting Brooklyn's and Sabrina's seating conflict (lines 1–7), thus orienting to it as having continued relevance for not only the two girls but for him and other peers. This framing begins with high-investment stances taken by Eric through his request for others' assistance in locating Brooklyn (who in fact is seated next to him) and through verbal and embodied actions that draw attention to his search, including repetitions of her name and turns of his head and body to search for her (see lines 1–5). Thus, by the time Eric makes a direct reference to the seating conflict through his question about whether Sabrina took Brooklyn's spot (line 7), several others—most visibly Harper (see line 4) and Gabe (see line 6)—have already been drawn into the interaction about the dispute, which now takes on a triadic format similar to gossip disputes (e.g., Goodwin, 1990, 2006; Evaldsson and Svahn, 2012), but with the person who is being discussed (i.e., Sabrina) physically present. Although Brooklyn might have ignored Eric's question or otherwise refused to continue the dispute, she invests in revisiting it, implicitly aligning with Eric's stance on the dispute's relevance by answering him (“no”, line 8) and then by offering further details that position Sabrina as the instigator who “just took” the spot Brooklyn was about to take (lines 10, 11). Sabrina's own brief account—uttered with lower volume than Brooklyn's—is that she did not realize Brooklyn was going to sit down (lines 15, 16). By claiming more turns at talk than Sabrina, producing her utterances with higher volume, and negatively evaluating Sabrina's actions through her verbal accusations, eyebrow raises, and glances at Sabrina (lines 10–13), Brooklyn takes comparatively high-investment stances that help position her as the aggrieved party.

High-investment stances are likewise taken by other peers, particularly through their use of OHP. Most notable in this regard are Gabe and Freddy (two male-identifying friends who were well-liked and generally seen as academically able), who use OHP repeatedly (lines 6, 12, 19, 20) and sometimes with markedly long holds (ranging from 9 to 10 s), in this way positioning themselves as invested in their negative evaluations, especially compared to the various peers around them who do not gesturally or verbally take a stance. Unaccompanied as they are by verbal utterances, Gabe's and Freddy's OHPs do not make clear whether the stance object is the topic of the conversation, the particular manner of Eric's reinvocation of seating dispute, Brooklyn's actions, or simply the fact that students are talking while the teacher explains geometry. Yet what Gabe's and Freddy's long OHP phrases do clearly signal is high investment in positioning themselves as evaluators of the interaction and in disaligning with Eric and Brooklyn. In Freddy's case, OHP also serves as a resource for aligning with Gabe insofar as his OHP begins only after he has directed his gaze toward Gabe's OHP (line 12). Like Gabe and Freddy, Noelle uses OHP (line 14) to disalign with Brooklyn, but unlike the boys' OHP phrases, Noelle's is brief (about 1 s long) and begins after Brooklyn has apparently closed her account (line 13). Brooklyn directly responds to Noelle's OHP with her own OHP (line 17)—the first and only time she uses OHP in this interaction. Brooklyn's OHP matches Noelle's in form and duration, yet she upgrades her oppositional stance by offering a metapragmatic account for her OHP as motivated by Noelle's gaze (“I don't like you looking at me”, line 18). By contrast with cases in which gestures intensify (Goodwin, 2006) or support (Bateman, 2012) verbal actions, here, Brooklyn's verbal actions intensify and support an OHP gesture already in progress.

Of course, the directionality of intensification can be more ambiguous or potentially mutual, as exemplified by the next turn, in which Eric's metapragmatic comment “talk to the hand” (line 22), uttered at the same time as he begins an OHP, works together with his gesture to enact a markedly deontically authoritative, oppositional stance. In the broader sociocultural context, this idiom, which is typically accompanied by OHP and sometimes by the explanation “cuz the face isn't listening”, is widely enregistered as slang (Wikipedia, 2023) and is often interpreted as indexing aggressive and rude stances (e.g., Truss, 2005) as well as cool styles (e.g., Schaffer and Skinner, 2009), likely because of its origins in and indexical connections to Black communicative practices (e.g., Schaffer and Skinner, 2009; Troutman, 2010). Thus, Eric's metapragmatic “talk to the hand” commentary—the only token of this idiom in the data analyzed—can be seen as an act of stance appropriation (Kiesling, 2018b) that contextualizes his OHP as more overtly oppositional and less “academic” than OHP as used in the teacher's comparatively affectively neutral “give me five” OHP socialization practices. Less than a second after producing this verbal utterance, Eric physically and figuratively pivots in this stance-taking act by swinging his OHP palm from Noelle toward Brooklyn (line 24), thereby ultimately disaligning with both Brooklyn and Noelle through his multimodal directive to close a conversation that he himself re-opened. At this point, the teacher returns to the group, and the students drop the remaining OHPs and their revisitation of the dispute. This sudden ceding of their local moral order to hers underlines how OHP often had a more overtly conflictual meaning in peer-only interactions compared with interactions in her presence.

Yet in what appears to be a covert way of having a final say in the ostensibly dropped dispute, Brooklyn uses an OHP-like gesture about 4 min later during the group geometry discussion. At this point, the teacher has just finished explaining the concept of perimeter, and Brooklyn spontaneously produces an iconic gestural neologism that resembles the perimeter of a rectangle: She holds her arms parallel to each other, forming two sides of a rectangle, and uses her palms to form the other sides. She playfully experiments with this perimeter gesture for about 12 s, switching the positioning of her arms and rotating her torso as she performs it. Several seconds into this gestural play, she swings her torso toward Sabrina and directs her gaze at her, pausing for about 2 s in a position in which her left palm is facing toward Sabrina in the style of OHP (see Figure 9).

Figure 9. Brooklyn (right, background) turns toward Sabrina (left) as she performs an OHP-like gesture within a perimeter gesture.

Although this gesture differs in form from the tokens of OHP discussed above, the fact that Brooklyn looks directly at Sabrina (whereas she appears not to direct her gaze toward any particular peers during the rest of her “perimeter” gesture performance) and the fact that she pauses in the position seen in Figure 9 (i.e., with her palm facing Sabrina) suggest the action may be a creative embedding of OHP into the perimeter gesture, a sort of infixation of the control gesture within an overarching narrative-referential gesture (see Wehling, 2017). The ambiguity of this OHP–perimeter gestural hybrid is an affordance that helps Brooklyn position herself as grasping the relevant academic content while simultaneously and surreptitiously disaligning with Sabrina by reconfiguring the normative meanings of the teacher's OHP practices. Since Sabrina's gaze is directed toward her own lap at this point, it is unclear whether she would have treated the gesture as an OHP had she seen it. Nonetheless, this unique gesture of Brooklyn's, as with many embodied and linguistic aspects of the exchange in Example 2, highlights the ways students could gesture simultaneously toward academic concepts and peer interactions, a complexity captured by the final example as well.

4.2.3. Gestural socialization into (not) using gestures

In this final example, students' coyote and OHP practices not only serve as resources for handling conflict but themselves comes to be cast as a source of conflict in a sequence in which norms governing students' gestures are explicitly discussed. In the ~15 min leading up to the below example, I have been helping Brooklyn and four others (all seated at the same table) compose individual poems on worksheets. The students shift between writing on their worksheets, asking me for help, and sharing their ideas with one another, generally joking, laughing, and otherwise taking friendly affective stances toward one another's contributions. However, this friendly affect shifts rather suddenly when a conflict emerges in Example 3 below between Brooklyn and two of her peers, Natalie (one of the girls in the aforementioned four-party conflict) and Elena (a Latina student who was on friendly terms with Natalie and less friendly terms with Brooklyn). Natalie and Elena, who are seated next to each other, are reading their poems to each other and offering each other suggestions when, beginning in line 1, Brooklyn negatively evaluates Natalie's talk as disruptive. The dispute that follows is an episode of quite explicit peer gestural socialization into (presumed or proposed) norms governing OHP use (Example 3; Table 3).

In Example 3, what begins as a complaint about Natalie's verbal actions (lines 1, 2) quickly comes to encompass Natalie's and Elena's embodied actions (lines 11, 14, 24) as well, with new conflicts emerging (see also Burdelski, 2020a) as the stance objects of the three students' negative evaluations shift and accumulate throughout the interaction. The first stance object constructed as worthy of negative assessment is Natalie's verbal behavior. Even though both Natalie and Elena had been talking prior to line 1, and even though neither of them had been speaking particularly loudly, Natalie is the one with whom Brooklyn initially disaligns by verbally soliciting her attention (line 1) and then directing a coyote gesture at her while frowning and saying “shh!” (line 2). After holding the coyote gesture for about 5 s, Brooklyn transforms it into an OHP by releasing the fingers forming the coyote's “snout” to perform OHP (lines 2, 3). As in Example 1, this coyote–OHP sequence conveys intensification and, together with Brooklyn's frown and verbal imperatives, constitutes a multimodal directive for silence.

Elena responds first to this directive, and she does so within a multimodal sequence in which she and Brooklyn gesturally index different raced and gendered styles that modulate their stances. Setting up an alliance of two against one (see, e.g., Goodwin, 2006; Moore, 2020), Elena aligns with Natalie as she disaligns with Brooklyn through a neck roll and finger wag (line 4), gestures that index the oppositional and combative stances stereotypically associated with Black women (e.g., Boylorn, 2008; Goodwin and Alim, 2010). Brooklyn responds by first broadening her prior complaint so that it now encompasses both Elena's and Natalie's actions, shifting in both interlocutor and stance object as she moves from “Natalie” (line 1) to “you guys” (lines 6, 14), then verbally elaborating on the nature of the presumed violation—namely, that Elena and Natalie are talking with and helping each other with their poems rather than leaving it to me to help each student (lines 6, 9). In fact, although Ms. Martin often discouraged peer talk during Language Arts activities, during this activity, none of the adults had explicitly directed students not to talk with one another, and this may be the grounds for Natalie's counterclaim that they are allowed to help each other (lines 7, 8). While Brooklyn's disaligning OHP and verbal disagreement in line 9 communicate a continued investment in positioning her peers as breaching norms, her oppositional stance is somewhat tempered by the short duration of her OHP and by the rather casual, non-chalant stance she takes by touching and adjusting her hair. She touches her hair again in line 15, starting to twirl it as she performs OHP and persists in accusing Elena and Natalie of illegally helping each other. Much like Elena's neck roll and finger wag, Brooklyn's hair-related gestures are raced and gendered, indexing White femininity (Cooper, 2019), particularly the Valley Girl figure and the cool, carefree stances ideologically associated with this persona's hair and other aspects of her embodiment (e.g., Pratt and D'Onofrio, 2017).

This persona and its cool non-chalance are soon abandoned as Brooklyn shifts her accusations from her peers' verbal actions to their embodied actions, doubling down on her investment in negative evaluations in which she repeatedly issues metapragmatic directives casting Elena's and Natalie's responsive OHPs as infractions of norms. However, her multiple claims that Elena and Natalie “can't do that [OHP gesture] back” (lines 11, 14, 35, 37) are treated as illegitimate in that they do not result in Elena or Natalie dropping their responsive OHPs. Rather, upon Brooklyn's first invocation of the (proposed) rule, Elena not only does not concede but joins Natalie in performing an OHP (line 13), and the pushing force of the lean-in (Wehling, 2017) with which Elena performs her OHP upgrades her oppositional stance. Only Brooklyn's threat to tattle (line 19), a quite socially risky action (e.g., Evaldsson and Svahn, 2012), is met by a change in her peers' gestural stances as Elena and Natalie release their OHPs (lines 20, 21). Brooklyn's framing of her peers' responsive OHPs as illegal is also belied by her own use of OHP as an oppositional response to others' OHPs on multiple other occasions (including in Examples 1 and 2 above).

Unfounded and unratified though it may be, the “you can't do that back” rule Brooklyn proposes, together with her continuation of OHP, heightens her investment in her conflictual stance by communicating overt disalignment with her peers' right to use OHP in this way and, by extension, with their right to negatively evaluate her own negative evaluation of their actions. Her proposed rule is also significant in that highlights the importance of OHP in peer conflicts and the multiple, complex, and often competing interpretive frames surrounding them. The gesture's important role in conflicts is likewise reflected by my own framing of OHP as the “best” response (line 26) to what Brooklyn has cast as “rude” behavior (line 25). Although I do not recall having been consciously aware at this point in the study of OHP's function as a conflict-navigation resource in students' peer socialization practices, my metapragmatic comment on the gesture and my own use of it in line 26 legitimate these aspects of students' usage, and they also suggest I had at least partially appropriated students' gestural socialization practices, exemplifying how “learners socialize caregivers, teachers, and other ‘experts' into their identities and practices” (Duff and Talmy, 2011, p. 97; emphasis in original). Perhaps bolstered by the fact that a “teacher” has authorized the use of OHP for disaffiliating with “rude” peers, Brooklyn soon returns to performing OHPs toward her peers (lines 33–37), shifting her gaze between them and her poem. Indeed, Brooklyn's OHP beginning in line 33 is the longest OHP phrase in the data analyzed; it lasts ~2 min, extending the conflict and marking her high level of investment in disaligning with Natalie and Elena. Poignantly, at the same time as one of her hands handles the conflict by holding OHP, Brooklyn's other hand handles her classwork by filling out her worksheet, allowing her to take an overall stance that treats the peer conflict and the academic task as equally relevant to the ongoing activity.

5. Discussion

This paper has investigated how second-grade students used two emblems, OHP and quiet coyote, along with other semiotic resources, to navigate peer conflicts. Through the lens of the gestural socialization perspective described here, I have presented an interactional analysis of students' socialization to and through (Schieffelin and Ochs, 1986) multimodal practices for handling disputes. The analysis highlights both the centrality and the flexibility of the two focal gestures for taking a wider range of stances than those socialized by the teacher's gestural socialization practices. Students often used OHP and coyote not only to pre-empt or mitigate distractions, as intended by Ms. Martin, but to handle disputes, and to do so in their own ways—especially to instigate (Examples 1 and 3), continue (Example 1 and 3), and escalate (Examples 1, 2, and 3) their own conflicts and to monitor and assess others' conflicts (Example 2). Likewise salient within students' conflicts were other embodied resources, including spontaneously created iconic gestures (e.g., the “gavel” gesture, Example 1; the “perimeter” gesture, Example 2) and gestures indexical of raced and gendered personae (e.g., the “neck roll, finger wag” and “hair twirl” gestures in Example 3). Another important resource for navigating disputes was metapragmatic commentary of various types, including metagestures (Example 1), verbal directives accompanying emblems (Examples 1, 2, and 3), and verbal references to (presumed or proposed) gestural norms (Example 3). Together with the two focal gestures, these resources often served to heighten students' investment in their deontic and oppositional stances, but they also sometimes worked to mitigate them (as in the “hair twirl” in Example 3) and to mediate others' conflicts (as in the “gavel” gesture in Example 1).

This analysis extends discussions of peer conflicts in language socialization and other discourse analytic work. First, it is worth noting that with regard to the ages, genders, and ethnoracial identities of the participants, the tendency of Brooklyn and many of her peers to use gestural resources to extend disputes and upgrade their oppositional stances reflects Goodwin's (2006) observations that children—even girls and even White children, whom dominant discourses tend to represent as non-confrontational, prosocial, or well-behaved—often work to achieve and sustain rather than avoid conflict. At the same time, various participants of various racial and gender identities also made moves to avoid, resolve, or interrupt conflictual interactions, as exemplified by Paula's and Madison's mediation sequence in Example 1, Gabe's and Freddy's OHPs in Example 2, and the lack of visible or audible stances taken by many nearby peers in all three interactions. Thus, while dominant developmentalist discourses may represent children as more conflictual than adults (see Berman, 2014) and boys and children of color as especially conflictual, the analysis presented here paints a more complex and interactionally situated picture of these young participants' actions.

A similarly complex picture emerges regarding the role of embodied action in peer conflict. As documented in some other studies (e.g., LeMaster, 2020), sometimes the participants of this study gesturally socialized one another to carry out disputes primarily in the more covert embodied mode (e.g., Example 1), but other times, students' embodied and verbal actions drew peers' and teachers' attention to their disputes (e.g., Examples 2 and 3), as others have documented (e.g., Cekaite, 2012, 2020; Burdelski, 2020a). In both cases, embodied actions, and particularly the OHP and coyote gestures, were indispensable to students' ability to handle conflicts on their own terms. In part, this indispensability reflects the fact that, as conventionalized, culturally shared resources, these emblems were often less ambiguous than spontaneous gestures (such as Brooklyn's “perimeter” gesture and Paula's “gavel” gesture) but more ambiguous than explicit verbal assessments since they had both distraction-mitigating and conflict-intensifying functions in Room Z, thereby allowing students to appear to align with the teachers' efficiency-oriented academic communication practices while also helping them disalign with one another's actions and stances. Compared with similar verbal actions, these gestures also afforded students more possibilities for synchronizing stance expressions and for avoiding explicitly stating locally inappropriate (i.e., oppositional, face-threatening) evaluations (see Andries et al., 2023). Indeed, with regard to the latter point, gestures in general—including even very conventionalized gestures like emblems—are often treated as having a greater degree of plausible deniability than speech (Gawne and Cooperrider, 2022). Finally, both of these gestures allowed students to visually mark the omnirelevance of (potential) peer conflict without verbally disrupting concurrent academic activities. Given the paucity of research on the role of conventionalized gestures in classroom peer conflicts, future research on students' gestural socialization of these and other embodied resources would shed light on how such affordances of emblems and other gestures shape disputes in other ethnographic settings. Such work might also examine gestural socialization practices in other settings and would thus be useful for further developing the gestural socialization perspective proposed here.

This analysis also advances scholarly understandings of emblems and other gestures, particularly with regard to their multiple and dynamic meanings in classrooms. First, by tracing the ways two particular emblems emerge, circulate, and expand in meanings within a classroom community, this study contributes to scholarship on how emblems are learned and how they change (see, e.g., Gawne and Cooperrider, 2022), highlighting how all users—even young users, whose semiotic innovations, expertise, and agency are often overlooked (e.g., Goodwin and Kyratzis, 2011; Lee and Bucholtz, 2015)—contribute to these processes. The study also illustrates the complex relationships between language and gestures as well as the relationships among types of gestures, especially within disputes. With regard to gesture–language relationships, while previous peer conflict work has emphasized how gestures can intensify or support verbal actions (Goodwin, 2006; Bateman, 2012), the findings of this study (especially Example 2) show how such intensification can work in the opposite direction (as when participants verbally comment on gestural phrases already in progress) and how gestures and verbal actions can work in more ambiguous or mutually intensifying ways (as when both types of action are simultaneous), which underlines the value of views of gesture and speech as inseparable (Kendon, 2017). The findings likewise highlight complexity and ambiguity with regard to theoretical understandings of the relationships among gesture types that have been proposed, with Brooklyn's embedding of OHP in her iconic perimeter gesture (Figure 9) as an especially striking example of the potential of gestures to simultaneously communicate discourse-management and narrative-referential meanings (cf. Wehling, 2017).

Besides these contributions to gesture studies and peer conflict research, the analysis presented here raises interpersonal and ideological issues of interest to educators, caregivers, researchers, and others. First, much as OHP and coyote were resources for handling conflicts in Room Z, conflict itself can be seen as a resource for addressing social concerns at the heart of life in and beyond classrooms. Brooklyn's and her peers' socialization of one another—and the adults around them (Example 3)—to use gestural resources for starting, continuing, and escalating conflicts constructs an overall stance that treats conflict as central, rather than necessarily detrimental, to interactions and relationships. In Brooklyn's case in particular, given that the co-construction of her identity as a “trouble maker” was well underway by the second day of school and continued to harden as she traveled along a well-worn itinerary of identity (Bucholtz et al., 2012) throughout the year, conflicts presented her with opportunities for rearranging a social order (Goodwin, 2006) that disadvantaged her. Tellingly, in the disputes examined, she often positioned herself as complying with adults' rules and academic norms, as made especially evident when she verbally solicited adults' attention or gesturally positioned peers as violating (proposed or presumed) rules.

In a more broadly sociopolitical sense, within and even beyond Room Z, Brooklyn's and her peers' conflictual actions can be seen as agentive subversions of a neoliberal, developmentalist social order. Within this order, members are socialized to avoid and minimize conflict, and children are positioned as immature, only partly human, and in need of verbal and embodied regulation by adults if they are to fulfill what is seen as their own—and therefore also their society's (see Richardson and Langford, 2022)—developmental ideals. By refusing to take their teacher's hands-off approach to conflict and instead persisting in holding onto their OHPs, coyotes, and the conflicts shaping and shaped by them, Brooklyn and many of her peers subtly pushed back against the logics of efficiency, appropriateness, and standard language emphasized by the CCSS and dominant US culture. Indeed, as this analysis has shown, many of Brooklyn's and her peers' gestural socialization practices demonstrate how young people can handle academic and social activities simultaneously—a view that is easy to miss without close attention to the nuances of conflict participants' co-constructed multimodal stances. This inseparability of students' social and school lives, epitomized by the peer conflicts that overworked educators may understandably want students to leave on the playground, highlights the importance of anchoring pedagogical approaches to conflict in close observations of children's practices, and it also raises fundamental questions about how people are—and can be—socialized to perceive and achieve conflict in different sociocultural settings. Such questions go hand in hand with examining the sociocultural, political, and economic conditions that are necessary for supporting lifelong socialization into stances that allow people to engage with all the complex challenges and possibilities of conflict—an especially urgent issue in an era of mounting global tensions and crises.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because participants did not give consent to share the data. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to MC, bWVnaGFuLmNvcmVsbGFAdWJjLmNh.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by UC Santa Barbara Human Subjects Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

MC conceptualized the study, developed the theoretical framework, collected the data, carried out the data analysis, and wrote all sections of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Brooklyn, Ms. Martin, and all the students in Room Z for their participation in the study and all they have taught me. Special thanks go to Jessica Goldstein for anonymizing the images of participants by producing all the line drawings featured in the paper. I would also like to thank Steven Talmy for very helpful feedback on an earlier draft of this paper and the reviewers and editor for all their insights and assistance. Finally, I am grateful to research assistants Desiree Basl, Kimberly Chen, Nicole Donaldson, Aimee Giles, Melia Leibert, Ellen Ouyang, Diana Phan, Francesca Sen, and Alex Rubio for their help with logging and coding the data for the larger study.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2023.1251128/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^Throughout this paper, I use pseudonyms to obscure participants' identities.

2. ^To protect these participants' identities, I regrettably cannot further specify their ethnoracial or linguistic backgrounds. Other participants' ethnoracial identities are described where doing so does not pose a risk of identification.

3. ^As one reviewer points out, considering OHP's widespread use in other settings and its association with negativity, a question arises about whether students' OHP practices were mobilized from Ms. Martin's. To be sure, conclusively determining whether and to what extent students' OHPs were shaped by their teacher's is difficult, particularly since, as an emblem, OHP tended to be used by students without accompanying speech. However, in a few cases, students' verbal contextualizations of OHP echoed Ms. Martin's practices (e.g., using the same emic labels for the gesture; accounting for OHPs to substitute teachers). The connection between OHP and quiet coyote (a gesture specific to classroom settings), as exemplified by the innovative coyote–OHP sequences discussed below, likewise highlights the relationship between students' OHPs and Room Z routines. Also important is the prevalence and relatively unmarked status of the gesture in a variety of peer interactions (both collaborative and conflictual). Of course, none of this means that OHP practices in the broader culture did not serve as a resource for students' interactions—indeed, Ms. Martin's “give me five” label for the gesture directly indexed gesture practices in other settings—but simply that the teacher's gestural socialization practices also clearly shaped the ways students used and reanalyzed the gesture.

References

Agha, A. (2003). The social life of cultural value. Lang. Commun. 3, 231–273. doi: 10.1016/S0271-5309(03)00012-0

Andries, F., Meissl, K., de Vries, C., Feyaerts, K., Oben, B., Sambre, P., et al. (2023). Multimodal stance-taking in interaction—A systematic literature review. Front. Commun. 8, 1187977. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2023.1187977

Antonsen, C. M. (2019). Children's bodies in British Columbia's child care regulations: a critical discourse analysis. J. Childh. Stud. 44, 1–12. doi: 10.18357/jcs442201919056

Aragón, M. J. (2022). “I think they're Hispanic”: agency and meaning-making in Latinx students' discussions about text. Linguist. Educ. 69, 101045. doi: 10.1016/j.linged.2022.101045

Arnold, L. (2012). Dialogic embodied action: using gesture to organize sequence and participation in instructional interaction. Res. Lang. Soc. Interact. 45, 269–296. doi: 10.1080/08351813.2012.699256

Bakhtin, M. M. (1981). The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays by MM Bakhtin (C. Emerson & M. Holquist, Trans.). Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Bateman, A. (2012). “When verbal disputes get physical,” in Disputes in Everyday Life: Social and Moral Orders of Children and Young People, eds S. Danby, and M. Theobald (Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited), 267–295.

Beaupoil-Hourdel, P., and Morgenstern, A. (2021). French and British children's shrugs. Gesture 20, 180–218. doi: 10.1075/gest.19043.bea

Berman, E. (2014). Negotiating age: direct speech and the sociolinguistic production of childhood in the Marshall Islands. J. Linguist. Anthropol. 24, 109–132. doi: 10.1111/jola.12044

Boylorn, R. M. (2008). As seen on TV: an autoethnographic reflection on race and reality television. Cri. Stud. Media Commun. 25, 413–433. doi: 10.1080/15295030802327758

Brass, J. (2014). English, literacy, and neoliberal policies: mapping a contested moment in the United States. English Teach. 13, 112–133.